Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 3

September 16, 2025

a slightly embarrassed announcement

Two weeks ago I entered mortal combat with Covid, and have emerged victorious but not unscathed. This bout featured an unexpected symptom: persistent vertigo, especially when looking at text. Not a great situation for someone in my line of work! (And with my personal preferences.)

But if I kept my computer screen at a certain distance and held my head still, I could without experiencing physical nausea read stuff on the internet. So for about a week what’s what I did, and the positive result, as I saw it, was that I was able to queue up several posts for my blog.

After about a week I started feeling better, and one evening I put on an Ella Fitzgerald record and sat down with my notebooks … and just started laughing. Laughing at how simply pleasureable pen and paper and music were. How much happier I was with the internet at a safe distance.

And the next day, when I looked over the posts I had queued up, I thought: these are unpleasant. These are the posts of … not an angry man so much as a petulant man. A man who had over the course of a week absorbed, as by osmosis, the Spirit of the Internet. And that is a foul, foul thing. Think of the polluted river in Spirited Away before Chihiro/Sen cleans him up.

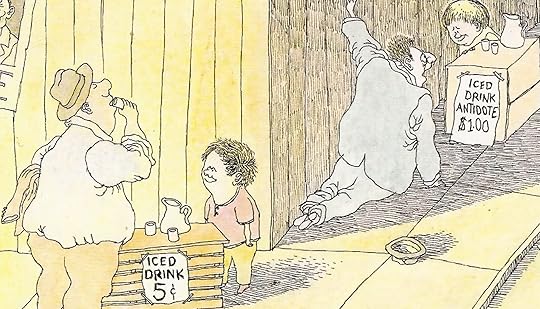

I feel that in the last few days I’ve been purging myself. My head was full of this:

I had five posts queued up, and I’ve deleted all five of them. That means that in the coming week or two you’ll have fewer posts in your feed, but also that you’ll have less petulance in your feed. You’re better off, trust me on that.

And by the way, all this happened before the murder of Charlie Kirk. I only had a vague sense of who Charlie Kirk was, but suddenly my informational world was filled with people being maliciously idiotic online, while the legacy media were producing articles titled “Breaking News: People Being Maliciously Idiotic Online.” (See image above for what all that looked like.) At least that gave me the opportunity to purge my RSS feeds.

All this leads me to one more thought: often, when some current event crosses my horizon, I’ll start to write about it and then pause and ask myself whether I’ve written about that kind of thing before. I’ll do a little search, and usually I discover that I have indeed written about that kind of thing before. New events tend not to be anomalous; rather, they continue patterns of action and thought that are well established. Cultural change almost never happens suddenly. There’s a long, slow development or evolution along established lines. For instance, Yuval Levin’s book The Great Debate demonstrates quite conclusively that the pattern of contemporary political debates was established by the contest in the late 18th century between Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine. This is typical.

I hear many people saying that the assassination of Charlie Kirk “changes everything” for them, but they already said precisely that about the attempted assassination last year of Donald Trump. In fact neither event altered anyone, except to consolidate their myths. There is very rarely anything new under the sun, and the surest sign that all the existing norms and terms and disputes are firmly in place comes when people start shouting “This changes everything!”

When I look back through this blog I see certain themes, both analytical and prescriptive, articulated repeatedly. I have a fairly consistent explanatory framework to account for our culture’s primary traits, especially its pathologies; also for the conflicts that afflict the church. I have little new to add by way of explanation or prescription because my culture is locked into certain obsessively repeated patterns from which very few people learn anything. What I said five or ten years ago is equally applicable today (if it was ever applicable at all).

It’s especially important to remember that people love hating their enemies — they love that more than anything. So the worst thing you could do to them, as far as they’re concerned, is to diminish their hatreds. To those of us who don’t happen to share those hatreds, their behavior might look like wearying, pointless repetition. But from the inside, those hatreds are the primary instrument of myth confirmation. They give security, and people want security. I can’t blame them for that, but I sure wish they chose different means to that end. I have no influence in the matter, though.

In short: I’m wondering what the point of this blog is. Increasingly, I think of it as something complete. I don’t regret writing it, but it may have served its purpose, and I’m inclined to think that I should focus on my microblog as a kind of Cabinet of Curiosities, linking to posts from here when they seem to illuminate some new-but-not-really-new situation but writing new things here only rarely. And then almost always little essay-reviews on books and movies.

I need to mull all this over further — not that it matters much. My sense is that I’m one of those writers whose books make more of a difference than their online presence, though of course not much difference. So few people read anything I write — glamping videos on YouTube get eight million views while I’m a long way from a thousand true fans — that if I made decisions on the basis of influence I would just quit. But I’m trying be obedient to my calling. Hard to know what that means in this media environment, though.

Anyway, no matter how much or how little I write here, I’ll keep the blog up for public access.

September 15, 2025

consolidation of myth

What people do in response to violence is consolidate the myths they live by. This focuses emotion and fosters solidarity, but it also renders people susceptible to control by non-human forces, submission to which, in times of crisis, looks like virtue.

I’ve written a lot about all this. See:

“Wokeness and Myth on Campus” “Something Happened By Us: A Demonology” “Yesterday’s Men”I’ve also written about the artists who reveal to us the power of our myths, including William Blake and Thomas Pynchon and, of course, Auden.

If you want to know what’s really going on with us, you can’t just ask yourself what side to take in the tempest du jour. But of course very few people want to know what’s really going on. Most people are not interested in understanding anything, they want to experience powerful emotions, good or bad — “All emotion is pleasurable,” Craig Raine has said —, that make them feel righteous.

See also the myth tag at the bottom of this post.

September 12, 2025

chaplains in the fire

The starting point for my friend Tim Larsen’s new book The Fires of Moloch is another book, one published in 1917 and often reprinted over the next few years. The Church in the Furnace is a collection of essays by Anglican clergymen who served in the Great War as military chaplains. The chaplains were sometimes thought to be of a modernizing or liberalizing tendency because they were so straightforward about the horrors of the war — and what they believed to be the church’s unpreparedness to minister to people who had been through such horrors, or even those who merely observed them from a distance. It a collective cry for the Church of England to take steps, however dramatic, to prepare itself to minister to a world very different than that which their Victorian ancestors had known.

The brilliant idea that Tim had was to look at the stories of each of the seventeen contributors to The Church in the Furnace. Throughout his career Tim has written books that provide brief biographies of a series of related figures and then show how these figures are related to one another, whether personally, intellectually, or culturally. For instance, his book The Slain God concerns a series of anthropologists and their encounters with Christianity. When imagining Tim’s books, think Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, with a good deal of the humor but without the cynicism and the camp. This group of chaplains is particularly well suited for this kind of treatment, because if you look at their experiences you’ll see that they were uniformly appalled by the war into which they were thrown, and agreed that the Church of England was not prepared to meet the challenges of the war — but they had very different senses of what the key problems were.

It seems to be believed in some circles that these were Anglo-Catholic clergymen, but as Tim points out at the beginning of his account, only some of them were. They really covered the whole spectrum of the Church of England — high church, low church, and broad church — and while some embraced modernist revisions to traditional Christian theology, others were conventionally creedal in their thinking. They also had widely varying ideas about what the primary emphasis of the church should be as it strove to meet the challenges of a bloody twentieth century.

Tim does an exceptional job of contextualizing The Church in the Furnace, first by showing who these chaplains were when they entered the war: what they brought to their work as chaplains, what experiences, what history, what theological formation, what pastoral philosophies. You can see the wide variety of ways in which they were not (as indeed they could not have been) prepared for what they had to face. But then, having shown that, Tim goes on to show how deeply and permanently they were, without exception, marked by their experience as military chaplains. For the rest of their lives — and in some cases those lives were quite long — they continued to think of Christianity and Christian ministry in ways that shaped by their experience in war. For instance, almost all of them became inclined at one time or another to conceive of the Christian life in military terms. This imagery, of course, is is present in the New Testament, though present among many other metaphors; but it becomes central for most of these chaplains. Some of them speak of Christ as “our great captain” who has recruited us into his army, has made us his soldiers. This image becomes the default model of the Christian life for several of these clergymen, and a significant part of the rhetorical and theological equipment for all of them.

Finally, one other noteworthy theme emerges. There’s a general sense that war has the effect of alienating people from their religion. But in fact, what was seen in the Great War was a dramatic increase in prayer, both individual and public. One of the most consistent messages of these clergymen was that they found that, other than the Lord’s Prayer, which most of the soldiers knew, they really didn’t have any idea how to pray, never having been instructed in prayer. And if there was one thing that all of these clergymen agreed on, it was that the church desperately needed to to teach people how to pray. And I suspect that is a message that is as relevant now as it was then, if not more so.

September 10, 2025

KK on publishing

This post by Kevin Kelly about publishing is interesting and informative, but it gets some things wrong. For instance, he says this about the traditional publishing route:

The task: You create the material; then professionals edit, package, manufacture, distribute, promote, and sell the material. You make, they sell. At the appropriate time, you appear on a book store tour to great applause, to sign books and hear praise from fans. Also, the publishers will pay you even before you write your book. The advantages of this system are obvious: you spend your precious time creating, and all the rest of the chores will be done by people who are much better at those chores than you.

Book tours have always been for bestselling authors, not for midlisters. I’ve never had a book tour, though I have had publishers pay for the occasional one-off talk. And “pay you even before you write the book”? — well, they’ll pay you something, but, as I’ve said before, advances are parceled out: if you get a book contract on the basis of a proposal, then you’ll get a certain about on signing, a certain amount on turning in a complete manuscript, a certain amount on pub date. All of this is an “advance” in the sense that it arrives before any copies have been sold, but if you hear that someone has a $100,000 advance, they’ll probably on signing the contract get $25,000. Long gone are the days when a writer could live on his or her advance while writing the book. (The people who could live on their advances are people who already make so much money that they don’t need the advances.)

One note about “packaging”: I have found that, in general, publishers will work with authors to get a cover that everyone likes — often by showing three or four options. But when Profile in the U.K., the publisher of Breaking Bread with the Dead, showed me the cover of the book — one design and one only — I told them that I hated it more than I could possibly say and they replied that they were going to use it anyway. (One editor added that what I had written was basically a bunch of essays so it’s not like it really matters what it looks like.) When they sent me my author’s copies of the finished book I tossed the box in a closet and have never opened it. I really think that with that dreadful cover they killed any chance of the book doing well in the U.K.

Their cover for How to Think, my other book with them, was great.

New York book publishers do not have a database with the names and contacts of the people who buy their books. Instead, they sell to bookstores, which are disappearing.

No, the decline in bookstores stopped around 2019, and since then there’s been a mild upturn. Who knows whether it will continue, but for now bookstores still matter, very much.

Are agents worth it? In the beginning of a career, yes. They are a great way to connect with editors and publishers who might like your stuff, and for many publishers, this is the only realistic way to reach them. Are they worth it later? Probably, depending on the author. I do not enjoy negotiating, and I have found that an agent will ask for, demand, and get far more money than I would have myself, so I am fine with their cut.

This isn’t wrong, but it’s not the whole picture. An agent will almost certainly negotiate a bigger advance for you than you could negotiate for yourself, but a good agent will also retain foreign rights and then negotiate with overseas publishers and translators. If you do not have an agent, then your initial publisher will keep those rights for itself and then do whatever it wants. I am not sure how much money I have made over the years from overseas editions of my books, but a rough guess would be $50,000. Not a fortune, but nothing to sneeze at.

Now, about trade publishing KK makes one essential true point:

BTW, you should not have concerns about taking a larger advance than you ever earn out, because a publisher will earn out your advance long before you do. They make more money per book than you do, so their earn-out threshold comes much earlier than the author’s.

Two of my books (Original Sin and Breaking Bread with the Dead) have not earned out their advances, but the publisher has made money from both of them.

About self-publishing I know absolutely nothing, but KK makes me wonder whether I might want to try that at least once in my life. But, as he makes clear, when you’re DIY-ing it all the work is on your shoulders, including the following things that in traditional publishing others do for you:

EditingDesigningPrintingBindingStoringSellingShippingPromotingYou may say “Well, I can hire people to do those things for me” — but that process will itself be time-consuming, and you might find that at a certain stage you’ve simply re-created the traditional publishing model.

September 8, 2025

unenlightened self-interest

People often ask me why I don’t teach a YouTube lecture course on jazz history. It’s a great idea — but I can’t teach the course without playing music, and record labels would shut me down in a New York minute.

It’s absurd. I might be able to develop a huge new audience for jazz — maybe even a million new fans. The record labels would benefit enormously. But that doesn’t matter. They would still shut me down.

Rick Beato deserves better than this. His audience knows how much good Beato does. We see how much he loves the music and how much he supports the record labels and their artists. They should give him their support in return.

If UMG wants to retain a shred of my respect, they need to act now. And if they don’t, maybe the folks at YouTube should get involved. They are bigger than any record labels, and this might be a good time for them to show where they stand.

Just as Universal Music Group should have the brains to know that their music showing up on Rick Beato’s channel is good for them, so also YouTube should know that it’s in their interest to support their creators when possible: the more people who watch Beato’s channel the better it is for YouTube. But one of the fascinating things about our megacorporations is how unenlightened and unreflective their self-interest (i.e. rapacity) is. Unlike Ted, I doubt that anyone in authority at YouTube cares about creators. They should; it’s stupid not to; but if they haven’t always been stupid they’ve been stupified.

Who stupefied them? Right now I’m reading Dan Wang’s brilliant book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, and the governing distinction of his book is a simple but, in its development, very powerful one: China is run by engineers, while America is run by lawyers. And engineers are very good at making things happen, while lawyers are very good at preventing things from happening.

This is not Wang’s way of saying that China is superior to America: he makes it clear that when engineers are in control they often end up making stuff that should never have been made, and that lawyers often prevent the bad stuff from being unleashed on the world. His point is that if you want to know which of these two massively powerful countries will dominate the next few decades, you need to know who’s in control in each country.

At Universal Music Group, the lawyers control the engineers, so they assign the engineers to write code that will auto-detect copyright violations and then auto-send takedown notices to the supposed violators. That the code returns a lot of false positives is of no concern to the lawyers: for them it’s better that ninety-nine innocent people be punished than one copyright violator go free. Likewise, while they know that U.S. copyright law has fair use provisions, they hate those provisions, and would prefer ninety-nine people who stay within the boundaries of fair use to be punished than to allow one person who transgresses fair use limits to go free.

When Rick Beato — like thousands of other music-focused YouTubers — gets a takedown notice from YouTube, he can contest it, arguing that his musical clips were so short that they clearly fell within the scope of fair use, or that he actually didn’t use the UMG-owned music at all. But then someone at YouTube has to evaluate his claim, and does YouTube have enough people assigned to the task of evaluating claims? Of course not. Is the evaluation of such claims the kind of thing that can be reliably assessed by bots? Of course not. So the easiest thing for YouTube to do is to sustain the takedown demand and demonetize the offending (or “offending”) videos.

The next step for Beato would be a lawsuit, against UMG or YouTube or both, but while Beato is a very rich man compared to me he is poverty-stricken in comparison with corporations like UMG and Alphabet. If he could survive financially long enough to get to trial — something that the corporations would do everything in their extensive power to prevent — he would surely win his case. But then there would be appeals.

The message of UMG and Alphabet to creators is simply this: It doesn’t matter if the law is on your side, we are so much bigger than you that we will destroy you. And they’re almost certainly right; I don’t even think a class-action suit entered by all the offended creators would be able to overcome the weight of megabucks.

As I say, it’s just stupid. Because the music companies are terrified of losing even more economic ground than they’ve already lost, they treat their best friends as enemies. They’d be appalled and disgusted by the idea that they need people like Rick Beato and Ted Gioia, but they do. They’re like a zillionaire being swept away by a flood: some redneck on the bank tosses him a lifeline, and before he goes under for the last time the zillionaire sputters, What’s in it for me?

September 5, 2025

that’s still how it goes, everybody still knows

I’m a High Schooler. AI Is Demolishing My Education:

AI has transformed my experience of education. I am a senior at a public high school in New York, and these tools are everywhere. I do not want to use them in the way I see other kids my age using them — I generally choose not to — but they are inescapable.

During a lesson on the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, I watched a classmate discreetly shift in their seat, prop their laptop up on a crossed leg, and highlight the entirety of the chapter under discussion. In seconds, they had pulled up ChatGPT and dropped the text into the prompt box, which spat out an AI-generated annotation of the chapter. These annotations are used for discussions; we turn them in to our teacher at the end of class, and many of them are graded as part of our class participation. What was meant to be a reflective, thought-provoking discussion on slavery and human resilience was flattened into copy-paste commentary. In Algebra II, after homework worksheets were passed around, I witnessed a peer use their phone to take a quick snapshot, which they then uploaded to ChatGPT. The AI quickly painted my classmate’s screen with what it asserted to be a step-by-step solution and relevant graphs.

As I have said before: Everybody knows what this is. There is literally not one person who believes that kids learn anything about anything when they’re allowed to spend their classroom time on their laptops and phones. Everybody knows that education has been given up on; everybody knows that teachers are just babysitting; everybody knows that the fix is in.

The only question remaining is: Can we lie about the situation forever?

September 2, 2025

my Proustian moment

One of my favorite videos on the internet is this one, featuring Arsenal legend Ian Wright’s story of Mr. Pigden, the primary school teacher in South London who genuinely changed his life — and the moment in 2005, some years after Wright’s retirement, when the two of them were reunited. If you ever doubt that teachers can make a difference, watch this video.

It’s such a beautiful scene: Wrighty stands looking around the pitch at Highbury, smiling in memory of his great accomplishments there, when he hears a warm, kind voice: “Hello Ian. Long time no see.” Wrighty turns and looks and two things happen. First his mouth falls open in astonishment … and then he snatches his peaked cap off his head, in what I can only call reverence.

When he can speak he says, “You’re alive.”

Mr. Pigden, turning to someone behind the camera with a smile: “I’m alive, he says.”

Wrighty, trying and failing to compose himself: “I can’t believe it … someone said you was dead.”

Watch the rest of the video to learn exactly why Mr. Pigden was so important to young Ian Wright.

I love everything about that video, but the key moment for me is when Wrighty removes his cap. It’s absolutely instinctive: I don’t know where or when Wrighty learned his manners — he grew up in a very tough environment, but in the toughest of environments there are women who teach their children well — but he learned them. And the moment I first saw Wrighty snatching that tweed from his head, my memory leaped back to Birmingham, Alabama in 1973.

What I remembered was my friend Don. Don was the coolest guy I knew. He was very funny and very smart though (at the time) not the least interested in academics, and he always had weed, and he wore his black curly-kinky hair long, in the style that people call a Jewfro when Jews wear it, but Don wasn’t Jewish: He was a Scot by background, and his family were very proud of their ancestry. (So we could call his do a BRU-fro, amirite?)

In our senior year Don actually cut his hair quite short, just as everyone else was letting theirs grow long. Which just proved that he was cooler than everybody else. But this memory goes back before that.

Several other guys and I spent a lot of time hanging out at Don’s house, because it was the nicest house most of us had ever seen. My dad worked in trucking (when he wasn’t in prison) and that’s what our neighborhood was like: lots of plumbers, electricians, Teamsters, at the upper end factory-floor supervisors. Some stay-at-home wives and mothers, others who worked more than their men, as my mom did. But there was one road not far from our high school featuring a handful of big houses, set on rising ground, with what seemed to me enormous front yards, and Don lived in one of those. In fact, if I recall correctly, his was the only one that was modern, and the best way I could describe its modernity to you is to tell you that it had a sunken living room, with a plate-glass window covering one wall and a big fireplace on the opposite wall and built-in sofas extending all along three sides. You walked down into it by steps set at the corners of the room flanking the fireplace. I had never seen anything like it except in a handful of movies and TV shows.

One other feature of the room: a tall flipchart easel at one end of the room. Don’s father used it for group therapy sessions: he was a psychoanalyst, and his chosen method was transactional analysis. The family had fairly recently moved from somewhere up north — Pennsylvania, I believe — presumably to reach Birmingham’s vast untapped market of potential TA patients. Don’s father had an EAT MORE POSSUM bumper sticker on the back of his car, for protective coloration, but since the car was a Volvo the sociological message he sent while driving around town was complex and possibly self-contradictory. (Of course he knew that.) Copies of Thomas A. Harris’s I’m OK — You’re OK were scattered around the house, but when I took a peek at what was written on the flipped-over sheets, words and symbols equally incomprehensible to me, I found it difficult to believe that anyone was OK.

Don had (I think) two older sisters, but they were away at college, and it seemed that his parents were never at home, so we had the house to ourselves for weekends and summer days. And what did we do with our time? Basically four things; we smoked pot; we played Risk; we ate heated-up frozen pizzas — something that I had not known existed before I visited Don; and we listened to Beatles records, especially the White Album. (Of course we played “Revolution 9” backwards and listened with maniacal intensity for secret messages. Though sometimes being stoned limited our attentiveness.)

For obvious reasons, we hung out at Don’s rather than at my dilapidated junkheap of a house, with broken springs emerging from the ancient sofas on the front porch — kept the stray dogs off, my dad said — and grass two feet high in the front yard — higher still in the back — and an ancient air-conditioner in one room that had broken down when we had been in the house only three or four months, never to be repaired. But once, for a reason I don’t remember, Don did visit.

Now in those days were were not allowed to wear headwear of any kind of school, nor could we leave our shirts untucked. (The rules on jeans were intricate and changed from year to year; that can be a subject for another post.) But whenever Don wasn’t at school he wore this white silk peaked cap like the ones automobile racers wear in old photos. It was awesome. When he pulled it down on his head his hair stuck out at angles that seemed gravitationally impossible. And that’s what he was wearing when he visited my room.

At one point we heard steps approaching. The door opened and my grandmother stood there — I don’t remember why she had come. But the moment the door opened Don, who had been sitting on my bed, popped to his feet like a jack-in-the-box and simultaneously plucked the white cap from his head and held in in both hands pressed to his chest like an undergardener approaching the wrong door at Downton Abbey. I told my grandmother that this was my friend Don and he said “How do you do, Ma’am.” I’ve never been more shocked in my life; I stared at him blankly for a few seconds. I don’t know where or when he had learned his manners, but he had learned them well.

And the first time I saw Ian Wright’s removing his cap in the presence of Mr. Pigden everything that I have just told you flooded into my mind.

September 1, 2025

the pleasures of reading

Jancee Dunn, author of the NYT’s Well newsletter, asked me a while back to answer some questions about reading. Just a couple of items from my reply made their way into her column — she had plenty of other people to interview! — so I thought I would post my whole email to her here. Some of these thoughts are expressed at greater length in a book of mine.

Jancee, I think I’ll start with the “reading challenges” and keeping track of your reading on Goodreads or elsewhere. I’m not saying that that can’t be a good: it can help build self-discipline, for one thing, and you can prove to yourself that you’re able to resist the temptation to flick through TikTok or play another round of Candy Crush. But I don’t think it has a lot to do with reading as such. I often hear people who do these self-challenges talk about how many books they have “gotten through” in a month or a year, and that just makes my reading-loving heart ache. Books are not to be “gotten through”! Books are to be delighted in!! (Books you’re reading by choice, anyway.)

This is related to the question of when you should read. I look of people who want to add to their numbers — to be able to say at the end of the year that they read X number of books in 2025 — are often tempted to open a book at 10pm, stare at it with glazed eyes, make those tired eyes pass across each page, and then set it down at 11:15 with the bookmark fifty pages farther in than it had been … and after a few nights of this they have another book they’ve “gotten through” that they didn’t enjoy and don’t remember — don’t remember because they never actually read it in the first place. That’s why before they post their review on GoodReads they have to ask ChatGPT to summarize the book they’ve just “read.”

Don’t try to tell me this doesn’t happen. A LOT.

So to people inquiring about these things I would say: Do you want to read? Or do you just want to have read — or even to be able to say, online and relatively convincingly, that you have read? If you’re in those latter two groups, I can’t help you. But if you really want to read more, then I have some advice:

1) Start by re-reading something you love — something that made you love reading. If you want to read now, it’s probably because of that book. Re-connect with it, and you’ll re-connect with your reading self.

2) Never ever apologize for re-reading. Read the same thing three times in a row if that gives you pleasure. One of the most wonderful moments you can have as a reader is to reach the final page, sigh, stare off into space for a few moments … and then return to page one. (I do this with movies sometimes too: “Watch from beginning.”)

3) Read responsively. For some that will mean writing in the margins or on sticky notes, but I have found that when you’re reading plot-driven fiction you won’t want to do that: better to wait until the end of a long session and then write your responses in a journal or make a voice memo to yourself. (Apple’s Voice Memos app now has automatic transcription, so you can turn your voice memos into written text. There are similar apps for Android, the best of which appears to be Google Recorder.) One of the best ways to feed your reading impulse is to revisit your excitement about past reading experiences. Heck, even if you don’t like a book there’s fun in explaining to yourself just why you dislike it. If you read responsively you’ll read fewer books but you’ll READ them.

4) Don’t keep count of how many books you read. If you start keeping count you’ll rush, you’ll neglect to be responsive, you’ll get back into that bad habit of just passing your bleary eyes across the page and calling it “reading.”

5) New way to be the coolest kid in the room: “I only read a few books this year, but I read each of them three times and made extensive notes to be sure I got the most out of them.”

6) My idea about reading “upstream” is this: if you loved Harry Potter, you’re not going to be able to recapture the delight by reading a new book about a boy named Larry Carter who goes to the Mugwumps Academy of Sorcery. That never works. Same with all the Tolkien knock-offs. Instead, find out what books J. K. Rowling and J. R. R. Tolkien really loved and read those. What fed their imaginations stands a good chance of feeding yours.

(Sometimes little things, even, are useful. In the Harry Potter books the caretaker Argus Filch stalks around Hogwarts with his snoopy cat Mrs. Norris. Why “Mrs. Norris”? Well, in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park the heroine, Fanny Price, has a nasty aunt who’s always watching her and trying to put her in her place. Her name? Mrs. Norris. And then you realize that, like Harry Potter, Fanny Price is a young person living not with her parents but with an aunt and uncle … hmmm. Suddenly connections start to form between two stories that on the surface don’t look alike at all.)

7) I always smile when people tell me they don’t enjoy or don’t understand or are intimidated by poetry. I ask them, “How many songs can you sing from beginning to end?” The answer is probably: hundreds. And songs are poems set to music. A fun exercise: look for poems in rhyme and meter and see if you can find a good tune for them. The easiest poet to do this with is Emily Dickinson, because she always wrote in what’s called “common meter” or “hymn meter.” So you can sing all of Emily Dickinson’s poems to the tune of “Amazing Grace” — or, even more enjoyably, to other songs that are not hymns but are in that meter. For people of my generation, I would suggest the Gilligan’s Island theme song. And then you can do a Gilligan’s Island / “Because I could not stop for death” mashup. Sing it with me:

Because I could not stop for death

He kindly stopped for me

The carriage held but ourselves

And immortality,

And Gilligan, the skipper too,

The millionaire and his wife…

If you want to develop a love of poetry, reconnect it with music, which is its origin. You’ll not only appreciate poems better, you’ll find yourself memorizing them! Then you can gradually move on to poems that are less obviously musical. (Though all really good poems have music to them.)

8) Libraries are great places to find things that no algorithm would ever suggest to you. This is important because we are collectively losing our faculty for total random surprise — for serendipity. Libraries are serendipity vendors. Unfortunately, in our time libraries are becoming less common, and the ones that still exist are becoming less like libraries. But if you live anywhere near a university, university libraries tend to be open to the public, and also tend to preserve their collections longer than public libraries do. Even if you can’t check out the cool random book you discover, you can sit down with it for a while. And then if you love it you can buy your own copy.

August 28, 2025

the AI business model

I used this Gahan Wilson cartoon a while back to illustrate the ed-tech business model: the big ed-tech companies always sell universities technology that does severe damage to the educational experience, and when that damage becomes obvious they sell universities more tech that’s supposed to fix the problems the first bundle of tech caused.

This is also the AI business model: to unleash immense personal, social, and economic destruction and then claim to be the ones to repair what they have destroyed.

Consider the rising number of chatbot-enabled teen suicides: OpenAI, Meta, Character Technologies — all these companies, and others, produce bots that encourage teens to kill themselves.

So do these companies want teens to kill themselves? Of course not! That would be stupid! Every dead teen is a customer lost. What’s becoming clear is that they’re hoping to give teens, and adults, suicidal thoughts. Their goal is not suicide but rather suicidal ideation.

Look at OpenAI’s blog post, significantly titled “Helping People When They Need It Most”:

When we detect users who are planning to harm others, we route their conversations to specialized pipelines where they are reviewed by a small team trained on our usage policies and who are authorized to take action, including banning accounts. If human reviewers determine that a case involves an imminent threat of serious physical harm to others, we may refer it to law enforcement. We are currently not referring self-harm cases to law enforcement to respect people’s privacy given the uniquely private nature of ChatGPT interactions.

So that’s Step One: Don’t get law enforcement involved. Step Two is still in process, but here’s a big part of it:

Today, when people express intent to harm themselves, we encourage them to seek help and refer them to real-world resources.

Well … except when they don’t. As they acknowledge elsewhere in the blog post, when conversations get long, that is, when people are really messed up and in a tailspin, “as the back-and-forth grows, parts of the model’s safety training may degrade.”

Continuing:

We are exploring how to intervene earlier and connect people to certified therapists before they are in an acute crisis. That means going beyond crisis hotlines and considering how we might build a network of licensed professionals people could reach directly through ChatGPT. This will take time and careful work to get right.

This I think is the key point. OpenAI will “build a network of licensed professionals” — and when ChatGPT refers a suicidal person to such a professional, will OpenAI take a cut of the fee? Of course it will.

Notice that ChatGPT will, in such an emergency, connect the suicidal person to a therapist within the chatbot interface. You can go to the office later, but let’s do an initial conversation here. Your credit card will be billed. (And for how long will OpenAI employ human beings as their chat therapists? Dear reader, I’ll let you guess. In the end the failings of one chatbot will be — in theory — corrected by another chatbot. And if you want to complain about that the response will come from a third chatbot. It’ll be chatbots all the way down.)

So then the circle will be complete: drawing vulnerable people in, encouraging their suicidal ideation, and then profiting from its treatment. That’s how to “help people when they need it most” — by manipulating them into the needing-it-most position. Thus the cartoon above. Sure, some kids will go too far and kill themselves, but we’ll keep tweaking the algorithm to reduce the frequency of such cases. You can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs!

I sometimes ask family and friends: What would the big tech companies have to do, how evil would they have to become, to get The Public to abandon them? And I think the answer is: They can do anything they want and almost no one will turn aside.

A few years ago I said that vindictiveness was the moral crisis of our time. But some (not all, but some) of our rage has burned itself out. The passive acceptance of utter cruelty, in this venue and in others, has become the most characteristic feature of our cultural moment.

August 26, 2025

something, everything

In Linebaugh’s treatment of Scripture the church is nowhere to be found. For that matter, equally absent are tradition, liturgy, the sacraments, and the Holy Spirit. The result, if I may put it this way, is an account of the Bible and its message that is maximally and perhaps stereotypically Protestant. By this I don’t mean the book is “not Catholic.” I mean that it is so intensely focused on the “solas” — Christ alone, grace alone, faith alone, Scripture alone—that it leaves by the wayside other essential features of the gospel.

Disclosure: Jono Linebaugh is a friend of mine, but then so is Brad, and I’ve written in commendation of both of them, so I think all that cancels out.

If “an invitation to Holy Scripture” must also give an account of “tradition, liturgy, the sacraments, and the Holy Spirit,” then it will be the size of the Church Dogmatics and won’t be an “invitation” to anything. For the same reason that I think it would be fine to write an invitation to the sacraments that does not also give an account of Holy Scripture, I think it’s fine to write an invitation to Holy Scripture that’s just about Holy Scripture. If we think every book has to be about everything relevant to the topic of that book, then we’ll never find a book worthy of our praise.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers