my anarchist notebook

I mentioned in a recent post that reading Thomas Flanagan’s novels about Ireland has me thinking about revolution – the causes and consequences of revolution, and of course the difficulty of defining “revolution.” Often it is defined quite narrowly as “an attempt to overthrow an existing government by force of arms” and equally often quite expansively as “advocacy for major social change.” In my recent thinking Michael Collins has played a large role, because while there can be no doubt that Collins wanted the British out of Ireland altogether, he became convinced that the best way to do this was to move one step at a time, to accept Dominion status as a way-station to complete independence. This made him, I think, a kind of gradualist revolutionary, though to his Irish opponents it made him into something altogether unrevolutionary, which is why they killed him. (For urgent Irish revolutionaries, the advocacy of anything other than immediate violence made you a “West Briton,” as Gabriel Conroy is called by Miss Ivors in Joyce’s story “The Dead.”)

My interest in anarchism complicates my thinking about these matters. On the one hand, an anarchist society would be radically different than the one we now live in, and in that sense would be the fruit of a revolution. But organized armed revolution could not, in my view, be pursued anarchically – it would be anti-anarchist even if conducted in the name of anarchy. That was also true of the “anarchist” bombers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: they were not anarchists, for as Proudhon said, “Anarchy is order”; rather, they were Chaotics, a very different thing. To render a social order non-functional in the hope that something more just will somehow rise from the ruins is antithetical to the character of anarchism, which is all about collaboration and cooperation. Terrorism and armed insurrection are thus equally alien to true anarchism.

So how could anarchism be practiced in such a way that society changes for the better? How is it possible to remake the world without betraying your principles in the process? (“We had to destroy the village in order to save it.”)

I’ve written off and on about these matters for years – see the “anarchism” tag at the bottom of this post – but my thoughts are still largely confused. So I decided to make this post a kind of notebook of ideas. I’ll post today but then I will come back and add second and third thoughts later, and see if some kind of order eventually emerges. After all, isn’t anarchic method appropriate to the study of anarchism?

If you haven’t read anything I’ve written about this, start with this essay and then this reflection on Christian anarchy.

One more thing: my major guides to thinking about anarchism are

Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism James Scott, Two Cheers for Anarchism David Graeber, essaysAnd now on to the notebook:

Malatesta thought that the committed libertarian, who cares only about his own freedom of movement, will if he follows his natural course become a tyrant, and in even the best case “anything but an anarchist.”

•

It is vitally important to distinguish anarchism from libertarianism. The highest goods of the libertarian are freedom of action and freedom to own property, both conceived as belonging to the individual. The anarchist, by contrast, seeks some form of the good life in collaboration and cooperation with others. Anarchism is therefore intrinsically social, pluralistic, and unplanned. Because, as Isaiah Berlin says, the Great Goods are not always compatible with one another, you collaborate with people who share your priorities, understanding and accepting that others will find other structures of collaboration. And in pursuing those goods you have the humility to recognize that you don’t know how they may be achieved; that is something you discover through your collaboration. (Related by me: this and this.)

Anarchism is therefore not a system of government but a practice, and one can practice it at any level of social interaction. The parent who tells two squabbling children to work out their differences themselves, rather than appealing to a parental verdict, is practicing anarchism, and a very important form of it too.

•

The true anarchist can never throw bombs, because when you do that you are making decisions for other people without their consent, which is anthithetical to anarchism.

•

Anarchism can never be revolutionary in the sense in which political systems (communism, socialism, fascism) can be revolutionary. But the ultimate effects of anarchism can be far greater than the effects of any of those other movements. As Hannah Arendt said, every revolutionary becomes a conservative the day after the revolution; as The Who said, “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” Anarchism declines bosses altogether. And that is truly revolutionary – but it is only brought about by means so slow and patient that no one can see them at work.

•

It is a shame that, in The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin never describes in detail the revolution that led to the anarchist colony on Anarres. We only learn, in a wonderful story, about “The Day Before the Revolution.” So the question of how principled anarchists revolt is left unanswered.

•

James Scott speaks of “the anarchist tolerance for confusion and improvisation that accompanies social learning, and confidence in spontaneous cooperation and reciprocity.” The key point here is that link between improvisation and “social learning.” An algorithmic order is incompatible with both improvisation and social learning.

Scott again: in the last hundred years we have learned that “material plenty, far from banishing politics, creates new sphere of political struggle” and also that “statist socialism was less ‘the administration of things’ than the trade union of the ruling class protecting its privileges.”

•

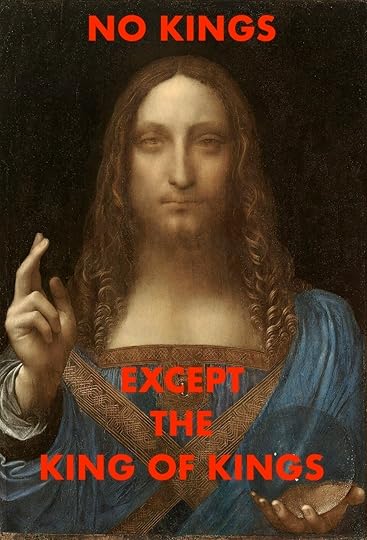

Jacques Ellul thinks that Christians should be anarchists because God, in Jesus Christ, has renounced Lordship. I think something almost the opposite: it is because Jesus is Lord (and every knee shall ultimately bow before him, and every tongue confess his Lordship) that Christians should be anarchists.

To be continued…

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers