Foster Dickson's Blog, page 95

March 22, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #59

“And the real values [the Agrarians] were asserting in 1930 were not those of ‘material well-being’ or of neo-Confederate nostalgia, but of thoughtful men who were very much concerned with the erosion of the quality of individual life by the forces of industrialization and the uncritical worship of material progress as an end in itself.”

– from Louis D. Rubin, Jr.’s preface to the 1977 third edition of I’ll Take My Stand by Twelve Southerners

Filed under: Bible Belt, Reading, Sun Belt, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

March 17, 2015

Jim

Every year, I take my creative writing students to Montgomery’s historic Oakwood Cemetery, where they each choose a person whose tombstone stands out to them for some reason, then we go to the Alabama Department of Archives & History for most of two weeks where they do the research to write a short narrative autobiography of the person. The assignment, which asks them to create a literary character with a distinctive voice out of a real person, walks the line between creative nonfiction and historical fiction, as the students sift through census records and microfilm, record books and news articles to piece together a life-long past. [1]

Each year, when we go – we’ve been doing this for seven or eight years – I’m drawn to one particular grave, near the entrance to the cemetery: an above-ground bricked-in grave with a metal plaque that reads: “Here lies JIM, slave of S. Schuessler, died June 14, 1854, aged 30 years. Remembered for his virtue.” What strikes me about Jim’s grave is its placement. The African-American section of Oakwood Cemetery is much further back and down a hill; Jim was placed amongst white company.

Each year, when we go – we’ve been doing this for seven or eight years – I’m drawn to one particular grave, near the entrance to the cemetery: an above-ground bricked-in grave with a metal plaque that reads: “Here lies JIM, slave of S. Schuessler, died June 14, 1854, aged 30 years. Remembered for his virtue.” What strikes me about Jim’s grave is its placement. The African-American section of Oakwood Cemetery is much further back and down a hill; Jim was placed amongst white company.

Nearby, across a small road and over about twenty yards, is the grave of a man named Stephen Schuessler , who I presume to be the S. Schuessler from the plaque. The German name is fairly unique among names in Montgomery, Alabama. Unfortunately, there isn’t much to find on either man.

Nearby, across a small road and over about twenty yards, is the grave of a man named Stephen Schuessler , who I presume to be the S. Schuessler from the plaque. The German name is fairly unique among names in Montgomery, Alabama. Unfortunately, there isn’t much to find on either man.

The 1860 census shows Stephen Schuessler in Montgomery, 42 years old, working as a butcher. His birthplace is listed as Germany. His wife, Mary, who was 33, was born in Alabama, and the couple has two children, a three-year-old son and a one-month-old daughter. (Jim had passed away by this point.)

Living next door to them in 1860 were a 23-year-old man named Adam Schuessler and a 21-year-old man also named Stephen Schuessler, whose professions were a butcher and a blacksmith, respectively; the two of them are listed as being from Boden, Germany. They are probably related, though it is unclear as to how.

Ten years earlier, in 1850, the census has them all living together, sans the two young children, who were of course not born yet. There’s the elder Stephen at age 32, and his wife Mary at 23, and Adam and the younger Stephen as boys. Another woman was there with them too: Catherine Schuessler, age 37— considering that he had a wife . . . maybe she was a sister of the elder of Stephen, and mother to the two boys. But no Jim. No slaves or servants listed at all.

The only other record I’ve found on this Stephen Schuessler is a marriage record shows that him and Mary Sagar in August 1845 in Autauga County, Alabama, which is adjacent to Montgomery County. One German marriage record, which I can’t access, involves a man by the same name, but it wouldn’t do any good to dig it up to find more about a slave who died young and was buried among white people in Alabama.

So who was Jim? I’m far more interested in him than in the German-born butcher who held him as property. I’ve seen slave holdings listed in census records before, but in this case, no. In 1850, the younger Stephen was only a child, certainly too young to own a slave, when it is much more likely that his grown namesake was the man described in the plaque. “Remembered for his virtue,” and buried in the white section of the cemetery. Jim must have been, despite his circumstances, one hell of a guy.

[1] In all fairness, the idea for the cemetery project came from an article that novelist Philip Gerard wrote in Writer’s Chronicle in 2006 called “The Art of Creative Research.”

Filed under: Alabama, Black Belt, Local Issues, The Deep South

March 15, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #58

“It is not a question of knowing whether this interests you but rather of whether you yourself could become more interesting under new conditions of cultural creation.”

— from Guy Debord’s “Toward a Situationist International” (1957); quoted from Participation, edited by Clare Bishop, in the Documents of Contemporary Art series.

Filed under: Education, Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

March 14, 2015

Two events this Wednesday, March 18

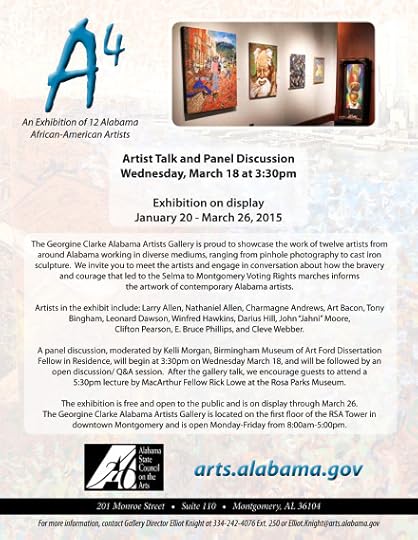

On Wednesday, March 18 at 3:30 PM, the Alabama State Council on the Arts is hosting an artist talk and panel discussion for “A4: An Exhibition of 12 Alabama African-American Artists.” Here’s the flyer for that event:

And later that evening, at 5:30, the Rosa Parks Museum is hosting Macarthur Fellow, Rick Lowe, who will discuss Project Row Houses. Part of the description from the project’s website reads:

Project Row Houses (PRH) is a community-based arts and culture non-profit organization in Houston’s northern Third Ward, one of the city’s oldest African American neighborhoods. It was founded in 1993 by artist and community activist Rick Lowe, along with James Bettison (1958-1997), Bert Long (1940-2013), Jesse Lott, Floyd Newsum, Bert Samples, and George Smith, all seeking to establish a positive, creative and transformative presence in this historic community.

Filed under: Alabama, Arts, Education, Local Issues, The Deep South

March 10, 2015

The (inaugural) Southern movie of the month

“. . . tick . . . tick . . . tick,” released in 1970, tells the unlikely story of a small Southern town whose long-time white sheriff, played by George Kennedy, has been voted out of the office by newly enfranchised blacks. He has been replaced by a cool-and-collected, muscle-bound black family man played by football great Jim Brown.

Of course, the white townspeople are not fond of their new black sheriff, but neither are the few more militant blacks, who want this new empowerment to mean a reversal of the power structures: black on top, whitey on bottom! By contrast to both groups, Jim Brown’s righteous character, Jimmy Price, is determined to have law and order prevail— he is caught in the middle. Yet, he needs the help of the now-prostrated former sheriff, John Little, who is constantly harried and taunted by people who seem to blame him for losing the job.

While taking on the well-known racial issues of the day, this film throws in a few of the supporting characters that we expect to be there: an omnipresent Ku Klux Klan looming near every precarious scene, a troublemaking bigot from a notoriously shiftless family, and a self-important local bigwig. It’s all there. We even get a mass-violence scene full of lawless mayhem near the end. Though we never get to know exactly where they are in the South, Little’s wife at one point suggests that they move away, either to Atlanta or Birmingham, implying that their small town lies somewhere between the two.

“. . . tick . . . tick . . . tick” reminded me a poor-man’s “In the Heat of the Night” from 1967. (The writer of the film’s entry on Wikipedia had the same idea, I was not surprised to see.) We’ve got the difficult juxtaposition of two lawmen – one white, one black – in a small Deep Southern town where the racial balance is teetering and about to crash. This film’s rich bigwig seemed much like that film’s Mr. Endicott, and both films have their pragmatic mayor who seems to insert himself when necessary to keep the action moving.

However, “. . . tick . . . tick . . . tick” does a few things differently. Sorry to spoil the end, but— having the Klan to partner with the black sheriff, working together to rebuke a mob from an adjacent county, was an interesting twist. Also, in a move that I did think was pretty cool, near the end of the movie, the old white mayor has a good heart-to-heart with his long-time black butler about how the latter man has been eavesdropping for years and reporting the ill-gotten secrets to the black community. In perhaps too convenient a resolution, the men close the scene smiling and drinking together.

Overall, “. . . tick . . . tick . . . tick” is a pretty good movie. Not great, but not bad. The cast is strong enough: George Kennedy had, in 1967, recently won an Academy Award for this character Dragline in Cool Hand Luke. Jim Brown had been in The Dirty Dozen that year too. And Ralph Nelson, who directed the Sidney Poiter film “Lilies of the Field,” also directed this one. But by 1970, I doubt if this movie added much to the discussion of Deep Southern integration. Just more good ‘ol stereotypes, with a dash of hope tossed in at the end.

Filed under: Alabama, Bible Belt, Civil Rights, Film/Movies, Georgia, Social Justice, The Deep South

March 8, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #57

“I have withstood the obsession with politics because I do not believe any system will make man less cruel or less greedy. He has to do this himself, individually.”

– from “[September 1945]” in The Diary of Anais Nin: Volume Four, 1944 – 1947, edited and with a preface by Gunther Stuhlmann

Filed under: Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

March 3, 2015

Some Other News from Around the Deep South, special edition

Welcome to a special edition of “Some Other News from Around the Deep South,” my usually quarterly look at news stories around the region that didn’t get much coverage. Normally, a new installment would be coming in April, but with so much going on, why wait?

Though I won’t spend as much time on it as Slate and The New York Times have— conservative Alabamians got yet another historic spanking from a federal judge back in February when the state’s constitutional ban on same-sex marriage was struck down. Alabama is now the 37th state to issue same-sex marriage licenses. Since the ruling, Alabama’s highly regrettable and always stolid Chief Justice Roy Moore has gone on a counter-offensive, using a variety legal and religious rationales and edicts, including one about how a state Supreme Court can overrule a federal district court, and another telling county probate judges not to issue the licenses. The federal judge overruled that last one, too.

And, in a distinctly Deep Southern twist, the Ku Klux Klan has joined in as back-up singers in this cacophonous dirge, putting its weight behind Moore’s position. Meanwhile, Alabama’s governor Robert Bentley is taking the high road, saying that our state will comply with the law, and Attorney General Luther Strange is riding out the storm in his own distinctly quiet way. The US Supreme Court is slated to rule on the issue of same-sex marriage in June. ‘Til then, we’ll wait for the next plot twist in this absurdist tragicomedy.

In the meantime, if you’re interested in reading further about the matters of LGBTQ rights and same-sex marriage in the South, here’s my further-reading list, from recent news stories:

“A Legal Toolkit for LGBTQ Southerners Is Great. But What About Etiquette?” on Slate’s “Outward” blog

“Mapped: Some States Always Need A Shove Past the Civil Rights Finish Line” on the Washington Post‘s Wonk Blog.

You know you’ve made it to the national spotlight when The Onion takes notice: “Gay Couple Always Dreamed of Getting Married Surrounded by Hostility”

Even the ultra-fickle People magazine is getting into the discussion: “What’s It Really Like to be Gay in Alabama?”

However, the South’s long-standing disdain for gays and lesbians is not the only kind of hateful, shameful behavior that got our region some attention in February. Last month, the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative released its long-term study on the history of lynching in the South.

The New York Times‘ reportage of the story, , offers a small sampling of the gory and disgusting details of these racialized instances of “man’s inhumanity to man,” as well as a map showing how densely occurring and widespread this crime has been in our region. The practice of lynching has long been one of those widely known secrets in the South and details have often been closely guarded locally. EJI’s study is the first step in an attempt to acknowledge the victims, and the crimes, with the intent of pushing many of the local communities to erect historic markers about the events.

Likewise, in mid-February, Salon.com ran a lynching-history piece by Bill Moyers with the ominous and difficult title: “When America behaved like ISIS: Jesse Washington and the Bible Belt’s dark history of public lynching.” Though the story of Jesse Washington is not a Deep Southern one – the lynching occurred in Waco, Texas – its details and its significance connect through the region, as EJI’s report shows. A bit of warning: the article contains graphic and disturbing imagery. There is no way for me to tell the story better than Bill Moyers does here— he writes, in the passage below one image:

Take a good look at Jesse Washington’s stiffened body tied to the tree. He had been sentenced to death for the murder of a white woman. No witnesses saw the crime; he allegedly confessed but the truth of the allegations would never be tested. The grand jury took just four minutes to return a guilty verdict, but there was no appeal, no review, no prison time. Instead, a courtroom mob dragged him outside, pinned him to the ground, and . . .

The surreal details that follow are shocking, mainly in the fact that they were commonplace. But that was life in the South in the heyday of lynching.

Living day-to-day life in a region perhaps most known for hate makes every scenario precarious. (Yes, I know that the South is also known for its food, its music and for its hospitality— but none of those can be separated from its historical realities, which are steeped in a hateful way of life.) Just knowing that, in the not-too-distant past, lynching was normal, public, even celebrated . . . I don’t know what to say about it.

Yet, as we see in the same-sex marriage cases, our dark and intolerant history is not over. The aftermath of the same-sex marriage ruling has brought resurgent defiance and protests. And make no mistake that the darkest parts of our past are long gone. The 1999 lynching of Billy Jack Gaither, a gay man in Sylacauga, Alabama, provides details no less gruesome than the ones from 1916 that Bill Moyers describes. I wish I knew when this “Southern way of life” will truly change.

Filed under: Alabama, Bible Belt, Black Belt, Civil Rights, Local Issues, Social Justice, The Deep South

March 1, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #56

“The relationship between sound and spelling is a nightmare. Our writing system is not phonetic to the point of being anti-phonetic. There are, for instance, at least seven ways of representing what for most people is same vowel sound— “ee”: free, these, leaf, field, seize, key, machine. What do we do?”

from “The Proper Way to Talk” in The Adventure of English: The Biography of a Language by Melvyn Bragg

Filed under: Education, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

February 24, 2015

My Five, In Response: A Writing Teacher’s Open Letter

When I saw a blog post titled “5 Things Students Want to tell Their Writing Teachers” last December, I had to read it. Appearing on Brilliant-Insane: Education on the Edge, the post by Angela Stockman breaks the bad news: writing teachers aren’t giving our students all that they want, or need . . . apparently.

I’ve been teaching for a while – almost twelve years – and yes, students often dislike, ignore or even resent some aspects of writing instruction. Unlike in math or science, writing instructors cannot proffer one clear-cut method leading to a clear-cut objectively correct answer, so students can tire of its will-o’-the-wisp nature. Yes, learning to write well can be frustrating.

But what makes writing both aggravating and worthwhile is: there is more than one right way to do it! Good writing instructors know that. And open-minded students who are willing to learn do, too.

Every school year, I start by talking my students through Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. We often see things in our lives in half-shadows, reflected by dim light, and because of that, misunderstandings and unwarranted anxieties can replace the rational thoughts that come from clear perceptions. Learning can often be unwanted, and even painful, like the shock of sunlight to a person who has been in a dark room for a while. Yet our eyes will adjust, and when we see things clearly, in full light, we can never be satisfied with stumbling around in the dark.

That said, here are five things that this writing teacher – me – would like to tell students:

1. Learning is more important than numerical grades. Down the line, no one will care what grade you made in my class; they will care whether you have the skills you were supposed to have gained. If a student makes 75 on a writing assignment, supposedly meaning he was three-quarters correct— he probably he knows just enough to be wrong while still thinking he’s right. Beyond that, parents or colleges may focus on the importance of letter grades, but students come to school to learn. An admirable transcript might get you into college, but learning to write will keep you there.

2. Everything worthwhile isn’t necessarily enjoyable. Many things in life that are worth having require hard work and struggle, which aren’t fun. For example, when we drive on paved streets, we have to remember that the road crews sweated and labored and maybe even got injured so we could have those nice smooth streets. Young people who want for everything to be fun and self-affirming are misleading themselves about how life works. And we teachers do them no favors when we deceive ourselves into thinking that all learning – the whole school day – can be fun. Grading dozens, or even hundreds, of papers isn’t fun either— but teachers do our work because student learning worth the effort.

3. Revision is absolutely necessary. Truly adept writers are thoughtful people, who want to revisit their own ideas and words over and over. Writers are not just crafty wordsmiths who can dash off a few paragraphs quickly. When a student relies on his own version of Kerouac’s “first thought, best thought” mantra, he only short-changes himself. Believing that first drafts are adequately thoughtful would be like believing that a first date amounts to the same thing as a year of marriage. I know that revision can be cumbersome and time-consuming‚ but neither laziness nor self-righteousness is a valid reason for avoiding the necessary work of getting the words right.

4. How do you know this method doesn’t work better for you, if you didn’t actually try it? Some students decide in advance whether or not they will learn from an activity, approaching the lesson with “This is stupid,” or “That’s not the way I do it.” If a student has no intention of giving an honest and open try to a writing lesson, then he or she will never learn, from me or from anyone else, with that attitude. We only learn when we are willing to. In short, if you’re close-minded and resistant, don’t blame your teacher for not reaching you.

5. I’ve heard the classic complaints before. The two most annoying defenses from students who won’t accept their writing’s lack of quality are: “My last English teacher said I was a good writer,” and “My family loves everything I write.” The first of the two ties back to Stockman’s #3: “Your constant praise feels a little condescending.” Some English teachers would rather praise a student and give an A than teach. That method is easier, and it avoids conflict— but that doesn’t make their insincere and lazy praise true. As for the latter defense, your family loves you, and what they’re praising is not literary quality, but their sense of your sweetness and sincerity. Unless you come from a family of editors, they’re expressing their affection, not affirming your greatness.

Angela Stockman is right in one sense: teachers need to listen to their students. I have a stockpile of tried-and-true assignments, and as I get a sense of my classes, I tailor my syllabus to the group’s needs. For example, I add more experiential learning (field trips) to classes when I see that the students have a strong grasp of fundamentals, and I reduce or eliminate experiential learning lessons when groups of students show themselves to be immature or untrustworthy. I require more in-class revisions, when I see students neglecting that aspect, and I give more one-on-one time to students who clearly want that. Knowing our students, and listening to them is integral to teaching writing— just as integral as students listening to their teachers.

Filed under: Education, Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

February 22, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #55

“We all know that something is eternal. And it ain’t houses and it ain’t names, and it ain’t earth, and it ain’t even the stars . . . everybody knows in their bones that something is eternal, and that something has to do with human beings. All the greatest people ever lived have been telling us that for five thousand years and yet you’d be surprised how people are always losing hold of it. There’s something way down deep that’s eternal about every human being.”

– spoken by the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town,” one of my very favorite plays of all time

Filed under: Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing