Wouter J. Hanegraaff's Blog, page 2

September 25, 2020

Enter: The Gods (interview)

On February 28 this year, just before the the Corona wave hit us, I gave a keynote lecture at the international workshop "Religious Drugs" at the Department for the Study of Religions of Masaryk University, Brno. During the conference I was interviewed by Jana Nenadalova for the journal Legalizace, and the interview was published in Czech translation. Below you find the English version.

* * * * *

With a Dutch expert on alternative spirituality, we moved from ancient Egypt to the Amazon rainforests to discuss changes in consciousness, experiences of divinity and the meaning of life.

J: Your speech yesterday was really interesting. Can you recap some of its main thoughts, and perhaps explain what you mean by entheogenic experience?

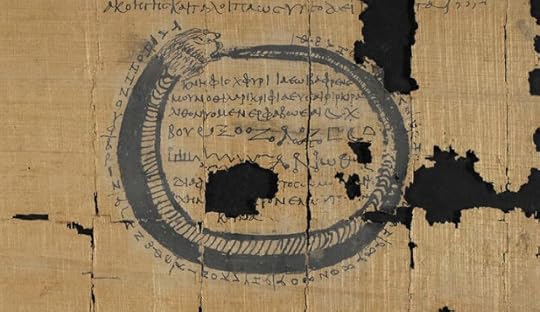

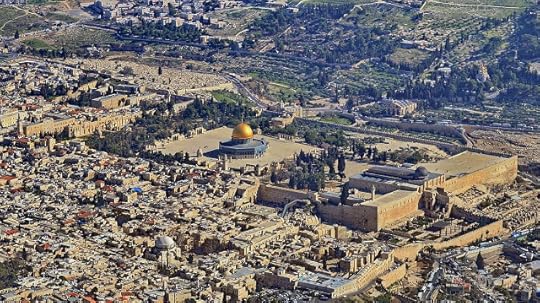

H: Well, basically I tried to connect two phenomena with each other. My speech was focused on Roman Egypt – Egypt under the dominion of the Romans, in the first centuries of the common era. This whole culture, and a lot of its practices, especially the religious ones, have often been interpreted by scholars as “magic.” And I’ve discussed some examples from the so-called “Greek Magical Papyri.” These were edited by a German scholar, Karl Preisendanz, who also gave them that title. He interpreted everything as “magic” because that’s how he looked at ancient Egyptian religion: it was all “magic” in his eyes, which for him was just another word for “superstition.” It’s quite important to realize that when a text just spoke of “visions,” he wrote “magical visions,” “plants” became “magical plants,” and so on. Why? Because the word “magic” had negative connotations that fit quite well with dominant stereotypes of Egypt, which stood for all that irrational, superstitious stuff that could be nicely opposed to Enlightenment rationality and science. I see this as an extremely biased way of looking at that type of Egyptian religious practice. Many of these texts describe strange visions, encounters with gods, and all kind of things that wouldn’t normally happen to people in their normal mind. As a result, many scholars have thought “well, doesn’t that prove then how irrational and superstitious these people were? They must either have made it all up, or if it really happened to them, then they must have been crazy, out of their minds.”

So in my lecture I focused on a specific case, a famous text that is known as the “Mithras Liturgy.” If you look closely enough, then you have to conclude that the use of entheogenic substances played a rather important role in what is described there. And if that is the case, then you don’t have to assume that these people were crazy – quite the contrary, you have a perfectly rational explanation for what happened to them. After all, we know from clinical evidence that if you take a perfectly healthy individual and give him LSD, he will have very strange visions and experiences. He is not crazy, he is just having a hallucinogenic experience. Looking closely at the sources, for instance you find a specific kind of incense, kyphi, that had mild but well-attested narcotic properties and was used all over Egypt. But the specific case of the “Mithras Liturgy” goes much further, and may be considered one of the most important “trip reports” that we have from late antiquity. It describes a really spectacular visionary sequence and includes the detailed recipe for making an “eye paint” that you need to rub in or around your eyes to have such visions. It contains several components that are known to be psychoactive.

J: Can you mention them?

H: Of course. It includes the blue lotus, which was common in Egypt, has been analyzed and turns out to have hallucinogenic properties; the same goes for myrrh; and then there is a question about the Sun scarab, which also goes into the recipe. This part is more speculative so I wouldn’t insist on it; but sun scarabs live on dung heaps, which typically contain the mycelium of psilocybin mushrooms, so it is reasonable to assume that these scarab beetles may have been loaded with psilocybin. Whether or not there is something to that suggestion, a further important ingredient of the recipe is a plant called “Kentritis.” We cannot find out anymore which plant that was, but the Egyptians at the time must have known it. The text gives precise instructions about how to make an eye paint by combining these substances, which you then have to rub into or around the eyes, where the skin is thin. It will take some time to start working and then you will have those visionary experiences. It’s all very straightforward. I find it amazing that almost none of the major specialists has called attention to it.

J: So why exactly can those experiences be explained through drug-induced states of consciousness better than in other ways?

H: First of all, the recipe is there, and the text says explicitly that it is “necessary” to make the ointment and apply it to your eyes. How much more evidence do we need, given the spectacular visions that follow? There have been great scholars studying this text in detail, but they have not provided any reasonable alternative explanation for the visions. For instance, one major specialist says “well, how does it work? You have to inhale rays of sunlight.” True: the text does say that. But then I would ask “OK, so try it out: find a sunny spot and start inhaling sunlight. Are you going to feel lifted up into the air and see visions of gods?” I don’t think so. It’s simply not sufficient as an explanation. It seems to me that this particular case of the “Mithras Liturgy” is perfectly straightforward, because you have the combination of spectacular visions and a detailed recipe that the text says you need to use if you want to experience them too. The other cases I talked about are more complex.

J: Would you say that Altered States of Consciousness in general are an important factor in human culture, or in human experience throughout history?

H: Definitely. But then you have a broader concept of “altered states” that does not necessarily involve drugs or psychoactive substances. There are many ways to alter consciousness - it can be done by music, by drumming for instance, by sensory overload, but also by under-stimulating your senses.

J: You mean sensory deprivation?

H: Sensory deprivation, exactly. For instance, there’s a fantastic book (I’ve reviewed it recently) by Yulia Ustinova, a Russian/Israeli specialist of ancient Greece.

J: I know her, she’s writing about shamanism -

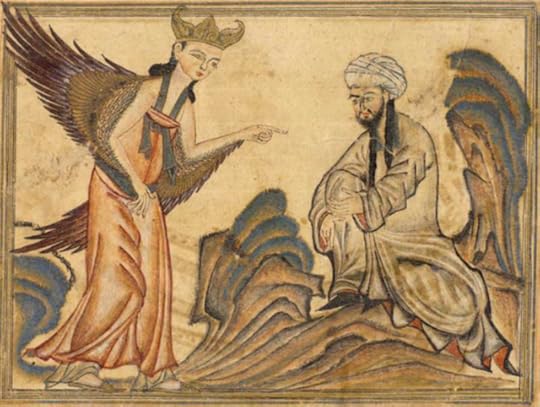

H: And ancient Greece, yes. She talks about people going into caves. It’s interesting to see how many visionaries, people who have revelations (think of prophets such as the prophet Muhammad), are said to have retreated to a cave over long periods of time. There they meet a spiritual entity, for instance the angel Gabriel. So what Ustinova emphasized is very simple. Initially we might think “what’s the point? Why go into a cave to meet the gods?” But if you actually do enter a cave, you will discover what that must have meant in antiquity – when you didn’t have any of the media that we have today. A first thing: it’s extremely dark, there really is no light at all (we take artificial light for granted, but you wouldn’t have any of that). And secondly: it’s completely silent too (and again, in our world full of noise and background buzz it’s hard to imagine how intense that could be). Under such conditions, the brain will compensate for the lack of sensory input by producing hallucinations. These can be either visual or auditory, so you will hear voices and see visions. That is just what the brain does: it will happen to any of us under such circumstances. Of course, most of the rough material of the visions comes from culture: if you live in India you might see Indian gods, a Chinese Buddhist might see the Buddha, the Greeks might see the Olympian gods, and so on. I’m not saying that this is the universal key for everything, but I think that sensory deprivation may be a pretty major key for understanding some of the spectacular revelations that are reported by religious visionaries. If there is truth to this, it means for instance that a great world religion like Islam may have its ultimate origins in revelations of this kind, visions and auditions in the darkness and silence of a cave – I think that should be pretty big news. In this case, of course, we are not speaking about entheogenic substances: I’m not suggesting that prophet Muhammad was taking drugs! Not at all, but he did go into a cave.

Likewise, in a more recent book, Yulia Ustinova talks in much broader terms about the great importance of alterations of consciousness in ancient Greece. She needs a pretty big book to simply lay down all the textual evidence, which is quite overwhelming. Of course, what make ancient Greece particularly interesting is the fact that we have all learned about the Greeks as the original rationalists, the founders of modern science, and all that. The reality is quite a bit more complex.

J: Maybe we can skip to terminology for a while. If I understand it correctly, you distinguish between religion and spirituality. What is the difference?

H: Well, I’ve recently started to push the term “spirituality” as a scholarly term. One reason is strategic. If you look at the academic study of religion at the moment, internationally, you can see that we are in trouble. We are in the defensive, there is less and less money available, and we are outclassed by media personalities who are often very confident talking about religion although they are no specialists and often don’t know much about it. So you get famous physicists or psychologists talking about God, or about religion, unaware of how complex the issues really are. As historians of religion we seem to be missing the boat: we have failed to come up with a really convincing story about religion, and often it’s theologians who take our place. We have not succeeded in explaining to the public at large that study of religion is something very different from theology: that it’s not about your own beliefs but about trying to understand the phenomenon of religion from a scholarly perspective, historically, socially, etc. So I have come to the conclusion that “religion” has not served as a good brand: if you’re telling prospective students that you study religion, too many of them still think “oh, that’s about churches and doctrines and so on.” It just doesn’t work.

Now there has been empirical research by sociologists about what common people generally understand by “spirituality,” and they found that it’s essentially defined as focused on the individual, on personal experience, and on practice. If you image-google spirituality, you get meditating people and lots of candles – so it seems that people subconsciously associate spirituality with a light in the darkness.

J: Nice metaphor!

H: Isn’t it? But anyway, “spirituality” understood as individual, experiential practice is a specific type of religiosity that should be recognized as such and must be studied in its own right. I am not saying it should take the place of religion in my discipline, of course not; but I think we must create a place for it.

J: And what can we understand by the term of “entheogenic esotericism,” specifically?

H: Well the word comes from entheos ἔνθεος, which means something like the divinity inside. Not a divinity that comes from within, but one that enters you, takes possession of you. It has to do with that experience of being overwhelmed by the gods, divinities or a divine force.

J: From the outside they come inside.

H: Yes. And consider our very common word “enthusiasm,” which we all use. It comes directly from enthousiasmos, which means very much the same thing. Being filled with a god.

I define “entheogenic religion” in a double sense: a broader and a narrower meaning. In a broader sense it covers forms of religion based on alterations of consciousness induced by any means – for instance music, drumming, dancing, sensory deprivation. In a narrow sense you’re dealing with those forms that are specifically induced by psychoactive substances.

“Esotericism” is a different matter. I use it as an umbrella term that covers what I call “rejected knowledge”: basically everything that has been rejected and put into the “waste basket of academia” since the 18th century. Everything that we used to think was beyond the pale for serious scholars, such as magic, astrology, alchemy, all this strange stuff that was considered “irrational” and was neglected by research. The study of “Western esotericism” is all about putting those ideas and tradititions and practices back on the table. So if you then combine the terms, “entheogenic esotericism” in the wider sense would be again all this kind of stuff in so far as alterations of consciousness are central in it, and in a narrow sense it would be specifically induced by drugs.

J: Why is it that people don’t like the term “religion” but are more able to accept spiritualities? Can it be a consequence of secularization?

H: Yes, we live in a society where religious institutions are not dominant anymore. Christian churches used to be totally merged with state power, but they became essentially like private enterprises since the 18th century already, so what you see is the emergence of a kind of “religious supermarket.” That situation has become ever stronger, and nowadays you might say that most of us in secular societies are walking around in this supermarket of religion and spirituality. You stroll around there with your trolley and think “oh, I like meditation,” so you put some bits of Buddhism in it; “oh, but having been raised Catholic I do have that weak spot for Maria,” so you put her in too; and “oh, I’d like to try these drugs,” so let’s get a bit of that. And so on. You make your own mixture that fits to your personal taste as a consumer.

Religion is no longer part of the bedrock of society, as in the time when scholars like Durkheim could still define “religion” basically all part and parcel of society. For Durkheim, “magic” by contrast was something non-religious and hence asocial. I would say that situation pretty much belongs to the past, at least in Western secular societies. Nowadays religion takes many forms, it’s very much individualized, and so it becomes a consumerist thing. And of course with the internet and social media you get a kind of acceleration of such processes – you just look on your phone and you are linked from one thing to another, you may encounter bits and pieces of traditions, mixing them according to your own preferences and making something out of it that fits your personal tastes.

Religion is no longer part of the bedrock of society, as in the time when scholars like Durkheim could still define “religion” basically all part and parcel of society. For Durkheim, “magic” by contrast was something non-religious and hence asocial. I would say that situation pretty much belongs to the past, at least in Western secular societies. Nowadays religion takes many forms, it’s very much individualized, and so it becomes a consumerist thing. And of course with the internet and social media you get a kind of acceleration of such processes – you just look on your phone and you are linked from one thing to another, you may encounter bits and pieces of traditions, mixing them according to your own preferences and making something out of it that fits your personal tastes.J: So how does using entheogens or other drugs like psychedelics fit this pattern? How can they answer people’s questions and people’s needs in this supermarket?

H: It’s actually a complex question. I’m talking about “entheogens” here, using a terminology that bestows a religious or spiritual meaning on psychedelics. We are not talking here about such substances as cocaine or alcohol. The “psychedelics” terminology, on the other hand, is more psychological than religious or spiritual: it means that something is done that allows the mind, or soul, or spirit to manifest itself. If you are raised in a certain kind of society, you will take certain things for granted; and our culture tends to suggest that psychedelics is just some kind of play, some kind of illusion: a “trip.” But what we know about psychedelics or entheogens is that in fact they often allow people at least temporarily to distance themselves from the default cultural conditioning that they are used to and see it for what it is. I think that’s one reason why users so often say that through psychedelics they have gotten in touch with what their true values are, what they really want in their life: “is it really just this all this consumer stuff that I want, or getting power or money? Or are such pursuits not ultimately so important and there are other, more important things to pursue?” This helps explain why psychedelics and entheogens are becoming quite successful and popular nowadays: it is because we are living in a society where the mainstream institutions no longer provide answers to questions about the meaning of life and those kinds of things. So most people in contemporary society feel like they are drifting – unless you are a solid member of a church or another religious community, of course. But if you are a typical individual consumer on the neoliberal market, then society isn’t telling you what the meaning of your life is. I do think, however, that people feel a need for those kinds of answers.

J: They are searching for them.

H: Yes, they are searching for those answers and they cannot find them. What you see with entheogens is that they often lead people to a level of their mind or consciousness where it’s easier for them to find what’s really meaningful to them. So yes, I think they respond to a need, in our current very much secularized and individualized society, for finding answers about the deeper meaning of your life.

J: What about the current phenomenon of psychedelic or entheogenic shamanism? Can you describe how it emerged in recent decades?

H: Well, shamanism is originally a very specific term that comes from Siberia. It was Mircea Eliade, the famous scholar of religion, who came up with this idea of a generic shamanism that supposedly existed everywhere. That is a bit problematic, because those cultures are different, and what you find in Siberia is not the same as what you find in South America and so on. So I’m very skeptical about the shamanism terminology, but it has certainly become very popular. Eliade himself actually played down the importance of psychedelics and entheogens in shamanism, but after the sixties you see that his universal shamanism is often combined with the growing interest in psychedelics, see for instance Carlos Castaneda. What you see very clearly is that the “frontrunner” in contemporary entheogenic shamanism is ayahuasca, and South American forms of shamanism more generally. Because ayahuasca is a very powerful entheogen, it has been used in a ritual context for a generations and generations in the Amazon forest. It has taken on new ritual or ceremonial forms under the influence of modern psychology and therapeutic traditions, and spread to the West. So these workshop leaders are described often as shamans, although again, I’m not so sure whether that’s the right term. There is also a non-entheogenic and non-substance modern shamanism, of course, beginning with Michel Harner with his “core shamanism,” which induces altered states through drumming.

J: What is his precise role in this approach?

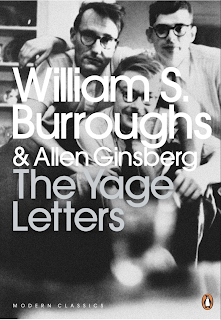

H: Well, Michel Harner – that’s actually a good story. He began as an anthropologist doing research in the Amazon forest and drinking Ayahuasca with native cultures there. He had impressive experiences and began doing rituals himself, but then after the sixties he was not able to continue organizing those workshops due to prohibition of psychedelics. So then he developed an alternative form of shamanism based upon rhythmic drumming. Apparently this had a very strong effect as well, so he developed it as a legal alternative for using ayahuasca or other entheogens. It became very popular. You might say that the ayahuasca type of shamanism just took a bit longer to join popular culture again. Although of course, already in the fifties there were some famous people, like Alan Ginsberg and William Burroughs, who went looking for ayahuasca in the Amazon region.

J: The beat generation.

J: The beat generation.H: Exactly. But ayahuasca didn’t really become mainstream until the nineties. So the bottom line is that Michel Harner was a kind of pioneer, and when finally prohibition became a little bit less strict so that it became easier to get access to the psychoactive substances of original forms of entheogenic shamanism, they merged together.

J: And how is this connected to ayahuasca churches like Santo Daime from Brazil, and others?

H: Santo Daime, União do Vegetal, and Barquinha are Brazilian churches based upon Ayahuasca as a sacrament, so they are mixtures of Amazonian native religions and Christianity, mostly Catholicism. They use Ayahuasca – in the Santo Daime they call it Daime, which means “give me” – as their sacrament. Daime is a sacred substance to them, so you go to this church and get administered a glass just in the same way as Catholics who receive the eucharist. They are singing their own hymns and get into very powerful altered states under the influence of their sacrament. Santo Daime has spread from Brazil to other countries in America and Europe. There have been all kind of legal battles in my own country. These have been quite important, because in the Netherlands for about 18 years (since 2001) religious use of ayahuasca was legal: the court had decided that to ensure their freedom of religion, it must be permitted to the Santo Daime to be able to drink their sacrament. So religious freedom in this case overruled drug legislation. I think this was correct, for we know that ayahuasca is perfectly safe if used in a responsible manner under proper supervision in such a religious context. Unfortunately the decision was overruled by a higher court on the European level a few years ago. So for a long time in the Netherlands you could just go to the Santo Daime church, and after an intake you could drink Ayahuasca with them.

J: So it’s basically because of European legislation that ayahuasca cannot be drunk legally in the Netherlands anymore?

H: As far as I know, what happened is that a member of the Santo Daime thought “OK, now that we have this freedom in the Netherlands, we should bring it to the European level.” Unfortunately this led to a court case without proper legal advice. When the original court decision took place in 2001, there was excellent legal assistance; but that was not the case now, and in such sensitive cases you really do need to know exactly how to proceed. So unfortunately, the result was the opposite of what had been intended.

J: I read your article about Terence McKenna’s and his brother’s search for ayahuasca brew in 1971, which resulted in their long-standing hallucinogenic visions about the nature of the time and the eschaton of the world. Can you explain what happened to them in the Amazon forest?

H: Oh right, you want me to tell that story…

J: It’s a great story!

H: I mean, this is going to be a long interview then! Well, as briefly as possible, Terence McKenna was a typical hippie of that generation. He with his brother and some friends were totally fed up with mainstream Western society and were looking for answers in entheogenic shamanism. They had heard about mysterious hallucinogens in the Amazon forest, and so they ended up in a place La Chorrera in Colombia, the Putumayo region. They actually didn’t find there what they were looking for, but they did find lots of mushrooms, so they made a brew from it. Terence’s brother Dennis (who is now a well known ethno-pharmacologist) had a kind of revelation under the influence of the mushroom trip, and was making a very strange sound. In trying to interpret that, these guys embarked on some really wild psychedelic speculation: if you could make that kind of sound under the right conditions, then they thought it should be possible to “break through” to a completely different dimension of reality. Then you would get a kind of rippling effect and finally, after the 24-hours sun cycle, the whole of humanity would be enlightened!

So to do this experiment, they tried to make ayahuasca. For that you needed the ayahuasca vine (banisteriopsis caapi) plus DMT-containing plants, because that combination is what ayahuasca is all about. But McKenna in a footnote of his book admits that they weren’t sure they picked the right plants… So nobody knows what they may have put in that brew! We will never find out. Believe me, it was far more dangerous than they realized. I’ve been to the Amazon, and our guide told us that if you pick ten plants at random, the result will always be a deadly poison. So I’d say they were lucky to escape with their life. Also, take into account that the ayahuasca vine is an MAOI inhibitor. If you put mushrooms in the mix, as they did, then the result will be that the psilocybin effect will get boosted enormously. Instead of couple of hours, you may get a trip of twenty-four hours that may be five or six times stronger than normal. That, plus those other plants that we don’t know about. So this brew, whatever was in it, must have been something quite spectacular. In the middle of this gigantic trip, Dennis actually started making that sound again, so everybody got excited: “now it’s happening! we are breaking through to the other side!” Of course, when they finally came out of the forest, they found to their disappointment that the world had not gotten enlightened. It seems that Terence McKenna could never really accept this. In the seventies he wrote this book together with his brother, The Invisible Landscape, in which he develops a complete theory about the structure of time. It basically says that there are larger and smaller cycles of time and there’s a culmination point coming soon, in 2012.

J: Of course.

H: At that moment a whole series of cycles would end and there would be a big transformation of everything. 2012. OK, to finish the story: at one point McKenna met up with José Argüelles, a spiritual author fascinated with Maya culture and the Mayan Calendar. They put their theories together and came up with specific a date: 21st December 2012. That idea got disseminated through popular culture and everybody got very excited. I don’t know whether you remember this.

J: I remember it very well – it was all over the news…

H: Yes. One of the major Dutch newspapers (Het Parool, based in Amsterdam) made a big joke of it by bringing out their very last issue on that day, special issue for the last day of the world. That was quite fantastic. I have some good friends who were totally convinced that the great transformation was going to happen on december 21 and nothing would ever be the same anymore. That all of us would move into a different state of consciousness on that day. So Terence McKenna is one of the main authors at the origin of this theory – and it all started with some absolutely weird entheogenic experiments in the Putumayo region in Colombia.

J: That’s really a nice story, I love it.

H: Yeah, me too! [smile]

J: Why do you think that those narratives about the changing of the times and the end of the world are so popular in these days?

H: I think they have always been popular, there has always been an attraction for these kinds of apocalyptic stories. However, today we are living in very difficult times indeed: I mean the climate crisis, the fear of animal extinction, the huge economic-social problems that we are dealing within a world-wide level, and so on. Also the fact that through social media and the internet we are constantly bombarded with information about everything. So we are overwhelmed by all this negative information as well, and I think many people are just very worried about where we are going. I am no exception. It’s natural for eschatological theories to come up in such times: the belief that we are moving toward a crisis, and perhaps it will end in disaster, but perhaps we will move through it towards something better. That’s very attractive, very understandable. So yes, I think we’re definitely experiencing a sense of crisis, a crisis of meaning, of what life is all about, of where are we going and so on.

J: So people are creating stories about this change, about all of those things?

H: Yes, we are creating stories. That is what religion does. Telling stories.

J: You wrote an article about Louis-Alphonse Cahagnet, who you consider to be perhaps one of the very first psychonauts. Can you describe his story?

H: Well, you’ve really been reading my stuff. Thank you, I feel flattered! [both laughs]

Cahagnet was a French spiritualist. An interesting guy, not an intellectual, he worked with his hands but was very smart, very intelligent. I have a liking for him. He was working with somnambulic visionaries. Artificial somnambulism, as it was called, was this technique for bringing people into a trance state, during which they would claim to travel into spiritual realms and to other worlds. It was very popular at that time. Magnetizers were mostly men and the persons who went into a trance were usually women. So Cahagnet wrote three volumes about his experiments with somnambulic women. They told him the most amazing stories about other realities, other worlds, they traveled to other planets, they saw angels and all kinds of stuff like that. So Cahagnet got quite frustrated: he wanted to see it all for himself too. But he had no talent for trance himself; and even if you did go into somnambulic trance, you would lose you consciousness and afterwards wouldn’t remember anymore. But he wanted to go there in a conscious state, he wanted to experience it himself. And so he started experimenting with drugs. He tried to find old recipes and hallucinogenic plants. He was really willing to go out there, but nothing worked. He actually poisoned himself several times, got very sick, but nothing worked. Until one day he found “hashish of the orient.” Just in a pharmacy: it was legal at that time, you could just buy it.

J: Really?

H: Yes, that’s a bit hard to imagine now. Hashisch had this aura of “oriental mystery.” Cahagnet didn’t smoke it, he dissolved it in coffee, drunk it, and then a couple of hours later it begun to work. He had this absolutely amazing experience, that he say answered all his questions: he got the sense of a complete overview of his whole life. It’s actually quite funny to read the “trip report” of somebody who had no predecessors and absolutely no idea of what to expect. After this, he started to organize sessions with people that he invited to his apartment in Paris. He handed out the hashish to them and became the center of a kind of psychonautic community. And he wrote a book about it. It’s almost never quoted but I think it’s actually a very important text. It was read by most of the founders of the occultist movement for decades after that, and was quite influential.

J: And what’s the name of the book?

H: In French: Sanctuaire du spiritualisme (Sanctuary of Spiritualism, 1850). It was translated into English as The Celestial Telegraph (same year).

J: Why did this entheogenic breakthrough remain hidden from the wider public?

H: Well, it was basically a minority religion. I don’t think that it was kept secret deliberately. Spiritualism was actually a kind of mass movement at that time, and entheogenic practices spread to some extent in that context. Occultists came out of spiritualism but developed their own rituals, techniques and practices. There was a discrete culture of entheogenic usage in occultism, which has not been systematically studied until quite recently: see Christopher Partridge’s book High culture: Drugs, Mysticism, and the Pursuit of Transcendence in the Modern World, which is very valuable. Still, much of this is still largely unexplored territory.

J: How does Aleister Crowley and his famous love for drugs and bizarre sexuality fit into this atmosphere?

H: I have to say that I’m not a specialist of Crowley. I prefer to look at things that are people are not studying, and it almost seems as though everybody is studying nothing but Crowley these days…

J: OK, I understand.

H: But anyway, Crowley was experimenting certainly with mescaline, with hashish, at one point with heroin, and that got pretty fatal, because he ended his life as an addict. We just heard at this conference that this was the cause of his death – I didn’t know that. Basically I can repeat what was said earlier [in the conference]. On the one hand there is this practice of ritual magic, which requires disciplines, focus, attention and so on. On the other hand, there is the use of drugs in occultism, because they open up the mind to other dimensions than normal rational consciousness. Basically, it seems that Crowley was interested in anything that could get him there. And there’s a certain tension I think, between those two approaches.

J: So how do you consider the impact of this entheogenic occultism on later 60ties counterculture. Is there some connection?

H: Of course. I’m just reading the diaries of one of the early pioneers of the fascination with UFOs, Jacques Vallée. They are fascinating to read, as he gives you a very direct insight in the California counterculture of the seventies. And yes, already then it was all about Crowley, but also about the satanism of Anton LaVey, who was a good friend of Vallée. And in this whole culture everybody was experimenting with drugs, especially with LSD, but other substances as well. So those approaches merged in a natural way, you just can’t skip it in that period.

Then, of course, around 1970 prohibition happened and things changed. Nixon basically used psychedelics as an excuse for putting members of the counterculture into prison. The authorities wanted to break its power, and the drugs were a handy means of doing it. And it must be said: the establishment won, the counterculture lost. That’s very clear. So hippies start to concentrate on meditating instead, they got a bit older too, so they got kids and responsibilities. And the radical movement went underground. One of our PhD students, J. Christian Greer recently defended his dissertation about what happened in the eighties. This whole underground movement of psychedelia went underground and was flying very much under the radar of the authorities. Because they were using zines: handmade magazines that you would basically circulate among your friends through the mail. So you get this whole network of people who are the heirs of the sixties and seventies psychedelic subculture, and the authorities don’t really know about them. Then in the nineties, of course that movement begins using the internet.

J: What do you think are the benefits that people can gain from entheogenic visions nowadays?

H: Well, I think you have to specify for what kind of substance. Because I think it’s different for each one.

J: You may choose any substance you want.

Santo Daime ceremony in Mapia (Brazil)

Santo Daime ceremony in Mapia (Brazil)H: Let me think… Well, for example ayahuasca. Basically, as I already said, it has this ability of making people take a distance from their normal social roles. As far as I can tell, ayahuasca is one of the most powerful therapeutic substances in the field of psychedelics, of course if it’s taken in a responsible setting by people who know what they are doing. A few sessions with ayahuasca can potentially be the equivalent of years of therapy, so I think there’s a huge potential for helping people who are struggling with difficult stuff from their childhood, from other things that happened to them, whatever. There were some remarks earlier this day about risks; and unfortunately there’s an increasing trend of commercialization. Around the time of the Santo Daime verdict, there was a case in the Netherlands where somebody was said to have died in an ayahuasca ceremony. Police did not disclose the full information and there’s good reason to assume that in fact it was not actually ayahuasca but something else. But of course, the effect on the general public is predictable: they will think “oh my God, look how dangerous it all is.” Media sensationalism makes it difficult to be nuanced in these domains.

J: True. We had a similar case in Czech Republic, people got poisoned from fake ayahuasca and the “shaman” spent some time in jail. Now the mainstream media automatically links ayahuasca with danger. But anyway, back to a more positive note – what is your relationship to music? I know that beside your academic career, you are also a classical guitar graduate…

H: Well, I love music! I originally was a classical guitar player. I attended conservatory, but then I realized that I didn’t want to end up teaching pupils the first beginnings of guitar for the rest of my life, so I moved into the different direction. But I love music, and in this context – there is a very interesting relation between entheogens and music. Because one of the effects it has, and that goes for many psychedelics, is that one’s sense of music gets three or four-dimensional.

J: Wow…

H: Yes, most users of psychedelics will tell you that even if they listen to music they know very well, it gains an entire new level of depth that is hard or even impossible to explain. Another aspect is that in many entheogenic contexts, like ayahuasca, music plays a crucial role; because people are experiencing very extreme states of consciousness and the music is something they can hold on to, it guides them through the process, again in a way that’s not easy to explain. You have the ikaros in native American contexts. The same goes for the Santo Daime with their hymns. So I think music and entheogens are kind of “natural allies”. They go together: they can both induce alterations of consciousness.

J: Do you think that music itself can be a means to a transcendental state?

H: Yes, I think so. I have experienced that myself. You must be in a kind of a receptive state, at the right moment with the right musician. I remember several cases where I was just completely in another world. There are also documented cases, for instance I’m thinking of a French pianist Pierre-Alain Volondat, who won one of the largest piano competitions in the world, the Queen Elizabeth Contest. He was playing this extremely difficult piano concert by Franz Liszt, in front of this large audience and broadcast live on TV, so he must have been under a lot of pressure. He says that he remembers putting his hands on the piano – and then heard the applause. He couldn’t remember anything of what happened. He clearly got into some kind of a trance state and played so brilliantly that he won both the public price and the jury price, which had never happened before. And if you listen to the recordings (scroll down here for the audio - I find these Brahms ballads simply one of the best live performances I've ever heard) I think you can hear that they are really of transcendental quality. I do think that great musicians, I mean the really greatest ones, sometimes have that ability to enter into an altered state while playing, while still having all the technique at their disposal. I think that’s really something extraordinary.

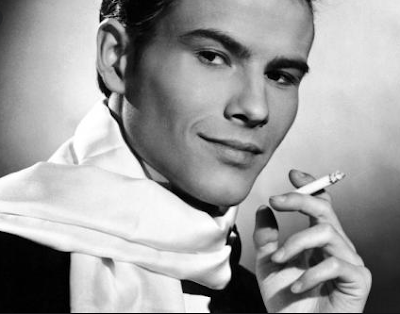

Pierre-Alain Volondat, Queen Elizabeth contest 1983

Pierre-Alain Volondat, Queen Elizabeth contest 1983J: One last question – what do you think about prohibition of entheogenic substances and psychedelics?

H: I think it’s quite irresponsible for society to simply prohibite substances if research shows that they have the ability to seriously help people who cannot be helped in other ways. One colleague of mine, a well known professor of psychiatry in the Netherlands, gave a public lecture not so long ago – slide after slide full of double blind studies, figures, figures, figures, and he basically said that psychiatry has not made any real progress for 15 years or so. There are no new ideas, no new theories, no new practices, nothing. With one exception: it seems that psychedelics are the only thing that actually works and offers new potentials for treatment. More than that, he told us that it works for almost all the major psychiatric problems: anxiety, depression, trauma etc. That’s not a fairy-tale but very well documented. So I think we need a rational approach to these substances instead of one that’s just based on fear without proper knowledge. It’s time for politicians to get over the stereotypes and understand that there’s a real potential here for helping people who are struggling with serious problems.

Betz, Hans Dieter, The “Mithras Liturgy”: Text, Translation, and Commentary, Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen 2003.

Cahagnet, Louis-Alphonse, Sanctuaire du spiritualisme: Étude de l’âme humaine, et de ses rapports avec l’univers, d’après le somnambulisme et l’extase, Paris 1850.

Greer, J. Christian, Angel-Headed Hipsters: Psychedelic Militancy in Nineteen-Eighties North America, Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Amsterdam 2020.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J., Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, Cambridge University Press 2012.

----, Western Esotericism: A Guide for the Perplexed, Bloomsbury 2013.

----, “Entheogenic Esotericism,” in: Egil Asprem & Kennet Granholm (eds.), Contemporary Esotericism, Equinox 2013, 392-409.

----, “The First Psychonaut? Louis-Alphonse Cahagnet’s Experiments with Narcotics,” International Journal for the Study of New Religions 7:2 (2016), 105-123.

Keller, Barbara, Constantin Klein, Anne Swhajor-Biesemann, Christopher F. Silver, Ralph Hood & Heinz Streib, “The Semantics of ‘Spirituality’ and Related Self-Identifications: A Comparative Study in Germany and the USA,” Archive for the Psychology of Religion 35 (2013), 71-100.

Streib, Heinz & Ralph W. Hood, “‘Spirituality’ as Privatized Experience-Oriented Religion: Empirical and Conceptual Perspectives,” Implicit Religion 14:4 (2011), 433-453.

Streib, Heinz & Ralph W. Hood (eds.), Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality: A Cross-Cultural Analysis, Springer 2016.

Ustinova, Yulia, Caves and the Ancient Greek Mind: Descending Underground in the Search for Ultimate Truth, Oxford University Press 2009.

----, Divine Mania: Alterations of Consciousness in Ancient Greece, Routledge 2018.

July 24, 2020

Yes, It Is Possible... (Rainer Maria Rilke)

As the Corona virus was dominating the media and everybody’s daily lives, many of my friends on Facebook began launching “book challenges” to entertain themselves and the members of their networks. I accepted a challenge to list “10 books that changed your life,” and soon discovered that it was not just great fun to select ten titles and write about them, but that the exercise triggered a process of self-reflection. It made me conscious of some deep and long-term motivations and obsessions that have very much determined my personal life and my career as a scholar as well (or the other way around?). Here is nr. 4 on my list.

Browsing through my mother's book shelves one afternoon when I was around twenty years old, I came across this small “Salamander” pocket edition of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge (1910). My mother’s signature is in it, showing that she herself had bought it in 1956, when she was twenty-eight. If any book ever opened up for me the depth dimension to which great literature can give access, it was this one. I just didn’t know what hit me – this novel was so completely different from anything I had ever read before that I felt like entering an entirely new universe. It took me a very long time to finish Brigge, because I found myself returning again and again to the opening pages and starting over again: no matter how often I read any page, I never felt I had really understood it deeply enough to continue.There was always that sense of a surplus of meaning that kept escaping me, and this remains the case even when I read and re-read it today.

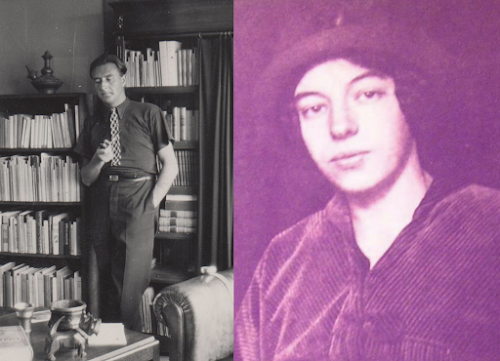

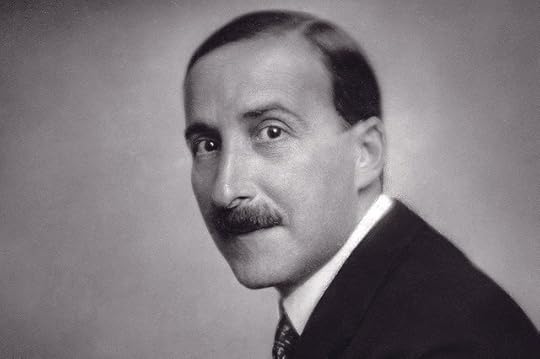

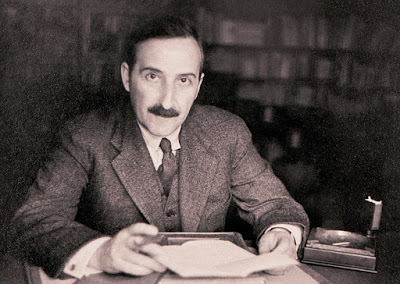

D.A.M. Binnendijk and Nini Brunt

D.A.M. Binnendijk and Nini BruntIt is remarkable that I was not even reading an edition in the original German but a Dutch translation by Dick Adrianus Michael Binnendijk (1902-1984) and Nini Brunt (1891-1984). Strange as it may seem, even today I find their translation at least as good and in some respects perhaps even superior to Rilke’s own German. So who were these people? As it turns out, both were well-known figures in the circles of Dutch literature. Binnendijk was a poet and critic known best for his friendships with important poets such as Menno ter Braak, E. du Perron en Hendrik Marsman, while Nini Brunt was a devoted and extremely productive translator remembered best for her Kafka translations. They were friends and collaborated on other projects as well, including a volume Demonie en droom: Vertellingen der Duitsche Romantiek (Demonism and Dream: Stories of German Romanticism). I very much like their ideas about translation: it was Brunt's opinion that readers should not be able to tell in which language the book had originally been written, and Binnendijk wrote that if one does not write clearly, this means one does not think clearly. Both very true. As it turns out, Binnendijk and Brunt were so confident and skilled that even in the case of a writer of genius, they dared to write what Rilke would have written if Dutch had been his native language. This is obviously risky and could lead to disastrous results in the case of lesser translators, but in their case it was a brilliant success.

Rilke’s novel resonates with me on many levels. Like his protagonist, I too spent a period of my life in Paris living in a single room of my own. As Brigge is wandering the streets, everything he sees and hears enters his mind with incredible intensity, sparking memories and associations that are unlike anything I have ever read anywhere else. Among the many passages that I know almost by heart, the following one in particular may give a clue to why I ended up pursuing the study of “rejected knowledge.”

It is ridiculous. I’m sitting here in my little room, me, Brigge, twenty-eight years old, a total unknown. I’m sitting here and I am nothing. And yet, this nobody starts thinking. And five storeys high, on a grey Paris afternoon, he is thinking these thoughts.

Is it possible, he thinks, that nothing true and important has been seen, recognized or said? Is it possible that one has had thousands of years’ time to look, to think and note down, and that one has allowed these thousands of years to pass by like a school break in which one eats one’s sandwich and an apple?

Yes, it is possible.

Is it possible that in spite of inventions and progress, in spite of culture, religion and worldly wisdom, one has remained on the surface? Is it possible that one has covered this surface, which was still something at least, with some incredibly boring fabric, so that it looks like the room furniture after the holidays?

Yes, it is possible.

Is it possible that the whole of world history has been misunderstood. Is it possible that the past is wrong ... ? ...

Yes, it is possible. ...

Is it possible that all those people have incredibly precise knowledge of a past that has never existed? Is it possible that all realities are meaningless for them; that their life is passing without connection to anything, like a clock in an empty room ?

Yes, it is possible. ...

But if all these things are possible, if they have even just a semblance of possibility, - then for the sake of everything in the world, something must happen. The very first person, he who has these disquieting thoughts, must begin to do something of what has been neglected, whoever he is, no matter how unfit he may be for the task: after all, there is no one else. This young, unimportant stranger, Brigge, five storeys high, will have to start writing, day and night. Yes, he will have to write. That is how it will end.

Formulated in different and more familiar terms: could it be that all our narratives are wrong? As individuals we only know who we are because of the stories we have been told (and keep telling ourselves) about where we have come from. And those stories are embedded in the much larger stories or grand narratives that we tell ourselves about our culture and society. Whether on the individual or the collective level, how we imagine our past determines the limits of who we think we are and what we are able to imagine about the future. So what if we were mistaken all along? What if we somehow missed what was actually most important? What if we were looking just at the surface of reality and never beyond? “Could that be possible?” I must have been asking myself, at some more or less conscious level of awareness, and Rilke gave the answer: “yes, it is possible.”

I do not recall any conscious decision on my own part to follow Brigge’s example, but it cannot be doubted that I did what he did: I started writing. And to tell the truth, as I was pursuing my explorations, I began discovering that what first seemed just a “possibility” turned out to be actually true. I remain convinced of that truth: very important dimensions of reality (I mean historical reality, the reality of human beings as they have traveled through time, stretching from remote antiquity all the way up to this very second in which I am typing these lines) have been overlooked, marginalized, distorted, discredited, mispositioned, in short – misunderstood, not just superficially or just concerning details, but at a fundamental level. At bottom, what this means is very simple: it could all be different. I cannot think of anything more liberating than that.

July 11, 2020

The Third Kind: Gilles Quispel and Gnosis

As the Corona virus was dominating the media and everybody’s daily lives, many of my friends on Facebook began launching “book challenges” to entertain themselves and the members of their networks. I accepted a challenge to list “10 books that changed your life,” and soon discovered that it was not just great fun to select ten titles and write about them, but that the exercise triggered a process of self-reflection. It made me conscious of some deep and long-term motivations and obsessions that have very much determined my personal life and my career as a scholar as well (or the other way around?). Number 3: a Dutch collective volume edited by Gilles Quispel.

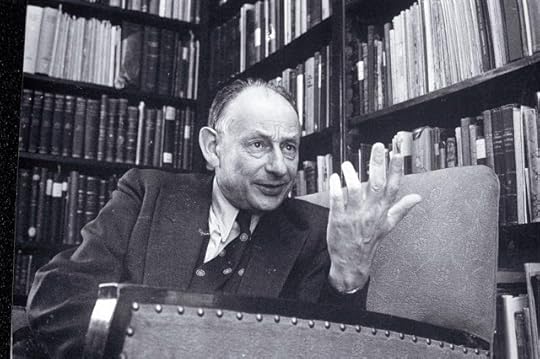

In a list of “ten books that changed my life,” this small Dutch volume cannot go missing – and yet I must confess that I include it with rather mixed feelings. It is not a very good book at all, and I select it only because the title had quite an impact on me. I bought this volume shortly after its publication in 1988, and quickly discovered that its general agenda and approach to the study of “gnostic” currents was quite different from my own. The editor, Gilles Quispel (1916-2006), was impossible to miss for anybody interested in such topics in the Netherlands by the end of the 1980s. He loved giving lectures for large general audiences, made appearances in the media, and was an internationally recognized authority of gnosticism. Of course I contacted him and he was kind enough to invite me to his home. Unfortunately though, we didn’t pull it off. Our personalities turned out to be so antithetical that we began clashing almost immediately, and our intellectual agendas were diametrically opposed. For my part, I wanted critical historical research free from apologetic agendas; for his part, he wanted to use his authority as a university professor to spread the gospel of gnosis. I do not think he would disagree with that assessment – for instance, when Roelof van den Broek and I organized a summer university “Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times” in Amsterdam in 1994, I distinctly remember how he introduced himself during the opening round, not as a scholar or academic but simply as “Gilles Quispel, gnostic.”

In a list of “ten books that changed my life,” this small Dutch volume cannot go missing – and yet I must confess that I include it with rather mixed feelings. It is not a very good book at all, and I select it only because the title had quite an impact on me. I bought this volume shortly after its publication in 1988, and quickly discovered that its general agenda and approach to the study of “gnostic” currents was quite different from my own. The editor, Gilles Quispel (1916-2006), was impossible to miss for anybody interested in such topics in the Netherlands by the end of the 1980s. He loved giving lectures for large general audiences, made appearances in the media, and was an internationally recognized authority of gnosticism. Of course I contacted him and he was kind enough to invite me to his home. Unfortunately though, we didn’t pull it off. Our personalities turned out to be so antithetical that we began clashing almost immediately, and our intellectual agendas were diametrically opposed. For my part, I wanted critical historical research free from apologetic agendas; for his part, he wanted to use his authority as a university professor to spread the gospel of gnosis. I do not think he would disagree with that assessment – for instance, when Roelof van den Broek and I organized a summer university “Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times” in Amsterdam in 1994, I distinctly remember how he introduced himself during the opening round, not as a scholar or academic but simply as “Gilles Quispel, gnostic.” A typical representative of the Eranos perspective, Quispel gave a peculiar twist to Jung’s concept of Gnosticism by reading it through the lens of a very specific Dutch type of Protestant Pietism known as bevindelijkheid. This virtually untranslatable word refers to a deeply conservative Christian tradition that emphasizes an individualized and experiential approach to biblical texts. Quispel loved to speak of gnosis as “knowledge of the heart,” but always made a point of pronouncing it as the bevindelijken did: not as kennis van het hart but in deliberately archaic Dutch as kennisse des harten – a nuance that is bound to escape anyone except a Dutch native speaker familiar with these traditions. It didn’t work for me. I must admit that my instinctive reaction to this type of language has always been similar to how Gershom Scholem reacted to reading Simone Weil, as formulated in a letter to George Lichtheim from 1950:

What attracts me to this very gifted unhappy young woman is the horrible smell of interiority, that … explains why I find Christianity so utterly unbearable. … Of course the swindle of pure interiority, from which may God preserve us, is presented here at a truly impressive pace, and all I can say is “Good for the Jews! as it just so happens that throughout the history of the world they have decidedly refused to take such a direction!” (Briefe II, 16-17)

Of course it wasn't entirely fair for Scholem to read Weil as representative of Christianity in general, but I understand what he means. Looking back at this time when I was in my late twenties and trying to find my way in a new and bewildering terrain, I cannot help wondering about the obscure psychological causes that lead all of us instinctively to say “no” to some things that come our way while saying “yes” to others, quite as instinctively – as in my case to Peuckert’s Pansophie, which (for reasons that I find hard to explain even to myself) strikes me as somehow quite similar to the Jewish perspective that Scholem preferred. Be that as it may, I was certainly making my own choices at the time. While the title of this volume, Gnosis: The Third Component of the European Cultural Tradition, had a decisive impact on the direction I took, its actual contents had an impact on the direction I did not want to take.

Amsterdam Summer University 1994, me on the left, Quispel sitting on the right

Amsterdam Summer University 1994, me on the left, Quispel sitting on the right

I was fascinated by the simple suggestion that the edifice of Western culture is supported by two pillars, “faith” (notably Christianity) and “reason” (rational philosophy, science) while a third but equally important component had been suppressed, neglected, and basically written out of the history books. Quispel called it “gnosis.” At this time I was mostly interested in music, literature, and all kinds of “alternative” ideas and traditions such as those I encountered in authors like Peuckert or Potok. Since none of it seemed to fit the “faith” and “reason” categories very well, or at all, Quispel’s book title made me wonder whether this mysterious thing called “gnosis” could be a suitable umbrella to cover everything I found so attractive. So that’s the direction I began to explore. I ended up writing a Master thesis in which I attempted to create a systematic typological framework to make sense of the gnosis-reason-faith triad. Bizarre as the combination may sound, I used a type of conceptual analysis that could hardly have been farther removed from Quispel’s Jungian perspective: american analytical philosophy. I had been introduced to it by the theologian Vincent Brümmer, one of my professors at the University of Utrecht, who was using it in a context of Christian-theological apologetics.

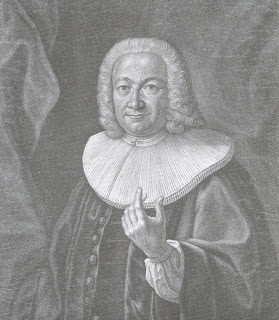

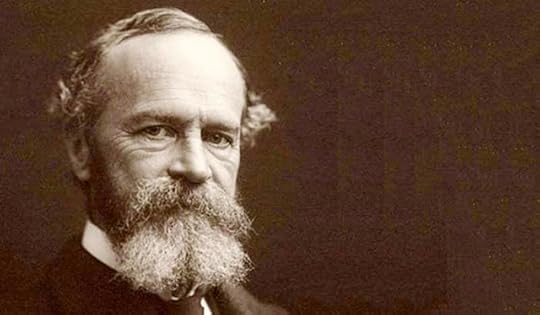

Vincent Brümmer

Vincent BrümmerAlthough I did not share Brümmer’s beliefs at all, I appreciated his intellectual openness to other perspectives than his own and his respect for the power of rational argument. I very well remember how one afternoon, I came out of his class and went straight into another one, where we were reading Merleau-Ponty’s L’oeil et l’esprit. It was as though I stepped from one universe right into another one. Merleau-Ponty struck me as profound but too vague, whereas analytical philosophy was very clear but somehow too superficial. I was looking for clarity because the subjects that attracted me were still quite vague and confusing to me, and so that combination prevailed. The MA thesis led to my first article in english; but I soon abandoned this approach as I found it too clean and artificial for my developing tastes. Under the impact of Jan Platvoet, who was teaching study of religions at the Catholic University of Utrecht, I moved towards what I came to call an empirical-historical approach that began with primary sources rather than theoretical abstractions. But that’s another story.

The bottom line is that Quispel’s title put me on a path that eventually led towards my understanding of esotericism as “rejected knowledge.” I saw that it was all about getting to know those ideas and traditions that had been excluded from mainstream culture due to the ideological and discursive dominance of “faith” and “reason.” Of course, my perspective soon got much more complicated, as it dawned on me that this field of “rejected knowledge” did not consist just of “gnosis” but could also be captured by other and quite different terms of exclusion, such as “paganism,” “idolatry,” “superstition,” “magic,” “the occult,” or simply “the irrational.” Be that as it may, although Quispel was very much an opponent of the entire agenda I stood for, I still owe him a debt of gratitude for coming up with that book title and making me ask the basic question: what is missing from the normative stories that our culture and our educational institutions are telling us? And why is it missing? Those questions kept me busy for more than twenty years, until I finally answered them, to the best of my ability, in my book Esotericism and the Academy (2012).

June 9, 2020

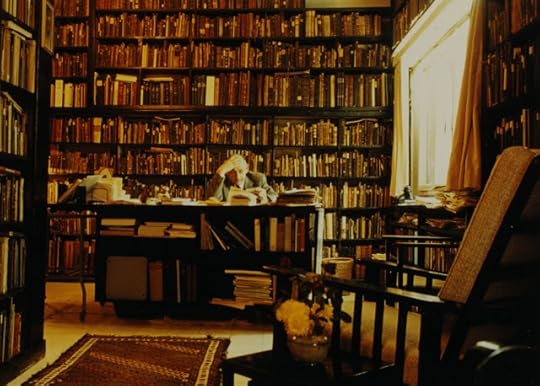

Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest: Will-Erich Peuckert's Pansophie (2nd ed. 1956)

Sometime during the later 1980s, as a student at the University of Utrecht I was browsing through the library and took a book off the shelf by pure chance, not suspecting that it would send me on a life-long quest. I read the title: Pansophie: Ein Versuch zur Geschichte der weißen und schwarzen Magie (Pansophy: An Attempt at Writing the History of White and Black Magic). What was that all about? Today I think of Peuckert as the true but sadly forgotten pioneer of what we have come to refer to as Western esotericism, and Pansophie as his most attractive book. Here I read for the first time about something called Hermetic Philosophy, and got introduced to Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Paracelsus, Jacob Böhme and a large host of lesser figures from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries. But it was not the content alone that impressed me so much. Perhaps most of all it was Peuckert’s unique, inimitable style of writing. The book breathed an atmosphere that I found irresistable and that I nowadays recognize as a peculiar kind of German gothic. Peuckert was one of the few specialists of German “folklore” traditions who refused any compromise with the Nazis. As a result, he was deprived of his right to teach, so he withdrew to the countryside and wrote this book in enforced isolation during the first half of the 1930s, as a record of his innere Emigration. He was in fact exploring the true roots of German culture in an attempt to rescue central figures such as Paracelsus or Jacob Böhme from their appropriation by the Nazis. In this regard, Pansophie might be seen as a direct parallel to what Thomas Mann was doing around the same time in his novels Lotte in Weimar (about Goethe) and, most of all, Doktor Faustus (for Mann insiders: Peuckert’s true home is in Kaisersaschern!). Of course the figure of Faust looms large in Pansophie too. I can’t resist translating the final paragraph of the Preface here:

I don’t regret it. I have seen what few others have seen: I have seen Faust and Luther and Weigel and Paracelsus and J. Böhme, the great movers of the German spirit. I have sat with astrologers and spent hours listening to alchemists. I have had the privilege to trace magic as truth. I had the chance to grasp what I considered necessary to grasp; the way of understanding lay wide open before me, and I felt no more restrictions than Paracelsus had once felt in his magic. Just one star stood shining above the road, the one that had shaped his destiny: Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest. I have been allowed to live beautiful years. I want to be grateful for all those years. For these years, and for this road. It is the only one that fits us. Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest” [Let he who can belong to himself belong to no other]

Peuckert was grateful for the road, but his later life would be full of tragedy. Having withdrawn to his vacation home in Haasel, in the Silesian Bober-Katzbach Mountains, he had transformed the cow-stable into a library and spent almost all his time reading and writing. But in January 1945, he and his wife had to flee for the advancing Russian troops, and his unique collection of 30.000 volumes would never be recovered. In the Afterword to one of his most important works, Die Grosse Wende, we read these truly heart-breaking words:

This book is a child of pain and misery. … The final sentences … were written in the January days of 1945. Next to the writing desk, prepared for flight into the icy winter, stand the backpacks of two people who have grown old in these days; and each title of each book that is quoted means a farewell to that book.

Two years later, his wife was killed in a car accident that left Peuckert almost completely blind and with heavy head injuries. Nevertheless, somehow he managed to keep writing books. Then in 1960 he lost his son, and in 1963 suffered a stroke that left him largely paralyzed so that he could only type with one finger. And still he kept writing, until a second massive stroke killed him in 1969.

In a previous posting on Creative Reading, I wrote about my discovery of Peuckert’s manuscript “Memories of a Magician.” Another manuscript in the Göttingen collection is clearly autobiographical and full of fascinating observations about what life was like for common people in the countryside during the first half of the twentieth century. Among many other things, it also describes his notorious youthful experiment with the witches’ ointment. As I described in an earlier article about Peuckert, in 1959 he made a passing reference to it in a lecture, resulting in an incredible media hype that ended up making him more famous than all his scholarly work had ever done. In response to continuing media requests, he even accepted to participate in a TV documentary that shows him in the cellar of his own house preparing Della Porta’s witches’ ointment in front of the camera. In the Göttingen manuscript, he describes how he and his buddy (they were about twenty years old at the time) rubbed the ointment on their bodies:

In a previous posting on Creative Reading, I wrote about my discovery of Peuckert’s manuscript “Memories of a Magician.” Another manuscript in the Göttingen collection is clearly autobiographical and full of fascinating observations about what life was like for common people in the countryside during the first half of the twentieth century. Among many other things, it also describes his notorious youthful experiment with the witches’ ointment. As I described in an earlier article about Peuckert, in 1959 he made a passing reference to it in a lecture, resulting in an incredible media hype that ended up making him more famous than all his scholarly work had ever done. In response to continuing media requests, he even accepted to participate in a TV documentary that shows him in the cellar of his own house preparing Della Porta’s witches’ ointment in front of the camera. In the Göttingen manuscript, he describes how he and his buddy (they were about twenty years old at the time) rubbed the ointment on their bodies:I got tired. Clearly tired.But then this tiredness vanished, I don’t know why. All I know is that suddenly I should fly. It was a flying without external props, but somehow I managed. It was as if I had flying membranes between my arms and my body, a bit like bats do – but I did not even need to use those membranes, for in fact some kind of force lifted me up from the podium on which I was standing and I floated through the long hall. Then I moved a bit higher and found myself floating above a forest – not high, and always in danger to hit a treetop.

He finally arrived at a kind of country fair and in the bustle of a wild party. In a kind of dance pavillion he watched women of all ages dancing in wild ecstasy, he mingled with the crowd and felt overtaken by desire, until he was finally embraced by a horrible old witch who suddenly transformed into a woman he knew... But of course, although his experiment with the witches’ ointment caused a sensation, it is in fact just a very minor footnote to Peuckert’s oeuvre. I fully agree with the assessment of Carlos Gilly, perhaps the most important modern specialists in Peuckert’s domain of specialization. Peuckert’s style may not be to everybody’s taste, but as Gilly noted, “Thanks to his immense erudition, which included the most unfamiliar areas of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century literature, Peuckert had such a secure instinct for what was essential, that even with incorrect quotations or insufficient argumentation he was still able to draw conclusions that were essentially correct” (Gilly, "Comenius und die Rosenkreuzer," in: Neugebauer-Wölk, Aufklärung und Esoterik [1999], 95 note 21)

It is worth visiting Peuckert's German Wikipedia page and have a look at his bibliography. This is what scholars were capable of, far before the advent of computers, using typewriters without cut-and-paste options, producing enormous manuscripts that had to be copied manually and then typeset letter by letter! Peuckert's oeuvre includes large biographies of Paracelsus, Copernicus, Jacob Böhme and Sebastian Franck; no less than twenty-four volumes devoted to German intellectual traditions, history and folklore; and on top of that, twenty novels or dramas! An incredible output that has not nearly received the attention it deserves. It is sad how quickly Peuckert was forgotten by German scholars during the seventies, in a climate dominated by Frankfurt School sentiments and their default demonization of all things "irrational" or Romantic. As formulated by Rolf Christian Zimmermann, just “two years after his death [in 1969], the name Will-Erich Peuckert hit … upon an apathetic reserve.”

It is worth visiting Peuckert's German Wikipedia page and have a look at his bibliography. This is what scholars were capable of, far before the advent of computers, using typewriters without cut-and-paste options, producing enormous manuscripts that had to be copied manually and then typeset letter by letter! Peuckert's oeuvre includes large biographies of Paracelsus, Copernicus, Jacob Böhme and Sebastian Franck; no less than twenty-four volumes devoted to German intellectual traditions, history and folklore; and on top of that, twenty novels or dramas! An incredible output that has not nearly received the attention it deserves. It is sad how quickly Peuckert was forgotten by German scholars during the seventies, in a climate dominated by Frankfurt School sentiments and their default demonization of all things "irrational" or Romantic. As formulated by Rolf Christian Zimmermann, just “two years after his death [in 1969], the name Will-Erich Peuckert hit … upon an apathetic reserve.” Well, not with me! It is thanks to Peuckert that I can echo his own words: I have seen what few others have seen, and have had the chance to grasp what I considered necessary to grasp. Like him I am grateful, for the years and for the road. Alterius non sit, qui suus esse potest.

May 6, 2020

Living with Ambiguity: Chaim Potok's The Book of Lights (1981)

Chaim Potok became famous with his best-selling novels The Chosen (1967) and My Name is Asher Lev (1972). I devoured and loved those books when I was young, but undoubtedly it is The Book of Lights that really did it for me. It is not so well known as the others, probably because the central theme is Jewish kabbalah – not such a familiar topic for the general public. Many readers may have found it somewhat difficult to relate to this story and understand what it was really all about, but I have to say that I took to it like a fish to water. It is through this novel that I first became aware of the great kabbalah specialist Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), who appears in the novel as Professor Jacob Keter. Potok presents him as the polar counterpart of an equally great Talmud scholar who goes by the name of Nathan Malkuson: yes, nomina omina sunt, for these are transparent references to the highest and lowest of the ten sefirot (luminous manifestations of divinity) that constitute the kabbalistic “tree of life.” The novel’s hero, Gershon Loran, is a student who falls under Keter’s spell and embarks on the path of becoming a scholar of Jewish esotericism. The novel’s picture of Jacob Keter is so impressive that it became my ideal model of what the scholarly life was supposed to be all about. Basically what happened is that I said to myself: “that’s what I want to be!” As for Gershon Loran, I think I identified with him on several levels, and as I re-read the novel not so long ago, I found that I still do. Central to the narrative – written by a writer born in 1929 who came of age in New York during the later 1940s and the 1950s, the high period of Cold War paranoia – is the mysterious phenomenon of the divine Light of Creation central to kabbalistic mythology. How, Potok was asking himself, does it relate to the Light of Annihilation revealed by the detonation of the atomic bomb? Is it at all possible to determine which one comes from the divine world and which one from the demonic realm, the sita achra? When I visited the quinquennial conference of the International Association for the History of Religion (IAHR) in Japan in 2005, I took The Book of Lights with me and followed Gershon Loran’s trajectory, traveling by high-speed train from Tokyo to Hirosjima. This visit remains one of the strongest impressions of my life. I spent a sunny day in the area where the bomb went off, now known as the “Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park,” surrounded by smiling tourists making pictures while trying to imagine what happened there on 6 August 1945. If by sheer luck you survived at all, how would your mind react to seeing literally everything and everybody around you obliterated, incinerated, utterly wiped away in one single blinding flash of total destruction? I spent hours in the Peace Memorial Museum at the square, feeling sick and exhausted when I finally came out, convinced that any President or PM in control of nuclear weapons should be obliged by law to visit this museum as a condition for taking office. And of course I spent time near the strange saddle-like monument, the Cenotaph, from which Gershon Loran heard a voice from the sita achra whispering to him. For me, Auschwitz and Hiroshima remain the two geographical centers of ultimate demonic horror that demonstrate the evil human beings are capable of. In my mind, the Cenotaph is also linked to Alain Resnais’ great movie Hiroshima mon amour (1959; based on Marguerite Duras). Watching it again after my trip to Tokyo, I realized that the hotel where the French actress and her Japanese lover have their final meeting must be the very same one from which Gershon Loran and his friend Arthur Leiden see the Cenotaph too.

Still from Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Still from Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)There are many passages in The Book of Lights that I love, and some of them I know almost by heart. A great favourite is the extraordinary account of Gershon Loran’s oral exam with Keter, during a long walk along Riverside Drive. Gershon drifts into a hallucinatory altered state, watching a numinous white bird circling above the water while listening as if from a distance and in a dream how he and Keter go through centuries of kabbalistic myths and imagery. But I will quote a conversation in Japan with his friend Arthur Leiden, the son of a great physicist who is tormented by the knowledge that his own father helped create the bomb and unleash the death light. Arthur asks Gershon why on earth he is so attracted by those weird kabbalistic books.

Weird? Maybe. Those books are really records of the religious imagination, Arthur. When I was a kid I once went up to the roof of our apartment house in Brooklyn and looked up at the stars. I remember I raised my hands in supplication – a little like the gesture of the monkey we saw today on the road. I felt something touch me. Oh yes, something touched me. I’ve been waiting to feel that touch again. Is that childish of me? This is, after all, the twentieth century. But sometimes when I read those texts I’m on the roof of that building again. I don’t know why I feel that way. They say things in those books that no one dares to say anywhere else. I feel comfortable with those acceptable heresies. God originally as sacred emptiness; ascents to God that are filled with danger, as if you were going through an angelic minefield; creation as a vast error; the world broken and dense with evil; everything a bewildering puzzle; and the sexuality in some of the passages. I like the sexuality. I especially like the ambiguities. Wow, Arthur, listen to me go. I’m saying more to you tonight than I did during all our seminary years. That is really good wine. Where was I? Yes. Ambiguities. You can’t pin most of it down the way you can a passage of Talmud. I can live with ambiguity, I think, better than I can with certainty.

I suppose that it was while reading this passage that I realized this to be true for myself as well. Gershon Loran came from an orthodox Jewish background while I was raised as the son of a Protestant minister; and both religious cultures were teaching their members to understand the world in terms of clear doctrinal certainties. Much too two-dimensional for my taste – reality couldn’t possibly be that simple. I felt more comfortable with the heretics, those who do not follow authorities but “make their own choices.” I still do.

The original bomb on Hiroshima

The original bomb on HiroshimaChaim Potok's The Book of Lights (1981)