Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 387

July 20, 2015

Wilco's Star Wars Is a Random Act of Love

Why is the new Wilco album called Star Wars, and why is its cover a painting of a fluffy white cat? Here’s hoping that we never really find out. “I cry / at a joke / explained,” Jeff Tweedy sings four songs in, his voice a vampy impression of Bob Dylan’s as the band lays down a fuzz-rock flamenco backing. The rest of the song is a barrage of riddles: “It's a staring contest in a hall of mirrors / I sweat tears, but I don't ever cry.”

Related Story

What Yankee Hotel Foxtrot Said

The song, “The Joke Explained,” is a worthy entry in Wilco’s long catalogue of songs that capture the idea of life as impossible to capture. Whether we’re all speakers speaking in code or one-way radios transmitting nonsense, Wilco’s adventuresome yet consistently tuneful music says that it’s normal and sometimes glorious to misunderstand and be misunderstood. As they’ve kept chugging into middle age, this core artistic premise has often been obscured by the dismissive description “dad-rock,” factually accurate though it may be (after all, Tweedy recently put out a record with his teenage son). Star Wars, the band’s ninth album, released by surprise and for free on the Internet, reminds that Wilco aren’t just reliable, safe rockers; they’re some of the most generous experimentalists to ever pick up guitars.

A crackling 33-minute trip, the album has way more in common with ‘90s indie pranksters like Pavement than it does with the Americana scene that Wilco’s long been associated with. While a few of these songs won’t stick in listeners’ heads for long, all of them feature a delightful sonic twist of some sort. You can tell what mood they’re in within a second of turning on the opener “EKG,” an instrumental whose migraine-frequency guitar stabs eventually lock onto a kraut groove that suggests liftoff into another world. In that world, we get a tune like “More…,” which sounds a bit like Tom Petty’s “Free Falling” except for the fact that its riffs pan between ears and the song drowns itself in distortion before the three-minute mark.

There’s precisely one track that sounds like the stereotype of a Wilco song—“Taste the Ceiling,” featuring acoustic strum, some soloing, and a tempo suited for lo-fi rom-com montages. It’s fine. Far more wonderful is the closer, “Magnetized,” which uses soft organ pulses and a theremin to portray love as something that warps a person as surely as an electromagnet warps a TV set. Another would-be ballad, “Where Do I Begin,” interrupts its lullaby for a punk-psychedelic eruption in its final seconds. I wish the band had rode that noise wave longer, maybe adding a soaring chorus on top of it. But doing so might have defeated the point of the album—ambitions low, surprise factor high.

The most fully formed thing here is “Random Name Generator,” which surges and struts as Tweedy riffs on the song title—his latest metaphor for the universe’s insane incomprehensible beauty. “I change my name every once in a while,” he sings with a touch of hair-rock hamminess, “A miracle every once in a while.” It’s impossible to know what he means for sure, but when I hear the song, I think about how this low-stakes, playful freebie of the album fits in with Wilco’s many reinventions over the years. Fans, at least, should be able to appreciate it deeply. “Your prayers,” Tweedy once sang, “will never be answered again.”

A Cuban Flag Rises in the District of Columbia

On Monday, the State Department announced that “the U.S. Interests Section officially became U.S. Embassy Havana” which, in non-diplospeak, means that America and Cuba have formally restored diplomatic relations. In Washington, D.C., Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez re-inaugurated the Cuban Embassy 54 years after it closed.

The reestablishment of ties between the U.S. and Cuba comes weeks after President Obama announced a “new chapter” between the two countries and an imminent plan to reopen the embassies. Diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba have been frozen since January of 1961—seven months before the president was born.

The State Department released a video of the Cuban flag being placed among the row of foreign banners at the department’s Foggy Bottom headquarters, in the space between the flags of Croatia and Cyprus.

The diplomatic thaw between the two countries started last December when Obama announced, at the urging of Pope Francis, that the U.S. would pursue normalization of relations. Since then, industries ranging from Major League Baseball to Carnival Cruises have jumped at the possible business opportunities. Airbnb and late-night television have already gotten a head start.

American public opinion polls comfortably favor normalizing ties with Cuba. Still, Monday’s milestone was not universally welcomed. Chronicling his opposition for CNN, Marion Smith of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation noted a “cruel coincidence” in the timing. “In 1959, the same year that Fidel Castro's forces proclaimed victory in Havana,” he wrote, “Congress designated the third week of July as Captive Nations Week to express America's solidarity with citizens trapped under oppressive communist regimes.”

As Reuters reported, the response at the ceremony on Washington, D.C.’s Embassy Row also gestured at the complexity of the history as well as the issues that remain unresolved between the two nations. “As the flag was slowly raised, there were competing chants from the crowd outside the gates. ‘Cuba si, embargo no!’ shouted one group. ‘Cuba si, Fidel no,’ yelled a much smaller group.”

The Evolution of TV's ‘Very Special Episode’

Before Cast Away and Captain Phillips, before he waxed inspirational over boxes of chocolates in Forrest Gump or flirted online with Meg Ryan in You’ve Got Mail, Tom Hanks was drunk Uncle Ned on the ’80s sitcom Family Ties. At first, the show played his liquor-fueled antics for comedy, setting the audience at ease—until one episode with an emotional scene in which he backhanded his nephew Alex, played by Michael J. Fox, across a coffee table in front of his family. Chastened by the outburst, Ned joined Alcoholics Anonymous, and audiences learned a valuable lesson about alcohol abuse. When it aired in 1984, “Say Uncle” captured the essence of an expository template now near extinction on TV: the very special episode.

Related Story

‘Glee’: The Primetime After-School Special

From child molestation on Diff’rent Strokes to Will’s emotional “deadbeat dad” rant on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, the very special episodes of ’80s and ’90s sitcoms introduced young viewers to intense, real-world issues. Like carefully crafted public service announcements, they took characters audiences laughed with and cared about—Theo Huxtable, D.J. Tanner, Zach Morris—and put them in close contact with harrowing life events to send a moral message. To sophisticated modern viewers wary of soapboxes, very special episodes are now dated relics that feel excessively earnest and painfully overt. Consequently, after being a small-screen staple for years, this often awkward model of entertainment is nearly nonexistent. And yet while the device itself may be dead, the socially conscious objective at its core has evolved, and lives on in a spate of subtle, cleverer TV series.

In their time, very special episodes were the modern equivalent of Grimm’s Fairy Tales: a sitcom formula designed to foster dialogue, with a serious tone that helped parents talk to their kids about drugs, sex, and violence. VSEs trace their roots back to the Norman Lear sitcoms of the ’70s, such as All in the Family and Good Times, which directly tackled social issues for the first time. Eventually they grew into something more clumsy and predictable. “I think that might have had to do with cynical marketing opportunities as much as a desire to serve the public,” says Arthur Smith, an assistant curator at the Paley Center for Media Studies. “[Very special episodes] were always scheduled for sweeps weeks, and so clearly had ratings expectations.”

Emily Nussbaum, the TV critic for The New Yorker, says that while very special episodes tend to be artless, condescending, and simplistic, their greater influence is harder to assess. “I do wonder if some VSEs had social impact,” she says. “Just because something is bad art doesn’t mean it’s not effective.” Take, for example, a story line of Growing Pains from 1989, where Carol Seaver’s new college-age boyfriend, Sandy (played by the future Friends star Matthew Perry), drives drunk, crashes, and ultimately dies from the injuries he sustains. After the episode ran, “ABC officials in New York reported ‘several dozen phone calls Wednesday night after the show aired from viewers lauding the drunk-driving theme,’” according to The Los Angeles Times. Parents called into the network to express their approval. Sandy may have died, but he did so off-screen, and Carol survived to learn a valuable lesson after a stern talking-to by her father.

This was the hallmark of the very special episode: The main characters beloved by viewers would inevitably avoid serious harm. The dangers posed by story lines were more threats than actual occurrences, and on the occasion that bad things did happen, they usually happened to ancillary characters whom audiences cared less about. This selective meting of moral justice kept lessons from becoming too morbid, while still allowing episodes to serve as cautionary tales.

This gentle approach, however, was before shows like Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, and American Horror Story. In comparison to the darker television of the 21st century, the squeaky-clean endings of very special episodes now seem anodyne and absurd. Given that The Walking Dead, which kills off main characters without batting an eye, is the second-highest-rated show among 9-to-14-year-olds, it’s fair to assume teens no longer have the patience for a tender lecture about eating disorders from Uncle Jesse. With realism so visceral and information so accessible, the entire methodology of very special episodes seems naive and anachronistic.

“Irony has become the default pop-culture sensibility,” says Smith. “Earnestness can’t survive. It’s less exciting if a kid from Modern Family is drinking at a party when over on another channel Walter White is melting someone in a bathtub.”

With realism so visceral and information so accessible, the entire methodology of very special episodes seems naive and anachronistic.It’s important, however, to distinguish between the moral lessons of very special episodes and the packaging of those lessons. Today, their melodramatic tone comes across as trite, in the way that special effects from even 10 years ago now seem laughably unsophisticated. Art, just like its technical elements, tends to get more polished over time, and so what was once weighty material becomes ridiculous: The gravitas of “The Bicycle Man” episode of Diff’rent Strokes, in which the owner of a local bike-repair shop tries to coerce pre-pubescent Arnold to take off his clothes, was at the time sincerely scary. Now the episode is parodied on Family Guy.

When the episode of Saved By the Bell in which Jessie gets addicted to caffeine pills first aired in 1990, it tried to make a profound point about substance abuse. Now her “I’m so excited” breakdown is a meme. The very special episode format no longer resonates—it’s too neat, too tame, and too clichéd. “The very special episode—a simpler package for progressive ideas—is gone,” says Nussbaum, “but what we have is more varied and mostly better ways of expressing political ideas in comedy.”

One contemporary sitcom that overtly channeled the VSE format was the recently wrapped high school aca-dramedy Glee. The Fox hit lured in young viewers with renditions of pop songs, while its story lines took on issues like bullying and LGBT relationships. The show sustained a self-deprecating edge, while maintaining an air of authenticity by employing real actors—who had Down’s Syndrome, were gay or ethnically diverse—who could accurately represent the issues addressed. “It was very up front with what it was trying to say about tolerance and acceptance,” says Smith. “It did it in a very fizzy, 21st century-irreverent, tonally adventurous way, which kept it from being marginalized as strictly moralizing.”

But later in its run, Glee became less oblique in its messaging, asserting a tone that was at times inspired, but frequently felt overbearing. In 2013, less than four months after the Sandy Hook shooting, Glee aired an episode titled “Shooting Star.” The show opened with a disclaimer: “This episode of Glee addresses the topic of school violence. Viewer discretion is advised.” In it, any semblance of comedy was immediately shed as the sound of gunshots in the hall forced the members of New Directions to seek cover in the choir room. But in line with the VSE form, no characters were actually injured and, after much suspense, it was revealed that the gun was fired by accident.

The VSE homage was to the show’s detriment: The episode was met with a fair amount of derision from critics. Lauren Hoffman of Vulture wrote, “It seems far more respectful to point to real stories with real consequences as a means of generating awareness, rather than making up a story where everything turns out just fine in the end.” The message fell flat and Glee’s viewership continued to decline. Perhaps a different approach, in which the show either embraced the comedic energy that propelled it through its first two seasons or committed to a darker ending, would’ve helped preserve its relevancy.

“The very special episode—a simpler package for progressive ideas—is gone,” says Nussbaum.It was the fundamental formula of VSEs to temporarily drop the comedy aspect of sitcoms to deliver a serious message. Today that feels disingenuous—an about-face that makes no sense. Instead, shows that are successful use comedy as the vehicle of delivery, employing satire to reflect a fun-house mirror on the absurdity of society. Just think of The Simpsons, South Park, and The Daily Show. Even relatively recent episodes of South Park (such as “The Hobbit,” which dealt with body image issues among young girls, and “You're Getting Old,” which dealt with divorce and depression) effectively juxtapose laughs with heavy-hitting issues. During a recent appearance on The Daily Show, Senator Al Franken told Jon Stewart, “You’ve taken this platform, and with your hard work, judgment, and intellect have engaged a generation of young people in public policy and politics.”

Though the aforementioned programs aren’t necessarily traditional family-friendly sitcoms, their function in society—employing humor as a mechanism to convey morals to young people—can be traced back to the tradition of very special episodes. In fact, the past year has seen a renaissance of major network family sitcoms, such as Black-ish and Fresh Off the Boat, in which social issues are woven seamlessly into the comedic fabric of the show’s narrative. “They don't do anything as cheap as a ‘now let's stop being racist’ plot,” says Nussbaum, “but they do explore messages about family and identity.”

It’s the subtlety of humor that makes complicated issues more palatable—addressing controversy with an appropriate balance of gravity and hope. Comedy can openly acknowledge that things aren’t okay, but through a filter that makes the world’s woes seem like less of a lost cause and possibly even incites action. “These shows have ideas built into the premise,” Smith says. “If you’re just starting with that agenda, then no particular episode is going to feel particularly didactic or like it’s trying to be ‘very special.’”

In any case, the very special episode is now more tombstone than touchstone. But its existence was a necessary step in the growth and development of the more sophisticated programming audiences can see today.

True Detective Season Two: Pimps, Vultures, and Plastic Surgery

Each week following episodes of True Detective, Spencer Kornhaber, Sophie Gilbert, and Christopher Orr will discuss the murders and machinations depicted in the HBO drama.

Gilbert: To start on a positive note: “Other Lives” was a huge improvement on last week’s episode. The plot now seems to be heading somewhere, the dialogue was more like words people might say to each other (and less like mystical fortunes dispensed by Zoltar at a fairground), and there was even a moment of levity—maybe the first of the season—when Ani attended her mandatory sexual-harassment seminar and got some kicks out of disrupting the assembled group of perverts by talking about penises. (“Let her share, man.”)

Related Story

True Detective Season 2: Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang

The bad: Lera Lynn continues to play music to a crowd of three people in the only California bar you can openly smoke in, events are still convoluted to the point of Donnie Darko, and the enemy won’t quite reveal itself, in the words of Frank. After the climactic shootout at the end of episode four left everyone apart from Paul, Ani, and Ray dead in the street, the episode jumped two months ahead, possibly to avoid too many obligatory scenes of the traumatized trio drowning their PTSD in the bottom of a whiskey bottle (I, for one, am grateful, but with only three episodes left to wrap this up, it’s more likely there just wasn’t time). Ani has been sent to work in an evidence lockup. Paul is working a desk job investigating insurance fraud. Ray has shaved off his mustache just as we’d gotten used to it and is now working full-time for Frank, who’s sold his mansion and moved to a smaller place in Glendale.

Given all this, you might assume the dream team of Bezzerides, Velcoro, and Woodrugh has been disassembled permanently, but conveniently for plot’s sake, the attorney general of California, Richard Geldof, is running for governor. Geldof previously was hellbent on having Paul investigate Caspere’s murder to dig up dirt on Vinci PD and the mayor’s office; but now the state’s attorney Katherine Davis believes that Geldof’s newfound war chest is a sign of collusion between him and the town of Vinci, and so wants to reassemble the dream team to find out what really happened to Caspere, who was involved, and why.

Herein lies the central problem with True Detective season two, which is that huge complex plot points are dispersed in conversation in a matter of seconds, while other matters (the Semyons’ ability to have children, Frank’s money troubles, Ray’s relationship with his son) are essentially beaten to death by Pizzolatto like Rick Springfield delivering unwanted psychological evaluation. Yes, establishing character complexity is important. But would it be worth sacrificing a scene or two of Frank and Jordan discussing their willingness (or not) to adopt in order to explain a little more effectively what’s actually happening? Or are we supposed to just buckle up and ride the metaphorical carriage until it runs off the rails?

There were a number of big reveals in this episode, but the one that seems to finally be carrying the show to a conclusion was the news that the long hinted-at sex parties involving expensive call girls and powerful men have been run all along by Tony Chessani (the mayor’s son) and Ben Caspere, with some help from Dr. Pitlor, who provides the women with plastic surgery. Caspere also had a sideline using the girls to establish blackmail files on all the men involved including (possibly) a California state senator (echoes of True Detective season one). Blake, Frank’s blond, Patrick Batemanesque assistant, is also involved—revealed after Ray followed his car and saw him greeting Pitlor and Chessani with three blonde call girls. And there was some kind of development regarding a waste-management company, which has been helping plant heavy metals in the ground to make its land seem less valuable.

Would it be worth sacrificing a scene or two of Frank and Jordan discussing their willingness to adopt in order to explain a little more effectively what’s actually happening?But the development that shook Ray the most was the news that his wife’s rapist was arrested several weeks ago in Venice, which implies quite strongly that whomever Frank persuaded Ray to murder in retribution for her attack wasn’t actually the man who raped her. His wife, horrified by the fact that Ray had lied to her for all these years about offing the guy who assaulted her, and by what happened to their marriage because of it, is suing for a paternity test, which will presumably prove that Chad isn’t his son. And Ani and Paul, following a tip to the address where the missing girl from episode one last called her sister from (an address Caspere’s GPS had also visited), discovered a torture room in a woodshed covered in arterial blood and surrounded by vultures.

What does all this mean? It seems unlikely at this point that the supernatural elements hinted at in the first few episodes will be realized in some grand occult reveal, which is a bummer. Yes, the birds again, and yes, the “commune,” and yes, Ani’s dad still might be involved, but it’s more likely that the season is simply about the municipal corruption involved in a California town with fewer than 100 residents, and the various ways in which criminals and established politicians alike have enabled the co-option of land that public transportation might soon make more valuable. After season one, with its ritual murders and sinister symbols and crazy incestuous siblings and drug massacres and kidnapped children, you could be forgiven for being perhaps the teensiest bit disappointed with this. I know I am.

Chris and Spencer, what did you make of Ray’s brutal beatdown of Pitlor, and Paul’s fight with his mother, and Ani’s apparent commitment to going undercover? Why was the man up north dressed like Jesus and carrying a cross? What’s on the hard drive Ray’s been tasked with finding? Why is the title music suddenly different? And why, why, why, does Pizzolatto keep making Frank say thinks like, “It’s like blue balls. In your heart”? Poor guy’s got enough to deal with without it sounding like he’s doing pornographic slam poetry.

Orr: I agree that this was a major improvement, Sophie. After an episode of stasis and soap opera culminating with a wildly over-the-top gunfight, tonight we saw some genuine signs of plot progression. There were a few groan-worthy moments, but also several that made me feel more engaged in the show than I have in at least a couple episodes.

Let me start with one (enormous) quibble. Pizzolatto was pretty clearly using last week’s insane bloodbath in two ways: first, to try (very unsuccessfully) to demonstrate that he could outdo the classic, single-shot scene with which his former collaborator Cary Joji Fukunaga closed episode four last season; and second, to serve as a narrative hinge for this season, like the backwoods shootout with Reggie Ledoux in the last episode five. As I wrote then, “One story has concluded, and another is beginning to unfold.”

The problem is that the (apparently case-breaking, and definitely life-changing) Ledoux gunfight had a body count of two, both of whom were redneck criminals. Last week’s body count was more like—hell, I doubt you could even tally it without an itchy pause finger and an abacus. But it had to include at least half a dozen cops and a dozen or more innocent civilians. This would be a huge story, the kind involving not just gubernatorial candidates, but presidential ones (plus presumably the sitting president). It’d be a touchstone for the usual national debates regarding police violence and gun control. No one—no one—would care any more about Ben Caspere or missing persons, or anything else True Detective is ostensibly about. We’d have to segue into House of Cards (or maybe Veep) material.

Added to that, the only survivors of the across-the-board massacre were: the Ventura County detective heading the operation, who a) was under investigation for sexual harassment and had been relieved of regular duty, and b) had ignored warnings by superiors that she should wait for a state task force to arrive; a state trooper who a) was also under investigation for sexual harassment and relieved of regular duty, and b) was possibly implicated in war crimes committed by the mercenary force he used to work for; and, finally, a Vinci detective who was under investigation by the state for pretty much every crime that exists up to and including murder. The idea that any of them would ever again carry a badge or firearm is ludicrous. Can you imagine the outcry from relatives of the civilian victims? Ani, Paul, and Ray would be lucky not to be looking at serious prison time. You can’t throw a catastrophe of that magnitude into the show and then say, “two months later,” and pick up the story more or less where you left off.

I agree with you, Sophie, that overall there was probably less bad dialogue than in some prior episodes, but some of the dialogue was so bad it almost made up for it. I was still furiously scribbling down Frank’s line about how his enemy “stymies my retribution,” when he sprang that all-timer you quoted: “It’s like blue balls, in your heart.” If Blue Balls In Your Heart is not the name of at least six college bands by week’s end, I say we scrap the whole higher-education system.

I think one of the lessons of this season so far is that you can put over-articulated mumbo-patter into the mouths of designated weirdos—Rust Cohle last season, Mayor Chessani and Dr. Pitlor this one (I kinda loved the latter’s profoundly ill-advised line to Ray: “Your compensatory projection of menace is a guarantor of its lack”)—but it’s a total disaster when you give it to a relatively normal, working-class hood like Frank. “I was born drafted on the wrong side of a class war”? Umm, no. And unlike you, Sophie, I was also not a fan of Ani’s “big dicks” scene. I agree the show needs more humor. But this joke was (so to speak) a limp one.

That torture hut out in the woods of Guerneville didn’t make a lick of sense, but it did supply a jolt of the creepy horror that was so crucial to the first season of the show.And as long as we’re on the subject of sexual dialogue, can I say that just about the only thing I’d like to watch less than another fertility/adoption discussion between Frank and Jordan is another fight between Paul and his mom? She says that if she weren’t so big-hearted, he “coulda been a scrape job.” He retorts that she’s a “poison cooze.” Someone get Hallmark on the line. They’re missing Mother’s Day gold here.

But on to the good stuff. As long as I’m offering quotes, I should give a shout out to Ani’s crucial line: “What do we keep hearing about? Escort parties? Powerful men?” Amen, sister! This is exactly the question I’m confident every True Detective viewer has been asking for at least three episodes now. Finally, we seem to be getting a little progress on this front. But that doesn’t mean I don’t still want to recommend a TD drinking game in which everyone has to take a swig at each mention of sex parties “up north.” Spencer, you’re a Southern Californian (I’ve only lived in the Bay Area): Do people really use that phrase all the time?

In any case, that torture hut out in the woods of Guerneville didn’t make a lick of sense, but it did supply a jolt of the creepy horror that was so crucial to the first season of the show and has thus far been sorely missing from the second. I’m still disappointed that Pizzolatto decided to dispense with the whole “secret occult history of the U.S. transportation system” that he’d originally intended as a frame for this season. But even a few garden-variety psychopaths would move the series away from being a straightforward police procedural (which it’s very bad at) and toward the kind of gothic drama at which it mostly excelled last year.

Also: What the hell’s going on with (the late) Teague Dixon, Ray’s old drunken, lazy partner? (I basically like to think of him as Pizzolatto’s “ode to Buzz Meeks.”) A couple of episodes ago, we saw him surreptitiously taking photos of Paul. At the time, it seemed like he might be doing dirty work for Vinci PD’s shifty Lieutenant Burris (neatly played by James Frain). But when Burris showed up on Ray’s doorstep asking questions about Dixon, it seemed to complicate that scenario. And Dixon’s knowing about Caspere’s missing jewels before they showed up in the safe deposit box is a nice little mystery. It may well turn out these questions are more interesting than their solution, but for the moment count me intrigued.

My favorite development of the episode though—one of my favorite developments this season—was the discovery that Ray killed the wrong man when trying to avenge his then-wife’s rape. I particularly liked the way the revelation unfolded. First, Ray wondered why his wife was so angry at him during the custody hearing. Second, he learned that her long-ago rapist had been caught, with the (I think) assumption that she was furious with him for killing an innocent man. Third, they talked and it became clear that, far from holding him responsible for murder, she thought he’d just made the whole thing up in order to impress her. Fourth, he realized that Frank had set him up. And fifth—well, for that we’ll have to wait and see how his visit to Frank’s humble new abode plays out.

That is, if I can force myself to watch another episode, given the “scenes from next week” revelation that Ani is going to go undercover as an upscale hooker at one of the sex parties we’ve been hearing so very much about. Really? Pizzolatto seemed to take to heart critiques regarding the feeble female characters of season one. And while there have been disappointments so far this season—Kelly Reilly has been given a lot less to do than expected as Jordan; and Rachel McAdams’s Ani has bordered on a caricature of masculinity, but with ovaries—the idea of the show’s tough female cop having to pour herself into a slinky gown to act as sex bait is lame on another level altogether. I’m not sure, but I may have just barfed up an episode of Silk Stalkings. Let’s all hope there’s room under that dress for her to conceal at least a couple knives.

A few last observations:

If we must have deranged shootouts with mass civilian casualties, can they at least take place in the bar, where that impossibly tedious melancholy singer might plausibly be caught in the crossfire?

I’m sorry, but there’s no way Dr. Pitlor would be reading Carlos Castaneda’s A Separate Reality. The dude would have memorized the book verbatim 40+ years ago.

‘There's No Real Fight Against Drugs’

The slight man at the breakfast table seemed more like an evangelical minister than someone who once brokered deals between Mexican drug lords and state governors. He wore a meticulously pressed button-down, a gold watch, gold-rimmed glasses, and a gold cross around his neck. His dark brown hair was styled in a comb-over. And when his breakfast companions started to tuck into their bowls of oatmeal and plates of salmon benedict, he cleared his throat and asked for a moment of silence.

“Would you mind if I say grace?” he asked.

The gathering last week at Le Peep café in San Antonio would seem unusual almost anywhere except south Texas, where Mexico kind of blends into the United States—and so does the drug trade. Seated next to the cartel operative was a senior Mexican intelligence official. And next to him was a veteran American counternarcotics agent. They bowed their heads for prayer and then proceeded to talk a peculiar kind of shop.

Related Story

A Drug Lord's Infuriating, Inevitable Escape

A few days earlier, Mexico’s most powerful drug trafficker, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, had escaped again from one of that country’s maximum-security prisons. No one in this deeply sourced group was surprised. Nor were they particularly interested in the logistical details of the escape, although they clearly didn’t believe the version they’d heard from the Mexican government.

They were convinced it was all a deal cut at some link in the system’s chain. Our breakfast minister even thought that Chapo had likely walked out the front door of the jail, and that the whole tunnel-and-motorcycle story had been staged to make the feat sound so ingenious that the government couldn’t have foreseen it, much less stopped it.

Such an outlandish notion may not be surprising to anyone who knows anything about Mexico. But as someone who lived there for 10 years, and reported on the country almost twice that long, what surprised me were the men’s theories on why anyone in the Mexican government would have been interested in such a deal. Perhaps, I wondered aloud, Chapo had possessed information that could have incriminated senior Mexican officials in the drug trade and, rather than try him, they had agreed to turn a blind eye to his escape?

The heads around the table shook back and forth. Chapo, they believed, had been thrown back into the drug world to—wait for it—restore order. Things have gotten that crazy.

“When I first heard the news, I thought this is either a good thing or a bad thing,” said the cartel operative. “Either this is a sign of how far things in Mexico are out of control. Or this shows that the government is willing to risk a certain amount of international embarrassment in order to restore peace for Mexican people.”

Surely I’d been out of Mexico too long, I told the table. How could anyone believe that Chapo’s escape would be good for public security?

They pointed to what’s been happening in his absence. The levels of drug violence in Mexico have begun to surge. An ascendant cartel, known as Jalisco Nueva Generacion (the New Generation Jalisco), has launched breathtaking attacks against security forces and public officials. Led by yet another ruthless killer named Nemesio “El Mencho” Oseguera Cervantes, the cartel has set up armed roadblocks to search cars driving into and out of some of the most important cities in central Mexico, in order to keep out its rivals. And when authorities have attempted to stop the organization’s members, they’ve fought back with some serious firepower. A spectacular rocket attack earlier this year downed a military helicopter, and a rampage against Mexican police left 15 officers dead in a day.

Chapo, they believed, had been thrown back into the drug world to—wait for it—restore order. Things have gotten that crazy.Chapo, my breakfast companions said, was forged in the early years of the drug war. He was old-school. And for all his lunacy and willingness to do whatever it took to build his empire, he had been a kind of mitigating force—killing when he was betrayed, but staying away as much as possible from attacks against the government as long as the government allowed his business to operate. If he were allowed to get back to business, the breakfast bunch said, he’d take care of El Mencho—most likely in a spate of violence that, while painful, would be quietly treated by Mexican authorities as a necessary evil. And whichever cartel leaders remained standing would be much weakened.

“Mexico’s security apparatus is simply not ready to combat organized crime,” the intelligence official said.

There was more than 75 years of combined experience in the trenches of the drug trade at the table. As for the ins and outs of the fight against it—now in its fourth failed decade—they knew as well as anyone that no cynicism is too great. And no deal too unimaginable.

“The real problem isn’t just the flow of drugs,” said the cartel operative. “It’s the fight against drugs, because everyone gets dirty in the fight.”

While the operative, who’d been neck deep in the drug trade for more than 30 years, went to the restroom, the rest of the table talked about how he was a living case history of what’s possible. He had landed in Texas first as a fugitive, then as an outlaw. Leaders of the Zetas cartel, who pioneered the beheadings that have become a common feature of Mexico’s gory drug war, had accused him of stealing millions of dollars. They had already killed his brother and displayed his body on a busy street near the U.S. border. When the operative arrived in the United States, he was arrested by U.S. federal agents on money-laundering charges. He was released as part of a plea deal after serving two and a half years in prison, and forfeiting—the veteran agent turned to me and mumbled the figure under his breath—some $5 million.

“You know the Mercedes Sosa song that says, ‘Change, everything changes,’” the ex-con said, as he returned to the table. “I love that song. Everything changes, so why can’t I?”

The Mexican intelligence official, a barrel-bellied man with droopy jowls and short, curly, salt-and-pepper hair, said south Texas was full of men like the reformed operative. He ought to know, because he’s brought a lot of them there. While his day job keeps him incredibly busy in Mexico, he’s kept his wife, ex-wife, and children in Texas, where it’s safer and where he makes a living secretly collaborating with Washington’s drug war. The U.S. government makes it a rule not to talk about such things, but it’s an arrangement that is not uncommon for Mexicans who have worked as high-value informants. The official has helped broker deals that have allowed numerous Mexican drug traffickers or corrupt elected officials to surrender to U.S. authorities for prosecution and/or cooperation. One of his most recent negotiations, he said, had taken place in Culiacan, the capital of Chapo’s home state of Sinaloa, and involved one of the cartel leader’s sons, Alfredo. I gave him a look of disbelief. In my years of covering the drug war, I’d seen numerous classified reports that described such meetings. But Chapo’s son? Seriously?

“You’re thinking too much like an honest person,” he told me. “The United States can make deals,” the official said. “In Mexico, there is no such thing, at least not officially.”

“I talked to a priest about this. He told me to look for the lesser evil. And that’s what we do.”He shrugged off the criticism from U.S. officials and the nationalistic denials from Mexican officials following Chapo’s escape as just a lot of predictable posturing. To him, the battle lines in the drug war have never been as clear-cut as politicians claim. There are instead shifting alliances in which the U.S. government, like the Mexican government, finds itself fighting against a certain bad guy one day and alongside him the next. So when U.S. officials point fingers at their Mexican counterparts as if Washington has never cut a deal with a drug trafficker, the accusations seem as hollow to people in his line of work as the Mexican government’s insistence that Chapo acted without high-level help.

“There’s no real fight against drugs,” he said. “It’s all a perverse game of interests.”

The veteran American agent, with beefy arms and a 1980s-era, Erik Estrada haircut, chimed in. “A lot of people ask me, ‘Here you have a guy killing people, torturing people, and beheading people. How can you talk to a guy like that and take information from him?’ I talked to a priest about this. He told me to look for the lesser evil. And that’s what we do. We work with the lesser evil to get the larger evil.”

He ticked down the list of violent drug traffickers whom the United States has alternately treated as friend and foe, including Vicente Zambada, son of Chapo’s right-hand man Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, who was detained by Mexican authorities in 2009 while walking into a Mexico City hotel for a meeting with two Drug Enforcement Administration agents. Zambada was extradited to Chicago, where his entire defense rests on an argument that he was working as an informant for the United States during the period covered in the indictment against him.

“I know that in order to get anything done in Mexico, I’m not going to be able to deal with altar boys,” the American agent said.

“I think the U.S.-Mexico relationship has been set back 10 years.”Still, a deal with Chapo strains credulity, even for those who know Mexico well. He has often been called the drug world’s equivalent of Osama bin Laden. To the chagrin of Mexico’s ruling class, he was listed by Forbes as one of the richest billionaires in the world, chief of a multinational trafficking organization known as the Sinaloa Cartel that he built after his previous escape from prison in 2001. Mexican authorities said Sinaloa was responsible for the majority of drugs flowing across the country’s border with the United States. The Chicago Crime Commission called Chapo “public enemy number one,” a designation that had previously been given to Al Capone. And when the cocaine business began to boom in Europe and Asia, Chapo’s business boomed with it.

Sinaloa became the McDonald’s of the drug trade. Customers could find its products—cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines—everywhere. Operations ran so smoothly that after Chapo’s arrest in February 2014, many experts predicted that they’d continue to hum along without him. However, hopes ran high in the United States and Mexico that Chapo’s arrest would herald a new era of trust between the two governments. The arrest was seen as a sign that Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto was serious about ending a long history of government corruption, and that Washington, after some skepticism, could trust him.

Chapo’s latest spectacular escape seems to have put an end to any such illusions. “I think the relationship has been set back 10 years,” the American agent observed. He said he had received calls from colleagues across the United States who seemed disgusted with Mexican officials. “If we can’t trust them to keep Chapo in jail,” he wondered, “then how can we trust them on anything?”

This post appears courtesy of ProPublica .

July 19, 2015

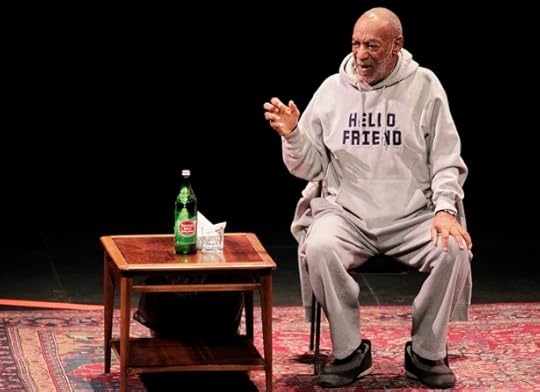

The Ugly Words of Bill Cosby

Thirty-six women have accused Bill Cosby, once one of America’s most beloved actors and comedians, of sexual misbehavior. The 77-year-old star, who has not been charged with a crime, has publicly denied these accusations. But a new legal document now reveals that the pattern of behavior described by many of the accusers—that Cosby drugged them before initiating sexual contact—were acknowledged by the comedian himself.

On Saturday, The New York Times published excerpts from a deposition Cosby gave in 2005, in a civil lawsuit brought by one of his accusers, Andrea Constand. (The two settled out of court in 2006.) The information obtained in the deposition isn’t new. But the transcript is nonetheless remarkable for the presence of Cosby’s words—and their stark ugliness.

In an excerpt presented by the Times, Andrea Costand’s attorney asks Cosby how he could be so certain that the alleged sexual encounter was consensual. His response: “I walk her out. She does not look angry. She does not say to me, don’t ever do that again. ”

Later in the deposition, Cosby cooly describes how he broke off a physical relationship with Beth Ferrier, another woman who accused him of drugging and molesting her:

Q. How did it end with her?

A. Stopped calling for rendezvous.

Q. You stopped?

A. Yes.

Q. Why?

A. Just moving on.

Q. What does that mean?

A. Don’t want to see her anymore.

In a comedy album released in 1978, Cosby stated his opposition to marijuana and cocaine, describing the latter as an illegal drug where “you could not be sure what you are getting.” Yet such uncertainty didn’t prevent him from obtaining powerful depressants for use in his sexual conquests—though Cosby was careful to avoid taking the drugs himself.

“What was happening at that time was that that was—Quaaludes happen to be the drug that kids, young people were using to party with and there were times when I wanted to have them just in case.”

During his decades in the public eye, Cosby assumed a role as a fierce critic of contemporary African-American morality. In a biting stand-up routine from the 1980s, Eddie Murphy hilariously recounted receiving a phone call from Cosby complaining about his frequent on-stage profanity. Years later, in his famous “Pound Cake” speech delivered on the 50th anniversary of Brown vs. the Board of Education, he decried black use of “backward” clothing and the prevalence of urban slang:

We’ve got to take the neighborhood back. We’ve got to go in there. Just forget telling your child to go to the Peace Corps. It’s right around the corner. It’s standing on the corner. It can’t speak English. It doesn’t want to speak English. I can’t even talk the way these people talk. “Why you ain’t where you is go, ra,” I don’t know who these people are. And I blamed the kid until I heard the mother talk. Then I heard the father talk. This is all in the house. You used to talk a certain way on the corner and you got into the house and switched to English. Everybody knows it’s important to speak English except these knuckleheads. You can’t land a plane with “why you ain’t …” You can’t be a doctor with that kind of crap coming out of your mouth. There is no Bible that has that kind of language.

Cosby is hardly the first celebrity whose private misbehavior contrasts with a pristine public image, and he won’t be the last. But the contrast between his moralizing rhetoric and private misdeeds is particularly stark.

Last fall, when the sexual assault allegations against Cosby resurfaced, Ta-Nehisi Coates revisited his earlier essay published in The Atlantic about the comedian:

In that essay, there is a brief and limp mention of the accusations against Cosby. Despite my opinions on Cosby suffusing the piece, there was no opinion offered on the rape accusations. This is not because I did not have an opinion. I felt at the time that I was taking on Cosby's moralizing and wanted to stand on those things that I could definitively prove. Lacking physical evidence, adjudicating rape accusations is a murky business for journalists. But believing Bill Cosby does not require you to take one person's word over another—it requires you take one person's word over 15 others.

Now that more of Cosby’s actual words are in the public record, their sheer ugliness make them the opposite of exculpatory.

Eyes Wide Shut

“I’m in somebody else’s house. How did I get here?” says an elderly man, with deepening fear. He’s blind and deaf, scooting himself across a dusty floor on his knuckles, his voice growing more urgent as his thin fingers reach out to touch the walls of his own home. “Help me,” he cries. “I’ve wandered into a stranger’s house ... He’s going to beat me up!”

Related Story

Reenacting War to Make Sense of It

There are any number of scenes like this in Joshua Oppenheimer’s breathtaking new documentary The Look of Silence, in which a 44-year-old optometrist named Adi Rakun confronts the men who killed his brother in the 1965 Indonesian genocide of more than a million alleged Communists. The film is laden with similar moments: symbolic and resonant, but rooted in a grim reality. The man crawling on the floor is Adi’s father, who suffers from dementia and is trapped in a surreal nightmare.

The film, which opened for a limited U.S. release Friday, is the companion to 2012’s Oscar-nominated The Act of Killing, which offered a harrowing look at the aging perpetrators of the U.S.-backed genocide in Indonesia. Today, many of those men are still in power. Celebrated as national heroes, they brag openly about the mass murders they committed, reenacting for Oppenheimer in detail how they strangled, tortured, and beheaded people.

The first movie attempts to understand the circumstances that created an environment for such men to be revered, how the killers truly see themselves, and whether they’re capable of repenting for their actions. Released three years later, The Look of Silence switches to the perspective of the survivors and the victims’ families. It follows Adi, whose brother, Ramli, was among those murdered by paramilitary groups two years before Adi was born. With the help of Oppenheimer, who remains a largely invisible force behind the camera, Adi finally confronts his brother’s killers face-to-face. The documentary looks at what it’s like to live surrounded by the people who murdered your family—and how dangerous it can be to seek truth and healing in a country with a legacy of lying about and defending atrocities.

Though Adi didn’t witness firsthand the choking effects of violence, he grew up in a village that did. He learned of Ramli’s death from his mother (the only person who would speak about him), and, later, from Oppenheimer’s on-camera interviews with the perpetrators. The audience, in some ways, learns and processes facts alongside him. In scenes interspersed throughout the film, Adi sits quietly in an empty room before an old TV set. In one, he’s watching an excerpt from a 1967 NBC News report, where an Indonesian man tells a receptive American journalist how beautiful his country is now that it’s been cleansed of Communists. In other scenes, Adi watches two old men reenact with glee how they’d slit people’s throats, castrate them, and drag them through the fields to be dumped into the river.

But in the film’s most gripping scenes, Adi sits with his brother’s killers in real life—often while testing their eyesight—and asks them to take responsibility for their crimes. Before knowing Adi’s identity, most eagerly profess their deeds. One admits to bringing a woman’s head into a store to frighten the Chinese owners, and others to drinking their victims’ blood because it was the only way to avoid going crazy. “Both salty and sweet, human blood,” the death-squad leader, Inong, tells Adi, unprompted, during their exchange. “Excuse me?” Adi asks, as if unsure he’d heard correctly. “Human blood is salty and sweet,” Inong repeats.

After enough of these kinds of unimaginable details—both The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence are rife with them—it’s easy as a viewer to feel numb. Not from desensitization, but from the exhaustion of being pulled apart by competing emotions: horror, disgust, and disbelief on one hand, and admiration and empathy for Adi on the other, who never once even raises his voice with his guests. His bravery—there’s no other word for it—causes his family to balk once he tells them he’s been meeting with Komando Aksi death squad leaders. “Think about your children!” his wife warns him. His mother advises him to carry a butterfly knife or a club, and to not drink anything he’s offered in case there’s poison in the cup (“Tell them you’re fasting,” she says.)

Drafthouse Films

Drafthouse Films In The Look of Silence, “blood-thirsty,” has literal meaning. “Eviscerating” and “heartrending,” too. To say that the film cuts deeply feels wrong, after hearing veteran executioners discuss how they removed the limbs of their victims. And so it’s no surprise that when the film ends, for many viewers, the only response that might feel right is to say nothing at all for a while.

But to do that is to do an injustice to the movie. Neither Adi nor Oppenheimer are passive witnesses to what they discover. While Adi’s job is to correct the vision of others, he also tries to rectify their flawed vision of themselves and their place in history. He tells the killers that their truth is mere “propaganda.” He tells his son that his teachers are lying when they say the Communists were evil and had to be crushed.

Oppenheimer’s own hand in the film is invisible but critical. Adi encouraged him to collect the stories of the killers, but Oppenheimer also paved the way for Adi to meet with them safely by ingratiating himself to leaders and paramilitary groups. After speaking with dozens of perpetrators, he came to understand their revisionism as a symptom of collective ignorance. “Because they’ve never been removed from power ... they try to take these bitter, rotten memories and sugarcoat them in the sweet language of a victor’s history,” Oppenheimer told me. If The Act of Killing strips away the facade to reveal the killers’ hypocrisy, The Look of Silence looks at the lies both the perpetrators and victims have told themselves for decades in order to survive.

Even for a film that chooses to convey horror in close-up, The Look of Silence’s message finds broad relevance across geopolitical lines. The film doesn’t shy away from the U.S.’s role in the genocide: In one scene, a murderer says he should be rewarded with a trip to the U.S. for his work; in another, a perpetrator says, “We did this because America taught us to hate Communists.” The Indonesian genocide, Oppenheiemer said, is as much America’s history as the mass killing of Native Americans. He thinks the film should also prompt viewers to think of America’s involvement in other wrongdoings, past and present, that allow its citizens to lead comfortable lives with cheap electronics, clothes, and oil.

And yet. “It’s very moving to me that the film is coming out in the United States this summer, after a particularly traumatic year in which we’ve been reminded again and again ... in unmistakable ways, of the open wound of race right here,” Oppenheimer said. The last thing he wants is for people to see The Look of Silence as “as a window into a far-off place about which we know little and care less.” The spirit of Indonesia’s anti-Communist killings, which lasted from 1965-1966, isn’t so foreign: Oppenheimer describes America’s history of racism in more global terms. White supremacists and the Klan were effectively “neo-Nazi paramilitary mobs” who carried out “state-sanctioned terrorism ” through lynchings and other acts of violence against blacks. He recalls his own childhood, going to high school in suburban Maryland, where his mostly white magnet school within a majority-minority school was effectively legal “apartheid.”

Drafthouse Films

Drafthouse Films An American listening to Oppenheimer might feel defensive, or ashamed. But The Look of Silence is about how this impulse to turn away from blunt truths—about one’s country and history—harms progress and reconciliation. In Adi’s case, people would chastise him for bringing up “politics” or for “opening a wound” every time he talked about his brother, whose name had become verboten in his village as shorthand for the entire genocide. Before change can unfold at the top, transformation needs to happen at the bottom. “You can’t have democracy without community, and you can’t have community if everyone’s afraid of each other,” Oppenheimer said.

And change is happening. After The Act of Killing was nominated for an Academy Award, the Indonesian government finally acknowledged the genocide, saying that the country would deal with it in its own time. The Look of Silence has been screened over 3,500 times to more than 300,000 people in Indonesia, Oppenheimer said. Many of those people will be relatives of the killers, but the film offers a hopeful blueprint for how generations living in the shadow of past crimes can come together, and move forward.

All these lessons take time to materialize fully. The Look of Silence is an inherently political film, but not one that ends with a lengthy text crawl imploring the audience to do their part and change the world. Like its predecessor, it’s a devastatingly beautiful film about the power of cinema, and its ability to testify to some aspect of human nature with a veracity and elegance that escapes other mediums. Every scene weighs on the audience. But Oppenheimer and Adi manage to locate a lightness as well that lessens the burden.

July 18, 2015

A New Beginning for Greece?

In just a few weeks, Greece’s prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, went from being a staunchly anti-austerity, defiant would-be euro zone jilter to a bailout-embracing, leftist-purging premier. And, on Saturday, after he formally replaced some disloyal members of his Syriza own party in the Greek cabinet, Tsipras ordered the country’s banks to open for business on Monday.

“The move had been widely expected after the European Central Bank agreed to re-open the emergency credit lines which the tottering Greek banking sector needs to survive,” Reuters noted. While limits remain—foreign transfers are still banned and Greeks can still only withdraw €420 per week—the development shows Greece is starting the process of getting back to business with new bailout talks beginning this week.

More surprisingly, the Greek government also pledged to raise €50 billion in a privatization push. To achieve this mark (or at least attempt to), the AP reported, the government will “sell government assets and allow for private development of state-owned property.” Given where Tsipras started in January, this change of tune is something akin to Dylan not only going electric, but also endorsing the Vietnam War, all while under duress.

Among those saying that the reforms will never work are Tsipras’s erstwhile allies. On Saturday, former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis told the BBC that the European demands on Greece will “go down in history as the greatest disaster of macroeconomic management ever.”

For now though, the re-opening of the banks carry a symbolic weight, even if the act only makes a small difference. “This will improve the image of the economy for Greeks inside the country,” one University of Athens professor told Bloomberg. “It’s just the beginning and a more ambitious option wasn’t possible.”

Clueless and Capitalism: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

As If: A Journey Through the Los Angeles of Clueless

Molly Lambert | Grantland

“Clueless formed the way I saw my city and myself, even as I grew not into a Cher, but a total and utter Tai. Its messages feel fresh, because they remain urgent — the paramount importance of female friendships, of not being defensive about your own ignorance, of trying to see the world optimistically.”

How ‘Privilege’ Became a Provocation

Parul Sehgal | The New York Times Magazine

“Most of us already occupy some kind of visible social identity, but for those who have imagined themselves to be free agents, the notion of possessing privilege calls them back to their bodies in a way that feels new and unpleasant.”

Stream of the Crop

Emily Yoshida | The Verge

“When my iPhone reset I would have access to Apple’s long-awaited streaming-music service, and I was standing on a cliff, arms outstretched, waiting for my corporate overlords to beam me up into their mothership and carry me off to a land of unlimited music and radio curated by people with better taste than me.”

Runaways and Creeps: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Lady Gaga Goes to the Middle

Lindsay Zoladz | Vulture

“Perhaps a little selfishly, I’m worried about what might happen if Gaga goes fully normal. After all, we’re talking about the woman who, bless her heart, rescued us all from normal in the first place.”

Ta-Nehisi Coates and a Generation Waking Up

Brit Bennett | The New Yorker

“Structurally, Between the World and Me is a conversation between black men, and this conversation is vital, but the strength of the Black Lives Matter movement is that it calls us to participate in and create new conversations.”

The Pixar Theory of Labor

James Douglas | The Awl

“Is there any other production house operating today that is more obsessed with narratives of the workplace and employment? The basic Pixar story is that of an individual seeking to establish, refine, or preserve their function as an instrument within a system of labor.”

The Pink Ghetto of Social Media

Alana Hope Levinson | Matter

“Unlike the job of editor, which also goes uncredited, these positions don’t have a high level of prestige. No one brags over martinis that they wrote the Facebook prompt for a Gay Talese piece.”

Taylor Swift Is Definitely in Her Zone

Jia Tolentino | Jezebel

“Swift is not only at the height of her powers, she’s outshining everyone else—militantly and pointedly so, while maintaining a truly impressive set of impenetrable defenses, which range from deliberate (the Slumber Party Supermodel Just-Like-You Posse) to earnest (the avowed feminism, the open letter) to innate (the fact that she’s white, blonde, bone-thin, and beautiful).”

Ai Weiwei Reconsiders Himself

Rebecca Liao | Los Angeles Review of Books

“Why does this man shape so much of what the West thinks about China? Because he gives us what we want: digestible, consistent platitudes about the lack of freedom in authoritarian regimes. ”

At Comic-Con, Bring Out Your Fantasy and Fuel the Culture

A.O. Scott | The New York Times

“For a long weekend in July, this city a few hours down the freeway from Hollywood and Disneyland becomes a pilgrimage site for something like 130,000 worshipers. It’s both ordeal and ecstasy, and the secular observer is in no real position to judge.”

A Right-Size Dream

Sheila Heti | The Paris Review

“A line drawn with love can make us as vulnerable as what the line depicts. Whatever cynicism I had about how commerce creates familiarity creates conditioned responses creates “love,” it crumbled in that instant. An artist’s love for what they create is what creates love.”

An Attack on a U.S. Military Recruitment Facility

Updated 7/18/15

A gunman opened fire at two military recruiting stations in Chattanooga, Tennessee, on Thursday morning, killing four U.S. Marines before dying in the attack. Three others, including one police officer, were wounded. On Saturday, one of the wounded, a sailor, died of his injuries.

According to Ed Reinhold, the FBI Special Agent in Charge, the Marines were killed at a recruitment center where the Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marines all share offices. President Obama described the attack as a “heartbreaking circumstance” while cautioning that “we don’t know all the details.” According to CBS News, U.S. Attorney Bill Killian said officials were treating Thursday’s attack as an “act of domestic terrorism.”

The gunman was identified as Muhammad Youssef Abdulazeez, 24, a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Kuwait. Abdulazeez had attended high school and college in Chattanooga, where he graduated from the local University of Tennessee campus in 2012 with a degree in electrical engineering. Described as “quiet and friendly” and with an interest in wrestling and mixed martial arts, Abulazeez had, in recent months, turned more toward Islam, growing a beard and attending weekly religious services. In two blog posts published on July 13, Abdulazeez commented on passages from the Koran—in one post, he writes that life is “bitter and short.” Dr. Azhar S. Sheikh, a founding board member at the Islamic center where Abulazeez worshipped, said that the young man nevertheless showed no signs of extremism.

The FBI, who is investigating Thursday’s shooting as an act of “domestic terrorism,” has not identified a motive for Abdulazeez’ act, and has commenced an investigation of his computer and phone records and bank accounts. A U.S. official told the Washington Post that in 2014, Abdulazeez traveled to Jordan, his ancestral home, and spent several months abroad—but it is unknown whether he made any contact with Islamic extremists during his stay.

Aside from a recent charge for driving under the influence, Abdulaezeez had no police record. According to law enforcement officials, his father was investigated by the FBI for donating money to a group with extremist ties, and was placed on a terrorism watch list before later being removed. However, officials cautioned, this past investigation of the father provided no information about Abdulazeez himself.

The violence in Tennessee represents the first attack on a U.S. military recruitment center since 2009, when Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad, a 23-year-old man unhappy about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, opened fire on two men standing near a recruitment center in Little Rock, Arkansas, killing one. Recruitment centers, by their nature, are open to the public, and Chattanooga’s Armed Forces Career Center had no additional security at the time of the attack.

On Friday, the family members and friends of the four victims began to publicly identify their loved ones. The Facebook page of India Battery, 3rd Battalionhttp://abcnews.go.com/US/wireStory/latest-sailor-dies-wounded-shooting-32535473 12th Marines revealed that Sgt. Thomas Sullivan, a member, had died in Chattanooga. The 40-year-old Sullivan, a native of Springfield, MA, served two tours in Iraq. Also among the dead was Squire “Skip” Wells, a 21-year-old from Marietta, GA, who had just joined the Marines last year. The New York Times has identified David Wyatt of Burke, NC and Carson Holmquist of Polk, Wisc as the third and fourth to lose their lives. The sailor was died of his wounds on Saturday was identified by family members as Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Randall Smith.

In a statement released after the attack, Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam said that “lives have been lost from some faithful people who have been serving our country, and I think I join all Tennesseans in being both sickened and saddened by this.”

This story will be updated as new developments unfold.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower