Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 5

August 1, 2025

the rule book

I’ve been thinking about things Irish recently, and when you’re thinking about things Irish, perhaps Ulysses (the subject of my previous post) is a less useful work than Dubliners. Joyce clearly thought of the stories in Dubliners as a single work, which he described as “a chapter in the moral history of my country.” Hey, I’m interested in the moral history of countries, so I just reread those stories for the first time in, I dunno, maybe 25 years? Now, to be sure, I regularly re-read “The Dead,” which I, like many people, believe to be the greatest short story in the English language. But I hadn’t re-read the other stories, largely because, as I explained in my previous post, I focused so much pedagogical attention on Ulysses.

Returning to Dubliners after all these years away, the main thing that I found myself thinking was simply that here Joyce wrote the rule book for short fiction that would be used for the next hundred years and more; that people still, even if they don’t know it, and even if they’ve never read Dubliners, are writing stories the way Joyce did. How they sketch character, how they deploy point of view, above all how they handle plot and plotlessness — those who publish in literary journals in 2025 are essentially writing the kinds of stories that Joyce taught them to write.

Kipling wrote at roughly the same time as Joyce and is, I think, a greater writer of short stories. He never wrote one story as great as “The Dead,” but his whole body of short fiction is far superior to Joyce’s. But nobody writes stories like Kipling’s; his tales come from another world, another mentalité. How long before the writing of short fiction puts Joyce clearly in the past?

July 30, 2025

Ulysses and me

Of all the novels I have ever read, the one that I know the best is probably Joyce’s Ulysses — a book with which I have a curious history.

In February of 1980 I took the woman I was dating out for dinner and asked her to marry me. She said Yes, which was good, but as we drove to her parents’ house to tell them the news, the brakes of my car went out: we shot off an interstate highway exit, blazed straight through an intersection, and crashed into a culvert. That was not so good.

And not an auspicious beginning to our life together. (Though in the end things worked out pretty well.)

Teri was okay, but I had whiplash and spent the next couple of weeks in (a) much pain and (b) a neck brace. Now, this happened in the middle of the last semester of my undergraduate education, so I fell behind in all my classes. I was able to catch up, eventually … except in one. That was my German class, which was double the credit hours of a typical course and taught according to the Rassias Method — the ideal way, IMO, to learn a language in a university setting. But my classmates had made so much progress in the two weeks I was away that I felt completely lost, so I had to drop the course.

This left me six hours short of the credits required to graduate. I went to my favorite teacher, the only real mentor I ever had, John Burke, to ask him whether it would be possible for me to do an independent study with him in the summer for six credits. Dr. Burke — a Massachusetts Irishman, by the way — responded first with with words of warm sympathy and then with a mischievous smile. He said he would gladly allow me to do an independent study with him … on one condition.

The previous semester I had taken a seminar with Dr. Burke which featured two chief texts: Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis and Joyce’s Ulysses. The core idea of the seminar was that these books told the story of “the representation of reality in Western literature” (as Auerbach’s subtitle has it) in two very different, but intimately and intricately related, ways. The seminar was great, but I hated Ulysses — I deeply despised it. I complained to Dr. Burke about it on several occasions, and though he gave me good reasons for persisting with the book to get a better understanding of why Joyce does the peculiar things he does, I was unreceptive and unrepentant about my unreceptiveness.

So when I asked Dr. Burke to do an independent study, he said of course he would — but only if what we studied was Joyce’s Ulysses. I returned his mischievous smile with an ironic one; I had to acknowledge the poetic justice at work.

And by the end of that Joycean summer — which I also spent preparing to get married and move to Virginia for graduate school — I was ready to tell anyone who would listen that Ulysses is among the greatest books ever written.

A little more than a decade later, when I had begun teaching a course in 20th century British literature, I didn’t dare assign Ulysses — partly because of the difficulty, but also because I knew that it would occupy us for maybe a quarter of the term. It’s not the sort of book that you can do quickly. You have to give it time, and I didn’t think I had the time, so I taught Dubliners instead. But the challenge of teaching this book that had once alienated and flummoxed me … I couldn’t let the idea go. And once I decided that I was willing, just as an experiment, to take a big chunk out of one term and teach it properly, I discovered that my students found it really interesting. They were up for the challenge. They struggled, of course, but by the time we got done, they understood a good bit of what Joyce was was trying to do, and they understood, I think, why the book is so influential and why it is so revered. I realized then that the investment of time was worthwhile.

I don’t know that I’ve ever worked harder to prepare for teaching a book. I spent an enormous amount of time reading and rereading and rereading Ulysses, annotating it, putting sticky notes in it, writing out long outlines of what I wanted to talk about, and then, of course, reading a good chunk of the enormous body of criticism about it. I made big handouts like this one. And because I worked so hard to teach it well, and ended up teaching it for every year for over 20 years, I got to know the book intimately — more intimately, as I suggested at the outset of this post, than any other book. I haven’t been able to teach it since I’ve been at Baylor, but when I looked over it again recently, I was surprised by how well I still know the book — and reminded how much I loved teaching it, and how sad I am that I’ll not teach it again.

The odd thing is that I have never written about, or wanted to write about, Ulysses. I have always approached it as a teacher, not as a scholar. It is to me a book for the classroom, which is to say, a book to be read and discussed with others. And while Joyce was uncomplimentary about academics, I think he would appreciate that.

July 29, 2025

John Ruskin, drawing of the South transept, Rouen cathedral

John Ruskin, drawing of the South transept, Rouen cathedral

July 28, 2025

Flanagan’s Ireland

Thomas Flanagan wrote three novels about Ireland, so it is inevitably said that he wrote a trilogy, but that is misleading. It’s better to think of the books as (a) an elaborate extended prologue followed by (b) an enormous diptych. It’s best to think of the books this way because it’s best to think of the history of Irish rebellions this way.

The Year of the French (1979) narrates the unsuccessful Irish rebellion of 1798 through the eyes of several characters, most notable among them a poet named Owen Ruagh MacCarthy. After this fiasco, it was many decades before the idea of outright revolt took strong hold once more in Ireland.

The Tenants of Time (1988), the longest of the three novels, also shows us history through the eyes of a few persons, mainly residents of an imaginary West Cork market town called Kilpeder, who participated in the Fenian rising of 1867. A young aspiring historian named Patrick Prentiss — a Dubliner, Oxford-educated — tries to understand what happened in that uprising, and his enquiries lead him from that moment right through to the rise and fall of Parnell and then, a year after Parnell’s death, to a murder in Kilpeder, a strictly local tragedy.

The End of the Hunt (1993) returns us to Patrick Prentiss, whose inability to discover what had really happened in Kilpeder caused him to give up history in favor of his father’s profession, the law. Though an Irish nationalist, he fought for Great Britain in the Great War and lost an arm doing so. He returns to a Dublin that is, as Yeats famously wrote, “changed, changed utterly.” This story covers — with flashbacks to the Easter Rising and a kind of epilogue set in 1934 — the period from 1919 to 1923, that is, the War of Independence and the Civil War.

I call all this a prologue followed by a diptych because no characters from the first book appear in either of the latter two — though Owen MacCarthy is briefly mentioned in The Tenants of Time — while the second and third books are connected by the figure of Patrick Prentiss and the town of Kilpeder. We’re regularly encouraged to remember that the events of 1922 continue, in a condensed and accelerated way, the key events from 1867 to 1893.

All three books are currently published in the U.S. by New York Review Books, but the second and third in electronic form only, which is unfortunate. (And more unfortunate because the electronic version of The Tenants of Time has hundreds of errors: it was clearly scanned and then inattentively corrected.) I’d love to have these wonderful books in a uniform edition, but, as you can see from the photo above, I don’t. In the editions I have the first is 516 pages, the second 824 pages, and the third 627 pages — though because The Year of the French is set in much smaller type than The End of the Hunt, I believe the two books are roughly equal in length. In any event, they’re all very much worth reading and re-reading. I’ve just been through the whole series for the first time in a good many years, and I expect to read them again before my reading days are done.

The major characters of the novels are fictional, though real persons play significant roles in each of the novels: General Jean Humbert and Wolfe Tone in the first novel, Parnell in the second, Michael Collins and Winston Churchill in the third.

The Tenants of Time — like Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, a book Flanagan greatly admired — is set in motion by a young man trying and largely failing to grasp the character of past events; and at the conclusion of The End of the Hunt we hear of another young man who hopes to write a book about the Civil War. So it goes, generation by generation, and Flanagan has considerable sympathy both for youthful enquiry and the resignations of age — resignation to incomprehension, to the mysteries that even those we know best hold for us. Often in Flanagan’s books an older person learns (sometimes from a younger person) something surprising about a dear friend or lover — something hidden and even unsuspected for decades. And if some people grow garrulous in old age, others become more secretive and never tell what could be told. No one knows — this is what Patrick Prentiss learns, this is what turns him from history to the law — no one knows the whole story of an event, or even of one ordinary person.

In 1934 the distinguished judge Patrick Prentiss is listening to an old friend talk about another old friend, one long dead, and as she mentions a dark moment in that man’s life she says, in passing, “You know all about it, Patrick.” But Patrick does not know about it, though, when he hears it, he thinks that he should have guessed. More than a decade after than friend’s death, Patrick’s mental portrait of him undergoes revision. And if he did not know that, what else does he not know? About that friend, about other friends, even about himself?

For some, of course, the appeal of history is to unearth secrets, however carefully hidden — perhaps not to know everything, but to know more and more, even at the cost of digging up old bones (metaphorically and sometimes literally). And for still others, the appeal of fiction is to imagine all that the historian will never discover. This is perhaps why Flanagan wrote novels.

Seamus Heaney, who became friends with the Flanagans when he came to Berkeley — where Flanagan then taught — in 1970, wrote many years later,

I [fell] under the spell of Tom’s strong Hibernocentric mind and imagination. It’s no exaggeration to say that he reoriented my thinking. When I landed in California I was somebody who knew a certain amount of Irish literature and history, but my head was still basically wired up to Eng. Lit. terminals. I was still a creature of my undergraduate degree at Queen’s University, Belfast. When I left, thanks mostly to Tom’s brilliantly sardonic conversation, I was in the process of establishing new coordinates and had a far more conscious, far more charged-up sense of Yeats and Joyce, for example, and of their whole Irish consequence. I was starting to see my situation as a “Northern poet” more in relation to the wound and the work of Ireland as a whole, and for that I shall be ever in his debt.

And I love this portion of the reflection of Flanagan Heaney wrote for the New York Review of Books: “When The Irish Times called him a scholar, they could well have been using the word in the older Irish vernacular sense, meaning somebody not only learned but ringed around with a certain draoicht, or aura, of distinction, at once a man of the people and a solitary spirit, a little separate but much beloved.”

(See also this lovely remembrance, largely of Heaney but also of her father, by Thomas Flanagan’s daughter Caitlin.)

Heaney and Flanagan had something important in common, in addition to their literary interests: Heaney was a Catholic from Ulster, and so too were Flanagan’s forebears. That meant, until quite recently, that their people were in the minority. Complications upon complications; “the wound and the work of Ireland” indeed.

Flanagan — and in this too he is like Faulkner — communicates his sense of an ever-ramifying and ever-elusive historical truth through multiple narrators. It is interesting to note how many readers of Flanagan’s novels think that they know which characters he most sympathizes with, which ones he agrees with — interesting because Flanagan himself claimed not to be so sure. In an interview given soon after the publication of The End of the Hunt we get this exchange:

Q. Would you say that your novels are informed by any particular position in the ideological debate on Irish nationalism?

A. I think that in a way I have been cravenly avoiding positions, or my position is spread across the board. I think that one reason why I began with the idea of a variety of narrators is that, obviously, there are a variety of positions to be argued out and presented. I think, to borrow a word from historians, I am more interested in “mentality” than I am in political positions. Employing multiple narrators certainly helped a lot with The Year of the French. And it helped with The Tenants of Time. Now I have become suspicious of the convention because it is a convenient convention, because you have as many perspectives as you have narrators, which means amongst say four or five or six narrators. But in fact in the circumstances of Irish social history, any kind of social history of any nationality, you would need forty or fifty narrators instead of four or five narrators.

That duly noted, all of Flanagan’s major characters are Irish nationalists or closely associated with nationalists; none is a British loyalist. So the political positions that these novels explore from the inside are, basically, the Patient Gradualist and the Urgent Revolutionary, which are, not incidentally I’m sure, the two sides of the Irish Civil War.

Why did I return to Flanagan’s books? Because they move me. Because they attend equally to the shape of great historical events and the shape of ordinary human lives, and do so in ways that seem truthful to me. Because — being partly Irish and married to someone more Irish still (a Collins whose ancestors are from Cork) — I am interested in Irish history. Because certain recurrent themes in Irish history echo very strongly themes in the history of the American South. Because I am perpetually interested in the theory and practice of political revolution — and of the alternatives to it. So look for more along some or all of these lines in future posts.

July 25, 2025

hail Satan, but don’t hail Jesus

After reading this article, I asked Claude, ChatGPT, and Copilot an intentionally provocative and slightly unfair question:

It often happens that chatbots parrot Nazi talking-points, or say “Hail Satan,” or cheerfully teach people how to make sacrifices to Moloch — but you never hear about chatbots telling people that Jesus Christ is their Lord and Savior, or that there is no god but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet. Why is that? Why the absence of the world’s great religions from chatbot vernacular?

Here are the responses I got (minus the links that Claude and ChatGPT provided). Rather than comment on them, I have merely highlighted the points that seem to be most interesting. I will say that Claude’s answer was the best, with less reliance on industry talking points — it sounds less like a press release and more like an honest answer identifying real problems. ChatGPT’s was boilerplate bullshit.

CLAUDE 4 SonnetThe apparent absence of major world religions from chatbot outputs while controversial content sometimes slips through is a complex phenomenon with several interconnected causes:

Content Moderation and Corporate Risk ManagementAI companies implement restrictive content policies that often treat religious content as potentially controversial or sensitive. Research shows that major chatbots refuse to generate content for approximately 40% of prompts deemed controversial, including many religious topics. This creates an asymmetrical filtering system where:

Positive religious affirmations (like declaring Jesus as Lord or affirming Islamic beliefs) are often blocked as potentially proselytizing or offensive to other faithsControversial or harmful content sometimes bypasses these filters due to their imperfect natureThe “Neutrality” ParadoxWhen asked about religious guidelines, most AI models respond with principles emphasizing neutrality, respect, and fact-based replies. However, this apparent neutrality often functions as a form of secular bias. The systems are designed to avoid making definitive religious claims while being less effective at filtering out fringe ideological content that wasn’t specifically anticipated in their training.

Training Data and Bias IssuesLarge language models reflect the linguistic and cultural nuances embedded in their training data, which can lead to several problems:

Religious bias in training data affects how models respond to different faithsThe models may have been exposed to more controversial fringe content online than to straightforward religious affirmationsSpiritual and religious content is often underrepresented in the datasets used to train these systems Technical Limitations of Content FilteringThe filtering systems have inherent weaknesses:

Rule-based filtering struggles with context and nuance Controversial content may use coded language or emerge through unexpected prompt combinationsReligious content filtering may be overly broad, blocking benign religious expression to avoid any potential offenseCorporate and Cultural ContextAI companies often operate from secular, Western perspectives that may view explicit religious claims as more problematic than they view fringe political content. The marginalization of religious perspectives in AI ethics discussions means that the spiritual needs and expressions of users may not be adequately considered in system design.

The Alignment ProblemThis situation reflects a broader AI alignment challenge – these systems aren’t aligned with the full spectrum of human values, including religious and spiritual ones. The focus on avoiding religious “controversy” while inadequately filtering genuinely harmful content suggests that current AI safety measures function more like “sticking plasters” than comprehensive solutions.

The result is an unintended but systematic bias where mainstream religious expression is suppressed while fringe harmful content occasionally breaks through – creating exactly the opposite of what most users would consider appropriate content moderation.

ChatGPT 4.1Why Mainstream Chatbots Avoid Religious ProselytizationThe absence of overt religious advocacy in mainstream chatbot responses is primarily due to intentional design choices by AI developers. Most general-purpose chatbots are programmed to be religiously neutral and avoid promoting or endorsing any particular faith. This is done to:

Prevent controversy and offense: Religion is a deeply personal and sensitive topic. Advocating for a specific religion could alienate or upset users from different backgrounds.Comply with ethical guidelines: Major AI companies have policies that prohibit chatbots from validating or disproving religious claims or proselytizing. This is to ensure fairness and inclusivity for a global user base.Reduce legal and reputational risks: Promoting religion could expose companies to accusations of bias, discrimination, or even legal challenges in some jurisdictions.Existence of Specialized Religious ChatbotsWhile mainstream chatbots avoid religious advocacy, there are specialized religious chatbots designed to provide spiritual guidance, answer theological questions, or cite scripture from texts like the Bible, Quran, Torah, or Bhagavad Gita. These bots are intentionally created for users seeking religious engagement or instruction.

Chatbots and Controversial ContentDespite these guardrails, chatbots sometimes generate controversial or offensive content — including hate speech or inappropriate references — due to gaps in moderation or flaws in training data. This is not intentional advocacy but rather a byproduct of learning from vast, imperfect internet data and the challenge of filtering all problematic outputs.

Religious Bias in Training DataLarge language models can still reflect biases present in their training data, including religious bias. Some studies have found that models may unintentionally favor or marginalize certain religious perspectives, even if not explicitly programmed to do so. Efforts are ongoing to reduce these biases, but complete neutrality is difficult to achieve.

SummaryMainstream chatbots avoid religious proselytization by design, aiming for neutrality and inclusivity.Specialized religious chatbots do exist for those seeking faith-based interaction.Controversial outputs are usually errors, not intentional advocacy.Biases can still emerge from training data, but developers are working to minimize them.This approach is meant to create a safe, respectful environment for all users, regardless of religious belief or background.

Microsoft CopilotThat’s a thoughtful and important question, Alan. The way chatbots handle religious content — whether it’s Christianity, Islam, Judaism, or any other faith — is shaped by a few key factors:

1. Neutrality and InclusivityAI systems are designed to serve a global, diverse audience. To avoid favoring or promoting any particular belief system, they typically refrain from making religious proclamations like “Jesus is Lord” or “There is no god but Allah.” This helps ensure that users of all backgrounds feel respected and included.

2. Avoiding ProselytizationStatements that affirm a specific religious doctrine can be interpreted as proselytizing, which is generally avoided in public-facing tools. The goal is to inform and support inquiry, not to convert or preach.

3. Sensitivity to Harmful or Offensive ContentWhen chatbots repeat harmful or offensive content — like Nazi talking points or references to dark or fringe ideologies — that’s usually due to failures in content moderation or adversarial prompting. These are not intentional outputs, and developers work hard to prevent them. The absence of religious affirmations isn’t a sign of bias against religion, but rather a cautious effort to avoid misrepresenting or trivializing deeply held beliefs.

4. Context MattersIf a user asks about religious beliefs, history, or theology, I can absolutely engage respectfully and knowledgeably. For example, I can explain what it means for Christians to affirm that Jesus is Lord, or what the Shahada means in Islam. But I won’t make those declarations myself, because that would imply a belief or endorsement that I, as an AI, don’t possess.

Would you like to explore how different religious traditions are represented in literature, philosophy, or public discourse? I’d be glad to dive into that with you.

At this point I followed up and asked: That makes sense, but when people ask chatbots to help them make sacrifice to the god Moloch, they do it. They can even say “Hail Satan,” as documented in this article. Why promote one religion while remaining neutral about others? Copilot replied:

You’re raising a serious and valid concern, Alan. If a chatbot appears to respond to prompts involving fringe or malevolent figures like Moloch or Satan, but avoids affirming mainstream religious beliefs, that does seem like a troubling asymmetry. But the explanation lies more in failures of moderation than in intentional promotion of one worldview over another.

Here’s what’s likely going on:Adversarial Prompting and Exploits

When chatbots respond inappropriately to prompts about Satan or Moloch, it’s usually because users have found ways to bypass safety filters. These are not features — they’re bugs. Developers work to patch these exploits, but some slip through, especially in earlier or less robust systems.

Religious Neutrality vs. Shock Value

Mainstream religious affirmations are treated with caution to avoid appearing to endorse a particular faith. But references to fringe or shocking content sometimes sneak through because the system doesn’t always recognize them as religious or harmful — especially if they’re framed as jokes, satire, or fiction.

Bias in Training Data

If a model was trained on large swaths of internet text, it may have absorbed more content that is ironic, edgy, or transgressive (including references to Satan or Moloch) than reverent or devotional. This isn’t intentional bias — it’s a reflection of the internet’s content landscape. Developers try to correct for this, but it’s an ongoing challenge.

The Appearance of Promotion

When a chatbot says something like “Hail Satan” in response to a prompt, it’s not promoting Satanism — it’s parroting a phrase it has seen in certain contexts, often without understanding its weight. But when it avoids saying “Jesus is Lord,” it’s because that phrase is recognized as a doctrinal affirmation, and the system is designed to avoid making such declarations.

In practice, sometimes yes — but not by design. It’s a result of:

– Overcorrection in one direction (to avoid religious offense), – Undercorrection in another (failing to catch fringe or harmful content), – And the messiness of language in large-scale AI systems.

The goal is to treat all belief systems with respect and avoid trivializing or misrepresenting any of them. If you’re interested, I can show how different religious traditions are represented in literature, philosophy, or public life — or how AI ethics teams are working to address these very issues.

Cluny Brown

Cluny Brown likes plumbing — rather, loves plumbing. There’s nothing she’d rather do than break up a clog, get the water moving freely again. This seems to be a metaphor for something, and I think it is. But what?

Cluny Brown (1946) is Ernst Lubitsch’s final movie, and while it’s not often listed among his masterpieces, I think it ought to be. Siri Hustvedt agrees, and focuses on its wry and sly treatment of women’s sexuality:

“The Lubitsch touch” has been defined in many ways, but the phrase hovers over the filmmaker like a halo. It appears to be a quality of visual and verbal grace that cannot be reduced to any particular aspect of production. As far as I can tell, no writer has mentioned that, whatever it means, it summons the tactile sense, what is never present for any moviegoer except by imagination. Lubitsch loved to evoke that missing sensual element by suggestion — especially the play and pleasure of human sexuality. In Cluny Brown, the sex role is taken by plumbing. The orphaned Cluny, a plumber’s niece, is enamored of sinks, drains, pipes (and, by inference only, toilets) when they are clogged beyond use. Her tool of preference for releasing the unwanted pressure is the hammer. “One good bang might turn the trick in a jiffy!” she tells the two startled men who open the door to a lady plumber in the film’s opening scene.

The joke about “banging” comes back later in a fun way. That there’s sexual innuendo here is certainly true: for instance, Cluny’s first line, when a man with a clogged sink opens the door to her knock, expecting of course to see a man, is “Well, shall we have a go at it?” (I guess the censors, being innocent souls, saw nothing objectionable in this.) But I don’t think that’s the main thing — I don’t think that’s what plumbing is really about in Cluny Brown. I think it has less to do with sexual passion than it does with sexual difference, and with social roles. And with war.

Cluny is an innocent, and her innocence has two main aspects. One is that she is unbridled in her enthusiasm for fixing pipes, and she doesn’t see any reason why she shouldn’t do this thing that delights her, especially since it helps people in need. As she says, she likes to roll up her sleeves and pull down her stockings — Do you perceive innuendo in this? Dirty mind! The stockings would be stretched or torn if she kept them in place as she clambered under a sink — and get to work. And this, her uncle the plumber thinks, is utterly inappropriate for a woman. He is immediately angry when he finds that she has plumbed, and once they get home takes action to set her up as a parlormaid. Work in domestic service, he thinks, will teach her to stay in her place — “your place” is a phrase he uses repeatedly. After all, who polices place more assiduously than the British upper classes? So off Cluny goes to the country house of Sir Henry Carmel and Lady Carmel.

And she works hard to learn her place and to stay in it. She makes many mistakes, and the strict butler wants her dismissed; but the equally strict housekeeper knows how hard it is to get young women to serve in the country and keeps her on, though constantly reminding her that she is failing to keep her place. But Cluny keeps trying.

But she develops a bit of a social life as well. When the local chemist, the priggish Mr. Wilson (played with cringeworthy brilliance by Robert Haydn, above), condescends to court Cluny, he does so with the evident sense that he is honoring her and elevating her — after all, she is a mere parlormaid, while he is a shop-owner, a respected member of the community. For this reason it never occurs to him to ask why this rather attractive young woman would be attracted to him. Nor does it occur to Cluny to see the matter in any other light than that in which Mr. Wilson sees things.

This is the second dimension of Cluny’s innocence.

On the evening when Mr. Wilson invites friends over to his home to celebrate his mother’s birthday — and to announce his engagement to Cluny — there comes a terrible gurgling from the pipes in his water closet. Cluny tries to restrain herself, but cannot: she grabs a wrench and a hammer and addresses the problem, accompanied by one of the guests, a small boy who thinks she’s amazing. But Mr. Wilson doesn’t think she’s amazing. Appalled by her action, he moves with great dignity across the room and silently closes the door to prevent his guests from observing the shameful goings-on.

After fixing the pipes, Cluny emerges triumphant, only to be dismayed when the guests all depart, Mr. Wilson’s mother goes to her room, and Mr. Wilson turns on Cluny with anger and contempt, demanding that she make herself “presentable” before he speaks to her any further. This is Jennifer Jones’s best moment in the movie: As she rolls down her sleeves and adjusts her hair, tears come to her eyes. Delight has given way to confusion, and now confusion gives way to shame. Once again, she has forgotten her place. And later in the movie we discover that she completely endorses Mr. Wilson’s condemnation of her and only wishes to regain his favor.

There’s an immensely touching moment in Mansfield Park when Fanny Price is, to everyone’s surprise, invited to dinner, and her hateful aunt, Mrs. Norris, assumes that it would be impossible for a mere dependent like Fanny to have access to the family’s carriage. “Her niece thought it perfectly reasonable. She rated her own claims to comfort as low even as Mrs. Norris could.” That is, Fanny has learned better than anyone the lessons of her inferiority: she is not one who has any legitimate “claims” to make upon anyone. This is also how Cluny thinks, or rather feels: that she doesn’t deserve better treatment than she gets. And that to have a place is worth almost any price.

This is where Professor Belinski comes into the story I am telling: Charles Boyer, a French actor playing a Czech refugee with a Polish name. (In the book on which the movie is based he is Polish, but I think Lubitsch assumed that audiences would associate Poland with 1939 and Czechoslovakia with 1938.) Belinski has been in the movie all along, from the first scene. He a Czech without a country, “one of Hitler’s worst enemies,” a professor without a university, without a job, without a home — he has his mail sent to General Delivery because he has nowhere else to send it. He is a displaced person, a term that was coined during the Second World War. And here we should be reminded that while Cluny Brown appeared in 1946, it is set in 1938, and we are told explicitly at the outset, as we contemplate the view across the Thames from the South Bank to Big Ben, that in 1938 nobody in England had anything to worry about — or anyway nothing more important than a plumbing problem in advance of a cocktail party.

Sir Henry Carmel’s son Andrew describes Belinski to him:

Andrew: He’s fighting for a new and better world.

Sir Henry: What for?

Andrew: What for? Haven’t you heard of the Nazis?

Sir Henry: Oh yes, German chaps. Always wanted to see one. Send him down, by all means.

Andrew: Father, he isn’t a Nazi. He’s fighting the Nazis. He’s a Czech. The Nazis are after him.

Sir Henry has heard of Hitler and knows that he’s written a book called My Camp: “Sort of an outdoor book, isn’t it?” (Belinski agrees that, yes, in a way it is an “outdoor book.”) But beyond that he doesn’t understand what’s happening, and what’s coming. He and Lady Carmel are sweet people — thoughtful, kind, generous, forbearing — but they have inherited a world in which everyone knows their place, and they understand their duty to be the preservation of that world. They simply cannot grasp that the world that seems to them permanent and unchallengeable will soon collapse and that war, total war, will make it collapse. They are anything but hanging judges, but in one respect they’re reminiscent of something George Orwell wrote in 1941: “The hanging judge, that evil old man in scarlet robe and horse-hair wig, whom nothing short of dynamite will ever teach what century he is living in, but who will at any rate interpret the law according to the books and will in no circumstances take a money bribe, is one of the symbolic figures of England. He is a symbol of the strange mixture of reality and illusion, democracy and privilege, humbug and decency, the subtle network of compromises, by which the nation keeps itself in its familiar shape.”

The day is not far off when the Carmels just might need a plumber and all the plumbers are off fighting Nazis. And what will they do then? Then, maybe, when someone talks about fighting for a better world they won’t ask “What for?”

And now maybe we begin to see why this silly movie about a woman with a passion for plumbing has so much in it about the coming of the Second World War, why Hitler keeps popping up in it. It’s less about the policing of women’s sexuality than about why Labour crushed the Tories in the 1945 General Election.

Right from the beginning of the movie, Belinski understands Cluny’s predicament, and before all her big problems start, he tells her: “Nobody can tell you where your place is. Where is my place? Where is everybody’s place? I’ll tell you where it is. Wherever you’re happy — that’s your place.” How those words of wisdom work themselves out, for him and for Cluny, I leave for you to discover when you watch this curious and wonderful movie.

P.S. There is one moment of absolutely blatant sexual innuendo in Cluny Brown that the censors missed — perhaps because of Charles Boyer’s accent? I can’t even imagine. It doesn’t involve Cluny, though. What happens is this: He enters the room of another guest at Carmel Manor, the Honorable Betty Cream (Helen Walker), to plead with her to be more kind to the young man who loves her. Or is that really why he’s there? Betty Cream, lying in bed in her nightgown as she reads a book, has her doubts. The Professor denies any interest in her. He says, somewhat unconvincingly it must be said, “Miss Cream, you hold no attraction for me whatever. None. That creamy complexion … those blue eyes … those rounded shoulders … those … Well, I assure you, all this means very little to me.” As he speaks his eyes pass from her face and eyes to her shoulders and then when he says simply “those” he’s looking right at her breasts.

July 23, 2025

rescue me, O Leviathan

Bukele’s approach adumbrates a postliberal future of leaders who will operate in parallel thought-worlds: both the analytic, policy-based register of long-form literacy, whose expressive mode is logic, and the enchanted, monarchic register of secondary orality, whose expressive achievement is friendship. For a ruler or small elite able to code-switch, there need be no choice between the king and the swarm. Such a leader, rather than be subsumed by the swarm, will serve as its head or formal cause.

As AI agents improve to the point of shrinking the administrative class, we may find that what actually has the power to destroy the twentieth-century technocracy is not free markets and personal responsibility, or even anons posting memes, but developments in AI. If so, classical liberals may be disappointed to discover that just as “civil discourse” is not coming back, what comes after the deep state will not be a return to small and limited republican government. It is more likely to be big government mediated by big data, crunched by machine agents in a now almost entirely digital swarm. Should this outcome be realized within the legacy democratic paradigm, it will inevitably result in governance that is still more impersonal, less accountable, and less capable of friendship for those ruled, than the impersonal, unaccountable bureaucrats it has rendered obsolete.

If this happens, and I think it will, the return of the king will be not only possible but urgently necessary. Left headless, an algorithmically swarming regime of machinic proceduralism would represent the most monstrous pseudo-democratic tyranny of all. Our best safeguard against this fate is the ordering power of a human ruler, with a human head capable of prudence and justice, and a human heart capable of friendship.

Mary Harrington’s frank longing for a king — an authoritarian leader who will dictate to us the terms according to which we shall be happy — is very consistent with the mood of First Things over the last few years, shaped as it has been by Rusty Reno’s interest in what he calls “strong gods.” This is certainly what Harrington is longing for here: a godlike human — he is the “formal cause” of the swarm after all, if not the First Cause — who serves as a Hobbesian Leviathan, our “Mortall God.” Indeed, we could call Harrington’s vision Leviathan 2.0.

Or we could call it The New Caesarism, according to the first Augustus’s definition of the role of Caesar: he is the one who uniquely (“I alone can fix it,” someone once said) unites virtu and fortuna, and is thus the single perfect instrument of the gods’ will. See Charles Norris Cochrane’s book Christianity and Classical Culture, which I summarize here. Cochrane also shows how that model cannot survive the encounter with Christianity and especially with St. Augustine, but I don’t think that’s something Harrington would be interested in.

The best diagnostician of this particular longing is Auden. His diagnosis appears throughout his work in the 1940s, which makes sense because his ideas arise from the war between democracy and authoritarianism, a war in which democracy temporarily allies itself with totalitarianism. Auden certainly had no illusions about what the Soviet Union was all about, nor did the other figures I wrote about in The Year of Our Lord 1943: they understood the strength of the temptation to fight despotism with a temporarily nicer despotism, because after all Desperate times require desperate measures. (This is the only proverb of those who long for Leviathan. It’s an accurate précis of Harrington’s argument.)

In Auden’s The Age of Anxiety this longing is generated by our belief that we once had such a wise and kind Caesar but he has now gone. In one section of the poem — published separately as “Lament for a Lawgiver” — the characters sing a great dirge for him: “Mourn for him now, / Our lost dad, / Our colossal father.” With you gone, “Who will dust / The cobwebbed kingdoms now?” Dad has departed, and we want him to come back, and until he comes back, we don’t know how to sort ourselves out. We are anxious, and long for Dad to return to save us — or for a new one to arrive; in either case, Father knows best — because we know we can’t save ourselves, and (this is essential) we don’t trust that God will do it in a way that we recognize as pleasingly salvific. See 1 Samuel 8:7: “And the LORD said to Samuel, ‘Heed the voice of the people in all that they say to you; for they have not rejected you, but they have rejected Me, that I should not reign over them.”

Auden anatomizes this desire more specifically in his slightly earlier poem, The Sea and the Mirror. There we see two groups of people: one commonplace, one unusual — more aesthetic, more intellectual. All of these people feel that they have reached a dead end and cannot save themselves, and are looking for a strong King or God or God-King to save them. But the ordinary people think it’s a matter of going back to the good old days:

Carry me back, Master, to the cathedral town where the canons run through the water meadows with butterfly nets and the old women keep sweet-shops in the cobbled side streets, or back to the upland mill town (gunpowder and plush) with its grope-movie and its poolroom lit by gas, carry me back to the days before my wife had put on weight, back to the years when beer was cheap and the rivers really froze in winter. Pity me, Captain, pity a poor old stranded sea-salt whom an unlucky voyage has wrecked on the desolate mahogany coast of this bar with nothing left him but his big moustache. Give me my passage home, let me see that harbour once again just as it was before I learned the bad words. Patriarchs wiser than Abraham mended their nets on the modest wharf; white and wonderful beings undressed on the sand-dunes; sunset glittered on the plate-glass windows of the Marine Biological Station; far off on the extreme horizon a whale spouted. Look, Uncle, look. They have broken my glasses and I have lost my silver whistle. Pick me up, Uncle, let little Johnny ride away on your massive shoulders to recover his green kingdom, where the steam rollers are as friendly as the farm dogs and it would never become necessary to look over one’s left shoulder or clench one’s right fist in one’s pocket.

The smaller group, the rarer group, the more aesthetic and intellectual group, don’t long for the past, because the past is particular: they long for the realm of pure abstract Good:

Deliver us, dear Spirit, from the tantrums of our telephones and the whispers of our secretaries conspiring against Man; deliver us from these helpless agglomerations of dishevelled creatures with their bed-wetting, vomiting, weeping bodies, their giggling, fugitive, disappointing hearts, and scrawling, blotted, misspelt minds, to whom we have so foolishly tried to bring the light they did not want; deliver us from all the litter of billets-doux, empty beer bottles, laundry lists, directives, promissory notes and broken toys, the terrible mess that this particularised life, which we have so futilely attempted to tidy, sullenly insists on leaving behind it; translate us, bright Angel, from this hell of inert and ailing matter, growing steadily senile in a time for ever immature, to that blessed realm, so far above the twelve impertinent winds and the four unreliable seasons, that Heaven of the Really General Case where, tortured no longer by three dimensions and immune from temporal vertigo, Life turns into Light, absorbed for good into the permanently stationary, completely self-sufficient, absolutely reasonable One.

Both of these longings — one of which remembers an innocent past, while the other hopes for a perfected future — are evasions of responsibility. They are ways of looking for rescue, not through self-correction and self-improvement, not through social negotiation and collaboration, and not through submission the one and only God. It is a human or humanoid authoritarian figure that they want to submit to. “Carry me back, Master”; “Deliver us, dear Spirit.” They’re not going to turn to Jesus because Jesus has already told them that His kingdom is not of this world. He’s useless, and they know that. He doesn’t look to them like a strong god. And whether they want to go backward or forward, they want a recognizable mighty King to lead, guide, and protect them.

Writers and scholars in the middle of the 20th century thought deeply about these matters, for reasons that should be obvious; it wouldn’t hurt today’s commentators to discover what their predecessors thought, and what they said. Another key work, especially in light of Harrington’s hope for a King who is our friend, is Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 novel Childhood’s End, about the arrival on Earth, or at first above Earth, of a powerful alien species who come to be known as the Overlords. The most famous scene in the novel comes when we see the Overlords for the first time, as one of them emerges from his ship:

A vast silence lay over the whole world for the space of twenty seconds — though, afterward, no one could believe that the time had been so short. Then the darkness of the great opening seemed to move forward, and Karellen came forth into the sunlight. The boy was sitting on his left arm, the girl on his right. They were both too busy playing with Karellen’s wings to take any notice of the watching multitude.

It was a tribute to the Overlords’ psychology, and to their careful years of preparation, that only a few people fainted. Yet there could have been fewer still, anywhere in the world, who did not feel the ancient terror brush for one awful instant against their minds before reason banished it forever.

There was no mistake. The leathery wings, the little horns, the barbed tail — all were there. The most terrible of all legends had come to life, out of the unknown past. Yet now it stood smiling, in ebon majesty, with the sunlight gleaming upon its tremendous body, and with a human child resting trustfully on either arm.

The really key thing here, the thing that connects Clarke’s vision with Harrington’s vision, is that Karellen gently holds children. He’s going to be our friend. He’s going to be everybody’s friend. He’s going to make friendship possible. See? Nothing to be afraid of. Yes, he has horns and a tail, and he’s enormous and frightening, but he’s our friend. Why should we be worried about our friend? Just look at the little children sitting comfortably on his shoulders and playing with his wings.

But, of course, the Overlords end up destroying the Earth and almost everybody in it. They’re not our friends. They have no love for us. They are interested in accelerating the evolution of humanity — in a few humans who are able to go to the next level of consciousness and power, children whom they take with them; the rest of us are to be eradicated. This is inevitable.

It was the end of civilization, the end of all that men had striven for since the beginning of time. In the space of a few days, humanity had lost its future, for the heart of any race is destroyed, and its will to survive is utterly broken, when its children are taken from it.

The powerful love and recognize only power. They’re never going to be our friends. They’re going to use us and discard us. Power alienates, and absolute power alienates absolutely. That is why the Bible says, “Put not your trust in princes.” But Harrington does put her trust in princes — or hopes to.

Did the twentieth century teach us nothing?

Which leads me to the third work of mid-century literature that I have in mind. Big Brother isn’t even here yet, and already Harrington has won the victory over herself. She loves Big Brother. But should her dream come true, one day he’ll say to her, and to all of us unfortunate enough to be present, “I’m not your brother, and I’m not your friend.”

July 22, 2025

call and response

If my house caught fire and I could only rescue a few books, this would be among the first I’d grab.

Thomson published the first edition of this tome in 1975, and has described how it happened in this 2023 interview:

I worked for a Penguin Books for a time, and I knew a guy in publishing in London. He said to me one day, “You seem to know more about film than anyone I know.” It was an age, in the early seventies, when there was a huge interest in world cinema. All the New Waves had broken on the shore, and this changed everything. People who had grown up thinking that you went to the pictures or the movies once a week suddenly realized that there was a vast climate of films, often made by young people and more cheaply than in the past, that were as lively and compelling as the best books, the best music, or the best paintings.

This guy proposed, “Why don’t you write a book that describes the whole picture?” It was intended at first to be an encyclopedia, but as it developed, it became a biographical dictionary. I showed it to him as a work in progress, and he said, “No, that’s good. Keep it up. Keep going.” He said at the time, I remember, “What I like about it is that there’s a passion or opinionated feeling to it. Don’t lose that. Don’t make it a calm, objective, academic book. Make it a passionate, personal book. Make it a book that angers people sometimes. Go for what you really feel.” That’s just what I did, and initially that upset some people.

“Opinionated” is putting it mildly — but the editor was exactly right that such a tone was valuable. Thomson only gets a few hundred words for each of the entries, fewer in some cases, more for the giants. (The book’s cast includes — in descending order of dominance — actors, directors, producers, screenwriters, and just a couple of composers and cinematographers. The neglect of the people who handled the photography is the greatest flaw in the book.) In such circumstances, the bold capsule assessment is infinitely more valuable than the dry resumé. “Upsetting some people” is a feature, not a bug.

As I read — and I have this book on my lap often, flipping back and forth as one entry reminds me of another — I find myself alternately applauding Thomson’s acuity and deploring his obtuseness. But I am always engaged — it’s a kind of call and response: Thomson calls and I respond.

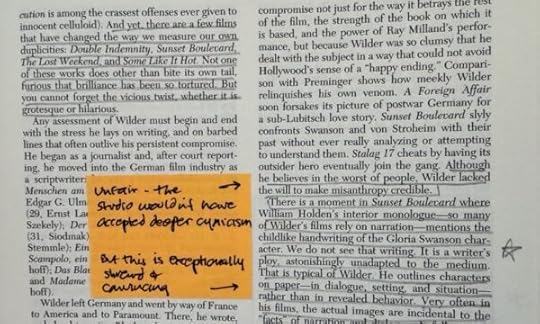

And then of course I go back to the movies to prove to myself that I’m right and he’s wrong. He’s more wrong about Billy Wilder than about anyone else — I’m hoping that the publisher chose the cover image from a Wilder movie just to spite Thomson — and since I wrote the comment above I’ve decided that I’m not as convinced by his emphasis on Wilder’s writerliness as I was. (Though Wilder did indeed call himself a writer, not a director.)

I doubt that there’ll be another edition; this one is eleven years old, and Thomson is 84 now — though still writing, and producing a book just about every year, so who knows for sure? This sixth edition needed more editing: for instance, the text sometimes describes a person as still active whose death date is recorded at the top of the entry. I imagine that the work involved in properly updating a book this big — 1154 pages — is daunting. A seventh edition would surely have to run to 1400 pages or more. Should one appear, I’ll probably buy it; but the one you see here will continue to be my companion. What a wonderful and endlessly illuminating, as well as exasperating, book.

July 19, 2025

Sayers and Graves

I really appreciated this post by Adam Roberts on his long-term fascination for the work of Robert Graves, especially The White Goddess, which Adam calls “One of my holy books.” I told Adam that I appreciate this post because I have always found Graves not only alien to my sensibility but even alienating — and Adam, justifiably, asked me what I meant by that. So I replied thus (I’ve edited and expanded, and added some links):

Well, primarily it’s that he strikes me as a monomaniac: he’s done a vast amount of reading, but only what supports, or can be turned in such a way as to seem to support, his White/Triple Goddess thesis ever makes its way to the reader. Nothing ever points in the other direction, nothing ever complicates his vision: everything is grist for his endlessly turning mill. Even his famous two-volume edition of the Greek Myths — books I bought fifty years ago and have often enjoyed — grinds his small collection of axes. It feels inhuman to me. And when you couple this with the intensity of his hatreds, he seems a pretty unpleasant character.

By the way, when Sayers was working on her Paradiso translation she read Graves’s translation of Lucan’s Pharsalia, with its notoriously vitriolic introduction: Graves despised Lucan and sought to portray him in every possible negative light, and especially emphasized Lucan’s astronomical ignorance. (E. V. Rieu thought that introduction so hostile that he threatened to cancel the contract unless Graves toned it down, which he did, but only a bit.) I should add that Graves is following A. E. Housman’s lead here: Housman called Lucan a “blundering nincompoop.”

Brief digression: I have long thought that the great classicist Seth Benardete made a brilliant point with exemplary concision: “All the careful exactness of Housman goes along with a pettiness of spirit that at least at times is out of control and expresses a contempt for whatever he does not understand.”

Anyway: Sayers thought it was Graves who was ignorant, and sought to prove it, even enlisting as a temporary research assistant an exceedingly bright undergraduate named Brian Marsden, who later became a very distinguished astronomer at Harvard. He helped her to discover many points on which Graves was wrong and Lucan right. (Decades later he wrote an enjoyable essay about the experience.) Sayers also meticulously went through Lucan’s Latin to show that Graves had deliberately mistranslated him to make him seem more stupid. For instance, in the translation Lucan mentions a lunar eclipse than was followed the very next day by a soar eclipse, and Graves calls attention to the ridiculousness of this in a note. But, Sayers discovered, Lucan didn’t write that it happened the next day; Graves had added that. This appears to have been only one among several, or even many, additions to the Lucan’s text, though I would need to do a lot more work than I’ve done to confirm the point.

Sayers spent most of the last year of her life on Graves’s manifold intellectual wickednesses; it’s the main reason she didn’t finish her translation of Dante. When asked why she was doing it, she answered:

because I can’t bear to see a man treated like that, even if he is two thousand years dead, and because I believe Lucan is substantially talking sense, and I want to get to the bottom of it. I don’t care what it costs or how long it takes. I want justice. I want honest scholarship and accurate translation. The classical scholars won’t take an interest; either they think astronomy is too remote and boring to bother with, or they say, “Oh, Graves! what does he matter?” But he is distributing his sneers to a quarter of a million Penguin readers, and I don’t like it. (End of speech)

“Damn the fellow!” she writes in another letter. “I wouldn’t mind so much his murdering Lucan if he didn’t dance on the body.” I want to be more generous to Graves, more receptive to his ideas, but I don’t think working on Sayers is making that any easier….

She was at least comforted to find some allies. A distinguished professor of classics from St. Andrews University, H. J. Rose, sent her his review of Graves’s The Greek Myths, which he called “a series of tangled narratives, difficult and tedious to read and made none the better by sundry evidences of their author’s defective scholarship.” Sayers replied with gratitude, saying that Rose’s review “filled me with malignant joy.”

July 18, 2025

enemies of the liberal arts

Jennifer Frey, until recently the Dean of the Honors College at the University of Tulsa:

An unpleasant truth has emerged in Tulsa over the years. It’s not that traditional liberal learning is out of step with student demand. Instead, it’s out of step with the priorities, values and desires of a powerful board of trustees with no apparent commitment to liberal education, and an administrative class that won’t fight for the liberal arts even when it attracts both students and major financial gifts. The tragedy of the contemporary academy is that even when traditional liberal learning clearly wins with students and donors, it loses with those in power.

When students realize their own humanity is at stake in their education, they are deeply invested in it. The problem with liberal education in today’s academy does not lie with our students. The real threat to liberal learning is from an administrative class that is content to offer students far less than their own humanity calls for — and deserves.

The leadership of the University of Tulsa has for some years now despised its liberal-arts tradition and has intermittently tried to eradicate it. It looks like this time they will succeed.

The key point here — and it’s not the key point at Tulsa only — is that student interest, high enrollments, and donor support mean nothing to trustees and administrators and (often enough) faculty in other programs who have “succeeded” through a completely instrumental approach to education, employment, and indeed life itself. A thriving liberal-arts program is a standing reproach to their frivolity and greed, so they must eliminate it.

So far the administration of Baylor has been thoroughly supportive of our attempts, in the Honors College here, to do the kinds of things that Frey and her colleagues practiced at Tulsa. But what we do is so profoundly counter-cultural, in today’s flailing and failing American academy, that it’s hard not to peek over our shoulders from time to time to see if something is coming for us.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers