Chris Eboch's Blog, page 27

December 12, 2012

On Becoming a Writer: My Path to Publication

I'm on a listserv for mystery fans, and we recently had a discussion on paths to publication. I wrote up my eexperience, so I thought I'd share it here. People often don't know what they're getting into when they decide to "become a writer," and no one outside of the business has a clue how challenging it is. Here's just one example. [Note – many, many people on the list didn't start writing until they were in their 40s, 50s, 60s or 70s, and many also took 20 or more years to get published.]

My path to publication is unusual – I sold the first novel I ever wrote, before age 30.

But wait! Before the other authors start throwing things at me, let me tell the whole story.

I first went to art school (Rhode Island School of Design), where I studied photography. I learned I didn't want to be a photographer, but I got a great education in creativity and critiquing. Learning how to analyze and express what I feel works and doesn't work in other people's art has served me well in analyzing my own writing and especially in teaching/critiquing others. And learning how to take a critique as a learning experience helped build a thick skin. I also started writing for the school paper and got interested in journalism.

After two years of going nowhere much, I went back to college for my MA degree in Professional Writing and Publishing. Although I was focused on magazine nonfiction, I took classes in fiction, children's picture books, and book publishing. I went to New York City to look for work in magazines. While job hunting and doing temp work, I decided to start a novel for my own entertainment. I had an idea for a middle grade (ages 9 to 12) novel set in Mayan Guatemala, where I'd spent a summer traveling after college.

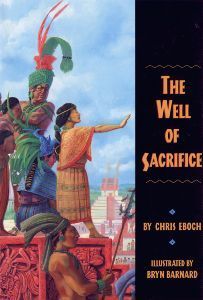

That became

The Well of Sacrifice

, which got me an agent and a book contract with Clarion – mainly because I was very, very lucky. First of all, historical fiction for kids was selling much better then than it does today. And there was no other historical fiction about the pre-Columbian Maya for middle grade kids. I didn't know that, or that kids study the Maya in fourth grade, or that teachers often use supplemental fiction when they teach history. So I accidentally wrote a book that was very marketable. It came out in 1999, and I still get a nice royalty check twice a year, mainly because of school purchases.

That became

The Well of Sacrifice

, which got me an agent and a book contract with Clarion – mainly because I was very, very lucky. First of all, historical fiction for kids was selling much better then than it does today. And there was no other historical fiction about the pre-Columbian Maya for middle grade kids. I didn't know that, or that kids study the Maya in fourth grade, or that teachers often use supplemental fiction when they teach history. So I accidentally wrote a book that was very marketable. It came out in 1999, and I still get a nice royalty check twice a year, mainly because of school purchases.

I also got lucky because I didn't make any of the mistakes first novelist typically make. I saved those for my second book… And my third… And my fourth… In fact, I went on to write something like eight novels that I couldn't sell. I don't know if I would've had the stamina to keep with it if I hadn't had that early success.

I had naïvely quit my job at a magazine and moved west after selling the book, because I had money in the bank and thought I could make it as a writer. Over the next decade, I did work for hire nonfiction, sold a couple of short stories and a larger number of articles, and taught writing for children through a correspondence course and at local colleges (and did a lot more temp work).

I finally sold a series in 2008. Haunted, about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, launched with three books. Then my editor got fired and the publisher canceled the series. You know how common experiences like this are? I was recently on a panel about "hope and rejection" at a writers schmooze, and three of us have had gaps of at least seven years between book sales. The fourth person had sold her first novel a couple of years prior, but the publisher went out of business six months before they were supposed to release it. Another publisher took on the book, but her editor had just rejected her second novel.

A couple of years ago, I was feeling burnt out on writing for children, so I decided to start writing romantic suspense for adults. My former editor had become my agent, and he wanted to represent my first book. However, I had been reading a lot about new options in indie publishing, and I wasn't happy with what I was hearing from traditional publishers (lower advances without higher royalties, etc.). I said I was thinking about self-publishing, and my agent agreed that was the best path today for genre fiction.

I have released three books for adults in the last two years, under the name Kris Bock, to separate that work from my children's books. I haven't sold a lot of copies yet, but I have gotten good reviews, even from strangers. I've been focusing more on getting the first books out, so that I could market a body of work. I didn't want to get bogged down in publicity after just one book. I've also been learning a lot about publishing and publicity, so hopefully I can be more focused with my time.

I also released two of my unsold children's books – the fourth book in my Haunted series, because I'd already written it and I had an interested audience. And a mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh . Although many of my early, unsold books were not publishable, I was confident this one had merit. It was a finalist in the New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards, and it has been picked up by several teachers for classroom use. It's the one making me the most money so far. Second is Advanced Plotting, a guide for writers adapted from my workshops, blog posts, and articles in Children's Writer and Writers Digest.

I'm still doing a lot of work for hire (children's nonfiction, test passages, manuscript critiques, writing articles, workshops) to pay the bills. 2011 has been fairly good financially, but my goal is to shift more of my income to my fiction.

I'm thinking about doing a breakdown in the new year on where my 2011 income came from, as an example of how a professional writer makes a living. Would you be interested in hearing about that, or should I stick more to writing craft?

My path to publication is unusual – I sold the first novel I ever wrote, before age 30.

But wait! Before the other authors start throwing things at me, let me tell the whole story.

I first went to art school (Rhode Island School of Design), where I studied photography. I learned I didn't want to be a photographer, but I got a great education in creativity and critiquing. Learning how to analyze and express what I feel works and doesn't work in other people's art has served me well in analyzing my own writing and especially in teaching/critiquing others. And learning how to take a critique as a learning experience helped build a thick skin. I also started writing for the school paper and got interested in journalism.

After two years of going nowhere much, I went back to college for my MA degree in Professional Writing and Publishing. Although I was focused on magazine nonfiction, I took classes in fiction, children's picture books, and book publishing. I went to New York City to look for work in magazines. While job hunting and doing temp work, I decided to start a novel for my own entertainment. I had an idea for a middle grade (ages 9 to 12) novel set in Mayan Guatemala, where I'd spent a summer traveling after college.

That became

The Well of Sacrifice

, which got me an agent and a book contract with Clarion – mainly because I was very, very lucky. First of all, historical fiction for kids was selling much better then than it does today. And there was no other historical fiction about the pre-Columbian Maya for middle grade kids. I didn't know that, or that kids study the Maya in fourth grade, or that teachers often use supplemental fiction when they teach history. So I accidentally wrote a book that was very marketable. It came out in 1999, and I still get a nice royalty check twice a year, mainly because of school purchases.

That became

The Well of Sacrifice

, which got me an agent and a book contract with Clarion – mainly because I was very, very lucky. First of all, historical fiction for kids was selling much better then than it does today. And there was no other historical fiction about the pre-Columbian Maya for middle grade kids. I didn't know that, or that kids study the Maya in fourth grade, or that teachers often use supplemental fiction when they teach history. So I accidentally wrote a book that was very marketable. It came out in 1999, and I still get a nice royalty check twice a year, mainly because of school purchases.I also got lucky because I didn't make any of the mistakes first novelist typically make. I saved those for my second book… And my third… And my fourth… In fact, I went on to write something like eight novels that I couldn't sell. I don't know if I would've had the stamina to keep with it if I hadn't had that early success.

I had naïvely quit my job at a magazine and moved west after selling the book, because I had money in the bank and thought I could make it as a writer. Over the next decade, I did work for hire nonfiction, sold a couple of short stories and a larger number of articles, and taught writing for children through a correspondence course and at local colleges (and did a lot more temp work).

I finally sold a series in 2008. Haunted, about a brother and sister who travel with a ghost hunter TV show, launched with three books. Then my editor got fired and the publisher canceled the series. You know how common experiences like this are? I was recently on a panel about "hope and rejection" at a writers schmooze, and three of us have had gaps of at least seven years between book sales. The fourth person had sold her first novel a couple of years prior, but the publisher went out of business six months before they were supposed to release it. Another publisher took on the book, but her editor had just rejected her second novel.

A couple of years ago, I was feeling burnt out on writing for children, so I decided to start writing romantic suspense for adults. My former editor had become my agent, and he wanted to represent my first book. However, I had been reading a lot about new options in indie publishing, and I wasn't happy with what I was hearing from traditional publishers (lower advances without higher royalties, etc.). I said I was thinking about self-publishing, and my agent agreed that was the best path today for genre fiction.

I have released three books for adults in the last two years, under the name Kris Bock, to separate that work from my children's books. I haven't sold a lot of copies yet, but I have gotten good reviews, even from strangers. I've been focusing more on getting the first books out, so that I could market a body of work. I didn't want to get bogged down in publicity after just one book. I've also been learning a lot about publishing and publicity, so hopefully I can be more focused with my time.

I also released two of my unsold children's books – the fourth book in my Haunted series, because I'd already written it and I had an interested audience. And a mystery set in ancient Egypt, The Eyes of Pharaoh . Although many of my early, unsold books were not publishable, I was confident this one had merit. It was a finalist in the New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards, and it has been picked up by several teachers for classroom use. It's the one making me the most money so far. Second is Advanced Plotting, a guide for writers adapted from my workshops, blog posts, and articles in Children's Writer and Writers Digest.

I'm still doing a lot of work for hire (children's nonfiction, test passages, manuscript critiques, writing articles, workshops) to pay the bills. 2011 has been fairly good financially, but my goal is to shift more of my income to my fiction.

I'm thinking about doing a breakdown in the new year on where my 2011 income came from, as an example of how a professional writer makes a living. Would you be interested in hearing about that, or should I stick more to writing craft?

Published on December 12, 2012 03:30

December 7, 2012

Writing Tight: Don't Be Wordy

I have two tight deadlines next week, but I've already missed a couple of posts recently, so here's a quickie. I do a lot of manuscript critiques. (See my rates and recommendations. If that link won't click through, copy and paste this link: http://www.chriseboch.com/newsletter.htm). Even advanced writers often get wordy. Here are some tips on eliminating that problem so your writing is as tight as my deadlines (plus other sources with more detail).

One of my pet peeves is characters nodding their heads or shrugging their shoulders. What else would one nod or shrug? We don't nod our elbows or shrug our stomachs. (If you have a character doing that, then definitely specify!) Otherwise, you can simply say he noddedor she shrugged. Yes, I know, this is a tiny, unimportant detail. But trust me, once it's pointed out to you, you'll start to notice and find it irritating!

Another unnecessary phrase – he thought to himself. Unless you have psychic characters, we'll assume he's not thinking to someone else. (In close point of view, you don't need to use "he thought" at all; just state the thought and we'll understand that the character is thinking it. But that's another issue.)

I need to get back to work, but in case you have more web browsing time, here are a couple of my favorite posts on eliminating wordiness.

Cut the Clutter and Streamline Your Writing, from Crime Fiction Collective, by Jodie Renner Editing: “Once you’ve gotten through your first draft, it’s important to go back in and cut down on wordiness and redundancies in order to make your story more compelling, pick up the pace, and increase the tension and sense of urgency.”

Cut the Clutter and Streamline Your Writing, Part II, from Crime Fiction Collective by Jodie Renner Editing: “Start by cutting out qualifiers like very, quite, rather, somewhat, kind of, and sort of, which just dilute your message, weaken the imagery, and dissipate the tension.”

It’s a Story, Not an Instruction Manual!, from Crime Fiction Collective, by Jodie Renner Editing: “Whether you’re writing an action scene or a love scene, it’s best not to get too technical or clinical about which hand or leg or finger or foot is doing what, unless it’s relevant or necessary for understanding.”

And a warning not to take things too far:

Crossing Words Off Your List: Making the Most of Editing "What Not to Use" Lists, from The Other Side of the Story by Janice Hardy: “The right word for what you're trying to say is always the right choice, no matter what that word is. Most times, cutting that flabby word or finding that strong noun or active verb is the right choice, but once in a while it's not.”

Published on December 07, 2012 03:30

December 5, 2012

Another Company Enters the Self-Publishing Market

Simon & Schuster's has announced a new self-publishing imprint, Archway Publishing. The imprint is run by Author Solutions, a vanity press with a long and questionable history. Here are a couple of blog posts on the subject. These contain individual opinions,but the bloggers' numbers appear to be correct based on a quick look around the Archway site. Please be very cautious about doing business with anyone who claims to be representing Penguin who may really be trying to sell you services through Archway. A traditional publisher NEVER asks for money up front.

A New Way To Rob the Poor?, By Andrew E. Kaufman

Simon & Schuster Joins Forces With Author Solutions To Rip Off Writers

This may sound familiar because Penguin’s parent company, Pearson, purchased Author Solutions in July. (Here's an opinion on that: Penguin’s New Business Model: Exploiting Writers) My personal opinion: Big publishers need to look for innovative ways to increase revenue. Valid options include starting e-book-first imprints and lowering or eliminating advances while giving authors a greater royalty rate. They do not involve lending the publisher's name to a shady and overpriced vanity press.

Published on December 05, 2012 03:30

November 19, 2012

Publicity Options: Ask David

A huge challenge for writers, whether traditionally or self published, is spreading the word about your books. Some people spend thousands of dollars hiring a publicist, but how do you know if you will get your money's worth? And if you are working on your own, how do you know you'll get your time's worth?

I have been somewhat active on Good Reads. I also have profiles on Library Thing, Jacket Flap, Red Room, and Authors Den. It takes a few hours to update all these sites every time I have a new book out, but it's important to have your book where people can find it.

Another community of book lovers and reviewers I've discovered recently is Ask David. Although not the largest out there, it offers a free opportunity for authors to promote their books, including a free book promotion page, links to websites/Facebook/Twitter etc., and the potential for reviews from users. It only took a few minutes to fill out the form, and they do the rest. This service can be free to the authors because the site gets a small commission from Amazon for sales through site links.

As authors, of course we'd rather spend our time writing – but it's worth trying some of the promotional sites, especially the free ones.

Published on November 19, 2012 04:00

November 16, 2012

Happy Endings

Back in June and July I did a series of posts on the process of turning an idea into a story. (Those essays are under the tag "developing ideas"). A story has four main parts: idea, complications, climax and resolution. I’ve talked a lot about getting off to a strong start and developing the middle of the story. Last week I talked about the climax. Now let’s look at how stories wind down—the resolution.

The climax ends with the resolution. You could say that the resolution finishes the climax but comes from the idea: it’s how the main character finally meets that original challenge.

In almost all cases the main character should resolve the situation himself. Here’s where many beginning children’s writers fail. It’s tempting to have an adult—a parent, grandparent, or teacher, or even a fairy, ghost or other supernatural creature—step in to save the child or tell him what to do.

That’s a disappointment for two reasons. First, we’ve been rooting for the main character to succeed. If someone else steals the climax away from him, it robs the story of tension and feels unfair. Second, kids are inspired by reading about other children who tackle and resolve problems. It helps them believe that they can meet their challenges, too. When adults take over, it shows kids as powerless and dependent on grownups. So let your main character control the story all the way to the end!

Child characters can receive help from others, though, including adults. In

I Am Jack

by Susanne Gervay (Tricycle Press, 2009), Jack faces bullying. He solves his problem, in part, by asking for help. In the end, Jack stands up for himself, but with the support of family, teachers, and friends. It’s a realistic ending that inspires kids to take charge in their own lives.

Child characters can receive help from others, though, including adults. In

I Am Jack

by Susanne Gervay (Tricycle Press, 2009), Jack faces bullying. He solves his problem, in part, by asking for help. In the end, Jack stands up for himself, but with the support of family, teachers, and friends. It’s a realistic ending that inspires kids to take charge in their own lives.Though your main character should be responsible for the resolution, she doesn’t necessarily have to succeed. She might, instead, realize that her goals have changed. In My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters by Sydney Salter (HM Harcourt, 2009), Jory starts out thinking that she needs a nose job to change her life. After a series of humorous disasters, Jory decides she really doesn’t need surgery to feel better about herself.

Stories for younger children generally have happy or at least optimistic endings, even if the original goal changes. Teen stories may be ambiguous or even unhappy. Unhappy endings are probably most common in “problem novels,” such as stories about the destruction of drug addiction. The main character’s failure acts as a warning to readers.

Stories for younger children generally have happy or at least optimistic endings, even if the original goal changes. Teen stories may be ambiguous or even unhappy. Unhappy endings are probably most common in “problem novels,” such as stories about the destruction of drug addiction. The main character’s failure acts as a warning to readers.This principle is equally important when writing for adults. Don't fall back on deus ex machina, the Calvary to the rescue, etc. Your main character should solve the problem. Even in today's romance novels, the heroine is more likely to rescue herself (and maybe the hero) than to let the hero do all the work.

Tip: How the main character resolves the situation—whether she succeeds or fails, and what rewards or punishments she receives—will determine the theme. Ask yourself:

What am I trying to accomplish? Who am I trying to reach? Why am I writing this?

Once you know your theme, you know where the story is going, and how it must be resolved. In My Big Nose and Other Natural Disasters, Salter wanted to show that happiness comes from within, rather than from external beauty. Therefore, Jory had to learn that lesson, even if it conflicted with her original goal of getting a nose job.

Published on November 16, 2012 04:00

November 14, 2012

The Relationship Between Plot and Setting

I "met" Vickie Britton through a marketing listserv for mystery writers. Since I love mysteries and history, especially ancient Egypt, I had to grab a copy of The Curse of Senmut, a mystery she wrote with her sister. And they have others involving the Maya and Inca as well! So many wonderful books, so little free time. Vickie and Loretta also have one e-book on the craft of writing, Fiction: From Writing to Publication (available on Amazonor Smashwords) and one focused on mystery novels,

Writing and Selling a Mystery Novel: A Simple Step-by Step Plan

, available on Smashwords. Here they share some advice on The Relationship Between Plot and Setting

A good setting works hand in hand with plot, for like the scenes of a movie or the props for a play, it establishes the necessary background for the action and the success of your story. Below is an excerpt from our ebook Fiction: From Writing to Publication.

Developing a setting is very important to a novel for it adds flavor and color to the book. Many times a novel is begun because of the author’s interest in a particular setting. Because of this, a sense of place emerges naturally from what is known and understood. Often writers select their home towns, states and countries where they have lived or visited, or one where they want to go. If this place is significant to the writer, it will show in the work. What would Tony Hillerman’s novels be without the canyons and small towns of New Mexico, or Willa Cather’s without the Nebraska prairie?

Developing a setting is very important to a novel for it adds flavor and color to the book. Many times a novel is begun because of the author’s interest in a particular setting. Because of this, a sense of place emerges naturally from what is known and understood. Often writers select their home towns, states and countries where they have lived or visited, or one where they want to go. If this place is significant to the writer, it will show in the work. What would Tony Hillerman’s novels be without the canyons and small towns of New Mexico, or Willa Cather’s without the Nebraska prairie?

In The Bridges of Madison County, author Robert James Waller wrote so convincingly about the area that readers actually went in search of the covered bridge mentioned in his story, even though the bridge itself is fictional.

While it is the best policy to travel to your settings, you can portray a good setting with proper research. Say you want to set your book in China. Sometimes it’s just not possible to have an extended stay in China, although a ten-day trip might be within your budget. But if it’s not possible to travel to your chosen setting at all except in your mind, the Internet and the library become your new best friends.

Pictures, written narratives, websites with shots of the area can give you a feel for the setting without actually traveling to the location. The Internet, especially, has become a good source for viewing remote areas through specialized maps and photographs, providing details that were once not possible without an actual visit.... Whether your books are set on the Sioux Reservation in South Dakota or in an English village, a strong setting will often draw and hold readers. A story can be set in a big city, a small town, or just about anywhere in between, but it is always of great importance. Your job as an author is to create a good setting and make sure it is in harmony with the characters you are creating. [End excerpt.]

What works best for us is to personally visit every setting for our stories, to get a feeling for the location. Sometimes we may change certain details such as making up our own towns, rivers, mountains, etc, but they are always in keeping with what might be found in the actual area.

Here are some examples of how some of our plots have developed from our own experience with travel and personal interests. Ardis Cole, in our Ardis Cole Mystery Series, is an archaeologist who travels the world and runs into a crime in every different place. The plots for these novels were actually formed from the settings. For instance, in

The Curse of Senmut

a tomb is located which is believed to belong to Senmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s scribe and lover, and in

Unmarked Grave

a skull is found on the grounds of an ancient castle in Scotland, one that we visited.

Here are some examples of how some of our plots have developed from our own experience with travel and personal interests. Ardis Cole, in our Ardis Cole Mystery Series, is an archaeologist who travels the world and runs into a crime in every different place. The plots for these novels were actually formed from the settings. For instance, in

The Curse of Senmut

a tomb is located which is believed to belong to Senmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s scribe and lover, and in

Unmarked Grave

a skull is found on the grounds of an ancient castle in Scotland, one that we visited.

When Vickie lived in Laramie, Wyoming, we became drawn to the Old West, the legends and rough terrain. From this love grew our High Country Mystery Series, The Luck of the Draw Western Series, and the Western single Death Comes in Pairs.

An authentic setting will draw the reader into the story and give them a sense of actually being there.

Biography: Loretta Jackson and Vickie Britton are sisters and co-authors of forty-three novels and numerous short stories, mostly mysteries and westerns. Loretta lives in Junction City, Kansas, and Vickie in Hutchinson, Kansas. Loretta taught school at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota while Vickie was living in Laramie, Wyoming. There they became interested in the legends and history of the Old West. Their recent titles include Whispers of the Stones, The Wild Card, The Lost City of the Condorand The Viking Crown .The sisters were recently interviewed in The Mystery Writers:Interviews and Advice by Jean Henry Mead More about the authors and their works can be found by visiting their web page , or Amazon Author Central.

Biography: Loretta Jackson and Vickie Britton are sisters and co-authors of forty-three novels and numerous short stories, mostly mysteries and westerns. Loretta lives in Junction City, Kansas, and Vickie in Hutchinson, Kansas. Loretta taught school at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota while Vickie was living in Laramie, Wyoming. There they became interested in the legends and history of the Old West. Their recent titles include Whispers of the Stones, The Wild Card, The Lost City of the Condorand The Viking Crown .The sisters were recently interviewed in The Mystery Writers:Interviews and Advice by Jean Henry Mead More about the authors and their works can be found by visiting their web page , or Amazon Author Central.

A good setting works hand in hand with plot, for like the scenes of a movie or the props for a play, it establishes the necessary background for the action and the success of your story. Below is an excerpt from our ebook Fiction: From Writing to Publication.

Developing a setting is very important to a novel for it adds flavor and color to the book. Many times a novel is begun because of the author’s interest in a particular setting. Because of this, a sense of place emerges naturally from what is known and understood. Often writers select their home towns, states and countries where they have lived or visited, or one where they want to go. If this place is significant to the writer, it will show in the work. What would Tony Hillerman’s novels be without the canyons and small towns of New Mexico, or Willa Cather’s without the Nebraska prairie?

Developing a setting is very important to a novel for it adds flavor and color to the book. Many times a novel is begun because of the author’s interest in a particular setting. Because of this, a sense of place emerges naturally from what is known and understood. Often writers select their home towns, states and countries where they have lived or visited, or one where they want to go. If this place is significant to the writer, it will show in the work. What would Tony Hillerman’s novels be without the canyons and small towns of New Mexico, or Willa Cather’s without the Nebraska prairie?In The Bridges of Madison County, author Robert James Waller wrote so convincingly about the area that readers actually went in search of the covered bridge mentioned in his story, even though the bridge itself is fictional.

While it is the best policy to travel to your settings, you can portray a good setting with proper research. Say you want to set your book in China. Sometimes it’s just not possible to have an extended stay in China, although a ten-day trip might be within your budget. But if it’s not possible to travel to your chosen setting at all except in your mind, the Internet and the library become your new best friends.

Pictures, written narratives, websites with shots of the area can give you a feel for the setting without actually traveling to the location. The Internet, especially, has become a good source for viewing remote areas through specialized maps and photographs, providing details that were once not possible without an actual visit.... Whether your books are set on the Sioux Reservation in South Dakota or in an English village, a strong setting will often draw and hold readers. A story can be set in a big city, a small town, or just about anywhere in between, but it is always of great importance. Your job as an author is to create a good setting and make sure it is in harmony with the characters you are creating. [End excerpt.]

What works best for us is to personally visit every setting for our stories, to get a feeling for the location. Sometimes we may change certain details such as making up our own towns, rivers, mountains, etc, but they are always in keeping with what might be found in the actual area.

Here are some examples of how some of our plots have developed from our own experience with travel and personal interests. Ardis Cole, in our Ardis Cole Mystery Series, is an archaeologist who travels the world and runs into a crime in every different place. The plots for these novels were actually formed from the settings. For instance, in

The Curse of Senmut

a tomb is located which is believed to belong to Senmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s scribe and lover, and in

Unmarked Grave

a skull is found on the grounds of an ancient castle in Scotland, one that we visited.

Here are some examples of how some of our plots have developed from our own experience with travel and personal interests. Ardis Cole, in our Ardis Cole Mystery Series, is an archaeologist who travels the world and runs into a crime in every different place. The plots for these novels were actually formed from the settings. For instance, in

The Curse of Senmut

a tomb is located which is believed to belong to Senmut, Queen Hatshepsut’s scribe and lover, and in

Unmarked Grave

a skull is found on the grounds of an ancient castle in Scotland, one that we visited.When Vickie lived in Laramie, Wyoming, we became drawn to the Old West, the legends and rough terrain. From this love grew our High Country Mystery Series, The Luck of the Draw Western Series, and the Western single Death Comes in Pairs.

An authentic setting will draw the reader into the story and give them a sense of actually being there.

Biography: Loretta Jackson and Vickie Britton are sisters and co-authors of forty-three novels and numerous short stories, mostly mysteries and westerns. Loretta lives in Junction City, Kansas, and Vickie in Hutchinson, Kansas. Loretta taught school at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota while Vickie was living in Laramie, Wyoming. There they became interested in the legends and history of the Old West. Their recent titles include Whispers of the Stones, The Wild Card, The Lost City of the Condorand The Viking Crown .The sisters were recently interviewed in The Mystery Writers:Interviews and Advice by Jean Henry Mead More about the authors and their works can be found by visiting their web page , or Amazon Author Central.

Biography: Loretta Jackson and Vickie Britton are sisters and co-authors of forty-three novels and numerous short stories, mostly mysteries and westerns. Loretta lives in Junction City, Kansas, and Vickie in Hutchinson, Kansas. Loretta taught school at the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota while Vickie was living in Laramie, Wyoming. There they became interested in the legends and history of the Old West. Their recent titles include Whispers of the Stones, The Wild Card, The Lost City of the Condorand The Viking Crown .The sisters were recently interviewed in The Mystery Writers:Interviews and Advice by Jean Henry Mead More about the authors and their works can be found by visiting their web page , or Amazon Author Central.

Published on November 14, 2012 04:00

November 9, 2012

Building Your Novel: The Climax!!!

In previous posts, I’ve talked about setting up conflict and building tension through the middle of the story. Finally, at the climax, the main character must succeed or fail. You’ve built to this point with your complications. Now time is running out. The race is near the end. The girl is about to date another guy. The villain is starting the battle. It’s now or never.

However you get there, the climax will be strongest if it is truly the last chance. You lose tension if the reader believes the main character could fail this time, and simply try again tomorrow.

In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the high priest throws Eveningstar off a cliff into a sacrificial pool. If she can survive and get back to the main temple in secret, she can confront the high priest with new status as a messenger from the gods. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all.

In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the high priest throws Eveningstar off a cliff into a sacrificial pool. If she can survive and get back to the main temple in secret, she can confront the high priest with new status as a messenger from the gods. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all.

In my Haunted series, each book takes place in a new location where the ghost hunter TV show is researching a ghost. The shoot will last only a couple of days. If Jon and Tania don’t figure out how to help the ghost within that time, they’ll lose their chance. I gave this challenge added importance through backstory—they had a little sister who died, so the idea of someone being stuck in an unhappy ghostly state has special resonance.

Movies are well-known for this “down to the wire” suspense, regardless of genre. In Star Wars, Luke blows up the Death Star during the final countdown as the Death Star prepares to blow up the planet. In Back to the Future, Marty must get his parents together before the future changes irretrievably and he disappears. He’s actually fading when they finally kiss. In the romantic comedy Sweet Home Alabama, Melanie decides whom she really loves as she’s walking down the aisle to marry the wrong man.

The technique works just as well for books and stories, and you'll get the most suspense if the stakes are high. In my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), Audra would be perfectly happy to leave the murder investigation to the police – except the killer seems to be targeting her. She has to find out who's responsible before she becomes the next victim. In

Whispers in the Dark

(also written as Kris Bock), the heroine stumbles into a dangerous situation by accident, but once she's there, her life is at stake, and so is the life of the man she's starting to love.

The technique works just as well for books and stories, and you'll get the most suspense if the stakes are high. In my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), Audra would be perfectly happy to leave the murder investigation to the police – except the killer seems to be targeting her. She has to find out who's responsible before she becomes the next victim. In

Whispers in the Dark

(also written as Kris Bock), the heroine stumbles into a dangerous situation by accident, but once she's there, her life is at stake, and so is the life of the man she's starting to love.

This works for some nonfiction as well, especially biographies or memoirs. In Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker , the book I wrote under the name M.M. Eboch, the true story had a natural ticking clock – the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany, where Jesse could prove himself or fail.

Exercises:

Study some of your favorite books. Is there a “ticking bomb,” where the characters have one last chance to succeed before time runs out? If not, how would it change the book to add one?

Now look at your work in progress, a completed manuscript draft or outline. Do your characters have a time deadline? Do you wait until the last possible moment to allow them to succeed? If not, can you add tension to the story by finding a way to have time running out?

Tips:

Don’t rush the climax. Take the time to write the scene out in vivid detail, even if the action is happening fast. Think of how movies switch to slow motion or use multiple shots of the same explosion, in order to give maximum impact to the climax.

To make the climax feel fast-paced, use mainly short sentences and short paragraphs. The reader’s eyes move more quickly down the page, giving a sense of breathless speed. (See my posts on Cliffhangers.)

However you get there, the climax will be strongest if it is truly the last chance. You lose tension if the reader believes the main character could fail this time, and simply try again tomorrow.

In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the high priest throws Eveningstar off a cliff into a sacrificial pool. If she can survive and get back to the main temple in secret, she can confront the high priest with new status as a messenger from the gods. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all.

In

The Well of Sacrifice

, the high priest throws Eveningstar off a cliff into a sacrificial pool. If she can survive and get back to the main temple in secret, she can confront the high priest with new status as a messenger from the gods. But the penalty for failure is death—the highest stake of all.

In my Haunted series, each book takes place in a new location where the ghost hunter TV show is researching a ghost. The shoot will last only a couple of days. If Jon and Tania don’t figure out how to help the ghost within that time, they’ll lose their chance. I gave this challenge added importance through backstory—they had a little sister who died, so the idea of someone being stuck in an unhappy ghostly state has special resonance.

Movies are well-known for this “down to the wire” suspense, regardless of genre. In Star Wars, Luke blows up the Death Star during the final countdown as the Death Star prepares to blow up the planet. In Back to the Future, Marty must get his parents together before the future changes irretrievably and he disappears. He’s actually fading when they finally kiss. In the romantic comedy Sweet Home Alabama, Melanie decides whom she really loves as she’s walking down the aisle to marry the wrong man.

The technique works just as well for books and stories, and you'll get the most suspense if the stakes are high. In my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), Audra would be perfectly happy to leave the murder investigation to the police – except the killer seems to be targeting her. She has to find out who's responsible before she becomes the next victim. In

Whispers in the Dark

(also written as Kris Bock), the heroine stumbles into a dangerous situation by accident, but once she's there, her life is at stake, and so is the life of the man she's starting to love.

The technique works just as well for books and stories, and you'll get the most suspense if the stakes are high. In my mystery/suspense novel

What We Found

(written as Kris Bock), Audra would be perfectly happy to leave the murder investigation to the police – except the killer seems to be targeting her. She has to find out who's responsible before she becomes the next victim. In

Whispers in the Dark

(also written as Kris Bock), the heroine stumbles into a dangerous situation by accident, but once she's there, her life is at stake, and so is the life of the man she's starting to love.This works for some nonfiction as well, especially biographies or memoirs. In Jesse Owens: Young Record Breaker , the book I wrote under the name M.M. Eboch, the true story had a natural ticking clock – the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany, where Jesse could prove himself or fail.

Exercises:

Study some of your favorite books. Is there a “ticking bomb,” where the characters have one last chance to succeed before time runs out? If not, how would it change the book to add one?

Now look at your work in progress, a completed manuscript draft or outline. Do your characters have a time deadline? Do you wait until the last possible moment to allow them to succeed? If not, can you add tension to the story by finding a way to have time running out?

Tips:

Don’t rush the climax. Take the time to write the scene out in vivid detail, even if the action is happening fast. Think of how movies switch to slow motion or use multiple shots of the same explosion, in order to give maximum impact to the climax.

To make the climax feel fast-paced, use mainly short sentences and short paragraphs. The reader’s eyes move more quickly down the page, giving a sense of breathless speed. (See my posts on Cliffhangers.)

Published on November 09, 2012 04:00

November 2, 2012

Endings: The Storm before the Calm

I've been discussing building a strong novel. Of course an important part of the novel is the climax, the big ending. You want the climax to be the most dramatic part of the novel, so the reader walks away satisfied. But before we get to the climax itself, let's look at the moment right before the climax. My brother, script writer Doug Eboch, has this to say about movie plots:

“There’s one other critical structural concept you need to understand. That is the moment of apparent failure (or success). Whatever the Resolution to your Dramatic Question is, there needs to be a moment where the opposite appears to be inevitable. So if your character succeeds at the end, you need a moment where it appears the character will fail. And if your character fails at the end, you need a moment where they appear to succeed.” (The full essay is in my writing craft book, Advanced Plotting .)

I wondered whether this held equally true for novels. Looking through a few of the books on my shelf, certainly the climax is a crisis point where the reader may believe that everything is going wrong and the main character could fail.

In The Ghost on the Stairs , Tania is possessed by a ghost and her brother Jon isn’t sure if he’ll be able to save her.

In The Well of Sacrifice , Eveningstar is thrown into the sacrificial well, a watery pit surrounded by high cliffs, and realizes no one will rescue her.

In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the lion Aslan is killed and the good army is losing their battle.

In adult mystery or suspense novels, this may be the point where the bad guy has captured the hero or is threatening to kill him.

In a romance, this is the point where the couple is farthest apart and we wonder how they’ll ever resolve their differences to live happily ever after.

Does your story or novel have a crisis point, a moment at the climax where readers truly believe the main character could fail? If not, you may want to rethink your plot or rewrite the action to make the climax more intense and challenging. The happy ending is only satisfying if it is won at great expense through hard work. In literature as in real life, people don’t always value what comes easily. Success feels that much sweeter when it can be contrasted to the suffering we’ve had to endure.

Next week I'll talk about the climax itself.

See Doug’s entire 4000-word essay covering all the dramatic story points of three-act structure, plus much more, in Advanced Plotting. Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.Douglas J. Eboch wrote the original script for Sweet Home Alabama. He teaches at Art Center College of Design and lectures internationally. He writes a blog about screenwriting at http://letsschmooze.blogspot.com/.

Published on November 02, 2012 04:00

October 31, 2012

Haunted Book 4: The Ghost Miner’s Treasure

In honor of Halloween, I'm making the Kindle e-book version of my children's novel, The Ghost Miner’s Treasure, FREE today (October 30-31). This is book 4 of my Haunted series originally published by Aladdin/Simon & Schuster. Book 4 can be read on its own. It's a spooky comedy/mystery suitable for ages 8+.

Haunted Book 4: The Ghost Miner’s Treasure, by Chris Eboch

Jon and Tania are traveling with the ghost hunter TV show again, this time to the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, where the ghost of an old miner is still looking for his lost mine. The siblings want to help him move on—but to help him resolve the problem keeping him here, they’ll have to find the mine. And even then, the old ghost may be having too much fun to leave! It’s a good thing Tania can see and talk to him, because the kids will need his help to survive the rigors of a mule train through the desert, a flash flood, and a suspicious treasure hunter who wants the gold mine for himself.

FREE for Kindle Oct. 31: http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009M8T33Q

If you stop by to pick up a copy, I appreciate "Likes" for the book's page or agreeing with the tag words (scroll down and click in each box, or simply paste the following list after "Your Tags": Ghosts, ghost story, mystery, adventure, gold miner, middle grade, action, spooky, paranormal, ghost hunters, children's horror, ghost stories for children, Arizona fiction )

Here's chapter 1:

“Many dangers you face on this quest. Many trials.” The old woman leaned over the table. A wisp of gray hair escaped from her bun and hung in her face. Light streaked through the dirty windows, making craggy shadows in her wrinkles. She stared down at the sticks and bones she’d tossed on the table, her mouth moving silently.My stepfather, Bruce, stood across the table from her, leaning forward intently. She looked up at him and spoke. “What you seek is not easily found. There are those who would stand in your way. But you also have helpers.”She looked around at the rest of us. I thought her eyes rested on my sister, Tania, as she said, “Some good luck.”Her eyes met mine. “Some bad luck.”I shivered. Did she mean I would have bad luck? Or that I was the bad luck? “What do you advise?” Bruce asked.The old woman shrugged. “You will go. You will do what must be done. It is meant to be.” Her eyes met mine again, intently. “But be careful whom you trust.” Cold crept up my spine, though the room was hot and stuffy. Bruce leaned forward and asked a question. Mom shifted restlessly and took a step toward him. I glanced at Maggie, the pretty production assistant. She met my look and rolled her eyes.My breath exploded out. It wasn’t really a laugh; I just hadn’t realized I’d been forgetting to breathe. I grinned at Maggie, suddenly lighter. I’d gotten caught up in the atmosphere of the dark room and the spooky old lady. But Maggie had reminded me that I didn’t believe in fortune-tellers. Bad luck happened, sure, but no old woman could predict it ahead of time.Of course, a year earlier I hadn’t believed in ghosts, either. Things had changed when my sister and I started traveling with Haunted, the ghost investigation TV show run by my mom and stepfather. I hadn’t yet seen a ghost, but my sister had. I hadn’t believed her at first, but I’d changed my mind after seeing her possessed, and all the other strange things we had faced.Still, believing in ghosts didn’t mean I had to believe everything. I didn’t even know why we were talking to this fortune-teller. During the filming of the last show, Tania and I had proven that Madame Natasha, Bruce’s “psychic” guest star, was a fake. In the process, we’d accidentally made Bruce look like a fool and hurt the show’s reputation. We’d learned our lesson there, and Bruce had sworn off psychics. But here we were.Maggie touched my arm and bobbed her head toward the door. I nodded and followed her, Tania at my side. We paused outside, blinking in the bright sun. Maggie’s dark curls tumbled around her shoulders. Tania looked small and washed out next to her.Maggie shook her head. “You’d think he’d have learned by now.”“She’s different than Madame Natasha. More....” Tania bit her lip and looked back toward the door.“Sincere?” Maggie asked. “Creepy,” I suggested. “I mean, Madame N was a creep, but this woman is just spooky.”“She does seem to believe what she’s saying,” Maggie said, “which is more than I can say for Madame Natasha.” She shrugged. “But what did she really say? Good luck, bad luck, nothing that can be proven or disproved. It’s generally a fair bet that some things will go right and some will go wrong. And of course a ghost won’t be found easily. We have yet to prove they even exist!”I nodded, glad Maggie hadn’t noticed the fortune teller looking at me when she mentioned bad luck. Maybe it didn’t mean anything after all. I wanted to smack myself. Of course it didn’t mean anything! I’d already decided that. If I wasn’t careful, I was going to turn superstitious.“At least Bruce isn’t planning to use her on the show,” Maggie said. “He can’t stop himself from wanting to believe, but he’ll be more careful about keeping the show scientific.”I nodded. I actually felt sorry for Bruce. It was hard to know what to believe. Sometimes I wished I could just believe the things I wanted to believe and not worry about it. But life is more complicated than that.“So, can we look around the town while they finish?” Tania asked.Maggie glanced left and right. The town of Vulture had one main dirt street, a few hundred yards long, and not much else. You couldn’t even drive through the town; you had to park in a lot by the entrance. A big wooden water tank and a windmill stood on top of the hill. Across the highway, a cluster of weird rock towers rose up in the foothills of the Superstition Mountains. “I don’t see how you can possibly get in trouble.” Maggie winked. “Though who knows, you’ve surprised me before. Go ahead, I’ll tell your mom. I’m sure we’ll find you.” The old wooden buildings had been turned into stores, with a bakery, fudge shop, antique store, and a “general store” that sold T-shirts and postcards. “Some ghost town,” I said. “I thought ghost towns were supposed to be abandoned. This looks more like a tourist trap.”“It really was an old frontier town, though,” Tania said. “In the 1800s. Maggie was telling me about it. I guess nobody lives here now, they just come in to run the stores. And on summer weekends and holidays they do shows. You know, guys dress up as gunfighters and have shootouts in the street.”We looked at each other and shrugged. Maybe that would have sounded fun once, but now it seemed like kid stuff. We’d had a lot more excitement in our lives than watching grownups play-act and fire blank guns.“Well, where do you want to start looking for the real ghost?” I asked.Tania tipped her head to one side. “It wouldn’t take long to search the whole town. But first let’s think about what we know about him.” She closed her eyes. “Jacob Waltz was born in Germany around 1810. He came to America about 1840 and headed west. He tried gold-mining in California before winding up here in Arizona in 1862.”She opened her eyes again, and I took over the story. “In 1869 he came into town with a sack of ore, almost pure gold. He went straight to the saloon, bought drinks for everyone, and bragged about the mine he’d found in the mountains. The newspapers picked up the story. For the next two years, Waltz lived off that gold and didn’t set foot in the mountains. He was probably afraid someone would follow him and find his mine.”Tania nodded. “But when his gold ran out, he went back to the mountains with a burro to carry his riches. Two months later, he was back in town—empty-handed. He couldn’t find the mine again. He spent the next five years looking for it, with no luck. He died at sixty-six, penniless, in rags, half starved. Some said he went crazy.”She looked sad, so I quickly said, “What’s the most logical place to look for an elderly ghost trying to drown his sorrows over losing his gold mine?”We glanced down the street and looked at each other. Simultaneously, we said, “The saloon.”

Published on October 31, 2012 03:30

October 26, 2012

How to Write Vivid Scenes 3: Cause and Effect

I've been talking about writing vivid scenes, an important part of keeping suspense and tension up throughout your novel. Let's finish up our discussion on scenes with the rest of an essay adapted from my writing craft book, Advanced Plotting

-- looking at cause and effect.

-- looking at cause and effect.Cause and Effect

One of the ironies of writing fiction is that fiction has to be more realistic than real life. In real life, things often seem to happen for no reason. In fiction, that comes across as unbelievable. We expect stories to follow a logical pattern, where a clear action causes a reasonable reaction. In other words, cause and effect.

The late Jack M. Bickham explored this pattern in Scene & Structure, from Writer’s Digest Books. He noted that every cause should have an effect, and vice versa. This goes beyond the major plot action and includes a character’s internal reaction. When action is followed by action with no internal reaction, we don’t understand the character’s motives. At best, the action starts to feel flat and unimportant, because we are simply watching a character go through the motions without emotion. At worst, the character’s actions are unbelievable or confusing.

In Manuscript Makeover: Revision Techniques No Fiction Writer Can Afford to Ignore

(Perigee Books), Elizabeth Lyon suggests using this pattern: stimulus—reaction/emotion—thoughts—action.Something happens to your main character (the stimulus);You show his emotional reaction, perhaps through dialog, an exclamation, gesture, expression, or physical sensation;He thinks about the situation and makes a decision on what to do next;Finally, he acts on that decision.

(Perigee Books), Elizabeth Lyon suggests using this pattern: stimulus—reaction/emotion—thoughts—action.Something happens to your main character (the stimulus);You show his emotional reaction, perhaps through dialog, an exclamation, gesture, expression, or physical sensation;He thinks about the situation and makes a decision on what to do next;Finally, he acts on that decision.This lets us see clearly how and why a character is reacting. The sequence may take one sentence or several pages, so long as we see the character’s emotional and intellectual reaction, leading to a decision.

Bickham offered these suggestions for building strong scenes showing proper cause and effect:

The stimulus must be external—something that affects one of the five senses, such as action or dialog that could be seen or heard.

The response should also be partly external. In other words, after the character’s emotional response, she should say or do something. (Even deciding to say nothing leads to a reaction we can see, as the character turns away or stares at the stimulus or whatever.)

The response should immediately follow the stimulus. Wait too long and the reader will lose track of the original stimulus, or else wonder why the character waited five minutes before reacting.

Be sure you word things in the proper order. If you show the reaction before the action, it’s confusing: “Lisa hurried toward the door, hearing pounding.” For a second or two, we don’t know why she’s hurrying toward the door. In fact, we get the impression that Lisa started for the door before she heard the pounding. Instead, place the stimulus first: “Pounding rattled the door. Lisa hurried toward it.”

If the response is not obviously logical, you must explain it, usually with the responding character’s feelings/thoughts placed between the stimulus and the response. Here’s an example where the response is not immediately logical:

Knocking rattled the door. (Stimulus)Lisa waited, staring at the door. (Action)

Why is she waiting? Does she expect someone to just walk in, even though they are knocking? Is she afraid? Is this not her house? To clarify, include the reaction:

Knocking rattled the door. (Stimulus)Lisa jumped. (Physical Reaction) It was after midnight and she wasn’t expecting anyone. Maybe it was a mistake. Maybe they’d go away. (Thoughts)She waited, staring at the door. (Responsive Action)

In some cases the response may be logical and obvious without including thoughts and emotions in between. For example, if character A throws a ball and character B raises a hand to catch it, we don’t need to hear character B thinking, “There’s a ball coming at me. I had better catch it.” But don’t assume your audience can always read between the lines. Often as authors we know why our characters behave the way they do, so we assume others will understand and we don’t put the reaction and thoughts on the page. This can lead to confusion.

In one manuscript I critiqued, the character heard mysterious voices. I assumed they were ghosts, but the narrator never identified them that way. Did he think they were something else? Did he think he was going crazy? Had he not yet decided? I couldn’t tell. The author may have assumed the cause of the voices was obvious, so she didn’t need to explain the character’s reaction. But it just left me wondering if I was missing something—or if the character was. Err on the side of showing your character’s thoughts.

Link your scenes together with scene questions and make sure you’re including all four parts of the scene—stimulus, reaction/emotion, thoughts, and action—and you’ll have vivid, believable scenes building a dramatic story. Advanced Plotting is designed for the intermediate and advanced writer: you’ve finished a few stories, read books and articles on writing, taken some classes, attended conferences. But you still struggle with plot, or suspect that your plotting needs work.Advanced Plotting can help.Buy Advanced Plotting

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

for $9.99 in paperback or as a $4.99 e-book on Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or in various e-book formats from Smashwords.

Published on October 26, 2012 04:00