Chris Eboch's Blog, page 28

October 19, 2012

How to Write Vivid Scenes part 2

Last week I talked about how to write vivid scenes by focusing on action and dialogue (not summary) and by including conflict. Now let's explore how to link those scenes for the best dramatic impact.

Connecting Scenes

Each scene is a mini-story, with its own climax. Each scene should lead to the next and drive the story forward, so all scenes connect and ultimately drive toward the final story climax.

A work of fiction has one big story question—essentially, will this main character achieve his or her goal? For example, in my children’s historical fiction novel

The Eyes of Pharaoh

, the main character hunts for her missing friend. The story question is, “Will Seshta find Reya?” In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the story question is, “Will Eveningstar be able to save her city and herself from the evil high priest?”

A work of fiction has one big story question—essentially, will this main character achieve his or her goal? For example, in my children’s historical fiction novel

The Eyes of Pharaoh

, the main character hunts for her missing friend. The story question is, “Will Seshta find Reya?” In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the story question is, “Will Eveningstar be able to save her city and herself from the evil high priest?”In Rattled (written as Kris Bock), the big story question is, “Will Erin find the treasure before the bad guys do?” There may also be secondary questions, such as, “Will Erin find love with the sexy helicopter pilot?” but one main question drives the plot.

Throughout the work of fiction, the main character works toward that story goal during a series of scenes, each of which has a shorter-term scene goal. For example, in Erin’s attempt to find the treasure, she and her best friend Camie must get out to the desert without the bad guys following; they must find a petroglyph map; and they must locate the cave.

You should be able to express each scene goal as a clear, specific question, such as, “Will Erin and Camie get out of town without being followed?” If you can’t figure out your main character’s goal in a scene, you may have an unnecessary scene or a character who is behaving in an unnatural way.

Yes, No, Maybe

Scene questions can be answered in four ways: Yes, No, Yes but…, and No and furthermore….

If the answer is “Yes,” then the character has achieved his or her scene goal and you have a happy character. That’s fine if we already know that the character has more challenges ahead, but you should still end the chapter with the character looking toward the next goal, to maintain tension and reader interest. For example, in my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), one chapter ends when the heroine has successfully fought back against someone who was harassing her. But she realizes that the person is probably not the murderer, so a killer is still out there.

If the answer is “Yes,” then the character has achieved his or her scene goal and you have a happy character. That’s fine if we already know that the character has more challenges ahead, but you should still end the chapter with the character looking toward the next goal, to maintain tension and reader interest. For example, in my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), one chapter ends when the heroine has successfully fought back against someone who was harassing her. But she realizes that the person is probably not the murderer, so a killer is still out there.Truly happy scene endings usually don’t have much conflict, so save that for the last scene.

If the answer to the scene question is “No,” then the character has to try something else to achieve that goal. That provides conflict, but it’s essentially the same conflict you already had. Too many examples of the character trying and failing to achieve the same goal, with no change, will get dull.

An answer of “Yes, but…” provides a twist to increase tension. Maybe a character can get what she wants, but with strings attached. This forces the character to choose between two things important to her or to make a moral choice, a great source of conflict. Or maybe she achieves her goal but it turns out to make things worse or add new complications. For example, in Rattled , the bad guys show up in the desert while Erin and Camie are looking for the lost treasure cave. The scene question becomes, “Will Erin escape?” This is answered with, “Yes, but they’ve captured Camie,” which leads to a new set of problems.

“No, and furthermore…” is another strong option because it adds additional hurdles—time is running out or your character has a new obstacle. It makes the situation worse, which creates even greater conflict. In

Whispers in the Dark

(written as Kris Bock), one scene question is, “Will Kylie be able to notify the police in time to stop the criminals from escaping?” When this is answered with, “No, and furthermore they come back and capture her,” the stakes are increased dramatically.

“No, and furthermore…” is another strong option because it adds additional hurdles—time is running out or your character has a new obstacle. It makes the situation worse, which creates even greater conflict. In

Whispers in the Dark

(written as Kris Bock), one scene question is, “Will Kylie be able to notify the police in time to stop the criminals from escaping?” When this is answered with, “No, and furthermore they come back and capture her,” the stakes are increased dramatically.One way or another, the scene should end with a clear answer to the original question. Ideally that answer makes things worse. The next scene should open with a new specific scene goal (or occasionally the same one repeated) and probably a review of the main story goal. Here’s an example from The Eyes of Pharaoh :

Scene question: “Will Seshta find Reya at the army barracks?” Answer: “No, and furthermore, she thinks the general lied to her, so Reya may be in danger.” Next scene: “Can Seshta spy on the general to find out the truth, which may lead her to Reya?”

Scene question: “Will Seshta find Reya at the army barracks?” Answer: “No, and furthermore, she thinks the general lied to her, so Reya may be in danger.” Next scene: “Can Seshta spy on the general to find out the truth, which may lead her to Reya?”Over the course of a novel, each end-of-scene failure should get the main character into worse trouble, leading to a dramatic final struggle.

Next week: Using Cause and Effect

In Advanced Plotting , you’ll get two dozen essays like this one on the craft of writing, plus a detailed explanation of the Plot Outline Exercise, a powerful tool to identify and fix plot weaknesses in your manuscripts. Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

Published on October 19, 2012 04:00

October 17, 2012

Rebecca Dahlke on getting the word out

Today's guest post by Rebecca Dahlke addresses one of the great challenges in publishing, whether traditional or indie – getting the word out about your books. Here's Rebecca:

So I put the website in mothballs, but kept the Facebook site; the yahoo group (which is where authors meet to talk about promotion, and readers come to see what authors are talking about); the Goodreads group for Indie and small press promotion; and a Twitter account.

Since then I have put four mysteries up on Amazon/Kindle, and because I understood that my books are a product, I also began a six-month quest for the best, and most effective, form of advertising.

The results were exciting! I discovered that with a combination of inexpensive paid and free promotion, I could sell more books. I thought the results of this were interesting enough to share. I put together a 7 page handout and spoke on this subject with my local Sisters in Crime chapter in Tucson. The handout was necessary because I had a lot of powerful information to share, but also I cautioned my grateful listeners with the following: The only thing I could guarantee about this information was that some of it would change.

That was in June 2012, and sure enough, things did change. One of the sites I listed as smart and creative bit the dust, and another site, Digital Books Today, has taken a giant leap after only 18 months in the business. Eighteen months? Gee, All Mystery e-newsletter started before DBT… so that meant… but wait! There's more!

In a 2012 e-mail from the founder of Digital Books Today, Anthony Wessel says, and I quote: "Traffic on our Sites: March: 8,000, June 16,000" and in their "The Top 100 Best Free Kindle Books List: November 2011: 600+ and June 2012- 10,000+ with 38,000 click outs to books on Amazon."

Obviously authors had finally seen the light and were using paid book marketing as part of a successful campaign to sell books. I know, because I was using them too, and the results have been gratifying—except I had one complaint: As a mystery writer, all of the promotion sites had mystery squished in between vampire and memoir.

It didn't take me but a nano-second to see that All Mystery e-newsletter's time had finally come. I ticked off the obstacles for resurrecting this e-newsletter against the fact that it might take some time to gain momentum. Then realized I already had all of my requirements for a good promotion site: I still had my list of readers from last year's e-newsletter, and I had a Facebook page, Yahoo and Goodreads groups, and Twitter with a small army of Re-Tweet pals.

September 1st I sent out the first weekly e-newsletter accompanied with additional author posts at Facebook and Twitter that would continue throughout the week.

Sound interesting?

Here are links to All Mystery e-newsletter places:

http://allmysteryenewsletter.comhttp://www.facebook.com/allmysteryenewsletterhttp://groups.yahoo.com/group/allmysteryenewsletter/?yguid=185161871http://www.goodreads.com/group/show/42847.All_Mystery_e_newsletter Twitter handle: @allmysterynews

Last but not least, for those of you who would like a copy of that 7 page handout for both free and paid promotions for authors, send me an e-mail with "promotion handout" in the subject line and I'll send you a PDF copy. E-mail: rp@rpdahlke.com

Published on October 17, 2012 04:00

October 12, 2012

How to Write Vivid Scenes

Last week I shared a guest essay on keeping suspense in your writing. One of the basic building blocks of fiction is the scene, and a well-written scene can contribute to maintaining tension in the story.

In fiction writing, a scene is a single incident or event. However, a summary of the event is not a scene. Scenes are written out in detail, shown, not told, so we see, hear, and feel the action. They often have dialog, thoughts, feelings, and sensory description, as well as action.

A scene ends when that sequence of events is over. A story or novel is, almost always, built of multiple linked scenes. Usually the next scene jumps to a new time or place, and it may change the viewpoint character.

Think in terms of a play: The curtain rises on people in a specific situation. The action unfolds as characters move and speak. The curtain falls, usually at a dramatic moment. Repeat as necessary until you’ve told the whole story.

So how do you write a scene?

Place a character—usually your main character—in the scene.Give that character a problem.Add other characters to the scene as needed to create drama.Start when the action starts—don’t warm up on the reader’s time.What does your main character think, say, and do?What do the other characters do or say?How does your main character react?What happens next? Repeat the sequence of actions and reactions, escalating tension.Built to a dramatic climax.End the scene, ideally with conflict remaining. Give the reader some sense of what might happen next—the character’s next goal or challenge—to drive the plot forward toward the next scene. Don’t ramble on after the dramatic ending, and don’t end in the middle of nothing happening.

Scene endings may or may not coincide with chapter endings. Some authors like to use cliffhanger chapter endings in the middle of a scene and finish the scene at the start of the next chapter. They then use written transitions (later that night, a few days later, when he had finished, etc.) or an extra blank line to indicate a break between scenes within a chapter. (You'll find my essays on cliffhangers by clicking on the "cliffhanger" link in the list to the right.)

A scene can do several things, among them:

Advance the plot.Advance subplots.Reveal characters (their personalities and/or their motives).Set the scene.Share important information.Explore the theme.

Ideally, a scene will do multiple things. It may not be able to do everything listed above, but it should do two or three of those things, if possible. It should always, always, advance the plot. Try to avoid having any scene that only reveals character, sets the scene, or explores the theme, unless it’s a very short scene, less than a page. Find a way to do those things while also advancing the plot.

A scene often includes a range of emotions as a character works towards a goal, suffers setbacks, and ultimately succeeds or fails. But some scenes may have one mood predominate. In that case, try to follow with a scene that has a different mood. Follow an action scene with a romantic interlude, a happy scene with a sad or frightening one, a tense scene with a more relaxed one to give the reader a break.

Don’t rush through a scene—use more description in scenes with the most drama, to increase tension by making the reader wait a bit to find out what happens. Important and dramatic events should be written out in detail, but occasionally you may want to briefly summarize in order to move the story forward. For example, if we already know what happened, we don’t need to hear one character telling another what happened. Avoid that repetition by simply telling us that character A explained the situation to character B.

Avoid scenes that repeat previous scenes, showing another example of the same action or information. Your readers are smart enough to get things without being hit over the head with multiple examples. If you show one scene of a drunk threatening his wife, and you do it well, we’ll get it. We don’t need to see five examples of the same thing. Focus on writing one fantastic scene and trust your reader to understand the characters and their relationship. For every scene, ask: Is this vital for my plot or characters? How does it advance plot and reveal character? If I cut the scene, would I lose anything?

See also Seven Essential Elements of Scene + Scene Structure Exercise by Martha Alderson from Jane Friedman. '

Next week: Connecting Scenes

Advanced Plotting is designed for the intermediate and advanced writer: you’ve finished a few stories, read books and articles on writing, taken some classes, attended conferences. But you still struggle with plot, or suspect that your plotting needs work.Advanced Plotting can help.Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

Published on October 12, 2012 04:00

October 5, 2012

On the Edge of Your Seat: Creating Suspense, by Sophie Masson

Part of keeping your reader’s attention throughout your novel is creating suspense, regardless of your novel’s genre. Here’s an excerpt from an essay in

Advanced Plotting

by guest author Sophie Masson:

On the Edge of Your Seat: Creating Suspense

Suspense is what keeps a reader reading—wanting to know what happens. The suspense can be of all kinds, from wanting to know who the baddie is in a thriller to wanting to know whether the heroine is going to choose Mr. A or Mr. B as her love interest, to—well, just about anything, really! Creating and maintaining suspense is important in any kind of story or novel; it is especially so in the kinds of genres that are built around suspense: mysteries, thrillers, spy stories, fantasy. Here are some of my tips, honed over years of writing in many of those genres!

First of all, to create suspense you need:

Some background information.But incomplete knowledge.

That is, from the beginning the author needs to already have something set up—to let the reader know something about a character and their situation, or the suspense won’t happen—you have to care what happens for suspense to occur in the reader’s mind.

You can build towards that or start immediately with a suspenseful mysterious beginning, but there must not be too many clues as to what might happen or the suspense will fizzle out before it’s had a chance to happen. You need instead to build up the tension carefully, making the reader think that something is one way when it’s another. But at the same time you can’t play dirty tricks on them—you shouldn’t for instance at the climax suddenly produce a character that wasn’t there before—either in person or mentioned—as the villain, or the reader has a right to feel ripped off.

In my detective novel The Case of the Diamond Shadow, for instance, the true villain is hidden behind a smokescreen of red herrings—but is there all along. It’s just that nobody even thinks of them in connection with the crime!

Character is very important in suspense. I think that plot itself, the driving machine of a story, is really at heart the unfolding of interaction between characters, good and bad. That is what creates situations and fuels tension. So you need to feel strongly for your characters especially the one or ones from whose point of view the action is viewed from, but also the others with whom they interact. If the characters feel real to your readers, then they will see when someone is acting out of character—and that will immediately set up suspense. Or say your main character trusts someone—really trusts them—and little by little they begin to change their minds, to suspect they’re up to no good—excellent suspense too.

Sophie Masson has published more than 50 novels internationally since 1990, mainly for children and young adults. A bilingual French and English speaker, raised mostly in Australia, she has a master’s degree in French and English literature. Her most recent novel to be published in the USA, The Madman of Venice (Random House), was written for middle school children, grades ~6-10 and her recent historical novel, The Hunt for Ned Kelly (Scholastic Australia) won the prestigious Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature in the 2011 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. www.sophiemasson.org

Sophie Masson has published more than 50 novels internationally since 1990, mainly for children and young adults. A bilingual French and English speaker, raised mostly in Australia, she has a master’s degree in French and English literature. Her most recent novel to be published in the USA, The Madman of Venice (Random House), was written for middle school children, grades ~6-10 and her recent historical novel, The Hunt for Ned Kelly (Scholastic Australia) won the prestigious Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature in the 2011 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. www.sophiemasson.org

See the complete essay and two dozen more in Advanced Plotting, plus a detailed explanation of the Plot Outline Exercise, a powerful tool to identify and fix plot weaknesses in your manuscripts. Buy Advanced Plotting for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

On the Edge of Your Seat: Creating Suspense

Suspense is what keeps a reader reading—wanting to know what happens. The suspense can be of all kinds, from wanting to know who the baddie is in a thriller to wanting to know whether the heroine is going to choose Mr. A or Mr. B as her love interest, to—well, just about anything, really! Creating and maintaining suspense is important in any kind of story or novel; it is especially so in the kinds of genres that are built around suspense: mysteries, thrillers, spy stories, fantasy. Here are some of my tips, honed over years of writing in many of those genres!

First of all, to create suspense you need:

Some background information.But incomplete knowledge.

That is, from the beginning the author needs to already have something set up—to let the reader know something about a character and their situation, or the suspense won’t happen—you have to care what happens for suspense to occur in the reader’s mind.

You can build towards that or start immediately with a suspenseful mysterious beginning, but there must not be too many clues as to what might happen or the suspense will fizzle out before it’s had a chance to happen. You need instead to build up the tension carefully, making the reader think that something is one way when it’s another. But at the same time you can’t play dirty tricks on them—you shouldn’t for instance at the climax suddenly produce a character that wasn’t there before—either in person or mentioned—as the villain, or the reader has a right to feel ripped off.

In my detective novel The Case of the Diamond Shadow, for instance, the true villain is hidden behind a smokescreen of red herrings—but is there all along. It’s just that nobody even thinks of them in connection with the crime!

Character is very important in suspense. I think that plot itself, the driving machine of a story, is really at heart the unfolding of interaction between characters, good and bad. That is what creates situations and fuels tension. So you need to feel strongly for your characters especially the one or ones from whose point of view the action is viewed from, but also the others with whom they interact. If the characters feel real to your readers, then they will see when someone is acting out of character—and that will immediately set up suspense. Or say your main character trusts someone—really trusts them—and little by little they begin to change their minds, to suspect they’re up to no good—excellent suspense too.

Sophie Masson has published more than 50 novels internationally since 1990, mainly for children and young adults. A bilingual French and English speaker, raised mostly in Australia, she has a master’s degree in French and English literature. Her most recent novel to be published in the USA, The Madman of Venice (Random House), was written for middle school children, grades ~6-10 and her recent historical novel, The Hunt for Ned Kelly (Scholastic Australia) won the prestigious Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature in the 2011 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. www.sophiemasson.org

Sophie Masson has published more than 50 novels internationally since 1990, mainly for children and young adults. A bilingual French and English speaker, raised mostly in Australia, she has a master’s degree in French and English literature. Her most recent novel to be published in the USA, The Madman of Venice (Random House), was written for middle school children, grades ~6-10 and her recent historical novel, The Hunt for Ned Kelly (Scholastic Australia) won the prestigious Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature in the 2011 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. www.sophiemasson.orgSee the complete essay and two dozen more in Advanced Plotting, plus a detailed explanation of the Plot Outline Exercise, a powerful tool to identify and fix plot weaknesses in your manuscripts. Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

Published on October 05, 2012 04:00

October 3, 2012

Writing the Male Point of View, with Chris Redding

Today's guest is romantic suspense author Chris Redding. In any of the romance subgenres, male-female relationships are important. But creating realistic male characters is important for all forms of writing. (I've heard editors and agents say that children's or teen books written by women often have unrealistic boy characters.) Here's Chris to explore communication differences between men and women:

This is an excerpt from my lecture on Communication in my workshop: Show Up Naked: Writing the Male Point of View.

Men are lecturers. They are used to giving out information and expecting people (especially women) to listen to what they have to say. Ever been with a guy who just went on and on? He has no idea that you lost interest about five minutes ago. He’s lecturing. He assumes that because you are quiet that you are interested. Imagine your hero begin to do this and your strong heroine getting up in his face about it. Conflict! Often, even if the woman adds something to the conversation, the man does not pick up on those facts. He will keep going on his own track of the conversation. These situations can start out on an even keel, but then the man takes over. This (and I hate to keep harping on this) is because it puts them at a higher status. They are the information giver. They have something that the other person supposedly wants. Women, in seeking rapport, tend to downplay their expertise. Men are quite willing to take center stage. But a strong heroine, especially one in a dangerous situation is less likely to worry about rapport. She’s worried about getting out of the situation. She isn’t going to fall back on creating connections. She wants to create an escape. I teach CPR and I find this with a lot of the male instructors. They automatically take over or become lead instructor. And I’m a pretty strong personality so they don’t really get away with it. Deborah Tannen in You Just Don’t Understand talks about how different conversations are with men and women in terms of what she does for living. Specifically she talks about social functions.

Men are lecturers. They are used to giving out information and expecting people (especially women) to listen to what they have to say. Ever been with a guy who just went on and on? He has no idea that you lost interest about five minutes ago. He’s lecturing. He assumes that because you are quiet that you are interested. Imagine your hero begin to do this and your strong heroine getting up in his face about it. Conflict! Often, even if the woman adds something to the conversation, the man does not pick up on those facts. He will keep going on his own track of the conversation. These situations can start out on an even keel, but then the man takes over. This (and I hate to keep harping on this) is because it puts them at a higher status. They are the information giver. They have something that the other person supposedly wants. Women, in seeking rapport, tend to downplay their expertise. Men are quite willing to take center stage. But a strong heroine, especially one in a dangerous situation is less likely to worry about rapport. She’s worried about getting out of the situation. She isn’t going to fall back on creating connections. She wants to create an escape. I teach CPR and I find this with a lot of the male instructors. They automatically take over or become lead instructor. And I’m a pretty strong personality so they don’t really get away with it. Deborah Tannen in You Just Don’t Understand talks about how different conversations are with men and women in terms of what she does for living. Specifically she talks about social functions.

My experience is that if I mention the kind of work I do to women, they usually ask me about it. When I tell them abut conversational style or gender differences, they offer their own experiences to support the patterns I describe. But when I announce my line of work to men, many give me a lecture on language – for example, about how people, especially teenagers, misuse language nowadays. Others challenge me, for example questioning me about my research methods. Many others change the subject to something they know more about.

Psychologist H. M. Leet-Pellegrini wanted to discover which was more important to determining who would act in a “dominant” manner, those of a certain gender or those who have expertise in a subject. She set up pairs to discuss TV violence’s affect on children. The pairs were either two men, two women or one of each. In some cases, one of the partners was an expert on the subject. The experts definitely talked more, but the male experts talked more than the female experts. Non-expert women gave more support to their partners regardless of whether that partner was an expert or not. Men who were not experts on the subject were less likely to give support to the women who were the expert. In fact even if a woman was an expert she tended to give supportive statements to the non-expert man. When an expert man talked to a non-expert woman, he tended to control the conversation, though if he was talking to another man, expert or not, he was less likely to control the ending of the conversation. In other words, when a man has expertise he isn’t challenged about it by a woman, but will be by a man. It all goes back to jockeying for status. To do that the man must challenge the authority.

Chris Redding lives in New Jersey with her husband, two kids, one dog and three rabbits. She graduated from Penn State with a degree in Journalism. When not writing she works for her local hospital in the Emergency Services Department. She has been writing for thirteen years and has five books published.

What if your past comes back to haunt you?

What if your past comes back to haunt you?

Chelsea James, captain of the Biggin Hill First Aid Squad, has had ten years to mend a broken heart and forget about the man who’d left her hurt and bewildered. Ten years to get her life on track. But fate has other plans.

Fire Inspector Jake Campbell, back in town after a decade, investigates a string of arsons, only to discover they are connected to the same arsons he’d been accused of long ago. Now his past has come back to haunt him, and Chelsea is part of that past.

Together, Chelsea and Jake must join forces to defeat their mutual enemy. Only then can they hope to rekindle the flames of passion. But before they can do that, Chelsea must learn to trust again. Their lives could depend on it.

www.chrisreddingauthor.comwww.facebook.com/chrisreddingauthorwww.twitter.com/chrisredding

This is an excerpt from my lecture on Communication in my workshop: Show Up Naked: Writing the Male Point of View.

Men are lecturers. They are used to giving out information and expecting people (especially women) to listen to what they have to say. Ever been with a guy who just went on and on? He has no idea that you lost interest about five minutes ago. He’s lecturing. He assumes that because you are quiet that you are interested. Imagine your hero begin to do this and your strong heroine getting up in his face about it. Conflict! Often, even if the woman adds something to the conversation, the man does not pick up on those facts. He will keep going on his own track of the conversation. These situations can start out on an even keel, but then the man takes over. This (and I hate to keep harping on this) is because it puts them at a higher status. They are the information giver. They have something that the other person supposedly wants. Women, in seeking rapport, tend to downplay their expertise. Men are quite willing to take center stage. But a strong heroine, especially one in a dangerous situation is less likely to worry about rapport. She’s worried about getting out of the situation. She isn’t going to fall back on creating connections. She wants to create an escape. I teach CPR and I find this with a lot of the male instructors. They automatically take over or become lead instructor. And I’m a pretty strong personality so they don’t really get away with it. Deborah Tannen in You Just Don’t Understand talks about how different conversations are with men and women in terms of what she does for living. Specifically she talks about social functions.

Men are lecturers. They are used to giving out information and expecting people (especially women) to listen to what they have to say. Ever been with a guy who just went on and on? He has no idea that you lost interest about five minutes ago. He’s lecturing. He assumes that because you are quiet that you are interested. Imagine your hero begin to do this and your strong heroine getting up in his face about it. Conflict! Often, even if the woman adds something to the conversation, the man does not pick up on those facts. He will keep going on his own track of the conversation. These situations can start out on an even keel, but then the man takes over. This (and I hate to keep harping on this) is because it puts them at a higher status. They are the information giver. They have something that the other person supposedly wants. Women, in seeking rapport, tend to downplay their expertise. Men are quite willing to take center stage. But a strong heroine, especially one in a dangerous situation is less likely to worry about rapport. She’s worried about getting out of the situation. She isn’t going to fall back on creating connections. She wants to create an escape. I teach CPR and I find this with a lot of the male instructors. They automatically take over or become lead instructor. And I’m a pretty strong personality so they don’t really get away with it. Deborah Tannen in You Just Don’t Understand talks about how different conversations are with men and women in terms of what she does for living. Specifically she talks about social functions.My experience is that if I mention the kind of work I do to women, they usually ask me about it. When I tell them abut conversational style or gender differences, they offer their own experiences to support the patterns I describe. But when I announce my line of work to men, many give me a lecture on language – for example, about how people, especially teenagers, misuse language nowadays. Others challenge me, for example questioning me about my research methods. Many others change the subject to something they know more about.

Psychologist H. M. Leet-Pellegrini wanted to discover which was more important to determining who would act in a “dominant” manner, those of a certain gender or those who have expertise in a subject. She set up pairs to discuss TV violence’s affect on children. The pairs were either two men, two women or one of each. In some cases, one of the partners was an expert on the subject. The experts definitely talked more, but the male experts talked more than the female experts. Non-expert women gave more support to their partners regardless of whether that partner was an expert or not. Men who were not experts on the subject were less likely to give support to the women who were the expert. In fact even if a woman was an expert she tended to give supportive statements to the non-expert man. When an expert man talked to a non-expert woman, he tended to control the conversation, though if he was talking to another man, expert or not, he was less likely to control the ending of the conversation. In other words, when a man has expertise he isn’t challenged about it by a woman, but will be by a man. It all goes back to jockeying for status. To do that the man must challenge the authority.

Chris Redding lives in New Jersey with her husband, two kids, one dog and three rabbits. She graduated from Penn State with a degree in Journalism. When not writing she works for her local hospital in the Emergency Services Department. She has been writing for thirteen years and has five books published.

What if your past comes back to haunt you?

What if your past comes back to haunt you?Chelsea James, captain of the Biggin Hill First Aid Squad, has had ten years to mend a broken heart and forget about the man who’d left her hurt and bewildered. Ten years to get her life on track. But fate has other plans.

Fire Inspector Jake Campbell, back in town after a decade, investigates a string of arsons, only to discover they are connected to the same arsons he’d been accused of long ago. Now his past has come back to haunt him, and Chelsea is part of that past.

Together, Chelsea and Jake must join forces to defeat their mutual enemy. Only then can they hope to rekindle the flames of passion. But before they can do that, Chelsea must learn to trust again. Their lives could depend on it.

www.chrisreddingauthor.comwww.facebook.com/chrisreddingauthorwww.twitter.com/chrisredding

Published on October 03, 2012 04:00

September 28, 2012

Is Your Villain Evil Enough?

In previous posts, I've touched on using villains to add drama to your story. Let’s look at this more closely.

Use Your Villain

On the surface, this may sound obvious. The whole point of a villain is to make your hero’s life difficult, right? But I’ve found that it’s sometimes easy to forget about the villain when you’re focused on the hero’s actions. The villain sets something in motion and then disappears.

If you get stuck in your writing and can’t figure out what happens next, try checking in with your villain. Is he just sitting around, waiting for your hero to act? No! He should be actively trying to thwart your hero, plotting new complications and distractions. Realizing this can be the push you need to get past a slow spot.

I found this helpful for my middle grade historical mystery,

The Eyes of Pharaoh

. The heroine, Seshta, had done everything she could to track down her missing friend. While hunting for him, she had tipped off the bad guy. When I realized that would mean the villain was actively plotting against her, I had the inspiration for several big action scenes leading to the dramatic climax.

I found this helpful for my middle grade historical mystery,

The Eyes of Pharaoh

. The heroine, Seshta, had done everything she could to track down her missing friend. While hunting for him, she had tipped off the bad guy. When I realized that would mean the villain was actively plotting against her, I had the inspiration for several big action scenes leading to the dramatic climax.Not every book has an actual villain, of course. But if you don’t have one, consider adding one. Even if it’s not necessary for the main plot, a villain could add drama as a subplot.

Example: In the Haunted series, each book’s main plot involves Jon and Tania trying to help the ghosts. In book one, I created a minor secondary character, a fake psychic who calls herself Madam Natasha. In The Riverboat Phantom , Madam Natasha figures out that Tania can see ghosts – something Tania desperately wants to keep secret. Madam Natasha uses the secret as a threat, as she demands that the kids share information about the ghosts and give her credit for helping them. In The Knight in the Shadows , the kids go to war with Madam Natasha, determined to expose her as a fraud. This is still secondary to trying to help the ghost, but it adds challenges and emotional drama.

Whether your villain is involved in the main plot or a subplot, he or she doesn’t have to be a diabolical evil genius. He can be a bully at school, a competitor on a sports team, a nasty boss, or even a manipulative sibling or friend. Whatever the “villain” is, his job is to make your hero’s life miserable.

Exercise: look over your work in progress. Do you have a major villain? If so, is the villain as active as possible, aggressively trying to stop, hurt, or kill your hero?

Do you have secondary characters with villainous tendencies? Can you enhance these, so they cause even more trouble?

If you have no villain at all, brainstorm ways to add one.

Published on September 28, 2012 14:46

September 26, 2012

Publicity: A Reader's View

I’ve been using my Wednesday posts to talk about marketing tactics, which are especially valuable for authors who are trying to self publish, but are useful for everyone trying to sell books. Today I want to talk about book descriptions – the text that is used on book jackets, websites, and sales sites like Amazon or B&N.

A small press recently had a giveaway of mystery novels, so I was browsing through their books. But I struggled to decide which ones I was most likely to enjoy. The factor missing? The tone of the book. Was it humorous? Cute/sweet? Gritty and gruesome? Sometimes I could guess from the description – serial killers are more likely to be gritty, while a crafty female heroine suggests something lighter. But sometimes I couldn’t tell at all. And if I wasn’t sure, I was less likely to pick up the book – even though they were free.

If you are writing a book description, whether for a query letter or for promotion, think about identifying the tone of your story. If it’s not clear from the description, say straight-out that this is, for example, "a witty, sophisticated romance" or "a gritty, thought-provoking thriller. I like to see this at the beginning, before the plot description, as often knowing the tone colors how I interpret the rest of the description. (On a side note, be careful about praising yourself. It’s one thing to say the book is “humorous” – that tells me it’s meant to be funny. But if you say it’s “hilarious,” it sounds like you are bragging and I’m going to be suspicious of your judgment.)

Here’s another thing I, as a reader, would like. When deciding which book to read next on my Kindle, I have only the title and author name to guide me, or maybe a cover if they included it inside the book. (The Kindle Fire shows the covers in your library list, but the plain Kindle does not. You only see the cover if it’s included with the text of the book, and then only when you click to “open” the book.)

I have started using categories to organize the titles, but I’d still like to know something about the book when deciding what to read next. I have a printed list of notes I keep with my Kindle, but it would be nice if every book included the book’s description on the opening page of the electronic version – essentially the back blurb, but at the very front. Then I could quickly check the description to figure out what I feel like reading next.

There’s a danger in assuming that all other readers are like us. Some people love e-readers, some hate them. Some people read reviews carefully, others don’t even glance at them. Some people think cheap books must be bad, while others won’t pay more than $3 for an e-book. It’s important to take differences like these into account. That said, it’s also helpful to consider your own experiences as a reader, and what you’d like to see, when deciding how to write, publish, and promote your books.

Published on September 26, 2012 04:00

September 21, 2012

Developing Your Novel: Putting Secondary Characters First

I've been talking about developing a story. Sometimes when planning a novel, we focus exclusively on the main character. But secondary characters are important for fleshing out the story world.

Every novel – and most short stories and picture books – will have secondary characters. In general, the longer the book, the more secondary characters you can fit. These can be family members, friends, teachers or bosses, aliens, mythical characters, or even pets. Some will be nice. Some will be annoying. Ideally, one or more should be trouble.

I’m not talking about villains here (I'll do that next week). But even well-meaning secondary characters can make your main character’s life more complicated. When writing for children, parents are a natural for this role. They may simply want what they see as best for their child – but if that is opposed to what the child wants, it adds complications. These could be strong enough to form the main plot, or could simply be additional challenges the child has to face.

Example: In the Haunted series, Tania doesn’t want anyone to know that she can see ghosts. She’s afraid that her mother would want her to contact her dead little sister, and she doesn’t know how. Her stepfather would want to use her on his ghost hunter TV show, and people would think she was nuts. And her father doesn’t believe in ghosts, so he might think she was lying to get attention. Well-meaning family members with their own agendas make her desperate to keep her “gift” a secret.

Other examples of conflicting desires may be a dad who wants his son to play football, while the son wants to join the band, or parents who don’t want their daughter to date yet, when she’s fallen in love. A parent may be even a greater challenge, if he or she is an alcoholic, seriously ill, or depressed. Then, of course, there’s the issue of a divorced or widowed parent dating!

Even in adult novels, a parent may add pressure. In a romance, Mom may want the heroine to marry and provide grandchildren, nagging her to settle for the wrong man. Bosses can also add challenges, whether by pressuring the main character to do something illegal for the company or simply demanding long work hours which distract from other goals. In my new novel What We Found (written as Kris Bock), the 22-year-old heroine has allies and enemies both at work and at home.

Don’t forget friends, either! Friends can give bad advice, have their own agenda, use the main character for popularity or access to something or someone, or even secretly be trying to steal the main character’s love interest/job/position in society.

That’s not to say all friends have to be sneaky betrayers. Even the best of friends might distract the main character with their own emotional problems. In the teen romantic comedy My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters, by Sydney Salter, the heroine’s main goal is to save enough money from her summer job to get a nose job, so she can find a boyfriend. Her two best friends have their own problems with boys and jobs. In one scene, the main character is late to work, jeopardizing her job, because she’s been trying to protect a friend who had too much to drink.

Exercise: go through your work in progress and list every secondary character who has a role beyond a few lines. Make a few notes on each one – what is their basic personality and role in the story? What do they want?

Then, for each secondary character, ask:

• Could I develop this character more, to make him or her more complicated?• How could this secondary character be causing problems for my main character?• If the character is already causing problems, could they be even worse?

If you don’t have many secondary characters, consider adding some. What kind of character could add complications and drama? Make sure any new secondary characters fit smoothly into the plot, and don’t feel like they are just shoved in to cause trouble.

Check out my latest romantic suspense, written under the name Kris Bock!

Check out my latest romantic suspense, written under the name Kris Bock!What We Found : When Audra stumbles on a murdered woman in the woods, more than one person isn't happy about her bringing the crime to light. She’ll have to stand up for herself in order to stand up for the murder victim. It’s a risk, and so is reaching out to the mysterious young man who works with deadly birds of prey. But with danger all around, some risks are worth taking.

Published on September 21, 2012 04:00

September 19, 2012

Tips for Writing for Content Websites, with Christine Rice

Today's guest is Christine Rice, the author of Freelance Writing Guide: What to Expect in Your First Year as a Freelance Writer. Here's Christine:

Content websites are a platform for freelance writers to publish articles that inform readers and poems that entertain readers, while earning income for upfront payments, page views, or ad clicks and building a portfolio of published clips.

If you haven’t tried this type of writing before, the following tips will help guide you to: select a content website, format your writing for online publication, and be successful as a freelance writer.

Do your researchDon’t jump into joining a website before you’ve researched all of the websites. You will probably need to do several Web searches. This article, which has a list of ten websites that pay upfront for your articles and five content revenue sharing websites, will get you started. Check out each website that you come across in your searches thoroughly by reading the pages that have information about the company, articles from the writers of the website, and details about the website’s memberships.

Pick one or two websites to joinDon’t join every website you look into, because it will be overwhelming if you have too many websites to write for. It’s best to concentrate your efforts on one or two websites at a time. If they don’t end up working well for you, you can try other ones.

Pick one or two websites to joinDon’t join every website you look into, because it will be overwhelming if you have too many websites to write for. It’s best to concentrate your efforts on one or two websites at a time. If they don’t end up working well for you, you can try other ones.

Browse the website thoroughlyOnce you are a member of a content website, you should take a couple of days to browse the website as a member to get familiar with the layout and its features. You should read the FAQs, visit the forum and introduce yourself, and learn the website’s setup so that you no longer feel disorientated.

Choose the highest paying opportunities that are most fitting for youFrom browsing the website you should have learned where you can select the writing assignments. For some of the websites, you may have discovered that there is more than one way you can earn money from your writing on a single website. Choose the opportunities and assignments that are most fitting for you as a writer and that have the highest pay, because the articles will be the easiest and most rewarding to write.

Format your articles like print magazine articlesIf you haven’t noticed, print magazine articles have lots of small “block” paragraphs (no indentation and a space between each paragraph), bullet points and lists, and subtitles that stand out. The reason for all of this is to make the articles easy and enjoyable to read. That is how you should format your articles for content websites. Make sure to also check the website’s writing guidelines, because each website has slightly different guidelines.

Write as many quality articles as often as possibleWriting quality articles should be your first goal. Your second goal should be to create as many articles as possible. A lot of quality articles will turn out to be an impressive portfolio and will earn you the most money on the content websites.

Share your articles on your social networking websitesAfter you publish an article, you should share it everywhere. Post the direct link to the article on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, writing communities, and your website. Share the link only, because, since the article is published, you will not be able to publish the article itself elsewhere, depending on the terms and conditions of the website. Then, write more articles as you watch the page views of your articles increasing and the money adding up.

Now that you’ve received some inside tips on writing for content websites, go online and find some to write for. Or, if you’re already a member of one, start writing. Good luck!

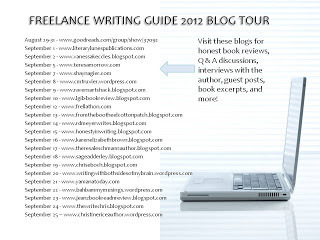

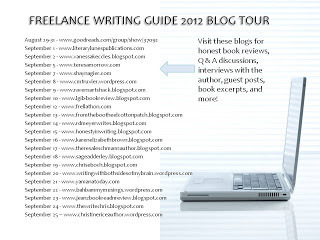

Christine Rice is the author of Freelance Writing Guide: What to Expect in Your First Year as a Freelance Writer . If you enjoyed this article, check out her book, which has additional information about writing for content websites, many more freelance writing tips, and other topics that are important for new freelance writers to know. Her book can be found at Amazon, Lulu, Smashwords, and other online retailers. You can learn more about Christine on her blog, Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Christine is on a blog tour this month. To see the other sites she'll be visiting, click on the image below.

Content websites are a platform for freelance writers to publish articles that inform readers and poems that entertain readers, while earning income for upfront payments, page views, or ad clicks and building a portfolio of published clips.

If you haven’t tried this type of writing before, the following tips will help guide you to: select a content website, format your writing for online publication, and be successful as a freelance writer.

Do your researchDon’t jump into joining a website before you’ve researched all of the websites. You will probably need to do several Web searches. This article, which has a list of ten websites that pay upfront for your articles and five content revenue sharing websites, will get you started. Check out each website that you come across in your searches thoroughly by reading the pages that have information about the company, articles from the writers of the website, and details about the website’s memberships.

Pick one or two websites to joinDon’t join every website you look into, because it will be overwhelming if you have too many websites to write for. It’s best to concentrate your efforts on one or two websites at a time. If they don’t end up working well for you, you can try other ones.

Pick one or two websites to joinDon’t join every website you look into, because it will be overwhelming if you have too many websites to write for. It’s best to concentrate your efforts on one or two websites at a time. If they don’t end up working well for you, you can try other ones.Browse the website thoroughlyOnce you are a member of a content website, you should take a couple of days to browse the website as a member to get familiar with the layout and its features. You should read the FAQs, visit the forum and introduce yourself, and learn the website’s setup so that you no longer feel disorientated.

Choose the highest paying opportunities that are most fitting for youFrom browsing the website you should have learned where you can select the writing assignments. For some of the websites, you may have discovered that there is more than one way you can earn money from your writing on a single website. Choose the opportunities and assignments that are most fitting for you as a writer and that have the highest pay, because the articles will be the easiest and most rewarding to write.

Format your articles like print magazine articlesIf you haven’t noticed, print magazine articles have lots of small “block” paragraphs (no indentation and a space between each paragraph), bullet points and lists, and subtitles that stand out. The reason for all of this is to make the articles easy and enjoyable to read. That is how you should format your articles for content websites. Make sure to also check the website’s writing guidelines, because each website has slightly different guidelines.

Write as many quality articles as often as possibleWriting quality articles should be your first goal. Your second goal should be to create as many articles as possible. A lot of quality articles will turn out to be an impressive portfolio and will earn you the most money on the content websites.

Share your articles on your social networking websitesAfter you publish an article, you should share it everywhere. Post the direct link to the article on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, writing communities, and your website. Share the link only, because, since the article is published, you will not be able to publish the article itself elsewhere, depending on the terms and conditions of the website. Then, write more articles as you watch the page views of your articles increasing and the money adding up.

Now that you’ve received some inside tips on writing for content websites, go online and find some to write for. Or, if you’re already a member of one, start writing. Good luck!

Christine Rice is the author of Freelance Writing Guide: What to Expect in Your First Year as a Freelance Writer . If you enjoyed this article, check out her book, which has additional information about writing for content websites, many more freelance writing tips, and other topics that are important for new freelance writers to know. Her book can be found at Amazon, Lulu, Smashwords, and other online retailers. You can learn more about Christine on her blog, Facebook, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Christine is on a blog tour this month. To see the other sites she'll be visiting, click on the image below.

Published on September 19, 2012 04:00

September 14, 2012

The Unity of Character and Plot, by Andrea J. Wenger

For my Friday craft posts, I've been talking about developing your novel. Let's explore building a strong middle in your novel by considering your characters. To start, I'm reposting this guest post by Andrea J. Wenger, who contributed an essay to my writing book, Advanced Plotting .

The Unity of Character and Plot

Several years ago, at the North Carolina Writers Network conference, I attended a session where the instructor claimed that character is plot. While I understand her point, I think she went too far. Many things happen in our lives that we can’t control. In fiction, the response to external events demonstrates character and propels plot. But generally, by the end of the story, the protagonist becomes proactive instead of responsive, and the protagonist’s positive action creates the climax.

Character and plot must work in harmony. For the story to be believable, the actions the character takes must be consistent with the character you’ve created. For instance, imagine if two of Shakespeare’s great tragic figures, Hamlet and Othello, were the protagonist in each other’s stories. How would those plays go?

Act I, Scene 1: The ghost of the old king tells Othello to avenge the old king’s death by killing Claudius.

Act I, Scene 2: Othello kills Claudius.

The End

No story, right? And if Iago hinted to Hamlet that Desdemona were cheating on him, Hamlet would answer, “You cannot play upon me.”

For the two plays to work, Othello’s hero must be action-oriented, while Hamlet’s hero must be introspective.

Keep in mind, though, that when under extreme stress, people (and characters) behave in ways they never would otherwise. In Writing the Breakout Novel , Donald Maass advises novelists to imagine something their character would never think, say, or do—then create a situation where the character thinks, says, or does exactly that. If it’s critical to your story that your character behave in uncharacteristic ways, put that character in an environment of increasing stress, until the point that the character’s “shadow” takes over.

Isabel Myers, co-author of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, defined the shadow function as the least developed part of our personality. Even in the best of times, we may have difficulty using this function in a rational and mature manner. When someone is under stress, and the shadow takes charge, the results can be disastrous.

In your own stories, do character and plot work in harmony? If a character behaves in an uncharacteristic way, be sure to show that the character is under enough stress to make the action believable.

Andrea J. Wenger is professional writer specializing in technical, freelance, and creative writing. Her short fiction has appeared in The Rambler. She is currently working on a women’s fiction novel. She blogs and speaks on the subject of writing and personality. She is a regular contributor to Carolina Communiqué, a publication of the Carolina Chapter of the Society for Technical Communication. www.WriteWithPersonality.com.

Get more essay like this one in Advanced Plotting, along with a detailed explanation of the Plot Outline Exercise, a powerful tool to identify and fix plot weaknesses in your manuscripts. Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

Published on September 14, 2012 04:00