Chris Eboch's Blog, page 34

February 24, 2012

Plot/Character Exercises

We've been talking about how conflict comes from the interaction between character and plot. Let's look more closely at character.

Six basic human needs influence character:

Growth (working toward a personal goal)

Contribution (feeling needed, worthwhile)

Security (knowing the future)

Change (desire for variety, excitement)

Connection (feeling part of a group)

Independence (personal identity and freedom)

Which of these are most important to your main character? Create conflict by setting up situations which oppose that person's needs.

Exercise—Write a story, starting with plot.

Come up with a challenge – a difficult situation for someone. This can be anything from facing the first day of school to wanting to make a sports team to solving a crime to fighting zombies.

Then ask, What kind of person would have the most trouble in that situation? Plan or write a story about that character in that situation.

Exercise—Write a story, starting with character.

Write a brief character sketch, covering basics such as gender, age, personality characteristics – introvert/extrovert, optimist/pessimist, etc. – with a few likes and dislikes. You can base this on someone you know.

How would they define or describe themselves? ("I always…I never…I'm the kind of person who….")

• If these statements are true, a situation that challenges the belief will create conflict. For example, if you have a character who is honest, put him in a situation where there is a good reason to lie.

• If these statements are false, a situation that exposes the delusion will create conflict. For example, if someone sees himself as courageous, but isn't really, a situation that requires courage will be especially painful because it shakes up his view of himself.

So, what situation will most challenge this character? Summarize or write a story about that character in that situation.

You know you need both an interesting character and a strong plot to make a good story. As you develop an idea, think about how your character and plot interact, and design your character for your plot. As you write the story, work back and forth between plot and character.

One more exercise:

Look at your work in progress. What is the problem? Why is it important? Why is it difficult? (See the post From Idea to Story Part 2: Setting up Conflict.)

Given those answers, is your character the right character for that situation? Could you give your character different needs or desires, to make the situation more difficult for him or her?

Six basic human needs influence character:

Growth (working toward a personal goal)

Contribution (feeling needed, worthwhile)

Security (knowing the future)

Change (desire for variety, excitement)

Connection (feeling part of a group)

Independence (personal identity and freedom)

Which of these are most important to your main character? Create conflict by setting up situations which oppose that person's needs.

Exercise—Write a story, starting with plot.

Come up with a challenge – a difficult situation for someone. This can be anything from facing the first day of school to wanting to make a sports team to solving a crime to fighting zombies.

Then ask, What kind of person would have the most trouble in that situation? Plan or write a story about that character in that situation.

Exercise—Write a story, starting with character.

Write a brief character sketch, covering basics such as gender, age, personality characteristics – introvert/extrovert, optimist/pessimist, etc. – with a few likes and dislikes. You can base this on someone you know.

How would they define or describe themselves? ("I always…I never…I'm the kind of person who….")

• If these statements are true, a situation that challenges the belief will create conflict. For example, if you have a character who is honest, put him in a situation where there is a good reason to lie.

• If these statements are false, a situation that exposes the delusion will create conflict. For example, if someone sees himself as courageous, but isn't really, a situation that requires courage will be especially painful because it shakes up his view of himself.

So, what situation will most challenge this character? Summarize or write a story about that character in that situation.

You know you need both an interesting character and a strong plot to make a good story. As you develop an idea, think about how your character and plot interact, and design your character for your plot. As you write the story, work back and forth between plot and character.

One more exercise:

Look at your work in progress. What is the problem? Why is it important? Why is it difficult? (See the post From Idea to Story Part 2: Setting up Conflict.)

Given those answers, is your character the right character for that situation? Could you give your character different needs or desires, to make the situation more difficult for him or her?

Published on February 24, 2012 04:00

February 22, 2012

Selling Books with a Loss Leader

Last week I talked about the importance of having multiple books available, if you are an indie author. This gives potential readers several "entry points" to your work, and can also mean every successful act of publicity leads to multiple sales to one customer. Having several books available also provides special publicity opportunities.

I can also make use of publicity tactics such as a "loss leader" title. This means you offer one book at a deep discount, or even free. People are much more likely to try a free book. If they like it, they are more likely to pay several dollars for other books by that author.

Many writers trying self-publishing offer their first book for free, trying to gain fans. But how much does it help you to have a new fan, if you don't have anything else for them to buy? Will they remember you in six months or a year when you get another book out? Will they even recognize your name if Amazon recommends your next book? The whole point of a "loss leader" is to drive sales to your regularly-priced books. It's pointless if you only have one title out.

One note – many indie authors offer all their books for free hoping to build readership. Many readers have gotten burned by books that are mediocre or worse. Some readers now refuse to buy $.99 e-books and won't even "waste their time" trying free books. However, if you have a normal price of $3-6 and offering that book for free for a limited time, you can bypass some of the stigma associated with free books.

So that's why I'm focusing first on getting two more books published. Once I have four on the market, I may take a few months off to do a major publicity push. That's not to say I'm doing nothing now – of course I'm telling friends about my books, mentioning them in context on blog posts here or in guest blog posts, sharing news on Facebook, and so forth. But I can resist the pressure to spend dozens of hours a week just focused on publicity. Writing the next book is more important.

"Hey, this book is available now!"This also gives me time to learn more about what seems to work and what doesn't with publicity. I can explore some new social networks, test out a few things in small ways, and in general prepare now so I won't be overwhelmed later. I can even tweak cover art, description blurbs, tag words and so forth to find the best combination for selling my work.

"Hey, this book is available now!"This also gives me time to learn more about what seems to work and what doesn't with publicity. I can explore some new social networks, test out a few things in small ways, and in general prepare now so I won't be overwhelmed later. I can even tweak cover art, description blurbs, tag words and so forth to find the best combination for selling my work.And I don't have to feel bad if I only sell 10 copies of a title in a month. 10 copies is a drop in the pool, and maybe the ripples will start reaching out now. In the meantime, I can focus on writing the next book.

Published on February 22, 2012 04:00

February 17, 2012

Write a Strong Plot: Be Cruel to Your Characters

For a strong plot, you need plenty of dramatic action. (This doesn't necessarily mean fights and car chases. The drama can come from interpersonal relationships or even a person's own thoughts. But dramatic things should happen.) But it's not enough just to have dramatic things happening. It's not just What but also Who.

Your main character needs to be able to overcome the challenge you set for him – but just barely. We don't want to watch superheroes fight weaklings. We want to watch superheroes fight supervillains – or even better, weaklings fight supervillains, and barely win, through courage and ingenuity that overcome the stronger foe.

Conflict comes from the interaction between character and plot. You can create conflict by setting up situations which force a person to confront their fears. If someone is afraid of heights, make them go someplace high. If they're afraid of taking responsibility, force them to be in charge.

You can also create conflict by setting up situations which oppose a person's desires. If they crave safety, put them in danger. But if they crave danger, keep them out of it.

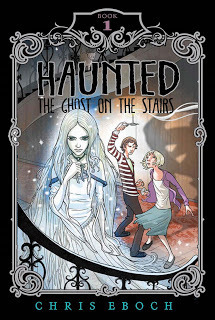

In The Well of Sacrifice, Eveningstar never dreams of being a leader or a rebel. But when her family, the government, and even the gods fail to stop the evil high priest, she's forced to act. In the Haunted series, Jon would like to be an ordinary kid and stay out of trouble. But his sister is determined to help ghosts without letting the grown-ups know what she and Jon are doing, and is constantly getting him into trouble. The reluctant hero is a staple of books and movies because it's fun to watch someone forced into a heroic role when they don't want it. (Think of Harrison Ford as Han Solo.)

In The Well of Sacrifice, Eveningstar never dreams of being a leader or a rebel. But when her family, the government, and even the gods fail to stop the evil high priest, she's forced to act. In the Haunted series, Jon would like to be an ordinary kid and stay out of trouble. But his sister is determined to help ghosts without letting the grown-ups know what she and Jon are doing, and is constantly getting him into trouble. The reluctant hero is a staple of books and movies because it's fun to watch someone forced into a heroic role when they don't want it. (Think of Harrison Ford as Han Solo.)

Even with nonfiction, you can create tension by focusing on the challenges that make a person's accomplishments more impressive. In my book Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker, written under the name M.M. Eboch, I made this incredible athlete's story more powerful by focusing on all the things he had to overcome – childhood health problems, poverty, a poor education. In Milton Hershey: Young Chocolatier (also written as M.M. Eboch) the story of the man who founded Hershey's chocolate is more dramatic because he started with little business experience, and had an unfortunate habit of trusting his overzealous father.

Exercise: Ask yourself these questions. They may lead to new story ideas, or you can use them to further develop characters in your current work.

What are you afraid of?

What's the hardest thing you have had to do or overcome?

What's the hardest thing you've done by choice?

Ask other people the same questions, for more ideas.

Your main character needs to be able to overcome the challenge you set for him – but just barely. We don't want to watch superheroes fight weaklings. We want to watch superheroes fight supervillains – or even better, weaklings fight supervillains, and barely win, through courage and ingenuity that overcome the stronger foe.

Conflict comes from the interaction between character and plot. You can create conflict by setting up situations which force a person to confront their fears. If someone is afraid of heights, make them go someplace high. If they're afraid of taking responsibility, force them to be in charge.

You can also create conflict by setting up situations which oppose a person's desires. If they crave safety, put them in danger. But if they crave danger, keep them out of it.

In The Well of Sacrifice, Eveningstar never dreams of being a leader or a rebel. But when her family, the government, and even the gods fail to stop the evil high priest, she's forced to act. In the Haunted series, Jon would like to be an ordinary kid and stay out of trouble. But his sister is determined to help ghosts without letting the grown-ups know what she and Jon are doing, and is constantly getting him into trouble. The reluctant hero is a staple of books and movies because it's fun to watch someone forced into a heroic role when they don't want it. (Think of Harrison Ford as Han Solo.)

In The Well of Sacrifice, Eveningstar never dreams of being a leader or a rebel. But when her family, the government, and even the gods fail to stop the evil high priest, she's forced to act. In the Haunted series, Jon would like to be an ordinary kid and stay out of trouble. But his sister is determined to help ghosts without letting the grown-ups know what she and Jon are doing, and is constantly getting him into trouble. The reluctant hero is a staple of books and movies because it's fun to watch someone forced into a heroic role when they don't want it. (Think of Harrison Ford as Han Solo.)Even with nonfiction, you can create tension by focusing on the challenges that make a person's accomplishments more impressive. In my book Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker, written under the name M.M. Eboch, I made this incredible athlete's story more powerful by focusing on all the things he had to overcome – childhood health problems, poverty, a poor education. In Milton Hershey: Young Chocolatier (also written as M.M. Eboch) the story of the man who founded Hershey's chocolate is more dramatic because he started with little business experience, and had an unfortunate habit of trusting his overzealous father.

Exercise: Ask yourself these questions. They may lead to new story ideas, or you can use them to further develop characters in your current work.

What are you afraid of?

What's the hardest thing you have had to do or overcome?

What's the hardest thing you've done by choice?

Ask other people the same questions, for more ideas.

Published on February 17, 2012 04:00

February 14, 2012

Stop the Insanity! Publicity Can Wait

I'm doing a series of Wednesday posts discussing my career decisions and the reasons behind them. Last time I talked about committing to indie publishing. Now I'll go into some specific details.

Decision #4: Focus on writing four books. Save major publicity for later.

With traditional publishing, debut authors face a lot of pressure to make their first book a success. The logic is sound: if your book does well, especially in the first six months, your publisher is more likely to acquire your second book. (Sadly, the days when publishers would stand behind a promising author for three or four books, helping them to build their reputation, are largely gone, at least at the bigger publishers.)

With self-publishing, you don't have that pressure for initial success. Sure, we'd all like our first book out to be a huge success. But you don't have to worry about your sales numbers impressing the bean counters.

In fact, there are good reasons to delay a major publicity push. Few people agree on what makes a self-published book a success, but the experts do seem to agree on one thing – for an author to find success through self-publishing, she needs to have multiple books available.

This works in a couple of ways. First of all, with several books, you broaden your appeal. You have more ways for readers to find your work. For example, with Rattled, I decided to experiment with a cover that suggested more of an adventure, rather than the traditional romantic suspense cover (quite often a couple of naked torsos embracing, with a dark blue wash). Rattled may attract readers who don't normally go for romantic suspense, but it may not appeal to romantic suspense readers. On the other hand, the Whispers in the Dark cover is much more standard for romantic suspense. If I can appeal to readers with one or the other, and they like that book, they are more likely to try the other one, regardless of cover.

This works in a couple of ways. First of all, with several books, you broaden your appeal. You have more ways for readers to find your work. For example, with Rattled, I decided to experiment with a cover that suggested more of an adventure, rather than the traditional romantic suspense cover (quite often a couple of naked torsos embracing, with a dark blue wash). Rattled may attract readers who don't normally go for romantic suspense, but it may not appeal to romantic suspense readers. On the other hand, the Whispers in the Dark cover is much more standard for romantic suspense. If I can appeal to readers with one or the other, and they like that book, they are more likely to try the other one, regardless of cover. Your blurbs work in similar ways. Rattled is a "treasure hunting adventure in New Mexico." Whispers in the Dark is about "a young archaeologist who stumbles into danger as mysteries unfold among ancient Southwest ruins." Both fit my tagline of "Ordinary Women, Extraordinary Adventures" and my Kris Bock "brand" of action in southwestern settings. But some people might find the idea of an archaeologist and ancient ruins more appealing, while others might think a treasure hunting adventure sounds fun.

Your blurbs work in similar ways. Rattled is a "treasure hunting adventure in New Mexico." Whispers in the Dark is about "a young archaeologist who stumbles into danger as mysteries unfold among ancient Southwest ruins." Both fit my tagline of "Ordinary Women, Extraordinary Adventures" and my Kris Bock "brand" of action in southwestern settings. But some people might find the idea of an archaeologist and ancient ruins more appealing, while others might think a treasure hunting adventure sounds fun.In short, the more books you have, the more "entry points" readers have for your work.

But that's not the only reason to focus on getting several books out before doing publicity. With multiple books, every act of publicity automatically has the potential for greater effect. If I sell one book, I might sell several others to that customer. If readers bought one, Amazon should tell them "You might also like" other Kris Bock books.

Next week I'll continue this thread, talking about publicity tactics such as the discount "loss leader."

Published on February 14, 2012 14:25

February 3, 2012

How to Turn Your Idea into a Story: More Conflict!

Here are a few more tips on setting up conflict, following last week's lesson:

• What does your main character want? What does he need? Make these things different, and you'll add tension to the story. It can be as simple as our soccer player who wants to practice soccer, but needs to study. Or it could be more subtle, like someone who wants to be protected but needs to learn independence. In the Haunted books, Jon wants to be a regular kid, and fit in, but needs to protect his sister – who gets him into trouble and embarrassing situations. This increases the tension and gives the reader sympathy for my main character. (For a more detailed explanation of character want versus need, exploring the movie ET as an example, see my brother Doug Eboch's Let's Schmooze blog on Screenwriting, E.T. Analysis Part 11.)

• What does your main character want? What does he need? Make these things different, and you'll add tension to the story. It can be as simple as our soccer player who wants to practice soccer, but needs to study. Or it could be more subtle, like someone who wants to be protected but needs to learn independence. In the Haunted books, Jon wants to be a regular kid, and fit in, but needs to protect his sister – who gets him into trouble and embarrassing situations. This increases the tension and gives the reader sympathy for my main character. (For a more detailed explanation of character want versus need, exploring the movie ET as an example, see my brother Doug Eboch's Let's Schmooze blog on Screenwriting, E.T. Analysis Part 11.)

• Even if your main problem is external (man versus man or man versus nature), consider giving the character an internal flaw(man versus himself) that contributes to the difficulty. For a few examples of internal flaws, see the seven deadly sins: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy and pride. Perhaps your character has a temper, or is lazy, or refuses to ever admit she's wrong. This helps set up your complications, and as a bonus makes your character seem more real. (We'll discuss characterization in more depth in coming weeks.)

• Before you start, test the idea. Change the character's age, gender, or looks. Change the point of view. Change the setting. Change the external conflict. Change the internal conflict. What happens? Choose the combination that has the most dramatic potential. For example, my work in progress started with two female cousins visiting. I changed one into a boy, and added a girl friend next door, which made for nice boy/girl tension behind the main plot.

• What does your main character want? What does he need? Make these things different, and you'll add tension to the story. It can be as simple as our soccer player who wants to practice soccer, but needs to study. Or it could be more subtle, like someone who wants to be protected but needs to learn independence. In the Haunted books, Jon wants to be a regular kid, and fit in, but needs to protect his sister – who gets him into trouble and embarrassing situations. This increases the tension and gives the reader sympathy for my main character. (For a more detailed explanation of character want versus need, exploring the movie ET as an example, see my brother Doug Eboch's Let's Schmooze blog on Screenwriting, E.T. Analysis Part 11.)

• What does your main character want? What does he need? Make these things different, and you'll add tension to the story. It can be as simple as our soccer player who wants to practice soccer, but needs to study. Or it could be more subtle, like someone who wants to be protected but needs to learn independence. In the Haunted books, Jon wants to be a regular kid, and fit in, but needs to protect his sister – who gets him into trouble and embarrassing situations. This increases the tension and gives the reader sympathy for my main character. (For a more detailed explanation of character want versus need, exploring the movie ET as an example, see my brother Doug Eboch's Let's Schmooze blog on Screenwriting, E.T. Analysis Part 11.) • Even if your main problem is external (man versus man or man versus nature), consider giving the character an internal flaw(man versus himself) that contributes to the difficulty. For a few examples of internal flaws, see the seven deadly sins: lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy and pride. Perhaps your character has a temper, or is lazy, or refuses to ever admit she's wrong. This helps set up your complications, and as a bonus makes your character seem more real. (We'll discuss characterization in more depth in coming weeks.)

• Before you start, test the idea. Change the character's age, gender, or looks. Change the point of view. Change the setting. Change the external conflict. Change the internal conflict. What happens? Choose the combination that has the most dramatic potential. For example, my work in progress started with two female cousins visiting. I changed one into a boy, and added a girl friend next door, which made for nice boy/girl tension behind the main plot.

Published on February 03, 2012 04:00

February 1, 2012

Career Decisions: Writing for e-Readers

I've done two previous posts discussing some of my decisions for my career. First was committing to indie publishing for my adult genre fiction. Second was writing shorter books. The third decision is pretty simple, though my reasons may not be obvious.

Decision #3: Use shorter paragraphs.

I like to use a lot of short paragraphs anyway, as I think it can help the reader's eyes move more quickly down the page, helping to give the impression that the story is moving quickly. Short paragraphs are ideal for action scenes and cliffhanger chapter endings. I've discussed this technique in previous posts such as Write Better with Powerful Paragraphing and Paragraphing for Cliffhangers and in the Advanced Plotting essay Hanging by the Fingernails.

I like to use a lot of short paragraphs anyway, as I think it can help the reader's eyes move more quickly down the page, helping to give the impression that the story is moving quickly. Short paragraphs are ideal for action scenes and cliffhanger chapter endings. I've discussed this technique in previous posts such as Write Better with Powerful Paragraphing and Paragraphing for Cliffhangers and in the Advanced Plotting essay Hanging by the Fingernails. But of course you don't want your work to be a string of one-sentence paragraphs. Sometimes it's more appropriate, or just feels natural, to have a longer paragraph. This often happens with description or introspection. Adult books often use longer paragraphs, on average, than children's books. Literary titles and fantasy may use longer paragraphs than thrillers. Shorter isn't always "right" or better.

However, it's worth keeping in mind that many people are reading on electronic devices today. That changes the way a book is laid out. Forget about all the work a book designer does to make the text readable. With e-books, the users set their preference on their device. The user chooses the size of font and the spacing of the words. Plus, some people are reading on phones or other small screens, so they get only a few lines per "page."

What does that mean for a writer? Well, it means a paragraph that takes up a few lines on your manuscript might wind up taking an entire page on a small screen or where the user has set a large font size. In my personal experience, a paragraph that takes up an entire page is harder to read – it's harder for your eyes to track back and forth from the end of one line to the beginning of the next line. This is true regardless of the size of the font (though it's even worse with a small font and dozens of lines on the page).

I noticed this after publishing

Rattled

. I went over the print on demand version carefully, making sure the text looked good on the printed page. I broke a few long paragraphs into shorter ones, because what looked right on an 81/2 x 11 manuscript printout seemed unwieldy in the 5 x 8 book. I got it looking pretty.

I noticed this after publishing

Rattled

. I went over the print on demand version carefully, making sure the text looked good on the printed page. I broke a few long paragraphs into shorter ones, because what looked right on an 81/2 x 11 manuscript printout seemed unwieldy in the 5 x 8 book. I got it looking pretty.But when I looked at the electronic version and tested different font sizes, the book suddenly seemed to have huge blocks of text. It almost seemed like I'd forgotten paragraphing existed in some places! I've noticed that in other authors' books as well, and the larger blocks of text are harder to read. Not a lot, but just that little bit.

We live in an increasingly digital world, so it's worth considering how your books will read on electronic devices. On my blog posts, I try to keep my paragraphs to no more than four or five lines in a Word document, knowing that will become more on the narrower blog post. For my books, if I see a paragraph going more than five or six lines, I look for a natural place to break it.

While this may not seem like a career decision, keeping up with technology and understanding how people read is part of a writer's career. My goal is to have my work read, understood, and enjoyed. I think shorter paragraphs will help.

See Kris Bock's books on Amazon or Barnes & Noble

See Kris Bock's books on Amazon or Barnes & Noble

Published on February 01, 2012 04:00

January 27, 2012

How to Turn Your Idea into a Story: Setting up Conflict

To develop your story, you'll need conflict. But conflict doesn't just come from dramatic things happening. It comes from the character – what he or she needs and wants, and why he or she can't get it easily.

Start with a premise: a kid has a math test on Monday. Exciting? Not really. But ask two simple questions, and you can add conflict.

• Why is it important to the character? The stakes should be high. The longer the story or novel, the higher stakes you need to sustain it. A short story character might want to win a contest; a novel character might need to save the world.

• Why is it difficult for the character? Difficulties can be divided into three general categories, traditionally called man versus man, man versus nature, and man versus himself. You can even have a combination of these. For example, someone may be trying to spy on some bank robbers (man versus man) during a dangerous storm (man versus nature) when he is afraid of lightning (man versus himself).

Get more tips like these in

Advanced Plotting

.Back to the kid with the math test. Let's say, if he doesn't pass, maybe he will fail the class, have to go to summer school, and not get to go to soccer camp, when soccer is what he loves most, and all his friends will be going. That's why it's important. Assuming we create a character readers will like, they'll care about the outcome of this test, and root for him to succeed.

Get more tips like these in

Advanced Plotting

.Back to the kid with the math test. Let's say, if he doesn't pass, maybe he will fail the class, have to go to summer school, and not get to go to soccer camp, when soccer is what he loves most, and all his friends will be going. That's why it's important. Assuming we create a character readers will like, they'll care about the outcome of this test, and root for him to succeed.

Our soccer lover could have lots of challenges—he forgot his study book, he's expected to baby-sit his distracting little sister, a storm knocked out the power, he has ADHD, or he suffers test anxiety. But ideally we would relate the difficulty to the reason it's important. So let's say he has a big soccer game Sunday afternoon, and is getting pressure from his coach and teammates to practice rather than study for his test. Plus, of course, he'd rather play soccer anyway.

We now have a situation full of potential tension. Let the character struggle enough before he succeeds (or fails and learns a lesson), and you'll have a story. And if these two questions can pump up a dull premise, just think what they can do with an exciting one!

Come back next week for more tips on linking your conflict to your character.

Start with a premise: a kid has a math test on Monday. Exciting? Not really. But ask two simple questions, and you can add conflict.

• Why is it important to the character? The stakes should be high. The longer the story or novel, the higher stakes you need to sustain it. A short story character might want to win a contest; a novel character might need to save the world.

• Why is it difficult for the character? Difficulties can be divided into three general categories, traditionally called man versus man, man versus nature, and man versus himself. You can even have a combination of these. For example, someone may be trying to spy on some bank robbers (man versus man) during a dangerous storm (man versus nature) when he is afraid of lightning (man versus himself).

Get more tips like these in

Advanced Plotting

.Back to the kid with the math test. Let's say, if he doesn't pass, maybe he will fail the class, have to go to summer school, and not get to go to soccer camp, when soccer is what he loves most, and all his friends will be going. That's why it's important. Assuming we create a character readers will like, they'll care about the outcome of this test, and root for him to succeed.

Get more tips like these in

Advanced Plotting

.Back to the kid with the math test. Let's say, if he doesn't pass, maybe he will fail the class, have to go to summer school, and not get to go to soccer camp, when soccer is what he loves most, and all his friends will be going. That's why it's important. Assuming we create a character readers will like, they'll care about the outcome of this test, and root for him to succeed.Our soccer lover could have lots of challenges—he forgot his study book, he's expected to baby-sit his distracting little sister, a storm knocked out the power, he has ADHD, or he suffers test anxiety. But ideally we would relate the difficulty to the reason it's important. So let's say he has a big soccer game Sunday afternoon, and is getting pressure from his coach and teammates to practice rather than study for his test. Plus, of course, he'd rather play soccer anyway.

We now have a situation full of potential tension. Let the character struggle enough before he succeeds (or fails and learns a lesson), and you'll have a story. And if these two questions can pump up a dull premise, just think what they can do with an exciting one!

Come back next week for more tips on linking your conflict to your character.

Published on January 27, 2012 04:00

January 25, 2012

Should You Write Short?

I'm doing a series of Wednesday posts discussing my career decisions and the reasons behind them. Last week I talked about committing to indie publishing. Now I'll go into some specific details.

Decision #2: Write shorter books.

When I wrote

Rattled

, I was planning on submitting traditionally. I targeted 85,000 words, which is on the short end of what most publishers will accept for a genre novel. (The exception being Category Romance, where 60,000 words is standard.)

When I wrote

Rattled

, I was planning on submitting traditionally. I targeted 85,000 words, which is on the short end of what most publishers will accept for a genre novel. (The exception being Category Romance, where 60,000 words is standard.)Now that I'm focused on self-publishing, I'm targeting my books at 60,000 words. Here are the reasons I'm going shorter:

Shorter books are faster to write. When I'm working hard on a novel, I try to write 10,000 words per week (though it doesn't always happen, especially when I have too many paid jobs). Add in the extra editing time for a longer book, and 60,000 words saves me at least three weeks over an 85,000-word book. More books published equals more potential income. Writing shorter books may allow me to increase my output from three books per year to four. (Don't bother trying to make the math work – I have to take breaks in between the books to catch up on paid work, and then there's always delays due to illness, travel etc.)

Shorter books are cheaper to print. For print on demand, my total cost is dependent on the number of pages. It's not a huge difference, but Rattled has a minimum price of $9.68 (meaning I need to price the book higher than that to make any money on it in certain distribution channels). Whispers in the Dark has a minimum price of $8.65. Shorter books mean I make more profit per book on print on demand copies. (Or I could price them lower if I thought I would bring in more sales.) If I wrote an even longer book – say 110,000 words – I'd have to price it above $9.99, and once you go over that $10 threshold, sales should drop, if you believe that research on shopping behavior.

People like fat paperbacks because they take longer to read. It's the airport theory – If you're going to get on a plane for a long trip, you want a book that will last the whole trip. Plus, people feel like they're getting more for their money with a longer book. These visual cues disappear with digital copies. You don't want to make the book too short, because if people think they're buying a full-length novel and they get a novella, they can get angry – and take it out on you in their reviews. But the advantage to writing a very long book goes away.

What if you have a very long story to tell? Or what about genres such as adult fantasy, where incredibly long books are the norm? Even then, you may be better off splitting a long book into several shorter ones, releasing them individually, and then offering the complete trilogy at a discount over buying the three books separately. (For example, release each individual e-book at $3.99, and then release the complete trilogy in one book for $9.99.) With digital publishing, especially indie publishing, people don't like to pay high prices. They might not want to pay so much for a single title, but they'll feel like they are getting a deal with a discount for the set.

The last point I want to make is a bit more theoretical. I read some comments recently on how all the time we spend on the computer and digital devices is changing our reading patterns. People are more likely to skim over news stories or blog posts. We expect and like shorter sound bites.

It seems reasonable that this might translate into a preference for shorter books, especially in digital format. With a paperback, you always have the visual cue of how much story you have left. Digital readers may have a bar marking the percent of the story you've finished, but it doesn't seem quite the same. (And for myself, when I glance down and see that I've only read six percent, I sometimes get a sense of dismay that I'm only that far along, a feeling that never comes from getting through the first chapter of a paperback.)

As people get used to shorter online news stories, skimming through blog posts, reading Facebook updates and super-short Tweets, a long book might start to feel "too long" and therefore a bit slow and dull, whereas a short book may cater better to our restlessness.

So, those are my reasons for writing shorter. Any thoughts on my logic? What do your own reading experiences tell you? As a writer, do you have a preference?

I should note that given my background in writing for children, shorter books come more naturally to me. I would never cut out important story elements or great plot twists in order to come in shorter. It's more a matter of not searching for additional plot twists and subplots in order to lengthen a book. (See my post on Making Muscular Action! for advice on how I once nearly doubled the length of a manuscript.)

Published on January 25, 2012 04:00

January 20, 2012

How Do You Turn Your Idea into a Story?

People often ask writers, "Where do you find your ideas?" But for a writer, the more important question is, "What do I do with my idea?"

Sometimes, a writer has a great premise, an intriguing starting point—but nothing more. How do you recognize when you have just a premise, and when you have the makings of a full story? And more importantly, how do you get from one stage to the other?

What is a story?

If you have a "great idea," but can't seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story has four main parts: idea, complications, climax and resolution. You need all of them to make your story work.

The idea is the situation or premise. This should involve an interesting main character with a challenging problem or goal. Even this takes development. Maybe you have a great challenge, but aren't sure why a character would have that goal. Or maybe your situation is interesting, but doesn't actually involve a problem.

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can't. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can't. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

Tania feels sorry for the ghosts and wants to help them, while keeping her gift a secret from everyone but her brother. Jon wants to help and protect his sister, but sometimes feels overwhelmed by the responsibility.

Now we have two main characters with problems and goals. The story is off to a good start. (It became Haunted: The Ghost on the Stairs .)

Tip:

Make sure your idea is specific and narrow, especially with short stories or articles. Focus on an individual person and situation, not a universal concept. For example, don't try to write about "racism." Instead, write about one character facing racism in a particular situation.

Next week we'll talk about how to set up those complications through CONFLICT.

Sometimes, a writer has a great premise, an intriguing starting point—but nothing more. How do you recognize when you have just a premise, and when you have the makings of a full story? And more importantly, how do you get from one stage to the other?

What is a story?

If you have a "great idea," but can't seem to go anywhere with it, you probably have a premise rather than a complete story plan. A story has four main parts: idea, complications, climax and resolution. You need all of them to make your story work.

The idea is the situation or premise. This should involve an interesting main character with a challenging problem or goal. Even this takes development. Maybe you have a great challenge, but aren't sure why a character would have that goal. Or maybe your situation is interesting, but doesn't actually involve a problem.

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can't. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?

For example, I wanted to write about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show. The girl can see ghosts, but the boy can't. That gave me the characters and the situation, but no problem or goal. Goals come from need or desire. What did they want that could sustain an entire series?Tania feels sorry for the ghosts and wants to help them, while keeping her gift a secret from everyone but her brother. Jon wants to help and protect his sister, but sometimes feels overwhelmed by the responsibility.

Now we have two main characters with problems and goals. The story is off to a good start. (It became Haunted: The Ghost on the Stairs .)

Tip:

Make sure your idea is specific and narrow, especially with short stories or articles. Focus on an individual person and situation, not a universal concept. For example, don't try to write about "racism." Instead, write about one character facing racism in a particular situation.

Next week we'll talk about how to set up those complications through CONFLICT.

Published on January 20, 2012 04:00

January 18, 2012

Career Choices in Publishing

Somehow in the past few months I've gotten a reputation (at least in certain small circles) as a self-publishing expert. Which is pretty funny, because I've been doing this for less than a year and I'm learning as I go. But I've been willing to share what I'm learning, and I guess even my minimal experience puts me farther along the path that a lot of people who are in a "wait and see" pattern or still completely dismissive.

Since people seem to be curious about this journey, I thought I'd share some of the decisions I'm making now. I can't guarantee that these are the right decisions, but I'll explain the logic behind them. Maybe we can check back in a year and see how they look in hindsight. I'll be posting and explaining a decision each week, on Wednesdays.

On Fridays, I'll be reposting some of my craft articles. (Yes, for a while these will mainly be repeats, but craft doesn't change much, and even if you've heard it before, it often helps to hear it again.) So, on to the career decisions.

Decision #1: I've committed to self-publishing for my adult genre novels.

I first switched to writing romantic suspense thinking that I would submit traditionally. I'd hoped the market would be better than for middle grade novels. Adult novels aren't quite as influenced by market trends, since each genre and subgenre has devoted fans. And advances were supposed to be higher.

But the more I heard, about both traditional publishing for adult genre books and about self-publishing, the more I questioned that path.

With traditional publishing, it's harder than ever to sell a book, and advances are down. It can be easier to sell to a smaller, digital-only or digital-first publisher, but many of these offer no advances, only paying royalties. Genre publishing can have fairly strict guidelines for word count. With romance, each line even has different standards for how sexy they can be. Some imprints won't allow first-person narration or multiple viewpoints, or else require you use both the hero and heroine's viewpoint. You could spend a lot of effort targeting one publisher's imprint, and if they reject the book, it won't be suitable anywhere else. Authors can also find themselves trapped into writing a specific style determined more by their publisher than by their own tastes.

With traditional publishing, it's harder than ever to sell a book, and advances are down. It can be easier to sell to a smaller, digital-only or digital-first publisher, but many of these offer no advances, only paying royalties. Genre publishing can have fairly strict guidelines for word count. With romance, each line even has different standards for how sexy they can be. Some imprints won't allow first-person narration or multiple viewpoints, or else require you use both the hero and heroine's viewpoint. You could spend a lot of effort targeting one publisher's imprint, and if they reject the book, it won't be suitable anywhere else. Authors can also find themselves trapped into writing a specific style determined more by their publisher than by their own tastes.Traditional publishers can help with marketing, but you never know how much promotion you're going to get. It takes a couple of years to get a book published, which means you're not building name recognition yet. Many publishers are unwilling to experiment with pricing or free offers to increase sales. And if the book is suffering from a lousy cover or poor description, they are more likely to go on to something else than to make changes.

And worst of all, traditional publishers are offering increasingly worse contracts, trying to take more rights while holding down royalties. This will change – it has to change – but signing a contract now may mean you suffer financially for years.

Self-publishing has many challenges, but also a lot more flexibility and freedom. You can release books on your own schedule, starting to build name recognition and a least a few sales quickly. You may not sell large numbers, but you make a lot more per book. You can experiment as much as you want with different covers, descriptions, pricing, and promotions, seeing what works best.

And best of all, you retain all rights. Different formats, foreign translations, movie/TV rights – it's all yours. Granted, you're unlikely to ever sell most of those rights, but if you do, you won't have to split the income with a publisher. (Please note, some publishers aggressively sell subsidiary rights, which means you're more likely to see income from them. But some just sit on the rights and don't do anything with them until an outside company asks. In that case, they are taking a percentage for doing nothing.)

I waffled over my decision for a while. I even sent Rattled to my agent. An advance sure would be nice. But ultimately, I decided that I don't have time to wait months to hear back from publishers, when there's a good chance the answer will be "No." By publishing independently, I need to do a lot more work on promotion, and of course there's a learning curve just figuring out how to do all this stuff. But I'm not spending time researching publishers and agents or altering my work to fit specific guidelines.

I waffled over my decision for a while. I even sent Rattled to my agent. An advance sure would be nice. But ultimately, I decided that I don't have time to wait months to hear back from publishers, when there's a good chance the answer will be "No." By publishing independently, I need to do a lot more work on promotion, and of course there's a learning curve just figuring out how to do all this stuff. But I'm not spending time researching publishers and agents or altering my work to fit specific guidelines. My decision won't be right for everyone. Either way, it's a lot of work. Either way, it's a gamble. But now that I've started down this path, I'm determined to give it a great try. My goal is to get two more books published this year, and then to focus on promotion – but that's another decision. More on that in a future post.

Published on January 18, 2012 14:27