Robert B. Mitchell's Blog, page 5

July 30, 2020

“Conspicuous personalities”

Third in a series on Political Recollections, the memoirs of George Julian of Indiana.

[image error]George Julian. Library of Congress.

Over the course of a political career that began in the song-and-hard cider days of William Henry Harrison’s 1840 presidential campaign and extended well into the Gilded Age, George Julian met an astonishing number of prominent figures.

[image error]Henry Clay. Library of Congress.

Henry Clay: Few figures dominated antebellum politics like Henry Clay, the Kentucky statesman who embodied the Whig Party in the 1840s but who whose repeated attempts to win the presidency ended in failure. Julian campaigned for Clay in 1844 when the Kentucky statesman was the Whig nominee for president and met him in 1850 in Washington.

Clay was attempting to forge legislation that would patch over the emerging crisis over slavery when Julian numbered among a delegation that called on him at the National Hotel. “He received us with the most gracious cordiality, and perfectly captivated us all by the peculiar and proverbial charm of his manners and conversation,” Julian remembered. “I remember nothing like it in the social intercourse of my life.”

Julian’s believed Clay’s desire to reach a compromise that would have preserved slavery as the price of keeping the Union together was “radically wrong” but nevertheless found himself “drawn toward him by that peculiar spell which years before had bound me to him as my idolized political leader.” In his speeches on the Senate floor, Julian recalled, Clay displayed what he said was a piece of George Washington’s coffin as he argued for sectional reconciliation. Clay’s “devotion to the Union,” Julian believed, “was his ruling passion.”

Zachary Taylor: Julian broke with the Whigs in 1848 to join the ranks of the anti-slavery Free-Soil Party. In that year the Whigs nominated Taylor, a hero of the Mexican War and enslaver who had never voted and did not seem to hold positions on any of the issues of the day.

Julian was appalled.

“The spectacle was a melancholy one, since it demonstrated the readiness of this once-respectable old party to make complete shipwreck of everything wearing the semblance of principle, for the sake of success,” he wrote. During the presidential campaign of that year, Julian recalled, he attacked Taylor relentlessly.

[image error]Gen. Zachary Taylor. Library of Congress.

Julian must not have had high expectations when, along with two others, he ventured to the Executive Mansion to meet the president. What he found surprised him.

“I decidedly liked his kindly, honest, farmer-like face, and his old-fashioned simplicity of dress and manners,” Julian recalled. Taylor was not eloquent — indeed his “whole demeanor” illustrated “that he had reached a position for which he was singularly unfitted by training and experience, or any natural aptitude.” But Taylor possessed a simple patriotism, Julian believed — a belief confirmed when Taylor threatened to hang traitors who threatened secession if territories obtained after the Mexican War were admitted to the Union as free states.

“I believe his dying words in July, ‘I have tried to do my duty,’ were the key-note of his life, and that in the Presidential campaign of 1848, I did him much, though unintentional, injustice,” Julian admitted.

[image error]Abraham Lincoln. Library of Congress.

Abraham Lincoln: Julian’s first meeting with Lincoln, recounted in a previous blog post, occurred in Springfield, Ill., as the president-elect prepared to take office. Julian was skeptical of the Kentucky-born former Whig, many of whose backers were far less concerned about ending slavery than preserving the Union.

But the Indiana congressman was won over by Lincoln’s humor and charm. “His face, when lighted up in conversation, was not unhandsome, and the kindly and winning tones of his voice pleaded for him like the smile which played about his rugged features,” Julian recalled.

In the years to come, the former Free Soil lawmaker numbered among the Radical Republicans who strongly opposed Lincoln’s plans for Reconstruction. But Julian believed the president would not have insisted on his plan for returning rebellious Southern states back to the Union in the face of congressional opposition.

It became a moot point on April 15, 1865, when Lincoln died after being shot by John Wilkes Booth. One of the most dramatic sections of Julian’s book details what he saw in the hours after word of the shooting swept Washington.

The city was at once in a tempest of excitement, consternation and rage. About seven and a half o’clock in the morning the church bells tolled the President’s death. The weather was as gloomy as the mood of the people, while all sorts of rumors filled the air as to the particulars of the assassination and the fate of Booth. [Vice President Andrew] Johnson was inaugurated at eleven o’clock on the morning of the 15th, and was at once surrounded by radical and conservative politicians, who were alike anxious about the situation.

[image error]Andrew Johnson, Library of Congress.

Andrew Johnson: Julian and the man who became the seventeenth president were once allies. In the Thirty-First Congress they saw eye-to-eye on making government-owned land in the west available to homesteaders. “Although loyal to his party,” Julian wrote of Johnson, “he seemed to have little sympathy with the extreme men among its leaders, and no unfriendliness to me on account of my decided anti-slavery opinions.”

In 1864, when Lincoln chose Johnson as his running-mate, Julian foresaw trouble. Johnson was a “decided hater” of Blacks and discounted slavery as the underlying cause of the war. Nevertheless, Julian and his radical allies were cheered in the days after the assassination when Johnson declared “Treason must be made infamous, and traitors must be impoverished.”

But in the weeks and months to come, Julian’s early misgivings about Johnson were confirmed as the Tennessean backpedaled on his commitment to punish secessionists. Johnson moved quickly to re-admit Southern states and pardoned Confederates so profusely that one Northern newspaper wondered shortly after the new president took office if “the whole confederacy will apply for pardon before the 1st of August.”

By the winter of 1868, Johnson and Congress were completely alienated. One attempt to impeach Johnson had already failed, but when the president dismissed Edwin M. Stanton as secretary of war, the House moved rapidly — and overwhelmingly — to impeach Johnson. Julian wholeheartedly supported impeachment and called Johnson a “recreant usurper” on the House floor.

In his memoir, Julian bemoans the “acts of executive lawlessness” that led the House to impeach the president but is also critical of the “frenzy” that colored the proceedings. “Andrew Johnson was no longer merely a ‘wrong-headed and obstinate man,’ but a ‘genius in depravity,’ whose hoarded malignity and passion were unfathomable,'” Julian writes. Johnson’s impeachment trial — in which he avoided removal from office by a single vote — “connected itself with all the memories of the war, and involved the Nation in a new and final struggle for its life.”

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

[image error] Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age

[image error] Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

July 18, 2020

The disillusioned Whig

Second in a series on Rep . George Julian of Indiana.

In 1840, a political wildfire swept across the states of the Old Northwest. Gen. William Henry Harrison, the Whig party’s presidential candidate, generated fervor rarely seen in presidential politics. Voters rallied to his standard, eager to embrace a candidate viewed as a common man challenging the aristocratic and out-of-touch Democratic incumbent, Martin Van Buren.

And George Julian was all in.

Political Recollections, Julian’s fascinating memoir of his life in politics, begins with a compelling description of the 1840 Whig campaign, in which the imagery of the party’s common-man “log cabin” candidate who favored hard cider over more aristocratic fermented beverages, took the nation by storm.

[image error]Rep. George Julian. Library of Congress.

“I knew next to nothing of our party politics,” Julian recalled of his days as a 23-year-old Whig foot soldier. “[B]ut in the matter of attending mass meetings, singing Whig songs and drinking hard cider, I played a considerable part in the memorable campaign of that year.”

Julian’s self-effacing candor about his lack of political sophistication is an early sign of what makes Political Recollections such a remarkable book. He is willing to deal frankly — and often critically — with the parties, personalities and issues he encountered during a life in politics that began with Harrison, spanned the Civil War and extended into the 1880s.

In 1840, the enthusiasm was real. Julian recounts riding on horseback 150 miles “through mud and swamps” to attend a giant rally at the Tippecanoe battlefield site in central Indiana where Harrison had defeated Native Americans allied with Tecumseh in 1811. Among those Julian encountered, he recalled, was James Brooks — then a Whig partisan who decades later as a leading House Democrat was one of the principal figures in the Credit Mobilier scandal.

“The gathering was simply immense,” Julian wrote. “Large shipments of hard cider had been sent up the Wabash by steamer, and it was liberally dealt out to the people in gourds, as more appropriate and old-fashioned than glasses.” On Sept. 12, Julian headed to Dayton, Ohio, where he attended a rally at which Harrison spoke. Julian estimates as many as 200,000 were in attendance.

[image error]A campaign poster depicting scenes from the life of Gen. William Henry Harrison. Library of Congress.

“He was the first ‘great man’ I had seen, and I succeeded in getting quite near him,” Julian remembered. “[A]nd, while gazing into his face with an awe I have never since felt for any mortal, I was suddenly recalled from my rapt condition by the exit of my pocket-book.”

The incident foretold Julian’s relationship with the party to which he gravitated. There were genuine grievances with the Van Buren administration — in particular the Panic of 1837 and corruption in the New York customs house involving Samuel Swartout, Julian notes — but the party that year ran a vacuous campaign to elect Harrison and John Tyler, the conservative Virginian who was the party’s vice-presidential choice.

The short-lived Whig Party emerged in the 1830s in opposition to the Democratic Party personified and led by Andrew Jackson. Whigs favored tariffs to protect domestic industry, government support for harbors and river transportation (and later railroads) to promote economic development. Many abhorred the hyper-partisanship of Jacksonian Democrats but were willing to embrace it to win the presidency. Hence the cynical pragmatism of 1840.

Harrison lacked any relationship with the Whig Party and was, to the extent he had a political views, “an old-fashioned States Rights Democrat of the Jeffersonian school,” Julian observes. Tyler’s connection to the Whigs was even more attenuated. Of the ticket, Julian writes:

There was one policy on which they were perfectly agreed, and that was the policy of avowing no principles whatever; and they tendered but one issue, and that was a change of the national administration.

The campaign of 1840, little more than a “grand national frolic,” in Julian’s view, succeeded in carrying Harrison to victory. But the Whigs had little to celebrate. Harrison died soon after taking office — and his successor, Tyler, alienated Whigs and supported annexation of Texas.

Julian remained a Whig through 1844, when the party nominated Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay was recognized as “the very embodiment of Whig principles,” Julian notes, but struggled to find a position on slavery that satisfied Northern opponents of human bondage without offending its Southern champions.

[image error]Henry Clay. Library of Congress.

Julian conceded slavery did not figure prominently in his thinking in 1840 but had become far more significant by 1844. “This came of my Quaker training, the speeches of [John Quincy] Adams and [Joshua] Giddings, the anti-slavery newspapers, and the writings of Dr. [William Ellery] Channing, of which I had been reading with profound interest since the Harrison campaign.”

For Julian, the primacy of the slavery issue required wholehearted opposition to Democrat James K. Polk, whose views on the annexation of Texas the Hoosier regarded as a certain prelude to the expansion of slavery and war with Mexico. In 1848, when the Whigs nominated Louisiana slaveholder and Mexican War hero Zachary Taylor for president, Julian concluded he could no longer reconcile his anti-slavery convictions with continued support of the Whig Party.

“After the presidential election of 1844, I resolved I would never vote for another slaveholder, and the course of events and my own reflections had constantly strengthened this purpose,” he remembered. Julian attended the Buffalo convention of the nascent Free-Soil Party and ran for Congress as the nominee of the third party.

Julian’s disillusionment with the Whig Party reflected what proved to be its fatal weakness: its failure to successfully respond to the growing tumult over slavery. Southern Whigs showed no interest in abandoning the institution; Northern Whigs who opposed slavery subordinated their principles to their desire to win the presidency. Ironically, Julian’s decision to leave the party reflected a Whig belief that had faded by the late 1840s — the importance of putting individual conscience ahead of party interest.

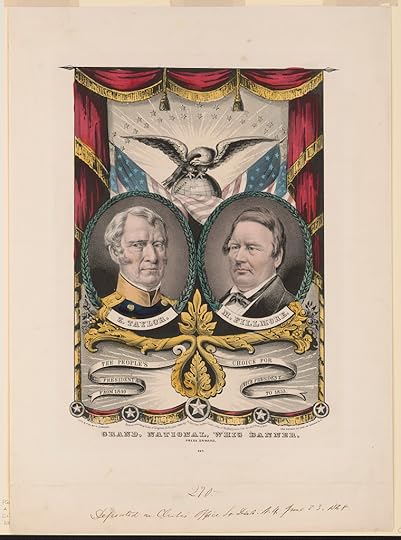

Campaign poster for Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. Library of Congress.

Campaign poster for Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. Library of Congress.Whigs and Democrats vilified him for his change of partisan affiliation. “I was threatened with mob violence by my own neighbors, and treated as if slavery had been an established institution” in Indiana, he recalled, but he was undeterred — and he was successful.

Julian served one term before he was defeated for re-election in 1850 and ran as the Free-Soil vice-presidential nominee in 1852.

But that was only the beginning. Julian returned to the House in 1861 as a Republican. For the next decade he played an influential role on Capitol Hill, where he served with Sen. Ben Wade of Ohio on the Joint Committe on the Conduct of the War.

The innocent days of hard cider and song were by then a distant memory.

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

[image error] Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

[image error]

[image error] Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver

July 12, 2020

Memoirs of an eventful political career

Editor’s note: I am hoping to spend a little time over the next several weeks reviewing the remarkable memoirs and political career of George Julian of Indiana, whose life in politics began at the dawn of the Whig Party and continued well into the Gilded Age.

George Washington Julian took his seat in the Thirty-First Congress on March 4, 1849. The representative from Indiana came to Washington in the same election that put Gen. Zachary Taylor, a nominal Whig, into the Executive Mansion.

[image error]

George W. Julian. Library of Congress.

Taylor died 16 months later after gobbling a bowl of cherries on a hot summer day and washing it down with milk (yuck). Julian became a fixture on Capitol Hill as a committed Abolitionist, Radical Republican and — at the end — party dissident who backed Horace Greeley, the famous editor of the New York Tribune and Democratic candidate for president, in 1872 against incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant.

On Capitol Hill, Julian participated in and witnessed the divisive debates over slavery and secession that preceded the Civil War. When Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency following the assassination of Lincoln and attempted to scuttle efforts to rebuild the South and protect the rights of the formerly enslaved, he became an outspoken critic of the president and called for his impeachment. Julian remained in Congress into the early 1870s and was well-acquainted with many of the figures caught in the Credit Mobilier scandal.

That is a brief outline of an eventful career. Julian himself, however, provided a much fuller and wonderfully engaging account of his life and times in one of the most interesting political memoirs I have encountered.

Many of the politicians during the Gilded Age were the subject of fawning biographers or penned memoirs packed with platitudes and devoid of insight. Adlai E. Stevenson of Illinois, the one-time Greenback ally who ran as Democrat Grover Cleveland’s vice-presidential running mate in 1892, put together a volume of reminiscences titled “Something of Men I Have Known” that might have been more accurately called “Nothing of Men I Have Known.” Stevenson seemed unwilling or unable to say anything illuminating about the notable figures he encountered. They were all unblemished statesmen capable of soaring oratory, if he was to be believed.

Julian was far more candid in Personal Recollections, published in 1883. Consider his description of Johnson, nominated as Lincoln’s running mate at the 1864 Union convention in Baltimore:

I had become intimately acquainted with him while we were fellow members of the Committee on the Conduct of the War, and he always scouted the idea that slavery was the cause of our trouble, or that emancipation could ever be tolerated without immediate colonization. In my early acquaintance with him I had formed a different opinion of him; but he was, at heart, as decided a hater of the negro and of everything savoring of abolitionism, as the rebels from whom he had separated.

That assessment — concise, unblemished, and accurate — offers a taste of Julian’s way with words — a talent that makes Personal Recollections enjoyable reading and the Hoosier a compelling political figure. His successor, Jeremiah Wilson (familiar to students of the Credit Mobilier affair as the chairman of one of the committees that investigated the scandal) believed Julian’s facility with the language was a double-edged sword.

[image error]

Andrew Johnson, Library of Congress.

“There were few men I have known who could use the English language more successfully in the way of bitterness toward his adversaries,” Wilson recalled. “[W]hile he made and retained a large number of friends, the ability with which he attacked the Democratic party and the friends of slavery and the injury he inflicted on that institution were the means of making for him many enemies.”

Above all else, Julian was a clear-eyed, candid and sometimes caustic witness to history. Elected to Congress as a member of the anti-slavery Free Soil Party, Julian became a Republican and attended the party’s first convention, at which John C. Fremont was nominated. Looking back, Julian hailed the party’s first presidential campaign but stopped short of praising its candidate.

“He was known as an explorer, and not as a statesman,” Julian wrote. “If he had succeeded, with mere politicians in his cabinet, a Congress against him, and only a partially developed anti-slavery sentiment behind him, the cause of freedom would have been in fearful peril.”

He formed a more positive, but not entirely uncritical, opinion of Lincoln. Julian traveled to Springfield to meet the president-elect in 1861 and found him “full of anecdote and humor.” He struck Julian at the time as “more emphatic” than expected on slavery. But Julian was disappointed in Lincoln’s equivocal response to Greeley’s famous open letter, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” in which the editor of the New York Tribune urged the president to make the end of slavery a primary objective of the war effort.

[image error]

Abraham Lincoln. Library of Congress.

Lincoln’s response — “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it” — struck Julian as preposterous. “To argue that we were fighting for a political abstraction called the Union, and not for the destruction of slavery, was to affront common sense, since nothing but slavery had brought the Union into peril, and nothing could make sure the fruits of the war but the removal of its cause.”

On the fascinating question of what Lincoln might have done regarding Reconstruction had he lived, Julian offers an interesting speculation. He concedes that Lincoln favored a conservative approach to readmitting Southern states that would have restored the antebellum elite and left formerly enslaved Blacks without any say in how the states would be governed. Julian numbered among the Radical Republicans who were unalterably opposed to the president’s lenient plan. But Lincoln “was never an obstinate man,” Julian notes, and he would have been unlikely to “wrestle with Congress and the country in a mad struggle to get his own way.”

The same could not, of course, be said of Johnson. Julian was at the forefront of the movement to impeach the president, who infuriated the House with his disinterest in protecting the South’s Black population. The tipping point came when he moved to dismiss Edwin Stanton as Secretary of War in February, 1868.

It was one of the rare occasions in which Julian lost control of the language he used so successfully. Johnson “has done an act which on its face settles the question of law, and shuts us up to the absolute necessity of taking the recreant usurper by the throat,” Julian raged on the House floor.

[image error]

Johnson survived the Senate impeachment trial by a single vote and limped out of office in 1869. But Julian was only slightly less hostile to his successor, Grant. The modest general was widely regarded as a hero for his successful prosecution of the war against secession, but Julian took a different view.

The idea of his nomination was exceedingly distasteful to me. I personally knew him to be intemperate. In politics he was a Democrat. He did not profess to be a Republican, and the only vote he had ever given was cast for James Buchanan in 1856, when the Republican party made its first grand struggle to rescue the Government from the clutches of slavery. Moreover, he had no training whatsoever in civil administration, and no one thought of him as a statesman.

This was not an entirely accurate understanding of Grant, whose views (like those of John Logan and many others in the Union Army) evolved dramatically during the war. But it foreshadowed Julian’s actions in the years ahead. He drew close to Greeley as the Tribune editor became increasingly disillusioned with Grant and the Republican Party.

[image error]Ulysses Grant and Schuyler Colfax in 1868. Library of Congress.

Julian attended the convention of Liberal Republicans in Cincinnati in May 1872 at which Greeley was nominated for president and then crossed the aisle to join Democrats who selected their former nemesis as their standard-bearer.

The campaign, of course, went badly for Julian’s candidate. Greeley carried only six states — five of which were below the Mason-Dixon line. The old editor died before the votes of the Electoral College were counted — and the man whose quixotic campaign for the White House was mocked and scorned by champions of Grant was hailed posthumously as a hero. Grant himself led the funeral procession in New York.

Julian, however, was unmoved. “It is easy to speak well of the dead,” he wrote. “It is very easy, even for base and recreant characters, to laud a man’s virtues after he has gone to his grave and can no longer stand in their path.”

Books by Robert B. Mitchell

[image error]Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

[image error] Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

April 28, 2020

Library of Congress puts papers of three presidents online

The days of researchers burrowing for hours in dusty archives are slowly coming to an end. The Library of Congress has put the papers of Andrew Johnson, Chester Arthur and William McKinley online. Here’s the blog post by the library’s Michelle Krowl announcing the digital archive: https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2020/04/papers-of-three-presidents-digitized-now-online/

January 25, 2020

Bloody shirts and gold bugs

Lexicographer, n. A pestilent fellow who, under the pretense of recording some particular stage in the development of language, does what he can to arrest its growth, stiffen its flexibility and mechanize it methods. — Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary.

So begins one of the longest – if not the longest – entries in The Devil’s Dictionary. It is an example of Bierce’s cynical humor that he devotes so much verbiage in his own dictionary to mock the very act of recording words and their meanings.

There is no doubt, however, that the politics of the Gilded Age had its own language that requires definition and explication for the modern reader. Some of the words and phrases commonly employed in the second half of the 19th century have dropped completely from use. Who refers conversationally to the “Crime of ’73” or “gold bugs” anymore?

Herewith, the first in an occasional and by-no-means complete compilation of words and phrases that regularly occur in the headlines and oratory of the Gilded Age:

Bloody shirt: When employed by James B. Weaver in the late 1850s, the phrase referred to the bloodied garment of an Iowa preacher whipped and beaten in Texas for sharing the gospel with slaves. By the 1880s it had come to mean something entirely different – a hollow and hypocritical appeal to the memory of Union valor invoked for political purposes.

The evolving meaning of the phrase parallels the fortunes of Reconstruction and its ebbing support in the North. In 1872, Indiana supporters of Horace Greeley, the Democratic nominee running against President Grant, mocked Republican Sen. Oliver Morton for “flaunting the bloody shirt of the rebellion” and claiming that “the was is not yet ended.” Two years later, with voters preoccupied by the economic crisis triggered by the Panic of 1873, Democrats rode to one of the greatest wave elections to retake control of the House and Republicans realized the “bloody shirt could no longer control the outcome of an election,” according to historian Kenneth Stampp.

[image error]

Puck lampoons the bloody shirt, Sept. 2, 1885. Library of Congress.

Yet, even with Reconstruction in the past, it remained a staple of political discourse. In 1884, Republicans picked Sen. John Logan of Illinois as the party’s vice-presidential candidate. Eight years earlier, according to William Safire, Logan declared in the Senate that Republicans would stop invoking the specter of the bloody shirt only when Democrats “stop staining the shirt” with the blood of murdered black Republicans. But the appetite for such rhetoric had all but disappeared by the time Logan was a candidate for the second-highest office in the land. Voters, the Ottawa, Ill., Free Trader noted, “are tired of the ‘bloody shirt’ and inclined to look upon sectional agitation with suspicion as an expedient to disguise other weak points.”

Burchard: For a brief period in the late 1880s, the name of a Presbyterian clergyman came to be used as shorthand for an 11th-hour gaffe. In the closely fought election of 1884, in which James G. Blaine was the Republican presidential candidate, Rev. Samuel Burchard denounced the Democratic Party as the champion of “rum, Romanism and rebellion.” The alliterative phrase, delivered at a gathering in New York on Oct. 29, managed to offend several groups at once — Catholics, foes of prohibition and Democrats who were loyal to the Union during the Civil War — and helped swing the election to Democrat Grover Cleveland.

Four years later, Cleveland himself faced an 11th-hour crisis of his own – the so-called Murchison letter. The explosive story charged that the British ambassador, answering a letter purported to have been written by one Charles F. Murchison, appeared to endorse Cleveland’s re-election because of his sympathy for British interests. The press – particularly Democratic newspapers – were quick to call this a “Burchard.”

“The expected Burchard is not unlikely to prove a Boomerang,” The Washington Post predicted. “Burchadism to be effective must be touched off at the right moment, like a fuse.”

The Democratic St. Paul Globe took a similar line. “The present Republican Burchardism is neither sincere nor a surprise. It is simply a badly put-up job in the eyes of every one, and moreover, sagacious men know that the American people are never carried off by the same sensation twice.”

As it turned out, Cleveland supporters were whistling past the graveyard. The correspondence resonated in New York, where Irish Americans remained deeply hostile to Britain. Cleveland’s Republican opponent, Benjamin Harrison of Indiana, carried the Empire State and won the election. Perhaps that is why “Burchard” and its cousin, “Burchardism,” quickly faded as a synonym for gaffe.

Crime of ’73: Invoked by advocates of paper money and the expanded use of silver to refer to the demonitization of silver in the Coinage Act of 1873. This bit of routine legislation passed with little notice or debate at the time but became the trigger for all sorts of conspiracy theories by Agrarian radicals through the rest of the century.

[image error]

The Midland Journal, Rising Sun, Md., Aug. 19, 1892. Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

“The law of 1873 was passed in the perfunctory fashion common with routine legislation,” historian John D. Hicks has noted in his study of populism. But Agrarians believed its passage was engineered by wealth financial interests to protect the value of gold. “It went through the two houses like a thief in the night,” Weaver wrote in A Call to Action, “making just enough noise to arouse the inmates if they had been awake, and yet not enough to attract the attention of those who were dull of hearing and unduly given to slumber.”

Credit Mobilier: Whole books (ahem) have been written about the complicated scandal that dominated the headlines in the winter of 1872-1873. The phrase itself became synonymous with insider dealing during the off-year elections of 1873, when Democrats seized on the affair and Republicans put as much distance as possible between themselves and the scandal.

In their party platform, Minnesota Republicans in July denounced “all Credit Mobilier transactions, whatever be their form.” Their brethren in Iowa and Oregon used similar language. In Ohio, Republican Gov. Edward F. Noyes boiled down the scandal thusly: “[I]t is only necessary to say that it was an unmitigated swindle of the Government, without excuse or palliation. The whole thing was corrupt in its inception, and scandalous in its outcome.” Noyes’s eloquence did him little good – he was defeated in the fall by Democrat William Allen.

Gold bug: Like the “Crime of ’73,” “gold bug” reflected the preoccupation with monetary issues that dominated the politics of the Gilded Age. The phrase was meant to be an uncomplimentary way to describe supporters of the gold standard, which kept money tight and contributed to the deflationary pressures that angered Agrarian radicals and their supporters.

[image error]

A cartoon from Puck in 1896 showing William Jennings Bryan leading his Populist supporters. One of the banners decries “The Institutions of the Gold Bugs.” Library of Congress.

The Los Angeles Herald offered an excellent example of its meaning in a March 20, 1890 editorial on a speech by Sen. Daniel Voorhees, D-Ind., in which “the tall Sycamore” endorsed free trade, an easing of tight money policies and “the suppression by law of gambling in futures.” “Most of these propositions are sound, and some eminently so, but they are as far off as the millennium as long as the New York gold bug can keep his grasp upon the throat of the nation.”

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon.com

[image error]

[image error]

Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver

January 20, 2020

The Great Quadrangular Debate of 1893

[image error]

Note: Janice M. Harbaugh, a devoted student of Iowa history, has performed a great service with the republication of The Great Quadrangular Debate through her Raspberry Ridge Publishing imprint. Originally published in 1893 by The Farmer’s Tribune in Des Moines, Iowa, the booklet consists of speeches given by Democrat Henry Watterson, Populist James B. Weaver, the Rev. Russell Conwell and Republican S.L. Woodford of Massachusetts. More of a lecture series than a debate, the event was held at the Philadelphia Baptist Temple under the auspices of the Chatham Literary Union from March 24-April 13. The Great Quadrangular Debate: Philadelphia 1893 is available at amazon.com.

—

In the early spring of 1893, four speakers appeared in Philadelphia to weigh in on a big question: “Which offers the best practical political means for the benefit of the workingmen of this country – the Democratic party, the Republican party, the People’s party or the church?”

The speakers — Col. Henry Watterson, long-time Democrat and publisher of the Louisville Courier-Journal; James B. Weaver, the Populist candidate for president in 1892; Rev. Russell H. Conwell of Philadelphia, the founder of what became Temple University; and Republican S.L. Woodford of Massachusetts — did not disappoint.

Over the course of three weeks at the Baptist Temple of Philadelphia, Watterson, Weaver, Conwell and Woodford traded views on that question and in the process debated others in an event that vividly illuminated the politics of the era.

The occasion for this intellectual sparring contest was a so-called Quandrangular debate organized by the Chatham Literary Union. Such events were held in a number of the cities in the early 1890s, according to Janice M. Harbaugh, whose Raspberry Ridge Press has reprinted speech transcripts of the event published by the Farmer’s Tribune in Des Moines in 1893.

This was not at all like the debates we have come to know in the 21st century. Participants did not appear on the same night but individually over the course of three weeks. They delivered speeches rather than answered questions. They responded to points made by other speakers based on transcripts, but there were no in-person back-and-forth exchanges. There were applause lines but no pithy rejoinders. This was a contest of ideas rather than soundbites.

The debate came at a critical moment in the last decade of the 19th century. Voters returned Grover Cleveland to the White House in November, but his mandate was not overwhelming. Discontent on the nation’s farms and ranches drove voters to the Populists. Labor strife at the Homestead Steel plant in western Pennsylvania erupted in July 1892. The devastating Panic of 1893 was just picking up steam.

Watterson, for one, had little patience for the idea that these developments meant America was divided by class. “We are all working men, the banker, the merchant, the doctor, the toiler, toiling day after day,” he argued. “The poorest babe who steals timidly into the world by the back door has as much of a chance of becoming the president of the United States as the richest who takes his millionaire grandfather by the whiskers.”

[image error]Henry Watterson in 1891. Library of Congress.

The Kentuckian blamed discontent on a national obsession with money and wealth. ” ‘Put money in thy purse’ seems to have become a national motto,” he said. He dismissed the Agrarian radicalism personified by Weaver and equated it with anarchy. “There is at this time no one political issue separating the people on the right and left into party lines, which are a source of lasting danger to the state.”

Conwell offered a different perspective on class conflict. It was not lust for money, as Watterson argued, but a desire for fraternity that animated workers, Conwell said. “The workingman wants to be equal to the king; he wishes to be the equal of the prince; wishes to be the equal of the capitalist,” he declared.

The man of the cloth then argued that the church — broadly defined — was best equipped to serve the political needs of workers. The major parties were only after votes, he said, while the church would promote fraternity among all classes and look after the material and spiritual needs of the downtrodden. “None but the working Christian Church, if I understand it, has always been and is still peculiarly reaching down the willing hand after the poor and after the lowly, to encourage the discouraged, to lift up the fallen, and to give to every man, if possible, equal opportunity with his brother,” Conwell asserted.

When his turn came, Weaver, a tee-total Methodist, took the question of religion in politics in a different direction. “The Church should be an organized army seeking to establish God’s kingdom on this earth by every legitimate means, of which legislation is one of the most today in civilized countries.” Not surprisingly, Weaver believed the program of the People’s party – government control of the railroads, free silver to reduce the tight monetary policy of the gold standard — would move the nation in that direction.

[image error]James B. Weaver from “A Call to Action,” his Populist manifesto, published in 1892.

But more would be needed. Weaver warned that the “government has been usurped and literally given over to the corporations.” The Republican party was responsible for the distress faced by many Americans “and the Democratic party is accessory after the fact to all of it.” The People’s Party led by Weaver was best equipped to take on the challenges that the other two parties wouldn’t or couldn’t.

“You know you cannot settle these great questions with these organizations,” Weaver said. “The new party is despised, as the Nazarene was despised, but I will tell you, and I use the word reverently, all hell cannot prevail against us.”

All this talk about religion in politics was too much for Woodford, the Republican representative in the debate. “I simply suggest to you that the Church is not a practical method for politically helping the workingmen, because an honest Churchman must follow in politics his conscience, wherever that conscience leads.”

[image error]James B. Weaver and his People’s Party running mate, J.G. Fields. Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

Woodford’s conscience directed him at an early age to the party of Lincoln – in fact, he said he cast his first vote for the presidential candidate nominated by the party before Lincoln, John C. Fremont. In defending his party, Woodford defended the ideology of self-improvement – what Lincoln himself called “the right to rise.”

“We believe that on this land and under this flag every man should be given the fairest chance to earn his living and to care for family and children,” Woodford said. A bit later, he took a swipe at Watterson and Weaver when he explained Republican views on money.

“Do you know the Republican idea? The Republican idea is this, that if a man is industrious and don’t indulge too much in Democratic beer, or weaken his system by Populist watering, but sticks to the old thought of industry, of honesty or labor, that the average man on this soil and under this flag will hew out a result that shall be one of the credits to the honor of the government and to himself.”

In the end, as is often the case, the debate settled nothing conclusively. Americans would debate the questions it addressed for decades to some — and some remain relevant today. But as a guide to political thinking in the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, the Great Quadrangular Debate in Philadelphia is a noteworthy event in the politics of the Gilded Age.

– – –

Books by Robert B. Mitchell are available at amazon com:

[image error][image error]Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver

December 19, 2019

“Spreading our influence everywhere:” The ethics issues of the Credit Mobilier scandal

[image error]

Editor’s note: On Dec. 17, I was privileged to speak at the Council on Government Ethics Laws annual convention in Chicago about the Credit Mobilier scandal. COGEL is “a professional organization for government agencies and other organizations working in ethics, elections, freedom of information, lobbying, and campaign finance.” Many, many thanks to Steve Berlin, who helped organize the event, and Madeleine Doubek, who moderated. Below is an edited transcript of my remarks.

The Credit Mobilier scandal, academics might say, is a rich text. It is classic tale of Gilded Age politics, featuring colorful, self-serving politicians who cravenly – and usually ineptly — tried to cover up their involvement in the affair.

It reflects growing concerns about the burgeoning economic and political power of wealthy corporations – in this case, railroads. And it is a story of journalism at a time when, as historian Mark Wahlgren Summers puts it, the profession was “fresh out of the eggshell.”

Above all else, however, the Credit Mobilier scandal is a story about right and wrong in the conduct of government affairs.

[image error]

Rep. Oakes Ames, from Behind the Scenes in Washngton.

It is an honor and a delight to be talking about this chapter in American history to a room full of government ethics officers who wrestle with that dilemma every day. Credit Mobilier ranks as the most consequential scandal to come along in Washington until Teapot Dome in the early 1920s and then Watergate. It shines a harsh light on the ethical lassitude that was commonplace in the era of the telegraph and raises issues that remain all too relevant in the age of the internet.

The company known as Credit Mobilier was an unintended byproduct of the government’s commitment to construction of a transcontinental railroad. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 chartered the Union Pacific and authorized government-backed bonds and land grants for the railroad as construction proceeded.

The seemingly generous provisions of the act, however, failed to address a basic problem. Railroad investors were being asked to put their money into a railroad being built to serve markets and communities that did not yet exist. Additional provisions made the shares less attractive. Investors were barred by law from selling Union Pacific shares below the price at which they were issued. On top of everything else, investors would be held liable if the railroad went bankrupt.

Those conditions made the Union Pacific a less-than-desirable investment – and the railroad soon had trouble attracting capital.

The solution conceived by Union Pacific Vice President Thomas C. Durant (also known as “the Napoleon of Railways”) allowed investors to pay themselves by putting their money into the company building the railroad, rather than the railroad itself. Credit Mobilier overcharged for construction work and took payment in railroad securities. Unlike those who invested directly in the railroad, the company and its investors were free to sell Union Pacifi stock at the market price. Nor would Credit Mobilier investors be held liable if the railroad went bust.

Durant’s brainstorm was a huge success — and [Rep.Oakes] Ames (a railroad financier heavily invested in the Union Pacific and Credit Mobilier) had no trouble finding buyers for Credit Mobilier stock on Capitol Hill. He sold shares at their face value of $100 — $1,738 today — usually in blocks of 10. In two instances he sold thirty shares for $3,000, $52,140. These prices were a great bargain. By one estimate, the stock at this time was worth two-and-a-half times its $100 face value.

[image error]

Schuyler Colfax. Library of Congress.

Purchasers included Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the House who would become vice president during the first term of President Grant; James. A. Garfield of Ohio, the rising star of the Republican caucus; Sen. Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who succeeded Colfax as vice president; and Sen. James Patterson of New Hampshire. Rep. James Brooks, a New York Democrat, also bought shares, but from Durant instead of Ames.

Members of Congress weren’t the only ones buying Credit Mobilier shares from Ames. He sold thirty shares to Uriah Hunt Painter, a correspondent for the New York Sun and the Philadelphia Inquirer. Painter wanted more shares than Ames was able to sell and was angry, Ames recalled later, that he could not buy as much as he wanted. Nevertheless, Painter kept Ames’s activities to himself rather than share the news with his readers.

The headlong rush to buy the valuable stock occurred in spite of House rules aimed at preventing conflicts of interest. The parliamentary manual written by Thomas Jefferson in 1801 dictated that “Where the private interests of a Member are concerned in a bill or question he is to withdraw.” That proviso was subsequently memorialized in Rule 8 of the House, which barred members from voting when they had a “direct or pecuniary interest” in legislation.

Those provisions might well have given lawmakers pause as they lined up to buy Credit Mobilier shares because Washington in the years after the Civil War brimmed with legislation promoting railroad construction. Some of those bills directly challenged the business interests of the Union Pacific.

For example: A year before Ames began selling Credit Mobilier shares to his colleagues the Union Pacific suffered two significant defeats in Congress. The Central Pacific railroad – the Union Pacific’s partner-cum-rival in the transcontinental railroad project – won a significant victory when Congress authorized its extension into territory the Union Pacific expected to claim as its own. In addition, the owners of a Kansas-based railroad chartered as a feeder line for the Union Pacific won congressional approval to extend its line to Denver – an act Ames would later charge authorized a “rival parallel road” to the Union Pacific. These defeats, I believe, were uppermost in Ames’s mind as he began to sell his shares.

In spite of the profusion of railroad bills and the common knowledge that Capitol Hill was awash in railroad money, there were no mechanisms for enforcing either Jefferson’s rule about the private interests of legislators or Rule 8 of the House. There was no ethics committee. There were no requirements that lawmakers report political contributions, assets or sources of income, as there are today.

[image error]

While the House and Senate expelled members for disloyalty during the early years of the Civil War (three by the House and 14 by the Senate), this power was rarely used in cases involving individual malfeasance. In fact, two members of the House in the 1850s – Democratic Reps. Daniel Sickles of New York and Philemon T. Herbert of California – remained on the job while they were being tried for murder (both, by the way, were acquitted – Herbert because he was ineptly prosecuted and Sickles because he used what was then the novel legal defense of temporary insanity).

Congressional ethics, then, were almost entirely a matter of personal probity. An incident related to Credit Mobilier and the Union Pacific highlights the inadequacy of this safeguard.

In the winter of 1867, Rep. Henry Dawes of Massachusetts proposed that the Union Pacific charter be amended to allow the railroad to move its headquarters out of New York. Ames and Durant had just ended a bitter feud for control of the railroad in which Durant’s proximity to New York judges and Wall Street allies gave him an advantage.

The otherwise routine piece of legislation was larded with conflicts of interest related to Credit Mobilier.

For example:

Dawes had been talking with Ames that month about buying Credit Mobilier shares and subsequently purchased 10 at $100 apiece – a fact that would not be confirmed until 1873.

James Brooks of New York protested that a “private quarrel” was the underlying reason for the Dawes proposal. Brooks would know: That month he bought 100 shares of Credit Mobilier stock from Durant, Ames’s corporate rival – another transaction that would not be revealed until 1873.

When Brooks protested that he was “totally uninterested in this matter” (an obvious lie in view of subsequent disclosures) Rep. James A. Garfield demanded that the clerk read the House rule barring members from voting on matters in which they held a personal stake. A few weeks later, Garfield himself would take 10 shares of Credit Mobilier on very favorable terms from Ames.

Clearly, personal honor was a weak reed on which to rest the ethical standards of Congress. That would become even clearer as three congressional committees formed in the aftermath of the Sun’s scoop examined Credit Mobilier’s reach into the halls of Congress.

[image error]

Rep. James Brooks, D-N.Y. Library of Congress.

When the House voted in December, 1872 to form a special committee to investigate Credit Mobilier, Ames was one of its first witnesses – and the only one who, in the words of the New York Tribune, “remorselessly told the truth” about his actions and motivations. Testifying in closed session – the hearings would be opened to the press and public one month later – Ames admitted that he was looking to cultivate influence through the sale of Credit Mobilier stock.

He saw nothing wrong with what he was doing and drew a revealing – if fallacious – distinction between his actions and bribery. “If you want to bribe a man,” he told the committee, “you want to bribe the one who is opposed to you, and not to bribe one who is your friend.” And he freely admitted to the committee that his motivation for selling the stock was exactly as he described it to McComb.

“I strove to use them,” he told lawmakers, referring to the shares, “in a way that I thought most advantageous in spreading our influence everywhere.” He never backed away from this position.

Ames’s admitted interest cultivating the railroad’s “friends” reflected a fundamental tenet of Gilded Age politics, according to historian Richard White. In his majestic study of the period, The Republic for Which It Stands, White observes that “friendship” was the governing ethos of Gilded Age politics. “Friendship was the preferred way of phrasing connections between businessmen and politicians,” according to White. “To be a friend, it was not necessary to actually like someone; bonds of obligations and reciprocity were sufficient.”

In immediate the aftermath of the Sun’s blockbuster (published Sept. 4, 1872 it broke open the story of the scandal), one lawmaker after another denied buying Credit Mobilier shares from Ames. But when the House committee led by Rep. Luke Potter Poland of Vermont began its inquiry, a different tale began to emerge.

[image error]

Rep. Luke Potter Poland, R-Vt. Library of Congress.

Many who had initially denied buying stock from Ames admitted that they had, in fact, done so – although a number insisted that they quickly returned the shares. Others said they agreed to purchase the shares but that the deal was never finalized. Many – most notably Garfield – said they would have had nothing to do with Credit Mobilier if they had known more about what it was and how it worked.

But one lawmaker – Rep. Glenni Scofield of Pennsylvania – admitted it might not have made a difference to him. He told the Poland committee: “‘Avoid the appearance of evil,’ is an injunction that, I think, sometimes rogues are more careful to observe than honest men,’”

A common argument during the hearings was that there would have been nothing wrong with buying Credit Mobilier shares. Interestingly, this position was most often taken by officials who denied actually buying the stock but were later found to have done so.

The garrulous William F. Kelley of Pennsylvania, whose earnest advocacy of iron and steel tariffs earned him the nickname “Pig Iron,” claimed he never actually consummated a deal with Ames but asserted he would have been within his rights to do so. “I cannot see that any member of Congress was precluded from making a purchase of that stock more than he would be from buying a flock of sheep, the value of which could be affected by a change of the tariff on wool or woolen goods.” Poland’s committee later concluded that Kelley had, in fact, bought 10 shares from Ames.

Not everyone subscribed to the cynical views advanced by Kelley and Scofield. Sen. James A. Bayard of Delaware turned down a chance to buy Credit Mobilier shares because “I could not consistently with my views of duty vote upon a question in which I had a pecuniary interest.”

In other words, stripped of its Victorian legalese, Bayard smelled a rat.

As the House began its investigation of the scandal, Ames testified that he had sold shares to most of those named by the Sun. His explosive testimony, delivered behind closed doors, might not have been too embarrassing for those involved had it stayed confidential.

But the decision to probe the scandal in secret outraged the public and newspaper editors across the country. In the face of withering criticism of the closed-door hearings, the House opened them to the press and public in early January, 1873, and released transcripts of the closed-door proceedings.

As one lawmaker after another appeared before the committee to put as much distance as possible between themselves and Credit Mobilier, the King of Spades watched with rising anger.

Ames wasn’t the only one who was infuriated. His rival, Durant, spoke for Ames and many others associated with the Union Pacific when he argued that there would have been no scandal at all if lawmakers had simply told the truth from the outset. “But they winced, made up pitiful martyr mouths, prevaricated, and tried to wriggle out of it,” Durant told the Sun. “Now they are wriggling back and trying to explain last summer’s explanations. Their great error was in making any effort to conceal this matter. There was nothing to conceal.”

That view, it must be said, was not widely shared.

Ames returned to the Poland committee to document his transactions with his colleagues. One member of Congress, Sen. James Patterson of New Hampshire, was forced to concede – in spite of vigorous denials made only weeks earlier – that he had in fact bought shares from the King of Spades. As he did so, the Sun noted, the former schoolteacher nervously fidgeted “like one of the poor delinquents he used to torture in the classroom.”

Colfax attempted to deny that he received a $1,200 dividend payment from Ames – the equivalent of $21,736 today – but did such a poor job that the National Republican newspaper observed that he appeared willing to say or do anything “to clear his skirts of the disgrace that sticks to them.”

Garfield was outraged by Ames’s testimony. “He is evidently determined to drag down as many men with him as possible,” Garfield wrote in his diary. “He seems to me as bad a man as can well be.”

Ames’s sensational evidence raised the stakes for everyone involved and appeared to throw into doubt the counsel Garfield had received confidentially in the early days of the scandal from Jeremiah S. Black.

[image error]

Jeremiah S. Black. Library of Congress.

The high-powered Democratic attorney was representing Credit Mobilier investor Henry S. McComb in the lawsuit that led to the Credit Mobilier disclosures. He was also Garfield’s friend and co-counsel in the famous Supreme Court case Ex-Parte Milligan, which established the supremacy of civilian courts over military tribunals.

After the Sun broke the story Black assured Garfield he had nothing to worry about as long as he argued he had no idea what Credit Mobilier did or that it had an interest in any legislation before Congress. Such claims, Black counseled, would enable Garfield to argue that he was not a party to Ames’s scheme “but the victim of his deception.”

In the end, Garfield’s anxieties were unfounded. Black’s advice foreshadowed the much-anticipated conclusions of Poland’s investigating committee, which recommended the expulsion of Ames and Brooks but no action against anyone who bought Credit Mobilier shares. That recommendation infuriated many in the press and public who wanted at least some kind of sanction against everyone implicated. But the House was in no mood to crack down.

If Credit Mobilier purchasers were not guilty of receiving a bribe, some asked, how could Ames be guilty of making one? A single person cannot commit bribery, Rep. John Franklin Farnsworth of Illinois said, “any more than one person can commit a conspiracy, or more than any one person can commit matrimony.” In the end, the House voted to censure Ames and Brooks but took no action against anyone else. A Senate committee recommended the expulsion of Patterson, but the matter never came up for a vote.

Few outside Washington were pleased by the result. Poland warned of what was at stake as the House deliberated on how to sanction those involved. The hearings highlighted the malevolent influence of corporate interests – Poland called them “associations” – that could suborn the legislative process by dispensing vast quantities of boodle. “The people are fast learning that when necessary to secure aims and interests of their own these associations can lay temptations in the way of their public servants too strong for them to resist, and that, unless some check be found, their rights, if not their liberties, will soon be at the mercy of these great and fast-increasing monopolies.”

Poland proved a better prophet than inquisitor. While his committee produced a flawed report and recommendation, he foresaw what would become one of the defining questions of the Gilded Age – the challenge of keeping monopolies from corrupting the legislative process.

Journalist Henry Demarest Lloyd elaborated on the same concerns raised by Poland when he was writing about Standard Oil several years later. “When monopolies succeed, the people fail; when a rich criminal escapes justice, the people are punished; when a legislature is bribed, the people are cheated.”

Those warnings from Poland and Demarest remain timely and relevant. The Credit Mobilier scandal opened decades of debate about political corruption and monopoly power in government. The scandal that shook Washington less than ten years after the end of the Civil War reverberates to this day.

Congress and the King of Frauds is available at amazon.com

[image error]

December 18, 2019

The Sun and Santa Claus

Over the past several years readers of this blog have become well-acquainted with the New York Sun.

Its hyper-partisan approach to news, sensational investigations (most particularly about the Credit Mobilier scandal), and colorful editor, Charles A. Dana, make it one of the most important sources for understanding the politics of the Gilded Age. It epitomizes the rough-and-tumble newspapers of the last half of the nineteenth century.

So it is a source of some wonder that the Sun is also responsible for one of the most enduring – and endearing – pieces of sentimental Christmas holiday prose: Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus.

The Newseum has a wonderful post about its back story and its author, Francis Pharcellus Church, that includes the text of this masterpiece.

Happy Holidays!

December 5, 2019

“A contumacious witness”

Joseph B. Stewart wanted his inquisitors to understand something.

He was not a lobbyist.

Sure, he may have been hired by Thomas C. Durant in 1864 as Durant campaigned for Congress to amend the Pacific Railroad Act to aid the struggling Union Pacific.

Of course he was well compensated for his work. Durant, the vice president of the Union Pacific, paid him $30,000 (the equivalent of $491,743.95 in today’s dollars according to this inflation calculator), he admitted.

And, yes, Durant provided him with $250,000 in bonds to disburse as needed Capitol Hill to smooth over disagreements — Stewart called them “disputes and demands” — and ease passage of the measures sought by the tycoon known as the “Napoleon of Railways.”

But he was definitely not a lobbyist. “I disclaim the performance of that service,” he declared.

[image error]

The Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1873. Library of Congress.

Stewart was testifying before an investigative committee led by Rep. Jeremiah Wilson, R-Ind., empaneled by the House in early January after Congress returned to Washington following the Christmas holidays. The committee was charged with investigating the “character and purpose” of Credit Mobilier, the lucrative construction arm of the Union Pacific that was suddenly at the center of an enormous scandal on Capitol Hill.

While Stewart was willing provide the committee with general details of his activities on Durant’s behalf — and more than eager to make sure no one regarded him as a lobbyist — he refused to tell Wilson and his colleagues what they really wanted to know: Who, exactly, was on the receiving end of his munificence?

Stewart argued that the confidentiality of those transactions was protected by attorney-client privilege.

“No part of that fund was paid, directly or indirectly, to a member of Congress or Senator,” Stewart told Wilson’s committee. “When you go outside of that, I claim to have duties to observe and obligations to perform as well as you, and they cannot be disregarded.”

In other words: Good luck learning anything more from me.

[image error]

Officers of the Union Pacific Railroad, 1886, with Thomas C. Durant possibly third from right. Library of Congress.

Stewart’s obstinacy on the question of who was paid as Congress deliberated on amendments to the Pacific Railroad Act set in motion one of the lesser-known but most intriguing dramas of the Credit Mobilier affair.

The investigation into the scandalous allegations detailed by the New York Sun had begun in early December behind closed doors, but because it was conducted in secret it only managed to inflame suspicions about the Union Pacific, Credit Mobilier, and the House.

[image error]

New York Herald, Jan. 30, 1873. Library of Congress.

When lawmakers came back to Washington after the Christmas holiday, they were in no mood to tolerate closed-door inquiries or stonewalling witnesses. They opened to the public the investigation led by Rep. Luke Potter Poland, R-Vt., and created the second committee led by Wilson to get to the bottom of Credit Mobilier’s business practices and dealings on Capitol Hill.

When it became clear Wilson wasn’t going to get what he wanted from Stewart, he let the matter go temporarily. But when Stewart remained intransigent when he returned to the committee more than a week later. “I refuse to speak about the business of my clients,” he said.

Wilson and his colleagues referred the stalemate to the House – and Washington settled in for the spectacle.

Stewart seemed perfectly cast for the role. At least six-and-a-half feet tall (the Chicago Tribune put him at close to 7 feet) “with an immense frame and erect carriage,” Stewart was about 50 years old, the Tribune reported. “Taken altogether, he is a very noticeable character.” As for how to describe his activities on Capitol Hill, the newspaper dismissed Stewart’s protestations. He was a “lawyer of some prominence, and a lobbyist of skill and daring.”

The day after refusing to disclose to whom he gave the bonds, Stewart appeared before the House to make his case. “A contumacious witness case always brings a crowd to the Capitol, and there was an unusual attendance today, of all classes, and the galleries were closely packed,” the Tribune observed. A group of distinguished visitors that included former New York governor Horatio Seymour and Gen. Ambrose Burnside looked on from the rear of the House.

Stewart came ready. He prepared a written speech and studied the legal precedents, according to the Tribune. The heart of his argument was that he was being persecuted simply because he insisted on respecting the trust of his clients. For that, “I am now arraigned and put into the attitude of a criminal,” he said.

“His voice was excellent,” The Tribune reported, “and, except for the fact that he appeared to have but one joint in his body, that being at the hips, his manner of delivery was good.”

Stewart earned some applause from the gallery, but the House displayed little patience with him. At one point, Rep. Henry W. Slocum, D-N.Y., asked with obvious exasperation: “I would inquire how long this thing is to continue. Is there no limit to it?”

Stewart’s high-sounding appeals to the rights and privileges of American citizens “evidently aroused the ire of many members,” the Washington Evening Star reported. On the House floor, according to the Star, the view was “pretty general” that he was “abusing the privilege granted him of purging himself of contempt by lecturing the House as to its duties.”

But that may not have mattered to the wily lobbyist. As the Tribune put it:

His speech was not intended for the House, but for the steamship interest, the Senatorial election interest, the railroad interest, the Postal telegraph interest, the land grant interest, and all others who have business to do and money to spend to procure legislation for the benefit of corporations. He wanted to show the managers of these enterprises that he could be trusted with money, and would not reveal the purposes for which he applied it.

When Stewart was through, the only question lawmakers were willing to consider was where he would be confined. A proposal to send him to the D.C. Jail failed but earned 56 votes. In the end, the House voted to confine him to the Capitol until Congress adjourned.

That night, as Stewart waited to begin his sentence, the lobbyist was praised for his stubbornness. “Stewart is floundering about one of the principal hotels tonight, receiving the congratulations of men, who tell him if he had answered the questions it would have a tendency to destroy the business of Congress,” the Tribune reported.

Available at amazon.com:

[image error]

November 26, 2019

A Call to Action

A tiresome rite of the presidential campaign is the release by candidates of tomes intended to enlighten voters about their lives, their views, and their qualifications to hold the highest office in the land. Most such literary efforts quickly find a well-deserved place on the remainder shelf at the local Costco – and none of them begin quite like this:

The author’s object in publishing this book is to call attention to some of the more serious evils which disturb the repose of American society and threaten the overthrow of free institutions.

These are the opening lines of the book written by James B. Weaver and published in the early months of 1892 as the People’s Party began to look toward the upcoming presidential campaign and consider who to nominate. Like many of its modern-day cousins, A Call to Action has languished in obscurity since its publication. As an important document of the Populist movement, it deserves a better fate.

[image error]

James B. Weaver, from A Call to Action.

A Call to Action is not light reading, but Weaver and his fellow Populists were not in a cheerful mood. “We are nearing a serious crisis,” Weaver warns in his introduction. “If the present strained relations between wealth owners and wealth producers continue much longer they will ripen into frightful disaster. This universal discontent must be quickly interpreted and its causes removed.”

The Agrarian revolt that had simmered on the nation’s farms and ranches in the decades after the Civil War reached its zenith in the early 1890s as the National Farmers Alliance and Industrial Union – or more informally, the Farmers Alliance – spread from the plains of Texas across the South and north into the Great Plains.

Their grievances were many. Farmers were being crushed by the tight money policies favored by Eastern financial interests. They wanted access to capital but found it hard to come by in rural banks far removed from the money centers of New York or Chicago. They sympathized with the demands of organized labor for better working conditions and higher pay. They feared and loathed banks. And they regarded Congress — and particularly the Senate — as hopelessly beholden to special interests.

Weaver touches on all of these themes — and more — in language that is indignant but not radical. A lifelong Methodist, the Iowan was a reformer by nature, not a revolutionary.

His formative political experiences came in the 1850s as a stump speaker and organizer for the new Republican Party. The political world in those years, the Iowan would write decades later, seemed to be “searching out a new orbit.” Weaver himself would spend much of this adult life seeking a new orbit of his own.

When war broke out, he enlisted in an Iowa infantry regiment after the fall of Fort Sumter in 1861 and fought down the Mississippi at Fort Donelson, Shiloh and Corinth. He rose through the ranks and ended his service in 1864 with the rank of colonel. He was breveted after the war as a brigadier general and remained a Republican into the 1870s.

But Weaver, an ardent temperance advocate, found that the party of Lincoln no longer shared his reformer’s zeal. Iowa Republicans rejected his bid for a congressional nomination in 1874 and one year later turned back his bid for the party’s gubernatorial nomination when party bosses engineered a convention floor stampede for Samuel L. Kirkwood.

By 1878 Weaver was a leading figure in the Greenback-Labor Party. Two years later he ran for president at the head of the Greenback-Labor ticket. He remained a temperance man, but the evils of strong drink were no longer his primary concern. Weaver became a leading supporter of the party’s namesake cause — the continued use of paper “greenback” currency to fight the deflationary pressures caused by the tight-money policies favored by financial conservatives who were represented in both parties.

[image error]

A newspaper illustration of Weaver and J.G. Fields, his running mate on the 1892 Populist ticket.

By 1892, the emphasis on greenbacks gave way to the call for the unlimited coinage of silver, but the desired end was the same. An “abundant circulating medium” is essential to a healthy economy, Weaver wrote. “We do not mean plenty of idle money, nor money which is so scare and hence so valuable that it can bring greater returns to its owner by being hoarded than by being invested. We mean money that is abroad in the channels of trade performing its legitimate office; money that works, and not money that shirks.”

Modern economists can take issue with the monetary proposals of 19th-century Agrarian radicals like Weaver. They may well have a point, but so did Weaver and his allies. Tight money exacerbated the deflationary tendencies that were impoverishing farmers and ranchers around the country.

In his discussion of monetary issues, Weaver makes a telling reference, drawing on a passage from the Apostle Paul to make his case: “that if any would not work neither shall he eat.” It was not a throwaway line — the devout Methodist filled “A Call to Action” with biblical allusions and references. When discussing abuses by railroads, Weaver paraphrases a passage from Paul’s letter to the Romans when he argues that only way to bring the railroads to heel was to have the government take them over:

It is idle to talk of any other remedy. We have experimented through the lifetime of a whole generation and have demonstrated that avarice is an untrustworthy public servant, and that greed cannot be regulated or made to work in harmony with the public welfare. Like the carnal mind, it is an enmity to the laws of God and man and is not subject to the will of either, neither indeed can be.

[image error]

Weaver in his uniform. From James B. Weaver, Fred Emory Haynes.

Weaver titles a section of the book focusing on the yawning gap between rich and poor in a section titled “Dives and Lazarus” – reference to the Biblical story of the rich man who goes to Hell while the poor man who languished at his gate goes to Heaven.

Throughout A Call to Action, Weaver urges action to stem monopolies, purge Congress of corruption (he was an early advocate of the direct election of senators) and close the gap between rich and poor to forestall violent revolution. But Weaver did not want to overthrow the American economic system – he simply wanted it work for everyone.

Several months after publication of A Call to Action, Populists gathered in Omaha to nominate a presidential candidate. Weaver won the nod – but by then his tome had been overshadowed by the party’s platform. Today, students of populism are well-acquainted with the Omaha Platform and its assertion that “the power of government—in other words, of the people—should be expanded (as in the case of the postal service) as rapidly and as far as the good sense of an intelligent people and the teachings of experience shall justify, to the end that oppression, injustice, and poverty shall eventually cease in the land.”

A Call to Action has been largely forgotten. It demands renewed attention from students of the period.

You can find my biography of James B. Weaver, Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver, at amazon.com

[image error]

Skirmisher: The Life, Times and Political Career of James B. Weaver

Amazon also carries my account of the Credit Mobilier scandal:

[image error]