Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 7

June 27, 2025

Sayers and Constantine: 1

A theme that emerges strongly in Dorothy Sayers’s thought in the late 1930s — and continues to be central to her thought for the rest of her life — is expressed in a phrase that she uses repeatedly: “The dogma is is the drama.” Here is one articulation of that idea:

Let us, in Heaven’s name, drag out the Divine Drama from under the dreadful accumulation of slip-shod thinking and trashy sentiment heaped upon it, and set it on an open stage to startle the world into some sort of vigorous reaction. If the pious are the first to be shocked, so much the worse for the pious — others will pass into the Kingdom of Heaven before them. If all men are offended because of Christ, let them be offended; but where is the sense of their being offended at something that is not Christ and is nothing like Him? We do Him singularly little honour by watering down His personality till it could not offend a fly. Surely it is not the business of the Church to adapt Christ to men, but to adapt men to Christ.

It is the dogma that is the drama — not beautiful phrases, nor comforting sentiments, nor vague aspirations to loving-kindness and uplift, nor the promise of something nice after death — but the terrifying assertion that the same God Who made the world lived in the world and passed through the grave and gate of death. Show that to the heathen, and they may not believe it; but at least they may realise that here is something that a man might be glad to believe.

What’s especially interesting about this idea, for the biographer of Sayers, is that she seems to have discovered Dogma and Drama at the same time. That is, she started writing and speaking publicly about the Christian faith just as she began a new career as a playwright. Dogma and Drama provided an alternative to a path she had (though she did not admit it for a long time) written her way to the end of, that of the detective novelist.

Now, her first religious play, The Zeal of Thy House, is not fully committed to the dramatization of dogma. The play is more fundamentally concerned with the redemption of William of Sens. It describes how, after an accident that renders him paraplegic, an arrogant artistic dictator who thinks of the cathedral of Canterbury as his own creation becomes a more humble workman, aware both of his need for others to bring his ideas to life and also his subservience to God. That is to say, the play essentially concerns a man coming slowly to see that the human maker is what Tolkien called a sub-creator. (Neither Sayers nor Tolkien knew it, but they had virtually the same theology of work and articulated it very effectively, Sayers primarily in this play and and Tolkien primarily in the story of Fëanor in the Silmarillion and in the essay “On Fairy Stories.” I have sometimes wondered whether Tolkien read The Zeal of Thy House and was influenced by it, though I doubt it. Anyway, if he had, he’d never have admitted it.)

So The Zeal of Thy House doesn’t really test the proposition that “the dogma is the drama,” nor does her series of plays on the Life of Christ, The Man Born to Be King, because there the dramatic interest arises from events: this man’s teaching, suffering, death, and resurrection. There are of course dogmatic implications to this story, and Sayers embraces them … but that’s not the same thing as the dogma itself being the source of dramatic interest.

So did she ever put her idea to a practical test? Yes, she did, a decade after The Man Born to Be King, in a play that she wrote for the Colchester Festival in 1951. This task was a distraction from her chief work at the time, translating Dante, but perhaps a welcome one. Colchester is only fifteen miles from her home in Witham, which made it possible for her to be fully involved with the performance of the play — costumes and staging and rehearsals were her great delight — without demanding too much travel, which as she aged was becoming more difficult for her. She was a gregarious person, and at that time was lonely — her husband Mac Fleming had died in 1950. And perhaps above all, the play gave her a chance to test her great thesis: she decided to write a play called The Emperor Constantine, and to place at the center of her play the debates at the First Council of Nicaea.

And since this year marks the 1700th anniversary of that Council, this might be a good time to talk about Sayers’s play. I’ll be doing that over the next week or two. Or three. Stay tuned! The dogma really is the drama!

June 23, 2025

the health of the state

Decriminalising full term abortion signals a profound moral bankruptcy in England’s leadership class, made all the more grotesque by the thin and (I suspect) bad-faith arguments about compassion to “desperate women” under which this measure has travelled. The same goes for legalising the killing of our old and terminally ill, in a bill that rejected any duty to improve palliative care provision or even give regard to ensuring no one is coerced. This reveals the truth, that the animating desire for these policies of death was never compassion. It was always the political imposition on us all of radical alone-ness: complete liberation for each individual, from the givens of embodiment and our relatedness to one another.

We cannot, in this vision, be fully free until every vestige of human nature and purpose has been scrubbed away by the solvent power of technology and the all-powerful state, leaving only contingent causality and the brute stuff of our flesh.

Randolph Bourne, famously, wrote that “war is the health of the state.” We’re seeing that these days too. The more general truth is: Death is the health of the state. The state magnifies and extends its power through killing — through all the ways of killing. When we empower the state with the idea that it will act to save lives, we are more fundamentally authorizing it to end other lives (or maybe, eventually, the ones it saves). That’s just how it works.

Proudhon, in the middle of the nineteenth century, asserted that liberty is “not the daughter but the mother of order,” and that “society seeks order in anarchy.” Anarchists do not reject order or rule or governance but insist that in a healthy society these things cannot be imposed from above — from some arche, some authoritative source. Rather they emerge from negotiations between social equals. When complex phenomena arise from simple rules distributed throughout a large population — as can be seen best in social insects and slime molds — modern humans tend to be puzzled. For a long time scientists thought that there had to be intelligent queens in bee colonies giving directions to the other bees, because how else could the behavior within colonies be explained? The idea that the complexity simply emerges from the rigorous application of a handful of simple behavioral rules is hard for us to grasp. Bees and ants demonstrate how anarchy is order. It’s a shame that Proudhon did not know this.

Anarchy is thus the fons et origo of healthy order, and I am increasingly coming to believe that anarchy is the precondition of conservation. Anarchism (in this sense, the sense of order emerging from the voluntary collaborations of social equals) is the true conservatism.

States sometimes do good things, but we can trust the state only to enable killing and to kill. Anything better than killing can reliably be achieved only by civil society, and civil society will thrive only insofar as we practice voluntary collaboration — and it requires practice: voluntary collaboration is something the state has taught us to be bad at.

getting through

How to read and why – by James Marriott:

I generally get through one or two books a week in my leisure time. Plus I’m constantly skimming bits of others in the library for work.

The phrase “get through” is a red flag for me. Books are not to be gotten through, they are to be savored and reflected upon, or delighted in. As I have been saying for a very long time, people tend to assume that “being a better reader” primarily means “reading more books,” but this is incorrect.

There are many valid reasons to read, but if you’re about self-improvement in one way or another — an increase in knowledge or insight or, hey, even wisdom — then one of the most reliable ways to become a better reader is to read fewer books but read them with greater care. If you would be wise, an essential book you know intimately — through slow reading or repeated reading — is of more use to you than a dozen lesser books that you know only casually.

But when you’re reading for fun, don’t worry about “getting more from a book.” Just do whatever you most enjoy. If you finish a fun book and want immediately to start it over, do it. Knock yourself out! But, speaking generally, one of my few firm suggestions for readers would be: Only read a book that’s new to you if you’re not itching to re-read a much-loved one.

June 18, 2025

cheese

I adored Walter Martin’s episode on Cheesy Music and Guilty Pleasures, but my mind organizes these things differently than his mind does. (By the way, if you don’t listen to the Walter Martin Radio Hour you are seriously missing out.) Some of the music he calls cheesy I think of as overly earnest or emotionally indulgent or saccharine — but not necessarily cheesy. To borrow a phrase from the philosopher Bernard Williams, I think Walter suffers from a poverty of concepts.

For me, cheesiness is largely a sonic property: it’s a function of how a song is arranged and performed. So I think Walter is totally right to say that Elton’s “Daniel” and Springsteen’s “Secret Garden” are cheesy, because of the flutes + a chorusy electric piano in the former and the pulsing synths in the latter. But U2’s “With or Without You” isn’t cheesy! Good heavens, no. I mean, I think it’s a great song, and I don’t cringe at it one bit, but I get why Walter cringes at it a little: because of its intense earnestness and lyrical excess. But a song with a drum track that great can’t be cheesy.

Walter starts his show with “The Long and Winding Road,” which I think is probably saccharine in any arrangement but only cheesy when Phil Spector adds the strings. The strings on “Let It Be” are also cheesy, but without the strings it’s simply one of the greatest of pop sings.

Cheesiness for me is a function of vocal bad taste or (this is more common) instrumental excess: it’s a matter of gilding the lily, of pouring sugar on the ice cream. Once I listened to a recording of Aaron Copland rehearsing an orchestra for a performance of “Appalachian Spring,” and he told his string players to play dryly, not sweetly, because the music is already sweet enough. If he had let them lean into the vibrato and sweep, he’d have had a cheesy performance of his work.

I think maybe this is one reason why I like demos so much: no added cheese. An overly earnest or emotionally indulgent song can be great if the arrangement is suitably restrained. Dylan’s Blood in the Tracks is in many respects an emotionally excessive record, but the simplicity of the arrangements helps to make it not cringey but overwhelmingly powerful.

Even “Secret Garden” could, I think, be relatively cheese-free with a different arrangement. Springsteen’s love affair with synths in the Nineties was really a self-betrayal. Consider “Streets of Philadelphia,” an extremely earnest synth-heavy song. Listen to that original, and now listen to Waxahatchee’s cover of it: all she has to do is replace the synth with a Hammond organ and everything changes. Katie kills that vocal, also. That song did nothing for me until I heard her perform it.

Another example: Walter is right that “Downtown Train” is a weirdly cheesy song, given that it’s by Tom Waits — but that’s largely because it’s produced and arranged to sound like, I don’t know, maybe a Tom Petty song? Listen to this live version — a totally different beast. In fact, Waits specializes in songs that might well feel cheesy — or at best sentimental and overly earnest — if they were sung by someone with a normal voice in a normal pop arrangement. But when Tom sings “Take It With Me” it’s completely convincing, and deeply affecting. (By the way, the best commentary on Waits that I’ve ever read comes from Thom Yorke — scroll about 60% of the way down this page.)

And sometimes what you expect to be cheesy turns out not to be: see k. d. lang’s early album Shadowland for an example. This is an exercise in pure pastiche, as lang recreates the sound of Patsy Cline, using the Nashville String Machine and the Jordanaires, the whole apparatus. But it’s perfect: the arrangements suit the songs and the vocal performance right down to the ground. Buckle up your seat belt and listen to “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So” if you want to know what I mean. Of course, lang is pretty much the finest singer in the world — there are great singers who don’t have great voices, and great voices belonging to people who don’t really know how to sing: lang has the best instrument and the best taste — but the arrangement is perfection. As I say: it ought to be cheesy but isn’t.

And when you’re done with that one, have some “Black Coffee.”

I should make my own playlists — subscribers to Walter’s Substack get playlists associated with his episodes — of songs that I think of as fitting these different categories. If I find time to do that I’ll post links on my micro.blog.

June 17, 2025

the composer as ASS and other exasperations

In May of 1942, as Sayers was writing the eleventh play in the sequence called The Man Born to be King, she shot a quick letter to her producer, Val Gielgud:

As proof that I am doing something, and because it is urgent, I am sending you Mary Magdalen’s song to be set. You remember where it comes — the Soldiers will not let her and her party through to the foot of the Cross unless she sings to them — “Give us one of the old songs, Mary!”

The song is thus the, so to speak, “Tipperary” of the period, and must be treated as such. That is to say, the solo portion is nostalgic and sentimental, and the chorus is nostalgic and noisy; and the whole thing has to be such as one can march to. We want a simple ballad tune, without any pedantry about Lydian modes or Oriental atmosphere….

I want a tune that is both obvious and haunting — the kind that when you first hear it you go away humming and can’t get out of your head! And quite, quite, low-brow.

In September, when the company were rehearsing the play, DLS wrote to a friend,

We had an awful time with rehearsals. Everything seemed to go wrong — it was one of those days. Claudia’s Dream had been done badly (owing to my not being there to explain just what I wanted!) and the ASS who set the song disregarded all my instructions, and not only set it in ¾ time instead of march time, but had the vile impertinence to alter my lines because they wouldn’t fit his tune. I threw my one and only fit of temperament, and we sang the thing in march-time and restored the line, but it wasn’t a good tune anyway!

In another letter she wrote, “I’m still furious with the man who wrote that silly tune.” Who was this “ASS”? His name was … Benjamin Britten. Probably never made much of himself.

It’s fun to write about DLS in part because she is very entertaining when she is outraged by something. Some years after this incident she reluctantly gave an interview to a reporter from the News Chronicle, who then announced to the world that Sayers had declared that there would be no more Lord Peter Wimsey stories. Sayers to the paper’s editor:

Your interviewer appears to have misunderstood me. I did not say that I had given up writing detective stories. I did not say that there would be no more Peter Wimseys. I made no announcement on the subject one way or the other. I only said that for the next few years, I had another job which would take me all my time.

(The “another job” was translating the Divine Comedy.) The editor’s reply merely created further exasperation:

There is no need to wonder how your reporter came to misinterpret me. Your own letter provides the explanation, since it shows you to have fallen into a similar misunderstanding, and for the same reason; namely, that Fleet Street renders a man incapable of taking in the plain meaning of an English sentence. You say you are “glad to hear that there will, in fact, be further Wimsey stories”; how, pray, do you contrive to extract that conclusion from my statement that “I made no announcement upon the subject one way or the other”?

I have not said, and I will not and cannot say, whether I shall write any more detective fiction or not; for the excellent reason that I do not know. Is that sufficiently clear?

Three times your reporter tried to force me into promising that I would write more of this kind of story; three times I refused to commit myself to any such thing. This refusal he interpreted to suit his own fancy; you in your turn have done the same.

June 16, 2025

mind donation

Everyone Is Using A.I. for Everything. Is That Bad? – The New York Times:

ROOSE And then, of course, there’s the hallucination problem: These systems are not always factual, and they do get things wrong. But I confess that I am not as worried about hallucinations as a lot of people — and, in fact, I think they are basically a skill issue that can be overcome by spending more time with the models. Especially if you use A.I. for work, I think part of your job is developing an intuition about where these tools are useful and not treating them as infallible. If you’re the first lawyer who cites a nonexistent case because of ChatGPT, that’s on ChatGPT. If you’re the 100th, that’s on you.

NEWTON Right. I mentioned that one way I use large language models is for fact-checking. I’ll write a column and put it into an L.L.M., and I’ll ask it to check it for spelling, grammatical and factual errors. Sometimes a chatbot will tell me, “You keep describing ‘President Trump,’ but as of my knowledge cutoff, Joe Biden is the president.” But then it will also find an actual factual error I missed.

But how do you know the “factual error” it found is an actual factual error, not the kind of hallucination that Kevin Roose says he’s not worried about? Newton a little later in the conversation:

How many times as a journalist have I been reading a 200-page court ruling, and I want to know where in this ruling does the judge mention this particular piece of evidence? L.L.M.s are really good at that. They will find the thing, but then you go verify it with your own eyes.

First of all, I’m thinking: Hasn’t command-F already solved that problem? Does Newton not know that trick? Presumably he does, unless he’s reading the entire “200-page court ruling” to “verify with [his] own eyes” what the chatbot told him. So:

Casey Newton’s old workflow: Command-f to search for references in a text to a particular piece of evidence.

Casey Newton’s new AI-enhanced workflow: Ask a chatbot whether a text refers to a particular piece of evidence. Then use command-f to see if what the chatbot told him is actually true.

Now that’s what I call progress!

The NYT puts that conversation on its front page next to this story:

But as almost everyone who has ever used a chatbot knows, the bots’ “ability to read and summarize text” is horribly flawed. Every bot I have used absolutely sucks at summarizing text: they all get some things right and some things catastrophically wrong, in response to almost any prompt. So until the bots get better at this, then machine learning “will change the stories we tell about the past” by making shit up.

“Brain donor” is a cheap insult, but I feel like we’re seeing mind donation in real time here. Does Newton really fact-check the instrument he uses to check his facts? This is the same guy who also notes: “Dario Amodei, the chief executive of Anthropic, said recently that he believes chatbots now hallucinate less than humans do.” Newton doesn’t say he believes Amodei — “I would like to see the data,” he says, as if there could be genuine “data” on that question — but to treat a salesman’s sales pitch for his own product as a point to be considered on an empirical question is a really bad sign.

I won’t be reading anything Newton writes from this point on — because why would I? He doesn’t even think he has anything to offer — but I bet (a) in the next few months he’ll get really badly burned by trusting chatbot hallucinations and (b) that won’t change the way he uses them. He’s donated his mind and I doubt he’ll ask for it to be returned.

June 14, 2025

Buckley

I’ve just finished Sam Tanenhaus’s Buckley, which is magisterial. I have many, many thoughts, only a few of which I’ll share here.

Buckley’s greatest virtue and greatest vice was loyalty. Again and again we see him behaving with exceptional generosity to friends and family, even when that generosity was costly to him in dollars, in reputation, or in both. Once he came to think of someone as belonging in some way, in any way, to “us,” then it was almost impossible to dislodge his loyalty to them — even when they had, by any serious measure, betrayed that loyalty. Having settled on anything — a spouse, a friend, a house, a belief, a political stance — he couldn’t face abandoning him or her or it.

Buckley begins his book In Search of Anti-Semitism by frankly acknowledging that his own father was an antisemite, though he doesn’t go into any detail. (Tanenhaus does, though, and it’s not pretty.) But immediately after acknowledging his father’s views, he goes on to say that “the bias never engaged the enthusiastic attention of any of my father’s ten children…, except in the attenuated sense that we felt instinctive loyalty to any of Father’s opinions, whether about Jews or about tariffs or about Pancho Villa.” Okay … but what is that “attenuated sense”? The passage goes on without a break, as though to explain:

Seven or eight children in Sharon, Connecticut, among them four of my brothers and sisters, thought it would be a great lark one night in 1937 to burn a cross outside a Jewish resort nearby. That story has been told, and my biographer (John Judis) points out that I was not among that wretched little band. He fails to point out that I wept tears of frustration at being forbidden by senior siblings to go out on that adventure, on the grounds that (at age 11) I was considered too young. Suffice it to say that children as old as 15 or 16 who wouldn’t intentionally threaten anyone could, in 1937, do that kind of thing lightheartedly. Thoughtless, yes, but motivated only by the desire to have the fun of scaring adults! It was the kind of thing we didn’t distinguish from a Halloween prank. None of us gave any thought to Kristallnacht, even when it happened (November 9, 1938 — I was 12, in a boarding school in England), and certainly not to its implications. But then this is a legitimate grievance of the Jew: Kristallnacht was not held up in the critical media as an international event of the first magnitude, comparable to the initial (1948) laws heralding the formal beginning of apartheid or the triggering episodes of the religious wars of the seventeenth century.

The is strangely evasive, except in one respect: Buckley bluntly refuses to distinguish himself from his siblings simply because they burned the cross and he didn’t. Loyalty! If they are to be condemned, then he will share in their condemnation!

But should they be condemned? Should they have known that this was something rather more serious than “a Halloween prank”? Does he expect us to believe that the cross-burning just happened to have been done on a site belonging to Jews and that any other place favored by “adults” would have done just as well? (If not, why does he bring in the “scaring adults” line at all? And why does he include it in a paragraph about the relationship between his father’s antisemitism and the beliefs of his children?)

Does he now, at the time of writing, think it something that should have been seen as a serious offense? Or, rather, that no one could have been expected to take it seriously in 1937 but should have done so after Kristallnacht? Or even that it wouldn’t have been seen as serious in 1938 but on that point Jews have a “legitimate grievance”?

Who can say?

But note that every possibility listed reminds us that Buckley is only seeing this from the perspective of the people who had their “lark,” not the Jews who looked out their hotel window to find a cross burning on the lawn. For them he does not spare a thought. (Something similar occurs in his discussion of Joseph Sobran, a blatant Jew-hater whom Buckley allowed for a long time to write for National Review and dismissed only under significant pressure: when Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary, protested Sobran’s writings Buckley replied that “you are strangely insensitive to the point that his essay is much more damaging to me than it is to you.” I’m the real victim here!)

Similarly: he knew what Joe McCarthy was, knew what terrible sins and crimes he committed, and he was too honest to deny those sins and crimes; but out of loyalty he minimized them and said — well, what he always said from the beginning of his career to the end: The other side is worse and therefore hypocritical. “They” are worse than “we.” The people unjustly smeared by McCarthy simply don’t show up on Buckley’s radar at all.

He took the same approach to Southern racists who thought of themselves are preserving Southern traditions — people like his parents, to whom of course he was loyal. (His father was a Texan and his mother from New Orleans, and they split their time between a home in Connecticut and one in South Carolina. Buckley grew up in both worlds.) In 1959 he wrote a column for National Review that astounds me:

In the South, the white community is entitled to put forward a claim to prevail because, for the time being anyway, the leaders of American civilization are white — as one would certainly expect given their preternatural advantages, of tradition, training, and economic status. It is unpleasant to adduce statistics evidencing the median cultural advantage of white over Negro; but the statistics are there, and are not easily challenged by those who associate together and call for the Advancement of Colored People. There are no scientific grounds for assuming congenital Negro disabilities. The problem is not biological, but cultural and educational. The question the white community faces, then, is whether the claims of civilization (and of culture, community, regime) supersede universal suffrage.

He answers Yes: indeed, “the claims of civilization” justify denying black people the vote. That’s not the astonishing part, though: what strikes me is Buckley’s quite explicit denial of the central claim of the Southern segregationists, which is that blacks are intrinsically and necessarily inferior to whites. Nonsense, Buckley says: “There are no scientific grounds for assuming congenital Negro disabilities.” White culture is superior to black culture because of the “preternatural advantages” granted by “tradition, training, and economic status.” But because it is superior, it should be allowed to rule. Which is no different than saying that a man who steals all my money should be allowed to keep it because he’s richer than I am. The plain old racists have at least the merit of consistency.

In 2004 Buckley told an interviewer: “I once believed we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow. I was wrong: federal intervention was necessary.” A pundit admitting error is a remarkable thing, seen but a few times a century. That is admirable. But I do wonder how he could ever have believed, even in 1959, that people whose entire lives were built on the conviction of white supremacy would somehow “evolve” into something different? I doubt that he ever did believe it, though he may have wished for it. Primarily what he was doing in that column was being loyal to his parents and to their social world.

All that duly noted, I came away from this biography admiring Buckley for some things, and maybe most of all for his commitment to debate, especially on his TV show Firing Line. The very first episode of that show featured the socialist Michael Harrington, and at the end of it Buckley commended Harrington for making the most eloquent defense of President Johnson’s anti-poverty programs that he had ever heard.

And as Tanenhaus notes, Firing Line became the place to go if you wanted to hear what the radical black activists of the Sixties and Seventies — Huey Newton! Eldridge Cleaver! Roy Innis! — actually thought:

Buckley interviewed these activists, and opened his microphones to them, at a time when their exposure on mainstream television was limited to footage of violent demonstrations. “Amazingly,” writes the media historian Heather Hendershot, “a PBS public affairs program designed to convert Americans to conservatism [broadcast] some of the most comprehensive representations of Black Power from [its] era outside of the underground press and other alternative sources.”

(Link added.) That’s pretty cool.

I have a great deal to think through after reading this remarkable book. There may be more thoughts later — I feel that I ought to say more about what Buckley got right, because there were a few things. But for now I’m out of time.

June 12, 2025

two quotations on doing what I hate

If I added up all the hours I spent on a screen,

existential dread and regret would creep in. So I ignore this fact by opening my phone.

And it’s not like I can throw it away.

It’s how we communicate. It’s how we relate.

It’s a medicine that is surely making our souls die.

I used to say I was born in the wrong generation, but I was mistaken.

For I do everything I say I hate. Exchanging hobbies for Hinge,

truth with TikTok, intimacy with Instagram, sanity with Snapchat.

I have become self-aware. Almost worse than being naive. I know it’s poison, but I drink away.

The character behind the phone screen has become self-aware.

The apostle Paul:

I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. But in fact it is no longer I who do it but sin that dwells within me. For I know that the good does not dwell within me, that is, in my flesh. For the desire to do the good lies close at hand, but not the ability. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it but sin that dwells within me.

deskilling and demos

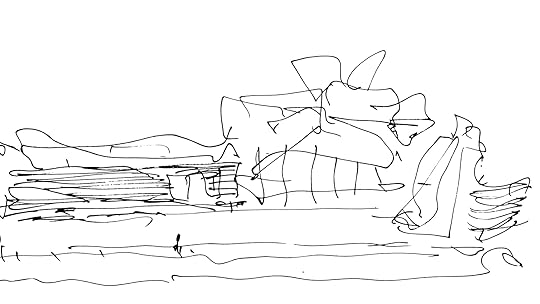

Here’s an architectural drawing by Frank Lloyd Wright:

And here’s one by Frank Gehry:

Now, Gehry’s sketches are quite interesting, I think. My point is not that they’re worse than Wright’s, but that they are radically different and serve a different purpose. Gehry wasn’t going to spend a lot of time working out the details of a building — its structure or its appearance — because that’s what CAD (Computer Assisted Design) software is for. Before CAD came around, Gehry drew like this:

He would’ve had to learn to draw that way when at school. I wonder how much of that skill he retained … or maybe I should say, how long he retained it?

Architects have been debating the importance of drawing for several decades now. There was a bit of a kerfuffle in the business a decade ago when an architecture student said that he had been taught to draw, and acknowledged that “most people” he had asked thought it valuable, but did not seem to think that the skill had any real use. Indeed, he felt that drawing was a time-consuming distraction from what he thought his real job: “generating concepts.”

Me, I’m more interested in those who make art than those who generate concepts. But to each his own.

And I’m not just interested in works of art, I’m interested — passionately interested — in works of art that lead to other works of art. I love architectural drawings like Wright’s. I love the magnificent cartoons by Leonardo and Raphael. I prefer Constable’s sketches to his oil paintings.

And maybe above all I love musical demos.

The Beatles’ Esher demos mean more to me than the White Album. The gorgeous productions of Joni Mitchell’s Asylum albums just might be transcended, but in any case are put in their proper context, by her voice-and-guitar demos — and just listen to “Coyote” when she was still working it out. The best music Paul McCartney did in his post-Beatles career was his brief partnership with Elvis Costello, and their demo of “My Brave Face” is magnificent — far better than the more polished version that was eventually released. Bob Dylan’s “Mississippi” (from Love and Theft) is a fine song, but the earlier, simpler, demo-like version is truly great.

What I’m loving here — of course! — is human effort, human exploration, figuring it out, trial and error, rough edges, things in progress: the rough ground. I’m basically repeating here the message of Nick Carr’s book The Glass Cage, and much of Matt Crawford’s work, and more than a few of my earlier essays, but: automation deskills. Art that hasn’t been taken through the long slow process of developmental demonstration — art that has shied from resistance and pursued “the smooth things” — will suffer, will settle for the predictable and palatable, will be boring. And the exercise of hard-won human skills is a good thing in itself, regardless of what “product” it leads to. But you all know that. Demos and sketches and architectural drawings are cool, is what I’m saying.

June 11, 2025

two quotations on the humanism of leftovers

Remainder humanism is the term I use for us painting ourselves into a corner theoretically. The operation is just that we say, “machines can do x, but we can do it better or more truly.” This sets up a kind of John-Henry-versus-machine competition that guides the analysis. With ChatGPT’s release, that kind of lazy thinking, which had prevailed since the early days of AI critique, especially as motivated by the influential phenomenological work of Hubert Dreyfus, hit a dead end. If machines can produce smooth, fluent, and chatty language, it causes everyone with a stake in linguistic humanism to freak out. Bender retreats into the position that the essence of language is “speaker’s intent”; Chomsky claims that language is actually cognition, not words (he’s been doing this since 1957; his NYT op-ed from early 2023 uses examples from Syntactic Structures without adjustment).

But the other side are also remainder humanists. These are the boosters, the doomers, as well as the real hype people — and these amount to various brands of “rationalism,” as the internet movement around Eliezer Yudkowsky is unfortunately known. They basically accept the premise that machines are better than humans at everything, but then they ask, “What shall we do with our tiny patch of remaining earth, our little corner where we dominate?” They try to figure out how we can survive an event that is not occurring: the emergence of superintelligence. Their thinking aims to solve a very weak science fiction scenario justified by utterly incorrect mathematics. This is what causes them to devalue current human life, as has been widely commented.

I doubt I will be safe for much longer. I can easily find myself in a position like that of the theologian who worships — this is a famous phrase from one of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s prison letters — “the God of the gaps,” a deity who only has a place where our knowledge fails, and whose relevance therefore grows less and less as human knowledge increases. If I can only pursue a “pedagogy of the gaps,” assignments that happen to coincide with the current limitations of the chatbots, then what has become of me as a teacher, and of my classroom as a place of learning? At least I can still assign my explications — a pathetic kind of gratitude, that.

No; there’s no refuge there. I must then begin with the confident expectation that chatbots will be able to do any assignment that they are confronted with. What follows from that expectation?

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers