Foster Dickson's Blog, page 94

April 28, 2015

Some Other News from Around the Deep South #12

Welcome to “Some Other News from Around the Deep South,” my quarterly look at news stories from the region that may not have gotten so much attention.

We’ll start off an admittedly Mississippi-heavy installment with an always reliable source of prime comedy: state government. In early February, Jackson’s Clarion Ledger ran a quippy little story on things that a few state leaders have said recently. It’s not a terribly meaningful story, but my sentimental side couldn’t ignore it. Laughing at Deep Southern state legislatures just appeals to my better nature.

Anyway, on to actual discussion-worthy news: also in February, the Atlantic was reporting on “A School District That Was Never Desegregated” in Cleveland, Mississippi. This small town is still trying to figure the actual methods by which it will racially integrate its schools in response to a lawsuit “originally filed in 1965.” According to the article, the previously all-black schools are still basically all-black. This issue of school desegregation still lingers on this country, especially in the Deep South; the article tells us:

Cleveland is one of 179 school districts in the country involved in active desegregation cases. Mississippi has 44 of these cases—more than any other state.

If that statistic is correct, then that notoriously difficult Deep Southern state alone – one of fifty states – has about one-quarter of the nation’s ongoing “active desegregation cases.”

Reading further, the article says that the order to get moving on integration came in 1969, that magnet schools were created thirty-one years later in 1990, and that an IB curriculum was instituted at the black school in 2012— all to minimal effect. So, the Department of Justice is going to step in and give them a hand . . . Just what all Deep Southern politicians love and adore— oversight from the Feds.

Moving from Mississippi’s school system to its legal system, NPR reported in mid-February about a federal judge there who gave a stirring historically minded speech as he was sentencing three white defendants who had been convicted of killing a black man. In this fairly long speech, which evokes the history of lynching and racism, prominent perspectives on a racist past, and vivid details about the murder of the black man, Judge Carlton Reeves refuses to lighten the burden of Southern racism as a driving force of cruelty and inhumanity. As in some of my other commentaries in this series, rather than try to restate, I will simply direct the reader to the speech itself— there’s no way I could tell it better.

About a month later, in mid-March, the Daily Beast reported from Mississippi that “a 54-year-old African American man, Otis Byrd, was found dead hanging from a tree.” Due to the eerie circumstances that greatly resemble an old-style lynching, the ears of law enforcement perked up immediately. According to the brief story, a friend had dropped Byrd off at a Vicksburg casino and the next time anyone saw him he was dead and “hanging about a half mile from his last known residence.” Byrd had once been convicted of murder but had been out of prison for nearly ten years.

In a more extensive reporting on Byrd’s death, MSNBC’s coverage on March 21 explains in more detail that Otis Byrd had a robbed a small store in 1980 and had killed a white woman, the store’s owner. He served about two-and-a-half decades for that crime, but had mostly stayed out of trouble since being released. By late March, an investigation of his death, which involved the Department of Justice, was well underway.

By early April, the case was still unsolved. CBS News coverage from April 8 tells us that it was still unclear to law enforcement whether his death was a homicide or a suicide. However, his family had hired a lawyer who is quoted this way:

“The family is grieving. They do plan to take action. There is a long history of lynching in Mississippi. Byrd was found dead three weeks ago and the family still has limited information and wants answers,” Dennis Sweet III said.

Moving over to Louisiana, Mother Jones online ran a story in early March from the strange annals of pop culture trivia: “The Town From ‘True Blood’ Is Filled With Toxic Explosives the EPA Fears Will Blow Up: The government’s plan was to set them on fire.” That site of filming for the HBO vampire series “True Blood” – Doyline, Louisiana – is sitting right near a former army base where “a munitions recycling company” is now “storing 15 million pounds of toxic military explosives on-site.” The MoJo article provides a little history on the situation then goes on to say:

Now the race is against the clock. The bunkers are falling apart—pine trees are growing on the roofs of several of them—which means the increasingly unstable materials are now being exposed to moisture. And the EPA has warned that the explosives, which become more unstable over time, are increasingly at risk of an “uncontrolled catastrophic explosion.” So in October, the EPA announced it would do something it had never done before—approved a plan for a large-scale controlled burn of the hazardous military waste.

Locals are none too pleased about the discoveries, which came from a raid of the company’s operations on the former base facility. Yet, the folks in Doyline are kind of safe— for the moment: “The Army’s best guess for when the materials would become serious risks for self-combustion was August of 2015.”

Over in my necks of the woods, in Alabama, al.com reported in March that the “Alabama Police officer who slammed down Indian grandfather indicted on federal civil rights charges.” This incident got some national attention (for a minute) as another unfortunate case involving a white police officer and a person of color. In this case, an Indian-born grandfather had moved to Madison, Alabama to help his family with a new grandchild, and the article explains that he liked to take a walk in the morning . . . but:

Video from a dashboard camera shows [police officer Eric] Parker and another officer confront Patel. At one point, Parker slams the 57-year-old Patel to the ground. Madison police later called paramedics. Patel was left partly paralyzed. He was transferred from Madison Hospital to Huntsville Hospital where he underwent spinal surgery.

Eric Parker was then charged with having used excessive force— and Alabama made national news for racialized violence . . . again.

Finally, in news of far more local interest, the state of Alabama has lost one of its distinct and recognizable institutions, and is set to lose another. Recently, Birmingham’s Bottletree Cafe closed. Well-known as a venue for great music, Bottletree had hosted every kind of band you can imagine. (I still regret skipping a chance to see Black Joe Lewis there a while back.) This story from al.com does a great job of summing up their great history, and this one, “How Birmingham Became an Indie Rock Destination,” will provide some insights, too.

And so goes War Eagle Supper Club, well-known to Auburn alums and fans. This Opelika Auburn News article from July 2014 covered Supper Club’s 77th anniversary and also provides a little sense of place and its history. Unfortunately, this article from the same source in early April 2015 covers the fact that it’s closing at the end of the year . . . So sad.

That’s it for the twelfth installment of “Some of Other News from Around the Deep South.” Check back for lucky number thirteen in July.

Filed under: Alabama, Bible Belt, Civil Rights, Louisiana, Mississippi, Social Justice, The Deep South, The Environment

April 26, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #64

“Scatology and profanity in all its forms were officially forbidden, of course, but ‘cursing’ was a badge of toughness and looming manhood, and all of us used it with exuberant defiance around each other.”

– from the chapter “Big Boy” in Son of the Rough South: An Uncivil Memoir by Karl Fleming

Filed under: Civil Rights, Literature, Teaching, Writing and Editing

April 24, 2015

Deep Southern Gardening Mystery #9

These beautiful flowers come up behind my house every spring in a little patch that was probably was once a garden— the air-conditioning units were placed there some years ago, before we bought the house. Sometimes, in cleaning out that little space in the spring, I forget these and mow down the first sprouts with the weeds that are peeking through.

These purple flowers look like a type of lily. That’s my best guess. They hang pretty heavily on amid long blade-like foliage. Does anyone know what these are?

Filed under: Alabama, Black Belt, Gardening, The Environment

April 16, 2015

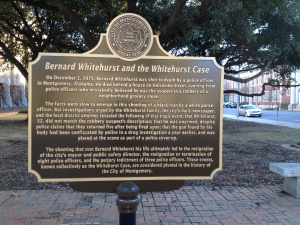

My next book: The Whitehurst Case

I am proud to relay that today I contracted my next book, which will be on the Whitehurst Case in post-Civil Rights Montgomery. After meeting the Whitehurst family back in 2013 and entertaining the possibility of a book on this subject, I did some preliminary research and foresaw a much larger book on the history of Montgomery in the 1970s and 1980s, which would interweave the many complicated events that peppered that time period. I dove head-long into that project through the latter half of 2013, all of 2014, and now into 2015. I’m been thankful for the cooperation I’ve gotten from quite a few long-time Montgomerians who have talked to me about Montgomery’s post-Civil Rights history.

I am proud to relay that today I contracted my next book, which will be on the Whitehurst Case in post-Civil Rights Montgomery. After meeting the Whitehurst family back in 2013 and entertaining the possibility of a book on this subject, I did some preliminary research and foresaw a much larger book on the history of Montgomery in the 1970s and 1980s, which would interweave the many complicated events that peppered that time period. I dove head-long into that project through the latter half of 2013, all of 2014, and now into 2015. I’m been thankful for the cooperation I’ve gotten from quite a few long-time Montgomerians who have talked to me about Montgomery’s post-Civil Rights history.

However, after many hours of research, over 50,000 words of text, and lots of pacing around my office, a discussion with NewSouth Books editor-in-chief Randall Williams convinced me that what I actually had was two books: one on the Whitehurst Case that was nearly finished, and one on post-Civil Rights Montgomery that was well underway. So, Randall and I came to terms, and the book on the Whitehurst Case has been contracted! (The Montgomery book will go on hold for now, and I will continue it when this first project is complete.)

Writing a book is a strange endeavor, which can twist and turn through a variety of forms and structures. This project, after deviating in my mind into wider terrain, has brought me back to the original idea that idea that was proposed over a lunchtime meeting with a family I’d then never met before. The Whitehurst Case is a complicated aspect of Southern history, which changed many lives in Alabama’s capitol city.

As the saying goes, it ain’t over ’til it over . . . I’ve got plenty of work to do – some interviews, some more research, more writing, and lots of polishing – over the next few months to ensure that the book’s final manuscript is clean and clear, accurate and well-documented. As more news becomes available, I’ll share it here.

Filed under: Alabama, Civil Rights, Forthcoming, Local Issues, Social Justice, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

April 12, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #62

“All that education can do in any case is to teach us to make good use of what we are; if we are nothing to begin with, no amount of education can do us any good.”

– from “Education, Past and Present” by John Gould Fletcher, in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, 1977 edition

Filed under: Education, Literature, Reading, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

April 7, 2015

April’s Southern movie of the month

The 1949 movie adaptation of William Faulkner’s “Intruder in the Dust” offers a different kind of race-relations narrative. In the story, we meet a white teenage boy named Chick Mallison who has been trying to repay the kindness of a black man – a landowner, which is a rarity in his day – who took care of Chick when he fell in a cold creek. The man, Lucas Beauchamp, is proud and dignified and will not hear of his hospitality being reimbursed, not even through gifts. However, when Beauchamp is arrested for the murder of a white man, he needs the boy’s help.

Predating the Academy Award-winning adaption of “To Kill A Mockingbird” by thirteen years, this story has both conventional and unconventional elements. By this stage in film history, we’ve seen the young white Southerner, baffled by a racist social order that makes no sense, carry us through a regional bildungsroman, and we’ve also seen the white lawyer who is willing to defy lynch-mob culture to defend an innocent (black) man. However, this lawyer is no Atticus Finch: John Gavin Stevens, Chick’s uncle, originally takes a much more foreboding stance on Lucas’ guilt. At first all he wants to know is: why did you shoot him? But Lucas confides in Chick, and as the mob outside is ready to overtake the supposed villain, the teenager has to solve the mystery of who really shot Vincent Gowrie.

William Faulkner regularly used the precarious nature of race in his plot twists: the weird black man in “Barn Burning” who warns the victims of Abner Snopes’ forthcoming actions, the stoic butler in “A Rose for Emily” who aids through his servitude in concealing a corpse upstairs, or the ever-faithful Clytie in Absalom, Absalom! who stands by her father until the last. Well, Lucas Beauchamp is the opposite of those characters— he is no servant, no aider, nor abetter. He stands on his own, even apart from the black community; Chick even remarks that it’s like the other blacks don’t even see him. In that, Chick is Lucas’ only hope.

In the film, we get some of the conventions of Southern storytelling: the despicable white family disdained by blacks and whites alike, the black man wrongly accused, the white youngster who values righteousness over custom, the lynch mob ready for blood. However, the story has no trite conclusions. Having an elderly lady stand off the mob while knitting in a rocking chair . . . we don’t see that too often. And unlike poor Tom Robinson of “To Kill A Mockingbird,” Lucas Beauchamp gets away with his life.

“Intruder in the Dust” could have been a better movie if the acting wasn’t so plastic. As I watched it, I had no clue how it was going to turn out, and tried to look past the forced dialogue and melodramatic scene-setting. Having read several of William Faulkner’s novels, I know that you can’t depend on him for neat and tidy resolutions that warm the heart and soul. But this time, it turns out OK . . . for everyone except old Nub Gowrie, who escorts one of his sons to jail for killing the other, while a proud black man saunters off down the crowded sidewalk.

Filed under: Black Belt, Civil Rights, Film/Movies, Literature, Mississippi, Social Justice, The Deep South

April 5, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #61

“Yet, elsewhere, all over town, there were suggestions that something new was coming to the surface here, something never quite articulated with any degree of force or with the courage of numbers in many Deep-Southern towns, some painful summoning with deepest wellsprings. There were whites in town who fully intended to keep their children in the public schools, and who not only would say so openly, but who after a time would even go further and defend the very notion itself of integrated education as a positive encouragement to their children’s learning. At first this spirit was imperceptible, but gradually, under the influence of some of Yazoo’s white leaders and with the emergence of others of like mind, it became a movement with noticeable strength behind it.”

– from “Holding Our Breath: October 1969 – January 1970″ in Yazoo: Integration in a Deep-Southern Town by Willie Morris, published in Reporting Civil Rights, Volume Two

Filed under: Civil Rights, Education, Mississippi, Reading, Teaching, The Deep South, Writing and Editing

March 31, 2015

As OPPA takes shape

*continued from an earlier post: “In the beginning, there was . . . gravel and sand”

Unlike many educators who start a school garden, I’m not a horticulturalist or science teacher— my only professional experience in this field is a summer of landscaping work right after high school, which consisted mainly of planting trees and lots of pansies, laying sod and shoveling fill dirt, and digging trenches and laying PVC for irrigation systems. No, my background in gardening – now fashionably dubbed “urban agriculture” – is purely DIY.

These localized practices were commonplace back in 1970s and 1980s Alabama. When I was growing up, my family had a garden plot in the backyard, and my dad, my brother and I were the yard crew for most of the elderly neighbors for a block in every direction. We also had a greenhouse off the back porch, where we could get our plants out of the cold and where my dad grew cacti and succulents as a hobby. From that experience, I learned when and how to plant and tend tomatoes, squash, peppers and cucumbers; I learned that mulched leaves and grass clippings raked into beds constituted fertilizer; and I learned to prune azaleas right after they bloom and that roses need acidic soil. I didn’t take classes to learn those things. My dad taught my older brother and me about them, as well as this very important lesson: anything you can do for yourself is something you don’t have to ask other people for.

That’s what I want the students to learn from this school garden— that and how to do things right. The intangible nature of good schoolwork = good grades isn’t enough to show young people how effort pays off. Sometimes, it has to be more than a symbolic letter on nine-weeks report card. In the Book of Ecclesiastes, chapter 10, verse 18 reads “Because of laziness, the rafters sag; when hands are slack, the house leaks.” If we plant the right things at the right time and tend them in the right way, we have a greater likelihood of our work paying off.

However, I also know that we’re going to plant some seeds that don’t grow, and that we will have some fledgling sprouts to wither, and that we will yield some seemingly healthy plants that bear no fruit. The purpose of a garden at a school is to figure out why we succeed sometimes and fail others, then carry that knowledge forward. If we succeed all the time, with every plant, the students will walk away thinking that’s how it goes— it’s just not.

With each construction day, we’ve made a little progress, and the students keep coming back the next day to make a little more. Gardening – or horticulture, or urban agriculture, call it what you want – isn’t a one-and-done activity. You have to keep showing back up, from seed to sprout to yield. That’s another good life lesson to learn from gardening.

Everybody keeps asking me, what are you going to grow? I answer simply, I don’t know. Whatever the students want to plant. One boy has been expressing a desire to grow sorrel since our first meeting. Others have stated a preference for more traditional Southern staples: tomatoes or collards. Whatever ends up being in our raised beds, we’ll consult the reference books to avoid doing something stupid, like planting tomatoes in February, and take it from there.

Filed under: Alabama, Education, Gardening, Local Issues, Teaching, The Deep South, The Environment

March 29, 2015

A writer-editor-teacher’s quote of the week #60

“I watch the political process pretty much as I watch baseball. I have a favorite team, but I know that ultimately it makes no difference who wins. I gave up on politics offering any hope for the world’s problems a long time ago. It’s an illusion, a mirage. Sometimes good comedy.”

– from chapter IV in Soul Among Lions: Musings of a Bootleg Preacher by Will D. Campbell

Filed under: Civil Rights, Literature, Reading, Teaching, Writing and Editing

March 24, 2015

In the beginning, there was . . . gravel and sand

Back during this rainy winter, I started talk of what it would take to have a school garden where I teach. For some time, I had had my eye on a plot of sunny ground near the back of an unused grassy lot; over the years, I had been keeping my eye on how the eastern sun from the morning rose over the campus, keeping this parcel bright all day, unimpeded by the nearby leland cypress to the south of the lot, only winnowing into shade late in the day when the scrub brush on the western fence stopped it. This little plot, which measure about 80′ x 80′ gets well over eight hours of sun a day, even in the winter. This was the spot.

So I pitched the idea to our new assistant principal, who was a science teacher, and he told me that our Environmental Science teacher had already been thinking about it— so go talk to her, partner up, and see what can happen. Turns out that a pair of students, two seniors who have been volunteering at Montgomery’s EAT South Downtown Farm, had also been talking to the local Rotary Club who were enthusiastic about helping, too. We all talked and agreed on a course of action: I would oversee establishment, construction, and maintenance; the two boys and some other student volunteers would form an extracurricular to help out; and the Environmental Science teacher could use it at will. Pretty good deal, since I don’t really want to write school-garden lesson plans, and she doesn’t really want to pull weeds.

The two seniors were most interested in the possibilities of reforming the campus along models of sustainability. Wanting to use what they had learned at EAT South, they originally wanted to figure out how the lunchroom waste could become compost. Having composted for years, I advised them to price-compare biodegradable trays that could replace the current styrofoam ones, and ask the lunchroom to switch. They were thinking about composting the waste every day, but I reminded them: if the lunchroom were to use our trays 1-3 days a month, just for lunch, our worms and roly-polies would have over 1000 trays a month to munch on! Unfortunately, the cost of the biodegradable trays was over three times the cost of styrofoam, so we were back to the drawing board. What if we offered to buy them, I asked the boys. Would she use the biodegradable trays if we provided them at no cost to the lunchroom? Keeping it positive, I told them: In the meantime, let’s just build our compost bins, take it one step at a time, and figure it out . . .

Next step: raising money. I worked with our school’s booster organization to procure construction funds for wood, soil and other necessaries, and our Environmental Science teacher applied for a local social-action grant program to get enough supplies and tools for her classes, as well as seeds and sprouts. We were in business! In our respective grant proposals, we both promised to use local suppliers for our purchases, so I worked with Bear Lumber for the wood and hardware, Harwell’s Green Thumb Nursery for supplies and tools, and Froggy Bottom Materials for soil and pea gravel. And through the generosity of our local Rotary Club, we would have a hand with ongoing needs like seeds and fertilizer.

Before we did anything in that plot, the soil needed testing. Our campus sits right next to the interstate, which was built in the early 1960s, and I’m convinced that the soil is soaked in lead from decades of leaded-gas fumes settling on that ground. On a cold February morning, we got out there before school and dug up our numerous little bits to mix together and send to Auburn University’s soil lab. We got a good report a few days later; it mainly told us about our mineral levels, along with fertilizer recommendations, but not contaminants. Better safe than sorry, I still insisted on raised beds, separating from that soil from our bed with weed barrier. We’d just have to engineer the beds for good drainage so we didn’t have dirt soup after the first good rain.

The students and I tossed around a few names – some traditional like “Garden Club” and others not-so-much like “The Phytomaniacs” – but one student’s idea took root: OPPA, which stands for Organizing, Producing, Providing, Agriculture.

Finally, after about two months of talking and planning, we started building on a rare sunny morning in mid-March. It has been a little frustrating having to wait and wait on the rain to pass, but the enthusiasm for getting started just grew each week. When the time came, students measured out and edged our beds, laid the weed barrier and staked it all down. We also had time to throw out hay in the spaces between the beds.

Because we couldn’t seem to get two consecutive days of dry weather, we still have to paint boiled linseed oil onto our untreated 2x12s, then bolt together the frames for our six 8′ x 4′ beds. We also still have to build our compost bin from old pallets, a trick I learned from the Growing a Greener World TV show. One of our teachers donated a rain barrel and bamboo for bean poles, too. With everything measured and prepped, and wheat straw down in our six-foot-wide walkways, all we need to do now is build the frames and shovel 200 cubic feet of topsoil into them!

OPPA’s new school garden is nearly up and running. I’d like to think that we’ll be ready to plant something before the end of the school year. Our seniors deserve to see little green sprouts in that dirt before they graduate. As for the lunchroom/composting project, that’s a long-term goal, and we’ll figure it out, too.

Filed under: Alabama, Education, Food, Gardening, Local Issues, Teaching, The Deep South, The Environment