Chris Eboch's Blog, page 30

July 25, 2012

When Rules Aren’t: namelos author Alina Klein

Alina Klein provides the final installment for the series of guest posts by namelos authors. She shares some advice about when to listen to advice – and when to go your own way – with “When Rules Aren’t.” Here's Alina:

I was at a writing conference several months ago listening to a well-published author share her rules about writing a novel. It was an entertaining speech. She was smart, funny and confident in what she was saying. She shared her rules with great conviction and everyone around me was scribbling notes, madly.

One of them was: Never write a book about something bad that happened in your past. Nobody wants to read that.

Scribble, scribble went the pens.

There was a point in my life that hearing that “rule” from the mouth of a popular author would have derailed me. The novel I worked on for many years was based on something bad that happened to me in my own past. Who was I to think I could do it successfully?

Of course, that wasn’t the first rule I heard at a conference, or read in a book, that made me question my story and whether I should continue with it. There have been many.

Luckily my memory is pretty poor. I’d forget derailing advice after a few days, weeks or sometimes months, and then I’d get back to work on my book.

The bottom line is, I had to write Don’t put your faith in anyone but yourself when it comes to what you should or shouldn’t write, or how to go about it. The rules we pick up from successful authors and industry professionals are there to guide us when we are lost, not derail us when we have some inkling of where we’re going. Pick and choose what inspires you, ignore the rest, and write whatever you must.

Alina Klein lives in Indiana with her husband, two sons, and a quirky assortment of pets, including both a tortoise and a hare. When she isn’t reading or writing you might find her foraging for wild edibles, hauling random materials around her yard to create pretty things for her garden, or snapping amusing photos of her children and guinea fowl. Alina volunteers as an Assistant Regional Adviser for The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Rape Girl is her first novel.

Alina Klein lives in Indiana with her husband, two sons, and a quirky assortment of pets, including both a tortoise and a hare. When she isn’t reading or writing you might find her foraging for wild edibles, hauling random materials around her yard to create pretty things for her garden, or snapping amusing photos of her children and guinea fowl. Alina volunteers as an Assistant Regional Adviser for The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Rape Girl is her first novel.

Published on July 25, 2012 04:00

July 20, 2012

Turning an Idea into Story: End with a Bang

Back in June I started talking about turning an idea into a story by breaking it down into four main parts: situation, complications, climax, and resolution. I covered setting up the situation and then had several posts on building a strong middle full of action and conflict (click on the blog title bar and then scroll down to see these posts, which alternate with guest posts from namelos authors). Now we get to the climax and resolution.

Can She Do It?!

Your character has faced complications through the middle of the story. Finally, at the climax, the main character must succeed or fail. Time is running out. The race is near the end. The girl is about to date another guy. The villain is starting the battle. One way or another, your complications have set up a situation where it’s now or never. However you get there, the climax will be strongest if it is truly the last chance. You lose tension if the reader believes the main character could fail this time, and simply try again tomorrow.

In my romantic suspense novel Whispers in the Dark, the climax comes when the heroine is injured and being pursued by a villain. If she can escape, maybe she can stop the bad guys and save her love interest. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all. Short stories, different genres, or novels for younger kids might have lesser stakes, but the situation should still be serious.

Tips:

• Don’t rush the climax. Take the time to write the scene out in vivid detail, even if the action is happening fast. Think of how movies switch to slow motion, or use multiple shots of the same explosion, in order to give maximum impact to the climax. Use multiple senses and your main character’s thoughts and feelings to pull every bit of emotion out of the scene.

• To make the climax feel fast-paced, use mainly short sentences and short paragraphs. The reader’s eyes move more quickly down the page, giving a sense of breathless speed. (This is a useful technique for cliffhanger chapter endings as well.)

Happy Endings

The climax ends with the resolution. You could say that the resolution finishes the climax, but it comes from the situation: it’s how the main character finally meets that original challenge.

In almost all cases the main character should resolve the situation himself. No cavalry to the rescue! Today, even romance novels rarely have the hero saving the heroine; she at least helps out (and may very well save him instead). We’ve been rooting for the main character to succeed, so if someone else steals the climax away from him or her, it robs the story of tension and feels unfair.

Here’s where many beginning children’s writers fail. It’s tempting to have an adult—a parent, grandparent, or teacher, or even a fairy, ghost, or other supernatural creature—step in to save the child or tell him what to do. But kids are inspired by reading about other children who tackle and resolve problems. It helps them believe that they can meet their challenges, too. When adults take over, it shows kids as powerless and dependent on grownups. So regardless of your character’s age, let your main character control the story all the way to the end (though others may assist).

Although your main character should be responsible for the resolution, she doesn’t necessarily have to succeed. She might, instead, realize that her goals have changed. The happy ending then comes from her new understanding of her real needs and wants. Some stories may even have an unhappy ending, where the main character’s failure acts as a warning to readers. This is more common in literary novels than in genre fiction.

Tip: How the main character resolves the situation—whether she succeeds or fails, and what rewards or punishments she receives—will determine the theme. To help focus your theme, ask yourself:

What am I trying to accomplish? Who am I trying to reach? Why am I writing this?

Once you know your theme, you know where the story is going and how it must be resolved. For example, a story with the theme “Love conquers all” would have a different resolution than a story with the theme “Love cannot always survive great hardship.”

The next time you have a great idea but can’t figure out what to do with it, see if you have all four parts of the story. If not, see if you can develop that idea into a complete, dramatic story or novel by expanding your idea, complications, climax or resolution, as needed. Then readers will be asking you, “Where did you get that fabulous idea?”

Chris writes for adults under the name Kris Bock. In Whispers in the Dark a young archaeologist stumbles into danger among ancient southwestern ruins.

a young archaeologist stumbles into danger among ancient southwestern ruins.

Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

Can She Do It?!

Your character has faced complications through the middle of the story. Finally, at the climax, the main character must succeed or fail. Time is running out. The race is near the end. The girl is about to date another guy. The villain is starting the battle. One way or another, your complications have set up a situation where it’s now or never. However you get there, the climax will be strongest if it is truly the last chance. You lose tension if the reader believes the main character could fail this time, and simply try again tomorrow.

In my romantic suspense novel Whispers in the Dark, the climax comes when the heroine is injured and being pursued by a villain. If she can escape, maybe she can stop the bad guys and save her love interest. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all. Short stories, different genres, or novels for younger kids might have lesser stakes, but the situation should still be serious.

Tips:

• Don’t rush the climax. Take the time to write the scene out in vivid detail, even if the action is happening fast. Think of how movies switch to slow motion, or use multiple shots of the same explosion, in order to give maximum impact to the climax. Use multiple senses and your main character’s thoughts and feelings to pull every bit of emotion out of the scene.

• To make the climax feel fast-paced, use mainly short sentences and short paragraphs. The reader’s eyes move more quickly down the page, giving a sense of breathless speed. (This is a useful technique for cliffhanger chapter endings as well.)

Happy Endings

The climax ends with the resolution. You could say that the resolution finishes the climax, but it comes from the situation: it’s how the main character finally meets that original challenge.

In almost all cases the main character should resolve the situation himself. No cavalry to the rescue! Today, even romance novels rarely have the hero saving the heroine; she at least helps out (and may very well save him instead). We’ve been rooting for the main character to succeed, so if someone else steals the climax away from him or her, it robs the story of tension and feels unfair.

Here’s where many beginning children’s writers fail. It’s tempting to have an adult—a parent, grandparent, or teacher, or even a fairy, ghost, or other supernatural creature—step in to save the child or tell him what to do. But kids are inspired by reading about other children who tackle and resolve problems. It helps them believe that they can meet their challenges, too. When adults take over, it shows kids as powerless and dependent on grownups. So regardless of your character’s age, let your main character control the story all the way to the end (though others may assist).

Although your main character should be responsible for the resolution, she doesn’t necessarily have to succeed. She might, instead, realize that her goals have changed. The happy ending then comes from her new understanding of her real needs and wants. Some stories may even have an unhappy ending, where the main character’s failure acts as a warning to readers. This is more common in literary novels than in genre fiction.

Tip: How the main character resolves the situation—whether she succeeds or fails, and what rewards or punishments she receives—will determine the theme. To help focus your theme, ask yourself:

What am I trying to accomplish? Who am I trying to reach? Why am I writing this?

Once you know your theme, you know where the story is going and how it must be resolved. For example, a story with the theme “Love conquers all” would have a different resolution than a story with the theme “Love cannot always survive great hardship.”

The next time you have a great idea but can’t figure out what to do with it, see if you have all four parts of the story. If not, see if you can develop that idea into a complete, dramatic story or novel by expanding your idea, complications, climax or resolution, as needed. Then readers will be asking you, “Where did you get that fabulous idea?”

Chris writes for adults under the name Kris Bock. In Whispers in the Dark

a young archaeologist stumbles into danger among ancient southwestern ruins.

a young archaeologist stumbles into danger among ancient southwestern ruins. Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

Published on July 20, 2012 04:00

July 13, 2012

Strong Writing: Raising the Stakes

In my Friday craft posts, I’ve been talking about plotting – how to develop an idea into a story and how to pack the plot full of action. Now let’s talk about the stakes – and how to raise them.

Look at your main story problem. What are the stakes? Do you have positive stakes (what the main character will get if he succeeds), negative stakes (what the MC will suffer if he fails), or both? Could the penalty for failure be worse? Your MC should not be able to walk away without penalty. Otherwise the problem was obviously not that important or difficult. The penalty can be anything from personal humiliation to losing the love interest to the destruction of the world – depending on the length of story and audience age – so long as you have set up how important that is for your MC.

Get great plotting tips in Advanced Plotting (links below)In recent weeks, I’ve talked more about adding complications. Note that those complications should also be both Difficult and Important. Say you have a character who needs to get somewhere by a specific time, and you want to increase tension by causing delays. If she simply runs into a series of chatty neighbors, it’s quickly going to get boring (unless you can push it to the point of comedy).

Get great plotting tips in Advanced Plotting (links below)In recent weeks, I’ve talked more about adding complications. Note that those complications should also be both Difficult and Important. Say you have a character who needs to get somewhere by a specific time, and you want to increase tension by causing delays. If she simply runs into a series of chatty neighbors, it’s quickly going to get boring (unless you can push it to the point of comedy).

Instead, find delays that are dramatic and important to the main character. Her dog slips out of the house while she’s distracted, and she’s worried that he’ll get hit by a car if she doesn’t get him back inside... Her best friend shows up and insists that they talk about something important NOW or she won’t be friends anymore....

Ideally, these complications also relate to the main problem or a subplot. The best friend’s delay will have more impact if it’s tied into a subplot involving tension between the two friends rather than coming out nowhere.

Here’s another important point -- you must keep raising the stakes, making each encounter different and more dramatic. You move the story forward by moving the main character farther back from her goal, according to Jack M. Bickham in his writing instruction book Scene and Structure –

–

“Well-planned scenes end with disasters that tighten the noose around the lead character’s neck; they make things worse, not better; they eliminate hoped-for avenues of progress; they increase the lead character’s worry, sense of possible failure, and desperation – so that in all these ways the main character in a novel of 400 pages will be in far worse shape by page 200 than he seemed to be at the outset.”

Are things worse at page 200?If the tension is always high, but at the same height, you still have a flat line. Instead, think of your plot as going in waves. Each scene is a mini-story, building to its own climax -- the peak of the wave. You may have a breather, a calmer moment, after that climax. But each scene should lead to the next, and drive the story forward, so all scenes connect and ultimately drive toward the final story climax.

Are things worse at page 200?If the tension is always high, but at the same height, you still have a flat line. Instead, think of your plot as going in waves. Each scene is a mini-story, building to its own climax -- the peak of the wave. You may have a breather, a calmer moment, after that climax. But each scene should lead to the next, and drive the story forward, so all scenes connect and ultimately drive toward the final story climax.

Example: In the Haunted books, the kids have a time limit for helping the ghosts, because their parents’ ghost hunter TV show is only shooting for a few days. But the stakes also rise as the kids get more involved with the ghosts, and understand their tragic plights. Complications come from human meddlers – the fake psychic who wants to take credit, the mean assistant who thinks kids are troublemakers, and Mom, who worries and wants to keep the kids away from anything dangerous.

Exercise: take one of your story ideas. Outline a plot that escalates the problem.

Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

Chris also writes romantic suspense for adults under the name Kris Bock. Visit her website or see Kris Bock’s books on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Smashwords.

Look at your main story problem. What are the stakes? Do you have positive stakes (what the main character will get if he succeeds), negative stakes (what the MC will suffer if he fails), or both? Could the penalty for failure be worse? Your MC should not be able to walk away without penalty. Otherwise the problem was obviously not that important or difficult. The penalty can be anything from personal humiliation to losing the love interest to the destruction of the world – depending on the length of story and audience age – so long as you have set up how important that is for your MC.

Get great plotting tips in Advanced Plotting (links below)In recent weeks, I’ve talked more about adding complications. Note that those complications should also be both Difficult and Important. Say you have a character who needs to get somewhere by a specific time, and you want to increase tension by causing delays. If she simply runs into a series of chatty neighbors, it’s quickly going to get boring (unless you can push it to the point of comedy).

Get great plotting tips in Advanced Plotting (links below)In recent weeks, I’ve talked more about adding complications. Note that those complications should also be both Difficult and Important. Say you have a character who needs to get somewhere by a specific time, and you want to increase tension by causing delays. If she simply runs into a series of chatty neighbors, it’s quickly going to get boring (unless you can push it to the point of comedy). Instead, find delays that are dramatic and important to the main character. Her dog slips out of the house while she’s distracted, and she’s worried that he’ll get hit by a car if she doesn’t get him back inside... Her best friend shows up and insists that they talk about something important NOW or she won’t be friends anymore....

Ideally, these complications also relate to the main problem or a subplot. The best friend’s delay will have more impact if it’s tied into a subplot involving tension between the two friends rather than coming out nowhere.

Here’s another important point -- you must keep raising the stakes, making each encounter different and more dramatic. You move the story forward by moving the main character farther back from her goal, according to Jack M. Bickham in his writing instruction book Scene and Structure

–

–“Well-planned scenes end with disasters that tighten the noose around the lead character’s neck; they make things worse, not better; they eliminate hoped-for avenues of progress; they increase the lead character’s worry, sense of possible failure, and desperation – so that in all these ways the main character in a novel of 400 pages will be in far worse shape by page 200 than he seemed to be at the outset.”

Are things worse at page 200?If the tension is always high, but at the same height, you still have a flat line. Instead, think of your plot as going in waves. Each scene is a mini-story, building to its own climax -- the peak of the wave. You may have a breather, a calmer moment, after that climax. But each scene should lead to the next, and drive the story forward, so all scenes connect and ultimately drive toward the final story climax.

Are things worse at page 200?If the tension is always high, but at the same height, you still have a flat line. Instead, think of your plot as going in waves. Each scene is a mini-story, building to its own climax -- the peak of the wave. You may have a breather, a calmer moment, after that climax. But each scene should lead to the next, and drive the story forward, so all scenes connect and ultimately drive toward the final story climax.Example: In the Haunted books, the kids have a time limit for helping the ghosts, because their parents’ ghost hunter TV show is only shooting for a few days. But the stakes also rise as the kids get more involved with the ghosts, and understand their tragic plights. Complications come from human meddlers – the fake psychic who wants to take credit, the mean assistant who thinks kids are troublemakers, and Mom, who worries and wants to keep the kids away from anything dangerous.

Exercise: take one of your story ideas. Outline a plot that escalates the problem.

Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.Chris also writes romantic suspense for adults under the name Kris Bock. Visit her website or see Kris Bock’s books on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Smashwords.

Published on July 13, 2012 04:00

July 11, 2012

5 Tips for Strong Settings from Sheila Kelly Welch

Here's another of my namelos guests. Sheila Kelly Welch, author of Waiting to Forget, shares five tips on bringing your setting to powerful life.

Where in the World?

Back when cell phones were just beginning to become common, our teenaged children would answer our house phone, and the first question they always asked their friends was, “Where you at?” Often this was followed by, “When you getting here?” We humans have an innate desire to ask and answer those two basic questions, “Where?” and “When?”

As authors, we need to give readers a feeling for the time and place of our stories. Chris already has written an informative blog post that gives an overview about settings, so I decided to narrow my focus to a few specific suggestions.

A sense of place is simply the background for stories such as Beverly Cleary’s Ramona series that are driven mainly by interplay between characters. In contrast, the setting is of upmost importance in stories like Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet with the wilderness playing as big a role as the character.

Each author determines how large a part a story’s time and place will play. In my own case, when I begin to form an idea, the setting almost always grows along with my concept of the characters. In addition, for most of my writing, “where” and sometimes “when” are crucial to the plot.

Although some young readers may love to read long, descriptive passages, many are bored and will skip over these sections or even be discouraged and toss the whole book, magazine, or e-reader aside. Here are my five tips for creating convincing settings that will keep kids reading.

1) Use vivid and, if possible, unique details that help set the tone of your story and make readers feel as if they are there with your characters.

2) Reveal information about the location of your story or scene gradually, not all at once.

3) Connect the description with an emotion or an emotional response on the part of the character(s). Whether the setting reflects or contrasts with the character’s mood doesn’t matter. The important thing is to relate the place to the character’s feelings.

4) Weave the description in and around dialog or action. This helps keep the scene from becoming static and helps readers build a complete mental image that includes the characters.

5) Use all five senses in your description. This is often neglected because authors “see” the location and tell only what it looks like. Adding the smells, tastes, sounds, and textures offers many opportunities to immerse your readers in your story’s setting.

My short story, “The Holding-On Night” published in Cricket, is about the 1918 pandemic, so what happens is tied to the time and place. Although I researched that time period, I was fortunate to have a first-hand account from my mother. She also told me many details about her childhood environment that helped me create the setting.

The story is only about six pages long but illustrates all five of my tips or suggestions. Below I’ve arranged most of the references to the setting as they appear in the story and have labeled and discussed the corresponding number of the tip(s) (see above). As you’ll discover, there is considerable overlap.

> Anna squinted up at the stern clouds in the October sky. A sharp breeze skimmed across the field, whispering a threat of winter through the dried grasses. She shivered.

#3, #5 This first paragraph reflects the sense of foreboding that the girl feels, before the terror of the illness is even mentioned. The sound of the wind is part of the scene.

> Anna’s older sister, Ellen, walked beside her on the narrow path. “It’s going to rain,” she said. “I can feel it.”

“Beeeeep!” yelled nine-year-old Peggie. She was trying--unsuccessfully--to imitate the blaring horns of the Model T Fords that sometimes chugged past their house.

#2, #4 Separated by even more dialog, these two portions show how bits and pieces of the setting are introduced gradually and are woven into the action and dialog.

> The path was for all the McNaughton school-age children. Their father had gotten permission from the farmer who owned the field and spent all of a weekend hacking through the weeds to create a shortcut to school.

#2, #3 Again, here’s a gradual introduction, but this time with an emotional connection. Readers are shown how much the children’s father cares for them.

> Ellen was insisting that Maria hold her hand, even though there were no wagons or noisy automobiles out and about with the deadly influenza stalking the country.

#1, #3 Here are details, unique to this setting, and Ellen’s concern for her younger sibling is demonstrated.

> She trudged across the dusty road and along the cracked sidewalk. Just as she started up the sagging wooden steps onto the front porch of their home, the door burst open. Peggie stomped out. “There’s no bread!”

#2 Here are action and dialog, along with description.

> Through the open door she could feel the heat of the kitchen and smell the slightly sickening odor of diapers boiling, being sterilized on the wood stove.

The house was too warm; their father had fed the potbellied stove so much wood, it glowed --- as if fire could drive away the flu like a wild beast.

#1, #5 Unique details are used plus the senses of touch and smell.

> Daddy had brought down several chamber pots and helped the little ones to use them. The stench was all around, and Anna lay, barely breathing.

#3, #5 Both father and daughter are connected to the setting, and, obviously, the sense of smell is used.

> The rocker moved gently back and forth. Her father’s heart thumped to the rhythm. Anna felt his arms, holding her, keeping her from sliding forever into the darkness.

Early in the morning, as the first light seeped into the kitchen, Anna climbed from her father’s arms.

#3, #5 These last two examples use touch, sound, and sight. Also, the light coming into the kitchen reflects the emotions of the child.

While creating a convincing setting can be a challenge, it is well worth the effort. If you use these five tips, you’ll help readers to feel a connection – not just to the setting you’ve described – but to your whole story.

Sheila Kelly Welch is a former teacher who writes and illustrates for children of all ages. Her story, “The Holding-On Night,” published in Cricket, won the International Reading Association’s 2007 Paul A. Witty Short Story Award. Her work has appeared in many children’s magazines, and she has written a collection of short stories, three easy-to-read chapter books, and five novels, including her most recent, Waiting to Forget, published by namelos. See both the text and illustrations for “The Holding-On Night.”

Watch a book trailer for Waiting to Forget.

Published on July 11, 2012 04:00

July 6, 2012

Turning an Idea into Story: Pack the plot full of action

I’ve been talking about turning an idea into a story by building a strong middle with an action-packed plot. Chances are, you have things happening throughout your story. After all, you’re writing about something. But just how exciting is the action?

I ghost-wrote a novel about a girl detective on a paleontology dig. I tried to capture life on a dig, with the long hours crouching in the dirt in the hot sun, and I included info about how fossils are preserved, found, and excavated. The editor said I needed to cut some of the nonfiction info about paleontology and have more action. She suggested using the desert setting more. I wrote a couple of new chapters where the girls get lured into the desert at night, get lost, and realize they are surrounded by coyotes. Hmm, crouching in the dirt or escaping coyotes at night—which sounds more exciting?

The author next to rock that (maybe) contains a dinosaur bone.As you develop the middle of your story, look for places to add more danger, more excitement, more tension. This is true even if you’re not writing an action story. If you’re writing a teen romance, your “danger” may be social danger.

The author next to rock that (maybe) contains a dinosaur bone.As you develop the middle of your story, look for places to add more danger, more excitement, more tension. This is true even if you’re not writing an action story. If you’re writing a teen romance, your “danger” may be social danger.In order to keep the tension high, check that your characters are struggling enough. How difficult have you made things? Can you make the situation worse? (Note that for younger readers, you may not want to choose the scariest or most difficult challenges. Keep your difficulties appropriate to your audience age.)

If your characters accomplish things too easily, try to add complications. As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, you might consider the “Rule of Three.” A character should try and fail twice, before succeeding on the third try. For a novel, a character might have to make several steps to reach their ultimate goal. You could use the Rule of Three at each step, to ensure that your character isn’t zipping through the challenges.

Exaggeration is a key to most strong fiction. You want your story to be believable, but that doesn’t mean it should be realistic, at least not in the everyday, normal sense. Most of us want to read about unusual characters having dramatic experiences. We already know about everyday life.

Dramatic exaggeration works for short stories and novels, in any genre, for any age group. I wrote a review of The Sandwich Swap for The New York Journal of Books. The authors took a real-life experience—an Arab girl’s disgust over her friend’s peanut butter and jelly sandwich, until she tried it—and turned it into a school-wide war. That turned a minor episode into a dramatic and entertaining picture book story. (Read the full review by clicking on the book’s title.)

Next week I’ll talk about raising the stakes to keep the tension high.

Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

Published on July 06, 2012 04:00

July 4, 2012

Tackling Tough Topics with Shannon Wiersbitzky

Here’s another namelos guest, Shannon Wiersbitzky, author of

The Summer of Hammers and Angels

, talking about how to handle tough topics in your writing. To see previous namelos posts, click on the headline banner above and then scroll down.

Tackling Tough Topics

As it turns out, many of the authors at namelos have tackled tough or potentially controversial issues and I expect you’ll continue to see tough topics on the list in the future. Between the five of us, our novels include characters that are dealing with child abuse, premature death, rape, war, and questions of faith.

For writers, tackling issues like these through writing may cause you to wonder. How many kids experience what I want to write about? Will they be able to relate to my character? Will the topic turn kids, teachers, or parents off? Will they understand the references to the topic?

With so many questions, where do you start?

Assess whether or not the topic is critical to the storyAs you consider your story, ask yourself how and why the topic comes into play. If it is central to your story line and to your character’s struggles and development, then by all means, write on! If it came to mind because an editor at a recent conference noted they’re looking for books about “issues” and you think you can “work it in” to your current novel, then maybe think twice.

Let your character(s) ask questions.With any tough topic, there are likely multiple viewpoints that exist. Consider sharing those viewpoints in your story as well. All characters won’t have the same perspective. That is where conflict arises! Let the reader mull over each new idea and come to their own conclusions about what they believe. Great book discussions will ensue.

In an interview with NPR, author Jodi Picoult discussed how she writes about tough topics. “I always look at it sort of like the facets of a diamond. You’ve got to illuminate each one, and then let the reader decide what’s the brightest one and why. My job isn’t to tell them which is the brightest one. It’s just to illuminate every single facet.”

Respect the topic. In my novel, The Summer of Hammers and Angels, the main character deals with questions of faith. I’ve spent time in all sorts of churches. Growing up, church was always part of my life. I mainly attended Lutheran and Presbyterian services with my parents, but during the summer, when I stayed with my grandparents, church had a whole different feel to it. On Sundays we were either at the Church of God or the Baptist Church. There was always singing, arms raised when the spirit moved, and shouts of Amen or Hallelujah or That’s right, when the pastor said something the congregation agreed with. As a kid I loved attending church where everyone got to be loud.

The church in my novel is a mish-mash of them all. The point wasn’t to portray one right way of doing things, or conversely to mock a way of believing. The story is meant to convey the way things happen in the fictional town of Tucker’s Ferry, West Virginia, in this one particular church community.

Be honest about the plot, the setting, and the characters. Don’t gussy up or gloss over what might be a tough scene. Dive in, let your character, and therefore your reader, experience whatever conflict, crisis, or pain may be taking place. As a writer this means you’ll have to go to that place too…which isn’t always easy.

In Alina Klein’s Rape Girl, there is a scene that struck me as being completely honest as I read it. During the scene, the main character is receiving a rape exam. “I kept drawing my knees together and Dr. Buckner kept prying them gently apart. All the while he picked up foot-long swabs and slick metal devices of torture, inserting and removing them without pause. I felt a tear drip down my temple toward my hair. Mom quietly brushed it away.”

Make it believable.When writing about tough topics, characters might find the road to happiness, they may come to a tragic end, or a million options in between. There isn’t one right answer. But whatever the answer, through the writing, readers must be absolutely convinced that it is the only outcome that could have occurred in that moment.

In No-Name Baby by Nancy Bo Flood, the main character, Sophie, is grappling with the early delivery of her baby brother. The entire family is stressed and it shows. ““Sophie, please, no questions. Not tonight.” Aunt Rae reached for the stack of cloths. “Let me help.”“No!” her aunt snapped.A loud moan came from upstairs. Then another. Papa flung open the door, his eyes wide. Aunt Rae crossed herself, murmuring, “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph have mercy.”A long, awful cry. A scream.Papa bolted up the stairs. Aunt Rae was right behind.Sophie couldn’t move.”

We need writers who are willing to take on life’s toughest topics. If they’ve touched us deeply enough to push us to write a book, then there most certainly are kids who would be drawn to these books and benefit from reading them.

Shannon Wiersbitzky wrote her first book in elementary school. Unfortunately she illustrated it too. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband and two sons.

The Summer of Hammers and Angels

, about a young girl who learns the power of love and community, is her first novel.

Shannon Wiersbitzky wrote her first book in elementary school. Unfortunately she illustrated it too. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband and two sons.

The Summer of Hammers and Angels

, about a young girl who learns the power of love and community, is her first novel.

Tackling Tough Topics

As it turns out, many of the authors at namelos have tackled tough or potentially controversial issues and I expect you’ll continue to see tough topics on the list in the future. Between the five of us, our novels include characters that are dealing with child abuse, premature death, rape, war, and questions of faith.

For writers, tackling issues like these through writing may cause you to wonder. How many kids experience what I want to write about? Will they be able to relate to my character? Will the topic turn kids, teachers, or parents off? Will they understand the references to the topic?

With so many questions, where do you start?

Assess whether or not the topic is critical to the storyAs you consider your story, ask yourself how and why the topic comes into play. If it is central to your story line and to your character’s struggles and development, then by all means, write on! If it came to mind because an editor at a recent conference noted they’re looking for books about “issues” and you think you can “work it in” to your current novel, then maybe think twice.

Let your character(s) ask questions.With any tough topic, there are likely multiple viewpoints that exist. Consider sharing those viewpoints in your story as well. All characters won’t have the same perspective. That is where conflict arises! Let the reader mull over each new idea and come to their own conclusions about what they believe. Great book discussions will ensue.

In an interview with NPR, author Jodi Picoult discussed how she writes about tough topics. “I always look at it sort of like the facets of a diamond. You’ve got to illuminate each one, and then let the reader decide what’s the brightest one and why. My job isn’t to tell them which is the brightest one. It’s just to illuminate every single facet.”

Respect the topic. In my novel, The Summer of Hammers and Angels, the main character deals with questions of faith. I’ve spent time in all sorts of churches. Growing up, church was always part of my life. I mainly attended Lutheran and Presbyterian services with my parents, but during the summer, when I stayed with my grandparents, church had a whole different feel to it. On Sundays we were either at the Church of God or the Baptist Church. There was always singing, arms raised when the spirit moved, and shouts of Amen or Hallelujah or That’s right, when the pastor said something the congregation agreed with. As a kid I loved attending church where everyone got to be loud.

The church in my novel is a mish-mash of them all. The point wasn’t to portray one right way of doing things, or conversely to mock a way of believing. The story is meant to convey the way things happen in the fictional town of Tucker’s Ferry, West Virginia, in this one particular church community.

Be honest about the plot, the setting, and the characters. Don’t gussy up or gloss over what might be a tough scene. Dive in, let your character, and therefore your reader, experience whatever conflict, crisis, or pain may be taking place. As a writer this means you’ll have to go to that place too…which isn’t always easy.

In Alina Klein’s Rape Girl, there is a scene that struck me as being completely honest as I read it. During the scene, the main character is receiving a rape exam. “I kept drawing my knees together and Dr. Buckner kept prying them gently apart. All the while he picked up foot-long swabs and slick metal devices of torture, inserting and removing them without pause. I felt a tear drip down my temple toward my hair. Mom quietly brushed it away.”

Make it believable.When writing about tough topics, characters might find the road to happiness, they may come to a tragic end, or a million options in between. There isn’t one right answer. But whatever the answer, through the writing, readers must be absolutely convinced that it is the only outcome that could have occurred in that moment.

In No-Name Baby by Nancy Bo Flood, the main character, Sophie, is grappling with the early delivery of her baby brother. The entire family is stressed and it shows. ““Sophie, please, no questions. Not tonight.” Aunt Rae reached for the stack of cloths. “Let me help.”“No!” her aunt snapped.A loud moan came from upstairs. Then another. Papa flung open the door, his eyes wide. Aunt Rae crossed herself, murmuring, “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph have mercy.”A long, awful cry. A scream.Papa bolted up the stairs. Aunt Rae was right behind.Sophie couldn’t move.”

We need writers who are willing to take on life’s toughest topics. If they’ve touched us deeply enough to push us to write a book, then there most certainly are kids who would be drawn to these books and benefit from reading them.

Shannon Wiersbitzky wrote her first book in elementary school. Unfortunately she illustrated it too. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband and two sons.

The Summer of Hammers and Angels

, about a young girl who learns the power of love and community, is her first novel.

Shannon Wiersbitzky wrote her first book in elementary school. Unfortunately she illustrated it too. She lives in Pennsylvania with her husband and two sons.

The Summer of Hammers and Angels

, about a young girl who learns the power of love and community, is her first novel.

Published on July 04, 2012 04:00

June 29, 2012

Turning an Idea into Story: Pump up the Drama

I talked last week about how I expanded The Ghost on the Stairs , to match Aladdin’s series guidelines. I added complications, and about 70 pages.

The editor read those revisions, but found a new problem. Some scenes lacked drama. He wanted it spookier, with the ghost more active.

I realized that some of my “detective” scenes didn’t directly involve the ghost at all. For example, I had the kids do research in the public library. They find information, and leave, with no drama. To keep the ghost involved, I moved their research session to the hotel’s business center and added this dramatic chapter ending.

[Tania] went out. I have to admit, I was glad to be alone for awhile…. It felt good to forget about ghosts and sisters and responsibilities, and just do regular stupid stuff.

Then I heard the scream.

This gave me a cliffhanger, and also inspired some new and dramatic action for the next chapter.

When adding complications, make sure the complications make the plot more interesting, rather than slowing it down. Complications should be dramatic, scary or emotional.

Avoid repetition in nonfiction as well. For

Milton Hershey: Young Chocolatier

(Childhood of Famous Americans series, written as M.M. Eboch), I portrayed his first bankruptcy in tragic, emotional detail. I knew the second one wouldn’t have as much impact, so I skimmed over it quickly and moved Milton on to new challenges.

Avoid repetition in nonfiction as well. For

Milton Hershey: Young Chocolatier

(Childhood of Famous Americans series, written as M.M. Eboch), I portrayed his first bankruptcy in tragic, emotional detail. I knew the second one wouldn’t have as much impact, so I skimmed over it quickly and moved Milton on to new challenges.Tip: Use variations on a theme. Don’t just repeat the same old argument between your hero and heroine or provide an identical example of your villain’s villainy. Add a twist, so it will feel fresh.

If you have similar scenes, place them in order from the easiest to hardest challenge, or add increasing stakes, such as time running out. Save the biggest confrontation for the climax.

Example: In Haunted Book 1: The Ghost on the Stairs , the kids make three trips to the local cemetery. The first time, they are with their mother in daylight. The second time, it’s dark and stormy, and they are alone. The final time, Tania has been possessed by a ghost. Three cemetery scenes, but each different enough to feel fresh—and each scarier than the last.

Tip: Give it a twist - new information that changes everything but still makes sense (such as Darth Vader revealing that he’s Luke’s father).

Next week: more tips on how to pack the plot full of action.

Advanced Plotting is packed full of articles on how to make your plot stronger. Get Advanced Plotting

on Amazon or B&N in paperback or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N in paperback or e-book.

Published on June 29, 2012 04:00

June 27, 2012

Did I Really Write Eddie’s War?: Carol Fisher Saller guest post

Today we continue the series of guest authors published by namelos. Carol Fisher Saller talks about writing her historical verse novel Eddie’s War with a little help from her friends. Here’s Carol:

I once calculated that when I was writing Eddie’s War , I averaged eleven and a half words a day. I’ve written elsewhere about how hard it was for me, and how I wrote the scenes out of order as they occurred to me without having a plot or getting to know my characters. I’d just think of a scene—a “vignette”—and write it. Here’s a short one:

May 1939Sarah Mulberry

In the first gradeshe was Sam,not even all that mucha girl.Smile as wide as her feet were long,feet made for puddle-jumping,fence-hopping,running from boys.She could bat a ball and fling a cobwith the rest of us.In junior high, though,she became Sarah,still flashing that smile,but avoiding the cob fights.Unless she wasprovoked.

Somehow all the little snippets did eventually coalesce, but not without help from friends, family, colleagues, my editor, and now and then—I’ll admit it—random strangers.

For a while I felt a little guilty using other peoples’ ideas, as though I were cheating. I’m guessing that’s normal for writers: First we resent the suggestion a little and resist it. Then we kick ourselves for not thinking of it ourselves. Finally, when we know that we really, really want to use that idea, we wonder whether it’s fair game.

But surely this is how most books get written. Even if a writer managed to seal herself up in a room and crank out a book with no contact with the outside world, she would still be drawing in some way on all the books and movies and conversations that are swirling in the soup of her subconscious.

So without shame, let me list some of the people who helped write Eddie’s War:

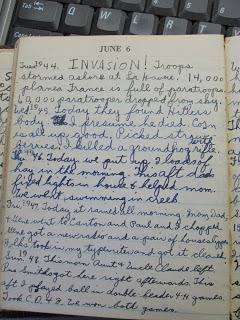

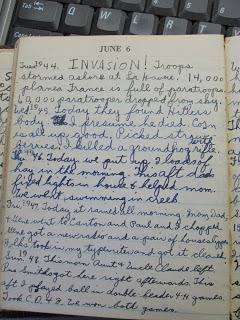

My father, who died in 1994. It’s no coincidence that my dad, like Eddie, was 12 when the war began and had an older brother who was a bomber pilot. Dad kept a little five-year diary during that time, and my book draws endlessly on the historical and farming details in the diary. I also took situations or incidents that Dad gave only a line or two in the diary and I expanded them into full-blown fictional events.

My writing group. Everyone in my writing group gave me excellent suggestions along the way—really too many to remember, let alone mention. One example: in an email response to an early draft, Beth Fama reminded me that before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Americans were not generally in favor of joining the war in Europe. I had forgotten that. Acknowledging my ignorance pushed me into doing a ton of reading and research that took the book up several notches in authenticity.

My editor. When I took the half-written manuscript to a workshop at the Highlights Foundation, Stephen Roxburgh gave me an exercise of writing a vignette in as few words as possible about a new character who would tell us something important about the main character. I thought up Grampa Rob and wrote a 47-word scene of him duck hunting, with Eddie. From that one short exercise two things happened: (1) I learned that Eddie was my main character, and (2) I introduced a major thread of dramatic tension. Incidentally, Stephen took a pencil and in about 30 seconds reduced the scene to 28 words*:

September 1938Duck Hunting

Hunkered in the duck blind,watching,trying to keep still,broken reedspoking through my jacket,I squirmed.Long fingerslike barn nailsgripped my neck:Grampa Rob.

A colleague. When I thought the book was finished, I gave it to a friend at work who is also a novelist, Joe Peterson. He had a lot of suggestions and criticisms, many of which I ignored as being not quite right for middle-grade/YA literature. But one complaint resonated: “As a guy,” he said, “I was really disappointed that you didn’t describe Eddie and Sarah’s date.” He insisted that boy readers would want to go on that date. And then he told me what should happen on the date. Listening to him describe it, I was bowled over. It was so perfect, so important—without it the book suddenly seemed horribly incomplete. Without it, Eddie’s coming-of-age would be totally botched! I rushed home and wrote “The Date.” In the months since the book came out, three (3!) different adult men who have read Eddie’s War have told me that “The Date” was their favorite scene.

A Stranger. In a cab on my way to the airport after the Highlights workshop, we drove along a scenic river, and when I commented on how beautiful it was, the cab driver told me that when he was a kid they used to walk across the river underwater, as a dare. Having a life-long fear of water myself, I was gripped by that tale, and when I got home I wrote “Walking the Spoon,” one of my favorite vignettes. Later, it was a bonus (thanks to Joe) that Eddie was able to revisit the Spoon and resolve things so perfectly in “The Date.”

So did I really write Eddie’s War? Of course I did. There’s a little slip of paper I keep tacked up over my desk that says “Nobody but me can write my books.” I really believe that. For better or worse, nobody but me could take all that grist and mill it exactly the way I did. Your way might be better than mine, but mine is mine, no matter how many people helped me along the way._____*When I sent her the post, Chris wanted to see the original 47-word version of this vignette. You can see how Stephen tightened it by trimming unneeded words—and how much punch it gained when he moved the first two words to the end. (I hope everyone appreciates my willingness to show my draft, warts and all!)

OriginalSeptember 1938Duck Hunting

Grampa Rob. A voice in the other room spoke the nameand Eddie remembered.Tall, silent. Eddie had been small,crouching in the duck blind, broken reeds poking through his jacket.When he squirmed,a hand gripped his neck, the long fingers like barn nails,a warning.

Carol Fisher Saller is a senior manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press and an editor of the

Chicago Manual of Style

. She has also worked as an editor of children’s books at Cricket Books. In addition to

Eddie’s War

, she is the author of

The Subversive Copyeditor: Advice from Chicago (or, How to Negotiate Good Relationships with Your Writers, Your Colleagues, and Yourself

) and currently writes for the

Lingua Franca

blog at the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Carol Fisher Saller is a senior manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press and an editor of the

Chicago Manual of Style

. She has also worked as an editor of children’s books at Cricket Books. In addition to

Eddie’s War

, she is the author of

The Subversive Copyeditor: Advice from Chicago (or, How to Negotiate Good Relationships with Your Writers, Your Colleagues, and Yourself

) and currently writes for the

Lingua Franca

blog at the Chronicle of Higher Education.

(See the earlier posts explaining namelos:

I once calculated that when I was writing Eddie’s War , I averaged eleven and a half words a day. I’ve written elsewhere about how hard it was for me, and how I wrote the scenes out of order as they occurred to me without having a plot or getting to know my characters. I’d just think of a scene—a “vignette”—and write it. Here’s a short one:

May 1939Sarah Mulberry

In the first gradeshe was Sam,not even all that mucha girl.Smile as wide as her feet were long,feet made for puddle-jumping,fence-hopping,running from boys.She could bat a ball and fling a cobwith the rest of us.In junior high, though,she became Sarah,still flashing that smile,but avoiding the cob fights.Unless she wasprovoked.

Somehow all the little snippets did eventually coalesce, but not without help from friends, family, colleagues, my editor, and now and then—I’ll admit it—random strangers.

For a while I felt a little guilty using other peoples’ ideas, as though I were cheating. I’m guessing that’s normal for writers: First we resent the suggestion a little and resist it. Then we kick ourselves for not thinking of it ourselves. Finally, when we know that we really, really want to use that idea, we wonder whether it’s fair game.

But surely this is how most books get written. Even if a writer managed to seal herself up in a room and crank out a book with no contact with the outside world, she would still be drawing in some way on all the books and movies and conversations that are swirling in the soup of her subconscious.

So without shame, let me list some of the people who helped write Eddie’s War:

My father, who died in 1994. It’s no coincidence that my dad, like Eddie, was 12 when the war began and had an older brother who was a bomber pilot. Dad kept a little five-year diary during that time, and my book draws endlessly on the historical and farming details in the diary. I also took situations or incidents that Dad gave only a line or two in the diary and I expanded them into full-blown fictional events.

My writing group. Everyone in my writing group gave me excellent suggestions along the way—really too many to remember, let alone mention. One example: in an email response to an early draft, Beth Fama reminded me that before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Americans were not generally in favor of joining the war in Europe. I had forgotten that. Acknowledging my ignorance pushed me into doing a ton of reading and research that took the book up several notches in authenticity.

My editor. When I took the half-written manuscript to a workshop at the Highlights Foundation, Stephen Roxburgh gave me an exercise of writing a vignette in as few words as possible about a new character who would tell us something important about the main character. I thought up Grampa Rob and wrote a 47-word scene of him duck hunting, with Eddie. From that one short exercise two things happened: (1) I learned that Eddie was my main character, and (2) I introduced a major thread of dramatic tension. Incidentally, Stephen took a pencil and in about 30 seconds reduced the scene to 28 words*:

September 1938Duck Hunting

Hunkered in the duck blind,watching,trying to keep still,broken reedspoking through my jacket,I squirmed.Long fingerslike barn nailsgripped my neck:Grampa Rob.

A colleague. When I thought the book was finished, I gave it to a friend at work who is also a novelist, Joe Peterson. He had a lot of suggestions and criticisms, many of which I ignored as being not quite right for middle-grade/YA literature. But one complaint resonated: “As a guy,” he said, “I was really disappointed that you didn’t describe Eddie and Sarah’s date.” He insisted that boy readers would want to go on that date. And then he told me what should happen on the date. Listening to him describe it, I was bowled over. It was so perfect, so important—without it the book suddenly seemed horribly incomplete. Without it, Eddie’s coming-of-age would be totally botched! I rushed home and wrote “The Date.” In the months since the book came out, three (3!) different adult men who have read Eddie’s War have told me that “The Date” was their favorite scene.

A Stranger. In a cab on my way to the airport after the Highlights workshop, we drove along a scenic river, and when I commented on how beautiful it was, the cab driver told me that when he was a kid they used to walk across the river underwater, as a dare. Having a life-long fear of water myself, I was gripped by that tale, and when I got home I wrote “Walking the Spoon,” one of my favorite vignettes. Later, it was a bonus (thanks to Joe) that Eddie was able to revisit the Spoon and resolve things so perfectly in “The Date.”

So did I really write Eddie’s War? Of course I did. There’s a little slip of paper I keep tacked up over my desk that says “Nobody but me can write my books.” I really believe that. For better or worse, nobody but me could take all that grist and mill it exactly the way I did. Your way might be better than mine, but mine is mine, no matter how many people helped me along the way._____*When I sent her the post, Chris wanted to see the original 47-word version of this vignette. You can see how Stephen tightened it by trimming unneeded words—and how much punch it gained when he moved the first two words to the end. (I hope everyone appreciates my willingness to show my draft, warts and all!)

OriginalSeptember 1938Duck Hunting

Grampa Rob. A voice in the other room spoke the nameand Eddie remembered.Tall, silent. Eddie had been small,crouching in the duck blind, broken reeds poking through his jacket.When he squirmed,a hand gripped his neck, the long fingers like barn nails,a warning.

Carol Fisher Saller is a senior manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press and an editor of the

Chicago Manual of Style

. She has also worked as an editor of children’s books at Cricket Books. In addition to

Eddie’s War

, she is the author of

The Subversive Copyeditor: Advice from Chicago (or, How to Negotiate Good Relationships with Your Writers, Your Colleagues, and Yourself

) and currently writes for the

Lingua Franca

blog at the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Carol Fisher Saller is a senior manuscript editor at the University of Chicago Press and an editor of the

Chicago Manual of Style

. She has also worked as an editor of children’s books at Cricket Books. In addition to

Eddie’s War

, she is the author of

The Subversive Copyeditor: Advice from Chicago (or, How to Negotiate Good Relationships with Your Writers, Your Colleagues, and Yourself

) and currently writes for the

Lingua Franca

blog at the Chronicle of Higher Education.(See the earlier posts explaining namelos:

Published on June 27, 2012 04:00

June 22, 2012

Turning an Idea into a Story: Making Muscular Action!

My Friday craft posts have been covering turning an idea into a story. Here are some more tips for building a strong middle by increasing the action.

“I love it,” the editor said. “I want to buy it.”

Words every writer wants to hear. But such joy does not come without a price. In this case, the editor followed those lovely phrases with “It needs to be twice as long.”

But I already had a plot that worked, and a nice fast pace! All in ... uh ... just over 80 pages. So yeah, that was short, even for a children’s novel. And since I was pitching

The Ghost on the Stairs

as the first in a series, it had to match Aladdin’s series guidelines for ages 9 to 12. So I had to add 70 pages, while keeping the story fast and active.

But I already had a plot that worked, and a nice fast pace! All in ... uh ... just over 80 pages. So yeah, that was short, even for a children’s novel. And since I was pitching

The Ghost on the Stairs

as the first in a series, it had to match Aladdin’s series guidelines for ages 9 to 12. So I had to add 70 pages, while keeping the story fast and active.Some of you are going, “Yeah, right—I always need to cut, not expand.” That’s a common problem for many, but filling out a story with exciting, dramatic material can cause challenges as well—especially in the middle, where plots can sag and slow. I also see a lot of beginning children’s writers with manuscript in the 5000- to 20,000-word range, a tough sell unless you are doing leveled readers—which often have a very specific word count for each age level. Adult novelists may wind up with novellas, where a full-length novel would have better market opportunities.

So how do you build a bigger manuscript, while keeping it lean and muscular, not padded with fat descriptions or flabby repetition? I studied books on plotting, including Elements of Fiction Writing - Beginnings, Middles & Ends

(Nancy Kress, Writers Digest Books) and came up with the several literary “protein shakes” to feed my novel. This week, we’ll look at how to:

(Nancy Kress, Writers Digest Books) and came up with the several literary “protein shakes” to feed my novel. This week, we’ll look at how to:Add More Plot

In my Haunted series, siblings Jon and Tania travel with their mother and stepfather’s ghost hunter TV show, and discover Tania can see ghosts. In each book, they have to figure out what’s keeping the ghost here, then try to help her or him move on. In the version of The Ghost on the Stairs I sent to the editor, people already knew the ghost’s name and why she’s stuck here grieving. To expand the manuscript, I made the ghost story more vague. Jon and Tania have to do detective work to discover her name and background.

Exercise: Make a plot outline of your manuscript, with a sentence or two describing what happens in each scene. How easily does your main character solve his problems? Can you make it more difficult, by requiring more steps or adding complications? Can you add complications to your complications, turning small steps into big challenges?

Example: In Haunted Book 2:

The Riverboat Phantom

, a ghost grabs Jon.

Example: In Haunted Book 2:

The Riverboat Phantom

, a ghost grabs Jon.I felt the cold first on my arms, like icy vice grips squeezing my biceps. Then waves of cold flowed down to my hands, up to my shoulders, all through my body. I tried to breathe, but my chest felt too tight. My vision blurred, darkened. The last thing I saw was Tania’s horrified face. And I fell.

That’s dramatic enough for a chapter ending. So what’s next? It would be easiest—for Jon and the writer—if Tania is still the only one there when he recovers, and no one else notices his collapse. But if everyone notices, and Jon has to convince his worried mother that he’s not sick, you get complications.

Coming next week, more tips on how to pump up the drama in your writing.

Advanced Plotting has tons of advice on building strong plots. Get Advanced Plotting

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

on Amazon or B&N, in print or e-book.

Published on June 22, 2012 04:00

June 20, 2012

Heart, You’ve Got to Have Heart: Nancy Bo Flood from namelos

Nancy Bo Flood, one of the namelos authors we’ve met over the last two weeks, shares her insight into the craft of writing. Here she discusses Heart, You’ve Got to Have Heart:

But, you may argue, I am writing a nonfiction nature book…or a fantasy…or a picture-book biography. It doesn’t matter. If you want your reader to keep turning the pages, your manuscript must have heart. Emotion.

Emotion connects the information, the meaning and the reader. It is this emotional connection to a story unfolding or facts unfolding that enables us to remember what we experience. If your manuscript has heart, your reader will remember what you wrote.

How does a writer create heart or emotion? Through story. Through creating “intent,” the overall theme or meaning of a book. When someone asks you, what was that book about? Your reply, if your remember anything about the book, will be a description of the book’s theme. Charlotte’s Web is about letting go of someone we love. Yes, the book is about a girl, a pig and a spider. That sounds pretty hokey, doesn’t it? But what the book really is about, is love and death, which is what we remember.

How does an author develop intent, the emotional power of a book, fiction or nonfiction? First, you do your research. You learn what you must know in order to write an authentic, accurate setting and an interesting unfolding of events or facts. Next, discover the story line. Weave it through the entire manuscript. Create a story arc.

When I wrote a nonfiction picture book about sandstone, Sand to Stone and Back Again, sedimentary rock became my main character. First I did the research – indeed, I read dozens of geology books to write less than a thousand words about sandstone. The tough challenge was finding the “way in,” discovering the connection between my subject and the reader, in other words, discovering my “intent,” what I really wanted to say about sandstone. I asked myself, how could I make sandstone relevant to a third-grader?

My hook, my way in, my connection to the reader, developed from my intent. What I really cared about was the mystery that stone is always changing, just like that third-grade child:

“You began as one tiny cell, as small as a grain of sand. From one cell, you became two, then four. Now you are made of millions of connected cells. From one tiny cell, you became a person. From one grain of sand, I became a mountain.” Sandstone is always changing, just like you.

Writing memorable fiction or nonfiction requires research that allows the writer to thoroughly know the subject but most important, find the story, your intention, the real meaning. Intention is the emotional answer to “so what, why are these facts or this story important?” Within your work’s intention, whether fiction or nonfiction, is the real treasure, the heart, the emotional connection between the story and your reader.

Nancy Bo Flood is a counselor, teacher, and parent. She has conducted workshops on child abuse, learning disabilities, play therapy, and creative writing. Ms. Flood has lived in Malawi, Hawaii, Japan, and Saipan, where her first novel, Warriors in the Crossfire , is set. She lives on the Navajo Nation reservation, near Flagstaff, Arizona. Her namelos book,

But, you may argue, I am writing a nonfiction nature book…or a fantasy…or a picture-book biography. It doesn’t matter. If you want your reader to keep turning the pages, your manuscript must have heart. Emotion.

Emotion connects the information, the meaning and the reader. It is this emotional connection to a story unfolding or facts unfolding that enables us to remember what we experience. If your manuscript has heart, your reader will remember what you wrote.

How does a writer create heart or emotion? Through story. Through creating “intent,” the overall theme or meaning of a book. When someone asks you, what was that book about? Your reply, if your remember anything about the book, will be a description of the book’s theme. Charlotte’s Web is about letting go of someone we love. Yes, the book is about a girl, a pig and a spider. That sounds pretty hokey, doesn’t it? But what the book really is about, is love and death, which is what we remember.

How does an author develop intent, the emotional power of a book, fiction or nonfiction? First, you do your research. You learn what you must know in order to write an authentic, accurate setting and an interesting unfolding of events or facts. Next, discover the story line. Weave it through the entire manuscript. Create a story arc.

When I wrote a nonfiction picture book about sandstone, Sand to Stone and Back Again, sedimentary rock became my main character. First I did the research – indeed, I read dozens of geology books to write less than a thousand words about sandstone. The tough challenge was finding the “way in,” discovering the connection between my subject and the reader, in other words, discovering my “intent,” what I really wanted to say about sandstone. I asked myself, how could I make sandstone relevant to a third-grader?

My hook, my way in, my connection to the reader, developed from my intent. What I really cared about was the mystery that stone is always changing, just like that third-grade child:

“You began as one tiny cell, as small as a grain of sand. From one cell, you became two, then four. Now you are made of millions of connected cells. From one tiny cell, you became a person. From one grain of sand, I became a mountain.” Sandstone is always changing, just like you.

Writing memorable fiction or nonfiction requires research that allows the writer to thoroughly know the subject but most important, find the story, your intention, the real meaning. Intention is the emotional answer to “so what, why are these facts or this story important?” Within your work’s intention, whether fiction or nonfiction, is the real treasure, the heart, the emotional connection between the story and your reader.

Nancy Bo Flood is a counselor, teacher, and parent. She has conducted workshops on child abuse, learning disabilities, play therapy, and creative writing. Ms. Flood has lived in Malawi, Hawaii, Japan, and Saipan, where her first novel, Warriors in the Crossfire , is set. She lives on the Navajo Nation reservation, near Flagstaff, Arizona. Her namelos book,

Published on June 20, 2012 04:00