Robert B. Mitchell's Blog, page 2

November 8, 2024

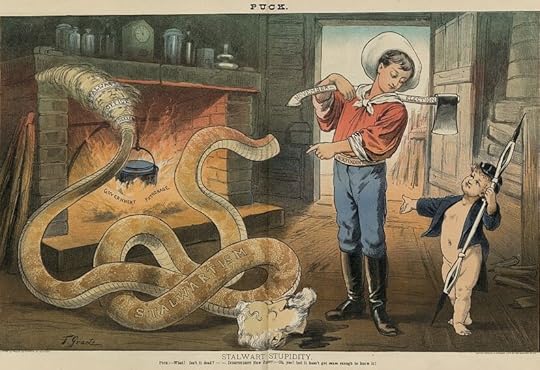

Conkling and civil service reform

An outspoken foe of slavery while he served in the House, Roscoe Conkling became preoccupied with patronage and the use of power while in the Senate.

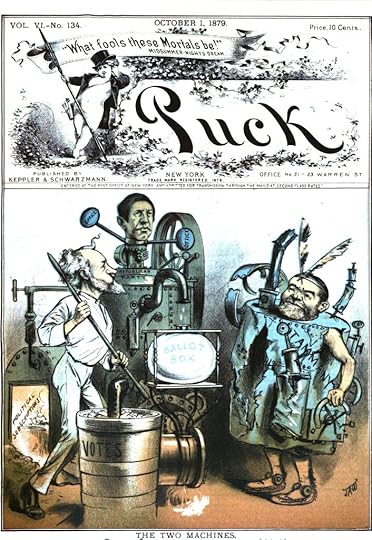

Roscoe Conkling (left) manages the smooth-running Republican machine as a Tammany Hall “brave” wearing a damaged Democratic machine looks on. The cover of Puck, Oct. 1, 1879.

Roscoe Conkling (left) manages the smooth-running Republican machine as a Tammany Hall “brave” wearing a damaged Democratic machine looks on. The cover of Puck, Oct. 1, 1879.Roscoe Conkling personified the hard-headed cynicism of the veteran politician. The Republican senator from New York sneered at reformers and ruthlessly pursued political power to advance the interests of his allies and crush enemies. Barely concealed belligerence enhanced his reputation as an arrogant and vindictive political boss. “Without malignity,” journalist George Alfred Townsend once wrote, “Conkling is nothing.”1

At the New York Republican convention in Rochester in 1877, Conkling blasted civil service reformers as canting hypocrites with one of the most memorable rhetorical broadsides of the Gilded Age:

Who are these men who, in newspapers and elsewhere, are cracking the whip over Republicans now, and playing schoolmaster to the Republican Party, and its conscience and convictions? Some of them are the man-milliners, the dilettanti and carpet-knights of politics; men whose efforts have been expended in denouncing and ridiculing and accusing honest men who, in storm and sunshine, war and peace, have clung to the Republican flag and defended it against those who tried to trail and trample it in the dust. … Some of these worthies masquerade as reformers. Their vocation and ministry is to lament the sins of other people. Their stock in trade is rancid, flat self-righteousness. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Their real object is office and plunder. When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’ 2

Conkling’s target was George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly and a champion of civil service reform whose magazine had recently begun publishing articles about women’s fashion. But Conkling’s contempt extended to all self-styled reformers, not the least of whom was the President Rutherford B. Hayes.

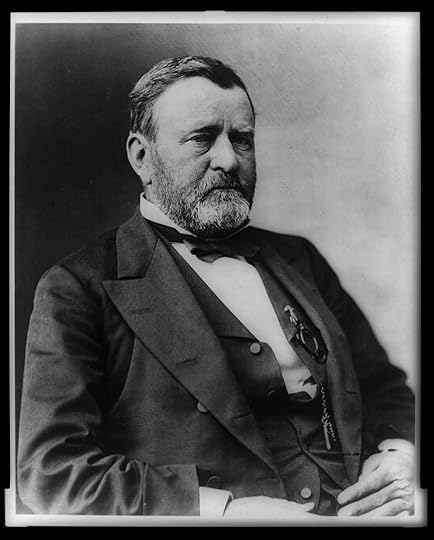

After winning the Republican presidential nomination in 1876, Hayes made it clear that he would run as a reformer rather than merely the successor to Ulysses S. Grant, whose second term came concluded with a cloud of corruption hanging overhead. At the top of Hayes’s reform agenda was civil service reform and an end to patronage in federal hiring.

Patronage, he asserted, promotes corruption, inefficiency and mismanagement. It hinders the dismissal of incompetent officials and compromises the ability of government employees to devote themselves wholly to the public good. “It ought to be abolished,” Hayes argued. “The reform should be thorough, radical and complete.”3

Sidelined by illness, Conkling — nicknamed “Lord Roscoe” by the press — did not campaign for Hayes that year. But it isn’t difficult to imagine that he wasn’t eager to hit the hustings on behalf of the Republican nominee. Hayes’s position on patronage amounted to a direct attack on the boss of the New York Republican machine.

“When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’“

— Sen. Roscoe Conkling

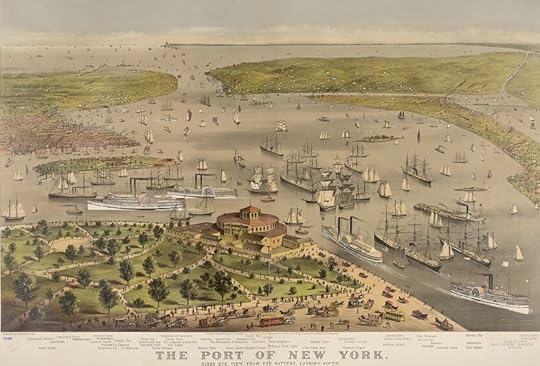

At the heart of Conkling’s power was a vast patronage empire based at the Port of New York that supplied an army of workers and a steady stream of campaign funds in the form of “assessments” drawn from workers’ pay. Control of the port put Conkling atop the New York Republican political machine and made him a target for self-styled reformers who advocated an end to patronage politics in the federal government.

Hayes made good on his vow to target patronage empires when he nominated Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the father of the future president, to run the Port of New York. Conkling summoned the support of his Republican allies in the Senate to defeat Roosevelt’s nomination. But the battle reinforced Conkling’s reputation as the embodiment of the abuses ascribed to patronage politics.

Campaign poster from 1876 for Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and vice-presidential candidate William Wheeler. Library of Congress.

Campaign poster from 1876 for Republicans Rutherford B. Hayes and vice-presidential candidate William Wheeler. Library of Congress.The Nation, the leading journal of liberal critics of Grant and his allies, made this abundantly clear in October 1877 as it reacted to Conkling’s speech in Rochester. After the war, the liberal weekly newspaper argued, the Republican Party came to be dominated by a “distinct breed of politicians possessing no real interest in legislation, with but little disposition or capacity for the management of pressing public business, and relying almost wholly for success and prominence on the use of government service in the reward of personal followers.”

Conkling was “an excellent specimen” of the spoilsmen who came to dominate the Republican Party in the years after the war, the Nation editorialized. “As a politician of power and prominence,” the Nation editorialized in 1877, “he is really a compound” of the port’s army of patronage employees. “He is made up of them, and draws his whole sustenance from them.”4

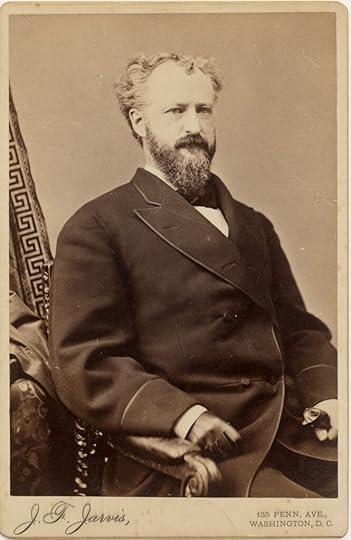

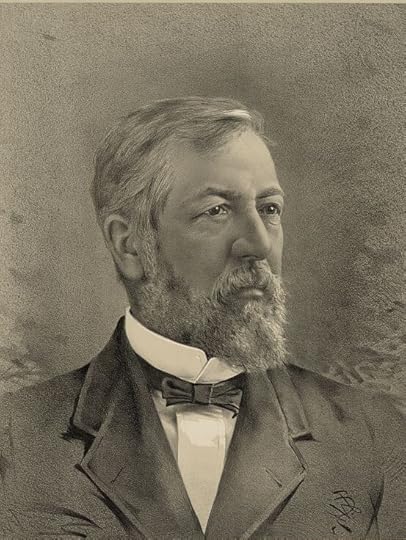

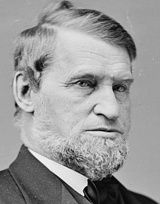

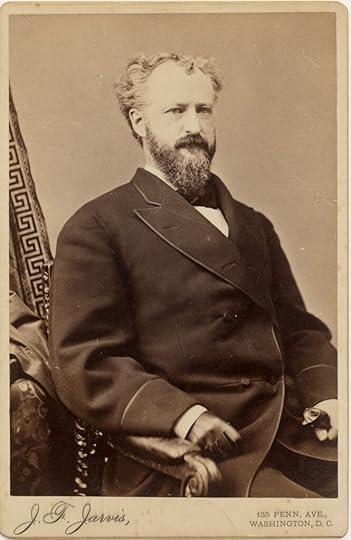

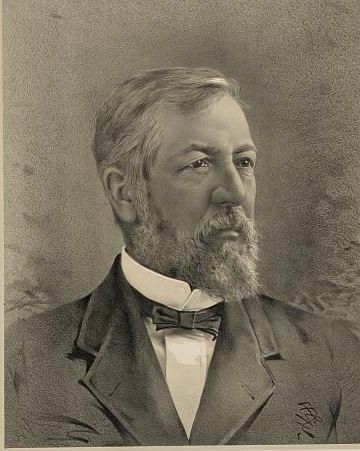

Undated photo of Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery.

Undated photo of Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery.Much of this indictment rings true. But it wasn’t always the case.

As a member of the House, Conkling allied himself with radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and belonged to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction that fashioned the Fourteenth Amendment. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Conkling passionately denounced slavery as a “barbarous and detestable crime.” After the war, as Congress debated how to reconstitute the states of the defeated Confederacy, he proved a forthright champion of enfranchising Black men as he denounced the notorious Constitutional clause allowing slave states to count enslaved people as fractional humans for purposes of congressional apportionment. “If a black man counts at all now, he counts five-fifths of a man, not three-fifths,” Conkling told the House in 1866. “Revolutions have no such fractions in their arithmetic; war and humanity join hands to blot them out.”5

In the House, he distinguished himself as one of the leading and most articulate champions of constitutionally protected Black suffrage. As a senator, it was a different story. Conkling remained a supporter of Black political and civil rights but became more preoccupied with the accumulation and use of political power while Senate radicals like Oliver Morton of Indiana and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts led the fight to reconstruct the political order in the South.

In 1870, Conkling backed Grant’s nomination of Thomas Murphy to run the Port of New York and supplanted Senator Reuben Fenton as the leader of the state Republican organization. When Sumner vocally opposed Grant’s plan to annex Santo Domingo, Conkling led the charge in the Senate against the Massachusetts Republican that led to Sumner’s ouster as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The installation of Murphy at the Port of New York and Conkling’s assault on Sumner’s Senate standing bonded Grant and Conkling. After scandal forced Murphy to resign in 1871, Conkling’s control of the port’s patronage muscle strengthened with the appointment of his ally, Chester A. Arthur. Conkling’s alliance with Grant grew stronger.

Conkling retained his loyalty to Black Southern Republicans even as he grew more preoccupied with the accumulation and uses of political power. In December 1875, when Black Republican Blanche K. Bruce was sworn in as a new senator from Mississippi, Conkling escorted Bruce to the desk of the Senate clerk to present his credentials while others in the all-white chamber ignored him.

Currier and Ives lithograph of a bird’s eye view of the Port of New York. Library of Congress.

Currier and Ives lithograph of a bird’s eye view of the Port of New York. Library of Congress.But such moments were overshadowed by the struggle for power that consumed Conkling in the years to come. Lord Roscoe fought Hayes to a draw in the battle over control of the port. Hayes eventually replaced Arthur with a Republican acceptable to all party factions. Conkling became the leader of the Republican faction known as the “Stalwarts” for their affinity to Grant and opposition to reformers.

The battle for control of the port resumed with the election of Republican James A. Garfield in 1880. Garfield found himself in the middle of the years-long rivalry between Conkling and Blaine, who pushed for the nomination of Conkling foe William Roberston to run the port.

Garfield dithered for weeks before nominating Robertson. Infuriated, Conkling resigned from the Senate and then decided to campaign for his old job. By this time, Republicans in Albany had lost patience with Conkling, who, out of office, was no longer in a position to compel their support. The shooting of Garfield on July 2, 1881, by a deranged gunman who proclaimed “I am a Stalwart” as he was led away by police, further weakened Conkling’s standing. State legislators elected a successor to Conkling on July 22, 1881, and ended his political career.

Conkling’s decision to leave the Senate over a dispute involving patronage highlighted — as nothing else could — how his priorities shifted after he left the House. He ended his political career in a struggle over what abolitionist Wendell Phillips dismissed as “the loaves and fishes of office” and sealed his reputation as a party boss rather than a statesman.6

—-

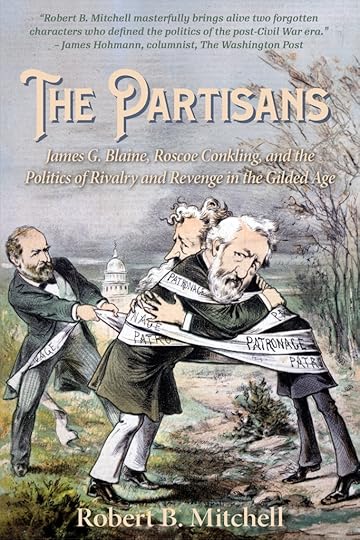

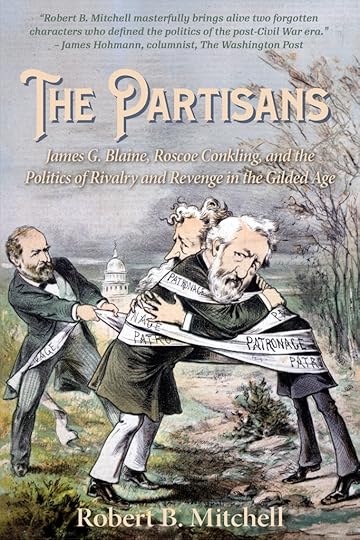

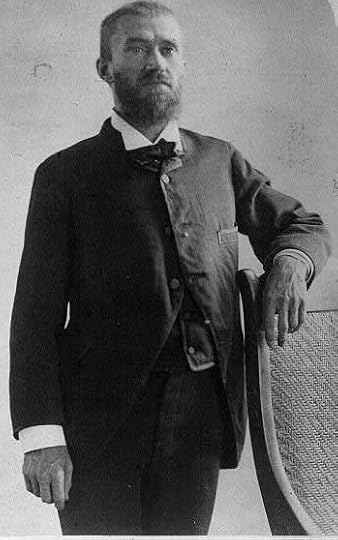

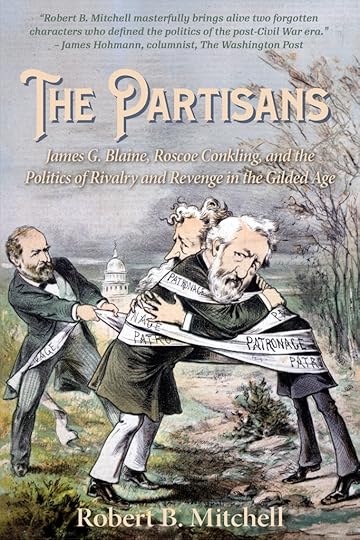

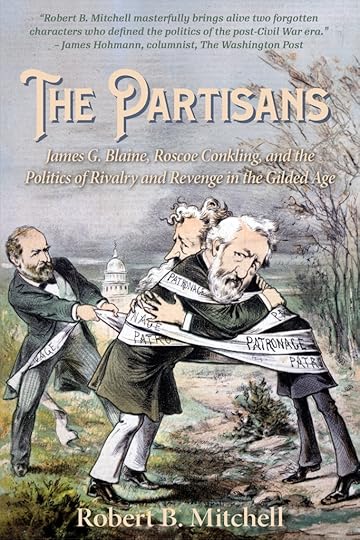

Coming next year from Edinborough Press: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age.

Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1872, p. 2.

Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1872, p. 2.  ︎New York Times, Sept. 27, 1877, p. 2.

︎New York Times, Sept. 27, 1877, p. 2.  ︎Ibid., July 10, 1876, p. 1.

︎Ibid., July 10, 1876, p. 1.  ︎The Nation, Vol. 24-25, October 4, 1877, p. 206.

︎The Nation, Vol. 24-25, October 4, 1877, p. 206.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st session, Appendix, April 17, 1860, p. 233; Ibid., 38th Congress, 2nd session, Jan. 22, 1866, p. 356.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st session, Appendix, April 17, 1860, p. 233; Ibid., 38th Congress, 2nd session, Jan. 22, 1866, p. 356.  ︎Wendell Phillips in “Ought the Negro to be Disfranchised? Ought He to Have Been Enfranchised?” North American Review, Vol. 128, No. 268, March 1879, p. 258.

︎Wendell Phillips in “Ought the Negro to be Disfranchised? Ought He to Have Been Enfranchised?” North American Review, Vol. 128, No. 268, March 1879, p. 258.  ︎

︎

October 24, 2024

“Rum, Romanism and rebellion” on Time’s Made by History platform

Rev. Samuel D. Burchard’s alliterative description of Democrats as the party of “rum, Romanism and rebellion” stands as one of the earliest — and perhaps most significant — example of the “October surprise.”

Time Magazine’s “Made By History” platform published my piece on the October surprise that helped derail James G. Blaine’s campaign for the presidency in 1884: https://time.com/7095847/october-surprise-history/

October 19, 2024

Blaine’s biographer

One of James G. Blaine’s most influential biographers was a member of his extended family and a leading Gilded Age journalist.

Family, friends, and colleagues knew her as Mary Abigail Dodge, or more simply, Abby. The public knew her as Gail Hamilton.1

Gail Hamilton. Wikimedia Commons.

Gail Hamilton. Wikimedia Commons.In an era when women were discouraged from pursuing careers outside the home, and in a profession dominated by cigar-chomping, hard-drinking men, Dodge — who adopted “Gail Hamilton” as her pen name — carved out a unique role as a Washington correspondent whose columns filled the pages of the New York Tribune and other publications.

Born in Hamilton Mass., in 1833, Dodge was a prolific author and editor who began her career in the 1850s writing for the abolitionist National Era in Washington D.C. One of her friends and colleagues was Sara Jane Lippincott, who wrote under the pen name Grace Greenwood for the New York Times. Dodge also happened to be part of the extended family of James G. Blaine. It was through this connection that she produced what is arguably the most revealing — and also the most frustrating — biography of the distinguished Republican elder statesman.2

A former House Speaker, senator, and two-time secretary of state (for James A. Garfield and Benjamin Harrison), Blaine was one of the most popular — and widely disliked — politicians of his generation. Blaine “was born to be loved or hated,” Massachusetts Republican George Frisbie Hoar wrote. “Nobody occupied a middle ground as to him.”3

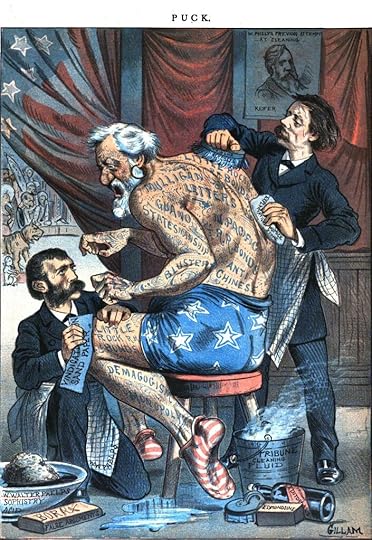

Supporters of James G. Blaine attempt to wash away the stain of scandal on the “tattooed man.” Puck, May 7, 1884.

Supporters of James G. Blaine attempt to wash away the stain of scandal on the “tattooed man.” Puck, May 7, 1884.After Blaine’s death in 1893, authors rushed out biographies of the man known to his devotees as the “Plumed Knight” and to his foes as the “tattooed man” — a reference to a Puck cartoon of Blaine covered in tattoos listing the various scandals with which he was associated. The bibliography accompanying Blaine’s entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress lists no fewer than seven biographies published between Blaine’s death in 1893 and 1934, when David Muzzey published his authoritative James G. Blaine: A Political Idol of Other Days.4 In 2023, Neil Rolde added to the Blaine canon with Continental Liar from the State of Maine.

Some of the biographies attempt to come to grips with Blaine’s controversial career. Charles Edward Russell, a turn of the century muckraker, concedes Blaine’s brilliance as a politician while going into great detail about his ethical shortcomings. Muzzey takes a more balanced approach but also grapples with Blaine’s failings.

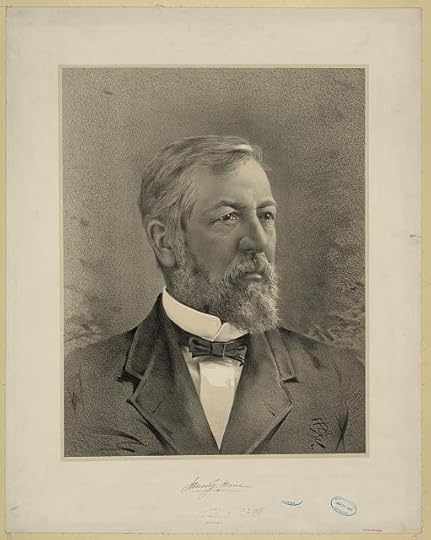

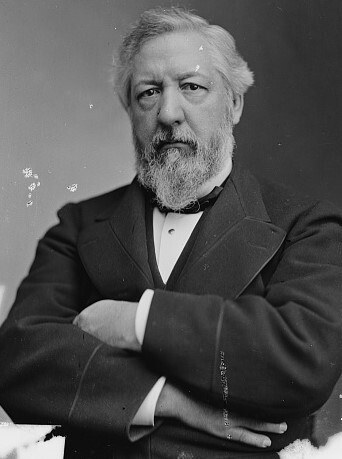

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.There is very little objectivity — and certainly none of the scathing commentary of Russell — in Dodge’s James G. Blaine, published in 1895 under the Gail Hamilton pen name. Dodge, who died in 1896, was an unabashed admirer, and her tome is a worshipful account of Blaine’s life and political career.

“Gail Hamilton was the person of all persons to write the life story of Blaine,” according to a review in the Omaha World-Herald. “She had the literary ability, political knowledge, and the necessary personal acquaintance with the great political leader to make the biography intensely interesting. She also had that unbounded admiration and enthusiasm for Blaine which places her in the closest sympathy, not only with him and his career, but with the American public, with whom Blaine holds a place of tender regard rarely equalled.”5

Parsed carefully, this assessment reveals the value and weaknesses of Dodge’s book. The “necessary personal acquaintance” included spending winters with the Blaines in Washington D.C., allowing her glimpses of personalities and events.6 She knew her subject well and, perhaps more than any other biographer, could provide insights into his character and motivations. She also had access to the prolific correspondence of Blaine and, just as importantly, his wife, Harriet Stanwood Blaine, like her husband an acute observer of events and people.

On the other hand, her “unbounded admiration” makes her a less than reliable evaluator of Blaine’s career. Her target audience were those who regarded Blaine with the same admiration as the World-Herald. Less a biographer than a hagiographer, Dodge was uncritically supportive of Blaine’s decisions and motivations. That makes for a tedious read.

Nevertheless, some passages are revelatory. As a student of the Credit Mobilier affair, I was particularly intrigued by her description of Blaine’s behind-the-scenes role as a counselor and adviser to some of the Republicans implicated in the scandal.

Oakes Ames. Library of Congress.

Oakes Ames. Library of Congress.“Mr. Blaine was indefatigable in defending and advising those who were the objects of attack,” Dodge wrote. Befuddled lawmakers, “gentle and scholarly men, in the natural timidity of their unwontedness, suffered many a pang, and the door-bell sometimes rang Mr. Blaine from his bed at midnight to counsel and console.”7

Oakes Ames, the Union Pacific railroad financier and Massachusetts Republican congressman at the center of the scandal, presented a particularly pitiful sight. One evening, Ames sat before the fireplace in Blaine’s library, “stunned into immobility,” according to Dodge, “with his head bowed on his breast,” while Blaine “applied himself indefatigably in and out of the house, arranging for [Ames’s] defense and for that of the other men who were implicated with him and were equally guiltless of bribery.”8

Dodge was not a neutral observer. Few thought then (or believe today) that the lawmakers implicated in the scandal were entirely “guiltless.” But her observations about Blaine’s behind-the-scenes efforts on their behalf and Ames’s dejected demeanor offer a revealing glimpse into what was going beyond the confines of the Capitol hearing room where the affair was being investigated.

Dodge’s biography is full of similar nuggets. Plowing through it can be tedious, but for students of the Plumed Knight, it is worth it.

****

My book on Blaine’s two-decade long battle with Roscoe Conkling — The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming soon from Edinborough Press.

Susan Coultrap-McQuin, “Gail Hamilton,” Legacy, Vol. 4 (1987), p. 53.

Susan Coultrap-McQuin, “Gail Hamilton,” Legacy, Vol. 4 (1987), p. 53.  ︎Ibid., pp. 54-55.

︎Ibid., pp. 54-55.  ︎George Frisbie Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Son,

︎George Frisbie Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years Vol. 1 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Son,1903), p. 200. Hereafter referred to as Coultrap-McQuin.

︎The Blaine bibliography lists reprint dates for Muzzey’s book.

︎The Blaine bibliography lists reprint dates for Muzzey’s book. ︎Omaha World-Herald, Aug. 19, 1895, p. 4.

︎Omaha World-Herald, Aug. 19, 1895, p. 4.  ︎Coultrap-McQuin, p. 55.

︎Coultrap-McQuin, p. 55.  ︎Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1895) pp. 285-286.

︎Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., Henry Bill Publishing Co., 1895) pp. 285-286.  ︎Ibid., p. 286.

︎Ibid., p. 286.  ︎

︎

October 2, 2024

From “sic semper tyrannis” to “I am a Stalwart”

John Wilkes Booth, Charles Guiteau, and the madness of assassination.

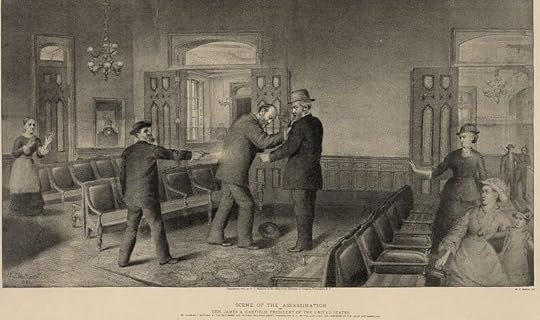

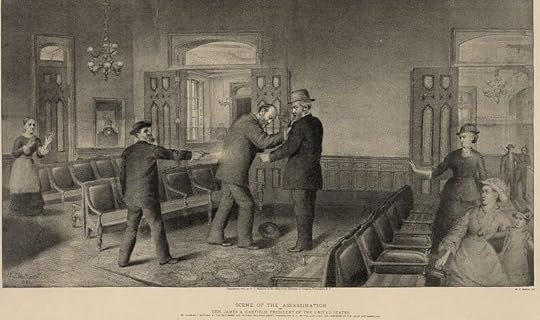

An artist’s rendering of the shooting of James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. Library of Congress.

An artist’s rendering of the shooting of James A. Garfield on July 2, 1881. Library of Congress.At first glance, the killers of Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield would seem to have little in common.

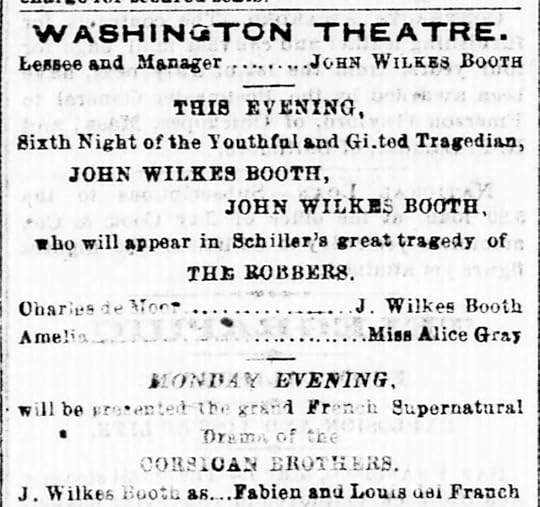

In the early 1860s, John Wilkes Booth appeared to be the latest in his family’s line of talented actors. His father was an accomplished performer, and his older brother, Edwin, was described at his death as “America’s great tragedian.” In 1862, the Chicago Tribune praised the Booth family’s contributions to American theater and foresaw great things for Edwin’s brother. John Wilkes “steps forward to claim the attention of the American public” with talent “equaling both father and brother in the delineation of Shakespearean characters,” the Tribune predicted.1

A front-page advertisement for a performance by John Wilkes Booth in the Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1863.

A front-page advertisement for a performance by John Wilkes Booth in the Washington Evening Star, May 2, 1863.Charles Guiteau, on the other hand, was a failed attorney who wrote and sold religious tracts and insurance. The Illinois native joined a New York commune that practiced free love but departed when he was restricted to menial kitchen duty. He beat his wife during their five years of marriage — only one example of his vicious temper. In New York City, he stalked a young woman he believed wrongly to be an heiress until the police told him to stop.2

Booth basked in national acclaim. Guiteau labored in well-deserved obscurity. But both saw themselves as heroes, and today they are joined in infamy for deciding it was their duty to murder a president.

Both believed they would change history. They did – but not in the ways they intended.

On April 14, 1865, less than a week after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Booth fatally shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater. Jumping onto the stage from the presidential box, he shouted “sic semper tyrannis” — the Latin motto of Virginia meaning “thus only to tyrants.” Elsewhere in the capital, an assassin working with Booth gained entrance at the home of Secretary of State William Seward — bedridden as he recovered from a recent carriage accident — and attempted to kill him. Seward and his son suffered serious stab wounds in the attack but survived.

A diehard supporter of the Confederacy, Booth had plotted to kidnap Lincoln in March 1865, apparently in the belief that such an act could turn the tide of the war in favor of the South. That plot fell through, as James L. Swanson recounts in Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer, but soon gave way to something more despicable. Instead of kidnapping Lincoln, Booth would assassinate him.3

Undated photo of John Wilkes Booth. Library of Congress.

Undated photo of John Wilkes Booth. Library of Congress.Booth hated the idea that once-enslaved Black men and women would enjoy civil and political rights in post-war America. He hoped that killing the president would somehow revive the rebellion, restore enslavement, and consign Lincoln to the dustbin of history. None of those events occurred, Swanson notes. In fact, the shooting transformed Lincoln into a national hero on a par with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other honored figures from our past.4

Above all else, Booth wanted to be a hero. But as the New York Herald reported days after the assassination, he failed in all respects.

The assassination of Lincoln and the attempt to kill Seward “continue to inform the engrossing and melancholy subject of thought, feeling, conversation and action throughout the North,” the Herald reported on April 18. “The murder of a Chief Magistrate being an unprecedented event in our history, of course the demonstration of feeling is such as never been before manifested by the people, whose affection for their martyred president, estimation of their great loss, and terrible indignation over the foul act by which his death was produced are unmistakably shown in a nation spontaneously draping itself in the solemn weeds of mourning.”5

While the murder of Lincoln originated in the fevered brain of a diehard Confederate sympathizer, Garfield’s assassination grew out of the delusions of a disappointed office-seeker as a struggle over patronage and power roiled the Republican Party.

Guiteau numbered among the thousands seeking appointment to a job in the Garfield administration. He considered himself worthy of a prestigious diplomataic appointment and pressed his claim at the White House and State Department. At at one point actually gained admission to see Garfield, handing him a copy of a speech he wrote with the words “Paris consulate” scrawled across the top.

Far more significant than Guiteau’s troubles getting a job was the battle for patronage and influence in the new administration being fought by Blaine and Senator Roscoe Conkling, the imperious boss of the New York Republican Party and Blaine’s enemy. Conkling was the titular head of a party faction known as the Stalwarts that included Garfield’s vice president, Chester A. Arthur.

After weeks of trying to propitiate the rival Republicans, Garfield nominated a Conkling foe to run the Port of New York, the patronage bastion that formed the basis of Conkling’s power in the Empire State. Blaine won the power struggle with his archrival.

An undated photo of Charles Guiteau. Library of Congress.

An undated photo of Charles Guiteau. Library of Congress.In protest, Conkling shocked the nation on May 16 when he and his fellow New York Republican Thomas C. Platt resigned from the Senate. His friends in the press hailed the resignations as a triumph of principle over politics. “There are two men in the country, at least, to whom self-respect is more important than office,” the Chicago Inter-Ocean thundered. “Senator Conkling and his colleague have exercised an undoubted privilege and taken a manly course, and have done that which few public men would dare to do in the face of an angry and powerful executive.”6

Many others were critical. “The news produced a profound sensation throughout the country,” the New York Tribune reported. The anti-Conkling Tribune noted that the “conduct of the ex-senators was sharply condemned in Washington and elsewhere.”7

Meanwhile, Guiteau was getting nowhere. He continued his pursuit of a diplomatic position but was eventually barred from the White House. An exasperated Blaine told Guiteau to stop pestering him.8

Following the battle between Blaine, Conkling and Garfield in the newspapers, Guiteau decided God wanted him to kill Garfield to save the Republican Party.

After spending weeks planning the assassination and stalking the president, he fired three bullets into Garfield at a Washington train station on July 2, 1881. Afterward, he tried to cast his murderous attack as an act of altruism. “I did it, and will go to jail for it. Arthur is president, and I am a Stalwart,” Guiteau declared as he was led away by police.9

But Guiteau’s declaration proved premature and wildly off the mark. Garfield clung to life until September 19, when he died in Elberon, N.J. By that time, the political repercussions of Guiteau’s act of madness had claimed Conkling — the leader of the Republican faction on whose behalf Guiteau claimed to be acting — as an unintended victim of the shooting. Conkling failed to win re-election to the Senate, a defeat that ended his career in politics.

Shortly after Garfield was shot, the influential Springfield Republican weighed in from western Massachusetts with a verdict that Conkling and his allies proved unable to overcome. The newspaper described Guiteau as “a miserable ne’er-do-well” who is “in sympathy with Arthur and Conkling in the struggle over the New York custom house.”10

Far from aiding Stalwarts, Guiteau saddled them with the stigma of Garfield’s assassination and accelerated their demise as a dominant force in Republican politics.

****

The assassination of Garfield figures prominently in my upcoming book, The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Coming soon from Edinborough Press.

New York Times, June 7, 1893, p. 5; Sacramento Record-Union, June 7, 1893, p. 1; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 17, 1862, p. 4.

New York Times, June 7, 1893, p. 5; Sacramento Record-Union, June 7, 1893, p. 1; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 17, 1862, p. 4.  ︎Kenneth D. Ackerman, Dark Horse: The Surprising Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), p. 135; Candice Millar, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), pp. 63-64; George W. Walling, Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (New York: Caxton Book Concern Ltd., 1887), pp. 504-505.

︎Kenneth D. Ackerman, Dark Horse: The Surprising Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2003), p. 135; Candice Millar, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), pp. 63-64; George W. Walling, Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (New York: Caxton Book Concern Ltd., 1887), pp. 504-505.  ︎James . Swanson, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killers (Boston, New York: Mariner Books, 2006), pp. 25-26.

︎James . Swanson, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killers (Boston, New York: Mariner Books, 2006), pp. 25-26.  ︎Ibid., pp. 386-387.

︎Ibid., pp. 386-387.  ︎New York Herald, April 18, 1865, p 4.

︎New York Herald, April 18, 1865, p 4.  ︎Chicago Inter-Ocean in the Washington Evening Star, May 17, 1881, p. 1.

︎Chicago Inter-Ocean in the Washington Evening Star, May 17, 1881, p. 1.  ︎New York Tribune, May 17, 1881, p. 1.

︎New York Tribune, May 17, 1881, p. 1.  ︎Ibid., p. 121.

︎Ibid., p. 121.  ︎Springfield Republican in New York Times, July 3, 1881, p. 6.

︎Springfield Republican in New York Times, July 3, 1881, p. 6.  ︎

︎

September 15, 2024

The strange history of ‘Stalwart’

Coined by James G. Blaine, applied to supporters of Roscoe Conkling, and invoked by an assassin.

The tortured political etymology of “Stalwart” originated shortly after Rutherford B. Hayes took office as the nation’s 19th president.

It was April 1877. Washington D.C. was awash in rumors that Hayes had agreed to withdraw federal support for embattled Republican governors in South Carolina and Louisiana as part of a deal with Democrats that allowed him to take office after his bitterly disputed election victory over Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York.

Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, the Republican “Plumed Knight” with a devoted following among the party faithful, warned of the rumored deal and asserted that Hayes could not be a party to it. “I know there has been a great deal said here and there, in the corridors of the Capitol and around and about, in by-places and high places as of late, that some arrangement has been made,” he warned on the Senate floor. “But I deny it on the simple, broad ground that [it] is an impossibility that the administration of President Hayes could do it.”

A month later, when it looked like that was exactly what Hayes was doing, Blaine shared his worries in a letter to the Boston Herald republished April 12 in the New York Times.

Blaine wrote that he fully supported D.H. Chamberlain, the ousted Republican governor of South Carolina. “I am equally sure” that Louisiana’s embattled Stephen Packard “feels that my heart and judgment are both with him in the contest he is still waging against great odds for the Governorship he holds by a title as valid as that which justly and lawfully seated Rutherford B. Hayes in the Presidential chair.”

Blaine continued: “I trust also that both Governors know that the Boston press no more represents the stalwart Republican feeling of New England on the pending issues than the same press did when it demanded enforcement of the Fugitive Slave law in 1851.”

A political label was born.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.The letter represented an attempt by Blaine, an astute student of public opinion, to align with rank-and-file Republicans who looked on with alarm at Hayes’s retreat from the vigorous defense of Republican-led Reconstruction state governments.

Hayes was finding all kinds of ways to alienate Republicans, including Blaine’s arch-rival, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. Conkling presided over a political machine powered in large part by the patronage bastion at the Port of New York. The port employed around 1,000 workers who owed their jobs and a portion of their paychecks to their political sponsor. President Ulysses S. Grant named allies of Conkling to run the port, giving the senator and his allies control over its vast patronage treasure house.

Hayes styled himself as a reformer who wanted to take patronage out of government hiring practices — and he made Conkling and the Port of New York his top target. The president counted some prominent Republican as allies, including George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly who had made civil service reform a personal crusade, and Carl Schurz, the one-time Liberal Republican who now served in Hayes’s Cabinet.

But none were as formidable as Conkling. Imperious, arrogant, and eloquent, the boss of the New York Republican machine would not cower before Hayes and his friends. At the 1877 New York Republican convention, “Lord Roscoe,” as he would become known, angrily proclaimed his contempt for self-styled reformers and their allies in the press, the Cabinet, and White House.

“Who are these men who in newspapers and elsewhere are cracking the whip over Republicans now and playing schoolmaster to the Republican Party and its conscience and convictions?” Conkling thundered as Curtis nervously looked on. “Their vocation and ministry is to lament the sins of other people. Their stock in trade is rancid, flat self-righteousness. They are wolves in sheep’s clothing. Their real object is office and plunder. When Dr. Johnson defined patriotism as the last refuge of a scoundrel, he was unconscious of the then undeveloped capabilities and uses of the word ‘reform.’”

A Stalwart timeline:

April 1877: Blaine uses the phrase “stalwart Republicans” in a letter describing rank-and-file Republican opponents of President Hayes.September 1877: Conkling delivers an angry, eloquent denunciation of civil service reformers at the New York Republican convention in Rochester that makes him the unofficial leader of the stalwart Republicans described by Blaine.1880: “Stalwart” becomes a noun to describe the rank-and-file Republicans loyal to Conkling and other party bosses.July 2, 1881: Assassin Charles Guiteau proclaims “I am a Stalwart” after shooting President James A. Garfield at a Washington train station. Garfield dies of his wound Sept. 19, 1881,Nov. 14, 1881: Blaine testifies at Guiteau’s trial that he “invented” the use of the phrase “stalwart” Republican.Conkling’s furious denunciation of civil service reformers touched a chord with rank-and-file Republicans (not to mention party bosses in other states) and made him — rather than Blaine — the leader of what became known as the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party. By 1880, Blaine carried the banner for a rival faction of Republicans who were less committed to Reconstruction and not as opposed to civil service reform as the Stalwarts. They were known as the Half Breeds.

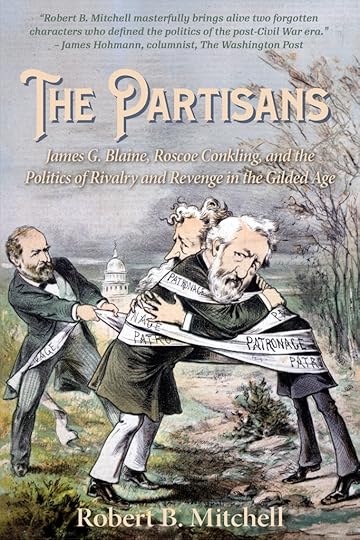

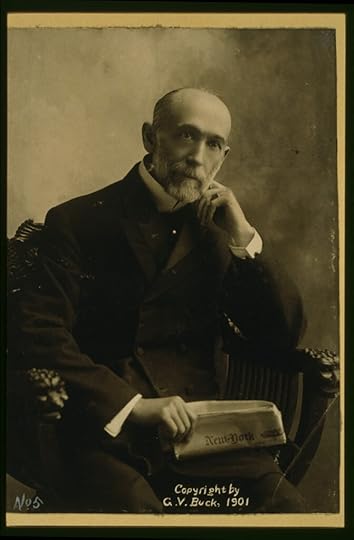

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.

Roscoe Conkling. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.The feud between Stalwarts and Half Breeds tied the 1880 Republican convention in knots. Stalwarts led by Conkling favored the nomination of Ulysses S. Grant for an unprecedented third term as president. Blaine led the Half Breeds in opposition to Grant and Conkling. It took 36 ballots at the convention in Chicago before Republicans settled on a dark-horse alternative to Blaine or Grant — James A. Garfield of Ohio. To placate New York Stalwarts, Garfield selected Chester A. Arthur, a Conkling ally and former chief of the Port of New York, as his vice-presidential running mate.

Garfield defeated Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock in the fall, but the Stalwart-Half Breed feud persisted. Blaine, Garfield’s secretary of state, cautioned Garfield against giving too much away to Conkling’s Stalwart allies. Conkling wanted his man to run the Port of New York. After weeks of back-and-forth negotiations, Garfield astounded Washington and infuriated Stalwarts by nominating Conkling foe William Robertson to run the port. Conkling and protege Thomas Platt of New York promptly resigned from the Senate, returned to New York, and began campaigning for the state legislature to send them back to Washington.

The feud between Half Breeds and Stalwarts filled the front pages and editorial columns of newspapers. A delusional office-seeker named Charles Guiteau closely followed the drama. As he pursued a longshot campaign for a diplomatic posting, Guiteau became obsessed with the feud and fearful of Blaine’s influence over Garfield. He decided to kill Garfield after concluding that he was the reason he wasn’t getting the diplomatic job he wanted. On July 2, 1881, Guiteau shot Garfield at a Washington train station and then proclaimed, “Arthur is president, and I am a Stalwart.”

Garfield succumbed to his wounds less than three months later. Conkling and Platt failed in their bid to return to Washington. Arthur, now president, surprised Conkling by refusing to remove Robertson at the Port of New York. Guiteau went on trial for the assassination of Garfield on Nov. 14, 1881.

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.

Drawing of the July 2, 1881 shooting of President Garfield (center) by Charles Guiteau (left). Blaine is seen standing next to Garfield. Library of Congress.Blaine was the first witness. Under cross-examination by Guiteau’s attorneys, he reprised the battle between Stalwarts and Half Breeds. Blaine was clearly in no mood to dwell on the political feud, and when the topic of the word “Stalwart” came up, he grew irritable. “If counsel is wishing a chapter of political history to form part of the testimony, it ought to be a correct one,” Blaine snapped. “Stalwart” had been in use as a political label long before the Chicago convention, he told the court, “and I invented it myself.”

************

I am finishing a book about the feud between Blaine and Conkling titled The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Other books now available at amazon.com:

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

August 27, 2024

“First Victory — Then Defeat!”

The Union defeat at the first battle of Manassas set in motion the full-scale war effort that changed America.

A cannon on the battlefield at Manassas Battlefield National Park. Photo by Robert B. Mitchell.

A cannon on the battlefield at Manassas Battlefield National Park. Photo by Robert B. Mitchell.MANASSAS, Va. — The quiet of a muggy August morning belies the tumult that unfolded on this battlefield more than 160 years ago.

A handful of tourists and dog walkers stroll across the fields where Union and Confederate forces collided on July 21, 1861. On that day, Union forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell confronted rebel troops led by Maj. Gen. G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, a strategically significant railroad junction in western Prince William County, Va., in what was the first major battle of the Civil War.

No less than Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, Antietam, or indeed any number of Civil War battlefields, Manassas is a somber place — especially since it is the site of two significant battles, the second coming in 1862 and resulting in another Confederate victory.

Cannons and monuments abound, offering silent testimony to the courage, chaos, sacrifice and stampede that marked that fateful day in 1861. Few if any realized at the time that the battle foretold years of unimaginable carnage and — in ways totally unforeseen — immense change in American society that followed the Southern surrender at Appomattox almost four years later.

In the spring and summer of 1861, Union and Confederate forces positioned themselves in Washington and Northern Virginia. McDowell commanded the Union troops gathered in and around the nation’s capital while Beauregard led the Confederates massed near Manassas Junction.

Clamor for a quick and decisive strike against the rebels had been building in Washington since the fall of Fort Sumter in April. As spring gave way to summer, calls for action grew louder. Reporting that the decision had been made to take the fight to the rebels, the New York Tribune cheered what it expected would be a triumphant Union victory.

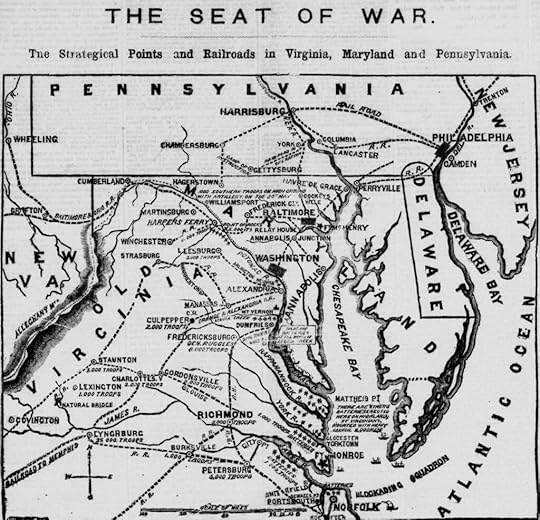

The New York Herald map from May 27, 1861, lays out the disposition of Union and Confederate forces in Virginia.

The New York Herald map from May 27, 1861, lays out the disposition of Union and Confederate forces in Virginia.“We congratulate the country,” a Tribune report from Washington proclaimed, that “the power of the government is about to be felt. Thousands of hearts, long despondent with sad forebodings of evil, in innumerable things, are about to be changed to joy unspeakable by the bugles of the charge. ‘Forward to Richmond! We seize the cry of the old crusader and shout with exultant voices, ‘God wills it! God wills it!'”

A sub-head on the Tribune story summed up the prevailing hubris: “On, to Richmond.”1

Northern politicians and newspapers like the Tribune expected that the rebel forces would be routed and secession crushed. It didn’t turn out that way.

The story of the battle is well known. Headquartered in Arlington on the estate of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, McDowell’s force of 30,000 began its march toward Manassas Junction on July 16. A journey that today takes less than an hour (if traffic cooperates) took four days as Union forces encountered fallen trees and other obstacles left by retreating Confederates. Meanwhile, rebel forces numbering about 25,000 under Beauregard waited at Manassas Junction.2

Well before dawn on July 21, McDowell went on the attack and outflanked the surprised Confederates. Rebels retreated until the Union advance halted in the face of withering artillery from troops led by Gen. Thomas L. Jackson — later known as “Stonewall” Jackson for his stand against the advancing U.S. forces. The Union delay gave Confederates the time to reorganize and launch a counterattack.

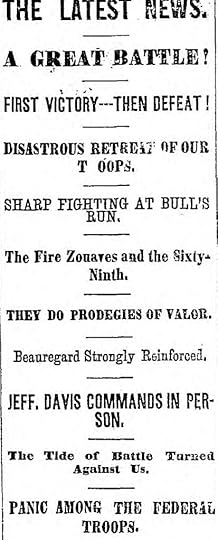

The Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861.

The Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861.Confederates benefited from the arrival of reinforcements under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston from the Shenandoah Valley. Union General Robert Patterson, a veteran of the War of 1812, was supposed to keep Johnston bottled up but failed to do so. Confused by unclear instructions from Washington, Patterson retreated to Harper’s Ferry. With the way open, Johnston’s troops departed from Winchester and arrived via railroad to reinforce Beauregard’s forces.3

Stalled before the strengthened rebel defenses, exhausted and disorganized Union troops withdrew and then retreated in panic as Confederates advanced. Picnicking Washingtonians who traveled to the scene of the battle hoping to see a stirring martial spectacle found themselves caught up in the frenzied retreat.

The confusion on the battlefield was reflected in the headlines that appeared over the next several days in the Northern press. Early reports hailed a great Union victory. The next day, the picture became clearer. “FIRST VICTORY — THEN DEFEAT!” shouted the page 1 headline in the Chicago Tribune. Sub-heads elaborated on the sobering details. “The Tide of Battle Turned Against Us,” and “Panic Among the Federal Troops.”4

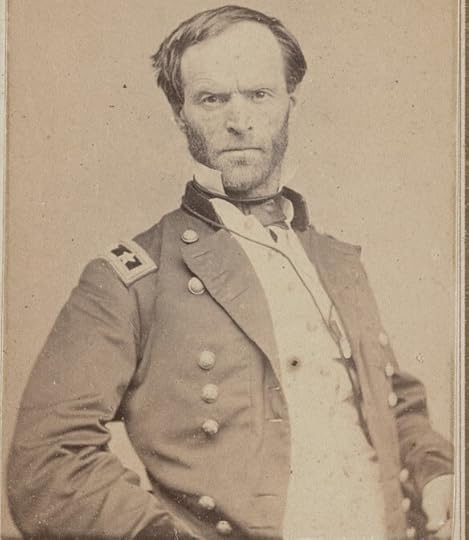

William Tecumseh Sherman, then a colonel commanding a New York brigade in the battle, wrote in his memoirs that the Union defeat exposed the inexperience, complacency, disorganization, and hubris of the Northern army.

“Our men had been told so often at home that all they had to do was make a bold appearance, and the rebels would run,” Sherman recalled. Almost “all of us for the first time then heard of cannon and muskets in anger, and saw the bloody scenes common to all battles, with which we were soon to be familiar. We had good organization, good men, but no real cohesion, no real discipline, no respect for authority, no real knowledge of war.”

While the Union defeat humiliated the North, the battle also revealed that the Confederates were too disorganized to pursue their fleeing enemy. The rebels “really had not much to boast of,” according to Sherman, “for in three or four hours of fighting their organization was so broken up that they did not and could not follow our army, when it was known to be in a state of disgraceful and causeless flight.”5

Both sides learned lessons that shaped the rest of the war. Congress approved legislation to enlist 1 million men for a period of three years. President Abraham Lincoln called in General George McClellan from the west to take command of the new troops who would be organized into the Army of the Potomac. McClellan melded this martial multitude into a powerful fighting force that he would prove strangely reluctant to use but which under the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant eventually crushed the rebellion after years of hard and bloody fighting. Reveling in their victory at Manassas, Confederate troops gained a confidence in their fighting ability that fortified them in the years ahead.6

William Tecumseh Sherman. Library of Congress.

William Tecumseh Sherman. Library of Congress.In Washington, the aftermath of the Union defeat produced a profound change in policy. During the opening months of the war, many in the North wanted to prosecute the war simply to restore the Union without disturbing slavery where it existed. After Manassas, Congress took the first, tentative steps toward abolition by passing legislation allowing Union forces to free enslaved men and women who were being used to aid the Confederate war effort.

After the defeat at Manassas, the North learned “that if the National Government did not interfere with slavery, slavery would interfere with the National Government,” James G. Blaine wrote in the first volume of his Twenty Years of Congress. The reluctance to confront enslavement began to give way to the realization that it was a central pillar of rebellion and secession.

“The virtue of this legislation,” Blaine argued, “consisted mainly in the fact that it exhibited a willingness on the part of Congress to strike very hard blows and to trample the institution of slavery whenever or wherever it should be deemed advantageous to the cause of the Union to do so. From that time onward the disposition to assail slavery was rapidly developed …”7

Lincoln would issue the Emancipation Proclamation Jan. 1, 1863. The Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery passed Congress in January 1865 and was ratified before the end of the year. Slowly but surely, the war that began simply to preserve the Union would also become a war to end slavery.

The Manassas battlefield, Aug. 4, 2024. Photo by Robert Mitchell.New York Tribune June 29th, 1861, p. 4.

The Manassas battlefield, Aug. 4, 2024. Photo by Robert Mitchell.New York Tribune June 29th, 1861, p. 4.  ︎W.J. Tenney, The Military and Naval History of the Rebellion in the United States (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1866) p. 69; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 339. Hereafter referred to as McPherson; Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Co., 1961), p. 440.

︎W.J. Tenney, The Military and Naval History of the Rebellion in the United States (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1866) p. 69; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 339. Hereafter referred to as McPherson; Bruce Catton, The Coming Fury (Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Co., 1961), p. 440.  ︎McPherson, p. 339.

︎McPherson, p. 339.  ︎Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861, p. 1.

︎Chicago Tribune, July 23, 1861, p. 1.  ︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 1 (New York D. Appleton & Co., 1875, pp. 181-182. Hereafter referred to as Sherman.

︎William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Vol. 1 (New York D. Appleton & Co., 1875, pp. 181-182. Hereafter referred to as Sherman.  ︎McPherson, pp. 348-349..

︎McPherson, pp. 348-349..  ︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress, Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn.: The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1884), pp. 341-343.

︎James G. Blaine, Twenty Years of Congress, Vol. 1 (Norwich, Conn.: The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1884), pp. 341-343.  ︎

︎_____

I am the author of the forthcoming The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age (Edinborough Press).

My other books are available at amazon. com

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

Skirmisher: The Life, Times, and Political Career of James B. Weaver.

August 1, 2024

An “Old Political Reporter”

William Cadwalader “Billy” Hudson made a career out of being in the right place at the right time.

He saw James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and Chester Arthur up close. He knew — and was infatuated with — Kate Chase Sprague. When Democrats learned near the end of the 1884 presidential campaign that Blaine had stayed mum as a Protestant preacher slandered Democrats and Catholics, Hudson witnessed their glee and astonishment.

William Cadwalader “Billy” Hudson was an eyewitness to many of the most important events in the struggle for power between Blaine and Conkling that helped define the politics of the Gilded Age.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is being published this fall by Edinborough Press.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is being published this fall by Edinborough Press.Hudson worked for the Brooklyn Eagle as a reporter and editor. He prowled the corridors of Washington D.C., Albany, and New York City in search of news. Even when he wasn’t on assignment he stumbled on a big story, as happened during the 1880 Republican convention in Chicago, where Republicans nominated dark horse James A. Garfield on the 36th ballot.

In Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter, Hudson offered a rich anecdotal memoir of his years on the beat. “The purpose of the undertaking was simple,” he wrote in the preface to his book. “It was to recall people with whom, in his work as a political reporter for many years, the writer had come into close contact and events in which, in close relation to sources of direction and control, he had been an active participant.”1

In keeping with the traditions of the era, Hudson slipped easily between his role as a gatherer of news and a participant in the events of the time. Historian Mark Wahlgren Summers, in his masterful account of the 1884 campaign, called Hudson “a generally unreliable reporter” and noted that he helped Democrats by preparing and circulating campaign material for the party. Biographers of Kate Chase Sprague and Conkling, on the other hand, have deemed him credible and cite his accounts.2

Random Recollections wastes no time detailing Hudson’s newsy encounters. It opens with a chapter devoted to Kate Chase, the brilliant and alluring daughter of Lincoln’s treasury secretary, Salmon P. Chase. Hudson said he met Chase in 1868, when she was in New York as her father sought the Democratic nomination for president.

Then a young reporter, Hudson recalled, he “met Miss Chase and forthwith fell under her sway, a willing captive.” She fed him tips on the nomination battle — most of which were spiked by his editor, “but some stole by even his vigilance — enough to pay the woman for the pains she had taken.”3

Kate Chase (later Kate Chase Sprague) in 1855. Library of Congress.

Kate Chase (later Kate Chase Sprague) in 1855. Library of Congress.Nine years later, Washington – and the rest of the country – was consumed by the disputed outcome of the presidential election putting Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden. One of the big mysteries as Congress searched for a solution to the crisis involved Conkling.

The typically outspoken and hyper-partisan New York Republican had been uncharacteristically quiet during the campaign and the tumultuous weeks that followed. As the election crisis escalated, many in Washington and New York wondered what — if anything — Conkling would do.

As recounted by Hudson, he ran into Kate — now Kate Chase Sprague, the unhappily married wife of former Rhode Island Republican senator William Sprague — as he was seeing off a visiting friend at a Washington train station. After an exchange of pleasantries, she disclosed that Conkling backed the formation of a bipartisan 15-member commission to adjudicate disputed election returns and would make a speech in support of it.

“That afternoon the Brooklyn Eagle printed a ‘beat’ — an exclusive story that made a sensation,” Hudson recalled.

It turned out that an even more sensational story — one that Hudson missed — lurked behind his scoop. Sprague and Conkling were lovers — a fact unknown at the time but would explode into the headlines three years later when her drunken husband publicly confronted Conkling in Rhode Island. Did Hudson encounter Kate on her return from a liaison in Baltimore with Conkling? “If so,” Hudson admitted, he “was on the edge of what in a short time became a nation-wide scandal.”4

Roscoe Conkling as caricatured in Puck.

Roscoe Conkling as caricatured in Puck.Serendipity played a role when Hudson witnessed a dramatic behind-the-scenes moment at the 1880 Republican National Convention. After 36 ballots, delegates nominated dark-horse James A. Garfield for president and defeated the bid for a third term in the White House by former president Ulysses S. Grant. Conkling backed Grant and delivered a powerful nominating speech on his behalf and was furious that he failed.

Hudson recalls that he was in an empty room off the convention floor when an infuriated Conkling — unaware of Hudson’s presence — walked in to blow off some steam. He became even angrier when Chester Alan Arthur, Conkling’s “Stalwart” Republican ally and one-time head of the Port of New York, disclosed that Garfield had offered him the vice-presidential spot on the ticket and that he intended to take it.

“If you wish my favor and my respect you will contemptuously decline it,” Hudson heard Conkling say.

“Senator Conkling, I shall accept the nomination and I shall carry with me the majority of the delegation,” Arthur replied.

Conkling stormed out of the room “in a towering rage,” Hudson recalled. For days afterward Conkling stewed about his defeat in Chicago. He called Garfield an “angleworm” and remained ambivalent about the Ohioan even as he campaigned for him.5

William Cadwalader Hudson from his Recollections of a Political Reporter.

William Cadwalader Hudson from his Recollections of a Political Reporter.Hudson saw Blaine up close later that summer. Republicans campaigned for Garfield by relying on tried-and-true tactics honed in the aftermath of the Civil War. Orators railed against Democratic sympathy for secession and waved the “bloody shirt” to remind voters — and Civil War veterans in particular — of the sacrifices made the preserve the Union.

But the crimson red of the bloody shirt was fading and Northern voters were no longer responding to it with the enthusiasm they displayed a decade earlier. This became apparent in Maine, where state elections in September saw the Democratic-Greenback candidate for governor eek out a narrow in over the Republican incumbent. It was a warning for the party and a black eye for Blaine, whose state organization was shocked by the defeat.

Another politician might have kept his head down after an embarrassment of this kind. But audacity ranked among the characteristics that made Blaine an effective politician. He also possessed a keen sense of public opinion — and he wasted little time urging Republicans to change course.

Hudson was at Republican National Committee headquarters in New York a few days after the Maine elections when Blaine burst in and, dispensing with pleasantries, urged party managers to “fold up the bloody shirt and lay it away.” The party should run on its economic record as the disastrous effects of the Panic of 1873 finally began to fade. In particular, Blaine demanded that Republicans emphasize their support for protective tariffs in light of the Democratic platform’s call for “a tariff for revenue only.”

“Those foolish five words,” Blaine insisted, “give us a chance.”6

In the final weeks of the campaign, Blaine, Conkling, and other Republican orators began to stress tariffs and economic issues. The Republican campaign benefited from an unforced error by Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock, who characterized tariffs as a “local issue” in an interview with a Democratic newspaper. Garfield went on to win a narrow victory in the popular vote but a decisive majority in the Electoral College.

Four years later, it was Democrats who took advantage of a Republican miscue for which Blaine was directly responsible. In the closing days of the 1884 presidential campaign, Blaine won the endorsement of a collection of clerics at a meeting in New York City. As he stood by, Blaine listened as the Rev. Samuel D. Burchard praised the Republican nominee and asserted that the assembled representatives of the clergy could never in good conscience support any candidate nominated by the party of “rum, romanism and rebellion.”

James G. Blaine as rendered in Puck in 1884.

James G. Blaine as rendered in Puck in 1884.Blaine later confided that he hoped it would have gone unnoticed by the press. The usually politically astute Blaine blundered badly. The comment was picked up by newspapers and, as Hudson recalls, Democrats seized on it with glee. “If anything will elect Cleveland these words will do it,” Maryland Senator Arthur Gorman predicted.7 Blaine eventually disavowed the comment, but Democrats circulated it at Catholic churches nationwide.

Blaine narrowly lost to Cleveland. A number of factors contributed to his defeat, but in immediate aftermath of the loss the Plumed Knight conceded Burchard’s comments, along with inclement conditions, played a decisive role in his loss. “As the Lord sent upon us an ass in the shape of a preacher, and a rainstorm, to lessen our vote in New York, I am disposed to feel resigned to the dispensation of defeat, which flowed directly from those agencies,” Blaine wrote to Murat Halstead.8

***

Be sure to check out my website, robertmitchellbooks.com, for information about The Partisans and my books about the Credit Mobilier scandal and Iowa Populist James B. Weaver.

William C. Hudson, Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter (New York: Cupples & Leon Company, 1911, p. 14. Hereafter referred to as Hudson. ︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion: The Making of a President 1884 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, 2000) pp. 98, 177; Peg A. Lamphier, Kate Chase and William Sprague: Politics and Gender in a Civil War Marriage (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), p. 135; David Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice in the Senate (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1971), p. 342.

︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion: The Making of a President 1884 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, 2000) pp. 98, 177; Peg A. Lamphier, Kate Chase and William Sprague: Politics and Gender in a Civil War Marriage (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), p. 135; David Jordan, Roscoe Conkling of New York: Voice in the Senate (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1971), p. 342.  ︎Hudson, pp. 18-19.

︎Hudson, pp. 18-19.  ︎Ibid., pp. 22-23.

︎Ibid., pp. 22-23.  ︎Ibid., pp. 97-99.

︎Ibid., pp. 97-99.  ︎Ibid., p. 112.

︎Ibid., p. 112.  ︎David G. Farrelly, “’Rum, Romanism and Rebellion’ Resurrected, The Western Political Quarterly, June 1955, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 26; Hudson, p. 209.

︎David G. Farrelly, “’Rum, Romanism and Rebellion’ Resurrected, The Western Political Quarterly, June 1955, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 26; Hudson, p. 209.  ︎Murat Halstead, “The Defeat of Blaine for the Presidency,” McClure’s Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 2, January 1896, p. 169.

︎Murat Halstead, “The Defeat of Blaine for the Presidency,” McClure’s Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 2, January 1896, p. 169.  ︎

︎

July 29, 2024

The power of enemies and the dangers of “friends”

James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling benefited from the enemies they made. Their allies? Not so much.

Enemies were often more useful for James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling than friends.

The rivalry between Blaine and Conkling helped define the 1870s and early 1880s, but their 18-year battle for supremacy in the Republican Party is replete with examples of how they took aim at other opponents to define and position themselves on the great issues of the day.

These spats often proved more useful than allies who were foisted on them by circumstance. Attack, whether the target was Andrew Johnson or Ben Butler, strengthened their standing with Republicans. At the same time, friends of Blaine and Conkling proved to be serious liabilities at key moments in their careers.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming out Oct. 15 from Edinborough Press.

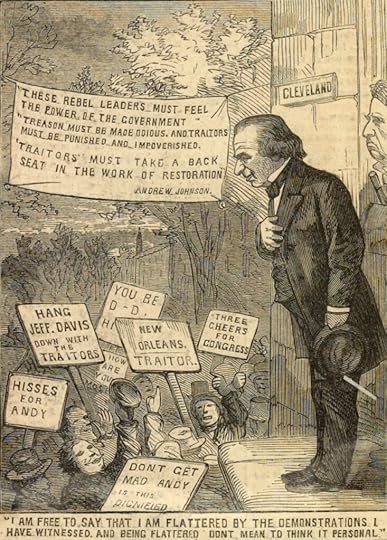

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age is coming out Oct. 15 from Edinborough Press.Andrew Johnson: In the aftermath of the Civil War, no figure in American politics infuriated Republicans quite like the Tennessee Democrat chosen by Abraham Lincoln as his vice-presidential running mate in 1864.

Roscoe Conkling as rendered in Puck

Roscoe Conkling as rendered in PuckAlthough he signaled in the days after Lincoln’s assassination that he would be tough on defeated rebels, Johnson pursued a conciliatory policy toward the former Confederacy. He pardoned thousands of former Confederates and rushed to readmit rebellious Southern states to full participation in national affairs. He fought bitterly against congressional Republicans, who were infuriated with his lenient approach.

Johnson took his case to the people in the infamous “Swing Around the Circle” speaking tour of 1866. It didn’t go well, as Blaine observed in the second volume of his Twenty Years of Congress. “Wit and sarcasm were lavished at the expense of the president, gibes and jeers and taunts marked the journey from its beginning to its end.”

Thomas Nast’s rending of Andrew Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” stop in Cleveland. Library of Congress.

Thomas Nast’s rending of Andrew Johnson’s “Swing Around the Circle” stop in Cleveland. Library of Congress.Campaigning that year for reelection to the House (and simultaneously for his election to the U.S. Senate by the New York state legislature in January), Conkling left no doubt of his contempt for the deeply unpopular Johnson and his policies. He compared the president to French Emperor Louis Napoleon and called him “an angry man, dizzy with the elevation to which assassination has raised him.” When voters cast their ballots, Conkling predicted, “Andrew Johnson and his policy of arrogance and usurpation will be snapped like a willow-wand.”

Conkling didn’t stop there. Noting that the congressional Joint Committee of Reconstruction’s documentation of widespread violence against formerly enslaved Black Southerners foreshadowed racial violence in Memphis and New Orleans, he charged that Johnson’s policies dishonored Union war dead.

“Not satisfied with betraying the country by official action and by secret plotting; not satisfied with conniving at the robbery and murder of Unionists, and the exaltation and reward of traitors at the South, he comes now to buffet and slander the Union people of the North, and to blacken the memory of their dead,” Conkling thundered. His passionate rhetoric paid off. Conkling easily won reelection in November and, two months later, was elected to the U.S. Senate by the New York state legislature.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.Benjamin Butler: Blaine lacked Conkling’s taste for confrontation but — as he proved in 1866 when he mocked Conkling’s “grandiloquent swell” and “overpowering turkey-gobbler strut” — he could open fire on an opponent when antagonized.

Butler of Massachusetts was a radical Republican and former Union Army general reviled in the South for his treatment of civilians following the Union capture of New Orleans. So-called “liberal” Republicans opposed his approach to Reconstruction and loathed his support for monetary policies that favored paper money. He had plenty of enemies — and Blaine became one of them.

With terrorist violence against Black Southerners roiling the South in the early 1870s, Butler wanted the federal government to take vigorous action to ensure peace at the polls and protect civil rights. The general thought he had won the support of the House Republican caucus for legislation that would do so but was infuriated to discover that Blaine favored an alternative proposal. The Speaker’s plan — formation of a committee to investigate conditions in the former Confederacy — won passage in the House. Butler’s proposal never reached the floor.

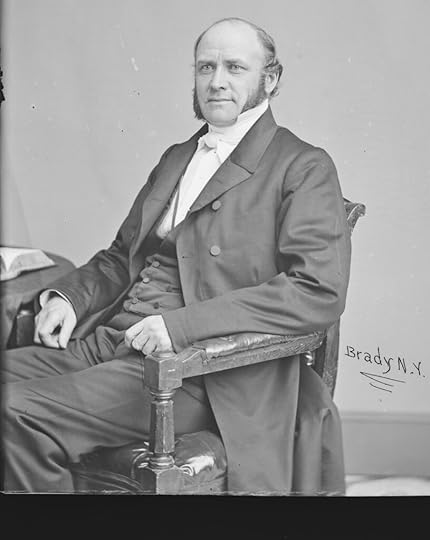

Benjamin Butler. Library of Congress.

Benjamin Butler. Library of Congress.Furious, Butler circulated a letter to fellow Republicans denouncing Blaine and charging that the Speaker’s bill passed thanks to a backroom deal with pro-tariff Democrats. “Butler is more enraged to-night than during the proceedings to-day, if that were possible,” the Chicago Tribune reported. “He attributes his discomfiture not only to the connivance but to the actual assistance rendered by Speaker Blaine.”

Blaine reacted decisively and angrily. He stepped down from the Speaker’s chair — a dramatic parliamentary maneuver that signaled how seriously he regarded Butler’s allegations. He reminded the House that before the war Butler was a Democrat who supported the nomination of Jefferson Davis for president. Although Butler was an “astute lawyer,” his criticism showed that he was “extremely ignorant of the rules of the House.”

Most of all, Blaine took exception to what he believed was the insulting nature of Butler’s letter to the House. “As such I resent it. I denounce the letter in all its essential statements, and in all its misstatements, and in all its mean inferences and meaner innuendos,” the usually amiable Maine lawmaker declared.

Blaine’s friends in the congressional press gallery hailed his “passionate eloquence” the next morning. The Chicago Tribune said nothing like it had been heard in the House since Blaine’s famous retort to Conkling five years earlier.

President Ulysses S. Grant rendered Blaine’s investigative committee moot when he demanded congressional action to stem Southern violence. Congress obliged, and Grant came to Capitol Hill to sign what became known as the Ku Klux Klan Act. Nevertheless, Blaine’s colorful display of indignation signaled his eagerness to align with Republican moderates and liberals who loathed the Massachusetts radical and everything he stood for.

Thomas C. Platt: Conkling faced the greatest political crisis of his career with an ally who encouraged him to make a bad decision and made matters worse with a stunning lapse of judgment as Conkling fought for his political life.

Thomas C. Platt in 1901. Library of Congress.

Thomas C. Platt in 1901. Library of Congress.A two-term member of the House, Platt came to the Senate in 1881 with a secret that, of revealed, would have put him at odds with Conkling. To win the support of dissident Republicans in Albany, Platt promised to vote for any nominations made by new president James A. Garfield, even if they were opposed by New York’s senior senator. That promise suddenly became problematic when Garfield nominated Conkling foe William Robertson to run the patronage-rich Port of New York — the basis of Conkling’s political power.

Faced with making good on his promise and antagonizing Conkling, Platt settled on a drastic course of action: He would resign his Senate seat only weeks after taking office. He shared the idea with Conkling, without disclosing his reasons for doing so. While it is unlikely that Platt talked the Conkling into resigning, he put the idea on the table. In the biggest mistake of his political career, Conkling followed suit. Conkling and Platt resigned May 16, 1881.

Weeks later, both changed their minds and resolved to win reelection to their Senate seats. But New York Republicans who had long chafed under Conkling’s imperious leadership balked at sending the man dubbed “Lord Roscoe” by the press back to Washington.

Their joint campaign took a severe jolt at the end of June when scandal engulfed Platt. Opponents spotted him entering his hotel room with a woman who was not his wife. Word of the apparent indiscretion spread and a stepladder that allowed his foes to peep into his room was procured. “The details of the scene are unfit for publication,” the Chicago Tribune sniffed. Platt “has been brought before the public gaze in a manner which has filled his friends with shame and humiliation.”

Platt dropped out of the race July 1, complicating Conkling’s bid for reelection. A day later, Charles Guiteau shot Garfield in a Washington train station. Widely blamed for creating the political tensions that stoked the fury of the deranged gunman, Conkling lost his bid to return to the Senate three weeks later.

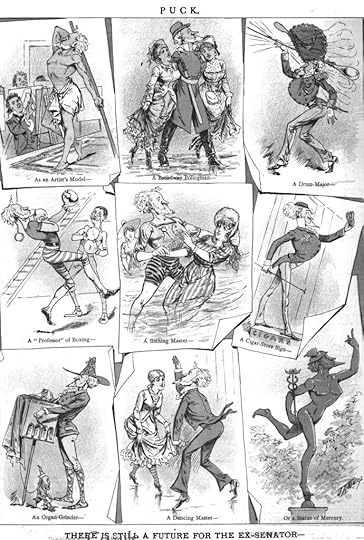

Puck speculates about Conkling’s future after leaving the Senate.

Puck speculates about Conkling’s future after leaving the Senate.Rev. Samuel D. Burchard: The 1884 presidential campaign pitting Blaine against New York Democratic Gov. Grover Cleveland was nearing its end. Blaine had just completed an exhausting whistlestop campaign tour of New England, the Midwest, and western New York and prepared to receive what promised to be a relatively routine endorsement from a gathering of clergy on Oct. 29.

The spokesman for the ministers gathered at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City was a Presbyterian cleric, Rev. Samuel Burchard. He greeted Blaine with standard boilerplate about how the clergy expected Blaine to “do honor” to the presidency (a not-so-veiled allusion to disclosures that Democrat Grover Cleveland had fathered a child out of wedlock). Burchard concluded with a pointed condemnation of Blaine’s foes. “We are Republicans, and don’t propose to leave our party and identify ourselves with the party whose antecedents have been rum, Romanism, and rebellion. We are loyal to the flag, and we are loyal to you.”

Rev. Samuel D. Burchard. National Portrait Gallery.

Rev. Samuel D. Burchard. National Portrait Gallery.Perhaps Blaine, worn out by the campaign, was too tired to respond. Perhaps, as many have suggested, he didn’t hear what Burchard said (although others did). Blaine himself confided to Supreme Court justice John Harlan that he chose to ignore the comment in the hopes that the press wouldn’t pick up on it. It was a huge mistake, and Democrats quickly attacked.

“It is amazing that a man as quick-witted as Blaine, accustomed to think on his feet and meet surprising changes in debate, should not have corrected the thing on the spot,” Democratic campaign operative Sen. Arthur Gorman marveled. Gorman made sure Burchard’s comments circulated widely.

Cleveland narrowly defeated Blaine by carrying New York state — the biggest electoral prize in the election — by 1,047 votes. In the years that followed, whispers that Blaine had been the victim of vote fraud in New York gained credence among some Republicans, although Blaine himself never challenged the results. Even those who suspected Democrats stole votes in New York acknowledged that the ill-considered alliteration of the enthusiastic Protestant minister was just as responsible for Blaine’s defeat in the Empire State. “I suppose also,” Massachusetts Republican George Frisbie Hoar conceded as he recounted charges of fraud at the polls, “that but for the utterances of a foolish clergyman named Burchard, Mr. Blaine’s majority in that State would have been so large that these frauds would have been ineffectual.”

My author’s website, RobertBMitchellbooks.com, is now live. Check it out for biographical information and links to my previous works about the Credit Mobilier scandal and Iowa Populist James B. Weaver.

July 11, 2024

“The Partisans” cover

Publication is set for Oct. 15.

Edenborough Press today unveiled the cover for The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age.

June 17, 2024

Losing the South “to save the North”

In his history of the post-Civil War South, Mississippi Republican John R. Lynch recounted the thinking that drove Republicans to back away from their support for Reconstruction.

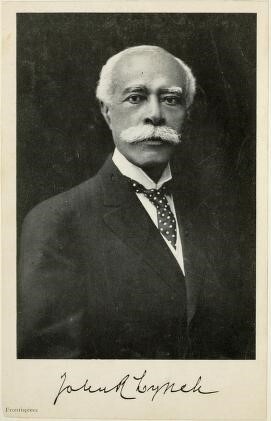

He began life in slavery and served in Congress. He knew James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling and President Ulysses S. Grant. In the early 20th century, when conventional wisdom dismissed the post-war Republican plan to rebuild the political order of the South as hopelessly flawed, he wrote a thoughtful and illuminating rebuttal, The Facts of Reconstruction, published in 1913.

John R. Lynch was one of the most remarkable political figures of the Gilded Age. Born in Louisiana to a white father and Black mother, Lynch and his mother were sold to a Mississippi enslaver following his father’s death, according to Maurine Christopher’s Black Americans in Congress. After the Union Army liberated Natchez during the Civil War, Lynch taught himself to read, worked as a photographer, attended night school, and became an active Republican, Christopher wrote.

John R. Lynch, from The Facts of Reconstruction.

John R. Lynch, from The Facts of Reconstruction.Lynch served four years in the Mississippi legislature and was elected Speaker before coming to Washington after winning a seat in the House in 1872. A skilled orator and writer, he was re-elected in 1874 but defeated two years later. Lynch returned to the House for two more years after winning an election in 1880. Four years later he was elected temporary chairman of the Republican National Convention in Chicago after he was nominated by Theodore Roosevelt. In 1896, Lynch was admitted to the Mississippi Bar after studying to become a lawyer, according to his congressional biography.

His first two terms in Congress provided a unique perspective as congressional Republicans — and Grant — began to move away from wholehearted support for the multi-racial Reconstruction state governments of the South.

In 1874, with the economic devastation caused by the Panic of 1873 still top of mind for millions of voters, Democrats rode a wave of popular discontent with Republican economic policies to take control of the House for the first time since 1858. “The victory in the presidential election of 1872 had been so sweeping,” James G. Blaine wrote in the second volume of Twenty Years of Congress, “that it seemed that no re-action were possible for years to come.”

The midterm elections of 1874 demonstrated that the aftermath of the war no longer ranked as the primary concern for millions of Northern voters, who were now more worried about keeping a roof over their heads than conditions in the former Confederacy. Northern Republicans took note and adjusted accordingly, Lynch concluded. The Republican Party in the South, Lynch wrote, was “young, weak, and comparatively helpless,” he wrote. It continued to need the support of its Northern “parent,” which had been “carried away from the battlefield seriously wounded and unable to administer to the wants of its Southern offspring.”

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine. Library of Congress.What that meant quickly became clear. In January 1875, federal troops were dispatched to the Louisiana state legislature to prevent Democrats from violently taking control. Outraged Northern public opinion signaled that support for Reconstruction was in rapid decline. In March, during the closing hours of the Forty-Third Congress, the House debated legislation that would allow the prosecution of election violence in federal courts and the president to suspend habeas corpus in areas plagued by terrorism. Blaine, in one of his last acts as House Speaker, allowed debate on the bill to drag on until it was no longer possible for the measure to get on the Senate calendar. The House passed the bill, but with time running out and Democrats poised to take control of the House, it was dead.

Lynch was stunned and sought an explanation.

“In my judgment, if that bill had become law the defeat of the Republican Party throughout the country would have been a foregone conclusion,” Blaine said. “In my opinion it was better to lose the South and save the North, than to try through such legislation to save the South, and thus lose both North and South.”

Blaine wasn’t the only Republican thinking that way.