Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 360

August 25, 2015

Crass Frat Boys at Old Dominion

At Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, someone at an off-campus fraternity house hung crass, homemade banners from the balcony for incoming freshmen to see while being dropped off by their parents. One banner said, “Rowdy and Fun, Hope Your Baby Girl Is Ready for a Good Time.” Another said “Freshman Daughter Drop Off” and featured an arrow pointing to the front door of the house. A third sign said, “Go Ahead and Drop Off Mom Too.”

The banners were crude and distasteful. Even at 18, I wouldn’t have hung them. If I were a professor there, I’d have told the kids that they have a First Amendment right to display the signs even as I tried to shame them into taking them down. If my kid put up those banners––not that I’d ever pay for a kid to live in a frat house––I’d tell him to take them down or never ask for my help with tuition again.

Even so, it staggers me that this is an international news story covered by scores of outlets. How did we reach a place where Local Frat Makes Crude Joke causes staffers at the BBC, CNN, The Washington Post and USA Today to spring into action?

The answer begins with one interpretation of the banners. For some observers, they aren’t just vulgar, rude, suggestive, bawdy, ribald, derogatory, or uncouth––they’re an example of “rape culture.” As Old Dominion’s President John Broderick put it, “While we constantly educate students, faculty and staff about sexual assault and sexual harassment, this incident confirms our collective efforts are still failing to register with some.” Nearly every press outlet that has covered the controversy connected it to ongoing efforts to reduce the number of rapes that occur on campus.

One Old Dominion student told Jezebel, “I feel very strongly about how the attitude towards sexual assault on campuses is met with a slap on the wrist … As a woman, it’s frustrating to see the media bring awareness to the issue and then witness something related in your own community/school and see that nothing is changing.”

To other observers, those reactions make little sense.

As they see it, a college’s sexual-assault problem is best gauged by the number of sexual assaults. They regard the banners as an obvious joke. And they insist that the humor is rooted in confronting parents, who like to guard the virginity of their daughters, with the trope that they go off to college and have sex with frat guys. In this telling, nothing about the trope implies a non-consensual encounter. And regardless of the joke’s meaning, they believe it irrational to operate as if a sophomoric prank that seems like something a couple 19-year-olds cooked up in a few hours reveals their attitudes toward rape; the likelihood that they would rape someone; campus attitudes toward rape; or the success of campus anti-rape efforts.

“I’m usually in the position of defending extremely offensive speech on the grounds that it is protected by the First Amendment,” Robby Soave wrote at Reason. “In this case, I struggle to grasp what was even so monstrous about the banners. Hope your baby is ready for a good time, oh, mom too! is certainly crude and in bad taste. But no specific person is being maligned, threatened, or disparaged. And some frat brothers are eager to have sex with girls—is this surprising?”

He added that, “associating the banners with sexual assault, as Broderick did, is a considerable exaggeration. Sigma Nu members certainly didn’t threaten anyone with sexual assault; putting up some mildly suggestive signs does not constitute an act of violence. The banners don’t even clear the sexual-harassment bar. They aren’t severe, pervasive, objectively offensive, or directed at anyone in particular.”

Where do I come down? It’s lamentable that some women arrived on their college campus only to be greeted by signs treating them as sexual objects. These immature 19-year-olds displayed bad judgment, but so do the adults who are reacting as if they were stockpiling GHB. Pop culture is filled with material far more vulgar and offensive, including content that actually does transgress against the value placed on consent.

Debates like this are polarizing because a false choice is often presented: defend the transgression that is generating outrage or join in condemning the perpetrators. But there is a third way. It requires circumspection and a sense of proportion.

The banners do deserve criticism.

Sigma Nu, the national fraternity, is within its rights to complain about the way this chapter is representing it; on Monday, it suspended the chapter pending the outcome of an investigation.

Should someone at Old Dominion explain to those kids the offensive assumptions implicit in their signs? Yes. Did they do something so awful that it warrants overnight CNN alerts, a BBC headline, and a university investigation into what happened?

No. Of course not.

Should the university president have made a statement? Sure. He could have said, “I've been getting inquiries about crude signs hung by some of our students from their off-campus house, as is their right under the First Amendment. I encourage those students to exercise their rights more thoughtfully in the future, to treat women respectfully, and to take this opportunity to learn from a youthful mistake. We’ve all made them. And I hope members of the media will recall instances when they showed poor judgment at 18, 19, or 20, as they cover this story.”

Instead he showed no sense of proportion.

In a nation where the First Amendment guarantees the rights of Nazis to march through the streets of a Jewish community, the president of a public university declared of clearly protected speech: “Messages like the ones displayed yesterday by a few students on the balcony of their private residence are not and will not be tolerated.”

And he asserted that one or two undergrads with bed sheets and black markers “undermine the countless efforts at Old Dominion University to prevent sexual assault.” If that isn’t hyperbole, he should try a different approach to preventing sexual assault.

Meanwhile, Sharon Grigsby writes in The Dallas Morning News that if you think the frat’s banners were an obvious joke, as many students at the college reportedly concluded, “You’ve got to be kidding. Anyone who believes that is part of the problem.” In fact, believing that they made a tasteless joke rather than an apology for rape culture does not make someone “part of the problem” of sexual assault.

Ultimately, this story lays bare a divide.

It is not a divide between people who care about reducing the rate of sexual assault and those who don’t; rather, the divide concerns how best to achieve that common goal. Insofar as I can tell, one theory holds that what’s best, in this case, is to hold up whoever made those banners as possible-rapist pariahs; to pursue disciplinary charges against them; to suspend their frat; and to condemn them as if they’ve consigned more women to rape by undermining their college’s efforts to prevent it.

I have a different view.

It would be convenient for Old Dominion if harshly denouncing and punishing these boys would be taken as the prime measure of how seriously the school takes sexual assault.

It’s easy to grandstand against frat boys with crass signs.

But reducing sexual assaults requires sounder metrics of success. Controversies like this are a distraction; they distract from what’s really required to make college campuses safer for women; and they alienate a portion of the public that tires of exaggerated outrage.

Focusing on the core problem of rape (rather than seizing on offensive comments from obscure undergrads as if they bear meaningful responsibility for that problem) also makes it easier to avoid getting trolled by provocateur 19-year-olds. Words they thoughtlessly scrawl on bed sheets do not belong at the center of our discourse.

New Orleans Is Still Not Prepared for the Next Storm

NEW ORLEANS—The question of what it will take to prevent the next Katrina or Sandy has a pretty straightforward answer: money.

Of course that leaves a lot to be sorted out: Where should the money come from? How should it be spent? But the overarching need to invest in improving infrastructure was a plea made by several panelists during the “New Orleans: 10 Years Later,” hosted on Monday by The Atlantic.

Even a decade after New Orleans’s levees were breached, some say that the improvements made by the Army Corps of Engineers—which have included raising, rebuilding, and reinforcing levee walls, and updating predictive models to reflect the possibility of more severe storms—are still simply not enough to ensure the safety of the city or its residents in the longterm.

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New Orleans

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New OrleansRead More

That’s because, even in the wake of Katrina, people do not want to raise taxes to fund the necessary improvements. “Levees require reinvestment. It’s not a free system,” says David Waggonner, the president of Waggonner and Ball Architects, which is based in New Orleans. He noted that St. Bernard Parish—which borders New Orleans and had 100 percent of its housing stock damaged or destroyed during Katrina—has twice voted against the implementation of a levee tax, which would support the maintenance of the structures meant to protect residents from the very same floodwaters in the future.

Even with the added capability of higher, stronger levees, there are no guarantees. As Karen Durham-Aguilera, the director of Task Force Hope in New Orleans, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stressed, “It’s really a question of how much you want to invest to reduce risk.”

That’s why structural solutions, like the levees and more advanced pumping systems, should never encompass the entirety of a city’s disaster plans, and why evacuation protocols are critical. “The system is meant to protect our property, not our lives,” said Mark Schleifstein, an environment reporter at The Times-Picayune. He noted at the event that, statistically, the evacuation that preceded Katrina was by all counts successful—with a large segment of the population actually leaving the city. But many who didn’t have access to transportation, couldn’t travel, or didn’t have money for housing if they did manage to escape, were left behind. Part of preventing another tragedy, he said, requires figuring out how to help the most vulnerable leave safely, should another big storm come. This project was made possible with support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

What Is It With Donald Trump?

Leader. Decisive. Successful. Brave. Committed. True American.

That’s how voters described Donald Trump in a focus group moderated by Frank Luntz on Monday night. Twenty-nine men and women from the Washington, D.C., region, out of 33 invited, participated in the session—offering impassioned critiques of the GOP establishment.

The sample of supporters included Democrats, Independents, and Republicans: Most were all in for Trump.

Why? “He’s voiced what everyone else is saying,” one male participant said, “America is a brand and the brand has been hurting a very long time, and it takes somebody like Trump to bring that brand back.”

Related Story

What Do Donald Trump Voters Actually Want?

That Trump is competing in a crowded GOP field doesn’t seem to faze his supporters. Since his June announcement, Trump has positioned himself as the Republican frontrunner. And last week, a CNN/ ORC poll also found that he’s closing the gap with Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton.

But his surge in the polls hasn’t come quietly. The presidential hopeful has come to be known for calling Mexican immigrants rapists, saying that John McCain is not a war hero, and attacking Megyn Kelly following the first GOP debate. And, while his comments have stirred controversy, they are also generating traction among voters, according to the focus group. Many found his flamboyant style entertaining. Participants reported positive feelings after being shown clips of Trump criticizing Rosie O’Donnell at the first debate, and flaunting his wealth.

“He’s not a politician. I won’t vote for an established politician.”The panelists ranked Trump’s promise to repeal Obamacare and “restore the balance between U.S. trading partners” highest among his various stands on the issues. Some respondents, including a woman from Mexico, pointed to Trump’s visit to the U.S.-Mexico border as the moment they decided to support him.

But Trump’s biggest selling point isn’t what he’s done—it’s what he hasn’t. A majority of respondents are simply happy that he’s not a politician, based on their negative views of members of Congress.

According to a recent Pew Research survey, 27 percent of Republicans have an unfavorable opinion of their party, up from 12 percent since January. Participants at the voter session on Monday reflected that fact.

When voters were asked to describe Congress in one word during the session on Monday, the most commonly used word was “useless.”Many voiced their dissatisfaction with Congress, particularly its Republican members. When voters were asked to describe Congress in one word during the session on Monday, the most commonly used word was “useless.”

The party has been struggling to deliver on its promises to voters during the midterm elections. Uphill battles continued to appear this year as lawmakers tackled the renewal of some provisions of the Patriot Act, funding for Planned Parenthood, and, soon, the Iran deal.

Rivalries have also surfaced within the party. Ted Cruz called out Mitch McConnell on the Senate floor, saying he was a liar after the Senate majority leader allowed a a vote of the Export-Import bank. Cruz later conceded that he wasn’t attacking McConnell “personally.”

Trump has threatened not to support a Republican candidate if he isn’t the nominee, holding open the option of running as an independent. For some voters in the session, that wasn’t a problem. Only six of the 29 admitted they were bothered by it, but the rest were not. In fact, for many, Trump’s lack of partisan loyalty only enhanced his appeal. “He’s not a politician. I won’t vote for an established politician,” one man said.

Some in the group had initially backed Trump, but have since stepped back from that support. They were especially hesitant about his lack of specific policy proposals, and voiced their doubts about some of the details he had offered. There was also general concern about Trump’s comments on McCain. Veterans in the group took issue with his words, though many still said they'd support him.

While a majority supported Trump, not all are absolutely committed to voting for him. Only nine definitively pledged their support. Other possible choices among the group were Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush, Ben Carson, Marco Rubio, and Carly Fiorina. Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders, and Scott Walker were also mentioned.

As Luntz said to reporters: “Beating [Trump] is still possible.”

There’s no denying, however, that his supporters are excited about him. Perhaps the sudden momentum is a product of Trump’s consistent appearances on television shows and unconventional approach. Or maybe it’s a result of his policies and business stature. Whatever the case may be, there seems no denying that he’s “entertaining,” as one voter put it.

August 24, 2015

A Roller-Coaster Day on Wall Street

Updated on August 24 at 4:15 p.m. ET

U.S. stocks had a roller-coaster day Monday, with the Dow falling more than 1,000 points at the opening bell before recovering at noon when it was 150 points down, and then fading again in the afternoon to close down 585 points, or about 3.4 percent.

The broader S&P 500, which also had partially recovered in the afternoon, closed in correction. It was 3.9 percent down at 4 p.m.—11 percent below the record it set in May. The Nasdaq Composite fell 3.8 percent.

Although the declines were large, they were by no means even close to the largest percentage decline in Wall Street history. On October 19, 1987—now famous as Black Monday—the Dow fell more than 22 percent.

At the heart of Monday’s massive selloff was growing unease about the state of China’s economy. Markets were hammered in Europe and Asia. In China, the benchmark Shanghai composite index erased its gains for the year.

Ryan Larson, head of U.S. equity trading for RBC Global Asset Management, attributed the selloff to “herd mentality.”

“But once that herd gets out of the way, there can be some very good buying opportunities,” he told The Wall Street Journal.

Larson told the newspaper the Dow’s relative recovery—it cut its earlier losses by nearly half—showed investors that the initial drop was an overreaction.

Monday’s opening on Wall Street followed last week’s steep decline in markets—the worst in four years. The Journal adds:

Investors were further rattled Monday by the lack of fresh steps to stem the selloff over the weekend from Chinese authorities. The Wall Street Journal reported that the central bank was preparing to flood the banking system with liquidity to increase lending, the latest in a series of measures designed to give the flagging economy a boost.

In China on Monday, the Shanghai composite index tumbled 8.5 percent, entering negative territory for the year. Stocks across Europe closed down 5 percent, despite paring some of the day’s earlier losses.

The source of the woes is China’s economy. One sign, as my colleague Bourree Lam noted last week, is that factory output is at a six-year low. The country’s central bank tried to intervene two weeks ago, devaluing the yuan. But that seems to have had little effect. Chinese stocks, which in May hit seven-year highs, have wiped out all their gains.

Oil prices continued their decline Monday, with Brent crude—the global benchmark—below $45 per barrel for the first time since March 2009. Global currencies, especially those of emerging markets, also fell.

Should Jeb Bush Go After Trump?

To be a candidate for high office is to be surrounded by a cacophony of advice. So long as things are going well, most of the advice can be politely disregarded. President George W. Bush used to explain why he disliked traveling with a large entourage: “How many people do I need telling me to be myself?” But when things go south, the advice becomes more insistent, more contradictory, and more dangerous.

Right now, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush seems to be getting advised that he should take the gloves off with Donald Trump. (If “be yourself” is the advice a candidate hears most often when the news is good, “take the gloves off” is the most frequent counterpoint when news turns bad.)

Related Story

Can the Republican Party Survive Trump?

In New Hampshire this week, Bush criticized Trump more openly than at any point since Trump rose into first place in the polls. Bush attacked Trump as a pseudo-Republican, a supporter of partial-birth abortion and single-payer health care, and an inconsistent and unreliable purveyor of vitriol whose immigration enforcement ideas would cost hundreds of billions of dollars. NPR quoted a Republican observer’s explanation of the new tactic: “What Jeb is desperately trying to do is find his swagger right now. The knock against Jeb is that he’s low voltage and not willing to fight. The best way to shake those perceptions i[s] to engage against the person who is in the media on a 24/7 loop.”

Jeb Bush may feel he has no choice. Donors have invested tens of millions of dollars in his campaign, and many of them must, by now, be getting uneasy. If the uneasiness intensifies, the flow of checks will slow. Every campaign runs on money, but Jeb Bush’s more than most. He’s hoping through sheer staying power to impose his nomination on a recalcitrant party. The money buys the staying power. If the money dwindles, his fortunes fall hostage to the Republicans of the early states: Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada, none of them a promising Jeb Bush firewall.

So the attack-Trump mistake may be unavoidable, a necessary error to avert the even-worse calamity of having his fundraisers go on strike. Yet attack-Trump remains an error all the same for Jeb Bush—and for two big reasons.

First, Trump certainly hurts Bush, but he hurts other candidates more. Bush’s most immediate problem is not that the base doesn’t trust him—it didn’t trust John McCain either, yet he nevertheless won the nomination—but that his donors enjoy too many plausible alternative choices. Bush needs to hustle the donor-acceptable alternatives out of the race as fast as possible, as Mitt Romney was able to do in 2012, leaving donors with a stark alternative: me or some sure-loser madman. Once the donors are locked up and locked down, the party base will sooner or later have to submit. In 2012, as Bachman, Herman Cain, and Newt Gingrich exploded on the tarmac, base voters swung to support Romney.

Bush’s trouble is that he doesn’t have the clout to push the other donor-acceptable alternatives out of the race. Real-world politicians quit when they see they can’t win, and except for Rick Perry and George Pataki, none of the donor-acceptable alternatives will look at today’s polls and think, “I can’t win.” So Carly Fiorina and John Kasich and Marco Rubio and Scott Walker will linger in the race, subdividing the big money and waiting to pounce on any Jeb Bush misstep or defeat. Bobby Jindal will hang on too—what has he got to lose?

Show Trump a line, and he’ll cross it. He has crossed it. And Jeb Bush is a candidate who needs lines respected almost more than any other.But if Bush can’t drive out the donor-acceptable alternatives, Trump can. Trump is doing just that to Scott Walker right now. Four months ago, the clever thing to say about Walker was that he was the one candidate who could win both the base and the big donors. That unique strength has proved instead a unique vulnerability, as Walker has been whipsawed by the internal party argument over immigration. Walker—a strong-willed politician, but not a nimble one—has tangled himself in a sequence of contradictory answers. He has tumbled from first place in Iowa to third. Dependent on a smaller donor group than Bush, Walker is also more susceptible to donor panic. Walker is a real-world politician, with a job back in Wisconsin and other life options than the presidency. The candidate Bush supposedly feared most may end as one of the first to exit the race. (Necessary disclosure here: I worked in the White House of George W. Bush; my wife donated—modestly—to Scott Walker’s SuperPAC.)

Thank you, Donald.

The second reason Bush shouldn’t fight Trump: Even if Bush wins, he’ll lose. Jeb Bush is a candidate with many points of vulnerability: personal, familial, financial. Most of Jeb Bush’s Republican rivals will be reluctant to broach these issues in any but the most elliptical way. The norms of American media will inhibit journalists from reporting on them. If Bush can win the nomination, he can rely on the threat of mutually assured destruction to deter the equally vulnerable Hillary Clinton from pressing very hard.

But Trump is not playing by the usual rules. Show Trump a line, and he’ll cross it. He has crossed it. And Jeb Bush is a candidate who needs lines respected almost more than any other.

In the first Fox debate, for example, Trump talked about how beholden candidates become to their donors. Those remarks drew blood. And there will be more, if this tweet from today is any indication:

Why jump into this wrestling match? Trump may well deflate or make a lethal misstep or just get bored sometime before New Hampshire. If, after New Hampshire, the race devolves into a two-way Bush-Trump fight, Bush will surely have the upper hand. Until then, it’s in Jeb Bush’s interest to avoid tangling with a rival who seems to care more about damaging everyone else than electing himself. If he can’t convince his donors of that truth, then Jeb Bush’s greatest apparent strength—his fundraising—may be revealing itself as a nearly equal weakness.Via Int'l Business Times: Jeb Bush Got $1.3M Job at Lehman After Florida Shifted Pension Cash To Bank. http://t.co/UbprPUWHQ9

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 24, 2015

10 Years After Katrina, New Orleans Is Far From Healed

NEW ORLEANS—One thing that New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu wants everybody to remember is that the death and destruction that accompanied Hurricane Katrina wasn’t an act of God or nature.

“This was not a natural disaster—it was an infrastructure failure,” the mayor reminded the audience during the event “New Orleans: 10 Years Later,” hosted by The Atlantic.

A decade after the storm, the chronology—storm, breaking of the levees, and flood—tends to collapse into one giant event, particularly for those who weren’t there. That makes it easy to think that the disastrous floodwaters that overtook the city, and resulted in the death of thousands, happened as the hurricane tore through the Gulf Coast. But that’s not quite the case. When you ask New Orleanians about sequence of events, many remember a period between when the winds and rain ended and when the floodwaters began to rise. They describe going outside to calm and dry streets, believing that the worst was over and that the city had, once again, weathered a storm. Then the levees broke and the real disaster started.

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New Orleans

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New OrleansRead More

In 2005, Landrieu says that the government’s response, like the engineering of the levees, was wholly inadequate. As a result, the recovery has not been fast, nor is it complete.

One of the strongest criticisms heard in the past 10 years has been that government has continued to fail the most vulnerable populations, leaving them out of the city’s progress. In an earlier panel, Lolis Eric Elie, a writer and filmmaker, expressed frustration at the inequity saying, “I think our measures of progress are based on how quickly rich people are getting richer.”

Evidence of the discrepancies is abundant—the number of black residents who remain displaced is significantly higher than white residents. And while some affluent neighborhoods appear fully repaired, poorer sections of the city still bear Katrina’s scars.

Landrieu says that Katrina exacerbated existing issues within the city and that, on top of that, New Orleans is now facing the growing pains associated with a growing city. That growth is a good thing after the decades of population decline that preceded the storm, he said. “Cities have problems. I’d rather have the growth problem than the shrinking problem.”

Yet another problem is a large funding gap: For $150 billion in damages, the city received $70 billion in aid from the federal government, Landrieu said. “When you have that kind of gap, not everyone gets everything all the time,” he added.

This project was made possible with support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

How to Deal With Market Instability: Don’t Watch

The Dow dropped sharply this morning: The index was down more than 1,000 points at opening bell before recovering later in the morning. The news, following Friday’s 500 point drop, lit up Twitter and news headlines.

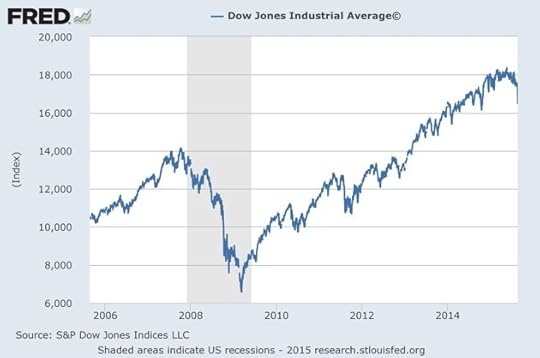

Some economists and commenters have already been pointing to the reasons not to panic. For example, this is the chart of the Dow’s 10-year performance for some perspective:

In these situations, that’s one among many reasons for some smart advice: just don’t watch. Ben Casselman over at FiveThirtyEight has an excellent roundup on why it’s silly to panic—namely that day-to-day moves in the market can be random, and additionally it’s near impossible to know what signal the market is sending. Further, Casselman highlights that less than half of U.S. households own stocks at all.

But what about retirement savings many people hold in the form of 401(k) plans? That depends on how long you’ve got before you plan on retiring. For people close to retirement, a market crash can severely set back plans. But for those whose retirement is decades off, their holdings have time to rebound. One study showed that even those who invested right before a stock market crash recovered their losses within a few years, or, as is the case may be today, perhaps even faster: By noon, the Dow had recovered to being down 150 points.

Nobel economist Robert Shiller says for ordinary investors, the wisdom is that it’s never bad to save more for retirement. When markets are high, it’s easy to overestimate one’s retirement savings. But when the markets are low, the right thing to do is to not panic, and just keep saving.

According to behavioral economics, watching the stock market fluctuations too closely will inevitably cause more bad feelings than good ones, as people feel much worse about losses than they feel good about gains. So just relax, let these guys handle it, and wait for the headlines change.

2016 Hopefuls Seize on Wall Street's Wild Day

There’s nothing like a plunge on Wall Street to turn a bunch of presidential candidates into instant experts on global financial markets.

Several 2016 hopefuls reacted quickly on Monday to the steep drop in the U.S. stock markets, and—surprise!—no one did so more aggressively than the wealthiest of the bunch, Donald Trump. In a series of tweets, media appearances, and even a video posted on Instagram, the GOP front-runner seized on the downturn to renew his oft-repeated warnings about the threat that China poses to the U.S.

As I have long stated, we are so tied in with China and Asia that their markets are now taking the U.S. market down. Get smart U.S.A.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 24, 2015

Markets are crashing - all caused by poor planning and allowing China and Asia to dictate the agenda. This could get very messy! Vote Trump.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 24, 2015

In a tweet linking to his Instagram post, Trump even dropped a mention of the dreaded D-word: “Depression.” In a quick, direct-to-camera message to his followers, Trump urged them to “be careful” without advising them specifically what to do.

Carly Fiorina, who like Trump made her name in business rather than politics, brought her own extensive experience with declining stock prices to the table. She responded more cautiously and analytically to the turmoil, which began with a major sell-off in Asian markets last week amid dismal economic data out of China. “I actually have been expecting a correction for some time,” she said in an appearance on the Fox Business Channel. “The market has been way too high given the fundamentals. Our economy is not particularly strong.” Fiorina attributed the stock-market highs that have been reached during the Obama era to the Federal Reserve’s “easy money” policies, which many conservatives have criticized. Now that the Fed is close to backing off those policies and raising interest rates, she suggested, the market is reacting. “So I think this is warranted, honestly,” she said.

Appearing separately on Fox News, Chris Christie directly blamed President Obama and his free-spending policies, arguing that the spike in the national debt during his tenure—much of which is held by China—had made the U.S. more vulnerable.

Now, as the Chinese markets have a correction, which they’re doing right now, it’s going to have an even greater effect because this president doesn’t know how to say no to spending, doesn’t know how to say no to a bigger and more obtrusive government.

Asked how he would respond to the market turmoil if he were in the Oval Office, the New Jersey governor said he would “rein this government in, stop running up some much debt.” It’s hard to see, however, how that long-term strategy would plug the—for now—short-term volatility in the markets.

Prolonged volatility caused by China’s downturn could benefit Trump, whose perceived business acumen is helping to fuel his unexpected staying power in the GOP polls. And in recent days, the real-estate tycoon has even struck a populist note by criticizing “hedge fund guys” who “shift paper around and get lucky,” saying they should pay higher taxes. But as Americans anxiously monitor the balances in their 401K plans, the market slide could also play right into the anti-Wall Street message of Bernie Sanders, who has railed against the banker class and wondered why executives who made irresponsible bets in the run-up to the last financial crisis weren’t punished. "We need banks that invest in the job-creating economy,” he tweeted shortly after the markets opened Monday and before a rally in New Hampshire. “We don’t need more speculation with the American economy hanging in the balance.”

Other candidates were slower to respond on Monday, perhaps waiting to see exactly how Wall Street would shake out by the end of the day. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 1,000 points at the open, but then it quickly rallied. Such caution may be prudent. But as John McCain learned in 2008, there’s a risk in waiting too long to recognize a crisis. Democrats skewered his remark, made while markets were tanking, that the “fundamentals of the economy are strong.” (His over-correction of that mistake didn’t help, either.) The sell-off may indeed be, in Fiorina’s words, a “warranted” correction that has little impact on the broader U.S. economy. But if it continues for even a few more days, don’t expect the other dozen-plus presidential aspirants to stay quiet for long.

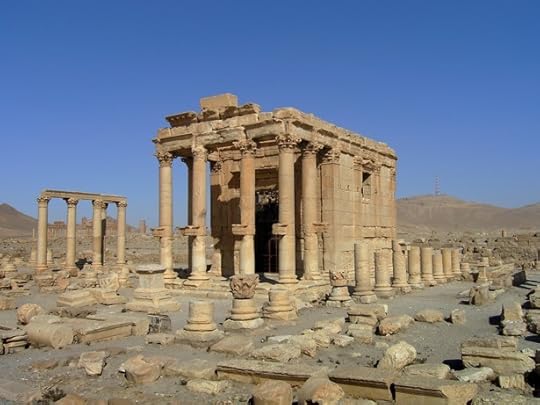

An Ancient Temple in Palmyra Is Destroyed

UNESCO is calling ISIS’s reported destruction of the Temple of Baalshamin—an ancient treasure in the historic city of Palmyra—a war crime.

Reports of the site’s destruction come just days after the Islamic State killed Khaled Asaad, an 82-year-old Syrian expert on Palmyra who refused to divulge the location of artifacts coveted by the militant group. Asaad had run Palmyra’s antiquities department for 50 years.

“The systematic destruction of cultural symbols embodying Syrian cultural diversity reveals the true intent of such attacks, which is to deprive the Syrian people of its knowledge, its identity and history” UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova said in a statement. “One week after the killing of [Asaad] … this destruction is a new war crime and an immense loss for the Syrian people and for humanity.”

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a U.K.-based activist group, said in a statement Sunday that ISIS fighters detonated explosives that were arranged around the Temple of Baalshamin. Maamoun Abdul Karim, Syria’s antiquities chief, confirmed that account to Reuters. But the two versions differed as to when the temple was destroyed.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the destruction occurred last month. Abdul Karim said it occurred Sunday.

Palmyra is a UNESCO Heritage site located northeast of the Syrian capital, Damascus, and the temple to the Phoenician god Baalshamin is one of its best-preserved sites. Here’s more from the U.N. agency:

Baalshamin temple was built nearly 2,000 years ago, and bears witness to the depth of the pre-Islamic history of the country. …

The structure of the Baalshamin temple dates to the Roman era. It was erected in the first century AD and further enlarged by Roman emperor Hadrian. The temple is one of the most important and best preserved buildings in Palmyra. It is part of the larger site of Palmyra, one of the most important cultural centers of the ancient world, famed for its Greco-Roman monumental ruins, repeatedly targeted by Daesh since May 2015.

As my colleague Matt Schiavenza wrote last week upon Asaad’s death:

Gruesome executions are an integral aspect of the Islamic State’s ruling style, but this killing illustrates the crucial role antiquities play in ISIS’s day-to-day governance. Part of this is symbolic: Muslim fundamentalist groups have long had a contentious relationship with cultural artifacts, particularly those that predate the rise of Islam in the 7th century A.D.

Born to Run and the Decline of the American Dream

Forty years ago, on the eve of its official release, “Born to Run”—the song that propelled Bruce Springsteen into the rock-and-roll stratosphere—had already attracted a small cult following in the American rust belt.

At the time, Springsteen desperately needed a break. Despite vigorous promotion by Columbia Records, his first two albums, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle, had been commercial flops. Though his band spent virtually every waking hour either in the recording studio or on tour, their road earnings were barely enough to live on.

Sensing the need for a smash, in late 1974 Mike Appel, Bruce’s manager, distributed a rough cut of “Born to Run” to select disc jockeys. Within weeks, it became an underground hit. Young people flooded record stores seeking copies of the new single, which didn’t yet exist, and radio stations that hadn’t been on Appel’s small distribution list bombarded him with requests for the new album, which also didn’t exist. In Philadelphia, demand for the title track was so strong that WFIL, the city’s top-40 AM station, aired it multiple times each day. In working-class Cleveland, the DJ Kid Leo played the song religiously at 5:55 p.m. each Friday afternoon on WMMS, to “officially launch the weekend.” Set against the E Street Band’s energetic blend of horns, keyboards, guitars, and percussion, “Born to Run” was a rollicking ballad of escape, packed full of cultural references that working-class listeners recognized immediately.

The rise of Bruce Springsteen is in many ways a typical rock success story, but it also reveals a great deal about one of America’s most contested eras. Since 1976, when Tom Wolfe branded the seventies as “the Me Decade,” Americans have tended to write off the era as a socially and politically barren time during which millions of people descended into mindless self-absorption. Standing in sharp contrast with the turbulent ‘60s, the ‘70s seem to have given rise to a popular repudiation of the high-minded spirit evident in the civil-rights, student, and anti-war movements.

But the story of the ‘70s is much more complicated. Far from being an era of complacency and narcissism, the decade gave rise to social, political, and cultural debates that built on and even surpassed the era of Kennedy and King. Some issues, like civil rights, the sexual revolution, and Vietnam, belonged as much to the ‘70s as to the ‘60s. Others, like feminism, abortion, gay rights, busing, the tax revolt, and Christian Right politics, seemed altogether new.

Considered in this context, Bruce Springsteen’s phenomenal breakthrough in 1975 can only be understood against a backdrop of profound dislocation and urgent activism, particularly in the working-class communities that absorbed so many of the decade’s economic and cultural shocks.

* * *

Reflecting on his formative years in Freehold, New Jersey, Springsteen once described the home he grew up in as a “dumpy, two-story, two-family house, next door to the gas station.” Several companies had manufacturing plants there—3M, Nescafé, the odd rug mill or paper plant—but by the post-war era, the city, like so many other middling urban areas, was dying. “Freehold was just a … small, narrow-minded town,” Springsteen told the English radio interviewer Roger Scott in 1984, “no different than probably any other provincial town. It was just the kind of area where it was real conservative. It was just very stagnating. There were some factories, some farms and stuff, that if you didn’t go to college you ended up in. There wasn’t much, you know; there wasn’t that much.”

Home wasn’t a happy place for Springsteen, and neither was school. A loner by nature, he coasted anonymously without leaving much of a mark. At Freehold Regional High School, he played no sports, participated in no extracurricular activities, and barely passed his classes, according to the biographer Dave Marsh. “I didn’t even make it to class clown,” Bruce later remarked. “I had nowhere near that amount of notoriety.”

Visions of a successful life in the U.S. and abroad

Visions of a successful life in the U.S. and abroadRead More

Years later, as the writer Eric Alterman recounts, one of Springsteen’s classmates reflected, “If he hadn’t turned out to be Bruce Springsteen, would I remember him? I can’t think of why I would. You have to remember, without a guitar in his hands, he had absolutely nothing to say.”

Springsteen’s only passion was music. He joined his first band, the Castilles, when he was still in high school. Their professional debut at the West Haven Swim Club led to a smattering of engagements at local roller-skate rinks, junior-high-school dances and supermarket openings.

After an unremarkable stint at Ocean County Community College, he relocated to Asbury Park, a gritty coastal community that scarcely resembled the glitzy seaside resort of its earlier days. By that time, jet travel and air conditioning had made distant locations like California, Florida, and the Caribbean more attractive to local vacationers. Deeply segregated and suffering from massive unemployment, the city erupted in violence between black rioters and a mostly white police force in July 1970, resulting in $4 million of property damage and 92 gunshot casualties. The town soon became a shadow of its former self—a half-desolate collection of small beach bungalows, decaying hotels, a modest convention center, and a handful of greasy-spoon diners.

But what it lacked in vigor and polish, Asbury Park made up for in artistic vitality. Lining its boardwalk were a motley assortment of bars where aspiring Jersey musicians like the drummer Vini Lopez, the keyboardists Danny Federici and David Sancious, the saxophonist Clarence Clemons, and the guitarist Steve Van Zandt—all of whom eventually played alongside Springsteen—forged a dynamic, interracial, and working-class rock-and-roll scene. The artists who eventually united under the banner of the E Street Band were revolting against the soft-pop sensibilities of acts like Donny Osmond, the Bee Gees, Chicago, America, Elton John, and the Carpenters, all of whom dominated the charts in the early ‘70s. Combining elements of jazz, funk, Motown, and rhythm-and-blues, the various incarnations of Springsteen’s bands—Child, Steel Mill, Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom, the Bruce Springsteen Band, and, finally, the E Street Band—enjoyed increasingly wide appeal among men and women from blue-collar families who frequented the Jersey shore music scene and who found the prevailing sound an inadequate soundtrack to their youth.

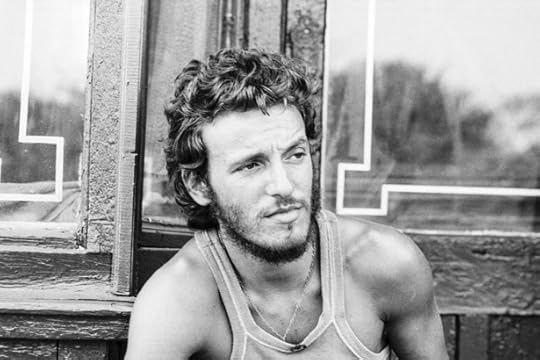

Frank Stefanko / Shore Fire Media

Frank Stefanko / Shore Fire Media Living in a dingy apartment atop a mom-and-pop drug store, Springsteen churned out hundreds of original songs packed with the rich imagery of working-class life. According to Marsh, Springsteen later observed that he “wasn’t brought up in a house where there was a lot of reading and stuff.” Yet for his lack of formal education, he developed into a master wordsmith, able to capture in lyrics the experience of millions of people who were trying to find their way in the troubled 1970s.

* * *

The ‘70s were a punishing time for America’s working-class communities. A brutal combination of commodity supply shocks, loose monetary policy, and federal deficits—the latter, a hangover effect from the Vietnam War—created both sky-high inflation and unemployment; the resulting phenomenon, which economists dubbed “stagflation,” interrupted a quarter-century of seemingly boundless growth and prosperity.

Compounding these challenges, many of the well-paying industrial jobs that once lifted blue-collar workers into the ranks of the American middle class began to disappear. In Youngstown, Ohio, steel plants were shuttering their doors by mid-decade, the result of foreign competition and failure to invest in new technology. In Elizabeth, New Jersey, the slow demise of the Singer sewing-machine plant, once the mainstay of the city’s economy, ushered in a period of post-industrial ruin. Sixty miles south on the New Jersey turnpike, Camden, the worldwide anchor of the Campbell Soup company, saw its manufacturing base drop from 38,900 jobs in 1948 to just 10,200 in 1982. Though each industry experienced its own, unique set of circumstances, the prevailing narrative was one of industrial decline.

Amid all this, blue-collar Americans were still reeling from the Vietnam War, a conflict that saw working-class men of all races do most of the fighting and dying. They were no less immune than anyone else to the general dissolution of authority—be it paternal, governmental, or civic—that seemed everywhere on display. And they were fully implicated in the creative cultural disruption of second-wave feminism and the modern gay-rights movement. In response to the decade’s turbulence, working-class communities exhibited a full range of grassroots political expression. Sometimes that activist spirit turned ugly, as with the anti-busing movement. But often, it didn’t.

Between 1967 and 1977 the average number of workers on strike climbed by 30 percent and the number of work days lost to stoppages by 40 percent. “At the heart of the new mood,” argued The New York Times, “there is a challenge to management’s authority to run its plants.” From striking postal workers in New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey to the United Auto Workers’ dramatic walkout against General Motors in 1970, blue-collar Americans demonstrated a degree of militancy unseen since the end of World War II.

In response to the decade’s turbulence, working-class communities exhibited a full range of grassroots political expression.Speaking to the grassroots labor engagement that pulsed through America in the ‘70s, a UAW official observed that “it’s a different generation of workingmen. None of these guys came over from the old country poor and starving, grateful for any job they could get. None of them have been through a depression. They’ve been exposed—at least through television—to all the youth movements of the last ten years … They’re just not going to swallow the same kind of treatment their fathers did ... They want more than just a job for 30 years.”

Workers didn’t limit their opposition to management. Often, they turned their sites on union leadership. The decade gave rise to unlikely heroes like Ed Sadlowski, the 38-year-old director of the United Steel Workers’ largest district (encompassing Chicago, Illinois and Gary, Indiana) who ran as a reform candidate for the presidency of his union’s international chapter. His fellow workers called him “Oilcan Eddie.” Rolling Stone magazine dubbed him an “old-fashioned hero of the new working class.”

Running on a multi-racial, multi-ethnic ticket, Sadlowski lost to the union’s establishment candidate by a convincing margin, but his brash style and willingness to acknowledge the drudgery associated with industrial labor played better than expected. His coalition—young, integrated, and restive—resembled nothing so much as Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band.

In the opening lines of “Born to Run,” Springsteen invoked one of his favorite metaphors—the automobile as an engine of escape from the many dead ends and disappointments that seemed to constrain young, working-class Americans. “In the day we sweat it out in the streets of a runaway American dream / At night we ride through mansions of glory in suicide machines / Sprung from cages out on highway 9 / Chrome wheeled, fuel injected, and steppin' out over the line / Baby this town rips the bones from your back / It's a death trap, it's a suicide rap / We gotta get out while we're young.” It was a fitting emblem for its time.

* * *

By the mid-70s, Springsteen was widely hailed as a “rock ‘n’ roll poet—someone who had ‘watched the crowds pass down the street, observed the hookers, the pushers, experienced the loose girls on the block and yet managed to keep just far enough away to keep out of major trouble,’” in the words of the Bucks County Courier Times. He radiated working-class authenticity. His songs “contain lyrics guaranteed to blow you away,” wrote a critic for the Syracuse Post-Standard, “telling of tenements, back alleys, greasers, pimps, jukeboxes, ‘switchblade lovers,’ ‘romantic young boys’ and ‘Billy,’ who’s ‘down by the railroad tracks, sitting low in the back seat of his Cadillac.’”

Lester Bangs, Rolling Stone’s highly influential rock critic, was an instant fan. “Hot damn, what a passel o’ verbiage!” he crowed. Some of his lyrics “can mean something, socially or otherwise, but there’s plenty of ‘em that don’t even pretend to.”

On October 27, 1975, both Time and Newsweek featured Springsteen on their covers, with Time hailing him as a “glorified gutter rat from a dying New Jersey resort town.” Praising his album as a “regeneration, a renewal of rock,” the magazine approvingly characterized Springsteen’s music, in his own words, as being principally concerned with “survival, how to make it through the next day.” Given the state of the country in October 1975—other topics that concerned Time that week included two assassination attempts on President Gerald Ford, New York City’s fiscal crisis, and the persistent after-shocks of Watergate—survival struck the editors as a noble enough goal on its own terms.

Newsweek disagreed. The magazine argued that Springsteen was a creature of his record label, which had launched a $250,000 promotional campaign for Born To Run. Indeed, not everyone was buying the hype. “Springsteen is said to be a new Bob Dylan,” quipped the syndicated columnist Mike Royko. “Bob Dylan was said to be a new Woody Guthrie. Woody Guthrie was not a new anybody. He was just Woody Guthrie. I guess that’s why he’s never going to be as big a star as Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen.”

When Kid Leo played “Born to Run” at 5:55 each Friday afternoon to “kick off the weekend,” he was offering musical escape.Springsteen’s critics misread his appeal. Absent from their analysis was class. The young heroes in “Thunder Road” and “Born to Run” are in flight from a very specific condition. Marsh recounts an interview in which Bruce explained, “I know what it’s like not to be able to do what you want to do, because when I go home, that’s what I see. It’s not fun, it’s no joke. I see my sister and her husband. They’re living the lives of my parents in a certain kind of way. They got kids; they’re working hard. These are people, you can see something in their eyes ... I asked my sister, ‘What do you do for fun?’ ‘I don’t have any fun,’ she says. She wasn’t kidding.”

When Kid Leo played “Born to Run” at 5:55 each Friday afternoon to “kick off the weekend,” he was offering musical escape. In “Thunder Road,” the narrator begs Mary to “roll down the window and let the wind blow back your hair/ Well the night’s busting open/ These two lanes will take us anywhere/ We got one last chance to make it real/ To trade in these wings on some wheels.” With 16 percent of non-college educated youth either unemployed or underemployed, and many of their more fortunate peers awaiting the next round of layoffs or cutbacks, the flight in Springsteen’s music had special resonance.

Shortly after Born to Run was released, Springsteen became embroiled in a highly public lawsuit with Mike Appel, his manager, who, in addition to demanding an excessive portion of his profits, badly mismanaged his concert and recording revenues. Only after the two parties reached a settlement in 1977 were Bruce and the E Street Band clear to return to lay down their next record. The product of their labors, Darkness On the Edge of Town, was released in 1978 to critical acclaim, followed by another best-selling record, The River, in 1980.

Both LPs revisited many of the same themes introduced in Born to Run. Rolling Stone called The River “a contemporary, New Jersey version of The Grapes of Wrath, with the Tom Joad/Henry Fonda figure—nowadays no longer able to draw on the solidarity of family—driving a stolen car through a neon Dust Bowl.” But what made the album “really special” was:

[Its] epic exploration of the second acts of American lives. Because he realizes that most of our todays are the tragicomic sum of a scattered series of yesterdays that had once hoped to become better tomorrows, he can fuse past and present, desire and destiny, laughter and longing, and have death or glory emerge as more than just another story.

* * *

To appreciate Bruce Springsteen’s social and political bent, it’s helpful to compare Born to Run to the competition. As popular as that album was, for millions of Americans who came of age in the 1970s, it was James Taylor, the six-foot-three, long-haired son of a wealthy North Carolina doctor, who supplied the decade’s soundtrack. With his sad eyes and brooding stare, Taylor captured the melancholy disposition of a country still reeling from the sixties

Released in 1970, his second album, Sweet Baby James—the one that made him famous—sold 1.6 million copies in just one year. Like his fellow singer-songwriters of the seventies, a talented and varied group that included Carol King, Joni Mitchell, Jim Croce, and John Denver, Taylor was interested in the mysteries of the self. “What all of them seem to want most,” Time noted, “is an intimate mixture of lyricism and personal expression—the often exquisitely melodic reflections of a private ‘I.’”

Springsteen embodied the lost seventies—the tense, political, working-class rejection of America’s limitations.Over the years, Taylor would give generously of his time and talent, appearing on stage to support liberal causes and political candidates. But social and economic concerns rarely seeped into his seventies-era compositions. There was too much personal ground to cover. Time noted that “like so many other troubled, dislocated young Americans, Taylor may at first seem self-indulgent in his woe. What he has endured and sings about, with much restraint and dignity, are mainly ‘head’ problems, those pains that a lavish quota of middle-class advantages—plenty of money, a loving family, good schools, health, charm, and talent—do not seem to prevent.” What was true of Taylor was also true of the era’s most successful singer-songwriters—from Carol King and Joni Mitchell, to Billy Joel and Jim Croce.

Critics of this new genre of songs about the self (known also as “I-rock”) risked glorifying earlier generations of musicians. Indeed, there was nothing especially political about the better part of the American songbook that predated the ‘70s. Those who longed for a more meaningful past would have strained to find deeper meaning in the bubblegum pop of the early and mid-‘60s. Even Bob Dylan eschewed most political themes after 1963, at least on the surface. But there was a distinction between the singer-songwriters and rock balladeers like Bruce Springsteen. Singer-songwriters represented the inward turn that we most popularly associate with the ‘70s—a very real phenomenon with authentic cultural resonance. By contrast, Springsteen embodied the lost ‘70s—the tense, political, working-class rejection of America’s limitations.

* * *

Lost amid popular memories of kitsch—of waterbeds and pet rocks, mood rings and self-help books—is the story of a more complicated decade. The enduring sway of Born to Run isn’t just thanks to the music, which stands up strongly, four decades later. It stems also from the unique time and place in which Americans first came to know Bruce Springsteen.

An intensely private figure, Springsteen rarely sat for interviews, particularly in the early years. But when he did, politics was never far from his mind. “I don’t think the American Dream was that everyone was going to make it or that everyone was going to make a billion dollars,” he later said (as captured in the anthology, Bruce Springsteen Talking). “But it was that everyone was going to have an opportunity and the chance to live a life with some decency and a chance for some self-respect.”

It’s been 40 years since “Born to Run” first captivated the popular imagination. In many ways, we’re living in a comparatively prosperous decade: Downtown Freehold has been restored to its original splendor, and the Asbury Park boardwalk is lined with upscale bars and restaurants catering to an upwardly mobile crowd. Yet Americans still grapple with the same concerns that animated a young Bruce Springsteen. The place and condition of one’s birth continue to define the outer boundaries of possibility. All of which makes the music as meaningful as it ever was.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower