Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 361

August 24, 2015

Peggy Hubbard's Attack on Black Lives Matter

Over the weekend, at least 7 million people watched Peggy Hubbard, a black grandmother, excoriate the Black Lives Matter movement in an emotional video posted to her Facebook page. 71,000 people liked the post. 16,000 people left comments. And discussions like this one on Reddit rippled out across the Internet.

Two breaking news events prompted the U.S. Navy veteran, who grew up in Ferguson, Missouri, to speak out and share her feelings. In the first, two white police officers killed Mansur Ball-Bey, a young black man. Police say that he tried to flee out the back door of the house where they were serving a warrant and that he pointed a stolen gun at them before they shot, a narrative that his family disputes. In the second news story, 9-year-old Jamyla Bolden was killed by a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting as she lay in her mother’s bed. The perpetrator is unknown.

Hubbard’s video commentary tied these disparate events together:

Last night, who do you think they protested for? The thug. The criminal. Because they’re hollering police brutality. Are you fucking kidding me? Police brutality? How about black brutality. You black people, my black people, you are the most violent motherfuckers I have ever seen in my life. A little girl is dead. You say black lives matter? Her life mattered. Her dreams mattered … Yet you trifling motherfuckers are out there tearing up the neighborhood I grew up in.

There is police brutality, she said, but people who believe that black lives matter ought to be protesting black-on-black murder:

You’re hollering this ‘black lives matter’ bullshit. It don’t matter. You’re killing each other. White people don’t care … You’re shooting at the police. They drop your ass. ‘Oh, he died due to police brutality.’ 327 homicides later y’all want to holler police brutality? Black people, you’re a fucking joke. You’re tearing up communities over thugs and criminals.

She had thousands praising and excoriating her. “I had a lot of positive feedback from a lot of people from my black community to keep going,” she wrote in a follow-up post. “I also had a lot of negative feedback from people in black communities.” On Saturday, after more reflection, she posted a new video. She began by apologizing for her profane language. “That is not me,” she said, explaining that she was very upset “because of the deterioration of our society and our neighborhoods, and losing that little girl. As a mother, as a wife, as a grandmother … I have a grandchild that age, and it broke my heart, because what if it was mine?”

She pledged to refrain from profane language going forward––and said she has no intention of shutting up. “Given all the comments I received, black and white, saying, ‘Don’t stop, we need your voice,’ I’m going to keep going,” she said. “This is not a race issue. It never has been a racial issue ... This is about accountability and responsibility ... Last night we had another homicide … and we’re saying black lives matter. Black lives matter, white lives matter, Asian lives matter, Hispanic lives matter, Lithuanian lives matter, Russian lives matter, life in general matters … but it’s never gonna get better until we admit that we have a problem in our community.”

* * *

If anyone is surprised by Hubbard’s emergence, or that there are like-minded black people who are encouraging her, it is only because large swaths of the media cover the black community as if conservative voices like hers don’t even exist.

In fact, she is the latest incarnation of a black conservatism that has been around more than a century. Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote a 2008 feature story on its last public champion, Bill Cosby, who roiled American discourse on race with what has come to be known as his “pound cake speech.” He declared, “Looking at the incarcerated, these are not political criminals ... People getting shot in the back of the head over a piece of pound cake! And then we all run out and are outraged, ‘The cops shouldn't have shot him.’ What the hell was he doing with the pound cake in his hand?”

With dozens of women now asserting that Cosby drugged and sexually assaulted or raped them, he is no longer a viable bearer of this message.Many black people criticized Cosby for that speech. “But Cosby’s rhetoric played well in black barbershops, churches, and backyard barbecues,” Coates wrote, “where a unique brand of conservatism still runs strong. Outsiders may have heard haranguing in Cosby’s language and tone. But much of black America heard instead the possibility of changing their communities without having to wait on the consciences and attention spans of policy makers who might not have their interests at heart.”

With dozens of women now asserting that Cosby drugged and sexually assaulted or raped them, he is no longer a viable bearer of this or any other message. But the constituency for which he spoke did not disappear. It was bound to find another champion. In the era of social media, why not a heretofore unknown grandmother? She’s already being attacked in the awful way black conservatives so often are––she reports being called delusional, “the white man’s bed wench,” and “a house nigger.” As yet, she is not being defended by the progressives who typically urge deference to women of color, condemn “tone-policing,” and insist that white people are “speaking from a place of privilege” when they disagree with a black woman.

Hubbard’s response to her diverse critics has drawn on the language of inclusion. “I love my black people. I love my white people. I love my Hispanic people. I love my Asian people. My heart is so full of love for people that it has no room for hate,” she says. “The way I see it, it’s not a black race, it’s not a white race, it’s not an Asian race, it’s not a Hispanic race, it’s not a Latin race, it’s a human race. And right now, the black community, what we’re racing towards is the morgue. Let’s stop it. If you want to help me, help me. If you don’t want to help me get out of the way.”

* * *

I share Peggy Hubbard’s alarm at murder rates in poor, black neighborhoods; her dismay at the death of a 9-year-old girl; her aversion to property damage; her belief in the importance of individual responsibility; and even her skepticism about protesting Ball-Bey’s death given the evidence that has so far emerged. But significant parts of her critique of Black Lives Matter seem unfair and wrong, even if the anger and frustration she feels is understandable given her life experiences: a brother and a son who apparently destroyed their lives by choosing to engage in crime.

She’s right that a young, black man in a poor neighborhood is much more likely to be killed by a violent criminal from a nearby block than by an abusive cop out patrolling. And it’s true that good cops are needed to protect people in those same neighborhoods. But the Black Lives Matter agenda isn’t inconsistent with either of those propositions. The movement doesn’t explicitly tout the importance of policing, but it does advocate reforming police departments, not abolishing them. And it does so with overwhelming evidence of deadly abuses and incompetence and the accurate perception that blacks are disproportionately victimized.

For those reasons, urging reforms that would reduce police abuses and improve training is eminently defensible, regardless of how many black men are killed by criminals. The young activists of Black Lives Matter can realistically improve policing policy by bringing the public’s attention to a problem and lobbying for known remedies. In contrast, the problem of violent crime is longstanding universally acknowledged; and there’s no reason to think murderers would murder less if these young, black activists loudly demanded it, especially given that lots of voices in the black community have long inveighed against and worked to stop black-on-black crime.

If President Obama, countless black parents, church leaders, and famous rappers haven’t yet stopped black-on-black murder by denouncing it, it’s reasonable to conclude that Black Lives Matter pays a low opportunity cost by focusing its protests on policing. Perhaps that reasonable conclusion is nevertheless incorrect; maybe violent crime really could be reduced if only more voices joined Hubbard in denouncing violent crime and touting the need for personal responsibility. If so, she’d do better to organize that movement than to complain that other people, who’ve spent more time and energy than she has on activism, have chosen a different goal.

Reforming police and reducing crime are both worthy projects––and despite what some defenders of status-quo policing would have us believe, they need not be at odds with one another. Note, too, that many of the Internet critics who want Black Lives Matter volunteers to spend more time protesting crime in urban centers have themselves done nothing in service of that goal besides criticizing Black Lives Matter.

Hubbard’s most unfair attacks are glaring to an individualist.

The fact that some young black men carry guns and commit violent crimes doesn’t mean that other young black men and women should have their activism discredited.“You’re hollering this ‘black lives matter’ bullshit,” Hubbard said. “It don’t matter. You’re killing each other.” In fact, the overwhelming majority of people hollering “black lives matter” have never killed and will never kill anyone. The vast majority of Black Lives Matter protestors are not “tearing up the neighborhood” either. These race-based generalizations rob their objects of individual identities. The fact that some young black men carry guns and commit violent crimes doesn’t mean that other young black men and women––totally distinct individuals who happen to share the same skin color––should have their activism discredited, enjoy fewer civil liberties, or be at increased risk of being killed by cops. It is interesting that the various right-wing news sites that picked up this video failed to catch these flaws, despite fancying themselves champions of individualism, color-blindness, and the rights contained in the United States Constitution.

Hubbard was speaking off-the-cuff at a moment of high emotion; it’s possible that she hasn’t fully considered all the implications of her views; but as stated, they are wrongheaded. She might’ve been on solid ground if she’d stopped at arguing that police were justified in shooting Ball-Bey and that Black Lives Matter was wrong to protest that particular killing; instead, she spoke as if the Ball-Bey encounter bears on the righteousness of protesting other deaths, like Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, or any of the other black men that police officers have been indicted for murdering.

* * *

Despite these significant disagreements, I’m glad Peggy Hubbard spoke out on Facebook. It’s generally a good thing when citizens earnestly express their views in public discourse, and she deserves kudos for trying to improve her community as best she can. She has articulated beliefs that are shared by a lot of people, which is itself an important service: Insofar as those beliefs are inaccurate or wrongheaded, better that they be aired and debated than invisible and unexamined.

This viral video and the comments around it also represent an opportunity for the activists of Black Lives Matter to understand how some critics of their movement perceive the world, to engage in conversation and debate, to refine any weaknesses in their own thinking that emerge, and to persuade their interlocutors to adjust some of their positions. In fact, despite Hubbard’s harsh words, I’d bet that, properly engaged, she could be persuaded to voice support for at least a portion of the policing-reform agenda. If so, what an ambassador she would make to millions of potential converts.

How France Is Rewarding Three Americans Who Thwarted a Gunman on a Train

Three Americans who eschewed the title of heroes even after preventing what would have likely been a massacre aboard a Paris-bound train Friday were awarded France’s highest honor Monday.

“Your heroism must be an example for many and a source of inspiration,” French President Francois Hollande said at a ceremony Monday to honor the three Americans—Airman First Class Spencer Stone, 23; Alek Skarlatos, 22, a specialist in the Oregon National Guard; and their friend Anthony Sadler, 23—and a Briton, Chris Norman, 62. “Faced with the evil of terrorism, there is a good, that of humanity. You are the incarnation of that.”

The four men, and others, overpowered the suspected gunman, Ayoub El Kahzani. Hollande said Kahzani was in possession of 300 rounds of ammunition and firearms. The Moroccan suspect in the failed attack is in police custody. French media quote his lawyer as saying Kahzani was not planning a terrorist attack, but was trying to rob a passenger.

If you’re just coming to this story, here’s a recap from The New York Times:

The three friends were on a tour of Europe that included stops in France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. They had originally intended to spend Friday night in Amsterdam but changed their minds and boarded a high-speed Thalys train to Paris. Shortly after the train crossed the Belgian border into France, they heard a shot, saw a gunman with an AK-47 and rushed to stop him.

A French citizen who was the first to tackle Mr. Kahzani but who has declined to be identified will receive the honor at a later date, as will Mark Moogalian, 51, a passenger with dual French and American citizenship who struggled with the attacker and is recovering from a bullet wound.

Stone was injured, too. The suspect cut his thumb, and the airman wore his left arm in a sling, and had a bruised eye at Monday’s ceremony. Hollande pinned the Legion of Honor on Stone and his friends, who were dressed in polo shirts and khakis, a contrast to the highly formal ceremony at the Elysée Palace.

The ceremony was a culmination of French public demand that the men be awarded the honor—created by Napoleon in 1802— for “outstanding merit” for their role in stopping the attack.

“These days you see a lot of celebrities pick up the medal ( … ),” France 24’s Douglas Herbert reported, “but the actions these men were rewarded for are perhaps the ideals to which Napoleon aspired when he created the award.”

In New Orleans, Business Is Booming—for Some

NEW ORLEANS—When George W. Bush climbed atop a stage in the middle of New Orleans’s Jackson Square and announced that the city was open for business shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit, he was overstating the case. The lights used to illuminate his stage stood in stark contrast to the rest of the parish, where electricity, food, and clean water were all in short supply. New Orleans was far from a functioning business center.

NEW ORLEANS—When George W. Bush climbed atop a stage in the middle of New Orleans’s Jackson Square and announced that the city was open for business shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit, he was overstating the case. The lights used to illuminate his stage stood in stark contrast to the rest of the parish, where electricity, food, and clean water were all in short supply. New Orleans was far from a functioning business center. In the storm’s aftermath, New Orleanians were putting the pieces of their lives back together—reaching out to relatives, trying to find places to stay, wondering if their homes had been destroyed, if things would ever go back to normal. Those who owned businesses also had that to worry about. Iam Tucker’s father, who ran a New Orleans-based engineering business, Integrated Logistical Support Inc., was one of them. He worked remotely from Florida and Baton Rouge, trying to win contracts for the firm to keep it afloat. The company’s vice president was at work too, writing proposals by candlelight, still in the devastated city. When a project to inspect the levees was won, the firm’s inspectors had to live and work out of their cars for a time. “The staff was literally scattered all over the place,” Tucker says. “It was a very scary time.”

But those scary times were also a moment of opportunity, and in the years since, there has been a surge in small-business growth in the city, said Tim Williamson, one of the founders of Idea Village. “After Katrina, in a unique weird way, everyone became an entrepreneur. The city was closed, so everyone had to start over with tons of uncertainty and limited resources.”

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New Orleans

What's been learned since the hurricane struck New OrleansRead More

Williamson says the return of small business has come in three waves: Right after the storm, retailers who had existing businesses headed back first. They were followed by former New Orleanians who were drawn back to the city, and opened up new stores or took over family businesses. Finally, there were the outsiders, who saw the opportunity for entrepreneurship as the city healed.

A few years on, in 2008, Tucker was a part of that second wave, coming back to her native New Orleans, after a stint in Baton Rouge as a police officer, to run the family business. She makes up a growing class of small-business owners in the city, but as a black woman business-owner, she’s part of a much smaller group.

Ten years after the storm, much of New Orleans feels new, especially to those born here. It’s difficult to assess the number of residents who lived in the city before the storm versus transplants who moved in afterward. But the city’s changing demographic vibe is unmistakable, with more white and affluent residents moving in. Now it’s fair to say that business in New Orleans is by many counts booming. Between 2011 and 2013, entrepreneurship growth in the New Orleans metro area outpaced the national rate by 64 percent.

But the success is uneven. Tucker says that New Orleans’s small-business economy tends to be very white. She’s not the only one who sees the inequity. Williamson agrees that when you look at the businesses that are thriving, they’re predominately headed by white males. Everyone agrees that there’s much work to be done when it comes to diversifying the small-business sector so that more minority- and women-owned businesses can reap the benefits of the city’s revitalization, but coming up with a plan to make that happen is a challenge.

New Orleans’s economy was badly in need of help even before the storm hit. The city saw a 30 percent population decline between the 1960s and the early aughts. There wasn’t even a dedicated economic-development organization, according to Quentin Messer, the CEO of the New Orleans Business Alliance.

Following the storm, rebuilding was especially difficult for the poor and minorities, whether it was their homes or their business they were trying to fix. “It was really hard for black people to get back. It was the black areas like New Orleans East and Ninth Ward and other areas that were inundated much, much stronger than say, Uptown New Orleans,” Tucker says. And getting aid from FEMA was often a confusing process. “If you talked to five different FEMA agents, you'd get five different answers,” Tucker says.

Since about 2010, the number of businesses owned by economically or socially disadvantaged people, referred to as disadvantaged business enterprises (DBE), has doubled, from 300 to 600. But the success is limited. The city has set a goal of using DBEs for 35 percent of the work on any city-funded project, but it has fallen short, and only about 12 to 16 percent is, Tucker says. “The businesses are here, we've come back, we've invested back in the community, we've jumped through the certification hoops, we're ready to do work,” she says.

Tucker says that the new blood and competition are welcome, good even. But a problem arises when it comes to who is benefiting from the New Orleans’s “booming” small-business industry. “It's booming for everybody, but us,” she says.

Still Tucker is hopeful. She says the mayor’s office has agreed to a disparity study, which would look into the lack of diversity in government gigs, and she thinks that will help. But she’s also frustrated. She says that when she and other minority business owners see commendations about the city’s small-business sector, she doesn’t recognize the progress they’re talking about.

“The residents that are from here and look like me, we're not feeling that,” she says. “I want to see my city recover. But, I want to see it recover equitably—that's what I'm worried about.”

This project was made possible with support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation.

August 23, 2015

When the Levees Broke

When it comes to films and TV shows about Hurricane Katrina, a few in particular tend to stick out. Most notably, Benh Zeitlin’s Oscar-nominated film Beasts of the Southern Wild and David Simon’s HBO series Treme, both of which were met with acclaim and warm critical receptions. Then there’s whacked-out action fare including Déjà Vu and Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, which use post-Katrina New Orleans to provide a gritty backdrop for their offbeat narratives. No list of Katrina films would be complete without David Fincher’s wildly divisive The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, which incorporates Katrina’s landfall as a framing device for a melancholy story about the ravages of time, to mixed results. But few have seen or heard of Zack Godshall’s 2007 film Low and Behold, which was the first feature film to dramatize Katrina and which Sundance released on a slew of on-demand platforms on August 18 to mark the 10-year anniversary of the storm.

Related Story

Beasts of the Southern Wild Director: Louisiana Is a Dangerous Utopia

The film, which follows an insurance adjuster as he surveys the remains of New Orleans, was made in 2006, just eight months after Katrina made landfall, when the city was still struggling to pull itself out from under the rubble left by the failure of the levees. However, despite premiering at the 2007 Sundance Film Festival, Low and Behold never received an official theatrical or video release. So why should viewers see this obscure film now, 10 years after Katrina, if at all? Not only is the movie itself aesthetically stunning, but it’s also one of those rare commercial films about a large-scale tragedy that manages to express something true and meaningful without coming off as pandering or exploitative. It’s this balance that perhaps makes Low and Behold the best film about Hurricane Katrina that most people have never seen.

It’s a given that any commercial film claiming to be “based on a true story” is in some way exploiting a real-life event, perhaps to inspire, inform, or infuriate, but almost always to profit. Still, things get dicier when it comes to a for-profit film representing a massive disaster like 9/11 or Katrina. These films must negotiate the slippery intersection of tragedy, art, and exploitation in the struggle to pay the proper respect to the event while also managing to express something true about it in an artful way. It’s an aesthetic tightrope walk, and often the pressure is too much for the film to bear, generally resulting in an overly cautious, toothless film filled with platitudes. For every United 93, there are three World Trade Centers.

Low and Behold belongs to the small group of films that gets it right. And “getting it right” goes far beyond the film’s treatment of New Orleans residents and Katrina’s victims, something that Louisiana natives are notoriously persnickety about. More simply, the film guides the audience from an outside position of voyeuristic exploitation to an inside position of empathetic understanding. In short, Low and Behold doesn’t try to dodge the intersection of tragedy, art, and exploitation—it addresses those problems head-on through its choice of characters, the storylines, and the filmmaking style itself.

The film wastes no time in immersing viewers in the cynical world of profiteering. Unlike the stars of other Katrina productions, the film’s main character, Turner Stull (co-writer Barlow Jacobs) isn’t a victim. He’s an insurance adjuster coming to New Orleans to work for his uncle (Robert Longstreet) and make a little cash off the epic misfortunes of others. In another era, he’d be called a carpetbagger, but in any era, he’s no hero. Before Turner can even unpack his things, Uncle Stull throws a company polo at him and enlists him in his first act of cold-hearted opportunism, which is to help Uncle Stull move in a sofa that he took from “an abandoned Baptist church.” This moment, while innocuous in and of itself, captures the truth of their role in the city, showing how their comfort—literally—comes at the expense of someone else’s.

The reality of what they’re doing in New Orleans never occurs to Uncle Stull and the other adjusters. In fact, they actively craft a narrative that paints them as heroes rather than pillagers. An early party scene expresses this idea even more explicitly. In a homage to the greed-soaked pep talks from Wall Street or Glengarry Glen Ross, Victor (Mark Krasnoff), whom Uncle Stull calls “the god of insurance adjusters” rallies the new employees of his company, Bridge Catastrophe Services, by telling them about what he prays for every night: “a catastrophe that causes massive property damage” but claims no lives. “This is the business we are in,” he says. “There is Mother Nature ... and the insured. We are the Bridge.”

As altruistic as he tries to sound, this bridge’s only purpose is to connect the adjusters to their share of the insurance payouts, with the victims wallowing anonymously in the water below. Uncle Stull, a character incapable of such rhetorical niceties, puts it bluntly: “We’re insurance adjusters, not the Red Cross.” It’s moments like these early on that make the viewers rather uncomfortable—they realize they’re following the bad guys. Perhaps the viewers even are the bad guys, and Low and Behold makes them worry whether there’s anything that they, as outsiders to the tragedy, can do to understand, let alone make things better.

The viewers’ dilemma makes Turner an ideal character for a film about Katrina because he becomes a stand-in for them as he moves from being a detached observer to an engaged participant. At first, he tries his hardest to limit his exposure to the tragedy of Katrina. It’s 15 minutes per house, tops, because time is money. But as Turner gets more immersed in the job, he becomes more interested in assessing the damage done to the people, not the property, to his uncle’s dismay. This is what happens to the audience as well: With the help of a camera, viewers come to Low and Behold to see a damaged New Orleans, a city drowning in mold and debris that no production designer or CGI wizard could recreate. Soon they not only find themselves transformed by what they see—they, like Turner, even begin to see differently.

Turner’s conversion begins when his ladder falls out from under him, leaving him stuck on a roof and begging a local named Nixon (Eddie Rouse, in an endearing, layered performance) to rescue him. The irony here works on several levels: Even though he’s on high ground, Turner finds he is no longer in the superior position he previously enjoyed. He had to climb up on a roof to be brought down to size. The deeper irony, however, is that in losing his ladder, Turner becomes like the scores of People Stuck on a Roof who flooded television screens in the days after Katrina. Now that he’s experienced a taste of what the victims of Katrina went through, he can start to empathize.

The filmmaking is always ahead of Turner and the audience in this journey. In Turner’s hands, the camera starts out merely as a tool to document the damage so that he can make money; however, in Godshall’s hands, the camera turns into a witness to the testimony of others. The film blends scripted scenes with improvised bits and documentary footage, opening up the structure of the film to be looser and more responsive to the real events that happened during production. In fact, when the film begins, it’s unclear whether it’s documentary or fiction, because shots of a car driving across a bridge are intercut with a subtitled interview with an iceman whose life has been washed away. It takes several minutes before viewers understand the film’s hybrid approach, by which point they’ve already surrendered to the way Godshall wants to tell the story.

Though film is an inherently visual medium, Low and Behold makes the act of listening, rather than speaking, its aesthetic principle. Turner complains that the victims are slowing down his progress because “they won’t stop” telling their stories to him. For an exploiter, listening is a liability. But the narrative often stops moving forward to listen to survivor testimony via formal interviews or chance encounters on the street. In doing so, the film allows these nonprofessionals to take control of the film’s direction. While this may come off as undisciplined filmmaking, it’s also the empathetic, less agenda-centered approach necessary to avoid taking advantage of the victims while cutting them out of their own story.

Godshall’s film adapts to the situation on the ground and often lets the events tell themselves. As a result, he captures the bleak reality of post-Katrina New Orleans, an empty city populated with a few hundred people who can only comb through what used to be their homes in a dazed despair. The movie is filled with small graceful notes, like a moment when two debris clearers, who don’t seem to be aware of the camera filming them, find a barbell in the rubble and take turns doing reps and laughing. In these scenes, Godshall captures south Louisiana in its most accurate form—a place where the tragic and the comic perpetually coexist as residents try to reimpose order on their environment.

There’s an impossible gulf between the people who experienced Hurricane Katrina and those who didn’t, especially 10 years later. But Low and Behold reveals to viewers that this gulf only seems unbridgeable, and that the camera can carry the audience to a place it cannot reach on its own. As extended metaphors for the film, ladders and bridges could not suit Low and Behold better. They’re not just about connecting one thing to another: They also take people up. Ladders and bridges are outlets of escape, rescue, and ascent. The film might have more narrative closure if its final shot were on a bridge, but instead Godshall ends the film with the camera traveling down a road alone. What this ending makes abundantly clear is that, while we may keep moving at the end of the film, there’s no going back to the way things were before, not for the survivors, not for the audience, not for anyone, not even 10 years later. But once a bridge has made a connection, it’s not an easy thing to destroy, even for a hurricane.

August 22, 2015

The West's Wildfire Season Gets Worse

A historic wildfire season in the Western United States and Canada claimed more victims last week. Three firefighters battling the Twisp Fire in central Washington State died Wednesday after their vehicle crashed and was overtaken by the flames, NBC News reported. Four other firefighters were also injured.

The three firefighters’ deaths marked a dangerous week for fire crews battling blazes throughout the West. Over 7.2 million acres have burned this year, according to the federal National Interagency Fire Center, with 1.3 million of those acres actively burning on Thursday. In the Pacific Northwest alone, wildfires grew from 85,000 acres to 625,000 acres in only a week. Canadian firefighters also struggled with blazes this summer, with over 690,000 acres burned in British Columbia as of August 4, according to the Globe and Mail.

Fire season is a difficult time for Western states in any year, but the dire lack of rainfall in recent years has exacerbated the current threat. Most news outlets refer to the crisis as “the California drought.” In fact, the drought exists in some form across the entire Western United States:

One hundred percent of the state of Nevada is in drought — with 40 percent in the extreme drought category. Over to the southeast, 93 percent of Arizona's territory is in some form of drought. Even Washington state, far to the north, finds all of its territory in drought and 32 percent of its land in extreme doubt.

Although some media outlets have focused on almonds, a much larger contributor to warming temperatures and drying landscapes is climate change. A study published in Geophysical Research Letters on Thursday estimated that climate change’s effects exacerbated the Western drought by an additional 15 to 20 percent. That same day, NOAA announced that July 2015 was the hottest month since recordkeeping began in January 1880. As climate change continues to worsen, longer and more intense droughts are likely.

Wildfires can occur year round, but they flourish in dry, hot conditions like those caused by the drought. In April, the Lake Tahoe basin, which straddles the California-Nevada border, recorded only 3 percent of its typical annual snowpack, according to the Reno Gazette-Journal. Snowpack is the primary source of water for mountainous areas throughout the year; its absence has serious ecological repercussions. An aerial survey earlier this month in one part of the Sierra Nevada foothills found almost 6.3 million trees—about 20 to 30 percent of those surveyed—were dead or dying. As snowpack dwindles and temperatures rise, wildfires move into even higher elevations that rarely burned in previous fire seasons.

With so many wildfires burning across the West, state and federal resources are stretched thin. In Washington, 200 soldiers from Joint Base Lewis-McChord outside Seattle have been activated to assist local crews. New Zealand and Australia also deployed a 70-person team to assist. California augments its 4,000 full-time firefighting personnel with 6,000 inmates from state prisons.

Another hurdle faced by the U.S. Forest Service is cost. In 1995, the agency said, about 16 percent of its budget went to fire-related costs. Now, it occupies about 52 percent of the budget, and is projected to consume two-thirds of the budget by 2025. Because federal wildfire spending comes from agency budgets, active fire seasons can deplete resources for wildfire prevention. Earlier in August, a group of Western lawmakers proposed legislation that would allow firefighting agencies to draw from natural-disaster funds instead.

Stephen Colbert and 21st-Century Mystics: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Notes on 21st-Century Mystic Carly Rae Jepsen

Jia Tolentino | The Awl

“Carly Rae Jepsen is a pop artist zeroed in on love’s totipotency: the glance, the kaleidoscope-confetti-spinning instant, the first bit of nothing that contains it all. This is audible and immediate in her voice, whose definitive quality is a childlike ardency inflected with coyness; she sings like her smile is bursting, like there are stars imploding in her eyes.”

Rap and the New Rock Star: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

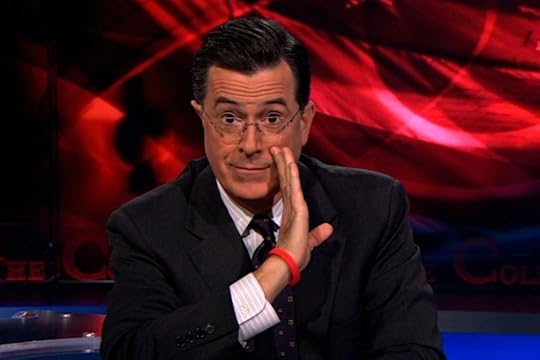

The Late, Great Stephen Colbert

Joel Lovell | GQ

“And then we got onto the subject of discomfort and disorientation, and the urge he has to seek out those feelings, and from there it was a quick jump to the nature of suffering. Before long we were sitting there with a plate of roast chicken and several bottles of Cholula on the table between us, both of us rubbing tears from our eyes.”

Who Is Marc Jacobs?

Sarah Nicole Prickett | The New York Times Style Magazine

“One of his tattoos is an all-caps ‘perfect’ on his wrist, reminding him that he’s exactly who and where he’s supposed to be at that moment, and that everything is good because it’s there. It’s really about acceptance, not perfection. He wants to make precious things that people aren’t precious about.”

Holding Off Emily Dickinson’s Complete Poems

Dwight Garner | The New York Times

“I could not stop for Emily Dickinson, but she kindly stopped for me. Her raw, spare, intense poetry was written as if carved into a desktop. Now that I am older and somewhat wiser, what I prize about Dickinson is that she lives up to her own observation: ‘Truth is so rare, it is delightful to tell it.’”

Here’s What’s Missing From Straight Outta Compton: Me and the Other Women Dr. Dre Beat Up

Dee Barnes | Gawker

“That’s reality. That’s reality rap. In his lyrics, Dre made hyperbolic claims about all these heinous things he did to women. But then he went out and actually violated women. Straight Outta Compton would have you believe that he didn’t really do that. It doesn’t add up.”

“Happily Ever After” for African American Romance Novelists

Christine Grimaldi | The Rumpus

“ ‘People need to see that love is love, regardless of who you are, whether you love someone of color, whether you love another woman,’ Jenkins said. ‘Love is love.’ In a society that routinely relegates black women to the margins, or worse, romance novels underscore that their desires and their bodies are worthy of happily ever afters.”

‘Dead’ Again: AMC’s Promising Return to Zombieland

Andy Greenwald | Grantland

“One of the sharpest choices made in Fear the Walking Dead is the way it doesn’t rush past the frustrating banalities of existence en route to the apocalypse. Perspective matters: We need to appreciate the leaky faucet before we can attend to the gushing artery.”

The Abridged History of Disney, 2015-2040 AD

Chris Plante | The Verge

“Audiences are more likely to watch reality shows in which all contestants wear superhero costumes than they are to watch similar reality shows in which superhero costumes are not prominently featured, according to a report from the Paley Center for Media.”

I Spent Four Seasons as Amy Poehler’s Stand-In

Hadley Meares | Atlas Obscura

“For years, I have described my job thusly: I am a moving piece of furniture. I am a crash test dummy with a working mouth. I am the understudy that never overtakes. I am the cheat sheet. The technical term for my job is ‘stand-in.’”

Why You Can’t Look Away From the Affleck Nanny Scandal

Adam Sternbergh | Vulture

“Ouzounian’s so fascinating because she’s our modern civilian surrogate, who’s passed over to the other side of the glass. Someone finally found a way to photobomb celebrity. Can’t you see her? There she is, popping up in the rolling Instagram feed of the famous, and she’s waving at us, and we can’t look away.”

The War That Congress Won't Declare

“To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle,” George Orwell wrote in 1946. Here’s a corollary: The real scandal in any given system is usually the thing there’s no argument about.

We hear a lot of discussion about executive power and the military these days. The Internet is flooded with discussions of whether President Obama has the authority to send troops to Texas. The true constitutional crisis, however, is not Jade Helm, it’s Inherent Resolve, the so-called war against the Islamic State. I’m not hearing much about that

Related Story

The War Against ISIS Will Go Undeclared

Almost exactly two years ago, President Obama proclaimed that the national interest required intervention in Syria to punish the Assad government for using chemical weapons against its own people—not only a war crime, but, Obama said, a “red line” for the international community. Shortly afterwards, though, Obama unexpectedly announced that he would first seek congressional authorization. “After careful deliberation, I have decided that the United States should take military action against Syrian regime targets,” he said on August 31, 2013. “Having made my decision as Commander-in-Chief based on what I am convinced is our national security interests, I’m also mindful that I’m the President of the world’s oldest constitutional democracy … And that’s why I’ve made a second decision: I will seek authorization for the use of force from the American people’s representatives in Congress.”

It was an unusual moment in American history: a president pausing to acknowledge that Congress’s war power was not an obstacle but an asset to a democratic system. Obama knew very well that, if he sought an authorization vote, he might lose. (If he had lost, it would, as near as I can tell, have been the first time since the Wilson administration that Congress denied a president’s request for prior authority to use force.)

As it happened, the need for a vote never arose; Russian diplomatic intervention produced a genuine settlement to the chemical-weapons problem. But flash forward to today. For the past year, the United States has been in a much wider conflict with the non-state that calls itself the Islamic State. This military operation dwarfs the proposed Syria bombing. We have put together a rickety, complex, and partly secret “alliance” with a number of seemingly incompatible players in the region, ranging from Britain and France to Turkey, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and, under cover, at least the tacit cooperation of Iran and even Syria. We are training “moderate” Syrian rebels and our troops are advising and training the Iraqi Army. The operation has spread from Iraq to Syria and perhaps now Egypt. It is taking place amidst—and arguably exacerbating—a refugee crisis that is engulfing not just the region but the Western European countries. And General Raymond Odierno, who retired last week as the Army chief of staff, said on his way out that “if we find in the next several months that we aren’t making progress, we should absolutely consider embedding some soldiers (in Iraq).”

A spreading conflict, regional instability, pressure for deepening involvement—and no end ahead that I can see. I am an authority on the Middle East to the extent Donald Trump is an expert on men’s hairstyles. We may have a clear definition of “victory” and a smart path toward it. But if I don’t know that plan, it’s really not my fault. The government hasn’t explained itself to me and the rest of the country; and for that reason, I can’t hold anybody accountable for what goes right, or wrong, in the months ahead.

There is a way that the government could explain itself; indeed, the government is required to do that by Article I of the Constitution, which assigns to Congress the power to “declare war.” It’s true that nations don’t “declare war” anymore; but the grant of power in that clause isn’t a formality, an empty box to be checked off. Read the words in context with the subsequent clauses—Congress has the power to fund or defund the military and to set the rules “for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces.”

This war is an ongoing violation of the Constitution, one of the most severe of the 21st century.In other words, the military belongs to Congress, and through them to the people. When the President wants to borrow it, he has to ask for permission and explain why.

Obviously there are exceptions; when an emergency occurs (what Madison called a “sudden attack,” but also an emergent threat to Americans or American interests abroad), the president can respond first and ask for permission later. But the “war” on the Islamic State isn’t like that at all; it was a policy decision carefully arrived at. The Islamic State is a frightening enemy; but it was not immediately menacing the U.S.

This war is an ongoing violation of the Constitution, one of the most severe of the 21st century. But it is a violation in which both parties are happy to collaborate. The administration claims it already has authority for the intervention, in the Authorization for the Use of Military Force passed in 2001, which gave the president authority to attack “nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.” That enemy was al-Qaeda; now, administration officials say, the Islamic State is (as one anonymously put it) “the true inheritor of Usama bin Laden’s legacy.” In other words, the Islamic State is the cow with the crumpled horn, and if you follow the chain back far enough, you eventually get to the House that Jack Built. That chain may be faulty or even fanciful; but this analysis at least complies with the forms.

The administration has requested specific authorization for the effort to combat the Islamic State, submitting a complex draft resolution that authorizes the president to use force against the Islamic State and “associated forces”—but that also forbids the use of U.S. ground troops and requires reauthorization after three years.

The draft is plainly aimed at preventing the war from spreading out of control—and, at least in part, at limiting the options of Obama’s successor. For this reason among others, the Republican leadership has balked at passing it, preferring something far more open ended and sweeping. Senator Marco Rubio, for example, reacted to the draft this way: “I would say that there is a pretty simple authorization he could ask for and it would read one sentence: ‘We authorize the president to defeat and destroy ISIL.’ Period.” Senator Lindsey Graham said the limitations would “harm the war effort.” Both of them imagine they may be using a future authorization, and want it to be as wide as possible. But to Obama, an over-broad resolution would be the nightmare of permanent war that he has tried to escape for the past six years.

Some Democrats, meanwhile, believe that even Obama’s language is too broad. So we have stalemate—a stalemate the administration can live with. It has its claim of authority already in place, and it’s unwilling to rock the military boat while a vote is pending on the Iran nuclear deal.

Congress always prefers to remain mum about a war until it sees whether it’s going well, but the Constitution doesn’t have a “wait for the polls” clause.The scandal in this is that almost nobody is really working to resolve the impasse. Senators Timothy Kaine of Virginia, a Democrat, and Jeff Flake of Arizona, a Republican, have submitted a draft which would provide limited authorization, but their colleagues aren’t beating down their doors to cosponsor the bill. Kaine recently told The Hill that the Senate “has hardly had more than 90 minutes of discussion about this” since the Obama draft arrived.

The administration has at least done the minimum. And if the administration isn’t pushing, it’s at least in part because this Congress has demonstrated that it will discard settled norms in foreign policy—witness the genuinely shocking attempt to sabotage the Iran deal by writing to the Iranian leadership while negotiations were still pending. Right now, that deal is the administration’s top priority.

Congress is abdicating an important role. Congress always prefers to remain mum about a war until it sees whether it’s going well, but the Constitution doesn’t have a “wait for the polls” clause.

But this war is already too wide to be proceed any further without a serious discussion of the aims and dangers of the effort. American soldiers, whether they are “advisers” or “embeds” or anything else, are at risk, and beyond that, international stability is at stake. There are institutional reasons why the two branches are content to make war-and-peace decisions in silence. But we the people don’t have to accept that. We can insist that Congress take this matter up, and we can also insist that they treat this life-and-death issue as if they were grown-ups.

Patrick Stewart Behaves Badly in Blunt Talk

In television, there is a sub-genre so overdone, so endlessly imitated, that every new entry feels burnt to a crisp on arrival: the show about a powerful man behaving very badly. Usually it requires a famous lead and a splashy setting; Starz’s new half-hour comedy Blunt Talk (debuting Saturday at 9 p.m.) has both, starring Patrick Stewart as the cable news host Walter Blunt, a man in the midst of a severe, and very public decline. Blunt Talk opens with Walter drinking and driving, nibbling on marijuana edibles, and picking up a prostitute, before scuffling with the cops who try to arrest him for solicitation. The implication seems to be that such wantonly outrageous acts make the show worth watching all by themselves, but from the beginning Stewart manfully struggles to make the show even marginally engaging.

Related Story

Without a doubt, Stewart is certainly the biggest card Blunt Talk has to play. In his long career, he’s rarely ventured into comedy, but his voice work on the Seth MacFarlane comedy American Dad piqued his interest, and Blunt Talk is produced by MacFarlane. Throughout, the show is clearly delighted with itself for getting Stewart to behave so badly—he asks to nuzzle a woman’s breasts, cheerfully ingests any drug handed to him, and out of nowhere recites Shakespearean monologues, in case the audience forgot which actor it was dealing with. It’s quite a fun performance in spite of the very thin show around it, but having Stewart play such a cartoon does not a watchable television show make.

It’s hard to tell what else Blunt Talk is really about. Yes, it’s a broad satire of cable news, with Blunt’s proclivity for troublemaking becoming a helpful boon for ratings, and the character is obviously supposed to represent many a self-important TV talking head. Blunt is married and divorced many times over, and served as a British Marine in the Falklands War, something he takes very seriously (one of the funniest recurring jokes is his sensitivity to anyone reducing the importance of the conflict). If this life experience ever helped him present an authentic take on the news, it’s clear years of celebrity have sanded that away, and Blunt is surrounded by a colorful supporting cast of TV producers who help affirm his God complex.

As satire, it isn’t particularly cutting, which is a little surprising considering that Blunt Talk was created by Jonathan Ames, whose last TV effort was the appreciably shaggy HBO comedy Bored to Death. That was also a “men behaving badly” comedy, but a much more subversive one: its characters were man-children in various stages of arrested development, playing at being private investigators as a way of staving off adulthood. Walter Blunt is chugging pills and booze as a similar act of escapism, but his misadventures are much more formulaic, and his core characterization is just a skewed version of Patrick Stewart himself: an entertaining Brit with a magical, built-in gravitas. In case you forget he’s British, he even has a butler who accompanies him everywhere, offering swigs from a flask whenever Walter gets stressed out.

Blunt Talk does pick up in quality a little bit after its bombastic pilot episode, and like Bored to Death (which also started slow), it may eventually settle into a nice groove as it fills in the details of Walter’s life and the ensemble around him. The cast includes the marvelous two-time Oscar nominee Jacki Weaver as his embattled right-hand woman and Timm Sharp as a friendly, pill-carrying enabler. Though they have little do to in early episodes, they’re both comedic forces in their own right who may find more to do as the series progresses.

Starz clearly has faith in Blunt Talk, as it’s already been renewed for another 10 episodes after this first season, but like everything else on screen, that bet is clearly being made on the back of Stewart’s star power. Fans will no doubt want to check out his admirable attempt at a comic turn, but other than that, there’s very little to hook a viewer in. It’s sadly easy to consign Blunt Talk to the giant pile of forgettable premium-cable comedies like Californication, House of Lies and Happyish that figured audiences would enjoy the vicarious thrill of male leads swearing, drinking, sleeping around, no matter how tired the premise.

Hillary Clinton's Blunt View of Social Progress

In the push for social progress, which comes first: changed hearts or changed laws?

Hillary Clinton answered this question in the course of her quasi-private meeting with activists from the Black Lives Matter movement, and she came down firmly on the side of the latter. “I don’t believe you change hearts,” Clinton told Julius Jones in an candid moment backstage after a campaign event. “I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate. You’re not going to change every heart. You’re not. But at the end of the day, we can do a whole lot to change some hearts, and change some systems, and create more opportunities for people who deserve to have them.”

The video of the encounter between the Democratic frontrunner and the activists was described as “tense,” “awkward,” a “confrontation.” All of those words make you want to click and watch, but the exchange was really just a honest human discussion about an important issue—fascinating in large measure because it seems so rare in modern presidential politics, and especially when the candidate is the famously cautious Clinton. But her response was most interesting for what it revealed about her view of social progress movements. Jones was pressing Clinton to acknowledge her culpability in the tough-on-crime legislation that passed during her husband’s administration, which even President Clinton has conceded made the problem of mass incarceration “worse.” Jones wanted to know what had changed “in your heart” that proved she was on their side in the push for racial justice.

Clinton had little interest in the touchy-feeling notion of hearts and minds—“lip service,” she called it at one point—and instead wanted to get down to brass tacks: What is it that you want to achieve? Give me a policy agenda to “sell.” In the language of a politician, she wanted to hear their “ask”—a specific, tangible request that is made hundreds of times a day in meetings between officials and advocates on Capitol Hill or Cabinet department offices. Clinton has spoken in detail about enacting criminal-justice reform, but that platform did not get discussed in the video. The response seemed to reveal Clinton’s inner wonk, a preference for the nitty-gritty bottom line of policy changes over soaring political rhetoric that has led her campaign to place in more intimate settings with voters rather than large speeches.

And at least on the surface, it highlights a difference between her and President Obama, a man who rode into office on the strength of his ability to inspire voters with lofty rhetoric and an appeal to their hopes and dreams. Yet one major lesson of his presidency—as evidenced by the very rise of the Black Lives Matter movement six years into her tenure—is that it has done little to transcend the deep-seeded racial tensions in the U.S. In key areas like healthcare and climate policy, Obama has succeeded in enacting, by legislation or through regulations, significant changes even as the electorate remains deeply polarized on those issues. On gay rights, he has presided over an era marked by a rapid shift in both concrete policy (the legalization of gay marriage by the courts and the repeal of the ban on gays serving openly in the military by Congress) and a corresponding change in the “hearts and minds,” according to polls showing majority support for same-sex marriage. And then there’s gun control, where Obama has failed to win policy changes despite a wave of mass shootings, to the point where he has suggested that Congress won’t act unless the public gets more engaged.

Activists, of course, have targeted Obama on all of these issues over the course of his presidency, accusing him of not being aggressive enough in his pursuit of change. On immigration, reformers criticized him for barely pushing the issue in his first term only to come around in his second. And on race, he’s only recently begun to speak in depth on the topic, most notably during his eulogy for the Reverend Clementa Pinckney in Charleston earlier this summer. In television interviews since the Clinton meeting, Jones said the movement would continue to hold Obama “accountable” along with the many candidates to replace him.

“I don’t believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate.”As for Clinton’s message, Jones and his colleague Daunasia Yancey had a mixed response. Appearing on MSNBC, Jones said the encounter was “good.” “It moves the conversation about race in the United States to a new and deeper level,” he said. He also said Clinton was “ducking the question” of her culpability in the ’90-era crime measures, and Yancey said her focus on policy “wasn’t sufficient for us.”

When I asked a few activists from the immigration-reform movement, who have also confronted Clinton and other political leaders over the years, they had an even more critical reaction to her message. “She totally doesn’t get it,” said Cristina Jimenez, managing director of United We Dream. “I felt very offended by her remarks.” Jimenez argued that personal storytelling and “changing hearts and minds” had been crucial in the push to spotlight the cause of Dreamers (immigrants brought illegally to the U.S. as children) and to ultimately gain protection from deportation through Obama’s executive action in 2012. Even though the movement started more than a decade ago, she said, “we weren’t able to achieve a policy change until 2012.”

Monica Reyes, the 24-year-old co-founder of Dream Iowa, said she had the opposite view of social progress as Clinton. “You need to change the culture before you can change laws,” she told me. Clinton’s attitude “doesn’t speak to the grassroots community,” Reyes said. “The grassroots is about people.” Another Dreamer activist who has confronted Clinton over immigration policy, Cesar Vargas, criticized Clinton for being “insensitive.” “She’s not understanding the people who are electing her,” Vargas told me. Achieving progress in women’s rights, civil rights, and other movements in history, he argued, “was about changing the hearts and minds.”

Who is right? “There’s no question that hearts can change, and it’s often social movements that create it,” the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin told me. She pointed in particular to the gay-rights movement, where the experience in people coming out to their friends and family and the increased portrayal of gay couples in popular culture preceded the passage of laws legalizing first civil unions and then marriage. “People felt a ‘fellow feeling’ with gays and saw not as others in the same way,” she said, quoting a famous line from Teddy Roosevelt. Similarly, Goodwin said, it was the national broadcasts of white brutality toward blacks in the 1950s and 60s that engendered sympathy among whites for the civil-rights movement and led to the passage of landmark legislation under Lyndon Johnson.

Goodwin said presidents from Lincoln (“Public sentiment is everything”) to LBJ understood the need to mobilize broad support for policy changes. But she noted that elsewhere in her conversation with the Black Lives Matter activists, Clinton seemed to acknowledge the importance of raising public consciousness around an issue like race relations, even as she pressed them to have an agenda “ready to go” as did activists in the earlier generation of civil-rights leaders.

On that point, members of the movement appeared to take note. By Friday, a group of protesters had launched a website called Campaign Zero that featured a set of 10 proposals for policing reform, including an end to “broken windows” policing, increased training, expanded use of body cameras, and an end to the kind of “for-profit policing” that the Justice Department found in Ferguson. It also included a chart of where several presidential candidates in both parties, including Clinton, stood on the ideas. It might not settle the hearts-versus-laws question at the heart of her debate with the Black Lives Matter activists, but at least it gives both sides a place to start.

August 21, 2015

U.S. Stocks Take a Dive

The U.S. stock market is having a terrible day as a sell-off in global markets continues amid worries about China’s manufacturing numbers. The Dow Jones industrial average fell more than 500 points on Friday. The S&P and the Nasdaq both saw big losses as well—both indexes were down more than 3 percent.

There are plenty of reasons investors are worried. The sell-off has been attributed to weak manufacturing data from China. Activity in Chinese factories fell to a six-year low, another sign the world’s second-largest economy is slowing. Markets are also on edge about the whether the U.S. Federal Reserve will increase interest rates in September. And the oil glut continues, with the price per barrel slumping to $40 today.

All three U.S. indexes had their worst week since 2011, with the Dow now in “correction” territory. Investors have been speculating about a correction—a 10 percent drop from the peak—as it has been fours years since the markets last saw one.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower