Robert B. Mitchell's Blog, page 3

April 26, 2024

Harnessing “the priceless boon” of community

One of my favorite scenes in The Searchers involves a moment that seems almost unimaginable today.

The arrival of Texas Ranger Charlie McCorry at the Jorgensen homestead in west Texas is treated in the classic 1956 John Ford film as a great occasion – because he brought a letter.

Lars Jorgensen hovers over his daughter as she reads. He plucks the missive from the fire after she angrily wads it up and hurls it into the flames. A letter – the second of the year, Jorgensen marvels – was too precious to simply discard.

Part of Ford’s genius was his gift for illuminating aspects of daily life in the 19th-century American west. Perhaps no feature of existence from that century is harder to imagine in our digitized world than the extreme loneliness endured by families eking out a new existence on farms and ranches throughout the country.

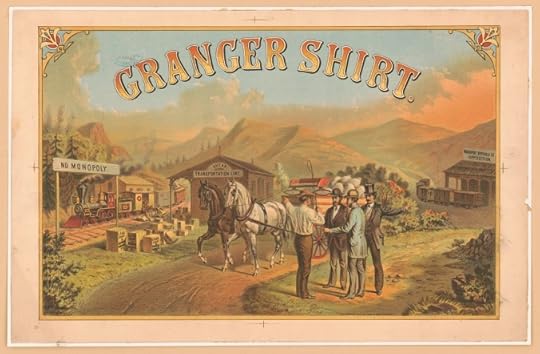

Grange recruiting poster. Library of Congress.

When the family of James B. Weaver left its homestead in southern Iowa in the 1840s and settled in what would become the county seat town of Bloomfield, the gregarious Iowan rejoiced. It was a “priceless boon” to have the chance to visit neighbors and talk to them, Weaver recalled. “Our home life was more varied as we met our neighbors with greater frequency.”

Isolation was psychologically devastating. Defeating it would yield significant rewards.

Among the first to understand this were Methodist preachers who convened summer camp meeting at which families would stay for days to worship, sing and celebrate with their neighbors. The first camp meeting was probably held in Logan County, Ky., in 1800, according to a blog post for the United Methodist Church by Joe Iovino. In the decades that followed, camp meetings were held across the Old Northwest and in the territories – such as Iowa – across the Mississippi.

“In them,” according to an entry in the Encyclopedia of World Methodism, “multitudes were converted.”

In Davis County, Iowa, Cumberland Presbyterians (the denomination that would claim William Jennings Bryan as one of its own) held camp meetings, but the Methodists pioneered the event, according to Henry C. Ethell’s history of the county’s early days. “Cloth tents or board houses were ranged round a large square, seated with slabs or thick planks. Families living several miles away came and lived in these tents throughout the meeting. A Sunday congregation would often number three of four thousand,” Ethell wrote.

The grandson of an Iowa Methodist, the Rev. Francis Carey, offered an account of how camp meetings worked in the Pioneer History of Davis County. The meeting included the famous Iowa Methodist pastor Henry Clay Dean, who preached two sermons – the first failing to move his listeners. But the second did not disappoint. “The people were completely overcome,” Carey’s grandson wrote, “and many in the multitude, weeping and sobbing, embraced the church that evening.”

Weaver fondly remembered the visits of circuit-riding Methodist pastors who stopped at isolated farms to minister to families who could not attend church.

Through these forms of evangelism, the Methodists gained a foothold on the frontier that would help make the denomination one of the most influential in the United States in the 19th century.

In the years after the Civil War, a secular group formed to overcome the isolation of the farmstead rose to power and prominence. The Patrons of Husbandry, widely known as “the Grange,” spread like wildfire across the Old Northwest and the Upper South.

Its purpose was, in theory, apolitical. The founders of the Grange envisioned a secret society much like the Masons in which elaborate ritual played a central role. “Although the original idea of the founders appears to have been that the benefits of the order to its members would be primarily social and intellectual, it very soon became apparent that the desire for financial advantages would prove a far greater incentive for the farmers to join,” Solon Justus Buck wrote in his history of the Grange.

Buck writes that Granger efforts were initially directed at cooperative schemes aimed at lowering production costs for members – buying supplies and insurance – and maximizing profits on commodity sales. Another concern soon converted the Grange from an apolitical society for farmers into a potent force in American politics.

Growing discontent with railroad business practices and political clout alarmed farmers who saw the promises of access to distant markets for their products evaporate due to high – and often seemingly arbitrary – freight rates. Attempts in state legislatures to address this issue by regulating rates began as early as the late 1850s but went nowhere. The Grange offered a means for farmers to organize themselves politically to press their case for railroad regulation.

Washington took notice as Grange lodges proliferated across the Old Northwest. “The movement of the western people against the great railroad monopolies begins to assume definite shape,” the Washington Evening Star noted in its editorial column on Feb. 20, 1873. The newspaper predicted that “it is pretty certain that the control of railroad fares and freight will be the issue on which the next legislatures of several of the western states will be chosen.”

Anti-railroad sentiment did indeed emerge as a prominent issue in the off-year elections of 1873. State Republican platforms throughout the Old Northwest called for “cheap transportation” and denounced railroad business practices. Anti-Monopoly candidates swept to victory in Iowa and elsewhere. Granger William R. Taylor defeated Republican Gov. C.C. Washburn in his bid for re-election despite Washburn’s record as a critic of railroad business practices.

In the late 1880s, another farmer’s movement followed the trail blazed by the Grangers. The National Farmers Alliance & Industrial Union advocated an explicitly political program that called for, among other things, government control of the railroads, Robert C. McMath Jr. writes in his history of populism. Like the Grangers, the Alliance featured its own passwords and rituals, McMath notes – including burial services.

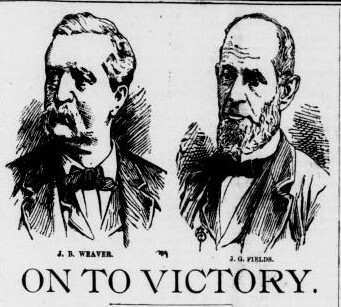

The movement spread across the Plains and the South with rallies that McMath likened to camp meetings. In 1892, it morphed into a political party – the People’s Party, commonly referred to today as the Populists – with Weaver at its head. Weaver carried four states in that year, running against Grover Cleveland and President Benjamin Harrison.

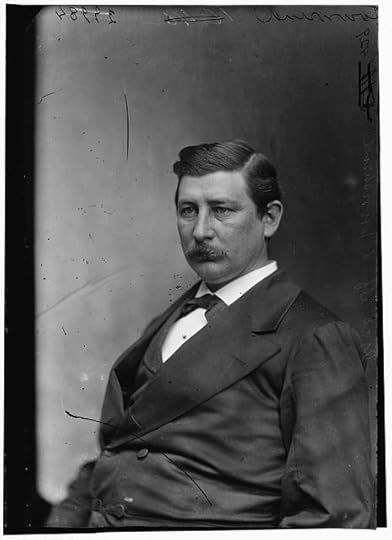

James B. Weaver and his running mate, J.G. Fields. Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

The conversion from social organization to political party, however, did not end well. In 1896, Populists put Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan at the top of their ticket – a move backed by pragmatists like Weaver but which spelled the end of the party as an effective third force in American politics. Weaver, who had broken with the Republicans in 1877 and spent the next two decades in the ranks of the Greenback-Labor and Populist parties – eventually joined the Democrats.

Nevertheless, the populist movement enjoyed its moment in the sun in large part because it brought farmers together to work for a common goal. It merged politics and social engagement and tapped into what historian Joseph F. Wall identified as the farmer’s delight in meeting with others. “He is an individualist who enjoys working in the fields alone, but he also craves company,” Wall wrote of the prototypical farmer in his bicentennial history of Iowa. “Most farm organizations from the National Grange to the Farm Bureau were initially inspired by the farmer’s desire for some kind of social communication and an opportunity for an interchange of new ideas.”

Lars Jorgensen would have appreciated that.

———————-

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

C ongress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

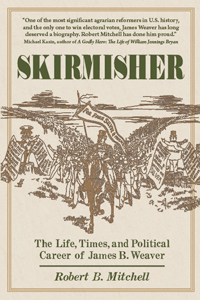

Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver

April 16, 2024

A Strife of Interests

This blog began about nine years ago as my book on the Credit Mobilier scandal, Congress and the King of Frauds, was published. At the time, “King of Frauds” seemed to be the appropriate title. Over time the blog took on a logic of its own and was no longer narrowly focused on Oakes Ames, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the scandal that rocked Washington in the winter of 1872-1873.

With another book set to appear later this year — this one on the rivalry between James G. Blaine of Maine and Roscoe Conkling of New York — it is time to rechristen the blog. I’ve decided to call it “A Strife of Interests.” The url, kingoffrauds.wordpress.com, will remain the same.

For the title I have borrowed from The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce’s delightful lexicon of words and phrases compiled in book form in 1906. It comes from his definition of politics: “A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.”

In full, the definition reflects Bierce’s deep-seated cynicism, but the phrase “strife of interests” speaks to what makes the Gilded Age so interesting to me. Americans were working out what their world would be like in the years after the Civil War. Strife abounded — in the South, the West, and the industrial urban North. The politics of the period — its personalities, its scandals, its language — reflected the tumultuous, wrenching evolution of modern America between 1865 and 1900.

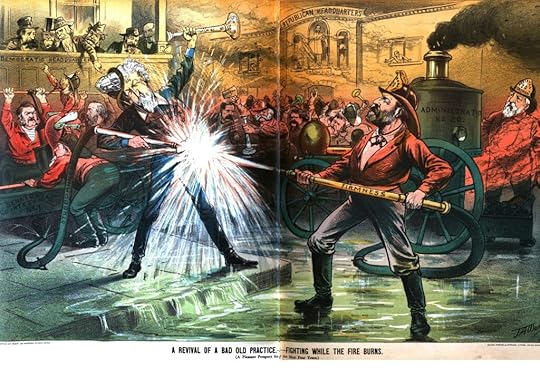

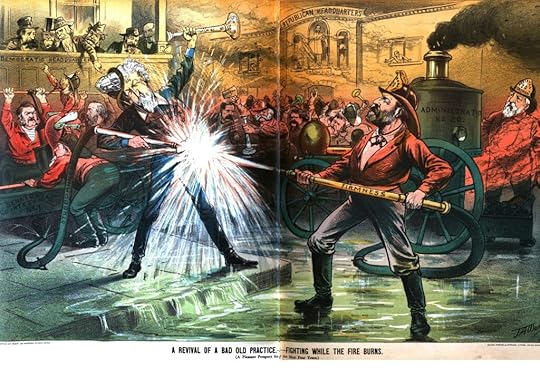

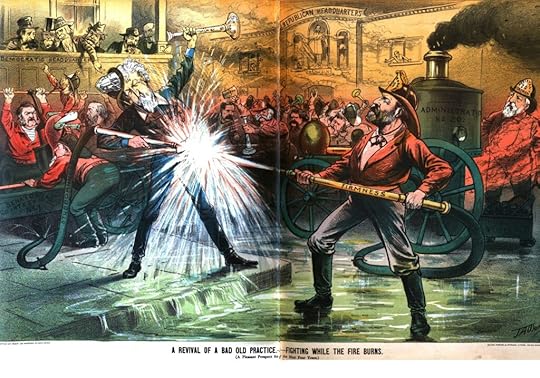

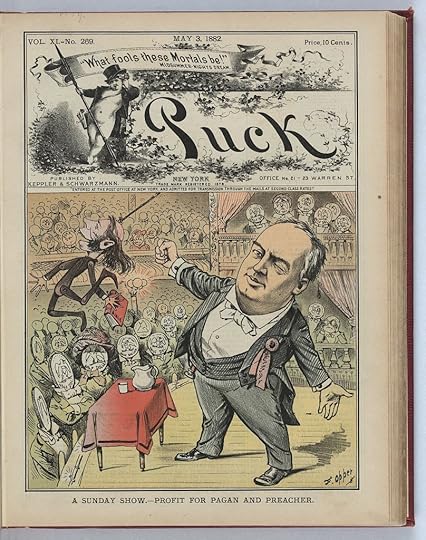

The illustration replacing the New York Sun headline over its scoop about Credit Mobilier comes from Puck. It shows President James A. Garfield directing a fire hose at Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican machine. Managing the water pump in the background is Blaine, Conkling’s nemesis.

Changing Names

I’ve dropped “King of Frauds” as the name of this blog and replaced it with “A Strife of Interests.”

This blog began about nine years ago as my book on the Credit Mobilier scandal, Congress and the King of Frauds, was published. Over time the blog took on a logic of its own and was no longer narrowly focused on Oakes Ames, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the scandal that rocked Washington in the winter of 1872-1873.

With another book set to appear later this year — this one on the rivalry between James G. Blaine of Maine and Roscoe Conkling of New York — it is time to rechristen the blog. The url, kingoffrauds.wordpress.com, will remain the same.

For the title I have borrowed from The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce’s delightful lexicon of words and phrases compiled in book form in 1906. It comes from his definition of politics: “A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.”

In full, the definition reflects Bierce’s deep-seated cynicism, but the phrase “strife of interests” speaks to what makes the Gilded Age so interesting to me. Americans were working out what their world would be like in the years after the Civil War. Strife abounded — in the South, the West, and the industrial urban North. The politics of the period — its personalities, its scandals, its language — reflected the tumultuous, wrenching evolution of modern America between 1865 and 1900.

The illustration replacing the New York Sun headline over its scoop about Credit Mobilier comes from Puck. It shows President James A. Garfield directing a fire hose at Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican machine. Managing the water pump in the background is Blaine, Conkling’s nemesis.

April 3, 2024

Conkling, Grant, and the “famous apple tree” of Appomattox

The back story of Roscoe Conkling’s nomination speech for Ulysses S. Grant at the 1880 Republican convention in Chicago.

Roscoe Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican Party, arrived in Chicago in the spring of 1880 to lead the effort to make Union war hero and former president Ulysses S. Grant the party’s nominee.

Tall, handsome, and a flamboyant dresser with a distinctive Hyperion curl falling across his brow, Conkling became an object of public fascination as the Republican convention began on June 2 at the Interstate Industrial Exposition Center on Michigan Avenue. “He cannot pass through a hotel corridor without drawing a number of people in his wake,” the New York Tribune reported. When he sat down to breakfast, crowds gawked until they were turned away by the head waiter. “Mr. Conkling seats himself,” the Tribune continued, “and his striking face crowned with hair something between auburn and white, with a complexion that may be called vivid whiteness, and a short-pointed auburn beard, becomes henceforth the great Grant landmark of the convention.”

Grant had been nominated by acclamation in 1868 and 1872, but this time he faced competition as he sought an unprecedented third term in the White House. His leading opponent — and Conkling’s arch-rival — was James G. Blaine, who along with Conkling had been defeated for the party’s nomination four years earlier when Republicans meeting in Cincinnati selected Rutherford B. Hayes as their candidate.

Despite his celebrity status, the “Great Grant landmark” antagonized the convention shortly after it opened when he demanded the expulsion of three West Virginia delegates who opposed his resolution committing delegates to support the eventual nominee. The ham-handed move enabled James A. Garfield to win admirers by defending the West Virginia delegates and signaled that the autocratic manner in which Conkling ran the Republican Party in New York would not play well on the convention floor.

But Conkling still commanded the attention — if not the affection — of the delegates. And when it came time to nominate Grant, Conkling displayed the theatrical instinct that had served him so well on the campaign trail in New York and on Capitol Hill.

“As Conkling marched to the front, erect and confident, his form towering head and shoulders above most other men around him, his splendid presence seemed to confirm reports of his power,” Iowa historian and journalist Johnson Brigham would recall years later. “A flatteringly long ovation awaited him.”

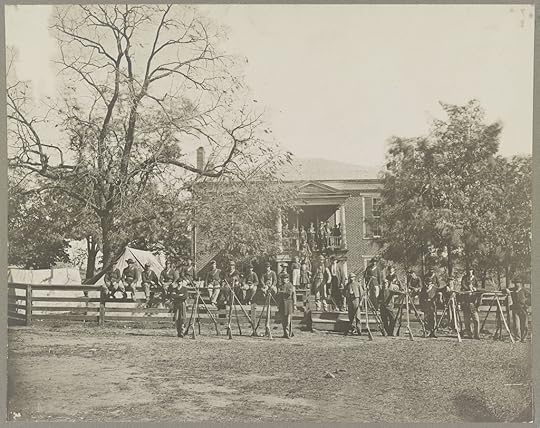

Appomattox Court House, 1865. Library of Congress.

Appomattox Court House, 1865. Library of Congress.He climbed atop a table used by reporters. “It was the most conspicuous elevation in the hall,” according to the New York Sun. Conkling “bowed to all points of the compass, and saluted a friend in the gallery.”

He began by making an unorthodox rhetorical decision. In his book on Gilded Age politics, journalist Joseph Bucklin Bishop noted that the original text of the speech, distributed to newspapers in advance and widely reprinted, begins with the simple declaration: “When asked whence comes our candidate, we say from Appomattox.”

Perhaps encouraged by the enthusiastic welcome he received, Conkling “took the bold hazard of springing on his hearers a climax at the very outset,” Brigham recalled. Instead of an unadorned reference to the site of the Confederate surrender that ended the Civil War, Conkling began with a short piece of verse: “When asked from state he hails from, our sole reply will be/He hails from Appomattox, and its famous apple tree.”

The couplet was familiar to Republicans. It came from a campaign song penned for Grant’s 1868 presidential campaign by Charles G. Halpine, better known by the non de plume Miles O’Reilly.

Like a delayed fuse, Conkling’s rhetorical gambit did not trigger an immediate reaction, but it eventually rocked the hall. “At first the few applauded, but when the Grant delegates grasped the significance of the lines, they rose and made one of the most genuinely spontaneous demonstrations of the convention,” Brigham recalled.

Much of Conkling’s speech was an eloquent paean to Grant. “Never defeated, in peace or in war, his name is the most illustrious borne by living man,” Conkling declared. “His services attest to his greatness, and the country — nay, the world — knows them by heart.”

As president, Grant “cleared the way” for a return to the gold standard with his veto of the inflation bill in 1874, Conkling claimed. The veto divided Republicans at the time, but by 1880 it looked farsighted (although controversy over monetary policy would return with a vengeance a decade later). Because of Grant, Conkling told the convention, “every paper dollar is at last as good as gold.”

“Life, liberty, and property will find a safeguard with him,” Conkling continued. Grant’s return to the White House would mean Black Southerners “would no longer be driven in terror from the homes of their childhood and the graves of their murdered dead.” When Grant spurned a chance to meet with Dennis Kearney, the Sinophobic leader of the Workingman’s Party in San Francisco, “he meant that communism, lawlessness, and disorder, although it might stalk high-headed and dictate law to a whole city, would always find a foe in him.”

With many Republicans opposed to Grant’s nomination on the grounds that it would break the two-term tradition, Conkling addressed the issue directly. Barring a successful president from returning to office after two terms would “dumbfounder Solomon, because Solomon thought there was nothing new under the sun.” It makes no sense to deny a third term to a successful president who has served eight years in office, Conkling argued. “Show me a better name,” Conkling dared Grant’s critics. “Name one, and I am answered. But do not point as a disqualification to the very experience which makes this man fit beyond all others.”

Conkling’s eloquent affirmative case for Grant helped make the speech one of the most memorable political orations of the Gilded Age. “Next to the speech of [Robert] Ingersoll, who nominated Blaine in 1876, Conkling’s appeal for the nomination of Grant will stand as the ablest of all the many able deliverances in the history of American politics,” journalist A.K. McClure declared. If he had stopped there, Conkling might have united the party, McClure believed. But the New Yorker, whose enmity toward Blaine dated back to an exchange of insults on the House floor in 1866, laced his speech with barbs directed at the popular senator from Maine.

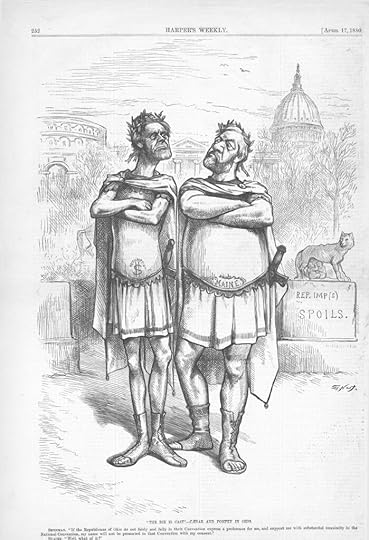

John Sherman of Ohio (left), one of the contenders for the 1880 Republican presidential nomination, and James G. Blaine of Maine regard each other warily in this Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly.

John Sherman of Ohio (left), one of the contenders for the 1880 Republican presidential nomination, and James G. Blaine of Maine regard each other warily in this Thomas Nast cartoon from Harper’s Weekly.Grant’s nomination would enable Republicans to go on the attack against Democrats. “We shall have to explain nothing away,” Conkling said in a veiled shot at Blaine that ignored the corruption that marred Grant’s two terms in office. More directly, Conkling contrasted what he claimed was the spontaneous outpouring of public support for Grant with the scheming of his opponents.

“Without patronage, without emissaries, without committees, without bureaux, without telegraph wires running from his house or the seats of influence to this convention, Grant’s name is on his country’s lips,” Conkling said. The reference to “telegraph wires” tweaked Blaine, who installed a telegraph at his home to follow developments on the convention floor. The claim that support for Grant came unprompted from voters also overlooked the fact — well-known in the convention hall — that Conkling was at the head of a trio of Republican bosses known as the “Triumvirate” backing the former president.

Conkling’s digs at Blaine weakened its impact of his speech, McClure believed. “Unlike the Ingersoll speech nominating Blaine in 1876, the speech of Conkling, able, eloquent, and grand as it was, left Grant weaker, instead of stronger.” The Grant and Blaine forces deadlocked through 35 ballots until Garfield emerged to claim the nomination on the 36th ballot.

As for the verse Conkling opened his speech with, no less an authority than Grant dismissed it as a pleasant but inaccurate legend. “Wars produce many stories of fiction, some of which are told until they are believed to be true,” he wrote in his memoirs. The tale that he accepted Lee’s surrender under an apple tree at Appomattox “would be very good if it was only true.”

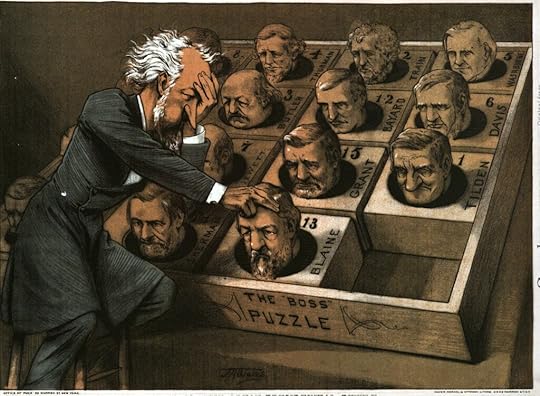

Puck’s rendering of the “presidential puzzle box” of 1880 shows Conkling trying to push down James G. Blaine.

Puck’s rendering of the “presidential puzzle box” of 1880 shows Conkling trying to push down James G. Blaine.__________________

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming this fall from Edinborough Press. Also published by Edinborugh and available at Amazon.com:

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

March 20, 2024

“Fifty Years a Journalist”

Chicago newspaper editor Melville Stone witnessed the rivalry between James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling — and much more.

On the wall of my study hangs a framed copy of The Chicago Daily News, the afternoon daily newspaper whose demise in 1978 I still mourn.

That beloved relic of my youth reminds me why I got into the news business and what I still love about it. It wouldn’t be there — and I might not have spent my adult life writing and editing for newspapers — had it not been for the man who founded the Daily News in 1875.

The banner headline on the last edition of the Chicago Daily News, published March 4, 1978.

The banner headline on the last edition of the Chicago Daily News, published March 4, 1978.Melville E. Stone was a true son of Illinois whose family hopscotched across the state in his childhood. Born in Hudson in 1848, he counted Nauvoo, Chicago, DeKalb and Libertyville among the towns and cities he called home as he grew up. His memoirs, Fifty Years a Journalist, offers a rich vein of insights and recollections about the people and events he covered through his years in the profession.

Stone’s father was a Methodist minister, blessed with an abiding patience, who “never stirred to anger, while stalwart in moral tone and unyielding in his endeavor.” In Nauvoo, Stone played on the ruins of the Mormon temple razed by an angry mob only three years before his family arrived. His family home there served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

I found Fifty Years as I worked on my upcoming book about James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling. Stone saw both of them up close and had some interesting things to say about the rivals whose battle for power started a year after Lincoln’s assassination and continued into the 1880s. But they were far from the only figures he encountered and wrote about.

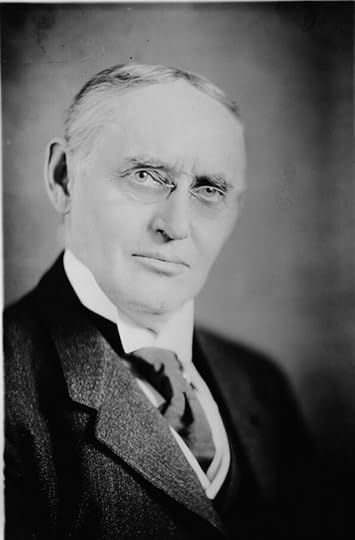

Melville Stone in 1904. Library of Congress.

Melville Stone in 1904. Library of Congress.As a nine-year-old in DeKalb, Stone developed a crush on the daughter of a local farmer named Joseph Glidden, who later made millions as the inventor of barbed wire. One Sunday in church he found himself sitting next to a “curious old gentleman” who appeared to doze off while Stone’s father preached. It turned out to be Horace Greeley, who was in Illinois as Republican Abraham Lincoln campaigned against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas for the U.S. Senate. Stone realized that Greeley wasn’t snoozing but listening carefully to Reverend Stone’s preaching when the visiting editor joined the family for lunch after church and engaged in an animated discussion with the cleric about his sermon.

Stone called Greeley a “strange, untrustworthy and greatly overrated man.” The editor of the New York Tribune was just one of many newspapermen of the era Stone regarded with scorn. Charles A. Dana, editor and publisher of the New York Sun, “was a malignant who frequently misused his power.” James Gordon Bennett, founder of the New York Herald, “while deserving much commendation for his enterprise as a news gatherer, was little better than a blackguard in the conduct of his paper. Wilbur F. Storey of the Chicago Times “revelled in indecencies.”

“Few of the famous journalists of my boyhood days were really ornaments of their vocation,” Stone wrote in Fifty Years. “They were largely responsible for the dislike, if not contempt, in which the editorial office was held.”

Stone was determined to change that. On Christmas Day, 1875, Stone and three others published the first edition of the Daily News, which promised that the newspaper would begin daily publication Jan. 1. The new daily would seek a “reputation for veracity and fair dealing in all our relations with the public,” Stone recalled. “Our quest was for public respect and permanency.”

Those were novel concepts in the 1870s. While most daily newspapers were no longer, strictly speaking, party organs, they routinely aligned with candidates and parties according to the politics of their editors and publishers. Stone vowed that his newspaper would be strictly independent and stick to news. But that didn’t mean then what it does today, as Harry Barnard recounts in his biography of John Peter Altgeld. In 1886, as Chicago reeled in the aftermath of the Haymarket Riot in which seven policemen and four demonstrators were killed after someone tossed a bomb at the officers. The Daily News — after initially urging calm — joined other voices demanding no quarter for the anarchists blamed for the violence, according to Barnard’s Eagle Forgotten.

The title page of Fifty Years a Journalist.

The title page of Fifty Years a Journalist.Stone himself reveals that he was a participant in — rather than a dispassionate chronicler of events — in the Haymarket story. In the immediate aftermath of the deadly riot, Stone contacted William Pinkerton and demanded that the proprietor of the private detective agency assign operatives to locate and follow anarchist leaders. The next day, when the coroner and prosecutor wondered how to characterize the death of Officer Mathias J. Degan, who was killed by the bomb. Since no one knew who threw the explosive, they were stymied as to how to proceed until Stone showed them the way.

“It seemed to me there was a well-settled principle of law which governed the case and I cited certain decisions which seemed to have a bearing,” Stone recalled. “I finally went to a standing desk in the room and wrote out what I considered to be a proper verdict for the coroner’s jury to consider.” Essentially, according to Stone, the verdict was the Degan died at the hand of someone “acting in conspiracy” with anarchist leaders.

These days, it’s hard to imagine a reporter or editor working with prosecutors to formulate charges, but in an era when newspapers were just beginning to embrace standards of impartiality and objectivity it wasn’t considered improper.

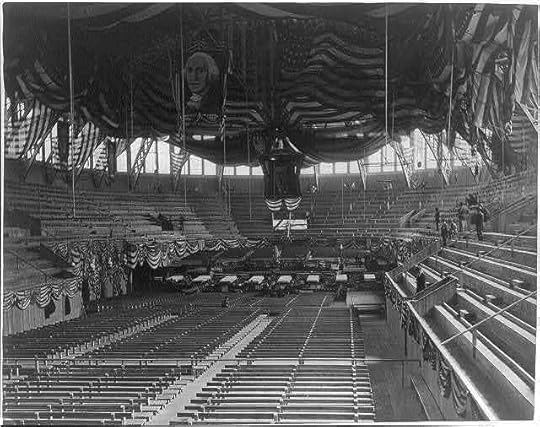

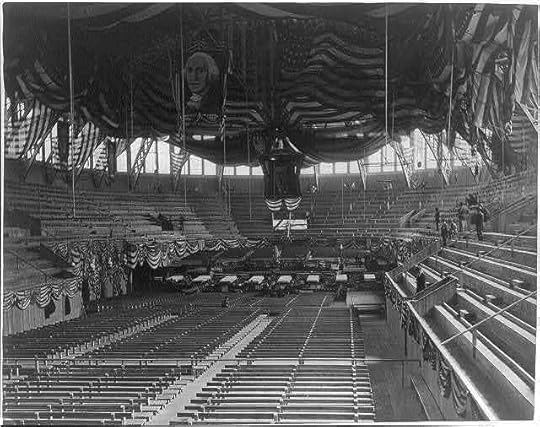

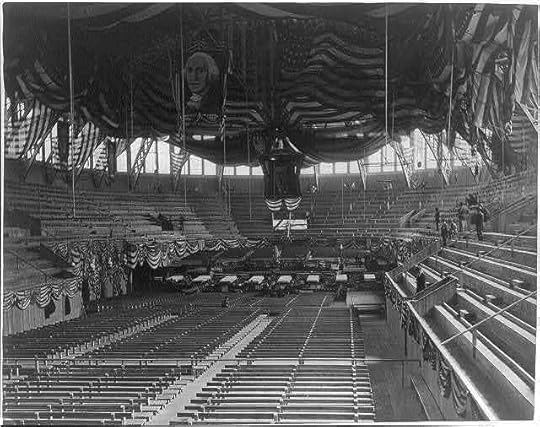

Stone’s career at The Daily News coincided with some of the most dramatic political events of the Gilded Age. In 1880, he was part of the press corps covering the Republican convention at the cavernous Interstate Industrial Exposition Building on Michigan Avenue between Van Buren and Monroe streets. Delegates yelled themselves hoarse as they demonstrated and cheered for Blaine and former president Ulysses S. Grant, the leading contenders for the party’s presidential nomination. Stone judged Conkling’s famous nomination speech for Grant to be “full of fire and very effective.” But James A. Garfield, who came to Chicago pledged to support John Sherman’s bid for the nomination while secretly harboring hopes to get it himself, superseded Conkling with a reasoned nomination speech for his candidate. “His audience was tired from shouting and ready for repose,” Stone wrote.

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Center in Chicago, site of the 1880 Republican convention. Library of Congress.

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Center in Chicago, site of the 1880 Republican convention. Library of Congress.Garfield won the nomination after 36 ballots in what remains the longest nomination battle in Republican (it took Democrats 103 ballots in 1924 to nominate a candidate). Stone seemed unimpressed by the Ohioan. He characterized Garfield’s involvement in the DeGolyer paving contract scandal as “inexcusable” and noted that his “cruel assassination evoked universal condemnation and closed every critical mouth for the time being.”

While Stone hinted at his disapproval of Garfield, he spared nothing in his evaluations of Conkling and Blaine. While the senator from New York was justly regarded as honest and incorruptible, he “had weaknesses which chilled the ardour of many and put serious limits on his strength as a leader,” according to Stone. “He delighted in stinging sarcasm and used it in an inexcusable fashion. He was arrogant and pompous to a degree that was ludicrous.”

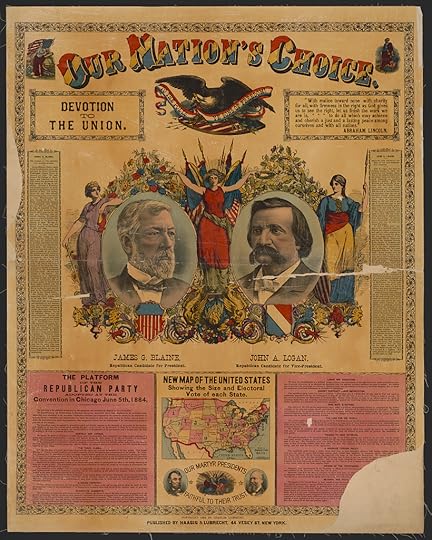

But Stone had something in common with Lord Roscoe: an abiding distrust of Blaine dating back to Stone’s days as a Washington correspondent. Blaine assiduously, and seemingly successfully, courted the Washington press corps and generally received favorable coverage. But Stone writes that there was widespread distrust of Blaine among the scribes in the nation’s capital. “I do not think any correspondent who served in Washington while Blaine was Speaker ever thought of voting for him” when Blaine won the Republican presidential nomination in 1884.

Stone aligned with the “Mugwumps” — a collection of reform-minded independent Republicans and their allies in the press — who balked at supporting Blaine’s candidacy. Politics makes for strange bedfellows: among those who refused to back Blaine was Roscoe Conkling, whose patronage power base at the Port of New York had made him the embodiment of everything Mugwump reformers opposed in politics. And so, after Blaine defeated President Chester Alan Arthur to win the Republican nomination, Stone found himself sitting across from Conkling in the former senator’s New York law office talking about the upcoming campaign.

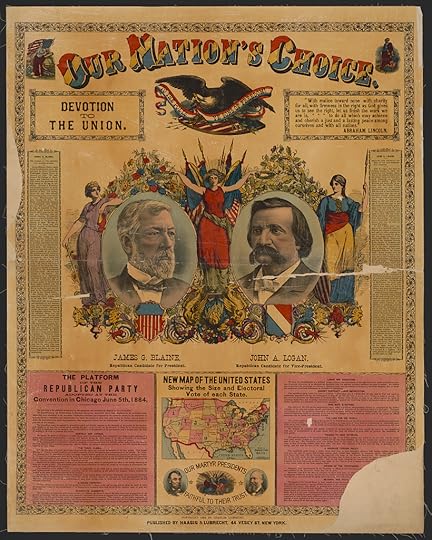

A Republican campaign poster from 1884 featuring Blaine and his vice-presidential candidate, John Logan of Illinois. Library of Congress.

A Republican campaign poster from 1884 featuring Blaine and his vice-presidential candidate, John Logan of Illinois. Library of Congress. “The interview was an amusing one,” Stone recalled. “Although we were alone, he struck his familiar senatorial attitude and proceeded to deliver of himself an oration.” He was not disappointed by Arthur’s defeat in Chicago. “But his hatred of Blaine survived, and was his absorbing interest. He closed his grandiloquent and distinctly didactic effort by turning to me and saying, ‘Well, there will be a funeral, and you and I will at least have the consolation that neither of us will ride in the front carriage.”

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age will be published later this year by Edinborough Press.

Also published by Edinborough Press:

Skirmisher: The LIfe, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The LIfe, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

February 24, 2024

Announcing The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age

After going back and forth on this for months, my publisher and I have settled on a title for the upcoming book on James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age traces the story of the feud that dominated American politics for almost 20 years after the Civil War.

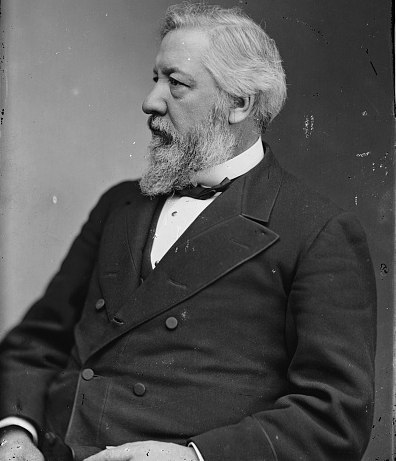

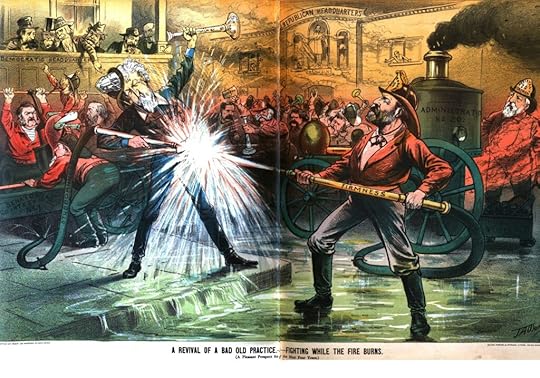

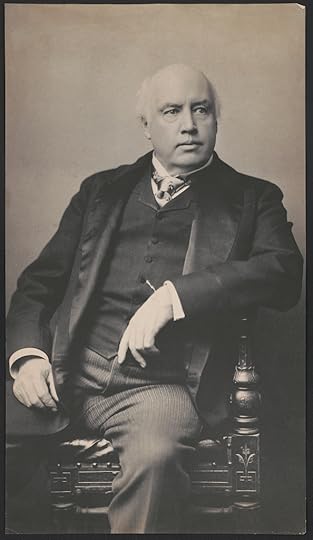

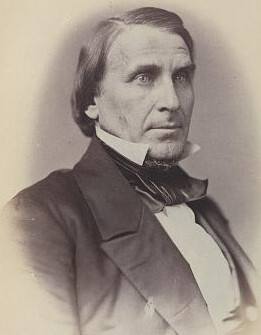

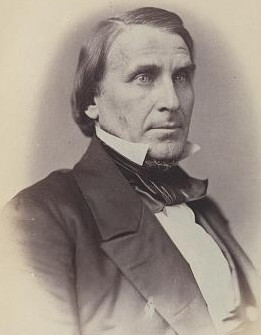

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress photo.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress photo.Blaine and Conkling were two of the most important — and most colorful — figures in the politics of the late 19th century. Each of them rose to positions of power in the Republican Party and Congress. They ran against each other for the Republican presidential nomination in 1876. They faced each other four years later when Conkling backed Ulysses S. Grant and Blaine mounted another campaign for the party’s nomination. Their conflict paralyzed the presidency of James A. Garfield and fueled the insanity that led to his assassination. When Blaine finally succeeded in getting the Republican nomination for president in 1884, Conkling — by now out of politics — sat on his hands and contributed to Blaine’s narrow defeat.

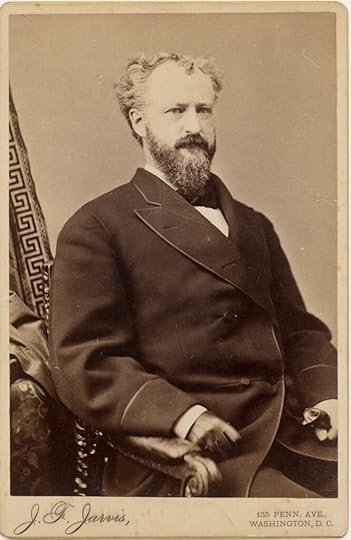

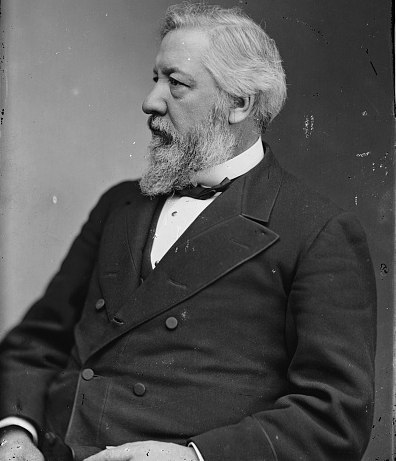

Roscoe Conkling. National Archives photo.

Roscoe Conkling. National Archives photo.Their compelling story begins in the shadow of Lincoln’s assassination and concludes as Theodore Roosevelt emerges on the national stage. It raises questions about political leadership, corruption, and reform that remain relevant today and sheds light on Reconstruction and the evolution of the Republican Party in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Along the way they encounter, work with, and fight against some of the most colorful and important figures of the era — Ulysses S. Grant, Frederick Douglass, Andrew Johnson, Horace Greeley, and Thaddeus Stevens, among others.

This will be my third book with Edinborough Press. Publication is expected later this year.

Puck cartoon showing President James Garfield hosing down foe Roscoe Conkling while James G. Blaine mans the firetruck.

Puck cartoon showing President James Garfield hosing down foe Roscoe Conkling while James G. Blaine mans the firetruck.

January 16, 2024

From Lincoln to Roosevelt

The story of the feud between James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling begins in the shadow of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and concludes with the emergence of Theodore Roosevelt.

A year after President Abraham Lincoln died from an assassin’s bullet, James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling launched the rivalry that consumed the Republican Party for the better part of the next two decades.

In April 1866, a snide remark by Conkling on the House floor provoked Blaine into mocking the New Yorker’s “grandiloquent swell” and “turkey gobbler strut.” Conkling never forgave the insult, and the pair became bitter foes. In the years that followed, as Blaine became Speaker of the House and Conkling presided over the Republican machine in New York State, their rivalry dominated American politics.

Maneuvering for advantage, power, and the presidency, the two Republican titans dragged many of the most famous figures of the era into their battle. Andrew Johnson, Horace Greeley, Benjamin Butler, Ulysses S. Grant, Charles Sumner, Rutherford B. Hayes, and James A. Garfield all played significant roles as participants — or foils — in the Blaine-Conkling feud.

A double-panel cartoon from Puck, May 11, 1881, at the height of the patronage battle between Roscoe Conkling (left) and President Garfield (center). Secretary of State James G. Blaine is stationed by the fire engine.

A double-panel cartoon from Puck, May 11, 1881, at the height of the patronage battle between Roscoe Conkling (left) and President Garfield (center). Secretary of State James G. Blaine is stationed by the fire engine.Another big name figured in Blaine’s 1884 presidential campaign. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was the Harvard-educated son of a New York blueblood. Only 29 years old, he was a member of the New York legislature, author of an acclaimed naval history of the War of 1812, and an outdoorsman and rancher. In 1884 he attended his first national convention when Republicans gathered at the Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago to nominate their candidate for president.

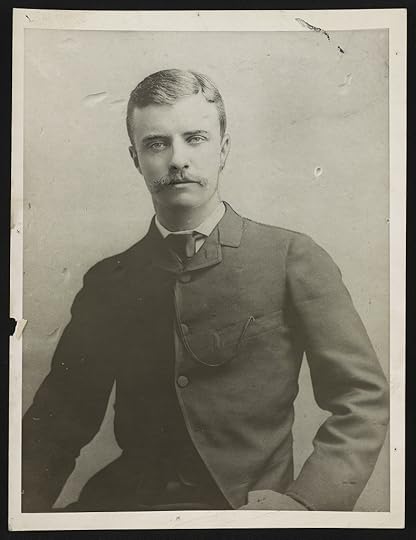

Theodore Roosvelt in 1884. Library of Congress.

Theodore Roosvelt in 1884. Library of Congress.The youthful Roosevelt stood out among the wizened old politicians on the convention floor. The New York Tribune commented on his “square head, matted with short, dry sandy hair.” The New York Sun noted Roosevelt’s thick “Scotch pebble” glasses and his habit of speaking with one hand on his hip. “Many delegates sought introductions to Mr. Roosevelt,” the Sun reported June 2. One said that “the brains intended for others in the Roosevelt family had evidently fallen into the cranium of young Theodore.”

Most of the delegates came to Chicago favoring Blaine, the “Plumed Knight” whose bids for the Republican nomination in 1876 and 1880 came up short. While wildly popular, Blaine was also distrusted and disliked by a significant number of Republicans, including reform-minded figures like Roosevelt.

Numbering among the delegates backing Senator George Edmunds of Vermont, Roosevelt helped engineer an early defeat for Blaine when he urged delegates to make John Lynch, a Black Republican from Mississippi, temporary chairman of the convention instead of the white candidate backed by Blaine.

“It is now, Mr. Chairman, less than a quarter century since, in this city, the great Republican Party organized for victory and nominated Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, who broke the fetters of the slave and rent them asunder forever,” Roosevelt declared. “It is a fitting thing for us to choose to preside over this Convention one of that race whose right to sit within these walls is due to the blood and treasure so lavishly spent by the founders of the Republican Party.”

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago, site of the 1884 Republican Convention. Library of Congress.

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago, site of the 1884 Republican Convention. Library of Congress.Roosevelt’s eloquence carried the day for Lynch but did nothing to dent support for Blaine, who won the nomination on the fourth ballot. Roosevelt left Chicago for the Dakota territory after the convention ended, refusing to commit to Blaine. When a Minnesota newspaper reported that he had no objections to the nominee, Roosevelt denied saying any such thing.

But he couldn’t stay on the sidelines. Roosevelt returned to New York City from the Dakota Territory in early October. On October 12, the Sun published an interview with Roosevelt in which he reluctantly disclosed he would back Blaine. Roosevelt wanted to talk about his hunting prowess instead of politics. “I shot three grizzlies, three terrors,” he bragged to the reporter. Eventually, he described why he changed his mind.

“It is altogether contrary to my character to occupy a neutral position in so important and exciting a struggle, and besides my natural desire to occupy a positive position of some kind, I made up my mind it was clearly my duty to support the ticket,” he said. “It was a great surprise to Mr. Blaine’s managers when I announced my intention to support the Republican ticket,” he added. “More so to them, perhaps, than any one else.”

Roosevelt went on to issue a ringing endorsement of Blaine at a Republican rally in Brooklyn.

His decision to back Blaine stunned his reform-minded friends. But Roosevelt believed as a loyal Republican he had no choice. “Mr. Blaine was clearly the choice of the rank and file of the party,” Roosevelt wrote in his autobiography, “and I supported him to the best of my ability in the ensuing campaign.” Partisanship prevailed over political purism.

A campaign poster for James G. Blaine and John Logan. Library of Congress.

A campaign poster for James G. Blaine and John Logan. Library of Congress.It was precisely the sort of thinking that Conkling might have applauded had Republicans nominated anyone else for president. While Roosevelt put aside his qualms about Blaine to campaign for him, Conkling refused to do the same and sat out the 1884 election.

It wasn’t the first time that a Roosevelt found himself at odds with Conkling. The family’s connection with the story of the Republican rivals actually began seven years earlier, when Teddy’s father, Theodore Roosevelt Sr., crossed paths with the New York Republican boss.

“Lord Roscoe,” as many called Conkling, embodied all the tendencies in politics that President Hayes and upper-class reformers found so objectionable. The loathing was mutual. At the Republican state convention in Rochester, Conkling delighted delegates when he passionately denounced reformers as “the man-milliners, the dilettanti and carpet-knights of politics.” Undeterred, Hayes nominated the elder Roosevelt to run the Port of New York, the patronage bastion that formed the basis of Conkling’s political power in the Empire State.

The genteel Roosevelt abhorred politics but soon became embroiled in one of the most bitter nomination battles in congressional history. Conkling fought the nomination with everything at his disposal and carried the day in the Senate when it was voted down 31-25. On February 9, 1978, less than two months after his defeat in the Senate, Roosevelt died of stomach cancer.

“My father,” Teddy would write years later, “was the best man I ever knew.” In 1884, young Roosevelt demonstrated a pragmatic approach to politics that might have dismayed his father but would serve him well in the years ahead.

___________________________

I am finishing work on a book about the rivalry between Blaine and Conkling to be published by Edinborough Press. My two previous books are Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age and Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Both are available at amazon.com.

Congress and the King of Frauds

Congress and the King of Frauds

Skirmisher

Skirmisher

December 26, 2023

“Col. Ingersoll Dies Smiling”

The famous Republican orator who nominated James G. Blaine for president in 1876 wanted a “slow death” because he had things he wanted to say at the end of his life. He didn’t get the chance.

Death came to Robert Green Ingersoll before he could get in the last word.

Not surprisingly for a man who made his name making speeches, he hoped he would be conscious as the end of his life approached because “I have some things I want to say.” Instead, according to the Chicago Tribune, he was stricken suddenly by heart failure on July 21, 1899, and death “came in the twinkling of an eye — instant transition apparently from good health to death.”

Even so, he appeared content with his fate as he passed. “The smile that started to mantle his features never was finished,” the Tribune wrote in its front-page story on Ingersoll’s death. “He died before his wife could seize his hand.”

The headline over the Tribune story declared “Col. Ingersoll Dies Smiling.”

Puck lampoons Robert Ingersoll on the cover of its May 3, 1882 issue. Library of Congress.

Puck lampoons Robert Ingersoll on the cover of its May 3, 1882 issue. Library of Congress.In some ways, it is surprising that Ingersoll had anything left to say at the time of his death. Over the course of a career in public life that lasted more than 30 years, Ingersoll earned a reputation as one of the country’s most eloquent and prolific orators.

He delighted in denouncing the perfidy of the Democratic Party and tweaking the piety of 19th-century Christians. He made a career out of the former and earned notoriety for the latter. But he was capable of waxing eloquent on topics ranging from Moses and Shakespeare to the family and his vision of the future.

It was a golden age of oratory. In The Age of Acrimony, Jon Grinspan writes that “fame came from speechifying. Stump speakers and campaign hollerers were the ubiquitous talking heads of their day. American citizens were connoisseurs of their every gesture and flourish.” The Chautauqua lecture circuit that flourished into the early years of the 20th century began in the 1870s in Upstate New York with sermonizing and hymn singing but eventually spread across the country and featured politicians like William Jennings Bryan.

Ingersoll was ideally suited for an era in which oratory mixed politics and entertainment. Born in 1833 in Dresden, N.Y, he was the son of an itinerant Congregationalist minister who served churches in New York, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The elder Ingersoll “occupied the pulpits of many churches, but invariably aroused opposition by expressing opinions at variance with the accepted theology of the time,” according to the New York Times.

“Bob” Ingersoll inherited his father’s public speaking abilities and love for disputation without accepting his religious beliefs. Ingersoll became a lawyer and opened a law practice in Peoria, Ill., with his brother in 1858. Like many Americans in the mid-19th century, Ingersoll started out in life as a Democrat.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, he raised a cavalry unit and served as a colonel in the Union army. Ingersoll’s service in the conflict, which included capture by Confederates under the command of the infamous Nathan Bedford Forrest, turned him into an ardent supporter of the party of Abraham Lincoln.

Robert Ingersoll. Library of Congress.

Robert Ingersoll. Library of Congress.Ingersoll put his speechmaking talents to work for the Republican Party as early as 1866. He served as attorney general in Illinois under Gov. Richard Oglesby in the late 1860s. But Ingersoll did not come to national prominence until 1876, when Republicans gathered in Cincinnati to nominate a candidate for president.

Ingersoll arrived in the Queen City as a delegate supporting James G. Blaine, the former House Speaker and odds-on favorite to win the Republican presidential nomination. Blaine’s enemies included Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York and independent-minded reformers who believed Blaine had corruptly used his position in public life to enrich himself. But Blaine also had many supporters. Ingersoll numbered among the most ardent. “I have a very decided preference for Blaine as my first choice,” he told the New York Herald.

That became evident when he stood before the convention to place Blaine’s name in nomination.

Republicans, he told the convention, demanded a presidential candidate who was sound (read “conservative”) on financial questions, well-versed in governance, and believed that the federal government should “protect every citizen at home and abroad.” Republicans wanted an honest man as their candidate, but — in a shot at congressional Democrats who had been investigating Blaine’s dealings with financiers backing an Arkansas railroad project — “they do not demand that their candidate have a certificate of moral character signed by a Confederate Congress.”

Ingersoll was just warming up.

“Our country,” he said, “asks for a man worthy of her past and prophetic of her future; asks for a man who has the audacity of genius; asks for a man who has the grandest combination of heart, conscience, and brain the world ever saw. That man is James G. Blaine.”

Then came his peroration:

“Like an armed warrior, like a plumed knight, James G. Blaine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lance full and fair against the brazen forehead of every traitor to his country and every maligner of his fair reputation. For the Republican party to desert that gallant man now is as though an army should desert their general upon the field of battle. James G. Blaine is now and has been for years the bearer of the sacred standard of the Republican Party. I call it sacred, because no human can stand beneath its folds without becoming and without remaining free.”

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.Frenzied cheering and demonstrations erupted when Ingersoll concluded. “Plumed Knight” became a Blaine nickname. Along with Roscoe Conkling’s nomination of Ulysses S. Grant at the 1880 Republican convention and Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech to Democrats in 1896, Ingersoll’s oration ranks among the greatest pieces of 19th-century convention speechmaking.

“In some ways, it was a great speech,” Blaine biographer Charles Edward Russell wrote, “in some ways the greatest speech ever heard on a convention floor. For the next generation schoolboys recited it.”

Ingersoll’s reputation as a public speaker was made, but the speech proved more successful for him than for Blaine. Opposition to the “Plumed Knight” remained widespread. On the seventh ballot, Republicans turned to Rutherford B. Hayes, the favorite son candidate of Ohio Republicans. Ingersoll dutifully went to work to elect Hayes and proved a master of the “bloody shirt” rhetoric by which Republicans invoked the memory of the Civil War to stoke hostility to Democrats.

“Like an armed warrior, like a plumed knight, James G. Blaine marched down the halls of the American Congress and threw his shining lance full and fair against the brazen forehead of every traitor to his country and every maligner of his fair reputation.” Robert G. Ingersoll, 1876

“Soldiers, every scar you have on your heroic bodies was given to you by a Democrat,” he declared to a gathering of Union Army veterans in Indianapolis. “Every scar, every arm that is lacking, every limb that was gone, is a souvenir of a Democrat. I want you to recollect it. Every man that was the enemy of human liberty in this country was a Democrat. Every man that wanted the fruit of all the heroism of all the ages to turn to ashes upon the lips — every one was a Democrat.”

Not content to attack Democrats, Ingersoll turned his guns on organized religion. He accused Christians of narrow-minded bigotry but facetiously styled himself as a friend of the clergy who wanted to open their minds. “One of the first things I wish to do, is free the orthodox clergy,” he wrote in 1879. “They are not allowed to read and think for themselves. They are taught like parrots, and the best are those who repeat, with the fewest mistakes, the sentences they have been taught. They sit like owls on some dead limb of the tree of knowledge, and hoot the same old hoots that have been hooted for eighteen hundred years.”

Two years later, Ingersoll sparred with Jeremiah S. Black in the pages of the North American Review regarding religion and declared that “Thousands of most excellent people avoid churches, and, with a few exceptions, only those attend prayer meetings who wish to be alone. The pulpit is losing because the people are growing.”

It was one thing to demonize Democrats, quite another to challenge the authority of the clergy. Ingersoll’s eagerness to propound his controversial views made him, in the words of the New York Times, “the most noted of English-speaking infidels.” In Notes on Ingersoll, a response published in 1883 to the North American Review piece, the Rev. L.A. Lambert of Waterloo, New York dismissed the agnostic from Illinois as an ignorant blowhard.

“It has been well said by some keen observer, that whatever else a man writes, he always writes himself. This is conspicuously true of Mr. Ingersoll. His writings are a mere, evolution of himself on paper. The glitter, the sophistry, the bad faith, verbal legerdemain, the pervading egotism, the assumed infallibility, and the brazen audacity of statement so conspicuous in his writings, are the full bloom and blossom of his character.”

Politicians kept their distance for a while. But Ingersoll’s assault on organized religion did little to diminish his popularity as a public speaker, and the political class eventually made its peace with his iconoclastic views. In 1888, following the death of Blaine’s arch-foe Roscoe Conkling, Ingersoll delivered the eulogy at a memorial service in Albany.

Through it all, Ingersoll’s ability to touch audiences kept him in the forefront of American orators. “The human heart was his instrument,” the Times wrote at the time of his death, “and he played upon it with a master’s power.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I am working on a book about the rivalry between James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling. I am the author of Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age and Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Both are available at amazon.com.

Congress and the King of Frauds

Congress and the King of Frauds

Skirmisher

Skirmisher

October 17, 2023

Neighbors and allies, estranged by politics

The historic partnership of Ulysses S. Grant and Elihu B. Washburne failed to survive the pressures of presidential politics.

The home of Ulysses S. Grant in Galena, Ill. Robert Mitchell photo.

The home of Ulysses S. Grant in Galena, Ill. Robert Mitchell photo.GALENA, Ill. – Two very different men from this northwest Illinois town forged a friendship that helped save the Union in its hour of greatest need but foundered years later on the shoals of politics.

Ulysses S. Grant was a down-on-his-luck Army washout working in his father’s leather goods store when Fort Sumter fell in April 1861. Like tens of thousands of patriotic Americans, he answered President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers and returned to serve his country.

Elihu B. Washburne was Galena’s congressman – a native of Maine who came west to make his fortune, practiced law, and joined the Republican Party in its infancy. He was a longtime acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln who was among the handful of dignitaries who greeted the Railsplitter when he arrived in Washington for his inauguration in 1861.

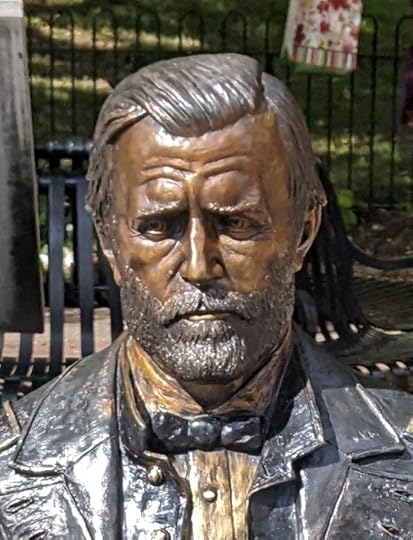

From a statue of Ulysses S. Grant on Main Street in Galena. Photo by Robert Mitchell.

From a statue of Ulysses S. Grant on Main Street in Galena. Photo by Robert Mitchell.The Washburne-Grant partnership changed the course of the Civil War and, for years, proved mutually beneficial.

After Grant enlisted, the Galena lawmaker acted as his patron. Washburne helped Grant secure a promotion to brigadier general and acted as his champion and advocate in Washington.

Washburne was uniquely positioned to assist his Galena neighbor.

When Grant, an Ohio native, told Washburne that he intended to seek a commission from Ohio Governor William Dennison, Washburne persuaded him to approach Illinois Governor Richard Yates instead and promised to intercede on his behalf, according to historian John Y. Simon.

When Illinois members of Congress nominated candidates for brigadier general, Grant’s name stood at the top of the list — and he knew who to thank. “I think I see your hand in it, and admit I had no personal claims for your kind office in the matter,” he wrote to Washburne. “I can assure you, however, my whole heart is in the cause we are fighting for, and I pledge myself that, if equal to the task before me, you shall never have cause to regret the part you have taken.”

The Elihu B. Washburne home in Galena, Ill. Robert B. Mitchell photo.

The Elihu B. Washburne home in Galena, Ill. Robert B. Mitchell photo.Grant took command in Cairo, Ill., and began his push south in February 1862. He overwhelmed Confederates at Fort Donelson and repelled a furious Confederate attack at Shiloh to win an important Union victory. When Grant came in for criticism that he had been caught by surprise by the rebels in southwestern Tennessee, Washburne offered a vigorous defense in a speech on the House floor delivered on May 2, 1862.

“I come before the House to do a great act of justice to a soldier in the field, and to vindicate him from the obloquy and misrepresentations so persistently and cruelly thrust before the country,” Washburne began. Grant was being unfairly maligned by armchair critics, Washburne asserted. “As to the question whether there was, or not, what might be called a surprise, I will not argue it; but even if there had been, General Grant is in no wise responsible for it, for he was not surprised.”

Elihu B. Washburne. Library of Congress.

Elihu B. Washburne. Library of Congress.Washburne let himself get carried away in his eagerness to defend his neighbor when he declared “There is no more temperate man in the Army than General Grant. He never indulges in the use of intoxicating liquors at all.” In fact, Grant struggled with alcoholism, but the evidence is clear that he was sober during the fighting, according to Grant biographer Ron Chernow.

Washburne’s speech cemented the bond between the Galena residents, according to James G. Blaine. The speech “was of great value to General Grant, both with the Administration and the country,” the Republican bigwig wrote in the first volume of his Twenty Years of Congress. It “laid the foundation of that intimate friendship which so long subsisted between him and Mr. Washburne.”

Grant’s study and writing room in his Galena home. Robert Mitchell photo.

Grant’s study and writing room in his Galena home. Robert Mitchell photo.Washburne later helped shepherd the legislation through Congress to create the rank of lieutenant general that made Grant the highest-ranking officer in the Union army. The bond between Grant and Washburne ranks as one of the most important partnerships of the war. And it continued after the surrender at Appomattox.

Grant repaid Washburne for his friendship and support after he was elected president. Grant picked Washburne as his secretary of state — an appointment that was either a symbolic gesture of gratitude or a genuine plan to install a faithful ally in the most prestigious Cabinet post. In any event, Washburne resigned a week after his nomination was confirmed and was sent to Paris by Grant to serve as U.S. minister to the French government.

The living room at the Elihu B. Washburned home in Galena, Ill. Robert B. Mitchell photo.

The living room at the Elihu B. Washburned home in Galena, Ill. Robert B. Mitchell photo.Washburne’s tenure coincided with the end of the Franco-Prussian war and the rise of the Paris Commune. With the commune came a reign of terror. Impoverished Germans living in the French capital were particularly vulnerable to retribution by enraged Parisians. Washburne sheltered as many as 600 at the U.S. legation, according to historian David McCullough, and he arranged for 56 Americans trapped in the city to leave. In 1876, before his tour of duty was over (he stepped down in the fall of 1877) some were mentioning him as a possible candidate for president.

By 1880, when he was back in the United States, Washburne found himself the object of even more presidential speculation. He wanted nothing to do with it. His friend Grant was seeking an unprecedented third term in the White House and Washburne insisted that he was a “Grant man,” according to Augustus L. Chetlain, a Galena resident who was on friendly terms with Grant and Washburne.

Illinois Republicans were unconvinced, Chetlain remembered. They “began to distrust Mr. Washburne’s sincerity as a supporter of Gen. Grant and began to talk about it openly” ahead of the Republican convention to be held in Chicago. “I went to Mr. Washburne and told him what I had heard, and added that he ought to stop certain of his friends I named from publicly supporting him, and that the feeling against him was growing bitter,” Chetlain recalled. “He replied he had done everything possible to prevent people from supporting him, and had said a thousand times that he was not a candidate, but a supporter of General Grant.”

Washhburne grew increasingly worried about this unbidden groundswell and insisted on standing by Grant, Chetlain wrote, but his name kept coming up. One month before Republicans gathered in Chicago for their convention, the New York Tribune reported that Washburne would get thirteen votes for the nomination — hardly a groundswell but enough to attract attention if Grant stalled.

Backing Grant was a trio of powerful senators known as the “Triumverate.” Roscoe Conkling of New York, John Logan of Illinois and J. Donald Cameron of Pennsylvania were “Stalwarts” with powerful political machines and a shared loathing of President Rutherford B. Hayes. At the Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago, they controlled more than 300 delegates pledged to Grant.

Grant’s foes were less organized but just as plentiful as his supporters. They included “Half-Breed” Republicans who rallied to Blaine. Liberal- and independent-minded Republicans who abhorred the corruption that marred Grant’s presidency (and disliked Blaine for similar reasons) balked at Grant’s bid for a third term in the White House.

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago, site of the 1880 Republican National Convention. Library of Congress photo.

The Interstate Industrial Exposition Building in Chicago, site of the 1880 Republican National Convention. Library of Congress photo.The Grant and anti-Grant forces were evenly matched. One the first ballot, Grant received 304 votes, Blaine 284, and Senator John Sherman of Ohio ninety-three. Washburne did far better than the Tribune predicted, receiving thirty votes. As the balloting dragged on and on, support for Washburne remained consistent. As late as the thirty-fourth ballot, Washburne received thirty votes.

Grant followed the proceedings via telegraph from Galena. When the deadlock finally broke and the convention rallied to dark-horse candidate James A. Garfield on the thirty-sixth ballot, Grant took the news in stride. “Well, I am glad that as good a man as Garfield has received the nomination,” Chetlain recounts.

Grant’s followers were much less charitable when it came to Washburne. “The feeling among many of the Grant delegates, who had stood solidly and so long for their candidate, seemed to intensify against Washburne” after the convention adjourned, according to Chetlain, “and Gen. Grant shared in the feeling. Washburne’s conduct was condemned in bitter terms, and he was charged with having acted perfidiously. In the excitement, much was said and done which was clearly unjust to Mr. Washburne.”

Five years later, Grant, now living in New York, was dying of cancer. Washburne made a hurried visit to the city in the hopes of reconciliation with his old friend but returned to Galena downcast. “He said he went to one of the leading hotels in the city and all the daily papers noticed his arrival,” Chetlain wrote. “When I asked him if he made an effort to see Gen. Grant, he answered. ” ‘No. The General knew I was in the city, and if he desired to see me he could have easily notified me. He was the greater man, and it was for him to extend his hand, which I would have taken with pleasure.’ I never,” Chetlain added, “heard him allude to the matter again.”

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I am working on a book about the rivalry between James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling. I have written an account of the Credit Mobilier scandal and a biography of Iowa Populist James B. Weaver. Both are available at amazon.com.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.https://www.amazon.com/Skirmisher-Times-Political-Career-Weaver/dp/1889020265/ref=sr_1_1?crid=5SKZ03TMN2PL&keywords=skirmisher+weaver+mitchell&qid=1697543941&sprefix=skirmisher+weaver+mitchell%2Caps%2C68&sr=8-1

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.https://www.amazon.com/Skirmisher-Times-Political-Career-Weaver/dp/1889020265/ref=sr_1_1?crid=5SKZ03TMN2PL&keywords=skirmisher+weaver+mitchell&qid=1697543941&sprefix=skirmisher+weaver+mitchell%2Caps%2C68&sr=8-1

September 23, 2023

“Gath” and Gilded Age Washington

Few Gilded Age journalists wielded their pen with greater effect than the correspondent known as “Gath.”

Born in Delaware in 1841, George Alfred Townsend came to prominence as a correspondent for the New York Herald and New York World during the war and the hunt for Abraham Lincoln’s assassin that followed. In the introduction to a volume based on his memoirs of covering the Civil War, Lida Mayo writes that Townsend “loved the life of a correspondent”– a passion that comes through in his writing, whether the subject was the war or the scandal-filled years that followed.

George Alfred Townsend, a k a “Gath.” Library of Congress photo.

He was a journalist and novelist. His western Maryland estate is now a state park that features a monument to the “Bohemian Brigade” of Civil War correspondents.

Townsend had a writer’s eye for detail and a penchant for pointed observation. Describing Richmond, which he entered shortly after its fall to Union forces in 1865, he noted the absence of churches or factories along the James – “only here and there a pleasant mansion, flanked by Negro cabins” – to make a broader point about the stagnation of the slave economy.

A bronze equestrian statue of George Washington, located near the fallen rebel capitol, offered an opportunity to comment on the folly of secession. “Gazing beyond at the capitol itself, and back again at the figure which overlooks the building, it is not hard to imagine that, while the noisy debates of a congress of traitors to the Union that he founded were in progress, those bronze lips sometimes smiled in scorn.”

In the years after the war, Townsend wrote for the Chicago Tribune, where he assumed a pen name made up of his initials – G-A-T with an “h” at the end for good measure. The resulting non de plume reflected Townsend’s religious upbringing (he was the son of a minister) and his capacity for whimsy. Gath was a Philistine city whose inhabitants were afflicted with illness when the captured Ark of the Covenant was brought into town (1 Samuel 5: 9) — and it was the home of Goliath (1 Samuel 17:4).

Like the rest of the country, Townsend grappled with the legacy of the war. His contempt for the rebels was never in doubt – he rolled his eyes at the worship of Stonewall Jackson by Lost Cause romantics – but he had little sympathy for Reconstruction. A tour of the South in 1872 for the Chicago Tribune detailed corruption in Arkansas and South Carolina while discounting or ignoring the plight of former slaves. His reporting from below the Mason-Dixon Line helped crystallize emerging Northern impatience with post-war efforts to rebuild the South.

Townsend traveled widely for the Tribune – not only down south but to Boston as well. He wrote about Louis Napoleon and the actor Edwin Forrest. His columns from Washington described the dueling grounds at Bladensburg, Md., as well as political events. His expansive reporting led, in 1874, to the publication of Washington Outside and Inside, perhaps the best of the “guide-to-your-nation’s-capital” books that appeared in the years after Appomattox.

But it was as a chronicler of the sleazy politics of the Gilded Age that Gath excelled. Few if any correspondents of the day could write more vividly about the personalities that dominated the Capitol.

That became evident in one of Gath’s first pieces in the Tribune, in which he compared two prominent congressional Republicans — smooth, oily Ohio Sen. John Sherman and Rep. Elihu Washburne of Illinois.

Sherman “displays a deferential modulation, a soft gesture of the head and flowing motions of the palms,” Townsend wrote. Sherman was skilled at the art of persuasion but perhaps less attuned to the ethics of the issues about which he speaks. “[N]o man in the United States knows right from wrong so well as John Sherman,” Townsend told his readers, “or makes the distinction so infrequently.”

Washburne, on the other hand, exhibited a refreshing economy of language as he spoke on an appropriations bill. Where Townsend found Sherman unctuous and oily, Washburne presented a “large, broad, ‘square-footed’ bearing’” that projected a combative honesty.

Rep. Elihu Washburne. Library of Congress.

“I thought,” Townsend wrote, “that if all this Congress could imbibe his spirit, to say ‘no’ to office beggars and lobbyists, to permit no easy nature to yield up each member’s personal custody of the Treasury but hold in fierce and unrelenting vigilance every dollar and every officer, how worthily this year might be made to appear among the recent years of physical courage – a year of moral courage, of sacrifice, and of honesty.”

Although vivid, Townsend’s description of Washburne reveals what was his greatest weakness as a writer. Even allowing for the stylistic differences of nineteenth-century writing, his literary toolkit did not come equipped with brevity or declarative sentences.

Nevertheless, Townsend – and a handful of others, notably Henry Van Ness Boynton of the Cincinnati Gazette – represented something new and important as journalism began to become a profession rather than an extension of partisan politics.

That became evident in the early weeks of the Credit Mobilier sensation in 1872. Shortly after the New York Sun published its expose of the stock sales to members of Congress, the Tribune sent Townsend to Philadelphia to get to the bottom of the scandal.

Why Philadelphia? That’s where disgruntled Credit Mobilier investor Henry S. McComb had filed suit against Republican Rep. Oakes Ames of Massachusetts to obtain more shares of the profitable Union Pacific construction subsidiary with the strange name. In the course of deposition testimony, McComb produced letters from Ames in which the lawmaker explained that he had no more shares to provide because he was placing it with members of Congress to promote the interests of the Union Pacific.

In chasing down the story, Townsend accomplished something remarkable. His piece for the Tribune, published Sept. 17, 1872, focused on the story behind the story and represents an early example of the press reporting on itself. He retraced the steps of New York Sun correspondent Albert M. Gibson, who broke the story, and concluded that the scoop was the result of careful scheming by McComb’s attorney, Jeremiah Black.

Recalling the sensation of hitting pay dirt as he investigated what would become the biggest story of his career, Gibson in later years wrote that “To say that I was startled at my ‘find’ would inadequately explain my mental state.” Townsend, writing for the Tribune, concluded the discovery was somewhat less miraculous — it “had first met the eye of Jerry Black.”

Townsend’s investigation of the story would lead him to McComb, toward whom he seemed to take a liking. The Delaware-born railroad speculator displayed a “semi-Southern tone and spirit of genial address, magnanimous personal impulses, the touch of honor, and the carriage of a man of the world, yet heedful of his reputation.”

But Townsend was nothing if not intellectually honest. In the years to come, he would revise his generous assessment of McComb, who died in 1881 after reckless speculation in Mississippi railroads. The man he once saw an aspiring cavalier had revealed himself to be “jealous of money and belligerent when deprived of his share of it.”

The work of Townsend, Boynton, Gibson and other Gilded Age scribblers is chronicled in Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age, available at amazon.com