Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 368

August 15, 2015

The Meaning of a U.S. Embassy in Havana

My grandchildren will ask, “Were you there, grandma?” The answer will be barely a monosyllable accompanied by a smile. “Yes,” I will tell them, although at the moment the flag of the United States was raised over its embassy in Havana I was gathering opinions for a story, or connected to some Internet access point. “I was there,” I will repeat.

The fact of living in Cuba on August 14 makes the more than 11 million of us participants in a historic event that transcends the raising of an insignia to the top of a flagpole. We are all here, in the epicenter of what is happening.

For my generation, as for so many other Cubans, it is the end of one stage. It does not mean that starting tomorrow everything we have dreamed of will be realized, nor that freedom will break out by the grace of a piece of cloth waving on the Malecón. Now comes the most difficult part. However, it will be that kind of uphill climb in which we cannot blame our failures on our neighbor to the north. It is the beginning of the stage of absorbing who we are, and recognizing why we have only made it this far.

Related Story

The U.S. Flag Flies Over the Embassy in Havana Once Again

The official propaganda will run out of epithets. This has already been happening since the December 17 announcement of the reestablishment of relations between Washington and Havana took all of us by surprise. That equation, repeated so many times, of not permitting an internal dissidence or the existence of other parties because Uncle Sam was waiting for a sign of weakness to pounce on the island, is increasingly unsustainable.

Now, the ideologues of continuity warn that “the war against imperialism” will become more subtle, the methods more sophisticated … but slogans do not understand nuances. “Are they the enemy, or aren’t they?” ask all those who, with the simple logic of reality, experienced a childhood and youth marked by constant paranoia toward that country on the other side of the Straits of Florida.

Now that an official Cuban delegation has shared the U.S. embassy-opening ceremony with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, there is a family photo that they can no longer deny or minimize. There we saw those who until recently called us to the trenches, now shaking hands with their opponent and explaining the change as a new era. And it is good that this is so, because these political pragmatists can no longer turn around and tell us otherwise. We have caught them respecting and allowing entrance to the Stars and Stripes.

The opposition must also understand that we are living in new times—moments of reaching out to the people, and helping them to see that there is a country after the dictatorship and that they can be the voice of millions who suffer every day economic hardship, lack of freedom, police harassment, and lack of expectations. The authoritarianism expressed in warlordism, not wanting to speak with those who are different, or snubbing the other for not thinking like they do, are just other ways of reproducing the Castro regime.

“Are they the enemy, or aren’t they?” ask all those who experienced a youth marked by constant paranoia toward that country on the other side of the Straits of Florida.A conflict of eras is unfolding in Cuba—a collision between two countries: one that has been stranded in the middle of the 20th century, and one that is pushing the other to move forward. They are two islands that clash, but it needs to happen. We know, by the laws of biology and of Kronos, which will prevail. But right now they are in full collision and dragging all of us between the opposing forces.

This Friday’s front-page of the newspaper Granma shows this conflict with a past that doesn’t want to stop playing a starring role in our present—a past tense of military uniforms, guerrillas, bravado, and political tantrums that refuses to give way to a modern and plural country. When one scrutinizes Friday’s edition of the official publication of the Cuban Communist Party, it is easy to detect how a country that is unraveling clings to its past, trying not to make room for the country to come.

In this future Cuba, which is just around the corner, some restless grandchildren will ask me about one day lost in the intense summer of 2015. With a smile, I will be able to tell them, “I was there, I lived it … because I understood the point of inflection that it signified.”

This article was translated from the Spanish by Mary Jo Porter.

‘A Conflict of Eras Is Unfolding in Cuba’

My grandchildren will ask, “Were you there, grandma?” The answer will be barely a monosyllable accompanied by a smile. “Yes,” I will tell them, although at the moment the flag of the United States was raised over its embassy in Havana I was gathering opinions for a story, or connected to some Internet access point. “I was there,” I will repeat.

The fact of living in Cuba on August 14 makes the more than 11 million of us participants in a historic event that transcends the raising of an insignia to the top of a flagpole. We are all here, in the epicenter of what is happening.

For my generation, as for so many other Cubans, it is the end of one stage. It does not mean that starting tomorrow everything we have dreamed of will be realized, nor that freedom will break out by the grace of a piece of cloth waving on the Malecón. Now comes the most difficult part. However, it will be that kind of uphill climb in which we cannot blame our failures on our neighbor to the north. It is the beginning of the stage of absorbing who we are, and recognizing why we have only made it this far.

Related Story

The U.S. Flag Flies Over the Embassy in Havana Once Again

The official propaganda will run out of epithets. This has already been happening since the December 17 announcement of the reestablishment of relations between Washington and Havana took all of us by surprise. That equation, repeated so many times, of not permitting an internal dissidence or the existence of other parties because Uncle Sam was waiting for a sign of weakness to pounce on the island, is increasingly unsustainable.

Now, the ideologues of continuity warn that “the war against imperialism” will become more subtle, the methods more sophisticated … but slogans do not understand nuances. “Are they the enemy, or aren’t they?” ask all those who, with the simple logic of reality, experienced a childhood and youth marked by constant paranoia toward that country on the other side of the Straits of Florida.

Now that an official Cuban delegation has shared the U.S. embassy-opening ceremony with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, there is a family photo that they can no longer deny or minimize. There we saw those who until recently called us to the trenches, now shaking hands with their opponent and explaining the change as a new era. And it is good that this is so, because these political pragmatists can no longer turn around and tell us otherwise. We have caught them respecting and allowing entrance to the Stars and Stripes.

The opposition must also understand that we are living in new times—moments of reaching out to the people, and helping them to see that there is a country after the dictatorship and that they can be the voice of millions who suffer every day economic hardship, lack of freedom, police harassment, and lack of expectations. The authoritarianism expressed in warlordism, not wanting to speak with those who are different, or snubbing the other for not thinking like they do, are just other ways of reproducing the Castro regime.

“Are they the enemy, or aren’t they?” ask all those who experienced a youth marked by constant paranoia toward that country on the other side of the Straits of Florida.A conflict of eras is unfolding in Cuba—a collision between two countries: one that has been stranded in the middle of the 20th century, and one that is pushing the other to move forward. They are two islands that clash, but it needs to happen. We know, by the laws of biology and of Kronos, which will prevail. But right now they are in full collision and dragging all of us between the opposing forces.

This Friday’s front-page of the newspaper Granma shows this conflict with a past that doesn’t want to stop playing a starring role in our present—a past tense of military uniforms, guerrillas, bravado, and political tantrums that refuses to give way to a modern and plural country. When one scrutinizes Friday’s edition of the official publication of the Cuban Communist Party, it is easy to detect how a country that is unraveling clings to its past, trying not to make room for the country to come.

In this future Cuba, which is just around the corner, some restless grandchildren will ask me about one day lost in the intense summer of 2015. With a smile, I will be able to tell them, “I was there, I lived it … because I understood the point of inflection that it signified.”

This article was translated from the Spanish by Mary Jo Porter.

Rap and the New Rock Star: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

How ‘Rock Star’ Became a Business Buzzword

Carina Chocano | The New York Times Magazine

“Despite what his ‘Behind the Music’ episode would invariably reveal, a ‘rock star’—or the Platonic ideal of a rock star—was not just a powder keg of charisma and unresolved childhood issues, but a revolutionary driven by a need to assert the primacy of the self in an increasingly alienating commercial world.”

Tinder and One Direction: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Who Got the Camera?: N.W.A.’s Embrace of “Reality,” 1988-1992

Eric Harvey | Pitchfork

“‘Fuck tha Police’ wasn’t provocation, but proxy: a stand-in for the millions of stifled screams wrenched from over-patrolled black neighborhoods nationwide. So maybe it was advocacy, but for catharsis, not the violence that Alerich and the FBI feared.”

Dating Will Never Die

Moira Weigel | The New Republic

“If there is one thing I have learned from combing through over a century of material about dating, it is this: People have been proclaiming that dating is about to die ever since it was invented. What intrigues me about these pieces is: Why does anyone still read them?”

The Modern Noir Has Atrophied (And It’s Not All True Detective’s Fault)

Angelica Jade Bastién | Vulture

“Noir’s shifts in part come down to one question: Whose story is being told? The dominant image of noir today is a white, male power fantasy, whether it be in positioning his brutality as badass in Drive, turning depravity into parody in Sin City, or the empty stylistic exercise of Looper.”

Polishing the Apple: What Dangerous Minds and Other Movies Get Right and Wrong About Teachers

Shea Serrano | Grantland

“The first time I watched Dangerous Minds, I thought it was great—partly because I was 15 years old at the time, and so I wasn’t very good at figuring out what was good or bad yet. But another part was that (obviously) I had not yet been a teacher. Because when I watched it on cable after I’d been a teacher for awhile, it felt like one great big FOH.”

Stephen Colbert Shares Why He Thinks Women Should Be in Charge of Everything

Stephen Colbert | Glamour

“My point is this: Why does this gender inequality still persist, and how can we stop it? I don't have all the answers. And frankly, it's sexist of you to think I do just because I'm a man. C’mon! Besides, it's not my place to mansplain to you about the manstitutionalized manvantages built into Americman manciety. That would make me look like a real manhole.”

The Unbreakable Rebecca Black

Reggie Ugwu | Buzzfeed

“As luck would have it, her overexposure came just moments too soon in the history of the viral video industrial complex to translate into anything resembling a sustainable career. When it comes to making traumatic first impressions on the Internet, Black is patient zero.”

The Forever-Doomed Eastern Europe of Our Imaginations

Harry Merritt | The Awl

“Once the Cold War began, comic books had more reasons than ever to use Eastern Europe—real and imaginary alike—as a setting. Not only did the Fantastic Four and other Marvel Comics heroes do battle with Soviet-sponsored villains from the sixties onward, but the Fantastic Four’s origins exist in a Cold War context as well.”

Canon of Taste

Jill Neimark | Aeon

“There is a growing global movement to establish a culinary canon and to restore the actual local ingredients that composed it. Why shouldn’t there be a canon of taste, like other canons of our civilization, those of literature, art, music, architecture, religion and science? We have a global palate now, and with that, a new willingness to cross-pollinate and revivify regional foodways—and even ways of staging food at the table.”

The Art of Being Underestimated

Jessica Roy | The Cut

“Kim is a handy unofficial barometer of social trends, so let us consider the possibility that she’s onto something. Maybe being underestimated—especially for daring to behave in stereotypically feminine ways, or even just for being a woman in the first place—isn’t a weakness; it’s a secret weapon. No less than Joan Didion, probably the anti-Kardashian, has noted the power of seeming like a nonthreatening girl.”

The Inimitable Helmut Lang

Regardless of whether you follow fashion or not, you know this look—a stark, industrial, sharp-cut, androgynous, predominantly black-and-white mashup of high-fashion and low. And you know it because it’s everywhere.

More From Quartz Retailers should ditch “men’s” and “women’s” departments and embrace genderless fashion Fashion bloggers and photographers on how to take perfect Instagram pictures, every time If you think Amazon is huge now, wait until it becomes America’s biggest fashion retailerWhat you may not know is that it reflects the enduring influence of one designer: Helmut Lang.

This year marks a decade since Lang left the label that still bears his name, and it’s remarkable just how influential the self-taught, Austrian-born designer still is. His hallmarks seem so basic, and are so widespread both on the runway and off, that it’s hard to believe they ever had to be popularized. Though Lang has long since moved on to life as an artist, the clothes he created for his brand remain desirable and relevant enough that they still turn up in editorial shoots, and as an object of obsession among collectors.

In essence what Lang did was create a new design language. He’s regarded as one of the premier minimalists because of the raw, stripped-down, architectural quality of his clothes, and these signatures—along with his color palette of black, white, and earthy neutrals—are easy to spot influencing everyone from Alexander Wang to emerging young designers such as Yang Li and Lee Roach.

“The flat-front pant. The men’s three-button suit. The low-rise jean,” says Joanne Arbuckle, dean of the School of Art and Design at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, enumerating just a few of the current closet staples that Lang pioneered throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. “What he did continues to influence fashion.”

* * *

Just as importantly, he was one of the first high-fashion designers to bring the street onto the runway, reimagining everything from police uniforms to everyday clothing as high fashion. In his hands, the category of simple ready-to-wear was elevated into something avant-garde.

He created the category of designer denim, making jeans a high-fashion item with a matching price tag—nearly $200 back in the ’90s. Lang splattered some of those pricey jeans with paint—rubber-based, so it wouldn’t come off in the wash—mimicking painters’ workwear. Today, the idea is standard fare. On others he incorporated the seamed, ergonomic knees of motorcycle pants. Now the biker jeans made by the luxury brand Balmain are one of the brand’s most popular and iconic items, worn regularly by celebrities such as Kanye West and Kim Kardashian and knocked off routinely by smaller labels. Their DNA can be traced straight back to Lang.

Helmut Lang biker jeans from 1999 (L) and Balmain’s current version (R). (Zachary Wasser / Mr. Porter)

Helmut Lang biker jeans from 1999 (L) and Balmain’s current version (R). (Zachary Wasser / Mr. Porter) He created garments based on bulletproof vests, and fabricated military bomber jackets in high-end or unusual fabrics, transforming them into luxury items. Expensive bombers are now prevalent in the collections of numerous designers, such as Rick Owens, who’s made them in silk and wool. Kanye West openly riffed on Lang’s clothes in his line for Adidas, while streetwear brands repeat these ideas as well, some going so far as to mimic the bondage straps Lang used.

A photo posted by David Casavant (@davidcasavant) on Jun 12, 2015 at 1:49pm PDT

Actually, the use of straps and harnesses, inspired by sources such as parachutes and bondage gear, is one of Lang’s most recognizable innovations. He put straps into the interiors of his jackets, for instance, so they could be worn like backpacks. The same element reappears in the work of New York-based designer Siki Im, who idolized Lang and joined the brand after Lang left, and Rick Owens, again, in a slightly altered form. (Full disclosure: I previously worked for Im.) He also attached them liberally to his clothes purely as design elements to create a look that was industrial and militaristic. It’s an approach echoed in buzzed-about young brands such as Hood By Air and Craig Green.

His use of bondage references, meanwhile, added an aggressive edge that was sexy without being about simply showing skin. Recently, when Taylor Swift made headlines by wearing a harness as part of an outfit, she was following Lang’s lead, whether she knew it or not.

A classic Langian mashup. (Robert Mecea / AP Photo)

A classic Langian mashup. (Robert Mecea / AP Photo) His pioneering use of technical fabrics has had an immense impact on fashion. He would back silk with nylon, for instance, or use textiles blended with metal to get unique textures. In his runway shows, he would juxtapose technical with natural, shiny with opaque, luxe with cheap. (Lang’s long-time collaborator, Melanie Ward, undoubtedly deserves some of the credit too.) It’s all territory designers are still exploring.

“When you think about his sense of the role that tech fabrics would play in fashion, it’s huge,” says Arbuckle. “At that point in time, people thought about them as utilitarian, and think about where we are today—it’s such an important part of fashion.”

All of these innovations gave the designers that followed in Lang’s wake a new conception of how fashion could be done. Even some of the most prominent and supremely creative designers working today owe Lang a debt.

“Without Helmut Lang there would be no Céline, no Raf,” Bernard Wilhelm, a German fashion designer, told i-D. “I’ve heard from people working at different fashion houses that there is always a Helmut Lang piece hanging and it’s right there to be copied.”

* * *

Since Lang departed his label, retiring to a home in East Hampton, he’s traded fashion for art. In February 2010, a fire wrecked part of his New York studio, and along with it a portion of his clothing archive. As Lang looked through the damaged clothing to find what was salvageable, he had the idea to destroy the rest of it himself.

Thankfully he donated a large portion to 18 museums around the world, but the remainder he shredded, and formed into sculptures. 25 years of work, combined with pigment and resin, became eery, elongated trunks, resembling birch trees, some of which appear blackened by fire.

A photo posted by Sperone Westwater (@speronewestwater) on Feb 19, 2015 at 1:26pm PST

The obvious downside of his decision is that it’s difficult to find an extensive collection of his clothes. One of the best resources may, in fact, be a 25-year-old stylist and fashion collector named David Casavant.

During more than a decade of collecting, Casavant has amassed an archive of several thousand pieces—mostly menswear. Originally it served as a resource for stylists, but lately it’s become a place for celebrities, such as Kanye West and Rihanna, to pull items for photo shoots and events. There are only two designers Casavant collects in large quantities: Raf Simons and Helmut Lang.

“You can definitely see Helmut’s influence today in everything really,” Casavant tells Quartz. “He changed the idea of what luxury is. He looked at everything, from military to how people were already dressing on streets to utility wear and uniforms.”

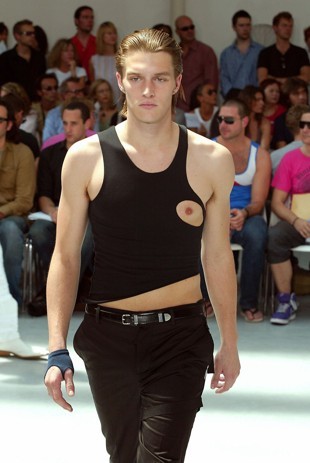

Visiting Casavant’s collection, which is housed in his Manhattan apartment, is like taking a trip through recent fashion history. He has iconic pieces, such as a green version of the tank-top with the nipple cut-out that featured on the runway and in photographer Juergen Teller’s famous ads for Lang. He has bomber jackets, and shiny astronaut pants, as well as Lang’s precisely tailored suits and numerous pairs of jeans.

The infamous nipple tank. (Pierre Verdy / AFP / Getty Images)

The infamous nipple tank. (Pierre Verdy / AFP / Getty Images) “When you get [Lang’s clothes] it’s like you want to look at all of it, you know? The tag is cool, the details are cool, you see what it’s lined with, you see what the cuffs are made out of, you see the bondage details—if it has it,” Casavant says. “I didn’t even necessarily want it for me to wear. I wanted to have it, and just because I like clothes, I wanted to have them to do something with one day, maybe, is what I always thought.”

What’s notable is how modern it all looks. Pieces from the late ’90s would still work on any runway today, and the magazines and stylists that continue to pull Lang’s pieces from Casavant’s archive attest to that.

The clothes would also fit easily into a real person’s wardrobe. “Some designers are great at the shock factor, but I think he was someone who could really provide the excitement and the news, and at the same time they were wearable clothes,” Arbuckle says. “You wanted to wear the clothes.”

* * *

The revolution Lang caused in fashion didn’t end with his clothing. When New York relaunched a dedicated men’s fashion week this year, it was largely in response to a calendar that Lang singlehandedly created. Not wanting to follow the European shows, he moved up the date (paywall) of his spring-summer 1999 show to precede Europe. Other brands, including Calvin Klein, immediately followed suit. By the next season, all the New York shows had adopted Lang’s schedule. Menswear was forced to join as it didn’t have its own week, even though the timing was awkward.

His marketing was similarly groundbreaking. He was the first designer to live stream a runway show on the internet, and the first to advertise on taxi cabs. The ads he made with Jenny Holzer, an American conceptual artist, remain so popular that they routinely circulate on social platforms, such as Instagram and Tumblr.

A photo posted by Sperone Westwater (@speronewestwater) on Feb 19, 2015 at 1:26pm PST

Paradoxically, Lang’s huge sway didn’t always translate into equally sizable earnings. Sales at his brand plunged in the years before he left, though Prada probably deserves to share the blame. When the Italian house bought 51 percent of Helmut Lang in 1999, the company was doing upwards of $100 million in revenue. By 2004, that total had plunged to about $30 million. The New York Times reported that sales fell after Prada cut back significantly on the denim line, which accounted for more than half of revenue, as it sought to turn the brand toward sales of pricey handbags and shoes. Others evidently felt Prada didn’t invest enough time in developing the brand properly.

In 2005, Lang left, and Prada sold the company the next year to Link Theory holdings, the Japanese maker of Theory clothing and subsidiary of Fast Retailing, which owns Uniqlo.

Still, Lang was a powerful force in the industry even as he stepped back from it, and his hold undeniably continues. One of the most prevalent, commercial looks of today is a sporty, diluted version of what Lang did. It’s even the prevailing aesthetic at the current Helmut Lang, which has essentially become a high-end mass-market label.

Angelo Flaccavento, a fashion critic, complained about the lack of originality he saw on the New York runways at the fall shows this past February.

“This week in New York, you could almost tick the boxes as the models strolled by: Céline, done; Vuitton, done; Dior, done. And so on. Not to mention another favorite hunting territory for American designers: Helmut Lang’s industrial/minimalist aesthetic,” he wrote.

If nothing else, it’s evidence that Lang created a design language that was so tuned into the way people dress—and want to dress—that it’s still in use today. It’s so consistently present it’s become a fixed element amid the non-stop motion of the fashion world. New designers may come out and perform their parts on stage; Helmut Lang’s work is now part of the stage itself.

August 14, 2015

Spotify Lost Taylor, but It Won Barack

What is President Obama listening to while vacationing in Martha’s Vineyard this week?

Otis Redding, Justin Timberlake and a little bit of salsa, according to the #POTUSPlaylist, released Friday on Spotify, the music-streaming service. The list, divided into daytime and nighttime playlists, includes 40 of Obama’s “favorite songs for the summer,” the White House said.

This is good news for anyone who has ever wondered what Obama bops along to before a round of golf. It’s also good news for Spotify, a Swedish startup whose U.S. customer base is rapidly growing. In June, Spotify found itself in a battle for listeners’ attention when Apple introduced Apple Music, a subscription-based, music-streaming service. Hey, Spotify said, that’s just like us! And they have more money!

The outlook looked brighter two days later after Apple’s announcement, the Wall Street Journal reported that Spotify had raised $526 million from investors in a round of financing, putting the company’s value at $8.5 billion. (Apple’s value, at $733 billion, is obviously no competition, but consider that Spotify was worth $1 billion and hadn’t even made a profit just two years ago.) This kind of growth seemed to suggest that, when it comes to the music-streaming market, Spotify stood a chance to hold its own in the ring with Apple.

Apple, however, was ready to knock it out—by siding with Spotify’s most famous critic. In November 2014, Swift, who is known for her dislike of streaming services, pulled her wildly successful album “1989” from Spotify. "If this fan went and purchased the record, CD, iTunes, wherever, and then their friends go, 'why did you pay for it? It's free on Spotify,' we're being completely disrespectful to that superfan,” the president of Swift’s record label told Rolling Stone back then.

Swift threatened to do the same with Apple Music. Days before its launch, Swift shamed the service in a blog post, calling its free-three month trial, which would carry music that Apple wasn’t going to pay musical artists to use, “shocking” and “disappointing.” Apple immediately did an about-face. “We hear you @taylorswift13 and indie artists. Love, Apple,” tweeted the company’s Eddy Cue. Apple would pay for every song. Not cheap.

The bad blood between Swift and Apple vanished. The gang’s all there on Apple Music now—”Blank Space” and “Shake it Off” and “Out of the Woods.” But the president’s favorite songs? Only on Spotify.

15 Going on 30: Reading The Diary of a Teenage Girl

Teenagers are as old as humanity; adolescence, however, at least in the arc of American history, is a relatively new thing. Before the late 19th century, and especially before the early 20th—before industrialization and compulsory public education and the economic boom that accompanied them—the transition from adulthood to childhood was treated as barely a transition at all. There was, back then, no warm, soft space between youth and the various drudgeries and exhilarations of adult life. In the America of the 19th century and especially the 20th, though, people began marrying later. They got, via their schools, psychic spaces and actual spaces that emphasized a divide between home and work. Some got access to cars, which gave them even more distance from the watchful eyes of their parents and other authority figures. Adolescence, and all that we associate with it today—freedom, risk, experimentation, mistake-making, boundary-testing, self-discovery, self-evaluation, fashions that seem like a good idea only at the time—were born.

Related Story

Writing of Rage and the Teenage Girl

The Diary of a Teenage Girl, based on the graphic novel of the same name and directed by Marielle Heller in her feature debut, tells the story of a girl who engages in the business of being a teenager during a time when the U.S. itself was experiencing a kind of prolonged adolescence: the mid-1970s. Minnie Goetze, 15, lives in San Francisco with her bohemian mother, her charming little sister, and her mother’s many friends and suitors, the whole cast of characters knocking around each other, pinball-style, in the confines of a dark Painted Lady. Minnie (Bel Powley, in a stunning performance that will rightly be her breakout) is surrounded, in her late youth, by adulthood in many of its forms: Her mother (Kristen Wiig) and her friends imbibe coke and pot and several brown liquors around the kids, and seem always to be on a trip they never quite let themselves come down from.

Minnie, too, is eager to inhale adulthood. And she thinks she knows the way to do that: have sex.

The most convenient source of sex—even more convenient than the adolescent boys that populate her high school—is the man who is constantly around the house: her mother’s layabout boyfriend, Monroe (Alexander Skarsgård). The two flirt, while watching TV on the couch; one night, they go to a bar together, where they flirt some more; finally, they sleep together. Once, and then again. And again. And again. Minnie’s self-styled initiation into adulthood becomes, in short order, that most quintessentially adultish of things: an affair. This is Lolita, only even more complicated—and told, importantly, from Lolita’s point of view.

Much has been made, in early reviews of Diary, of the film’s lack of judgment toward the participants in this weird love triangle—and particularly toward Minnie, the only character in the Goetze family who, in this filmic 1976, occupies the morally sacred space of adolescence. Minnie does, after all, have an affair with her mother’s boyfriend. She also engages, as the film goes on, in drug use (acid, coke, pot) and casual sex (a boy from her high school, a girl from a party) and casual prostitution (she and a friend fellate a pair of boys they meet in a bar in exchange for a few dollars). She runs away from home.

But this is Minnie’s story, and she is at the height of her adolescence, and her age, as such, in Diary's moral cosmology, serves as a kind of cushion. Is her behavior good? Is it bad? It is neither, the film suggests; it is simply the behavior of a teenager. We can neither judge her nor blame her; we can only empathize with her. And hope, and trust, that she grows and learns from her experiences.

What becomes of the sacred space of adolescence when that space gets flattened by digital infrastructures?But if adolescence itself is an accident of history, there’s reason to believe that the things we associate with it—among them a Vegasian, what-happens-there-stays-there approach to the activities that take place under its auspices—may also be contingent. It’s hard not to watch Diary, its images faded in seeming approximation of a ‘70s-style Instagram filter, and not compare Minnie’s adolescence to the many others that are being lived and experienced in 2015. What does it mean, today, nearly 40 years after Diary is set, to be a teenager? Do young people—#teens, as it were—still enjoy the same freedom to make mistakes and get things wrong and get, in the most productive sense, hurt? (“There are so few places for kids to be a little dangerous and maybe hurt themselves, but then come up and realize they’re fine,” Elisha Cooper, a children’s book author, told The New York Times this week in an article praising the dangers that lurk among, of all things, diving boards.) Today may feature helicopter parenting, sure, but it also has, much more universally, digital platforms that have a way of transforming youthful mistakes into permanent media. It has sexting and revenge porn and Facebook and spyware and an Internet that, for better and sometimes for worse, refuses to forget.

What becomes of the sacred space of adolescence when that space gets flattened by digital infrastructures? Could Diary, its story hazy and wounded and blunt and sad and hopeful, apply just as well to a teenager of 2015? Or has adolescence evolved yet again? “This is for all the girls when they have grown,” Minnie says to her diary at the end of the film, both concluding the diary and implying that it was never, strictly, a diary at all. She’s hinting that to be young and to be grown are, still, separate propositions; she’s also hinting, though, at all that may take place when the thing that used to be that most private document of teenage life now exists, like so much else, for public consumption.

China’s Air Problem Is Worse Than You Think

Over the past 10 years of living in and then writing about China, I’ve struck these big three recurring themes:

That it is impressive and notable for the U.S. and China to have managed relations as well as they have over the past 35-plus years, considering the very deep differences between them and the very high stakes for the world; and that it is important for them to keep doing so. That Americans should try to master the mental balancing act of taking China seriously, without being afraid of it. This goes against the nature of big, continental, inward-looking countries like the United States (or China, Russia, India), which tend to take outsiders seriously only when feeling menaced by them. But it’s an important challenge for Americans to meet.The need to take China seriously is obvious because of its scale and impact. The reason not to be afraid of it is that whatever problems the U.S. (or Europe or Japan or other developed countries) might have, China has vastly more. Also, its problems are much harder to solve, simultaneously more urgent and more deeply chronic, and with less margin for error. And I’m not even talking about the stock market / currency disruptions in China that dominate the news now, or the catastrophic explosion in Tianjin. Among these problems, the worst (in my view) is China’s all fronts-environmental crisis. The Chinese government is working very, very hard to deal with its air, water, land, food-supply, and other sustainability challenges. So it’s a race between how hard the country is trying and how dire the situation is.

On this last front, a study out just now from Berkeley Earth in California, written by Robert Rohde and Richard Muller, deserves attention. It concludes that air pollution in China, familiar to everyone, in fact does more damage than is generally recognized. The study finds that as a result of this pollution, some 1.6 million Chinese people per year, or more dramatically well over 4,000 per day, are dying prematurely.

The magenta-colored zones, with average year-round pollution levels classified as “unhealthy” by the U.S. EPA and international standards, cover most of China’s major cities, where many hundreds of millions of people live. (Berkeley Earth)

The magenta-colored zones, with average year-round pollution levels classified as “unhealthy” by the U.S. EPA and international standards, cover most of China’s major cities, where many hundreds of millions of people live. (Berkeley Earth) The overview is here, and the scientific paper itself is here, full of charts and diagrams. The raw statistics behind their findings are available here. Conceptually the news here is familiar, but its detail is significant. The site is well laid-out and informative, and I encourage readers anywhere, but especially in China, to explore it.

Spies, Screams, and Muppets: A Fall TV Preview

For years, analysts have pronounced the coming death of network TV, spurred by the rise of cable networks and Millennials who consume all their media online. But a funny thing happened to the “big five” networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox and The CW) last season: They produced some must-see TV. Rather than simply leaning on a mixture of procedural crime dramas, reality shows and stale sitcoms to stave off extinction, network TV produced event dramas like Empire, How to Get Away With Murder, and The Flash that drew big, consistent ratings and got huge critical buzz. The coming fall season will, as a result, see very little change, as networks double down on what may finally serve as a winning formula.

Related Story

CBS has ruled as America’s number-one network for more than a decade on the backs of popular crime-solving franchises like CSI, NCIS, and Criminal Minds, as well as multi-camera sitcoms like The Big Bang Theory and Mom, all of which will return in September. But its two big new dramas will be pulpier stories based on established brands. First, the heavily advertised Supergirl (premiering October 26th), which borrows from the zippy and colorful approach of The CW’s DC Comics superhero shows (Arrow and The Flash), although apparently won’t be able to cross over with them. Second is an adaptation of the 2011 Bradley Cooper film Limitless (September 22nd) about a man (Jake McDorman) who discovers an experimental drug that quadruples his IQ.

Supergirl (CBS)

Supergirl (CBS) CBS’s slow-and-steady approach has long existed as an outlier to the panicked fumbling of its four major rivals, rejecting plays for younger audiences in exchange for consistency. Its shows are rarely critically favored, outside of the acclaimed drama The Good Wife, which is going into its seventh season, but it’s even rarer to see genuine sci-fi like Supergirl or Limitless. Its other new shows are more along traditional lines—Life in Pieces (September 21st) is a star-studded family sitcom starring James Brolin and Dianne Wiest, and Code Black (September 30th) is essentially a rebooted ER, but set in an L.A. county hospital.

ABC will continue to enjoy the fruits of a successful collaboration with Shonda Rhimes, whose hits Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal, and How to Get Away With Murder have broad appeal. Other old favorites like Castle, Dancing with the Stars, Modern Family, and Nashville form the remainder of the network’s base, which has long appealed more to female viewers. The network’s biggest play this year is to Muppets fans, with The Muppets (September 22nd) pitching itself as an arch behind-the-scenes look at the beloved characters, using the Modern Family mockumentary approach. The only thing ABC really lacks is Sunday night dramas, so it’s debuting two, a Dallas ripoff called Blood & Oil starring Don Johnson, and the FBI serial Quantico (both September 27th). The latter is most notable for featuring Bollywood superstar Priyanka Chopra, an unknown in the States whose global fame far eclipses anyone else on U.S. TV.

Quantico (ABC)

Quantico (ABC) Fox is also staying the course after debuting two big hits last season, the music industry drama Empire (which will begin its run in September rather than January) and the Batman prequel series Gotham. Both will be paired with a new show, Rosewood, starring Morris Chestnut as a brilliant pathologist solving crimes (September 23rd), and an adaptation of Minority Report (September 21st) set 10 years after the Tom Cruise film. Rosewood is as straightforward as it sounds, while Minority Report shoots for the moon and mostly misses, having its protagonist be a grown-up “pre-cog” who can see crimes before they happen.

The network’s biggest play for publicity is Ryan Murphy’s new show Scream Queens (September 22nd), an anthology series along the lines of his American Horror Story, but set in a sorority house and starring Emma Roberts, Lea Michele, Ariana Grande, and Jamie Lee Curtis, among others. It promises to run for 15 episodes and kill off a cast member every week, in an even more supercharged take on the horror miniseries genre Murphy has made his own. As network TV tries to avoid being something you catch up on later, making any show an “event” that demands to be seen live has proven the simplest solution.

Heroes Reborn (NBC)

Heroes Reborn (NBC) That’s probably why NBC is re-launching its old hit Heroes as a 13-episode miniseries called Heroes Reborn (September 24th), featuring some of the show’s old cast and a bunch of unknowns who will be discovering strange new powers for the first time. Whether audiences have much appetite for more Heroes (which went off the air in 2010) so soon is frankly the least of the network’s worries. It did well in the ratings last season because it got to broadcast the Super Bowl, but that honor goes to CBS this year, and NBC has an otherwise dwindling lineup. Neil Patrick Harris is debuting a variety show called Best Time Ever (September 15th), but the public’s interest in variety shows has been pretty much non-existent for decades. The outlandish drama Blindspot (September 21st), starring Thor’s Jaimie Alexander, is more along the right lines—a woman wakes up naked in Times Square covered in tattoos that hint at some larger mystery the FBI must untangle. That’s the kind of gripping, twist-filled drama NBC had a huge hit with in The Blacklist, and it badly needs another.

Typically for fall, network TV dominates new television, but the biggest offering on cable is likely the new season of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story on FX (October 7th), now subtitled Hotel and starring Lady Gaga, Max Greenfield, and Lily Rabe among many others. FX will also debut the delightfully mad medieval drama The Bastard Executioner (September 15th) by Kurt Sutter, who created the long-running hit Sons of Anarchy, while AMC is looking to sustain the popularity of The Walking Dead (October 11th) with a prequel spinoff called Fear the Walking Dead (August 23rd). HBO’s fall offerings remain somewhat lackluster compared to its summer and spring shows, with a second season of The Leftovers (October 4th) serving as the main course. Showtime is betting on a topical fifth season of Homeland, which promises to tackle ISIS, the Charlie Hebdo shootings, and “what Putin’s up to,” according to network president David Nevins.

The Bastard Executioner (FX)

The Bastard Executioner (FX) Even with the advent of DVRs and streaming television, the fall TV season does retain some of the fun of network’s heyday, a gauntlet of new offerings from which only a few shows survive. Outside of a few hoary old crime dramas, this season’s programming is making a big play to join the ranks of serialized, must-see TV—not something you watch because it happens to be on, but something you need to have seen every episode of just to keep up. A few years ago, that’s not a bet network TV would have made on itself, and it’s the clearest sign of self-awareness from an industry that has typically been lacking in that regard.

Straight Outta Compton and the Social Burdens of Hip-Hop

A few decades have changed a lot about hip-hop, but arguably not that much about America. In 1986, the five black teens who eventually became the legendary rap group N.W.A. struggled to navigate life in Compton amid routine police brutality—not unlike many cities today. The biopic chronicling the group’s rise, Straight Outta Compton, comes at a precarious time in the national conversation surrounding racial politics and police violence—one year almost to the day since 19-year-old Michael Brown was killed by an officer in Ferguson.

The film arrives to the joy of hip-hop fans, many of whom remember Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, MC Ren, and DJ Yella and followed their controversial rise to fame. But because N.W.A. made inherently political music—and did so while facing the real-life pressures of excessive policing and racism—it’s impossible to watch without seeing Straight Outta Compton’s urgency and relevance. The biopic highlights how the rappers— particularly the former-drug-dealer-turned-frontman Eazy-E, the hot-tempered lyricist Ice Cube, and the beat master Dr. Dre—were driven to make music by the heavy hand of law enforcement, including the events surrounding the Rodney King beating and the L.A. riots.

Related Story

Is the Rage Behind Ice Cube’s Rodney-King Rap Still Burning?

Straight Outta Compton reminds viewers that N.W.A. became famous for not holding back about what it was like to be young and black and terrorized by the police. And they did so at a time when the music industry was beginning to figure out how to sell rap music to a broader audience. In tracing the history of N.W.A., the film also highlights a divide that has since sprung up in mainstream hip-hop between the more explicitly political rappers, whose music could alienate many white consumers, and the rappers whose music doesn’t overtly tackle social issues and is agreeable to large swaths of listeners. At a time when the #BlackLivesMatter movement and increased coverage of police killings is dominating the public discourse, Straight Outta Compton raises questions about the responsibility of rap artists in bearing witness, as N.W.A. did, to the problems affecting their communities.

* * *

Hip hop has historically been one of the ways for black Americans to see a reflection of their lives in mainstream art, and the ’80s and ’90s were no different. “Rap was the black community’s CNN,” says Akil Houston, a hip-hop scholar, DJ, and assistant professor at Ohio University. In Straight Outta Compton, N.W.A. believes as much. “Our art is a reflection of our reality,” says Ice Cube (played by Ice Cube’s son, O’Shea Jackson Jr.) in the film. He even refers to himself as a journalist who’s “reporting on his community” more honestly than the media itself. When N.W.A.’s manager urges the group to work instead of watching a video of the officers on trial for the Rodney King beatings, they answer: This is the work.

In the film, Eazy-E is thrown against a cop car as officers insult his mother in front of their home, and the incident opens him to Dre’s idea of investing his drug money into music. Some time later, local police officers accost all five members of the group in front of their recording studio. After the confrontation ends with their manager vouching for their presence at the studio, Ice Cube immediately goes in and writes “Fuck Tha Police,” which catapults N.W.A. into the national spotlight. During their subsequent tour, the federal government and the Detroit police force threaten legal action if N.W.A. perform the song. They do it anyway, get arrested, and inspire an audience in Detroit that is navigating a tense racial climate in its own city.

When N.W.A.’s manager urges the group to work instead of watching a video of the officers on trial for the Rodney King beatings, they answer: This is the work.So many moments in the film feel like immediate reflections of American life today. Straight Outta Compton shows the rappers’ relief that King’s beating was captured on video, as well as their hope for justice—echoing the emergence of dashboard-cam footage and citizen-taped videos of encounters with police. At the same time, viewers get to see their disappointment when the two officers accused of attacking King are found not guilty—akin to the reactions of people upset with the acquittal of George Zimmerman and the exoneration of Darren Wilson.

But the film also implicitly raises the question: What do the deaths of Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Trayvon Martin, Sam Dubose, and countless others mean for hip-hop today? A new generation of rappers today is experiencing what it means to be young and black and have their communities suffer unwelcome surveillance from law enforcement, but where is the mainstream music that represents that struggle?

Hip-hop has had a number of socially conscious champions. The genre was birthed out of politically personal storytelling, and artists from KRS-One to Nas to Talib Kweli to Tef Poe have been carrying that torch for decades. But all but a few of the most popular artists—Kendrick Lamar, J. Cole, and Kanye West—seem to be shying away from offering commentary, or doing so with much more reserve and subtlety N.W.A. did. That’s because most rappers are incentivized to uphold the status quo and talk about more commercial-friendly things: money, sex, and partying, says Houston.

The members of N.W.A. made a name for themselves by being outspoken, creating a genuine counterculture, and connecting to people with their honest experience. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and J. Cole’s Forest Hills Drive are examples of artists who’ve channeled that purgative, venting style of rap. Some claim that Kendrick is the new king of hip-hop because he’s true to his experiences as a black kid growing up in Compton—which happened to be at around the same time N.W.A. was telling the same city to “Fuck Tha Police.” The chilling video for his single, “Alright,” shows a black teen lying dead in the street, another running from a Klan-like group, and officers slamming one more to the ground. Lamar performed the song on top of a graffiti-covered squad car at the BET Awards. Protesters at Cleveland State were shown chanting “We gon’ be alright,” the chorus to Lamar’s song, at police officers at demonstrations that followed the killing of Samuel Dubose. Slate’s Aisha Harris suggested that it had become the “new black national anthem.”

In the final track of “Forest Hills Drive,” J.Cole praises the protesters in Ferguson:

Shout out to everybody in Ferguson right now still ridin’, still ridin’/ Everybody else asleep, y’all still ridin’./ And it's bigger than Ferguson, man that shit is fuckin’ nationwide man./We gotta come together, look at each other, love each other. We share a common story nigga that's pain, struggle.

N.W.A.’s success was especially remarkable because the industry hadn’t figured out how to package “gangsta rap” as a product, and thus the artists had freedom to decide what they wanted to say, Houston says. But with the broader commercialization of rap that followed came the rise of hip-hop artists with lyrics and attitudes that were less confrontational—who could appeal to the mostly white music listeners of America. “I think there are a lot of people now that don’t want to say anything that’s offensive to a demographic because so much of who they are is based on being liked,” Houston says.

It’s no surprise that Drake’s listener-friendly If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late is the most downloaded and streamed album in the first half of 2015. Three hip-hop songs were also among the top 10 on-demand singles streamed: “Trap Queen” by Fetty Wap; “See You Again” by Wiz Khalifa featuring Charlie Puth; and “Post to Be” by Omarion featuring Chris Brown and Jhene Aiko. Despite the fact that songs like “Alright” are gaining traction with like-minded listeners, the success of less critical songs reinforces the idea that artists can’t have the best of both worlds: Being black, visceral, angry, critical, and also commercially successful often don’t go together. As Shaun King, an activist and writer who focuses on police brutality, says, “All artists have to make a decision: Do I make music that might have the chance of helping me pay the bills or do I make music that represents my heart, my community, and how the country is going?” With so few big artists successfully choosing the second option, it’s hard to fully condemn those who pick the first.

Many rappers struggle with the need to feel that their work is authentic. Lamar grew up in Compton, lived in L.A. during Rodney King riots, and knows people who are incarcerated. So of course it makes sense that he’d make music criticizing the prison-industrial complex, or lamenting the effects of poverty, or coming to terms with his own newfound fame and wealth.

So it’s perhaps unfair to expect all rappers, some of whom don’t have the lived experience to back up their two cents, to use their music to fight for a cause. “I think their biggest responsibility is to be a real person so that other people can respond to their genuine humanness,” says Irvin Weathersby, a professor at CUNY who uses hip-hop in his classes.

And it’s here also—in capturing N.W.A.’s bare humanity—that Straight Outta Compton also succeeds. Sure, the film has the over-indulgent flair of any biopic: With the exception of showing how Eazy recorded his first song, the film takes a fairly romantic view of the way the group produced their music. One minute, they’re being harassed; the next minute, they’re in the booth making magic. It also leaves out many claims of misogyny against the rappers—perhaps expected of any biopic co-produced by its own subjects (Dr. Dre and Ice Cube). But overall the film manages to tell an entertaining story about N.W.A.’s origins, while making the rappers feel deeply relatable. Their pain, their humiliation, their anger, their fear, their exuberance are all the audience’s.

The film doesn’t shy away from the seemingly unchanged nature of police brutality and the hardships of being black in America—it’s not trying to sell audience a comforting illusion about progress and reconciliation. But it does believe in the ability of artists and everyday citizens to be honest and critical about their situation. At a time when so little popular hip-hop music is eager to champion that same message, Straight Outta Compton and N.W.A. offer a welcome reminder of that collective power.

Japan’s Leader and the ‘Immeasurable Damage’ His Country Inflicted in World War II

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe acknowledged Friday, the 70th anniversary of his country’s surrender in World War II, that Japan inflicted “immeasurable damage and suffering” on innocent people. But his remarks—which stopped short of an unequivocal apology—were unlikely to placate China, South Korea, and other countries in the region that bore the brunt of Japan’s wartime occupation.

“On the 70th anniversary of the end of the war, I bow my head deeply before the souls of all those who perished both at home and abroad,” Abe said. “I express my feelings of profound grief and my eternal, sincere condolences.”

Abe acknowledged the suffering felt by countries that fought against Japan. He said:

In China, Southeast Asia, the Pacific islands and elsewhere that became the battlefields, numerous innocent citizens suffered and fell victim to battles as well as hardships such as severe deprivation of food. We must never forget that there were women behind the battlefields whose honor and dignity were severely injured.

Upon the innocent people did our country inflict immeasurable damage and suffering. What is done cannot be undone. Each and every one of them had his or her life, dream, and beloved family. When I squarely contemplate this obvious fact, even now, I find myself speechless and my heart is rent with the utmost grief.

Comments by Japan’s leaders about the war are closely watched by the country’s neighbors. In 1995, the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, Tomiichi Murayama, the Japanese prime minister at the time, expressed a “heartfelt apology” for Japan’s “colonial rule and aggression.” On the 60th anniversary, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi used similar words.

Abe said comments like those from his predecessors “will remain unshakable into the future.” But the Japanese leader, a conservative, also wants to look to the future. He has pressed for a more muscular security policy and wants to move away from the country’s U.S.-imposed pacifist constitution. He said:

In Japan, the postwar generations now exceed eighty per cent of its population. We must not let our children, grandchildren, and even further generations to come, who have nothing to do with that war, be predestined to apologize. Still, even so, we Japanese, across generations, must squarely face the history of the past. We have the responsibility to inherit the past, in all humbleness, and pass it on to the future.

His remarks, though they were longer than his predecessors’ and contained more context, are unlikely to satisfy his neighbors.

Indeed, China’s state-run Xinhua news agency called Abe’s speech “watered down.”

Instead of offering an unambiguous apology, Abe’s statement is rife with rhetorical twists like ‘maintain our position of apology,’ dead giveaways of his deep-rooted historical revisionism, which has haunted Japan’s neighborhood relations.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower