Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 371

August 12, 2015

From Whitewater to Benghazi: A Clinton Scandal Primer

The investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails is heating up.

The saga began with Representative Trey Gowdy’s select committee on Benghazi. Those investigations led to the public revelation that the former secretary of state had maintained a private email server, and produced a court order to release the emails in 30-day tranches. Clinton says she neither sent nor received any classified information on the account, but that some material has since been classified.

On Tuesday, federal investigators told members of Congress in a letter that two highly classified emails had been found on Clinton’s personal email system. In response, Clinton’s attorney turned over the server to the FBI, along with thumb drives containing thousands of emails that had previously been turned over to the State Department, The Washington Post reports.

Related Story

In addition to the possible legal ramifications, the investigation has turned up some interesting facts about how much effort Clinton put into the running and upkeep of the server. The server itself had been purchased for her unsuccessful 2008 run for president. Initially, it was run by a former Senate aide, who was then hired by the State Department. Later, amid concerns about reliability, she hired Platte River, the Denver company now subject to FBI questions.

The email controversy is quickly turning into a classic Clinton scandal. Her use of a private email account became known during the course of an investigation into the 2012 deaths of U.S. personnel in Benghazi, Libya. Thus far, the investigations have found no wrongdoing on her part with respect to Benghazi, but Clinton’s private-email use and now the referral concerning classified information have become stories unto themselves. This is something of a pattern with the Clinton family, which has been in the public spotlight since Bill Clinton’s first run for office, in 1974: Something that appears potentially scandalous on its face turns out to be innocuous, but an investigation into it reveals other questionable behavior. The classic case is Whitewater, a failed real-estate investment Bill and Hillary Clinton made in 1978. While no inquiry ever produced evidence of wrongdoing, investigations ultimately led to President Clinton’s impeachment for perjury and obstruction of justice.

With Hillary Clinton leading the field for the Democratic nomination for president, every Clinton scandal—from Whitewater to Clinton’s State Department emails—will be under the microscope. (No other American politicians—even ones as corrupt as Richard Nixon, or as hated by partisans as George W. Bush—has fostered the creation of a permanent multimillion-dollar cottage industry devoted to attacking them.) Keeping track of each controversy, where it came from, and how serious it is, is no small task, so here’s a primer. We’ll update it as new information emerges.

Clinton’s State Department Emails Secretary of State Hillary Clinton checks her phone on board a plane from Malta to Tripoli, Libya. (Kevin Lamarque / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? Setting aside the question of the Clintons’ private email server, what’s in the emails that Clinton did turn over to State? While some of the emails related to Benghazi have been released, there are plenty of others covered by public-records laws that haven’t.

When? 2009-2013

How serious is it? Moderately. The fact that Clinton sorted her own emails would seem to offer some inoculation. But a federal judge’s ruling that the State Department must release new batches of cleared emails every 30 days means there will be a monthly cycle of reporters digging into the cache—bad news for a candidate who’d rather put it behind her. Plus there have already been some strange revelations, like the fact former Clinton confidant Sidney Blumenthal was advising her on Libya and a wide range of matters, and may have been the source of initial, misleading ideas the Benghazi attacks were spontaneous mob violence.

Benghazi A man celebrates as the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi burns on September 11, 2012. (Esam Al-Fetori / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? On September 11, 2012, attackers overran a U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, killing Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans. Since then, Republicans have charged that Hillary Clinton failed to adequately protect U.S. installations or that she attempted to spin the attacks as spontaneous when she knew they were planned terrorist operations.

When? September 11, 2012-present

How serious is it? Benghazi has gradually turned into a classic “it’s not the crime, it’s the coverup” scenario. Only the fringes argue, at this point, that Clinton deliberately withheld aid. A House committee continues to investigate the killings and aftermath. But it was through the Benghazi investigations that Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server became public—a controversy that remains potent.

The Clintons’ Private Email Server Jim Young / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

What? During the course of the Benghazi investigation, New York Times reporter Michael Schmidt learned Clinton had used a personal email account while secretary of state. It turned out she had also been using a private server, located at a house in New York. The result was that Clinton and her staff decided which emails to turn over to the State Department as public records and which to withhold; they say they then destroyed the ones they had designated as personal.

When? 2009-2013, during Clinton’s term as secretary.

Who? Hillary Clinton; Bill Clinton; top aides including Huma Abedin

How serious is it? The rules governing use of personal emails are murky, and Clinton aides insist she followed all rules. There’s no evidence at this point that proves otherwise. The greater political problem for Clinton is it raises questions about how she selected the emails she turned over and what was in the ones she deleted. Are those emails truly deleted? Could the server have been hacked? Some of the emails she received on her personal account are marked sensitive. Plus there’s a entirely different set of questions about Clinton’s State Department emails. The FBI is investigating the security of the server as well as the safety of a thumb drive belonging to her lawyer that contains copies of her emails.

Sidney Blumenthal Blumenthal takes a lunch break while being deposed in private session of the House Select Committee on Benghazi. (Jonathan Ernst / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? A former journalist, Blumenthal was a top aide in the second term of the Bill Clinton administration and helped on messaging during the bad old days. He served as an adviser to Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, and when she took over the State Department, she sought to hire Blumenthal. Obama aides, apparently still smarting over his role in attacks on candidate Obama, refused the request, so Clinton just sought out his counsel informally. At the same time, Blumenthal was drawing a check from the Clinton Foundation.

When? 2009-2013

How serious is it? Some of the damage is already done. Blumenthal was apparently the source of the idea that the Benghazi attacks were spontaneous, a notion that proved incorrect and provided a political bludgeon against Clinton and Obama. He also advised the secretary on a wide range of other issues, from Northern Ireland to China. But emails released so far show even Clinton’s top foreign-policy guru, Jake Sullivan, rejecting Blumenthal’s analysis, raising questions about her judgment in trusting him.

The Speeches Keith Bedford / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic

What? Since Bill Clinton left the White House in 2001, both Clintons have made millions of dollars for giving speeches.

When? 2001-present

Who? Hillary Clinton; Bill Clinton; Chelsea Clinton

How serious is it? This might be the most potent of all the current Clinton scandals. For the couple, who left the White House up to their ears in legal debt, lucrative speeches—mostly by the former president—proved to be an effective way of rebuilding wealth. They have also been an effective magnet for prying questions. Where did Bill, Hillary, and Chelsea Clinton speak? How did they decide how much to charge? What did they say? How did they decide which speeches would be given on behalf of the Clinton Foundation, with fees going to the charity, and which would be treated as personal income? Are there cases of conflicts of interest or quid pro quos—for example, speaking gigs for Bill Clinton on behalf of clients who had business before the State Department?

The Clinton Foundation A brooch for sale at the Clinton Museum Store in Little Rock, Arkansas (Lucy Nicholson / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What? Bill Clinton’s foundation was actually established in 1997, but after leaving the White House it became his primary vehicle for … well, everything. With projects ranging from public health to elephant-poaching protection and small-business assistance to child development, the foundation is a huge global player with several prominent offshoots. In 2013, following Hillary Clinton’s departure as secretary of State, it was renamed the Bill, Hillary, and Chelsea Clinton Foundation.

When? 1997-present

Who? Bill Clinton; Hillary Clinton; Chelsea Clinton, etc.

How serious is it? If the Clinton Foundation’s strength is President Clinton’s endless intellectual omnivorousness, its weakness is the distractibility and lack of interest in detail that sometimes come with it. On a philanthropic level, the foundation gets decent ratings from outside review groups, though critics charge that it’s too diffuse to do much good, that the money has not always achieved what it was intended to, and that in some cases the money doesn’t seem to have achieved its intended purpose. The foundation made errors in its tax returns it has to correct. Overall, however, the essential questions about the Clinton Foundation come down to two, related issues. The first is the seemingly unavoidable conflicts of interest: How did the Clintons’ charitable work intersect with their for-profit speeches? How did their speeches intersect with Hillary Clinton’s work at the State Department? Were there quid-pro-quos involving U.S. policy? The second, connected question is about disclosure. When Clinton became secretary, she agreed that the foundation would make certain disclosures, which it’s now clear it didn’t always do. And the looming questions about Clinton’s State Department emails make it harder to answer those questions.

The Bad Old Days Supporter Dick Furinash holds up cardboard cut-outs of Bill and Hillary Clinton. (Jim Young / Reuters / Zak Bickel / The Atlantic)

What is it? Since the Clintons have a long history of controversies, there are any number of past scandals that continue to float around, especially in conservative media: Whitewater. Troopergate. Paula Jones. Monica Lewinsky. Vince Foster.

When? 1975-2001

Who? Bill Clinton; Hillary Clinton; a brigade of supporting characters

How serious is it? Not terribly. Some are wholly spurious (Foster). Others (Lewinsky, Whitewater) have been so exhaustively investigated it’s hard to imagine them doing much further damage to Hillary Clinton’s standing. In fact, the Lewinsky scandal famously boosted her public approval ratings. But that doesn’t mean you won’t hear plenty about them.

Have We Reached ‘Peak TV’?

“My sense is that 2015 or 2016 will represent peak TV in America and that we’ll begin to see decline coming the year after that and beyond,” John Landgraf, the president of FX Networks, said during the Television Critics Association press tour in Los Angeles. The past year saw more than 370 scripted series on television, he said, including on streaming services; this year, he estimates there will be more than 400. The glut of shows, he says, “has created a huge challenge in finding compelling original stories and the level of talent needed to sustain those stories.” It has also had, he added, “an enormous impact on everyone’s ability to cut through the clutter and create real buzz.”

Related Story

The Golden Age of Post-Television

Is Landgraf right? Have we reached Peak TV? Is the much-applauded (second) Golden Age of TV coming to an end? And will it possibly be replaced with, as the critic Emily Nussbaum half-jokingly called it, “The Caramel Epoch”—an age of shows that are “perfect for a binge” and “suggestively diverse,” and that allow for “equal celebration of comedy, melodrama & varying genres”)? Atlantic staffers Megan Garber, David Sims, Lenika Cruz, and Sophie Gilbert discuss.

Garber: The Caramel Epoch! Oh, wow, I love that. And the basic democratization of quality shows that Nussbaum is describing—ones that aren't necessarily preoccupied with Prestige so much as with being compelling to watch on their own terms—rings totally true. It's the kind of brow-flattening—high- and low- and mid-, all mixed together—that the Internet does so well, applied to TV. Breaking Bad and The Big Bang Theory and old episodes of Boy Meets World and all the others are all bobbing along on this ... the image that keeps coming to mind is one of those all-you-can-eat sushi conveyor belts, but insert your own preferred metaphor here ... and the flattening is productive. And (sorry, the sushi again), delicious.

So, sure, I think Landgraf has a fair point, to an extent, in that television, even crappy television, has high creative overhead: There’s a limited universe of people who have the skills to write and direct and produce shows, and given equipment and budgets and studio space and all of that, there must be a limit, some limit, to the good stuff that can be produced. But while that’s true in theory, I haven't really seen it play out in reality. And, not to take Landgraf too literally, but I don’t see why 370 or 400 or a similar number of scripted shows would necessarily be the peak here—not just because audiences prove willing, again and again, to pay for good content, and not just because the number of people clamoring for jobs in the entertainment industry is the stuff of cliche, but because the new definition of “television”—basically, just serialized video content—seems flexible enough to encompass many, many different types of shows, both costly and not.

Take the serialized Wet Hot American Summer reboot on Netflix, which was clearly filmed around its actors’ other commitments, and which wrote the meta-ness of that into its scripts. Take the fact that the Wet Hot reboot also spawned a documentary about its own making. “Television” is pretty much, at this point, “whatever consumers will watch,” and consumers are pretty permissive when it comes to things like production value. As long as something amuses/horrifies/intrigues/delights/distracts, we’ll at least give it a try. So while, sure, cable and streaming and all the new production outfits that have come on to the scene are going to change things, I don't really see why it would be a peak-and-decline situation. More like a slow evolution—an expansion of how we think about “television” as a medium.

The new definition of “television” seems flexible enough to encompass many, many different types of shows, both costly and not very.The “real buzz” thing is interesting, too, I think, but not necessary for the reason Landgraf gives. Landgraf's is a very production-centric view, which makes sense given his job, but his definition of “buzz” seems to ignore the role that the Internet—a whole universe of people happy to recap and live-tweet and next-day-water-cooler and fan-fic the shows they watch and hate-watch and love and love to hate—plays in curating and introducing shows to new audiences. Hype may exist in a (somewhat) closed system, it’s true, even if the system, given the audience of potential Internet-streamers, is huge. To me, though, the most interesting questions here are about the social conventions that have yet to be fully shaped, and that will in turn shape that hype. What's the statute of limitations on spoiling, for example—a day? A week? A month? A year? How do you talk about TV when TV is no longer, strictly, “television”? There’s a great Key & Peele sketch that gets into that, featuring a dinner party where literally nothing can be talked about because everything will be a spoiler to someone. And it definitely does remain to be seen what television will become once it’s taken, for the most part, out of time.

David, what do you think? Is Landgraf more right than I’m giving him credit for? And/or are we actually approaching the Nougat Epoch?

Sims: If nothing else, I’m happy we’re transitioning from an entertainment era of cold, hard metal to delicious candy. But the idea of a “Caramel Age” represented by shows like Empire, Jane the Virgin, and How to Get Away With Murder strikes me as more specifically about the new, healthier direction of network television away from trying to ape the gritty, anti-heroic “Golden Age.” For years, the big networks tried and failed to ape their cable competitors with grim offerings that seemed to assume that darkness, chiefly, was what distinguished shows like The Sopranos, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad. But then came a new wave of self-aware, heightened serials that know when to have fun and when to double down on the dramatics. These shows are exactly what networks like ABC and Fox need to stay afloat: the kind of “event TV” that you invite your friends over to watch. By the end of its first season run, Empire had a similar share of African American viewers to the Super Bowl. The advertising model may be dead for smaller networks, but there’s still room for it to thrive with a network audience.

Landgraf’s comments about distribution and the growing glut of scripted television reminds me of the parallel question happening in our own industry. The media world seems worried about stories being linked to/hosted on sites like Facebook and Twitter, robbing them of a certain brand recognition, even though those sites have become a vital tool for reaching readers beyond the established base. FX’s programming is among the most widely acclaimed in television and has been for years. The Shield marked a milestone in basic cable shows being taken as seriously as premium networks like HBO, and FX’s continued success has provided a blueprint for stables like AMC and USA. But if you want to catch up on an FX show, most likely you’re going to do it on Netflix. The Americans has been one of the most consistently brilliant shows on television for three years, but one reason it has never struck ratings gold is that it’s not on Netflix for people to catch up on (Amazon has the streaming rights).

The idea of a “Caramel Age” strikes me as more specifically about the new, healthier direction of network television away from trying to ape the gritty, anti-heroic “Golden Age.”That was how Breaking Bad found its audience (its ratings were fairly low until its last couple of seasons, when Netflix binge-watchers joined the party). If a show becomes a hit in retrospect on someone else’s network, does that even matter for FX? As Landgraf says, “As technology evolves and people consume television through different modes of delivery than channels, brands will become increasingly important as mediating filters for the overwhelmed viewing public.” Even more important than ratings or good reviews is FX building up its brand so that viewers will check out its next offering, and having your shows broadcast by a competitor might not help matters on that front. But on the other hand, if FX shows are only available on its own “FXNOW” app, they won’t be nearly as widely viewed.

As you say, Megan, I don’t know that we’re in a “peak” phase as much as a time of expansion, as networks realize the best way to create brand loyalty is to encourage quality. Lifetime’s (brilliant) scripted drama UnREAL didn’t get great ratings, but just finding a toehold in that Internet hype machine is worth it. People can catch up later, check in for season two, or maybe just keep an eye out for whatever the network offers next, now that they’ve been pleasantly surprised. Maybe there will be a problem finding great writers and actors to sustain all this content, but if Landgraf was right about the industry being spread too thin, that’d be reflected in a general decline in quality, which I haven’t really detected. The “caramel age” might be too narrow a term for the big box of chocolates viewers are being offered right now.

Cruz: So, all of us are skeptical of Landgraf’s claim that “too much TV”—even if statistically true—poses a significant threat to the quality we’ll see on our screens in the future. “You take a fixed audience and divide it by 400-plus shows, it stands to reason their ratings will go down," he said. Equally reasonable is that audiences will simply pay attention to certain types of shows, and that will give programmers an idea of what they should be spending their time cultivating—or abandoning. Sure, many of those shows will not be lumped into whatever sweets-themed age of TV we’re in at the time (The Cinnamon Roll Era? The Macaroon Period?). But if given several new shows that feel like familiar ripoffs (prestige or otherwise) and maybe one or two other shows that feel somehow different or special, what will a viewer choose to spend her limited time on? I’m optimistic it’s the latter.

Take USA for example. The network’s “blue skies” brand identity—defined by original shows like Royal Pains and Burn Notice—was challenged by its phenomenal new show Mr. Robot, which USA has been clear is meant to signal a shift toward more creatively ambitious projects. Many skeptics were pretty quickly converted once they actually tuned into the show—critical praise and word-of-mouth have managed to trump 1) the network’s fluffy reputation and 2) the audience’s limited attention. The same goes for Lifetime’s UnREAL, which you mentioned, David—the Internet hype machine is not to be underestimated, or dismissed as not “real buzz.”

Even if a TV glut forces networks to pay attention to what get good ratings, they’ll realize many of those shows have diverse casts.Now, I don’t want to naively lean too heavily on the idea of the TV landscape as any kind of meritocracy. But with the growth of original programming in recent years has come another change that’s difficult to write off: the growing diversity of shows like Orange Is the New Black, Fresh off the Boat, Transparent, Black-ish, Community, and Scandal, as well as (like you mentioned, David) Empire, Jane the Virgin, and How to Get Away With Murder. So even if the TV glut forces networks to pay attention to what gets good ratings, they’ll realize that many of those shows have diverse casts. And from an advertising perspective, the buying power of Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans has grown tremendously in the last 20 years, making the viewership of those groups even more valuable. Now that we’ve reached a critical mass of great shows that aren’t mostly populated by white men, TV critics have become more active and sophisticated in the way they critique a show’s depiction of gender, race, and sexuality—and this in turn has helped shape the direction of many shows.

Landgraf hinged his comments partly on the failure of a show he worked on and thought was outstanding—The Comedians, which paired a veteran comic (Billy Crystal) with a younger, less-experienced one (Josh Gad). Landgraf blames the coming of “peak TV” for the show’s cancellation, but critics didn’t seem to like it very much and the premise perhaps didn’t seem particularly fresh to viewers. (Most TV fans are familiar with the difficult task of proselytizing new shows to friends; today, hyperbole can only get you so far.) Or maybe viewers just didn’t feel like watching another show about two comedian dudes unless there was something genuinely special about it. Meanwhile, the terrific, female-led comedy show Broad City caught on quickly with audiences ... but only after its two young creators got the attention of Comedy Central after building an avid fan base with their rough YouTube web series. With successes like these, it’s hard not to be seduced by the notion that a lot of quality TV will be rewarded, sooner or later. And there seems no better time than now for cult-hit shows that fall under the axe prematurely to win a miraculous afterlife in the form of a reboot, or a pickup by a streaming network.

As long as the number of original programming available continues to expand, we’ll see more shows that take creative risks, or carve out new territory. Sometimes that will lead to spectacular successes ... that turn into spectacular failures in the next moment (ahem, True Detective). I like that you both pointed out the reductive implications of the word “peak”: “Expansion” perhaps better captures the multi-dimensionality of what the industry is going through. As a consumer, my To-Watch list is filled with far too many series—shows that my friends, family, and Twitter feed tell me are novel or weird or fun or Actually The Best—for me to be truly worried that these changes signal a meaningful existential crisis for good TV. And in the unlikely event that it does—I have enough shows (Six Feet Under, Halt and Catch Fire, Friday Night Lights, Doctor Who, The Knick, Parenthood, Downton Abbey, Rectify, Lost, my second rewatch of The X-Files, my 50th rewatch of 30 Rock) to keep me busy until the industry figures itself out.

Gilbert: I think that’s really interesting, Lenika, because I too have a similar list of shows to catch up on and it gives me some sympathy for Landgraf. I have never seen Jane the Virgin. I have never seen Broad City. Sometimes an entire workweek goes by when the only television I watch is episodes of Law and Order: SVU at the gym and Friends (as Chad Velcoro says, both of them are always on).

This isn’t a lack of curiosity on my part—I deeply love television, and am ashamed every day about the number of shows I’ve yet to watch. Part of the guilt is because it’s my job (whoops), but part is because there’s so much of a glut of quality programming that it can feel overwhelming. When Netflix and social media and friends and colleagues and Emmy voters are so consistently reminding you that you have to watch one show or that another show is the actual actual best, the pressure can be so intense that the only rational thing is to give up on novelty and watch a Frasier rerun. (Megan, I know you feel me.)

If I were Landgraf, I wouldn’t be concerned about the glut of original programming debuting each season so much as the glut of outstanding vintage television that’s now so readily available. New shows come along with the seasons as reliably as pumpkin-spice lattes and cable-knit sweaters; most of them are forgotten in less than a year. (Remember Selfie? Or Black Box? Or Constantine? Or The Following? Or One Big Happy? Or Allegiance? Or Backstrom?) But there are 76 episodes of Friday Night Lights I’ve never seen, and 63 of Six Feet Under. Every time someone “discovers” a new old favorite on Netflix, that’s 50 or so hours they’ll spend not watching network television, or flipping between channels and accidentally landing on a winner (this is sadly how I discovered New Girl). And this is to say nothing of all the tried-and-tested shows that are so easy to rewatch, like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, or, yes, 30 Rock.

New shows come along with the seasons as reliably as pumpkin-spice lattes and sweaters; most of them are forgotten in less than a year.Five or ten years ago, if people wanted to rewatch episodes of a favorite show, they had to buy them. Now, they’re readily available, and so the impetus to watch, say, The Comedians is less than it would be if Parks and Rec wasn’t on Netflix, or even most nights on FXX.

But I agree with Lenika that the wealth of new stuff is doing terrific things in terms of providing audiences with more diverse shows that move away from old models with stale formats and rote characters. And if nothing else, there’s consistently more originality on TV than there is in film—even the reboots and the superhero-themed projects tend to be more interesting than their big-screen companions. So if “peak TV” means having too many good shows and not enough time to watch, I’ll take it, happily.

As for ratings, I agree with David that perhaps an analogy is traffic in web journalism. Ezra Klein talked recently about the idea that we’re living in a post-traffic universe, where advertisers care more about the kinds of people reading stories than they do about the number of eyeballs. Maybe the same will become true for television, where word-of-mouth and social-media buzz and the demographics of audiences mean much more than just the number of people tuning in. (David, you touched on this recently in your piece about the not-quite-end of Hannibal.) Alyssa Rosenberg points out in The Washington Post that TV is currently suffering from an advertising problem, in that ads are cheap and there are more products than ever to choose from (also sounds like journalism). But if advertisers start to be swayed by factors other than volume, this can only be a good thing for the quality of the TV that viewers end up with.

The Ripple Effects of China's Weakening Currency

China devalued its currency for the second straight day, sending markets across the region sharply lower and raising fresh concerns about the health of the world’s second-largest economy.

The People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, set the official exchange rate Wednesday at 6.33 to the U.S. dollar, 1.6 percent lower than the level set on Tuesday when, as we reported, the yuan was devalued nearly 2 percent.

Wednesday’s depreciation was the currency’s second-biggest fall since China’s modern exchange-rate system was set up in 1994. The biggest depreciation was Tuesday’s devaluation of the yuan.

In a statement, the central bank pledged it would allow the market a larger role in setting the exchange rate, and added a further devaluation of the currency was unlikely.

“In view of both domestic and international economic and financial condition, currently there is no basis for persistently depreciation of RMB,” the statement said.

But The Wall Street Journal and others reported that China intervened to prop the yuan, which fell nearly 2 percent Wednesday. The move, the newspaper said, underscored “the tricky balancing act now facing its central bank: how to keep the country’s currency from free-falling.”

Wednesday’s move had a ripple effect across the region where both currencies as well as stocks slid. Japan’s Nikkei closed down 1.6 percent, Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index fell 2.4 percent, and shares in Singapore fell 2.9 percent.

The New York Times has more on the reasons for China’s decision to devalue the yuan.

For one, it could help offset the country’s slowing economy. Exports have been particularly hard hit, contracting by 8 percent in July, and a cheaper renminbi makes China-made goods relatively more affordable for consumers in the United States and Europe.

At the same time, China is also seeking a greater role for its currency on the global stage. In recent months, policy makers have been lobbying the International Monetary Fund to include the renminbi in its basket of global reserve currencies, which includes the dollar, euro, yen and pound.

That means convincing the fund that the renminbi is a freely traded currency.

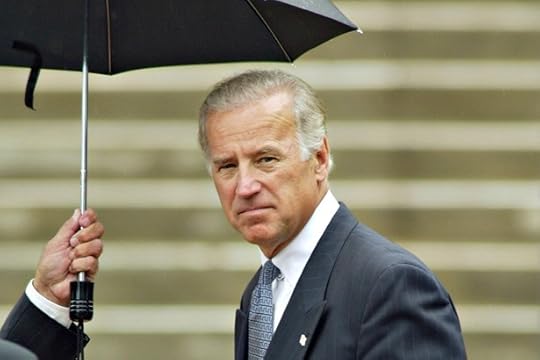

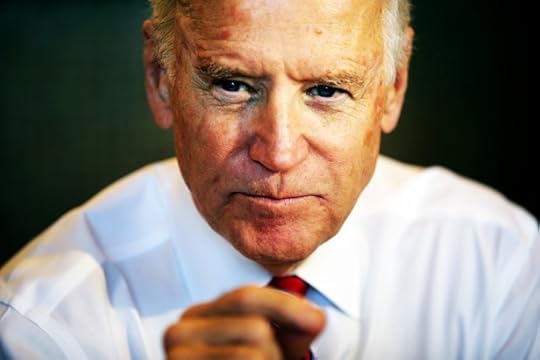

Joe Biden’s South Carolina Strategy

The moment was rich with irony, and Joe Biden wasn’t about to let it slip past.

Here he was, a northeastern, liberal Democrat who went to Washington to take up the cause of civil rights, delivering a eulogy for Strom Thurmond, the legendary South Carolina senator best know for his staunch defense of segregation.

Biden addressed the packed funeral service in Columbia, South Carolina, in 2003 by starting with the obvious: Why had Thurmond wanted him there? “I’ll never figure him out,” Biden told the crowd. The long-time senator from Delaware looked around at familiar faces. “I think this is his last laugh,” he said, a smile coming to his lips.

He proceeded to deliver a nuanced remembrance of both Thurmond the accepting friend and of Thurmond the hard-line segregationist who later changed his views.

South Carolina Democrats, like former state Democratic party chairman Dick Harpootlian, sometimes refer to Biden as the state’s third U.S. senator. They point to that eulogy as just one example of the deep understanding and mutual affection between Biden and the Palmetto State’s political players. If Biden launches a presidential bid, as he’s reportedly considering, it’s South Carolina that may hold the key to his prospects.

Biden’s friendship with Thurmond and with former Senator Fritz Hollings, among others, has made the vice president a regular in the early primary state for years, building what Harpootlian calls a “ready-made” network of supporters eager for Biden to jump into the presidential race. Biden’s regular vacations to Kiawah Island—where he spent the past weekend—have also kept him in contact with key political players in the state.

Related Story

Joe Biden's Under-the-Radar Presidential Bid

As the vice president reportedly mulls a run for the presidency, even as he grieves over his son Beau’s death, many in Washington are looking askance at the probability of a Biden campaign. Since The New York Times published a report that Biden was talking anew to confidantes about a presidential run, and columnist Maureen Dowd reported that the vice president had been implored by his then-ailing son to pursue the office, a bevy of experts have weighed in. And by any tally, most in Washington officialdom are scratching their heads.

Not without reason. Biden has tried for the nation’s top office twice before, in 1988 and 2008, and he never gained much steam. A Washington Post blogger called a Biden run a “terrible idea,” a post that ran under the headline, “Sorry, folks: Joe Biden is not running for president.” Delaware’s News-Journal quoted Larry Sabato, the University of Virginia political scientist, throwing cold water on the idea. “Probably … doomed,” he said of a potential Biden bid.

But not in South Carolina, where Democrats have been clamoring for Biden to take on party standard-bearer and frontrunner Hillary Clinton. The conventional wisdom hasn’t figured in the boost a win in an early primary could give him. “The Democratic nomination for president will be decided in South Carolina,” said James Smith, a South Carolina lawmaker and key figure in Democratic circles. “There’s such an appetite for Joe—and also not Hillary. There is Clinton fatigue.”

Politically, Washington pundits have noted, Biden and Clinton agree more than not—Bernie Sanders plays a more obvious and better Clinton foil than Biden. And the vice president’s unscripted warmth is often charming, but can also produce gaffes, be accidentally offensive or lead him off-message.

Farther South, where relationships and warmth are prized, the feeling is markedly different. While Biden and Clinton are politically close, especially on domestic issues, it is Biden’s candor and loose campaign style that contrasts starkly to Clinton’s more scripted and calculated approach, Biden supporters argue.

“If he got in the race for the nomination my guess is he would win South Carolina,” said Richard Quinn, a Republican political consultant. “[Clinton’s] negatives, I’ve done polling on her, and her negatives in South Carolina are very, very high. [Biden’s] just a likeable guy. Everybody likes him. He’s personable and you don’t hear anybody say he’s a jerk.”

Quinn believes Clinton is her own worse enemy, as she continues to weather a succession of political storms. “I have learned over the years that voters have incredible intuition about a candidates veracity,” he said. “Some candidates are so good they can fake it. Bill Clinton was that good. She’s not that good.”

Biden’s office and a spokeswoman for the Clinton campaign did not return requests for comment.

Smith, the state lawmaker, has kept in regular touch with Biden, attending his annual Christmas party in the District, among other events. Like other South Carolina pols, Smith said he grew closer to Biden because of his long-held determination to ensure he grasped the world outside the D.C. bubble.

When Smith, who is in the National Guard, was deployed to Afghanistan in 2007 to lead a unit near the Pakistan border, it was Biden, then the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who checked in with him. Smith said he had the then-senator’s cell phone number and was encouraged to call.

Biden told Smith he could call a general whenever he wanted but preferred to have the on-the-ground view from the troops.

It’s a trait that Hollings, Biden’s longtime colleague in the Senate, said the presidency could use.

“He’s a wonderful fella and smart and knows everybody and speaks to Mitch McConnell,” said the 93-year-old Hollings in a recent phone interview from his office in Charleston. “He knows politics and how to work a Congress. Poor Barack doesn’t.”

No one doubts that a bid against a better-funded, better-organized Clinton would be an uphill battle in South Carolina or anywhere else. Clinton supporter Bakari Sellers, a former Democratic state lawmaker, said Clinton’s personal skills have also been underestimated. The former secretary of state is doing an increasingly good job of showcasing her personal and political skills, he said.

“We want to see the campaign ‘take the reins off Hillary’ because of the fact that she does have the ability to touch people in a very unique way,” Sellers said. “I think that will happen. It’s still early. It can’t be a repeat of 2008. It has to be a campaign centered on energy… and they’re getting there and Joe Biden is going to push them to get there a lot quicker.”

“The people who are in the inner circle are only one phone call away.”Sellers, a young, African American Democratic Party leader, said neither candidate could claim closer ties to the state’s crucial black voters, who make up the majority of Democratic voters in the state.

He said Clinton knows the potential challenge Biden poses. “The people who are in the inner circle are only one phone call away,” Sellers said of Biden.

Harpootlian, the former state party chairman, said he donated $10,000 recently to the Draft Biden super PAC, which is organizing ahead of Biden’s potential announcement. He and other supporters are assembling a list of crucial Democrats in the state who they plan to recruit. Harpootlian says he’s fielded phone calls from Democrats who have expressed support for Clinton but would switch allegiances if Biden gets in the race.

“I always liked Bill,” Harpootlian said of the Clintons. “Still like Bill. He’s got it, he gets it; I don’t think she does.”

The last Democrat to win a third presidential term for the party was Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, who succeeded himself in a historic situation amid World War II.

Harpootlian says with history stacked against any Democratic candidate, he believes Clinton is a lackluster candidate who couldn’t beat any Republican in the field, with the exception of outspoken businessman Donald Trump. Harpootlian says he’s “desperately hoping” Biden runs.

As for overcoming a better-funded candidate and a tide of doubt about the endeavor, Harpootlian has one key to a Biden victory in South Carolina. “Announce,” he said.

August 11, 2015

How Bad Is the Damage to the Animas River?

It looked Photoshopped, but it was definitely real: a river in Colorado flowed orange.

Last week, a cleanup crew from the Environmental Protection Agency working along the Animas River in southwestern Colorado accidentally broke through a dam, causing a nearby abandoned mine to spew 3 million gallons of wastewater into the river. The spill sent lead, arsenic, cadmium and other contaminants into the 126-mile-long river, turning the water a mustard hue.

The river’s appearance has since recovered; it shifted to a slight green color as water flowed away from the spill site, diluting the concentration of pollutants, CNN reported. By Tuesday, the water looked clear.

When EPA officials first measured the presence of the toxic heavy metals in river after the accident last Wednesday, the levels broke state water quality limits, The Denver Post reported.

Here’s CNN, with the token shocked scientist:

An arsenic sample tested 26 times higher than the EPA acceptable level.

Lead was even worse—much worse.

"Oh my God! Look at the lead!" said Joseph Landolph, a toxicologist at the University of Southern California, pointing to a lead level in the Animas River nearly 12,000 times higher than the acceptable level set by the EPA.

The situation seems much less dire now, according to recent tests of the river. Local drinking water is safe, but the intake valves from the river have been shut off. The state Parks and Wildlife Department reports no dead fish have been spotted along the water. Dr. Larry Wolk, Colorado’s top health official told CNN Tuesday that early tests show that the water near Durango, the Colorado city where the spill originated, “doesn’t appear” to pose a health risk, but didn’t specify to whom—humans, wildlife, local ecosystems, or all three.

The less visible—and long-term—consequences of the spill, however, are unknown, according to state and EPA officials. The flow of contaminants has already reached New Mexico, and heads to Utah next. Some of the dangerous metals may have seeped into the river’s sediment, which the current could pick up again at any time. It can take years for the effects of such contaminants to develop.

"We're kind of in a wait-and-see mode right now," Donna Spangler, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Environmental Quality, told KSL, an NBC-affiliate.

The Animas River no longer resembles something like honey Dijon, but the tests are certainly far from over.

Can Benedict Cumberbatch Save Theater From Cellphones?

As far as theater goes, the past few months could plausibly be dubbed the summer of the cellphone. In July, Patti LuPone left the stage to confiscate an audience member’s phone after a performance of Shows for Days she was starring in was interrupted four times by different ringtones. The same week, a 19-year-old student from Long Island jumped on stage during a production of Hand to God and tried to plug his charger into a non-functioning outlet that was part of the set. In April, the creator and star of Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda, called out an unnamed celebrity for attending a performance of the hit production and texting all through the second act (his co-star Jonathan Groff later revealed that the star in question was Madonna).

Related Story

Benedict Cumberbatch and the Right Way to Apologize

The latest activist in the crusade against theatrical distraction is Benedict Cumberbatch, who’s starring in a production of Hamlet at London’s Barbican Centre that rivals even Hamilton in hype. The show sold out in minutes when tickets went on sale, making it the fastest-selling production in British history, and fans have been camping outside for up to 17 hours to try and purchase the handful of daily tickets made available at 10 a.m. The popularity of Cumberbatch (and by association, the show) is in part a phenomenon of the digital age—although not conventionally handsome, the actor has become an object of Internet obsession, thanks to blogs that note his resemblance to an otter, viral videos that capture his inability to say the word “penguin,” and a widespread assumption that he is, as many websites put it, the “Internet’s boyfriend.” But he’s also an actor, and as such is now encountering the scourge of culture in a post-Android world: the inability of audiences to put their phones down at the theater.

Following early previews of Hamlet last weekend, Cumberbatch made a plea to fans camped out outside the stage door to spread the word that he doesn’t want people filming during the performance. “Can I ask you all a huge favor?” he said in an impromptu speech that was, naturally, caught on video and uploaded onto the Internet. “All of this, all these cameras, all these phones … I can see cameras, I can see red lights in the auditorium, and it may not be any of you here that did that, but it’s blindingly obvious. I could see a red light in the third row on the right, and it’s mortifying.”

Cellphones are increasingly becoming a reality that’s grudgingly tolerated at movie theaters and live music shows, but their presence during live theater is much more contentious. Almost all performances now feature pre-show pleas from ushers and recorded messages that entreat audience members to silence their phones. But the problem isn’t limited to generic ringtones that interrupt soliloquies. For an actor, seeing the blue light on an audience member’s face can be just as distracting as hearing a tinny rendition of “The Entertainer” coming from someone’s handbag. And for audience members, too, it ruins the integrity of a live performance.

“For me, a ringing phone or an LED light is akin to a usurping of the performance’s power,” says Peter Marks, the Washington Post’s theater critic. “It breaks the spell of an audience as a communal force; it says, ‘I’m more important than this experience is, and screw you if you don’t like it.’ It summons the kind of aggressive energy that is in most cases ruinous, at least momentarily, to the spirit of the piece on the stage.”

For once, this isn’t an issue that can be solely blamed on uncivil, irresponsible Millennials—while it’s usually younger audience members who text during a show, it’s almost always older theatergoers whose phones go off in the middle of a production. “One contingent is people who don’t go to the theater much,” Susan Frankel, the general manager of Circle in the Square Theater, told The New York Times in July. “But also people with babysitters home with kids they are worried about, or people who are so excited to be close to people they revere.”

For institutions, the problem isn’t as simple as escorting out audience members who flout the rules, or standing over patrons to insist that they turn off their phones. For one thing, any such intervention can often be a worse distraction than someone who’s quietly checking Twitter. And for another, theaters are engaged in a constant battle to persuade more young people to make theater a regular part of their cultural diets. Crack down too hard on offending theatergoers, and you risk alienating broader swathes of a demographic that theaters’ futures are dependent on reaching.

While theaters can certainly do more to enforce standards, perhaps the more effective policeman is the one everyone’s paid good money to see.In the U.S., the average age of a Broadway theatergoer is 44. Compare this with the U.K., where 16 to 19-year-olds are more likely to attend a theatrical performance than any other age group, and it’s obvious that American theaters are having a hard enough time engaging younger audiences without chastising them about their cellphones. Moreover, Facebook and Twitter are increasingly crucial when it comes to theaters promoting their shows: A 2010 study found that 65 percent of London theatergoers chose the shows they bought tickets for after hearing about them on social media.

Still, the solution isn’t turning a blind eye to something that can ruin a live performance for all involved. “All of it—calls, lights, texts—can muddy the experience,” says Kimberly Gilbert, an actor in Washington D.C. “What happens [in the theater] affects the journey, the art of the moment. I think it’s happening more and more because we’re more comfortable sharing our attention now between a person and a screen.” In July, LuPone released a statement saying, “I am so defeated by this issue that I seriously question whether I want to work on stage anymore.” (As The Wall Street Journal has noted, it isn’t just audiences—actors, musicians, and conductors alike tend to be as addicted to their phones as regular folk, albeit without actually taking them onstage.)

Part of the magic of live theater is that it exists in a space that is totally removed from the outside world. Constantin Stanislavski advised actors to “never come into the theater with mud on your feet … Check your little worries, squabbles, petty difficulties with your outside clothing—all the things that ruin your life and draw your attention away from your art—at the door.” For theater to be transcendent—to be the magic circle where people learn about “the brevity of human glory,” as Iris Murdoch put it—people have to commit to being fully present during a show, and to focusing all their attention on the performance at hand. Sometimes the performance in question merits such attention; sometimes it doesn’t. But the minimum required from audience members is to sit quietly and not do anything to distract actors or spectators from the action.

While theaters—and audience members, who tend to quietly tolerate bad behavior—can certainly do more to enforce standards of acceptable behavior during performances, perhaps the more effective policeman is the one everyone’s paid considerable money to see. If Taylor Swift can use her star power to coerce the most powerful technology company in the world to change its policies, maybe Benedict Cumberbatch can encourage a new kind of etiquette among rabid superfans and casual theater attendees alike.

A few years ago, when the actor Drew Cortese was performing in a play at the Shakespeare Theatre in DC, an audience member's iPod started playing music shortly into the second half of the show. After several minutes, and right before a pivotal speech, Cortese asked the audience if the person responsible wanted to turn it off. Eventually, a woman confessed that it was hers, and she didn’t know how to silence it. “The audience applauded when I got ready to resume the play, not because of how I handled that moment, but because it was so clear that we had all shared that experience together,” Cortese says.

“On the stage, an actor—especially a star—can hold incredible moral suasion,” says Marks. “Their reaction has to be commensurate with the infraction. But shaming by the person in the spotlight, of the person effectively stealing it, may be the most potent instrument of enforced decency of all.”

Could the Internet Age See Another David Foster Wallace?

Here is an extremely incomplete list of things I would like to know David Foster Wallace’s thoughts on:

selfie sticks

man buns

farmers’ markets

the Starbucks S’mores Frappuccino®

The League

professional football

college football

trigger warnings

Ferguson

media coverage of Ferguson

Netflix

Breaking Bad

Uber

Mars One

Donald Trump

Facebook

the “personal brand”

Ashley Madison

Instagram

Snapchat

the film The End of the Tour

I would especially love to know his thoughts on that last one, since the movie, being pretty much a filmic love letter to the late author, could well fall into the category of Praise That Made David Foster Wallace Itchy and Squirmy. The conventional wisdom about Wallace—an idea put forth during the nascent days of his fame, and reiterated in a good portion of the approximately 512,246 essays and novels and Tumblr posts that came as that fame crystallized into something closer to canonization—is that Wallace, the person, was extremely ambivalent about Wallace, the persona. He wanted, on the one hand, to join the ranks of DeLillo and Pynchon and Updike (though the latter he famously denigrated as “just a penis with a thesaurus”). But the fame that accompanied literary achievement during the time he was doing all his achieving made him, he insisted, “want to become a recluse.” There’s being celebrated, and then there’s celebrity. Celebrity, in all its tentacular forms, was one of the things Wallace’s work most consistently mocked.

Related Story

David Foster Wallace: Genius, Fabulist, Would-Be Murderer

And so, after Infinite Jest came out to effusive acclaim (the book so surpassed its peers, Walter Kirn wrote, effusively, it was as though “Paul Bunyan had joined the NFL, or Wittgenstein had gone on Jeopardy!”), Wallace began changing his phone number every few months, to prevent unsolicited calls from fawning fans. He began making restaurant reservations under fanciful pseudonyms. He made a performance of his ambivalence. When a friend wrote to congratulate actual-Wallace on Infinite Jest's success, the writer replied, “WAY MORE FUSS ABOUT THIS BOOK THAN I’D ANTICIPATED. ABOUT 26% OF FUSS IS WELCOME.”

The irony in all this—and there are always a kind of parfait of irony where David Foster Wallace is concerned—is that Wallace’s protestations against the fuss ended up serving to justify the fuss. Wallace the World-Weary Celebrity became a trope in the literary subgenre of writing-about-Wallace not just because it was partially true, but because it lent a kind of ethical tolerability to fame’s economic transactions: He deserved his celebrity, the logic went, specifically because he had not sought it.

There’s a scene in a New York Times profile of Wallace, published during the Infinite Jest tour, in which Wallace, eating a bologna sandwich, is orally accosted by his two rambunctious dogs. “They pretend they’re kissing you,” Wallace tells the journalist Frank Bruni, “but they're really mining your mouth for food.” This is disgusting and elegant and, as such, a perfect metaphor for the slobberingly ravenous demands the public can place on the people it patronizes. It suggests that Wallace, who was above all a media critic, understood that you can’t have the “celebrity” without the “sell.” But it also suggests the divide between Wallace and the people who hunger for and around him—that Wallace, even as he was a part of his own fame, was somehow detached from it. And somehow above it.

The End of the Tour manages both to reiterate the old trope and to ignore it. The movie portrays Wallace as genuinely conflicted about his fame, resisting what actual-Wallace called “the big Attention eyeball” and what movie-Wallace calls “being a whore,” but it also finds him book-touring and radio-interviewing and, of course, agreeing to the epic Rolling Stone interview that the movie is based on. It also, however, engages in the kind of postmodern hagiography that treats its subject’s averageness—in this case, Wallace’s love of Alanis Morissette, his penchant for candy bars, his reliance on Clearasil, his obsession with TV and movies and malls and McDonald’s value meals—as a primary source of his heroism.

So Wallace—itch, squirm—has been casually canonized, turned into what he once dubbed, disapprovingly, “a Mask, a Public Self, False Self or Object-Cathect.” He has been transformed from David Foster Wallace, the author and human (the “Foster” Wallace added at the suggestion of an editor, to distinguish him from the many already-famous people who shared his name), into “DFW,” the literary symbol and Lifestyle Brand. Wallace, Jason Segel, who plays him in The End of the Tour, told me, was not just “a dude”; he is also one of those celebrities who we want—and in some sense need—to idolize. “You want to deify them,” Segel says. “You want them to be something other than you.”

Wallace—itch, squirm—has been casually canonized, turned into what he once dubbed “a Mask, a Public Self, False Self or Object-Cathect.”So when movie-Wallace chides movie-journalist David Lipsky (Jesse Eisenberg) to “just be a good guy,” there’s a moral valence to the goodness. There’s a sense that Wallace knew, as a function of his sweeping intellect and his gentle genius, better than the rest of us what “goodness” entails.

But Wallace himself, it’s worth noting, was not always a good guy. He told a men’s group he was involved in that he looked at getting women into bed as “a physics problem,” and once wondered to a friend whether his purpose was simply “to put my penis in as many vaginas as possible.” He once threatened, his biographer D.T. Max writes, to murder the husband of a love interest, The Liar's Club author Mary Karr; he also, Max alleges, once pushed Karr from a vehicle and, during another fight, threw a coffee table at her. He could be self-absorbed (“I’m massively selfish about my work,” Wallace told Bruni in the Times profile, “and I don't seem to be able to be very polite or considerate about other people's feelings”). He could be deceptive (he blamed a year he took away from college on the suicide of a friend when, in reality, it was his depression—which he variously described as “the black hole with teeth” and “the festering pus-ridden chancre at the center of my brain” and “the Bad Thing”—that had kept him away). As Wallace himself summed it up in a 1999 interview: “I could be a prick.”

These are human shortcomings, the kind any human, marred and messy, will relate to; the thing is, though, that the Wallace Industrial Complex doesn’t tend to allow them to color the man who is its principal and its principal product. #Brands don’t tend to appreciate the nuance of banality. “Something I’ve noticed since Wallace’s suicide in 2008,” Glenn Kenny wrote in The Guardian, on the occasion of the End of the Tour release, “is that a lot of self-professed David Foster Wallace fans don’t have much use for people who actually knew the guy. For instance, whenever Jonathan Franzen utters or publishes some pained but unsparing observations about his late friend, Wallace’s fan base recoils, posting comments on the Internet about how self-serving he is, or how he really didn’t ‘get’ Wallace.”

* * *

Wallace died before Facebook went mass-market, before Twitter exploded onto the scene, before the web came, fully, to saturate our habits of life and social interactions. Could the kind of transcendent celebrity he both enjoyed and resented have survived life on the Internet? Could Wallace, had he lived on into the brave new world of Facebook and Twitter and small pieces loosely joined, kept his carefully calibrated mask intact? Would his cult have been able to continue as it has in a world of sound bites and personal brands and #hottakes, a world in which the demands on an author are so much more constant and insistent than book tours and occasional TV interviews?

It’s hard—strictly, it’s impossible—to tell. Wallace was deeply suspicious of the media infrastructure that was, when he died, still largely known as “the Net”—“I allow myself to Webulize only once a week now,” he once told a grad student—and he remarked to his wife, as they were moving computer equipment into their house, “thank God I wasn't raised in this era.” Having written his first big stories on a Smith Corona typewriter, Wallace disliked digital drafts and e-publishing in general. (“Digital=abstract=sterile, somehow,” he wrote to Don DeLillo in 2000.) He liked to write long-hand, usually with cheap Bics he nicknamed his “orgasm pens.” He took particular pleasure in the fact that his house in Indiana, the one recreated in The End of the Tour, had the elegantly atavistic address of “Rural Route 2.” He preferred to file his students’ work not on computers, but in a pink Care Bears folder.

And he insisted that Infinite Jest, for all its obsession with commercialized communication and connection, was not about the web. When Valerie Stivers asked Wallace why the novel didn't specifically mention “online services,” he replied that “to do a comprehensive picture of what the technology of that era would be like, would take 3,500 pages, number one.” And when the Chicago Tribune asked whether Infinite Jest was meant to reflect life in the Internet age, the author rejected the reading. “This is sort of what it's like to be alive,” Wallace insisted. And “you don't have to be on the Internet for life to feel this way.” (Another reading, however: “The book is not about electronic culture,” Sven Birkerts, writing in the magazine then known as The Atlantic Monthly, noted, “but it has internalized some of the decentering energies that computer technologies have released into our midst.”)

And yet who better than Wallace to comment on the crazy world that is springing up both on and around the web? Who better than Wallace to help us make sense of Google and Snapchat and the far-reaching sociological experiment that is being conduced under the auspices of the “selfie stick”? Not only, as Maud Newton noted in a 2011 essay, has his writing style—its flippancy and its formality and its word-invention and its run-on sentences and its aggression and its passivity and its indolence and its urgency and its Ironical Creation of Capitalized Categories and its philosophy and its whimsy—been dissolved into a generation of Internet writers; his philosophical preoccupations also lend themselves to the Internet as a medium. Wallace seemed to have had a kind of preternatural (savant-garde, he might have called it) appreciation of what the web would bring as it made its way from “invention” to “infrastructure.” As he told Lipsky in Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, referencing the web-service-esque InterLace Grid from Infinite Jest,

… This idea that the Internet’s gonna become incredibly democratic? I mean, if you’ve spent any time on the Web, you know that it’s not gonna be, because that’s completely overwhelming. There are four trillion bits coming at you, 99 percent of them are shit, and it’s too much work to do triage to decide.

So it’s very clearly, very soon there’s gonna be an economic niche opening up for gatekeepers. You know? Or, what do you call them, Wells, or various nexes. Not just of interest but of quality. And then things get real interesting. And we will beg for those things to be there. Because otherwise we’re gonna spend 95 percent of our time body-surfing through shit that every joker in his basement—who’s not a pro, like you were talking about last night. I tell you, there’s no single more interesting time to be alive on the planet Earth than in the next twenty years. It’s gonna be—you’re gonna get to watch all of human history played out again real quickly.

What Wallace didn’t say, but what may well prove true, is that the overload he’s describing may come to apply to people as well as information. The Internet is composed, Soylent Green-style, of people—formerly atomized humans who, through their updates and posts and curiosities and contributions and selfies, are transforming themselves into media. We are just now figuring out what that might mean when it comes to the interplay of commercialism and human connection—the relationship that preoccupied Wallace in his writing. And authors, from Jonathan Franzen to Margaret Atwood to Joyce Carol Oates, are doing that figuring, too. As Meghan Tifft put it recently, discussing the demands on the writer to be introverted and extroverted at the same time, the writer is expected to engage in a “variety show of readings, interviews, conferences, and Q&As”—not just as a way of finding commercial viability, but as “a way of talking back, creating and sustaining a community around writing that matters.”

What this means is that we, the public, have access to our authors—as people, rather than personas—in ways we never did before. What is also means is that we are, more often than we were before, confronted with their humanity. Or, put less sweepingly, with their banality. (“Literary Legends: They’re Just Like Us.”) We see them engaging in hashtagged political causes; we see them fighting with other writers. We see them battling writers’ block. We see them being … them.

That could be a very minor thing, or it could be a very major one. We have gone, after all, through much of human history celebrating people not for who they were, but for what they accomplished and contributed: Darwin’s theory. Newton’s law. And that has meant that we have tended to prioritize the things people contributed over the kinds of people they were. Was Shakespeare kind of a douche? Was Jane Austen sort of awkward? Was Wittgenstein a total delight at dinner parties?

We don’t know, really. But that is, perhaps, simply an accident of history. Being an author in the age of Facebook and Twitter and Tumblr might mean something very different from what being an author meant in, and to, previous eras—something more conversational, more collaborative, more communal. The death of the author, if you buy into that stuff, may be giving way to something at once more hopeful and more sad: the diffusion of the author. The treatment of the author as someone to be, in every sense, “gotten.” The kind of detached sanctification alternately enjoyed and resented by David Foster Wallace—DFW to those in the know—may no longer be possible in an age that insists that its authors be that most brilliant and boring of things: human.

What the Iran-Deal Debate Is Like in Iran

The nuclear deal with Iran has sparked a vigorous debate not only in the United States, but in Iran as well. The discussion of the agreement among Iranians at times echoes the American discussion, but is also much deeper and wider. Reports in Iranian media, as well as our own correspondence and conversations with dozens of Iranians, both in the country and in exile, reveal a public dialogue that stretches beyond the details of the agreement to include the very future of Iran. And it seems that everyone from the supreme leader to the Iranian American executive in Silicon Valley, from the taxi driver in Isfahan to the dissident from Evin Prison, is engaged. The coalitions for and against the deal tend to correlate closely with those for and against internal political reform and normalized relations with the West.

The mere fact that there is such a debate says something about the nature of the Islamic Republic of Iran today. Iran is a dictatorship. One man, the supreme leader, has most of the power. He is the commander in chief and thus formally controls the military, the very powerful internal militia, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and its external wing, the Quds Force. The supreme leader appoints the head of the judiciary, the head of the Iranian national radio and television organization, and most of the National Security Council—an advisory body similar to the U.S. National Security Council. He also controls tens of billions of dollars in revenues from religious endowments and foundations. And, as stated in the constitution, he is the spiritual leader of the country, combining religious and political power in one office.

Related Story

And yet, nowadays the supreme leader does not decide everything on his own. Some formal institutions of the Iranian regime, and a myriad of informal interest-group networks, also play a role in shaping policy, including on the nuclear deal. Most importantly, the Iranian president has some political autonomy. Through his control of the Guardian Council—a committee of 12 men that among other things must approve every candidate wishing to run for elective office—the supreme leader decides who is allowed to run for president. But once the list of candidates is determined, the vote is usually competitive, giving the chief executive an electoral mandate directly from the people. In the last presidential election, candidates ideologically closest to the supreme leader garnered only a few million votes, while the one candidate running as a reformer, Hassan Rouhani, received more than 18 million votes. Rouhani’s wide margin of victory strengthened his position as a partially independent actor within the Iranian regime.

In addition to the president, other groups have obtained some political autonomy within Iran’s fractured authoritarianism. Civil society is constrained but still fighting. A vibrant underground of publishing, theater, music, and poetry continues to spread. Divides exist even among the clerics. Conservatives still dominate, but several top clerics have voiced their support for Iran’s reformist forces and criticized—sometimes openly, sometimes more discreetly—conservative policies. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s own brother, Hadi Khamenei, recently described the eight-year presidency of Rouhani’s predecessor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as some of the “darkest [years] in the history of the country,” adding that the conservatives are trying to “give a bad image to the reformists.” This political system—authoritarian but with pockets of pluralism—has created the relatively permissive conditions for a serious, public debate about the nuclear deal.

Moreover, in refraining from taking a firm public position for or against the agreement, Khamenei himself has encouraged this debate. Given the extent of Khamenei’s control, the Iranian negotiators could not have signed the accord without his approval. In public, however, the supreme leader has refrained from praising the work of his negotiating team, saying only that the deal must be ratified through the proper “legal channels” and will not change Iranian policy toward the “arrogant U.S. government.” Khamenei’s mixed signals have allowed others to speak out more forcefully on the nuclear pact.

Rouhani crushed his conservative opponents in the 2013 presidential election in part because he advocated for a nuclear deal. This agreement is his Obamacare.Those supporting the deal include moderates inside the government, many opposition leaders, a majority of Iranian citizens, and many in the Iranian American diaspora—a disparate group that has rarely agreed on anything until now.

First and most obviously, the moderates within the regime, including Rouhani and his close friend and political ally, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, negotiated the agreement, and are now the most vocal in defending it against Iranian hawks. Rouhani crushed his conservative opponents in the last presidential election in 2013 in part because he advocated for a nuclear deal. This agreement is his Obamacare—his major campaign promise now delivered. Former Presidents Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami, as well as moderates in the parliament and elsewhere in government, have also vigorously endorsed the accord. During the negotiations, Rafsanjani, for example, celebrated the fact that Iran’s leaders had “broken a taboo” in talking directly to the United States. Since the agreement was signed, he has said that those within Iran who oppose it are “making a mistake.”

Second and somewhat surprisingly, many prominent opposition leaders also support the deal. Mir-Hossein Mousavi, a popular presidential candidate in 2009 who is now under house arrest for his leadership of the Green Movement protests against Ahmadinejad’s reelection, backed the pursuit of the agreement, albeit with some qualifications. He’s joined by other government critics, some only recently released from Iran’s prisons. Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian human-rights activist and Nobel laureate now living in exile, expressed the hope after an interim agreement was reached in April that “negotiations come to a conclusion, because the sanctions have made the people poorer”; she labeled as “extremists” those who opposed the agreement in Iran and America. Akbar Ganji, an Iranian journalist who spent more than six years in prison in Iran, also praised the agreement, writing that “step-by-step nuclear accords, the lifting of economic sanctions and the improvement of the relations between Iran and Western powers will gradually remove the warlike and securitized environment from Iran.”

Polls show that most Iranians agree with these positions, and public opinion is apparent not just in the Iranian government’s numbers but also in the results of earlier surveys conducted by the University of Maryland and Tehran University. The sentiments of many ordinary Iranians were manifest in the spontaneous demonstrations of joy that took place in many Iranian cities after the agreement was announced.

If the deal represents Iran’s reengagement with the world—more trade, more investment, more travel, more normalcy—all of these trends would undermine the theocracy.A new poll also shows that two-thirds of Iranian Americans favor the agreement, and our own conversations with members of the Iranian diaspora bear this out. The Islamic Republic has long enjoyed some defense from a handful of non-governmental organizations in the West, but support for the nuclear deal stretches much deeper into the diaspora and includes many who despise Tehran’s theocracy. For instance, many prominent Iranian American business leaders have told us they approve of the accord. Iranian American foundations and community-service organizations have issued statements backing the deal, while also calling for renewed focus on political reforms inside Iran. Even many of those who had to flee the country after the revolution, and have since helped fund projects to encourage democracy inside Iran (including, in the past, our own Iran Democracy Project at Stanford’s Hoover Institution), support it. There are exceptions. Some in the diaspora still believe that only more pressure, and if need be a military attack, will bring down the Islamic Republic. But the number of Iranian Americans who are at once critical of the regime and supportive of the nuclear deal is striking.

This coalition has multiple motivations for favoring the deal. A number of Iranians simply want sanctions lifted. Some moderates within the regime may want to reduce international pressure on Iran as a means to preserve the power structure. And it’s safe to assume that a few Iranian American business leaders see new trade opportunities in the diplomatic achievement. But the agreement could also serve as a first step in alleviating the problems of ordinary Iranian citizens. If the deal represents the beginning of Iran’s reengagement with the outside world—more trade, more investment, more space inside Iran for the private sector, more travel, more normalcy—all of these trends would undermine the ideological, emotional, and irrational impulses of the theocracy. Especially in the context of an aging supreme leader, a newly elected reformist president, and a young, post-revolutionary population, the nuclear deal offers an opportunity for Iran to modernize politically and economically. Even dissidents sitting in jail or exile have expressed these views. Ganji, for instance, argued that “if there are friendly relations between Iran and Western powers, led by the United States, the West will be able to exert more positive influence on Iran to improve its state of human rights.” Conversely, members of this coalition have voiced fears that a collapse of the deal would only reaffirm the United States as the enemy of Iran—the Great Satan—and thereby strengthen the hardliners internally. Issa Saharkhiz, a journalist who spent four years in prison, recently warned that such a collapse could bring “Iranian versions of ISIS”—a reference to Shiite conservatives and their militant allies—to power in the country.

And that’s exactly why the most militantly authoritarian, conservative, and anti-Western leaders and groups within Iran oppose the deal. This coalition is formidable, and includes former President Ahmadinejad, the Iranian leader who denied the Holocaust and called for the elimination of Israel. Fereydoon Abbasi, who directed Iran’s nuclear program under Ahmadinejad, and Saeed Jalili, the former nuclear negotiator, have repeatedly sniped at the deal. In a biting interview, Abbasi ripped into every facet of the talks, saying that the negotiators, “especially Mr. Rouhani ... have accepted the premise that [Iran] is guilty.” Several conservative clerics and IRGC commanders have expressed similar sentiments. One prominent critic of the deal claimed that of the 19 redlines stipulated by the supreme leader, 18 and a half had been compromised in the current agreement. Many publications considered close to Khamenei—including most noticeably the daily paper Kayhan—have been unsparing in their criticism.

Celebrations in Tehran after the nuclear deal was announced (Ebrahim Noroozi / AP)

Celebrations in Tehran after the nuclear deal was announced (Ebrahim Noroozi / AP) Conservative opponents of the deal tend to emphasize its near-term negative security consequences. They point out that the agreement will roll back Iran’s nuclear program, which was intended to deter an American or Israeli attack, and thereby increase Iran’s vulnerability. They have denounced the system for inspecting Iranian nuclear facilities as an intelligence bonanza for the CIA. And they have issued blistering attacks on the incompetence of Iran’s negotiating team, claiming that negotiators caved on many key issues and were outmaneuvered by more clever and sinister American diplomats.

And yet such antagonism appears to be about more than the agreement’s clauses and annexes. The deal’s hardline adversaries also seem concerned about the same longer-term consequences that the moderates embrace. For instance, IRGC leaders must worry that a lifting of sanctions will undermine their business arrangements for contraband trade. In a not-too-discreet reference to these concerns, Rouhani declared them to be “peddlers of sanctions,” adding that “they are angry at the agreement” while the people of Iran pay the price for their profiteering. Over time, more exposure to the wider world of commerce is likely to diminish if not destroy the IRGC’s lucrative no-bid government contracts for infrastructure and construction projects.

Perhaps more threatening for this coalition is the loss of America as a scapegoat for all domestic problems. The conservatives need an external enemy to excuse their corrupt, inefficient, and repressive rule. Some have even suggested that the United States is trying to do to Iran what it did to the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev foolishly trusted U.S. President Ronald Reagan and sought closer ties with the West. The result was the collapse of the Soviet regime. In a remarkable letter from Evin Prison written after the nuclear deal was announced, Mustafa Tajzadeh, once an influential deputy minister of interior during the Khatami administration and now a defiant dissident behind bars, criticized the leader of the conservative faction in Iran’s parliament, who had openly warned against the danger of a ratified nuclear deal as a prologue to a more dangerous domestic challenge from democratic forces. Foreign crises, the conservative parliamentarian had opined in a statement, are “easier to manage.”