Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 390

July 16, 2015

The Grumpy, Irrelevant Ranting of Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll

Denis Leary has always been an angry man. It was the cornerstone of his supernova stand-up comedy career, where his on-stage persona was the furious, ranting Middle American who begrudged any intrusion into his desires to smoke, eat red meat, and drink black coffee. Rage was the glowing core of his hit FX drama Rescue Me, a post-9/11 tale of an alcoholic New York fireman struggling with survivor’s guilt that ran for seven seasons. Now Leary has returned to FX, and he’s still angry—but this time, it’s at middling celebrities. His new sitcom Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll dares ask the truly tough questions, such as: Why are Lady Gaga or Kim Kardashian famous?

Related Story

How TV Dramas Like ‘Justified’ and ‘Mad Men’ Deal With Fatherhood

His new material is as deliberately provocative and ultimately redundant as a complaint from an anonymous Twitter troll. Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll is ostensibly a gritty comedy about a washed-up musician trying to find a way back into the limelight. But like any of Leary’s works (he wrote the pilot and plays the lead character, the helpfully named Johnny Rock), it’s peppered with grumpy monologues about the sad state of America as a nation. According to Johnny Rock, things aren’t helped by our veneration of tabloid-friendly superstars who are famous mostly for being famous. The tiredness of such an argument underlines how Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll feels like a lame rerun of Leary’s better hits, lacking any of their authentic fury.

The show follows Rock, the former lead singer of an early-‘90s rock group called The Heathens that burned out before it could fade away, leaving a legacy of one supposedly masterful album and a reputation for self-destructive partying and heroic cocaine use. It’s hard to exactly pinpoint what musical movement Mr. Rock and his compatriots belonged to—given the era, you might imagine something a little grungier than the mulleted, vaguely punky hair-metal of The Heathens, who viewers glimpse only in a mock Behind the Music-style rockumentary narrated by real-life music luminaries like Dave Grohl, who supposedly considers them an influence.

Johnny nurses a grudge against the Heathens guitarist Flash (John Corbett), who ditched the band to become a session musician working with stars like Lady Gaga. But, out of money and looking to get back in the limelight, he reunites with Flash and his former drummer Bam Bam (Robert Kelly) to perform in a new group fronted by his daughter Gigi (Elizabeth Gillies) who he’s only just met.

As with many of Leary’s projects, it’s hard to know just how much self-awareness comes with the writing. His best work, Rescue Me, had no trouble painting protagonist Tommy Gavin as a misogynistic, alcoholic bully; but he was also a hero firefighter who bedded scores of women, almost all of whom turned out to be either shrewish, insane, or both. It often struggled to find the right amount of “anti” for its antihero, and Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll feels similarly burdened. When he meets his daughter in a bar (not yet knowing he’s her father), Johnny forces a drunken kiss on her before she sets him straight.

Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll struggles to find the right amount of “anti” for its antihero. Johnny’s complaints that artists like Lady Gaga are all flash, no substance would feel like flimsy satire in 2009, and now come off as hopelessly outdated. Every potshot at the barn door that is contemporary music sails wide, and Johnny’s antics feel irrelevant from the start, even though the narrative arc of the series is framed as a big comeback story.It certainly helps that Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll only runs 30 minutes—the more inconsequential it seems, the better it plays, and Leary does his best to sell even the lamest complaints in his crackling stand-up delivery, which hasn’t completely lost its touch. Corbett feels smartly cast as a former roustabout who’s managed to navigate the straight and narrow, a nod to previous (and far better) roles on shows like Northern Exposure and Parenthood. In terms of the overall story being told, Gigi is framed as the future of music, and Johnny as the grousing past—but the writing doesn’t reflect that, with Johnny getting all of the airtime and meaty flaws, and Gigi not much more than a roaring set of pipes.

Sex&Drugs&Rock&Roll might redeem itself if it can expand its ambition beyond bitter rants about the state of the world today, but if not, it’s no less shallow and cynical than the glossy pop it seeks to skewer.

Exposing Companies That Pay Women Less Than Men

It’s often considered gauche to ask people about their salaries, but the British government is planning to do just that. In a bid to combat the gender pay gap, Prime Minister David Cameron announced on Tuesday that his government will institute a measure requiring companies with more than 250 employees to publicly disclose information on the average pay of their male and female workers. The move, the prime minister hopes, “will cast sunlight on the discrepancies and create the pressure we need for change, driving women’s wages up.” Some critics believe he’s overestimating the power of that sunlight—and underestimating the structural inequities behind such discrepancies in the workplace.

The regulations, which were passed in March but initially opposed by Cameron’s Conservative Party, will now be subject to public consultation until September. The consultation will determine “exactly what, where, and when information should be published,” and the government is “working closely with business and others to find the most workable and effective way of implementing the regulations,” according to a British Embassy spokesperson. The legislation won’t come into force until October 2016 at the earliest.

Related Story

How to End the Gender Pay Gap Once and for All

It’s a British solution to a global problem. There are many different ways to measure the pay gap between genders, leading some to even assert that the whole concept is a myth. But official statistics from a variety of sources suggest that women’s compensation continues to lag significantly behind men’s around the world.

In the United States, for instance, women earn less than men who work in the same field and have the same academic qualifications, according to a 2013 congressional report. In their first year of work after getting a bachelor’s degree, women make roughly $7,600 less per year than men. These wage discrepancies often persist throughout a woman’s career and make it harder for women to pay off student loans (which women are more likely to have, and to have more of) and save for retirement. Closing the pay gap wouldn’t just help create a fairer society and workplace; it could also halve the poverty rate for working women in the United States, according to the Center for American Progress.

In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, the pay gap—as measured by the difference between men’s and women’s hourly earnings as a percentage of men’s earnings—is at just under 10 percent for full-time employees and just under 20 percent for all employees, according to a 2014 report by the Office for National Statistics. That puts the U.K. in the bottom quartile for gender wage equality in the European Union. A 2014 World Economic Forum (WEF) report, which takes a more global view, places the U.K. at 48 out of 131 countries on gender pay equity; by comparison, the United States is ranked 65th. The most equitable country in this regard? The small East African nation of Burundi.

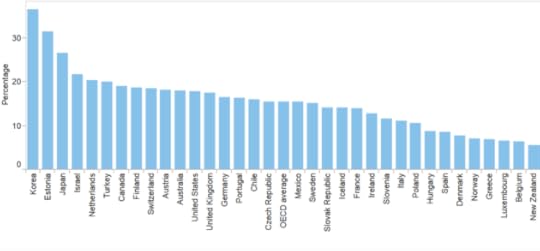

Here’s how the wage gap between men and women in the U.S. and U.K. compares with those in other countries within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The gap is largest in South Korea and smallest in New Zealand.

Gender Wage Gap by OECD Country

Wage gap data is for full-time employees and is defined as the difference between male and female median wages divided by male median wages. (OECD)

Wage gap data is for full-time employees and is defined as the difference between male and female median wages divided by male median wages. (OECD) Britain’s new approach to this challenge isn’t entirely novel among its neighbors in Europe, according to a breakdown of the continent’s policies by Shirley Wright of the British law firm Eversheds LLP. The Swedish government requires employers to carry out (but not publish) a pay survey every three years; if unjustifiable pay differences between genders are found, the differences must be remedied within another three years. The Austrian government mandates an annual gender pay report for all companies with 150 employees or more, with the findings occasionally shared with employees. In Denmark, employers must discuss gender pay audits with employees. In Belgium, firms are required to include gender wage differences in annual audits, and companies with more than 50 employees must draft a plan of action when a pay differential is discovered. Federal contractors in the United States are required to monitor and report data on compensation by gender to the Department of Labor, but there are no such requirements for the private sector as a whole.

It’s not always clear how effective these innovative policies are, but the good news is that in much of the world, the pay gap between men and women is slowly shrinking. Still, the emphasis should be on the word “slowly.” According to the United Nations, it will take 70 years to close the gender gap in pay around the world. That’s over half a century more of less income, less savings, and less dignity. Sunlight only moves so quickly, and reaches so far.

July 15, 2015

‘My Atticus’

Atticus Finch. The man who has been dubbed one of the “all-time coolest heroes in pop culture” and the “Best. Dad. Ever” and “the greatest hero of American film,” the man whose wisdom concerns everything from “manliness” to “leadership” to “life” itself. The man to whom many practicing lawyers have attributed their interest in legal work and who, over the years, has lent his name not only to children and pets, but also to

What the Next U.S. President Should Do With the Iran Deal

The next president of the United States will almost certainly be more hawkish on Iran than Barack Obama. Maybe a little more hawkish, if Hillary Clinton; potentially a lot more hawkish, if a Republican. What can that president do about the nuclear accord that the Obama administration and several world powers have struck with Iran?

On Tuesday, Obama told Thomas Friedman of The New York Times that his Iran deal will equip his successor with more and better options on Iran than he inherited. The opposite is true. The next president will have fewer and worse options, because the most effective sanctions against Iran will have been suspended in a way that is very difficult to reimpose.

But fewer and worse options does not mean zero options. There are things the next president can do to improve a bad deal.

Related Story

The Single Most Important Question to Ask About the Iran Deal

The United States has surrendered much of its leverage over Iran, but not all. Under the terms of the deal, many of which are designed to be in place for 10 years or more, Iran must remove two-thirds of its centrifuges, reduce its enriched-uranium stockpile, and downgrade important nuclear facilities like Arak and Fordow. This work must be completed before sanctions relief begins and before frozen funds start to flow back to Iran.

This work will take some time. There will be a moment when Iran has dismantled a multibillion-dollar nuclear investment and faces a multibillion-dollar price tag to rebuild it. Exactly how long that moment will last is difficult to say. As part of the agreement, Iran will retain a considerable nuclear infrastructure and will continue to enrich uranium with its remaining centrifuges. The unfreezing of as much as $100 billion of Iranian assets worldwide will provide Iranian officials with new resources. Still, for some period of months, the prospect of the nuclear deal failing will be very frightening for the country’s rulers. Much of their old nuclear program will be gone, their new program won’t yet have been built, and their cash infusion will only have just begun.

During that period, a new president may be able to press Iran to renegotiate the Obama deal’s worst terms, especially its weak inspection provisions. Presidents have more options than to either accept or junk agreements. They can renegotiate them too, as candidate Barack Obama pledged to renegotiate NAFTA during the 2008 campaign. He ultimately decided against that course of action, but the option was there. The option will be there with the Iran agreement too.

Obama always had better options than war or this inadequate deal. He did not avail himself of them.Iran, after all, faces a long road back to economic normality. The oft-cited reference to Iran’s $100 billion in frozen funds obscures the fact that many of these “funds” take the form of non-cash assets. The Iranian government owns a dozen real-estate properties in the United States. A state-controlled bank owns an interest in a New York office building. Liquidating those assets will take time. They may also prove to have deteriorated in value during the period in which they were frozen.

Sanctions relief may likewise take a while to benefit Iran. The Iranian economy is hobbled by self-imposed restrictions. Multinational oil companies may not rush to invest large sums in a country that continues to hold American hostages—especially not at a time of low and falling oil prices. Iran will surely be better able to afford mischief in five years than today. It’s not so clear that it will have gained much more freedom of maneuver in 18 months.

In other words, the next president will have opportunities to slow, or threaten to slow, Iranian economic recovery as part of an effort to press for renegotiating elements of the current deal. Iran’s rulers have raised expectations of economic betterment inside the country. Those raised expectations may generate useful political pressure on the regime—and useful fears within the regime of the consequences of not delivering on those high hopes.

The next president can also offset some of the negative diplomatic and regional consequences of the deal. Obama accepted the alienation of Israel and the Gulf States as the price of his Iran initiative. The next president can reconstruct those relationships, abandon the illusion of Iranian partnership, and renew the building of a strategic counterweight to Iran. It’s incredible that Iranian rulers got away with offering Iranian cooperation against ISIS as a concession to the United States. ISIS threatens Iran more than it does the United States; it is Iran that needs U.S. help to protect its clients in Syria and Iraq. The next president can wield the real strategic advantage that the United States has over Iran, rather than yield to the imaginary advantage that Iran asserts over the United States.

Admittedly, these aren’t great options. But they are better than zero options, and they are short of war. Obama likewise always had better options than war or this inadequate deal. He did not adequately avail himself of them. The next president could and should.

The Miracle in Orange Is the New Black's Season 3 Finale

Has any phrase been quite so harmed by overuse as “It’s a miracle” has been? The first time I watched Suzanne “Crazy Eyes” Warren say those three supposedly wonder-filled words, about 11 minutes before the conclusion of Orange Is the New Black’s third season, it seemed like the kind of casual exaggeration that greeted the news of Taco Bell offering late-night delivery.

But after sitting through the rest of the episode, I’ve seen the light. Suzanne was speaking factually. The show’s finale gave its characters a real miracle, and in some ways, it gave viewers one, too—one of the best TV scenes in recent memory, or maybe ever.

Related Story

Orange Is the New Black Has Never Felt Freer

The setup is as implausible as any biblical phenomenon. After a season’s worth of squabbles, the prison’s veteran guards go on strike the same day that major renovations are planned. The inmates, banned from the dorms while new beds are being installed, congregate in the yard, where contractors just happen to be scheduled to replace a portion of the fence. With a few innocent snips, a portal to the outside world opens up, and there’s not a correctional officer in sight.

The ever-silent supposed miracle worker “Norma Christ,” glum about the dark turn that her kindness cult has recently taken, is the first to notice. Her face, used to express so many different emotions over these three seasons, is overtaken by joy, and she doesn’t hesitate before bolting. The other prisoners need a second before deciding to follow. Is this really happening? Won’t they be caught? Gloria, stressed this season like she’s never been before, is the first to make up her mind. “Maybe they’re expanding the yard,” she says, feigning naïveté. “How are we supposed to know any better”? Elsewhere, Taystee tsks tsks at all the prisoners about to end up in solitary. But Poussey tells her to lighten up—no one has illusions of permanent escape: “Let’s just be free for a second. It’s going to be the last time in a long time.” C.O. Luschek sees the flood of running inmates and just goes back inside; the newbie guard Bayley panics, totally unequipped to stop what’s happening.

In a remarkable filmmaking ploy for a show whose greatest strength is its banter, the rest of the episode is wordless, outside of a Hebrew prayer and the shouting of some names. Over its three seasons, Orange Is the New Black has done such a good job teaching viewers who these characters are that the moment’s significance for each woman doesn’t need to be explained through dialogue.

No other show could have pulled off anything like it, and this show likely will never get to again.Crazy Eyes is the first to the lake outside the fence; she dives in and stays under for so long that the other women start to worry. But then she bursts back up to the surface and laughs, and everyone else takes off their boots and sloshes into the water. It’s an encapsulation of Suzanne’s recent transformation from outcast to someone whose creativity and individuality has made her one who unites the prison.

From there, it’s mostly a montage of the cast members doing not much other than floating, sitting, and splashing. Flaca closes her eyes and looks upwards, no doubt thinking about her mother who’s fighting cancer. Pennsatucky playfully quacks like a duck at her friends, a routine that she was last seen performing with the man who would later rape her. And Suzanne, who we recently learned is shy about never having had sex, starts to return the affections (and turtle) of Maureen.

Netflix

Netflix There are a number of silent reconciliations, many between mother figures and the girls they’ve imperfectly nurtured: Red and Norma, Gloria and Flaca, Aleida and Daya. When Taystee bundles her hair up and wades in to join the other black women, it feels like she’s finally embracing her new role as leader of the group. And when Boo hoists up Pennsatucky, it’s the ultimate symbol of the lovely relationship that’s developed between a liberal butch lesbian and an abortion activist from the sticks.

The two most powerful moments belong to characters who’ve never been considered stars of the show. After a wrenching season-long slide into depression on account of loneliness, Soso floats on her back and stares vacantly into the sun until Poussey drifts by and takes her hand. It’s a moment of kindness so simple and so desperately necessary as to be devastating.

Netflix

Netflix The second great moment is Black Cindy’s. Earlier in the episode, she converted to Judaism in a scene that would have been the very best Orange Is the New Black has ever aired were it not for the lake sequence. Now, she finalizes the deal by being submerged naked as a new friend in faith blesses her, and Cindy grins more widely than just about anyone ever has on this show.

The final words of that Mikvah blessing are the final words spoken this season on screen—“Mazel tov,” an expression of congratulations and a wish for good fortune. This is likely no accident. Season three has largely revolved around questions of faith and religion, and at the Daily Beast, Arthur Chu has smartly explained the show’s point of view on the subject:

Orange Is the New Black is a show about how Big Faith, what Soso calls “capital-R Religion,” is a trap—the kind of faith that believes in ultimate justice and in final answers, the kind that says you can be confident in how the story ends. It’s the kind of faith that’s brittle, fragile, that sets you up for a brutal fall. [...]

But the other kind of faith? Little Faith? Faith as tiny as a mustard seed? The kind that won’t throw away the armor of cynicism but will take it off long enough for a swim, that says that there’s no clear path by which everyday kindness and love will fix this broken world and bring a happy ending to our story? That’s the kind of faith that, by not asking for too much, isn’t too easily broken. It’s the kind that can survive betrayal, suffering, hypocrisy—even prison.

The great lake escape is all about Little Faith. The women know they aren’t going to swim away from Litchfield forever, and in the episode’s final moments viewers learn the prison population is about to balloon. But the opportunity to enjoy something novel and cleansing is as much grace as these characters have been shown since arriving at Litchfield, and they respond with what my colleague Sophie Gilbert has identified as Orange Is the New Black’s controlling value: kindness. Note that Piper, the one character who’s gotten meaner and harder as the show has gone on, doesn’t partake; she’s in the chapel, tattooing herself after responding to a lover’s betrayal with a far worse one.

A cynic could argue the scene’s just a treacly wish-fulfillment binge after 13 hours largely filled with rape, violence, betrayal, intolerance, and smelly panties. But what exact wishes are being granted? Small, personal ones that still feel enormous, as so many small, personal victories in real life often do. Compared to the bleak landscape of prestige television, this is special. Even in the context of Orange Is the New Black’s history, it’s remarkable—the previous finale went large rather than small with its divine intervention by smacking down big bad Vee. A vacation to a sun-dappled lake for people we’ve seen cooped up over three years is a very specific kind of payoff; no other show could have pulled off anything like it, and this show likely can’t ever again. Like most miracles, it was one-time only.

What Does the Planned Parenthood Video Show?

A video of Planned Parenthood's medical director discussing the harvesting of tissue from fetuses, released Tuesday, is at the center of the latest national controversy about abortion. Not only does the video raise questions about Americans’ comfort with the practice, but it quickly morphed into a metastory, with conservatives accusing liberals of ignoring clear evidence of immoral lawbreaking at the nation’s largest provider of abortions. That has quickly become the central issue: Is this another version of the Shirley Sherrod video, a misleadingly edited video taken out of context? Or is it more akin to the Kermit Gosnell story, a horrifying case that mainstream reporters ignored until they were forced to reckon with it?

In the video, Deborah Nucatola, Planned Parenthood’s senior director of medical services, discusses harvesting tissue and organs from aborted fetuses over lunch in Los Angeles. While some previous “sting” videos like this have been criticized for misleading editing, the anti-abortion group behind it, the Center for Medical Progress, also posted a longer version, running nearly three hours. (The video doesn’t illuminate the conversations involved in setting up the lunch. Its makers apparently presented themselves as middlemen for medical researchers seeking fetal tissue.)

The story promptly exploded within the conservative-media sphere, but mainstream reporters were slower to pick it up, probably in part because of the difficulty of sussing out the video’s provenance and the legal issues involved. The Center for Medical Progress claims it shows that “Planned Parenthood sells the body parts of aborted fetuses,” which would be illegal. Women who have abortions can choose to donate fetal tissue for research, and providers can be reimbursed for costs involved in that process, but they can’t profit. Here’s what Nucatola says early in the video:

I think every provider has had patients who want to donate their tissue, and they absolutely want to accommodate them. They just want to do it in a way that it’s not perceived as, ‘This clinic is selling tissue and making money off of this [inaudible].’ I know in the Planned Parenthood world, for example, they’re very, very sensitive to that. And before an affiliate is going to do that they need to—obviously they’re not—some might do it for free. They want to come to a number that it doesn’t look like they’re making money. They want to come to a number that looks like it is a reasonable number for the effort that is allotted on their part. I think for private providers, or private clinics, you’ll have much less of a problem with that.

There’s ambiguity in that statement. Planned Parenthood says she’s just discussing donations to recoup costs, and Nucatola’s caution about the organization seems to make clear that Planned Parenthood doesn’t tolerate sales. On the other hand, the way she describes the arrangements could easily be interpreted to suggest that the numbers are rigged, so that it seems like they’re just recouping when in fact they are a revenue stream.

Later in the video, she discusses possible amounts involved, ballparking figures between $30 and $100. But she also states, “This is not—nobody should be ‘selling’ tissue.” Perhaps the more damning remark isn’t about Planned Parenthood at all but about the private clinics; her comments imply unscrupulousness and possibly illegal behavior by those providers, but Planned Parenthood’s size and prominence makes it the prime target for pro-life activists.

All of this makes it tougher to believe the bluntest claim that Planned Parenthood, or even one top official there, is actually selling organs for profit. That hasn’t prevented immediate demands—from Ted Cruz, for example—for the government to investigate and defund Planned Parenthood for “profiting off the bodies of the lives they have stolen.” Multiple GOP presidential candidates issued statements expressing disgust with Nucatola’s comments.

But even if there’s nothing illegal, it’s easy to see how the video is a coup for the anti-abortion movement. The pro-choice and pro-life movements tend to talk about abortion in very different terms. Those who support abortion couch their argument in terms of women’s bodily autonomy, or in terms of a right to privacy. Abortion opponents sometimes use similar rights language, speaking of the rights of the unborn. Yet they also often use graphic images of aborted fetuses, for example, to highlight the visceral reality of abortion. There’s some debate about this practice among pro-life campaigners, but pro-choice activists acknowledge that abortion isn’t pretty and that there’s an easy disgust factor to it. (There’s a reason that although a majority of Americans favor legal abortion, a plurality also say it’s morally wrong.)

That’s what may make the video potent. Nucatola discusses the use of tissue from aborted fetuses, including the extraction of specific organs, over a casual lunch. That may strike many viewers as callous and inhumane. The disgust factor is real and important. For example, the activists posing as buyers ask Nucatola about the condition of organs after procedures. She responds with a detailed answer about how abortions are conducted to ensure good conditions. It’s not especially appetizing:

I’d say a lot of people want liver. And for that reason, most providers will do this case under ultrasound guidance, so they’ll know where they’re putting their forceps. The kind of rate-limiting step of the procedure is the calvarium, the head is basically the biggest part. Most of the other stuff can come out intact . . . So then you’re just kind of cognizant of where you put your graspers, you try to intentionally go above and below the thorax, so that, you know, we’ve been very good at getting heart, lung, liver, because we know that, so I’m not gonna crush that part, I’m going to basically crush below, I’m gonna crush above, and I’m gonna see if I can get it all intact.

There’s a small cottage industry devoted to producing videos that showcase the emotionally wrenching side of abortion. The Center for Medical Progress, which produced the video, is headed by David Daleiden. Daleiden is a veteran anti-abortion activist who previously worked with Live Action. Live Action is the group led by Lila Rose, most famous for the video she made with conservative provocateur and filmmaker James O’Keefe, in which they posed as a pimp and an underage prostitute seeking an abortion at Los Angeles Planned Parenthood clinics. The latest sting appears to have been in the works for quite some time—a timestamp on the video released Tuesday says it was shot on July 25, 2014, nearly a year ago.

Planned Parenthood is a major target for the pro-life movement because of its size and national reach. The organization provides a range of family-planning and reproductive-health services in addition to abortion, and it receives a large chunk of its funding from the federal government, for the other services that it provides. It’s banned from using any federal money to provide abortions, but critics say the ban is functionally pointless, since funding is fungible. Republicans in Congress regularly attempt to keep federal money from going to Planned Parenthood.

In 2012, amidst a GOP congressional investigation into Planned Parenthood, the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure, a leading breast-cancer non-profit, announced it was cutting ties. But the move backfired—Komen was harshly criticized, donations to Planned Parenthood actually increased, and Komen reversed course within days, leading to the departure of a top official who is strongly pro-life.

On Tuesday, Komen found itself back in the crosshairs. Citing the video, House Republicans pulled a bill authorizing commemorative coins that might have raised up to $4.75 million for Komen, because of its donations to Planned Parenthood.

Abortion is an unusual issue in American politics. Despite arousing some of the strongest emotions by advocates on both sides, and despite massive amounts of money spent, opinions about abortion have barely changed since Roe v. Wade in 1973. (Pro-life advocates have had better luck enacting abortion restrictions at the state level.) Whether this video is able to do what so many other past stories failed to do and move the dial will be the issue to watch in the coming days and weeks.

How Hollywood Made Prison Breaks Seem Heroic

The details of the Mexican drug lord Joaquín Guzmán Loera’s escape from prison on July 11 are pure cinema. He fled through a two-foot by two-foot hole drilled in the shower area of his cell, climbing down a ladder to a mile-long tunnel, complete with lighting, ventilation, and a motorcycle on rails. Much like the June breakout of two inmates from the Clinton Correctional Facility in Upstate New York, the news of Loera’s escape was both frightening to nearby citizens and a political setback for local officials. But its vivid details—the tunnel dug just high enough for its subject to walk through, the surveillance camera that had just one blind spot, the whiffs of larger corruption—couldn’t help but conjure memories of one of Hollywood’s favorite subgenres: the escape caper.

Related Story

40 Years Later, the Cruelty of Papillon is a Reality in U.S. Prisons

The Internet was quickly flooded with pop culture’s most indelible (one might even say clichéd) imagery of prison breaks. A torn-down movie poster revealing an escape route in The Shawshank Redemption. Paul Newman throwing chili powder behind him to mask his scent in Cool Hand Luke. An ensemble cast of anti-heroes scattering into the woods on the TV show Prison Break, a one-time hit series that Fox is now reportedly planning to revive.

Considering that jails are essentially supposed to keep criminals out of society, it’s notable how much glee audiences derive from watching someone bypass the protections of a maximum-security prison. But that’s where fact and fiction begin to deviate. Movies and television have long used jailbreak as a thrilling and dramatically potent plot device, but typically affirm the breakees as misunderstood heroes in the process—people who’ve been unfairly convicted or who are Robin Hood-type criminals who largely eschew violence. The redemptive format of the genre belies the reality, even while fictional escapes and real-life escapes continue to inspire each other.

Loera, nicknamed “El Chapo” (or “the shorty”), is one of the world’s most notorious drug traffickers, as well as one of the richest, and at the time of his arrest in 2014, had imported more drugs (including cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine) to the United States than anyone in history. A security analyst called him “the jewel of the crown,” and his escape was seen as a devastating blow to the Mexican government. The two men who broke out of Clinton, Richard Matt and David Sweat, were hardened felons serving time for murder and whose getaways put nearby communities on high alert.

It’s far rarer for a Hollywood jailbreak to feature such unsympathetic protagonists. Usually, to engineer a daring dash out of prison, one needs to possess both incredible craftiness and a winning personality, as well as be either falsely accused or extremely repentant. Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) chisels his way out of Shawshank State Penitentiary after serving 17 years of a wrongful conviction; his friend Red (Morgan Freeman) is only freed when he bluntly discusses his inescapable guilt to a parole board. Luke Jackson (Paul Newman), an angry war veteran, is thrown in the slammer for a victimless bit of vandalism in Cool Hand Luke; the heroes of The Great Escape are breaking out of Nazi imprisonment; the cast of Prison Break are pawns in a larger game of corrupt political gamesmanship that goes all the way up to the White House.

If the hero is an active criminal, he usually abides by a code of honor, like Clint Eastwood’s bank-robber protagonist in Escape from Alcatraz, who defines himself in opposition to the gangsters and rapists who reign in the notorious prison. The same goes for Jack Foley (George Clooney) in Out of Sight, who robs from the rich but is nonviolent. Escaping from jail is just another of his sexy jaunts in the Steven Soderbergh film, which is driven by the amorous frisson between Foley and the U.S. Marshal Karen Sisco (Jennifer Lopez), whom he runs into during his getaway. The titular protagonist of Steve McQueen’s Papillon is a safecracker wrongly accused of a far worse crime, and the two-and-a-half-hour epic is an existential critique of the Kafkaesque horror of prison that features long, torturous spells in solitary confinement.

The prison-drama narrative usually follows a rigid form for a reason. Most moviegoers have little experience of life behind bars, says Frankie Y. Bailey, a criminal justice professor at the University at Albany. “A lot of what they're learning comes from movies or television.”

The protagonist is almost always a new inmate, often wrongly accused, who’s shown the ropes by a wiser, older friend. He or she is defined in opposition to villainous wardens or correctional officers who represent a general oppressive sense of injustice for the audience to rebel against. In that framework, any attempt at freedom feels justified and hard-earned—and usually involves a mix of personal charm and MacGyver-like ingenuity. “It’s like going to a gangster movie or a horror movie. You can play with those stereotypes, but an audience does go in with certain expectations,” Bailey says.

The prison-drama narrative usually follows a rigid form because the typical moviegoer has no real experience of life behind bars.Referencing the Clinton breakout, she notes the soapy drama behind the details of Matt and Sweat’s escape—a female staffer has been arraigned on charges of aiding them, and allegedly participated as part of a larger plan to kill her husband that she backed out of. “At some point it's going to be a Lifetime movie, because that’s the kind of story it is. But [the prisoners] don't fit into the Hollywood stereotype of people you want to root for,” Bailey says.

Instead, Hollywood seeks out prison stories with a redeeming edge, or some social value. Realism is sacrificed partially because of a lack of access to the world inside bars. “Once prisoners are behind walls, particularly in maximum-security prisons, they're inaccessible,” she says. “That's one of the reasons we get a lot of stereotyping and a lot of reasons why the media has to rush to stereotype to fill in the gaps. It blurs the line between news media and entertainment ... You don’t see the everyday, normal life behind bars.”

Exceptions often end up proving the rule, like Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, which itself has featured multiple escape plotlines (that all seem to end in death, one way or another) among its more prosaic stories of life in prison. Inspired by Piper Kerman’s autobiography, the series is shown through the eyes of a white, middle-class protagonist, who gets a whole new perspective on a world she barely understood before her conviction.

Just as the media rushes to romanticize any escape from freedom, pop-culture representations of prison can even make life behind bars seem alluring to some. Many states are now moving away from having inmates wear orange jumpsuits as a result—which themselves were designed in the early 20th century to remove the stigma of the black-and-white stripes Hollywood had made so familiar.

“They’re becoming too popular,” Bailey says. “The uniform itself, there are periods where it moves into fashion. A few years ago in New Orleans, I saw an orange jumpsuit on sale at a gift shop in the French Quarter.”

And yet movies and TV have become a cultural prism through which the public can grasp the grim realities usually beyond their reach. After the Clinton jail break, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo led reporters on a tour of the prison to navigate just how the inmates had broken out. “They put dummies in the bed,” he told the press, indicating how Matt and Sweat had found time to execute their plan. “Like in The Shawshank Redemption.”

The Captivity of Motherhood

“Wives are lonelier now than they have ever been,” Nora Johnson wrote more than half a century ago.

Those words became the first line of a searching and startling essay, a unique amalgam of first person narrative, popular ethnography, and call for social change entitled “The Captivity of Marriage.” It ran in The Atlantic in June 1961.

Fifty-four years later, I read Johnson’s sentence on my iPhone, in the midst of the blaring chaos that I have come to think of as the psychopathology of everyday working motherhood—one kid on his iPad, another rattling around the house, my mind working over dinner and a deadline, my husband in the house somewhere, all the other details.

The 1960s through the eyes of The Atlantic

The 1960s through the eyes of The AtlanticRead More

An Atlantic editor had sent the essay along, and now I was tugged powerfully by the sentence to follow Johnson through the entire piece, rapt as she wove her observations—wry and insightful and, somehow, deeply hopeless— about the state of housewifery and mommy consciousness in Cheever times.

In writing a deceptively simple and straightforward article about her own life and the lives of other women, Johnson’s mission was profound. She was searching for a language for “the problem without a name,” two years before Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique. She wanted to tell us something about the way some people live, people one didn’t normally think of as interesting or worthy of ink, and what it did to them. Her descriptions did something to me as I scrolled, word by word. I wept.

I hid my face as my younger son approached, needing something right that moment, in the impatient way of the youngest child. I anticipated his question: “Mommy, what’s wrong?”

“I read something sad,” I thought I’d say.

The next question was likely to be, “What was it about?” Then what?

“It’s a story about some other people.”

* * *

Things are undeniably different for women now than they were for Nora Johnson, the daughter of the producer Nunnally Johnson. The Pill was new when Johnson sat down to write her essay, and it had not yet revolutionized women’s ability to delay childbearing in order to pursue personal fulfillment and career success. And so only 38 percent of women worked outside the home, most of them in rigidly gender-scripted and relatively low-paying, low-status fields—nursing, teaching, secretarial work. Those who stayed home spent an average of 55 hours a week on domestic chores. Women’s ambitions and autonomy weren’t just undermined by their domestic duties, but institutionally and legislatively as well: With the exception of a right to “proper support,” wives had no legal claim to their husbands’ income or property, while in many states, husbands could control those of their wives through “head and master laws.” How easy could it be—on the days when the thoughts came at you, and the piles of laundry and the obligations like the PTA and your husband’s boss’s wife and the other items on Johnson’s unrancorous but unsparing list piled up—to feel good in your captivity?

Johnson was groping toward feminism’s second wave before it came to be, feeling for a toehold. She listed, in her catalogue not of grievances so much as unsentimental facts about the lives of herself and her conspecifics, the following: isolation, worries about illness and money, and sexual boredom. She referred to the whole schmear as “the housewife’s syndrome, the vicious circle, the feeling of emptiness in the gap between what she thought marriage was going to be like and what it really is like.”

She concluded flatly that the “college-educated mother with a medium amount of money is the one who reflects all the problems at once.” With a keen intellect, but no maid or nanny to whom she could delegate some of her tasks, she found herself marooned on an island of disappointment, ruminating, “This isn’t what I wanted. What did I want?”

You can feel the brutal bursting of a million girls’ dreams as Johnson notes simply, “Marriage, entered upon maturely, is the only life for most women. But it is a way of life, not a magic bag of goodies at the end of the road.”

The third person telling, the removed quality of her narration, her calm disengagement from her own propensity to strip all the window dressing away from the ideological frou-frou of marriage and motherhood is at once dignified, balanced, and riveting. Its dispassion is the very heartbeat of despair. A participant-observer in the bizarre social reality she describes, Johnson conveys without rancor the existentially isolated, restless feeling that my mother’s generation grappled with, and that Friedan wrote about when she quoted one of her subjects: “I’m a server of food and a putter-on of pants and a bed-maker, somebody who can be called on when you want something. But who am I?”

And Johnson might have added, “Why am I the only one?” Johnson starts off with the demographically inflected observation that women are cut off from their extended families and friends by the idealized nuclear family, with its ostensibly perfect evenings of popcorn and TV in PJs, but moves toward darker realities, including the impact of this existence on female consciousness.

Wives are lonelier than they have ever been.

* * *

We no longer call women who stay home with the kids “housewives”—unless we are seeking to at once put them down and sex them up, as with the Real Housewives of Virtually Everywhere franchise. Now they are “full-time mothers,” or “stay-at-home moms.” On internet chat boards like urbanbaby.com these women use the acronym SAHM. A recent uptick in their numbers, reported by Pew, had demographers intrigued and journalists scratching their heads and, quite often, missing the point. A 2014 Economist article, “The Return of the Stay at Home Mother,” noted that the number of stay-at-home mothers ebbed from 49 percent in 1967 to 23 percent in 2000, but then began rising steadily again. Poor and immigrant mothers who cannot justify the cost of childcare for menial wages are one part of this trend. But a quarter of the mothers who stay at home have college degrees (and then some).

The shift in language—from housewife to SAHM—suggests that where running a household was once a vocation, now motherhood is. And while the latter may seem “more important”—children are the future of our country and our entire world, after all, whereas a house is just a house—the social status of the woman who doesn’t work, despite our noisy insistence that “motherhood is the toughest job” and so on, has arguably never been lower.

Sure, today’s college-educated women have a degree of autonomy and self-determination that Johnson and her peers only dreamed of, and that required an entire second wave of feminism to engineer, through consciousness raising, lawsuits, and legislation. Thanks to Title IX, they played sports that were off limits to a previous generation. Now, as middle- and upper-income women who stay home with kids they have recourse to no-fault divorce, laws protecting them from workplace discrimination, and access to birth control and abortion.

And yet.

The educated woman who stays home now may face a measure of not only the longing and lack of fulfillment that Johnson and Friedan articulated, but also the awkward silence and turning away at a cocktail party—the lack of interest when she says she is a stay-at-home mother. She is in for a heaping helping of something relatively new: widespread cultural contempt. The Economist piece exemplified this socially sanctioned scorn when it referred to some women who stay home as “highly educated bankers’ wives who choose not to work because they don’t need the money and would rather spend their time hot-housing their toddlers so that they may one day get into Harvard.” The dismissive, judgmental sentiment, if not the precise wording, is commonplace.

Today, some women are more subject to certain forms of misogyny than they have ever been. Because in the post-World War II period, as competent Rosie the Riveters were being shoehorned into suburban domesticity by the G.I. Bill and the ideology of the nuclear family über alles, they were at least told, in so many ways, that their work in the home was important. The flourishing of home-economics courses, with their whiff of pre-professionalization, suggested that being a homemaker was a practice and an identity that mattered, something to learn and to be, proudly. If you did it right, you could save the family unit money. You could contribute, without participating in the labor force for paid work, to the financial health and well being of your household. There was a certain respect for the housewife, even as the very moniker relegated her to a second-class sphere: Her husband couldn’t do it without her.

And not infrequently, this led to a version—albeit a compromised one, easily eroded by forces outside the home—of equality under one roof. As Marlo Thomas told me when I appeared on her AOL webcast Mondays With Marlo, “I knew men who just handed their whole paychecks over to their wives. Their husbands might earn the money, but their wives were in charge of it.” It was a partnership of sorts.

And now? As I prepared to write a book about privileged motherhood and childhood on the Upper East Side, I came to think of the women I’d spoken with and befriended and mothered alongside—the ones I’d had access to because they didn’t go to offices after school drop off—as Glam-SAHMs, for Glamorous Stay at Home Moms. Like their ’50s and early ’60s counterparts, they live in a culture with relentlessly high standards of female beauty, and tend to their bodies, faces, and overall appearances carefully, frequently with stunning results. This is made easier by the fact that, unlike Johnson’s peers, many have delegated much of the domestic work—household management, organizing, cleaning, and cooking—to hired help.

The one thing the privileged mommies I studied were not willing to delegate completely was childcare. Often cut off from extended families, most depend at least in part on nannies to help them with the heavy lifting of motherhood, the schlepping across town, the playdate scheduling and supervising, the nose-blowing and the puzzle playing. And yet they stay home.

“I was offered my dream job. It really was perfect,” said more than one mother, telling me about her decision to stay home with her children. “I asked if I could do it part time and the answer was no. I asked if I could do part of the hours from home and they said no. I asked about flex time—some weekend hours, something—and the answer was no. So I decided to stay home with the baby.”

These women described their shift to stay-at-home motherhood as a choice, but a choice implies options. Work flexible hours while your child is in the care of loving, trusted caretakers—ideally in onsite daycare—or stay home with your baby and don’t work. That is a choice. No, the women I wrote about had been given what was clearly a false choice, even though the culture at large and even the women themselves often insist on believing otherwise. What kind of choice is it when your career as an attorney or investment banker demands that you stay at the office 60 hours a week or opt out of the workforce altogether? When a husband’s significant income gives a woman the “luxury” to stay home with her children, she’ll often feel compelled to choose that option.

As when Johnson penned her essay, we are in an interlude where our lack of vocabulary confounds us. If the wealthiest Glam-SAHMs still haven’t freed themselves from the captivity Johnson described, what does that say about everybody else? Perhaps, that women are as deceived today as we have ever been.

The Past Goes On Trial in North Carolina

“The history of North Carolina is not on trial here,” Butch Bowers, a lawyer for Governor Pat McCrory, told a court in Winston-Salem on Monday.

Pace Bowers, that’s precisely what’s on trial over the next two weeks. A group of plaintiffs—including the Justice Department, NAACP, and League of Women Voters—are suing the state over new voting laws implemented in 2013, saying that they represent an attempt to suppress the minority vote.

The new laws were passed shortly after the Supreme Court struck down a section of the Voting Rights Act that required some jurisdictions to seek approval from the federal government before altering voting laws. All of those jurisdictions had been found to have voting practices that disenfranchised minorities; most of them were in the South.

The new rules required a photo ID to vote; reduced early voting; ended same-day voter registration; banned the practice of casting ballots out of precinct; and ended pre-registration for teens. (The General Assembly later amended the photo-ID law, which had been the strictest in the nation, and it’s not being considered in the trial.)

Related Story

How North Carolina Became the Wisconsin of 2013

In many ways, this case is similar to other ones around the country over the past few years. There’s little serious dispute that these tools were more heavily used by black voters than white ones. The arguments have been rehearsed over and over: Minority voters tend to be poorer and less educated; it’s more difficult for them to take time to wait in long polling lines, making early voting necessary; they’re more likely to miss a registration deadline or changes in voting spots.

But McCrory and his fellow Republicans in the legislature argue that the rules apply equally to everyone in the state, and that they’re necessary to guarantee the sanctity of the vote. The argument offers an appealing simplicity, but the problem is that repeated efforts have failed to find evidence of widespread, or even somewhat common, voter fraud. As a result, the laws seem to be solving a problem that doesn’t exist—while going out of their way to make it more difficult for people, and especially people of color, to vote.

“This is our Selma.”But this case is different from other voting-rights cases for three reasons. First, it comes amidst a sweeping national debate about race, one that began with Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson and has continued through the massacre of nine black people in a Charleston church and South Carolina’s subsequent decision to take down the Confederate battle flag from its capitol grounds. In contrast to Bowers, the plaintiffs very much want to make this case about history. The NAACP’s slogan during the lead-up to the trial has been, “This is our Selma.” Disparate rates of voting, due to legal obstacles, were a central element of the pre-civil-rights South. The plaintiffs argue that North Carolina has picked up right where it left off in 1965 when the Voting Rights Act was enacted.

Second, the case is likely to have ripple effects nationwide. While members of Congress have discussed tweaking the Voting Rights Act to reinstitute preclearance in accordance with the Supreme Court ruling, there’s been no real progress, and that seems unlikely to change soon. A decision is “likely to happen and get a result faster than whatever Congress is able to do,” said Michael Gerhardt, the Samuel Ashe distinguished professor of law at the University of North Carolina. “As a result, if there are people who have been effectively disenfranchised, or voting blocs have been diluted, this remains their best chance.” On the other hand, if the plaintiffs fail, it could create more pressure to act on Capitol Hill, on the basis that the courts had failed to protect voting rights.

Third, North Carolina is a politically volatile state, unlike some of the other sites for recent voting-rights case, like solid-red Texas. The state voted for Barack Obama in 2008, but Republicans have since captured the governor’s mansion and the legislature and enacted a long list of conservative reforms. (Obama lost by about two points in 2012.) Some of those have been straightforward priorities for the right, like overhauling taxes and expanding gun rights, but others have notably involved race. The state’s decision to reduce unemployment benefits and reject Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act impact poorer, minority residents of the Old North State. Republicans also repealed the Racial Justice Act, a unique law allowing convicted criminals to appeal their sentences by pointing to racial disparities.In response, a huge grassroots movement arose, centered around protests called “Moral Mondays.” They were led by the Reverend William Barber, the outspoken and sometimes controversial head of the state NAACP. More than anything, the protesters have succeeded in showing the deep divisions in North Carolina. There’s a substantial and impassioned bloc of voters opposed to the conservative changes, but they’re also clearly a minority. And thanks to redistricting, it’s hard to imagine Democrats retaking control in Raleigh any time in the immediate future. The Moral Monday crowd points to the various reforms as a pattern of changes that target black citizens.

The Justice Department wants the federal district judge in the case, Thomas Schroeder, to rule not only that the effect of North Carolina’s new voting law is discriminatory, but that its intent is so clearly discriminatory that “preclearance” rules, requiring the state to seek federal approval for voting laws, should be reimposed after being removed by the Supreme Court decision.

That will be a tall order, Gerhardt warns. It’s not sufficient simply for plaintiffs to show that the laws have a disproportionate impact on minorities.

“It’s hard to show a systematic or deliberate attempt to suppress votes based on race.”“It’s hard to show a systematic or deliberate attempt to suppress votes based on race,” he said. “Their best hope is to throw a Hail Mary pass and make the claim, which outside the courtroom is not silly, but inside the courtroom is going to be much harder to prove.”

A second option would be for Schroeder to find that while the law is not a deliberate attempt to discriminate based on race, it still violates the Voting Rights Act by abridging minority voters’ ability to vote. In June, the Supreme Court upheld federal housing laws that ban practices that have a “disparate impact” based on race, even when there’s no intent to discriminate. That could offer some precedent in this case, even though it concerns a different statute, Gerhardt said.

The plaintiffs may face a tough battle with Schroeder, a conservative George W. Bush appointee who will decide the case, with no jury involved. They initially requested a preliminary injunction against the new laws prior to the 2014 election. Schroeder rejected the request, but the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed his decision. Then the Supreme Court reversed the circuit court, and while no reason was given, it’s speculated that the justices were wary of upending the election process so close to voting day. Schroeder, however, is unlikely to have the final word. Regardless of the outcome, the loser will likely appeal to the circuit court, and the Supreme Court may eventually decide to consider the case.

The 2014 election is likely to be central in the trial, and that could present a challenge for the plaintiffs. That’s because in the first cycle under the new rules, African American voting rates actually increased versus the last midterm election, in 2010. For advocates of the changes, that’s proof enough that the law doesn’t hurt black turnout. The plaintiffs reject that idea, noting that there was a close election for U.S. Senate and that civil-rights groups pushed particularly hard for registration and voting following the passage of the laws. They also point to some 11,000 who registered in the last 25 days before the election—voters who would have been able to cast a ballot under the old rules, but not the new ones.

One way or another, then, the result in the case is likely to be about history. The question is whether it’s recent history or more distant events that decide the outcome.

July 14, 2015

Where Iran Is Considered a Top Threat—and Where It Isn't

There’s only one country in which Iran’s nuclear program is considered the gravest threat in the world today. Not surprisingly, it’s the country whose prime minister just denounced the nuclear deal announced Tuesday between Iran and six world powers as a “a bad mistake of historic proportions.”

In Israel, according to a 40-nation Pew Research Center survey released on the same day as the nuclear accord, 53 percent of respondents said they were “very concerned” about the Iranian nuclear program, compared with 44 percent of Israelis who said the same about ISIS and 28 percent who chose global economic instability. When respondents were asked to identify their level of concern about seven global issues—from “not at all concerned” to “very concerned”—in no other country polled was Iran the greatest worry. Only in three of 40 countries did more than 50 percent of respondents cite Iran as a top concern: Israel, the United States, and Spain.

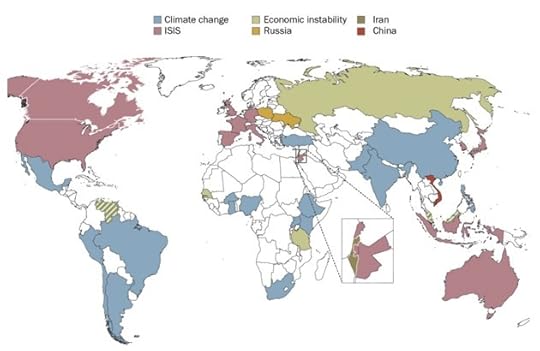

The Pew report doesn’t just chart the geography of alarm about Iran amid international efforts to restrict that country’s nuclear capabilities. It also reveals notable regional trends in what people consider threatening. Concern about climate change is most pronounced in Latin America, Africa, and Asia; fear of ISIS is most evident in North America, Western Europe, Australia, and the Islamic State’s neighbors in the Middle East. Economic instability is a secondary concern in many places, while cyberattacks tend to be downplayed as a danger throughout the world.

Top Perceived Threats Around the World

Colors represent the greatest concern in each country surveyed. In Malaysia and Venezuela, both climate change and economic instability were top concerns. (Pew Research Center)

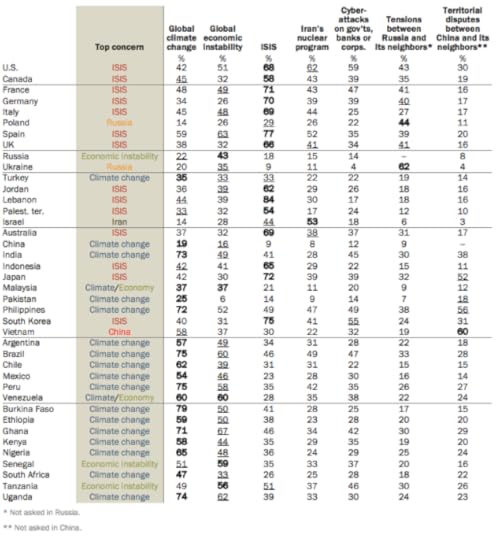

Colors represent the greatest concern in each country surveyed. In Malaysia and Venezuela, both climate change and economic instability were top concerns. (Pew Research Center) Percentage of Respondents “Very Concerned” About ...

Bolded figures note the top concern in each country. Underlined figures note the second-greatest concern in each country. (Pew Research Center)

Bolded figures note the top concern in each country. Underlined figures note the second-greatest concern in each country. (Pew Research Center) The study comes with several caveats. Pew only surveyed 40 countries, leaving out not just most of Africa but also Persian Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia that consider Iran an adversary, and where public concern about the Iranian nuclear program may be more aligned with views in Israel. Rather than posing an open-ended question, the pollsters asked respondents to report their levels of concern only about the following international threats: global climate change; global economic instability; ISIS; Iran’s nuclear program; cyberattacks on governments, banks, or corporations; tensions between Russia and its neighbors; and territorial disputes between China and its neighbors. And it’s not as if concern about Iran is confined to just a few countries. In 22 of 40 countries surveyed, 30 percent or more of respondents said they were very worried about the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program.

But political leaders respond to public opinion, and the foreign policy they pursue is a product of prioritizing. Iran has been engaged in talks over its nuclear program with six world powers: China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In none of these six countries is the Iranian nuclear program the top geopolitical concern, according to the Pew report. In France, Germany, the U.K., and the U.S. (barely), ISIS is considered the gravest threat. In China, it’s climate change. In Russia, economic instability.

All this has implications for the fate of the Iran deal. As my colleague Peter Beinart has noted, there’s a chance economic pressure on Iran would decrease, rather than increase, if the U.S. Congress were to reject the current agreement and impose new Iran sanctions in an effort to extract additional concessions from its longtime adversary. That’s because European and Asian countries might respond to the U.S. move by withdrawing support for international sanctions against Tehran. Here’s what Beinart wrote in April:

[I]f the United States walks away from a deal that European and Asian governments support, those governments will not indefinitely maintain a sanctions regime that lacks domestic political support and costs them money. Last year, a report by the European Council on Foreign Relations warned that “those [in the United States] blocking implementation of a final deal … could endanger the international consensus backing sanctions against Iran.” If Congress torpedoes a deal, the report predicted, Europe might react “by easing its unilateral oil embargo against Iran.” In addition, “China and Russia … may become more sympathetic towards Iran’s position and see an opportunity to further advance their own interests at the expense of the US.”

China, in particular, has a history of strong economic ties to Iran, a massive thirst for oil, and little interest in doing America’s bidding in the Middle East. If the United States walks away from a deal that Beijing has endorsed, it’s only a matter of time until China imports large quantities of Iranian crude. Chinese impatience is already starting to show. Beijing imported 30 percent more oil from Iran in 2014 than it had in 2013. As the International Crisis Group’s Ali Vaez observes, “The high-water mark of international sanctions is already behind us.”

In the coming days, Israeli leaders will likely continue to condemn an agreement with an Iranian regime that they believe poses an existential threat to their country. But their criticism may find few echoes elsewhere in the world.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower