Robert B. Mitchell's Blog, page 4

September 12, 2023

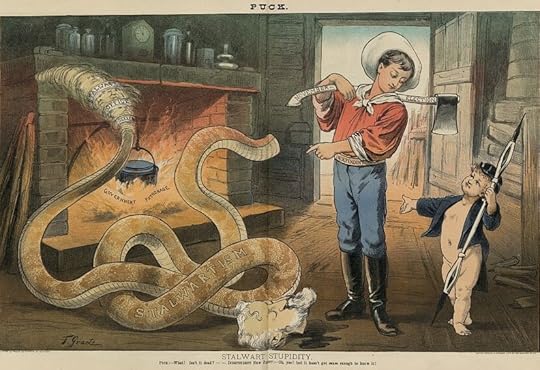

The strange history of ‘Stalwart’

Coined by James G. Blaine, applied to supporters of Roscoe Conkling, and invoked by an assassin.

The tortured political etymology of “Stalwart” originated shortly after Rutherford B. Hayes took office as the nation’s 19th president.

It was April 1877. Washington D.C. was awash in rumors that Hayes had agreed to withdraw federal support for embattled Republican governors in South Carolina and Louisiana as part of a deal with Democrats that allowed him to take office after his bitterly disputed election victory over Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York.

Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, the Republican “Plumed Knight” with a devoted following among the party faithful, warned that such a deal was in the works the day after Hayes was sworn in. “I know there has been a great deal said here and there, in the corridors of the Capitol and around and about, in by-places and high places as of late, that some arrangement has been made,” he warned on the Senate floor. “But I deny it on the simple, broad ground that [it] is an impossibility that the administration of President Hayes could do it.”

A month later, when it looked like that was exactly what Hayes was doing, Blaine shared his worries with a letter to the Boston Herald republished April 12 in the New York Times.

Blaine wrote that he fully supported D.H. Chamberlain, the ousted Republican governor of South Carolina. “I am equally sure” that Louisiana’s embattled Stephen Packard “feels that my heart and judgment are both with him in the contest he is still waging against great odds for the Governorship he holds by a title as valid as that which justly and lawfully seated Rutherford B. Hayes in the Presidential chair.”

Blaine continued: “I trust also that both Governors know that the Boston press no more represents the stalwart Republican feeling of New England on the pending issues than the same press did when it demanded enforcement of the Fugitive Slave law in 1851.”

A political label was born.

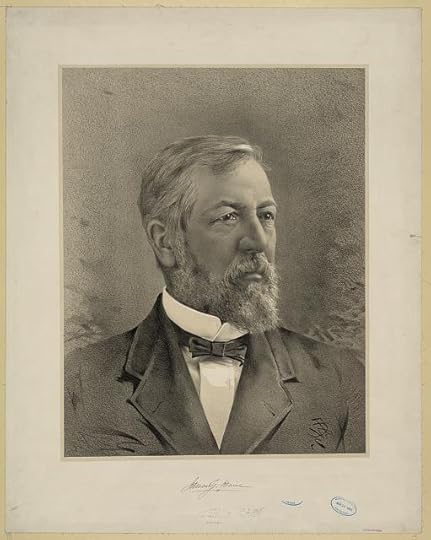

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.The letter represented an attempt by Blaine, an astute student of public opinion, to align with rank-and-file Republicans who looked on with alarm at Hayes’s retreat from the vigorous defense of Republican-led Reconstruction state governments.

Hayes was finding all kinds of ways to alienate Republicans, including Blaine’s arch-rival, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. Conkling presided over a political machine powered in large part by the patronage bastion at the Port of New York. The port employed around 1,000 workers who owed their jobs and a portion of their paychecks to their political sponsor. President Ulysses S. Grant named allies of Conkling to run the port, giving the senator and his allies control over its vast patronage treasure house.

Hayes styled himself as a reformer who wanted to take patronage out of government hiring practices — and he made Conkling and the Port of New York his top target. The president counted some prominent Republican as allies, including George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly who had made civil service reform a personal crusade, and Carl Schurz, the one-time Liberal Republican who now served in Hayes’s Cabinet.

But none were as formidable as Conkling. Imperious, arrogant, and eloquent, the boss of the New York Republican machine would not cower before Hayes and his friends. At the 1877 New York Republican convention, “Lord Roscoe,” as he would become known, angrily proclaimed his contempt for self-styled reformers and their allies in the press, the Cabinet, and White House.

“Who are these men who in newspapers and elsewhere are cracking the whip over Republicans now and playing schoolmaster to the Republican Party and its conscience and convictions?” Conkling thundered as Curtis nervously looked on. “Their vocation and ministry is to lament the sins of other people. Their stock in trade is rancid, flat self-righteousness. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Their real object is office and plunder. When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’”

A Stalwart timeline:

April 1877: Blaine uses the phrase “stalwart Republicans” in a letter describing rank-and-file Republican opponents of President Hayes.September 1877: Conkling delivers an angry, eloquent denunciation of civil service reformers at the New York Republican convention in Rochester that makes him the unofficial leader of the stalwart Republicans described by Blaine.1880: “Stalwart” becomes a noun to describe the rank-and-file Republicans loyal to Conkling and other party bosses.July 2, 1881: Assassin Charles Guiteau proclaims “I am a Stalwart” after shooting President James A. Garfield at a Washington train station. Garfield dies of his wound Sept. 19, 1881,Nov. 14, 1881: Blaine testifies at Guiteau’s trial that he “invented” the use of the phrase “stalwart” Republican.Conkling’s furious denunciation of civil service reformers touched a chord with rank-and-file Republicans (not to mention party bosses in other states) and made him — rather than Blaine — the leader of what became known as the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. By 1880, Blaine carried the banner for a rival faction of Republicans who were less committed to Reconstruction and not as opposed to civil service reform as the Stalwarts. They were known as the Half-Breeds.

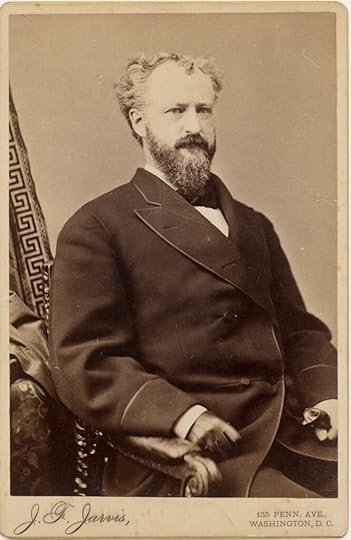

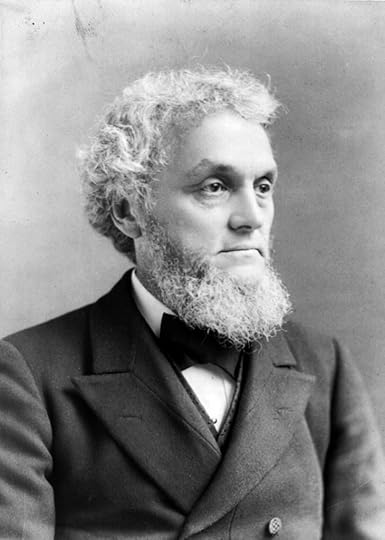

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.The feud between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds tied the 1880 Republican convention in knots. Stalwarts led by Conkling favored the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant for an unprecedented third term as president. Blaine led the Half-Breeds in opposition to Grant and Conkling. It took 36 ballots at the convention in Chicago before Republicans settled on a dark-horse alternative to Blaine or Grant — James A. Garfield of Ohio. To placate New York Stalwarts, Garfield selected Chester A. Arthur, a Conkling ally and former chief of the Port of New York, as his vice-presidential running mate.

Garfield defeated Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock in the fall, but the Stalwart-Half Breed feud persisted. Blaine, Garfield’s secretary of state, cautioned Garfield against giving too much away to Conkling’s Stalwart allies. Conkling wanted his man to run the Port of New York. After weeks of back-and-forth negotiations, Garfield astounded Washington and infuriated Stalwarts by nominating Conkling foe William Robertson to run the port. Conkling and protege Thomas Platt of New York promptly resigned from the Senate, returned to New York, and began campaigning for the state legislature to send them back to Washington.

The feud between Half-Breeds and Stalwarts filled the front pages and editorial columns of newspapers. A delusional office-seeker named Charles Guiteau closely followed the drama. As he pursued a longshot campaign for a diplomatic posting, Guiteau became obsessed with the feud and fearful of Blaine’s influence over Garfield. He decided to kill Garfield after concluding that he was the reason he wasn’t getting the diplomatic job he wanted. On July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield at a Washington train station and then proclaimed, “Arthur is president, and I am a Stalwart.”

Garfield succumbed to his wounds less than three months later. Conkling and Platt failed in their bid to return to Washington. Arthur, now president, surprised Conkling by refusing to remove Robertson at the Port of New York. Guiteau went on trial for the assassination of Garfield on Nov. 14, 1881.

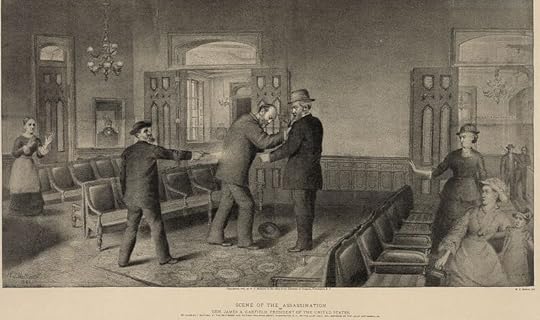

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.Blaine was the first witness. Under cross-examination by Guiteau’s attorneys, he reprised the political feud between Stalwarts and Half-Breeds. Blaine was clearly in no mood to dwell on the political feud, and when the topic of the word “Stalwart” came up, he grew irritable. “If counsel is wishing a chapter of political history to form part of the testimony, it ought to be a correct one,” Blaine snapped. “Stalwart” had been in use as a political label long before the Chicago convention, he told the court, “and I invented it myself.”

************

I am finishing a book about the 20-year feud between Blaine and Conkling. The working title is “Rival Republicans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling and the Politics of the Gilded Age.” Other books now available at amazon.com:

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

April 4, 2023

The kingmaker of 1880?

Philadelphia financier Wharton Barker made some pretty bold claims about his role at the 1880 Republican convention. Is there any truth to them?

Wharton Barker knew how to get your attention.

In the May 1916 issue of Pearson’s Magazine, one of the many muckraking journals popular in the early 20th century, the Philadelphia financier claimed he played kingmaker at the Chicago convention that nominated James A. Garfield and eight years later in the same city when Republicans nominated Benjamin Harrison.

“In the case of each of these gentlemen, I was the man behind the scenes. I did not do everything, but I planned everything — even to the applause with which Garfield was greeted every time he entered the convention hall.”

Claims of this sort invite skepticism from historians and journalists. Allan Peskin, author of the pre-eminent biography of Garfield, dismisses Barker as a plutocratic dilettante who hungered for attention. Benjamin T. Arrington, author of The Last Lincoln Republican: The Presidential Election of 1880, acknowledges Barker’s activities on Garfield’s behalf but stops well short of endorsing Barker’s claims to the role of kingmaker. Candice Millard and Kenneth D. Ackerman, who have also written useful accounts of Garfield’s campaign for the White House and subsequent tragic death after being shot in July 1881, make no mention of Barker.

Undated photo of Wharton Barker. Wikimedia.

Undated photo of Wharton Barker. Wikimedia.Nevertheless, there is reason to believe many of Barker’s claims. He encouraged Garfield when few others considered him presidential material. He orchestrated demonstrations of support for the dark-horse candidate. He seems to have played a role at a dramatic moment when Garfield challenged Conkling and won the admiration of the delegates. While Barker did not singlehandedly pull the strings to get Garfield the nomination, he certainly intervened at key moments to help make it possible.

The 1880 convention was one of the most dramatic of the 19th century and remains notable as the longest nomination battle in the history of the Republican Party. It took delegates 36 ballots to select a nominee — and for the second straight time they didn’t rally around one of the favorites.

The convention began as a battle between two Republican giants — former president Ulysses S. Grant and James G. Blaine, the senator from Maine and former Speaker of the House. Four years earlier, Grant was finishing his second term in the White House. Blaine had been the prohibitive favorite to win the Republican nomination for president but faced opposition from long-time rival Roscoe Conkling and party liberals who distrusted him. On the seventh ballot the party turned to Rutherford B. Hayes, who went on to win a disputed general election victory over Samuel Tilden of New York with a minority of the popular vote and a one-vote margin in the Electoral College.

Grant went with his wife, Julia, on a world tour after leaving the White House but remained in the headlines as journalist John R. Young accompanied the Grants. His bid for a precedent-busting third term was supported by a “Triumverate” of Republican bosses — the foremost of whom was Conkling — and opposed by many who thought it dangerous to blow up the two-term tradition that dated back to Washington. Blaine became the leader of “Half Breed” Republicans who opposed Grant’s return to the White House and the party machines supporting him. “Stalwart” Republicans led by Conkling rallied to Grant.

I was the man behind the scenes. I did not do everything, but I planned everything — even to the applause with which Garfield was greeted every time he entered the convention hall.

— Wharton Barker

Barker’s claims can be boiled down thusly:

— He approached Garfield in early 1880 to outline his plan to make the Ohioan the Republican nominee. Barker describes a meeting with Garfield in early January at which they discussed a presidential campaign and Barker’s plans for a commercial union with Canada. Garfield’s diary confirms the two met in February — not January — to discuss the two topics. The diary entry reflects the ambiguity with which Garfield regarded a run for the White House. He was already committed to supporting the nomination of Treasury Secretary John Sherman and, according to the diary, “I told him [Barker] I would not be a candidate.” But Garfield added this postscript: “I should have added in this connection, that Mr. Sherman said that in case he could not be nominated, he preferred me to any other man and that he would be entirely willing to have his strength transferred to me.” Garfield remained outwardly loyal to Sherman but, in the pages of his diary, confessed that he was thinking about a White House bid.

— Barker claims to have contacted influential Republicans in Wisconsin and Indiana to advance his plans for getting Garfield the nomination. Peskin notes that Wisconsin Republicans were planning a dark-horse bid by Garfield in 1879, before Barker got involved.

— Barker packed the galleries with observers who would cheer Garfield on his signal. Barker said he stationed men in the galleries who watched Barker (he sat on the platform behind the convention chairman) and would start cheering Garfield on Barker’s signal. Newspaper reports on the convention confirm that Garfield routinely received rousing cheers from spectators as he entered the convention hall. When he challenged Conkling after the New Yorker demanded the expulsion of West Virginia delegates who refused to pledge support for a Republican nominee before the convention selected a candidate, Garfield was warmly hailed by spectators. “With the galleries,” Barker wrote, “to all appearances, Garfield was immensely popular.”

— Barker planned to put Garfield’s name before the convention not by a nomination, but by having a delegate vote for him. This is a plausible claim. On the second ballot, a Pennsylvania delegate — Barker identifies him as W.A.M. Grier of Hazelton — cast a vote for Garfield. On every one of the subsquent ballots (28 would be cast before the day was out) Garfield’s name rang out in the convention hall as one of the candidates receiving votes. Before the day was over, a second Pennsylvania delegate added to Garfield’s tally.

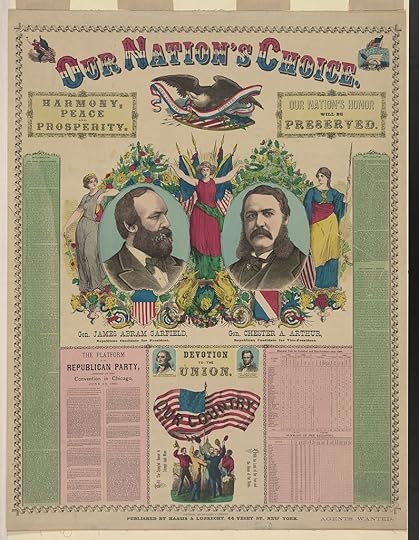

Republican campaign poster from 1880 showing James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Library of Congress.

Republican campaign poster from 1880 showing James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Library of Congress.The rest of the story is well known. On the 34th ballot, 16 Wisconsin delegates voted for Garfield. On the next ballot, most of the Indiana delegation lined up behind him. The stampede was on and on the 36th ballot weary delegates put Garfield over the top. To placate Conkling and disconsolate New York Republicans, Garfield put Conkling lieutenant Chester A. Arthur on the ticket as his vice-presidential candidate. Garfield defeated Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock to win in November, but his presidency was tragically cut short by assassination. Garfield was shot July 2, 1881, by Charles Guiteau, and died on September 19. He was 49.

As for Barker, he remained in the Republican fold through the 1880s but defected to the Democrats in 1896 to support William Jennings Bryan. Four years later he ran as the presidential candidate of “middle-of-the-road” Populists unreconciled to Bryan. He was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt who split with him when Roosevelt ran for president in 1904 but backed Teddy eight years later when he ran as a Progressive, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

February 8, 2023

The skirmisher’s legacy

“The Pen is Mightier: The Muckraking Life of Charles Edward Russell,” by Robert Miraldi

Editor’s Note: It’s been a minute, as the kids say. I’m hard at work on “Rival Republicans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of the Gilded Age,” so I haven’t had the time or bandwidth to post to the King of Frauds blog with regularity. That may change in the coming months as the manuscript moves toward completion. In any event, I stumbled across a surprising and interesting book that connects with James B. Weaver and wanted to share my impressions.

*****

Charles Edward Russell was an Iowan, a newspaperman, a prominent muckraker, and one of the founders of the NAACP. He was a Socialist, and an outspoken supporter of the war against Germany in 1917. He was also an acolyte of James B. Weaver.

Robert Miraldi recounts Russell’s fascinating life story in “The Pen is Mightier,” a 2003 biography that covers everything from the Johnstown Flood and Lizzie Borden to World War I. His life story chronicles the eventful closing decades of the 19th century and the tumultuous early years of the 20th century. But, for me anyway, it is his connection to Weaver that is the most interesting.

Russell grew up in Davenport, the son of a crusading newspaper editor and the grandson of a Baptist preacher. From his father he learned the news business and the importance of the newspaper as a guardian of the public interest. From his grandfather he learned the importance of standing against injustice and fighting against the abuses of the powerful.

Russell encountered Weaver in the 1880s, as Weaver’s career in politics seemed to have leveled off. After breaking with the Republicans in 1877, Weaver ran for Congress in 1878 as a member of the Greenback-Labor Party. He won, with Democratic support, and then won the party’s presidential nomination in 1880. He broke taboos against campaigning in person and toured the country to win votes but failed to break through. In 1881, the New York Times mocked him as “the almost forgotten Greenbacker.” His career seemed stalled.

Nevertheless, Russell took an instant liking to the political insurgent from Davis County. “Weaver seemed to cast a spell over Russell,” Miraldi writes. ” ‘He never walked down the street or entered a public assembly anywhere without instantly drawing all eyes,’ Russell recalled admiringly years after he covered Weaver while he served in Congress. Russell liked the fact that Wall Street loathed Weaver, that respected publications called him vile names, and that Weaver denounced the governing class. He was Russell’s kind of guy: a dissenter.”

Weaver returned to Congress in 1884 and won re-election two years later. In 1892, he ran for president a second time, this time at the head of the Populist Party ticket and carried four states.

When he wasn’t running for office or serving in Congress, Weaver was also a newspaperman. With fellow Greenbacker Edwin Gillette Weaver co-edited the Iowa Tribune, a weekly published in Des Moines that advanced Greenback (and, later, Populist) principles. When he and Russell covered an Iowa political convention (Miraldi doesn’t specify the party), Weaver instructed the young reporter on the ways of politics.

“Look at the convention floor,” Weaver told Russell, according to Miraldi. “The most active participants on the floor were the lobbyists from the railroad interests and the lawyers from the business interests.” They had learned, Weaver told Russell, “that it was cheaper to manipulate a convention than buy an election.”

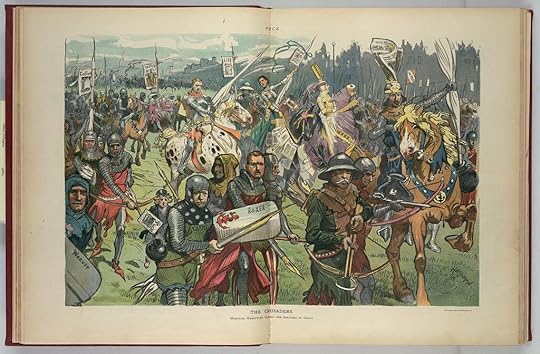

“The Crusaders” portrays the muckrakers of the early twentieth century. Russell is to the right of Ray Stannard Baker. Library of Congress photo.’

“The Crusaders” portrays the muckrakers of the early twentieth century. Russell is to the right of Ray Stannard Baker. Library of Congress photo.’Journalism for Weaver never represented anything more than an avocation. It offered a platform to advance his views, but the political arena remained his primary focus throughout his life. As late as 1911, less than a year before he died, Weaver floated the idea of running for Congress.

For Russell, the story came first. As a reporter for the New York Herald he was one of the first to make it into Johnstown, Pa.. after a poorly maintained dam at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club — a resort for the wealthy whose members included Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick — gave way. More than 2,200 died as 20 million tons of water flooded streets and destroyed homes. The experience of covering the flood and its aftermath, Miraldi writes, taught Russell “the power of the press as a catalyst in mobilizing the public.”

More big news followed. He was sent to Fall River, Mass., as local authorities investigated the gruesome murders of undertaker Andrew J. Borden and his wife. His investigative work into malfeasance by local authorities in Brooklyn helped topple (only temporarily, as it turned out) the boss of the local Democratic machine. He covered political conventions and was installed as editor of the Chicago American by William Randolph Hearst.

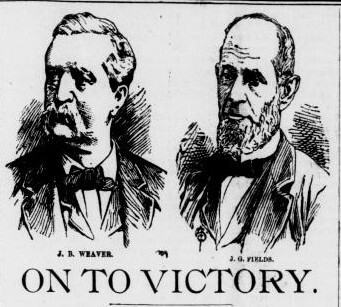

The Populist ticket in 1892: James B. Weaver (left) and vice-presidential candidate J.G. Fields (right). Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

The Populist ticket in 1892: James B. Weaver (left) and vice-presidential candidate J.G. Fields (right). Library of Congress/Chronicling America.As he became preoccupied by the crushing poverty endured by the urban poor and the seeming untouchable power of big business, Russell left daily journalism to become a muckraker. He took on the beef trust in Chicago and, memorably, New York’s wealthy Trinity Church, perhaps the biggest slumlord in the city. Following race riots in Springfield, Ill., in 1908, Russell joined with other New York liberals and W.E.B. DuBois to form the NAACP.

Russell soon grew disillusioned with muckraking. It sold magazines and produced incremental change but seemed to accomplish little in the way of systemic reform. Like Weaver, who declared that “avarice is an untrustworthy public servant, and that greed cannot be regulated or made to work in harmony with the public welfare,” Russell believed that fundamental change was needed.

Weaver rejected Socialism, but Russell embraced it. He joined the party and ran for mayor of New York City and governor of New York on the Socialist ticket, only to break with the party over World War I. Russell believed that German militarism represented an existential threat to the future of western democracy and that pacifism in the face of this challenge was irresponsible. After the war he became a prolific author.

The parallels between Weaver and Russell are striking. Weaver started life as a Democrat, joined the Republican Party only to split with it over monetary questions, and ran two campaigns for president on insurgent party tickets and then, at the end of his life, returned to the Democratic Party.

Russell’s career followed a similar zig-zag course, going from daily journalism to muckraking into politics before returning at the end of his life to writing. Weaver, I think, would have approved and understood.

******

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available on amazon.com

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver. Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

October 22, 2022

Harnessing “the priceless boon” of community

One of my favorite scenes in The Searchers involves a moment that seems almost unimaginable today.

The arrival of Texas Ranger Charlie McCorry at the Jorgensen homestead in west Texas is treated in the classic 1956 John Ford film as a great occasion – because he brought a letter.

Lars Jorgensen hovers over his daughter as she reads. He plucks the missive from the fire after she angrily wads it up and hurls it into the flames. A letter – the second of the year, Jorgensen marvels – was too precious to simply discard.

Part of Ford’s genius was his gift for illuminating aspects of daily life in the 19th-century American west. Perhaps no feature of existence from that century is harder to imagine in our digitized world than the extreme loneliness endured by families eking out a new existence on farms and ranches throughout the country.

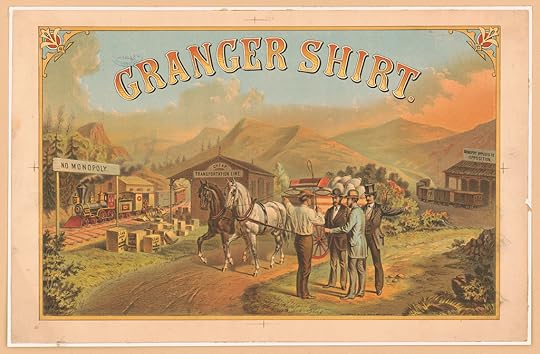

Grange recruiting poster. Library of Congress.

When the family of James B. Weaver left its homestead in southern Iowa in the 1840s and settled in what would become the county seat town of Bloomfield, the gregarious Iowan rejoiced. It was a “priceless boon” to have the chance to visit neighbors and talk to them, Weaver recalled. “Our home life was more varied as we met our neighbors with greater frequency.”

Isolation was psychologically devastating. Defeating it would yield significant rewards.

Among the first to understand this were Methodist preachers who convened summer camp meeting at which families would stay for days to worship, sing and celebrate with their neighbors. The first camp meeting was probably held in Logan County, Ky., in 1800, according to a blog post for the United Methodist Church by Joe Iovino. In the decades that followed, camp meetings were held across the Old Northwest and in the territories – such as Iowa – across the Mississippi.

“In them,” according to an entry in the Encyclopedia of World Methodism, “multitudes were converted.”

In Davis County, Iowa, Cumberland Presbyterians (the denomination that would claim William Jennings Bryan as one of its own) held camp meetings, but the Methodists pioneered the event, according to Henry C. Ethell’s history of the county’s early days. “Cloth tents or board houses were ranged round a large square, seated with slabs or thick planks. Families living several miles away came and lived in these tents throughout the meeting. A Sunday congregation would often number three of four thousand,” Ethell wrote.

The grandson of an Iowa Methodist, the Rev. Francis Carey, offered an account of how camp meetings worked in the Pioneer History of Davis County. The meeting included the famous Iowa Methodist pastor Henry Clay Dean, who preached two sermons – the first failing to move his listeners. But the second did not disappoint. “The people were completely overcome,” Carey’s grandson wrote, “and many in the multitude, weeping and sobbing, embraced the church that evening.”

Weaver fondly remembered the visits of circuit-riding Methodist pastors who stopped at isolated farms to minister to families who could not attend church.

Through these forms of evangelism, the Methodists gained a foothold on the frontier that would help make the denomination one of the most influential in the United States in the 19th century.

In the years after the Civil War, a secular group formed to overcome the isolation of the farmstead rose to power and prominence. The Patrons of Husbandry, widely known as “the Grange,” spread like wildfire across the Old Northwest and the Upper South.

Its purpose was, in theory, apolitical. The founders of the Grange envisioned a secret society much like the Masons in which elaborate ritual played a central role. “Although the original idea of the founders appears to have been that the benefits of the order to its members would be primarily social and intellectual, it very soon became apparent that the desire for financial advantages would prove a far greater incentive for the farmers to join,” Solon Justus Buck wrote in his history of the Grange.

Buck writes that Granger efforts were initially directed at cooperative schemes aimed at lowering production costs for members – buying supplies and insurance – and maximizing profits on commodity sales. Another concern soon converted the Grange from an apolitical society for farmers into a potent force in American politics.

Growing discontent with railroad business practices and political clout alarmed farmers who saw the promises of access to distant markets for their products evaporate due to high – and often seemingly arbitrary – freight rates. Attempts in state legislatures to address this issue by regulating rates began as early as the late 1850s but went nowhere. The Grange offered a means for farmers to organize themselves politically to press their case for railroad regulation.

Washington took notice as Grange lodges proliferated across the Old Northwest. “The movement of the western people against the great railroad monopolies begins to assume definite shape,” the Washington Evening Star noted in its editorial column on Feb. 20, 1873. The newspaper predicted that “it is pretty certain that the control of railroad fares and freight will be the issue on which the next legislatures of several of the western states will be chosen.”

Anti-railroad sentiment did indeed emerge as a prominent issue in the off-year elections of 1873. State Republican platforms throughout the Old Northwest called for “cheap transportation” and denounced railroad business practices. Anti-Monopoly candidates swept to victory in Iowa and elsewhere. Granger William R. Taylor defeated Republican Gov. C.C. Washburn in his bid for re-election despite Washburn’s record as a critic of railroad business practices.

In the late 1880s, another farmer’s movement followed the trail blazed by the Grangers. The National Farmers Alliance & Industrial Union advocated an explicitly political program that called for, among other things, government control of the railroads, Robert C. McMath Jr. writes in his history of populism. Like the Grangers, the Alliance featured its own passwords and rituals, McMath notes – including burial services.

The movement spread across the Plains and the South with rallies that McMath likened to camp meetings. In 1892, it morphed into a political party – the People’s Party, commonly referred to today as the Populists – with Weaver at its head. Weaver carried four states in that year, running against Grover Cleveland and President Benjamin Harrison.

James B. Weaver and his running mate, J.G. Fields. Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

The conversion from social organization to political party, however, did not end well. In 1896, Populists put Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan at the top of their ticket – a move backed by pragmatists like Weaver but which spelled the end of the party as an effective third force in American politics. Weaver, who had broken with the Republicans in 1877 and spent the next two decades in the ranks of the Greenback-Labor and Populist parties – eventually joined the Democrats.

Nevertheless, the populist movement enjoyed its moment in the sun in large part because it brought farmers together to work for a common goal. It merged politics and social engagement and tapped into what historian Joseph F. Wall identified as the farmer’s delight in meeting with others. “He is an individualist who enjoys working in the fields alone, but he also craves company,” Wall wrote of the prototypical farmer in his bicentennial history of Iowa. “Most farm organizations from the National Grange to the Farm Bureau were initially inspired by the farmer’s desire for some kind of social communication and an opportunity for an interchange of new ideas.”

Lars Jorgensen would have appreciated that.

———————-

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

C ongress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver

February 6, 2022

The question of motive

It ranks as perhaps the most perplexing question of the Credit Mobilier scandal: Why did Rep. Oakes Ames embark on an influence-peddling campaign in the winter of 1867-1868?

Rep. Oakes Ames wanted something when he sold the valuable shares of Credit Mobilier stock to members of Congress toward the end of the Johnson administration. Everyone agreed on that. But what was it, exactly?

During the winter of 1867-1868, as the battle between Congress and President Andrew Johnson built toward the crescendo of impeachment, Ames approached members of the House and Senate with a deal that seemed almost too good to be true. He offered his colleagues a chance to buy valuable stock in a company with the unlikely name of Credit Mobilier at par — that is, at the price at which the shares were issued. If they couldn’t come up with the cash, Ames would provide the shares anyway and his price when they sold their shares. All told, Ames found nine buyers in the House and two in the Senate.

“I did not see,” Republican Representative William D. Kelley would later tell investigators, “how I could lose anything.”

Ames was an investor in the government-chartered Union Pacific Railroad and Credit Mobilier, the railroad’s affiliated construction arm. When Congress chartered the railroad in 1862 to hasten the completion of a transcontinental railway, it imposed conditions that made it very difficult for investors to make money. The Pacific Railroad Act prohibited investors from selling the railroad’s stock below its initial sale price, required the stock to be purchased in cash, and made investors liable for the railroads debts.

On top of that, the railroad was being built to serve towns, cities, and farms that did not exist.

Rep. Oakes Ames. Library of Congress

Rep. Oakes Ames. Library of CongressNo wonder the railroad struggled to raise capital. Union Pacific Vice President Thomas Hart Durant’s solution was Credit Mobilier (named after a prestigious French banking house), which contracted with the Union Pacific to build sections of line west from Omaha. Railroad stockholders could reap handsome profits by investing in the company that built the railroad. Credit Mobilier overcharged for its work and took payment in Union Pacific stocks and bonds. Because it was not an original investor, it was free to sell railroad securities at the market price.

As part of a peace deal settling a bitter corporate feud between factions led by Ames and Durant, the Union Pacific entered into an ambitious and generous new contract with Credit Mobilier in which the construction company would receive up to $96,000 per mile as it built the road. The railroad paid Credit Mobilier $48 million under the terms of the contract. When the so-called “Oakes Ames contract” went into effect, the value of Credit Mobilier shares escalated dramatically — one congressional committee later estimated that the stock price more than doubled from its original $100.

The chairman of the committee investigating the stock sales to lawmakers believed Ames sold the shares to prevent Congress from inquiring too closely when details of the Oakes Ames contract emerged. “He understood it would be a good thing when that time came that he should have, if possible, some strong backers,” Republican Representative Luke Potter Poland told the House. “He intended by his course of conduct to provide himself with them.”

George Frisbie Hoar, a Massachusetts Republican who served on another House committee probing Credit Mobilier, agreed. “The managers of Credit Mobilier knew they had violated the law, and that an investigation would ruin their whole concern.”

This theory varies slightly from the conclusion of the Poland committee. In its report to the House, the panel asserted that Ames sold Credit Mobilier shares to martial opposition to measures backed by Elihu Washburne and his brother, Cadwallader, aimed at regulating Union Pacific freight rates.

In casting about for an explanation, Poland, Hoar, and others overlooked the testimony of the one figure in the scandal who reliably told the truth, even when it reflected poorly on him.

Rep. Luke Potter Poland. Library of Congress.

Rep. Luke Potter Poland. Library of Congress.Oakes Ames never failed to be candid about his role in Credit Mobilier, and from the outset he was clear about his intentions. “We want more friends in this Congress,” he confided to Henry S. McComb, a fellow Union Pacific investor who was pestering Ames for Credit Mobilier stock and whose lawsuit against Ames formed the basis for the New York Sun story that broke the scandal wide open. When testifying to the Poland committee, Ames said of the shares he sold: “I strove to use them in a way that I thought most advantageous in spreading our influence everywhere.”

Ames insisted, however, that the stock sales were not bribes. “If you want to bribe a man you want to bribe the one who is opposed to you, and not bribe the one who is your friend,” he told Poland’s committee.

One could question Ames’s judgment, but no one could doubt his candor.

So it is surprising that historians have paid so little attention to Ames’s own explanation for the stock sales.

After a bipartisan committee investigating the scandal recommended the expulsion of Ames and Democratic Representative James Brooks of New York, the Massachusetts lawmaker offered a convincing insight into his motivations.

Ames reminded the House of the amendments to the Pacific Railroad Act passed in 1866. The changes served the interests of the Central Pacific, the Union Pacific’s partner and rival in the transcontinental project, by authorizing the California-based railroad to build east indefinitely until it reached the Union Pacific’s line.

At the same time, the legislation authorized another railroad, a feeder line with the unwieldly name of Union Pacific-Eastern Division (rechristened later as the Kansas Pacific), to extend as far west as Denver — much farther than originally contemplated. Congress thus authorized “two rival corporations” to “race across the continent” and claim territory once expected to be served by the Union Pacific, Ames told his colleagues. The effect on the interests of the Union Pacific, he asserted, was catastrophic. “[C]omplete recovery,” he said, “was impossible.”

Ames began to sell Credit Mobilier at very favorable prices to his colleagues the following year.

The timing of Ames’s sales strongly suggests that he was not acting to thwart any particular piece of legislation. He was more interested in creating a cadre of influential allies who would be willing and eager to step in to defend the interests of his railroad when they were threatened by hostile legislation. The lesson of 1866 was that the Union Pacific needed all the help it could get on Capitol Hill — and that Credit Mobilier stock would give lawmakers reason to assist the railroad. “I have found,” Ames told the Poland committee, “that there is no difficulty in inducing men to look after their own property.”

Library of Congress.

Library of Congress.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age. Available at amazon.com

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age. Available at amazon.com

August 20, 2021

The rhetoric of Roscoe Conkling

As many of you know, I am fascinated by the language of Gilded Age politics. Few if any politicians of the era used it more effectively or powerfully than Roscoe Conkling, the imperious senator from New York and “boss” of the state’s mighty Republican organization.

Conkling’s standard posture at the lectern or on the Senate floor was attack. Over the years he poured out his scorn on James G. Blaine, Andrew Johnson, Charles Sumner, and Rutherford B. Hayes, among others. He took particular delight in flailing civil service reformers and the Liberal Republicans who bolted from the party in 1872 to back Horace Greeley’s doomed bid for the White House.

In a speech at the Cooper Union on July 23, 1872, he dismissed the critics of President Ulysses S. Grant thusly: “Every thief and cormorant and drone who has been put out – every baffled mouser for place or plunder – every man with a grievance or a grudge – all who have something to make by a change, seem to wag an unbridled tongue or to drive a fouled pen.”

Everything about that line – its language (“cormorant,” “drone,” and my favorite, “baffled mouser”), and its alliteration (“grievance or a grudge” and, Joe Duffus reminds me, “place or plunder”) — combine to pack a powerful punch. Conkling ranked as the master of rhetorical belligerency in an age known for its rough and tumble politics. This is a good example of why.

November 30, 2020

March 4, 1869: Grant’s first inaugural

Ulysses S. Grant’s first inaugural address, like the man himself, was modest and straightforward.

The hero of the Civil War, whose battlefield victories along the Mississippi and in Virginia saved the Union, took the oath of office on March 4, 1869. His predecessor, Andrew Johnson, had been impeached and almost thrown out of office (he survived his Senate trial by one vote) after two years of bitter conflict with the Republican-dominated Congress over Reconstruction.

[image error]President Grant delivers his first inaugural address. Library of Congress photo.

After briefly reciting the usual pledges of fidelity to the duties of the office, Grant made it clear that he would conduct himself very differently from his predecessor.

“On all leading questions agitating the public mind I will always express my views to Congress and urge them according to my judgment, and when I think it advisable will exercise the constitutional privilege of interposing a veto to defeat measures which I oppose; but all laws will be faithfully executed, whether they meet my approval or not,” he told the throng assembled at the Capitol to witness his inauguration.

“I shall on all subjects have a policy to recommend, but none to enforce against the will of the people. Laws are to govern all alike — those opposed as well as those who favor them. I know no method to secure the repeal of bad or obnoxious laws so effective as their stringent execution.”

Grant was the natural choice of Republicans as their presidential candidate in 1868 even though he had been resolutely apolitical during the war. His victory over New York Democrat Horatio Seymour proved surprisingly close: Grant topped Seymour by just more than five percentage points in the popular vote. Grant won overwhelmingly in the Electoral College, sweeping Reconstruction Southern states except for Georgia and Louisiana. But he lost New York and its thirty-three electoral voters to the Democrat.

Rain fell from the skies as Inauguration Day dawned but the gloomy skies eventually gave way to sun as the parade from the Capitol to the White House began, the Washington Evening Star reported. “The crowds on the streets, the balconies and the house-tops lowered their umbrellas with a feeling of relief and there was a general craning of necks in the direction of the expected procession.”

[image error]The Washington Evening Star, March 4, 1869. Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

Well-wishers who poured into the city overnight provided a festive atmosphere in the usually staid capital, according to the Evening Star. Other visitors came with less innocent motives. “Inauguration ceremonies are no more attractive to the honest people of the country than they are to the light-fingered gentry, who have wended their way hither in great numbers, in anticipation of a rich harvest,” the newspaper noted. Washington police, with the aid of detectives from New York, kept a close eye on crowds to keep pickpockets from plying their craft, the Evening Star told its readers.

Not surprisingly, much of Grant’s address focused on Reconstruction. After two years of intensely partisan conflict between Johnson and Congress, the new president urged Americans to take a calm approach toward the unresolved issues of rebuilding the defeated South. But he made it abundantly clear where he stood on those issues.

“In meeting these it is desirable that they should be approached calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectional pride, remembering that the greatest good to the greatest number is the object to be attained,” Grant said. “This requires security of person, property, and free religious and political opinion in every part of our common country, without regard to local prejudice. All laws to secure these ends will receive my best efforts for their enforcement.”

[image error]President Grant in 1869. Library of Congress.

Reconstruction would dominate Grant’s first term. Southern states resumed representation in Congress after ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment aimed at defining and guaranteeing the rights of citizenship for formerly enslaved Blacks. But he recognized Congress and the federal government needed to do more.

“The question of suffrage is one which is likely to agitate the public so long as a portion of the citizens of the nation are excluded from its privileges in any State,” Grant said. “It seems to me very desirable that this question should be settled now, and I entertain the hope and express the desire that it may be by the ratification of the fifteenth article of amendment to the Constitution.”

While the residual issues of the Civil War dominated Grant’s first term, the beginning of his presidency also pointed toward changes that would shape the politics of the Gilded Age. One involved presidential politics — Grant’s vice president was Schuyler Colfax, a former House Speaker and Indiana Republican. Colfax’s presence on the ticket reflected Indiana’s status as a battleground state and prompted Democrats and Republicans into the early 20th century to pick Hoosiers for the No. 2 spot on their presidential tickets.

Another involved monetary policy. Grant signaled his commitment to conservative views on money when he promised “To protect the national honor, every dollar of Government indebtedness should be paid in gold, unless otherwise expressly stipulated in the contract.”

Questions about money — and whether the federal government should pursue a “hard money” policy that emphasized metallic currency over the paper money that had come into use during the war and was widely popular in the West — would challenge Republicans in Grant’s second term.

But that was a long way off on March 4, 1869. Instead of looking ahead, the Evening Star marveled at how the beginning of Grant’s presidency compared to the tense circumstances surrounding Lincoln’s second inaugural.

“The Federal Metropolis, in many respects, had the appearance of a military camp,” the newspaper recalled. “This state of affairs, fortunately for the Republic and its Capital, has changed.”

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

[image error] Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

[image error] Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Caree r of James B. Weave r

August 24, 2020

The “striker:” Uriah Hunt Painter, correspondent, wirepuller — and photographer

Uriah Hunt Painter stands as a peripheral figure in the drama of the Credit Mobilier scandal. Members of Congress, the vice president, and various Washington correspondents played far more significant roles.

Nevertheless, Painter, whose nose for finding news stories that could be exploited for personal gain earned him the disdain of George Alfred Townsend, is one of the most interesting personalities associated with the scandal that rocked Washington in the winter of 1872-1873.

In the morally murky world of Gilded Age journalism, Painter stood out.

He represented the New York Sun, the Philadelphia Inquirer and — frequently — himself in the nation’s capital. He broke one of the biggest stories of the Civil War — the Union defeat at Bull Run on July 21, 1861 — but according to historian Donald L. Ritchie made sure that financier Jay Cooke knew about it first and could sell stocks ahead of the headlines that would depress the market.

After Secretary of State William Seward in 1867 concluded the treaty with Russia that resulted in the sale of Alaska to the United States, Painter tried to insinuate himself into the lobbying campaign to win congressional approval for the $7.2 million promised to the czar. He tried used his position as a correspondent for the Sun to influence the debate and fatten his pockets — although he claimed he was acting to expose corruption.

While he came from a Quaker background in Philadelphia, Painter could hardly be called pious. He cursed volubly. He was a shabby dresser. But he knew how to sniff out a chance to make some money.

When Painter heard that Rep. Oakes Ames was selling shares in Credit Mobilier, the financially lucrative construction company whose sole customer was the Union Pacific, he pursued the stock, not the story. Rather than investigate the reasons behind the sales — to cultivate support for the railroad’s interests on Capitol Hill — Painter decided he wanted to buy some of the shares.

As recounted by Ames as he testified about his stock sales before a committee led by Rep. Luke Potter Poland, Painter paid $3,000 for 30 Credit Mobilier shares.

[image error]Rep. Luke Potter Poland, R-Vt. Library of Congress.

“He became a stockholder?” Poland asked, with some incredulity.

“Yes sir; he said he was promised more, and was very indignant he did not get 50 shares,” Ames replied.

Perhaps his notoriety prompted Poland to react with surprise to the mention of his name by Ames. In the records of Poland’s investigation Painter stands out as the only person outside of Congress to whom Ames admitted selling shares in the winter of 1867-1868.

Self-dealing and profiting from proximity to power were commonplace among the correspondents who populated Washington in the years after the Civil War. But something about Painter rubbed people the wrong way.

Townsend, who wrote under the pen name GATH in the late 1860s and early 1870s, found Painter particularly loathsome. In Washington Outside and Inside, Townsend’s account of the nation’s capital in the years after the Civil War, Painter is described as “hanging on the verge of the newspaper profession for ten years or more” for the sole purpose of gleaning inside information from which he could profit.

Painter, Townsend, claimed, was the textbook example of a “striker,” a distasteful creature of Washington whose qualities Townsend committed to verse:

Slouched, and surly, and sallow-faced,

With a look as if something were sore misplaced,

The young man Striker was seen to stride

Up the Capital (sic) steps at high noontide,

And as though at the head of a viewless mob --

Who could look in his eye and mistrust it? --

He quoth: "They must let me into that job,

Or I'll bust it!"

Ames let Painter get in on the Credit Mobilier windfall, and in doing so avoided early exposure of the scandalous stock sales. It was another correspondent for the Sun, Albert M. Gibson, who broke the story wide open.

[image error]Rep. Oakes Ames.

How did Painter find out about the stock Ames was selling? Probably because he was a business partner with the two central characters in the Credit Mobilier drama. Henry S. McComb, whose suit against Ames led to Gibson’s bombshell scoop in the Sun on Sept. 4, 1872, told Townsend that he, Ames and Painter were fellow investors in a Washington canal project.

Painter’s keen ability to find a news story, historian J. Cutler Andrews has written, served him well at Bull Run. He witnessed the collapse of the Union line and traveled by freight train to Philadelphia to file his story in person to evade telegraph censorship imposed by the War Department, according to Ritchie.

With most other newspapers still reporting a Union victory, the reaction in the City of Brotherly Love to Painter’s scoop was shock — followed by anger as the newspaper was denounced for spreading seditious propaganda, Andrews writes.

By the mid-1880s, however, Painter had abandoned newspapers altogether in favor of real estate and other business ventures, according Mary M. Ison. He built the Lafayette Square Opera House, she writes, and set up Washington’s first telephone company. And he took up photography.

Painter loved gadgets, according to Ison, and embraced the new camera developed by George Eastman for Kodak in 1888. The new cameras featured paper film that allowed for quicker exposures and easy use. Photographers took their pictures, sent the camera back to Kodak where the images were developed and returned with the camera re-loaded for more photography, according to Ison.

The Library of Congress possesses a collection of Painter’s photographs. They are slice-of-life images from Gilded Age Washington. Painter’s subjects included a waffle wagon, the White House Easter egg roll and a winter scene outside the Willard Hotel.

[image error][image error][image error][image error]

From top: The White House Easter Egg roll, 1889; the Bartholdi Fountain with the U.S. Capitol in the background, 1889; a waffle wagon in front of the Treasury Department 1889; and a horse-drawn sleigh with the Willard Hotel behind it. Library of Congress.

As for Townsend, he overcame his disdain for the correspondent he dubbed the “striker.” When he built his monument to Civil War correspondents on South Mountain, Maryland, it included a list of famous scribes and photographers. The list includes Matthew Brady, Whitelaw Reid, Henry M. Stanley — and Painter.

[image error]The War Correspondents Arch at Gathland State Park in Maryland.

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

[image error] Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

[image error] Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

August 16, 2020

The brothers Washburn(e)

A pair of Midwestern lawmakers who shared the same last name (if not the same spelling of it) emerged as early and prescient critics of the Union Pacific and Credit Mobilier.

Rep. Elihu Washburne of Illinois and his brother, Rep. Cadwallader Colden Washburn of Wisconsin, both Republicans, raised early alarms about the railroad and the lucrative construction subsidiary with the exotic sounding name that became the focus of the scandal that opened the Gilded Age.

The Washburn (or Washburne, if you prefer Elihu’s spelling) brothers were among a group of three brothers from a Maine family that made their way into Congress in the middle of the 19th century. The third brother, Levi Washburn of Maine, served in Congress as a Whig and Republican from 1851 until 1861. A fourth brother, William Drew Armstrong, represented Minnesota in the House and Senate from 1881 until 1895,

[image error]Elihu B. Washburne. Library of Congress.

Elihu Washburne is well-known today as an early supporter of both Abraham Lincoln in his 1860 bid for the presidency and Ulysses S. Grant, who left Washburne’s home town of Galena to lead Union armies to victory against secessionist rebels. Elihu Washburne acted as Grant’s advocate and defender in the nation’s capital during the war.

After the war, Washburne burnished his reputation as a persistent and sometimes irritating scold about wasteful government spending.

In 1867, he was chairman of the House Commerce Committee and the longest-serving member of the House. He was respected, if not loved. His habit of lecturing House members, George Julian recalled, made him “a little unpopular” with members.

In December of that year, Washburne provided a vivid demonstration of the qualities that his colleagues found irritating.

That summer, rival factions of the Union Pacific’s board of directors were at war in a power struggle for control of the railroad and Credit Mobilier. Forces loyal to Rep. Oakes Ames and his brother, Oliver, ousted Durant as president of Credit Mobilier. The dispute was eventually settled, but not before an enraged Durant grabbed one of Ames’s supporters by the throat and had to be pulled away by Oakes Ames.

Bitter memories remained despite the settlement and in December, Rep. Henry Dawes — who was in the process of obtaining Credit Mobilier shares from Ames — proposed what seemed to be an innocuous piece of legislation. The bill would have allowed the congressionally chartered railroad to move its headquarters out of Durant’s home territory of New York to Boston or another city if the directors so chose (they didn’t until 1869 and found themselves entangled in a dispute with Wall Street speculator “Jubilee” Jim Fisk as a result).

Dawes’s bill seemed to be nothing more than routine legislative housecleaning. But Washburne seized on the opportunity to take on the railroad established to create a link with the Pacific Coast.

Washburne took the Union Pacific to task for high freight tariffs and warned his colleagues that it threatened to “crush every interest in this country” if it goes unchecked. The railroad, he charged, was imposing “enormous, and unconscionable, and unheard-of rates for freight and passage.” He wanted to amend Dawes’s bill to include language barring the railroad from charging more than twice as much for freight or passenger service as railroads east of the Mississippi.

The eruption flustered Dawes — “I did not expect the surprise or indignation of the gentleman from Illinois ” — but he nevertheless won passage for the measure. Even so, Washburne’s outburst was an early sign of the discontent brewing among House members and in the public at large with the railroads involved in the transcontinental project and the industry in general.

While Elihu Washburne took issue with the railroad, his brother offered a more specific — and for Ames and Union Pacific officials, more troubling — critique of Credit Mobilier.

[image error]Library of Congress.

Nominally a construction company hired by the Union Pacific to build the railroad, Credit Mobilier in fact played another role as a way for railroad investors to profit before the railroad was completed.

Credit Mobilier overcharged the railroad for construction work and took payment in company stocks and bonds. The Union Pacific was barred by Congress from selling shares below the value at which they were issued, but Credit Mobilier faced no such prohibition. The arrangement proved enormously profitable for Credit Mobilier investors, many of whom also were major stockholders in the railroad. By one estimate, Credit Mobilier made almost $30 million off the so-called “Oakes Ames contract” it reached with the railroad in 1867.

At about the same time, Ames began selling Credit Mobilier stock at steeply discounted prices to select colleagues such as Dawes. His motive for doing so, it would be revealed several years later by the New York Sun and subsequent investigations, was to build support for the Union Pacific on Capitol Hill. “We want more friends in this Congress,” Ames famously explained in a letter to fellow investor Henry S. McComb. Dawes’s intervention on behalf of the railroad suggests Ames’s strategy proved somewhat successful.

Cadwallader Washburn seemed to know something was going on, probably through lobby chatter or gossip over dinner at one of the city’s hotels or boardinghouses where lawmakers stayed when they were in town.

Like brother Elihu, Cadwallader was concerned about railroad tariffs. When he spoke to the House on March 20, 1868, he began by defending his proposal to create a three-member board consisting of the sectary of war, the secretary of the interior and the attorney general to set passenger and freight rates on the Pacific railroads (the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific).

[image error]Rep. Cadwallader Colden Washburn. Library of Congress.

Washburn warned about the speculative fever surrounding railroad construction sweeping the country: “It is a characteristic of our people that when they want a thing they will have it, cost what it may, but often, when too late, have cause to regret their own short-sightedness and lament their extravagance and folly.”

But he was particularly alarmed by Credit Mobilier’s dual role as a construction company and financial vehicle for Union Pacific investors. He did not name members of Congress who bought shares from Ames (one, James Brooks of New York, got his stock from Durant). But his remarks about Credit Mobilier seemed directly aimed at colleagues who bought the company’s stock in the expectation of turning a tidy profit.

Congress would have rightly objected had the railroad’s investors contracted with themselves to build the road, Washburn noted. Credit Mobilier allowed them to do just that, however, albeit indirectly. Credit Mobilier “practically contracts with itself to build the road, and … the enormous figures they exhibit as representing the cost of building the road are absolutely fictitious.”

The alarms raised by the brothers Washburn(e) eventually found a wider audience. The following year Charles Francis Adams Jr. described Credit Mobilier’s reach into Congress as a “source of corruption in the land” that threatened to become “a resistless power in its legislature.” The New York Tribune followed up with similar criticism in its editorial columns — although a year earlier the newspaper passed on breaking the story of the stock sales in Congress.

Credit Mobilier and its reach on Capitol Hill remained an open secret. Not until Sept. 4, 1872, when the Sun blasted details of Credit Mobilier’s business operations and Ames’s stock sales to his colleagues across its front page, did the story gain traction. When it did, it marked a turning point in the nation’s politics.

[image error]The New York Sun, Sept. 4, 1872,

[image error]Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Available at amazon.com

August 8, 2020

George Julian and “the King of Frauds”

The final installment in this series on George Julian and Political Recollections.

The Credit Mobilier scandal erupted shortly after George Julian left Congress, but he was familiar with many of the principals players in the drama that ushered in the Gilded Age.

[image error]Rep. George Julian. Library of Congress.

His last term in Congress concluded in 1871, but the central events of the scandal — the sale by Rep. Oakes Ames, R-Mass., of shares in the profitable construction subsidiary of the Union Pacific railroad to other members of Congress — occurred in the winter of 1867-1868 while he was still on Capitol Hill.

In Political Recollections, his memoir of his remarkable life in politics, Julian makes his disdain for corruption plain. But when it comes to the scandal that ushered in the Gilded Age, he offers a very guarded assessment.

“The history of its connection with American politics and politicians,” Julian writes of Credit Mobilier, “forms an exceedingly interesting and curious chapter.”

The sale of Credit Mobilier stock by Ames and Thomas C. Durant had been an open secret on Capitol Hill for years. But it burst into the headlines on Sept. 4, 1872, when the New York Sun published a lengthy expose based on transcripts of court depositions under the headline “King of Frauds.”

[image error]The New York Sun, Sept. 4, 1872

The story detailed testimony by Henry S. McComb, a fellow investor in the Union Pacific who was suing Ames to claim shares of Credit Mobilier to which he believed he was entitled. In the course of his testimony, McComb identified as many as 11 members of Congress who bought the valuable shares at steeply discounted prices — or were able to obtain the shares against promises they would pay Ames after they sold the stock or received dividends.

As McComb pressed Ames for more shares, the Massachusetts Republican wrote three ill-advised letters in which he explained that he was selling the stock to extend the influence of Credit Mobilier on Capitol Hill. “We want more friends in this Congress,” Ames confided in one, “and if a man will look into the law (& it is difficult to do so unless they have an interest to do so) he cannot help being convinced that we should not be interfered with.”

[image error]Henry S. McComb.

The disclosure shocked the Chicago Tribune, which pointed to it as evidence of the need for a “general cleaning out of the whole establishment.”

Julian was known to his contemporaries as a master of invective. “There were few men I have known who could use the English language more successfully in the way of bitterness toward his adversaries,” wrote Jeremiah Wilson, like Julian and Indiana Republican and one of the lead investigators of the scandal.

Therein may be the key to his measured assessment of the affair that consumed Washington in the winter of 1872-1873. Several of the principals in the scandal had been political allies and friends. Horace Greeley, one of his political heroes — a man he followed out of the Republican Party and into the ranks of the Democrats — seized on the scandal as evidence of widespread rot in Washington that required “purification.”

Julian had friends on both sides.

He regarded Ames, for example, with fondness. “Oakes Ames was one of the members of the House with whom I was best acquainted,” Julian writes. He adds:

I thought I knew him well, and I never had the slightest reason to suspect his public or private integrity. Personally and socially he was one of the kindliest men I ever knew, and I was greatly surprised when I learned of his connection to the Credit Mobilier project.

John Bingham, the Ohio Republican who helped write the Fourteenth Amendment, numbered among those who bought Credit Mobilier shares from Ames. When he testified before the committee investigating the scandal, Bingham conceded that he bought the stock and profited handsomely from the transaction. Moreover, he acknowledged that he wrote legislation that helped Ames and his Union Pacific allies by moving the headquarters of the congressionally chartered railroad from New York to Boston. Bingham insisted that the committee include a text of the bill in its record.

“He was often dogmatic and lacking in coolness and balance, but in later years he showed uncommon tact in extricating himself from the odium threatened by his connection with the Credit Mobilier scheme,” Julian wrote of Bingham.

Julian encountered James Brooks long before he met Ames or Bingham — and long before Brooks was a Democrat. As a young man, Julian saw Brooks — then a Whig — campaigning for William Henry Harrison in Indiana in 1840. Brooks became a Democrat as the Whig Party collapsed in the 1850s representing New York. Unlike most of the others implicated in the scandal, he bought his shares from Thomas C. Durant.

[image error]Rep. James Brooks. Library of Congress.

“He was a man of ability … and a bitter partisan” who viewed Black Americans with contempt, Julian remembered. “[B]ut I never saw any reason to doubt his personal integrity, and I think the affair that threw so dark a cloud over his reputation in later years was a surprise to all who knew him.”

These sober, charitable assessments of the principals in the scandal might suggest that Julian thought it amounted to nothing. But that would be wrong.’

Regarding the figures involved in the affair he writes:

The fate of the men involved in it seems like a perfect travesty of justice and fair play. Some of them have gone down under the waves of popular condemnation. Others, occupying substantially the same position, according to the evidence, have made their escape and even been honored and trusted by the public, while still others are still quietly whiling away their lives under the shadow of suspicion.

And he was correct. Ames and Brooks went to their graves with their reputations permanently scarred soon after the Forty-Second Congress adjourned and the investigation into the scandal entered the history books. James A. Garfield, who bought shares from Ames, went to the White House. Bingham, as Julian noted, escaped with his reputation intact. Schuyler Colfax, Julian’s fellow Hoosier, was vice president when it was revealed that he numbered among the beneficiaries of Ames’s largess. His attempts to clear his name failed miserably, and his reputation never recovered.

When it came to Credit Mobilier, justice was haphazard at best.

[image error]Rep. Oakes Ames.

Although he does not address Credit Mobilier except in the most general terms, Julian ends his memoir with a warning about the direction of American politics that was clearly informed by the same concerns that troubled Luke Potter Poland, the Vermont Republican who led the investigation into the scandal. As the House debated whether to sanction Brooks and Ames for their role in the scandal, Poland warned that Credit Mobilier raised disturbing questions about the nefarious sway of “money power” in the halls of government.

Writing a decade later about the state of American politics, Julian saw the same danger.

“Commercial feudalism, wielding its power through great corporations which are practically endowed with life offices and the right of hereditary succession and control the makers and expounders of our laws, must be subordinated to the will of the people,” Julian declared.

On the big issues raised by the Credit Mobilier scandal, there was no doubt where Julian stood.