Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 362

August 21, 2015

Clarice Lispector’s Magical Prose

Clarice Lispector was a woman plagued by “the hellish grandeur of life.” Throughout her career the Brazilian author and journalist showed a fascination for the mundane, as well as a desperation to quiet her mind and achieve a semblance of normalcy.

More From Quartz This Is What the American Road Trip Looks Like if You’re an Obsessive Book Nerd One of Literature’s Biggest, Canuck-Friendliest Prizes has Shut Out the Great White North Should Shakespeare be Taught in Africa’s Classrooms?Lispector died of cancer in 1977 without ever realizing that goal, leaving behind a body of bizarre, challenging, and dazzling writing that has become a part of the literary canon within Brazil and has built a small but fierce cult following among the literary cognoscenti elsewhere. Despite this acclaim, however, the enigmatic and statuesque writer remains relatively unknown internationally.

The Complete Stories, released August 25 by New Directions and translated into English by Katrina Dodson, gives readers access to all 86 of her short stories in one place for the first time in any language, and has been greeted with a flurry of belated and enthusiastic appreciation.

With this new volume, the woman known in some circles simply as “Clarice” has another chance at entering the mainstream. But back home in Brazil, Lispector needs no introduction. In the decades following her death, her popularity has exploded, and her face has become iconic: She has appeared on stamps and is quoted constantly on inspirational posters. A Twitter account that posts quotes by her has a million followers. The Brazilian rap star Filipe Ret has her face tattooed prominently on his bicep.

She’s popular among critics internationally as well: Routinely compared to Jorge Luis Borges, Vladimir Nabokov, and James Joyce, Lispector is hailed by many literati as Brazil’s greatest contemporary writer. Benjamin Moser, her biographer and champion in the English-speaking world, who’s also the editor of the new collection, is often quoted as saying she’s the most important Jewish writer in the world since Kafka.

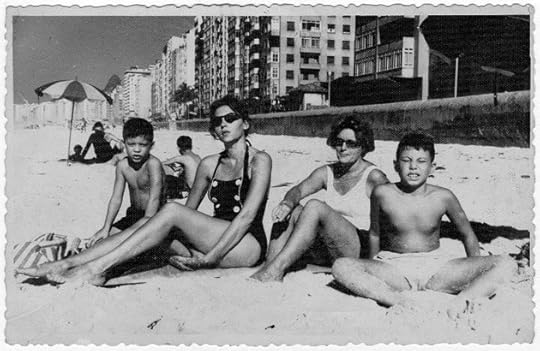

Clarice Lispector, left, with her sons (New Directions)

Clarice Lispector, left, with her sons (New Directions) Part of Lispector’s aura of intrigue comes from her beauty, glamour, and strange public persona. Of Eastern European-Jewish origin, she was transplanted to Brazil as a small child.

In his biography of Lispector, Why this World, Moser paints her as a person full of contradictions. He writes:

She herself once wrote, “I am so mysterious that I don’t even understand myself.”

“My mystery,” she insisted elsewhere, “is that I have no mystery.”

Still, he adds, “To general bemusement, she insisted that she was a simple housewife, and those who arrived expecting to encounter a Sphinx just as often found a Jewish mother offering them cake and Coca-Cola.”

Lispector was in fact a housewife (though hardly a simple one). For 16 years she was married to a Brazilian diplomat, with whom she had two sons, and she never considered herself a professional writer. (Despite that, she wrote nine novels along with her 80-plus short stories, and worked as a fashion journalist.)

Her personal style added to her mystique: Writing about her in 2005, Gregory Rabassa said, “I was flabbergasted to meet that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.”

It would be unfair to think Lispector’s association with beauty and fashion matter only because she is a female writer. In her work, they function as a kind of intentional opaqueness. As Stephanie LaCava writes for the Los Angeles Review of Books:

Throughout her work, as Moser notes in his biography, there are moments when makeup and beauty figure as the real, the solid, in the category of knowable. These seeming superficialities are actually conduits or tools, masking—protecting—the unknowable soul; they are links to sanity.

In her only television interview, Lispector is visibly uncomfortable, nervously smoking, giving the sense that her famous air of glamour is a kind of armor, barely concealing underlying anxiety.

In Brazil, Lispector’s work is required reading on the national university entrance exams called Vestibular, similar to the French baccalauréat. So why hasn’t she caught on in the rest of the world? Moser says the answer lies in the quality of previous translations, which he considers not up to snuff. He’s spent the last 12 years trying to revive interest in her, leading efforts to have her works re-translated. From 2011 to 2012 he edited or translated new versions of five of her novels (blurbed by the likes of Jonathan Franzen, Orhan Pamuk, and Colm Tóibín), and he’s currently working on the last four.

The difficulty of translating Lispector is partly due to the fact that even in her native Portuguese, she often created fake idioms and distorted normal ones. Her translator, Katrina Dodson, gives an example from the story “Silence,” in which Lispector uses the phrase “ponto do trigo,” or “point of wheat,” in a sentence she translates as “I never thought that the world and I would reach this point of wheat.”

Lispector’s characters struggle deeply with seeing madness in the mundane, which threatens to consume them.“That sounds as if it’s a known expression but [it] isn’t at all,” Dodson writes in an email. “We must have asked at least six Brazilians what it meant and no one could say.” She writes in the translator’s note that appears in the new collection, “These unexpected choices often make you do a double-take or blur your reading even if you don’t stumble.”

Lispector’s characters struggle deeply with seeing madness in the mundane, which threatens to consume them. In her story “Love,” an otherwise perfectly sane character is seized with emotion upon encountering a blind man chewing gum. “She had pacified life so well, taken such care for it not to explode,” writes Lispector. Yet one look “had plunged the world into dark voraciousness.”

In her last novel, The Hour of the Star, the narrator wonders, “Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?”

The blurred lines in Lispector’s language are reflected in the themes in her work, in which she strives to temper the frisson of everyday life. As LaCava writes:

Lispector’s work often explores the specific domestic conventions to which women are expected to adhere—and not because, as one might expect, she necessarily wishes to destroy them. In fact, Lispector seems to wish she could be one of the happy housewives satisfied by days occupied with decorative arrangements. Except, she is plagued by knowledge and a mystic talent for words.

Mistress America Is a Hilarious Portrayal of Generational Malaise

In the rapidly evolving millennial age, it’s good to know some life experiences are still universal, at least according to Noah Baumbach’s energetic new comedy Mistress America. It opens on the college freshman Tracy Fishko’s (Lola Kirke) first day at Barnard, and the first few minutes chart her stilted flirtation with another new student, her efforts to get accepted by the snooty literary society, and an awkward cafeteria dinner she eats alone, while pondering her lonely new adult life. Mistress America is a film about growing up, feeling in flux, and learning to take risks, but it’s also about the other side of that life arc, as Tracy befriends a 30-year-old named Brooke (Greta Gerwig) who’s crashing into the brick wall of safer, more formulaic adulthood.

Related Story

While We're Young Is Noah Baumbach's 'Plottiest' Movie Yet

Baumbach’s previous collaboration with Gerwig, Frances Ha, was a study in 20-something malaise, an energetic comedy about a young woman struggling to figure out her future without losing her enthusiasm for life. Gerwig co-wrote that film and this one, but Brooke is at best a distant cousin of Frances, a seemingly more accomplished woman about town who lives in a commercial loft, teaches spinning classes, is photographed at fancy parties, and has dreams of opening a restaurant. Her father is marrying Tracy’s mother, so Brooke happily takes the freshman under her wing and bathes in her young charge’s idolizing gaze. But Brooke’s grip on success is quickly revealed to be pretty tenuous, and despite many a witty line, Mistress America succeeds much more as a gentle and sad look at two different stages of growing up.

Tracy is quiet but thoughtful, played by Kirke as outwardly seeking approval from those around her, but nursing insight beyond her years. From the minute Brooke enters her life, it’s obvious to the audience that she’s furiously trying to keep her life together, but Kirke slowly reveals how Tracy realizes this, but is still drawn to her future step-sister’s incredible verve. Brooke is a college student’s vision of cosmopolitan adulthood, buzzing from gallery openings to late-night parties, seemingly knowing everyone who’s anyone, and pursuing all kinds of exciting schemes and ventures.

Brooke is a college student’s vision of cosmopolitan adulthood, buzzing from gallery openings to late-night parties, seemingly knowing everyone who’s anyone.But she’s also facing the truth that most people tend to grow up, and find at least a degree of stability in the process. She spends much of the first half of the film ranting about a former friend who stole both a business idea and former boyfriend from her; Mistress America’s delightful third act revolves around an impromptu trip to their Greenwich, Connecticut home, where Brooke is received as an unwelcome, if entertaining, Ghost of Christmas Past whom everyone present can compare themselves favorably to.

Baumbach’s last film, While We’re Young, was a more conventional take on similar issues, focusing on a couple in their early 40s (played by Ben Stiller and Naomi Watts) struggling to grow up as their friends settle down and have babies. With a denser plot and more sculpted punchlines, it played like a good Woody Allen movie. Mistress America is a far more energetic ride, lurching from scene to disconnected scene without too much fear of coherence, and cramming in a year’s worth of emotional development into a timeline that only spans a few weeks. It’s a more jarring experience as a result, but like Frances Ha, very much worth rolling with. The emotional throughline is what’s pivotal—though Brooke’s screwball ramblings provide the laughs, it’s her bond with Tracy (first superficial, then troublesome, but finally familial) that lingers.

Brooke may be something of a ridiculous flake, but Baumbach and Gerwig have a firm grasp on how real her connections to others are. Tracy knows that her restaurant idea is likely doomed to failure, but also realizes that Brooke needs to think otherwise just to keep propelling her way forward. It’s easy to make a comedy about flawed people, but Baumbach and Gerwig have done something harder—finding emotional truth in those flaws. The difference between a good screwball comedy and a great one is that you care about the screwballs, and in that sense, Mistress America is great indeed.

Mistress America is a Hilarious Portrayal of Generational Malaise

In the rapidly evolving millennial age, it’s good to know some life experiences are still universal, at least according to Noah Baumbach’s energetic new comedy Mistress America. It opens on the college freshman Tracy Fishko’s (Lola Kirke) first day at Barnard, and the first few minutes chart her stilted flirtation with another new student, her efforts to get accepted by the snooty literary society, and an awkward cafeteria dinner she eats alone, while pondering her lonely new adult life. Mistress America is a film about growing up, feeling in flux, and learning to take risks, but it’s also about the other side of that life arc, as Tracy befriends a 30-year-old named Brooke (Greta Gerwig) who’s crashing into the brick wall of safer, more formulaic adulthood.

Related Story

While We're Young Is Noah Baumbach's 'Plottiest' Movie Yet

Baumbach’s previous collaboration with Gerwig, Frances Ha, was a study in 20-something malaise, an energetic comedy about a young woman struggling to figure out her future without losing her enthusiasm for life. Gerwig co-wrote that film and this one, but Brooke is at best a distant cousin of Frances, a seemingly more accomplished woman about town who lives in a commercial loft, teaches spinning classes, is photographed at fancy parties, and has dreams of opening a restaurant. Her father is marrying Tracy’s mother, so Brooke happily takes the freshman under her wing and bathes in her young charge’s idolizing gaze. But Brooke’s grip on success is quickly revealed to be pretty tenuous, and despite many a witty line, Mistress America succeeds much more as a gentle and sad look at two different stages of growing up.

Tracy is quiet but thoughtful, played by Kirke as outwardly seeking approval from those around her, but nursing insight beyond her years. From the minute Brooke enters her life, it’s obvious to the audience that she’s furiously trying to keep her life together, but Kirke slowly reveals how Tracy realizes this, but is still drawn to her future step-sister’s incredible verve. Brooke is a college student’s vision of cosmopolitan adulthood, buzzing from gallery openings to late-night parties, seemingly knowing everyone who’s anyone, and pursuing all kinds of exciting schemes and ventures.

Brooke is a college student’s vision of cosmopolitan adulthood, buzzing from gallery openings to late-night parties, seemingly knowing everyone who’s anyone.But she’s also facing the truth that most people tend to grow up, and find at least a degree of stability in the process. She spends much of the first half of the film ranting about a former friend who stole both a business idea and former boyfriend from her; Mistress America’s delightful third act revolves around an impromptu trip to their Greenwich, Connecticut home, where Brooke is received as an unwelcome, if entertaining, Ghost of Christmas Past whom everyone present can compare themselves favorably to.

Baumbach’s last film, While We’re Young, was a more conventional take on similar issues, focusing on a couple in their early 40s (played by Ben Stiller and Naomi Watts) struggling to grow up as their friends settle down and have babies. With a denser plot and more sculpted punchlines, it played like a good Woody Allen movie. Mistress America is a far more energetic ride, lurching from scene to disconnected scene without too much fear of coherence, and cramming in a year’s worth of emotional development into a timeline that only spans a few weeks. It’s a more jarring experience as a result, but like Frances Ha, very much worth rolling with. The emotional throughline is what’s pivotal—though Brooke’s screwball ramblings provide the laughs, it’s her bond with Tracy (first superficial, then troublesome, but finally familial) that lingers.

Brooke may be something of a ridiculous flake, but Baumbach and Gerwig have a firm grasp on how real her connections to others are. Tracy knows that her restaurant idea is likely doomed to failure, but also realizes that Brooke needs to think otherwise just to keep propelling her way forward. It’s easy to make a comedy about flawed people, but Baumbach and Gerwig have done something harder—finding emotional truth in those flaws. The difference between a good screwball comedy and a great one is that you care about the screwballs, and in that sense, Mistress America is great indeed.

What Does It Take to Become a U.S. Army Ranger?

Until this week, there was one very important requirement for becoming an Army Ranger: You had to be a man.

On Friday, Captain Kristen Griest and First Lieutenant Shaye Haver became the first women to earn the coveted black-and-yellow tab when they graduated from the U.S. Army Ranger School alongside 94 male soldiers.

Griest and Haver’s graduation is the latest in a series of firsts for women in the U.S. military. In January 2013, the Defense Department opened to women thousands of military jobs that were previously only available to men. Six months later, the Pentagon announced it would allow women in front-line combat roles by 2016. And two days ago, the Navy’s top admiral said “there is no reason” why women cannot train to become Navy SEALs.

Critics of allowing women into Ranger training have said the Army is lowering its standards. But Army spokespeople have said repeatedly that Griest and Haver were subject to the same requirements as their male peers.

“No woman that I know wanted to go to Ranger School if they change the standards, because then it degrades what the tab means,” Griest told reporters Thursday.

So, what does the tab mean? Ranger School has been described as the most physically and mentally demanding program in the Army. Students are required to train for grueling combat operations on minimal food and sleep. Just 45 percent will successfully complete the nine-week program.

Here’s the advice the military gives soldiers who are thinking about attending:

The most important pre-training exercise to do prior to Ranger school is walking fast in your boots with 50 pounds of weight on your back. You will do this everyday you are at Ranger School. Running at least 5 miles, 3-4 times a week and swimming in uniform 2-3 times a week is recommended as well. Pack on 5-10 pounds of body weight prior to going so you have a little to lose when you are consuming fewer calories a day.

Before they even get accepted to Ranger school, soldiers should be able to do at least six pull-ups, 49 pushups in two minutes, and 59 sit-ups in two minutes. (By the time they graduate, students can do double that.) They must be capable of completing a 5-mile run in 40 minutes and a 16-mile hike with 65 pounds of weight on their backs in just over five hours.

Once students arrive at Ranger School, they go through three phases, according to the U.S. Army’s website: crawl, walk, and run. The crawl phase tests students’ physical and mental skills. Students train in a mountain landscape during the walk phase. “The rugged terrain, hunger, and sleep deprivation are the biggest causes of emotional stress that students encounter,” the Army explains. The final phase takes place in a swamp environment, where students train to operate “under conditions of extreme mental and physical stress.” Students spend long hours walking with heavy gear, sleeping outside, and eating one to two fewer meals per day than normal. Many students lose 20 to 30 pounds over the course of the program.

“But the school teaches the Ranger he can overcome insurmountable challenges while under simulated combat conditions,” the Army says. “And of course, he can wear the well-deserved Ranger Tab on his shoulder.”

Now, so can she.

Jonathan Franzen and Those ‘Iraqi War Orphans’

During a 2010 interview with The Telegraph—one he gave during the publicity tour for his then-new book, Freedom—the author Jonathan Franzen mentioned, off-handedly, that he once considered adopting “some Iraqi orphans.” In order to help “his creative process.”

From that interview:

While struggling to write Freedom, he got it into his head that becoming a father might actually help the creative process. “I was seriously thinking about adopting some Iraqi war orphans.” He mentioned this plan over a drink with his editor at The New Yorker, who was horrified. “He took two toothpicks from the bar and made the sign of the cross and waved it slowly in front of me as if warding off an evil spirit.” Franzen laughs.

“And he sensibly pointed out that there are more people in the world who can make good parents than can write good books.”

Some Iraqi war orphans, as a whim: ooof. The notion of taking human children into one’s family for ostensibly literary purposes: ooof again.

This was not a good moment for Franzen. It suggested that Franzen, so adept at the creation of fictional people in his work, is much less adept at dealing with actual people. It also seemed to ratify some of the longest-standing and most legitimate complaints about writers, and artists, in general: that they sometimes use people—human people, people who are much more than characters in books—for their own creative ends. That they don’t just forget the categorical imperative, but instead consider themselves, and their work, to be somehow above it.

It was a small moment, though, and one that might have been buried under the many adulations Freedom received, not to mention under the breathless declarations that Franzen ranks among the cadre of “great American novelists.” It’s a moment, however, that has now been resurrected as part of the publicity tour for Franzen’s new book, Purity. An interview he gave to The Guardian, released in condensed form today and set to be published in full over the weekend, begins with Franzen’s orphan consideration. “Franzen said he was in his late 40s at the time with a thriving career and a good relationship,” the article explains, “but he felt angry with the younger generation.”

Franzen himself added, “Oh, it was insane, the idea that Kathy [his partner] and I were going to adopt an Iraqi war orphan. The whole idea lasted maybe six weeks.”

He then elaborated, however:

One of the things that had put me in mind of adoption was a sense of alienation from the younger generation. They seemed politically not the way they should be as young people. I thought people were supposed to be idealistic and angry. And they seemed kind of cynical and not very angry. At least not in any way that was accessible to me.

In other words, Franzen is making clear, he considered adoption not on the grounds of selflessness or generosity or a sense of family or love or humanity, but on artistic ones. He wanted to understand “the younger generation,” ostensibly to write young characters with better accuracy. He figured one way to do that would be to adopt a human person. He did that figuring for “maybe six weeks.”

To be fair to Franzen, if adoption was something he and his partner really were considering, it’s likely they were not so glib in their own discussions of the possibility. Hindsight, not to mention book-tour publicity interviews, have a way of condensing real emotions, real decisions, into the blitheness of anecdote. Still, the way things are presented here—the way Franzen himself is presenting them—means that what comes across is not nuance, but instead flipness and entitlement. He considered bringing a living, breathing, complicated human into his home and his family … in order to understand, and perhaps diffuse, his “alienation from the younger generation.”

Sure, he didn’t end up adopting a child. It never seems to have occurred to him, though, that the problem wasn’t just the adoption itself—it was the grounds under which he considered doing the adopting in the first place.

From Whitewater to Benghazi: A Clinton Scandal Primer

It's been six months since Hillary Clinton’s controversial private email server was discovered, and her camp is still trying to handle the fallout.

On Wednesday, her campaign conceded that some emails hosted on the server contained material that was classified retroactively. Clinton has long said that none of her emails, either sent and received, contained information that was classified at the time they were sent.

A new Reuters report disputes that claim. The report found that the “Classified” stamps on a few publicly released emails show that they would have been automatically considered classified, even before they received that formal designation, in accordance with government regulations. In some of those emails, information exchanged between U.S. officials and their foreign counterparts in confidence would be “presumed” classified, according to the report.

The email saga began with Representative Trey Gowdy’s select committee on Benghazi. Those investigations led to the public revelation that the former secretary of state had maintained a private email server, and produced a court order to release the emails in 30-day tranches.

Federal investigators told members of Congress in a letter that two highly classified emails had been found on Clinton’s personal email system. In response, Clinton’s attorney turned over the server to the FBI, along with thumb drives containing thousands of emails that had previously been turned over to the State Department, The Washington Post reports.

Related Story

During a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit on Thursday, a federal judge ordered the State Department to ask the FBI for additional emails that may be found in Clinton’s private server.

In addition to the possible legal ramifications, the investigation has turned up some interesting facts about how much effort Clinton put into the running and upkeep of the server. The server itself had been purchased for her unsuccessful 2008 run for president. Initially, it was run by a former Senate aide, who was then hired by the State Department. Later, amid concerns about reliability, she hired Platte River, the Denver company now subject to FBI questions.

The email controversy is quickly turning into a classic Clinton scandal. Her use of a private email account became known during the course of an investigation into the 2012 deaths of U.S. personnel in Benghazi, Libya. Thus far, the investigations have found no wrongdoing on her part with respect to Benghazi, but Clinton’s private-email use and now the referral concerning classified information have become stories unto themselves. This is something of a pattern with the Clinton family, which has been in the public spotlight since Bill Clinton’s first run for office, in 1974: Something that appears potentially scandalous on its face turns out to be innocuous, but an investigation into it reveals other questionable behavior. The classic case is Whitewater, a failed real-estate investment Bill and Hillary Clinton made in 1978. While no inquiry ever produced evidence of wrongdoing, investigations ultimately led to President Clinton’s impeachment for perjury and obstruction of justice.

With Hillary Clinton leading the field for the Democratic nomination for president, every Clinton scandal—from Whitewater to Clinton’s State Department emails—will be under the microscope. (No other American politicians—even ones as corrupt as Richard Nixon, or as hated by partisans as George W. Bush—have fostered the creation of a permanent multimillion-dollar cottage industry devoted to attacking them.) Keeping track of each controversy, where it came from, and how serious it is, is no small task, so here’s a primer. We’ll update it as new information emerges.

Clinton’s State Department Emails Secretary of State Hillary Clinton checks her phone on board a plane from Malta to Tripoli, Libya. (Kevin Lamarque / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? Setting aside the question of the Clintons’ private email server, what’s in the emails that Clinton did turn over to State? While some of the emails related to Benghazi have been released, there are plenty of others covered by public-records laws that haven’t.

When? 2009-2013

How serious is it? Moderately. The fact that Clinton sorted her own emails would seem to offer some inoculation. But a federal judge’s ruling that the State Department must release new batches of cleared emails every 30 days means there will be a monthly cycle of reporters digging into the cache—bad news for a candidate who’d rather put it behind her. Plus there have already been some strange revelations, like the fact former Clinton confidant Sidney Blumenthal was advising her on Libya and a wide range of matters, and may have been the source of initial, misleading ideas the Benghazi attacks were spontaneous mob violence. Clinton’s campaign has since said that the emails contained material that was made classified retroactively. But a Reuters report found that some information, sent and received, was “presumed” classified, according to U.S. regulations.

Benghazi A man celebrates as the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi burns on September 11, 2012. (Esam Al-Fetori / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? On September 11, 2012, attackers overran a U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, killing Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans. Since then, Republicans have charged that Hillary Clinton failed to adequately protect U.S. installations or that she attempted to spin the attacks as spontaneous when she knew they were planned terrorist operations.

When? September 11, 2012-present

How serious is it? Benghazi has gradually turned into a classic “it’s not the crime, it’s the coverup” scenario. Only the fringes argue, at this point, that Clinton deliberately withheld aid. A House committee continues to investigate the killings and aftermath. But it was through the Benghazi investigations that Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server became public—a controversy that remains potent.

The Clintons’ Private Email Server Jim Young / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

What? During the course of the Benghazi investigation, New York Times reporter Michael Schmidt learned Clinton had used a personal email account while secretary of state. It turned out she had also been using a private server, located at a house in New York. The result was that Clinton and her staff decided which emails to turn over to the State Department as public records and which to withhold; they say they then destroyed the ones they had designated as personal.

When? 2009-2013, during Clinton’s term as secretary.

Who? Hillary Clinton; Bill Clinton; top aides including Huma Abedin

How serious is it? The rules governing use of personal emails are murky, and Clinton aides insist she followed all rules. There’s no evidence at this point that proves otherwise. The greater political problem for Clinton is it raises questions about how she selected the emails she turned over and what was in the ones she deleted. Are those emails truly deleted? Could the server have been hacked? Some of the emails she received on her personal account are marked sensitive. Plus there’s a entirely different set of questions about Clinton’s State Department emails. The FBI is investigating the security of the server as well as the safety of a thumb drive belonging to her lawyer that contains copies of her emails.

Sidney Blumenthal Blumenthal takes a lunch break while being deposed in private session of the House Select Committee on Benghazi. (Jonathan Ernst / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? A former journalist, Blumenthal was a top aide in the second term of the Bill Clinton administration and helped on messaging during the bad old days. He served as an adviser to Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, and when she took over the State Department, she sought to hire Blumenthal. Obama aides, apparently still smarting over his role in attacks on candidate Obama, refused the request, so Clinton just sought out his counsel informally. At the same time, Blumenthal was drawing a check from the Clinton Foundation.

When? 2009-2013

How serious is it? Some of the damage is already done. Blumenthal was apparently the source of the idea that the Benghazi attacks were spontaneous, a notion that proved incorrect and provided a political bludgeon against Clinton and Obama. He also advised the secretary on a wide range of other issues, from Northern Ireland to China. But emails released so far show even Clinton’s top foreign-policy guru, Jake Sullivan, rejecting Blumenthal’s analysis, raising questions about her judgment in trusting him.

The Speeches Keith Bedford / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

What? Since Bill Clinton left the White House in 2001, both Clintons have made millions of dollars for giving speeches.

When? 2001-present

Who? Hillary Clinton; Bill Clinton; Chelsea Clinton

How serious is it? This might be the most potent of all the current Clinton scandals. For the couple, who left the White House up to their ears in legal debt, lucrative speeches—mostly by the former president—proved to be an effective way of rebuilding wealth. They have also been an effective magnet for prying questions. Where did Bill, Hillary, and Chelsea Clinton speak? How did they decide how much to charge? What did they say? How did they decide which speeches would be given on behalf of the Clinton Foundation, with fees going to the charity, and which would be treated as personal income? Are there cases of conflicts of interest or quid pro quos—for example, speaking gigs for Bill Clinton on behalf of clients who had business before the State Department?

The Clinton Foundation A brooch for sale at the Clinton Museum Store in Little Rock, Arkansas (Lucy Nicholson / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? Bill Clinton’s foundation was actually established in 1997, but after leaving the White House it became his primary vehicle for … well, everything. With projects ranging from public health to elephant-poaching protection and small-business assistance to child development, the foundation is a huge global player with several prominent offshoots. In 2013, following Hillary Clinton’s departure as secretary of State, it was renamed the Bill, Hillary, and Chelsea Clinton Foundation.

When? 1997-present

Who? Bill Clinton; Hillary Clinton; Chelsea Clinton, etc.

How serious is it? If the Clinton Foundation’s strength is President Clinton’s endless intellectual omnivorousness, its weakness is the distractibility and lack of interest in detail that sometimes come with it. On a philanthropic level, the foundation gets decent ratings from outside review groups, though critics charge that it’s too diffuse to do much good, that the money has not always achieved what it was intended to, and that in some cases the money doesn’t seem to have achieved its intended purpose. The foundation made errors in its tax returns it has to correct. Overall, however, the essential questions about the Clinton Foundation come down to two, related issues. The first is the seemingly unavoidable conflicts of interest: How did the Clintons’ charitable work intersect with their for-profit speeches? How did their speeches intersect with Hillary Clinton’s work at the State Department? Were there quid-pro-quos involving U.S. policy? The second, connected question is about disclosure. When Clinton became secretary, she agreed that the foundation would make certain disclosures, which it’s now clear it didn’t always do. And the looming questions about Clinton’s State Department emails make it harder to answer those questions.

The Bad Old Days Supporter Dick Furinash holds up cardboard cut-outs of Bill and Hillary Clinton. (Jim Young / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What is it? Since the Clintons have a long history of controversies, there are any number of past scandals that continue to float around, especially in conservative media: Whitewater. Troopergate. Paula Jones. Monica Lewinsky. Vince Foster.

When? 1975-2001

Who? Bill Clinton; Hillary Clinton; a brigade of supporting characters

How serious is it? Not terribly. Some are wholly spurious (Foster). Others (Lewinsky, Whitewater) have been so exhaustively investigated it’s hard to imagine them doing much further damage to Hillary Clinton’s standing. In fact, the Lewinsky scandal famously boosted her public approval ratings. But that doesn’t mean you won’t hear plenty about them.

A Conversation About Black Lives Matter and Bernie Sanders

In “A Tough Weekend for Black Lives Matter,” I wrote about the members of the social justice movement who interrupted a Bernie Sanders rally in Seattle, drawing some boos from the crowd and ultimately causing the cancellation of the presidential candidate’s speech. My article posited that although police reform is a just and vital cause that ought to be pursued with urgency, the activists’ treatment of Sanders was a strategic mistake, especially given that his long-shot campaign aligns much better with the demands of Black Lives Matter than Hillary Clinton’s ever will.

A reader, Martha Tesema, wrote a particularly thoughtful dissent. “As a young, black female who lives in Seattle,” she began, “I wanted to share my perspective because it’s likely that you haven’t heard directly from a point of view like mine before.” We agreed that journalists are, as she put it, “gatekeepers of different perspectives,” and she consented to an email interview in which we would attempt to set forth her perspective on Black Lives Matter and flesh out why it is that the two of us disagree. She supports the activist movement but is not affiliated with it herself.

This version has been lightly edited for clarity.

Conor Friedersdorf: Martha, you wrote that far from thinking that Black Lives Matter had a tough weekend, you were celebrating its action in Seattle. What’s your view of that day?

Martha Tesema: Thanks for asking about my perspective. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to attend the protest. But I’ve been celebrating what Marissa Janae Johnson and Mara Jacqueline Willaford did. As a black woman in this city, I think it was incredibly brave.

It disrupted the status-quo and kick-started needed conversations that I was desperate to have with strangers, friends, and co-workers. People have this idea of Seattle as a utopia. And yes, it’s a beautiful city on many levels. But despite how liberal and progressive Seattle claims to be, it’s clear from the reactions to the protest that there’re still many who are blind to a variety of issues locally and nationally.

I'm grateful for Marissa and Mara. I’m glad they pushed some buttons.

Friedersdorf: We agree that the issues raised by Black Lives Matter are important, and I’m eager to hear more about your experience of Seattle. But first I want to ask about something that one of the protesters said in response to boos from the crowd. “I was going to tell Bernie how racist this city is, filled with its progressives,” she said, “but you did it for me.” When you wrote, “it’s clear from the reactions to the protest that there’s still many who are blind to a variety of issues locally and nationally,” were you referring to the same moment? I have no doubt that many in Seattle are unaware of flaws in the way that their city is policed and other unjust policies that disproportionately burden black people. At the same time, I don’t think the boos from the crowd illustrate that its members are racist, and I suspect some people upset about the BLM takeover aren’t blind to the movement’s issues.

When I try to put myself in the place of some of the people booing, I imagine a woman who rearranged her schedule, hired a babysitter, and traveled an hour to the Westlake neighborhood to see a candidate she regards as a potential savior for the country. This might be the only opportunity she ever has to see him speak in person. So she stays on her feet in a crowd of people who think life will be better for the working class and the poor if only they can elect this man––and then, when it’s time for him to speak, to deliver a social-democratic message that no one else of prominence is articulating, he is upstaged. The candidate whose voice they perceive as being constantly disadvantaged by a corporate-controlled media and the influx of special-interest money in politics is silenced again. There’s no doubt in my mind that they’d have booed anyone who did that. Maybe this hypothetical woman believes Sanders is the only one who will help her husband on disability, or avert catastrophic climate change, or raise the wage that leaves her just short of rent. And now some unknown person is thwarting him. The upset almost anyone would feel in that situation strikes me as the most likely explanation for most of the boos.

Then again, you live in Seattle. And you saw the aftermath with a local’s eye.

Why did you think the response to the protest revealed something particular to Black Lives Matter and its issues? Do you think the Sanders supporters at the rally had any legitimate complaint, even if you think that the protest was, on balance, a good thing?

Tesema: You write, “I don’t think the boos from the crowd illustrate that its members were racist.” When people are silenced––when a “progressive, liberal” audience attempts to silence a marginalized people––they are not acting in solidarity.

And I am not only talking about the Westlake event, but the broader political conversation happening in this election. No matter how down people say they are with the cause, when they act like being slightly inconvenienced is more important than the lives of people of color, that suggests they probably never truly supported the movement. Marissa, Mara, and allies were not invited. They forced themselves on stage, so the reaction of the crowd was instinctive and understandable, to a certain degree. But if we look deeper at why they chose this provocative way of approaching this Seattle crowd, it says a lot about the urgency of Black Lives Matter and the lack of awareness among this progressive, liberal audience.

I'm assuming your hypothetical woman is white because Seattle is a predominately white city, and Bernie Sanders supporters are also predominately white. I get that this woman may be upset, but she can Google his remarks later. And, hypothetically, if she personally does not have access to Google, she can go to the library and access different perspectives on the speech that would have been given by Sanders.

But, I’m not concerned with hypotheticals.

Ultimately, it's not a life or death issue for her. Of course, inconveniences are annoying. But what is the worst that is going to happen to this Sanders supporter? I'm more concerned with what is going to happen to young women of color who are silent.

The stakes are higher for women of color.

Unless the status quo is challenged, people will not pay attention. Historically, radical action has created essential space to address these issues. (But was this even that radical?) I think the reactions are just as important to analyze. The booing, the yelling, the chanting—they all show that just because you are a progressive, liberal voter does not mean you are above racism. I get that lot of people put hours into organizing this amazing event to celebrate important services. All those Sanders supporters standing for hours in the sun—maybe their feet are sore or they have a sunburn. But how can I value these inconveniences over what is happening across the country now? I do not see any legitimate complaints, just trivial ones. When you look at those booing in the crowd, they are reflecting white fragility, a means of defense against a public attack on their morality. This is an emotionally charged issue that is hard to convey to someone who hasn’t lived life while black. The negative reaction is proof that achieving racial justice may not relevant to this progressive, liberal crowd. And that is what’s so troubling.

Friedersdorf: Isn’t “proof” a strong word given that we’re talking about the internal thoughts of others? I worry that you’re writing off potential allies prematurely. Imagine attending a Black Lives Matter event where everyone is eager to hear from DeRay McKesson. On the cusp of his speech, the stage is rushed by a group of Muslim Americans who seize the mic and demand four minutes of silence for Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, the 16-year-old killed in America’s drone war (a life-or-death issue). Some BLM audience members begin to boo the interruption.

A Muslim activists says, “This proves your bigotry.” DeRay McKesson never does speak. I'd expect some Black Lives Matter activists to be annoyed by that exchange.

Would that prove that they care more about being inconvenienced than dead Pakistani children? I don’t think that follows. Nor would I characterize them as “attempting to silence an oppressed people,” not if strangers arrived at their event unannounced and specifically demanded their silence. When you write that the progressives in Seattle were “attempting to silence an oppressed people,” I want to acknowledge the many places where abusive policing rises to the level of oppressing black people as a class; I’ve written about conditions in Ferguson and Baltimore, and Stop and Frisk in New York City. And yet, when two black women seize a stage at a progressive event, I would find it offensive if the immediate, reflexive reaction of white progressives in the crowd amounted to, “Oh, don’t object! Those are women of color. They must therefore be both oppressed and speaking to us as representatives of oppressed people.” That would strike me as toxic white superiority disguising itself as deference––“good progressives” prejudging black people as inferiors to be pitied rather than equals to engage as singular individuals.

We’re in total agreement about the urgency of efforts to reform policing and avert unjustified killings. The Washington Post just reported that “so far this year, 24 unarmed black men have been shot and killed by police––one every nine days,” and that “black men accounted for 40 percent of the 60 unarmed deaths, even though they make up just 6 percent of the population.” Dramatically reducing those deaths, as well as the other 60 percent of unarmed people killed, is totally possible. Cops here kill more unarmed people in a month than the combined totals of whole European nations for years. As a writer who’s urged policing reform before Black Lives Matter began, I’m grateful for the attention they’ve brought to the issue and awed by the courage some members have shown protesting militarized police empowered to use lethal force. I wish Sanders and his progressive fans, as well as every other candidate in both parties, pushed for sweeping reforms daily.

But I don’t see how to function in a pluralistic democracy––or profitably cooperate with people who believe in policing reform but count it a lesser priority––if people with shared priorities on policing shut down the events of potential allies because the issue we care about isn’t the one they’re discussing. What if everyone with a life-or-death cause did that? All public events would begin only to be interrupted by a series of earnest people who very reasonably want the nation to grapple more fully with innocents being slaughtered in Syria; highway deaths; catastrophic climate change; drug-resistant bacteria; lead poisoning in poor neighborhoods; earthquake preparedness in the Pacific Northwest, where an imminent temblor is expected to kill thousands. Who is to say how best to prioritize these life-or-death issues, or what degree of attention where would save the most lives?

I’m not saying direct action is never justified, any more than I’d say that it’s never okay to interrupt someone in a conversation. But isn’t it also important to preserve a norm where political movements get to hold events where they can decide what to talk about? That norm best protects the rights of marginalized groups from being silenced by powerful adversaries. (Black Lives Matter would be ill-served by a norm where the relative ability to seize stages by force determines who speaks.) If an attention-grabbing moment was required, what about an action that didn’t come at the expense of a nascent, fragile political movement waging its own unlikely struggle for attention? At least that’s how I reacted, despite being someone who is on board with much more of the BLM agenda than the average American and doesn’t identify at all with the Sanders movement. I respect that your reaction was different; I’m glad it gave you cause for celebration and gave rise to this conversation; and I'm still prepared to be persuaded that this action had salutary effects in Seattle that I can’t see. But I worry that more of the same from Black Lives Matter will harm, not help, an agenda much of which I want to advance. I know I’m not alone in that concern. Maybe I’m wrong. Part of the idea here is to lay out my logic so that you can go after any holes in it, so have at it!

Tesema: I understand where you trying to come from. As I said previously, I’m sure some audience members were annoyed and reacted instinctively on a human level.

But history and power need to be taken into account.

Visually, it’s a very powerful thing to see two women of color upstage a white man. The reflexive reaction of a crowd that understands their whiteness as a privilege and also understands the historical context of black lives in America would, I hope, take that into account and transform it into solidarity rather than pity.

Why does understanding a marginalized voice have to equal pity?

With respect to your hypothetical Muslim Americans, what would they gain from interrupting a movement that doesn’t have a political leader or weight in the issue at hand? There’s a level of allyship between organizations comprised of those who are often pushed to the margins. And the other activist causes that you bring up––worrying that they might use the same tactics––do use protest, historically and currently.

Immigration activists have repeatedly protested political officials. ACT UP shut down Wall Street. Climate change activists directly challenged Shell Oil. All these issues are important and valid. I think we can agree no value system exists that will allow us to rank these life-or-death causes. Police brutality and the way our institutions affect the quality of black lives matters to me more than it may matter to others. That does not mean I cannot and do not also support students, for example, who march against universities demanding their institutions divest from fossil fuels.

But preserving a norm that has been beneficial to only a portion of the population is a norm that should not be preserved. Preserving a norm that has a history of largely silencing those on the margins is not a norm I am willing to go back towards.

Whose norm is this that we’re talking about? At whose expense?

In regards to this action coming at the cost of another, I don’t buy that it hurt a “nascent, fragile political movement.” If anything, hasn’t it helped Sanders? His campaign language and actions have become more inclusive, therefore better. In Portland, the next stop on his West Coast jaunt after Seattle, he met with members of Don’t Shoot Portland. The Bernie Sanders campaign has grown stronger, and he has definitely gotten a lot more clicks out of it. However, this is beyond Sanders’ run for the White House. This is about changing the political conversation as a whole not only to include black lives and black voices, but to bring attention to the urgency of the situation at hand. I have no doubt that Black Lives Matter is taking action in different cities without making headlines. If it takes a confrontational action to trigger necessary conversations on a larger scale, so be it.

For a lot of people, asking for change is not on the plate any longer.

Friedersdorf: I want to keep listening here. You’ve alluded to problems in Seattle and expressed hope that Black Lives Matter will create space to address them. What should we know about local conditions there? What changes would you like to see? If every candidate invited BLM activists to speak at an event what message should they?

Tesema: I do appreciate that you want to talk less and listen more. I think that is an often neglected but critical component of allyship. But doesn’t that also extend to critiquing how a black liberation movement should operate? It’s not up to me to speculate what should be said by a BLM activist. That’s a message that’s unique to each rally, each candidate, and each city. And it’s not just a matter of what BLM should say at every event. Black Lives Matter is just a portion of the overall liberation movement.

In Seattle, the action allowed room for conversations to happen online and off. I’ve seen a sharp increase. I engaged the other day at a bakery with an elderly woman who hadn’t understood the intentions behind the events that took place here. White progressives across my timelines are engaging in dialogue with each other.

That’s interesting to see.

You don’t often see people critique their privilege and analyze race. The space has been created for the conversations to be elevated, and the sense of urgency has grown.

Seattle sits on Duwamish land, and yet the Duwamish were recently denied federal recognition.There’s an affordable housing crisis in the city that’s pushing away many people of color outside of historically black neighborhoods, and contributing to homelessness. Rent is skyrocketing. Millions of dollars are about to be spent on a new youth jail, rather than implementing services to support vulnerable youth and stop juvenile incarcerations. A proposal to shut down hookah lounges unfairly, without evidence, blames an East African population for violence and strips the spaces and livelihoods of Seattle immigrants. These are just some of the many issues that are prevalent in the city that need to be changed.

Rather than critiquing the Black Lives Matter strategy, what are your thoughts on the aftermath of the protests? It’s been a week and I’m curious to see what you think.

Friedersdorf: I agree that the Bernie Sanders campaign appears to be better off than when we began this exchange and that it is paying closer attention to Black Lives Matter. I assume they’re spending more on event security, too. As noted, I do think that BLM cost itself some goodwill, though I doubt that the single action in Seattle will prove hugely beneficial or costly by itself. I do think the movement should wrestle more with what tactics are most effective going forward. What would the consequences of shutting down another Bernie Sanders event be? More generally, what are the most important obstacles that they have to overcome? To me, they’re most likely to grow stronger if they seek out constructive criticism. How better to discern a movement's flaws or to discover and rebut unfair critiques? If you perceived a flaw that was hurting their success, I’d hate for you to deprive them of your insight because you feel that it isn’t the place of an ally to criticize.

And you're right: One needn't pity a marginalized person or group to hear, understand, or show solidarity with them. But does that invalidate my concern? A black woman at a political rally might be a poor person without any ability to make her voice heard ... or an MBA student at Harvard ... or a columnist at a major newspaper with 100,000 Twitter followers. Her politics might align with social justice progressives or Ben Carson or Rudy Giuliani or Donald Trump. White progressives can respect the individuality of black people; or they can reflexively prejudge black strangers as marginalized or speaking for those who are; but they cannot do both. Automatically giving over their mics to any black protester who unexpectedly jumps on stage at an event might be rationalized in the academic language of “privilege,” but I worry that white progressives would start thinking, “We wouldn’t normally let someone just interrupt, but in this case we'll use that lesser standard of behavior we have for black people.” I’ve seen too many white progressives condescend to blacks and Latinos to think that their prejudgments are harmless.

Don’t misunderstand me. Seeking out marginalized voices is an obligation, and black people like the ones in Ferguson, who’ve suffered under oppressive policing for so long, certainly qualify. I just think there are better ways to let them speak, or to address their plight and needs, than transgressing against the norm that people can assemble and speak without being shut down. And I think you’re wrong in characterizing that norm as having “a history of largely silencing those on the margin.” I’d argue that few norms are more important or helpful to marginalized people and voices than strong protections of assembly, speech and the ability to exercise them.

But maybe you see it differently? You’ve offered a lot of thoughtful fodder, and I've no doubt your next reply will be provide much to reflect on too. With huge thanks for joining me in this exchange, we’ll have this last entry of yours be the last word.

Tesema: Addressing the big picture, I agree that the single action will not be costly by itself. And like we’ve acknowledged, conversations and demonstrations directly related to the event are taking place, so the benefits have been apparent. Just the other day, a group of mostly white demonstrators held an open dialogue on race at Westlake, the site of the BLM action. If a similar form of protest happens, I unfortunately can see how that may attract negative attention. But I also don’t think BLM is concerned with goodwill. Whose goodwill are we talking about? This goes back to the urgency of the situation. One thing to keep in mind here is that given the urgency and the seriousness of the cause, maintaining “goodwill” is not a priority. If “goodwill” was lost, then true “goodwill” wasn’t there to begin with.

I believe the message was received loud and clear (specifically in Seattle) but that doesn’t mean there is not more work to be done. To me, there’s no indication they’re going to continue shutting down Bernie Sanders events. Like many have said, politicians should be disrupted throughout this election process, whether that comes in the form of a protest or in a quieter manner. Similar to how this movement is beyond politicians, it is also is beyond BLM. Various people have different tactics they deem appropriate and effective in their communities across the country.

In theory, seeking out constructive criticism is a great idea. But what are we critiquing, Black Lives Matter as organization or the entire black liberation movement? Someone who is not directly targeted by these injustices is entitled to their opinion, as everyone is entitled to their opinion. But someone who is not affected cannot personally understand the motivation of the movement. What is their frame of reference to critique the ways this movement is engaging to bring about change in communities of color? Do they have the standing to criticize? It feels as if it is a manifestation of privilege to be able to critique a movement that’s not your own.

Rather than critiquing, I feel listening is more effective.

In regards to prejudgements, I believe you can respect someone and still recognize they are marginalized as a result of a systematic failure. But that respect should come first in the form of acknowledgement of the individuality of that person.

At the action in Westlake, no one gave them the mic. They took it, symbolically, because no one is “letting” black people do anything in the face of this pressing crisis. I agree, it’s incredibly problematic thinking if white progressives are reflexively prejudging; I see using language such as “letting” as problematic with moving forward with race relations. Any protester, in my opinion, is not behaving in a “lesser standard of behavior” either. They’re working against a system in the way they know will bring attention to their plight. Activists who protest may “give up on the right and split the left,” as you said. But if that split is necessary to reveal racial tensions within the left, then it's worth it to collectively move forward. Yes, white progressives condescending to blacks and Latinos is one of the core reason for the struggle. That is what I see all these movements collectively pushing to overcome.

I think we’re talking about two different “norms.” You are speaking on the norm of the right to assemble. I’m using broad strokes and speaking in regards of people of color within the historical context of this country. Protections of assembly and speech are critical. There’s no arguing with that. But traditionally, voices other than the white men have been pushed aside, and I’d argue that that has been the norm in this country longer than it has not. Everyone should have the right to speak and address their circumstances, and beyond that, it should be more than just an obligation to have equal representation and an equal chance at a full life. That should be the norm. If that was the norm, it wouldn’t be necessary to “let them speak” in a fashion that adheres to the rules. But it’s not, and that’s why the fight will continue.

To tie it all together:

It’s crucial that these conversations take place at this time in our history. As a young journalist of color, it’s at times difficult to read stories that don’t take your point of view into account. I appreciate you taking the time and effort to engage in this dialogue and your effort to pursue my perspective. This movement does not have the option of failing. The fight may be long and complicated but it's a fight that needs to happen right now.

As we were finishing our conversation about the Black Lives Matter action in Seattle, activists with the group tried to interrupt a Hillary Clinton rally but were thwarted by her security. Later, they held a private meeting with the Democratic candidate.

Video of the exchange was posted online.

Saving the Scream Queens

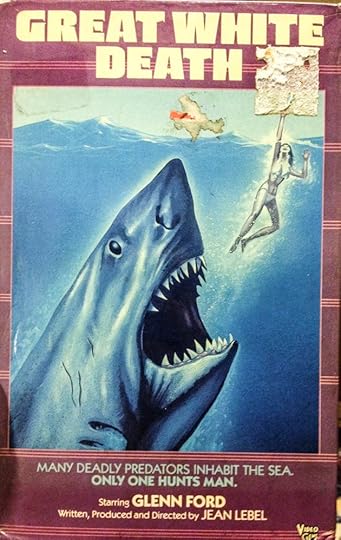

Yale University Library has long been familiar with controversy, even several centuries before it decided to make thousands of VHS tapes with titles like Naughty Roommates, Sorority Babes in the Dance-a-Thon of Death, and What the Swedish Butler Saw part of its collection. The library’s origins date back to 1718, when, after much cantankerous debate over the school’s prospective location, New Haven beat out two rival towns in its bid to host the institution. During the transfer of the school’s books to their new home by wagon train, the residents of Saybrook, Yale’s former home, expressed their frustrations by attacking the train and stealing nearly 250 volumes.#

Related Story

Almost 300 years later, another shipment of material arrived in New Haven: 2,700 VHS tapes from the 1970s and ’80s, making Yale the only U.S. institution that deliberately collects these horror and exploitation movies in magnetic tape format. While these movies obviously aren’t equivalent to the work of Francis Bacon or Isaac Newton, they do carry their own cultural weight, and will hopefully allow researchers to explore the home-video revolution of the time, as well as the cultural mores and politics of the Reagan era they emerged in.

VHS is a maligned medium. Libraries are rapidly culling it from their collections, a project in Ontario, Canada, wants to recycle the province’s 2.26 billion tapes, and the rise of digital streaming has made it mostly irrelevant to the general public. It’s often described as obsolete, even by those charged with preserving America’s cultural heritage. One reason Yale bought this video collection was to preserve rare titles—it’s been estimated that about 40 to 45 percent of content distributed on VHS never made its way into any subsequent digital format. But the primary focus of this collection effort was the physical nature of the medium and the cultures it changed and created.

While not as convenient as a digital format, the physical qualities of VHS offer much more than the 0s and 1s carried on an electron stream directly to televisions. Much like a book’s physical features (paper, binding, dust jackets, the bite of the metal type into the page), and the seemingly secondary aspects of the text (the preface, acknowledgement page, table of contents, index), VHS tapes have tangible qualities that have defined the medium’s uniqueness and its legacy.

* * *

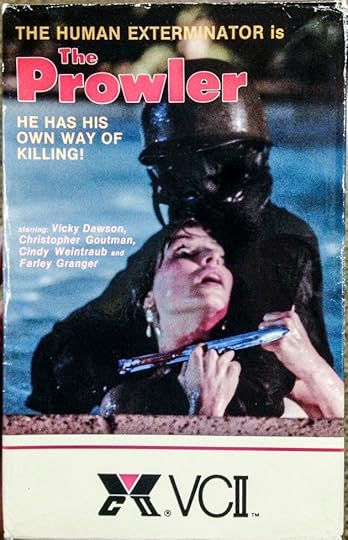

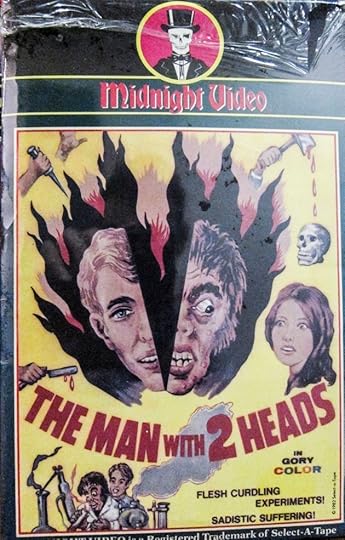

When VHS broke into the popular consciousness in the early ’80s, the demand for it was immediate. To set tapes apart and guarantee profitability, distribution companies like Wizard Video, Thriller Video, and Media Home Entertainment commissioned box art containing shocking, lurid, and gory imagery of sex and violence. Big boxes were quickly introduced, adding several inches of real estate to the original slip covers in order to entice viewers. Not to mention the gimmicky boxes introduced by companies like Imperial Entertainment, who created 3-D molded covers that also featured light and sound effects.

David Gary

David Gary Beyond grabby images, boxes offered blurbs (“Written, directed, and produced by women, SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE will scare you right down to the core”) and witty tag lines (Nail Gun Massacre: “It’s Cheaper Than A Chainsaw!”). The first and last few feet of tape often carried trailers that helped viewers place the movie in a particular genre and learn about other titles they might be interested in. These trailers, which could be quite long and involved, offer evidence of how distribution companies were figuring out the best way to communicate with audiences.

Today, a variety of video content is readily available via YouTube, streaming services, and BitTorrent downloads, but in the late ’70s and ’80s, the idea that someone could control what they watched was revolutionary. Studios tightly managed their content and essentially charged for every viewing. The VCR, however, tapped into a popular desire to consume culture at will. In response to huge demand, distribution companies dug deep into their inventories to fill shelves in rental stores, and amateur moviemakers emerged to satisfy the market. “Shot on video” movies like Sledgehammer, Video Violence, and Blood Cult could be produced on low budgets with relative ease thanks to camcorder technology, and could still find shelf space next to Hollywood blockbusters. Like the steam presses that produced the dime novels and yellow journalism of the late-19th century, videotape allowed a popular culture to emerge.

In the late ’70s and ’80s, the idea that someone could control what they watched was revolutionary.The cheap print of the 19th century required its own distribution networks, including small stands on railway platforms, traveling salesmen who crossed the nation, and retail shops. Similarly, so-called mom-and-pop video stores emerged in the early 1980s to fill a distribution need, as Daniel Herbert explains in his new book, Videoland. With tapes costing a staggering $60-$100 in the early ’80s, the average person couldn’t build a personal video library. Instead people paid a flat membership fee to join a store and spend a few dollars every week to rent a tape. This meant choosing wisely, and often chatting with the clerk for advice or picking up a tape with engaging box art. A large contingent of young people who loved movies became nodes in a social network that brought the local community into the video store out of economic necessity. In this way, the video-rental store brought some movies back to life by creating new audiences for them—a novel phenomenon that contributed to the creation of some “cult classics.” Box art, recommendations, and repeat viewing of tapes offered audiences the ability to judge movies under new circumstances, allowing theatrical flops like The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, and Clue to eventually take off.

David Gary

David Gary The movies in the Yale collection offer scholars of the Reagan era a window into the culture of the period. Class of 1984, a Canadian film about a music teacher at a troubled high school, mirrors some of the anxieties of the time (notably juvenile delinquency and drug use), while other movies go to even greater extremes to examine the age. Deathdream, Cannibal Apocalypse, and Combat Shock appeared on VHS during the ’80s, and comment on the tortured minds of returning Vietnam War veterans, who lash out at a society that’s seemingly forgotten them.

Conservative concern over the decay of family values, which in many respects sparked the Republican Party’s resurgence from the 1960s through the 1980s, led to a number of movies addressing such fears, including Trick or Treat and Black Roses. In both, visiting musicians take over the minds of teenagers through subliminal messages. These works reveal the unsettled feelings many white, Christian, suburban parents had as they witnessed a punk-infused nihilistic attitude catch on amid the youth of the time. Trick or Treat blatantly mocks this reaction by casting Gene Simmons and Ozzy Osbourne in bit parts and satirizing the 1985 Tipper Gore-inspired Senate hearings where Frank Zappa and Dee Snider of Twisted Sister defended their music against their straight-laced critics.

Similar struggles with morality are present in the “shot-on-video” classic Black Devil Doll From Hell, one of the rare horror-exploitation movies written, directed, and produced by an African American, Chester N. Turner. In Black Devil Doll, a sexually repressed Christian woman purchases a doll that comes to life, rapes her, and leaves her with carnal desires she had never previously imagined.

Beyond the downfall of the individual in the face of sudden change, the low-rent slasher film City in Panic depicts what some felt to be the crumbling of society’s moral core. Originally titled The AIDS Murders, City in Panic was released on VHS by Trans World Entertainment in the midst of the HIV epidemic in 1986. The movie depicts the brutal killing of gay men—who are eventually revealed to be on a list of AIDS patients—during sexual acts. The picture uses the AIDS crisis as a cheap plot device, ignoring the complexities of the disease as it struck many American communities. It reflects the religious right’s fear at that time of the seemingly impulsive sexuality of outsider groups.

* * *

In addition to exposing the cultural anxieties and preoccupations of their time, the items in Yale’s VHS collection tell the story of a particularly significant gap between the old Hollywood model of the ’50s and ’60s and the corporate mergers of the ’80s that created today’s modern media behemoths. In the era of video tapes, independent producers and distributors could reach a mass audience using cheap technology and local stores, both of which lowered the profit threshold for moviemakers.

The golden era of VHS ended when studios realized they could make more money from video than from theatrical releases. By 1987, revenues from home video eclipsed theatrical receipts, and after that they grew wildly. Studios used the newfound financial stability video gave them to consolidate the industry and push out the independent producers, distributors, and rental shops. Blockbuster Video’s tagline, “Wow! What a Difference,” captured the transformation. No longer would there be dingy, poorly lit shops offering offbeat movies and pornography; instead there were bright, clean, and inoffensive stores suitable for everyone in the family. The video culture of the 1980s, driven in large part by horror and exploitation films, was a victim of its own success.

David Gary

David Gary Video stores continued to exist in a more anodyne form, but with the rise of the DVD in the late ’90s, the independently distributed tapes and their brash packaging were discarded. Luckily, there were a number of die-hard collectors eager to preserve their legacy. In two recent documentaries, Adjust Your Tracking and Rewind This!, amateur preservationists discuss how they kept tapes in order for future generations to have their own discussions about the material.

VHS collecting follows an arc that can be seen in other attempts to preserve items of wide cultural significance. Initially, vast popularity leads to mass circulation, followed by a general decline in interest, and then an upswing spearheaded by nostalgic adults who experienced the emergence of the trend in their formative years. This is often followed by academic interest, and marks the point where archivists, curators, and librarians start looking for new collections.

Both Harvard and Cornell Universities capitalized on this approach when they founded their respective hip-hop archives. Similarly, in 2010, New York University acquired its Riot Grrrl Collection, which documents the rise of underground feminist punk in the early 1990s. The Library of Congress’s modification of copyright deposit rules in 2006 is another example of riding the nostalgia wave. Now the library acquires physical copies of games instead of just a printed copy of part of the coding and a video example of the final product. Yale acquired its VHS collection under the same philosophy of providing a home for material that was once ubiquitous, but has since lost respect.

No doubt, the value of this collection will be challenged by some, including those who believe that viewing celluloid film on a large screen in a dark theater is the “right” way to watch movies. The notion that film, as the original format of many motion pictures, is superior to videotape is an entrenched belief. But critics and scholars who compare film to lower-quality VHS tapes don’t take into account the cultural impact of home video.

This is changing, with a new generation of scholarship like Joshua Greenberg’s From Betamax to Blockbuster (2008), Caetlin Benson-Allott's Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens (2013), and Michael Z. Newman's Video Revolutions (2014). Yale gathered its collection of early VHS, in part, to support this emerging trend. While the early-18th-century trustees of the university feared the change new materials could bring, the understanding now is that all forms of art—however trashy or out-of-date—offer valuable insight into the cultures they came from.

Carly Rae Jepsen Is Here to Defend Silly Love Songs

Of all the genres about which it’s assumed lyrics don’t matter, radio-friendly pop is right up there next to, say, death metal (whose vocals are typically unintelligible howls). Swedish producers like Max Martin encourage stars to sing nonsense like “Now I’ve become who I really are” to top the charts; Katy Perry may have once and forever proven that cliches sell with the nonsense aphorism-string that is “Roar.” If the hook’s there, who cares?

Related Story

What Would the Next 'Call Me Maybe' Even Sound Like?

Carly Rae Jepsen isn’t likely to inspire any graduate-level seminars on the poetry in her pop. But she should get credit for being more thoughtful than most. “Call Me Maybe” sounded classic but packed in a few layers of novelty, one of which was what the words—co-written, like all of her songs, by Jepsen herself—communicated about desire and destiny in a quirky and memorable way. The rest of her debut album, Kiss, revealed a songwriter who had straightforward concerns—love, love, love—but also an eye for how to render them in ways that seem fresh but not strange. The production team, irresistibly, grafted ’80s exuberance onto modern studio techniques and used savvy melodic math.

Basically, all of the same can be said about her follow-up, E•MO•TION, which, the power of media narratives being what they are, is being talked about as more “mature” or “grown-up” but is really just Carly being Carly. Some people take that to mean bland being bland—the 29-year-old Canadian Idol runner-up has nowhere near as distinctive/dramatic a media presence as Taylor Swift or Ariana Grande or any of the other pop titans at whose heels she theoretically nips. But that’s part of her appeal: providing a grown-up, cohesive, and gimmick-free take on bubblegum.

The final song on Kiss was called “Your Heart Is a Muscle,” and it set out to bust a big cliche: “They say love is a fragile thing, made of glass / but I think your heart is a muscle.” Which is to say, love’s something that rewards you for working at it. Now, on E•MO•TION, Jepsen thinks through the energy expenditure of relationships with an almost scientific precision. The title track has her taunting an ex by asking him to think about “all that we could do with this emotion,” as if he’s wasting a precious resource. “Making the Most of the Night”—whose stutter-chant chorus and nu-“I Want to Dance With Somebody” backing would cut right through Top 40 radio’s sameness if given the chance—mixes its metaphors to the same effect: “Gold mines glisten in the skin.”

If this sounds like a cynical take on romance, it isn’t; Jepsen’s clear-eyed but also capable of abandon. Who can deny the opener, “Run Away With Me”? The peal of a self-consciously cheesy saxophone, the chorus that crashes in waves, and Jepsen’s call/response escapist slogans make for a perfect meeting of lyrical meaning and song form, calculated but also liberated. Then there’s “I Really Like You,” whose blockbuster free-fall of a chorus and giddy take on the idea of liking-not-loving have only seemed more distinctive in the months since it was released (and hailed as the supposed (but not actual) second coming of “Call Me Maybe”).

Throughout, Jepsen seems aware that there are people who’ll write her off just because of her subject matter. “Boy Problems” takes this concern head-on, telling of best friends who can’t seem to hold a conversation that passes the Bechdel Test. “Boy problems, who’s got ’em?” Jepsen asks in the chorus as the music hops and skips like Wham! “I’ve got ‘em too.” Gender specificity aside, she’s reminding listeners that romantic obsession is as universal as it gets; there’s no need to feel guilty about talking about the same things everyone else talks about, especially when you might have something new to say.

Obama’s Letter to the Democrats Wavering on the Deal With Iran

Updated on August 21 at 2:12 p.m. ET

President Obama, in a letter aimed at congressional Democrats wavering over supporting the nuclear deal with Iran, says the U.S. will maintain all options, including military force, should Iran pursue nuclear weapons.

Related Story

Why the Iran Deal Makes Obama's Critics So Angry

“Should Iran seek to dash toward a nuclear weapon, all of the options available to the United States — including the military option — will remain available through the life of the deal and beyond,” Obama wrote in the letter obtained by The New York Times.

The letter dated August 18 is addressed to Congressman Jerrold Nadler of New York, and is aimed at Democrats who have concerns about the deal the U.S. and six world powers struck with Iran over its nuclear program. Here’s more from The Times:

While many of the promises have been made before by Mr. Obama, Secretary of State John Kerry and others, White House officials say the letter represents the first time that the president himself has compiled them under his name and in writing. It commits explicitly to establishing an office within the State Department to carry out the nuclear accord.