Wouter J. Hanegraaff's Blog, page 4

December 26, 2013

Fatima's Knight

One of the most interesting books about religion that I’ve read in recent years came from an unexpected angle. Michael Muhammad Knight’s Tripping with Allah: Islam, Drugs, and Writings is a brilliantly written and highly intelligent piece of autobiographical literature, from the pen of an author who combines deep personal involvement in Islam with an off-the-charts heretical attitude, profound familiarity with academic research and theory in the study of religion, and most of all, a truly original, independent, and passionate mind. The troubled son of a white supremacist and paranoid psychotic rapist, Knight was raised as a Roman Catholic by his mother but converted to Islam at age 16, after reading the

Autobiography of Malcolm X

. He went on to study Islam at Faisal Mosque in Islamabad, Pakistan, and came close to joining the Chechnyan war against Russia. Having become disenchanted with Islamic orthodoxy, he started experimenting with a range of alternative Muslim identities, including the

Nation of Islam

(he is fascinated by its mysterious founder Fard Muhammad) and the

Nation of Gods and Earths

, also known as the Five Percenters (who proclaim the divinity of human beings and therefore address one another, amusingly enough, as “god”). Parallel to this, he also embarked on a semi-professional wrestling career, subjecting himself to grueling training routines and diets and finally getting beaten up seriously (fifty stitches!) in a fight with a notorious wrestler named Abdullah the Butcher. Tripping with Allah(an “adventure book for academics to chew on”, p. 30) is the most recent of a series of nine volumes that document Knight’s continuing search for his personal, religious, and (not in the last place) masculine identity. Right from the outset, we encounter him at the intersection of various overlapping cultural contexts and discourses, including traditional Islam (both Sunni and Shia), the cool hip hop Muslem culture associated with the Five Percenters, Religious Studies as practiced at Harvard Divinity School, superhero video games and TV comic series such as the 1970s series Transformers, the parallel universe of American wrestling and, last but not least, the (neo)shamanic practice of drinking ayahuasca. Having heard about the spectacular visionary and healing powers of this famous psychoactive brew from the Amazon forest, Knight decided to try it – hoping perhaps to see visions of “Muhammad on a flying jaguar” (p. 4) or perhaps, far more seriously, to find a way of healing his traumas and find answers in his spiritual quest.A major theme in Tripping with Allah is the acute conflict between Knight’s quest for religious meaning and belonging, and the implications of his academic training in the study of religion. In the first chapter (“Cybertron Kids”) we find the author and his friend Zoser watching and “building” (in Knight’s delightful rendering of Five Percenters’ lingo) on an early Transformersepisode called “Dinobot Island”, in which some kind of time warp phenomenon opens up portals through which life forms from other time periods enter and start messing with our world. In Knight’s narrative, Dinobot Island becomes a metaphor for contemporary religion and the pervasive phenomenon of decontextualization in a globalized media context: for young Muslims like Zoser and himself, and whether they like it or not, Islam has essentially become a reservoir of traditional materials and stories to pick and choose from at will, and available for being combined creatively with anything else that is available, whether it’s hip hop, science fiction, wrestling, shamanism, or popular comics. In Knight’s words, “‘Muhammad’ is a superhero template, his sunnafunctioning as a How to Be the Perfect Human kit that you’ll never finish: Muhammad as M.H.M.D., or Masters His Motherfucking Devils.” (p. 9).

One of the most interesting books about religion that I’ve read in recent years came from an unexpected angle. Michael Muhammad Knight’s Tripping with Allah: Islam, Drugs, and Writings is a brilliantly written and highly intelligent piece of autobiographical literature, from the pen of an author who combines deep personal involvement in Islam with an off-the-charts heretical attitude, profound familiarity with academic research and theory in the study of religion, and most of all, a truly original, independent, and passionate mind. The troubled son of a white supremacist and paranoid psychotic rapist, Knight was raised as a Roman Catholic by his mother but converted to Islam at age 16, after reading the

Autobiography of Malcolm X

. He went on to study Islam at Faisal Mosque in Islamabad, Pakistan, and came close to joining the Chechnyan war against Russia. Having become disenchanted with Islamic orthodoxy, he started experimenting with a range of alternative Muslim identities, including the

Nation of Islam

(he is fascinated by its mysterious founder Fard Muhammad) and the

Nation of Gods and Earths

, also known as the Five Percenters (who proclaim the divinity of human beings and therefore address one another, amusingly enough, as “god”). Parallel to this, he also embarked on a semi-professional wrestling career, subjecting himself to grueling training routines and diets and finally getting beaten up seriously (fifty stitches!) in a fight with a notorious wrestler named Abdullah the Butcher. Tripping with Allah(an “adventure book for academics to chew on”, p. 30) is the most recent of a series of nine volumes that document Knight’s continuing search for his personal, religious, and (not in the last place) masculine identity. Right from the outset, we encounter him at the intersection of various overlapping cultural contexts and discourses, including traditional Islam (both Sunni and Shia), the cool hip hop Muslem culture associated with the Five Percenters, Religious Studies as practiced at Harvard Divinity School, superhero video games and TV comic series such as the 1970s series Transformers, the parallel universe of American wrestling and, last but not least, the (neo)shamanic practice of drinking ayahuasca. Having heard about the spectacular visionary and healing powers of this famous psychoactive brew from the Amazon forest, Knight decided to try it – hoping perhaps to see visions of “Muhammad on a flying jaguar” (p. 4) or perhaps, far more seriously, to find a way of healing his traumas and find answers in his spiritual quest.A major theme in Tripping with Allah is the acute conflict between Knight’s quest for religious meaning and belonging, and the implications of his academic training in the study of religion. In the first chapter (“Cybertron Kids”) we find the author and his friend Zoser watching and “building” (in Knight’s delightful rendering of Five Percenters’ lingo) on an early Transformersepisode called “Dinobot Island”, in which some kind of time warp phenomenon opens up portals through which life forms from other time periods enter and start messing with our world. In Knight’s narrative, Dinobot Island becomes a metaphor for contemporary religion and the pervasive phenomenon of decontextualization in a globalized media context: for young Muslims like Zoser and himself, and whether they like it or not, Islam has essentially become a reservoir of traditional materials and stories to pick and choose from at will, and available for being combined creatively with anything else that is available, whether it’s hip hop, science fiction, wrestling, shamanism, or popular comics. In Knight’s words, “‘Muhammad’ is a superhero template, his sunnafunctioning as a How to Be the Perfect Human kit that you’ll never finish: Muhammad as M.H.M.D., or Masters His Motherfucking Devils.” (p. 9).

And that, of course, is what the book is ultimately all about. While building up a narrative to prepare the reader for his encounter with ayahuasca, Knight offers erudite and sometimes brilliant reflections on a variety of relevant topics, such as the popular depiction of both drugs and Islam as the demonized “other” of white American identity (“Civilization Class”), the history of Islamic attitudes towards drugs, including coffee (“Islam and Equality” - “equality” being a code for hashish - ; “Coffee consciousness”), prophecy and visionary consciousness according to Avicenna and al-Ghazali (“Avicenna and the Monolith”), and the intellectual and existential dilemmas of studying religion academically at Harvard while also practicing it as a Muslim (“Jehangir Allah”, “Scholars and Martyrs”). Last but not least, there is the conflict between his emerging identity as a professional scholar of religion and the primal forces that drive him as a writer. Identifying with one of his heroes, a brutal wrestler known as “Bruiser Brody”, Knight is worried that the politically correct attitudes and pseudo-intellectual language (for some edifying examples of mindless cultural studies lingo, see pp. 134-135!) that seem to dominate American academia might finally end up killing his soul:“Two years have passed at Harvard, and now I try to picture Bruiser Brody obsessed with explaining himself, apologizing for himself, justifying his existence through the use of a larger tradition and perhaps a grounding in theory, trying to find legitimacy as a public intellectual. I see Bruiser Brody understanding himself through Roland Barthes, wearing a corduroy blazer and tying back his hair and insisting, “I’m so much more than just a psychotic chain-swinging freak, if you read me in my proper context,” dipping out of the personality game while he’s still ahead and focusing on pure scholarship from this moment on – Bruiser Brody with his forehead full of scars disappearing into the quiet soft darkness of those Widener Library stacks and never coming back out” (p. 145-146).Eventually, Knight has an intake meeting with an American member of the Brazilian Santo Daime church, which uses ayahuasca as its sacrament (“Bumblebee”; for the origins of the church, founded by a Brazilian rubber tapper after his visionary encounter with the “Queen of the Forest”, see his informative chapter “Church Fathers and Mothers”). He finally gets to drink ayahuasca at a Santo Daime meeting in a private home, but I will not spoil the book for you by describing how that experience turns out for him. Let me just note that Knight’s mind and subconscious, filled with Islamic imagery, does not match very well with the predominantly Christian Catholic setting. It is only at his third attempt, in a “Western shamanic” setting, that he has a full ayahuasca experience.

And that, of course, is what the book is ultimately all about. While building up a narrative to prepare the reader for his encounter with ayahuasca, Knight offers erudite and sometimes brilliant reflections on a variety of relevant topics, such as the popular depiction of both drugs and Islam as the demonized “other” of white American identity (“Civilization Class”), the history of Islamic attitudes towards drugs, including coffee (“Islam and Equality” - “equality” being a code for hashish - ; “Coffee consciousness”), prophecy and visionary consciousness according to Avicenna and al-Ghazali (“Avicenna and the Monolith”), and the intellectual and existential dilemmas of studying religion academically at Harvard while also practicing it as a Muslim (“Jehangir Allah”, “Scholars and Martyrs”). Last but not least, there is the conflict between his emerging identity as a professional scholar of religion and the primal forces that drive him as a writer. Identifying with one of his heroes, a brutal wrestler known as “Bruiser Brody”, Knight is worried that the politically correct attitudes and pseudo-intellectual language (for some edifying examples of mindless cultural studies lingo, see pp. 134-135!) that seem to dominate American academia might finally end up killing his soul:“Two years have passed at Harvard, and now I try to picture Bruiser Brody obsessed with explaining himself, apologizing for himself, justifying his existence through the use of a larger tradition and perhaps a grounding in theory, trying to find legitimacy as a public intellectual. I see Bruiser Brody understanding himself through Roland Barthes, wearing a corduroy blazer and tying back his hair and insisting, “I’m so much more than just a psychotic chain-swinging freak, if you read me in my proper context,” dipping out of the personality game while he’s still ahead and focusing on pure scholarship from this moment on – Bruiser Brody with his forehead full of scars disappearing into the quiet soft darkness of those Widener Library stacks and never coming back out” (p. 145-146).Eventually, Knight has an intake meeting with an American member of the Brazilian Santo Daime church, which uses ayahuasca as its sacrament (“Bumblebee”; for the origins of the church, founded by a Brazilian rubber tapper after his visionary encounter with the “Queen of the Forest”, see his informative chapter “Church Fathers and Mothers”). He finally gets to drink ayahuasca at a Santo Daime meeting in a private home, but I will not spoil the book for you by describing how that experience turns out for him. Let me just note that Knight’s mind and subconscious, filled with Islamic imagery, does not match very well with the predominantly Christian Catholic setting. It is only at his third attempt, in a “Western shamanic” setting, that he has a full ayahuasca experience.

Verbal depictions of entheogenic experience are notoriously boring, but Knight’s account is an exception to that rule. The 17thchapter of his book (“Al-Najm”, “the Stars”: see the account of Muhammad’s ecstatic ascent/descent described in the Quran, Sura 53:1-18) contains a uniquely precise, impressive, and moving description of visionary therapeutic healing through ayahuasca – more convincing and instructive than any similar account that I know from the literature. Clearly it is not enough to have a powerful experience: to bring it across requires a powerful writer as well. Again, therefore, one needs to read this in the original, but given Knight’s biography it will perhaps come as no surprise that this decisive visionary sequence was grounded in Islamic imagery and mythology and went straight for what he needed most: “Out of nowhere, the drug interrupted my book about drugs and spoke instead about broken masculinities” (p. 257). Traumatized through extreme male violence, Knight’s life had been one desperate quest for masculine role models, from the frankly demonic exemplar that had raped him into existence, through the caricatural “He Men” of American wrestling, to the supreme male superheroes of his religious imagination: Muhammad the prophet, Ali the warrior, Husayn the martyr (p. 206). But by the time he drinks ayahuasca, he seems to have reached the end of that road: “It feels like I can’t go anymore; I’m like Macho Man at the end of his run” (p. 186, referring to Randy “Macho Man” Savage, the greatest professional wrestler of the 1980s: see chapter “Macho Madness”). And so it is fitting that the divine saviour/healer and psychopomp (“guide of souls”) who meets him in his vision and shows him the source of true power is not yet another muscle man, but a woman: Fatima, the daughter of the prophet, wife of Ali, and mother of Husayn.

Verbal depictions of entheogenic experience are notoriously boring, but Knight’s account is an exception to that rule. The 17thchapter of his book (“Al-Najm”, “the Stars”: see the account of Muhammad’s ecstatic ascent/descent described in the Quran, Sura 53:1-18) contains a uniquely precise, impressive, and moving description of visionary therapeutic healing through ayahuasca – more convincing and instructive than any similar account that I know from the literature. Clearly it is not enough to have a powerful experience: to bring it across requires a powerful writer as well. Again, therefore, one needs to read this in the original, but given Knight’s biography it will perhaps come as no surprise that this decisive visionary sequence was grounded in Islamic imagery and mythology and went straight for what he needed most: “Out of nowhere, the drug interrupted my book about drugs and spoke instead about broken masculinities” (p. 257). Traumatized through extreme male violence, Knight’s life had been one desperate quest for masculine role models, from the frankly demonic exemplar that had raped him into existence, through the caricatural “He Men” of American wrestling, to the supreme male superheroes of his religious imagination: Muhammad the prophet, Ali the warrior, Husayn the martyr (p. 206). But by the time he drinks ayahuasca, he seems to have reached the end of that road: “It feels like I can’t go anymore; I’m like Macho Man at the end of his run” (p. 186, referring to Randy “Macho Man” Savage, the greatest professional wrestler of the 1980s: see chapter “Macho Madness”). And so it is fitting that the divine saviour/healer and psychopomp (“guide of souls”) who meets him in his vision and shows him the source of true power is not yet another muscle man, but a woman: Fatima, the daughter of the prophet, wife of Ali, and mother of Husayn.In an interview with Deonna Kelli Sayed, Knight remarks that his Al-Najm chapter is “possibly the most heretical, blasphemous, challenging stuff that I’ve ever written. I don’t spare any of the details”. And that is true: the visionary episodes are sexually explicit, and put an intensely personal spin on traditional Islamic myth and imagery. In other words, the entire healing process would seem to happens on Dinobot Island, through a remarkable collaboration between Santo Daime’s Queen of the Forest and the Islamic Daughter of the Prophet - bien étonnés, no doubt, de se trouver ensemble... And yet, in the same interview, Knight continues by noting that the experience “leads me to this somewhat conservative place, because where I’m at right now, I pretty much just want to read hadith all day”.

Perhaps this will prove to be just a phase in Knight’s continuing story. But then again, he might well be in the process of leaving Dinobot Island, with Fatima’s help: “You can deconstruct Islam, but at some point you have to put it back together. Get your readings grounded in something” (p. 7). In what? The answer seems clear: Knight finds it in an intensely personal experience of divinity, or gnosis, mediated or facilitated by a “tradition”, with all the stories and images that it can provide. He does not find it in the intellectual practice of Quranic exegesis, so attractive and seductive “for the boys” (p. 224, 226, 238), but in a direct encounter with divine Otherness - with a presence, in other words, that is so different from his own identity that it can speak to that identity with unquestionable power and authority. Tripping with Allah may be all about Islam, Drugs, and Writing - but first and foremost, I would suggest, it is a primary source of Islamic mysticism.

Published on December 26, 2013 06:37

November 22, 2013

Butchering the Corpus Hermeticum: Breaking News on Ficino's Pimander

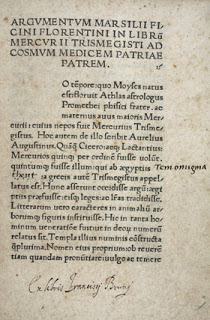

In the spring of 2002, a group of devoted Ficino aficionados met at the home of Prof. Sebastiano Gentile to discuss the need for modern critical editions of the great Florentine Platonist’s writings. One of the young scholars present at this meeting, Maurizio Campanelli, decided to take a closer look at Ficino’s famous translation of treatises I-XIV of the Corpus Hermeticum, first published in Treviso in 1471 as Hermes Trismegistus’ book on the Power and Wisdom of God (De Potestate et Sapientia Dei) but better known by its alternative title Pimander. He was in for an unexpected surprise. Although certainly no beginner in Latin anymore, he notes, ‘the number of passages of which I failed to really understand the significance followed one another at a disquieting pace’. In other words, much of the text just didn’t make sense at all. Clearly something was wrong – but what was it? Since the Greek original is perfectly comprehensible, the initial suspicion fell on Ficino himself: could it be that his famous translation, finished in 1463, had in fact been so bad as the edition would seem to suggest? But no: a crucial manuscript from 1466, heavily annotated with corrections in Ficino’s own hand, showed otherwise. Apparently the problem was with the famous Treviso edition of 1471 itself, on which the great majority of 16th-century editions would later be based.Now all of this may not seem like such a big deal to general readers. For anyone familiar with scholarship of Renaissance Hermeticism, however, the implications are far-reaching, even bordering on the sensational. Ever since Frances Yates’ Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964), countless scholars and popular authors have been telling us that the revival of the “Hermetic Tradition” began with Ficino’s Pimander of 1471, and that ever since, throughout the sixteenth century and well into the seventeenth, Hermes’s writings had become a very significant factor in the development of Renaissance religious and intellectual life. Presumably, this means that people had actually been reading Hermes’s writings. But if so, had nobody noticed that Ficino's Pimander was, in fact, an incomprehensible muddle? And if they had noticed, what had they done about it? Perhaps most importantly: was it at all possible, for such Renaissance readers, to distill the actual contents of the Hermetic writings from the translations available to them? If not, what did “Hermetism” actually mean for them? And what about all those modern scholars who have written large books and learned articles about Renaissance Hermetism? One cannot help wondering how many of them ever bothered to sit down and actually read he foundational classic of the entire tradition.

In the spring of 2002, a group of devoted Ficino aficionados met at the home of Prof. Sebastiano Gentile to discuss the need for modern critical editions of the great Florentine Platonist’s writings. One of the young scholars present at this meeting, Maurizio Campanelli, decided to take a closer look at Ficino’s famous translation of treatises I-XIV of the Corpus Hermeticum, first published in Treviso in 1471 as Hermes Trismegistus’ book on the Power and Wisdom of God (De Potestate et Sapientia Dei) but better known by its alternative title Pimander. He was in for an unexpected surprise. Although certainly no beginner in Latin anymore, he notes, ‘the number of passages of which I failed to really understand the significance followed one another at a disquieting pace’. In other words, much of the text just didn’t make sense at all. Clearly something was wrong – but what was it? Since the Greek original is perfectly comprehensible, the initial suspicion fell on Ficino himself: could it be that his famous translation, finished in 1463, had in fact been so bad as the edition would seem to suggest? But no: a crucial manuscript from 1466, heavily annotated with corrections in Ficino’s own hand, showed otherwise. Apparently the problem was with the famous Treviso edition of 1471 itself, on which the great majority of 16th-century editions would later be based.Now all of this may not seem like such a big deal to general readers. For anyone familiar with scholarship of Renaissance Hermeticism, however, the implications are far-reaching, even bordering on the sensational. Ever since Frances Yates’ Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964), countless scholars and popular authors have been telling us that the revival of the “Hermetic Tradition” began with Ficino’s Pimander of 1471, and that ever since, throughout the sixteenth century and well into the seventeenth, Hermes’s writings had become a very significant factor in the development of Renaissance religious and intellectual life. Presumably, this means that people had actually been reading Hermes’s writings. But if so, had nobody noticed that Ficino's Pimander was, in fact, an incomprehensible muddle? And if they had noticed, what had they done about it? Perhaps most importantly: was it at all possible, for such Renaissance readers, to distill the actual contents of the Hermetic writings from the translations available to them? If not, what did “Hermetism” actually mean for them? And what about all those modern scholars who have written large books and learned articles about Renaissance Hermetism? One cannot help wondering how many of them ever bothered to sit down and actually read he foundational classic of the entire tradition.

Spurred on by his initial discovery, Campanelli began working on a critical reconstruction of Ficino’s original Pimander, and the final result has been published with an Italian publisher in 2011. It is a very impressive example of painstaking philological scholarship, and a good reminder that, in the world of textual research at least, der liebe Gott lebt im Detail. So bear with me. In the first chapter of his 260-page Introduction, Campanelli analyzes Ficino’s repeated attempts at sketching a profile of Hermes Trismegistus, concluding that he was mostly trying to flatter his maecenas Cosimo de’ Medici by providing him with all the attributes of the ancient Egyptian sage, or the reverse (p. XLI, LIX). Campanelli then gets down to his real core business, analyzing all the editions of the Corpus Hermeticum that were published during the Renaissance. It is important to realize that Ficino himself never tried to get the Pimander published: the Treviso edition, published on 18 December 1471, was the unauthorized initiative of two humanists, the Flemish Geraert van der Leye (Gherardo de Lisa) and his Italian colleague Francesco Rolandello, who seems to have provided the manuscript. And it is here that something went awfully wrong, for the printed version is so corrupt that Campanelli does not hesitate to speak of an ‘authentic textual disaster’ based upon ‘scandalous negligence’ (p. CX-CXI). Most likely, according to his analysis, the printers were working under such heavy time pressure that they made countless errors, and neither van der Leye nor Rolandello ever took the trouble to check and correct the proofs… The troubling fact is that precisely this butchered version of the Pimanderbecame, nevertheless, the basis for the great majority of later editions of the Corpus Hermeticum: the 3rdone (Venice 1481), the 4th (Venice 1491), the 5th (Venice 1493), the 6th (Paris 1494), the 7th (Mainz 1503), the 8th(Paris 1505), the 10th (Venice 1516), the 12th (Lyon 1549), and the 14th (Basle 1551). This does not mean that the text remained unchanged. On the contrary: from one edition to the next, and especially since the 1494 version of Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, successive editors tried to improve the text, thus creating a wide range of variant readings of an original that had been wholly corrupt in the first place. Hence it is hardly surprising that when Gabriel du Preau was preparing his French translation (published in 1549) he admitted being ‘vexed & tormented’ by all the contradictions he discovered between the three Latin versions at his disposal (Mercure Trismegiste Hermes … de la puissance & sapience de Dieu, Introduction).

Spurred on by his initial discovery, Campanelli began working on a critical reconstruction of Ficino’s original Pimander, and the final result has been published with an Italian publisher in 2011. It is a very impressive example of painstaking philological scholarship, and a good reminder that, in the world of textual research at least, der liebe Gott lebt im Detail. So bear with me. In the first chapter of his 260-page Introduction, Campanelli analyzes Ficino’s repeated attempts at sketching a profile of Hermes Trismegistus, concluding that he was mostly trying to flatter his maecenas Cosimo de’ Medici by providing him with all the attributes of the ancient Egyptian sage, or the reverse (p. XLI, LIX). Campanelli then gets down to his real core business, analyzing all the editions of the Corpus Hermeticum that were published during the Renaissance. It is important to realize that Ficino himself never tried to get the Pimander published: the Treviso edition, published on 18 December 1471, was the unauthorized initiative of two humanists, the Flemish Geraert van der Leye (Gherardo de Lisa) and his Italian colleague Francesco Rolandello, who seems to have provided the manuscript. And it is here that something went awfully wrong, for the printed version is so corrupt that Campanelli does not hesitate to speak of an ‘authentic textual disaster’ based upon ‘scandalous negligence’ (p. CX-CXI). Most likely, according to his analysis, the printers were working under such heavy time pressure that they made countless errors, and neither van der Leye nor Rolandello ever took the trouble to check and correct the proofs… The troubling fact is that precisely this butchered version of the Pimanderbecame, nevertheless, the basis for the great majority of later editions of the Corpus Hermeticum: the 3rdone (Venice 1481), the 4th (Venice 1491), the 5th (Venice 1493), the 6th (Paris 1494), the 7th (Mainz 1503), the 8th(Paris 1505), the 10th (Venice 1516), the 12th (Lyon 1549), and the 14th (Basle 1551). This does not mean that the text remained unchanged. On the contrary: from one edition to the next, and especially since the 1494 version of Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples, successive editors tried to improve the text, thus creating a wide range of variant readings of an original that had been wholly corrupt in the first place. Hence it is hardly surprising that when Gabriel du Preau was preparing his French translation (published in 1549) he admitted being ‘vexed & tormented’ by all the contradictions he discovered between the three Latin versions at his disposal (Mercure Trismegiste Hermes … de la puissance & sapience de Dieu, Introduction).What then about the other editions, absent from the list above? The 2nd edition (Ferrara, 8th of January 1472: just a few weeks after the 1st) was based upon a separate manuscript of Ficino’s translation; but although it is much more reliable than the princeps, it seems to have remained a “stand-alone” edition without much further influence. The 9thedition (Florence 1513), edited by Mariano Tucci, was again based upon a separate manuscript of Ficino’s translation and became the basis for two later editions: the 11th (Basle 1532, edited by Michael Isengrin) and the 16th (Cracow 1585, edited by Annibale Rosselli, with huge commentaries). And finally (not counting vernacular versions such as du Preau's), we have three editions independent of Ficino’s text: the 13th Corpus Hermeticumedition in succession consists of the first publication of the Greek original by Adrien Turnèbe (Paris 1554); the 15th was a new Latin translation by François Foix de Candale (Bordeaux 1574); and finally, the 17thwas yet another new Latin translation by Francesco Patrizi (Ferrara 1591). This certainly suggests that interest in the Hermetica was growing during the second half of the sixteenth century, especially its last three decades; but Campanelli claims that, in fact, none of these three new editions had any success at all, leaving Ficino’s Pimander as ‘almost the only vehicle of the Corpus Hermeticumin Europe’ in this period (p. LXXXIII). One might want to question that point, but it seems clear that van der Leye and Rolandello (and of course their printers) created a mess that would continue to create enormous confusion about the Hermetic message throughout the sixteenth century.

Having established the history of the printed editions, Campanelli proceeds to delve deep into the ‘vast archipelago’ (p. CXXI) of surviving manuscripts of the Pimander (those that were used for the first two editions of 1471 and 1472 are no longer extant). Demonstrating great philological expertise and attention to technical detail, he finally ends up selecting fifteen manuscripts most suitable for reconstructing Ficino’s original translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, published in a meticulous critical edition on pp. 1-111 of his book. In the final chapter of his Introduction, he goes into considerable detail about the nature and quality of that translation. His conclusions are very interesting. Ficino appears to have been much concerned with improving the literary style of the Greek original, trying to make it all more elegant and beautiful. Sometimes he changes the original meaning (see esp. CCXLVIIff for what looks like intentional modifications), and his formulations tend to be far more expansive and dramatic than the wording of the Greek text (not least in cases that reflect his own hostily towards the body: p. CCXXVII). More importantly, he tends to read the Hermetic content through his own lense of Neoplatonic Christianity (p. CCXXXVII); and one can see that, understandably enough, he looks to the Latin Asclepius as a model for his own translation (p. CCXLVII).

Having established the history of the printed editions, Campanelli proceeds to delve deep into the ‘vast archipelago’ (p. CXXI) of surviving manuscripts of the Pimander (those that were used for the first two editions of 1471 and 1472 are no longer extant). Demonstrating great philological expertise and attention to technical detail, he finally ends up selecting fifteen manuscripts most suitable for reconstructing Ficino’s original translation of the Corpus Hermeticum, published in a meticulous critical edition on pp. 1-111 of his book. In the final chapter of his Introduction, he goes into considerable detail about the nature and quality of that translation. His conclusions are very interesting. Ficino appears to have been much concerned with improving the literary style of the Greek original, trying to make it all more elegant and beautiful. Sometimes he changes the original meaning (see esp. CCXLVIIff for what looks like intentional modifications), and his formulations tend to be far more expansive and dramatic than the wording of the Greek text (not least in cases that reflect his own hostily towards the body: p. CCXXVII). More importantly, he tends to read the Hermetic content through his own lense of Neoplatonic Christianity (p. CCXXXVII); and one can see that, understandably enough, he looks to the Latin Asclepius as a model for his own translation (p. CCXLVII). In conclusion, even the most reliable version of Ficino's Pimander turns out to have been quite different from what we find in the Greek manuscript that had been brought to Florence by Leonardo da Pistoia (p. CCL). But what really messed up things for the thrice-greatest was the famous 1471 edition. In the wake of that disaster, and as the number of editions increased, the original meaning of the Corpus Hermeticum was bound to get buried under an ever-expanding number of mistranslations, misinterpretations, and well-meaning but counterproductive emendations. Hence, what we have is a lively Renaissance discourse about Hermes, but no Hermetic Tradition.

Published on November 22, 2013 08:53

October 17, 2013

Of Essences and Energies

For some reason I am fascinated (dare I say “obsessed”?) by the history of the conflict between “paganism” and Christanity. Some years ago, when I discovered Gore Vidal’s novel about the 4th century pagan emperor Julian and his battle with the “Galileans,” I just couldn’t put the book out of my hands. This summer, sitting in the sun on my balcony and playing with my cats, I experienced a similar sense of excitement and fascination while reading a brandnew monograph about paganism and Christianity in the late Byzantine Empire. Niketas Siniossoglou’s

Radical Platonism in Byzantium

(Cambridge University Press 2011) is a provocative analysis of the Platonist philosopher / closet pagan George Gemistos Plethon and his battle with the Hesychast orthodoxy associated with Gregory Palamas. According to the Hesychast tradition, human beings are able to experience God’s “energies” in the world but not his ineffable “essence,” which exists beyond the boundary of Nature or the sphere of Being. The “supra-essential,” uncreated Light of the godhead could, nevertheless, be experienced in one’s heart and seen with one’s eyes, through radical psychophysical experiences of illumination (modeled after the experience of Jesus’ three apostles on Mount Thabor) that were supposed to be given by God’s grace in response to intense practice of spiritual techniques such as respiration control, concentration, uninterrupted prayer, and invocations of the name of Jesus. Siniossoglou argues that this perspective clashed with a hidden tradition of Platonic paganism that had been present in Byzantium for centuries and culminated in the writings of Plethon. Hesychasts aspired to a bodilyexperience of “entering within the uncreated light, seeing light and becoming light by divine grace” (p. 95), whereas Platonists aspired to “intellectual union with the divine, that is to say, the ecstatic ascent of the intellectual part of man alone, a process coinciding with the separation of soul and body (psychanodia)” (ibid.). The Hesychast attempt to keep Creator and Creation apart by distinguishing God’s uncreated essence from his energies was unacceptable for “pagan” Platonists: God’s energies could not be separate from his essence, and hence God could not transcend the sphere of Being but somehow had to be part of it. As such, he was not above nature, and his very essence should be accessible by the human mind or intellect in a state of “rational” ecstatic contemplation. In short, God could be known by the human mind’s natural faculties, whereas the Hesychasts claimed that God’s radically unknowable essence could only be experienced in a sensual but non-rational fashion through divine grace.

For some reason I am fascinated (dare I say “obsessed”?) by the history of the conflict between “paganism” and Christanity. Some years ago, when I discovered Gore Vidal’s novel about the 4th century pagan emperor Julian and his battle with the “Galileans,” I just couldn’t put the book out of my hands. This summer, sitting in the sun on my balcony and playing with my cats, I experienced a similar sense of excitement and fascination while reading a brandnew monograph about paganism and Christianity in the late Byzantine Empire. Niketas Siniossoglou’s

Radical Platonism in Byzantium

(Cambridge University Press 2011) is a provocative analysis of the Platonist philosopher / closet pagan George Gemistos Plethon and his battle with the Hesychast orthodoxy associated with Gregory Palamas. According to the Hesychast tradition, human beings are able to experience God’s “energies” in the world but not his ineffable “essence,” which exists beyond the boundary of Nature or the sphere of Being. The “supra-essential,” uncreated Light of the godhead could, nevertheless, be experienced in one’s heart and seen with one’s eyes, through radical psychophysical experiences of illumination (modeled after the experience of Jesus’ three apostles on Mount Thabor) that were supposed to be given by God’s grace in response to intense practice of spiritual techniques such as respiration control, concentration, uninterrupted prayer, and invocations of the name of Jesus. Siniossoglou argues that this perspective clashed with a hidden tradition of Platonic paganism that had been present in Byzantium for centuries and culminated in the writings of Plethon. Hesychasts aspired to a bodilyexperience of “entering within the uncreated light, seeing light and becoming light by divine grace” (p. 95), whereas Platonists aspired to “intellectual union with the divine, that is to say, the ecstatic ascent of the intellectual part of man alone, a process coinciding with the separation of soul and body (psychanodia)” (ibid.). The Hesychast attempt to keep Creator and Creation apart by distinguishing God’s uncreated essence from his energies was unacceptable for “pagan” Platonists: God’s energies could not be separate from his essence, and hence God could not transcend the sphere of Being but somehow had to be part of it. As such, he was not above nature, and his very essence should be accessible by the human mind or intellect in a state of “rational” ecstatic contemplation. In short, God could be known by the human mind’s natural faculties, whereas the Hesychasts claimed that God’s radically unknowable essence could only be experienced in a sensual but non-rational fashion through divine grace. But is this distinction between Hesychast Christianity and Platonic Paganism really as sharp as Siniossoglou wants us to believe? Let me emphasize how much I admire the deep learning, penetrating intelligence, and profound analysis that is evident on every page of his book – not to mention the fact, of which I’m very much aware, that Siniossoglou’s knowledge in these domains is vastly superior to my own. The problems that I see do not have to do with his unquestionable expertise but, rather, with the intellectual background agenda that informs his analysis. It seems to consist of two parts: essentialism and rationalism. To begin with the first: surprisingly, and quite courageously given the prevailing climate in academic research, Siniossoglou argues with great passion, throughout his book, for a return to essentialism in the practice of intellectual history (p. xi, and passim): rather than blurring the boundaries between “Christianity” and “paganism,” we are asked to recognize them as “trans-historical paradigms” (p. xi) that ultimately cannot be mixed or combined because each of them answers to an intrinsically different internal logic. And secondly, Siniossoglou sees the paradigm of “Christianity” (here represented by Hesychast mysticism) as ultimately grounded in irrational attitudes and bizarre claims of experiential phenomena without serious epistemological import, whereas the paradigm of “paganism” reflects the kind of rational attitude that would ultimately lead to “modern epistemological optimism and utopianism” (p. x) and anticipates Spinoza and the Enlightenment (see the Epilogue, pp. 418-426). Siniossoglou appears to think in terms of mutually exclusive binary opposites: it’s either essentialism or historicism (although admittedly he doesn’t use that term), either Christianity or paganism, either rationality or irrationality, and so on. As regards both his “essentialist” and his “rationalist” agenda, I would argue that this leads him to overlook the possibility of intermediary “third term” options. He is right that a methodology of extreme historicist relativism will ultimately leave us blind to fundamental deep structures and categorical distinctions that are at work in intellectual history; but on the other hand, if we take essentialism to an extreme, we end up with no more than theoretical abstractions divorced from historical reality and its messy complexities. To be honest, I suspect that Siniossoglou is too good a historian to be really the essentialist he professes to be: his actual approach seems quite compatible with the kind of history of ideas, or intellectual history, associated with Arthur O. Lovejoy's methodology, which manages to avoid both horns of the dilemma (for my basic line of argument in that regard, see this article, especially pp. 2-3 and 19). In short, Siniossoglou’s basic point is well taken, but I do not think he needs essentialist approaches to make it. As regards his rationalist agenda, I would question the double assumption that Hesychast mysticism had nothing to do with “knowledge” (because it was “irrational”) while Pagan/Platonic philosophy had nothing to do with “mysticism” (because it was “rational”). This simple opposition seems a projection of post-18th century Enlightenment assumptions back onto late medieval intellectual culture. Siniossoglou is certainly right in emphasizing that Plethon’s monist worldview left no room for a “super-essential” divine essence separate from Being, with the implication that human beings are not dependent on divine grace but possess an inborn, natural ability for gaining higher or absolute knowledge. But I’m not so convinced that this “epistemological optimism” is necessary “rational” in a sense that is reminiscent of Spinoza or the Enlightenment. We are dealing here with some form of ecstatic contemplation more akin to Platonic manía, as admitted by Siniossoglou himself. As an alternative to both Christian “faith” and philosophical “reason,” I would range it under a third category that could be referred to as “gnosis.”

But is this distinction between Hesychast Christianity and Platonic Paganism really as sharp as Siniossoglou wants us to believe? Let me emphasize how much I admire the deep learning, penetrating intelligence, and profound analysis that is evident on every page of his book – not to mention the fact, of which I’m very much aware, that Siniossoglou’s knowledge in these domains is vastly superior to my own. The problems that I see do not have to do with his unquestionable expertise but, rather, with the intellectual background agenda that informs his analysis. It seems to consist of two parts: essentialism and rationalism. To begin with the first: surprisingly, and quite courageously given the prevailing climate in academic research, Siniossoglou argues with great passion, throughout his book, for a return to essentialism in the practice of intellectual history (p. xi, and passim): rather than blurring the boundaries between “Christianity” and “paganism,” we are asked to recognize them as “trans-historical paradigms” (p. xi) that ultimately cannot be mixed or combined because each of them answers to an intrinsically different internal logic. And secondly, Siniossoglou sees the paradigm of “Christianity” (here represented by Hesychast mysticism) as ultimately grounded in irrational attitudes and bizarre claims of experiential phenomena without serious epistemological import, whereas the paradigm of “paganism” reflects the kind of rational attitude that would ultimately lead to “modern epistemological optimism and utopianism” (p. x) and anticipates Spinoza and the Enlightenment (see the Epilogue, pp. 418-426). Siniossoglou appears to think in terms of mutually exclusive binary opposites: it’s either essentialism or historicism (although admittedly he doesn’t use that term), either Christianity or paganism, either rationality or irrationality, and so on. As regards both his “essentialist” and his “rationalist” agenda, I would argue that this leads him to overlook the possibility of intermediary “third term” options. He is right that a methodology of extreme historicist relativism will ultimately leave us blind to fundamental deep structures and categorical distinctions that are at work in intellectual history; but on the other hand, if we take essentialism to an extreme, we end up with no more than theoretical abstractions divorced from historical reality and its messy complexities. To be honest, I suspect that Siniossoglou is too good a historian to be really the essentialist he professes to be: his actual approach seems quite compatible with the kind of history of ideas, or intellectual history, associated with Arthur O. Lovejoy's methodology, which manages to avoid both horns of the dilemma (for my basic line of argument in that regard, see this article, especially pp. 2-3 and 19). In short, Siniossoglou’s basic point is well taken, but I do not think he needs essentialist approaches to make it. As regards his rationalist agenda, I would question the double assumption that Hesychast mysticism had nothing to do with “knowledge” (because it was “irrational”) while Pagan/Platonic philosophy had nothing to do with “mysticism” (because it was “rational”). This simple opposition seems a projection of post-18th century Enlightenment assumptions back onto late medieval intellectual culture. Siniossoglou is certainly right in emphasizing that Plethon’s monist worldview left no room for a “super-essential” divine essence separate from Being, with the implication that human beings are not dependent on divine grace but possess an inborn, natural ability for gaining higher or absolute knowledge. But I’m not so convinced that this “epistemological optimism” is necessary “rational” in a sense that is reminiscent of Spinoza or the Enlightenment. We are dealing here with some form of ecstatic contemplation more akin to Platonic manía, as admitted by Siniossoglou himself. As an alternative to both Christian “faith” and philosophical “reason,” I would range it under a third category that could be referred to as “gnosis.”

Given his agenda of highlighting Plethon’s rationalism, it comes as no surprise that Siniossoglou seeks to downplay the relevance of authors such as Suhrawardi, who has often been mentioned as a background influence on Plethon, but who claimed that the Platonic quest culminated in visions that sound peculiarly similar to those of… the Hesychasts: “let [the philosopher] engage in mystical disciplines … that perchance he will, as one dazzled by the thunderbolt, see the light blazing in the Kingdom of Power and will witness the heavenly essences and lights that Hermes and Plato beheld” (Suhrawardi,

The Philosophy of Illumination

, Walbridge & Ziai ed. [1999], 107-108). Again, it would seem to be the same rationalist agenda, combined with his essentialist methodology, that forces Siniossoglou to conclude that many later Platonists, such as Proclus, were not reallyPlatonic, and not really “pagan” either! Their “introvert, defeatist and passive late antiquity Neoplatonism bordering on obscurantism” (p. 191) is, again, too close to Hesychasm for his taste, and too different from his idealized picture of a wholly rational Plato. Of course, Siniossoglou knows that there’s a different side to Plato as well, which would seem to imply “that man’s intellectual resources are not sufficient to know ‘the divine and lofty things’ but require ‘some sort of inspiration’ (ἐπίπνοια) that will illumine him and uplift him to that high level” (p. 177). Apparently, however, he seems prepared to draw the conclusion that whenever he falls short of the rationalist ideal, even Plato himself is not “really” a Platonist… Be that as it may, and regardless of what one may think of its essentialist and rationalist subtexts, Radical Platonism in Byzantium is an eye-opener that deserves to be read and re-read. Apart from Plethon and Palamas, it introduced me to a whole range of deeply intriguing thinkers whose very names I had never heard before, let alone that I knew anything of their work or their ideas. If realizing the extent of one’s ignorance is the beginning of wisdom, then this book is for anyone who aspires to become wise.

Given his agenda of highlighting Plethon’s rationalism, it comes as no surprise that Siniossoglou seeks to downplay the relevance of authors such as Suhrawardi, who has often been mentioned as a background influence on Plethon, but who claimed that the Platonic quest culminated in visions that sound peculiarly similar to those of… the Hesychasts: “let [the philosopher] engage in mystical disciplines … that perchance he will, as one dazzled by the thunderbolt, see the light blazing in the Kingdom of Power and will witness the heavenly essences and lights that Hermes and Plato beheld” (Suhrawardi,

The Philosophy of Illumination

, Walbridge & Ziai ed. [1999], 107-108). Again, it would seem to be the same rationalist agenda, combined with his essentialist methodology, that forces Siniossoglou to conclude that many later Platonists, such as Proclus, were not reallyPlatonic, and not really “pagan” either! Their “introvert, defeatist and passive late antiquity Neoplatonism bordering on obscurantism” (p. 191) is, again, too close to Hesychasm for his taste, and too different from his idealized picture of a wholly rational Plato. Of course, Siniossoglou knows that there’s a different side to Plato as well, which would seem to imply “that man’s intellectual resources are not sufficient to know ‘the divine and lofty things’ but require ‘some sort of inspiration’ (ἐπίπνοια) that will illumine him and uplift him to that high level” (p. 177). Apparently, however, he seems prepared to draw the conclusion that whenever he falls short of the rationalist ideal, even Plato himself is not “really” a Platonist… Be that as it may, and regardless of what one may think of its essentialist and rationalist subtexts, Radical Platonism in Byzantium is an eye-opener that deserves to be read and re-read. Apart from Plethon and Palamas, it introduced me to a whole range of deeply intriguing thinkers whose very names I had never heard before, let alone that I knew anything of their work or their ideas. If realizing the extent of one’s ignorance is the beginning of wisdom, then this book is for anyone who aspires to become wise.

Published on October 17, 2013 12:15

June 21, 2013

Alt & Neumann on Hermetismus

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-fareast-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} @page Section1 {size:595.0pt 842.0pt; margin:70.85pt 70.85pt 70.85pt 70.85pt; mso-header-margin:35.4pt; mso-footer-margin:35.4pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style> <br /><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-FYOsurz4MCk..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; float: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-FYOsurz4MCk..." height="320" width="246" /></a></div><div class="MsoNormal">There is a popular stereotype about academics: they spend far too much of their time bickering endlessly about the meaning of terms. Shouldn’t they better dispense with such tedious foreplay and get straight on to their real business, addressing the topics <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">themselves</i>that they are supposed to be studying? It is not so easy to explain to non-academics that this is a naïve request, because those topics themselves are often not there in the first place, but are constructed by the very discourse in which they are being discussed. Take “Hermeticism”, or “the Hermetic Tradition”. Are we thinking here only of the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> and its commentaries, or do we also mean to include a whole range of alchemical writings attributed to the legendary author Hermes Trismegistus? Is such authorship essential for something to be “Hermetic”, or do we assume that since alchemy is known universally as “the Hermetic art”, Hermes does not even need to be mentioned? But if so, do alchemy and the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> really have that much in common, apart from the name? If so, what is it that they have in common? And what do we do with texts about astrology or natural magic attributed to the Thrice Greatest? Do they suddenly become “Hermetic” too, just because of that attribution, while texts with perfectly similar contents that happen to be attributed to some other author are not? That seems quite arbitrary. But then again, if we conclude that therefore we do <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">not</i>need a reference to Hermes to call something “Hermetic”, then what <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">do</i> we need in order to do so? Presumably something that all of these texts and traditions have in common, setting them apart from all others. But imagine that we will manage to establish some such common features (by which criteria? established by whom? why? with which arguments?), then will we still have any reason to call those common denominators “Hermetic” at all? </div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><a href="http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-zdBbEpTlcRM..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; float: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-zdBbEpTlcRM..." height="320" width="210" /></a></div><div class="MsoNormal">And so on, and so forth… I’m afraid that such a seemingly endless string of questions will only add more fuel to the already dim view that outsiders tend to have of academic discourse. And yet we really have no other choice than to deal with these terminological issues seriously. While reading a recent book by Peter-André Alt, <a href="http://www.v-r.de/de/title-0-0/imagin... Geheimwissen: Untersuchungen zum Hermetismus in literarischen Texten der frühen Neuzeit </a>[Imaginary Secret Knowledge: Studies of Hermetism in Early Modern Literary Texts], I was reminded that the problem gets complicated even further by the contingencies of how scholarly traditions have developed in different disciplines as well as in different countries and linguistic domains. In anglo-saxon research, the legacy of Frances A. Yates is absolutely unavoidable even for scholars (like myself) who disagree with almost everything she said; but for some reason, Yates’ seminal <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition</i> (1964) never got translated into German, and neither the book nor all the discussions around it seem to have had much impact on the German debate. An entirely different scholarly tradition has emerged here in the field of literature instead, with entirely different arguments and assumptions, strongly influenced in this case by the pioneering work of <a href="http://www.degruyter.com/view/serial/... Kemper</a> – who never got translated either, and remains almost unknown to non-German scholars. As a result, instead of an international scholarly debate about “Hermeticism” we have a series of local networks that hardly care to listen to what the others have to say. In the Humanities at least, this kind of provincialism is much more widespread than we might think: the Germans read German, the French read French, the Italians read Italian, the Russians read Russian, and so on – and none of them gets read by the English-speaking world. Of course I’m exaggerating a bit for the sake of argument, but the pattern is a real one. <span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></div><div class="MsoNormal">In discussing how he plans to use the term <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Hermetismus</i> in his book, Peter-André Alt, too, appears to think entirely in terms of German academic discourse. He takes his cue mostly from Hans-Georg Kemper and Wilhelm Kühlmann (p. 13, 15), both of them very impressive scholars whose work would deserve to be much better known beyond the German domain. Now Kühlmann appears to understand <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Hermetismus</i> in a very broad sense, as including more or less everything that tends to be discussed in current English-language research under the label of early modern “esotericism” (see his programmatic article ‘Der “Hermetismus” als literarische Formation: Grundzüge seiner Rezeption in Deutschland’, <a href="http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/scipo... style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Scientia Poetica</i></a> 3 [1999], 145-157), but Alt rejects that terminology because he finds it anachronistic. While he expresses some objections to my way of approaching the problems of definition and categorization, I suspect that my recent work (<a href="http://www.cambridge.org/us/knowledge... style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Esotericism and the Academy</i></a>, published in the same year as Alt’s book and hence not accessible to him at the time) might perhaps put some of them to rest. Be that as it may, I think that Alt’s resistance against the “esotericism” label has to do not only with a (quite justified) fear of anachronistic reasoning, but at least as much with the simple fact that his own field of specialization is restricted to the early modern period. As a result, he and his colleagues do not need to bother about the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">longue durée</i> of the traditions they study, and can dispense with the problem of finding a term that covers all of it. In a solid discussion written by Alt in collaboration with Volkhard Wels, published in a multi-author companion volume <a href="http://www.v-r.de/de/title-0-0/konzep... des Hermetismus in der Literatur der Frühen Neuzeit</a>(2010), this point is acknowledged explicitly (p. 8).</div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><a href="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-LwIxYuAq1AQ..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; float: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-LwIxYuAq1AQ..." height="213" width="320" /></a></div><div class="MsoNormal">What then is Alt’s approach? On the one hand, he wants to use a much more restrictive and precise definition of <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Hermetismus</i> than Kühlmann: he emphasizes repeatedly that his book will be grounded in ‘a determination of Hermetism based on exact source-philological criteria … based strictly on the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> and its topoi’ (p. 21). On the face of it, then, his book will be concerned exclusively with the reception history of the C.H. in early modern literary texts. The reception of alchemical materials, including the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Tabula Smaragdina</i>, is strictly excluded (p. 21). However, it would seem that this ambition of applying great philological/source-critical rigour suffers shipwreck immediately, for a simple reason: it just so happens, Alt points out, that we rarely find any ‘direct textual references’ to the C.H. in early modern literature at all (p. 16)! Instead, we are seldom dealing with more than indirect ‘allusions [<i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Anspielungen</i>] and the hidden use of central patterns of argumentation’ (pp. 16-17, cf. 23). If this is the case, then doesn’t it make Alt’s apparently so severe program of a <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">quellenphilologisch exakte Bestimmung des Hermetismus</i> (p. 21) impossible from the outset? It would seem hard to draw any other conclusion, until one realizes that Alt has opened a narrow escape route in the final words of the quotation given above: ‘… based strictly on the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> <b style="mso-bidi-font-weight: normal;">and its topoi</b>’. </div><div class="MsoNormal">So what are those topoi? Alt first mentions three criteria of what he, for reasons best known to himself, considers to be particularly “Hermetic” (the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">logos</i>doctrine, the central function of <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">inspiration</i>, and the special importance of <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">doxa</i>transmitted from teacher to pupil [21]), and continues by mentioning some ‘specifically literary topoi through which Hermetic traces are passed on: to these belong secrecy, reading the Book of Nature, androgyny, the self-reflection of poetic production or the brooding silence of melancholy’ (p. 23). Judging from such a description, I find it hard to avoid the conclusion that Kühlmann’s wide and inclusive understanding of <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Hermetismus</i> has silently returned through the back door. For if all these “topoi” are supposed to be “Hermetic” – but unfortunately, Alt never explains <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">what</i> it is that makes them “Hermetic”, or in what sense –, then the term <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Hermetismus</i>becomes so vague and all-encompassing as to be virtually meaningless. In short, I’m afraid that Alt’s laudable project of a <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">quellenphilologisch exakte Bestimmung</i> based strictly on the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> vanishes into thin air even before it is put to the test.</div><div class="MsoNormal">In some other respects, too, the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">quellenphilologische</i> foundations are less secure than one might think at first sight. I would not dare to question Alt’s expertise in early modern German literature, in which he undoubtedly knows his business, but it must be said that his knowledge of the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> and its early modern reception is rather flimsy, and the same goes for his familiarity with non-German scholarship in this domain. Amazingly, Alt never seems to have noticed that the C.H. consists not of ‘insgesamt 18 Traktate’ (p. 25, 26, 27) but of only seventeen (the first editor of the Greek text, Adrien Turnèbe, created a fifteenth treatise out of some Hermetic excerpts from Stobaeus, but this was seen as artificial by later editors, who left it out again but kept the numbering: hence the absence of a C.H. XV). And although Lodovico Lazzarelli (the translator of the final three treatises of the C.H., not included in Ficino’s <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Pimander</i>) figures prominently in the very title of Alt’s Chapter 2, it seems that all he knows about this figure – who is in fact crucial when it comes to the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">quellenphilologische</i> foundations of Renaissance Hermetism – is taken indirectly from Hanns-Peter Neumann’s problematic review (in <a href="http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/scipo... Poetica</i> </a>12 [2008], 315-322) of <a href="http://acmrs.org/publications/catalog... main contemporary monograph on Lazzarelli</a>, published by yours truly in collaboration with Ruud Bouthoorn in 2005. I really need to set the record straight here, for almost everything that Alt writes about Lazzarelli and my own work is wrong. </div><div class="MsoNormal">Most of Alt's mistakes have their origin in Neumann himself, who, for reasons unknown to me, seemed determined to present our book on Lazzarelli in the most negative light possible. Sitting on a very high horse, he complained first of all about the ‘Lässigkeit und Mangelhaftigheit’ of our ‘incomplete and partly incorrect’ bibliography (p. 318). What was the problem? Well, we appear to have overlooked one title: Alselm Stoeckel’s 1582 edition of Lazzarelli’s <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Crater Hermetis</i> (attached to his<a href="http://dfg-viewer.de/show/?set[mets]=... <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Epithalamion</i></a> and therefore easy to miss). There is no reason, however, why we should have mentioned all the later reprints of Lefèvre d’Étaples’ famous 1505 edition, although Neumann thinks we should; and most importantly, before accusing us of a mistake as elementary as getting the date of Gabriel du Preau’s French translation wrong, he should have taken the trouble to consult the book itself. It was first published in <a href="http://books.google.nl/books/about/Me..., exactly as indicated in our bibliography, and not in <a href="http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6... as claimed by Neumann on the basis of the French National Library Catalogue. So much for the ‘Lässigheit und Mangelhaftigkeit’ of our bibliography, which then inspires Neumann to express doubts about the quality of our translations as well (but what is the connection?) only to end up concluding, apparently to his surprise, that those doubts are unfounded and we do know our Latin after all... As for Lazzarelli’s <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> translation, known as the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Diffinitiones Asclepii</i>, Neumann’s knowledge of it does not reach as far as the information that, as already noted above, it contains no C.H. XV (p. 316, 319); and if he had read our sloppy and faulty bibliography a bit better, he would have known that the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Diffinitiones</i> were published by C. Vasoli in E. Castelli's <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Umanesimo e esoterismo</i> in 1960. Hence his claim that we have failed to grasp the chance of ‘doing pioneering work’ on these translations (p. 319) rests on nothing. Not a word of appreciation, by the way, about the series of critical editions and annotated translations of previously unavailable texts, including several manuscripts, that we <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">did</i>publish in our book.</div><div class="MsoNormal">Incompetent reviews [sometimes written by competent scholars, as happens to be the case here] are a fact of academic life, and are better ignored in most cases. They become a problem if renowned scholars take them seriously, and rely on them in lieu of reading the book itself, particularly if this happens in a monograph. Unfortunately, such is the case here. A relatively minor issue is that Neumann and Alt both present me as ignoring the “neoplatonic” nature of the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i> while attributing neoplatonic interpretations only to Ficino (Neumann p. 320; Alt p. 26 nt 39): in doing so, they seem to conflate the well-known <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">middle</i>-Platonic backgrounds of the C.H. with properly <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">neo</i>-Platonic interpretations in the wake of Plotinus. More serious is Alt’s completely incorrect claim that Lazzarelli’s <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Crater</i>is about ‘the idea of transmigration’ (Alt p. 26), <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">quod non</i>, or his misleading description of Lazzarelli as ‘a pupil of the alchemist Giovanni da Correggio’ (it is only at a very late stage that both men seem to have developed an interest in pseudo-Lullian alchemy: Correggio was essentially a wandering apocalyptic prophet and miracle man). In fact, these few mistaken statements are all that we get to read about Lazzarelli at all. Nothing indicates that Alt ever read our book, and hence he misses quite some information that could actually have been useful to some of his later arguments, for instance about Poimandres as the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Logos</i>(cf. pp. 30-31).</div><div class="MsoNormal">I prefer not to go into detail about a range of further statements, later on in the same chapter, about the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Corpus Hermeticum</i>and its contents: this blogpost is already getting far too long. The points I have been trying to make are simple. Firstly: Hermeticism is an extremely complicated topic, both historically and conceptually, and the <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">sine qua non</i>in writing about it consists in careful study of the primary sources in their original languages together with equally careful study of the secondary sources in <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">their</i> original languages. And secondly: the imperative of always going <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">ad fontes</i> pertains not only to the former category, but to the latter as well. <span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></div>

Published on June 21, 2013 07:54

Wouter J. Hanegraaff's Blog

- Wouter J. Hanegraaff's profile

- 91 followers

Wouter J. Hanegraaff isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.