Nate Silver's Blog, page 96

October 5, 2017

How Our 2017 College Football Playoff Predictions Work

FiveThirtyEight’s College Football Playoff forecast model is in some ways both my most favorite and my least favorite of the many statistical models we publish. That’s because, instead of trying to predict the games themselves — we mostly1 defer to ESPN’s Football Power Index for that — we try to predict the behavior of the small group of human beings who make up the playoff selection committee. This is a lot of “fun,” but also quite a challenge.

It’s a challenge not necessarily because the selection committee is inherently unpredictable. Most of the time, several of the playoff participants turn out to be fairly obvious, and our model has correctly predicted 11 of 12 playoff participants in the three years of its existence so far.2

The goal of a statistical model, however, is to represent events in a formal, mathematical way, and ideally, you’d like to be able to do that with a few relatively simple mathematical functions. Simpler is usually better when it comes to model-building. That doesn’t really work in the case of the selection committee, however. We finally have a reasonable amount of data to work with — 2017 will be the fourth year of the playoff. And what we’ve found is that even though our model can do a reasonably good job of anticipating the committee’s behavior, it has to account for the group behaving in somewhat complicated ways.

We discovered in 2014, for example — when the committee excluded TCU from the playoff despite the team holding the No. 3 spot in the committee’s penultimate rankings — that it isn’t always consistent from week to week. Instead, it can partly re-evaluate the evidence as it goes. For example, if the committee has an 8-0 team ranked behind a 7-1 team, there’s a reasonable chance that the 8-0 team will leapfrog the other in the next set of rankings even if both teams win their next game in equally impressive fashion. That’s because the committee defaults toward looking mostly at wins and losses among power conference teams while putting some emphasis on strength of schedule and less on margin of victory or “game control.” Therefore, our model does the same thing, based on a version of Elo ratings that attempts to mimic the committee’s behavior, along with a separate formula based simply on wins and losses. (For a more formal description of how our model works, see here.)

We’ve added other wrinkles over the years. Before the 2015 season, for example, we added a bonus for teams that win their conference championships, since the committee explicitly says that it accounts for conference championships in its rankings (although exactly how much it weights them is difficult to say).3 And late last year, we added an adjustment for head-to-head results, another factor that the committee explicitly says it considers. The committee has been a bit more consistent about applying this criterion, according to our testing. If two teams have roughly equal résumés but one of them won a head-to-head matchup earlier in the season (say, Oklahoma over Ohio State), it’s a reasonably safe bet that the winner will end up ranked higher.

Still, there are no guarantees. Our college football forecasts — like all of our forecasts at FiveThirtyEight — are probabilistic. Not only do we account for the uncertainty in the results of the games themselves, but also the error in how accurately we can predict the committee’s ratings. I spent some time this week evaluating our model’s published forecasts from 2014 to 2016 and found that they were pretty well-calibrated. That is to say, teams that are given a 60 percent chance of making the playoff will actually make the playoff about six out of 10 times and fail to do so about four out of 10 times over the long run. Because the potential for error is greater the further you are from the playoff, uncertainty is higher the earlier you are in the regular season. As of the launch of our forecast in early October, for example, as many as 15 or 20 teams still belong in the playoff “conversation.” That number will gradually be whittled down — probably to around five to seven teams before the committee releases its final rankings.

We’ve made a few additional changes in preparation for launch this year, which I’ll briefly describe here:

First, we’re using the AP poll as a proxy for the committee’s rankings until the committee releases its first set of rankings on Oct. 31 . This change has allowed us to launch our forecast earlier than in past seasons. (We’d previously waited until the committee’s first rankings were out.) Our model builds in additional uncertainty while the AP poll is being used, to account for the fact that the committee, which is made up mostly of former coaches and athletic directors, doesn’t size up the teams in quite the same way that the media voters in the AP poll do.

Second, game-by-game forecasts are now based on a combination of FPI ratings and committee (or AP) rankings, instead of solely FPI. We think FPI is a really good system, and we’re not saying that just because it was developed by our ESPN colleagues — it’s done an excellent job of predicting games over the past three years. In our testing this year, however, we found that accounting for the committee’s rankings (or the AP’s rankings before the committee’s rankings are available) contributes some predictive power (in addition to FPI). So game predictions are now based 75 percent on FPI and 25 percent on the rankings.4

And, finally, our system now gives teams from power conferences more advantages, because that’s how human voters tend to see them. We’ve calculated our Elo ratings back to the 1988 college football season. Between each season, ratings are reverted partly to the mean to account for roster turnover and so forth. In a change this year, teams are now reverted to the mean of all teams in their conference, rather than to the mean of all FBS teams. Thus, teams from power conferences — especially the SEC — start out with a higher default rating.5 This both yields more accurate predictions of game results and better mimics how committee and AP voters rank the teams. For better or worse, teams from non-power conferences (except Notre Dame) rarely got the benefit of the doubt under the old BCS system, and that’s been the case under the selection committee as well. In addition, we’ve made the conference championship bonus larger for teams from well-rated conferences; this also improves predictive accuracy.

Our forecasts will update at the end of each game, as well as when new AP rankings or new committee rankings are released. We hope you’ll have fun following the season with us.

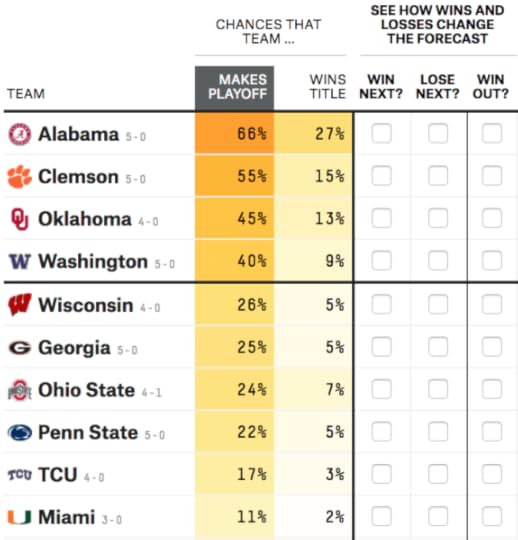

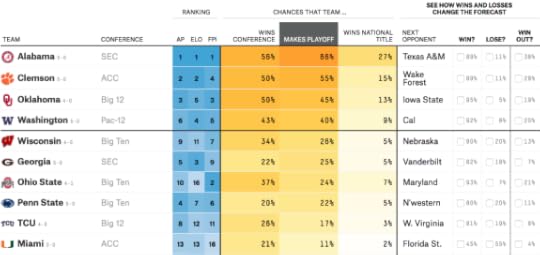

2017 College Football Predictions

2017 College Football PredictionsUpdated after every game and new College Football Playoff selection committee ranking (or AP Top 25 poll before Oct. 31, when the first ranking is released)

How this works: Our model uses the College Football Playoff (CFP) selection committee’s past behavior and an Elo rating[a][b]-based system to anticipate how the committee will rank teams, accounting for factors that include record, strength of schedule, conference championships won and head-to-head results. It also uses ESPN’s Football Power Index (FPI) and the committee’s rankings to forecast teams’ chances of winning. (Before Oct. 31, when the CFP will release its first rankings, the AP Top 25 poll is used instead.) The teams included above are each in the top 25 in at least one of the three rankings we use in our model: FPI, the Elo-based rating or CFP/AP. Every forecast update is based on 20,000 simulations of the remaining season. Full methodology »

By Jay Boice, Nate Silver, Reuben Fischer-Baum and Rachael Dottle.

Does The Media Cover Trump Too Much? Too Harshly? Too Narrowly?

In this week’s politics chat, we talk about a new study of how the media is covering President Trump. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Hey, everyone! Pew Research Center came out with a super interesting report this week examining how the media is covering the Trump administration and how that coverage differs by the political leanings of each outlet. So it seems like a good moment to ask some questions about how we’re doing.

Are media outlets too focused on President Trump, and thus missing issues like Puerto Rico or misrepresenting issues by viewing them through a Trump lens?

Is the press too negative toward Trump?

Is the media too desperate to cover Trump in old models?

Rather than throwing stones without any self-reflection — [cough] Nate [cough] — let’s also grade ourselves on each of these!

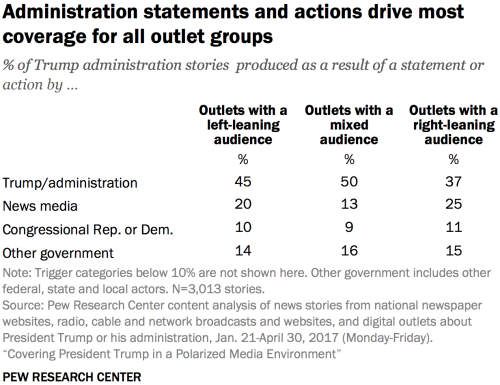

So, to start us off with No. 1, here’s an interesting table from the Pew report showing what “triggered” Trump administration coverage:

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): It strikes me, at first glance, that Trump might not be an outlier on this — the president is often covered through what he says and does. Pew doesn’t have a historical comparison for these numbers, but I would guess that a lot of former President Obama’s coverage was driven by his speeches/initiatives — maybe not his tweets, since they were dull.

micah: So, I don’t think the question is how it’s changed, but whether the balance is right.

Basically, about half of all stories are reactive.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief):

I hate to break it to everyone, but Poke is mad overrated.

— Clare Malone (@ClareMalone) October 3, 2017

Wow.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Yeah. That’s right. I subtweeted the group lunch.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): What trash.

clare.malone: Perry, take us back on message.

perry: Trump is doing and saying a lot, so I’m not myself concerned that coverage is driven by him. He is a unique president, breaking a lot of rules.

natesilver: I’ve come around to the idea that there’s nothing wrong in principle with the news cycle being driven by Trump’s tweets or off-the-cuff statements. It’s just that there isn’t much effort to distinguish which ones are important from which ones aren’t.

clare.malone: Is this where we tell our readers about journalism business models and how it’s more expensive to do reporting that involves investigation? Because honestly, I think that has to be taken into account.

But also, yes, there are stories that are maybe being neglected. Russia is more long-burning, and I think people are looking into it, but there’s fewer and fewer stories about Trump’s business interests overseas, for instance.

micah: Yeah, I mean, look … this is tricky and gets into cost, as Clare notes, but in general, I think a lot of outlets, including FiveThirtyEight, are too reactive.

perry: If we learned that most coverage is driven by Trump’s weekend tweets, that is not ideal. But him giving a speech at the U.N. or withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement is big news. Full stop.

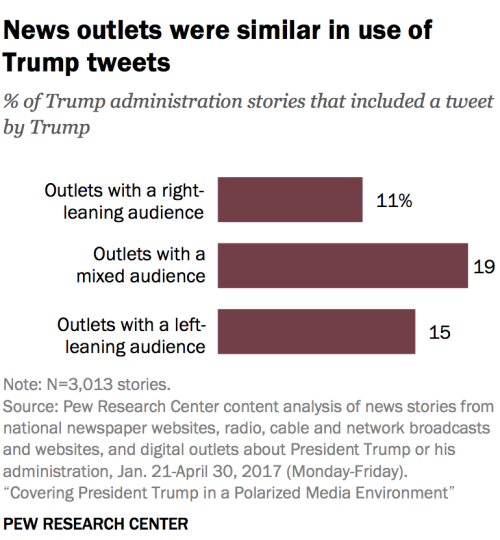

micah: Here are the shares of stories that included a Trump tweet, according to Pew, by the ideological leanings of the outlet:

harry: What’s interesting here is also how little of the coverage on right-leaning outlets (or outlets with right-leaning audiences) is driven by Trump.

Why would that be? Is more Trump bad for Trump? I’d argue that.

natesilver: Maybe we should ask — which stories should be covered more?

micah: I’ll start with our own house: We have a small team, so it’s difficult, but I wish we did more on what the federal agencies are up to. (Department of Justice, HUD, etc.)

perry: If I had these nine months over again, I would probably have covered Scott Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency more, what Tom Price was doing to break the Affordable Care Act more, and less on Steve Bannon v. Jared Kushner. In general, the agencies are undercovered and the White House is overcovered.

micah: jinx!

perry: So Micah and I are saying the same thing.

micah: Other outlets in a better position to do so could cover the North Korean conflict more, right? Or health care from a public health POV — what’s happening on the ground?

But IDK, it sounds like you all are pretty comfortable with a mostly Trump-focused media?

harry: He’s the president.

perry: One of my old colleagues (Alec MacGillis of ProPublica) did an excellent story on Ben Carson at HUD. Agencies are really hard to cover. This gets to Clare’s point about journalism models: A well-written story about identity politics may get more readers than a HUD story while taking 10 percent of the time.

And how the president speaks is important too.

natesilver: Yeah, the real answer might be that stories that don’t involve the White House have been undercovered. Like, we’ve published significantly fewer stories on criminal justice this year than we did a year or two ago, and most of the ones we’ve published have had a Trump lens, I’d assume.

micah: That’s correct.

clare.malone: And ProPublica is a really great, really unique place that cross-publishes content with other, bigger outlets. That’s why Alec has time and space and funding to do those big, great stories.

natesilver: In terms of Trump-related stories, I think North Korea needs to loom a bit larger in the conversation about him.

clare.malone: The nature of North Korea being a hermit state is part of the problem, of course. It’s a lot more smoke signals reporting.

There’s also Iran stuff.

natesilver: North Korea is not that easy a story to cover, necessarily, for a lot of reasons. But people need to know the stakes of the decisions that Trump makes, and North Korea illustrates those stakes — up to and including nuclear war. Sometimes, when reporters are equating his tweets about North Korea to his tweets about the NFL, that gets lost.

clare.malone: SNL, when it came back last week, had a good line in its opener about how Trump’s tweets are distractions.

We haven’t talked about that framing as much since the campaign, since now tweets are White House statements. But maybe we should more.

micah: If half of all our stories are spurred by Trump, aren’t news outlets a bit at his mercy? Like, many outlets (including FiveThirtyEight) were late in covering the devastation in Puerto Rico because, in part, Trump didn’t focus on it at first.

perry: Trump fired the FBI director, tried to dramatically reform American health care, has threatened to roll back huge parts of his predecessor’s achievements. I don’t regret covering Trump a lot.

We are at Trump’s mercy, yes. But isn’t he a bit at the media’s too? I have a hard time thinking Robert Mueller is appointed or the health care bill dies without the high media scrutiny.

natesilver: We haven’t covered the Russia story very much, but I don’t know if that’s a feature or a bug.

harry: I’m not Alec or a policy reporter in any real sense. But I can say our plan was to cover state legislatures a lot more had Hillary Clinton won the White House — we would have had divided government in Washington and little would likely have gotten done. (Although, little has gotten done with unified government.) That said, the fact is that Trump is the president. He says a lot of very unusual things as president. That deserves coverage. (I think not covering Russia that much is a feature, to be honest.)

natesilver: On Mueller/Russia, there certainly is a lot of news, but it also feels like left-leaning outlets spend a lot of time “connecting the dots” when there isn’t much news.

perry: Criminal justice. State politics. Police shootings. Yeah, there are a ton of issues I think I would have covered more if Clinton were president. But I don’t think we are covering irrelevant stuff. I would defend the coverage of the national anthem controversy even.

micah: One more thing from Pew on this:

perry: Yeah, Obama was covered in a similar way: heavy emphasis on politics and a few issues. This is maybe a bug of political journalism.

harry: As Perry notes, a larger percentage of the Obama news stories were about his “political skills” than for Trump.

clare.malone: Don’t you think some of this is people who are used to covering campaigns trying to find stories during nonelection times? And they don’t want to cover policy?

natesilver: I definitely won’t apologize for seeing things through a political, rather than policy, lens. I do think, though, that the media needs to consider the underlying scope and magnitude of the issues at play. The politics of health care matter a lot more than the politics of the NFL.

micah: OK, on to question No. 2: Is the coverage of Trump too negative?

Here’s what Pew found compared with other recent administrations:

clare.malone: Well, this might have to do with the fact that he is doing a worse job, almost objectively, of running a normal, relatively smoothly functioning administration.

Look at how many resignations, how much turnover.

micah: Very true. But like … those numbers are pretty stunning.

natesilver: I’m torn on this question. On the one hand, sure, if you’re covering a baseball team that went 62-100, the coverage has got to be very negative.

On the other hand, I think sometimes there’s a pile-on effect. It’s not that particular stories should be covered more positively, necessarily, but that the media won’t let go of relatively minor stories for days and days and days.

clare.malone: The “bad reputation” probably does then lead people to not give the White House the benefit of the doubt on things that might be more normal.

perry: Obama passed a huge stimulus bill early in his term. He was popular. I can’t recall a ton of major firings. There was no investigation of whether the Chinese had hacked John McCain’s email and released it to the public, or whether David Axelrod was involved in covering that up.

micah: How do you think we fare by this measure? (Negative vs. positive.)

natesilver: Ehh. tbh, Micah, we’re probably a little bit more pile-on-y in these chats and the podcasts. And not as much in the features we publish.

micah: Yeah, that seems right.

perry: I guess what I might say is that I don’t see this as necessarily evidence the press is doing something wrong. It might be. But I’m not so sure.

harry: Of note: Even the right-leaning outlets have been more neutral than positive. I don’t know if there is a lot of positive news for Trump.

natesilver: The press could focus more on the economic numbers, which have been relatively good lately. I think Trump has a legitimate gripe there.

perry: I would love to see the Obama 2011 or 2014 coverage data, when he was struggling.

micah: Yeah … as a site we’ve taken the stance that presidents have very little control over the economy and usually deserve far less blame and credit than they get. But we’re somewhat of an exception in that regard.

perry: I really disagree with Nate there. I think we should do as much as possible to stop suggesting presidents create economic growth or cause recessions.

micah: But Perry, wouldn’t outlets be covering good economic numbers more if Jeb Bush or Hillary Clinton were president?

In other words, I agree that they shouldn’t pretend any president controls the economy, but I feel like they do and perhaps in this case are doing the right thing for the wrong reasons?

In any case …

perry: I do want to talk about that negative number. Do you think that number is by itself a problem for media credibility?

Is that bad for our profession, no matter if we may think it is justified? Trump now has an official data point that the media covers him in a more negative way than Obama.

micah: Yeah, I think it’s problematic.

natesilver: It could be a problem if people are only hearing bad news about Trump from the “mainstream” media, sure. That doesn’t mean it should be a problem, in an ideal world. But it could be a problem in the real world.

micah: Right.

Let’s say, for the sake of this conversation, that’s it’s perfectly calibrated: 62 percent of coverage is negative and 62 percent of Trump’s actions are bad.

We still have one-third to four-tenths of the population that approves of Trump on any given day and are likely to feel put off by the overwhelmingly negative tenor of coverage.

But I don’t know how to fix or whether we should even try.

natesilver: The other issue is that the efforts to correct for this can be really clumsy. Like, I think 80 percent of the “Trump is pivoting!!!!” stories and 90 percent of the “Trump’s base still loves Trump!!!!!!!!!!” stories are driven by an effort to appear “fair,” and those are usually really shitty stories.

clare.malone: That’s where you have to cover more regional stories, not “do nicer stories about Trump.”

micah: Tone becomes really important too.

clare.malone: Lots of people voted for Trump because they thought national political perceptions of their lives were way off — that their realities were different from what national politicians were telling them they were. So, we should probably cover good things that are going on at those more state levels, along with talking about problems happening there.

perry: I actually think that the negative coverage of Trump comes in part from the media being based largely in big, racially diverse cities like New York and Washington and being biased in some ways toward multiculturalism, acceptance of Muslims, people who are transgender, Black Lives Matter protesters, etc.

That shapes how, say, the travel ban is covered.

clare.malone: I think that’s true, Perry — there are certainly implicit moral judgments about these policies that are coming through in news stories.

If not outright lines that say “this Trump activity is dangerous and un-American!”

natesilver: The immigration/Muslim ban is an interesting example here, for sure. It was covered as very major news at the time. I’m not sure that when people look back on Trump’s presidency, it’s going to be higher than like the 12th most important thing, though.

harry: 12th? It may not be higher than 25th. Granted, it was right at the beginning of the presidency.

micah: It was one of the first clear Trump policy actions.

clare.malone: mm, I dunno, Nate. It was a chaotic rollout the first week he was in office and it did really set a tenor.

perry: I think it was important, so I might disagree with Nate. But I think the tone of that coverage is different from how Trump’s tax plan is covered.

micah: It is often hard as an editor or reporter to separate when an action goes against an almost universally agreed-up moral good — inclusion, equality — vs. when it goes against a political belief.

natesilver: I’d argue that Charlottesville was also covered differently than it would have been if it were more diverse in different ways. On the one hand, there were like 20 news cycles about whether he was apologizing in the right way. That became ridiculous, at some point, and maybe there would have been less focus on that if the media were more dispersed geographically. On the other hand, the media seemed much more shocked by Trump taking a “both sides” position on Charlottesville than they should have been, given his past history with comments about race. And there likely would have been less of a shock if the media were more racially diverse.

harry: Well, the media seems very interested in his personality and conduct, so that shouldn’t be too surprising.

micah: Question No. 3: Is the media too desperate to cover Trump in old models and therefore missing stories?

For example: There’s been some debate about whether the news media should cover Trump’s mental state more. This was (mostly) not an issue for recent presidents.

perry: OK, so mental health. I’m just very leery of, after covering Trump negatively as this data shows, that the press should move toward “he has an undiagnosed mental illness.”

micah: Right, so is this an example of a story the press is not used to covering and so therefore isn’t covering?

perry: He might have some mental illness. But I remember watching a cable news panel discussing that, and immediately being uncomfortable. This was in the midst of the controversy over his comments about the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville. Trump was making comments that I thought perfectly aligned with his ideology, so it seemed odd to attribute them to his health.

micah: As we’ve written, psychiatrists are generally advised not to publically diagnose a public official they haven’t personally examined.

natesilver: I wouldn’t advocate for diagnosing Trump, per se. But I think there should be more coverage/consideration of his “mental fitness” rather than “mental health.” How often is he making thoughtful, rational decisions as opposed to rash, emotional ones?

clare.malone: Christie Aschwanden and I wrote a bit about whether candidates were too old to run for president back during the campaign. We looked at life expectancy based on some actuarial charts. The story came right after Hillary Clinton’s health scare, and there was some implication that as we age, things naturally start to go wrong.

I think that was a totally appropriate thing to cover during the campaign.

Whether the president has a mental disorder, well, I would be eager to talk to a physician who’d examined him and was willing to break doctor/patient confidentiality because they had concerns.

I do think it’s dangerous territory when we start to speculate in print without proof.

harry: I’d argue that if a woman said half the things Trump did, lots more people would call her “crazy” or “stupid.” (I’d also think there was no chance in heck she’d be elected.)

micah: I’m sorta torn between these two positions: I both think a president’s mental fitness is fair game, and I’m pretty confident the media would do a terrible job covering it.

natesilver: Look, let me put it more bluntly: The guy tweets and says crazy shit all the time. I know “crazy shit” isn’t a scientific term. But shouldn’t the media at least account for the possibility that he’s tweeting crazy shit because he’s actually “crazy”?

clare.malone: But wouldn’t everyone just be speculating? Now, if staff members start to confide to reporters that they’re worried, that’s a different story. This was a concern on Ronald Reagan’s staff in his second term.

micah: And then we end up in a world where people are making political judgments using the language of science — without the actual science.

natesilver: It’s not a court of law, though! You don’t have to prove things beyond the shadow of a doubt!

I just think the taboo about not speculating about the president’s mental health is being taken way too far — and leading people to try to rationalize too many of his actions.

perry: Is being erratic and unfocused and kind of mean on Twitter a mental health issue?

Or a jerk issue?

clare.malone: Jerk issue.

natesilver: If it’s the sort of behavior that might also lead him to, like, nuke North Korea in a fit of pique, I’d argue it’s pretty important to cover!

clare.malone: I mean, half of political twitter is mean-spirited.

*three-quarters

natesilver: Five quarters.

harry: Ladies and gentlemen, a statistical expert.

clare.malone: I don’t know, I think some of this is a bit of a futile debate.

perry: So Trump can’t be trusted on North Korea because he is perhaps incapable of calmly and rationally considering such an issue. I think Nate has moved me to think about this in a “state of his mind” kind of way. That seems right.

micah: Are there other instances where we need new models/techniques/approaches to cover Trump?

perry: I think my general concern with the current model is that it assumes: 1. that he is taking actions because that is how other presidents would approach an issue; 2. that he is doing things out of some smart analysis of politics; 3. that his staffers/advisers speak for him in any real way.

harry: Well, I still wonder if we have the right approach re: Twitter vs. “official” statements from the White House.

micah: I’m sick of the “how to treat Trump’s tweets” debate!

natesilver: I mean, this whole chat reflects ways in which “traditional” models are broken. Although, I’d say less “traditional” models than contemporary ones. Traditional reporting isn’t broken so much as the model centered on “winning the day” by building vapid narratives, which is a fairly modern invention.

harry: I guess my point is that Trump at a number of moments has undermined stuff members of his own administration have said. It’s not clear to me who is actually initiating actual policy.

How do you cover that?

micah: Right, so generally, I don’t think anyone, us included, has figured out how to treat statements (of any form) coming from this White House (Trump and everyone else).

It’s not clear what’s policy and what’s not. Or what will be followed up on and what won’t.

natesilver: I don’t think anybody has. I don’t think North Korea has any idea what to make of it either, for example.

micah: Right.

perry: Like, Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis this week said he supports the Iran deal. I have no idea what that means for this administration. It would have meant something if Ash Carter or John Kerry said something like that during the Obama administration.

micah: And, not to go backwards, but that’s what makes me really nervous about the White House being the impetus for such a high percentage of coverage.

perry: Interesting.

micah: Like, we don’t know how to read what the White House is saying, but we’re organizing most of our coverage based on what it’s saying.

natesilver: Can I make one slightly different point? We haven’t discussed race all that much in this conversation. But it’s interesting that mainstream journalistic outlets are more-or-less happy to accuse Trump of abetting racial resentment as a political tactic but would be very reluctant to actually call Trump a racist.

perry: I largely follow that approach myself.

harry: I’m not surprised by that at all, Nathaniel.

clare.malone: I think we’ve talked a bit about this — if not in chats, then offline — that describing a person’s racist actions is far enough. That you might lose people being willing to read along with your reasoning if you outright call him a racist. That you can leave that judgment up to the readers once you’ve presented them with the evidence.

micah: Yeah, I find the whole debate about what’s “in someone’s heart” pretty frustrating — isn’t it their actions that matter?

natesilver: I’m not sure I agree. It matters what makes Trump tick.

perry: Columbia Journalism Review just wrote a piece saying people should call Trump racist. So Nate is not taking a crazy stance here.

natesilver: To Clare’s point, we play it pretty carefully around this subject too. Not as carefully as other outlets. But we go 50 percent of the way there.

clare.malone: Readers aren’t stupid, is basically what I’m trying to say. Think critically, America!

harry: Lots of Americans think Trump is racist.

natesilver: At the same time, it’s important for journalists not to communicate in code.

clare.malone: I don’t think we do. But yes, I agree that there’s a danger that exists there with not calling things as we see them.

micah: Our philosophy, at least in theory, is to call words and actions “racist” when they are — rather than “racially charged” or something. As Clare said, though, we stop short of calling a person racist.

natesilver: We’re actually good about that, yeah. But other outlets take a very coded, jargon-y approach at times, especially when writing stories based on anonymous sourcing. You can decode those if you want — see Perry’s guide on anonymous sourcing — but I’m not sure if those stories are really serving the audience.

I’ll just say this: The media has lots of problems in how it covers Trump. We’ve just scratched the surface here. But these problems are also hard to solve and figuring them out in real time is tough.

October 2, 2017

Politics Podcast: Trump’s Response To Hurricane Maria

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS |

Embed

Embed Code

The U.S. is facing multiple crises: a mass shooting in Las Vegas, a humanitarian disaster in Puerto Rico and rising tensions with North Korea. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team zooms in on how the Trump administration has responded, in particular to Hurricane Maria’s devastating effects in Puerto Rico.

The crew also weighs the likelihood of Republicans in Congress passing tax reform legislation.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 30, 2017

The Media Needs To Stop Rationalizing President Trump’s Behavior

Whenever President Trump lashes out against someone or something in a way that defies traditional expectations for presidential behavior — for instance, his decision to criticize the mayor of San Juan, Puerto Rico, on Saturday morning after her town was just devastated by Hurricane Maria — it yields a debate about what was behind it. After Trump’s series of attacks on the NFL and its players earlier this month, for example, there were two major theories about what motivated his conduct.

The first theory is that it was a deliberate political tactic — or as a New York Times headline put it, “a calculated attempt to shore up his base.” We often hear theories like this after Trump does or says something controversial or outrageous. His response to the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August was sometimes explained in this way, for example. “Mr. Trump has always appreciated the emotional pull of questioning bias and fairness, especially with his white working-class base,” the Times wrote, portraying Charlottesville as an issue that drove a wedge between the Trumpian and the Republican establishment.

It’s also often claimed that Trump leans into controversies such as the NFL protests as a way to distract the media from other, more serious issues, such as the repeated Republican failures to repeal Obamacare, or the various investigations into Trump’s dealings with Russia. These claims also assume that Trump’s actions are calculated and deliberate — that he’s a clever media manipulator, always staying one step ahead of editors in Washington and New York.

The second theory is that the response was impulsive and primarily emotional. Trump initially began criticizing the NFL and NFL players at a rally last Friday in Huntsville, Alabama, including referring (although not by name) to former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick as a “son of a bitch” for protesting during the national anthem. Perhaps encouraged by the raucous response he received from the crowd, Trump went on a tweetstorm about the NFL, its owners and its players that lasted intermittently over the next several days. Somewhere along the way, he also disinvited former NBA MVP Stephen Curry from attending the White House ceremony scheduled to honor the NBA Champion Golden State Warriors. (Curry had already said that he didn’t like what Trump stood for and didn’t plan to attend.)

Not all of this — particularly not roping the popular Curry into the controversy — necessarily seemed all that “calculated” to me. Instead, it seemed to fit a different behavioral pattern: Trump is piqued by criticism and rarely backs down, especially when he’s challenged by women or minorities — such as Curry, the predominantly black NFL player pool, ESPN’s Jemele Hill, Khizr and Ghazala Khan, Judge Gonzalo B. Curiel, London Mayor Sadiq Khan, former Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly or Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, to take some of many examples.

I know what you, as an analytically inclined FiveThirtyEight reader, are probably thinking: Are these theories necessarily mutually exclusive? Couldn’t these responses reflect fits of emotional pique on Trump’s behalf — and yet also have the effect of pleasing his base, or distracting the media from health care and Russia?

Sure, they could. Trump’s base support isn’t quite as immovable as some pundits seem to assume — but public opinion on many issues such as Charlottesville quickly polarizes itself along partisan lines. And Trump’s tweets and insults often have the effect of upending the news cycle; covering Trump is in some sense covering one distraction after another.

But the theories are in conflict because they’re about the intent and motivation for Trump’s behavior and not necessarily its effects. The first theory says that Trump is calculating and rational; the second says that he’s impulsive and emotional. The first theory implies that Trump may be employing “racially charged” rhetoric and actions for political gain. The second implies that Trump himself may harbor degrees of racial resentment, and resentment toward women, and that it colors his response to news events. Either way, Trump’s actions could be politically effective or ineffective. (Trump’s approval rating declined slightly this week after his NFL comments, although it’s hard to know if they’re the reason why.) However, it seems important to know what motivates them. If Trump’s actions are driven by emotional outbursts more than calculated trollishness, that might predict a different response to how he deals with escalating tensions with North Korea, for example.

After Trump’s NFL remarks, you really could have argued either theory. In addition to the racial dynamics at play, Trump has some personal grievances with the NFL, including his failure to purchase an NFL franchise. But the protests from Kaepernick and others have been unpopular, and the response to them has been highly partisan. One can imagine Trump thinking it was effective politics to bring them up as a wedge issue, especially at a political rally in Alabama.

It’s much harder to describe some of Trump’s other outbursts — like those against the Khan family or Judge Curiel, for example — as representing a calculated political strategy. The same goes for Trump’s tweetstorm on Saturday morning about San Juan mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz, who had criticized the White House’s response to Hurricane Maria.

No matter how cynical one is, it’s hard to see what possible political benefit Trump could get from criticizing Cruz, whose city was devastated by Maria and remains largely without power and otherwise in crisis. Nor is the government’s response to Maria necessarily something that Trump wants to draw a lot of attention to. I’ve seen debates back and forth in the media over the past week about whether Trump’s response to Maria is analogous to the one former President George W. Bush had to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Trump’s dismissiveness toward Cruz almost certainly won’t help his side of the argument; instead, it will amplify growing criticism about how the government handled Puerto Rico and why Trump seemed to be more interested in the NFL protests than in his administration’s hurricane recovery plan.

I’m happy to acknowledge that Trump’s responses to the news are sometimes thought-out and deliberate. His criticisms of the media often seem to fall into this category, for example, since they’re sure to get widespread coverage and Republican voters have overwhelmingly lost faith in the media.

But at many other times, journalists come up with overly convoluted explanations for Trump’s behavior (“this seemingly self-destructive emotional outburst is actually a clever political strategy!”) when simpler ones will suffice (“this is a self-destructive emotional outburst.”). In doing so, they violate both Ockham’s razor1 and Hanlon’s razor — the latter of which can be stated as “never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” One can understand why journalists who rely on having close access to Trump avoid explanations that portray Trump as being irrational, incompetent or bigoted. But sometimes they’re the only explanations that make sense.

September 28, 2017

Never Tweet, Mr. President

I’m not embarrassed to admit that I feel a little empty inside if I don’t have a @realDonaldTrump tweetstorm to go with my morning coffee. But I’m decidedly in the minority on this question: Even voters who like President Trump don’t particularly care for him tweeting all the time. A Quinnipiac poll in August, for example, found that 69 percent of Americans — including 54 percent of Republicans — thought that Trump should stop using his personal Twitter account.

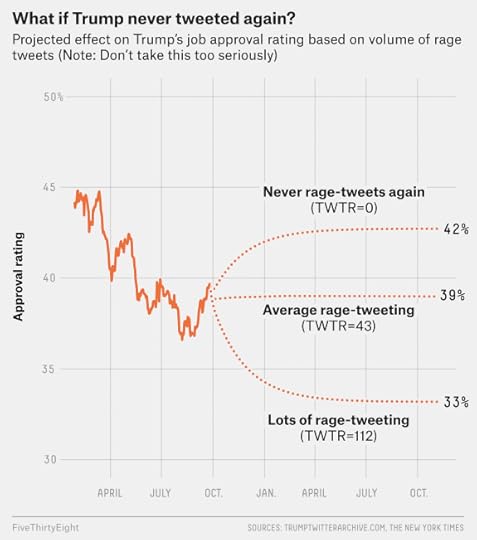

But do Trump’s tweets merely annoy voters or can they actually make it hard for him to stay on track and maintain his support with the American public? In last week’s edition of our politics podcast, I wondered if there were any relationship between the frequency with which Trump sends out incendiary tweets — such as his recent rants against the NFL and some of its players — and his approval ratings.

The answer is that there probably is such a relationship — periods when Trump sends out exclamatory or inflammatory tweets have been correlated with future approval-rating declines. But the relationship is somewhat noisy, and the causality isn’t totally clear. So we’d encourage you to read this story as a plausible hypothesis that will need further proof.

Here’s how I came to that (tenuous) conclusion. First, I created a statistic called Trump Weekly Twitter Rage (TWTR), which is calculated as follows:

Add one TWTR point for every insult Trump made on Twitter in the past seven days, as according to our friends at The New York Times’s Upshot blog.

Also, add one TWTR point for every exclamation point Trump has used in a tweet in the past seven days.

Neither of these is a perfect measure of Trump’s Twitter rage — the definition of an “insult” is somewhat subjective, and Trump sometimes uses exclamation points when he’s announcing boring meetings and not just when he’s angry — so combining them smooths out some of the rough edges.1 I calculated TWTR on days from Jan. 27 — a week after Trump’s inauguration — up through and including this Sunday, Sept. 24:

Trump’s Twitter rage peaked on July 29, shortly after the failure of the GOP’s health care bill, when he achieved a TWTR of 112. (The GOP’s health care bill has failed several times — including once this week — but the July failure was the particularly dramatic one when Sen. John McCain voted against the bill on the Senate floor.) And as of Sunday, his TWTR was 77 and rising. Trump is capable of raising his TWTR by as many as 29 points in a day — a record he achieved on Aug. 7, when he went on a rant about “fake news,” The New York Times and Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut, among other topics — so he could be a threat to break the record later this week.

The shifts in the president’s Twitter mood seem to be at least somewhat related to changes in his approval rating. April — after a Twitter lull early in the month — was something of a high point for Trump, with his approval rating reaching a comparatively good 42.0 percent by April 20. Early August (after Trump’s late July TWTR peak) was a nadir, by contrast, with his approval rating bottoming out at 36.6 percent on Aug. 7. More recently, a relatively calm period on Twitter in mid-September was associated with an uptick in Trump’s approval rating, although it’s since begun to decline slightly again.

Are these patterns statistically significant? The short answer is not quite, although it’s close. (For the long answer, see the footnotes.)2 In other words, the relationship between Trump’s rage-tweeting and his approval rating is probably negative — more Twitter rage means a less popular Trump — but we need more data to confirm it. We also don’t know about the causality — whether it’s the tweets themselves that could be hurting Trump or the underlying issues they bring up. It’s possible that Trump tweets more at times of political distress, such as after the failure of a health care bill, which could make the correlation somewhat spurious.

So exactly how much the tweets are hurting Trump is open to debate. At the same time, I feel reasonably confident in asserting that the tweets aren’t helping Trump as part of some supposed 13-dimensional chess strategy to rally his base or distract the media. Large majorities of the public dislike his tweeting, and his approval ratings have tended to decline after Twitter outbursts.

But just for fun — don’t take this part too seriously — I decided to run a simulation using our regression model to estimate how Trump’s approval rating would change over time given different levels of Twitter activity. The model assumes that Trump’s approval rating is somewhat mean-reverting over time — it tends to rise slightly after really bad periods and fall slightly after comparatively good ones — although also affected by his tweets.

If Trump never tweeted again,3 his approval rating would gradually rise to about 43 percent, the simulation estimates. Conversely, if he went on a Twitter bender and constantly tweeted at his maximum outrage level — the TWTR of 112 that he reached on July 29 — it would eventually fall to 33 percent. Again, I wouldn’t take any of this too seriously. But Trump’s tweets often dictate news cycles and amplify controversies — and they can even help to spark diplomatic crises and put the president in legal jeopardy. It’s not crazy to think the tweets have had consequences — mostly negative ones — for Trump’s popularity.

September 27, 2017

Is Trump’s NFL Critique Exploiting Divides Or Creating Them?

In this week’s politics chat, we dive into the motivations and effects of President Trump’s attacks on NFL players for protesting during the national anthem over police violence against black Americans. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): I’m going to throw three hypotheses about Trump’s attacks on the NFL at you. We’ll consider the evidence for/argue about each individually, but here are all three first:

Trump is attacking the NFL protests to shore up his base.

Trump is dividing the country.

Trump is a product of divides in the country that already existed.

So, first up …

Trump is attacking the NFL protests to shore up his base.

Do you buy this?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Sure, on some level he knows that his white, older base will like this, but I don’t think it’s all calculating — I definitely believe he holds these views. I’ll let Nate take the NFL grudge angle.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Not really. I think he’s attacking the NFL protests because he watches a lot of TV and has a short temper and doesn’t like it when he sees criticism of himself or the people he’s simpatico with, especially when it comes from minorities.

And, yeah, he also has a lot of beefs with the NFL, as he’d very much like to be part of the club of franchise owners.

perry: To Nate’s point about who Trump attacks and race … there’s this from The Washington Post:

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Well, if I can disagree slightly — I don’t think Trump woke up one morning and thought, “I need to shore up my base and therefore I’m going to attack the NFL.” Remember, his approval ratings have ticked up recently. Instead, I’d bet Trump felt a grievance and thought to himself that this might work as a political angle too. I bet the politics were secondary. Remember too, Trump tried and failed to buy my Buffalo Bills.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): I think the NFL thing popped into Trump’s head on Friday night in Alabama. The crowd applauded loudly. And then he doubled and tripled down on it because the controversy drew the right enemies — black athletes, elites, the media — and the right allies — veterans, white conservatives.

natesilver: I mean, it’s possible that this will have the effect of rallying his base. But I don’t think that was Trump’s intent, necessarily.

clare.malone: Didn’t Bon Jovi try to buy the Bills too?

harry: He did. We didn’t want Bon Jovi because we thought he might move the team.

micah: Should we spend less time focused on Trump’s motivations? I mean, do they even matter? The effects on the country are the same regardless, aren’t they?

clare.malone: Yes, but obviously he’s the accelerant on a flame that was already there.

micah: Save that thought!

perry: So I don’t think this was some deeply calculated move initially. But I think the tweets on Sunday and Monday reflect that Trump thinks he has a winning hand here.

natesilver: Motivations matter, in so far as we’re trying to build a “model” of Trump’s actions. And I think you sort of have to pick one hypothesis or the other. The way The New York Times put it is that “the vehemence was tactical, but also visceral.” I don’t really think that makes sense. Tactical and visceral are not quite antonyms, but it’s hard to be both at once.

micah: Can’t something be viscerally tactical? I think you’re oversimplifying how people’s motivations actually work, Nate.

natesilver: But he often digs in on losing issues, no? Going back to the feud with the Khan family or Judge Curiel, for instance.

perry: Right. Although I’m not sure this is a losing issue.

clare.malone: The pivot to NASCAR was pretty blatant by Trump as a move to appeal to his base … it kinda felt like a stereotype by him of who voted for him.

natesilver: I’ll just point out that his approval rating had gone up over the past few weeks — a period when he’d been quite quiet on Twitter. So the conventional wisdom that his base loves this stuff seems to be wrong.

micah: Well, it depends how we’re defining “base.”

harry: Can I cite some very preliminary polling data?

micah: Please.

harry: So SurveyUSA polled California on Trump and the NFL. The poll showed a fairly narrow split on the actions taken by the NFL players, but pretty much everyone agreed that Trump should stay the heck out of it. I know it’s California, but 82 percent, for example, said Trump should not have called the “player who kneeled” a “son of a bitch.”

perry: From the poll Harry just linked:

Asked about the national anthem in general and not about NFL protests in specific, 46% of residents statewide say it is wrong not to stand for the national anthem. 40% statewide say not standing is an acceptable way to protest.

This goes to the real issue, which is that while people don’t like how Trump behaved in this or many instances, he is tapping into views people have.

micah: I mean, this is a whole different conversation, but public support would seem to totally depend on how you describe what’s going on. (Our colleague Kathryn is reporting on this.) But is all this about …

Oppression of black Americans?

Respect for the country/flag?

Free speech/unity?

Which of those you prioritize makes a big difference. Colin Kaepernick, who started this, says No. 1. Trump says No. 2. NFL mostly says No. 3.

Of course, this all started with No. 1.

clare.malone: I think where most people are confused about how they feel is probably No. 2.

micah: Yes, and that’s where Trump is on the safest ground, most likely, in terms of public opinion.

natesilver: But maybe the public doesn’t care about the details of the controversy so much as that Trump’s just yammering on and on about it while Puerto Rico is without electricity and there’s a major health care debate and a million other things are going on.

clare.malone: A lot of people grew up with the habit of saying the pledge at school, waiting for the anthem to play — it’s just so ingrained that it makes sense to me that it’s taking awhile for people to wrap their heads around the protest, even if they’re in favor of the free speech right to kneel.

perry: In terms of Trump, yes, he would be better off talking about other issues. I feel like his numbers went up slightly after the debt deal with Democrats. That is why I agree with Nate: This is not some brilliant tactical move.

natesilver: We’ve actually got some research coming out soon suggesting that Trump’s rage tweeting is associated with declines in his approval ratings. It’s possible that’s a correlation without a causation, but it’s at least pretty interesting.

harry: But your points get at something larger, Micah. The political impact this has will depend on how people view the issue.

micah: OK, let’s move to hypothesis No. 2.

Trump is dividing the country.

I’ve seen this idea in a lot of coverage — that Trump is widening divides in the U.S.

harry: Well, the SurveyUSA poll we already cited suggests that people think he is. In that survey, 70 percent think Trump is making the situation regarding the NFL worse. A national poll conducted about a week ago by The Washington Post and ABC News found roughly the same thing more generally:

clare.malone: We were already divided on this issue, and Trump is intentionally fanning the flames of a cultural/political issue. He’s certainly doing nothing to try to interpret or empathize with Kaepernick or anyone who thinks police violence against minorities is a big problem. In fact, he’s trying to paint these protests as mindless anti-Americanism, when in fact they’re trying to draw attention to a specific issue. It’s not an act of kneeling out of petulance — it’s to point out that the American system has an original sin.

natesilver: I mean … who’s going to deny that Trump is widening the divides? And also taking advantage of wide divides that were already there? A more interesting question is whether that trend will reverse itself at some point during (or shortly after) his tenure in office.

micah: Wait a sec.

perry: We already know America is divided along urban-rural/white-nonwhite/ Democrat-Republican lines. But Trump is introducing that divide into new issues. It’s just hard to see the Confederate monument debate playing out the way it is in the Virginia governor’s race, for example, if Hillary Clinton/Marco Rubio/Jeb Bush is president.

micah: Do we have any data showing divides getting wider?

I just think … this seems obviously true, but what’s the evidence for it?

clare.malone: I guess the counterargument is that now people are annoyed at Trump for being so insensitive, and they might become more sympathetic to the kneeling protest out of irritation with the president.

But I have no polling to cite on that.

September 25, 2017

Politics Podcast: Trump vs. The NFL

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS |

Embed

Embed Code

Over the weekend, President Trump repeatedly targeted the NFL, calling on owners to fire or suspend players for protesting during the national anthem and telling his supporters to boycott the league. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew assesses the motivations and repercussions for Trump, after owners and players alike responded negatively. FiveThirtyEight’s Kyle Wagner also joins the podcast to talk about the the ongoing NFL protests and the history of protests in sports. Plus, Clare Malone shares a rundown of potential wild card Senate races to look forward to in 2018.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 22, 2017

Emergency Politics Podcast: McCain Is A No On Graham-Cassidy

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS |

Embed

Embed Code

Sen. John McCain announced on Friday that he would vote no on the Graham-Cassidy bill, a renewed GOP effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act. FiveThirtyEight’s Politics podcast team weighs in on whether Republicans can still muster a repeal with only a week before their options narrow significantly.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

September 21, 2017

The Media Has A Probability Problem

This is the 11th and final article in a series that reviews news coverage of the 2016 general election, explores how Donald Trump won and why his chances were underrated by most of the American media.

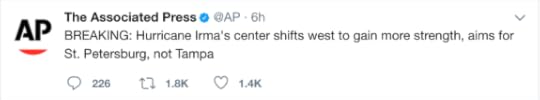

Two Saturday nights ago, just as Hurricane Irma had begun its turn toward Florida, the Associated Press sent out a tweet proclaiming that the storm was headed toward St. Petersburg and not its sister city Tampa, just 17 miles to the northeast across Tampa Bay.

Hurricane forecasts have improved greatly over the past few decades, becoming about three times more accurate at predicting landfall locations. But this was a ridiculous, even dangerous tweet: The forecast was nowhere near precise enough to distinguish Tampa from St. Pete. For most of Irma’s existence, the entire Florida peninsula had been included in the National Hurricane Center’s “cone of uncertainty,” which covers two-thirds of possible landfall locations. The slightest change in conditions could have had the storm hitting Florida’s East Coast, its West Coast, or going right up the state’s spine. Moreover, Irma measured hundreds of miles across, so even areas that weren’t directly hit by the eye of the storm could have suffered substantial damage. By Saturday night, the cone of uncertainty had narrowed, but trying to distinguish between St. Petersburg and Tampa was like trying to predict whether 31st Street or 32nd Street would suffer more damage if a nuclear bomb went off in Manhattan.

To its credit, the AP deleted the tweet the next morning. But the episode was emblematic of some of the media’s worst habits when covering hurricanes — and other events that involve interpreting probabilistic forecasts. Before a storm hits, the media demands impossible precision from forecasters, ignoring the uncertainties in the forecast and overhyping certain scenarios (e.g. the storm hitting Miami) at the expense of other, almost-as-likely ones (e.g. the storm hitting Marco Island). Afterward, it casts aspersions on the forecasts unless they happened to exactly match the scenario the media hyped up the most.

Indeed, there’s a fairly widespread perception that meteorologists performed poorly with Irma, having overestimated the threat to some places and underestimated it elsewhere. Even President Trump chimed in to say the storm hadn’t been predicted well, tweeting that the devastation from Irma had been “far greater, at least in certain locations, than anyone thought.” In fact, the Irma forecasts were pretty darn good: Meteorologists correctly anticipated days in advance that the storm would take a sharp right turn at some point while passing by Cuba. The places where Irma made landfall — in the Caribbean and then in Florida — were consistently within the cone of uncertainty. The forecasts weren’t perfect: Irma’s eye wound up passing closer to Tampa than to St. Petersburg after all, for example. But they were about as good as advertised. And they undoubtedly saved a lot of lives by giving people time to evacuate in places like the Florida Keys.

The media keeps misinterpreting data — and then blaming the data

You won’t be surprised to learn that I see a lot of similarities between hurricane forecasting and election forecasting — and between the media’s coverage of Irma and its coverage of the 2016 campaign. In recent elections, the media has often overestimated the precision of polling, cherry-picked data and portrayed elections as sure things when that conclusion very much wasn’t supported by polls or other empirical evidence.

As I’ve documented throughout this series, polls and other data did not support the exceptionally high degree of confidence that news organizations such as The New York Times regularly expressed about Hillary Clinton’s chances. (We’ve been using the Times as our case study throughout this series, both because they’re such an important journalistic institution and because their 2016 coverage had so many problems.) On the contrary, the more carefully one looked at the polling, the more reason there was to think that Clinton might not close the deal. In contrast to President Obama, who overperformed in the Electoral College relative to the popular vote in 2012, Clinton’s coalition (which relied heavily on urban, college-educated voters) was poorly configured for the Electoral College. In contrast to 2012, when hardly any voters were undecided between Obama and Mitt Romney, about 14 percent of voters went into the final week of the 2016 campaign undecided about their vote or saying they planned to vote for a third-party candidate. And in contrast to 2012, when polls were exceptionally stable, they were fairly volatile in 2016, with several swings back and forth between Clinton and Trump — including the final major swing of the campaign (after former FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress), which favored Trump.

By Election Day, Clinton simply wasn’t all that much of a favorite; she had about a 70 percent chance of winning according to FiveThirtyEight’s forecast, as compared to 30 percent for Trump. Even a 2- or 3-point polling error in Trump’s favor — about as much as polls had missed on average, historically — would likely be enough to tip the Electoral College to him. While many things about the 2016 election were surprising, the fact that Trump narrowly won1 when polls had him narrowly trailing was an utterly routine and unremarkable occurrence. The outcome was well within the “cone of uncertainty,” so to speak.

So if the polls called for caution rather than confidence, why was the media so sure that Clinton would win? I’ve tried to address that question throughout this series of essays — which we’re finally concluding, much to my editor’s delight.2

Probably the most important problem with 2016 coverage was confirmation bias — coupled with what you might call good old-fashioned liberal media bias. Journalists just didn’t believe that someone like Trump could become president, running a populist and at times also nationalist, racist and misogynistic campaign in a country that had twice elected Obama and whose demographics supposedly favored Democrats. So they cherry-picked their way through the data to support their belief, ignoring evidence — such as Clinton’s poor standing in the Midwest — that didn’t fit the narrative.

But the media’s relatively poor grasp of probability and statistics also played a part: It led them to misinterpret polls and polling-based forecasts that could have served as a reality check against their overconfidence in Clinton.

How a probabilistic election forecast works — and how it can be easy to misinterpret

The idea behind an election forecast like FiveThirtyEight’s is to take polls (“Clinton is ahead by 3 points”) and transform them into probabilities (“She has a 70 percent chance of winning”). I’ve been designing and publishing forecasts like these for 15 years3 in two areas (politics and sports) that receive widespread public attention. And I’ve found there are basically two ways that things can go wrong.

First, there are errors of analysis. As an example, if you had a model of last year’s election that concluded that Clinton had a 95 or 99 percent chance of winning, you committed an analytical error.4 Models that expressed that much confidence in her chances had a host of technical flaws, such as ignoring the correlations in outcomes between states.5

But while statistical modeling may not always hit the mark, people’s subjective estimates of how polls translate into probabilities are usually even worse. Given a complex set of polling data — say, the Democrat is ahead by 3 points in Pennsylvania and Michigan, tied in Florida and North Carolina, and down by 2 points in Ohio — it’s far from obvious how to figure out the candidate’s chances of winning the Electoral College. Ad hoc attempts to do so can lead to problematic coverage like this article that appeared in the The New York Times last Oct. 31, three days after Comey had sent his letter to Congress:

Mrs. Clinton’s lead over Mr. Trump appears to have contracted modestly, but not enough to threaten her advantage over all or to make the electoral math less forbidding for Mr. Trump, Republicans and Democrats said. […]

The loss of a few percentage points from Mrs. Clinton’s lead, and perhaps a state or two from the battleground column, would deny Democrats a possible landslide and likely give her a decisive but not overpowering victory, much like the one President Obama earned in 2012. […]

You’ll read lots of clips like this during an election campaign, full of claims about the “electoral math,” and they often don’t hold up to scrutiny. In this case, the article’s assertion that the loss of “a few percentage points” wouldn’t hurt Clinton’s chances of victory was wrong, and not just in hindsight; instead, the Comey letter made Clinton much more vulnerable, roughly doubling Trump’s probability of winning.

But even if you get the modeling right, there’s another whole set of problems to think about: errors of interpretation and communication. These can run in several different directions. Consumers can misunderstand the forecasts, since probabilities are famously open to misinterpretation. But people making the forecasts can also do a poor job of communicating the uncertainties involved. For example, although weather forecasters are generally quite good at describing uncertainty, the cone of uncertainty is potentially problematic because viewers might not realize it represents only two-thirds of possible landfall locations.

Intermediaries — other people describing a forecast on your behalf — can also be a problem. Over the years, we’ve had many fights with well-meaning TV producers about how to represent FiveThirtyEight’s probabilistic forecasts on air. (We don’t want a state where the Democrat has only a 51 percent chance to win to be colored in solid blue on their map, for instance.) And critics of statistical forecasts can make communication harder by passing along their own misunderstandings to their readers. After the election, for instance, The New York Times’ media columnist bashed the newspaper’s Upshot model (which had estimated Clinton’s chances at 85 percent) and others like it for projecting “a relatively easy victory for Hillary Clinton with all the certainty of a calculus solution.” That’s pretty much exactly the wrong way to describe such a forecast, since a probabilistic forecast is an expression of uncertainty. If a model gives a candidate a 15 percent chance, you’d expect that candidate to win about one election in every six or seven tries. You wouldn’t expect the fundamental theorem of calculus to be wrong … ever.

I don’t think we should be forgiving of innumeracy like this when it comes from prominent, experienced journalists. But when it comes to the general public, that’s a different story — and there are plenty of things for FiveThirtyEight and other forecasters to think about in terms of our communication strategies. There are many potential avenues for confusion. People associate numbers with precision, so using numbers to express uncertainty in the form of probabilities might not be intuitive. (Listing a decimal place in our forecast, as FiveThirtyEight historically has done — e.g. 28.6 percent chance rather than 29 percent or 30 — probably doesn’t help in this regard.) Also, both probabilities and polls are usually listed as percentages, so people can confuse one for the other — they might mistake a forecast showing Clinton with a 70 percent chance of winning as meaning she has a 70-30 polling lead over Trump, which would put her on her way to a historic, 40-point blowout.6

What can also get lost is that election forecasts — like hurricane forecasts — represent a continuous range of outcomes, none of which is likely to be exactly right. The following diagram is an illustration that we’ve used before to show uncertainty in the FiveThirtyEight forecast. It’s a simplification — showing a distribution for the national popular vote only and which candidate wins the Electoral College.7 Still, the diagram demonstrates several important concepts for interpreting polls and forecasts:

First, as I mentioned, no exact outcome is all that likely. If you rounded the popular vote to the nearest whole number, the most likely outcome was Clinton winning by 4 percentage points. Nonetheless, the chance that she’d win by exactly 4 points8 was only about 10 percent. “Calling” every state correctly in the Electoral College is even harder. FiveThirtyEight’s model did it in 2012 — in a lucky break9 that may have given people a false impression about how easy it is to forecast elections — but we estimated that the chances of having a perfect forecast again in 2016 were only about 2 percent. Thus, properly measuring the uncertainty is at least as important a part of the forecast as plotting the single most likely course. You’re almost always going to get something “wrong” — so the question is whether you can distinguish the relatively more likely upsets from the relatively less likely ones.

Second, the distribution of possible outcomes was fairly wide last year. The distribution is based on how accurate polls of U.S. presidential elections have been since 1972, accounting for the number of undecideds and the number of days until the election. The distribution was wider than usual because there were a lot of undecided voters — and more undecided voters mean more uncertainty. Even in a normal year, however, the polls aren’t quite as precise as most people assume.

Third, the forecast is continuous, rather than binary. When evaluating a poll or a polling-based forecast, you should look at the margin between the poll and the actual result and not just who won and lost. If a poll showed the Democrat winning by 1 point and the Republican won by 1 point instead, the poll did a better job than if the Democrat had won by 9 points (even though the poll would have “called” the outcome correctly in the latter case). By this measure, polls in this year’s French presidential election — which Emmanuel Macron was predicted to win by 22 points but actually won by 32 points — were much worse than polls of the 2016 U.S. election.

Finally, the actual outcome in last year’s election was right in the thick of the probability distribution, not out toward the tails. The popular vote was obviously pretty close to what the polls estimated it would be. It also wasn’t that much of a surprise that Trump won the Electoral College, given where the popular vote wound up. (Our forecast gave Trump a better than a 25 percent chance of winning the Electoral College conditional on losing the popular vote by 2 points10, an indication of his demographic advantages in the swing states.) One might dare even say that the result last year was relatively predictable, given the range of possible outcomes.

The press presumed that Clinton would win, but the public saw a close race

I’ve often heard it asserted that the widespread presumption of an inevitable Clinton victory was itself a problem for her campaign11 — Clinton has even made a version of his claim herself. So we have to ask: Could this misreading of the polls — and polling-based forecasts — actually have affected the election’s outcome?

It depends on whether you’re talking about how the media and other political elites read the polls — and how that influenced their behavior — or how the general public did. Regular voters, it turns out, were not especially confident about Clinton’s chances last year. For instance, in the final edition of the USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times tracking poll, which asked voters to guess the probability of Trump and Clinton winning the election, the average voter gave Clinton only a 53 percent chance of winning and gave Trump a 43 percent chance — so while respondents slightly favored Clinton, it wasn’t with much confidence at all.

The American National Election Studies also asked voters to predict the most likely winner of the race, as it’s been doing since 1952. It found that 61 percent of voters expected Clinton to win, as compared to 33 percent for Trump.12 This proportion is about the same as other years — such as 2004 — in which polls showed a fairly close race, although one candidate (in that case, George W. Bush) was usually ahead. While, unlike the LA Times poll, the ANES did not ask voters to estimate the probability of Clinton winning, it did ask voters a follow-up question about whether they expected the election to be close or thought one of the candidates would “win by quite a bit.” Only 20 percent of respondents predicted a Clinton landslide, and only 7 percent expected a Trump landslide. Instead, almost three-quarters of voters correctly predicted a close outcome.

Voters weren’t overly bullish on Clinton’s chances

Confidence in each party’s presidential candidate in the months before elections

WHICH PARTY WILL WIN THE PRESIDENCY?

DEM.

REP.

2016

61%

–

–

33%

✓

2012

✓

64

–

–

25

2008

✓

59

–

–

30

2004

29

–

–

62

✓

2000

47

–

–

44

✓

1996

✓

86

–

–

10

1992

✓

56

–

–

31

1988

23

–

–

63

✓

1984

12

–

–

81

✓

1980

46

–

–

38

✓

1976

✓

43

–

–

41

1972

7

–

–

83

✓

1968

22

–

–

57

✓

1964

✓

81

–

–

8

1960

✓

33

–

–

43

1956

19

–

–

68

✓

1952

35

–

–

43

✓

Source: American National Election Studies

So be wary if you hear people within the media bubble13 assert that “everyone” presumed Clinton was sure to win. Instead, that presumption reflected elite groupthink — and it came despite the polls as much as because of the polls. There was a bewilderingly large array of polling data during last year’s campaign, and it didn’t always tell an obvious story. During the final week of the campaign, Clinton was ahead in most polls of most swing states, but with quite a few exceptions14 — and many of Clinton’s leads were within the margin of error and had been fading during the final 10 days of the campaign. The public took in this information and saw Clinton as the favorite, but they didn’t expect a blowout and viewed the outcome as highly uncertain. Our model read it the same way. The media looked at the same ambiguous data and saw what they wanted in it, using it confirm their presumption that Trump couldn’t win.

News organizations learned the wrong lessons from 2012

During the 2012 election, FiveThirtyEight’s forecast consistently gave Obama better odds of winning re-election than the conventional wisdom did. Somehow in the midst of it, I became an avatar for projecting certainty in the face of doubt. But this role was always miscast — even quite opposite of what I hope readers take away from FiveThirtyEight’s work. In addition to making my own forecasts, I’ve spent a lot of my life studying probability and uncertainty. Cover these topics for long enough and you’ll come to a fairly clear conclusion: When it comes to making predictions, the world usually needs less certainty, not more.

A major takeaway from my book and from other people’s research on prediction is that most experts — including most journalists — make overconfident forecasts. (Weather forecasters are an important exception.) Events that experts claim to be nearly certain (say, a 95 percent probability) are often merely probable instead (the real probability is, say, 70 percent). And events they deem to be nearly impossible occur with some frequency. Another, related type of bias is that experts don’t change their minds quickly enough in the face of new information,15 sticking stubbornly to their previous beliefs even after the evidence has begin to mount against them.

Media coverage of major elections had long been an exception to this rule of expert overconfidence. For a variety of reasons — no doubt including the desire to inject drama into boring races — news coverage tended to overplay the underdog’s chances in presidential elections and to exaggerate swings in the polls. Even in 1984, when Ronald Reagan led Walter Mondale by 15 to 20 percentage points in the stretch run of the campaign, The New York Times somewhat credulously reported on Mondale’s enthusiastic crowds and talked up the possibility of a Dewey-defeats-Truman upset. The 2012 election — although it was a much closer race than 1984 — was another such example: Reporting focused too much on national polls and not enough on Obama’s Electoral College advantage, and thus portrayed the race as a “toss-up” when in reality Obama was a reasonably clear favorite. (FiveThirtyEight’s forecast gave Obama about a 90 percent chance of winning re-election on election morning.)