Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 369

August 14, 2015

The U.S. Flag Flies Over the Embassy in Havana Once Again

Secretary of State John Kerry is in Cuba Friday to attend a historic ceremony in which three retired Marines—the same men who took down the American flag in 1961 when the U.S. embassy closed—unfurl the U.S. flag, as the two countries mark yet another chapter in restoring diplomatic relations.

“For more than half a century, U.S.-Cuban relations have been suspended in the amber of Cold War politics,” Kerry said during the ceremony.

He is the first secretary of state to visit Cuba since 1945. The Washington Post outlined the day’s events:

Speeches are to follow the raising of the banner outside the seven-story embassy building, built in the early 1950s on the Malecón, Havana’s sweeping waterfront boulevard. The U.S. Army’s Brass Quintet will play both country’s anthems.

Richard Blanco, who read at President Obama’s inauguration, will read “Matters of the Sea,” a poem he wrote for the occasion. Blanco’s family left Cuba shortly before he was born in 1968.

Last month, the U.S. and Cuba reopened embassies in their respective capitals for the first time since the two countries severed ties more than half a century ago. Kerry, in a news conference at the time with Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez, called the day “historic.” And that it was. The Cuban flag was added in the State Department to those of other countries that have diplomatic relations with the U.S.

Friday’s ceremony in Havana is the latest in a series of actions to reconcile relations between the Cold War-era adversaries. In December 2014, Obama announced the renewal of diplomatic relations with Cuba.

“I applaud President Obama and President Castro for having the courage to bring us together in the face of considerable opposition,” Kerry said on Friday.

Since the announcement, Cuban President Raul Castro and Obama have met face-to-face, and Cuba has been removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

But, while there has been progress, Kerry acknowledged last month the process “may be long and complex.” He added, “Along the way, we are sure to encounter a bump here and there, and moments of frustration. Patience will be required.” The complexity of the process may be evident in Friday’s ceremony. Cuban dissidents, for example, will not be in attendance. As the Associated Press reports:

That presented a quandary for U.S. officials organizing the ceremony on Friday to mark the reopening of the embassy on Havana's historic waterfront. Inviting dissidents would risk a boycott by Cuban officials including those who negotiated with the U.S. after Presidents Barack Obama and Raul Castro declared detente on Dec. 17. Excluding dissidents would certainly provoke fierce criticism from opponents of Obama's new policy, including Cuban-American Republican presidential candidate Marco Rubio.

The reason, according to a State Department briefing on the event:

The opening ceremony, which is the flag-raising ceremony at the embassy, is principally a government-to-government event. It’ll include officials from the Cuban Government, a range of U.S. Government agencies, as well as members of Congress. There will be some U.S. and Cuban private citizens there, but it is primarily a government-to-government event, and it is extremely constrained in space.

The U.S. embargo on Cuba, which can only be lifted by Congress, continues to be a point of contention. In a newspaper column Thursday, former Cuban leader Fidel Castro criticized the embargo’s impact on his country.

Climate Fiction: Can Books Save the Planet?

The American Southwest has been decimated by drought. Nevada and Arizona skirmish over dwindling shares of the Colorado River, while California watches, deciding if it should just take the whole river all for itself. But when water is more valuable than gold, alliances shift like sand, and the only truth in the desert is that someone will have to bleed if anyone hopes to drink.

Although the above might read like a slightly dramatic spin on the Western U.S. drought crisis, this scenario—at least for now—is imaginary. It’s the teaser for Paolo Bacigalupi’s new novel The Water Knife, another recent addition to the rapidly growing canon of climate fiction. Often called “cli-fi,” the genre, in short, explores the potential, drastic consequences of climate change.

Related Story

Interstellar: Good Space Film, Bad Climate-Change Parable

It’s not an entirely new concept—Jules Verne played with the idea in a few of his novels in the 1880s—but the theme of man-made change doesn’t appear in literature until well into the 20th century. The British author J.G. Ballard pioneered the environmental apocalypse narrative in books such as The Wind from Nowhere starting in the 1960s. But as public awareness of climate change increased, so did the popularity of these themes: Searching for the term “climate fiction” on Amazon today returns over 1,300 results.

Since the turn of the millennium, cli-fi has evolved from a subgenre of science fiction into a class of its own. Unlike traditional sci-fi, its stories seldom focus on imaginary technologies or faraway planets. Instead the pivotal themes are all about Earth, examining the impact of pollution, rising sea levels, and global warming on human civilization. And the genre’s growing presence in college curriculums, as well as its ability to bridge science with the humanities and activism, is making environmental issues more accessible to young readers—proving literature to be a surprisingly valuable tool in collective efforts to address global warming.

When it comes to courting the interest of younger generations, it certainly helps that cli-fi is emerging at the movies and on TV. Last year's Christopher Nolan epic Interstellar shows the American Midwest turning into a second Dust Bowl, with a forecast so dire it drives humans to seek a new planet. In 2014's Snowpiercer, a bungled attempt to stop global warming creates a new ice age. Margaret Atwood’s popular cli-fi trilogy MaddAddam is currently being adapted into a series for HBO, whose wildly popular show Game of Thrones also flirts, if unintentionally, with global-warming themes.

The writer and climate activist Dan Bloom came up with the term “cli-fi” circa 2007, hoping to convert the dull phrase “climate fiction” into something more compelling. “I never defined or even tried to define a new genre,” said Bloom. Instead, he merely wanted to come up with a catchy buzzword to raise awareness about global warming.” The strategy worked: When Atwood used the term in a 2012 tweet, she introduced it to her 500,000 followers, according to Bloom. As the notion of cli-fi took hold, publishers and book reviewers began regarding it as a new category. In this respect, cli-fi is a truly modern literary phenomenon: born as a meme and raised into a distinct genre by the power of social media. Today cli-fi has an actively used hashtag on Twitter, two user-created book lists on Goodreads, and several Facebook groups, including one devoted exclusively to young-adult climate fiction.

Given cli-fi’s contemporary genesis, it’s no surprise the genre is gaining popularity with high school and college-age readers. In a February 2015 feature for The Guardian, the cli-fi author Sarah Holding wrote that the genre “reconnects young readers with their environment, helping them to value it more, especially when today, a large amount of their time is spent in the virtual world.” Environmental themes complement the current trend of dystopian narratives in YA fiction. Bacigalupi’s young adult novels The Drowned Cities (2013) and Ship Breaker (2011) show how rising sea levels reconfigure America, while the protagonists of Sarah Crossan’s Breathe (2012) inhabit a domed city because oxygen is a rare commodity.

Cli-fi is a truly modern literary phenomenon: born as a meme and raised into a distinct genre by the power of social media.The genre offers more than escapist thrills: It’s becoming a springboard for engaging youth in the sciences. Waning interest in STEM subjects has plagued American academia for years. In 2012 the Programme for International Student Assessment found the United States ranked 20th out of 34 countries evaluated for student performance in the sciences. But colleges in the U.S. and abroad—from the University of Oregon to Cambridge University’s Institute of Continuing Education—now offer courses in cli-fi. Earlier this year, students in a cli-fi class at Holyoke extracted DNA from strawberries to understand the genetic engineering themes of Bacigalupi’s award-winning novel The Windup Girl (2009). At Temple University, participants in the cli-fi course used their class blog to share links to science news and cited scientific articles in their book reviews. One student majoring in English admitted on the blog that “when it comes to understanding jargon specific terminology and scientific-based language I get lost and often feel stupid.” The same student went on to post a detailed review of Atwood’s Year of the Flood (2009), examining how climate change would impact various agricultural sectors and describing the chemistry involved.

This fusion of science and the humanities can have practical consequences, encouraging more serious study of STEM, which can intimidate students. With literature and creative writing as a comfortable gateway, “science would become accessible to students who think they aren’t interested in science,” said Ellen Szabo, the author of Saving the World One Word at a Time: Writing Cli-Fi. Szabo’s book discusses the genre’s ability to make environmental issues less political and more personal: Making climate change seem like less of a clinical topic can eventually engender real action. Ted Howell, who teaches the cli-fi class at Temple University, noted that the traditional means of conveying the severity of climate change weren’t effective with his students. “Once they grasped the basic outlines of the issue, they didn’t want to keep reading about 2 percent increases or 4 percent increases in global temperature—they wanted to know what they could do in response,” Howell said.

Howell’s observation aligns with findings from a 2006 working paper released through the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, which explored how different communication methods influenced people’s opinions on climate change. The study explored whether a climate fiction experience—in this case, the popular if scientifically flawed apocalypse film The Day After Tomorrow—would elicit stronger reactions from participants than simply reading a body of information about the causes and effects of climate change. Both sets of respondents reported a positive shift in their concern about climate change following the experiment. However, the group that viewed the film reported a slightly higher willingness to reform social behaviors in favor of mitigating climate change.

Not everyone is convinced of cli-fi’s potential. Last year in an opinion piece for The New York Times, George Marshall—the founder of the Climate Outreach Information Network—expressed concern that cli-fi would reinforce what people already believe rather than change anyone’s minds. “The unconvinced will see these stories as proof that this issue is a fiction, exaggerated for dramatic effect,” he said. “The already convinced will be engaged, but overblown apocalyptic story lines may distance them from the issue of climate change or even objectify the problem.”

The Tyndall Centre study also indicated that placing climate change in a fictional context might reduce the urgency readers feel about the issue in reality, or simply reduce it to a vague concern with no practical remedy. Students in the Temple University class felt a twinge of this, too. “Faced with the realization that a truly adequate response to climate change will necessarily involve significant changes to our lifestyle, and sacrifices by those with money, power, and influence, we often grew despondent,” Howell said. Despondent, but not hopeless: He noted that uncertainty also helps emphasize the vast possibilities for reform.

Therein lies the challenge. “Science doesn't tell us what we should do,” Kingsolver wrote in Flight Behavior. “It only tells us what is.” Stories can never be a solution in themselves, but they have the capacity to inspire action, which is perhaps why cli-fi’s appeal among young adult readers holds such promise. As the scientists and leaders of tomorrow, they may be most capable of addressing climate issues where previous generations have failed. Cli-fi, like the science behind it, often presents bleak visions of the future, but within such frightening prophecies lies the real possibility that it’s not too late to steer in a different direction. As Atwood wrote in MaddAddam, “People need such stories, because however dark, a darkness with voices in it is better than a silent void.”

Warren G. Harding's Terrible Tenure

Dismissed as a failure and all but forgotten, President Warren G. Harding has re-emerged as a much more interesting man over the past 13 months.

Just over a year ago, the Library of Congress released a trove of steamy love letters that Harding wrote to his mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips, in the decade before he became the nation’s 29th president. (How steamy? Let’s just say they feature a character named Jerry, and it’s a body part, not a person.) And on Thursday, The New York Times broke the news that DNA testing had confirmed that Harding, who was married for 33 years until his death in 1923, had fathered a child with a second paramour, Nan Britton, during the same period in which he was penning love notes to Phillips.

The revelation may cement Harding’s place alongside Clinton and Kennedy as the nation’s top presidential philanderers, but it does not come as a shock to historians. “No, he was a womanizer,” said Heather Cox Richardson, a professor at Boston College and author of a recent history of the Republican Party. “It’s absolutely no surprise he fathered a daughter out of wedlock.”

Harding served for just over half a term before he dropped dead of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1923, and even in that short time, he had already earned a “bad boy” image, Richardson said. “By the time he died, rumors had circulated that he was poisoned by his wife,” she said. Four years later, Britton published a scandalous book, “The President’s Child,” in which she named Harding as the father of her daughter, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, and described their years-long affair in detail. Britton was vilified at the time, but the genetic tests now back her claim, to the satisfaction both of her own descendants and many of those of the former president, according to the Times.

Yet the bigger worry for some historians is not the revelations about Harding’s womanizing but the reassessments of his lamentable presidential record that have accompanied them. In a piece Thursday for The Washington Post, James B. Robenalt argued that Harding was actually “a good president.” Sure, his Cabinet was riddled with corruption, but its various scandals—most infamously, the Teapot Dome affair—never touched him directly, Robenalt said. He also credited Harding with putting the federal government on a budget for the first time and setting the conditions for the economic expansion of the Roaring Twenties (which culminated rather disastrously with the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression). Harding, according to Robenalt, was also not that bad on race relations, having voiced support for an anti-lynching law.

“He felt woefully under-qualified for the job, and that set in motion a chain of events that set him up to be one of the worst presidencies in history.”That’s all hogwash, said Kevin Kruse, a historian at Princeton University. In 1920, Harding was a small-town newspaper publisher who had served a single term in the Senate when he was handpicked by Republican Party bosses largely because he was inoffensive and could deliver his home state of Ohio for the GOP. In the aftermath of the First World War and the tumultuous end to the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, voters wanted the “return to normalcy” that Harding promised. And the easy-going Ohioan was the opposite of Wilson, an idealistic academic whose push for U.S. participation in a League of Nations was rejected by the Senate and the public. In a series of tweets on Thursday, Kruse pointed out that the most damning assessment of Harding’s qualifications for the presidency came not from historians or partisans but from the man himself, who admitted repeatedly to reporters that he was in over his head. (“A man of limited talents,” Harding once said of himself.)

“He felt woefully under-qualified for the job, and that set in motion a chain of events that set him up to be one of the worst presidencies in history,” Kruse elaborated to me. “He was nervous about it, so he surrounded himself with old friends from his hometown, who themselves were unqualified for the jobs they held and many of them corrupt.” Harding’s pick to head the veterans bureau just a few years after World War I, for example, was a man he’d met while vacationing and who later engaged in a “massive swindle.” And as fans of HBO’s “Boardwalk Empire” will recall, Harding’s attorney general, Harry Daugherty, was running a criminal operation that made him rich.

Even if Harding was not directly implicated in the scandals, he inarguably took a hands-off approach to governance and was responsible for the men he chose to run the country. “We judge an administration by the president,” Kruse said. “Who do they appoint to put in positions of power? And Harding’s choices across the board were perhaps the worst in American history.” As for Robenalt’s argument that Harding had a solid record on race relations, Kruse and Richardson countered that this was greatly overstated. While voicing nominal support for anti-lynching legislation, Kruse said, he also came out in favor of eugenics and in opposition to “social equality”—a code phrase at the time for interracial marriage.

Harding, Richardson said, has been “swept up” in a broader effort to reassess the legacy of his successor, Calvin Coolidge, who presided over an economic boom and who has recently been held up by the right as an exemplar of small-government conservatism. “It’s really problematic, because even at the time people knew that Harding wasn’t doing very much,” Richardson said. “That’s a real stretch to try to resurrect Harding.” The titillating revelations about Harding's personal life might paint a fuller, more fascinating picture of him as a man, in other words, but that’s no reason to revise his legacy as a forgettable president.

August 13, 2015

Why Some Charges Against Julian Assange Were Dropped

Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks and a prominent anti-government-secrecy activist, won a partial victory in his ongoing legal drama Thursday when the statute of limitations on two allegations against him expired in Sweden. A third allegation will expire next week.

Assange, who is Australian, lived in the U.K. when two Stockholm women accused him of sexual assault and rape in August 2010. He fought his extradition in British courts until June 2012, when he fled to the Ecuadorean embassy in London after losing his final appeals. That’s where he still lives, meeting with visitors and communicating with the outside world through the Internet.

But Assange’s legal saga remains far from over: The most serious charge of rape does not expire until August 2020. And even if that allegation is dropped, British police could still arrest him for violating the terms of his bail agreement when he sought asylum at the embassy. The New York Times reported that between June 2012 and April 2015, the British government spent $14 million on a 24-hour police presence at the embassy in case Assange leaves.

Assange faced four allegations in Sweden in 2010, of which three had five-year statutes of limitations. According to The Guardian, one allegation of sexual molestation and an allegation of unlawful coercion expire Thursday; the other sexual molestation allegation expires August 18.

Marianne Ny, Sweden’s director of public prosecution, insisted Assange be interviewed in Sweden. But Ecuador invited Swedish prosecutors to interview him at the embassy. As the deadline loomed, Swedish officials reversed course in March and offered to interview him at the embassy. That did not happen before three of the charges could expire. The interview is more than a formality or courtesy: Under Swedish law, suspects must be questioned before they can be formally indicted.

Through his lawyers, Assange lamented he would be unable to clear his name.

“By failing to take Assange’s statement at the embassy, Swedish authorities have deprived him of the right to answer false allegations against him that have been widely circulated in the media, but for which he has not been charged,” Assange’s legal team said in a statement Wednesday. “If the case expires, that deprivation will become permanent, and no formal resolution will be available.”

Assange and his supporters also feared his extradition to Sweden would lead to his extradition from there to the United States, where he faces possible prosecution for espionage.

“Assange has also offered to go to Sweden if the authorities agreed not to transfer him to the United States, and they have refused,” his lawyers said.

Swedish officials previously stated that no such pledge could be made under the country’s legal system.

U.S. authorities have reportedly investigated Assange for espionage charges in connection with WikiLeaks’s 2010 publication of thousands of classified U.S. military and diplomatic documents. U.S. Army private Chelsea Manning was convicted of leaking those documents to WikiLeaks and is serving a 35-year prison sentence.

Another hurdle to Assange’s possible extradition is the U.S. death penalty, for which he could be eligible if the U.S. seeks federal espionage charges. The U.S. has not executed a person for espionage since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1952, but it remains an option under federal law. Both Sweden and the U.K. have asserted they would not extradite Assange if he could face the death penalty in the U.S.

Wealthy Viewers Have Subsidized Sesame Street For a Long Time

On Thursday, The New York Times reported that HBO would essentially sponsor Sesame Street’s next five seasons. The premium-cable channel will increase the number of new episodes per year, from 18 to 35, and retain exclusive rights to each new season for nine months after it’s completed. After that de facto embargo ends, new Sesame Street episodes will air on PBS, just as always.

“Sesame Workshop’s new partnership does not change the fundamental role PBS and stations play in the lives of families,” a PBS spokeswoman assured the Times.

There’s a lot to react to here, including the realization that Sesame Street’s friendly Brooklyn brownstones now sit alongside HBO’s other memorable depictions of the tri-state area, in such child-friendly classics as Girls and The Sopranos. But I want to focus on two things: the economics behind the move, at least according to the Times; and how the understanding of Sesame Street as an educational tool has changed over time.

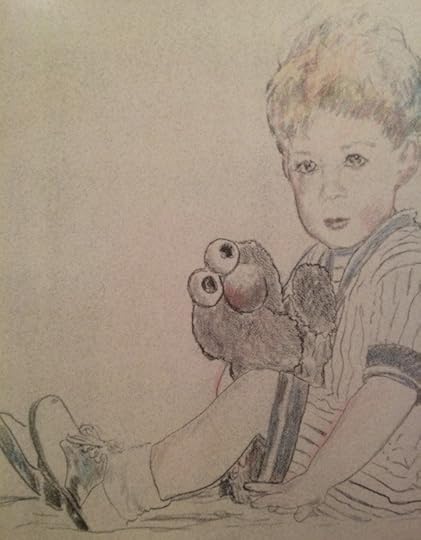

A portrait of the author with Elmo

A portrait of the author with Elmo Before that, though: Almost everyone has a Sesame Street memory, so here is one of mine. When I was a young kid, I had lots of VHS tapes with songs and segments from the show. One of these tapes included “Elmo’s Song.” This was during the interregnum between the character’s introduction, in 1985, and his global ascendancy, in 1996, via the commercial behemoth that was Tickle Me Elmo.

This period came well after Sesame Street’s establishment but quite a few media macro-economies ago. I watched Sesame Street on repeat, like a lot of kids, and I did this on VHS tapes my parents had purchased.

Today, when kids watch Sesame Street on repeat, they’re far more likely to do it on a streaming service like Netflix or Amazon Prime. And that’s a problem for Sesame Workshop, because no streaming service pays the bills like physical media sales do. As the Times writes:

Historically, less than 10 percent of the funding for Sesame Street episodes came from PBS, with the rest financed through licensing revenue, such as DVD sales. Sesame’s business has struggled in recent years because of the rapid rise of streaming and on-demand viewing and the sharp decline in licensing income. About two-thirds of children now watch Sesame Street on demand and do not tune in to PBS to watch the show.

PBS was not able to make up the difference, so Sesame was forced to cut back on the number of episodes it produced and the creation of other new material.

That cut-back has now been reversed, as HBO’s support will allow Sesame Workshop to produce a longer season.

Sesame’s migration to cable begs to be understood as a failure in public funding, and it is in part. In a kinder society, PBS would have more funding, and it could rush in to support a struggling flagship. But what changed in Sesame Workshop’s financial situation wasn’t that PBS cut its funding, but that the media environment in which Sesame Street was operating changed. The same economics that have hurt musicians—the transition from physical ownership to digital ownership to streaming—are what sent Sesame Workshop running to HBO. In a world with less media ownership, even beloved publicly funded media need a premium patron.

* * *

Sesame is almost certainly the most studied TV show ever, and probably the most studied piece of American pop culture ever, too. Sesame Workshop boasts that more than 1,000 studies have been conducted into its efficacy and that “preschoolers who watch [Sesame Street] do significantly better on a whole range of cognitive outcomes than those who don’t.”

One of the best studies on Sesame’s effectiveness was only just released. In June of this year, a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research said that the show is “the largest and least-costly [early childhood] intervention that’s ever been implemented.” This study examined the very first kids who watched Sesame Street after its debut in 1969 and looked at their educational progress and career progress afterward. Kids who watched Sesame Street did a better job of staying with their grade-level through schooling, it found; the study couldn’t isolate quite as well whether it bumped their graduation rates or career wages. As Alia Wong wrote for The Atlantic at the time, that makes the TV show as effective as Head Start, the federal government’s more complete (and much more expensive) early-childhood intervention program.

That was, in part, Sesame Street’s goal: to supplement or replace pre-school at a time when, especially in poorer or more urban areas, it was very much the exception, not the rule. The new study says it managed to do this. Sesame Street improved outcomes for boys, black children, and kids living in “economically disadvantaged areas.”

When it was first proposed, Sesame Street’s “general aim” was that it would “promote the intellectual and cultural growth of preschoolers, particularly disadvantaged preschoolers.” It has long struggled to make good on this “particularly.” Since isn’t just poor children watching the show, but middle-class and more affluent ones, Sesame Street is said to do little for the national achievement gap.

Sesame Street was made to give poorer children a leg up, but by virtue of being a popular TV show, it’s given richer children help too.A book-length 1975 study, Sesame Street Revisited, took up this issue. It found “no evidence that any gaps were being narrowed because of Sesame Street.”

In fact, it said, Sesame Street might be making things worse: “If the series was having any effects on the academic achievement gap, then the data […] indicated that the direction of such effects was toward widening rather than narrowing the gap.” This makes some sense, because presumably more affluent children would be attending pre-school and watching Sesame Street.

It wouldn’t be impossible to narrow the achievement gap by showing all children the same TV show, wrote the authors of Sesame Street Revisited, but it would be hard. They flirted with reducing Sesame Street’s viewing audience to urban and underprivileged areas, so it could only help those kids.

Since then, more evidence has reinforced Sesame’s educational bonafides, and this year’s study even found that disadvantaged kids benefited most from the show—a good sign for its ability to combat the achievement gap. And Sesame Street has of course changed a lot too: A segment on the show introduced in the last decade focuses specifically on narrowing the “word gap” between high- and low-income children.

Yet the problem remains. Sesame Street was made to give poorer children a leg up, but by virtue of being a popular TV show, it’s given richer children help too. (More affluent children, after all, can go to pre-school and watch Sesame Street.) So Thursday’s news, that affluent HBO viewers will get new Sesame episodes for a full nine months before non-premium-cable subscribers get them, doesn’t so much create an unfortunate tension as ratify one. Think of all those DVD and t-shirt sales: Sesame Street has long relied on appealing to richer homes in order to subsidize helping poorer ones.

Now, that relationship will dictate the creation of the show itself.

What Seth Meyers Is Doing Differently

Based on the headlines when Seth Meyers moved his monologue behind a desk for Monday’s episode of Late Night, you could be forgiven for wondering if a seismic shift in TV comedy had finally arrived. But Meyers was really just staying true to the ultimate spirit of late-night television: finding the most durable way to earn laughs on a five-nights-a-week, 150-episodes-a-year schedule. Since taking the reins in February 2014, Meyers has run the gauntlet of trying to keep his jokes topical and relevant while slowly inventing his show on the fly, meaning the last thing he wanted to do is overthink things.

Related Story

Outrageous Humor Is an American Tradition

“I feel like that's one of the luxuries of being the 12:30 show, you can try to be a little more specific,” he told me. “At the end of the day, though, you can only try and execute the best version of your sense of humor. You can get off the rails a little bit by aiming too much when you do comedy.”

Late Night was launched on the back of the persona Meyers had developed over 13 years at Saturday Night Live, but when starting out, all he wanted to do was avoid repeating himself. Hence, the delayed transition to moving behind the desk.

The stand-up monologue has been a fixture of every late-night show since Steve Allen’s, but at a certain point it became a strange cross to bear for the younger, more experimental comedians who’ve been taking the reins. Conan O’Brien has never seemed particularly comfortable with it; his comedy clearly thrives in the other segments of his show. Jimmy Kimmel tried sitting early in his run at Jimmy Kimmel Live!, but quickly reverted to the standing norm. When Meyers—best-known for his time as Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update anchor—became the host of Late Night in 2014, he followed tradition and stood to deliver his opening monologue. But the effect always seemed slightly off.

Meyers says he wanted to give the traditional look a try to at least to distinguish his new show from SNL, which he had left only a month before. “It struck me that [sitting] would look like a crutch,” he recalls. So at first, the priority was just making it through every episode. “Then you reach a point where you can just step back a little bit and make a choice like the one we just made.” The doldrums of August seemed like the right time to make the switch. Meyers notes that Late Night also has a new set, which hasn’t gotten nearly as much attention, even though that change actually required a bit more work than the desk change.

Like many a late-night host before him, Meyers has realized the value of the genre’s inbuilt formats. “I don't think these are traditions as much as they’re structures that have proved they can bear comedy weight. That’s the reason people keep using them,” he says. The stand-up monologue is a quick way to knock out gags about whatever’s happening in the world—vital for any hour-long show that needs to be funny every day. But even though he has plenty of experience in stand-up, he admitted the rapid-fire act could be stressful: “It’s sort of like jumping from log to log over rapids, with each joke representing dry land.”

“I don’t think these are traditions as much as they’re structures that have proved they can bear weight. That’s the reason people keep using them.”Behind a desk, the jokes are similar, but can be slightly more evolved. “It's a tried-and-true, tested delivery system,” Meyers says, adding that the format allows him to punctuate his jokes visually, a long-time SNL gambit similarly employed by Comedy Central hosts like Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. This also makes it easier for the show’s writers to throw in an extra punchline and get more mileage out of a topic.

In the rocky and still-changing world of late-night comedy, Meyers’s show has quietly become a heavy hitter, mixing a solid monologue with great scripted and semi-improvised bits from its writers. For example, Connor O’Malley’s amateurish parody of NBC drama The Blacklist was one of the funniest sketches aired on any TV show this year. Its hastily assembled vibe was simply part of another, newer format in late night, recalling the Digital Shorts that SNL pioneered while Meyers was its head writer. Revolutionary for SNL when they first started airing, the surreal shorts became an integral, familiar part of the show after proving themselves durable vehicles for comedy.

Meyers is the first to acknowledge there’s more change on the horizon. When Colbert, taking over CBS’s Late Show in September, appeared in front of a Television Critics Association panel last week to discuss the move, he was mostly asked how much he planned on shaking things up (Colbert’s responses were vague, although he, too, seems cautiously disinterested in the stand-up monologue).

Meanwhile, more late-night shows are sprouting on the edges of the expanding TV world. Meyers himself appeared on Fusion’s The Chris Gethard Show in June for a more anarchic take on the same broadcasting traditions. In that episode, the show’s cast had been awake for 36 hours before hitting record, while Meyers had had the benefit of a good night’s sleep and was wearing a crisp suit. The results were hilarious, and different, but not unrecognizably so, from Late Night. “Whereas [Gethard’s show] plays with the conventions of the late-night model, it couldn’t if those conventions didn't exist,” Meyers said. Just like Late Night, and any other show of its kind that builds up a loyal audience, Meyers thinks Gethard’s work appeals to viewers because it’s doing something that’s familiar. “The people that consume Chris’s show are similar to people who consume any late-night show. It's a show you come to for comfort and consistency.”

The biggest advantage of the expanding world of TV comedy is that Meyers can offer that comfort on Late Night, and get truly weird somewhere else. He’s producing an upcoming IFC spoof series called Documentary Now! with SNL alums Bill Hader and Fred Armisen. Throughout the creative process, he said, he couldn’t believe they were getting money to do it, and with total creative freedom. That kind of risk-taking lets shows like Chris Gethard make it to air, and allows Netflix to fund a bizarre but wonderful prequel series to the cult film Wet Hot American Summer, which Meyers cited as an inspiration. “When you watch Wet Hot, you don't get any sense that anyone anywhere gave a note,” he said. “It’s nice right now that there are so many places that are letting you do comedy and just getting out of the way.”

Beyoncé and the Politics of Stringy Hair

What is going on with that Beyoncé image in Vogue’s September issue? The cover’s background is not an actual background so much as, it would seem, Photoshop shade #858674; its cover line—“Just B,” with “Beyoncé” beneath it—seems both redundant and oxymoronic; and, worst of all, Beyoncé’s nose has been contoured into Michael Jacksonian proportions—a move that is sadly not new in fashion photography, but that is especially troubling given that Beyoncé is only the third African American woman, after Naomi Campbell in 1989 and Halle Berry in 2010, to grace the cover of that biggest of Vogue issues.

Related Story

There is, however, one other thing that is striking about the cover: Beyoncé’s hair. That hair! That decidedly non-fierce hair! Which is, here, a flat shade of brown, and plainly parted, and notably stringy—not yeah-I-just-got-back-from-a-dip-in-the-Mediterranean stringy, but yeah-I-haven’t-washed-my-hair-in-like-three-weeks stringy. “Drunk in Love” stringy. Beyoncé’s Hair—it has traditionally deserved its own category—has gone through many iterations over the years, featuring regular variations of color and cut and texture and even more regular experimentations with feathering and layering and extensioning and bobbing and beehiving and curling and crimping and flat-ironing and cornrowing and crown-bunning and top-knotting and, occasionally, simultaneous combinations of all of the above.

And here is that hair, that iconic and chameleon-like hair, looking notably, even aggressively ... un-done. Here is Beyoncé, trading in her normally buoyant locks for a look that, via salt water and/or olive oil and/or mousse and/or gel, is not so much #iwokeuplikethis as #iflattenedmyhairlikethis. Here is Vogue, in its September Issue—with its declaration that Beyoncé is one of THE RULE-BREAKERS DEFINING THE WAY WE DRESS NOW—suggesting that “the way we dress now” involves fabulous Marc Jacobs clothes and fabulously impeccable makeup and, finally, a fabulously un-fabulous hairdo. A hairdo that takes those complaints people sent to the FCC after last year’s Grammys—“Her hair was wet,” one viewer groused—and turns them into Fashion.

You could say on the one hand that, beauty trends being what they are, the Un-Done Hairdo is Vogue’s logical reaction—a correction, even—to the trends that the magazine itself, with its promises of accessible allure, helped to bring about. Hair that is done—whether the doneness involves bigness or braids or beachiness or curliness or stick-straightness, has become (somewhat) democratized. The rise of commercial outfits like DryBar and Blo—businesses that offer blowouts at, usually, $30 to $40 a pop, and that throwback to previous generations’ everyday reliance on beauty salons—have exacerbated the atavistic assumption that “done” hair is a symbol, like “done” makeup and manicured nails, of one’s status, emotionally and economically. Us Weekly and Pinterest and Kim Kardashian and The Bachelor have helped to do the same. They have, together, created an arid assumption that a woman’s hair should be, whatever else it is, purposeful. It should reflect effort. The Protestant ethic, only with Pantene.

Here is Beyoncé, trading in her normally buoyant locks for a look that is not so much #iwokeuplikethis as #iflattenedmyhairlikethis.It’s an assumption that I can say, being both a woman and a haver of hair, is fairly terrible. The makeup tax applies to one’s hair, too—the conditioning, the drying, the styling, the tools and time required of all those things. Whereas guys, even with a new emphasis on dude-focused styling products, pretty much wash and go. Add to that the fact that hair is racially fraught (see this great Collier Meyerson video directed at “white people” and tellingly titled “Stop Touching My Hair”), and hair becomes not just a beauty thing, but also a feminist thing and a class thing and a race thing—much more even than fashion and makeup and all the other elements that constitute a Vogue cover. Hair is, along with so much else, political.

And here is the most powerful female celebrity on the planet, on the cover of the biggest issue of what is arguably the world’s most important fashion magazine, seeming to push back against all that. Bey and Vogue are not necessarily recommending that the Normals of the world start rocking stringy hair. What they are doing, though, is what all high fashion will, in the end: They’re setting a new benchmark. They’re suggesting that unkempt hair, Cerulean sweater-style, can and maybe even should trickle down to the habits of Vogue’s readers and admirers and newsstand-passersby. They’re making a political statement disguised as an aesthetic one. Here is Beyoncé, whose brand is strong enough to withstand being photographed with stringy hair, suggesting that, for the rest of us, the best hairdos might be the ones that don’t require all the doing.

Darth Vader 2.0?

At the movies and on TV these days, sci-fi and fantasy stories are easy to come by. Awesome villains, for some reason, are not. The supposedly terrifying computer program that gave Age of Ultron its name was really just the latest in a long line of interchangeable Marvel misanthropes; Game of Thrones, having crossbowed or poisoned its most fun-to-hate characters, has lately relied on the unwatchable creep Ramsay Bolton to cause most of its mayhem; Jurassic World featured a boss-monster whose serial-killer instincts and genetically engineered superpowers were as silly as Bryce Dallas Howard’s heels. Perhaps the closest 2015 has gotten to providing fodder for “Greatest Villains of All Time” lists was in Mad Max: Fury Road, where slaver-warlord Immortan Joe sported a nauseating headpiece and an equally nauseating dadbod.

Related Story

Star Wars: The Nostalgia Awakens

With his death-mask-as-oxygen-supply, Joe resembles, as many great bad guys now do, the foundational space-opera bogeyman—Darth Vader. As pop culture collectively looks back at the original Star Wars trilogy ahead of J.J. Abrams’s Episode VII, it’s clear that Vader, more than any other character, was the key to the series’ success. From the first moments of A New Hope, when the antiseptic-white hallways of a Rebel Cruiser contrasted with the black-clad S&M mannequin walking through it, the great intrigue of Star Wars—and some of the most shocking twists moviegoers have ever experienced—surrounded questions about Darth Vader’s humanity. For most of the trilogy, George Lucas seemed to be crafting a Manichean universe of good people vs. bad people, but Vader ended up complicating that notion in a big way.

Vader's richness as a character is what led to the disastrous prequels, which gave into the fannish impulse to fantasize about iconic backstories to the point of banality. Perhaps there was a way to movingly portray how a talented young orphan became a tyrannical cyborg wizard, and perhaps it was sheer incompetence that made those movies so bad. But the entire exercise was bound to be tricky for anyone. The comedian Patton Oswalt once imagined himself getting in a time machine to caution George Lucas about his plan to make movies about Darth Vader before he was Darth Vader: “I don’t really care about him as a little kid at all, like, at all. I just care about the helmet and the cape and the sword, that’s what’s kind of cool about him.”

Star Wars’ new villain. (Disney)

Star Wars’ new villain. (Disney) From the looks of it, the creators of Disney’s revamped Star Wars franchise have thought a lot about what made the original films “cool” for fans. The Force Awakens’s marketing has boasted about a return to the tactile, worn-down universe Luke Skywalker lived in and a revival of the sleek, Bauhaus aesthetic of the Empire he fought. So far, it appears Episode VII will boast at least three villains, all of whom bear surface-level resemblances to original-trilogy ones. There’s Domhnall Gleeson playing General Hux, wearing military garb and a sneer that recalls pasty Imperial commanders like Grand Moff Tarkin or Admiral Piett. There’s Gwendoline Christie as Captain Phasma, a glorified Storm Trooper whose helmet might just be cool enough to invite comparisons to Boba Fett. And there’s Adam Driver as Kylo Ren, the obvious Darth Vader analogue with a black mask, cape, and red-bladed lightsaber. (It also sounds like Andy Serkis is going to be playing a motion-capture character named Supreme Leader Snoke, who could turn out to be a shadowy bad guy ... or, more frighteningly, another Jar Jar Binks.)

A franchise with a history as rich as this one has the potential to be not just be an exercise in nostalgia, but a comment on it—and its dangers.Though this all is, again, cool, there are reasons to fret about just how closely the new movie appears to be aping the originals. As I pointed out when the latest trailer was released, part of the Star Wars magic has always been imagination; Lucas used real-world influences—Samurai, Westerns, pulp novels—for character designs, locations, concepts that still knocked people out with novelty. The Force Awakens previews, by contrast, look like fan art with a big budget. It’s hard to be an iconic character when you’re basically a clone of an old one, and while remixes can be fun they rarely become cultural classics.

But recent news hints that J.J. Abrams, who proved he knows his way around nostalgia-pastiche with Star Trek, might be up to something clever. In a cover story for the latest EW, Abrams and writer Lawrence Kasdan tell Anthony Breznican a bit about Kylo Ren, the Driver character. The broadsword-hilted lightsaber that ignited controversy when the Force Awakens’s first teaser hit the Internet, it turns out, is homemade—“something that he built himself, and ... as dangerous and as fierce and as ragged as the character.” “Ren” is not a last name but rather a reference to the Knights of Ren, some sort of fraternal order invented by Abrams and Kasdan. And, most interestingly:

… He seems to be a Vader obsessive, with an appearance influenced by that dark lord of the Sith who met his demise long before Ren’s birth. “The movie explains the origins of the mask and where it’s from, but the design was meant to be a nod to the Vader mask,” Abrams tells EW. “[Ren] is well aware of what’s come before, and that’s very much a part of the story of the film.”

A “Vader obsessive”—we all know a few, no? The idea of a villain who’s aping the villain of his universe consciously, rather than out of a movie studio’s desire to play to fans, is an intriguing one. There could even be a hint of satire here. The Force Awakens is set 30 years after Return of the Jedi; this Vanity Fair photo suggests that Kylo Ren wears his helmet as a fashion choice and not as a life-support system like Vader did. Kasdan has said what sets Ren apart is that “he’s full of emotion,” which at first sounds like a platitude but then seems like an important distinction—while Vader worked to conceal his conflicted feelings about fighting his son, I can imagine Driver-as-bad-guy being a bit petulant and petty, not unlike his Girls character in a bad mood, or like Loki, the one successful Marvel movie villain thus far.

Whether this adds up to a compelling bad guy remains to be seen; we still don’t know if Ren is truly the big antagonist or if he’ll just be a cool-looking redshirt like Darth Maul was in Episode I. And while speculating on any J.J. Abrams film’s plot is a sure route to embarrassment, it seems increasingly possible that the new Star Wars narrative will consciously and transparently ponder the appeal of the original three movies. This isn't a radical idea; in sequel-crazed Hollywood, meta is normal (think about Jake Johnson’s Jurassic World character wearing a Jurassic Park shirt). A franchise with a history as rich as this one has the potential to be not just be an exercise in nostalgia, but a comment on it—and its dangers.

A Better Deal With Iran Is Possible

Imagine you’re a conflicted lawmaker in the U.S. Congress. You’ve heard all the arguments about the Iran nuclear agreement, pro and con. A vote on the deal is coming up in September and you have to make a decision. But you are torn.

Most of your colleagues don’t share your angst. They have concluded that the risks of the nuclear accord far exceed its benefits. They will vote to disapprove.

Some take the opposing view. They accept President Barack Obama’s argument that the agreement will effectively block Iran from developing a nuclear weapon for a very long time at little risk to U.S. interests.

Related Story

The President Defends His Iran Plan

You are in a third group. You recognize the substantial achievements in the deal, such as Iran’s commitment to cut its stockpile of enriched uranium by 98 percent, gut the core of its plutonium reactor, and mothball thousands of centrifuges. But you have also heard experts identify a long list of gaps, risks, and complications. These range from the three and a half weeks that Iran can delay inspections of suspect sites, to the billions of dollars that Iran will reap from sanctions relief—some of which will surely end up in the hands of terrorists.

For his part, the president seems to believe that he negotiated a near-perfect deal. In his recent speech at American University, he described the pact as a “permanent” solution to the Iranian nuclear problem. It was a shift from when he told an NPR interviewer in April that once limitations on Iran’s centrifuges and enrichment activities expire in 15 years, Iran’s breakout time to a nuclear weapon would be “shrunk almost down to zero.” Both statements—achieving a “permanent” solution and Iran having near-zero breakout time—cannot be true.

The president has said a “better deal” is a fantasy. But you never took seriously the unknowable assertion that the Iran accord is “the best deal possible,” as though any negotiator emerging from talks would suggest that what he or she has received is anything but “the best deal possible.” And you cringe whenever advocates of the agreement hype its achievements as “unprecedented,” knowing this is not a synonym for “guaranteed effective.”

You may not believe in unicorns, as Secretary of State John Kerry said you must to accept the idea of a “better deal,” but you have been impressed by suggestions on how to strengthen the agreement. The United States could even implement many of these proposals without reopening negotiations with the Iranians and the P5+1 group of world powers. Here are several such options:

Consequences: Repair a glaring gap in the agreement, which offers no clear, agreed-upon penalties for Iranian violations of the deal’s terms short of the last-resort punishment of a “snapback” of UN sanctions against Iran. This is akin to having a legal code with only one punishment—the death penalty—for every crime, from misdemeanors to felonies; the result is that virtually all crimes will go unpunished. The solution is to reach understandings now with America’s European partners, the core elements of which should be made public, on the appropriate penalties to be imposed for a broad spectrum of Iranian violations. These violations could range from delaying access for international inspectors to suspect sites, to attempting to smuggle prohibited items outside the special “procurement channel” that will be created for all nuclear-related goods, to undertaking illicit weapons-design programs. The Iran deal gives the UN Security Council wide berth to define such penalties at a later date, but the penalties have no value in deterring Iran from violating the accord unless they are clarified now. Deterrence: Reach understandings now with European and other international partners about penalties to be imposed on Iran should it transfer any windfall funds from sanctions relief to its regional allies and terrorist proxies rather than spend it on domestic economic needs. U.S. and Western intelligence agencies closely track the financial and military support that Iran provides its allies, and will be carefully following changes in Iran’s disbursement of such assistance. To be effective, these new multilateral sanctions should impose disproportionate penalties on Iran for every marginal dollar sent to Hezbollah in Lebanon, Bashar al-Assad in Syria, etc. Since these sanctions are unrelated to the nuclear issue, they are not precluded by the terms of the Iran agreement. “Snapback” sanctions are akin to having a legal code with only one punishment—the death penalty—for every crime; the result is that virtually all crimes will go unpunished. Pushback: Ramp up U.S. and allied efforts to counter Iran’s negative actions in the Middle East, including interdicting weapons supplies to Hezbollah, Assad, and the Houthis in Yemen; designating as terrorists more leaders of Iranian-backed Shiite militias in Iraq that are committing atrocities; expanding the training and arming of not only the Iraqi security forces but also the Kurdish peshmerga in the north and vetted Sunni forces in western Iraq; and working with Turkey to create a real safe haven in northern Syria where refugees can obtain humanitarian aid and vetted, non-extremist opposition fighters can be trained and equipped to fight against both ISIS and the Iran-backed Assad regime. Declaratory policy: Affirm as a matter of U.S. policy that the United States will use all means necessary to prevent Iran’s accumulation of the fissile material (highly enriched uranium) whose sole useful purpose is for a nuclear weapon. Such a statement, to be endorsed by a congressional resolution, would go beyond the “all options are on the table” formulation that, regrettably, has lost all credibility in the Middle East as a result of the president’s public rejection of the military option. Just as Iran will claim that all restrictions on enrichment disappear after the fifteenth year of the agreement, the United States should go on record now as saying that it will respond with military force should Iran exercise that alleged right in a way that could only lead to a nuclear weapon. It is not for the president 15 years from now to make this declaration; to be effective and enshrined as U.S. doctrine, it should come from the president who negotiated the original deal with Iran. Israeli deterrence: Ensure that Israel retains its own independent deterrent capability against Iran’s potential nuclear weapon by committing to providing technology to the Israelis that would secure this objective over time. A good place to start would be proposing to transfer to Israel the 30,000-pound, bunker-busting Massive Ordnance Penetrator—the only non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. arsenal that could do serious damage to Iran’s underground nuclear installations—and the requisite aircraft to carry this weapon. This alone would not substitute for U.S. efforts to build deterrence against Iran. But making sure Israel has its own assets would be a powerful complement.You wish the president would embrace these sound, sensible suggestions. Inexplicably, he hasn’t. And nothing in the administration’s public posture suggests that he will change course before Congress votes.

So, what will you do?

Some of your colleagues have floated the idea of a “conditional yes” as an alternative to “approve” and “disapprove.” They, like you, recognize that the agreement has some significant advantages but are deeply troubled by its risks and costs. They want to attach strings to their “yes” vote, in the belief that this will bind the president and improve the deal.

But the legislation enabling Congress to review the Iran deal does not accommodate a “conditional yes.” Votes are to “approve” or “disapprove.” Legislators may negotiate with the White House over every comma and colon in a resolution of conditionality, and they may even secure one or two grudging concessions from the White House. But neither a resolution of Congress calling for these improvements nor ad-hoc understandings between the White House and individual legislators has the force of law or policy. According to the Iran-review legislation, the only thing that matters is a yea or nay on the agreement.

Is there really no “third way”?

The answer is yes, there is. Pursuing it requires understanding what the relevant congressional legislation is really about.

Advocates of the agreement have characterized a congressional vote of disapproval as the opening salvo of the next Middle East war. In reality, a “no” vote may have powerful symbolic value, but it has limited practical impact according to the law. It does not, for example, negate the administration’s vote at the UN Security Council in support of the deal, which sanctified the agreement in international law. Nor does it require the president to enforce U.S.sanctions against Iran with vigor. Its only real meaning is to restrict the president’s authority under the law to suspend nuclear-related sanctions on Iran.

A “no” vote on the Iran deal buys time for Obama to adopt remedial measures and then ask Congress to endorse his improved proposal.Here’s the catch: By the terms of the nuclear agreement, the president only decides to suspend those sanctions after international inspectors certify that Iran has fulfilled its core requirements. In other words, congressional disapproval has no direct impact on the actions Iran must take under the agreement to shrink its enriched-uranium stockpile, mothball thousands of centrifuges, and deconstruct the core of its Arak plutonium reactor. Most experts believe that process will take six to nine months, or until the spring of 2016.

Why would Iran do all of these things if it can’t count on the United States to suspend sanctions in response? While it’s impossible to predict with certainty how Iranian leaders would react to congressional disapproval of the agreement, I’d argue chances are high that they would follow through on their commitments anyway, because the deal is simply that good for Iran. After Iran fulfills its early obligations, all United Nations and European Union nuclear-related sanctions come to an end. They aren’t just suspended like U.S. sanctions—they are terminated, presenting Iran with the potential for huge financial and political gain.

The “deal or war” thesis propounded by supporters of the agreement suggests that Iran, in the event of U.S. rejection of the deal, would prefer to bypass that financial and political windfall and instead put its nuclear program into high gear, risking an Israeli and American military response. But that volte-face makes little sense, now that Iran has painstakingly built a nuclear program that is on the verge of achieving the once-unthinkable legitimacy that comes with an international accord implicitly affirming Iran’s right to unrestricted enrichment in the future. In such a scenario, Iran would reap an additional benefit in continuing to implement the agreement: The United States, not Iran, would be isolated diplomatically.

The key point is that a “no” vote on the Iran deal has little practical impact until next year. Between now and then, such a vote buys time, adding up to nine months to the strategic clock. If, before the vote, Obama refuses to adopt a comprehensive set of remedial measures that improves the deal, then a resounding vote of disapproval gives the president additional time to take such action and then ask Congress to endorse his new-and-improved proposal.

Chastened by a stinging congressional defeat in September—one that would include a powerful rebuke by substantial members of his own party—the president might be more willing to correct the flaws in the deal than he is today. That would surely be a more responsible and statesmanlike approach than purposefully circumventing the will of Congress through executive action that effectively lifts sanctions—an alternative the president might consider if he is hell-bent on implementing the agreement.

Those who claim that a “no” vote would destroy the agreement argue that Europe would simply stop enforcing sanctions against Iran should Congress reject the deal. But this too doesn’t stand up to close scrutiny. In my view, the Europeans are more likely to wait six to nine months to see whether Iran fulfills its core requirements under the deal so that they can claim validation for their decision to terminate sanctions. If Congress were to approve Obama’s new-and-improved proposal before Iran complies with its requirements, the United States would still be on schedule to waive its sanctions at the same time that the European Union and United Nations terminate theirs.

So, if you are among the legislators who view the Iran agreement as flawed and are frustrated by the administration’s unwillingness to implement reasonable fixes, there is a way to urge the president to pursue the “better deal” that he keeps urging his detractors to formulate, but that he can’t seem to accept as a possibility. “No” doesn’t necessarily mean “no, never.” It can also mean “not now, not this way.” It may be the best way to get to “yes.”

Christian Bakers Gotta Bake, Even for Gays

Long before the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in the United States, a somewhat surprising group of people became the most formidable legal opponents of gay marriage: cake bakers. Along with photographers, florists, and other vendors who typically provide services for weddings, a handful of bakers across the country claimed they shouldn’t have to serve gay ceremonies; doing so, they said, would violate their religious beliefs.

Related Story

Gay Rights May Come at the Cost of Religious Freedom

In the half decade or so since these claims started coming up, the bakers have mostly lost, and on Thursday, that losing streak continued. The Colorado Court of Appeals ruled that the owners of Masterpiece Cakeshop in Lakewood, Colorado, violated the state’s public-accommodations law when its owner, Jack Phillips, refused to make a cake for Charlie Craig and David Mullins, a gay couple who wanted to marry in 2012. “Phillips believes that decorating cakes is a form of art, that he can honor God through his artistic talents, and that he would displease God by creating cakes for same-sex marriages,” the court wrote in its decision. Even so, it found, a lower court had the right to issue a cease-and-desist order against Masterpiece: Having to bake a cake for a gay wedding doesn’t place an undue burden on Philips’s religious exercise, nor is it a violation of his right to free speech. It's possible that Masterpiece will appeal the case to the Colorado Supreme Court. In a statement, the group that’s representing him, the Alliance Defending Freedom, said that it is discussing “further legal options.”

Legally, this case has a few interesting aspects. First, the court of appeals takes up a somewhat-common free-speech argument, that cake baking is a form of art, and thus a form of free speech. Not so much, the court said. “The act of designing and selling a wedding cake to all customers free of discrimination does not convey a celebratory message about same-sex weddings,” the justices wrote. “To the extent that the public infers from a Masterpiece wedding cake a message celebrating same-sex marriage, that message is more likely to be attributed to the customer than to Masterpiece.”

Under the law, there’s an important distinction between refusing to provide a service and refusing to “say” something. As Doug NeJaime, a UCLA law professor, put it to me in July, “It’s the difference between not providing service because the person’s gay and not doing something in particular because it’s particular speech.” This has been an important factor in other, similar cases, so it’s significant that the Colorado court rejected the idea that cake-baking is primarily a form of artistic expression and speech.

State laws also play an important role in this case. As the justices wrote, “Masterpiece violated Colorado’s public accommodations law by refusing to create a wedding cake for Craig’s and Mullins’ same-sex wedding celebration.” Colorado is one of 22 states, along with the District of Columbia, that have laws forbidding discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in areas like housing, employment, and public accommodations—basically, any business that sells something to people. It’s also not one of the 21 states that has a version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act on the books, which provides special protections for religious groups who claim that certain laws place a burden on their ability to practice their religion. Although the court of appeals considered whether Colorado’s law placed a burden on Phillips’s conscience, it specifically noted that the state doesn’t have a law requiring religious exemptions from rules such as public-accommodations laws.

Although the Masterpiece case follows the pattern of rulings against religious cake bakers, florists, and photographers, the pattern itself is somewhat curious: Why is it that these religious-freedom claims aren’t coming up more frequently in the South, for example, where support for gay marriage is still a minority viewpoint? In part, it’s because these states have different legal priorities from places like Colorado and Oregon, where cake bakers have been shut down in high-profile cases. Most Southern states have special protections for religious groups, but they don’t have special protections against LGBT discrimination. Bakers in Colorado have to bake for gays, and if they don’t, they can be taken to court. But in the majority of states in America, same-sex couples don’t really have the legal cover to put up a fight.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower