Wouter J. Hanegraaff's Blog, page 3

August 4, 2017

Evola in Middle Earth

As part of my Western Culture & Counter Culture projectI’m studying the various “grand narratives” that have been told about the history, meaning, and direction of Western civilization – from optimistic stories of evolution and progress to their darker and more pessimistic counterparts. Perhaps the most uncompromising example of this latter category, and one of the most influential, was published in 1934 (and republished several times after, in expanded editions) by the controversial Italian esotericist Julius Evola (1898-1974) under the title Rivolto contro il mondo moderno (Revolt against the Modern World). I decided it might be time for me to finally read it, and so I did, in an excellent French translation by Philippe Baillet.

Well, it proved to be quite a ride. Having read various discussions of Evola over the years, I was broadly familiar with the nature of his worldview and ideas (including, of course, his fascist sympathies and antisemitic tendencies) so I cannot say that I began with an empty slate. However, actually reading Revolt against the Modern World from cover to cover is an altogether different experience from just reading about it. Let me begin on the positive side. Impressive about Evola’s book is the remarkable degree of internal logic and consistency of vision with which he deconstructs every imaginable belief or assumption that modern people tend to take for granted, exposing the whole of it as one long series of errors and perversions of the universal metaphysical truth on which all Traditional societies were based. He manages to strike a tone of “academic” authority that gives the impression that he knows what he is talking about, and it is not so hard to understand that a book like this can make a deep impression on readers who feel alienated from contemporary global consumer culture and would like to see it destroyed. With a radicalism reminiscent of contemporary Islamic Jihadists, Evola tells his readers that modernity is the very negation of everything valid and true.

Well, it proved to be quite a ride. Having read various discussions of Evola over the years, I was broadly familiar with the nature of his worldview and ideas (including, of course, his fascist sympathies and antisemitic tendencies) so I cannot say that I began with an empty slate. However, actually reading Revolt against the Modern World from cover to cover is an altogether different experience from just reading about it. Let me begin on the positive side. Impressive about Evola’s book is the remarkable degree of internal logic and consistency of vision with which he deconstructs every imaginable belief or assumption that modern people tend to take for granted, exposing the whole of it as one long series of errors and perversions of the universal metaphysical truth on which all Traditional societies were based. He manages to strike a tone of “academic” authority that gives the impression that he knows what he is talking about, and it is not so hard to understand that a book like this can make a deep impression on readers who feel alienated from contemporary global consumer culture and would like to see it destroyed. With a radicalism reminiscent of contemporary Islamic Jihadists, Evola tells his readers that modernity is the very negation of everything valid and true.Antihistorical Consciousness

So what is his alternative? This is where it quickly gets problematic. First of all, while Evola’s modern Right-wing admirers like to claim “historical consciousness” for themselves while blaming their “Liberal” enemies for having no sense of history, Evola himself makes perfectly clear that any attempt to find evidence for his historical narrative will be an utter waste of time. He claims that “Traditional man” had a “supratemporal” sense of time, and therefore the reality in which he lived cannot be grasped by modern historical methods at all. In an absolutely crucial passage in the Introduction (poorly translated in the English standard edition, unfortunately, so my translation below is based on the Italian original while taking inspiration from the French version) he takes care to emphasize

… how little esteem we have for everything that, in recent years, has officially been considered under the label of “historical scholarship” in matters of ancient religions, institutions, and traditions. We want to make clear that we wish to have absolutely nothing to do with such an order of things, as with all that derives from the modern mentality; and as for the so-called “scientific” or “positive” perspective, with all its empty claims of competence and monopoly, in its best cases we consider it to be more or less the perspective of ignorance. … In general, the order of things with which we will be principally concerning ourselves is the one in which all materials that have a “historical” and “scientific” value are those that are the least important; whereas everything that, as myth, legend, and saga, is deprived of historical truth and demonstrative force, by that very fact acquires a superior validity and becomes the source of a more real and more certain knowledge. Precisely this is the boundary that separates traditional doctrine from profane culture. …The scientific anathemas in regard to this approach are well known: Arbitrary! Subjective! Fantastic! From our perspective it is neither arbitrary, subjective or fantastic, nor is it objective or scientific as understood by moderns. All of that does not exist. All of that stands outside of Tradition. Tradition begins at the point where one is able to place oneself above all that, by adopting a supra-individual and nonhuman perspective. That is why we have minimal concern for discussion and “demonstration.” The truths that the world of Tradition can make us understand are not of a kind that one can “learn” or “discuss.” They either are, or they are not. One can only remember them, and this happens when one is liberated from the obstacles represented by the various human constructs (beginning with all the results and methods of the “researchers” considered to be authorities), when one has evoked in oneself the capacity to see from the nonhuman perspective, which is the Traditional perspective itself.

Clearly this means that any critical objection, any disagreement, any reference to historical evidence that might possible undermine Evola’s narrative, and indeed any reference to historical sources at all, will have no impact whatsoever. And this fits perfectly with the extreme authoritarianism that is typical of Evola’s attitude: the reader is given to understand that it is not really Julius Evola who is speaking to us in these pages – no, he is speaking on behalf of the supreme source of superhuman metaphysical truth itself (the nature of which, by the way, remains very vague). Disagreement is therefore synonymous with spiritual ignorance: one is not supposed to ask questions but to listen and accept.

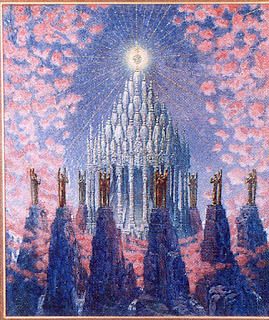

Doctrine and Storytelling

So what is this supreme Source of Truth telling us? Revolt agains the Modern World consists of two parts: the first is doctrinal and discusses the various elements of “the World of Tradition,” whereas the second should perhaps not be called historical – for how could it be that, on the foundations just outlined? – but does tell a grand story of spiritual decline and degeneration through the ages. Like Guénon, one of his major influences, Evola distinguishes between four stages of human and cultural development, from the Golden Age to the modern world (the kali yuga). The metaphysics of Tradition according to Evola are built upon the primacy of Being; on the notion of one absolute Spiritual Center that is the exclusive source of legitimate Authority, reflected in an ideology of Sacred Kingship; on the notion of a “natural” social hierarchy of four castes, with spiritual leaders at the top and servants (including slaves) at the bottom; on the primacy of masculine “virile” qualities over their feminine counterparts; and on an ascetic warrior ethics grounded in honour and heroic values. If anything stands out as central in this overview, it is Evola’s obsession with power. The second part is built upon the doctrine of “four ages,” with reference to Hesiod (the ages of gold, silver, bronze, and iron) and Hindu scriptures. Evola tells us that during the Golden Age, the region that is now the North Pole was inhabited by a pure race of superior beings who exemplified a “non-humain spirituality.” Due to some primal catastrophe, the representatives of this Hyperborean race began migrating southward towards what is now North America and the continent of Atlantis. This was the beginning of the Silver Age and the first stage of degeneration. Basic to the story that follows is the idea of a basic hostility between the heaven-oriented, solar, heroic, and masculine people from the North and their earth-oriented, lunar, matriarchal counterparts from the South (as is well known, Bachofen’s Das Mutterrecht[1861] had a huge influence on Evola in this regard). Cultural contact led to wars and interbreeding, so that the original purity of the Northern race got mixed and its culture began to decline. From there on it all goes downward. Things get ever more complex and messy during the Third Age, as the “heroic” descendants of the ancient superior culture progressively lose their vitality and the culture of the original spiritual elite slowly but certainly loses the battle against “anti-Traditional” forces. In spite of temporal revivals, notably during the the Roman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages, we steadily move foreward (or rather, downward) towards modern culture with its degenerate values of liberalism, humanism, egalitarianism, democracy, and so on. If Part I of Revolt is marked by Evola’s obsession with power, Part II is marked by an incredibly virulent hatred and supreme aristocratic contempt for modernity and everything it stands for.

The Deadly Sword of Philology

Of course it will be useless for me to apply the instruments of historical criticism in order to point out the utter absence of any credible evidence for Evola’s narrative: in making any such attempt, according to Evola’s admirers I will merely be demonstrating my own ignorance of the truth, and my naïve belief in such useless illusions as “critical discussion,” “historical thinking,” or “scholarly methods.” Trust in such merely human approaches betrays the false assumption that there exists such a thing as “progress in knowledge,” that is to say: it reflects the modernist delusion that it is possible to make advances in our understanding of the past, by learning important things about it that were not known before and by correcting earlier interpretations. No such progress is possible: it is excluded from the outset that I will ever discover anything important that Evola doesn’t already know. All I’m allowed to do is “remember” the eternal truth (obviously in terms of Plato's anamnesis), and if what I remember would turn out to conflict with anything that Evola is telling us, this could only mean that it’s not real memory: I must have made it up myself. Evola, of course, has made nothing up – how could he? It is not him who is saying all these things. He speaks for Tradition.

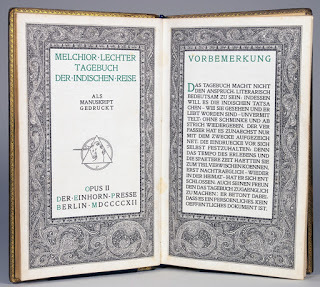

Still, although I know it’s pointless, I’ll make just one little attempt. Part II of Revoltis preceded by two mottos, one of which is taken from Jacob Boehme. Evola is quoting Louis-Claude de Martin’s French translation (1800) of Boehme’s first book, the Aurora:

Still, although I know it’s pointless, I’ll make just one little attempt. Part II of Revoltis preceded by two mottos, one of which is taken from Jacob Boehme. Evola is quoting Louis-Claude de Martin’s French translation (1800) of Boehme’s first book, the Aurora: Je vous dis un secret. Voici le temps où l’époux couronnera son épouse: mais où est la couronne? Vers le Nord … Mais d’où vient l’épouse? Du centre, où la chaleur engendre la lumière, et se porte vers le Nord … où la lumière devient brillante.[Translation: I tell you a secret. Behold the time when the bridegroom will crown his bride: but where is the crown? Toward the North … But from where does the bride come? From the centre, where the warmth brings forth the light, and is directed towards the North … where the light becomes brilliant]

Evola clearly saw this quote as a wonderful confirmation of his belief in a superior spiritual Light coming from the North. Of course it takes an unrepentant modernist like myself to be so deluded as to think it might be worth my while to check the source. Was Boehme really speaking about Evola’s North? You guessed it – I checked anyway. And what did I find? Sorry Julius, but this is what Boehme actually wrote:

Sihe Ich Sage dir ein geheimnis. Es ist Schon die zeit / das der Breutigam Seine Brautt kröntt / Raht fritz wo ligt die kron / Kegen Mitternacht. … Von wannen kömpt aber der Breutigam. Auß der mitten / wo die Hitze das licht gebüred / vnd ferdt kegen mitternacht … / da wird das licht Helle. [emphasis in original][Translation: Look. I am going to tell you a secret. The time has come for the bridegroom to crown his bride. Guess, dear fellow, where is the crown to be found? Toward midnight. … Whence issues the bridegroom? From the middle, where the heat gives birth to the light, shooting towards midnight … That is where the light is growing bright][German original & English translation: Jacob Boehme, Aurora (Morgen Röte imauffgang, 1612) …, transl. Andrew Weeks, Brill: Leiden / Boston 2013, 324-325]

It’s a very small example, but it demonstrates the problem. Boehme spoke about “midnight,” not the North: that translation came from Saint-Martin. Evola did not know this because he never bothered to check the original source. The point is simple: it is only on the basis of strict philological criticism along such lines that one can possibly evaluate the truth of any of the countless historical claims on which Evola builds his narrative. If one would take the (considerable) trouble of doing so, then the narrative would quickly start crumbling before one’s gaze. One would discover the enormous extent to which Evola was relying on dated, questionable, or wholly corrupt sources and on scholarly interpretations riddled with assumptions that often tell us more about the authors and their culture or personal preoccupations than about the texts and traditions they were studying. So are we simply dealing here with the typical naïvety and credulity of an amateur historian? I don’t think so. I am convinced that Evola’s highhanded statements about the total irrelevance of historical scholarship reflect an acute awareness on his part that these methods and technical tools had the power to undermine and destroy everything he wanted to say. If he dismisses textual criticism or philological analysis ex cathedra, describing them as the feeble props of deluded ignorants, this is because he knows that in reality they are deadly weapons against which his claims would be utterly helpless. Better discredit your critics in advance so that your readers will not even bother taking their arguments seriously. Better make use of the popular and populist resentment of “academics” in their ivory tower, of all those “specialists” who are making everything so difficult instead of telling a clear and simple story that normal people can understand. We find a similar strategy in the current conservative and rightwing campaigns of denying climate change (Trump: “just look out the window!”), undermining the credibility of science and academic research, attempting to defund Humanities programs, and spreading the trope of “alternative facts”. Science and scholarship are inconvenient to these antimodernists because they hinder them in saying what they want to say and doing what they want to do. Never let evidence stand in the way of a good story. We find the same approach in Evola. In sum, I do not think he doesn’t take historians seriously, on the contrary: he is afraid of them. He knows that his weapons are no match for theirs, and so he seeks to avoid a direct confrontation.

Transpolitical Conservative Liberalism

If Evola’s grand narrative of historical decline is a fantasy, then does this leave us with anything worth salvaging? Even if one does not accept his specific understanding of “Tradition,” one might still be inclined to agree in general terms with the idea that premodern cultures were superior and modernization is therefore a process of decline instead of progress. Or instead of thinking in terms of either decline or progress, one might argue that traditional and modern societies both come at a price, so we need to strive for a healthy balance between the advantages and disadvantages of both, rather than making an either/or choice. This would be my position. Now it is very interesting to observe that, whatever the official ideologies might say, a deep longing for premodern conditions is by no means restricted to the Right wing of the political spectrum but is widespread among its “progressive” opponents as well. While reading Revolt, I was struck by the structural parallels with one of my own all-time favourite novels, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. It is well known that Tolkien’s work became something close to Holy Scripture among the Hippies during the 1960s and remains a classic in the Pagan community that came out of that era.

Obviously the enemy Saruman, with his “mind of metal and wheels,” mirrors the spirit of the Industrial Revolution and its destructive effects on nature (the Ents) and traditional communities (the Shire). In other words, he stands for modernization as a negative force. All readers of Tolkien instinctively take the side of the Hobbits (that is to say, of traditional culture) and the Elves (that is to say, of an elite culture that embodies high spiritual values). Quite as instinctively, they embrace the notion of a sacred “bloodline” of Kings who are destined to rule: it would be ridiculous to imagine a democratic Middle Earth where Aragorn would have to stand for election and get his legislation through parliament. Middle Earth is a traditional hierarchical society where everybody seems to accept his or her appointed rank and station, where families are intact, where men are real men and women are real women. It is inhabited by a whole series of higher and lower races (Elves at the top, Men in the Middle, Orcs at the bottom), and although these may form coalitions of friendship, it is well understood that ultimately they are supposed to stay in their own homelands. Nor would they wish otherwise: they are all proud of who they are and determined to protect their own culture. All of this is very clearly Conservative rather than “Liberal,” and Traditionalist rather than Progressive. Nevertheless, few readers understand Lord of the Rings as a political manifesto, and the novel has been widely experienced as a source of deep inspiration among such typical “Lefties” as the Hippies or most Pagans since the 1960s and their descendants or sympathizers up to the present. Of course some important footnotes should be added here, about ideological critiques of Tolkien on the Marxist Left and a deliberate embrace of traditional community values in Right-wing paganism. I’m aware of those complications, but what interests me here is the very broad base of readers (including myself) who appear to be perfectly capable of loving Lord of the Rings while rejecting right-wing authoritarianism and embracing universal “Liberal” human values such as freedom, equality, or democracy. So this is where it all gets very complicated. How can Tolkien’s perspective be so compatible with “Liberalism” and “the Left” if his ideal society exemplifies “Traditionalist” values promoted by authors on the “Right” such as Evola? It’s not a new problem either. During the 1960s and the following decades, the new Liberal culture that flourished on the Left in California and elsewhere in the United States embraced the scholarship on myth and symbolism associated with Eranos luminaries such as Carl Gustav Jung, Mircea Eliade, or Joseph Campbell. All these authors were very clearly conservatives, and much has been written about their relation with fascism and antisemitism; but the fact is that their work was experienced as deeply inspiring by American “Liberals” from the 1960s to the 1980s at least, and had a big influence on them.In short, there seems to be such a thing as Transpolitical Conservative Liberalism. Transpoliticalbecause it does not fit the neat ideological straightjacket of Left versus Right as conventionally understood. Conservativebecause it seeks to protect traditional values that are being threatened by the forces of “modern progress.” Liberalbecause it also believes in freedom and equality as values that should be universal for all human beings.

Human and Non-Human Conservatism

Evola is clearly not on that side though. His vision is marked by a strong and perfectly explicit emphasis on human inequality and an obsession with power and authority. Both elements are grounded in his personal psychology: they follow logically, in his case, from his deep-seated desire for absolute autonomy, that is to say, of total freedom for himself. From an early age on, so he tells us in his autobiography Path of Cinnabar , his all-consuming wish was to be absolutely free and autonomous: he did not want to be dependent on anything or anyone whatsoever. In terms of the German Idealist philosophers he was reading at the time, the whole of reality had to be subject to his absolute “I” (das Ich), which had to transcend the physical world and all its contingencies. So extreme was this desire that it brought him close to suicide, until a Buddhist fragment convinced him that in extinguishing his personal existence he would not be achieving freedom but would in fact be demonstrating his failureto achieve it. This is not the place to discuss the “magical” philosophy that came out of this realization, fascinating though it is. Important for our present concerns is Evola’s obsession, throughout his life, with the absolute power and unquestionable authority of a spiritual elite imagined as standing at the very top of a hierarchy: far above the ignorant masses, the contingencies of history, the limitations of material existence, or anything else that could possibly trouble its “non-human” purity and spiritual independence. Needless to add, such dreams are dreamed only by those who imagine that they themselves are lucky enough to stand at the top of the hierarchy. It is hardly surprising that such a man would be lacking in all human warmth and empathy for others. Evola was known as a cold fish who did not care about anyone but himself, and this is not the critique of a hostile outsider. Evola himself described his character in these terms:

A spontaneous detachment from what is merely human, from what is generally regarded as normal, particularly in the sphere of affection, emerged as one of my distinctive traits when I was still in my early youth … [S]uch a detached disposition … was the cause of a certain insensitivity and cold-heartedness on my part. But in the most important of all fields, his very trait is what allowed me to recognize those unconditioned values which are far removed from the perspective of ordinary men of my time (Path of Cinnabar, 6-7).

One has to agree, Evola was not an ordinary man. But much more important, given his current influence in Right-wing circles, is his utter contempt for human beings qua human beings. His commitment was explicitly to what he called the non-human. Any true spiritual values, as he understood them, had to be the exclusive preserve of a spiritual elite far above the common run of humanity. Whatever might happen to the masses of “ordinary” human beings was none of his concern: in his ideal world, they simply have to obey, and will be forced into submission if they dare to resist the dictates of “legitimate authority.” It is precisely in this regard that Evola’s Rightwing conservatism is utterly incompatible with the perspective of its “Liberal” counterparts – including those that share a deep concern with “Conservative” values. If Middle Earth is a Traditional society threatened by Saruman’s modernism, then Evola is much closer to the mindset of Sauron than that of Gandalf, Aragorn, the Hobbits, or the Elves. They are fighting against Mordor because it seeks to destroy everything that makes life worth living: freedom, peace, friendship, love, happiness, beauty, brotherhood, tolerance, mutual understanding, and the willingness to transcend boundaries of race and culture (exemplified, of course, by the friendship that develops between Legolas and Gimli). The traditional society they want to conserve and protect exemplifies precisely those values. Sauron, on the other hand, is obsessed with one thing only: power. He demands absolute authority, submission to his will.

One has to agree, Evola was not an ordinary man. But much more important, given his current influence in Right-wing circles, is his utter contempt for human beings qua human beings. His commitment was explicitly to what he called the non-human. Any true spiritual values, as he understood them, had to be the exclusive preserve of a spiritual elite far above the common run of humanity. Whatever might happen to the masses of “ordinary” human beings was none of his concern: in his ideal world, they simply have to obey, and will be forced into submission if they dare to resist the dictates of “legitimate authority.” It is precisely in this regard that Evola’s Rightwing conservatism is utterly incompatible with the perspective of its “Liberal” counterparts – including those that share a deep concern with “Conservative” values. If Middle Earth is a Traditional society threatened by Saruman’s modernism, then Evola is much closer to the mindset of Sauron than that of Gandalf, Aragorn, the Hobbits, or the Elves. They are fighting against Mordor because it seeks to destroy everything that makes life worth living: freedom, peace, friendship, love, happiness, beauty, brotherhood, tolerance, mutual understanding, and the willingness to transcend boundaries of race and culture (exemplified, of course, by the friendship that develops between Legolas and Gimli). The traditional society they want to conserve and protect exemplifies precisely those values. Sauron, on the other hand, is obsessed with one thing only: power. He demands absolute authority, submission to his will. The Faultline

Evola’s case has exemplary significance in the current political debate. What ultimately divides the “New Right” from its “Liberal” opponents is not the dilemma of Tradition versus Modernity, or Conservatism versus Progress: about those issues, difficult as they may be, it is possible to find common ground. Only one principle is not negotiable: that power and authority must be at the service of humanity, and not the other way around.

Published on August 04, 2017 05:52

June 17, 2017

The European New Right Doesn't Get It Right: The Danger of Manichaean Historiography

In an attempt to educate myself a bit about the European New Right, I’ve been reading two books about the movement: Tomislav Sunic’s 1988 dissertation Against Democracy and Equality and Michael O’Meara’s New Culture, New Right: Anti-Liberalism in Postmodern Europe (2013). I learned a lot, although perhaps not what the authors hoped I would.

Tomislav Sunic

Sunic’s book was republished by Arktos and has received much praise in rightwing milieus as a reliable introduction. Ironically though, the ENR's central representative Alain de Benoist in his Preface (p. 18) points out that the very title of the book is completely wrong: it shouldn't be about equality but egalitarianism! Unfortunately, Sunic doesn't seem to understand such basic distinctions and makes an utter mess of it. First, on pp. 132-135 he gives a quite adequate summary of what the liberal concept of equality actually means, with reference to the Declaration of Independence: "At bottom the democratic faith is a moral affirmation: men are not to be used merely as means to an end, as tools [etc.]" Each human being "has an equal right to pursue happiness; life liberty and the pursuit of happiness are his simply by virtue of the fact that he is a human being" (Milton Konvitz, quoted on p. 132). Clear enough, isn't it? One might think that Sunic understands it too: "When liberal authors maintain that all men are equal, it is not to say that men must be identical ... and liberalism has nothing to do with uniformity. To assert that all men are equal, in liberal theory, means that all men should be first and foremost treated fairly and their differences acknowledged" (p. 135).

Sunic’s book was republished by Arktos and has received much praise in rightwing milieus as a reliable introduction. Ironically though, the ENR's central representative Alain de Benoist in his Preface (p. 18) points out that the very title of the book is completely wrong: it shouldn't be about equality but egalitarianism! Unfortunately, Sunic doesn't seem to understand such basic distinctions and makes an utter mess of it. First, on pp. 132-135 he gives a quite adequate summary of what the liberal concept of equality actually means, with reference to the Declaration of Independence: "At bottom the democratic faith is a moral affirmation: men are not to be used merely as means to an end, as tools [etc.]" Each human being "has an equal right to pursue happiness; life liberty and the pursuit of happiness are his simply by virtue of the fact that he is a human being" (Milton Konvitz, quoted on p. 132). Clear enough, isn't it? One might think that Sunic understands it too: "When liberal authors maintain that all men are equal, it is not to say that men must be identical ... and liberalism has nothing to do with uniformity. To assert that all men are equal, in liberal theory, means that all men should be first and foremost treated fairly and their differences acknowledged" (p. 135). Bravo, well said - it would seem that Sunic gets it. But no. He then launches into a chapter (pp. 141) riddled with so many non sequiturs and sheer nonsense that it made my head spin. Instead of attacking the actual liberal notion of equality that he has just been describing, conservative authors and ENR sympathizers such as Hans J. Eysenck, Konrad Lorenz, Pierre Krebs and others are endorsed for attacking a bizarre straw man that is actually the opposite of what equality means. Suddenly the Declaration of Independence is supposed to say "that all human beings are absolutely identical" (Lorenz, quoted on p. 145), i.e. "that all people at birth are endowed with the same talents, and that all peoples possess the same energies" (Krebs, quoted on p. 146). What is so hard about seeing the difference between human rights (which should be equal) and human talents, abilities, or cultures (which obviously aren't all the same)? Why not have the honesty of acknowledging what was actually meant, i.e. that all human beings should have equal rights to life, liberty & happiness, regardless of whether they are smart or dumb, talented or untalented, educated or uneducated, and of course regardless of their race, gender, culture, beliefs and so on? But no, that's clearly not what Sunic wants to say, so to hell with logic. From here on the argument degenerates into a claim that defending the equal right of all human beings to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" (Decl. of Ind.) means justifying "genocidal crusades" (Bérard, quoted on p. 150) and ultimately leads to "state terror, deportations, and the imprisonment of dissidents in psychiatric hospitals in the name of higher goals, democracy, and human rights" (p. 157). Ehm, am I missing something here?? Did it ever occur to Sunic and his sympathizers that these horrors mean what they obviously mean, i.e. that - far from exemplifying an ideology of "human rights" - the sad realities of (neo)"liberal" politics and global domination keep betraying and making a mockery of the basic human values that they should in fact be defending? In other words, it seems to me that Sunic should be attacking the practices of (neo)liberalism in the name of equality and human rights instead of conflating the two. But I'm afraid all of this is not about logic or clear thinking. It's about pursuing an agenda inspired by emotional resentment, regardless of arguments or evidence. If this is the intellectual level on which the ENR is attacking "liberalism" and equality, then I’m afraid they have a long way to go.

Michael O’Meara

But is Sunic’s book representative? When I posted these reflections on Facebook, several friends mentioned Michael O’Meara’s New Culture, New Right: Anti-Liberalism in Postmodern Europe (Arktos 2013) as a more solid and reliable introduction to the topic, so I ordered and read it. But unfortunately I cannot say I’m impressed with this book either, to say the least. It looks a bit more solid, it’s better written, and it has an extensive apparatus of footnotes that gives it an “academic look and feel”. There’s certainly a lot of research behind it, and the apparatus is a treasure trove of references to relevant primary and secondary sources. Nevertheless, it quickly became evident that I was reading not a historical analysis of the ENR interested in balance and nuance, but a political pamphlet grounded in ideological tunnel vision. The very first pages already set the tone, when O’Meara discusses the aftermath of what he calls the “Second European Civil War” and makes clear that for him the “liberation” of France was in fact an “occupation” by the hostile forces of American Liberalism, which proceeded immediately to “decimate” what he calls the Old Right in “a murderous purge”. Never mind the murderous Nazi regime that went before, which seems not worth mentioning in this context and is clearly not much of a problem for O’Meara (in providing figures of the number of casualties in this so-called épuration, he relies primarily on the neo-fascist “negationist” and explicit defender of National Socialism Maurice Bardèche). Of course it’s well known that after years of Nazi occupation, the reaction of revenge and “payback” after the liberation produced fresh horrors and tragedies; but O’Meara wants to speak of “murder” only when the victims are on the right. I find it illustrative that whenever he mentions Jews and Judaism we immediately encounter standard antisemitic stereotypes such as the image of the “rootless” cosmopolitan Jew with his “revolutionary” (read: anti-traditional) mentality and obsession with money and materialism. Most important is that, throughout his discussions, O’Meara never makes even the slightest attempt to understand his opponents’ point of view. Why be fair to those “Liberals” and their ideas? They are the enemy, so their perspectives are wrong and without any validity. No need to spend any time taking them seriously. Should one even bother to read such books? I think one should. Firstly because it’s important to do what O’Meara does not, that is to say, make a serious attempt at listening and understanding how your opponents look at the world and why. If we aren’t willing to make that effort we have no right to expect them to do any better. And secondly because O’Meara’s book is an excellent example of how historical narrative can be used for purposes of manipulation – or in other words, of the power of storytelling in historical writing. This is in fact an issue of enormous importance, and its relevance goes far beyond this one specific example. Whether we realize it or not, all of us are constantly exposed to such narratives, and they determine how we perceive what happens in the world around us. So we’d better be aware of how they work.

But is Sunic’s book representative? When I posted these reflections on Facebook, several friends mentioned Michael O’Meara’s New Culture, New Right: Anti-Liberalism in Postmodern Europe (Arktos 2013) as a more solid and reliable introduction to the topic, so I ordered and read it. But unfortunately I cannot say I’m impressed with this book either, to say the least. It looks a bit more solid, it’s better written, and it has an extensive apparatus of footnotes that gives it an “academic look and feel”. There’s certainly a lot of research behind it, and the apparatus is a treasure trove of references to relevant primary and secondary sources. Nevertheless, it quickly became evident that I was reading not a historical analysis of the ENR interested in balance and nuance, but a political pamphlet grounded in ideological tunnel vision. The very first pages already set the tone, when O’Meara discusses the aftermath of what he calls the “Second European Civil War” and makes clear that for him the “liberation” of France was in fact an “occupation” by the hostile forces of American Liberalism, which proceeded immediately to “decimate” what he calls the Old Right in “a murderous purge”. Never mind the murderous Nazi regime that went before, which seems not worth mentioning in this context and is clearly not much of a problem for O’Meara (in providing figures of the number of casualties in this so-called épuration, he relies primarily on the neo-fascist “negationist” and explicit defender of National Socialism Maurice Bardèche). Of course it’s well known that after years of Nazi occupation, the reaction of revenge and “payback” after the liberation produced fresh horrors and tragedies; but O’Meara wants to speak of “murder” only when the victims are on the right. I find it illustrative that whenever he mentions Jews and Judaism we immediately encounter standard antisemitic stereotypes such as the image of the “rootless” cosmopolitan Jew with his “revolutionary” (read: anti-traditional) mentality and obsession with money and materialism. Most important is that, throughout his discussions, O’Meara never makes even the slightest attempt to understand his opponents’ point of view. Why be fair to those “Liberals” and their ideas? They are the enemy, so their perspectives are wrong and without any validity. No need to spend any time taking them seriously. Should one even bother to read such books? I think one should. Firstly because it’s important to do what O’Meara does not, that is to say, make a serious attempt at listening and understanding how your opponents look at the world and why. If we aren’t willing to make that effort we have no right to expect them to do any better. And secondly because O’Meara’s book is an excellent example of how historical narrative can be used for purposes of manipulation – or in other words, of the power of storytelling in historical writing. This is in fact an issue of enormous importance, and its relevance goes far beyond this one specific example. Whether we realize it or not, all of us are constantly exposed to such narratives, and they determine how we perceive what happens in the world around us. So we’d better be aware of how they work.Manichaean Historiography

O’Meara’s book reflects a Manichaean style of historiography based upon the reification and essentialization of (in this particular case) “Liberalism” and “Tradition” as two hostile movements or forces that are supposed to have been battling one another since antiquity. If you trace the components of the narrative, which can be found in many variations elsewhere in the literature of the New Right, then it looks somewhat like this.

O’Meara’s book reflects a Manichaean style of historiography based upon the reification and essentialization of (in this particular case) “Liberalism” and “Tradition” as two hostile movements or forces that are supposed to have been battling one another since antiquity. If you trace the components of the narrative, which can be found in many variations elsewhere in the literature of the New Right, then it looks somewhat like this. The story of “Liberalism” begins with the “revolutionary spirit” of Judaism and its monotheist revolt against the stable traditionality of “pagan” culture, which used to ensure that people knew who they were and where they belonged. It continues in the universalizing tendency of Pauline Christianity, which no longer seeks to address just one people (the Jews) but sets its sight on the whole of humanity, understood as one homogeneous collection of individual souls that are equal before God and all need to find salvation. This approach is taken up by the Christian Church, which proceeds to conquer the pagan peoples of Europe and convert them to the new faith: the result is that local communities lose their autonomy and are expected to become parts of one Holy Roman Empire. While Roman Catholicism had a policy of absorbing “pagan superstitions” into its own framework, the fatal process of liberalization moves to its next level with the Protestant Reformation: now we have a situation of total war against paganism, in favour of an interpretation of the Christian faith that puts all emphasis on the isolated individual and its personal relation to God, thereby further eroding the traditional sense of community. Next we get to Descartes, whose emphasis on pure rationality creates the intellectual foundation for modern science and its “reign of quantity” at the expense of all qualitative features, which now become totally irrelevant, thus paving the way for the commodification of everything under capitalism. From there we get to the famous disenchantment of the world under the reign of industrialization, which proceeds to further tear traditional communities apart, resulting in an urban mass society of alienated individuals. In the wake of Protestantism and the scientific revolution, the next victim of Liberalism is the traditional notion of social and political hierarchy. The revolt of the “third estate” during the French Revolution leads finally to an ideology of social egalitarianism and hence to modern mass democracy, thereby legitimating a whole series of “emancipatory” movements: for instance, women or homosexuals begin to claim equal rights, non-white peoples (black slaves, the colonized) start doing the same, and so on. Due to their success, we no longer have a traditional European society with a “natural” hierarchy dominated by white males but a multicultural society based on the principle that “all men (and women) are equal”. This process moves into its logical end phase with the economization and commodification of everything, known as neoliberalism, and its ambition of a global egalitarian society of consumers.

So what is wrong with such a narrative? Perhaps even this short summary shows how plausible it can be made to look at first sight. I do not think the problem lies so much in the basic historical “facts” as such (although of course one may quibble about many details and especially with how they are framed), in O’Meara’s attempt at a critical analysis of the problems and dilemmas caused by modernization (a perfectly legitimate pursuit), in the fact that he tries to understand them from a broad historical perspective (equally legitimate), or in his radical rejection of modernity and his heartfelt wish for a return to “traditional” values (realistic or not, such wishes are understandable enough).

Rather, the core problem is quite simply that this polemical manifesto, like so many similar ones, derives it plausibility and persuasive power from a very common type of bad historiography. A first objection concerns the “presentist” approach to history: you begin with what worries you in the contemporary situation and then start cherry-picking for its causes back into the past to create a narrative that, predictably, culminates in the very phenomena you were trying to "explain" in the first place. A second and even more serious objection, on which I will be concentrating, is that the entire enterprise is built upon an essentialist approach to historical writing grounded in a very common type of mental delusion (see below) but that can be used to great rhetorical effect and has tremendous potential for political propaganda. Let me emphasize right away that O’Meara is not alone in this regard. The same structural problem is basic to countless other grand narratives of modernity, with Hegel as the classic example.

The Power of Reification

So why is this bad historiography? To put it as sharply as possible: because there is no such thing as a “historical process” – there are only historical events. This might sound like an exaggerated or hyper-theoretical claim, so allow me to explain. Egil Asprem has nicely made the basic point in his deconstruction of another so-called “historical process”, that of disenchantment:

Conceptualizations of disenchantment as a socio-historical process affecting modern societies imply rather abstract, top-down explanations of individual beliefs and actions: in these accounts, it is not so much individuals that define their reality, build societies, make choices, create and negotiate culture and meaning, as it is the overarching “systems”, “structures”, “worldviews” or “ideologies” that determine what individuals do and say (The Problem of Disenchantment, 47).

The same argument applies to “Liberalism”. O’Meara’s story derives its seductive power from the fact that it lends agency not to human beings but to abstract “forces” of which they are supposed to be the puppets. Hence readers are led to imagine the history of Western culture notas a series of events based on human actions, which could all have happened differently, but as one momentous battle that has been unfolding over time between two hostile forces (Tradition and Liberalism), each sticking to their own internal logic and dynamics until the bitter end. Within the economy of this dualism, Tradition is clearly on the side of Being, while Liberalism is on the side of Becoming: the former is imagined to exist in some kind of nonhistorical space (hence its supposed “naturalness” or “universality”, its association with “eternal values”, and so on) while the latter unfolds in historical time (and is therefore seen as unstable, contingent, und ultimately less “real”). The narrative makes them appear like spiritual or metaphysical entities that are invisibly at work, as the hidden secret of “external events” that we can observe with our senses. Thus we are told that history has been influenced by the “Jewish Spirit”, the “Spirit of Christianity”, the “Spirit of Capitalism”, the “Spirit of Liberalism”, and so on and so forth.

Spirits...

Entities you can't see...

John Gast, "American Progress" (1872)There is a good reason why we cannot see them, except in our imagination: they do not actually exist. What we need to get is that “Tradition” and “Liberalism” are not entities, forces, spirits, or realities at all. They are words, labels – no more, no less. The function of this particular type of words consists in highlighting and calling attention to structural similarities of an ideal or abstract nature. In themselves there is nothing wrong with such operations of mental comparison and abstraction: they are not just useful, but often indispensable in our continuous attempts at bringing some order to the world that surrounds us in time and space. However, that does not diminish the fact that they exist nowhere else but in our minds: they are mental tools that operate in our imagination. The problem is that our minds have learned to neglect this and hence misperceive the true nature of such concepts. Instead of seeing them for what they are, we imagine them to be somehow real, and this happens through a cognitive process that is known as reification or, in its strongest form, essentialization. It causes us to imagine, more or less vaguely, that there aresuch things as “Liberalism” or “Tradition” and that history can be seen as the story of their encounter. Sometimes we say that this story unfolds “on the stage of world history” – another nice example of how we imagine things that are not there. For where is that “stage”? Where are those “actors”? These are metaphors, but we tend to confuse them with realities.Why is all this a problem? Because once we start thinking along these lines – and it is perfectly natural for us to do so – we feel that we need to get involved and take sides. Do we identify with the hero on that stage or with the villain? And so we start glorifying one of those spirits or entities while demonizing everybody that we imagine to be standing on the other side. This is how we get Rightwingers depicting “Liberals” as enemies of humanity in league with the Forces of Evil, and Leftwingers depicting “Traditionalists” as – well, exactly the same.

John Gast, "American Progress" (1872)There is a good reason why we cannot see them, except in our imagination: they do not actually exist. What we need to get is that “Tradition” and “Liberalism” are not entities, forces, spirits, or realities at all. They are words, labels – no more, no less. The function of this particular type of words consists in highlighting and calling attention to structural similarities of an ideal or abstract nature. In themselves there is nothing wrong with such operations of mental comparison and abstraction: they are not just useful, but often indispensable in our continuous attempts at bringing some order to the world that surrounds us in time and space. However, that does not diminish the fact that they exist nowhere else but in our minds: they are mental tools that operate in our imagination. The problem is that our minds have learned to neglect this and hence misperceive the true nature of such concepts. Instead of seeing them for what they are, we imagine them to be somehow real, and this happens through a cognitive process that is known as reification or, in its strongest form, essentialization. It causes us to imagine, more or less vaguely, that there aresuch things as “Liberalism” or “Tradition” and that history can be seen as the story of their encounter. Sometimes we say that this story unfolds “on the stage of world history” – another nice example of how we imagine things that are not there. For where is that “stage”? Where are those “actors”? These are metaphors, but we tend to confuse them with realities.Why is all this a problem? Because once we start thinking along these lines – and it is perfectly natural for us to do so – we feel that we need to get involved and take sides. Do we identify with the hero on that stage or with the villain? And so we start glorifying one of those spirits or entities while demonizing everybody that we imagine to be standing on the other side. This is how we get Rightwingers depicting “Liberals” as enemies of humanity in league with the Forces of Evil, and Leftwingers depicting “Traditionalists” as – well, exactly the same.Reification can be defined as the process of making mental abstractions real by projecting them onto the world, and then allowing our actions to be guided by them (for a theoretical discussion, see pp. 579-582 here). Enormous simplifications are the inevitable result, and in the real world these can often be destructive in the extreme. Manichaean historiography based on reification (whether from the Left or from the Right) leads to false but seductive narratives that sacrifice historical complexity to the requirements of ideology – that is to say, to power. We are told that we need to make a choice and show what side we are on: “you are either with us or with the terrorists – choose!” Although I disagree with Eric

Eric VoegelinVoegelin’s notion of “gnostic politics” (tragically, his Cold-War imagination fell prey to the very same pathology he believed to be fighting), his description of what happens next is perfectly correct:

Eric VoegelinVoegelin’s notion of “gnostic politics” (tragically, his Cold-War imagination fell prey to the very same pathology he believed to be fighting), his description of what happens next is perfectly correct:[At issue is] the legitimation of violence as a spiritual act of punishment against the Powers which threaten the Light. The situation of the underlying party is terrible, because he is not merely a political opponent in the battle for power but, in the dream fantasy of the gnostic, a cosmic enemy in the war between Light and Darkness ("Gnostische Politik", 308; see discussion on pp. 29-36 here).

That is what happens, all the time (for some of the most influential cases, see discussion here). Instead of seeing people you start imagining Powers – forces of darkness at work in the world that are destroying everything you care about. You feel you must fight them. You tell yourself that your eyes are wide open and you see the truth. They cannot fool you anymore, you are seeing through the delusion! Your opponents, on the other hand, are clearly under the sway of evil. They are living in ignorance, hypnotized, they act like automata, unable to see how they are being manipulated by the powers that are running the show. So if you cannot convince them, you will have to fight them. Perhaps they are looking at you in exactly the same way? Well, that might be, but it doesn’t matter. The point is that they are wrong and you are right. You cannot allow yourself to try understanding their point of view. That would only weaken your resolve, and anyway, you already know all you need to know about them.

Contingency and Human Values

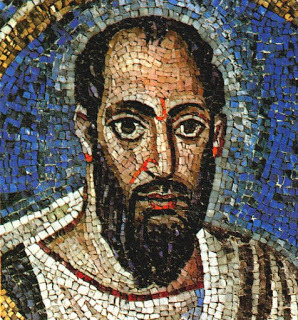

What does it mean to look at history in terms of contingency instead? It means taking a step back and focusing our attention, first of all, on what is really and undoubtedly there: human beings of flesh and blood like ourselves, and their actions in the world. Take the case of Paul the apostle. It is nonsense to see him as some kind of instrument through which Liberalism (or, for that matter, Christianity) was beginning its long campaign of conquering the world, en route towards its telos of a neoliberal world filled with McDonalds and Coca Cola. That is not what was happening in the first century CE. Something much more human and down-to-earth was happening. We are dealing with a Greek-speaking Jewish guy who, for reasons best known to himself (possibly the guilty trauma of having been a witness and accomplice, as argued by A.N. Wilson), got quite obsessed with the death by crucifixion of an obscure teacher from Nazareth called Jesus. He came up with some new and quite idiosyncratic ideas about its true cosmic significance for the world at large, and felt strongly that everybody should know. So he went on a mission to spread the word, and turned out to be really good at it. The rest, as one says, is history. The point is that none of it needed to have happened the way it did happen. If for some reason Paul’s (or rather, Saul’s) parents had not met, then he would never have been born – and it is absolutely impossible to say in what kind of world we would be living today. We can be sure though that it would look very different. However, his parents did meet; he was born; and he did what he did. What came out of it is what came out of it – not because it was meant to be, as if there were some great plan, but simply because this is what happened and not something else. What goes for Paul goes for Plato, Jesus, Muhammad, Constantine the Great, Luther, Descartes, Voltaire, Napoleon, Hitler, and all the rest. Human beings who happened to do what they happened to do.

What does it mean to look at history in terms of contingency instead? It means taking a step back and focusing our attention, first of all, on what is really and undoubtedly there: human beings of flesh and blood like ourselves, and their actions in the world. Take the case of Paul the apostle. It is nonsense to see him as some kind of instrument through which Liberalism (or, for that matter, Christianity) was beginning its long campaign of conquering the world, en route towards its telos of a neoliberal world filled with McDonalds and Coca Cola. That is not what was happening in the first century CE. Something much more human and down-to-earth was happening. We are dealing with a Greek-speaking Jewish guy who, for reasons best known to himself (possibly the guilty trauma of having been a witness and accomplice, as argued by A.N. Wilson), got quite obsessed with the death by crucifixion of an obscure teacher from Nazareth called Jesus. He came up with some new and quite idiosyncratic ideas about its true cosmic significance for the world at large, and felt strongly that everybody should know. So he went on a mission to spread the word, and turned out to be really good at it. The rest, as one says, is history. The point is that none of it needed to have happened the way it did happen. If for some reason Paul’s (or rather, Saul’s) parents had not met, then he would never have been born – and it is absolutely impossible to say in what kind of world we would be living today. We can be sure though that it would look very different. However, his parents did meet; he was born; and he did what he did. What came out of it is what came out of it – not because it was meant to be, as if there were some great plan, but simply because this is what happened and not something else. What goes for Paul goes for Plato, Jesus, Muhammad, Constantine the Great, Luther, Descartes, Voltaire, Napoleon, Hitler, and all the rest. Human beings who happened to do what they happened to do.All of which might sound almost trivial. But it is not: the implications reach very far, much farther than we commonly recognize. One often hears the objection that pure and utter contingency “empties history of any meaning”, beause it implies that history is just a string of random events, “one damn thing after another”. I disagree. Grand narratives based on reification do not discoverany true meaning in history. What they do is impute meanings on history, and while it is true that this can bestow a sense of purpose and personal fulfilment, the results can be utterly destructive too. Does this mean then that in fact there is no meaning or value to be found in the world? On the contrary! All it means is that if you look for it in “the historical process”, in some kind of political ideology or theology of salvation, then you’re looking in the wrong place. You find it in a meaningful life. And here, I think, lies the real tragedy of political ideologies, whether from the “Left” or from the “Right”. Although their very power and motivation comes from a deep and genuine concern with protecting important human values (how can we lead a meaningful life under conditions of modernity?), those who take it upon themselves to impose such values infailingly end up sacrificing real human beings on the altar of “the greater good”. In the end, they care more about ideas than they care about people.

Getting Real

As formulated by Mark Lilla in a wise and perceptive discussion of reactionary thinking, “when it comes to understanding history we are still incorrigibly reifying creatures” (The Shipwrecked Mind, 134):

As formulated by Mark Lilla in a wise and perceptive discussion of reactionary thinking, “when it comes to understanding history we are still incorrigibly reifying creatures” (The Shipwrecked Mind, 134):One needs not have read Kierkegaard or Heidegger to know the anxiety that accompanies historical consciousness, that inner cramp that comes when time lurches forward and we feel ourselves catapulted into the future. To relax that cramp we tell ourselves we actually know how one age has followed another since the beginning. This white lie gives us hope of altering the future course of events, or at least of learning how to adapt to them. There even seems to be solace in thinking that we are caught in a fated history of decline, so long as we can expect a new turn of the wheel, or an eschatological event that will carry us beyond time itself. … [T]throughout history [this apocalyptic imagination] has … provoked extravagant hopes that were inevitably disappointed, leaving those who held them even more desolate. The doors to the Kingdom remained shut, and all that was left was memory of defeat, destruction, and exile. And fantasies of the world we have lost. (Ibid., p. 135, 137).

What makes New Right narratives so seductive is the fact that they respond to problems that are perfectly real and important. The ideology of neoliberalism has created a terrible mess, and many of its basic assumptions need to be reconsidered. But to address the enormous problems that we are facing and not make matters worse, we need to stop fooling ourselves and get real about what really counts: not the purity of some “Traditional” or “Liberal” ideal that exists nowhere but in our imagination and has never existed anywhere else, but the suffering of people and the damage done to the world. Both Traditional andLiberal ideals can be excellent guidelines, and they are by no means so mutually exclusive as their fanatical apologists would like to suggest. But the point is that they are not realities. They are ideals, and as such they will always be hovering on the far horizon, at the edge of our vision or just beyond. We cannot reach them, and that is good, for absolute purity is a deadly thing. But they can be sources of inspiration, beacons of hope, and we can try to move into their general direction.

In the words of Annie Dillard, we are all in the same boat (or rather, in her story it is an ice floe), on our way towards the Pole of Relative Inaccessibility. Let's face it: we shouldn't expect to arrive there anytime soon. It's total chaos on that floe, but we're all on it together. So while we're all there and have nowhere else to go, we’d better learn to get over ourselves and try treating our fellow-travelers the way we’d like to be treated ourselves. Listening to what they have to say would not be a bad beginning.

Published on June 17, 2017 02:06

The European New Right Doesn't Get It Right

I've been making an attempt to educate myself a bit about the European New Right, and decided to read Tomislav Sunic's 1988 dissertation Against Democracy and Equality republished by Arktos and much praised in rightwing milieus as a reliable introduction. Ironically though, the ENR's central representative Alain de Benoist in his Preface (p. 18) points out that the very title of that book is completely wrong: it shouldn't be about equality but egalitarianism. But Sunic doesn't seem to understand such basic distinctions and make an utter mess of it. First, on pp. 132-135 he gives a quite adequate summary of what the liberal concept of equality actually means, with reference to the Declaration of Independence: ""At bottom the democratic faith is a moral affirmation: men are not to be used merely as means to an end, as tools [etc.]" Each human being "has an equal right to pursue happiness; life liberty and the pursuit of happiness are his simply by virtue of the fact that he is a human being" (Milton Konvitz, quoted on p. 132). Clear enough, isn't it? One might think that Sunic understands it too: "When liberal authors maintain that all men are equal, it is not to say that men must be identical ... and liberalism has nothing to do with uniformity. To assert that all men are equal, in liberal theory, means that all men should be first and foremost treated fairly and their differences acknowledged" (p. 135). Bravo, well said. So it would seem that Sunic gets it. But then he launches into a chapter (pp. 141) riddled with so many non sequiturs and sheer nonsense that it made my head spin. Instead of attacking the actual liberal notion of equality that he has just been describing, conservative authors and ENR sympathizers such as Hans J. Eysenck, Konrad Lorenz, Pierre Krebs and others are endorsed for attacking a bizarre straw man that is actually the opposite of what equality means. Suddenly the Declaration of Independence is supposed to say "that all human beings are absolutely identical" (Lorenz, quoted on p. 145), i.e. "that all people at birth are endowed with the same talents, and that all peoples possess the same energies" (Krebs, quoted on p. 146). What is so hard about seeing the difference between human rights (which should be equal) and human talents, abilities, or cultures (which obviously aren't all the same)? Why not have the honesty of acknowledging what was actually meant, i.e. that all human beings should have equal rights to life, liberty & happiness, regardless of whether they are smart or dumb, talented or untalented, and of course regardless of their race, gender, culture, beliefs and so on? But no, that's clearly not what Sunic wants to say, so to hell with logic: from here on the argument degenerates into a claim that defending the equal right of all human beings to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" (Decl. of Ind.) means justifying "genocidal crusades" (Bérard, quoted on p. 150) and ultimately "state terror, deportations, and the imprisonment of dissidents in psychiatric hospitals in the name of higher goals, democracy, and human rights" (p. 157). Ehm, am I missing something here?? Did it ever occur to Sunic and his sympathizers that these horrors mean what they obviously mean, i.e. that - far from exemplifying an ideology of "human rights" - the sad realities of (neo)"liberal" politics and global domination keep betraying and making a mockery of the basic human values that they should be defending? In other words, Sunic should be attacking the practices of (neo)liberalism in the name of equality and human rights instead of conflating the two. But I'm afraid all of this is not about logic or clear thinking; it's about pursuing an agenda inspired by emotional resentment, regardless of arguments or evidence. If this is the intellectual level on which the ENR is attacking "liberalism" and equality, then they have a long way to go.

I've been making an attempt to educate myself a bit about the European New Right, and decided to read Tomislav Sunic's 1988 dissertation Against Democracy and Equality republished by Arktos and much praised in rightwing milieus as a reliable introduction. Ironically though, the ENR's central representative Alain de Benoist in his Preface (p. 18) points out that the very title of that book is completely wrong: it shouldn't be about equality but egalitarianism. But Sunic doesn't seem to understand such basic distinctions and make an utter mess of it. First, on pp. 132-135 he gives a quite adequate summary of what the liberal concept of equality actually means, with reference to the Declaration of Independence: ""At bottom the democratic faith is a moral affirmation: men are not to be used merely as means to an end, as tools [etc.]" Each human being "has an equal right to pursue happiness; life liberty and the pursuit of happiness are his simply by virtue of the fact that he is a human being" (Milton Konvitz, quoted on p. 132). Clear enough, isn't it? One might think that Sunic understands it too: "When liberal authors maintain that all men are equal, it is not to say that men must be identical ... and liberalism has nothing to do with uniformity. To assert that all men are equal, in liberal theory, means that all men should be first and foremost treated fairly and their differences acknowledged" (p. 135). Bravo, well said. So it would seem that Sunic gets it. But then he launches into a chapter (pp. 141) riddled with so many non sequiturs and sheer nonsense that it made my head spin. Instead of attacking the actual liberal notion of equality that he has just been describing, conservative authors and ENR sympathizers such as Hans J. Eysenck, Konrad Lorenz, Pierre Krebs and others are endorsed for attacking a bizarre straw man that is actually the opposite of what equality means. Suddenly the Declaration of Independence is supposed to say "that all human beings are absolutely identical" (Lorenz, quoted on p. 145), i.e. "that all people at birth are endowed with the same talents, and that all peoples possess the same energies" (Krebs, quoted on p. 146). What is so hard about seeing the difference between human rights (which should be equal) and human talents, abilities, or cultures (which obviously aren't all the same)? Why not have the honesty of acknowledging what was actually meant, i.e. that all human beings should have equal rights to life, liberty & happiness, regardless of whether they are smart or dumb, talented or untalented, and of course regardless of their race, gender, culture, beliefs and so on? But no, that's clearly not what Sunic wants to say, so to hell with logic: from here on the argument degenerates into a claim that defending the equal right of all human beings to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" (Decl. of Ind.) means justifying "genocidal crusades" (Bérard, quoted on p. 150) and ultimately "state terror, deportations, and the imprisonment of dissidents in psychiatric hospitals in the name of higher goals, democracy, and human rights" (p. 157). Ehm, am I missing something here?? Did it ever occur to Sunic and his sympathizers that these horrors mean what they obviously mean, i.e. that - far from exemplifying an ideology of "human rights" - the sad realities of (neo)"liberal" politics and global domination keep betraying and making a mockery of the basic human values that they should be defending? In other words, Sunic should be attacking the practices of (neo)liberalism in the name of equality and human rights instead of conflating the two. But I'm afraid all of this is not about logic or clear thinking; it's about pursuing an agenda inspired by emotional resentment, regardless of arguments or evidence. If this is the intellectual level on which the ENR is attacking "liberalism" and equality, then they have a long way to go.

Published on June 17, 2017 02:06

April 30, 2017

The Cure (or: Confessions of a Liberal Anti-Neoliberal, with Recommendations)