Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 364

August 20, 2015

The Defense of Hillary Clinton's Email Server That She Dare Not Utter

After noting untrue statements that Hillary Clinton has made about her use of a private server for government business and the presence of classified material on that server, Peter Suderman concludes that when the presidential hopeful is called to account for actions undertaken as a public official, “she responds with misleading statements, distortions, convenient excuses, and a general sense of irritation and entitlement—anything, in other words, but the clear and unambiguous truth.” He goes on to charge that she engaged in “risky, unauthorized, and decidedly non-transparent behavior.”

That’s mostly fair. Her State Department had an atrocious record of transparency that made a mockery of Freedom of Information laws, and she certainly wasn’t authorized to maintain a server in her home that contained classified information.

But was doing so risky?

Perhaps it will turn out that documents on her server compromised national security or otherwise did harm to U.S. interests. But I am not convinced.

Let’s consider another possibility. Think of it as the defense of “Servergate,” which the candidate herself wouldn’t dare make, even if she believed that parts of it were true. (Clinton’s campaign said Wednesday that emails on the server contained material that had been retroactively classified.)

But it’s fun to imagine her saying it anyway:

“America, let me come clean: Yes, there were classified documents on my email server. Yes, this was virtually inevitable when I decided to use it for official business, and set up an account for one of my top aides. But let’s not be naive about this. In Washington, the fact that something is classified doesn’t mean anything. We classify everything! It’s a way of covering our assess, leveraging control of information to make ourselves more powerful, and feeling special.

“Sure, there are some secrets that really need to be kept. And we’re relatively careful with that stuff. But when it comes to classified material, following the letter of the law would be a huge pain in the ass. And it would make government even less efficient than it is. Don’t get me wrong, the harsh laws have their uses. They allow us to punish uppity people who try to tell the citizenry the elite’s secrets. We put Chelsea Manning in a place where she gets reamed for having expired toothpaste!

“But they’re not meant for people like me—powerful people who’ve paid their dues to rise in the ruling class. Like everyone else in that cohort, I’ve earned the right to leak when I deem it prudent; to use my discretion to take whatever work I want home with me; to keep classified documents in my personal files; I mean, hell, my Teflon husband had a former crony who smuggled classified papers from a secure room.

“And what harm ever comes of it?

“Hell, I can’t prove that Wikileaks or the Snowden leaks did America more harm than good. What were the concrete harms anyway? And, to the people who say I should’ve done all my emailing through the State Department system, what a joke! As if that’s secure. LOL. We’re better off assuming that the Chinese and the Russians can see most everything we do, save the most closely guarded secrets, and even they aren’t completely safe. Anything else is just a false sense of security.

“If there’s something that we can’t afford to have leak we shouldn’t be classifying it, we should be destroying it. Our IT isn’t good enough to protect most stuff anyway.

“So get off my back about these classified documents that were on my server. If you start enforcing these laws strictly, even when powerful people are involved, you’ll wind up with a Constitutional crisis, because virtually everyone violates them and is vulnerable. It’ll be like some Third World country where political opponents maneuver one another into jail on trumped up charges so that they can grab or retain power. That should be reserved for the Snowdens of the world, not the Clintons.”

There you have it: the ultra-cynical take on classification laws as they function in the American system. By design, I cannot prove that critique is accurate. I can’t disprove it either––and that’s enough to make me wonder if it’s more trouble than it’s worth.

A Death, Protests, and Arrests in St. Louis

There has been more unrest in St. Louis—this time over the shooting by police of an 18-year-old black man who they say pointed a gun at them. Late Wednesday, police arrested nine people and used tear gas to disperse demonstrators who threw bottles and bricks at them.

Wednesday’s demonstration was one of several across the city following the police’s shooting of Mansur Ball-Bey, and it comes as the St. Louis area recovers from the unrest that surrounded the first anniversary of the killing of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old who was killed by a white officer.

At a news conference Wednesday night, Police Chief Sam Dotson said two officers, both white, were serving a search warrant Wednesday at a home in a neighborhood the St. Louis Post-Dispatch describes as “a tough block.” Two men—one of them Ball-Bey—fled the home. As they fled, Dotson said, Ball-Bey turned and pointed a gun at the officers who shot him. Ball-Bey died at the scene, he said. He said police were looking for the second suspect.

Protesters quickly took to the streets, blocking an intersection. Dotson said they threw glass bottles and bricks at them, and refused to leave. The chief said police first used inert gas to disperse the crowds, but that did not have an effect. Officers then used tear gas to clear the protesters, he said.

Nine people were arrested and they face charges of resisting arrest and impeding the flow of traffic, Dotson said.

Dotson said there were reports late Wednesday of businesses being looted and fires set. He called the incidents “acts of violence directed at not only … police officers but the neighborhood.”

Those observing the protests told local media the police response was too aggressive.

“There has to be a better way, but the better way is not to terrorize an already terrorized community,” the Rev. Renita Lamkin told the Post-Dispatch. “How they deal with the situation is classist and dehumanizing. The people here don't matter as much to them.”

A Death in St. Louis, Protests and Arrests

There has been more unrest in St. Louis—this time over the shooting by police of an 18-year-old black man who they say pointed a gun at them. Late Wednesday, police arrested nine people and used tear gas to disperse demonstrators who threw bottles and bricks at them.

Wednesday’s demonstration was one of several across the city following the police’s shooting of Mansur Ball-Bey, and it comes as the St. Louis area recovers from the unrest that surrounded the first anniversary of the killing of Michael Brown, a black 18-year-old who was killed by a white officer.

At a news conference Wednesday night, Police Chief Sam Dotson said two officers, both white, were serving a search warrant Wednesday at a home in a neighborhood the St. Louis Post-Dispatch describes as “a tough block.” Two men—one of them Ball-Bey—fled the home. As they fled, Dotson said, Ball-Bey turned and pointed a gun at the officers who shot him. Ball-Bey died at the scene, he said. He said police were looking for the second suspect.

Protesters quickly took to the streets, blocking an intersection. Dotson said they threw glass bottles and bricks at them, and refused to leave. The chief said police first used inert gas to disperse the crowds, but that did not have an effect. Officers then used tear gas to clear the protesters, he said.

Nine people were arrested and they face charges of resisting arrest and impeding the flow of traffic, Dotson said.

Dotson said there were reports late Wednesday of businesses being looted and fires set. He called the incidents “acts of violence directed at not only … police officers but the neighborhood.”

Those observing the protests told local media the police response was too aggressive.

“There has to be a better way, but the better way is not to terrorize an already terrorized community,” the Rev. Renita Lamkin told the Post-Dispatch. “How they deal with the situation is classist and dehumanizing. The people here don't matter as much to them.”

American Ultra Has the Perfect Action Hero

Why people like to watch people hurt other people is a question too big, or perhaps too distressing, to fully answer. But how people allow themselves to watch people hurt other people is a simpler one. When the fate of the world is at stake, or when righteous revenge is due, or when innocents must be protected, it becomes morally acceptable for on-screen heroes to gouge out eyes or slice throats or slam faces into brick walls. The motive itself often matters less than the fact that there’s a motive at all.

Related Story

No More Superheroes: A Fall Film Preview

With this idea in mind, American Ultra, the new action-comedy film starring Jesse Eisenberg, Kristen Stewart, Connie Britton, and Topher Grace seems less like a a throwaway in the Hollywood shelf-clearing season of late August than a profound comment on the moviegoing id. The setup: Eisenberg and Stewart play Mike and Phoebe, West Virginia stoners madly in love and aspiring to not much of anything at all. Then, one night, two menacing men appear in the parking lot of the convenience store Mike works at, and Mike kills them in seconds flat using a spoon. Turns out, he’s an unwitting supersoldier—brainwashed and then brainwiped by the CIA, sent to live in burnout anonymity until a pencil-pusher in Langley (Grace) decides he’s a liability.

As far as pretexts for orgiastic on-screen combat goes, this premise (from Chronicle writer Max Landis) is basically perfect. Mike is both an innocent everyman victimized by forces beyond his control and a totally unbeatable killing machine; he fights not for glory nor even out of an overwhelming determination to survive but simply because he must. It also doesn’t hurt as far as rooting for him goes to be repeatedly reminded that he was just about to propose to the one girl who could possibly understand his painfully neurotic, secretly artistic self. The last time there was as laboratory-pure setup for action antics, it came from Keanu Reaves’s adorable puppy in last year’s insta-cult-classic John Wick.

While that film realized its potential with fabulously arch self-seriousness, American Ultra (under the direction of Project X’s Nima Nourizadeh) is semi-slapstick like the kind seen in Marvel movies, and the result is a mix of mild thrills and middling satire. Eisenberg is as convincing an unlikely hero as he would be in real life; as with all his roles, the funniest moments come when he mutters something offhandedly that you only fully process a moment later. Unfortunately, though, his scenes alternate with those depicting the insufferable, suit-vested Grace arguing with Connie Britton’s compassionate CIA agent over whether Mike should live or die. The film’s conception of evil bureaucracy is so overdone that even the characters seem bored with it, and the scenes at headquarters (where Tony Hale is given little to do as a drone-controlling lackey) recall Men in Black without the aliens or creativity.

Mike is both an innocent everyman victimized by forces beyond his control and a totally unbeatable killing machine.Where American Ultra excels is in making use of its Rust Belt exurban setting, dotted with its shabby strip malls and drug dens. John Leguizamo gets some brief but amusing time as a loudmouthed criminal buddy of the heroic couple, whom he hides in a basement painted with a psychedelic-pornographic mural. There’s a twist midway through the film that’s telegraphed in basically every scene that precedes it, but that isn’t unwelcome for the way it complicates what had seemed like a tired gender dynamic. And the grand climax takes place in a Walmart-like superstore that allows for some truly inspired violence and ends up humanizing one of the movie’s villains to a surprising extent.

Resolution comes swiftly and predictably once Mike has been given enough time to acclimate to the revelation of his identity, and an epilogue hints that there might be some Jason Bourne-like franchise aspirations underlying the whole affair. But with its 90-minute runtime delivering chuckles and hoots without true suspense, it’s hard to imagine there being much demand for a follow-up. The whole appeal of American Ultra lies in the fact that the protagonist had forgotten he was special. The irony is that after the lights go up, everyone else is going to forget, too.

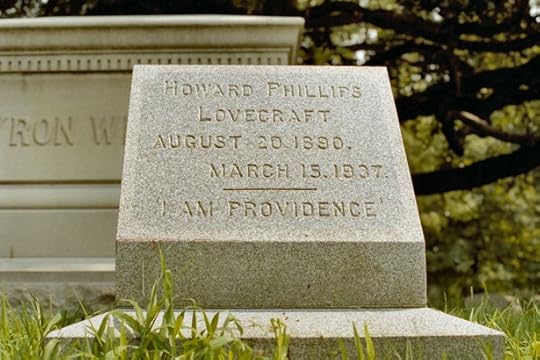

The Unlikely Reanimation of H.P. Lovecraft

American history is filled with writers whose genius was underappreciated—or altogether ignored—in their lifetime. Most of Emily Dickinson’s poems weren’t discovered and published until after her death. F. Scott Fitzgerald “died believing himself a failure.” Zora Neale Hurston was buried in an unmarked grave. John Kennedy Toole won the Pulitzer Prize 12 years after committing suicide.

Related Story

The 'Product of Its Time' Defense: No Excuse for Sexism and Racism

But no tale of posthumous success is quite as spectacular as that of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the “cosmic horror” writer who died in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1937 at the age of 46. The circumstances of Lovecraft’s final years were as bleak as anyone’s. He ate expired canned food and wrote to a friend, “I was never closer to the bread-line.” He never saw his stories collectively published in book form, and, before succumbing to intestinal cancer, he wrote, “I have no illusions concerning the precarious status of my tales, and do not expect to become a serious competitor of my favorite weird authors.” Among the last words the author uttered were, “Sometimes the pain is unbearable.” His obituary in the Providence Evening Bulletin was “full of errors large and small,” according to his biographer.

Nowadays, it’s hard to imagine Lovecraft faced such poverty and obscurity, when

August 19, 2015

Why Flibanserin Is Not the ‘Female Viagra’

After three applications, ownership by two drug companies, and one successful lobbying campaign, the female sexual-dysfunction drug flibanserin was approved yesterday by the Food and Drug Administration.

Flibanserin, which will be sold under the brand name Addyi, has been billed as a remedy for women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder, defined as “persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity” in either gender.

It’s also been rejected twice, for concerns that lingered even after an FDA advisory committee voted 18-6 in June to recommend approval. The drug has an effectiveness rate of somewhere between 8 and 13 percent, and can cause side effects like fainting, dizziness, and low blood pressure, many of which were found to be exacerbated by alcohol and hormonal contraception. When it comes to market in October, Addyi’s label will carry a warning that it can’t be taken with alcohol. (And in the alcohol-safety study submitted to the FDA, oddly, 23 of the 25 participants were men, meaning the effects of drinking while on the drug still aren’t fully understood for the women who will be taking it.)

Even so, it’s been hailed by supporters as a step towards gender equality in a previously overlooked area. “The FDA has approved 26 drugs marketed for the treatment of male sexual dysfunctions, compared to zero [now one] to address the most common form of female sexual dysfunction,” reads the website for Even the Score, a coalition of non-profits and health-care companies—including Sprout Pharmaceuticals, which makes flibanserin—that formed in 2013 to lobby for the drug’s approval.

None of those 26 drugs, though, has the same purpose as flibanserin. Viagra and its ilk enhance physical arousal; despite its nickname as the “pink Viagra,” flibanserin was developed to enhance desire. Viagra is taken before sex and increases blood flow to the genitals; flibanserin is supposed to be taken daily and aims further north, changing the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain.

Related Story

Do Women Need Their Own Viagra?

The comparisons to Viagra, and the bumpy road to approval, have raised complicated questions about the nature of female desire, sexism in drug research, and what ought to qualify as a disorder.

The drug’s approval has also raised a simpler question: What changed, exactly, between those two rejections and last night?

The most obvious answer is good public relations. Even the Score, which launched in 2013, has framed the issue as one of “women’s sexual health equity.” The group notes on its site that the World Health Organization considers “[pursuit of] a satisfying, safe and pleasurable sexual life” to be a human right, and has successfully solicited letters of support to the FDA from the editor of The Journal of Sexual Medicine, the president of the National Organization for Women, and members of Congress.

In an June editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, three members of the FDA’s June advisory committee wrote of Even the Score: “Although flibanserin is not the first product to be supported by a consumer advocacy group [that is] in turn supported by pharmaceutical manufacturers, claims of gender bias regarding the FDA’s regulation have been particularly noteworthy, as have the extent of advocacy efforts.”

But there’s another answer, too: Between the two rejections and the approval, the benchmark for success has changed.

A highlights-only timeline of the drug’s rocky history looks like this: Flibanserin was originally developed as an antidepressant. After initial trials found it to be ineffective, it was redirected as a remedy for low female desire. The pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim submitted the drug for approval in 2010, though the agency rejected the application, noting that it didn’t seem to work very well for its new purpose, either. Sprout acquired the drug in 2011 and saw another rejection in 2013; this time, the FDA asked for additional safety studies and called for an advisory committee to investigate whether the risks outweighed the modest benefits.

People were having more sex—more good sex, even—but flibanserin wasn’t making people want sex more in the first place.Boehringer Ingelheim’s first two trials, submitted as part of the application the FDA rejected in 2010, had asked participants to keep a daily digital diary, reporting both the number of “satisfying sexual events” and the highest level of sexual desire they experienced each day. These measures were the study’s primary endpoints, or the main questions a drug trial is designed to answer. Of the two, only the number of satisfying sexual experiences slightly increased with the use of flibanserin; the pill failed to make any meaningful difference on self-reported levels of desire.

Put another way, people were having more sex—more good sex, even—but flibanserin wasn’t doing what it was supposed to do: make people want sex more in the first place.

But in a move that would later become key to flibanserin’s approval, the studies also had a secondary endpoint: how the women scored on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a tool that assigns respondents a sexual-function score based on their sexual activity over the month leading up to the survey. Unlike the digital diaries, the FSFI asked participants to recall desire from the past four weeks, rather than the past day. Also unlike with the digital diaries, this measure showed a difference between flibanserin and placebos.

When Sprout took over the development of flibanserin from BI in 2011, it conducted one more efficacy study of its own, but reshuffled the criteria. The new trial kept the number of satisfying sexual experiences as one primary endpoint, but this time around, participants weren’t asked to record their daily levels of desire; instead, the study used the FSFI—which had previously shown favorable results—as its other main measure.

Meanwhile, outside of the FDA, Sprout, and Even the Score, a third thing has changed: Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD), the condition that flibanserin was developed to treat, is no longer listed by the American Psychiatric Association as its own disorder.

At the time that Spout acquired flibanersin, the most recent edition of the DSM was the DSM-IV, which drew a distinction between problems with female desire and problems with arousal. HSDD was its own entry; separately, Female Sexual Arousal Disorder was defined as “persistent or recurrent inability to attain, or to maintain until completion of the sexual activity, an adequate lubrication swelling response of sexual excitement.”

But in the DSM-V, published in 2013, the two were combined into one condition, “Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder.”

“Research suggests that sexual response is not always a linear, uniform process,” the APA wrote in an explanation of the changes, “and that the distinction between certain phases (e.g., desire and arousal) may be artificial”— a change that complicates the already-complicated arguments for and against the little pink pill.

Why Flibanserin Is Not the 'Female Viagra'

After three applications, ownership by two drug companies, and one successful lobbying campaign, the female sexual-dysfunction drug flibanserin was approved yesterday by the Food and Drug Administration.

Flibanserin, which will be sold under the brand name Addyi, has been billed as a remedy for women with Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder, defined as “persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity” in either gender.

It’s also been rejected twice, for concerns that lingered even after an FDA advisory committee voted 18-6 in June to recommend approval. The drug has an effectiveness rate of somewhere between 8 and 13 percent, and can cause side effects like fainting, dizziness, and low blood pressure, many of which were found to be exacerbated by alcohol and hormonal contraception. When it comes to market in October, Addyi’s label will carry a warning that it can’t be taken with alcohol. (And in the alcohol-safety study submitted to the FDA, oddly, 23 of the 25 participants were men, meaning the effects of drinking while on the drug still aren’t fully understood for the women who will be taking it.)

Even so, it’s been hailed by supporters as a step towards gender equality in a previously overlooked area. “The FDA has approved 26 drugs marketed for the treatment of male sexual dysfunctions, compared to zero [now one] to address the most common form of female sexual dysfunction,” reads the website for Even the Score, a coalition of non-profits and healthcare companies—including Sprout Pharmaceuticals, which makes flibanserin—that formed in 2013 to lobby for the drug’s approval.

None of those 26 drugs, though, has the same purpose as flibanserin. Viagra and its ilk enhance physical arousal; despite its nickname as the “pink Viagra,” flibanserin was developed to enhance desire. Viagra is taken before sex and increases blood flow to the genitals; flibanserin is supposed to be taken daily and aims further north, changing the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain.

Related Story

Do Women Need Their Own Viagra?

The comparisons to Viagra, and the bumpy road to approval, have raised complicated questions about the nature of female desire, sexism in drug research, and what ought to qualify as a disorder.

The drug’s approval has also raised a simpler question: What changed, exactly, between those two rejections and last night?

The most obvious answer is good public relations. Even the Score, which launched in 2013, has framed the issue as one of “women’s sexual health equity.” The group notes on its site that the World Health Organization considers “[pursuit of] a satisfying, safe and pleasurable sexual life” to be a human right, and has successfully solicited letters of support to the FDA from the editor of The Journal of Sexual Medicine, the president of the National Organization for Women, and members of Congress.

In an June editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, three members of the FDA’s June advisory committee wrote of Even the Score: “Although flibanserin is not the first product to be supported by a consumer advocacy group [that is] in turn supported by pharmaceutical manufacturers, claims of gender bias regarding the FDA’s regulation have been particularly noteworthy, as have the extent of advocacy efforts.”

But there’s another answer, too: Between the two rejections and the approval, the benchmark for success has changed.

A highlights-only timeline of the drug’s rocky history looks like this: Flibanserin was originally developed as an antidepressant. After initial trials found it to be ineffective, it was redirected as a remedy for low female desire. The pharmaceutical company Boehringer Ingelheim submitted the drug for approval in 2010, though the agency rejected the application, noting that it didn’t seem to work very well for its new purpose, either. Sprout acquired the drug in 2011 and saw another rejection in 2013; this time, the FDA asked for additional safety studies and called for an advisory committee to investigate whether the risks outweighed the modest benefits.

People were having more sex—more good sex, even—but flibanserin wasn’t making people want sex more in the first place.Boehringer Ingelheim’s first two trials, submitted as part of the application the FDA rejected in 2010, had asked participants to keep a daily digital diary, reporting both the number of “satisfying sexual events” and the highest level of sexual desire they experienced each day. These measures were the study’s primary endpoints, or the main questions a drug trial is designed to answer. Of the two, only the number of satisfying sexual experiences slightly increased with the use of flibanserin; the pill failed to make any meaningful difference on self-reported levels of desire.

Put another way, people were having more sex—more good sex, even—but flibanserin wasn’t doing what it was supposed to do: make people want sex more in the first place.

But in a move that would later become key to flibanserin’s approval, the studies also had a secondary endpoint: how the women scored on the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a tool that assigns respondents a sexual-function score based on their sexual activity over the month leading up to the survey. Unlike the digital diaries, the FSFI asked participants to recall desire from the past four weeks, rather than the past day. Also unlike with the digital diaries, this measure showed a difference between flibanserin and placebos.

When Sprout took over the development of flibanserin from BI in 2011, it conducted one more efficacy study of its own, but reshuffled the criteria. The new trial kept the number of satisfying sexual experiences as one primary endpoint, but this time around, participants weren’t asked to record their daily levels of desire; instead, the study used the FSFI—which had previously shown favorable results—as its other main measure.

Meanwhile, outside of the FDA, Sprout, and Even the Score, a third thing has changed: Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder (HSDD), the condition that flibanserin was developed to treat, is no longer listed by the American Psychiatric Association as its own disorder.

At the time that Spout acquired flibanersin, the most recent edition of the DSM was the DSM-IV, which drew a distinction between problems with female desire and problems with arousal. HSDD was its own entry; separately, Female Sexual Arousal Disorder was defined as “persistent or recurrent inability to attain, or to maintain until completion of the sexual activity, an adequate lubrication swelling response of sexual excitement.”

But in the DSM-V, published in 2013, the two were combined into one condition, “Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder.”

“Research suggests that sexual response is not always a linear, uniform process,” the APA wrote in an explanation of the changes, “and that the distinction between certain phases (e.g., desire and arousal) may be artificial”— a change that complicates the already-complicated arguments for and against the little pink pill.

U.S. Consumer Prices Rise in July

Updated on August 19 at 2:21 p.m. ET

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today that consumer prices rose 0.1 percent in July. This is the sixth straight month that the consumer price index (CPI) has increased, with July’s gains slightly down from a 0.3 percent gain in June and 0.4 percent in May.

The main contributor to July’s increase was a 0.4 percent increase in the cost of shelter—the government’s measure of housing costs, which looks at rent. The indexes for food, energy, and medical care also rose. The index for airline fare experienced the largest decline since 1995.

The July CPI results indicate only a modest rise in prices, but economists don’t expect that modesty to deter the Federal Reserve from raising interest rates in September. (Typically interest rates are raised in order to temper rising prices.) In a Wall Street Journal poll earlier this month, 82 percent of economists believe that a rate hike in short-term interest rates is set for next month. A minority believe that the July CPI numbers are a red light, and that the rate hike will be delayed to December.

Janet Yellen, chief of the Federal Reserve, has repeatedly hinted that interest rates will be raised at some point this year, keeping markets on edge. The Fed has not raised interest rates in nearly a decade.

While the U.S. job market has been putting in solid numbers, the counter-argument against raising rates is that inflation is still very low. Critics have have called the Fed too eager to normalize—removing the policy that’s been in place since 2007 and keeping rates artificially low in the name of economic recovery.

Today, U.S. investors got mixed messages from the Federal Reserve’s July meeting minutes. Markets fell this morning ahead of the release, on speculation that the report would solidify September rate-hike worries. This afternoon, U.S. indexes recovered some losses as some investors bet on Fed members expressing that the economic conditions to necessitate a rate hike still haven’t been achieved—though the language hints that it’s coming.

“During their discussion of economic conditions and monetary policy, participants mentioned a number of considerations associated with the timing and pace of policy normalization. Most judged that the conditions for policy firming had not yet been achieved, but they noted that conditions were approaching that point,” the Fed’s Open Market Committee wrote.

That leaves the door open for a September rate hike. If August’s employment numbers are strong, it will increase the chances that Fed members will vote that way.

The Books That Prison Officials Don’t Want Chelsea Manning to Read

Last month, prison officials discovered contraband in Chelsea Manning’s cell: books and magazines considered to be “prohibited reading material.” Her potential punishment? Solitary confinement.

On Tuesday night, Manning, the U.S. soldier convicted in 2013 of giving classified government information to WikiLeaks, tweeted the punishment a prison board handed her for possessing the items: “21 days of restrictions on recreation” which means “no gym, library, or outdoors.”

Related Story

The Persecution of Chelsea Manning

Manning, who previously was known as Bradley Manning, identifies as a woman. She is serving a 35-year sentence at an all-male, maximum-security military prison in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Officials confiscated 22 books and magazines, which included a novel about transgender women, the Caitlyn Jenner issue of Vanity Fair magazine, Malala Yousafzai’s memoir, and the Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture.

Here’s the full inventory, according to Manning:

This is the official inventory of confiscated books and magazines. pic.twitter.com/MvlaU2UmbL

— Chelsea Manning (@xychelsea) August 14, 2015

None of these, Manning’s lawyer argued last week, constitute “a national security issue.” The issue of security, however, is often used to determine approved and prohibited reading material in federal and state prisons across the country. Federal Bureau of Prisons regulations state publications can be confiscated and banned if they are found “to be detrimental to the security, good order, or discipline of the institution or if it might facilitate criminal activity." Prisons can’t reject a publication “solely because its content is religious, philosophical, political, social, sexual, or...unpopular or repugnant.”

But determining which books are considered safe and which are dangerous is, as you might expect, highly subjective. And not every prison in America interprets federal guidelines in the same way. As Andrew Losowsky reported in The Huffington Post in 2011:

… many correctional institutions censor materials far beyond these guidelines. Central Mississippi Correctional, for example, is stated as refusing to allow any books whose content includes anything legal, medical or contains violence, while Staunton Correctional in Virginia is claimed only to allow its inmates access to "non-fiction educational or spiritual books."

There are plenty more examples. Losowsky points to a 2011 report by the Texas Civil Rights Project, which called the state prison system’s censorship of some authors— including Shakespeare, Sojourner Truth, George Orwell, and Jon Stewart—“arbitrary” and “bizarre.” One correctional facility in South Carolina denied access to most books and magazines for several years until the American Civil Liberties Union sued it and won in 2012. In 2013, National Journal’s Matt Berman reported the Connecticut Bureau of Corrections had banned the July 22, 2013, issue of The New Yorker, which included a story on domestic abuse, and the September copy of Slam Magazine, with LeBron James on the cover, citing "safety and security” reasons. The bureau did add some books to its approved list: George R.R. Martin’s popular novels, but not the first one in the series, A Game of Thrones.

The Leavenworth facility where Manning is serving her sentence could not be reached for comment about its list of approved and prohibited reading material. According to the prison’s inmate information handbook, inmates “have the right to a wide range of reading materials...for educational purposes and your own enjoyment,” which “may include magazines and newspapers sent from the community, with certain restrictions.”

Why ISIS Killed an Antiquities Scholar

For a half-century, Khaled Asaad devoted his life to the antiquities of Palmyra, a UNESCO Heritage site located northeast of the Syrian capital, Damascus. A scholar of Aramaic, Asaad wrote extensively about pre-Islamic life in Syria and was a fixture of international archaeological conferences. But the ruins he worked among could not preserve his life. On Tuesday, militants from the Islamic State beheaded Asaad in a Palmyra town square after he refused to divulge the location of artifacts coveted by the group. ISIS then hung the 82-year-old’s corpse from a Roman column.

Gruesome executions are an integral aspect of the Islamic State’s ruling style, but this killing illustrates the crucial role antiquities play in ISIS’s day-to-day governance. Part of this is symbolic: Muslim fundamentalist groups have long had a contentious relationship with cultural artifacts, particularly those that predate the rise of Islam in the 7th century A.D.

The ruins of Palmyra are a valuable economic commodity.After it captured Palmyra in May, ISIS sought to quell fears it would destroy the ancient city, saying it would spare the ruins and monuments. But, a commander for the group said, “we will … pulverize statues that the miscreants used to pray [to].” The group was true to its words, sparking international outrage by releasing videos displaying destruction of ancient Islamic shrines.

But the ruins of Palmyra are a valuable economic commodity. Syria’s archaeological treasures fetch high prices in the international black market and are a crucial revenue stream for ISIS. In this, the group is continuing a process that began long before its inception: Illicit trade in antiquities existed in Syria even before the 2011 civil war uprooted centralized control. In July, BuzzFeed profiled a Syrian trader who smuggled ancient goods across the country’s porous border to Turkey, where items such as statues can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

According to the Financial Times, ISIS’s trade in archaeological goods has risen because other revenue streams—such as oil—have become less practical. In that context, the group’s announcement it would preserve Palmyra makes more sense.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower