Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 381

July 29, 2015

Desperate Republicans

Any day now, Rick Santorum is going to gyrocopter into the White House and try to make a citizens arrest. That’s how desperate the GOP presidential hopefuls not named Trump, Bush, Walker and Rubio are for attention. Every four years, the Republican base creates a market for crazy. But this year, with 16 GOP candidates, being crazy enough to get noticed is a lot harder. And with only a week to go until Fox News decides who gets to participate in the first presidential debate, candidates in the GOP’s second and third tier are growing frantic.

In the last few days alone, Mike Huckabee has accused Barack Obama of orchestrating a second Holocaust, Ted Cruz has called the Republican senate majority leader a liar, Rand Paul has set the tax code on fire, and Lindsey Graham has ground up his cell phone in a blender. Bobby Jindal, ever precocious, suggested abolishing the Supreme Court in late June.

Obviously, the size of the GOP field helps explain these antics. With so many candidates, attracting media coverage was always going to be hard. Then Donald Trump jumped into the race, and between late June and late July single-handedly accounted for 62 percent of the Google-search traffic devoted to Republican presidential candidates.

Fox News has made the problem worse. It’s only allowing 10 of the 16 GOP hopefuls into its prime-time August 6 debate; the others get a shorter consolation debate earlier in the day. That means little-known candidates may lose their best chance at a free introduction to the American public, and be written off by the punditocracy six months before anyone casts a vote. By determining who makes the cut based on national polls, Fox has made name recognition the summer before an election more important than in the past, and made candidates desperate to boost their own.

Related Story

Super PACs Are for Republicans, Campaign Cash Is for Democrats

And there’s another factor: money. In past cycles, candidates like Mike Huckabee in 2008 and Rick Santorum in 2012 have won Iowa, despite having relatively little money, by painstakingly building a network of activists on the ground. In the age of the Super PAC, that’s much harder, because the financial gap between scrappy underdogs and well-funded front-runners is much larger. In 2008, Huckabee won Iowa despite having raised almost 17 million less in the second quarter of 2007 than the flushest candidate, Rudy Giuliani. In 2012, Santorum won Iowa despite having raised almost 18 million less in the second quarter of 2011 than the flushest candidate, Mitt Romney.

But when the presidential contenders announced their second quarter hauls earlier this month, the gap between Huckabee and the flushest candidate, Jeb Bush, was $106 million. (The gap between Bush and Santorum was $114 million). The fundraising ratio between rich and poor candidates hasn’t changed much. But as the numbers have exploded, so has the gap. That means besting Bush (or another well-funded front-runner like Scott Walker), with a shoestring campaign, in the way Santorum bested Romney in 2012, is far more difficult.

In past years, candidates engulfed by negative media attention often tried to defuse the story. This year they double down.I suspect there’s another reason that candidates are so desperate for national media attention: They know it’s harder to do well by flying under the radar this year. It’s also the reason that, having said something outrageous, this year’s candidates are less likely to back down. When President Obama called Huckabee’s Holocaust comments “ridiculous” and “sad,” the former Arkansas governor’s campaign quickly hit back with an online video that garnered more than 30,000 views in 40 minutes. In past years, candidates engulfed by negative media attention often tried to defuse the story. This year they’re so desperate for the spotlight that they double down.

It’s anyone’s guess when we’ll hit bottom. “In Bid to Take Attention from Trump, Other Fifteen Hopefuls Release Joint Sex Tape,” wrote Andy Borowitz on The New Yorker’s website on Wednesday. I had to read it twice before I realized it was a joke.

The Aging Stars of Major League Soccer

A year ago, at the twilight of a spectacular soccer career playing in England’s Premier League, the midfielder Frank Lampard announced that he had signed with a team that had never kicked a ball before—a team with no history but thousands of fans and very deep pockets. New York City FC, the newly accredited arm of oil-rich Manchester City’s now-global sporting operation, had snagged not only Lampard but Atlético Madrid’s David Villa, another superstar player close to the end of his career. In doing so, the novice club upped the ante on every other team in Major League Soccer.

Related Story

Americans Still Don't Care About Soccer

In its post-David Beckham years following the former England captain’s retirement in 2013, MLS had seemed to be weaning itself off aging international superstars, even tempting American players home from Europe. Beckham had been MLS’s first major signing when he joined the L.A. Galaxy in 2007, in a deal worth $6.5 million a year that helped raise the profile of soccer in the U.S., despite the player spending much of his contract on loan overseas. Without him, and with Michael Bradley and Clint Dempsey, two of the biggest-name American players of the last decade, ensconced in the league, MLS finally had an opportunity to focus on nurturing domestic talent.

But the Beckham effect, which significantly boosted both attendance and sponsorship revenue within MLS, hadn’t gone unnoticed by club owners. Soon came Lampard (37), Villa (33), Liverpool’s Steven Gerrard (35), Juventus’s Andrea Pirlo (36), and A.C. Milan’s Kaká (33), followed this week by Chelsea’s Didier Drogba (37) and QPR’s Shaun Wright-Phillips (33). Any squad fielding these players as a singular force ten years ago would have been considered one of the best teams of all time. Their combined trophies are too numerous to list. And yet, when they take the field, players earning in a year what these superstars make in a week will be passing them the ball, tidying up the play behind them, and doing the running their aging legs can’t.

On the one hand, such an injection of European stardom promises renewed interest in MLS, which has already benefited from the boost of two World Cups in successive years. But the exorbitant salaries being paid to players long past their prime raises the question of whether the league is suffering from short-termism in its thinking. Can MLS, which aims to rival the best leagues in the world by 2022, capitalize on its global stars while capably fostering the next generation of American players, and securing its own future?

* * *

Last month, when the former Bayern Munich star Franz Beckenbauer was asked whether the star German player Bastian Schweinsteiger should leave his home country for the Premier League, Beckenbauer’s response was telling. “Schweinsteiger still has one or two more years at the highest level in him,” he said. “If he still feels like playing football then, I would advise him to consider a move to MLS and to New York.”

For the European footballer in his 30s whose goals are drying up, and whose prospects include retirement or coaching younger players, MLS is a refuge with a very generous paycheck, safe from the scrutiny and pressure associated with playing in Europe. But the question for American soccer fans is whether they should feel comfortable with a professional league that’s the sporting equivalent of a Vegas residency for aging A-list musicians: essentially a retirement home with low stakes and a high payout.

Having such big fish play for such typically low-profile teams raises MLS’s profile overseas, but the league’s huge disparities in terms of talent, fame, and paychecks makes for some comical juxtapositions. Before he quit soccer at the end of 2014, the New York Red Bulls striker Thierry Henry (France’s leading goalscorer of all time) was partnered with Bradley Wright-Phillips, a player who moved to the U.S. following a couple of months on loan at the League One club Brentford.

Perception, in this case, is reality to European soccer fans. No amount of defeats in meaningless pre-season friendlies to MLS sides will alter their understanding of a league where European dropouts can succeed so spectacularly. While this characterization is, in more than a few cases, unfair, MLS’s long-term plan for sustainability is still a little baffling.

Should American soccer fans feel comfortable with a professional league that’s essentially a retirement home for European stars?Some of the blame has to lie with the American sporting tradition of fairness in structure, a concept alien to the billionaire owners of the European game. Even if Bill Gates were to establish an MLS team tomorrow, Roman Abramovich-style, he could never hope to stock it with a squad rich enough to compare to top European sides, simply because of the salary cap and designated player system. In being allotted a maximum of three players who are exempt from a team-wide salary cap (which altogether would barely cover the individual paychecks of Europe’s best individual players), MLS is geared towards having teams of workmanlike, poorly compensated footballers along with a smattering of superstars. Designated player salaries take a few hundred thousand dollars from the overall salary cap (a sum paid to players by the league), with the remainder, often a few million dollars, being picked up by the club owners. This system is at once both laudable and insular, preserving internal competitiveness while crippling it externally.

But American soccer has always had to struggle with the differences between local sporting tradition and global sporting norms. With its most popular sports played in America and hardly anywhere else, expectations from how those sports are structured were foisted onto soccer. Until 1999, soccer in the U.S. still mandated that each individual game have a winner, with MLS employing a variation of the ice-hockey-style penalty shoot-out to settle even league games.

The structure of a professional league like MLS is based on the ability to dictate terms before the product is created. No doubt, if Europeans could go back and start again many of them would agitate for a system that doesn’t allow one or two teams to dominate as ruthlessly as the Spanish hegemony does, for example. It’s a noble ideal, but in a global marketplace where money flows from oil pipelines into football stadiums with almost no restriction, it’s the fastest way the U.S. could go about restricting the ability of its teams to compete on a global level.

Mike Segar / Reuters

Mike Segar / Reuters Maybe competing with Europe isn’t the whole point. Perhaps, by limiting at least partially the amount of money an owner can spend on a team, MLS is instead trying to build a future where the game’s increasing popularity (thanks to big names) equals more young athletes choosing soccer over baseball or football, which in turn translates into success on the global stage. There’s an assumption that all it would take for the men’s game to explode in the U.S. is one World Cup victory.

But for a century of sporting tradition to be overturned, it will take something far more seismic than a series of internal dominoes toppling. MLS, which is much closer in revenue to the Canadian Football League than the four major U.S. sports leagues, is so far behind in terms of audience share and TV revenue that to become a priority in the U.S., both in the hearts of viewers and athletes, may require the wider sporting landscape to change irrevocably—more than even Lampard, or Villa, or Gerrard can allow.

* * *

What, then, of the young men earning an office manager’s salary to pass the ball to Andrea Pirlo? The minimum annual salary in MLS, until quite recently, was $36,500, an almost unbelievably tiny amount for a job that involves playing professional sports in the richest nation on earth. It currently stands at $60,000 a year, the kind of salary a player might expect to receive in the lower reaches of the English game, at clubs playing in front of a couple of thousand fans a week.

It’s not exactly a feast higher up the food chain, either. Average salaries in MLS rank 22nd in the world, below the Greek and Ukrainian leagues, even before the distorting effect that superstar salaries have on that number is taken into account. Minimum salaries are now fixed for the next five years. In the meantime, aging imports who don’t take MLS seriously are banking obscene paychecks while the future players of the national team are barely making enough to buy a house.

In 2014, MLS stood at a crossroads. With a five-fold increase in TV money in its pocket, it could have invested in the American game by upping wages to a competitive level. Beckham and Henry had gone, Bradley and Dempsey were back, support was at an all-time high, and the USMNT was about to prove its worth globally. Instead, the 2015 season will see Europe’s best players of half a decade ago trying to win a trophy that’s largely meaningless to them, drifting around Montreal and Houston, dreaming of the Champions League.

Unless MLS’s next bargaining agreement allows owners to build a squad, rather than restricting their investment to lower-division professionals with a handful of stars, it’s hard to imagine how both the league and the U.S. game can realistically compete long-term with the rest of the world.

The Soul of the Metallica Lover

For anyone who has ever caught some treacly adult contemporary on the radio and wondered “Who on earth likes this stuff?” while twisting the dial, a new study might have an answer. A bunch of softies, that’s who.

In the paper, published recently in the online journal PLoS One, Cambridge psychologist David Greenberg theorized that music tastes are determined in part by peoples’ tendency to fall into one of two rough personality categories: empathizers or systemizers. Empathizers are people who are very attuned to others’ emotions and mental states. Systemizers are more focused on patterns that govern the natural and physical worlds.

Over the course of multiple experiments that included 4,000 participants, listeners took personality questionnaires and then listened to and rated 50 pieces of music.

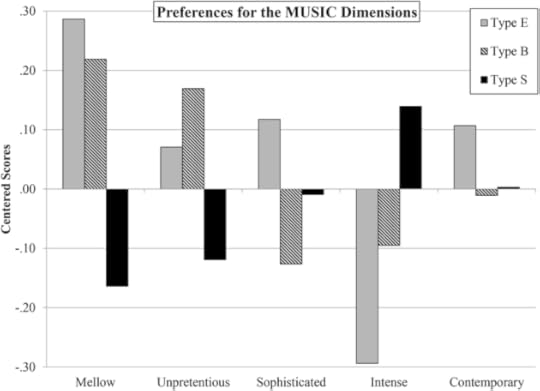

Greenberg found that people who scored high on empathy tended to prefer music that was mellow (like soft rock and R&B), unpretentious (country and folk), and contemporary (Euro pop and electronica.) What they didn’t like, meanwhile, was “intense” music, which he classified as things like punk and heavy metal. People who scored high on systemizing, meanwhile, had just the opposite preferences—they kick back to Slayer and could do without Courtney Barnett.

Type “e” are empathizers; type “s” are systemizers; type “b” are in between. (PLOS)

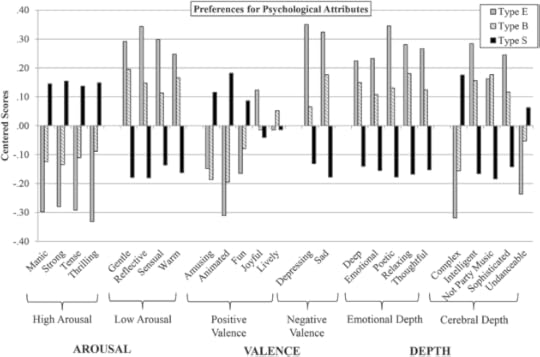

Type “e” are empathizers; type “s” are systemizers; type “b” are in between. (PLOS) To get even more specific, the music empathizers liked tended to be softer, more depressing, and have more emotional depth. Systemizers, meanwhile, grooved to things that were high-energy, animated, and complex. Empathizers liked strings; systemizers liked distorted, loud, and “percussive.”

Preferences for various music qualities, by personality type. (PLOS)

Preferences for various music qualities, by personality type. (PLOS) They also came up with some, uh, playlists for people who find themselves solidly in either the empathizer or systemizer category.

High on empathy:

“Hallelujah” – Jeff Buckley “Come Away With Me” – Norah Jones “All of Me” – Billie Holliday “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” – QueenHigh on systemizing:

Concerto in C – Antonio Vivaldi Etude Opus 65 No 3 — Alexander Scriabin “God Save the Queen” – The Sex Pistols “Enter Sandman” – Metallica* * *

Music taste has long been thought to offer a window to the soul. (Past research has found, for example, that open-minded people are more likely to enjoy the blues, jazz, and folk, while extraverts like pop, electronica, and religious music.) It’s why people at parties ask each other “What music do you listen to?”

Still, this study doesn’t account for the fact that the answer to that question is, more often than not, “A little bit of everything.” Many people listen to Avicii when they run and to Bon Iver when they’re writing a memo in an open-plan office. It’s hard to imagine someone who listens only to Norah Jones on loop—although I would like to meet that person and ask them for stress-management tips.

The results could still be helpful, though, when it comes to things like understanding autism (some think people with autism are just extreme systemizers), or in determining whether listening to different types of music could help people build empathy.

Or, perhaps less nobly but more lucratively, the findings could be useful for companies like Pandora and Spotify.

“A lot of money is put into algorithms to choose what music you may want to listen to,” Greenberg said in a release. “By knowing an individual’s thinking style, such services might in future be able to fine tune their music recommendations to an individual.”

The Road Rage of a Narcotics Detective

Three years ago in Medford, Massachusetts, narcotics detective Stephen LeBert calmly told the brother of a man he was arresting, “He’s selling drugs illegally. What they should do is just take him up to the railroad tracks and tell him to lay down.” He knew he was being recorded as he made the comment, as moments earlier, the footage shows him licking his finger and wiping saliva on the citizen’s lens. Medford Police Chief Leo Sacco says that he was counseled after the incident.

After watching that video, it comes as no great surprise that Detective LeBert was suspended earlier this week for another instance of misbehavior recorded by a citizen:

The footage, captured by the dashboard camera on a motorist’s vehicle, begins shortly after the driver got confused at a roundabout in an unfamiliar neighborhood and wound up briefly driving on the wrong side of the road (an error for which he would repeatedly apologize). At first, the motorist is terrified and starts to flee because Detective LeBert, who is driving an unmarked pickup truck and plainclothes, does not identify himself as a police officer, even as he is upset that the motorist doesn’t defer to him. “I’ll put a hole right through your fucking head,’’ LeBert says. “Pull your car over. I’ll put a hole right in your fucking head. I’ll put a hole right through your head.’’ The motorist begins to cooperate as soon as a badge is produced.

“You’re lucky I’m a fucking cop,” LeBert says. “Cause I’d be beating the fucking piss outta you right now.”

Police Chief Leo Sacco has put LeBert on administrative leave and expressed discomfort at the behavior captured on video. It’s easy to imagine an uglier ending to the very first part of the video, when the motorist was being threatened by a stranger with no way of knowing that he was a cop; and it’s unnerving to think of a man who cannot control his temper in traffic being vested by the state with the power to use lethal force. But there’s something else about the video that bothers me.

Boston’s ABC affiliate notes that towards the end, “LeBert, who was not in uniform, called other Medford police officers, who are recorded as handling the situation calmly and telling the driver that he will receive a summons for the traffic violation.”

But notice what those other, admirably polite police officers don’t do.

“Can I talk to you guys a little more?” the motorist asks them after they tell him that he’s free to go. At this point they’ve had a long, polite interaction with one another, and established the motorist did nothing wrong save a minor traffic infraction.

“Like I said,” the motorist tells them, “I have a dashcam and everything is recorded. I mean, this guy jumped out and he’s yelling that he’s gonna blow my brains out.”

Appropriate responses might include, “Are you saying that detective over there verbally threatened your life?” or “Would you like to file a complaint?” or “Would you be willing to come down to headquarters so that we can take a look at what happened?”

Here’s what happened instead.

“All right, he already informed you that he’s going to issue you a citation,” the polite police officer said. “So there will be a box on the back to check off that you wish to make an appeal and you can bring all that up when you go to appeal the ticket.”

Then Detective LeBert can be heard again, taunting the motorist to bring the dash-cam footage that shows his dangerous driving. And the polite police officer tells the motorist, “The longer you stay here the more trouble you’re just going to get into, so the stop has ended, you’re all set, you’re free to leave.” If I were a purist, I’d complain that the polite police officer shouldn’t tell a citizen who isn’t breaking any law that he’ll get in more trouble by asking questions about another cop’s misconduct. Since I’m a pragmatist who recognizes that a bully of a cop with a hot temper was still on the scene, I see the wisdom in urging our motorist to move along, and would be happy if he’d only reported on his colleague when he got back to the station.

But news accounts suggest Detective LeBert was only caught and suspended when the clip appeared online, so it seems like the polite police officers failed to do anything about misconduct by a colleague severe enough that the police chief put him on leave after seeing it. One wonders how many times Medford cops who’d never behave that way covered for their colleague. All who have bear a measure of responsibility for his behavior, which is an embarrassment to their department and their profession.

If police officers want to rebuild their image in the era of YouTube, they’d do well to respond as if they’re upset when fellow cops behave unprofessionally. America is watching.

What Ever Became of Ben Carson?

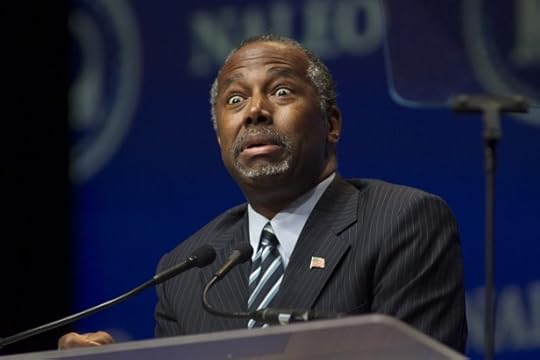

Remember Ben Carson? Medical hero? Scolded Obama? Occasional propensity to deliver ill-advised non-sequiturs? Ringing any bells?

When The Washington Post’s Philip Bump asks who has lost out as Donald Trump has risen in polls, it seems to me that Carson is the most obvious loser. Look at this chart, from HuffPost Pollster, of the two candidates’ polling averages:

Ben Carson vs. Donald Trump

To be fair, Carson isn’t the only candidate who’s fared poorly since Trump’s announcement. Here’s the same chart, adding Marco Rubio and Rand Paul:

Carson, Rubio, and Paul vs. Trump

But even if the numerical losses for Rubio and Paul have been bad, they don’t function quite the same way. First, Carson’s numbers start to turn south right around the time Trump’s shoot up—whereas Rubio and Paul’s had already peaked or were flat. Rubio’s game is a long one, and Paul’s struggles are a stranger and more interesting case. They’re also both U.S. senators, whereas this is Carson’s first foray into elections following a decorated career as a neurosurgeon. At his peak, Carson was running a solid fourth in the race, almost cracking double digits. While it would have been impossible to find someone unrelated to Carson, or not named Armstrong Williams, who would have predicted Carson winning the nomination then, he was a force to be reckoned with. He still seems like a lock for the August 6 debate in Cleveland, but he’s not what he was.

That brings us to the second point, which is that Carson’s particular struggle is that he filled a similar niche to Trump: The outsider who doesn’t come in with any political baggage, boasts of his success in his own profession, and appeals to voters attracted to a shoot-from-the-hip style. You can watch Trump suck up all the oxygen (and then some) that was feeding Carson’s success on Google Trends. Remember, before Trump entered the race and started making bizarre statements about Mexicans and John McCain, Carson was saying Obamacare was the worst thing since slavery and accusing the AP History curriculum of preparing teens to join ISIS. Both men share the basic partisan incoherence of non-politicians, taking positions associated with both parties—no vice, to be sure, though displeasing to staunch conservatives. Trump took Carson’s favorite campaign tricks and turned them up to 11.

Meanwhile, Carson’s fundraising—heavily focused on small contributions and direct mail—is faltering, while he continues to burn through the cash he has already raised.

The success of these two candidates shows a real hunger for people who aren’t traditional politicians. (Americans say they’re sick of career politicians, but when they express that preference by backing outsiders, pundits are suddenly confused!) But these outsider candidates seldom get anywhere near the nomination, and the Carson-Trump swap suggests there might not be room for two of them at any given moment.

What has Carson been up to? He criticized Planned Parenthood, but stumbled typographically in doing so. He's been raising a lot of money in Iowa. He expressed support for Obamacare’s practice of banning insurers from refusing patients with pre-existing conditions. And he defended none other then Donald Trump after Trump made light of McCain’s time as a prisoner of war. Maybe sticking up for the Donald wasn’t a great strategic move!

Or maybe Carson will rise again (after Trump burns out, perhaps). It wasn’t until September of 2011 that the 2012 election cycle produced the strange string of briefly popular Mitt Romney alternatives who grabbed headlines, then disintegrated: first Rick Perry, then Herman Cain, Newt Gingrich, and finally Rick Santorum. Since it remains hard to imagine Trump riding this gravy train all the way to the nomination, his rivals can console themselves with the thought that he may just be the first of a string of ephemeral candidates to surge to the lead. Republican insiders, though, may want to invest in some Alka-Seltzer.

July 28, 2015

How Archaeologists Dug Up a Human-Shaped Coffin That Wasn't There

A team of archaeologists and historians announced on Tuesday that they’ve identified the remains of four prominent men who died at Jamestown, the first permanent English colony in America, between 1608 and 1616—extraordinary news made even more intriguing by the discovery of a relic that suggests there were Catholics secretly living among the Protestants there.

But it wasn’t just what researchers found, but also how they went about finding it, that deserves attention. Piecing together a patchwork of evidence about daily life more than four centuries ago requires the right combination of technology, imagination, and luck.

“Five years ago, we wouldn't have been able to do it,” said William Kelso, the director of archaeology for the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation. Kelso was referring to the sophistication of some of the technologies that researchers used—scanning the ancient Catholic relic they found, then reanimating it in digital 3D, for instance. But even the best tools require a certain creativity about how to reconstruct the past.

The most striking example of this, to me, was the way researchers figured out the shape of an unusual coffin buried at what was once the first church built at Jamestown. It once held the remains of Sir Ferdinando Wainman, an officer at Jamestown who was in charge of his colony’s artillery and horses. Researchers were able to determine that Wainman had been buried in a human-shaped coffin—even though wooden structure itself had long-since decomposed. “An anthropomorphic coffin, that's very rare,” Kelso told me. “It would have taken a real skilled cabinet-maker to make it.”

So how did researchers identify the shape of something that had already disappeared? They took images of an entire block of dirt using “really powerful CT scanning,” and, from those images, they were able to tell by the positioning of coffin nails—the only bits still in the dirt—what shape the wood that held those nails had once been.

“It’s science and art,” Kelso said. “That's what historical archaeology is. The thing that’s so interesting about this discovery is it blends so many disciplines together in order to identify these people. Documentary searches, asking different questions about the same documents, searches in museum collections, looking at the archaeological context in which these people were found, forensic studies of the skeletal remains. It involves high-tech, state-of-the-art studies, really on the cutting edge of science.”

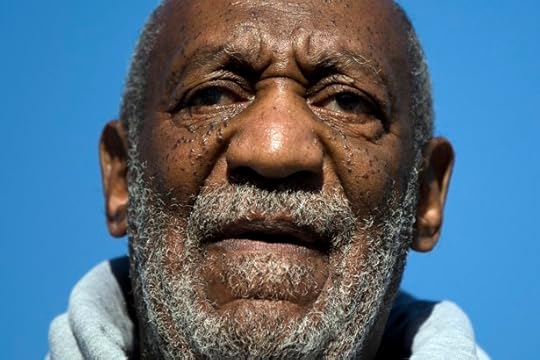

The Justice Bill Cosby’s Accusers Can’t Receive

Who still defends Bill Cosby? After newly unsealed depositions revealed that the comedian admitted to acquiring sedatives to give to women he wanted to have sex with, his longstanding backer Whoopi Goldberg recanted her support for the man accused of dozens of rapes over the years. The singer Jill Scott, too, said she was wrong when she suspected a media conspiracy against him. And if Cosby’s former costars, including Phylicia Rashad, still believe him to be the target of an illegitimate smear campaign, they haven’t spoken up to say so in a while. Cosby’s lawyer is currently making the rounds in the media to say his deposition has been misconstrued—but that argument, even if believed, doesn’t refute the idea that he used drugs to take advantage of women.

Related Story

Do Not Look Away From Bill Cosby

In this week’s New York cover story, 35 of Cosby’s accusers state their names, show their faces, and tell their stories. These are women from different walks of life—from supermodels to bartenders—whose tales of abuse are both painfully specific and horrifyingly familiar when placed next to each other. Even if statutes of limitations make it so that Cosby likely won’t ever be tried in court, even if you believe that every story has two sides, the article makes the question of whether Cosby preyed upon women seem almost crass. Without a full public confession from the star, nothing is certain, but at this point, it’d take a leap of logic to argue that public opinion should presume Cosby is innocent.

And yet the power of the article also, for me at least, breeds a sort of morbid curiosity. The kind of curiosity that makes you do that thing you should never do on the Internet when dealing with matters of rape and gender and celebrity—read the comments. Sure enough, below stories referencing the article and on social media, sprinkled amid the outpouring of sympathy for the alleged victims and disgust for their alleged attacker are the few, the proud members of Team Cosby. Or at least, Team “Forget These Women.” The team that uses phrases like “media whores.” The team that includes people saying things like “I know what I have seen of girl in the club/party scene and I am skeptical of all these stories” and that, with bizarre fervor, insults the accusers’ appearances. The team that, most commonly, says if the woman were telling the truth they would have spoken up long ago. The sentiments typically go beyond pointing out that Cosby hasn’t been convicted in court; they paint a whole group of people at immoral, reckless, opportunistic.

Yes, it’s a bad idea to use the ugliest comments and social-media statements as gauges of public opinion. Yes, by responding to trolls, you amplify them. And yes, the overwhelming response to the New York story has, rightly, been concern for the women and scorn for Cosby. Still, it bears noting: Every semi-anonymous Internet user attacking the accusers is a symbol of why Cosby may have acted with impunity for so long, and of one more thing he may have cost each of these women.

Every Internet troll attacking the accusers is a symbol of one more thing Cosby may have cost each of these women.The long Cosby saga is in large part about expectations—the belief held by many of the alleged victims that they’d be doubted and condemned if they went public. “I could have walked down any street of Manhattan at any time and said, ‘I’m being raped and drugged by Bill Cosby,’ but who the hell would have believed me?” Barbara Bowman recalls in the New York story. Another accuser, Lisa Lotte-Lubin, says her husband counseled her, “No, I don’t want anybody to know, we don’t want to expose you, I don’t want people saying bad things.”

Those expectation of backlash made the pursuit of justice into a cost/benefit calculation, with costs that went beyond career concerns: Once they spoke out, these women’s entire lives would become matters of public debate. They would become targets. They would surrender their privacy. This has, again and again, proven to be the case for victims of abuse, especially those who don’t have an opportunity to prove their claims in court—one more degradation after the original one.

Now, even as so many of Cosby’s accusers have banded together, even after seemingly incriminating admissions from the man himself have been made public, and even with evolving cultural views on rape and victims’ rights, the prophecies are being fulfilled yet again: There are people who think less of these women for telling their stories. Which, of course, is part of why it took so long for some of them to do so, and why it’s so significant now that they have.

Whose Joke Is It Anyway?

On July 25, a Twitter user noticed something strange. The site has long suffered from joke theft—usually involving spam accounts that copy and paste other user’s popular tweets in a cheap bid for attention. But it seemed like, for the first time, one comedian’s stolen jokes were being quietly deleted and replaced by a statement from Twitter referring to “a report from the copyright holder.” After years of flagrant theft, the new policy was heartening. But that the network took so long to acknowledge that a verbatim retelling of a joke by another user counted as copyright infringement points to the issue’s larger nebulousness, which has plagued comedy for decades. If the wording of two jokes aren’t exactly alike, how can you tell one was stolen?

Related Story

The Dark Psychology of Being a Good Comedian

Twitter’s crackdown on joke-stealing came at the same time that a lawsuit was filed against Conan O’Brien’s late-night show Conan by a relatively unknown comic who said the show had ripped off his material. Robert Kaseberg, who has contributed jokes to The Tonight Show, said the show had lifted four of his jokes from the Internet, pointing to very similar wording in Conan’s monologue. The jokes are undoubtedly similar, but could just as easily be a symptom of parallel thinking—after all, there are only so many easy punchlines out there for every news story. Or, as the Conan star Andy Richter quickly tweeted, “There's no possible way more than one person could have concurrently had these same species-elevating insights! THESE TAKES ARE TOO HOT!” When it comes to allegations of theft, one standard has always held in comedy: You had better be claiming ownership of some truly original material.

Late-night shows are the easiest targets of such complaints, since they’re designed to quickly react to the news with punchy one-liners, a mantle since taken up by many a Twitter user. Saturday Night Live once featured a parody of Brett Favre’s Wrangler jeans commercials after his sexting scandal; people pointed out other comedians had made the same joke online. Sure—because it was the most obvious thing to do. Aiming for the lowest common denominator doesn’t equal plagiarism. Still, complaints about theft of someone’s premise remain a frequent issue in the comedy scene. As Splitsider’s Adam Frucci once noted, if you want to accuse someone of stealing your joke, make sure it wasn’t only highly original, but also highly similar, and visible enough that someone famous might have seen or heard it.

Aiming for the lowest common denominator does not equal plagiarism.Often, allegations of joke-stealing don’t stick. A Cleveland sketch troupe complained about a bit featured on Conan in 2011, saying it was inspired by their stage act, but failed to realize the comedians performing it on the air had been doing it for years. A Saturday Night Live sketch that featured actors wearing tiny hats seemed superficially similar to a sketch that had aired a few years before on Adult Swim’s Tim & Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!, although outside of the tiny hats, their scripts had nothing in common. While it’s possible the writer had seen the Tim & Eric episode and had gotten that one particular element lodged in his or her subconscious somewhere, it’s a leap from that to outright plagiarism.

As with TV, when it comes to stand-up comedy, it can be hard to find the line between parallel thinking and insidious theft. Premise, as always, remains key. Louis C.K. famously nursed a grudge for years against Dane Cook (back in the day when Dane Cook was a far bigger audience draw in stand-up comedy) for telling jokes that had a similar core concept to his material, although the delivery was very different. Both C.K. and Cook had jokes about giving their kids a strange name, but C.K. took it in a surreal direction (he wanted to name his child “Ladies and Gentleman,” so he could spontaneously cry out “Ladies and Gentleman, please!”) compared to Cook’s more obvious approach (that it’d be weird to name your kid Optimus Prime). One similar premise might have been forgivable, but there was enough crossover to sow discord for years, until the two hashed it out face-to-face in a fascinating second-season episode of Louie.

The idea of a joke as intellectual property hasn’t always been ironclad. Many stand-up comedians used to rely on writers for their gags, reworking the material they were given to fit their style, though that practice has since fallen out of favor. Joke thievery was an issue to be worked out behind the scenes, often with threats of physical violence. David Brenner notoriously approached Robin Williams’ agent and said, “If he ever takes one more line from me, I’ll rip his leg off and shove it up his ass,” an incident reported on years later in Richard Zoglin’s book Comedy at the Edge. Williams frankly discussed his penchant (as a younger man) for joke-stealing on his fantastic appearance on Marc Maron’s podcast in 2010, where he admitted to not really understanding, at the time, the weight of what he was doing. Part of the problem is, after all, the ephemeral quality of stand-up comedy—while performances are honed to perfection, some tossed-off gags at an open-mic night might never be heard from the same comic again.

Though the subject of joke-stealing has prompted debate for decades, the Internet has recently made it easier to point fingers. In some cases that’s a good thing: Carlos Mencia’s penchant for reworking other people’s jokes was exposed online and then discussed on Maron’s podcast, where the comedian finally admitted to the practice after Maron pushed him on the issue (at the behest of many in the stand-up community). A South Park spoof of the film Inception was found to be so similar to a CollegeHumor video that the show’s writers eventually admitted to being inspired by it.

But these exceptions are notable. Even with Twitter finally acting on copyright complaints and erasing examples of word-for-word theft, there still won’t be too many cases of joke-stealing that come across as being so clear-cut. As much as it sounds like an easy excuse, two similar punchlines may just be a coincidence. When you hear about the Washington Monument being 10 inches shorter than its reported height, it’s hard not to think of a penis joke, however dumb. Not every gag can be a winner.

Is the United States Selling Out Ukraine?

If you believe all the talk out there lately, Vladimir Putin is not only duplicitous and hypocritical—the Russian president’s also been pretty damn busy recently. Busy cutting secret deals with the same Europeans and Americans he has been vilifying for years. And if you believe the rumors, the Europeans and Americans have also been busy selling out Ukraine to the Russians.

Not that any of this would be unusual or particularly surprising. Cynicism, duplicity, and hypocrisy are often the reserve currencies of politics, where interests tend to trump values.

There have long been suspicions that the United States and Europe might give Ukraine up in exchange for Russia’s support in securing a deal to curb Iran’s nuclear program. Additionally, Washington has been seeking Moscow’s backing in securing a managed, orderly, and negotiated exit for Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, which would go a long way toward ending the conflict in that country.

Related Story

And over the past two weeks, speculation has intensified that some kind of quid pro quo has in fact been reached with Putin. It began in earnest on July 14 when U.S. President Barack Obama praised Russia’s role in securing a deal to curb Iran’s nuclear program. The suspicion only increased two days later, on July 16, when U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland traveled to Ukrainian capital of Kiev to persuade lawmakers to include language in amendments to the Ukrainian Constitution recognizing the special status of separatist-held areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. This is something Russia has long sought, but that Ukraine had been resisting.

And the speculation reached a fever pitch when people began connecting the last couple months’ data points: U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry traveled to Sochi on May 12 for talks with Putin on Iran, Syria, and Ukraine; a bilateral diplomatic channel on the Ukraine conflict was subsequently opened between Nuland and Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin; Obama and Putin had two long phone conversations on June 25 and July 15. Moreover, in addition to the Iran deal, Russia also appears more open to helping broker Assad’s exit in Syria, The Wall Street Journal reported.

“A deal was cut without Ukraine, and at Ukraine’s expense,” Andrei Illarionov, a former Putin advisor turned critic, wrote on the Russian website Kasparov.ru. Likewise, political analyst Vladimir Socor wrote that “the White House has reordered its policy priorities toward working with Russia on the Middle East, correspondingly becoming more accommodating to Russia’s position on implementing the Minsk armistice in Ukraine.”

It’s tempting, it’s elegant, and it seems to fit. But is it true? Asked about a potential quid pro quo in Kiev, Nuland said it was “offensive to suggest that the U.S. does tradeoffs.” Offensive or not, it’s worth asking: What exactly has Russia gained? Two things, actually—but neither really qualifies as a wholesale sellout of Kiev.

Moscow’s endgame is to embed Russian territories back into Ukraine as a Trojan horse. And it is desperate to cut a deal to secure this result.Establishing the Nuland-Karasin diplomatic channel gives Russia something it has always craved: a bilateral format to decide the Ukraine crisis with the United States, and one that doesn’t include the Ukrainians. It’s exactly the kind of great-power politics—where big countries decide the fates of small ones—that the Kremlin loves. And with all the predictable echoes-of-Munich allusions, it is also horrible optics. But in and of itself, the Nuland-Karasin channel doesn’t really give Moscow anything deliverable.

The second thing Russia has gained came on July 16, when the Ukrainian parliament passed the first reading of constitutional amendments that would grant more power to the country’s regions. After intense lobbying from Nuland, the legislation included the line that: “The particulars of local government in certain districts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions are to be determined by a special law.”

This was widely interpreted as giving Russia what it really wants in Ukraine: a dysfunctional federalized state where its proxies in the separatist-held areas of Donbas will be able to paralyze decision-making in Kiev. The United States and the European Union have been pushing Ukraine to grant greater autonomy for Donetsk and Luhansk and the legalization of separatist forces, as stipulated by the Minsk ceasefire, before Russia and its proxies cease military operations and pull back heavy weapons.

“Western powers are increasingly pressuring Ukraine to fulfill the [Minsk agreement’s] political clauses unilaterally, without seriously expecting Russian compliance with the military clauses,” Socor wrote.

But the legislation that passed its first reading on July 16 doesn’t actually give Russia anything—at least not yet. The amendments still need to win a two-thirds majority in parliament in their final reading, far from a certainty—especially given the mood of the Ukrainian public, which is strongly opposed to granting autonomy to the rebel-held areas and legal recognition to their leaders. And even then, the separate law that will determine Donetsk and Luhansk’s status won’t be drafted and debated until the autumn.

All of which effectively leaves us pretty much where we were before: in a stalemate. Ukraine insists that Russia fulfill the military end of the Minsk deal before it fulfills the political end; and Russia insists that Ukraine deliver the political changes first.

Writing in the pro-Kremlin daily Izvestia, the Russian political commentator Aleksandr Chalenko wrote that “the Minsk process is deadlocked” and Moscow should just consider annexing the separatist-held territories. Similarly, a recent article by defense analyst Valery Afanasyev in the influential military journal Voennoye Obozreniye argued that the rebel territories should be turned into “a second Belarus … an autocratic state completely dependent on Moscow.”

This could be seen as an implicit threat to annex these territories or turn them into a protectorate. But Russia’s dirty little secret is that these are the last things it wants. Who, after all, would want to be saddled with the cost of rebuilding and the hassle of administering these places?

And Russia’s dirty little secret is no longer so secret. It’s clear to anybody paying attention that Moscow’s endgame is to embed these territories back into Ukraine as a Trojan horse. And it is desperate to cut a deal to secure this result.

“As long as Putin is in Ukraine, he is dependent on others. And this dependence can be used,” the Ukrainian political analyst Petr Oleshchuk wrote.

This post appears courtesy of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

The New York Times’ Botched Story on Hillary Clinton

I have read The New York Times since I was a teenager as the newspaper to be trusted, the paper of record, the definitive account. But the huge embarrassment over the story claiming a criminal investigation of Hillary Clinton for her emails—leading the webpage, prominent on the front page, before being corrected in the usual, cringeworthy fashion of journalists who stonewall any alleged errors and then downplay the real ones—is a direct challenge to its fundamental credibility. And the paper’s response since the initial huge error was uncovered has not been adequate or acceptable.

This is not some minor mistake. Stories, once published, take on a life of their own. If they reinforce existing views or stereotypes, they fit perfectly into Mark Twain’s observation, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.” (Or perhaps Twain never said it, in which case the ubiquity of that attribution serves to validate the point.) And a distorted and inaccurate story about a prominent political figure running for president is especially damaging and unconscionable.

Related Story

From Whitewater to Benghazi: A Clinton Scandal Primer

I give kudos to the paper for having a public editor. Margaret Sullivan’s long analysis of the multiple miscues was itself honest and straightforward. But it raised its own questions, for me at least, especially surrounding the sourcing. Here is what top editor Matt Purdy said about the story’s sources: They were “multiple, reliable, highly placed” and included some “in law enforcement.” What does that mean? First, it means that some of the sources were not in law enforcement. If they were from Congress, and, perhaps from Trey Gowdy’s special committee on Benghazi, it would not be the first time that committee has been a likely source for a front-page Times story on Clinton.

“We got it wrong because our very good sources got it wrong,” Purdy said. Excuse me—how are these “very good sources” if they mislead reporters about the fundamental facts? Were the congressional sources—no doubt “very good” because they are eagerly accessible to the reporters—careless in reading the referral documents, or deliberately misleading the reporters? We know that a very good reporter formerly with the Times, Kurt Eichenwald, read the memos from the inspectors general about the Clinton emails and quite readily came to the conclusion that this had nothing to do with a criminal referral, but instead reflected a fairly common concern regarding the recent release of particular documents under Freedom of Information Act, FOIA, long after Clinton left the State Department.

Times editor Dean Baquet does not fault his reporters; “You had the government confirming that it was a criminal referral,” he said. That raised another question. What is “the government?” Is any employee of the Justice Department considered the government? Was it an official spokesperson? A career employee? A policy-level person, such as an assistant attorney general or deputy assistant attorney general? One definitively without an ax to grind? Did the DOJ official tell the reporters it was a criminal referral involving Clinton, or a more general criminal referral? And if this was a mistake made by an official spokesperson, why not identify the official who screwed up bigtime?

This story demands more than a promise to do better the next time, and more than a shrug.When very good sources get a big story wrong, and reporters, without seeing the documents, accept their characterization of the facts and put it on the front page, they have an obligation to tell readers more about who those sources were and about why they got it wrong. And as Eichenwald notes, the subject of whether the documents were a criminal referral, and whether they involved Hillary Clinton directly, were not the only major errors in the story—for example, the Times story inaccurately says that the private Clinton email account was not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. A combination of errors on a huge, front-page story—and there is no fault on the part of the reporters? Hmmm.

This story, of course, also has a larger context. Michael Schmidt’s March story, the first on the private Clinton email server, itself had significant errors. And The Times, going back to the multiple, front page stories on Whitewater in the 1990s—claiming massive malfeasance that was seriously exaggerated—has raised many eyebrows over its decades-long treatment of the Clintons, in news pages and columns.

One might argue that this should make the paper and its editors especially sensitive to avoiding overreach and inaccuracies in stories about the Clintons. I won’t make that claim. Rather, the paper of record needs to be deeply sensitive at all times to inaccurate reporting and needs to respond with more than the usual buried corrections. The Times’ editorial page rightly holds public figures accountable for malfeasance and misfeasance. The same standards should apply to The Times. This story demands more than a promise to do better the next time, and more than a shrug, as Matt Purdy and Dean Baquet gave, with Purdy blaming the sources and Baquet saying of his reporters, “I am not sure what they could have done differently on that.”

I am. Holding a story until you are sure you have the facts—as other reporters did, with, it seems, “government officials” shopping the story around—or waiting until you can actually read the documents instead of relying on your good sources, so to speak, providing misleading and slanted details, is what they could have done differently. If reporters are hot to publish their scoops, it is up to editors, in Washington and New York, to put the brakes on. And that is especially true if reporters have previously made mistakes and overreached on stories. Someone should be held accountable here, with suspension or other action that fits the gravity of the offense. I want, and need, the old New York Times, the leader of responsible journalism, the paper of record back.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower