Wouter J. Hanegraaff's Blog

September 2, 2025

Blavatsky Stripped Bare by a Buddhologist, Even.

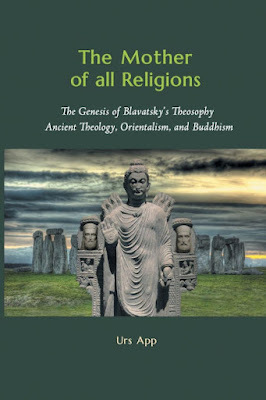

I just finished reading this splendid new book by the Swiss scholar Urs App (I already knew him from a previous book about The Birth of Orientalism). Finally, somebody has done all the hard historical-philological work that is required to uncover the true foundations of Helena P. Blavatsky’s Theosophy, one of the most influential esoteric movements of the late nineteenth and the twentieth century. App’s method rests on some simple and quite traditional but essential foundations. (1) Take the time to carefully study all the relevant primary sources, i.e. not just some part of what HPB wrote, but really everything she wrote; (2) consistently place those sources in a strict chronological order, if possible even on a day-to-day basis, so that you can see exactly how her thinking develops over time; (3) don’t be satisfied by just scanning “the discourse” in general terms, as is common in academia today, but analyze her ideas; and finally (4) do whatever you can to identify the exact written sources from which she drew those ideas at any moment in that chronological sequence.

I just finished reading this splendid new book by the Swiss scholar Urs App (I already knew him from a previous book about The Birth of Orientalism). Finally, somebody has done all the hard historical-philological work that is required to uncover the true foundations of Helena P. Blavatsky’s Theosophy, one of the most influential esoteric movements of the late nineteenth and the twentieth century. App’s method rests on some simple and quite traditional but essential foundations. (1) Take the time to carefully study all the relevant primary sources, i.e. not just some part of what HPB wrote, but really everything she wrote; (2) consistently place those sources in a strict chronological order, if possible even on a day-to-day basis, so that you can see exactly how her thinking develops over time; (3) don’t be satisfied by just scanning “the discourse” in general terms, as is common in academia today, but analyze her ideas; and finally (4) do whatever you can to identify the exact written sources from which she drew those ideas at any moment in that chronological sequence. This empirical-historical method - bottom-up historiography and textual criticism - allows Urs App to establish beyond a shadow of doubt that Blavatsky did not have any first-hand familiarity with Tibetan Buddhism, as she famously claimed; that she invented her famous Mahatmas and those mysterious occult orders in which she said she had been initiated; that her ideas about Oriental Wisdom were based not on the Indian or more specifically Buddhist traditions she encountered in India but on Western Spiritualist and Orientalist literature about those traditions; and that her entire oeuvre is based on one single obsession - to prove the existence of a primordial wisdom tradition, “the mother of all religions,” which she imagined as a kind of Buddhism prior to and independent of historical Buddhism. Of course, most modern scholars of Theosophy already assumed or suspected most of these things (pioneering work having been done by specialists such as Joscelyn Godwin, Michael Gomes, or Pat Deveney), but the difference is that App succeeds in demonstrating them so completely and so conclusively that these debates can now be considered settled once and for all. It is not just a question of countless and usually unacknowledged borrowings, plagiarisms, or paraphrases from whatever book Blavatsky happened to have in front of her at the time she was writing. At least as important is her reliance on dictionaries of Oriental languages to build up a Theosophical vocabulary that, unfortunately, shows again and again that she did not know those languages and made countless elementary mistakes (in sharp contrast, of course, with her own claims of having “translated” many textual passages from mysterious Oriental sources). None of this is speculation on App's part. Again, he does not just suggest it but demonstrates it, at a great many instances, by precise comparisons between HPB’s statements and what you actually find in those dictionaries and other sources if you just take the trouble to look them up - and of course, if you actually know something about Buddhism and its history, and can read the languages.

The result is a thrilling piece of historical detective work, beginning with Blavatsky’s early exposure to Allen Kardec in 1858 (a neglected topic, for while HPB was fluent in French, many modern scholars are not), from there to the crucial years 1874-1875, when she began creating her system in New York, and then all the way up to her period in India and her return to Europe and finally her death. Devastating as the conclusions may be to true believers in Theosophy, it would be mistaken to think of this book as just another exercise in “debunking Blavatsky” by exposing her as a fraud. On the contrary, App is doing the work that historians of religion are supposed to do, quite similar to how the discipline of biblical criticism inevitably undermines traditional Christian doctrine - not out of some desire to destroy religious or esoteric beliefs but simply out of a commitment to truth. Certainly, Blavatsky was continually deceiving her readers, and probably herself as well, and yet there’s little doubt that she believed sincerely in her primordial wisdom tradition. Her sources might be fabricated and she might have been manipulating her readers and everybody around her; but she seems to have believed that this ultimately did not matter, because the doctrine itself was true, her intentions were good, and the results of her “pious deceptions” would ultimately benefit humanity. The end justified the means. Be that as it may, App is perfectly right to finish his book by reminding his readers of a basic Theosophical tenet: no religion higher than truth.

The result is a thrilling piece of historical detective work, beginning with Blavatsky’s early exposure to Allen Kardec in 1858 (a neglected topic, for while HPB was fluent in French, many modern scholars are not), from there to the crucial years 1874-1875, when she began creating her system in New York, and then all the way up to her period in India and her return to Europe and finally her death. Devastating as the conclusions may be to true believers in Theosophy, it would be mistaken to think of this book as just another exercise in “debunking Blavatsky” by exposing her as a fraud. On the contrary, App is doing the work that historians of religion are supposed to do, quite similar to how the discipline of biblical criticism inevitably undermines traditional Christian doctrine - not out of some desire to destroy religious or esoteric beliefs but simply out of a commitment to truth. Certainly, Blavatsky was continually deceiving her readers, and probably herself as well, and yet there’s little doubt that she believed sincerely in her primordial wisdom tradition. Her sources might be fabricated and she might have been manipulating her readers and everybody around her; but she seems to have believed that this ultimately did not matter, because the doctrine itself was true, her intentions were good, and the results of her “pious deceptions” would ultimately benefit humanity. The end justified the means. Be that as it may, App is perfectly right to finish his book by reminding his readers of a basic Theosophical tenet: no religion higher than truth.

July 26, 2025

Politics and the Study of [Western] Esotericism

On 2 July 2009, I gave a “President’s Opening Address” at the opening of the 2nd Biannual Conference of the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE) in Strasbourg, France. [1] It never got published, but I made it available on my Academia.edu page, where it can still be found under “talks.” I believe that the argument in this lecture remains highly relevant today, and may even be more relevant than ever, because the return to power of far-right ideologies that worried me so deeply at the time (as you can see from the text below) has obviously continued year after year and is now impossible for anyone to miss. During the 1990s, it was still common and intuitive to think of far-right esotericism as a topic of mere “historical interest,” because the liberal-democratic consensus seemed quite secure and few of us imagined that it might start to crumble during our lifetimes. Yet here we are. Especially after the trauma of 9/11 (not to mention the rise of social media since the 2010s), popular feelings of resistance to the effects of neoliberal globalization gave far-right ideologies their chance to return to the political mainstream. Of course, these developments couldn't fail to be reflected also in the emerging field of esotericism research.

What follows is a literal reproduction of my lecture from 2009, including the footnotes that I added when I put it online. I have made no changes to the text, except for adding updates to those footnotes (and adding a few new footnotes as well) which are placed within square brackets and marked as Add 2025. This makes it possible for my readers to see exactly what I was thinking in 2009 and how I look at these topics from my current perspective sixteen years later. I’m happy to see that I still agree entirely with everything I said at the time! But I can now also see my own speech as a kind of historical document that provides a glimpse of how things were looking (to me, at least) at an earlier moment in time – two years before the financial crisis delivered an enormous shock to the neoliberal-global consensus from which it never really recovered, thus accelerating the process of political change that brought us to our present situation. One of the biggest temptations of political discourse is to become so obsessed by the present that we forget the “look and feel” of how the world appeared to all of us even in the relatively recent past. So this is a small exercise in revisiting that recent past from the perspective of the present.

Ladies and gentlemen,

As president of the ESSWE it is a pleasure for me to welcome you to this second biannual conference of our society, which is taking place this year in a city that has played a central role in the development towards European union after the second world war. Given this special location, and its symbolic significance as a nodal point in the complex web of European political relations, I would like to use the occasion to say a few introductory words today about the political dimensions of the study of esotericism, particularly in the present European context. It is a topic that has been on my mind for years, and I believe the time is ripe to put it on the agenda of our society.

As is well known, the wish to work towards greater European union after World War II was motivated by the widely-felt wish to prevent any future repetition of the catastrophe caused by right-wing totalitarianism and militarism. It is therefore ironic, and certainly worrying, that many Europeans in recent years have begun to experience the European Community itself as a distant and impersonal system of domination and control that disempowers voters and in fact undermines democracy. In my own country, which had long been known for its traditions of tolerance and a pragmatic approach to the tensions caused by cultural, ethnic and religious plurality, this sense of disempowerment is now resulting in a new attractiveness of far right-wing populist movements which promise their voters that they will restore “power to the people” by taking it away from the political elites, and go on to promise that they will re-instate “law and order” so as to repair what they see as the damage done by the left and its soft and too tolerant politics. In this context, representatives of ethnic and religious minorities are now routinely being scapegoated and treated as second-rate citizens, whose very presence is felt to be intolerable, and whose right to have beliefs and practices different from those of the native population is called into question. [2]

History does not repeat itself, but patterns of intolerance do. Unfortunately, drawing historical parallels between the current situation and the kind of cultural and political climate which ultimately gave birth to fascism and anti-Semitic ideologies in Europe in the first half of the 20th century, under conditions of economic crisis, remains largely taboo, at least in the Dutch media and public debate with which I am best familiar. [3]

Now you will be wondering: what does all this have to do with the study of esotericism? Quite a lot, in fact.

To begin with the most obvious parallel: our society, the ESSWE, is itself a kind of European union of scholars of esotericism. As President of this Society, I can only hope that ours is felt to be representative of its members and their wishes.

Secondly, and more importantly, as scholars we are professionally committed to the study of currents and beliefs, which have very frequently been seen as heretical, subversive and dangerous, and have therefore been subject to censorship and political suppression, both by religious and by secular institutions. [4] Scholars in our field therefore have particularly good reasons for insisting on the value of religious tolerance, calling attention to the positive and creative dimensions of religious plurality in the space of European culture, and emphasizing the importance of a nuanced and well-informed approach to religious minorities whose beliefs and practices are too often simplified and distorted in mainstream and popular media presentations. Religious polemics have a logic of their own, which we are particularly well placed to analyze: [5] by studying the dynamics of polemicism (and its counterpart apologeticism) in the context of European history of religion, I believe we can learn lessons with a relevance that goes well beyond esotericism alone.

Thirdly, it is well known that esotericists, particularly since the 18th century, have frequently been active themselves in political theorizing and even political practice, and their perspectives mirror and reflect the more general European political developments of their time. During the 19th century (and contrary to popular assumptions), esotericists were often strongly engaged in progressive causes linked to secularization, modernization, democratization, and social emancipation, experimenting with, and sometimes pioneering, perspectives that would now be seen as leaning mostly towards the left. [6] During the 20th century, on the other hand, many esoteric authors began to react against secularization and the modern world, often developing conservative, traditionalist and elitist worldviews; and in a number of important cases, such authors went all the way towards trying to lend metaphysical legitimacy to forms of fascism, national socialism, and anti-Semitism. Of course this is only one dimension of modern and contemporary esotericism, much of which is far from any such orientations; but it is certainly a very important one. One of our tasks as scholars is to study the complex relations between esotericism and politics thoroughly, critically, and with attention to nuance and detail. Among our own membership, important pioneering work in this regard has been done by well-known specialists such as Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke [7] and Hans Thomas Hakl, [8] to mention only two; and across the Atlantic, one might think of recent work by colleagues such as, for example, Arthur Versluis [9] or Hugh B. Urban. [10] It is good news that our American counterpart, the Association for the Study of Esotericism, has decided to devote its next biannual conference precisely to esotericism and politics. [10a]

However, fourthly, precisely such research appears to carry specific risks for scholars in our field; and to this final point I would like to give some special attention. Since the Second World War, it has often been suggested both by influential public intellectuals [11] and the popular media that esotericism or the occult is, somehow, intrinsically fascist; and in some countries (Germany in particular, but to a lesser extent, France as well) this association has become almost an automatic reflex among intellectuals. [11a] The idea that the mythical and “irrational” dimensions of esotericism somehow make it implicitly fascist has tainted the field as a whole, and has long been an important factor in preventing it from being recognized as a normal field of academic research. On a personal level too, it has not been unusual for scholars of esotericism to find themselves suspected of fascist leanings for no other reason than the fact that they have chosen to specialize in such a “suspect” domain. I myself first became aware of this dynamics at the time I defended my dissertation on the New Age movement. [12] Although it was not even available yet in print, a rather well-known Dutch journalist felt he did not need to wait and read it, and used it as the occasion for an article about New Age and its supposed connection with fascism, under the utterly bizarre title “Wodan is not recognized”… [13] This case was silly enough to make it possible for me to merely smile about it; but not all my colleagues have been so fortunate, and their own experiences have sometimes been far from amusing. Some of the best scholars in the study of esotericism, many of them members of our society, have, at some point in their career, made the painful experience of seeing themselves listed or “exposed” as an apologist of the far right or as a crypto-fascist. [13a] And it is predictable that those whose research has focused specifically on the links between fascism and esotericism have been particularly vulnerable in that regard.

For a professional academic organization like ours, this phenomenon is too important to ignore. The popular association between esotericism and fascism is bound to surface again and again, in the popular media and elsewhere, and therefore we as a society for the study of Western esotericism should better think about it seriously. And what is more, I believe the association is far from random. Ultimately, I would argue, it is a reflection of deep structures in European culture which have to do with the complex dialectics of simultaneous attraction and rejection between biblical monotheistic traditions on the one hand, and the “pagan” traditions of Platonism and Hermetism on the other. Unless I am mistaken, this dialectics goes to the very heart of our field of study. [14]

Another reason for us to be concerned about popular associations of esotericism with fascism, finally, is that it constitutes a crucial test case for how serious we are about defending the very foundations of the academic enterprise. Let me explain what I mean with this. As scholars, we are committed to critical methodologies which historically, since the 18th century, have played a crucial emancipatory role by undermining the political dominance of traditional religious authority and helping create the foundations of modern secular democracies. [15] Apart from sheer brutal force, the exercise of political power typically requires information control and manipulation of knowledge; and from that perspective, the scholarly nuance that comes with critical methodologies is necessarily an unwelcome obstacle. We can see this logic at work in the propaganda machines of any totalitarian system known from history or in our own time; but in less extreme forms, it is a standard temptation for anybody in a position of political power.

One common technique of information control is that of secrecy and concealment, i.e. preventing the common population from having access to “classified” information: a practice which is deeply problematic from the perspective of critical scholarship, which requires open debate based upon full access to all relevant sources of information. Another technique is dualistic simplification. Sensitive issues need to be simplified so as to create clear and unambiguous boundaries between “good” and “evil,” the “good guys” and the “bad guys,” “us” and “them.” But critical academic scholarship, in sharp contrast, is bound to question such simplifications and call attention rather to complexity, nuance, and ambiguity. It therefore undermines or disrupts the effectiveness of political power. Instead of rhetoric, it requires arguments; instead of rumors or insinuations, it requires evidence; instead of easy generalizations it requires often difficult analyses. In thus taking the hard and difficult road towards knowledge, critical scholarship is necessarily subversive of political power and control.

It is therefore predictable that if scholars of esotericism venture into sensitive political domains – and to a considerable extent, the whole field of esotericism is a sensitive political domain! –, they may find that the weapons of simplification are being turned against themselves, attempts will be made to restrict the free dissemination of information and knowledge, and they may find themselves under attack personally.

It is easy to find examples in our field. For instance, scholars of new religious movements often see themselves forced to refute anti-cult stereotypes as factually inaccurate, and to replace such stereotypes by much more complex analyses based upon careful study of the evidence. For this, they are often rewarded by being stereotyped themselves: as cult apologists who must surely be on the payroll of Scientology, or naïve inhabitants of the academic ivory tower whose so-called scholarship makes them blind to the evil of the groups they study. The contempt for knowledge and professional expertise reflected in such anti-academic rhetoric is often shocking; and all the more so if one finds it reflected in official government documents and legislation. [16]

Another example brings us back to the theme of esotericism and the extreme right. Scholars studying the relation between politics and esotericism are bound to call attention, for reasons of simple accuracy and respect for historical evidence, to the actual variety of historical fascisms and right-wing ideologies, which have taken very different shapes in different European countries and cultural traditions, and cannot all be tarred by the same brush. But here too, scholars who thus try to lift the debate to a higher academic level by insisting on nuance, complexity and reliable knowledge may sadly find themselves rewarded by being portrayed as apologists for fascism, who are muddying the waters by blurring the sharp boundaries between right and wrong, and are therefore eligible for censorship and exclusion from academic debate. Such cases are most painful when they are inspired by sheer political expediency, for example when academic institutions exclude scholars or scholarly projects simply because they are afraid of what their colleagues, the media, or financial sponsors might say.

This brings me to my conclusion, which is a very simple one: responsible scholarship requires moral and political courage. This is true of scholarship in general, but it is particularly relevant in a domain like the study of esotericism. We are not just in the business of writing nice and safe articles or books about interesting groups and personalities, or advancing our careers in academia. Rather, as scholars we are engaged in an inherently political enterprise, in which we are required to defend “the pursuit of knowledge” against the “the pursuit of power.” [17] Respect for facts and demonstrable evidence, insistence on critical argumentation, and open debate without censorship of opinions are not self-evidently given: on the contrary, they are necessarily problematic and unwelcome from the perspective of power, and therefore must be gained and defended again and again by each new generation of scholars. This struggle is not an easy one, and one cannot play safe. But the goal is worth the effort: that of an open society based upon the free pursuit of knowledge: a society, in fact, in which the very distinction between orthodoxy and heresy has become meaningless. Of course I know that such a society sounds like a utopian ideal. But even though it may never be reached, our task as scholars is to walk the road that leads towards it.

With these opening remarks, I hope to have given you some food for thought and discussion. I now open the second biannual conference of the ESSWE, and wish you all an excellent time.

[1] Strasbourg, July 2. The theme of the 2nd biannual conference of the ESSWE was Capitals of European Esotericism and Transcultural Dialogue; but I consider it the privilege of a scholarly society’s president to use the occasion of an Opening Address to call attention to topics that he considers to be of general importance for the society.

[2] I am, of course, referring to the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV: Party for Freedom) headed by Geert Wilders, which according to present polls might well become one of the largest parties, or even the largest one, in the next Dutch elections. Wilders became known internationally by his movie Fitna, the message of which is essentially that the string of terrorist attacks since 9/11 must be attributed not just to Muslim extremists, but to the very nature of Islam as such; all muslims in the Netherlands should therefore be seen (so the logic goes) as implicitly condoning or lending support to terror unless they renounce their religion. Accordingly, Wilders, in spite of his strong advocacy of “freedom of speech,” would like to prohibit the Quran along with Hitler’s Mein Kampf. [Add 2025: Wilders’ PVV went on to win 24 seats in the 2010 Dutch elections, against 31 for Mark Rutte’s liberal VVD and 21 for Maxime Verhagen’s Christian-Democratic CDA. After protracted negotiations, this resulted in the highly unstable first Rutte cabinet, with a slim majority coalition of VVD/CDA and the PVV in a role of “confidence and supply.” Wilders withdrew his support on April 21, 2012, leading to the fall of the cabinet. In the elections of 22 November 2023, Wilders’ PVV gained 37 seats and became the largest party in the Netherlands. Eventually, this resulted in the cabinet Schoof, consisting of the PVV, VVD, and the new parties NSC (Nieuw Sociaal Contract) and BBB (BoerBurgerBeweging) from 2 July 2024 to 3 June 2025, when the PVV withdrew over a conflict about immigration reforms. As it turns out, the worries I expressed in 2009 were therefore well-founded].

[3] It goes without saying that there are many important differences between the popular antisemitism widespread in Europe during the first decades of the 20th century and popular anti-Islam sentiments as prevalent today in a country like the Netherlands. However, history has taught us how popular antisemitism can give rise to antisemitism as a virulent political ideology, and the anti-Islamic sentiments which are currently gaining prominence can easily be exploited by right-wing populists to muster support for equally intolerant and dangerous ideologies. If Hitler notoriously came to power with the message (as formulated by Heinrich von Treitschke) Die Juden sind unser Unglück, right-wing populists are now highly successful with the message Die Muslime sind unser Unglück. In my opinion, if drawing such parallels is considered illegitimate, we are giving up the attempt to learn lessons from history.

[4] I do not mean to suggest that Western esotericism should be equated with heresy (many heretical movements in the history of Europe are unrelated to esotericism, and much that we study under the heading of “Western esotericism” has never been considered heretical). Nevertheless, particularly the perception of Western esoteric currents as ultimately grounded in (Platonic, Hermetic, or Zoroastrian) “paganism” has often caused them to attacked as anti-Christian heresy, and particularly after the 17thand 18th centuries, much of Western esotericism became part of a field of “rejected knowledge” from the perspective of mainstream academic thinking. [Add 2025: this line of argumentation led to a monograph published three years later: Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, Cambridge University Press 2012. In my most recent work I have taken the analysis one step further. I now speak of an “internal Eurocentrism” that, as I argue, became the basic template for the “external-Eurocentric” suppression and extermination of “primitive idolatry and magical superstition” in the colonial age (Esotericism in Western Culture: Counter-Normativity and Rejected Knowledge, Bloomsbury 2025).]

[5] See e.g. Olav Hammer & Kocku von Stuckrad (eds.), Polemical Encounters: Esoteric Discourse and Its Others, Leiden: Brill 2008. On my own notion of a “grand polemical narrative” constitutive of Western esotericism as a field of research, see Wouter J. Hanegraaff, “Forbidden Knowledge: Anti-Esoteric Polemics and Academic Research,” Aries 5:2 (2005), 225-254; and idem, “The Trouble with Images: Anti-Image Polemics and Western Esotericism,” in: Hammer & von Stuckrad, o.c., 107-136. [Add 2025: these two publications from 2005 and 2009, too, contained embyronic versions of the eventual argument of Esotericism and the Academy (2012).]

[6] See e.g. Marco Pasi, “The Modernity of Occultism: Reflections on Some Crucial Aspects,” in: Wouter J. Hanegraaff & Joyce Pijnenburg (eds.), Hermes in the Academy, Amsterdam: Vossiuspers 2009 (forthcoming). [Add 2025: this article got published in the same year 2009. Since then, as the critical study of esotericism developed, many further analyses of esotericism and the political left have been published, for instance by Julian Strube, “Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism: A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France,” Religion 46:3 (2016), 359-388; or, very recently, Ansgar Martins, “The German Jewish Occult: Frankfurt School Critical Theory and the Philosophy of the ‘Irrational’,” Aries 25:2 (2025), 258-303. See also my general remarks in Esotericism in Western Culture, 185-186.]

[7] See notably Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke’s classic The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and their Influence on Nazi Ideology, orig. 1985, repr. London / New York: I.B. Tauris 1992. [Add 2025: I did not mention Goodrick-Clarke’s later publications in this domain, notably Hitler’s Priestess: Savitri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth, and Neo-Nazism (New York University Press 1998) and Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity (New York University Press 2002). This is because I found them problematic in several respects, but this ESSWE lecture would not have been the proper occasion for a critical book review. For relevant critical observations that mirror my own, see e.g. Nathan Katz’s review in Journal of the American Academy of Religion 67:4 [1999], 890-892).]

[8] E.g. Hans Thomas Hakl, Unknown Sources: National Socialism and the Occult, Holmes Publ. Group 2000. [Add 2025: Hakl and his famous “Octagon Library” have recently been the subject of a special issues of Religiographies 2:1 (2023), including inter alia an article by myself focused on Hakl's Eranos book, a biographical overview by Bernd-Christian Otto, and an Introduction by Marco Pasi that addresses well-known controversies about Hakl’s involvement in publishing ventures connected to the far right, an issue that is also addressed by Hakl himself in a large interview on his website (https://www.hthakl-octagon.com/interview/interview-englisch/). Concerning regrettable “lapses in basic source criticism” that turn out be more frequent in Hakl’s publications on Evola than was known at the time, see the excellent very recent analysis by Peter Staudenmaier, “Evola’s Afterlives: Esotericism and Politics in the Posthumous Reception of Julius Evola,” Aries 25:2 (2025), 163-193, here 184.]

[9] Arthur Versluis, The New Inquisitions: Heretic-Hunting and the Intellectual Origins of Modern Totalitarianism, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006.

[10] Hugh B. Urban, The Secrets of the Kingdom: Religion and Concealment in the Bush Administration, Lanham etc.: Rowman & Littlefield 2007.

[10a] [Add 2025: the proceedings of this conference were published as Arthur Versluis, Lee Irwin & Melinda Phillips (eds), Esotericism, Religion, and Politics, Association for the Study of Esotericism / North American Academic Press 2012.]

[11] E.g. Theodor Adorno, “Theses against Occultism,” in: The Stars down to Earth and other Essays on the Irrational in Culture, London, New York: Routledge 1994, 128-134 (German orig. 1947); Umberto Eco, “Ur-Fascism,” The New York Review of Books 42:11 (June 22, 1995), 12-15. [Add 2025: for a recent analysis of Adorno’s theses, see Andreas Kilcher, “Is Occultism as Product of Capitalism?,” in: Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Peter J. Forshaw & Marco Pasi (eds.), Hermes Explains: Thirty Questions about Western Esotericism, Amsterdam University Press 2019, 168-176; and see also my forthcoming chapter “Anti-Esotericism” in Henrik Bogdan (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Esotericism, Oxford University Press forthcoming.]

[11a] [Add 2025: One typical example would be the introductory textbook Esoterik, published two years after my lecture by the German professor in history of religion Hartmut Zinser (see my very sharp review in “Textbooks and Introductions to Western Esotericism,” Religion 43:2 [2013], here 193-195). I argue in my more recent work that, historically, this particular polemical discourse can be accounted for in terms of the wide influence and intellectual authority after World War II of the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School (Esotericism in the Academy, 312-314; Esotericism in Western Culture, 188-189). Nowadays I would describe it even more specifically as a clear example, among many others, of the “internal Eurocentric” discourse concerning Western culture that I criticize in my recent work (see above, note 4). It should go without saying, but must perhaps be pointed out to hasty readers, that the argument has nothing to do with the popular far-right meme of “Cultural Marxism” (its both amusing and alarming story has been told by the major Frankfurt school specialist Martin Jay in his “Dialectic of Counter-Enlightenment: The Frankfurt School as Scapegoat of the Lunatic Fringe,” Salmagundi 168/169 [2010-2011], 30-40). On the perhaps surprising “esoteric” dimensions of Critical Theory itself, see the fascinating recent discussion by Ansgar Martins, “The German Jewish Occult: Frankfurt School Critical Theory and the Philosophy of the ‘Irrational’,” Aries 25:2 (2025), 258-303.]

[12] Wouter J. Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought, Leiden: Brill 1996 (defended as Ph.D. in 1995).

[13] René Zwaap, “Wodan wordt miskend”, De Groene Amsterdammer 15 november 1995 (the opening sentence implied that “Wodan” now finally gets academic recognition due to my study of New Age).

[13a] [Add 2025: This trend has unfortunately continued after 2009 and would even seem to be experiencing a revival in recent years. Here I merely mention the phenomenon, while refraining from mentioning names, for several reasons. Firstly, this updated publication of an old lecture would not be the place for engaging in polemics against authors or online sources that have much more recently become active. Secondly, I won’t give assistance to bad actors by further spreading their defamatory content. Thirdly, the worst offenders simply do not deserve to be given serious credit, in my opinion, especially if they engage in conspiracy narratives built on non sequiturs and the well-known repertoire of tricks to suggest guilt-by-association. It should go without saying (but again, may nevertheless need to be repeated) that it remains perfectly legitimate to criticize scholars who commit real offenses, such as racist rhetoric or any other ways of spreading hate against groups or individuals. ]

[14] I hope to develop this argument in detail in my forthcoming monograph Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture (projected for publication in 2010 or 2011). [Add 2025: this obviously happened]

[15] For “criticism” as foundational to the Enlightenment project, a classic reference is Peter Gay, The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, New York, London: W.W. Norton & Co 1966. A major example of the critical spirit is, of course, Immanuel Kant, with his three Kritiken and his paradigmatic insistance on free intellectual inquiry: sapere aude! (“What is Enlightenment?” [1784], in: Margaret C. Jacob [ed.], The Enlightenment: A Brief History with Documents, Boston, New York: Bedford/St.Martins 2001, 202-208). Modern biblical criticism was a crucial factor in the decline of the authority of Scripture; and more generally, the rise of historical criticism undermined the authority of traditional accounts of the history of the Church. [Add 2025: see now my distinction between a “good” Enlightenment1 and a “bad” Enlightenment2: Esotericism in Western Culture, 205-207).]

[16] I am thinking here of the notorious government report Les sectes en France (Documents d’information de l’Assemblée Nationale no. 2468, 1996), which was based entirely on the perspectives of the anti-cult movement and accounts of ex-members, while systematically disregarding academic specialists (see Massimo Introvigne & J. Gordon Melton [eds.], Pour en finir avec les sectes: Le débat sur le rapport de la commission parlementaire, Paris: Dervy 1996).

[17] I am aware of the fact that, in the wake of influential intellectuals such as Foucault, Bourdieu and others, the very idea of separating knowledge from power may be seen as questionable. In my opinion, it would indeed be naïve to deny the fact that claims of knowledge are always tied up with claims of power. However, this does not imply that the former can be reduced to the latter, or that there are no facts but only discourses making claims about facts. [Add 2025: in this regard, see now also my discussion of “discourse and reality” in Esotericism in Western Culture, 17-21 “The Discursive Turn.”]

July 24, 2025

Netanyahu's crimes against humanity are crimes against Judaism

I feel it’s time for me to make a statement. Many of my Jewish and Israeli friends have been perfectly wide awake, for as long as I can remember, about the criminal mentality of the far-right government of Netanyahu and his political allies Smotrich and Ben-Gvir. They have been marching through the streets of Israel, have made their voices heard in public, and continue doing so day by day. Many others have begun waking up, some faster and others more slowly, as the true extent of the atrocities became impossible to deny. But unfortunately, there are also those who still keep suggesting that the crimes against humanity committed by Hamas – before, during, and after 7 October – somehow legitimate or excuse the crimes against humanity that are currently being committed on a daily basis by the IDF at the orders of the Netanyahu government, with the backing of the United States and the cowardly complicity of far too many European politicians, including those in my own country. There are also those who keep insisting or insinuating that any critique of the Netanyahu government for crimes against humanity, including the large-scale murder and starvation of innocent children who have no way to defend themselves, is antisemitic – as though this has anything at all to do with the notorious blood libel, which is usually brought up in this context.

Meanwhile, we do indeed see an alarming rise of antisemitism worldwide, for a very simple reason that’s perfectly easy to understand. It is that far too many people, on all sides, just don’t bother to draw any clear distinctions between Jews or Judaism, the state of Israel, and the current government of that state. In the case of Netanyahu and his allies or supporters, this is perfectly convenient because it allows them to accuse anyone of "antisemitism" who dares to critize their policies and actions. But it’s just as convenient for their opponents, because it allows them to use this government’s inhumanity as a weapon for attacking the state of Israel’s right to exist or, indeed, for “blaming the Jews.” And then, of course, there is everybody else. Normal, decent people all over the world find it unbearable to watch the daily atrocities but do not necessarily think all too deeply about who is to blame and who isn't, about the complex historical developments that brought us where we are, or indeed about distinguishing a bit more carefully between the Netanyahu government, the state of Israel as such, and Jews in general.

Such intellectual carelessness may be human nature, but it’s not an excuse. We are witnessing acts of inhumanity, the memory of which will be haunting all of us for generations to come, and none of us will be able to claim that “we did not know.” We did know, or at the very least we could have known if we had bothered to open our eyes and pay attention, but too many of us don’t want to know and prefer to look away. On the other hand, and understandably enough, too many of those who cannot bring themselves to look away are deeply confused by the complexity of the issues. As a result, they may not always be aware of how easily their own heartfelt feelings of sorrow and outrage may be mined and manipulated by the cynical forces of polarization, extremism and hate. As for myself, I’m not a Jew and I don't live in Israel, but I care deeply about Judaism and everything it stands for. This is precisely why it disturbs me so deeply, not just to watch the routinization of inhumanity that’s on full display in Gaza, but also to see how the atrocious actions and mentality of the current Israeli government are actively feeding the flames of antisemitism. This madness must stop.

December 4, 2023

A Poem at the Edge of Reality

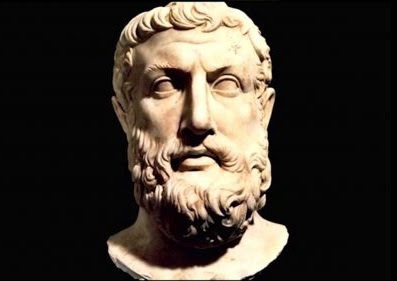

In the beginning an immortal goddess explained reality to a mortal man. Or at least, she tried. She told him to be silent and just listen to her words, and so that’s what he did. All we know about her message comes from a poem that he wrote and that has been a source of deep fascination for intellectuals ever since. It attempts to describe an experience and a blinding insight at the very limit of what words can express – he met the goddess in a strange place at the edge of reality where he heard things that seemed impossible to refute and yet impossible to accept. His name was Parmenides. He lived around twenty-five centuries ago and came from a town called Elea on the coast of southern Italy. As for the goddess, she never gave him her name.

Western culture begins with deities and their messages to human beings. Often enough, what they had to say just reflected what people already knew or believed, but in a few rare and precious cases there is something strikingly original about it – something unheard-of, something that’s profoundly puzzling and amazing, because it challenges our common assumptions about the world and how it works. Parmenides’ poem is a major example. Strangely enough, but very significantly too, nobody agrees about what it means. The parts that we know (for some of it is lost) consist of just about 160 lines of metric Greek, and yet an enormous number of incredibly learned studies have been written about those few pages of text. Why? Because when we read them, we feel that they are important. Something is being said here that had never been said before but could perhaps be true. And yet every reader, without a single exception, has found it extremely hard to say exactly what it is.

Therefore please don’t expect me to solve the riddle either, by simply telling you in plain words what the goddess meant. I may not even be able to tell you what she said – or what Parmenides claims he had heard from her – for it is far from certain, to say the least, that her words can survive translation into modern English. To show you what I mean by this, I will focus on her most important opening statement, right at the beginning of the speech that Parmenides wrote down. What follows is just a small sample of how specialists have tried to express those Greek words in English. Prepare yourself to be surprised or perhaps disappointed, at least initially, for it may not be what you expect. The goddess is telling Parmenides that if we want to find the truth about reality, there is just one route that will lead us towards it, namely

that it is or it is not

that either a thing is or it is not

that IT IS and … IT ISN’T cannot be

that [it] is, and that [it] cannot not be

that it is and it cannot not be

that is, and is not possible not to be

[to think] that “is,” and that it is not possible not to be

that It Is, and it is not possible for Is not to be

that [it] is and that [it] is not not to be

that a thing is, and that it is not for not being

both that “is” and that “it is not the case that ‘is not’”

that it is and that it is impossible for it not to be

this, that it-is and that not-to-be is not

That’s it! (or would you say that it isn’t?!). The Greek of fragment 3.2 says ἡ μὲν ὅπως ἔστιν τε και ὡς οὐκ ἔστι μὴ εἶναι. This enigmatic, frustrating, untranslatable sentence lies at the very heart of a poem about a mysterious divine encounter that has been presented, in standard philosophy textbooks, as the opening salvo of Western logic. Although Parmenides never claimed a single philosophical insight of his own, posterity gave him all the credit for his message from the goddess. Or all the blame, for in another famous text from antiquity (possibly intended as satire) he is portrayed as some kind of hyper-logical maniac who vanishes right before the reader’s gaze into a rabbit hole of abstractions from which there can be no return.

But was it really about logic? In spite of all those disagreements about what the goddess meant, there is no doubt that she was saying something truly extraordinary. She was asking Parmenides to dismiss everything he had ever taken for granted. Literally everything – all the evidence of his senses and all the ideas in his mind. She told him that mortal humans do not see reality the way it is because our minds can’t help imagining distinctions that in fact are not there. We think that some things exist while others do not, but that is false: nothing unreal exists.

Nothing unreal exists – give yourself a few moments to let that sink in. It means that there is no such thing as unreality. Anything we ever experience is real, without a single exception, and so that has to include even what we call our illusions. I just wrote that in our imagination we draw distinctions that in fact are not there – but if this is true, it means that there’s no distinction either between illusion and reality, so even this unreal distinction itself must actually be real!

This is what she says, and the mind boggles. We can’t accept it. We think “that can’t be true, it’s such an obvious contradiction, there must be some way to resolve it!” – and so we embark on the path of logic. Without even noticing it, we take the very road that the goddess tells Parmenides to avoid. For it is precisely this path, she explains, that is taken by all those ignorant mortals who are so confused about reality that they find themselves very clever. In fact these people just wander in circles, like mindless zombies, thinking that it’s possible to have it both ways – that some things are real while some others are not, and yet that those that aren’t real are somehow real as well. Please note: the goddess doesn’t present Parmenides with a logical puzzle that he’s expected to solve (the same way that you, I’m pretty sure, are trying right now). She doesn’t engage him in dialogue. She isn’t teaching him philosophy. She is simply telling him what reality is. Strange as it might seem, the whole of Western philosophy is based on a stubborn refusal to accept her message.

The reason for those two-and-a-half thousand years of mental resistance is that the goddess’s argument could not possibly be ignored, because it made perfect rational sense. And yet it could not be accepted either, because it seemed to make no sense at all. Consider the following. Does the past exist, somewhere, somehow? Clearly it doesn’t, for it’s gone forever and we can’t go anywhere to retrieve it. Does the future exist, somewhere, somehow? Clearly it doesn’t either, for it hasn’t yet come to be. If so, then what does exist? Only this infinitesimal fleeting moment “right now” – all else will have to be just memory and expectation, mere images in our minds. And yet that cannot be true either, for if nothing unreal exists, then both what we can remember or imagine and what we can’t, although it did happen or could happen (in fact, anything that ever happened or is yet going to happen), is exactly as real as whatever we are experiencing in this moment right here and now! This can only mean that time itself is an illusion but the illusion is real.

What kind of man was Parmenides, the first human being to ever write down such thoughts, and how did he get to meet the goddess? We are told that he came from a wealthy family and was involved in the making of laws for his town, Elea. After meeting an otherwise unknown “poor but noble” man called Ameinias, he appears to have decided to pursue a life of “stillness.” They were both followers of Pythagoras, a mysterious thinker and charismatic leader who had come from the island of Samos in the Eastern Aegean to southern Italy (then known as Magna Graecia, “Great Greece,” because there were so many Greek settlements there) and had founded a contemplative tradition that remained active after his death. Pythagoras was neither a philosopher nor a scientist or mathematician, and he didn’t invent the famous theorem that carries his name – those are all later projections. He and his followers did not believe in incorporeal realities or mathematical abstractions that lead away from our world of sensual experience towards some spiritual otherworld. Instead, they were convinced that it was possible for human beings to see beyond delusion and get to know the mysterious “unmoving heart of true reality.” But such knowledge could not be attained just by thinking or logical reasoning – it could only be seen or experienced directly, as an inner revelation that could dawn upon a person who had been searching for the truth. A person like Parmenides.

So how did it happen? How did he meet the goddess? The short answer is that we do not know, but the longer answer is that we can guess. In the thrilling opening scene of his poem, Parmenides writes how he found himself rushing down “through all things” along the crowded road of the daimon Atē, the unreliable goddess of mischief, delusion and blind folly – but then he was led right up towards the other goddess, the one who would open his eyes about reality. He writes that the mares that were carrying his wheeled chariot were being guided by young maidens, servants of the goddess, “daughters of the sun” who knew the way to the gates between night and day, darkness and light, mortal ignorance and divine knowledge. In soft whispers they persuaded the gatekeeper (another female deity, known as Dikē, Justice) to open the gates and let them through. And so it is that Parmenides was kindly received by the goddess in her own home, the place of true reality.

Unlike the busy road of those who follow logic, this was not a realm filled with “many voices.” It must have been a place of profound silence, perfectly suited to the Pythagorean practice of “stillness” and deep inward contemplation. It appears that the followers of Parmenides, who remained active in Elea for many centuries after his death, used to meet in a building of their own that had a subterranean chamber – a phōleos or “dark place.” Only in such an utterly secluded location, where the senses could not be reached by stimuli that came from the outside world, could the goddess’s presence be sensed and her voice be heard. Surrounded by the nothingness of utter darkness, Parmenides may even have seen her image appear in his mind. In this place where nothing seemed to be, in fact she was everything and everywhere. This underworld place was not the place of death, she pointed out to him, for nothing exists but omnipresent life. This is reality, she was telling him. Now you know. This is it.

It has been said that humans cannot bear too much reality. Parmenides’ message from the goddess made an enormous impression on his contemporaries and on all those who came after. It was utterly new and revolutionary, impossible to ignore for anybody who heard of it and made a true effort to grasp its meaning, and yet so cryptic and impossibly weird that it forced you to keep thinking further and ever further in your attempts to figure it out. The goddess had set a ball rolling that has never stopped since. But of course, from the beginning there were those who just found it a blatant absurdity and were making fun of her One Reality. A younger Pythagorean and friend or follower of Parmenides, Zenon of Elea, responded by turning the tables on these critics: “Ah, you think that your logic is so superior? Well, watch me – what about this?” He would ask them, for instance, to consider what happens if you shoot an arrow. In order for it to reach the target, it wil first have to cover half of the distance (½), right? Right. But before getting there, it must first have covered half of that distance (¼), right? Sure thing. And yet, before ever getting there, it will first have to cover half of that distance (⅛) – or would you say it won’t? You get the point – there’s just no end to dividing any distance from A to B, and so it’s logically impossible for any arrow to ever reach any target. All movement becomes logically impossible. There have been endless attempts to solve this riddle, but Zenon’s point was that you just cannot rely on pure logic. Arrows reach their targets – that is reality. “Of course you guys can’t figure out how such a thing is possible,” Zenon was telling the critics, “but that’s because you’re wandering in logical circles along the route of confusion that the goddess told you not to take!”

How do you argue with the words of a goddess? Ever since Parmenides, all those who wanted to understand the true core of reality have found that they couldn’t avoid his poem. Whatever paths their minds were taking throught the labyrinth of human thought, sooner or later they would all find themselves back at the same place where it all began. For how could anything else exist than reality itself? Even the smartest among all those seekers (or rather, precisely the smartest) felt that perhaps they couldn’t measure up to the man from Elea. “I fear that perhaps we do not understand what he was saying…,” the brightest of them all is said to have admitted to a friend, “and still less his reasons for saying it.” Perhaps indeed.

[in memory of Demetrius Waarsenburg, 1964-2021]

Torre Velia

1 She told him to be silent…: Parmenides frgm. 2.1. … at the edge of reality: Gallop, Parmenides of Elea, 7 (“a place where opposites are undivided … where all difference or contrast has disappeared”). 2 … nobody agrees …: for the two chief schools of interpretation, see Blank, “Faith and Persuasian in Parmenides,” 167-168; Martin, Parmenides’ Vision, 1. 4 Fragm. 2.3. In chronological order: Kirk & Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers (1960), 269 (“the usual translation” and K&R’s translation); Lombardo, Parmenides and Empedocles (1982), 13; Gallop, Parmenides of Elea (1984), 55; Waterfield, The First Philosophers (2000), 58; Kingsley, Reality(2003), 60; Cordero, By Being, It Is (2004), 191; Geldard, Parmenides and the Way of Truth(2007), 23; Palmer, Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy (2009), 365; Coxon / McKirahan, Fragments of Parmenides (2009), 56; McKirahan, Philosophy before Socrates (2010), 146, 154; Blackson, Ancient Greek Philosophy (2011), 20; Martin, Parmenides’ Vision (2016), 19. 5 … another famous text …: Plato, Parmenides. … a kind of hyper-logical maniac…: I’m reminded of Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 30 “The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.” For Plato’s portrayal as a polemical satire, see e.g. Apelt, Untersuchungen; Cornford, Plato and Parmenides, v-x; Mario Molegraaf in Plato, Verzameld werk, vol. 3, 165-173; and especially Tabak, Plato’s Parmenides Reconsidered. 6 Nothing unreal exists (cf. Kingsley, Reality, 73-76 “nothing doesn’t exist”); the alternative “nothing real exists” is categorically rejected as an utter dead end (frgm. 2.5-7). … let that sink in: frgm. 6.2 (phraxesthai: Kingsley, o.c., 83 “You ponder that!”; Palmer, Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy, 369 and McKirahan, Philosophy Before Socrates, 146 “these things I bid you ponder”). 8 … the very road …: frgm. 6.4-9. … very clever …: I accept Martin’s innovative argument about the eidōs phōs in frgm. 1.3 (Parmenides’ Vision, 33-37). … have it both ways: frgm. 6.5 (dikranoi). Stubborn refusal: e.g. Gallop, Parmenides of Elea, 3 (“footnotes to Plato … footnotes to Parmenides”). 9 Consider the following… : frgm. 8.5-6; cf. McKirahan, Philosophy before Socrates, 164-166. Only this infinitesimal fleeting moment: with personal thanks to Daniel Waterman. … exactly as real: this reading confirms Kingsley’s interpretation (Reality, 69-72) of the famous frgm. 3 to gar auto noein estin te kai einai as “what exists for thinking, and being, are one and the same” (against the background of frgm. 2.2). 10 Parmenides’ life: Kirk & Raven, Presocratic Philosophers, 263-264 (Diogenes Laertius). Stillness: hēsuchia (on muēseis psuchēs, “initiations of the soul” following Iamblichus biography of Pythagoras, see Montiglio, Silence, 27-28). … neither a philosopher nor a mathematician: decisive argumentation in Burkert, Lore and Science, 208, 215, 217 (with quotation from Rohde), 278, 298, 303, 406, 466, 476, 482; for Pythagorean number symbolism as distinct from mathematics, see Burkert, o.c., 401-482; Brach, La symbolique des nombres. Theorem: Burkert, Lore and Science, 462-465; Kahn, Pythagoras, 32. Later projections: Burkert, Lore and Science, passim; also e.g. Kahn, Pythagoras, 13-15, followed by various attempts at “rescuing” Pythagoras for science and mathematics, as most extensively in Zhmud, Pythagoras, 17-18, 60 (but see e.g. Netz, Review; Macris, Review). … did not believe …: Burkert, Lore and Science, 32, 73. … unmoving heart of true reality: Parmenides frgm. 1.29 (Alētheiēs eupeitheos atremes etor). Eupeitheos (persuasive) is more common (Diels & Kranz, Fragmente, vol. 1, 230) but many editors in the wake of Diels & Kranz have followed Simplicius’ eukukleos (well-rounded; Gallop, Parmenides of Elea, 52 note 1). For alētheiēs as “reality” rather than “truth” I follow e.g. Palmer, Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy, 363, and Coxon (McKirahan), Fragments of Parmenides, 54. … seen or experienced directly …: Burkert, Lore and Science, 20-21, 424 about noein (with reference to the key discussion in von Fritz, “Νοῦς, νοεῖν,” 236-242); cf. Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 12-14 and passim. 11 “through all things”: frgm. 1.3 (pant’), and cf. 1.32 (dia pantos panta perōnta); see Martin, Parmenides' Vision, 44. I accept Martin’s ground-breaking argument in Parmenides’ Vision, 33-37: “many-voiced” must indicate that this is the noisy crowded road (the “third route” dismissed by the goddess, frgm. 6.4-9, see text) taken by all those who think they are clever but are actually under dominion of the goddess Atē, “she who blinds all” (Homer, Iliad 91.19). Diels & Kranz’ pant’ astē does not occur in any of the manuscripts (which instead have pant atē, pantatē, panta tē; Martin, Parmenides' Vision, 48). … the gates between …: concerning the much-debated question of on which side of the gates is light (day) and on which side is darkness (night) (e.g. Burkert, “Proömium,” 6-9), I suggest with Burkert that the answer must be both: the divine light of true knowledge is found in the darkness of night (e.g. Kingsley, Dark Places of Wisdom), whereas the realm of bright daylight is in fact the realm of ignorance, but the goddess’s nondualistic logic implies that true reality and human illusion (frgm. 8.50-52) are ultimately both real. See the perceptive remarks by Burkert, "Proömium," 15-16: “neither above nor below … No, Light and Night are both just superficial aspects of the one Being [des einen Seienden]; the thinker must go beyond their antagonism.” 12 … not a realm of “many voices”: ref. to frgm. 1.2., as opposed to the path of hēsuchia. … the followers of Parmenides: Ustinova, “Truth Lies at the Bottom,” 37-44; eadem, Caves, 191-209 (with further references in note 103; for phōleos, pholarchos: eadem, “Truth,” 28-33; eadem, Caves, 197-199). … the senses …: on the effects of sensory deprivation, see Sacks, Hallucinations, 34-44; for relevance to Greek antiquity, see Ustinova, Caves, 33 with note 108 and eadem, Divine Mania, 23-25. … not the place of death: frgm. 1.26 and Burkert, “Proömium,” 29: “For in Greek … the refusal of nonbeing, ouk esti mē einai, also means unambiguously: there is no death” (for the very strict Hermetic parallel, see Hanegraaff, Hermetic Spirituality, 271-275). 13 It has been said … : cf. T.S. Eliot, “Human kind / cannot bear very much reality” (Four Quartets I; in Collected Poems, 178). … impossible to ignore…: Kirk & Raven, Presocratic Philosophers, 319ff (“The Post-Parmidean Systems”). The arrow argument is part of several similar arguments concerned with motion: Kirk & Raven, o.c., 291-297. 14 “I fear that perhaps …”: Plato, Theaetetus 184a.

Apelt, Otto, Untersuchungen über den Parmenides des Plato, n.p.: Weimar 1879.

Blackson, Thomas A., Ancient Greek Philosophy: From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers, Wiley-Blackwell: Malden / Oxford 2011.

Blank David L., “Faith and Persuasion in Parmenides,” Classical Antiquity 1:2 (1982), 167-177.

Brach, Jean-Pierre, La symbolique des nombres, Presses Universitaires de France: Paris 1994.

Burkert, Walter, “Das Proömium des Parmenides und die Katabasis des Pythagoras,” Phronesis 14 (1969), 1-30.

----, Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Harvard University Press: Cambridge Mass. 1972.

Chesterton, Gilbert K., Orthodoxy, John Lane: London / New York 1909.

Cordero, Néstor-Luis, By Being, It Is: The Thesis of Parmenides, Parmenides Publishing: 2004.

Cornford, Francis MacDonald, Plato and Parmenides: Parmenides’ Way of Truth and Plato’s Parmenides translated with an Introduction and a Running Commentary, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co: London 1939.

Coxon, A.H., The Fragments of Parmenides: A Critical Text with Introduction and Translation, the Ancient Testimonia and a Commentary (orig. 1986; revised edition with new translations by Richard McKirahan, new Preface by Malcolm Schofield), Parmenides Publishing: Las Vegas / Zurich / Athens 2009.

Diels, Hermann & Walther Kranz, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, vol. 1, Weidmannsche Verlagsbuchhandlung: Berlin 1951.

Eliot, T.S., Collected Poems 1909-1962, Faber & Faber: London 1963.

Fritz, Kurt von, “Νοῦς, νοεῖν, and their Derivatives in Pre-Socratic Philosophy (Excluding Anaxagoras): Part I: From the Beginnings to Parmenides,” Classical Philology 40:4 91945), 223-242.

Gallop, David, Parmenides of Elea: Fragments, University of Toronto Press: Toronto / Buffalo / London 1984.

Geldard, Richard G., Parmenides and the Way of Truth, Monkfish: Rhinebeck 2007.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., Hermetic Spirituality and the Historical Imagination: Altered States of Knowledge in Late Antiquity, Cambridge University Press 2022.

Kahn, Charles H., Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans: A Brief History, Hackett: Indianapolis / Cambridge 2001.

Kingsley, Peter, In the Dark Places of Wisdom, Element: Shaftesbury / Boston / Melbourne 1999.

----, Reality, The Golden Sufi Center: Point Reyes, California 2003.

Kirk, G.S. & J.E. Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, At the University Press: Cambridge 1960.

Lombardo, Stanley, Parmenides and Empedocles, Wipf & Stock: Eugene, Oregon 1982.

Macris, Constantinos, Review of Leonid Zhmud, Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans, Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 1 (2014), 142-146.

Martin, Stuart B., Parmenides’ Vision: A Study of Parmenides’ Poem, University Press of America: Lanham / Boulder / New York / Toronto / Plymouth 2016.

McKirahan, Richard D., Philosophy before Socrates: An Introduction with Texts and Commentary, Hackett: Indianapolis / Cambridge 2010.

Montiglio, Silvia, Silence in the Land of Logos, Princeton University Press 2000.

Netz, Reviel, Review of Leonid Zhmud, Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans, Isis 104:3 (2013), 606-607.

Palmer, John, Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy, Oxford University Press 2009.

Plato, Verzameld Werk (Mario Molegraaf, transl.), Bert Bakker: Amsterdam 2012.

Sacks, Oliver, Hallucinations, Picador: London 2012.

Tabak, Mehmet, Plato’s Parmenides Reconsidered, Palgrave MacMillan: New York 2015.

Ustinova, Yulia, “Truth Lies at the Bottom of a Cave: Apollo Phōleutērios, the Pholarchs of the Eleats, and Subterranean Oracles,” La Parola des Passato: Rivista di Studi Antichi 59 (2004). 25-44.

----, Caves and the Ancient Greek Mind: Descending Underground in the Search for Ultimate Truth, Oxford University Press 2009.

----, Divine Mania: Alterations of Consciousness in Ancient Greece, Routledge: London / New York 2018.

Waterfield, Robin, The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists, Oxford University Press 2000.

Zhmud, Leonid, Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans, Oxford University Press 2012.

August 19, 2022

Butterflies of Freedom: in support of Salman Rushdie

Writers from across the globe are showing their solidarity with Salman Rushdie and their support of the freedom to write, by reading selected texts from his work in public and online. I would very much like to join this effort by recording my own reading of a Rushdie passage, for although I’m not a literary writer but an academic one, writing is my life and so I know what it means. But instead of reading the passage I have selected, I will simply put it here in its written form. The honest reason is that I wouldn’t be able to read it aloud in front of a camera – the writing is so beautiful and powerful that I would not be able to control my breath and my emotions. To all of you out there who think you have the right to tell others what they can or cannot write: look at what it actually is that you are trying to kill. You have already lost, for it is much stronger than you will ever be. It will easily survive you, it will survive Rushdie as well - in fact, it will survive each and every person alive who may be reading it today. You will never stop it.

From The Satanic Verses, ch. 8: “The Parting of the Arabian Sea”

On the last night of his life he heard a noise like a giant crushing a forest beneath his feet, and smelled a stench like the giant’s fart, and he realized that the tree was burning. He got out of his chair and staggered dizzily down to the garden to watch the fire, whose flames were consuming histories, memories, genealogies, purifying the earth, and coming towards him to set him free; – because the wind was blowing the fire towards the grounds of the mansion, so soon enough, soon enough, it would be his turn. He saw the tree explode into a thousand fragments, and the trunk crack, like a heart; then he turned away and reeled towards the place in the garden where Ayesha had first caught his eye; – and now he felt a slowness come upon him, a great heaviness, and he lay down on the withered dust. Before his eyes closed he felt something brushing at his lips, and saw the little cluster of butterflies struggling to enter his mouth. Then the sea poured over him, and he was in the water beside Ayesha, who had stepped miraculously out of his wife’s body … ‘Open,’ she was crying. ‘Open wide!’ Tentacles of light were flowing from her navel and he chopped at them, chopped, using the side of his hand. ‘Open,’ she screamed. ‘You’ve come this far, now do the rest.’ – How could he hear her voice? – They were under water, lost in the roaring of the sea, but he could hear her clearly, they could all hear her, that voice like a bell. ‘Open,’ she said. He closed.

He was a fortress with clanging gates. – He was drowning. – She was drowning too. He saw the water fill her mouth, heard it begin to gurgle into her lungs. Then something within him refused that, made a different choice, and at the instance that his heart broke, he opened.

His body split apart from his adam’s apple to his groin, so that she could reach deep within him, and now she was open, they all were, and at the moment of their opening the waters parted, and they walked to Mecca across the bed of the Arabian sea.

Butterflies of Immortality: in support of Salman Rushdie

Writers from across the globe are showing their solidarity with Salman Rushdie and their support of the freedom to write, by reading selected texts from his work in public and online. I would very much like to join this effort by recording my own reading of a Rushdie passage, for although I’m not a literary writer but an academic one, writing is my life and so I know what it means. But instead of reading the passage I have selected, I will simply put it here in its written form. The honest reason is that I wouldn’t be able to read it aloud in front of a camera – the writing is so beautiful and powerful that I would not be able to control my breath and my emotions. To all of you out there who think you have the right to tell others what they can or cannot write: look at what it actually is that you are trying to kill. You have already lost, for it is much stronger than you will ever be. It will easily survive you, it will survive Rushdie as well - in fact, it will survive each and every person alive who may be reading it today. You will never stop it.

From The Satanic Verses, ch. 8: “The Parting of the Arabian Sea”

On the last night of his life he heard a noise like a giant crushing a forest beneath his feet, and smelled a stench like the giant’s fart, and he realized that the tree was burning. He got out of his chair and staggered dizzily down to the garden to watch the fire, whose flames were consuming histories, memories, genealogies, purifying the earth, and coming towards him to set him free; – because the wind was blowing the fire towards the grounds of the mansion, so soon enough, soon enough, it would be his turn. He saw the tree explode into a thousand fragments, and the trunk crack, like a heart; then he turned away and reeled towards the place in the garden where Ayesha had first caught his eye; – and now he felt a slowness come upon him, a great heaviness, and he lay down on the withered dust. Before his eyes closed he felt something brushing at his lips, and saw the little cluster of butterflies struggling to enter his mouth. Then the sea poured over him, and he was in the water beside Ayesha, who had stepped miraculously out of his wife’s body … ‘Open,’ she was crying. ‘Open wide!’ Tentacles of light were flowing from her navel and he chopped at them, chopped, using the side of his hand. ‘Open,’ she screamed. ‘You’ve come this far, now do the rest.’ – How could he hear her voice? – They were under water, lost in the roaring of the sea, but he could hear her clearly, they could all hear her, that voice like a bell. ‘Open,’ she said. He closed.

He was a fortress with clanging gates. – He was drowning. – She was drowning too. He saw the water fill her mouth, heard it begin to gurgle into her lungs. Then something within him refused that, made a different choice, and at the instance that his heart broke, he opened.

His body split apart from his adam’s apple to his groin, so that she could reach deep within him, and now she was open, they all were, and at the moment of their opening the waters parted, and they walked to Mecca across the bed of the Arabian sea.

March 9, 2022

Ukrainian Diary

As the Ukraine crisis began to unfold, I found myself composing messages on my Facebook page, in an effort to gain a bit of clarity in my own mind while staying in contact with my international network of friends. We are experiencing the biggest international security crisis that I can remember from my own lifetime, and one that resonates in various somewhat complicated ways with others concerns about recent cultural and political developments about which I have been writing on this blog. It is perfectly clear to me that the geopolitical map is being redrawn at this very moment (I'm writing this introduction on 9 March), with consequences for all of us that are impossible to predict but will certainly reach very far. As correctly noted by a Dutch specialist, Caroline de Gruyter, 24 February 2022 will go down in history as the beginning of a historical transition comparable to the end of the Cold War with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. As I feel sure that these are times of world-historical importance, I've decided to copy my Facebook messages in this blog, so as to create a record of developments in the form of an ongoing diary.

I do this mainly because in the future I want to create a record of what I was thinking at this time, on a day-to-day basis without the benefit of knowing what was about to happen next. This will be an unedited diary, so it will record any mistake or misjudgment I might commit, along with any assessments that, with hindsight, might turn out to be correct. Because that's what history is all about: you don't know what's going to happen until it does.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jan van Eijck about the Ukraine Crisis (9 March)

Another article worth reading from Jan van Eijck's excellent Dutch blog "Twijfelen aan de Werkelijkheid" ("Doubting Reality"), this time about the Ukraine crisis. Again and again, Jan puts his finger at the right spot, and he also provides some very good tips for further reading.

[Dutch original:] Weer een bijzonder lezenswaardige aflevering van Jan van Eijck's onvolprezen blog "Twijfelen aan de Werkelijkheid," ditmaal natuurlijk over de Oekraïne-crisis. Jan legt de vinger steeds weer op de juiste plaats en geeft ook zeer goede tips voor verder lezen.

Shame on Aleksandr Dugin (8 March)

Chilling words by Aleksandr Dugin, who is busily cheering Putin on and clearly believes that all means are justified. This is what he writes on his FB page:"There is a little misunderstanding in US analysis of possible Russian answer to eventual direct participation of NATO in conflict - through Poland or elsewhere. US most clever experts exclude preventive nuclear strike being sure that Russia uses this ultimate weapon only in the response to previous nuclear strike of the West. They are wrong in that. We are already in different stage of conflict. For Russia it means to be or not to be. For the US certainly it is highly important but not existential. So be not so sure. We’ve crossed the border.I remind: I am (almost) always right in my analysis. Don’t try to find how. You’ll never know."Dugin has certainly crossed the border - of sanity and of humanity. This is what ideological blindness looks like. Shame on him.Footage from Charkov (7 March)

A Ukrainian friend who comes from Charkov asked me to share these photos and clips: this is what it looks like when your city is under fire. People are being killed on the streets trying to buy groceries. I know that FB and Twitter don’t work in Russia anymore, but her request to anybody who knows other ways to reach people in Russia: please share this information, so that they know what Putin’s government is doing.

[PS. This is just a small selection from the photos I posted on FB; unfortunately, the video footage cannot be shown in this blog]

So what was "the West" all about? (7 March)

I hope that this crisis will lead us to reconsider or rediscover what “the West” was supposed to be all about. It’s deeply depressing to see how many people are presently responding to Putin’s blatant aggression with litanies of all the well-known crimes and hypocrisies of which the West is guilty, suggesting that he is somehow right and his dictatorship is somehow to be preferred. Yes, the West is guilty of all those crimes - I know it all too well, there’s no need to convince me. But think about it: these feelings of disgust about “hypocrisy” come precisely from the fact that those crimes conflict so painfully with the deeply admirable and inspiring dreams and ideals that we know we should be defending but have neglected. We should have every reason to be proud of our traditions of liberalism (*not* its malicious perversion known as neoliberalism) and humanism, the dream of individual and societal freedom, the belief that all human beings without any exception are equally valuable and should have the same basic rights and opportunities, our commitment to the emancipation of minorities, our principled rejection of discrimination of any kind (whether by race, gender, or sexual orientation), the conviction that we should be able to share what is good for the benefit of all. The undeniable fact that we’ve kept making a horrible mess of these ideals should not be a reason for us to keep betraying them now, by cultivating attitudes of tolerance and understanding towards a brutal tyranny that tramples on all of them: such cynicism merely shows that we never took our own ideals seriously in the first place, or even understood what they meant. On the contrary, the fact that we’ve been messing up should inspire us to make a turnaround, to rediscover and embrace all those ideals and values that are the true heart of Western culture, to try what we can to correct the countless mistakes we have made, and make another serious attempt to finally get it right. If there has ever been an opportunity, this is it.