Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 388

July 18, 2015

Can Design Help the USPS Make Stamps Popular Again?

In 1967, the United States Postal Service issued a new five-cent postage stamp to celebrate Henry David Thoreau’s 150th birthday. The stamp proved exceedingly popular, but not for the reasons the USPS might have guessed: The scraggly-bearded portrait of Thoreau by Leonard Baskin became a generational emblem among members of the counterculture, who identified with Thoreau as a tax resistor, abolitionist, and naturalist. The stamp’s success, meanwhile, proved that nontraditional stamp designs could help the Postal Service connect with nontraditional audiences, especially among the nation’s youth.

Related Story

Sweden's New Pop Stamps Reinforce Its Cultural Dominance

After 1971, when the USPS became an independent agency of the federal government, stamps became a vital revenue source. They were also the public face of the agency, and to broaden their appeal the USPS and the Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAS) began to work on stamps that would attract not just philatelists but everyday shoppers. In a new attempt to engage a population that prefers email to snail mail, the USPS is hoping to continue this trend by selling stamps that reflect the sender’s personal allegiances and resonate with their sensibilities.

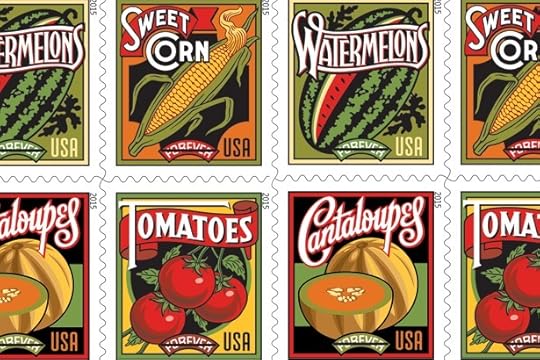

Earlier this month, the agency issued a new booklet of produce-themed stamps titled “Summer Harvest.” Designed and illustrated by the veteran illustrative letterer and typographer Michael Doret, who drew upon old fruit-and-vegetable-box labels for inspiration, the stamps seem to reflect the country’s renewed interest in organic and locally sourced food.

Antonio Alcalá, the art director at CSAS, said the group had two main audiences in mind when designing the new Forever stamps: foodies, and nostalgics. The stamps’ decorative lettering and stylized images of watermelon, cantaloupe, sweet corn, and tomatoes seem aimed at the stereotypical modern yuppie, who listens to records on vinyl, visits the local farmer’s market, shops for antiques, and might even occasionally forgo the ease of Gmail or Facebook in favor of writing and mailing a handwritten letter.

One of the challenges with producing stamps that capture a moment is that producing them is rarely a speedy process. The personnel on the committees change periodically, and the comments that come back from are sometimes arcane. In the case of the “Summer Harvest” stamps, it took almost 12 years for them to get from the drawing board to the post office. “I went through literally dozens of changes on this recent set before we settled on the approved designs,” says Doret. During the first round in 2002, he recalls there was a lot of back and forth suggesting various fruits or vegetables, then questioning what was the definition of “fruit,” then questioning whether these were specifically “American.” Even after his designs were accepted it still took about three years to get from refining the subject, artwork, and lettering to printing and issuance.

The stamps’ decorative lettering and stylized images seem aimed at the stereotypical modern yuppie.This isn’t the first time the USPS has tried something new. In 1987, it commissioned the caricaturist Al Hirschfeld to design a collection of five stamps, called “Comedians by Hirschfeld,” that were eventually released in 1991. Rather than the neutral portraiture typically used on commemorative stamps, his artwork introduced wit and humor to a serious and typically staid form. Hirschfeld became the first artist in American history to have his signature on a stamp booklet—not even Norman Rockwell had his name on the 1960 Boy Scouts stamp or the 1972 Tom Sawyer stamp he designed. The goofy personalities of the eight caricatured comedians (including Laurel & Hardy, Abbot & Costello, and Fanny Brice) elicited “chuckles from the letter-writing public,” according to a 1991 article in The New York Times. By leaving its stuffy, disconnected traditions behind, the USPS had successfully tapped into the irreverent heart of pop culture.

Other recent Forever stamps have featured images of Elvis Presley, Maya Angelou, Batman, vintage roses, the Battle of 1812, and ferns. Last year, the “Farmers Market” series even celebrated American produce in the same way the “Summer Harvest” stamps do, although with a more traditional design. While the quality and variety of stamp designs has increased, 7.3 billion fewer pieces of mail are sent annually in the U.S. since “Comedians by Hirschfeld” revitalized the USPS’s public image. The agency loses billions of dollars every year, and it’s unlikely that a vintage-inspired set of stamps featuring crops can do much to change that, however visually striking they might be.

But the USPS’s attempts to tap into the zeitgeist deserve credit, and the artists, designers, and art directors behind U.S. postage stamps take extraordinary pride in creating them. “It's difficult to describe the thrill,” says Doret, “of finding out that something into which one had invested so much time and love has now suddenly come back to life.”

The Cash-Strapped Agency at the Heart of the Iran Deal

In his public-relations blitz to defend the Iran nuclear deal, Barack Obama has repeatedly insisted that the agreement is not based on trust between Iran and the United States. “It’s not enough for us to trust when you say that you are only creating a peaceful nuclear program. You have to prove it to us,” he told Thomas Friedman of The New York Times. “And so this whole system that we built is not based on trust; it’s based on a verifiable mechanism, whereby every pathway that they have is shut off.”

The “verifiable mechanism” to which the U.S. president is referring consists of inspections of Iranian nuclear facilities by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). If the IAEA confirms that Iran is abiding by the strictures of the Joint Plan of Action between the United States, China, Russia, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Iran, then sanctions against Iran will be eased, potentially ushering in a new geopolitical era in the Middle East. If the IAEA detects Iranian cheating, those sanctions could be resurrected, endangering the elaborate framework to limit Iran’s nuclear program that negotiators constructed over the course of years.

This places a relatively small UN agency based in Vienna at the heart of one of the most important diplomatic breakthroughs in a generation. Is the IAEA up to the task?

Related Story

The Single Most Important Question to Ask About the Iran Deal

The IAEA is often referred to in shorthand as the “UN nuclear watchdog,” but its profile is not exactly commensurate with the financial resources at its disposal. Like many UN agencies, the IAEA funds its operations through a combination of assessed and voluntary contributions from member states. Member states are assessed dues based on a scale pegged to each country’s gross national income. This funds what is known as the “regular budget,” which pays for things like weapons inspectors, safeguards, and administrative costs. The United States is the largest contributor to the IAEA, funding about 25 percent of the regular budget. Japan comes in second, at about 10 percent. The poorest member states generally pay less than 1 percent each. (On top of the regular budget is a $90-million Technical Cooperation Fund that is supported through voluntary contributions and mostly pays for development activities, including using nuclear technology to improve agricultural outcomes and supporting radiation therapy and other medical programs that rely on nuclear physics in the developing world.)

Last year, the IAEA’s regular budget was just over $350 million. That’s less than the budget of the San Diego police department. Iran is roughly 1,700 times larger than San Diego by territory—and about twice the size of Texas. Of course, the IAEA’s budget funds not just inspections in Iran, but activities around the world.

The nuclear-inspection regime in Iran is going to be expensive, among numerous other logistical, technical, and political challenges. In a press conference on Tuesday, following the signing of the final accord, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano estimated that the Iran portfolio has cost his agency $1 million per month since November 2013, when Iran initially allowed limited inspection of certain sites as a condition to launch diplomatic talks. In the same press conference, Amano said it would take some time to budget the costs related to maintaining a pool of some 150 inspectors to deploy to Iran and monitor Iranian nuclear activities from afar.

The problem with all this is that IAEA member states have pressured the agency to rein in spending in recent years. A policy of “zero-real growth” imposed by the IAEA’s 35-member state Board of Governors has been in place for several budget cycles. In its 2015 budget report, the agency described a host of activities that it has undertaken to cut expenditures, even as the responsibilities placed on it by countries and international organizations have increased. These included, among other things, introducing a “paper smart” policy and optimizing “the use of technical and office supplies.”

In 2015, the IAEA reported that it had cut costs by introducing a “paper smart” policy and optimizing “the use of technical and office supplies.”No one should begrudge an office for being more judicious about using the copy machine. But the fact that the IAEA is touting cutting down on office supplies as a way to reduce spending suggests that the agency is operating under intense budgetary pressures.

In a speech last year, Amano pressed his case for more resources to carry out the IAEA’s activities around the world. “The number of nuclear facilities coming under IAEA safeguards continues to grow steadily—by 12 percent in the past five years alone,” he said. “So does the amount of nuclear material to be safeguarded. It has risen by around 14 percent in that period. With 72 nuclear-power plants under construction, and many additional countries considering the introduction of nuclear power in the coming years, that trend looks very likely to continue.”

Still, despite these new duties, Amano admitted that he did’nt expect much relief. “Funding for the agency has not kept pace with growing demand for our services and is unlikely to do so in the coming years,” he said.

These funding challenges are not unique to the IAEA. They represent a UN-wide problem. Member states keep asking international bureaucrats to do more with less. While this may make sense from a fiduciary standpoint, it has potentially harmful real-world implications. Like the IAEA, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been under extreme pressure for several years to cut programs and spending. When the Ebola outbreak struck West Africa last year, the World Health Organization was tasked with leading a robust response. But because of budget cuts—amounting to $600 million since 2010—a hobbled WHO lacked the personnel and tools to meet those expectations.

UN Peacekeeping faces similar burdens. Today there are more than 100,000 blue helmets deployed to 16 missions worldwide—more than at anytime in UN history. The budget for UN Peacekeeping is about $7 billion. That’s a lot of money. But for comparison’s sake, it’s less than one-tenth of what the United States will spend in Afghanistan and in “overseas contingency operations” this year. UN peacekeepers in tough places like South Sudan or Mali routinely lack basic equipment, like helicopters, that would maximize their reach and effectiveness.

Given the high-profile nature of the Iran deal, the IAEA’s member states will likely be more willing than not to fund the extra expenditures required to implement the agreement. But at some point, this political will may fade. Unless countries allow the budgets of international organizations to expand with the increased responsibilities placed on them by those very same member states, these agencies may not be able to fulfill their promise. For the IAEA, that may mean a decreased ability to detect nuclear proliferation—in Iran and beyond.

Is Donald Trump's Campaign 'News' or 'Entertainment'?

Here are some facts.

Donald Trump has alleged that many Mexican immigrants are rapists.

Donald Trump has pledged that he “will build a great, great wall on our southern border,” and that he “will have Mexico pay for that wall.”

Donald Trump has referred to President Obama, sarcastically, as “our great African American president.”

Donald Trump has repeatedly dismissed high-profile women for being “unattractive.”

Donald Trump has been rejected as a business partner by, among others, NBC Universal, Univision, and Macy’s.

Here is another fact: The two most-recent national polls show Donald Trump leading the field for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination.

And here is one more: On Friday, The Huffington Post announced that it will cease to cover Trump in the Politics section of its website. Instead, its Trump coverage will be filed under Entertainment. In a post headlined “A Note About Our Coverage Of Donald Trump’s ‘Campaign,’” the site’s Washington bureau chief and its editorial director explain that “our reason is simple: Trump’s campaign is a sideshow.” And so, they have concluded, “We won't take the bait. If you are interested in what The Donald has to say, you’ll find it next to our stories on the Kardashians and The Bachelorette.”

This declaration reads as a bold, principled stand—a move against the horse-racing and herd-thinking and hive-minding that have been longstanding sources of dissatisfaction with American political reporting. And on the one hand, sure, that’s partially what this is: It’s HuffPost, ever proud in its perspective, rejecting the easy conveniences of news categories and claiming that not all candidates—not all “candidates”—deserve the press attention traditionally accorded to those who seek the White House.

There’s a subtlety to the logic here. HuffPost’s statement isn’t claiming that Donald Trump, currently a leading presidential candidate in a crowded GOP field, doesn’t deserve coverage; it is claiming instead that Donald Trump, currently a leading presidential candidate in a crowded GOP field, deserves neither his front-runner status nor the attention that comes with it. Polls and press coverage, after all, are notoriously chicken-and-egg-y. And HuffPost, of course, is taking an opinion that many Americans share—that Trump is a wind-bagging buffoon—and converting it into an editorial stand. That is its right as a publication. It is also, to the extent that the what of news coverage is as journalistically important as the how, its duty.

And yet. The Republican primary electorate seems to disagree with HuffPost. You can quibble with the polling numbers, sure; it is another matter to ignore them.

There’s also the fact that most readers, who come to news articles via Facebook or Twitter or URLs emailed by friends, pay zero attention to the section that happens to house a given story—meaning that Trump stories with “entertainment” buried in their URLs are essentially the same as Trump stories with “politics” buried in them. (You could also add that HuffPost’s Entertainment vertical likely gets much more traffic than its Politics vertical—meaning that the move will likely end up generating more, not less, attention for Trump, bringing his antics to the notice even of those readers who generally ignore politics. Nor has HuffPost foresworn the revenue from the ads served alongside these stories.)

The other issue, though, is that HuffPost, with its announcement, may be drawing a line between politics and entertainment that is impossible to discern in 2015.

Yes, granted: Trump—cf. the excess of outraged takes on his excessively outrageous comments, the emerging wire-photo sub-genre that delights in capturing his orange-hued face mid-yell—is on top of all else an entertainer. Granted: He connects, according to the best metrics available, with large swaths of the American electorate. Granted: He is a reality-TV star, and applies the skills required of that work to his campaign.

Which is also to say that Trump, in his candidacy, is being exactly who we want him to be. “We” as participants in the media system as it currently operates, and “we” as that hazy body commonly shorthanded as “the American public.” We ask—actually, we demand—that our politicians be not just intelligent and well-informed and quick-witted and concerned about, as it usually goes, “people like me,” but also that they be sources of drama and distraction and indignation and delight. They should be charming, but not smarmy. Well-spoken, but approachable. Good-looking, but not vain about it. Vying as they are to be entertainers-in-chief as well as commanders-in-chief, they should be skilled at both delivering zingers at the White House Correspondents Dinner and issuing orders in the Situation Room. They should channel hopes and fears and the past and the future, inspiring effortlessly, delighting daily, serving, metaphorically, at once as parents and pals.

And they should be, above all—a mandate that reveals much more about the American people than it does about those who seek to lead them—people they’d want to have beers with.

Well. You know who’d probably be extremely entertaining in a bar? Donald Trump.

And you know who had some real zingers on Morning Joe the other day? Donald Trump.

And you know who’s currently feuding, zestily, with Rick Perry? Donald Trump.

And you know whose quotes are often “better than freebasing”? Donald Trump’s.

And you know whose hairdo looks really funny when Photoshopped onto the assorted cats of the Internet? Donald Trump’s.

And that, finally, is the problem—with political news coverage in general, with the expectations of the American electorate, and with a widely read news outlet dismissing a leading presidential candidate, sneeringly, as “Entertainment.” The primacy of the screen in our current method of candidate-screening has meant that politics is, at this point, largely indistinguishable from pop culture. Celebrified candidates are part of the compact Americans have made with their political news, because policy can be boring and learning the new things requires understanding the old ones and the stakes are so high and voters are all very human and tired. Attention is one of the most powerful things Americans have to give; news outlets reward them for it not just with pertinent information about “the issues,” but also with juicy soundbites and indignation-inducing video clips and distractingly delightful comparisons of candidates to cats.

In that sense: You can disagree, vehemently, with Donald Trump. You can find him ridiculous, his views abhorrent, his whole person a little bit monstrous. What you cannot do, however, is ignore Donald Trump. He is there, and there he will remain. Giving Americans no more, and no less, than what they’ve asked for.

July 17, 2015

Eyes Wide Shut

“I’m in somebody else’s house. How did I get here?” says an elderly man, with deepening fear. He’s blind and deaf, scooting himself across a dusty floor on his knuckles, his voice growing more urgent as his thin fingers reach out to touch the walls of his own home. “Help me,” he cries. “I’ve wandered into a stranger’s house ... He’s going to beat me up!”

Related Story

Reenacting War to Make Sense of It

There are any number of scenes like this in Joshua Oppenheimer’s breathtaking new documentary The Look of Silence, in which a 44-year-old optometrist named Adi Rakun confronts the men who killed his brother in the 1965 Indonesian genocide of more than a million alleged Communists. The film is laden with similar moments: symbolic and resonant, but rooted in a grim reality. The man crawling on the floor is Adi’s father, who suffers from dementia, and at times believes he’s reliving his experiences as a teenager.

The film, which opened for a limited U.S. release Friday, is the companion to 2012’s Oscar-nominated The Act of Killing, which offered a harrowing look at the aging perpetrators of the U.S.-backed genocide in Indonesia. Today, many of those men are still in power. Celebrated as national heroes, they brag openly about the mass murders they committed, reenacting for Oppenheimer in detail how they strangled, tortured, and beheaded people.

The first movie attempts to understand the circumstances that created an environment for such men to be revered, how the killers truly see themselves, and whether they’re capable of repenting for their actions. Released three years later, The Look of Silence switches to the perspective of the survivors and the victims’ families. The old man crawling on the ground is the ailing father of Adi, the film’s central character, whose brother, Ramli, was among those murdered by paramilitary groups two years before Adi was born. With the help of Oppenheimer, who remains a largely invisible force behind the camera, Adi finally confronts his brother’s killers face-to-face. The documentary looks at what it’s like to live surrounded by the people who murdered your family—and how dangerous it can be to seek truth and healing in a country with a legacy of lying about and defending atrocities.

Though Adi didn’t witness firsthand the choking effects of violence, he grew up in a village that did. He learned of Ramli’s death from his mother (the only person who would speak about him), and, later, from Oppenheimer’s on-camera interviews with the perpetrators. The audience, in some ways, learns and processes facts alongside him. In scenes interspersed throughout the film, Adi sits quietly in an empty room before an old TV set. In one, he’s watching an excerpt from a 1967 NBC News report, where an Indonesian man tells a receptive American journalist how beautiful his country is now that it’s been cleansed of Communists. In other scenes, Adi watches two old men reenact with glee how they’d slit people’s throats, castrate them, and drag them through the fields to be dumped into the river.

But in the film’s most gripping scenes, Adi sits with his brother’s killers in real life—often while testing their eyesight—and asks them to take responsibility for their crimes. Before knowing Adi’s identity, most eagerly profess their deeds. One admits to bringing a woman’s head into a store to frighten the Chinese owners, and others to drinking their victims’ blood because it was the only way to avoid going crazy. “Both salty and sweet, human blood,” the death-squad leader, Inong, tells Adi, unprompted, during their exchange. “Excuse me?” Adi asks, as if unsure he’d heard correctly. “Human blood is salty and sweet,” Inong repeats.

After enough of these kinds of unimaginable details—both The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence are rife with them—it’s easy as a viewer to feel numb. Not from desensitization, but from the exhaustion of being pulled apart by competing emotions: horror, disgust, and disbelief on one hand, and admiration and empathy for Adi on the other, who never once even raises his voice with his guests. His bravery—there’s no other word for it—causes his family to balk once he tells them he’s been meeting with Komando Aksi death squad leaders. “Think about your children!” his wife warns him. His mother advises him to carry a butterfly knife or a club, and to not drink anything he’s offered in case there’s poison in the cup (“Tell them you’re fasting,” she says.)

Drafthouse Films

Drafthouse Films In The Look of Silence, “blood-thirsty,” has literal meaning. “Eviscerating” and “heartrending,” too. To say that the film cuts deeply feels wrong, after hearing veteran executioners discuss how they removed the limbs of their victims. And so it’s no surprise that when the film ends, for many viewers, the only response that might feel right is to say nothing at all for a while.

But to do that is to do an injustice to the movie. Neither Adi nor Oppenheimer are passive witnesses to what they discover. While Adi’s job is to correct the vision of others, he also tries to rectify their flawed vision of themselves and their place in history. He tells the killers that their truth is mere “propaganda.” He tells his son that his teachers are lying when they say the Communists were evil and had to be crushed.

Oppenheimer’s own hand in the film is invisible but critical. Adi encouraged him to collect the stories of the killers, but Oppenheimer also paved the way for Adi to meet with them safely by ingratiating himself to leaders and paramilitary groups. After speaking with dozens of perpetrators, he came to understand their revisionism as a symptom of collective ignorance. “Because they’ve never been removed from power ... they try to take these bitter, rotten memories and sugarcoat them in the sweet language of a victor’s history,” Oppenheimer told me. If The Act of Killing strips away the facade to reveal the killers’ hypocrisy, The Look of Silence looks at the lies both the perpetrators and victims have told themselves for decades in order to survive.

Even for a film that chooses to convey horror in close-up, The Look of Silence’s message finds broad relevance across geopolitical lines. The film doesn’t shy away from the U.S.’s role in the genocide: In one scene, a murderer says he should be rewarded with a trip to the U.S. for his work; in another, a perpetrator says, “We did this because America taught us to hate Communists.” The Indonesian genocide, Oppenheiemer said, is as much America’s history as the mass killing of Native Americans. He thinks the film should also prompt viewers to think of America’s involvement in other wrongdoings, past and present, that allow its citizens to lead comfortable lives with cheap electronics, clothes, and oil.

And yet. “It’s very moving to me that the film is coming out in the United States this summer, after a particularly traumatic year in which we’ve been reminded again and again ... in unmistakable ways, of the open wound of race right here,” Oppenheimer says. The last thing he wants is for people to see The Look of Silence as “as a window into a far-off place about which we know little and care less.” The spirit of Indonesia’s anti-Communist killings, which lasted from 1965-1966, isn’t so foreign: Oppenheimer describes America’s history of racism in more global terms. White supremacists and the Klan were effectively “neo-Nazi paramilitary mobs” who carried out “state-sanctioned terrorism ” through lynchings and other acts of violence against blacks. He recalls his own childhood, going to high school in suburban Maryland, where his mostly white magnet school within a majority-minority school was effectively legal “apartheid.”

An American listening to Oppenheimer might feel defensive, or ashamed. But The Look of Silence is about how this impulse to turn away from blunt truths—about one’s country and history—harms progress and reconciliation. In Adi’s case, people would chastise him for bringing up “politics” or for “opening a wound” every time he talked about his brother, whose name had become verboten in his village as shorthand for the entire genocide. Before change can unfold at the top, transformation needs to happen at the bottom. “You can’t have democracy without community, and you can’t have community if everyone’s afraid of each other,” Oppenheimer said.

And change is happening. After The Act of Killing was nominated for an Academy Award, the Indonesian government finally acknowledged the genocide, saying that the country would deal with it in its own time. The Look of Silence has been screened over 3,500 times to more than 300,000 people in Indonesia. Many of those people, Oppenheimer said, are relatives of the killers, but the film offers a hopeful blueprint for how generations living in the shadow of past crimes can come together, and move forward.

Drafthouse Films

Drafthouse Films All these lessons take time to materialize fully. The Look of Silence is an inherently political film, but not one that ends with a lengthy text crawl imploring the audience to do their part and change the world. Like its predecessor, it’s a devastatingly beautiful film about the power of cinema, and its ability to testify to some aspect of human nature with a veracity and elegance that escapes other mediums. Every scene weighs on the audience. But Oppenheimer and Adi manage to locate a lightness as well that lessens the burden.

A Year After Eric Garner's Death, Has Anything Changed?

July 17, 2014 seems to have started as a normal day for Eric Garner. By the middle of the afternoon, Garner, who was out on bail for several minor offenses, including selling single cigarettes, was on the sidewalk in Tompkinsville, on Staten Island. He had reportedly just broken up a fight when police approached him about selling loosies. Police arrested him, and placed him in a banned chokehold as he protested—over and over—that he couldn’t breathe. Within an hour, the 43-year-old was dead at a hospital.

Friday marks the one-year anniversary of Garner’s early death, and with that it marks the one-year anniversary of the United States’ focus on police violence against black Americans. The story didn’t achieve full national attention until a month later, with Michael Brown’s shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, but Garner’s death provides a starting point for a litany: Garner, Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray—and many others whose names are unknown or less known. Garner’s last words, the repeated plea “I can’t breathe,” have become a slogan for protestors against police violence across the United States.

Garner’s death was not, of course, the beginning of a pattern; it was only the beginning of a new awareness and attention within the media to something many African Americans have endured and discussed for decades. My colleague Ta-Nehisi Coates has connected police violence against African Americans with a national identity based on the plunder of people of color stretching back to before the nation’s foundation. But the year has been important and potentially pivotal. These stories aren’t going away—this week, there’s a new mystery with the death of Sandra Bland. Here are three important lessons for Americans since July 17, 2014.

Related Story

The Fitful Journey Toward Police Accountability

First, deaths like this are far more common than many Americans understood. Garner and Brown’s deaths raised two closely related questions: How many people are killed by police every year, and how many people are shot by police each year? People who wanted to know—from reporters to FBI Director James Comey—seemed surprised to learn that there are no reliable statistics to answer that question. Two heroic projects from The Guardian and The Washington Post have gone a long way toward answering the deaths and shooting-death questions, respectively. This isn’t a role that should fall to journalistic organizations, though—the government needs to reliably track the statistics.

Second, building awareness about police violence has proved much easier than doing something about it. Officer Darren Wilson, who killed Michael Brown, was not indicted by a grand jury in St. Louis County. Officer Daniel Pantaleo, who choked Garner, was not indicted by a grand jury on Staten Island. Six Baltimore police officers have been charged with crimes in Freddie Gray’s death, but it remains to be seen whether prosecutor Marilyn Mosby will be able to convict them on the most serious offenses. Baltimore is a particularly disheartening case—although Mosby’s action has been praised as a major step forward—because prosecutors are often wary of charging police, with whom they work every day. It’s been clear for many years that Baltimore’s police department has serious issues with brutality, and the city has had to pay out millions in settlements. Yet Baltimore’s reformist police commissioner, detested by the police rank and file, was just fired amid a spike in crime, which some people think was caused by a work slowdown by those same officers.

Even as traditional methods of cracking down on such abuses have come up short, activists, officials, and victims’ families have found alternative means of holding police to account. Foremost among those is forcing legal settlements and bringing civil cases where criminal cases fail. With the anniversary of his death approaching, Eric Garner’s family reached a $5.9 million wrongful-death settlement with the city of New York, though some people worry that the agreement doesn’t change anything since it has no material effect on police practices. At some point, though, it seems inevitable that the cost of compensation for police brutality will force cities to change practices. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that the 10 cities with the biggest police departments paid out almost $250 million in settlements last year and more than $1 billion over the last five.

Activists have also found a willing and powerful partner in the Department of Justice, which has used civil-rights investigations and consent decrees to force cities around the nation to reform their practices, including in Cleveland and Ferguson. There are other unconventional tactics in use, too—like the civil-rights leaders in Cleveland who discovered an obscure law that could be used to force a magistrate judge to consider arresting an officer in Rice’s death. The effort failed to obtain a warrant, but it renewed attention and spotlighted the local prosecutor’s slow pace in deciding whether to charge officers over the 12-year-old’s shooting.

Third, there’s still so much that the public doesn’t know and much that is left to police discretion. This already-bleak anniversary is made darker by the mysterious death of Sandra Bland. The 28-year-old black woman from Chicago was on driving to Texas for a new job when she was stopped by police near Houston for failing to use a blinker. During the traffic stop, she was eventually arrested in Waller County by a state trooper for assaulting a public officer, arraigned, and sent to jail on $5,000 bail. On Monday, she was found dead in her cell of what the sheriff says is self-inflicted asphyxiation.

Bland’s family rejects that—they don’t believe that she would have hurt herself, noting that she seemed in high spirits even after her arrest on Friday, and saying it’s generally out of character for her. The FBI has now joined the investigation, and a video has surfaced that reportedly shows part of the arrest. But by the time the clip begins, an officer is already physically subduing Bland. There’s still a great deal that is unknown about her arrest and death. Are stops for failing to use blinkers routine in Waller County, or used as pretexts for pulling over certain kinds of drivers? What happened between the driver and the officer? Was Bland the aggressor, as police have it, or was the officer at fault? Are there other recordings of the stop? Did the police act appropriately? What happened between Friday afternoon and Monday morning as Bland waited in her cell?

Many of these things may be unknowable, and others will emerge over the coming days and weeks. What’s clear from the start is that a traffic stop for failing to signal a lane change, involving an African-American woman with no apparent criminal record, somehow escalated to a physical altercation between the officer and the driver and ended with a young woman dead in a county jail cell. Eric Garner’s death one year ago may have been the beginning of Americans paying attention to police violence against people of color, but Bland’s death shows why the anniversary doesn’t offer any closure.

When Is the Use of Force by Police Reasonable?

The Supreme Court handed down a case in June, hidden among the end-of-term blockbusters, that created an important new constitutional protection against police violence. In Kingsley v. Hendrickson, the justices articulated a standard for judging the conduct of police officers accused of using excessive force on suspects being held in pretrial detention.

Justice Stephen Breyer, writing for the majority in a 5-4 ruling, found that whether the police intended to use excessive force was irrelevant. The standard, Breyer argued, should be whether a reasonable observer would view the use of police force as excessive. By taking this route, the Supreme Court departed from the extraordinary deference that the law traditionally gives police testimony. Preceded by a year of visceral imagery of black deaths caused by police violence, the decision in Kingsley reflects a widening rift between community and police perceptions of the legitimacy and appropriateness of police force.

In 2010, Michael Kingsley was being held in jail on drug charges as a pretrial detainee in Monroe County Jail in Sparta, Wisconsin. Kingsley had taped a piece of paper to the light cover above the bed in his cell. A deputy in the jail ordered him to take it down. The deputy complained to his commanding officer when Kingsley didn’t comply. Again and again, Kingsley refused to move the paper, and was issued a “minor violation.” Four police officers eventually forcibly removed Kingsley from his cell and carried him to a receiving cell where he was left in solitary confinement.

Related Story

Why Police Can't Be Trusted to Decide If Video Should Be Public

That much is undisputed; what followed next is less clear. Kingsley testified that a sergeant kneed him in the back, and that two officers then slammed his head into a concrete bunk. This caused him pain so severe that he couldn't immediately walk again. The jail officers, by contrast, said that Kingsley was resisting their efforts to remove his handcuffs. At this point Kingsley was handcuffed and lying face down. Both parties agreed that the officers finally ended the altercation by applying a taser to Kingsley’s back for around five seconds. Kingsley recalled an officer saying, “Taze his ass!” just before the electric shock.

The Eighth Amendment, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment,” only applies to prisoners who have already been convicted of a crime. The Fourth Amendment is generally interpreted to protect against unreasonable police actions against people prior to their arrest. Before Kingsley, people who had been arrested and detained, but not yet convicted, fell into a legal void.

To fill in the constitutional gap, Kingsley argued at trial that the officers’ use of excessive force violated his civil rights under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause—one of the cardinal provisions of the Constitution. It forbids any state actor, such as a police officer, from depriving a person of “life, liberty or property without due process of law.”

The case turned on what instructions should have been given to the jury at trial level. Kingsley argued that the words “reckless” and “reasonable belief” had been repeatedly and improperly used in the jury instructions. The Court agreed. During oral argument, Justice Sonia Sotomayor observed that police officers seemed to want the authority to “get a free kick” when managing pretrial detainees. The Court’s decision makes it harder for police and corrections officers to get that constitutional free kick.

The Court’s decision makes it harder for police and corrections officers to get that constitutional free kick.Kingsley marks a departure from a traditionally deferential posture to police testimony both inside and outside courtrooms. In the 1985 case of Tennessee v. Garner, the Court ruled that so long as police officers have a reasonable belief that his life or others are in danger, their use of force will likely be proportionate in light of the government’s interest in effective law enforcement. The Eighth Amendment bars only correctional force applied with “deliberate indifference,” or exercised “maliciously” or “sadistically” against inmates.

The less deferential holding in Kingsley supports research showing that ordinary citizens hold very different views than the police on the perception and tolerance of abuse of force. A recent study of 3,230 sworn officers in 30 American police departments showed that new or novice officers were more likely to view excessive force as worthy of severe discipline than officers with a moderate level of experience. These newer officers were also more likely to report such incidents than their more experienced peers. This suggests a gap between the public and police perceptions of excessive force, a gap that widens with exposure to institutional culture.

From Ferguson to Freddie Gray, demonstrations of public outrage against police killings highlight a growing gulf between the police and citizens. There is some evidence that this anti-authority zeitgeist has also permeated the courtroom: Some prosecutors and defense attorneys concede that the events of the past year have taken a toll on police credibility on the witness stand.

Kingsley also serves as a timely reminder that many pretrial detainees are charged with nonviolent offenses, and that they are held in custody only because they are too poor to secure their release before trial. In 2008, fewer than 18 percent of non-felony defendants in New York City courts posted bail when it was set at $500. Only 11.3 percent of non-felony defendants posted bail when it was set at $1,000. The enduring correlation between poverty and race means that city and county jails are often filled with poor people and people of color.

Ultimately, Michael Kingsley stood up for the idea that police not only protect, but also serve, the public. They should be held to the standards of the people that they serve. At the end of its term, the Supreme Court championed that prevailing public opinion.

Time Traveling With Tame Impala

People have worried about nostalgia strangling pop culture for decades, but 2015 might go down as the year it revealed its dastardly plot. The remake and reboot craze that’s long afflicted the movie industry has spread to TV. The biggest book of the year was written about 60 years ago. In music, the mega-smash “Blurred Lines” was legally ruled to be little more than a Marvin Gaye cover, and the credits for the defining track of 2015, “Uptown Funk,” now include five members of the Gap Band for work they did in 1979. Even outside of the mainstream, the situation is much as it was when Simon Reynolds wrote Retromania in 2011: “The very people you would have expected to produce (as artists) or champion (as consumers) the non-traditional and the groundbreaking—that’s the group who are most addicted to the past … The avant-garde is now an arrière-garde.”

Related Story

Did Rock and Roll Pacify America?

One of the new icons of this arrière-garde is 29-year-old Kevin Parker, the man behind the Australian buzz band Tame Impala. With the hairstyle of a deadhead and a voice that’s frequently compared to John Lennon’s, he has said that one of his main ambitions for Tame Impala’s third album, Currents, is to “convince a few die-hard rock fans that ‘80s synths can fit over a ‘70s drum beat.” The resulting sound, not to mention cover art, will induce flashbacks to such unfashionable touchstones as Yes, or even Toto.

But if the art of the present day is doomed to be mostly a remix of elements of the past, let it all be as knowingly done and moving as Tame Impala. To the extent that Currents is pastiche, it’s pastiche with a point of view, collapsing a few decades of psychedelic sounds into one lovely blur—time starts to sounds like a flat circle, and nostalgia starts to seem like a way of envisioning the future.

You can most clearly see what he’s up to on the album’s eighth track, “Past Life.” Between choruses as smooth as “Kokomo,” a keyboard melody seemingly lifted from an after-school special plays as a low, pitch-shifted voice talks about glimpsing “a lover from a past life.” At first, I assumed it all amounted to an affectionate appropriation of new-age spirituality. But then, at the end of the song, the narrator starts wondering whether this lover from a past life has changed her telephone number. It’s a reveal: He’s not blathering about reincarnation, he’s blathering about a real-world ex—and considering getting back together with her.

Parker works like this throughout the album, connecting ordinary-seeming relationship troubles with stereotypically hippy-dippy ideas about eternity and recurrence. Which isn’t, as it may sound, pretension; after all, it’s everyday problems, not visits to the Esalen Institute, that leads to most peoples’ existential questioning. Accordingly, even as the music evokes laser shows and soft-focus video art, the melodies remain sturdy, the song structures trend poppy, and the philosophy is also straight talk. “They say people never change,” Parker sings at one point, “but that's bullshit.”

When the album’s the most gobsmacking, which is often, is when the lyrical themes align perfectly with the musical ones. The first example: During an instrumental break in the opening track “Let It Happen,” the music gets stuck. Like, the song starts to skip; it sounds like the CD is scratched or your iTunes is frozen. But then some violins come in and the arrangement rebuilds itself, gorgeously, around the glitchy new groove. It’s a high concept gimmick that’s also moving—here’s reality moving like a stream, getting diverted by some obstacle, and making a new path.

Not all of the album lands so strongly; it wouldn’t be a psychedelic trip if you couldn’t zone out for a bit. But the highlights tend to wake the listener up, whether the listener’s ready or not. The best track, “Eventually,” arrives with distorted bass slams so vivid they make it seem like the speakers are busted (broken machines: another thematically appropriate trope—do not adjust your television, etc. etc.). “I know that I’ll be happier, and I know you will too /eventually” Parker sings, rationalizing a break-up in the most common way possible. But when those bass bombs reappear, the arrangement disintegrates, and the keyboards go all Bruce Hornsby-like, it becomes clear just how expansive he wants the word “eventually” to be. It could mean next week; it could mean next year; it could mean another life, when time has folded back up on itself and all of old music has been made new again.

Is There a Viable Alternative to the Iran Deal?

How to make sense of the nuclear deal with Iran? Is it a necessary compromise that’s preferable to the alternatives and potentially beneficial for the Middle East? A feeble and indefensible sop to Iranian leaders bent on further destabilizing the region? A practically satisfying but morally troubling gamble, born of bad options? The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart, David Frum, and Jeffrey Goldberg debate the new agreement—and the swift and fierce reaction to it.

* * *

Peter Beinart: David and Jeff, the thing that strikes me most about the reaction to the Iran deal is that proponents and opponents are judging it by radically different standards.

Opponents keep saying that this deal isn’t as good as the Obama administration promised it would be and that it violates previous U.S. red lines. That’s true. It allows Iran to keep some enriched uranium. It also doesn’t include anytime, anywhere, right-away inspections, which I think the Obama administration was foolish to promise (a kind of parallel to when they said no one would lose coverage as a result of Obamacare).

Related Story

Proponents, like myself, compare it to the alternatives: which are doing nothing, war, or trying to increase sanctions in hopes of getting a better deal down the line. What frustrates me is how rarely I see opponents explaining in any detail how any of these alternatives would be preferable. A few years ago, one saw more hawks arguing for a military strike. (I detailed some of the folks who did last year.) But one rarely hears anyone these days arguing that a military strike makes sense. Some say that a “credible threat of force” would make Iran concede more. But Israel and America have been threatening force for a decade now. Why would more saber-rattling work now? Besides, to have your threat of force be credible, don’t you have to be willing to follow through—which requires explaining why military action would be effective in retarding the nuclear program and wouldn’t make the current regional conflict far worse? More often, deal opponents talk about increasing sanctions, which would supposedly force Iran into concessions. But I rarely hear them explain how that will work given the internal politics of Iran. Seems more likely to me that scuttling this deal, and passing more sanctions, would devastate [Iranian President] Rouhani and [Iranian Foreign Minister] Zarif politically. Rouhani was elected to improve the economy; torpedoing the deal would make him a failure. That would empower those hardline opponents who never wanted any deal. Beyond that, what basis is there to believe European and Asian countries, which have strong economic interests in Iran, will maintain sanctions indefinitely? The lesson of Iraq in the 1990s is that sanctions erode over time. British and German diplomats have warned that if the U.S. destroys the deal, sanctions could unravel. So why should we believe economic pressure will go up and lead to more Iranian concessions? Seems at least as likely to me that economic pressure will go down.

If the most important thing is the potential for political change in Iran, and the people who would make that change want this deal, doesn’t that carry weight?I also don’t feel that opponents of the deal—who waxed moralistic about Obama’s failure to be vocal enough in supporting the Green Revolution—have grappled much publicly with what appears to be the overwhelming support of Iranian dissidents for this deal. If we believe that ultimately the most important thing is the potential for political change in Iran, and the people who would make that change want this deal, doesn’t that carry real weight? (I’m not saying this deal will bring political change anytime soon. Obviously, nobody knows if it will.) Call me cynical, but seems to me that hawks like using the Iranian dissidents when it helps them argue for a cold-war posture. But the minute it doesn’t, they pretend those dissidents don’t exist.

David Frum: What did the Western world get from the nuclear deal just concluded with Iran?

According to deal proponents—and assuming Iran does not cheat—a delay of about eight months in Iran’s nuclear-breakout time, for a period of 10 years.

What did the Western world give?

1) It has rescued Iran from the extreme economic crisis into which it was pushed by the sanctions imposed in January 2012—sanctions opposed at the time by the Obama administration, lest anyone has forgotten.

2) It has relaxed the arms embargo on Iran. Iran will be able to buy conventional arms soon, ballistic-missile components later.

3) It has exempted Iranian groups and individuals from terrorist designations, freeing them to travel and do business around the world.

4) It has promised to protect the Iranian nuclear program from sabotage by outside parties—meaning, pretty obviously, Israel.

5) It has ended the regime’s isolation, conceding to the Iranian theocracy the legitimacy that the Iranian revolution has forfeited since 1979 by its consistent and repeated violations of the most elementary international norms—including, by the way, its current detention of four America hostages.

That seems one-sided. Deal proponents insist: With all its imperfections, this is the very best deal obtainable. The only practical alternative is war.

Is that true?

The United States did not negotiate the way people negotiate to get the best deal obtainable. It signaled from the start of the talks that it regarded the military option (supposedly always “on the table”) as in fact unthinkable. It collared Congress to prevent imposition of new sanctions when the Iranians acted balky. It was a mistake too to send the secretary of state to head the delegation, especially a secretary of state who had been a presidential nominee: Secretary Kerry was too big to be allowed to fail. His Iranian counterpart, by contrast, could easily be disavowed by a regime whose supreme authority always maintained a wide distance from the talks.

The Western world has conceded to Iranian theocrats the legitimacy that the Iranian revolution has forfeited since 1979.Nor is the administration enacting its agreement as if it felt confident of its merits. The administration invented an approval process that marginalizes Congress. The agreement becomes binding so long as just one-third of the members of either House support it. For an administration that has complained so much about the anti-democratic filibuster, that’s quite a bold departure from the normal constitutional rule.

The administration brought home a weak deal, having negotiated in a way that put a better deal out of reach. Now it challenges critics: Accept this weak agreement or fight a war. But it’s the deal’s authors who created a false and dangerous choice. As we think about what comes next, keep in mind how we arrived where we are.

Jeffrey Goldberg: Let me say at the outset that I agree with Peter.

Also, I agree with David.

Within the political and moral framework the Obama administration and its allies created for themselves, this deal has many positive features. As an arms-control initiative, it seems as if the Vienna agreement could keep Iran from reaching the nuclear threshold for many years (20 years is President Obama’s provisional measure of success, at least when I asked him in May). This deal could also prevent an eventual military confrontation between the U.S. and Iran, or Israel and Iran. I put great stock—sorry, David—in the argument that opponents of this deal should be forced to come up with a better alternative. I haven’t come up with anything. I do think, in the absence of a deal, we would be looking at an Iran soon at the threshold, or at a military operation to delay the moment when Iran could cross the threshold. (Delay, not defeat, because three things would happen in the event of an American military strike: Sanctions would crumble; Russia would become Iran’s partner; and the ayatollahs would have their predicate to justify a rush to the bomb. Only more bombing could stop them, and then, of course, we would be talking about a never-ending regional war.)

We’ve signaled to Iran’s leaders that they have a right—a previously unknown right in the vast catalogue of rights accorded to sovereign states—to enrich uranium.All that said, this agreement is morally troubling, and it may also lead to precisely the thing that arms-control agreements are meant to prevent: broad instability. It is morally unsatisfying because innocent people of the Middle East will most likely suffer its consequences. Certainly, an enriched Iran—sponsor of the world’s most bloodthirsty regime, in Syria, and sponsor, as well, of the world’s most potent anti-Semitic terrorist group—will be able to help its proxies in ways it couldn’t before. This is one of the principal reasons the Israeli opposition leader, Isaac Herzog, is joining his archrival, Benjamin Netanyahu, in raising the alarm about the deal, and it is the principal reason the people of Syria feel abandoned by the West. This agreement may also cause further instability across the region, not only because an empowered Hezbollah might decide that it is time for another rocket war with Israel, but because it might encourage the Iranian regime’s worst hegemonic, anti-Sunni impulses.

As an arms-control measure, this agreement has good qualities. I’m not discounting David’s specific critiques, not at all, but this agreement does represent the first successful attempt to curtail Iran’s nuclear ambitions. This deal, however, represents a huge gamble. If the unspoken, but widely understood, theory of Obama’s case turns out to be incorrect—that the Vienna accord will stimulate a virtuous cycle, one which sees Iran’s moderate, mercantilist, pro-American tendencies encouraged, and ultimately triumphant—then we’ve just empowered a group of theocratic fascists to feel as if there is an even bigger role for them to play in the Middle East, and we’ve laid out a pathway for this regime to eventually reach the nuclear threshold. We’ve certainly signaled to Iran’s leaders that they have a right—a previously unknown right in the vast catalogue of rights accorded to sovereign states—to enrich uranium, which is quite a thing to signal to a country designated by the United States as a committed and energetic sponsor of terror.

Beinart: Jeff, obviously, I agree with you on the nuclear part. On the regional part, I kept waiting to read the acronym “ISIS.” I agree that more money to Hezbollah and Hamas is bad. I think that’s the strongest objection to this deal, although somewhat mitigated by the fact that sanctions would likely have eroded anyway.

But we can’t talk about Iran’s position in the region without acknowledging that today, the group most likely to commit another 9/11 on U.S. soil is ISIS. And Iran wants very badly to destroy ISIS, which is, after all, a genocidally anti-Shia group near their border. There are problems with Iran’s fight against ISIS, of course. It alienates the Iraqi Sunnis who we need to turn against the jihadis in their midst. But on the ground, Iran is the most potent force fighting ISIS—and if it has more money to do so, that’s not all bad. What’s more, if this deal makes it possible for the U.S. and Iran to coordinate their fight against ISIS more effectively, that’s good for American national security. And morally, if we can liberate the people who’ve been living under ISIS hell for the last year, that’s good too.

ISIS is the greatest threat and Iran, like Stalin during World War II or China during the Cold War, is a highly problematic partner against it.To my mind, one of the biggest problems with much contemporary Beltway foreign-policy discourse is the refusal to prioritize, to accept that foreign policy sometimes requires working with the lesser evil, which is still really evil. From a national-security and moral perspective, ISIS is the greatest threat and Iran, like Stalin during World War II or China during the Cold War, is a highly problematic partner against it. But in terms of ability to project power, it’s the best partner we’ve got.

I also think that the history of the 20th century shows that cold wars produce regional wars that are brutal for the people whose countries become battlegrounds. Syria is a proxy war, partly between the Sunni powers and Iran, and partly between the U.S. and Iran and Russia. If there’s ever going to be a deal to end that nightmare, Iran is going to have been at the table, along with the U.S. If Iran doesn’t feel the U.S. is going to attack it, it becomes easier to imagine that Tehran could accept a deal where [Syrian President] Assad goes. I’m not saying this is going to happen anytime soon, but when the Cold War ended, proxy wars ended across the globe. And if the cold war between the U.S. and Iran thaws, it makes it easier to craft a solution in Syria. It also makes it somewhat easier to imagine a political solution in Afghanistan, a country where Iran has significant influence.

I’m not claiming this deal will produce wonders regionally. But I think it’s at least as likely to produce more stability as more instability, especially given, as you rightly note, that the alternative, sooner or later, is quite likely a U.S.-Iranian war.

Frum: There’s a curious two-step on display in defense of the deal.

Step One

Critic: “This deal leaves four Americans in Iranian detention … delivers tens of billions of dollars to Iran for aggression and terrorism … and generally empowers Iran to make mischief in the region and around the world.”

Defender: “This deal is not intended to solve all our problems with Iran. We accept that Iran is dangerous and hostile. The agreement is narrowly focused on solving one problem: the Iranian nuclear bomb. That’s our top priority.”

Step Two

Critic: “OK, but as an arms-control measure … this deal is very weak. Iran will retain a big nuclear-weapons capacity. It will continue to spin centrifuges. The inspection regime is weak. Reimposing sanctions if Iran cheats will be difficult.”

Defender: “Don’t be so narrowly focused on the deal’s technicalities! What we have here is a once-in-a-generation chance to reshape the Middle East, to recruit Iran as a security partner. This is a Nixon-goes-to-China strategic realignment!”

* * *

The deal is being sold, in other words, as both a breath mint and a floor wax. Unsurprisingly, it succeeds at neither.

Remember Don Rumsfeld’s famous “Rules”? One of them was, “If you don’t know how to solve a problem, make it bigger.” I think Peter may be executing that rule right now. As the costs of the deal have risen—as its benefits have dwindled—the hopes attached to it by its advocates have inflated. If they can’t sell the deal on its arms-control merits, then they’ll promote it as the dawn of a new strategic rapprochement between the United States and Iran.

The deal is being sold as both a breath mint and a floor wax. It succeeds at neither.ISIS? ISIS should represent a much nearer and more immediate threat to Iran than for the United States. Iran should be making concessions to the U.S. for help against ISIS, not the other way around. If that’s not happening, it may be because the relationship between ISIS and Iran—and Iran’s Syrian client—is as much symbiotic as antagonistic.

Peter, I agree with you about the importance of priorities. A nuclear weapons-capable Iran is a priority-one threat to U.S. and Western interests in the Gulf area. That’s the thing we need to stop. It is the thing President Obama promised to stop. This agreement does not stop that outcome. At best, it delays the outcome for a decade, at the price of immediately enhancing Iran’s power in every other dimension. At worst, it offers Iran a Magna Carta for nuclear cheating on the way to an early nuclear-weapons breakout.

Goldberg: Let me respond to David’s cleverly rendered two-step, in particular his characterization of this deal as a weak arms-control measure. I am with him on other matters: I agree that ISIS poses a greater threat to Iran than it does to the U.S., and I would hope that the U.S. would communicate this notion to the Iranians. And, as I’ve said before, I agree with David—presumably, the “critic” in the two-step—that the release of funds to Iran is going to spark more aggression and terrorism (though, to be fair, Iran has used its limited terrorism dollars fairly effectively over the past couple of decades).

But on the matter at hand, the putative weakness of the current deal, well, I’m not so sure. No arms-control agreement is perfect—no arms-control agreement with the Soviet Union was perfect—but if this deal is properly implemented, it should keep Iran from reaching the nuclear threshold for at least 10, if not 20 years. I’m aware of the flaws, and I hope they get fixed. The lifting of the international arms embargo is a particularly unpleasant aspect of this deal. But I’m not going to judge this deal against a platonic ideal of deals; I’m judging it against the alternative. And the alternative is no deal at all because, let’s not kid ourselves here, neither Iran nor our negotiating partners in the P5+1 is going to agree to start over again should Congress reject this deal in September. What will happen, should Congress reject the deal, is that international sanctions will crumble and Iran will be free to pursue a nuclear weapon, and it would start this pursuit only two or three months away from the nuclear threshold. My main concern, throughout this long process, is that a formula be found that keeps nuclear weapons out of the hands of the mullahs without having to engage them in perpetual warfare—which, by the way, would not serve to keep nuclear weapons out of the hands of the mullahs. War against Iran over its nuclear program would not guarantee that Iran is kept forever away from a bomb; it would pretty much guarantee that Iran unleashes its terrorist armies against American targets, however.

Iran was once pro-U.S. and pro-Israel, and it will be again. In the meantime, I’d rather have weapons inspectors crawling all over the regime’s nuclear facilities.David writes that “this agreement does not stop” Iran from becoming a nuclear-capable state. “At best,” he says, “it delays the outcome for a decade, at the price of immediately enhancing Iran’s power in every other dimension."

Please, someone, show me an agreement that would prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear weapons-capable state forever. Show me another path and I’d be happy to see the United States go down it, because I don’t want to see Iran become a regional superpower, and I don’t want the Assad regime, or Hezbollah, to become rich out of this deal. I wish I could believe, as some people do, that the Iranian regime will soon move toward moderation and responsibility. I’d be overjoyed to see it happen, and one day it will happen—Iran was once pro-U.S., and pro-Israel, and it will be again. I just don’t know when. In the meantime, I’d rather have weapons inspectors crawling all over the regime’s nuclear facilities, and in its uranium mines and mills, than not have them there. I’d rather have a deal in place that stands a good chance of keeping a country that seeks the annihilation of Israel from gaining control of a weapon it could use to bring about that annihilation.

Beinart: Not to pile on David, but your proverbial agreement “defender” doesn’t correspond to anyone I know of. Certainly not President Obama. The defenders of this deal don’t concede that it’s weak on nuclear controls and then move on to its supposed regional benefits. Whether or not we think there are regional benefits (I’m somewhat more optimistic than Jeff), we generally plant our flag on the claim that it’s better at curbing Iran’s nuclear program than any plausible alternative. And from what I’ve seen, it’s the regime critics who move on to the regional dangers without ever answering that challenge. They never present a plausible scenario—either economic or military—that leads to a better deal. The critics just vaguely suggest that if Obama had been more steadfast and less conciliatory, we could have bent Iran—and the other world powers—to our will and made Tehran capitulate entirely.

You, like Jeff and I, have been writing about foreign policy since 9/11. My core question is: What has happened in the last decade and a half that gives you reason to think the U.S. has the power to do that? It seems to me the lessons of our era cut sharply the other way: From Afghanistan to Iraq to Libya to North Korea to Russia, we’ve been reminded again and again that we cannot successfully impose our will on other countries through economic and military pressure. We’ve paid a terrible, terrible price for that delusion. I wonder what you’ve seen that leads you to a different conclusion.

Frum: I think we’ve just seen a perfect execution of the two-step. Having veered into the importance of recruiting Iran to stop ISIS, we’re now back in the territory of claiming there could be no better deal. But on its merits … it’s a weak deal. The delay in Iran’s nuclearization is short, temporary, and readily reversed by cheating. The infusion of financial and military strength to Iran is immediate and permanent.

U.S. negotiators feared the use of U.S. force more than the Iranians feared it, and were bedazzled by mirages of U.S.-Iranian regional cooperation.As to Peter’s final question: Could we have done better with a tougher-minded negotiating team? I think so, but maybe I’m wrong. What is certain is that we had a negotiating team who wanted a deal more than the Iranians, even though the Iranians needed it … who feared the use of U.S. force more than the Iranians feared it … who were bedazzled by mirages of U.S.-Iranian regional cooperation … and who balked at any additional measure of economic pressure during the negotiations. Maybe we couldn’t have gotten more—or paid less—if the administration had been stronger and less naive. What we know for sure is what we got from a team that was weak and in thrall to illusions. To make a success of this unsatisfactory result, the West will need to put a very different kind of team in charge of implementation and enforcement.

Goldberg: I think Peter and David both raise interesting points in this last round. Peter’s question to David is particularly apt: What has happened over the past 14 years to suggest that the United States possesses the power to make the Iranians capitulate entirely? Like many Americans, and many Israelis, and many Arabs—and many Iranians—I would like to see this regime collapse on itself. One day it will. I don’t think, however, that we have the power to force this perfidious regime to capitulate. As I’ve argued before, I don’t even think that air strikes could force a total capitulation; quite the opposite: Nothing motivates a proud people—even a proud people intensely dissatisfied with the men who rule them—to do the thing you don’t want them to do quite like an extended bombing run.

I’m trying to be practical in my approach to this issue, and David raises important issues going forward about the quality and intensity of implementation and enforcement. I want to believe that the West, and the International Atomic Energy Agency, are ready for the task ahead; I’m not so sure about this, however. This should be a focus of the Obama administration’s efforts. Another focus should be a ramped-up program of conventional containment: The U.S. should do more than it’s been doing to check Iranian adventurism across the region. A strict enforcement regime, combined with an enthusiastic anti-Hezbollah, anti-Assad, anti-IRGC campaign—these could combine to make a success of what David believes to be an unsatisfactory result.

Go Set a Watchman: What About Scout?

Exactly 100 pages into Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, the illusions of Jean Louise Finch and several generations of idealists are shattered when, arranging her father’s pile of reading material on a visit home from New York, Jean Louise discovers a pamphlet called “The Black Plague.” She picks it up, reads it all the way through, then takes it “by one of its corners … like she would hold a dead rat by the tail” and throws it in the garbage.

“Jean Louise,” her aunt says, in response to her indignation. “I don’t think you fully realize what’s been going on down here.”

Related Story

Harper Lee: The Sadness of a Sequel

It’s an awakening that’s not so much rude as cruel: Maycomb County, Alabama, is now a different world from the one she grew up in, and To Kill a Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch, the paragon of the legal profession, the father figure and steward of the nation’s conscience, is revealed to be frail and flawed. He is, at 72, a rheumatic and unrepentant segregationist who believes with complete conviction that the white race is superior. “Jean Louise, have you ever considered that you can’t have a set of backward people living among people advanced in one civilization and have a social Arcadia?” he asks late in the book, to her horror. “Do you want Negroes by the carload in the our schools and churches and theaters? Do you want them in our world?”

The publication of Watchman has been mired in controversy, and the knowledge that a much-beloved figure in an incomparable work of American literature was once portrayed by his author as an indefensible racist promises to be no less so. The murky origins of the book (it was reportedly found by Lee’s lawyer in a safe-deposit box last year, although that account has been disputed), the uncertain agency of Lee in its publication, and the squirminess with which the publisher, HarperCollins, has presented the novel as a newly discovered manuscript rather than a rejected first draft of Mockingbird or a failed sequel: Every step of the book’s rollout has added to a sense of unease.

HarperCollins

HarperCollins But for all its flaws—a meandering, distinctly unfinished style; stilted dialogue; an unsatisfactory ending—Go Set a Watchman is worth welcoming. It’s not just that Jean Louise, now 26, is as wry and engaging and bold as she was at the age of 6. It’s that through her eyes, and her imperfect but well-meaning attempts to interpret the fall of her hero, the book offers what’s become increasingly difficult and necessary in the five decades since Mockingbird was published: an unflinching attempt to wrestle with racial prejudice.

In the opening chapter, Jean Louise, tomboyish and incisive as ever, is returning home to Alabama for a two-week vacation, immensely happy to be back, but with a sense of foreboding—“an ancient fear”—that something is wrong. Atticus, sketched only briefly in the first few chapters as a gruff but straight-talking figure who occasionally gets “an unmistakable profane glint” in his eyes, is happy to have her home, but soon raises an unexpected question. “Jean Louise,” he asks. “How much of what’s going on down here gets into the newspapers?”

Through Jean Louise’s eyes, and her imperfect but well-meaning attempts to interpret the fall of her hero, the book offers an unflinching attempt to wrestle with racial prejudice.This sense of anxiety lingers through the first half of the novel, with Jean Louise aware that something has shifted in her hometown, and her family and friends vaguely edgy in deference to her new status as an outsider. Eventually, sneaking into a Maycomb County Citizen’s Council meeting at the courthouse in much the same way she snuck into Tom Robinson’s trial in Mockingbird, she witnesses her father and her prospective fiancé, Henry, flanking a speaker named Grady O’Hanlon as he addresses the assembled group. O’Hanlon, Jean Louise observes, “had quit his job to devote his full time to the preservation of segregation. Well, some people had strange fancies.” Her characteristically dry dismissal turns into appalled revulsion when he starts to speak.

Mr O’Hanlon was born and bred in the South, went to school there, married a Southern lady, lived all his life there, and his main interest today was to uphold the Southern Way of Life and no niggers and no Supreme Court was going to tell him or anybody else what to do … a race as hammer headed as … essential inferiority …kinky woolly heads … still in the trees … greasy smelly … marry your daughters … mongrelize the races … mongrelize …. mongrelize.

This ugliness, this raw hatred, is what has happened while Jean Louise has been away, and the realization makes her physically sick. “The one human she had ever fully and wholeheartedly trusted had failed her;” Lee writes, “the only man she had ever known to whom she could point and say with expert knowledge, ‘He is a gentleman, in his heart he is a gentleman,’ had betrayed her, publicly, grossly, and shamelessly.”

In some ways, Watchman is structured like a mystery novel, with the decanonization and subsequent autopsy of Atticus Finch as the central conundrum around which the story unfolds—a story that turns out to be about Jean Louise’s struggle to fathom her own racial (and other) views, not just her father’s. One of the great strengths of Mockingbird is its narrative voice, which captures both the innocence of six-year-old Scout and the wisdom of an elder Jean Louise. In Watchman, Jean Louise comes off like a self-deprecating cross between Dorothy Parker and Nancy Drew, and in the mix of caustic wit and earnest zeal, her level of self-awareness can be hard to gauge. Whether or not that’s entirely intentional on Lee’s part, the result is a vivid rawness as Jean Louise veers between the principled outrage of the outsider and an insider’s visceral reflexes. “Mercy, what do they think they’re doing?” the bold defender of racial equality blurts out early on to Henry, her prospective fiancé, when “a carful of Negroes” drives by.

In her quest to discover what might have happened to Atticus, Jean Louise gets a broad dose of local sentiment, spending time with her Uncle Jack and a gaggle of Maycomb ladies, and paying a visit to Calpurnia, the black maid who helped raise her, who delivers the biggest jolt of all. Jean Louise finds the elderly woman “sitting with a haughty dignity that appeared on state occasions, and with it appeared erratic grammar.” Calpurnia, Jean Louise recognizes instantly, is “wearing her company manners.” Cal, she cries, “Cal, Cal, Cal, what are you doing to me? What’s the matter? I’m your baby, have you forgotten me? Why are you shutting me out?”

“What are you all doing to us?” is Calpurnia’s response.

Jean Louise’s consternation at the sudden change in relations between white and black people in Maycomb is heartfelt, but no less selfish for its genuine pain. When Scout asks how the world works, her curiosity is admirable, but when Jean Louise does the same, she can seem more naively blinkered than she realizes, and her own prejudices emerge in fleeting glimpses throughout the novel. The black folks she knew “were poor, they were diseased and dirty, some were lazy and shiftless,” Jean Louise unselfconsciously reflects, “but never in my life was I given the idea that I should despise one, should fear one, should be discourteous to one, or think that I could mistreat one and get away with it … That is the way I was raised, by a black woman and a white man.” A chasm looms, even as she proclaims her empathy.

Maybe Watchman really was a sequel—a follow-up by one who learned more about the prospects of post-racial progress than she’d hoped to.Jean Louise manages a more nuanced perspective when she steps back to make sense of the regional political sentiments that have shaped her and that seem to animate the father she can no longer begin to comprehend. Both she and Atticus refer at various points to an unnamed Supreme Court decision—presumably Brown v. Board of Education—and she’s half-surprised to find herself sharing his anger at the trampling of states’ rights. Yet she endorses the decision, and delivers an insightful mini-lecture on Southern complicity in hastening federal intervention. “We missed the boat, Atticus,” she says. “We sat back and let the N.A.A.C.P. come in because we were so furious at what we knew the court was going to do, so furious at what it did, we naturally started shouting nigger.”