Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 391

July 14, 2015

The Camera Behind the New Pluto Photos

For decades after its discovery in 1930, Pluto looked like nothing more than a gray smudge in the abyss of space. We knew it was there—even knew its size and gravity—but, without better images, we could not answer seemingly basic questions about it. Was it pocked by craters? What was its atmosphere like?

Our understanding of the orb has slowly improved (with the Hubble Space Telescope’s help), but this week it takes a cosmic step forward. On Tuesday morning, NASA’s New Horizons probe zipped by Pluto and its dwarf moon, Charon. After a nine-year journey from Earth, New Horizons took hundreds of images in mere hours on Tuesday—images that will fill textbooks and museum exhibits for decades, as well as help scientists figure out how our solar system came to support life.

There are three cameras aboard New Horizons.

I talked to Lisa Hardaway, an engineer at Ball Aerospace in Colorado who led technical development of the one called “Ralph.” Ralph captures visible and some infrared light. When you see Pluto looking tan- and sepia-toned in the new, high-resolution photos, you’re looking at data captured by Ralph.

Since it captures visible light, Ralph is in many ways comparable to the camera found in a phone or fancy DSLR. In conventional camera terms, it’s a 75mm lens at f/8.7. But it was far harder to built than a normal camera. Hardaway says that the team was working under a number of big constraints.

Many of them came down to this: “We were cruising for nine and a half years,” Hardaway told me. “So our system would have to handle the space environment, specifically radiation and thermal fluctuation, for nine and a half years.”

Objects in space are often designed to be bombarded by the cosmic rays. But a probe like New Horizons traveling as far out as the outer solar system would be tested by the environment in other ways, for the farther something gets from the sun, the colder space becomes.

The highest-resolution photo of Pluto ever, captured by the New Horizons probe this week (NASA)

The highest-resolution photo of Pluto ever, captured by the New Horizons probe this week (NASA) “Going out that far, there are some fluctuations,” Hardaway says. “It can get quite cold, and materials will shrink as they get colder. But different materials shrink at different rates.”

The answer, then, was to build almost the entire camera out of just one type of material.

“We actually built the mirrors and the chassis out of aluminum so that as they shrink, they would shrink together, to maintain the same focal length. We could do a reasonable test on Earth and still expect the same quality image,” she says.

Even the camera’s mirrors were made out of aluminum. (To turn dull aluminum into mirrors, Ball sharpened it with diamonds.) The lens was one of the few pieces of the camera that could be safely made out of glass.

Another constraint on the mission was that Ralph had to take photos using only the sun’s dim light that reaches Pluto. During its flyby, New Horizons will photograph the side of Pluto that’s turned away from the sun. This side is lit solely by the sun’s light reflecting off Charon. This is like taking a photo using just the light from a “quarter moon” on Earth, a lead optical engineer for the mission told me in an email.

So Hardaway and her team designed Ralph for the exact light conditions that New Horizons would have to operate in. “This camera isn’t adjustable. It’s designed very specifically for conditions at Pluto,” she says.

“In a standard camera, whether it’s digital or analog, you have to adjust the aperture size and change the f-stop reading so that you can get the most out of the light available. When we used to have film camera, it would go to a primary speed of film, like 400 or 800,” she told me.

“We don’t have any of those options,” she says. “We had to get it so that the detectors could take a minimal amount of photons and turn it into an image.”

That made Ralph unusually susceptible to very bright light, which required its own precautions.

“We actually had to put a cover on it for launch, because once it separated from the ferrying of the rocket, if you got a glimpse of the sun, or the sun reflected in the moon or Earth, you could saturate the detector and potentially destroy it. We didn’t open the aperture till we were closer to Mars,” she says.

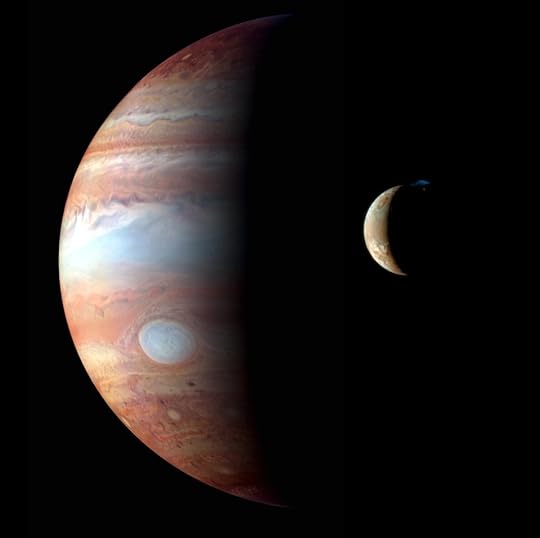

Once opened, though, the devices began snapping pictures. Passing Jupiter in 2007, about 20 months after its launch, New Horizons captured this photo of Jupiter and its moon, Io:

NASA

NASA Hardaway says that, though difficult, her team could devise solutions to space’s frigidity and Pluto’s relative dimness. Once these problems had been solved too, they stayed that way.

It was far harder to work under the two most important constraints on the mission: mass and power. Ralph needed to be light, and it needed to use very little power.

“We were given a requirement we could use, but they asked us to be even better,” Hardaway says. Any mass not used by Ralph could be used to store fuel. And any power not required by the device could be directed toward steering the probe to new subjects, beyond Pluto. Together, this conservation of weight and power could potentially extend New Horizon’s usefulness to researchers by years.

“I knew [NASA] really, really wanted to get as much fuel onboard as possible, and even though we met our original requirements, we really wanted to do better, as good as we could do,” she said.

They did. Ralph went on New Horizons weighing about 23 pounds, below NASA’s requirements. It uses seven watts of electricity, about as much as “the power of a standard night light,” according to Ball.

It was also developed much faster than Ball would prefer. Hardaway says that normally teams hope to have 36 months to design, build, and test a new optical device, but Ralph was completed in just 22 months. That timescale pales to how long it took the camera to actually reach Pluto—almost 113 months—and how long it will have to study the dwarf planet up close—only a couple days.

Next, the probe will turn toward other objects in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of rocky asteroids and dwarf planets beyond Neptune. It will take years to reach them—but at least it will have enough fuel.

And, for now, scientists are celebrating what they have accomplished.

“Up until now, Pluto was just a point of light. Many times you couldn't even separate Pluto from its large moon Charon,” says Cathy Olkin, a planetary scientist and one of the principal investigators with New Horizons. “From Earth, there was just one pixel of Pluto… I’ve been just thrilled to see these images come down.”

Adrienne LaFrance contributed reporting.

The Iran Deal Upends U.S. Politics

The Iran nuclear deal upends the security of the Middle East region. Old alliances have been shoved aside. Massive new resources have been put at the disposal of the Iranian regime. The security implications of the agreement will take time to be felt. The U.S. political consequences will be immediate.

Here are five:

The Rand Paul Candidacy for the Republican Nomination Is Over

The Iran deal presents Republicans with a sharp binary choice. Line up with President Obama in support of a treaty achieved mostly by American concessions that puts Iran on the path to an internationally accepted nuclear weapon sometime in the 2020s? A treaty that bypasses Congress’ role and that is opposed by every U.S. ally in the region, including but not limited to Israel? No cash prize for predicting how the Republican primary electorate will align.

In the middle of Obama’s tenure, Rand Paul achieved for himself a standing within the GOP that eluded his father by focusing less on international security and much more on domestic surveillance. So long as as Congress was debating NSA and TSA, rather than Russia and Iran, Paul found a considerable constituency inside the party for his distinctive ideology. Now the spotlight shifts to Iran, Russia, and nuclear proliferation. Paul will either find himself isolated with the old Ron Paul constituency—or he’ll have to find some nimble way to jump to the “anti” side of the Iran deal. (Perhaps he will emphasize the slight to Congress it represents?) If he opts for the latter approach, however, he becomes just another Republican voice among many competing to voice their opposition, and one less powerful and credible than, for example, Ted Cruz will be.

Related Story

Tough Is Back

The Republican candidates for president don’t disagree much on policy, but they diverge greatly in tone. Jeb Bush is conciliatory, Marco Rubio is inspirational, and Scott Walker is tough. “Tough" is about to become the most important quality for a Republican nominee.

Republicans won’t reject the Iran treaty because they want war with Iran. They will reject the treaty because they believe that a less feckless negotiating team—and a team more confident of American purposes and power—would have secured a less abject deal. Candidates will be judged according to how strong they seem. Candidates who have shown weakness in past negotiations—as many Republicans feel Rubio did when he negotiated with Chuck Schumer over the “Gang of Eight” immigration deal—will pay a penalty.

Hillary Clinton Will Discover That Incumbency Also Has Disadvantages

To date, Clinton has benefited hugely from running to succeed a president of her own party. She’s acceptable to almost all factions of a united party. She’s been permitted to avoid taking stands on divisive issues. She’s been buoyed by a rising economy. Now she’s about to experience a disadvantage: She’s about to be held politically responsible for somebody else’s decisions.

At first that disadvantage shouldn’t be too painful. Democrats will mostly support the Iran deal, if not for reasons of ideology (“negotiation is always better than confrontation”), then out of loyalty to Obama. Over the 16 months between now and the election, however, Iran will have many, many opportunities to remind even Democrats of the downsides of this deal—starting with the aid about to flow to every Iranian-backed terrorist and thug regime in the region and the world. The presumptive next leader of the party that sent those funds flowing will have to justify and defend an agreement that almost certainly will look even more one-sided in 2016 than it looks today. And she will have to defend it, or else risk dividing her party over the next consequence in the series:

Liberals Will Be Energized

The heyday of liberal activism and organization was the second Bush administration, when Democrats as conservative on domestic issues as Howard Dean and Wesley Clark could work with MoveOn.org in opposition to the Iraq war. As the Iraq issue faded, so did liberal activism. Groups like Occupy Wall Street tried to revive the old spirit, but they lacked a clear agenda—and anyway looked too radical and generally odd for the mainstream of their party.

Only last month, centrist Democrats handed liberal Democrats yet another indignity: defeat on the trans-Pacific trade deal. Aside from parking their votes with Bernie Sanders, liberals could do little but grumble. Now suddenly comes an issue that liberals will care about a lot more than they ever cared about trade. This issue even offers an individual to demonize: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The Democratic base has turned increasingly hostile to Israel. Democratic elites have been more cautious. The debate over the Iran deal will unify both over an issue that promises peace while also conveniently rebuking Netanyahu and isolating Israel. Democratic elites can reassure themselves that the isolation of Israel is an unfortunate side effect of the deal; the Democratic base can straightforwardly enjoy it—and all can come together over an issue that probably won’t too badly alienate undecided voters, unlike such previous liberal causes as reducing incarceration or extending amnesty to undocumented immigrants.

Elites Will Matter

Over the past decade and a half, just about every bright idea recommended by one set or another of America’s financial, political, and national security elites has disappointed, if it has not failed outright. From the dot-com boom to the Iraq war to the stimulus, the people who claimed to know what they were talking about have been found wanting by voters and taxpayers. Trust in institutions, as measured by polls, has tumbled and then tumbled again. The Twilight of the Elites, to borrow the apt title of a book by Chris Hayes, and MSNBC host, made possible a new dawn for populists and demagogues.

But that was then. When we’re talking about nuclear proliferation and inspection, about centrifuges and enrichment levels, almost all of us must depend on the expertise of professionals in the field. Donald Trump may drown out George Borjas on immigration, but when the topic shifts to the weapons potential of uranium, it’s David Albright whom the TV cameras will seek.

Let’s hope that this time, the elites prove more worthy of the public trust.

The Man Who Helped Make Harper Lee

The day the news broke of the forthcoming publication of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, I made a note to mention it to my grandmother, with whom I’m in the habit of discussing literary affairs. I was expecting some talk of how she remembered the civil rights movement, of Southern fiction, and of other authors who’d played Rip Van Winkle. But her response this time included a surprise.

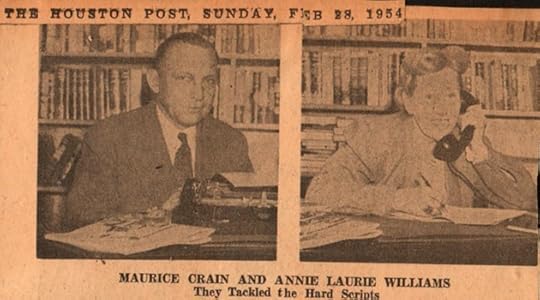

Harper Lee, she said, had shared not only a publisher but a literary agent with my grandfather, Bonner McMillion, a newspaperman and novelist of some modest success in the 1950s and 1960s. I had never before known of Bonner’s connection to Lee (such as it was) because it had never occurred to me that there had been any practicalities to his career: Though not of lasting national note, to me my grandfather’s work had mythic significance. Over the next few weeks I interrogated my grandmother, Virginia, once a reporter herself and still undiminished in mind at 93, about the agent in question, Maurice Crain—who had apparently once mentioned a story of Lee’s that he’d suggested she expand into a novel.

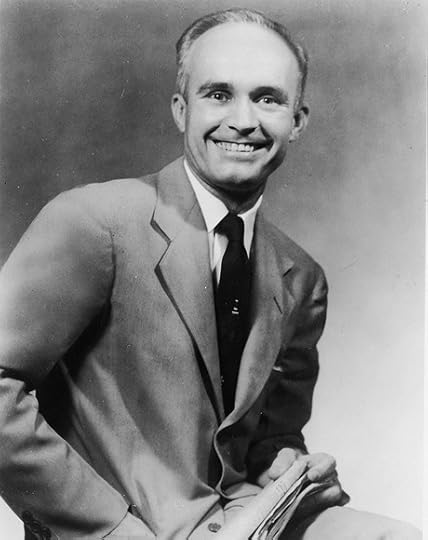

Bonner McMillion (Ari N. Schulman)

Bonner McMillion (Ari N. Schulman) Finally I thought to ask where this conversation had taken place. Probably, she said, via their correspondence, which Bonner had kept, meticulously organized, in his filing cabinet. Sure enough, wedged between old phone bills, I found a folder with sixteen years of Crain’s letters, neatly bound and ordered from their start in the early fifties. The sheets let off the gentle musk of period hardcovers, and were still dimpled, like braille, from the imprint of typewriter keys long ago. Most simply involve the rote business matters of writer and agent. But scattered in between is a wealth of information about the publishing industry of fifty years ago, its economics, its major players, its literary trends, and the famous acquaintances of Crain’s, whose mention he saw fit to sprinkle in at opportune moments.

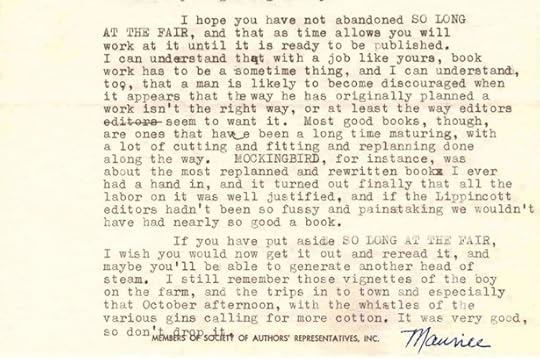

One letter, from January 1962, even revealed details about the crafting of To Kill a Mockingbird, Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, and until this month, her only published book:

Most good books are ones that have been a long time maturing, with a lot of cutting and fitting and replanning done along the way. MOCKINGBIRD, for instance, was about the most replanned and rewritten book I ever had a hand in, and it turned out finally that all the labor on it was well justified, and if the Lippincott editors hadn’t been so fussy and painstaking we wouldn’t have had nearly so good a book.

Crain’s relationship with Lee has long been a subject of interest among those who research the reclusive author. In his 2006 biography of Lee, Charles J. Shields writes of a mentor relationship between the two that eventually grew into a deep friendship. Shields’s work, since expanded by the Washington Post’s investigative report on Watchman, shows that Lee and Crain’s working relationship began in late 1956, when she gave him five short stories. Crain found one, “Snow-on-the-Mountain,” promising, but returned the others, suggesting she consider writing a novel, which would be easier to sell. In January, Lee delivered an additional story and “the first fifty pages of a novel, Go Set a Watchman.”

The growing consensus has long been that Mockingbird was reworked from Watchman, and with reason. HarperCollins published Go Set a Watchman on July 14, and in February one of their representatives said, “there will not be any editing to the book, as it is not necessary.” (It remains unclear whether Lee’s editors at HarperCollins have had any direct contact with her since she suffered a stroke in 2007.) But as I learned through my grandfather’s correspondence with Crain, To Kill a Mockingbird was nevertheless the product of considerable encouragement, advice, and revision, much of it coming from a man who saw it as his mission to champion writers like Lee and Bonner, whose deceptively gentle small-town stories were rapidly falling out of fashion.

Ari N. Schulman

Ari N. Schulman * * *

I recall my grandfather once expressing frustration at “spigot writers”—those who could just open the tap—even though he wrote one of his books in just three months, because, as he put it, “we were hungry.” But this was just part of the lore. As a kid in Houston, I’d had a friend whose grandfather had been to the moon (twice!), but I remained more in awe of the feats of my own. Writing novels was a great—and, at least for those already written, obviously preordained—business.

Here in his letters these feats are brought to earth, with all their struggles and contingencies—a career’s worth between two manila folds. Part of the charm in reading them stems from discovering how little the publishing biz has changed—push and tug, bitter pills of criticism delivered with sugar of flattery—as well as how readily the patter of 1950s speech smoothed these exchanges for two men who were far from rubes.

Related Story

Harper Lee: The Sadness of a Sequel

They bonded over their military service: Bonner had served as a cryptographer in North Africa, Crain as a gunner, and later a German prisoner of war. They came from similar backgrounds, too, as did Annie Laurie Williams, Crain’s wife, who partnered with him to handle movie and TV adaptations. All three were raised in Texas farming and ranching towns in the prosperous lull between the closing of the frontier and the Depression.

In the letters, Crain affects a certain air to which Southerners are prone, the more so around each other and in the presence of Northerners. He consoles Bonner for “slaving over a hot typewriter for less than peanuts.” He offers advice handed to him by “my Granddad, a field officer of some experience in Gen. Lee’s army.” He warns that a plotline involving an extramarital affair “never, never, never happens in the immaculate columns of a Curtis publication.” And, rejecting an early novel, Crain writes, “Remember the Holy Trinity of English I, Unity, Coherence, and Emphasis? Well, for the lack of the nail Unity, the horses Coherence and Emphasis both threw a shoe and limped home lame.”

Though Crain made his business in Midtown Manhattan, he of course refers to Northerner publishers as Yankees. The New Yorker and Harper’s are “lit’ry” mags—“pretentiously lit’ry.” Apologizing for what he considered an insulting price offered by Collier’s magazine to serialize Bonner’s first novel, Crain says, “we’ll take it out of their hides in the future.” Aiming to lower expectations for Bonner’s football novel, The Long Ride Home, Crain says that reviewers don’t like sports fiction because they’re “mama’s boys who grew up to be grinds and have a buried resentment” of strong men such as me and thee.

Not far into the correspondence, Crain has established himself as co-conspirator.

* * *

By the time the correspondence begins in 1952, Crain and Williams had been in business for nearly two decades, and could count representation of John Steinbeck and Margaret Mitchell among the feathers in their cap. In Charles Shields’s biography of Lee, Williams comes across like Holly Hunter playing Stevie Grant, unctuous and intimidating even to her clients—an impression Bonner conveyed to my grandmother too, though more lightly.

Ari N. Schulman

Ari N. Schulman Bonner kept her letters as well. Far fewer than Crain’s, they convey nothing but sweetness. Many of her notes are postscripts jammed onto Crain’s letters, urging my grandfather to bring the family out to their Connecticut summer home. They never took up the offer, though Harper Lee did.

Crain did visit my grandparents, in late 1956—right around the time he met Lee—seemingly during a Christmas visit home to Texas. Shields describes Crain as athletic, fastidious, and chain-smoking. My grandmother recalls him as neatly dressed, businesslike, and unjocular. He sat in their study, reading the manuscript for Bonner’s latest novel.

“I had been told by Bonner to be sure and have whiskey,” she writes, “and I had a fifth of something good but Maurice read and drank steadily for hour after hour and the fifth was empty. I ran across the street to a neighbor and asked for whiskey and she gave me another fifth.” Over dinner, the conversation hewed closely to commentary on the manuscript, and Crain switched to beer.

Crain seemed to view his role not just as an agent of literary goods, but a steward of literary real estate, cultivating works over the long term and sometimes incurring damage over the short. In 1953, urging Bonner to abandon his first effort, Crain writes:

I know how deeply a writer can become attached to a first novel, particularly if at times he realizes that he was writing with power … I have known stubborn one-book writers who kept tinkering with the same engine that refused to start for all of their working lives. It is a sad waste of hope and man-hours.

Three years later, after the football novel The Long Ride Home defied expectations by reaching more than a niche market—serialization in Collier’s, a spot in the Reader’s Digest condensed books, a TV-movie adaptation—Crain says Bonner has arrived at a point in his career where he should avoid down-market publications, writing, “Next to talent itself, reputation in time becomes a writer’s chief capital.”

Crain compares first drafts to ore, saying, “If we are to be of value to you, we must report faithfully what the assay shows.” But a mine doesn’t feel the sting of its low estimation, and so ego management was clearly central to his mandate. Sometimes brutal criticism is tempered immediately by warm praise. When Bonner’s first book barely remakes its advance, Crain shrugs, “It happened to Sinclair Lewis.”

A similar principle held for publishers: “I feel that it is very well done but not quite the kind of thing we want,” said an editor at the New American Library, in what would become a refrain of the letters. But the most artful rejection came from Crain himself, declining to sell a short story: “Keep it among your souvenirs … for the eventual collection.”

* * *

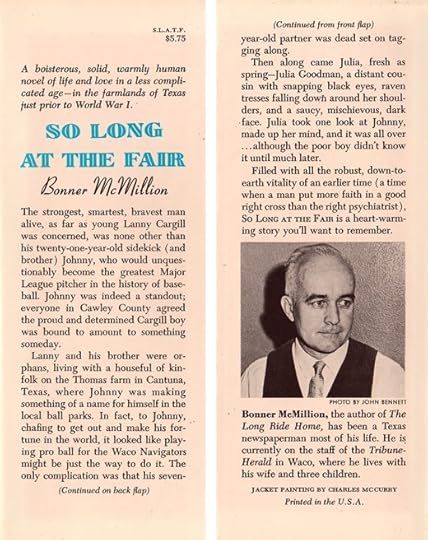

The question that most interested me in the correspondence regarded the failure of my grandfather’s last book, So Long at the Fair (1964): to my mind, his most mature and “lit’ry” work. The story in my family is that the problem was timing. The novel was a wistful look at small-town life, set in the placid Texas landscape just before World War I, that arrived as the nation was entering a violent and broody mood.

Ari N. Schulman

Ari N. Schulman On the day of the Kennedy assassination, Bonner, then a reporter for the Waco Tribune-Herald, learned the news via wire reports, whose grim progression he later recounted to me. When he arrived home, my grandmother, almost as an afterthought, handed him a letter that had arrived that day. He opened it to read that Doubleday had accepted his book for publication.

By the time the book was released a year later, it still seemed like an afterthought. The New York Times, which had given Bonner’s first book a lengthy and mainly laudatory review, dropped only a short blurb. A barely restrained panic ensued between Bonner and Crain over reports that Doubleday had failed to get the book distributed to sellers in time to meet the initial demand.

My grandmother recalls an anemic marketing effort. The book’s packaging, for its part, is maudlin. The tagline, A novel about people who are the salt of the earth, mistakes the setting for the story. The jacket blurb induces even deeper yawns, billing it as a “heart-warming story” of “a less complicated age” when “a man put more faith in a good right cross than the right psychiatrist.”

But these characters are far from simple, and very far from pure. This, after all, is a book that opens with its narrator, 8-year-old Lanny, being mock-seduced by his 10-years-older cousin, Julia. Only, Lanny is too green to be in on the joke, which, it turns out, has a not entirely innocent purpose. The chapter ends with Julia planting on Lanny’s mouth what he recalls as “no cousin’s kiss,” whereupon he “yelled like I’d been bitten and fled in terror from the room.”

Ari N. Schulman

Ari N. Schulman You wouldn’t know it from the cover, but the book is shot through with innuendo. The main literary appeal of the book is not the world it shows us but the window onto it: Lanny, a scamp who fancies himself a grown-up but doesn’t grasp the many adult scenes and conversations he witnesses, and thus lends a peculiar charm to the telling.

This device, in fact, is one of several similarities between my grandfather’s book and To Kill a Mockingbird. Both are coming-of-age stories of feisty children, set in the South of the early century. In both, the regionalisms and small-town charm belie rumbles in the distance from shifting cultural winds—civil rights in one, suffrage and feminism in the other.

The books had some similarities in their narrative development, too: Both started out as split adult-child narratives. In a letter dated January 14, 1957—the same day that Lee dropped off the first pages of Go Set a Watchman—Crain advises Bonner to focus on the adult’s perspective, the opposite of the advice he’d give Lee a short while later. In the end, both books used only the child’s timeline. But Mockingbird also includes Scout’s adult voice, and much of that book’s power comes from placing a child amongst the workings-out of peculiarly adult forms of hatred, heroism, and grace.

* * *

The correspondence peters out after the publication of So Long at the Fair, until the last letter, dated 1968, two years before Crain’s death:

SO LONG AT THE FAIR keeps troubling me. It remains the only book I have ever loved with a passion which was not similarly loved by a large public. I am still unwilling to believe that it wasn’t as good as I always thought it was.

Once, long before, Crain had written to Bonner, “You are one of maybe two or three hundred young novelists out of whom our literary big guns of the next decade are going to come.” My grandfather continued to labor over two novels that remained unfinished when he died last year, Crain’s prediction having never come to pass.

Bonner never spoke of his work, and my family rarely asked him about it. He was such a gifted mimic and storyteller that our requests were always for the true stories, with characters he’d been granted uncanny powers to bring back to life.

Sitting quietly with him one evening years ago, he asked me, unprompted, “What is your goal as a writer?” It caught me by surprise—by this time his mind had begun to go, and I didn’t know if he knew I was a writer at all, or trying to be, anyway. I fumbled for an answer then, only later wishing I’d returned the question.

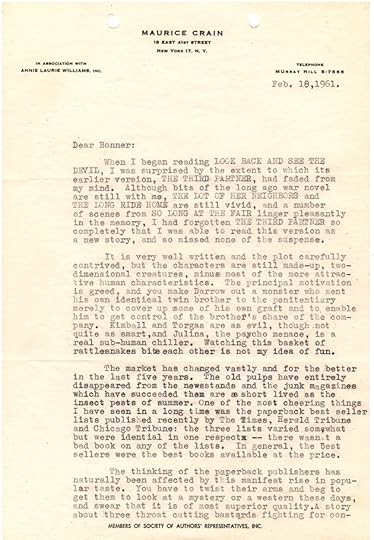

As for Bonner, perhaps a hint of an answer for him lies between the lines of another of Crain's letters, this one from February 1961. Crain, writing from before the darker turn of the mid-sixties, rejects a "brutal and unpleasant" crime story Bonner had sent. Trying to assuage his feelings and push him back towards something more redemptive, Crain cites the burgeoning success of another book he'd recently nudged in the same direction.

I think it is closer to your kind of book than any other that comes to mind. The book is TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD by Harper Lee and I am proud of it[ ]because I handled it from the time it was a short story and a gleam in the author’s eye. She has the same ability you have to create living characters, from kids to old folks, so real that people from totally different environments immediately believe in them, the ability to recall childhood scenes and moods with complete clarity, the same gentle underlying humor which adds charm to the telling. I remember telling her, when trying to persuade her to go on and keep working at the Mockingbird, how well you had succeeded with similar material. I remember showing her that section of SO LONG AT THE FAIR where the boy is listening to the sounds of the gin whistles, near and distant, and how much she loved it.

The Single Most Important Question to Ask About the Iran Deal

“Look, 20 years from now, I’m still going to be around, God willing. If Iran has a nuclear weapon, it’s my name on this.” – President Barack Obama, May 21, 2015

The theocratic regime that rules Iran—a regime that is a committed and proficient sponsor of terrorism, according to John Kerry’s State Department—will be more powerful tomorrow than it is today, thanks to the agreement it has just negotiated with the Obama administration, America’s European allies, and two U.S. adversaries as well.

This sad conclusion is unavoidable. The lifting of crippling sanctions, which will come about as part of the nuclear deal struck in Vienna, means that at least $150 billion, a sum Barack Obama first invoked in May, will soon enough flow to Tehran. With this very large pot of money, the regime will be able to fund both domestic works and foreign adventures in Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Iraq, and elsewhere.

It is hard to imagine a scenario—at least in the short term—in which Hezbollah and other terror organizations on the Iranian payroll don’t see a windfall from the agreement. This is a bad development in particular for the people of Syria. Iran, as the Assad regime’s funder, protector, and supplier of weapons, foot soldiers, and strategists, is playing a crucial role in the destruction of Syria. Now Syrians will see their oppressor become wealthier and gain international legitimacy (legitimacy not just for Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, which this deal will leave in place). Here is a bit of what the State Department says about Iran’s role in what might be the world’s most awful war: “In 2014, Iran continued to provide arms, financing, training, and the facilitation of primarily Iraqi Shia and Afghan fighters to support the Asad regime’s brutal crackdown that has resulted in the deaths of at least 191,000 people in Syria.”

Related Story

‘Look ... It’s My Name on This’: Obama Defends the Iran Nuclear Deal

And yet the deal, though representing a morally dubious compromise with a terror-supporting theocracy, might be, from the perspective of U.S. national security, a practical necessity. I’m writing this just as the deal is being announced, and I think it is dangerous to make sweeping judgments about a complicated document I’ve only skimmed. (And, of course, there will be plenty of time in Washington over the next 60 days for sweeping judgments!) But here is the most important question to ask going forward: Does this deal significantly reduce the chance that Iran could, in the foreseeable future (20 years is the time period Obama mentioned in an interview with me in May), continue its nefarious activities under the protection of a nuclear umbrella? If the answer to this question is yes, then a deal, in theory, is worth supporting.

I have no doubt that this deal isn’t perfect. I’m worried, in particular, about the issue of intrusive inspections: How much visibility will the International Atomic Energy Agency (and, by the way, the CIA and other Western intelligence agencies) have into the Iranian nuclear program? How quickly will inspectors be able to visit sites they want to visit? I’m also worried about the time-based, rather than condition-based, lifting of arms embargoes (the United States should never acquiesce to a flow of arms to a terror-sponsoring state), and about Iran’s ability to continue its research and development on ballistic missiles and other aspects of a nuclear program. I also believe that so-called “snapback” sanctions are a fiction: The U.S. could reimpose sanctions on Iran if Tehran cheats on the deal, but it would be reimposing these sanctions on what will be a much-richer country, one that could withstand such sanctions for quite a while.

I wish I could believe what Obama seems to suspect: that this deal will set in motion a virtuous cycle in which moderates gain power in a liberalizing Iran.Snapback is actually a person, not a mechanism. The 45th president of the United States will be America’s snapback. The Iranians will not find the next president to be as accommodating as the current president (unless, of course, Rand Paul wins the general election). All of today’s frontrunners—Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, Scott Walker, and Hillary Clinton—would, as president, be watching Iranian behavior with jaundiced eyes. I don’t doubt that Hillary Clinton will support the current deal, but I also don’t doubt that she would push back hard against Iranian cheating, or Iranian adventurism, if she becomes president. (“I’ve always been in the camp that held that they did not have a right to enrichment,” she told me last year. “Contrary to their claim, there is no such thing as a right to enrich. This is absolutely unfounded.”)

The Iran drama is only beginning. Assuming that Obama can sell this deal to Congress—Chuck Schumer, a nation turns its lonely eyes to you—this will be a multi-year story of implementation. I wish I could believe what Obama seems to suspect, that this deal will set in motion a virtuous cycle in which moderates (relative moderates, of course) gain power in a liberalizing Iran. But I don’t think that this is happening soon. For now, I hope that Obama will study the reality of Iranian activity in the region, and begin to push back against Iran’s ambitions with more alacrity than he has done so far.

I mentioned Syria earlier as an example of a country that could suffer under this agreement. Other Arab states are, of course, under threat from an empowered, better-funded Iran. One country that I think could conceivably—conceivably—benefit from this deal is Israel. It will face acute conventional challenges from Hezbollah, Iran’s Lebanese proxy, but Hezbollah will be operating, for the time being at least, without the protection of an Iranian nuclear umbrella. If the plausible case can be made that this deal actually pushes Iran further away from the nuclear threshold—and we’ll have time, over the next 60 days, to test this case—then Israel will be better off with this deal than it would be without it. Unlike many proponents of this deal, I take the Iranian regime’s threats to exterminate Israel seriously. (I’m not sure, based on my last conversation with Obama, that he fully understands the depth of the regime’s anti-Semitism, in part because the regime’s anti-Semitism is so absurdly offensive and illogical that the hyper-rational Obama might not believe that serious people actually think the way certain Iranians think.)

If the agreement pushes Iran further away from the nuclear threshold, then Israel will be better off with this deal than without it.If I thought that preventative war—air strikes against Iran’s three or four most important nuclear facilities—could have led to the permanent de-nuclearization of this anti-Semitic terror state, I might have considered supporting such a notion. But I suspect that war would have only accelerated Iran’s push for a bomb. Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, played an absolutely crucial role in motivating the world, and the Obama administration, to oppose Iran’s nuclear ambitions. But he has become an impotent player in this drama in part because he seeks a perfect solution to the Iranian challenge. There is no perfect solution.

I worry that Obama’s negotiators might have given away too much to the Iranians. On the other hand, Netanyahu’s dream—of total Iranian capitulation—was never going to become a reality. The dirty little secret of this whole story is that it is very difficult to stop a large nation that possesses both natural resources and human talent, and a deep desire for power, from getting the bomb. We’ll see, in the coming days, if Obama and Kerry have devised an effective mechanism to keep Iran far away from the nuclear threshold.

What's in the Iran Deal?

Updated at 1:31 p.m.

On Tuesday, following nearly two and a half years of negotiations, Iran and six world powers struck a nuclear agreement. Under the accord, “sanctions imposed by the United States, European Union and United Nations will be lifted in return for Iran agreeing long-term curbs on a nuclear program,” Reuters reported. While details of the agreement are still being parsed, this outcome is consistent with the basic parameters of a framework agreement signed between Iran and the six world powers in April in Switzerland.

Background

Although that framework only sketched out the contours of a deal, it was both embraced and derided around the world. My colleague Jeffrey Goldberg called it President Obama’s “least-worst option,” in that it would restrict Iran’s nuclear program over the course of a decade, but also “formalize[d] Iran’s status as a potential nuclear-threshold state by allowing it to maintain a vast nuclear infrastructure.” Western allies of the United States described the deal as a historic breakthrough, while Russia praised it for reflecting President Vladimir Putin’s suggestions. Israel was among the most vocal in its opposition to the framework, calling it a “a very bad deal,” while Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council states were less vocal, but also displeased. Others expressed pessimism that the deal could last. In the United States, many Republicans blasted the framework, while some Democrats were nervous enough about it to vote with their GOP colleagues on a measure that would require Congress to approve any final agreement.

Because negotiations extended past a few initial deadlines, Congress, which goes on recess in August, will have 60 days to review the agreement, 30 days longer than if the deal had come in on time. As negotiations crept to a finish, Republican leaders in the House and Senate reiterated that the deal would be a “tough sell,” although, as my colleague Russell Berman notes, “it won’t be easy for Congress to stop the agreement” because blocking it would require a two-thirds majority. In an interview in The Atlantic earlier this month with Kathy Gilsinan, Farzan Sabet, a visiting fellow in the Department of Government at Georgetown who runs a blog on Iranian politics, explained that opposition to the deal within Iran is also unlikely to scuttle it, because any announced agreement would almost certainly have been approved ahead of time by Ayatollah Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader.

Negotiators failed to meet their deadlines because of thorny issues, such as the potential lifting of a United Nations arms embargo against Iran, a move that the U.S. and others oppose; the timing of sanctions relief, which Iran lobbied to have go into effect immediately; and how much access international observers would have to monitor Iran’s nuclear capabilities.

Speaking from the White House Tuesday morning, President Obama told reporters that the Iran deal is “not built on trust. It is built on verification.”

He also vowed to veto any legislation aimed at undoing it. In Vienna, the European Union’s head of foreign policy, Federica Mogherini, told reporters the accord is “not just a deal, but a good deal, and a good deal for all sides.”

Some in Congress and elsewhere will ultimately disagree with that. We will update this post as new information becomes available.

Reactions

As observers pore over the details of the 150-plus page Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, released by the Russian foreign ministry on Tuesday, they will be looking at what mechanisms the deal has in place to limit Iran’s ability to build up its nuclear program in the long term as well as to ensure it doesn’t cheat on the agreement in the short term.

In an email to The New York Times, Dennis Ross, who formerly oversaw Obama’s Iran policy, focused on the long view, saying that the deal “has clear strengths and weaknesses.”

The strengths are that we definitely buy 10 to 15 years in terms of deferring an Iranian nuclear weapon. The main weaknesses are that Iran will be a nuclear threshold state at year 15 and the gap between that and nuclear weapons will be small.

The sniping over the deal began quickly, as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the agreement a “mistake of historic proportions.” Iranian President Hassan Rouhani seemed to respond on Twitter, warning Iran’s neighbors, “Do not be deceived by the propaganda of the warmongering Zionist regime.” House Speaker John Boehner also condemned the deal, saying that it “will only embolden Iran.” He added, “Instead of stopping the spread of nuclear weapons in the Middle East, this deal is likely to fuel a nuclear arms race around the world.”

That particular fear, articulated throughout the negotiation process, centers now on Saudi Arabia, which quietly signed a nuclear-cooperation pact with South Korea in March. Others remain skeptical about Saudi Arabia’s ability or intentions to build a nuclear program.

Critics of the deal also point to Iran’s pernicious extracurricular activities, specifically its involvement in regional wars that pit it against the United States and its allies. With sanctions relief perhaps giving Iran access to $150 billion, Iran will be less constrained in playing patron to groups like Hezbollah.

“With this very large pot of money, the regime will be able to fund both domestic works and foreign adventures in Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Iraq, and elsewhere,” Jeffrey Goldberg noted on Tuesday. Adding to that dynamic, the nuclear deal includes a list of military leaders and organizations whose names will be removed from the sanctions roster. That list includes Qasem Soleimani, the head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ elite Quds Force, whom one former CIA official described to The New Yorker’s Dexter Filkins as “the single most powerful operative in the Middle East today” for his role in directing Bashar Assad’s war in Syria and his past efforts to fight American soldiers in Iraq.

Details

One key feature of the deal is that it exchanges sanctions relief for Iran with limits to its fuel stockpile and nuclear-production capacities. Iran will have to remove two-thirds of its installed centrifuges and store them under international supervision. It will also have to reduce its stockpile of enriched uranium by 98 percent for 15 years.

Should Iran fail to hold up its end of the bargain, the agreement arranges for a panel involving all seven countries that participated in the nuclear talks to vote on whether to put sanctions on Iran back in place. A simple majority can approve them, which means that if Iran, China, and Russia vote against the so-called “snapback” of sanctions, they can be overruled.

Meanwhile, the agreement affirms that "under no circumstances will Iran ever seek, develop, or acquire any nuclear weapons." To make sure Iran complies, it also guarantees that the International Atomic Energy Agency will monitor Iran’s nuclear facilities for the next 25 years:

These measures include: a long-term IAEA presence in Iran; IAEA monitoring of uranium ore concentrate produced by Iran from all uranium ore concentrate plants for 25 years; containment and surveillance of centrifuge rotors and bellows for 20 years; use of IAEA approved and certified modern technologies including on-line enrichment measurement and electronic seals; and a reliable mechanism to ensure speedy resolution of IAEA access concerns for 15 years.

As for the United Nations arms embargo against Iran, it will be lifted after five years and restrictions on Iran’s ballistic missiles will be eased after eight years. According to Colum Lynch and Dan de Luce at Foreign Policy, the American concession on this issue, which may alienate some of the president’s allies in Congress, is ultimately what led to Iran to give in on the limits to its nuclear program outlined in the accord. The issue of the arms embargo was initially left out of the April framework agreement.

Another controversial provision of the agreement hinged on what will happen to Arak, a heavy-water reactor in Iran that many fear would allow Iran to develop enough plutonium to make a nuclear weapon. In the president’s statement on the nuclear deal, he said that "Iran will modify the core of its reactor in Arak so that it will not produce weapons-grade plutonium." Iran’s state media framed the provision this way: “Arak Heavy Water Reactor will continue its work and remain intact, to be modernized, and equipped with latest technology.”

Demi Lovato’s ‘Cool for the Summer’: The Next Great Gay Anthem?

On her new single, “Cool for the Summer,” Demi Lovato sounds like she wants to satisfy some bi-curiosity. The former Disney star, current X Factor judge, and recent charts fixture sings about having “a taste for the cherry” and tells a lover “don't be scared ‘cause I'm your body type,” while a big, distorted hook and a battering-ram beat commands all in hearing distance to start touching one another. Obviously, people are offended.

Those people are Katy Perry fans, complaining that the song too closely resembles “I Kissed a Girl,” Perry’s first-ever No. 1 hit. A line like “taste of the cherry,” does, by all rights, recall Perry talking about the “taste of her cherry Chapstick,” but Lovato took to Twitter to defend her new Top 40 contender. “Sounds nothing like it,” she wrote. “And with all the advances we’ve made in the LGBT community… I think more than one female artist can kiss a girl and like it….. ;)”

That winky-face speaks to arguably the biggest thing “Cool for the Summer” and “I Kissed a Girl” have in common, outside of a Max Martin co-writing credit. In both songs, the singer’s same-sex smooching is presented as shenanigans—sneaky, rebellious, unapproved. “It’s not what good girls do, not how they behave,” Perry sang in 2008; “Shh… don’t tell your mother,” Lovato cautions, in fine camp form, now.

Related Story

Pop Culture’s Role in the Gay-Marriage Revolution

But comparing “Cool for the Summer” to “I Kissed a Girl” just highlights how deeply un-gay, and maybe even regressive, Perry’s song was. When Ms. “Ur So Gay” kissed a girl, she made sure to clarify that she liked it … because ChapStick tastes good. The lyrics worked hard to let the listener knows that Perry’s kiss was a onetime, drunken lark, and that she was still definitely totally straight and had a boyfriend. “Ain’t no big deal, it’s innocent,” she sang, which is to say, don’t worry, no sexual desire here!

It was a fun song, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with straight people talking frankly about their occasional un-straight activities—a world where doing so is common is one where queer people aren’t so often seen as icky and weird. But on “I Kissed a Girl,” Perry spent so much energy explaining her chaste motives that it almost seemed fearful, like one big, cutesy declaration of “no homo.” A lot of listeners also accused her of donning lesbianism mostly for the entertainment of straight men, which is the kind of performance that encourages people to think of homosexuality as a silly indulgence or trendy choice.

Lovato’s song, on the other hand, is all about desire. She wants the girl because she wants the girl. Her perspective is that of a newbie, but that doesn’t make her a tourist; when she says “Even if they judge / Fuck it,” she’s going through the same process most every queer person has had to go through. Mostly, though, the song is about pop music’s favorite topic: being attracted to someone hot. “Got my mind on your body / And your body on my mind” she says, rewriting the work of the still occasionally homophobic Snoop Dogg.

Lovato’s song, unlike Katy Perry’s, is all about desire. She wants the girl because she wants the girl.While an increasing number of queer musicians are making awesome music both for niche audiences and popular ones, there still aren’t all that many modern, mainstream hits that explicitly reveal themselves as queer and sexual. “Born This Way” is all self-acceptance politics; most of the chartbusters by openly gay artists like Sam Smith are the ones with gender-neutral pronouns. Little Big Town’s current country hit “Girl Crush” will no doubt invite comparisons to “Cool for the Summer,” but that song uses lesbianism just as a metaphor—the singer wants a woman because that woman has her man.

You could argue that Lovato’s message is too coded to be transgressive, or that it’s a cop-out for her to relegate her same-sex desire to a secret summer fling. Though the actress and model Ruby Rose has said she slept with Lovato, Lovato herself has never publicly identified as anything other than straight (currently she’s dating Wilmer Valderrama). Maybe she’s pandering so as to secure a devoted gay fanbase, like Nick Jonas has been doing lately in various forms of undress. But the fact remains that even though people who are 100 percent straight can jump along to “Cool for the Summer,” for once, it’s not about them.

Why the Iran Deal Makes Obama's Critics So Angry

“Mankind faces a crossroads,” declared Woody Allen. “One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.”

The point is simple: In life, what matters most isn’t how a decision compares to your ideal outcome. It’s how it compares to the alternative at hand.

The same is true for the Iran deal, announced Tuesday between Iran and six world powers. As Congress begins debating the agreement, its opponents have three real alternatives. The first is to kill the deal, and the interim agreement that preceded it, and do nothing else, which means few restraints on Iran’s nuclear program. The second is war. But top American and Israeli officials have warned that military action against Iranian nuclear facilities could ignite a catastrophic regional conflict and would be ineffective, if not counterproductive, in delaying Iran’s path to the bomb. Meir Dagan, who oversaw the Iran file as head of Israel’s external spy agency, the Mossad, from 2002 to 2011, has said an attack “would mean regional war, and in that case you would have given Iran the best possible reason to continue the nuclear program.” Michael Hayden, who ran the CIA under George W. Bush from 2006 to 2009, has warned that an attack would “guarantee that which we are trying to prevent: an Iran that will spare nothing to build a nuclear weapon.”

Related Story

‘Look ... It’s My Name on This’: Obama Defends the Iran Nuclear Deal

Implicitly acknowledging this, most critics of the Iran deal propose a third alternative: increase sanctions in hopes of forcing Iran to make further concessions. But in the short term, the third alternative looks a lot like the first. Whatever its deficiencies, the Iran deal places limits on Iran’s nuclear program and enhances oversight of it. Walk away from the agreement in hopes of getting tougher restrictions and you’re guaranteeing, at least for the time being, that there are barely any restrictions on the program at all.

What’s more, even if Congress passes new sanctions, it’s quite likely that the overall economic pressure on Iran will go down, not up. Most major European and Asian countries have closer economic ties to Iran than does the United States, and thus more domestic pressure to resume them. These countries have abided by international sanctions against Iran, to varying degrees, because the Obama administration convinced their leaders that sanctions were a necessary prelude to a diplomatic deal. If U.S. officials reject a deal, Iran’s historic trading partners will not economically injure themselves indefinitely. Sanctions, declared Britain’s ambassador to the United States in May, have already reached “the high-water mark,” noting that “you would probably see more sanctions erosion” if nuclear talks fail. Germany’s ambassador added that, “If diplomacy fails, then the sanctions regime might unravel.”

The actual alternatives to a deal, in other words, are grim. Which is why critics discuss them as little as possible. The deal “falls apart, and then what happens?” CBS’s John Dickerson asked House Majority Leader John Boehner on Sunday. “No deal is better than a bad deal,” Boehner replied. “And from everything that’s leaked from these negotiations, the administration has backed away from almost all of the guidelines that they set out for themselves.”

In other words, Boehner evaded the question. The only way to determine if a “bad deal” is worse than “no deal” is to consider the latter’s consequences. Which is exactly what Boehner refused to do. Instead, he changed the subject: Rather than comparing the agreement to the actual alternatives, he compared it to the objectives that the Obama administration supposedly outlined at the start of the talks.

After a commercial break, Dickerson interviewed Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, who did the same thing. “We have to remember the goal of these negotiations from the beginning,” Cotton said. “It was to stop Iran from enriching uranium and developing nuclear-weapons capability.”

Again, Dickerson tried to steer the conversation away from American desires and toward real-world alternatives. “You have taken the position that if the United States just … walked away from a bad deal, ratcheted up sanctions, that Iran would buckle and come to the table with more favorable terms,” Dickerson said. But “what about an alternative explanation, which a lot of experts believe, which is that they would say, ‘Forget negotiations, we’re going to race towards a breakout on a nuclear bomb?’”

Cotton’s answer: present a “credible threat of military force” and the Iranians will abandon “their nuclear-weapons capabilities.” The senator never explained why threatening war would make Iran capitulate now, given that the United States and Israel have been making such threats for over a decade. Nor did he address the consequences of a military strike, which former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has said could “prove catastrophic, haunting us for generations.”

Instead, Cotton returned to comparing the nuclear deal to America’s ideal preferences. The Obama administration, he said, should “get back to that original goal of stopping Iran from developing any nuclear-weapons capabilities.”

Whether the current deal represents the abandonment of Barack Obama’s “original goal” is less clear than Cotton suggests. In fact, even before talks with Iran began, Obama infuriated Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his GOP allies by refusing to adopt the red lines they wanted. For instance, notes the Rand Corporation’s Alireza Nader, Obama never declared that Iran could not enrich any uranium, something Cotton incorrectly claims was “the goal of these negotiations from the beginning.”

But let’s assume that Obama, or George W. Bush before him, did outline goals that the current deal doesn’t meet. So what? Those goals are irrelevant, unless Cotton and company have a plausible plan for achieving them by scrapping the existing deal, which they don’t.

When critics focus incessantly on the gap between the present deal and a perfect one, what they’re really doing is blaming Obama for the fact that the United States is not omnipotent. This isn’t surprising given that American omnipotence is the guiding assumption behind contemporary Republican foreign policy. Ask any GOP presidential candidate except Rand Paul what they propose doing about any global hotspot and their answer is the same: be tougher. America must take a harder line against Iran’s nuclear program, against ISIS, against Bashar al-Assad, against Russian intervention in Ukraine and against Chinese ambitions in the South China Sea.

The United States cannot bludgeon Iran into total submission, either economically or militarily. The U.S. tried that in Iraq.If you believe American power is limited, this agenda is absurd. America needs Russian and Chinese support for an Iranian nuclear deal. U.S. officials can’t simultaneously put maximum pressure on both Assad and ISIS, the two main rivals for power in Syria today. They must decide who is the lesser evil. Accepting that American power is limited means prioritizing. It means making concessions to regimes and organizations you don’t like in order to put more pressure on the ones you fear most. That’s what Franklin Roosevelt did when allying with Stalin against Hitler. It’s what Richard Nixon did when he reached out to communist China in order to increase America’s leverage over the U.S.S.R.

And it’s what George W. Bush refused to do after 9/11, when he defined the “war on terror” not merely as a conflict against al-Qaeda but as a license to wage war, or cold war, against every anti-American regime supposedly pursuing weapons of mass destruction. This massive overestimation of American power underlay the war in Iraq, which has taken the lives of a half-million Iraqis and almost 4,500 Americans, and cost the United States over $2 trillion. And it underlay Bush’s refusal to negotiate with Iran, even when Iran made dramatic overtures to the United States. Negotiations, after all, require mutual concessions, which Bush believed were unnecessary; if America just kept flexing its muscles, the logic went, Iran’s regime would collapse.

In 1943, Walter Lippmann wrote that “foreign policy consists in bringing into balance, with a comfortable surplus of power in reserve, the nation’s commitments and the nation’s power.” If your commitments exceed your power, he wrote, your foreign policy is “insolvent.” That aptly describes the situation Obama inherited from Bush.

Obama has certainly made mistakes in the Middle East. But behind his drive for an Iranian nuclear deal is the effort to make American foreign policy “solvent” again by bringing America’s ends into alignment with its means. That means recognizing that the United States cannot bludgeon Iran into total submission, either economically or militarily. The U.S. tried that in Iraq.

It is precisely this recognition that makes the Iran deal so infuriating to Obama’s critics. It codifies the limits of American power. And recognizing the limits of American power also means recognizing the limits of American exceptionalism. It means recognizing that no matter how deeply Americans believe in their country’s unique virtue, the United States is subject to the same restraints that have governed great powers in the past. For the Republican right, that’s a deeply unwelcome realization. For many other Americans, it’s a relief. It’s a sign that, finally, the Bush era in American foreign policy is over.

July 13, 2015

The Legacy of Live Aid, 30 Years Later

On July 13, 1985, Africa became a brand. The image of a starving Ethiopian girl named Birhan Woldu flickered across TV screens as Paul McCartney, David Bowie, and Madonna played beneath a “Feed the World” banner on stages in London and Philadelphia. Live Aid, as the event was known, was attended by almost 175,000 people at both venues, and raised an initial $80 million in aid for the victims of a horrific famine. But the 16-hour, transcontinental broadcast was more than just a benefit performance: It was a marketing exercise that distilled the African continent’s complex history into a logo seen by more than a billion television viewers—roughly one-fourth of the planet’s population at the time.

Related Story

‘Music Is Beyond Politics’: When U2 Went to Bosnia in 1997

If, on that day, Africa’s symbolism to the world became an empty silhouette welded to the neck of a guitar, then the continent also became a star. Never before had it featured so prominently in the worldwide media spotlight, nor had music fans been urged on such a massive scale to help others. The concert raised questions about the efficacy of celebrities advocating for foreign aid, but it also undoubtedly changed the nature of fundraising by introducing the factor of high visibility thanks to celebrity philanthropists. Today, 30 years later, as famous figures continue to wield influence on social media to promote charities, Live Aid’s legacy continues to be felt in fundraising efforts and movement-building around causes.

* * *

One of the major charity events to debut in the U.S. this year was Red Nose Day, a comedy telethon that benefits efforts to fight global poverty. In the lead-up to the inaugural airing of the TV special in May, Walgreens sold more than $7 million worth of recyclable noses alone. That’s a drop in the ocean, however, compared with the £1+ billion the tomato-shaped noses have brought in from British telethons over the past 30 years for the charity Comic Relief, which launched the same year as Live Aid. These red noses are a reminder of how ubiquitous the act of charitable giving to Africa has become since 1985: Currently, on the consumer ratings site Charity Navigator, nine of the “Top Ten Most Followed Charities” provide direct funding to programs on the African continent.

There would be no red noses without Live Aid, at least according to the filmmaker Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually), who co-founded Comic Relief and Red Nose Day in the 1980s after being inspired by Live Aid’s organizer Bob Geldof. “I remember watching [the ensemble] Band Aid and Live Aid and feeling like I should be involved, then I ended up in Ethiopia for three weeks,” he says. “This was when the famine was still very bad, and I saw terrible things—really close up—which changed my life completely. It led to a lifelong commitment to end extreme poverty.”

The term “extreme poverty” didn’t exist before Live Aid; it was coined in 1995 when the UN defined it as a base measurement (equivalent to an income of less than $1.25 per day) used in the research that led to the creation of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000. The origins of the phrase are inextricable from the graphic pictures of Ethiopian famine victims shown on BBC television in the fall of 1984. The images of starving children in one of the poorest places on earth moved Geldof (the lead singer of the Boomtown Rats) and Midge Ure (Ultravox) to write the charity single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and assemble an all-star group to record it that November. After accompanying the first shipment of aid to Ethiopia funded by the sale of the song in the spring of 1985, Geldof returned home to London, determined to do more, which led to the birth of Live Aid.

A lot has changed in the last 30 years, and the results in Ethiopia are mixed: The concert’s poster child Woldu grew into a healthy adult but resents being used as a symbol of Western aid. Ethiopia has become one of the fastest-growing economies on the continent, although the country’s regime has been rightly criticized for government control of market sectors and human-rights violations. This month, on the anniversary of Live Aid, the UN is hosting a development conference in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa to discuss new global goals to be instituted this fall. The country’s situation has improved but more work lies ahead.

Aid is still a complicated topic, yet progress on the continent is real: The Brookings Institute reports that the share of Africans living in extreme poverty fell from 60 percent in 1996 to 47 percent in 2011 and is expected to fall to 24 percent by 2030. The credit for these achievements belongs to African countries themselves, but Live Aid’s acolytes—including actors, musicians, doctors, aid workers, faith-based grassroots organizations, and average citizens—have played a supporting role by lobbying governments to invest in programs that help fight the root causes of poverty and save lives from preventable diseases such as AIDS and malaria.

In the years following Live Aid, the Band Aid Trust (set up to handle donations from the sale of music and video/DVD licenses) continued to distribute funds to an array of charities working on the continent of Africa. Criticisms of Live Aid's money trail, including reports about funders suspected of using monies to purchase weapons in the 1980s, have made philanthropists, governments and charities who work in Africa acutely aware of the impact of corruption on the donation chain. Today, aid groups such as Oxfam have joined the International Aid Transparency Initiative, which helps organizations assess transparency and provide data resources to donors.

UNICEF and Amnesty International both held charity concerts in the 1970s (including George Harrison's Concert for Bangladesh), but Live Aid was the first to harness the powers of mass media and peer-to-peer persuasion to bring the world together around a targeted cause. After the initial event, the concert’s impact spread via the “Six Degrees of Geldof”—a web of celebrities and influencers who evangelized about Africa within their networks, eventually getting the word to billionaire philanthropists and world leaders.

If Live Aid had never happened, would Richard Branson have swum with Desmond Tutu while discussing world peace? Would Ted Turner have funded mosquito net initiatives, or Bill and Melinda Gates committed their wealth to provide vaccinations and contraceptives, or Jimmy Carter spent his post-presidency trying to eradicate tropical diseases in countries like Nigeria? Would George W. Bush have enacted PEPFAR (the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), a massive government initiative to fight AIDS/HIV around the world? Would David Cameron have devoted unprecedented amounts of money to the UK's foreign assistance budget? It's also easy to question whether the African schools, water wells and AIDS-awareness campaigns of Oprah, Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, Will.i.am, Annie Lennox, and Alicia Keys would exist today if Live Aid hadn’t set the precedent for celebrity focus on the continent.

If Live Aid had never happened, would Richard Branson have swum with Desmond Tutu while discussing world peace?Rock stars influencing the policies of world leaders might not have been possible before Live Aid, but an interconnected world in which African countries experience major economic growth might have become a reality even without celebrity concerts. “We didn’t need Bono or Geldof to alleviate tragedies in Africa,” says William Easterly, a professor of economics at New York University. “Without the legacy of Live Aid, the West's view would be less condescending and more Africa-centric. As it is, our patronizing attitudes perpetuate the idea that we are the source of hope.”

If a song had the power to make 1980s music fans feel like they could help “feed the world,” it wasn’t because they perceived themselves as colonialists, but rather as activists, says Coldplay’s Chris Martin, who was eight years old when Live Aid aired on the BBC in the summer of 1985. “I remember it,” Martin says. “It made my generation feel like caring for the world was part of the remit. Rock and roll doesn't have to be detached from society.” After Band Aid and Live Aid transformed the purchase of records and concert tickets into meaningful charitable contributions, music became the advocacy tool of choice. “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” inspired other records such as USA for Africa's "We Are the World” for famine relief; Steven Van Zandt’s “Sun City” in protest of South African apartheid; and a Dionne Warwick remake of the Burt Bacharach ballad, “That’s What Friends Are For” for AIDS research.

At Live Aid, regular songs became anthems as they assumed the gravitas of the day. Howard Jones’ “Hide and Seek;” U2’s 12-minute version of “Bad;” and the gospel overtones of Teddy Pendergrass singing, “Reach Out and Touch (Somebody’s Hand)” added to the show's groundswell. “It was like dropping a pebble in a pond, and the ripples were huge,” says the co-organizer, Midge Ure. “The average guy on the street felt connected to making a difference. Live Aid wasn’t [the artists’ baby], it belonged to the fans. They created the momentum by putting their hands in their pockets, buying the record, and by being at the concerts."

Elizabeth McLaughlin was 23 when she attended the London show and stood within feet of the stage. She remembers the moment the sun fell below the rim of Wembley Stadium and the audience clapped in unison to Queen’s “Radio Ga Ga.” “People were crying a lot,” she says. “The combination of the images on the screens and the messages coming from the artists reminded us why we were there. We knew we had to do more.” McLaughlin credits Live Aid for influencing her to leave a career as stockbroker and later become a country director for CARE. “Whatever came out of Live Aid—millions of pounds and dollars, that’s great. But what really happened at the concert is that a new generation was born, a generation meant to be aware of what’s going on around us.”

Live 8, a Live Aid sequel, was staged in 2005 before the G8 summit and “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” has been re-recorded three times, including in 1989, 2004 and a version last year for Ebola relief in West Africa. Thanks in part to young fans of the band One Direction, which participated in 2014’s “Band Aid 30” recording, the song went to number one on the U.K. charts, even if its message didn't fly with Millennials.

Ironically, Live Aid may have been to blame for the backlash: Today’s viral videos, online charity ads, and point-of-purchase donations are direct descendants of the marketing tactics used in the promotion of the original Band Aid record and the Live Aid concerts. Since 1985, joining causes has become as important as donating to them, and Millennials like to do both. In a 2014 report by the Case Foundation, 87 percent of Millennials who participated in a charitable-giving and corporate-volunteering survey contributed to charity the previous year, but 97 percent responded that they prefer to use their individual skills to help a cause.

Since 1985, joining causes has become as important as donating to them, and Millennials like to do both.“Millennials want the work to get done, and they want a piece of the action,” says 29-year-old Luvuyo Mandela, a South African activist who is the great-grandson of Nelson Mandela. Mandela says he feels that young Africans are largely uninterested in who takes credit for progress in reducing poverty or eliminating AIDS, regardless of whether they believe Africa wants or needs unsolicited aid from other continents. Whereas the Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers took on Live Aid’s mantle of “saving the world” with their armchairs, pocketbooks and telethons, Mandela believes his generation wants to be “the entrepreneurs that make lasting change happen through actions in everyday life.” In the wake of Invisible Children’s quick-burn viral campaign calling for the capture of the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, Millennials may be more skeptical about blindly joining new causes.

Hugh Evans, a 32-year-old Australian, said he believes that charity concerts are no longer staged for impoverished people they aim to help but “for the advocates who attend them.” The annual Global Citizen Festival he initiated four years ago brings 60,000 fans to New York’s Central Park every September to hear from performers like Stevie Wonder and Foo Fighters and leaders such as the World Bank president Jim Yong Kim and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. For these concertgoers, who earn their entrance into the event by signing online petitions or posting charity content on social media, music is the mouthpiece, but not the motivator.

The deliberate planning that went into this year’s festival shows how far things have come since 30 years ago. Unlike the chaotic Live Aid press conference held in June 1985 to announce a lineup of artists Bob Geldof had scribbled on a sheet of paper, Evans’s affair uses the latest technology. Curtis has developed a short animated film to screen, and no images of poor children are shown. Instead, Beyoncé, this year's festival headliner, makes a guest appearance via video. But the end goal—improving living conditions for people global scale—remains the same.

Evans is too young to know how it felt to watch 70 musical acts play Live Aid on a hot July Saturday three decades ago. Yet, perhaps because of that concert, he and other advocates like him grew up believing that every person, rock star or not, has the ability to affect change, however slowly. If future generations live in a world where there’s less need to remember why Live Aid was held on July 13, 1985, then the concert’s legacy will surely be complete.

Greece's Agreed-Upon Plan Looks a Whole Lot Like the One It Just Rejected

In the wee hours of Monday morning, after a marathon 17-hour session, Greece finally agreed to a deal with the euro zone that would give it enough cash to start reopening its shuttered banks, pull it out of arrears, and stave off its exit from the euro.

In some ways this deal (or any deal) might be seen as a victory, pulling Greece back from the brink of the possibly disastrous expulsion from the euro—but the accepted proposal also marks some pretty significant defeats at the end of a months-long struggle, with Greece conceding to many of the conditions it fought so hard against.

Fewer than 10 days ago, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras had the Greeks vote on a proposal put forth by the Eurogroup on June 26 that included adding additional austerity measures, such as cuts to pensions and benefits, in order to trim the country’s budget. Tsipras and then-Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis urged the people of Greece to vote “no” to the deal—saying that the cuts that came with it were unduly harsh and would worsen the country’s already fragile economy. Both said they would resign if citizens agreed to their creditor’s harsh terms (though leaked correspondence later showed signs that Tsipras was on board for making major concessions).

With the country already in arrears to the IMF, the people of Greece sided with their leaders, shooting down the proposal of the euro zone and pushing the country into uncertain economic territory. By calling for a referendum, Tsipras asked the people of Greece to either accept the onerous proposal from the Eurogroup, or to trust him and his party to negotiate a better one. The cost of the referendum (and its outcome) was high: The announcement of a vote halted talks, allowing the country to default, and the wait for the referendum and its outcome further delayed a potential agreement, locking the country in financial limbo. Some Eurogroup leaders were openly angry about the referendum. Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s deputy chancellor was quoted as saying that the Greek government had “torn down the last bridges over which Europe and Greece might have been able to move towards a compromise.”

With so many false starts and political posturing that surrounded (and arguably delayed progress of) talks of a deal, it can be hard to tell how much Greece really won by rejecting the euro zone’s original plan—and how much better, or worse, the newly accepted deal actually is. The most contested issues in the original plan were the lack of debt restructuring and the heightening of already-burdensome austerity measures.

In looking at the language in the two proposals, there seem to be many similarities and few clear victories for Greece. The original plan required cuts to pensions, increasing taxes, and streamlining Greece’s VAT system, additional budget cuts, and privatization of some of the country’s assets. The new plan calls for cuts to pensions, increasing taxes, and streamlining Greece’s value-added tax [VAT] system, additional budget cuts, and privatization of some of the country’s assets.

Here is a more detailed look at how the language in the rejected proposal stacks up against the language from Monday’s deal, put together with help from my colleague Bourree Lam.

On pensions:

Old: “The authorities will adopt legislation to fully offset the fiscal effects of the implementation of court rulings on the 2012 pension reform … Create strong disincentives to early retirement, including the adjustment of early retirement penalties, and through a gradual elimination of grandfathering to statutory retirement age.”

New: “Upfront measures to improve long-term sustainability of the pension system as part of a comprehensive pension reform programme. Carry out ambitious pension reforms and specify policies to fully compensate for the fiscal impact of the Constitutional Court ruling on the 2012 pension reform and to implement the zero deficit clause or mutually agreeable alternative measures by October 2015.”

On privatization:

Old: “The Board of Directors of the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund will approve its Asset Development Plan which will include for privatisation all the assets under HRDAF as of 31/12/2014; and the Cabinet will endorse the plan.”

New: “Valuable Greek assets will be transferred to an independent fund that will monetize the assets through privatisations and other means. The monetization of the assets will be one source to make the scheduled repayment of the new loan of [European Stability Mechanism] ESM and generate over the life of the new loan a targeted total of EUR 50bn of which EUR 25bn will be used for the repayment of recapitalization of banks.”

On labor:

Old: Launch a consultation process similar to that foreseen for the determination of the level of the minimum wage to review the existing frameworks of collective dismissals, industrial action, and collective bargaining, taking into account best practices elsewhere in Europe.