Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 385

July 23, 2015

The U.S. Governor Who Forgot How to Veto a Bill

“I’m finally learning how to play the game of a politician,” Maine Governor Paul LePage told reporters in late May, moments after he declared, in a fit of pique over a stalled proposal to cut income taxes, that he would veto every single bill written by a Democrat that passed the state legislature.

LePage may have learned the art of politics in the four-and-a-half years since Maine voters first elected him to the governorship, but it seems he hasn’t yet mastered state law. In a turn of events as incomprehensible as it sounds, the combative conservative apparently muffed the vetoes of 65 bills at the end of the annual legislative session. He is now asking the state’s highest court to rule on whether he successfully rejected the measures, or whether they have in fact become law—as the House and Senate contend—because LePage missed the 10-day window he had to veto them.

It’s the latest and most befuddling twist in the soap opera of a governor who has brought Tea Party bombast to a state long known for producing centrists and diplomats. In 2010 and 2014, LePage twice took advantage of a split opposition to win three-way elections. Since then, he’s been alternately described as the nation’s “craziest governor,” its “most outlandish,” or in the words of Justin Alfond, the Democratic leader in the state senate, simply “the king of chaos.”

But despite LePage’s victory last November, the last few months have marked something of an unraveling for the famously filter-free conservative—even before the veto mess. A bipartisan legislative committee is investigating whether he forced a charter school not to hire the Democratic speaker of the house, liberals are calling for LePage’s impeachment, and his standing within his own party has deteriorated to the point where the legislature overrode his veto of the state budget with help from the Republican senate president (averting a government shutdown). In retaliation, a LePage-aligned political organization run by his daughter began recording robocalls in Republican districts, accusing legislators of siding with Democrats. In recent days, a veteran GOP operative has launched a group for Republicans who oppose LePage’s approach.

What’s clear, then, is that outside of a few loyal allies in the House, LePage’s relationship with the legislature has reached a new low. And yet: How do you screw up a veto?

It’s not as if this was the first time the governor was breaking the pen out of its box. In fact, LePage has issued more vetoes than any governor in the 195-year history of Maine, and the legislature has, in turn, overridden a record number of those vetoes. For most of June, the governor had been carrying out his threat to reject any bill sponsored by a Democrat (and that expanded to some Republicans as well), so as the legislature’s session drew to a close, lawmakers had grown accustomed to accepting the hand delivery of veto messages by the bucketload from a member of the governor’s staff, often near the end of the 10-day window he has to issue them.

So when, earlier this month, the deadline passed for LePage to veto the first batch of 71 bills that the legislature had approved in the final days of the session ending June 30, lawmakers were confused. “We thought, ‘Wow, what a crazy mistake,’” Jeff McCabe, the Democratic House majority leader, told me in an interview. LePage had spent the July 4th weekend campaigning with Chris Christie, so Democrats thought he might simply have lost track of time. But then the veto deadline passed for the rest of the bills, and it became clear, McCabe said, that LePage “was really doubling down and he was pretending that his interpretation of the [state] constitution was way different than our interpretation.”

“For the governor to not understand the rules defies all logic, defies all of his actions, and defies the decisive leader that he says he is for our state.”The rules for issuing a veto are not, it turns out, quite as simple as the famous Schoolhouse Rock video makes it seem—at least in Maine. The state constitution gives the governor longer than 10 days to veto bills when the legislature’s adjournment prevents a bill’s return. After initially giving a different explanation, LePage’s office has argued that because the legislature left without setting a firm date to reconvene, the governor could exercise a provision in the constitution allowing him to return vetoed bills when the legislature next meets for three-consecutive days. So on July 16, he delivered veto letters for 65 of the 71 bills. But both Democratic and Republican leaders refused to accept them, saying that both chambers had clearly set a return date for the express purpose of voting to override or sustain the governor’s vetoes. LePage had missed the deadline, they said, and the bills had become law. “We made it very clear,” McCabe said, noting that even Republicans had mentioned the mid-July session before they left in June. (The Bangor Daily News has an even more detailed explanation of the dispute here.)

While Democrats like McCabe believe LePage was trying to cover up a simple mistake, others aren’t so sure. “For the governor to not understand the rules defies all logic, defies all of his actions, and defies the decisive leader that he says he is for our state,” Alfond, the Democratic senate leader, told me. “There are all kinds of theories for why this has happened,” he said. “It’s been one story after another. It’s just hard to figure out whether they intended to do this, whether this was some sort of mix-up on their part, whether they were looking for confrontation.”

With the legislature refusing to acknowledge his vetoes, LePage is now turning to the courts to find out, quite literally, whether the bills have become laws that his administration is constitutionally obligated to enforce. Few of the measures are considered highly controversial, and many would have become law by veto overrides anyway, but political observers believe the legislature was likely to sustain LePage’s rejection of a measure granting state-welfare benefits to immigrant asylum seekers.

“I have a constitutional duty, as Governor, to ‘take care that the laws be faithfully executed,’” LePage wrote in his letter to the justices of Maine’s Supreme Judicial Court. “Accordingly, I must know whether the 65 bills I was prevented by the Legislature’s adjournment from returning to their houses of origin by July 11 have become law.” The court has set a date at the end of the month to consider the question, and with the exception of one Republican leader in the Democratic-controlled House, the bipartisan-legislative leadership is united against him. “The only voice that seems to believe that he has the ability to do this is his administration and people who are on his paid staff,” Alfond said.

LePage’s office has insisted that no, the governor is not dumb. “Despite the repeated claims by Democrats and their faithful stenographers in the Maine media, the governor did not ‘botch’ the vetoes,” LePage spokesman Peter Steele wrote in an email.

The governor’s letter to the Law Court spells out his position quite clearly. Democrats and their hand-picked attorney general are content to do business as usual, but the governor prefers to follow the process specified in the Constitution. It’s now up to the Law Court to decide whether the Legislature’s action—or inaction—triggered that process.

While there appears to be a general consensus that LePage is likely to lose in court, opinions are mixed as to whether he missed the deadline by accident or not. “My strong sense is that this is intentional, not a mistake,” said Mark Brewer, a professor of political science at the University of Maine. Brewer said that as LePage has been stymied by the legislature over the last several months, he’s been “pushing the boundaries on the prerogatives and powers of the executive”—not unlike President Obama, who is mired in a court battle with Republicans over his executive actions on immigration. “He’s picking a fight to prove a point,” Brewer said.

Alfond doesn’t dismiss that possibility. “He is the king of chaos, the king of unpredictability, and someone who thrives when there’s conflict and when there’s unease,” he said of LePage. (As with many lawmakers, the governor and Alfond have a history: LePage, 66, routinely compares the much-younger Democratic leaders in the legislature to children, and in May he said Alfond should “be put in a playpen.”)

Yet LePage is playing around with real laws. By waiting on vetoes that might have been sustained by the legislature, such as the immigrant-benefits measure, he’s risking allowing a law that he opposes, and might have been able to stop, going on the books. And unlike Obama’s legal fights with Republicans over immigration and healthcare, LePage’s tactics have cost him significant support within his own party. Alfond, a 40-year-old real-estate developer who represents much of Portland, said the silver lining of the confrontation is that it has pushed Republican and Democratic lawmakers to work together much more collaboratively against the governor, as evidenced by the many laws they passed this year by overriding LePage’s vetoes.

“He’s been in politics now for quite a while now, and he’s pretty good at it. There’s a method behind what he’s doing, let’s put it that way.”With the governor and the legislature at loggerheads, both ideologically and institutionally, both parties are already looking ahead to an election that’s more than a year away. Right now, each party controls one chamber. Republicans allied with the governor have already announced plans to turn LePage’s proposal to cut income taxes into a ballot initiative, while Democrats will try to force GOP lawmakers to choose between breaking from LePage or risking electoral defeat. “The reality is that House and Senate Republicans need to decide whether or not they’re going to side with the governor’s antics and his increasingly, obviously unstable temper,” McCabe said. “The electorate’s not going to put up with that, and I think the midterm elections will decide what his last two years look like.”

Brewer, however, warned that LePage should not be underestimated. After all, this is a governor who scored several victories in his first term and won a reelection many thought he would lose, with a significantly higher percentage of the vote than in his first win—all in spite of his reputation as a partisan, and occasionally offensive, bomb-thrower. As the former businessman himself admitted, he’s learned the political game. “He’s been in politics now for quite a while now, and he’s pretty good at it,” Brewer said. “There’s a method behind what he’s doing, let’s put it that way.”

July 22, 2015

E.L. Doctorow’s Masterful Manipulation of History

In the first chapter of his classic novel Ragtime, E.L. Doctorow memorably describes an afternoon shared by Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud in early 1900s New York:

Their ultimate destination was Coney Island, a long way out of the city. They arrived in the late afternoon and immediately embarked on a tour of the three great amusement parks, beginning with Steeplechase and going on to Dreamland and finally late at night to the towers and domes, outlined in electric bulbs, of Luna Park. The dignified visitors rode the shoot-the-chutes and Freud and Jung took a boat together through the Tunnel of Love. The day came to a close only when Freud tired and had one of the fainting fits that had lately plagued him when in Jung’s presence.

The defining image of this passage—the two psychoanalysts sailing through a Tunnel of Love—is so delicious that it seems too good to be true. That’s because it is. Doctorow’s description of the expedition, by his own admission, sprung not from historical fact but rather from his imagination.

To his critics, who include John Updike, Doctorow’s fabrication in his “historical” novels made him something of a fraud. “[The inventions] smacked of playing with helpless dead puppets,” Updike wrote in the New Yorker. But to Doctorow, who died Tuesday at the age of 83, these inventions formed the essence of his craft. In a 2006 essay published in the Atlantic, he wrote:

Of course the writer has a responsibility, whether as solemn interpreter or satirist, to make a composition that serves a revealed truth. But we demand that of all creative artists, of whatever medium. Besides which a reader of fiction who finds, in a novel, a familiar public figure saying and doing things not reported elsewhere knows he is reading fiction. He knows the novelist hopes to lie his way to a greater truth than is possible with factual reportage. The novel is an aesthetic rendering that would portray a public figure interpretively no less than the portrait on an easel. The novel is not read as a newspaper is read; it is read as it is written, in the spirit of freedom.

There’s no greater sin in journalism—known colloquially as the “first draft of history”—than fabrication, as writers like Stephen Glass discovered. But in retrospect, the fudging of names and events can occasionally be forgiven if it serves a larger purpose. The longtime New Yorker writer Joseph Mitchell became renowned for his intimate descriptions of New York City’s dispossessed. Only later did he admit that some of his characters didn’t actually exist. Today, Mitchell’s fabrications would be a career-killing offense, his name as sullied as Glass or Jayson Blair or Jonah Lehrer. But today, his work, inaccuracies and all, is regarded as a valuable examination into a bygone era.

Doctorow never claimed to be a journalist, exempting him from the standards attached to the craft. But far from apologizing for his inaccuracies, he defended them as being essential to his work. In a 1986 interview with George Plimpton at New York’s 92nd St. YMCA, republished in The Paris Review, Doctorow said:

History is a battlefield. It’s constantly being fought over because the past controls the present. History is the present. That’s why every generation writes it anew. But what most people think of as history is its end product, myth. So to be irreverent to myth, to play with it, let in some light and air, to try to combust it back into history, is to risk being seen as someone who distorts truth. I meant it when I said everything in Ragtime is true. It is as true as I could make it. I think my vision of J. P. Morgan, for instance, is more accurate to the soul of that man than his authorized biography ... Actually, if you want a confession, Morgan never existed. Morgan, Emma Goldman, Henry Ford, Evelyn Nesbit: all of them are made up.

Nevertheless, many of Doctorow’s signature novels were set well within his lifetime. Billy Bathgate, a novel depicting a boy’s relationship with an organized criminal, took place in 1930s New York. So too did World’s Fair, the closest thing that comes to a Doctorow autobiography. The more recent Homer & Langley, published in 2009, profiled two brothers whose inability to throw anything away led to their demise in 1947—an event that dominated newspaper headlines in New York during Doctorow’s teenage years.

But rather than observe the old dictum that writers should write about what they know, Doctorow thrived by doing the opposite.

“We’re supposed to be able to get into other skins,” he told Plimpton. “We’re supposed to be able to render experiences not our own and warrant times and places we haven’t seen. That’s one justification for art, isn’t it: to distribute the suffering?”

Ai Weiwei’s 600 Days of Flowers

On Wednesday morning, as he has every day for the past year and a half, Ai Weiwei placed a bouquet of flowers in the basket of a bicycle that stands outside his studio in Beijing. The selection included carnations and baby’s breath. The day before, he’d picked sunflowers. He started the week with lilies.

For more than a year and a half, China’s infamous dissident artist has arranged his blooms in a daily demonstration against the confiscation of his passport. Titled With Flowers, the work is part-protest, part-performance art. But no longer: After four years, the artist announced via Instagram on Wednesday that the Chinese government had returned his passport. Since 2011, after Ai was arrested on charges of tax evasion, jailed for 81 days, and then released, the government had kept it confiscated, and refused him any other travel papers.

A photo posted by Ai Weiwei (@aiww) on Jul 21, 2015 at 11:51pm PDT

With Flowers endured for about 600 days. Ai started the performance on November 13, 2013, more than two years into his confinement. The demonstration serves as an extraordinary record of his confinement: He placed the flowers outside the aquamarine door at 258 Caochangdi, home to his art studio as well as his design and architecture firm, FAKE Design. They were mighty arrangements, rarely modest, all formally documented on Flickr. Ai is both active and savvy on social media (which is part of what prompted his trouble with the authorities), and his flowers traveled far beyond the plastic basket on his black Giant bike via posts on Flickr, Instagram, and Twitter.

The exercise is typical of the work that’s made Ai a beloved figure at home and abroad. With Flowers is an endurance piece that results in delight, not exhaustion. It’s repetitious yet deceptive, a bit like the artist’s Sunflower Seeds, a 2010 installation at London’s Tate Modern featuring millions of ceramic seeds that were each individually handcrafted by workshops in Jingdezhen.

Related Story

Ai Weiwei, China's Useful Dissident

It’s also related to the work that put him in the sights of Chinese authorities. Following the devastating earthquake in Sichuan in 2008, Ai set out to name (with the help of civilian investigators) the more than 5,000 children who were killed when their schools collapsed. While the government formally suppressed the information, Ai listed the children’s names on social media and in exhibitions, also referring to the disaster in other works. Straight, a sculpture that appeared at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in 2012, is made of 38 tons of rebar. Ai recovered the mangled steel from the Sichuan quake, then worked with craftsmen to straighten out each piece.

Ai’s work is known for its playfulness and irreverence, but it’s his ability to make profound statements gracefully that underscores his global impact. Placing flowers is an elegant gesture, but also a mournful one. Mixed sentiments like these abound in Ai’s work, as well as in With Flowers.

On September 27, 2014, the day that his monumental installation @Large opened at the former Alcatraz prison, Ai celebrated with roses and daisies. There were other milestones preceding With Flowers that Ai missed out on because of his inability to travel: a Sundance Film Festival award for Never Sorry, the documentary about his life and work, or the opening of his first major U.S. survey at the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C.

What’s so bracing about With Flowers is that Ai might never have left the country again, but he intended to endure his punishment every morning with a statement—a declaration of persistence. It’s unclear whether China’s decision means that Ai can travel back and forth safely, but he told The Guardian that he intends to visit his son in Germany. May he be greeted with flowers when he gets there.

Jason Rezaian's Year of Imprisonment in Iran

Wednesday marked the one-year anniversary of the detention of Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post reporter who is being held in one of Iran’s most notorious prisons on vaguely defined charges.

Rezaian and his wife, Yeganeh, were scooped up by Iranian security services in a midnight raid last July. Rezaian is accusing of committing “espionage for the hostile government of the United States” and for spreading anti-Iranian propaganda. In a statement on Wednesday, Rezaian’s brother Ali detailed his brother’s ordeal:

Since that night, Jason has been held in Evin prison in Tehran. During this time he has been subjected to months of interrogation, isolation, and threats. He has been deprived of basic medical treatment exacerbating minor medical issues and risking permanent physical harm. Fortunately, Yeganeh was released on bail after 72 days, but is prohibited leaving the country or returning to work as a journalist. For five months after her release she was prohibited from speaking with an attorney.

“Though Iranian law limits such treatment to 20 consecutive days, Mr. Rezaian was held in solitary for 90 days or more,” The Washington Post editorial board added. “Also illegal was the failure to bring formal charges against Mr. Rezaian for more than five months and the severe restriction of his legal representation. Iranian law says no person may be detained for more than a year, unless charged with murder; yet Mr. Rezaian remains imprisoned.”

There was hope that the negotiations over a nuclear agreement with Iran that culminated with the signing of a deal in Geneva last week might yield progress for Rezaian and other Americans still locked up in the Islamic Republic. Instead, with the nuclear deal seemingly imminent last Monday, Iran held the third closed-door court session of Rezaian’s trial, which is being presided over by a judge on a European Union blacklist for human-rights abuses.

In recent days, both President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry have promised that they would seek to secure the release of the four Americans imprisoned in Iran. According to The Washington Post’s executive editor Marty Baron, Rezaian’s lawyer believes the next hearing will be last in the trial, which is a good sign.

Meanwhile, Rezaian has now been held in prison longer than any Western journalist in Iran. Those curious about his anti-Iran bona fides should see his 2012 interview in The Atlantic. In it, Robert Wright asked Rezaian about a proposal to publicly release the outline of a nuclear deal with Iran, combat suspicion of America among Iranians, and show that the U.S. was approaching Iran respectfully and in good faith.

Rezaian called the proposal “a big advance,” but batted away the suggestion, not because of Iranian stubbornness, but because of likely American opposition. “We have too many, for lack of a better word, meatheads in Congress to let that happen,” he said, adding that the climate of “anti-Iranianism” would prevent such pragmatic thinking.

A Quiet Triumph for Gay Workers

Gay Americans can now get married in the morning and then, in the afternoon, just for being gay, their employers can fire them. Is doing so legal? Up until last week, the answer was yes for Americans living in the 28 states without explicit bans on workplace sexual-orientation discrimination. But an important ruling from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) means that courts in those states are now more likely to say that such discrimination is illegal, and that gay Americans are already protected from such discrimination under existing law.

Of course, this is all a bit iffy. The EEOC’s rulings dictate the rights of most federal workers, but are non-binding in the private sector, where they’re interpreted as recommendations. Still, courts and human-resources professionals look to the agency for guidance on matters of employment discrimination. "When the EEOC says something, that really matters,” says Sam Bagenstos, a professor at the University of Michigan’s law school.

Even so, advocates would like to lock down the illegality of sexual-orientation discrimination, and there are two parallel, non-competing paths for them to pursue: litigation and legislation. The first would rely on lawsuits to wend their way through the courts, with the hope that a legal consensus would slowly coalesce. This is where Baldwin v. Foxx, the unexpectedly timed EEOC ruling last week, comes in. It gives courts a trustworthy guideline to look to, and is thus a formal step toward establishing comprehensive nationwide protections for LGBT workers, as opposed to leaving their fates up to a state-by-state legal patchwork.

Essentially, the ruling in Baldwin v. Foxx said that it was illegal for a federal air traffic controller to be passed over for a permanent job because of his sexual orientation. The legal explanation was that discrimination based on sexual orientation is no different from discrimination based on sex—and workplace discrimination based on sex is banned by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The reasoning, in short, is that if a man marries a man and gets fired as a result, the outcome would’ve been different than if he were a woman (who likely wouldn’t have been fired for marrying a man). “It's based on a kind of stereotype about the kinds of romantic partners or long-term partners people ought to have based on their sex,” says Bagenstos.

In the past decade, some lawyers have already been using the same legal logic as the one in Baldwin v. Foxx to argue that sexual-orientation discrimination is illegal, but this ruling might strengthen that argument in judges’ eyes and will probably encourage more lawyers to make the same case. As this process accelerates, one of two things will happen. Either certain lower courts will disagree with the EEOC’s ruling, in which case a series of appeals could eventually bump the case up to the Supreme Court, which would have the opportunity to cement or reject anti-discrimination rules. Or, most of the lower courts will agree with each other and the EEOC, making it less likely the Supreme Court would review their consensus.

Bagenstos considers the ruling “a big deal,” but isn’t shocked that it hasn’t been on the front page of every newspaper. “I guess it's not that much of a surprise that a somewhat obscure decision by an independent agency in the middle of the summer doesn't get a lot of press,” he says. Suzanne Goldberg, a professor at Columbia Law School, observes, “There is often not a lot of publicity for agency determinations even when those determinations are profoundly important.”

It’s important, yes, but many advocates are aware that the litigation approach can unfold slowly. Some are also afraid of what the Supreme Court might decide, if a case were to get there. Which leads to path number two: a federal civil-rights law that bans workplace discrimination in every state. Bills with this intention have been submitted to Congress practically every year since 1973, and none have passed. Recently, some advocates have set their sights on more expansive legislation, which would encompass discrimination in other realms (such as being denied a mortgage or getting evicted) and against other groups (such as transgender people).

If this issue has at least been on Congress’s radar since the 1970s, why is it that the EEOC only just now extended the applicability of a 51-year-old law to discrimination based on sexual orientation? One reason is that precedents set in the ‘70s and ‘80s indicated that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 didn’t go that far in its protections. A number of things have changed since then. “Nondiscrimination based on sexual orientation has become such a widely accepted principle, particularly in the workplace, and I think that has opened courts and judges up to hearing arguments that are rooted in legal logic,” says Bagenstos. Also, the act’s applicability was elucidated by an unlikely LGBT ally: Antonin Scalia. In 1998, Scalia wrote on behalf of a unanimous Court that the act covered same-sex sexual harassment, even if the law didn’t explicitly say so. “Statutory prohibitions often go beyond the principal evil to cover reasonably comparable evils,” he wrote.

The EEOC’s ruling last week may seem to be riding the momentum of last month’s same-sex-marriage ruling (which Scalia dissented from) but it had come to be expected by legal experts over the course of President Obama’s term, as the EEOC started signaling that sexual-orientation discrimination qualifies as sex discrimination. Still, the ruling’s precise timing was unpredictable, and when the EEOC put out its ruling a week ago, there were no flag-waving, face-painted gay-rights advocates waiting on its steps, no photographers on hand. Instead, it was just a government agency quietly announcing its official stance on workplace discrimination in PDF form. But no lack of fanfare can diminish its importance.

How Many Sandra Blands Are Out There?

The release of a video of Sandra Bland’s arrest doesn’t explain how the 28-year-old ended up dead in a Texas jail cell, but it makes a convincing case that she never should have been jailed in the first place.

The traffic stop, in which she was pulled over for failing to use a blinker (after an officer got into the lane behind her, no less) is a good case study in everything a stop shouldn’t be. Did Trooper Brian Encinia really need to pull her over? Once he had, did he need to escalate the encounter? During the exchange, Bland is curt, but not initially combative—and in any case, failing to be polite to a police officer, while perhaps unwise, is not a crime.

The video is tough to watch in places. This is a quick cut; the full version is here.

There are some questions about apparent edits in the video, which the Texas Department of Public Safety says are technical glitches. DPS also says it will release a new, fixed version soon. But there’s plenty that’s clear from the original version.

Encinia pulls Bland over, asks her for her license and registration, asks how long she’s been in Texas, and then heads back to his car. It’s when he returns that the trouble starts.

“Okay, ma’am. You okay?” he asks. She replies, testily: “I’m waiting on you. This is your job. I’m waiting on, whatever you ...” Encinia says, “I don’t know. You seem very, very irritated.”

Bland explains that she’s upset because she felt like he was tailing her so she got over to get out of his way, and now she’s been pulled over for not signaling. Like many African Americans, she may have seen the stop as a result of “driving while black”—being racially profiled, and then pulled over on some minor pretext. (Friends have noted that she was upset about police brutality in recent months.) As a graduate of Prairie View A&M, she was also probably familiar with the history of tension between African Americans and law enforcement in the area.

Encinia, just as testily, says: “Are you done?”

“You asked me what was wrong, and I told you, so now I’m done, yeah,” Bland replies. He then asks her, politely, to put out her cigarette. She says she doesn’t want to, and she’s in her own car.

That’s where things really go deeply wrong. Encinia says, “You can step on out of the car,” and she declines. He then orders her to step out of the car. He clarifies a few moments later that this is a “lawful order,” a legal term for a demand with which she is required to comply. But why did he issue the order? She seems understandably baffled, and asks him to explain. Encinia never offers a good reason for why he’s ordering her out of the car, and it’s tough to see anything in the order except spite and anger at being questioned by a citizen acting within her rights.

Encinia threatens to tase Bland—“I will light you up!”—and drags her out of the car. He also calls for back up. He tells her he was only going to give her a warning, but now she’s going to to be arrested. She demands, as is her right, to know why she’s being arrested. He doesn’t answer immediately, though later he says she’s “not compliant.” He accuses her of resisting arrest, and she says he’s jerking her around. This is a common pattern in disputed arrests: Police charge suspects for resisting arrest in cases where advocates say the people are not resisting, or in which they are being physically moved by officers who cite the movement as evidence of resistance. The video doesn’t offer any compelling evidence that she is resisting arrest, despite her obvious anger at the officer and a growing string of obscenities. (At one point, she says, “South Carolina has y’all’s bitch asses scared.”)

Related Story

Sandra Bland and the Long History of Racism in Waller County, Texas

Later, after another officer arrives, she’s tackled to the ground and protests, “I have epilepsy!” Encinia answers: “Good.” Encinia also tells a bystander—whose clip of part of the encounter was previously released—to stop filming, though he appears to be within his rights in recording the encounter. (Bland shouts, “Thank you for recording!”)

One of the most painful moments in the video is when Bland tells Encinia, “I cannot wait until we go to court.” In hindsight, every viewer knows her day in court will never come. But it’s also possible that everything Encinia did would have passed muster in court, especially since juries, prosecutors, and judges tend to defer to police in close cases. The video does, however, make Encinia’s response to Bland seem outrageous, disproportionate, and inappropriate.

Bland’s arrest fits into the category of police overreacting to perceived challenges to their authority, even provocations as minor as an individual asking why he or she is being arrested. A prosecutor charges that Freddie Gray was given a “rough ride” in a police van as punishment for running away from police and making a scene when he was arrested (an arrest that the prosecutor further charges was unlawful). If Bland had not died—authorities called it a suicide, though they’re now also investigating it as a murder—it’s unlikely that the video would have seen the light of day. It certainly would not have received widespread-media attention.

As my colleague Rebecca Rosen notes, one of the biggest revelations in the Justice Department’s report on policing in Ferguson after Michael Brown’s death was how many egregious examples of police misconduct went essentially unremarked upon and unpunished, simply because they didn’t end with anyone dead. Yet each of those incidents did have a cost: a loss of dignity, dehumanization, a gulf between police and citizens, and often a violation of civil rights. How many cases like Sandra Bland’s are there? It shouldn’t take a tragedy for police to be called to account for abusing their authority.

Woody Allen’s Dark, Tedious Fantasies

The plot of Woody Allen’s Irrational Man, a moderately dark drama about a malcontent philosophy professor suffering from an excess of first-world problems, hinges on a conversation overheard by Abe Lucas (Joaquin Phoenix) and his student Jill Pollard (Emma Stone) from a nearby diner booth. A woman, in tears, recounts to friends how a corrupt judge has conspired with her ex-husband to grant him full custody of their child, and describes the anguish she feels as a result. Jill remarks that it sounds like it would be a good thing if the judge got cancer, but Abe, more intent on an active solution to the woman’s woes, decides it would be more practical to simply kill him.

It’s a flimsy premise upon which to base a philosophical exploration of the dark power of rationalization—Abe half-heartedly persuades himself that the murder is justifiable because the judge has no family, and is overstepping his bounds as an arbiter of justice—but it’s also distinctly uncomfortable when you consider that Allen has had his own share of parental disputes decided in a court of law. In 1993, he lost custody of his three adopted children to his former partner, Mia Farrow, and was denied visitation rights to his daughter, Dylan, who had accused him of molesting her. In February last year, a few months before Allen announced Irrational Man was going into production, the case was rehashed after Dylan Farrow published an open letter at The New York Times describing how her father had sexually assaulted her as a child. Given Allen’s rapid pace and prodigious output, it’s possible he was writing the movie during that time, and watching the film, it’s hard to separate Abe’s murderous urges from Allen’s own desires. Throughout his career, Allen’s movies have been elaborate fantasies based on his own specific predilections and neuroses—some glorious, some troubling, but all branded with the unmistakable id of their creator.

Allen has pondered the possibilities of moral justification for murder before, often using Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment as inspiration (the novelist is mentioned in Irrational Man, and Crime and Punishment was the basis for Allen’s 1989 movie Crimes and Misdemeanors, in which a character, Judah, hires a hit man to kill his mistress after she threatens to reveal their affair to his wife). 2005’s Match Point had a similar storyline—a former tennis pro (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) murders his pregnant mistress (Scarlett Johansson) after she refuses to have an abortion. In both movies, the protagonist ends up getting away with the crime, and facing a happy and fulfilling future. Match Point, like Irrational Man, stands out mostly for its stilted dialogue and remarkably blasé attitude to murder, but it does contain attempts to wrestle with the concept of right and wrong. “It would be fitting if I were apprehended,” says Meyer’s character, Chris, in a voice-over. “At least there would be some small sign of justice—some small measure of hope for the possibility of meaning.” Crimes and Misdemeanors’s Judah, meanwhile, suffers from guilt about what he’s done before suddenly finding relief, as he describes to a friend on the premise he’s describing an idea for a screenplay.

After the awful deed is done, he finds that he’s plagued by deep-rooted guilt … Suddenly it’s not an empty universe at all but a just and moral one, and he’s violated it. He’s panic-stricken. He’s on the verge of a mental collapse—an inch away from confessing the whole thing to the police. And then, one morning, he awakens. The sun is shining, his family is around him, and mysteriously, the cloud has lifted.

Given that he’s a philosophy professor, Irrational Man’s Abe doesn’t spend much time analyzing the moral justification of his desire to kill Judge Thomas Spangler. And (spoilers ahead) after he does, he’s completely invigorated by the act. Allen, a devoted Freudian, seems to present Abe as having an imbalance between his life and death drives. In the first part of the movie, he lacks a will to live, drinking single-malt Scotch all day, telling Jill that he’s too far gone to ever find love, and finding himself physically unable to consummate an affair with a chemistry professor (Parker Posey). In one scene, he grabs a gun and plays a game of Russian roulette with himself in front of a group of his horrified students. “He’s so self-destructive, but he’s so brilliant,” coos Jill.

Related Story

To Rome With Love, and Exhaustion

Killing a man, somewhat neatly, gives Abe newfound zest for life. He regains his appetite, he overcomes his reluctance to have an affair with Jill, and he also gets his libido back. “What happened to the philosophy professor?” Posey’s character asks in one post-coital scene. “You were like a caveman.” Freud’s theory was that the tenets of civilized society frequently clash with man’s libidinal urges, forcing him to repress them, which in turn leads to neurosis. Freed from moral restriction, Abe is newly liberated, kissing Jill publicly at a concert, taking her to the beach, and feasting on French toast at a diner instead of his usual coffee.

The film critic David Thomson has described Allen as “a major-league fantasist, in which he is the central figure,” adding that “his mingling with attractive actors and actresses has been an immense fantasy inspiration to him.” Irrational Man fantasizes about murder, but also, less intriguingly, about its protagonist being an object of extraordinary desire to everyone he meets. The news of his arrival on campus is buzzed about by students and teachers alike. “I hear he has affairs with his students,” says one young woman excitedly, while an older professor remarks that the appointment will “put some Viagra in the philosophy department.” Upon arrival, Lucas has the charisma and heavy-lidded, wackadoodle charm of Phoenix, but he’s also a mess—overweight, sweaty, and inebriated. Still, neither his washed-up appearance nor the uninspired nature of his classes (“Philosophy is verbal masturbation,” he tells his students) seems to lessen his appeal.

Phoenix is just the latest actor to play a stand-in for the larger character of Allen, given that at 79, the director is now too old to plausibly play himself as a sex object. But this is a fairly recent concession. In 1996, at the age of 61, he successfully wooed the 29-year-old Julia Roberts in Everyone Says I Love You, the year after he had an affair with Mira Sorvino’s 20-something prostitute in Mighty Aphrodite. In 1979’s Manhattan, Allen’s 40-something character, Isaac, dates a 17-year-old schoolgirl played by Mariel Hemingway (the film is believed to be based on Allen’s real-life experiences dating 16-year-old Stacey Nelkin, whom he met on the set of Annie Hall and dated while she was attending Stuyvesant High School). In her 2015 memoir, Out Came the Sun, Hemingway describes how Allen invited her on an unchaperoned trip to Paris shortly after she turned 18. “Our relationship was platonic, but I started to see that he had a kind of crush on me, though I dismissed it as the kind of thing that seemed to happen any time middle-aged men got around young women,” she writes.

The secondary problem with Allen’s filmmaking as a romanticized expression of his id is that it spawns art that just isn’t very good.Even putting aside the ethical concerns about Allen, the allegations by Dylan Farrow, and the long list of films he’s made about men having preoccupations with much younger women (2014’s Magic in the Moonlight paired 53-year-old Colin Firth with 25-year-old Emma Stone, while Phoenix, by contrast, is only 14 years older then her), the secondary problem with Allen’s filmmaking as a romanticized expression of his id is that it spawns art that just isn’t very good. Irrational Man is turgid to the point of ridiculousness and absurdly anachronistic—having not bothered to research what it might be like living on a 2015 college campus, Allen’s Braylin is an institution from 50 years ago, in which teachers sleep with students without consequence, philosophy lecturers are rock stars, people idly skim through hardback books in the library, and Jill’s piano recital is the social event of the week. Allen’s dialogue, when spoken by actors who aren’t exactly like him, inevitably sounds like a poorly drafted student play, and even Phoenix, one of the most gifted actors of his generation, struggles to make it sound plausible. (“My brief time working on elevators during my college days might now pay off” is how one particularly important scene is introduced.)

These manifestations of inner turmoil might be cathartic for the filmmaker, but they’re inevitably awful to watch—2007’s Cassandra’s Dream is a particularly poorly realized attempt to give the lives of two working-class brothers mythological significance. By contrast, when Allen pays homage to other artists or other eras, like Tennessee Williams in Blue Jasmine, or the thriving artist’s paradise of the Roaring ’20s in Midnight in Paris, he’s able to spin his stories into something more ambitious, and more intellectually worthwhile.

Perhaps ironically, given that he reliably churns out a movie each year, the adjective most consistently applied to Allen these days is “lazy.” Magic in the Moonlight, wrote Variety’s Justin Chang, is “world-weary to the point of exhaustion. Characters don’t interact so much as stand about rattling off plot points and moral positions, as if the effort required to actually dramatize something—as opposed to merely shoving it into the mouth of the nearest bystander—would cause the whole thing to collapse.” Allen himself concurs, telling a press conference in 2007, “I’m not a dedicated filmmaker, I’m lazy. To me, making a film is not the be-all end-all of my life. I want to shoot the film and go home and get on with my life.” For as long as he’s able to make his movies in a couple of weeks and demand very little from his actors, he’ll continue to draw stars of Phoenix and Stone’s caliber to his projects. But for audiences, there’s an increasing queasiness associated with his films, and their insistence on presenting Allen’s personal moral quandaries as art.

Taylor Swift and the Silencing of Nicki Minaj

The most important word in the Twitter drama that unfolded last night between Nicki Minaj, Taylor Swift, and their respective fan armies was “Huh.” As in Minaj’s only direct reply to Swift: “Huh? U must not be reading my tweets. Didn't say a word about u.”

Minaj had been arguing on social media that the MTV Video Music Awards hadn’t properly recognized her clips for “Anaconda” and “Feeling Myself” in its nominations. Most relevantly, Minaj said that because “Anaconda” created a viral phenomenon that spread from red carpets to cathedral steps, it seemed strange it wasn’t up for Video of the Year. “When the ‘other’ girls drop a video that breaks records and impacts culture they get that nomination,” she wrote. “If your video celebrates women with very slim bodies, you will be nominated for vid of the year.” Then she posted a bunch of smiley faces.

Related Story

Though her name wasn’t mentioned, Swift took this as an act of aggression. Her “Bad Blood” clip is nominated for Video of the Year, alongside works from Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, Mark Ronson, and Ed Sheeran. “I've done nothing but love & support you,” she tweeted to Minaj. “It's unlike you to pit women against each other. Maybe one of the men took your slot.” Cue hundreds of people making the obvious joke at the same time.

To the public, the actual awards at the Video Music Awards usually seem irrelevant compared to its ceremony’s spectacles—Madonna’s makeout, Miley’s twerking, etc. But whether it’s the VMAs or the Emmys or the Grammys or the Oscars, the last few years have made clear that accolades some people deride as arbitrary and silly still hold a lot of meaning for artists who feel condescended to by the entertainment industry. Recently, black creators in particular—the Empire showrunner Lee Daniels, the Selma director Ava Duvernay—have called out perceived snubs that, at the very least, fit a documented pattern of exclusion for minorities.

If anyone should be expected to speak out on this subject, it’s rappers—like Minaj—whose art is in large part about standing up for their own worth. The VMAs, remember, were where Kanye West objected to Swift getting a prize over Beyoncé (he may have opportunity to do so again—“7/11,” like “Single Ladies,” really is “one of the best videos of all time—one of the best videos of all time!”). Last night, the MTV nominations set off a tweetstorm for another emcee, Minaj’s boyfriend Meek Mill, who said, “I don't really trip about the awards... I know they gone give em to the white kids doing it.... That's why we buy Rollie's and shit our own trophies!”

You can debate whether the “Anaconda” video is brilliant or bad, but you can’t argue with Minaj that it was one of the most iconic pop-culture products of the past year, nor with the idea that a lot of people had a knee-jerk negative response to its glorification of big black butts. Her speaking up about those things doesn’t mean she’s dissing the other nominees. Yes, the video she’d most likely been referring to when talking about “slim bodies” was “Bad Blood,” a montage featuring a lot of supermodels and skinny actresses in superhero getups. But she didn’t question its merit; she even implied that it was commercially and culturally significant.

When Swift chimed in, it changed the conversation from woman versus institution to woman versus woman. Ironically, this is exactly the complaint Swift leveled against Minaj: “It's unlike you to pit women against each other.” This fits with Swift’s recent campaign against the Mean Girls stereotype of women as catty infighters; her 1989 shows have featured clips videos of her famous buddies telling the largely tweenage girl audience about how great same-sex friendship can be. The cause is righteous, but Swift’s tweet to Minaj shows the limits of it. When female solidarity shuts down someone’s honest expression of frustration at society, inequality, and racial and body-type bias, that’s hardly progressive.

Minaj doesn’t seem to want there to be any bad bl—um, hurt feelings between the two stars. “I love u just as much,” she wrote in her reply to Swift, before sending some tweets about feeling mistreated by “white media” and retweeting followers talking about the race and music. Swift’s only other comment was a reminder of her own success and another assertion that friendship could fix all problems: “If I win, please come up with me!! You're invited to any stage I'm ever on.” Huh?

Martin O’Malley’s Link Between Climate Change and ISIS Isn’t Crazy

It’s the dog days of summer for U.S. presidential candidates, when Donald Trump is dominating the airwaves and candidates who seem to be losing their purchase at the polls are doing whatever they can to capture some attention—whether that’s taking a chainsaw to the tax code, like Rand Paul, or claiming there’s a connection between ISIS and climate change, like Martin O’Malley.

“One of the things that preceded the failure of the nation-state of Syria and the rise of ISIS was the effect of climate change and the mega-drought that affected that region, wiped out farmers, drove people to cities, created a humanitarian crisis that created the symptoms—or rather, the conditions—of extreme poverty that has led now to the rise of ISIL and this extreme violence,” the Democratic candidate told Bloomberg on Monday.

Actually, hold that thought on O’Malley. His comment was noted by the Republican opposition-research organization America Rising and promptly mocked by conservative media outlets. The Republican National Committee issued a statement ripping O’Malley, which he was probably happy to get.

But O’Malley’s comment isn’t as weird as it might initially seem. There’s an established body of work that draws a connection between drought, resource scarcity, and conflict in general. In a 2013 article for The Atlantic, William Polk, a historian and former adviser to President Kennedy, noted a possible relationship between Syria’s civil war and devastating 2006-2011 drought. “As they flocked into the cities and towns seeking work and food, the ‘economic’ or ‘climate’ refugees immediately found that they had to compete not only with one another for scarce food, water, and jobs, but also with the existing foreign refugee population,” he wrote. “Formerly prosperous farmers were lucky to get jobs as hawkers or street sweepers. And in the desperation of the times, hostilities erupted among groups that were competing just to survive.”

In addition, a paper published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences specifically connects a severe drought across the Levant to the Syrian conflict.

The case isn’t a direct one. “Before the Syrian uprising that began in 2011, the greater Fertile Crescent experienced the most severe drought in the instrumental record,” the authors write, arguing that the drought is connected to a long-term change in the climate in the Eastern Mediterranean. “For Syria, a country marked by poor governance and unsustainable agricultural and environmental policies, the drought had a catalytic effect, contributing to political unrest.” ISIS existed in different form, as the Islamic State of Iraq, prior to the outbreak of the civil war, but the collapse of the Syrian state, combined with the fecklessness of the Iraqi armed forces and government, allowed the group to expand its reach and influence, and declare a caliphate.

“In the desperation of the times, hostilities erupted among groups that were competing just to survive.”Of course, scientists and security consultants get nervous when the media covers studies such as this one. They worry, in particular, about the impression that wars can be reduced to a single cause. (As one told The Guardian in May about the PNAS study, “I’ll put this in a crude way: No amount of climate change is going to cause civil violence in the state where I live (Massachusetts), or in Sweden or many other places around the world.”) Still, O’Malley did a pretty good job compressing the study’s findings into a short explanation and contextualizing it as creating the conditions for ISIS’s success, rather than drawing a direct causal link between climate change and the Islamic State.

It’s easy to see how the baldest summary of this claim—a presidential candidate says that global warming created a huge jihadist group!—comes across as silly. But the unfortunate reality is that climate change will likely produce more evidence in the years ahead of the connection between resource scarcity and war—whether it’s fodder for presidential campaigns or not.

Between the World and Me: 10,000 Years From Tomorrow

Over the next few weeks, The Atlantic will be publishing a series of responses to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. (An excerpt is available online.)

This is the second in a series. Readers are invited to send their own responses to hello@theatlantic.com, and we will post their strongest critiques of the book and the accompanied reviews. To further encourage civil and substantive responses via email, we are closing the comments section. You can follow the whole series on Twitter at #BTWAM, or to read other responses to the book from Atlantic readers and contributors.

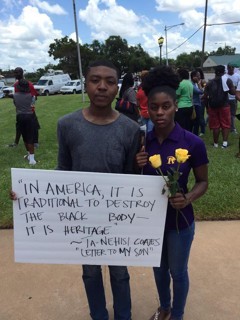

“Here is what I would like for you to know,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes to his son, Samori, in Between the World and Me: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage.”

The violence to which Coates refers encompasses slavery, the terror of Jim Crow, and police brutality right up to the present moment. And in his new book, as in his previous work, Coates insists that no amount of “personal responsibility” on the part of African Americans can shield them from it.

This truth was brought home to him by the death of Prince Jones, one of Coates's Howard University classmates, who was killed by a suburban-Maryland police officer in 2000. The officer claimed that he shot Jones in self-defense after Jones tried to run him over with his Jeep. It’s a story that the authorities accepted but that Coates does not.

Responses to Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and Me

Responses to Ta-Nehisi Coates's Between the World and MeRead More

The crucial thing to understand about Prince Jones is this: In a society that promised to reward talent and effort, he and his family had done more than hold up their side of the bargain. His mother, Mabel Jones, was raised poor but swore that she wasn't "going to live like this" all her life. She made good on the pledge, eventually winning a full scholarship to Louisiana State University en route to a career as a radiologist. Her son, Prince—a Howard graduate, a man of faith—did his part, too. But none of that was enough to protect him.

Reading Coates’s words transported me back to a conversation I had with my father, a lifelong civil-rights activist, in 1992. The topic, you might say, was my Prince Jones—Rodney King, who was savagely beaten by members of the Los Angeles police force. Even though their actions were captured on video, the officers were acquitted.

What was the point of a career learning to craft and apply rules if, just when you needed them, they turned out to be a sham?I had just graduated from law school, and I told my dad that the case made me doubt my career choice. I had gone to law school thinking that I would do something in the service of black people. But what was the point of a career learning to craft and apply rules if, just when you needed them, they turned out to be a sham?

My dad said something vaguely reassuring, but I was young and hard-headed, and his words just made things worse. So I drew from his own life to prove the pointlessness of struggle.

Back when he was about my age, my dad had been stopped by the L.A. police near the campus of the University of Southern California, where he was a student. They told him they wanted to question him about a robbery. Despite the fact that he had been sitting in a nearby campus library when the robbery took place, they refused his pleas to take the simple step of walking inside to confirm his presence with the librarian at the desk. My dad was outraged by their refusal, and their insistence that he come to the precinct for questioning. But, as he would later write in his memoir, “It was hopeless. They had the guns.”

They took him to a cell, and after he began mouthing off about his rights and the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence (he was studying political science, and I got my hard-headedness from somewhere), the police did what they did to black people—which is to say, whatever they wanted. They held him for days, beat him to the bone, and interrogated him without mercy. (“We're tired of you Chicago niggers coming out here to the coast and robbing and going back to Chicago.”) Eventually, when it became clear he wouldn’t confess to a crime he hadn’t committed, they dumped him on the street outside the precinct with no money and no way to get home.

This had happened to my dad in 1953. If Rodney King, almost 40 years later, could be beat down like this, on camera, and still nothing was done about it, surely my dad had to see that nothing had changed—and that nothing ever would.

What he said to me then, and what he didn’t, surprised me. I expected my dad to point out, as he often did, all that had changed since he was my age. And of course, he would have been right: I lived a life of freedom and opportunity unimaginable to his generation, and I never forgot, or will forget, that his struggle made my world possible.

He said that none of his fights were ones that he thought he would win in his lifetime. Or even mine.But on this day, my dad answered differently. Maybe his characteristic optimism had been dealt its own blow when Rodney King’s attackers were exonerated. Maybe he sensed that my despair called for deeper wisdom. But whatever the reason, he decided to talk about the permanence of injustice. He said that none of his fights were ones that he thought he would win in his lifetime. Or even mine. He was fighting, he said, “for 10,000 years from tomorrow.” And he turned my story on its head: He said that the fact that the L.A. police were still abusing black people, the fact that I could draw a line from him to Rodney King, was precisely why we had to keep fighting.

The memory of my dad's words, in turn, brings me back to Coates. As a writer and as a father, Coates is clear-eyed about the obstacles arrayed against black people. He warns Samori that “there is no uplifting way” to tell his story, that he comes with “no praise anthems, nor old Negro spirituals.” And yet, he urges his son to keep fighting. “Struggle for the memory of your ancestors,” he writes. “Struggle for wisdom ... Struggle for your grandmother and your grandfather, and for your name.” At another point, he writes, “the struggle is really all I have for you because it is the only portion of the world under your control.”

This exhortation echoes remarks Coates made last fall in an interview with The Root:

It would be absolutely just, like, the highest sort of wrong, a moral betrayal, to retreat to a corner and curl up in a fetal position. Even if I believed there was no hope at all. Resistance, in and of itself—struggle, in and of itself—is rewarding.

It’s very tough to explain that to people. It’s hard to get that across, ’cause I think we feel like, well, if this isn’t gonna get fixed, and we don’t feel like it’s gonna get fixed, what are we struggling for? But for me the question is, well, what is your life about? What are your values? How do you want your life spent? And I want my life spent struggling. This is how I want to live.

From Twitter

From Twitter Members of a new generation are making that choice. Recently Coates retweeted a message from a demonstration protesting the death of a black woman, Sandra Bland, in a Texas jail: “@tanehisicoates gave me the language to protest for #SandraBland today in Waller, TX.” Accompanying the tweet was a picture with two young people holding a sign quoting from Between the World and Me.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower