Foster Dickson's Blog, page 93

June 4, 2015

Friday, June 12: the Montgomery Art Guild features artist Clark Walker

On Friday, June 12, the Montgomery Art Guild will open an exhibit that honors artist Clark Walker at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. The exhibit will run through August 9. This is a well-deserved retrospective for Clark, whose first artistic recognitions came in the late 1950s when he was in high school.

I will be at the museum that evening not to only to honor my friend, but also to sign copies of my book about him, I Just Make People Up: Ramblings with Clark Walker (NewSouth Books, $45), during the opening reception, which will be from 5:30 until 7:30, with hors’ deuvres and a cash bar.

I will be at the museum that evening not to only to honor my friend, but also to sign copies of my book about him, I Just Make People Up: Ramblings with Clark Walker (NewSouth Books, $45), during the opening reception, which will be from 5:30 until 7:30, with hors’ deuvres and a cash bar.

Filed under: Alabama, Arts, Author Appearances, Local Issues, Published Books, Reading, Writing and Editing

June 2, 2015

June’s Southern Movie of the Month

The stark 1966 film, “The Black Klansman,” brought viewers, who were in the midst of the Civil Rights era, an exceptionally cheesy and dubiously Deep Southern story of a light-skinned “negro” in Los Angeles who infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan in his old hometown of Turnerville, Alabama after they kill his young daughter in the fire-bombing of a church. The opening credits explain that the screenplay is based on a song of the same name by Terry Harris. I came across “The Black Klansman” when I was searching Netflix for another film, and was immediately grabbed by its title. Though it’s probably too early to be considered “blaxploitation,” this mid-1960s low-budget film does have some of those characteristics.

As the film opens, we meet Jerry, a goatee-wearing LA hep cat, and his white girlfriend Andrea as they prep to go onstage, presumably in some sort of nightclub act. Jerry has just come back from snapping photos of local race riots for a white journalist who isn’t brave enough to get out in it, and Jerry’s skeptical, play-it-safe pal Lonnie plays the foil by making some swarthy comments about his lifestyle and his romance. The film ratchets up the tension when Jerry’s girlfriend wants to get married, and he starts to get angry, saying that neither their marriage nor their children would stand a chance in the real world. Then the call comes: his little daughter has been killed back in Alabama. Jerry freaks out and starts choking Andrea in a screaming rage about how he hates white people.

Back in the Turnerville of “The Black Klansman” racial tensions have elevated because a young black man has begun to push the envelope by seeking service in the white diner, even though he is warned not to stir up mess. The carload of Klansmen who firebomb the black church, killing Jerry’s daughter, are responding to this agitation, after also killing that lone young protestor.

Though Turnerville, Alabama is a real place, the Hollywood version of it in “The Black Klansman” doesn’t jive at all. The real Turnerville is north of Mobile near the Tensaw Delta, which is a low-lying, swampy place with lots of tall pines and Spanish moss. The film’s setting was a place of scrub brush, flat valleys, small mountains and sparse trees— basically, it was filmed in California, and only a person with no knowledge of Alabama would buy into that place being in south Alabama.

Jerry comes on the scene in Turnerville after having his hair straightened, his goatee shaved off, and his whole persona whitened. Once he gets there, He charges into the real estate offices of the Klan’s local head honcho – supposedly a big-time recruiter, but this guy can only muster one carload of bigots to firebomb a church – and demands to be taught how to start his own Klan chapter back in Los Angeles.

Now, let’s be frank here . . . in real life, back then, in small-town Alabama, charging into a big-time Klansman’s office— Jerry would have been dead by the time sun went down, no matter what color he was. But in the film, he walks out scot-free and even manages to catch the eye of the Klansman’s sultry blonde daughter at the front desk. Afterward, Jerry’s motel room gets the shakedown from a local dummy who can’t even hold his own in a one-on-one fight. Jerry handles him nicely, takes the fool’s gun from him, and sends him packing, only to be surprised immediately by the Klan leader who now believes in the young man’s sincerity. Jerry’s plan is working nicely.

Now, Jerry might have stood a chance to maintain his ruse but two unforeseen circumstances arise: the frustrated older brother of the slain wannabe-activist brings in some outside agitators from Harlem to organize the black community, and Lonnie and Andrea show up from LA to support their friend. While the skeptical, resistant response of the small-town Southern blacks to the two slick organizers is accurate enough, what happens with Lonnie and Andrea is way off base. When a black man and a white woman from out of town walk in the black nightclub, no one bats an eye! And then the bartender, who is also the town’s black motel owner, rents a room to the white woman as though it were a perfectly normal transaction! Keep in mind this is a town where a young black man is killed for ordering coffee at the white café. You just can’t expect a team of low-budget LA filmmakers in the mid-1960s to understand anything of Deep Southern nuance . . . .

Skipping ahead a little bit, Jerry makes friends among the KKK set and even gets inducted with a few other guys during a bizarre ceremony, but Lonnie and Andrea get roughed up by the two black organizers who need their help in killing whitey. In the final scene, all hell breaks loose: the black agitators face the lynch mob and Jerry has to convince his LA friends that he’s really on their side . . . before taking sweet revenge on the Klan!

The movie’s main poster claims that this hokey low-budget foolishness was “filmed in complete secrecy in the Deep South.” Not hardly. The place is off, and the characters are mostly off. Even the small-town black church used for the little girl’s funeral is whitewashed stucco with no greenery around it— basically, it’s a California church. Whoever dreamed up and made this farcical film knew nothing about the Deep South, its landscape, its people, or its social nuances. What is sad is that the poster’s other tag line was: “The most shattering film of our time!” Yeah, right.

In an even sadder note, under the alternate title “I Crossed the Color Line,” the film’s poster, which you can see on the imdb page, features a half-dressed Andrea transposed over top of she and Jerry in bed, and seems to insinuate with its imagery that the movie is some kind of taboo interracial-sex story. Let’s be clear, there was nothing sexy – and very little Deep Southern – about “The Black Klansman.”

Filed under: Alabama, Civil Rights, Film/Movies, Social Justice, The Deep South

May 31, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #69

The interest of an artist is the only limitation placed upon use of material, and this limitation is not restrictive. It but states a trait inherent in the work of the artist, the necessity of sincerity; the necessity that he shall not fake and compromise.

– from the chapter “The Common Substance of the Arts” in Art as Experience by John Dewey.

Filed under: Arts, Education, Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

May 29, 2015

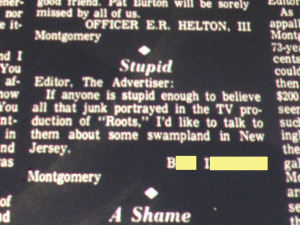

Apparently this guy didn’t like “Roots” . . .

I found this earlier today when I was scrolling through microfilm at the Alabama Department of Archives & History, working on my Whitehurst Case book. The letters-to-the-editor section of our local newspaper is one focus in searching archives, to get a sense of public opinion. This little letter caught my attention today – it has nothing to do with the Whitehurst Case – and I thought I’d share it. From the Montgomery Advertiser in the mid-1970s:

Filed under: Alabama, Film/Movies, Social Justice

May 26, 2015

The Community Legacy Project

I received the official word last week that I have been awarded a Community Legacy Project grant by the Center for Arts Education at the Boston Arts Academy. Below is the press release sent out by Montgomery Public Schools:

Booker T. Washington Instructor Awarded

Community Legacy Project Grant

National Artist Teacher Fellowship Awards Nine Grants for its Community Legacy Project in National Competition

MONTGOMERY, AL – Foster Dickson, a creative writing/English teacher at Booker T. Washington Magnet High School, will receive an $800 grant from the National Artist Teacher Fellowship’s Community Legacy Project.

The National Artist Teacher Fellowship (NATF) program supports the artistic revitalization of arts teachers, offering them the opportunity to immerse themselves in their own creative work, interact with other professional artists and stay current with new practices. For this year only, NATF awarded grants to nine previous Fellows, giving them the opportunity to share their work as engaged community-based artists through the Community Legacy Project. NATF is generously supported by the Surdna Foundation and is a program of the Center for Arts in Education at Boston Arts Academy.

The nine grant recipients represent seven states and seven unique arts schools from around the country including Booker T. Washington Magnet High School; Boston Arts Academy; City Arts and Technology High School; Fordham High School for the Arts; Greater Hartford Academy of the Arts; Media Arts Collaborative Charter School; and Paseo Academy of Fine and Performing Arts. The grantees are performing exemplary community work in the arts and engaging underserved groups with little access to arts instruction. These teachers excel in a broad spectrum of visual, performing, and literary arts.

Dickson will present a workshop at the 15th NATF Convening in October 2015 in Boston. In addition, the selected Fellows’ work will be featured on the NATF website, where it will serve as documentation of the program’s rich history. CLP grantees will become part of a lasting legacy for NATF, celebrating the program’s accomplishments over the past 15 years, and facilitating future collaborations between Fellows, administrators, schools and their communities.

Dickson encourages his students and local urban youth to engage in their community and educate themselves on the history and artistry of Alabama. He works with local community partners to impart on these youth from diverse racial and socio-economic backgrounds the cultural richness that exists in the state of Alabama.

In addition to being BTW’s creative writing teacher since 2003, Dickson is a working writer and editor. He was the operations manager/editor at NewSouth Books from 2001-2003. His poetry, interviews, book reviews, short fiction, and creative nonfiction works have been published in magazines and newspapers and on the web.

Dickson received his original grant from the Surdna Arts Teachers Fellowship in 2009.

For more information on the National Artist Teacher Fellowship program, please visit: http://www.natf-arts.org

Filed under: Alabama, Author Appearances, Education, Forthcoming, Local Issues, Teaching

May 24, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #68

. . . unlike typical classroom learning, real-world learning tends to be more cooperative and communal than individualistic, involves using tools rather than pure thought, is accomplished by addressing genuine problems rather than problems in isolation, and involves specific contextualized rather than abstract or generalized knowledge. College learning that more closely approximates the situation in which students will use their knowledge and continue to learn is less likely to be useless or inert.

– from the chapter “Identifying the Learning Outcomes of Service” in Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning? by Janet Eyler and Dwight E. Giles, Jr.

Filed under: Arts, Education, Teaching, Writing and Editing

May 19, 2015

AHF’s SUPER Teacher program: Slave Narratives

I got word first of last month that I was accepted to the Alabama Humanities Foundation’s SUPER program on “American Slave Narratives: Their Impact on Fiction and Film.” The SUPER Teacher Program, which is short for School and University Partners for Education Renewal, provides in-depth professional development for K-12 teachers during the summer by offering themed courses taught by university professors and scholars. I attended the program on Alabama’s Black Belt back in 2007, and out of that came the Treasuring Alabama’s Black Belt: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Place curriculum guide, for which I acted as general editor.

So this summer, it’s slave narratives. I and a handful of other teachers will be spending a week in Tuscaloosa learning more about how to teach these culturally sensitive documents as well as the more modern fictional depictions that have arisen from them.

I feel lucky that, back in 2002 and 2003, I assisted Randall Williams in compiling and editing the Alabama-centered slave narrative collection, Weren’t No Good Times. That experience more than ten years ago has grounded me in a healthy respect for nature of slave narratives. Reading through hundreds of narratives to cull the Alabama-based stories gave me a tour de force education in these difficult documents, though I’ve not studied them much in scholarly settings before.

For the next month, I will be reading . . . a lot! In the package full of books that came recently were two I had already read – Beloved by Toni Morrison and Jubilee by Margaret Walker – and four I had not, and one I’m only barely familiar with: Kindred by Octavia Butler. I’ve begun with The Confessions of Nat Turner by William Styron, and will likely move next to the collection, The Classic Slave Narratives, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. And of course, what rounds the assigned readings: The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest Gaines, which I remember reading back in school . . . twenty or twenty-five years ago. Might be wise to re-read that one! Going back over Beloved and Jubilee will probably be equally wise.

What prompted me to jump on this offering though is something I mentioned in one of my recent “A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week” posts; this week’s quote, from poet Andrew Hudgins, excerpts his remarks on Southern literature— really, on Southern culture . . . in which one feature is “a sense of the living presence of the past.” Slavery is an inherent and undeniable part of the South’s past, and as such is very much with us still, even one-hundred-fifty years after Emancipation. The ongoing legacy is here, in our society, in our economy, in our culture. If you ask me, no Southerner can know enough about the realities of slavery, and also about its mythology, the latter of which prompted me to sign up for all this work. I’m interested in what really happened, in what we may believe to have happened, and the gaps between the two, because we carry all of that – both truth and un-truth – forward with us.

Filed under: Alabama, Education, Literature, Reading, Social Justice, Teaching, The Deep South

May 10, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #66

“The shadow of caste falls over the school in Southerntown no less than over the courthouse and the church. Control of the schools and school opportunities is a crucial matter to American citizens and has long been viewed as such. Mass education is in the American mores and it is the door which has traditionally been open to those seeking to better their social status. It is this fact that has made the education of the young one of our major occupations and has led to the high value we place on schools and schooling. The symbol of the schoolhouse is the public guarantee that American society is actually offering the equality of opportunity which is the pivotal conception in our social order.”

– from the chapter, “Caste Patterning of Education,” in Caste and Class in a Southern Town by John Dollard. This passage comes from the 1949 third edition; the book was originally published in 1937.

Filed under: Reading, Social Justice, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

May 5, 2015

May’s Southern Movie of the Month

What do I say about 2006’s “Black Snake Moan”? I don’t know. When Hollywood gets hold of the Deep South, the results are always questionable. (I cite the comedy “Sweet Home Alabama” and the 2001 remake of the suspense-thriller “Straw Dogs” as the worst offenders.) The strange premise of the story – a sexual abuse victim being forcibly “saved” by a disaffected old bluesman – caused me to avoid it for a long time. But I watched it recently, even though I was positive that it was going to be awful and hokey and chock-full of stereotypes.

This film, which is set in rural Mississippi, opens with naked Christina Ricci and Justin Timberlake rollin’ in the hay right before Timberlake’s character Ronnie will head off to military duty, leaving his sex-starved girlfriend Rae to fight the urge to masturbate in the field next to their trash-strewn trailer. She moans and groans and writhes around, as the long-bed two-tone pickup carries him off down a dusty road.

So how does our main character satiate her immediate loneliness? By getting bent over the half-bath sink in a cheap motel room by the local black crack dealer. Needing to relieve the tension of her departed lover, our lascivious main character Rae then goes to a drug-addled, booze-soaked shindig, where she and others play naked football in a muddy field, and where she gets mounted again by some unnamed dude who gets right back up and starts playing ball again. If we hadn’t expected a blues-tinged story called “Black Snake Moan” to be about sex, the point gets made immediately and repeatedly.

We also get to meet Lazarus – played by Samuel L. Jackson – an aging former bluesman whose wife is leaving him for another man. Though we first meet him in a bitter and resentful scene of public humiliation, we quickly get to know him as a well-liked community member with highly respected butter beans. Astute music fans will gather from his character that this is the hill country of Mississippi; early on, Lazarus sits down with an acoustic six-string to play RL Burnside’s “Bird Without A Feather,” and later, a tune from Otha Turner makes a brief appearance.

The two unlikely participants meet when Lazarus finds Rae, half-naked and unconscious, in the middle of the rural road by his house. Rae has been beaten and bloodied by her boyfriend’s shit-heel buddy Gill— the film’s Iago. Lazarus decides to take in the delirious stray, clean her up and buy her medicine, feed her some good grub . . . and chain her to the radiator until she’s well enough to suit him. The movie’s plot continues from there, as the settled-down old black man tries to reform this wild young white woman, who he learns has been severely molested by her father.

Soon, when Ronnie returns from duty, discharged for severe anxiety, Gill is there to make him aware of Rae’s shenanigans. Disconsolate from the mixture of his shame and his unfaithful lover, Ronnie goes looking for Rae. He finds her in Lazarus’ house, and in the climactic scene, we see the elder man face down his gun-toting accuser who hasn’t got the guts to pull the trigger. As “Black Snake Moan” ends, Ronnie and Rae get married in an impromptu ceremony and drive off to attempt marital bliss, just the two of them . . . and their numerous neuroses.

“Black Snake Moan” actually does a better job of portraying the rural Deep South than most Hollywood movies that try. However, the flaws are very real. Justin Timberlake’s accent disappears almost immediately, and despite working out in his fields, Lazarus’ work clothes are always clean. I was also put off by the utter clichés in Rae’s costuming: shabby Daisy Dukes and a cut-off t-shirt that had a Confederate flag on it. (C’mon, guys, you couldn’t be more imaginative than that?) With highly tempered quasi-exuberance, the compliments I am willing to offer “Black Snake Moan” are: it wasn’t as bad as I thought it was going to be, and I’m not completely ashamed of having watched it.

Filed under: Film/Movies, Literature, Mississippi, The Deep South

May 3, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #65

“Meanwhile, the more established editors liked what they saw on the editorial pages of the [Charlotte] News and reached out to young [Harry] Ashmore. At the time, there were about a dozen liberal newspapers in the South, and their editors formed a tight-knit fraternity that was always on the lookout for kindred spirits. At his first meeting of the American Society of Newspaper Editors in spring of 1946, Ashmore got to know Virginius Dabney and established an immediate kinship that they quickly reinforced with correspondence that would continue for years. Another close relationship, with Mark Ethridge, also developed from an editors’ meeting. Skillful raconteurs, they charmed each other with stories from the South’s political wars. The old lions of progressive thought in journalism delighted in knowing that their lineage would remain strong with Ashmore.”

– from the chapter “Southern Editors in a Time of Ferment” in The Race Beat: The Press, The Civil Rights Struggle, and The Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff

Filed under: Civil Rights, Published Books, Reading, Social Justice, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing