Changing Names

I’ve dropped “King of Frauds” as the name of this blog and replaced it with “A Strife of Interests.”

This blog began about nine years ago as my book on the Credit Mobilier scandal, Congress and the King of Frauds, was published. Over time the blog took on a logic of its own and was no longer narrowly focused on Oakes Ames, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the scandal that rocked Washington in the winter of 1872-1873.

With another book set to appear later this year — this one on the rivalry between James G. Blaine of Maine and Roscoe Conkling of New York — it is time to rechristen the blog. The url, kingoffrauds.wordpress.com, will remain the same.

For the title I have borrowed from The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce’s delightful lexicon of words and phrases compiled in book form in 1906. It comes from his definition of politics: “A strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.”

In full, the definition reflects Bierce’s deep-seated cynicism, but the phrase “strife of interests” speaks to what makes the Gilded Age so interesting to me. Americans were working out what their world would be like in the years after the Civil War. Strife abounded — in the South, the West, and the industrial urban North. The politics of the period — its personalities, its scandals, its language — reflected the tumultuous, wrenching evolution of modern America between 1865 and 1900.

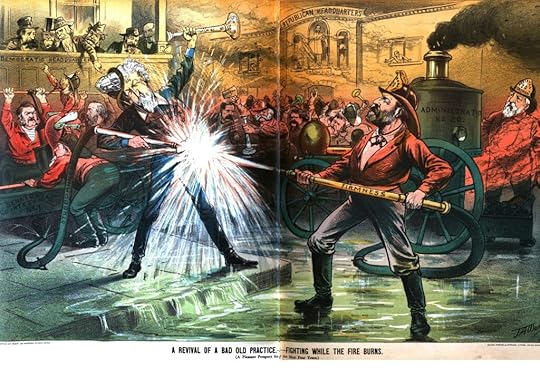

The illustration replacing the New York Sun headline over its scoop about Credit Mobilier comes from Puck. It shows President James A. Garfield directing a fire hose at Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican machine. Managing the water pump in the background is Blaine, Conkling’s nemesis.