Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 83

November 10, 2012

What I've learned from reading aloud, by Jane Clarke

Picture books are designed to be read out loud by an adult sitting next to a child – and I adored reading them that way to my sons when they were small. Later on, as a library assistant at Antwerp International School, I read face to face, holding the books open and reading the words upside down and sideways, so that a whole class of children could see the pictures. I often do that today, on author visits to schools.

Back them, I had no idea that I would end up writing picture books – but without realising it, I absorbed the pace and cadence of a picture book, and I learned:

Different characters have different voices.

From Trumpet the Little Elephant with the Big Temper, illustrated by Charles Fuge

From Trumpet the Little Elephant with the Big Temper, illustrated by Charles Fuge

Page turns have drama.

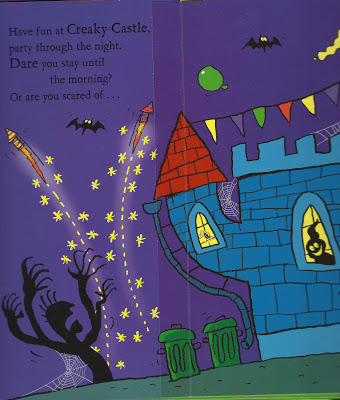

From Creaky Castle, illustrated by Christyan Fox

From Creaky Castle, illustrated by Christyan Fox

There are opportunities to vary the speed and tone of the reading. From Knight Time, illustrated by Jane Massey

From Knight Time, illustrated by Jane Massey

Words can be enjoyed for their sound and rhythm.

From Dance Together Dinosaurs, illustrated by Lee Wildish

From Dance Together Dinosaurs, illustrated by Lee Wildish

Jokes and puns in the words and the pictures can be quite sophisticated and enjoyed on two levels – the adult and the child.

From Gilbert the Great, illustrated by Charles Fuge. Charlie slipped in some pictorial references to the Jaws movies.

From Gilbert the Great, illustrated by Charles Fuge. Charlie slipped in some pictorial references to the Jaws movies.

It’s fun to join in a refrain (but don’t overdo it).

From Stuck in the Mud, illustrated by Garry Parsons

From Stuck in the Mud, illustrated by Garry Parsons

Reading out loud is an important part of the process when you’re writing picture books. It helps highlight where the text isn’t working. I find it hard to read into thin air, but I can usually find an audience of some sort...

Some picture books work best snuggled up quietly, some work best shared with large groups of noisy youngsters. What picture books do you love to read out loud?

Back them, I had no idea that I would end up writing picture books – but without realising it, I absorbed the pace and cadence of a picture book, and I learned:

Different characters have different voices.

From Trumpet the Little Elephant with the Big Temper, illustrated by Charles Fuge

From Trumpet the Little Elephant with the Big Temper, illustrated by Charles FugePage turns have drama.

From Creaky Castle, illustrated by Christyan Fox

From Creaky Castle, illustrated by Christyan FoxThere are opportunities to vary the speed and tone of the reading.

From Knight Time, illustrated by Jane Massey

From Knight Time, illustrated by Jane Massey

Words can be enjoyed for their sound and rhythm.

From Dance Together Dinosaurs, illustrated by Lee Wildish

From Dance Together Dinosaurs, illustrated by Lee WildishJokes and puns in the words and the pictures can be quite sophisticated and enjoyed on two levels – the adult and the child.

From Gilbert the Great, illustrated by Charles Fuge. Charlie slipped in some pictorial references to the Jaws movies.

From Gilbert the Great, illustrated by Charles Fuge. Charlie slipped in some pictorial references to the Jaws movies.It’s fun to join in a refrain (but don’t overdo it).

From Stuck in the Mud, illustrated by Garry Parsons

From Stuck in the Mud, illustrated by Garry ParsonsReading out loud is an important part of the process when you’re writing picture books. It helps highlight where the text isn’t working. I find it hard to read into thin air, but I can usually find an audience of some sort...

Some picture books work best snuggled up quietly, some work best shared with large groups of noisy youngsters. What picture books do you love to read out loud?

Published on November 10, 2012 00:00

November 6, 2012

Online writing communities for picture book writers: inspirational or distracting? A look at some gems including PiBoIdMo, 12 x 12 in '12 and online critique groups that really work. By Juliet Clare Bell

Me with one of my books that was brought to life by an online writing community. No really.

Me with one of my books that was brought to life by an online writing community. No really.The romantic notion of the lone wolf writer, hidden away in some shed (or tucked up under a warm duvet in bed), scribbling away without distraction, may be true for some of us some of the time, but for many of us, the reality is that we’re usually sat at a computer (and often with lots of other things going on around us).

(Unfortunately, the 'other things' as I write tonight include a small child and a sick bowl.)

(Unfortunately, the 'other things' as I write tonight include a small child and a sick bowl.)Are we writing our stories with the internet switched off? How often do we switch between our manuscript and email or FaceBook (just for five minutes. If I were at work, I’d talk to someone every so often, wouldn’t I?)

Well, there are loads of things to distract us online. But just in case you’re not quite distracted enough, I thought I’d share some more with you. Only these ones are so valuable to me as a picture book writer that I’m sharing them not so we can all be distracted together and share the guilt, but because if you haven’t already discovered these online writing communities and you also write picture books, then you might find them helpful too…

I love November. I really do. And a growing number of children’s picture book writers –published and working-towards-being-published- are also finding the cold, dark and wet month of November inspirational. But why…?

(or HoItNoAg -Hooray, it’s November again! –but don’t remember this acronym. I just made it up)

(or HoItNoAg -Hooray, it’s November again! –but don’t remember this acronym. I just made it up)I appear to be a fan of groups with acronyms that no one is quite sure how to pronounce. The Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators is an amazing organisation with almost as many ways of pronouncing the acronym as members (ok, well perhaps not –there are well over 20000 members worldwide, but it’s called, Scooby or Scwibby or Scibwee with such confidence by various members, that I can’t side with any of them and spend twice as long pronouncing it ESS-CEE-BEE-DOUBLEYOU-EYE). PiBoIdMo is Picture Book Ideas Month. I’ve always pronounced it Pie-Bow-Id-Moe. It turns out others call it something else. But actually, who cares? It’s an online thing and although you may end up writing it loads online, you’ll probably rarely say the word out loud to anyone other than yourself.

This is not another NaNoWriMo where you’re expected to write a novel in a month (and there are many opinions on the merits or otherwise of NaNoWriMo). Picture Book Ideas Month works very differently. It simply encourages every person who signs up to it to attempt to come up with thirty ideas for picture books in thirty days during November. It sounds simple, right? And something you don’t need an online community for –any writer can set himself or herself that task alone, do it and have plenty of ideas to pick and choose from for the coming year… Except PiBoIdMo is so much more than that –because of the online community that it has become. I asked creator, Tara Lazar (author of The Monstore) about it.

Incredibly, she managed to get back to me in spite of being caught up and powerless in Hurricaine Sandy:

Incredibly, she managed to get back to me in spite of being caught up and powerless in Hurricaine Sandy: I had no idea PiBoIdMo would grow this popular--we have almost 700 participants this year. When it began in 2009, I thought I'd maybe get 10 people to try it with me. The enthusiasm that writers have for the event has blown me away. Plus I keep hearing about success stories--PiBoIdMo ideas that have gone on to win contests, grants and publishing contracts. I'm truly amazed by the creativity of our community and grateful to the guest bloggers and participants for their contributions to picture books.

If you write or illustrate picture books, I would highly recommend checking it out (and looking back over previous years’ posts, too). We’re six days into it and I’ve already got seventeen picture book ideas. Well, ideas may be a grand way of describing them, but they're seeds, and I'll keep reading through them and adding bits as the weeks go on. Not all of them will end up as picture book manuscripts. If I find five or six ideas to work on out of forty or so I've come up with by the end of November, then I’ll be very happy.

Of my 2011 ideas, a couple, which I worked into stories, are under consideration with a publisher; a couple I can safely say I’m unlikely to pursue (Day 8 and Day 27 spring to mind…). And about fifteen of them I still like and am waiting for the right time for them to develop into something more than an idea. It could take weeks, or it could take years. But they’re there and waiting for me.

Penny Morrison, one of the commenters on today’s PiBoIdMo post, said something similar:

…writing picture books seems to be about waiting. A bit of planting and watering, but mostly waiting.

PiBoIdMo has guest blog posts every day throughout the month, from authors, illustrators, editors and agents. Some are great for generating ideas; some inspire; some provide that all-important introduction to an editor or agent (and there are giveaway critiques with some of the editors and agents for those who are signed up).

I love the posts where I'm encouraged to generate ideas in certain ways, which in previous posts has included going through photos...

Any ideas, anyone?

Or children's drawings (try looking at them first and then ask the child what it's actually about. It can be illuminating)...

Anyone like to guess what this story is about? (OK -first, the doorbell rings -DING DONG- then the boy answers the door. He sees that it's a witch (who looks very cute and smiley in the picture but it's obviously an act) and thinks about his toaster. Then he thinks 'I can put the witch in the toaster!' and all is ok once more...)

Anyone like to guess what this story is about? (OK -first, the doorbell rings -DING DONG- then the boy answers the door. He sees that it's a witch (who looks very cute and smiley in the picture but it's obviously an act) and thinks about his toaster. Then he thinks 'I can put the witch in the toaster!' and all is ok once more...)Now this one looks more straightforward...

But perhaps it's not...

But perhaps it's not...PiBoIdMo participants include those with lots of books under their belts and those writers who are just starting out.

Corey Rosen Schwartz, author of The Three Ninja Pigs, wrote up her idea number 28 and it was bought by Putnam (I quite like my no. 28 from last year, too. I might still write that into a story. But my no. 27? Now that's unlikely to have been quite as successful…).

I love PiBoIdMo. I always get 30 ideas (at the very least) in 30 days and I feel like I'm part of something at the same time. And it gets me back into good habits about being present and receptive to any hints of a story in my surroundings. But where do you turn to next online, once you've got your creative juices flowing and have all those picture book ideas...?

I came up with the idea for 12 x 12 as a way to increase my own PB-writing output using all of the great ideas I was mining in PiBoIdMo. I figured if I needed the motivation of a challenge, maybe others did too. So I sent out the notice and let people sign up. I expected maybe 50 people to join me.

Well, 400 signups later, 12 x 12 has become much more than a writing challenge. It has become a genuine community where participants learn from each other, help one another and offer support and encouragement… We keep each other going.

Julie Foster Hedlund

And what do other writers say about it? Susanna Leonard Hill, author of April Fool, Phyllis! and Can't Sleep Without Sheep:

There are always things I can do better and ways I can improve my craft. So I joined … PiBoIdMo partly for all the excellent author interviews and tips on writing. But the main reason I joined both [PiBoIdMo and 12 x 12 in ’12] was for the community, the camaraderie, and the inspiration. Writing can be a lonely business sometimes, and it's nice to feel like you're part of a group who understands all the joys and frustrations.

There are plenty of people in the group who will end the year with twelve manuscripts.

Yay!

Yay!I won’t be one of them

Oh no. Really?

Oh no. Really?–I should end up with nine. But that doesn’t matter. I’ll still have written more than I would have done without it.

Hooray!

Hooray!–as will Deb Lund

With marketing books, revising a middle-grade novel and doing school visits and conference presentations, it's not always easy to find time to write. With PiBoIdMo pestering—um, encouraging—me to keep up with new ideas, and the 12x12 deadline—um, encouragement again—I wouldn't be writing as many new pieces or getting to know the wonderful creators and participants. I'm looking forward to writing a post on the PiBoIdMo blog later this month, and to having thirty more picture book ideas than I would have had if not for also being a participant.

For Lori Degman, author of the award-winning 1 Zany Zoo:

the most valuable thing about both PiBoIdMo and 12X12 - the people! I have learned so much from the creative and generous authors and illustrators in this group and I feel I've made a lot of friends, though we may never meet in person.

You can sign up for 2013's 12 x 12 here.

Is it any coincidence that these writing communities have sprung up in the US? With so many people spread over such a huge area, belonging to online communities may be much more realistic than in-person ones. Penny Klosterman (Barbara Karlin 2012 runner up) says of the online 12x12 community:

This is extremely beneficial to a gal who would have to drive 3 hours one way to meet a regional chapter of SCBWI.

And this brings me onto my third online writing community (since Penny is a member of this group, too): my online critique group.

In an online critique group where you don't ever meet in person (with the majority of the group, at least) it's (almost) all about the books...

In an online critique group where you don't ever meet in person (with the majority of the group, at least) it's (almost) all about the books...I probably spend an hour and a half a week on this group, and it’s a very important part of my life. And yet I’ve only met two of the other members (there are eight of us). In fact, I wouldn’t even recognise five of them if they past me on the street (which is unlikely since they live in the States and I’m in the UK) and yet I have a really special bond with them. It’s taken a while to find the perfect online group, but it’s absolutely worth it.

But what makes it work? Rebecca Colby, Winner of Barbara Karlin, 2011:

While we're spread out over two continents and divided by an ocean, we are united in our love of picture books and our confidence in and support of each other's work. We may not be on each other's doorsteps, but we communicate more often than most in-person friendships… Every success is celebrated and every rejection is commiserated amongst friends that can truly empathise. I'd be lost without my critique group… I'm sure I could embrace an in-person picture book critique group, but it is rare to find so many people writing for the same age group in one area and at the same stage of their writing career.

And that’s crucial: no one feels like they’re putting more into it than they’re getting back. It works because we’re all at a similar level and everyone knows how we can help each other progress.

We bounce ideas off each other, push each other to think beyond the first few solutions that come to mind. We are quick to encourage but also brutally honest.

Kristin Gray

They are my support system. They continue to push me to become a better writer... Sherry Dargert

There are a great many more online writing communities, including joint blogs like PictureBookDen, which I love being a part of. And I’m a huge advocate of SCBWI (hmmn, did I ever mention that before?). But fortunately, for me, with the UK being small, I do see lots of SCBWI members throughout the course of a year (and especially at the annual conference -the other reason I love November). Our online communications, through a Yahoo group (for which you have to be a member) and the FaceBook group (for which you don’t –anyone can join) are really important and form a regular part of my day to day working environment but PiBoIdMo, 12 x 12 in ’12 and my critique group are truly online in that I’m unlikely ever to meet the vast majority of these people I spend so much virtual time with.

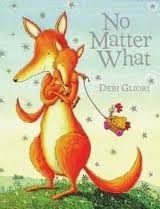

Online writing communities don’t always work. I know I spend too much time on Facebook for example, even though the majority of my FaceBook friends are writers, and I am guilty of kidding myself into thinking things are work that actually aren’t… And there have been upsetting stories about internet trolls recently, one where much loved picture book author and illustrator, Debi Gliori, has been bullied as a result of a complete misunderstanding of the nature of ideas and copyright.

One of my all-time favourite picture books: Debi Gliori's No Matter What. And for any of you over in the States reading this blog, I urge you to get hold of the original UK version which deals with death in a beautiful way (but which had to be changed for the US edition).

One of my all-time favourite picture books: Debi Gliori's No Matter What. And for any of you over in the States reading this blog, I urge you to get hold of the original UK version which deals with death in a beautiful way (but which had to be changed for the US edition).But it can work brilliantly and help us to be more creative and feel less isolated.

What are your experiences of online writing communities? Have you got any favourites you’d like to share? And in the spirit of helping out other picture book writers as happens so much in online writing communities such as PiBoIdMo and 12 x 12 in 12, do you have any discarded PiBoIdMo ideas that you’re happy for others to use? Let's see if anyone can get a decent idea for a story (you don't have to share the idea, just whether you've got one) from other people's discarded ideas... you're welcome to my 2011 ideas no. 8 and 27, though they're not the best: 'underwater pants' [8], and ‘I wish I was made out of recycled paper’ [27]). Do you have any success stories from virtual groups you belong to? How do you get the balance right between checking things like blogs and groups online and actually writing?

I’d love to hear from you.

Juliet Clare Bell is the author of Don't Panic, Annika! (illustrated by Jennifer E Morris; Piccadilly Press); Pirate Picnic (Franklin Watts) and The Kite Princess (illustrated by Laura-Kate Chapman and narrated by Imelda Staunton; Barefoot Books).

Click on the links for tips on how (not) to write a rhyming picture book;

Published on November 06, 2012 15:35

October 31, 2012

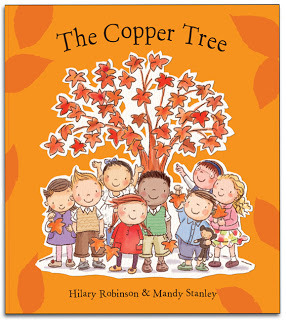

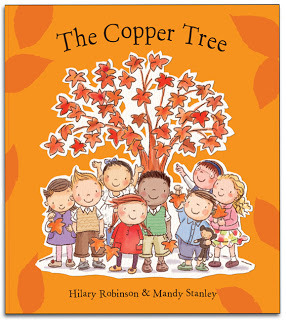

How To Talk To Children About Death by Hilary Robinson (Guest Blog)

Caroline’s last hours in the hospice were peaceful for her but they were painful for us. When the phone call finally came that she had died, despite the inevitability, the emotion was overwhelming.

Caroline had battled breast cancer for seven years before dying at the age of 39. In the days that followed I thought a lot about her parents, and husband, but I thought also about the children in our families as well as the children at the school where she’d been a much-loved teacher. To help my young daughters through their grief I encouraged them to think about the legacies their Aunt had left in terms of what she had shared, taught and imparted and in what was probably an effort to exorcise the grief, I then wrote a story about a teacher who dies.

The Copper Tree developed into a story of a small group of young school children who are encouraged to prepare for, and come to terms with, the subsequent death of their teacher, Miss Evans. At the centre of it all I considered the simple needs of young children, many of whom would be exploring the feelings of grief and loss for the first time. I realised that a relationship with a teacher mirrored so many relationships in other areas of our lives – from parents, family, wider family, friends and even pets.

I wanted the story to be real and accessible and revised core elements of the text after seeking advice from bereaved families, from teachers and bereavement consultants. One mother whose seventeen-year-old son had died from cancer told me that those with terminal illness, quite often – despite the pain and fear – remain cheerful. They see and appreciate the pure beauty of life and find joy in simple pleasures. Justine, a young mother of three children who was dying of breast cancer was critical of the lack of books that featured people as main characters, rather than animals, while teachers advised against using ambiguous language - saying to a young child we have "lost" someone can lead them to believe that we may find them again and when a friend was told, as a young girl, that her grandmother had died of a stroke, she became then fearful of stroking the cat. I also avoided whimsical notions of heave, leaving parents, teachers and carers free to consider those elements in their own respective and personal ways.

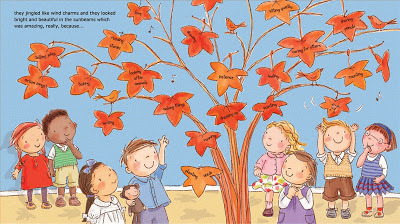

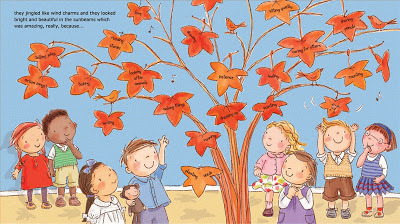

Dr Paul Fitzpatrick, an expert in bereavement counselling from Cardiff University, explained that ‘continuing bonds theory’ is now considered by many to be an integral part of helping those who grieve. Recognising and celebrating the legacies of those who have died is considered far more effective than ignoring, as previous generations have done, the fact that someone had ever existed and this was borne out when our local hospice, St Gemmas, established a Tree Of Life on to which bereaved relatives could hang copper leaves inscribed with the name of a loved one who had died.

So with all this is mind The Copper Tree took shape and in the story the children are gently taken through the difficult process. There are light hearted moments and moments of poignancy – just as in life - and following a period of reflection after the death of Miss Evans, they are encouraged to think about all that their teacher has shared with them - or taught them. These memories are then inscribed on to copper leaves and fixed on to a copper tree as a reminder of her lasting legacy.

We cherish our memories of Caroline and we are proud of the legacies she has left. The Copper Tree, may not have happened had it not been for her and that, in itself, remains a lasting legacy to her. We recognise also that, while at times the emotional pain has been difficult to bear, we have, as Caroline did in the end, found some measure of peace.

_____________________________________________________ The Copper Tree by Hilary Robinson,

The Copper Tree by Hilary Robinson,

illustrated by Mandy StanleyPublished by Strauss House Productions

ISBN: 978-0957124509

www.thecoppertree.org

Our Guest Blogger, Hilary Robinson,

has written over forty illustrated

children's books.

You can find out more at http://www.hilaryrobinson.co.uk/

Caroline had battled breast cancer for seven years before dying at the age of 39. In the days that followed I thought a lot about her parents, and husband, but I thought also about the children in our families as well as the children at the school where she’d been a much-loved teacher. To help my young daughters through their grief I encouraged them to think about the legacies their Aunt had left in terms of what she had shared, taught and imparted and in what was probably an effort to exorcise the grief, I then wrote a story about a teacher who dies.

The Copper Tree developed into a story of a small group of young school children who are encouraged to prepare for, and come to terms with, the subsequent death of their teacher, Miss Evans. At the centre of it all I considered the simple needs of young children, many of whom would be exploring the feelings of grief and loss for the first time. I realised that a relationship with a teacher mirrored so many relationships in other areas of our lives – from parents, family, wider family, friends and even pets.

I wanted the story to be real and accessible and revised core elements of the text after seeking advice from bereaved families, from teachers and bereavement consultants. One mother whose seventeen-year-old son had died from cancer told me that those with terminal illness, quite often – despite the pain and fear – remain cheerful. They see and appreciate the pure beauty of life and find joy in simple pleasures. Justine, a young mother of three children who was dying of breast cancer was critical of the lack of books that featured people as main characters, rather than animals, while teachers advised against using ambiguous language - saying to a young child we have "lost" someone can lead them to believe that we may find them again and when a friend was told, as a young girl, that her grandmother had died of a stroke, she became then fearful of stroking the cat. I also avoided whimsical notions of heave, leaving parents, teachers and carers free to consider those elements in their own respective and personal ways.

Dr Paul Fitzpatrick, an expert in bereavement counselling from Cardiff University, explained that ‘continuing bonds theory’ is now considered by many to be an integral part of helping those who grieve. Recognising and celebrating the legacies of those who have died is considered far more effective than ignoring, as previous generations have done, the fact that someone had ever existed and this was borne out when our local hospice, St Gemmas, established a Tree Of Life on to which bereaved relatives could hang copper leaves inscribed with the name of a loved one who had died.

So with all this is mind The Copper Tree took shape and in the story the children are gently taken through the difficult process. There are light hearted moments and moments of poignancy – just as in life - and following a period of reflection after the death of Miss Evans, they are encouraged to think about all that their teacher has shared with them - or taught them. These memories are then inscribed on to copper leaves and fixed on to a copper tree as a reminder of her lasting legacy.

We cherish our memories of Caroline and we are proud of the legacies she has left. The Copper Tree, may not have happened had it not been for her and that, in itself, remains a lasting legacy to her. We recognise also that, while at times the emotional pain has been difficult to bear, we have, as Caroline did in the end, found some measure of peace.

_____________________________________________________

The Copper Tree by Hilary Robinson,

The Copper Tree by Hilary Robinson, illustrated by Mandy StanleyPublished by Strauss House Productions

ISBN: 978-0957124509

www.thecoppertree.org

Our Guest Blogger, Hilary Robinson,

has written over forty illustrated

children's books.

You can find out more at http://www.hilaryrobinson.co.uk/

Published on October 31, 2012 01:00

October 25, 2012

From start to finish – the making of The Fairytale Hairdresser and Cinderella by Abie Longstaff

Want to know what really happens behind the pages of a book?

Here’s a sneaky look at how my latest picture book took shape.

The Idea

The idea for the Fairytale Hairdresser series came about through my sisters. I am one of six girls and we used to play all kinds of crazy games (often involving dressing up the poor long-suffering dog). One of our favourite games was hairdressers and we had our own little salon going on in the family bathroom. I was reminiscing about the sinkfuls of bubbles with my sisters one day when a thought popped into my head: where do fairy tale characters go to get their hair done? I immediately thought of the Big Bad Wolf having his whiskers washed, and a series was born!

The Plot

Cinderella is the second in the series (the first focused on Rapunzel). Writing within a series is both easier and harder. It’s easier because you already have the set-up and characters – my main character, Kittie Lacey is a modern business woman who runs a salon caring for all the hair, beards, fur and fleece in Fairyland. I had a feel of how Kittie came across, and the template of her helping a fairy tale character to work with. But in series writing you have to make sure you develop your story on, and that the book fits well within past as well as future books. You do also feel the pressure of making sure the second book is as popular as the first.

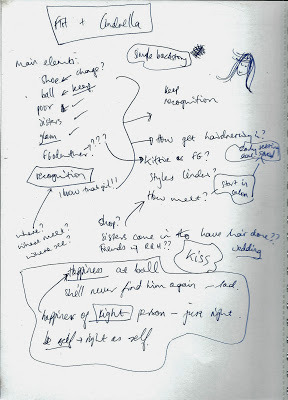

The first thing I do with a Fairytale Hairdresser book is to work out which elements of the story I want to keep, which I want to adapt and which I want to ditch. To find which bits of the story resonate the most I ask around for advice - in the case of Cinderella, my children, my nephew and niece and friends' children told me they loved the dressing up and the ball scene and the hunt for Cinderella. Here is my plot scribble for Cinderella:

The challenge for me was to tie the story in with hair. My main character had to get in somehow. So, after much playing, I decided to give Cinderella a day job at the salon, and to use the device of a glass hairclip instead of a shoe to help the Prince find her.

The First Draft

Like a lot of authors, I only write part time. I have a day job and children, so drafts are often scribbled on the tube, at school pick-ups or in my lunch hour at work. I carry a teeny notebook around with me all the time so I can write down the truly brilliant ideas (it’s a very teeny notebook).

The first draft was dashed out as usual on the work commute:

Although I don’t illustrate, I always sketch out spreads in thumbnails – these help me get a feel for pacing, suspense, page turns and word count. So, after my teeny notebook stage, I draw thumbnails of the story in a bigger sketchbook like this:

Then I write and rewrite and write and rewrite, carrying my draft back and forth to my day job so I can scribble on it:

The Editor

The EditorWhen I have a draft I am happy with I send it off to my fantastic editor (I love him). He writes back with comments on my draft like this:

My draft:

'It was getting later and later. The moon was high in the sky.(Moon with cow jumping over.)

Upstairs Kittie and Cinderella were pinning up the Queen’s fallen curls.

Now it was nearly midnight.

Downstairs every maiden wanted to dance with the Prince…

…and he was kept especially busy by the Wicked Step-Sisters, who grabbed him again and again and twirled him around till he was dizzy.'

Editor comments:

'I really love the upstairs/downstairs section, and I think Lauren will have great fun with this – it will make a really striking spread. I wonder, though, whether we could lose the lines ‘...and he was kept especially busy by the Wicked Step-Sisters, who grabbed him again and again...’, as it could be shown in the illustration. It rather breaks up the: upstairs..., downstairs..., upstairs..., downstairs... Likewise the ‘it was getting later and later’, ‘now it was almost midnight’. The time progression would be implicit in all the activity, and we could try using little clocks showing the hour getting later and later'

The real illustrator

Once a next stage draft is agreed, the book goes off to my amazing illustrator, Lauren Beard, to work her magic. The spread above was turned into this rough:

Are there arguments?

A lot of people want to know the answer to this. The truth is – there are disagreements occasionally about what a story should include. It’s part of the process. But it's hard as a new writer to know whether to stand your ground. The publishers usually know what they are talking about much more than I do and so I mainly trust my editor (annoyingly he is most often right). But, if there is something I think is really important I will try and push my point.

In Cinderella one particular issue arose. I wanted the Prince to have met Cinderella before the ball and for him to look for her at the ball. But this was a departure from the original story where the Prince has to look for her after the ball, using the glass slipper.

So I wrote to my editor and said:Me:'I wanted to do a twist on the Cinderella story as I don't like the way in the original tale the implication is that Cinders needs to dress up and look beautiful to win her Prince, so much so that the Ugly sisters do not recognise her when she looks so lovely at the ball. This theme of being unrecognisable is continued in the rest of the tale, as the Prince needs to find the girl who fits the shoe, which implies that, even though he has danced with her, he would not recognise her in her rags. I don't really like this message for modern girls and I wanted to get away from this, so put the hunting for Cinders into the ball scene, instead of having it after the ball.'

He wrote back:Editor:'Now that I see how important that moment is for you I wouldn’t suggest deleting it. I do think it’s a great moment, and it really drives home the point that he’s not interested in her for her fancy clothes. It sets up some lovely tension early on, too. The believability of the recognition, or lack of, part of the original story has always bothered me, so I feel happy to do away with it. And I do like your solution of the Where’s Wally scene that will give kids something to spot and also link back to the glass slipper element of the original.'

We ended up with this:

The Fairytale Hairdresser and Cinderella is out his month and I love the final version!

Now I just have to get on with plotting book 3, The Fairytale Hairdresser and Sleeping Beauty.

Published on October 25, 2012 23:51

October 21, 2012

What motivates your characters? by Natascha Biebow (Guest Blogger)

Hmmm, see this cake?

Yes, you know you WANT it.

Why?

Well, it’s delicious and chocolaty and will make writing and illustrating go much more speedily, won’t it?

But do you NEED it?!?

An author recently sent me a story about a bunny character who wants something. “Bunny wants more blerks,” she told me. “But why?” I asked. Author: “Because Bunny’s family hasn’t had blerks much and blerks are good.” Me: “But why are blerks better and why aren’t the other things Bunny’s family had before good enough? . . . Why does Bunny NEED a blerk?”Author: “Well, um, I’m not sure . . .”

Time for some brainstorming about character motivation.

When I read stories that don’t work, it’s usually because the character’s needs and wants aren’t clear enough, so that when I finish reading the story, I find myself asking, “So what?” This is because I am not taken on the emotional journey that the writer thinks she is taking me on.

For example, another author once sent me a story about a boy who sets off to see the world. He meets all kinds of fantastical creatures, including a one-eyed Irk. Then he meets a kind of octopus monster that nearly eats him up. The Irk (who happens to be nearby) saves him in the nick of time and they go back home.

It’s a perfectly good story with a beginning, middle and end, but what I want to know is WHY did he go on this journey. When the boy gets home, what has he achieved? Yes, he’s met some extraordinary creatures, but so what? What is on the page is a series of discoveries put into a loose sequence, but no real narrative tension or resolution. So, the reader is left feeling a little unsure about what the book is really about and what has been resolved. This story is missing a clearer sense that, as a result of his adventures, the main character has grown and changed, or helped another creature or saved the day in some way, or discovered something extraordinary and useful for all of us, or something that explains why all these fantastical creatures are how they are …

When thinking about motivation, writers need to ask themselves some key questions about their characters in order to figure out the story:

What does your character:

WANT? NEED?FEAR?LOVE?

. . . Then, dig deeper and ask, “Why?” each time.

You can also think about what your character wears, likes to eat, does all day, etc., but these are all back-story that, in the case of picture books, may not necessarily be essential. But, the more well-rounded the character is in the your head, the more alive it will be for young readers.

The answers to these questions don’t necessarily need to feature in the text, but they do inform the internal logic of the story.

More often than not, once I start asking these questions, the author really does know what motivates her character. But, she hasn’t incorporated this into the book.

To get to the bottom of motivation, writers have to know WHY their character does things.

Why?

If you know why a character behaves in a certain way or what makes them tick, then you are addressing what the character NEEDS. What your character needs informs the emotional plot of your story. The result is a book that carries emotional weight, that so-called ‘aw’ factor that you hear editors bandying about. If you have a book that only has an action plot – what your character WANTS – what you have is a list of actions (like the example above) and the result is a flat story, where the reader doesn’t necessarily want to re-read the book again, because he’s asking ‘so what?’

Also, if you dig deep to find out your character’s motivation, you will make them multi-layered, like real people, and therefore believable. Readers need to know what floats your main character’s boat, what makes him jump out of bed each morning (or not).

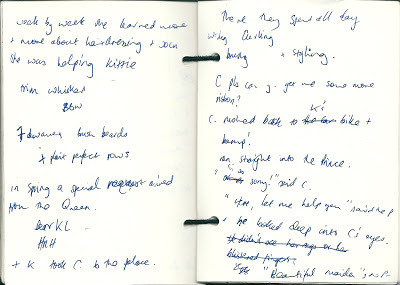

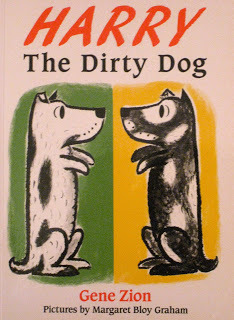

So, for instance, in Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion:

Harry WANTS to avoid taking a bath – he even fears it a bit perhaps, I suspect. This leads to the action plot where he goes off exploring and getting dirty. But, what he discovers through the course of his adventures, is that what he really NEEDS is to be loved by his family, and that means taking a bath . . .

Here are some other examples of characters that have clear motivation:

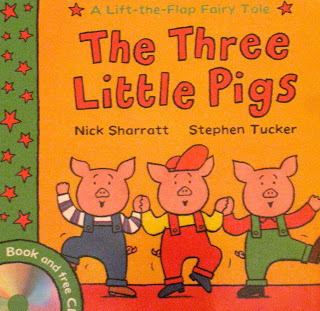

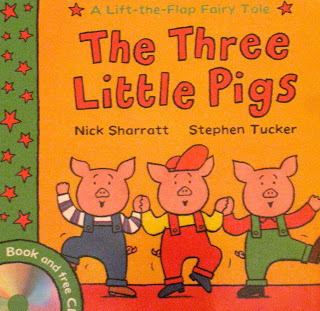

The 3 Little Pigs need . . .

. . . to find a new home. Why? To survive the wolf!

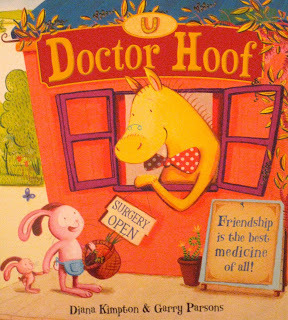

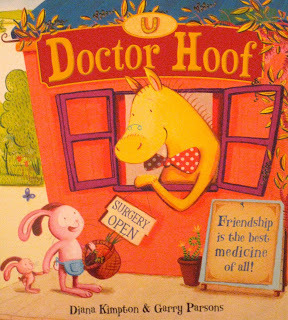

Dr Hoof needs...

to help people. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Diana Kimpton

Because helping people makes him feel good inside (plus he’s a doctor!).

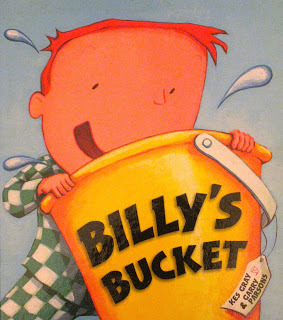

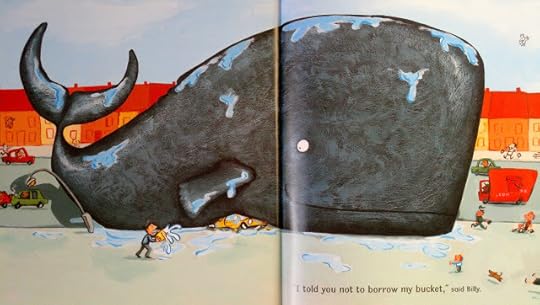

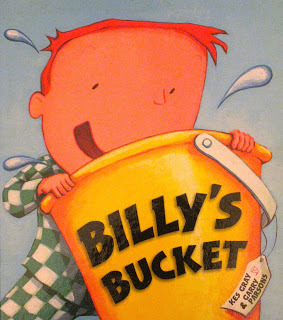

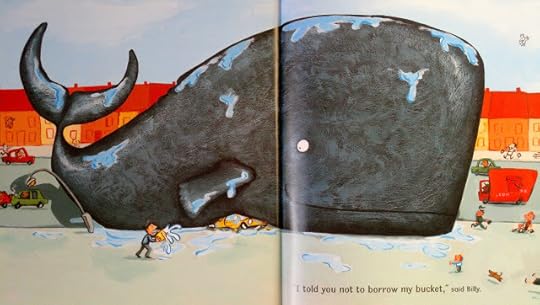

Billy needs . . .

his parents to listen to him when he tells them there are sea creatures living in his bucket. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

Because if they don’t, he won’t feel valued, plus the sea creatures in his bucket may be endangered.

These motivations lead to ACTION.

If you know your character’s motivation, you can up the ante. You can increase the conflict in your story by putting your character into a situation where his motivation is challenged – his buttons are pushed and you put him under stress.

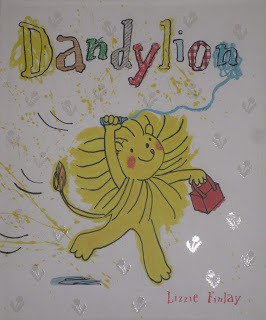

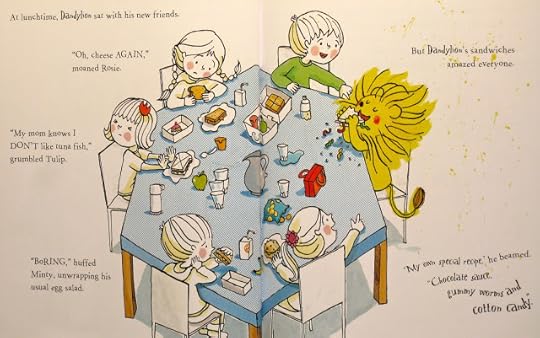

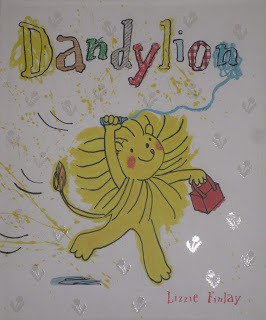

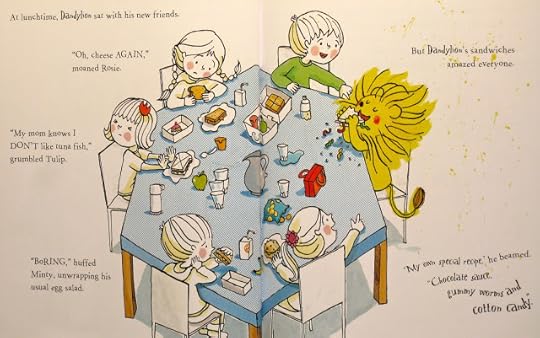

For instance, in DANDYLION by Lizzie Finlay:

Dandylion is a sunny, exuberant character, who is motivated by a sense of fun and is completely uninhibited. He wants to have a good time at school, and is so unselfconscious that he doesn’t notice he’s different.

© Lizzie Finlay

The turning point in the story comes when the other children tell him that he is too different, like a weed.

© Lizzie Finlay

All of a sudden, Dandylion’s motivation is challenged. He doesn’t know what is right. Should he conform, or should he forge ahead with being different?

To come out of his muddle, he must first suffer and wrestle with this moral dilemma.

© Lizzie Finlay

The emotional plot leads him to change internally and develop emotionally as a result of external action.

© Lizzie Finlay

This is what gives the happy ending weight and takes readers on a satisfyingjourney.

So, talk to your characters and find out what reallymotivates them. And maybe offer them a piece of cake.

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentorwww.blueelephantstoryshaping.comBlue Elephant Storyshaping is a coaching service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Yes, you know you WANT it.

Why?

Well, it’s delicious and chocolaty and will make writing and illustrating go much more speedily, won’t it?

But do you NEED it?!?

An author recently sent me a story about a bunny character who wants something. “Bunny wants more blerks,” she told me. “But why?” I asked. Author: “Because Bunny’s family hasn’t had blerks much and blerks are good.” Me: “But why are blerks better and why aren’t the other things Bunny’s family had before good enough? . . . Why does Bunny NEED a blerk?”Author: “Well, um, I’m not sure . . .”

Time for some brainstorming about character motivation.

When I read stories that don’t work, it’s usually because the character’s needs and wants aren’t clear enough, so that when I finish reading the story, I find myself asking, “So what?” This is because I am not taken on the emotional journey that the writer thinks she is taking me on.

For example, another author once sent me a story about a boy who sets off to see the world. He meets all kinds of fantastical creatures, including a one-eyed Irk. Then he meets a kind of octopus monster that nearly eats him up. The Irk (who happens to be nearby) saves him in the nick of time and they go back home.

It’s a perfectly good story with a beginning, middle and end, but what I want to know is WHY did he go on this journey. When the boy gets home, what has he achieved? Yes, he’s met some extraordinary creatures, but so what? What is on the page is a series of discoveries put into a loose sequence, but no real narrative tension or resolution. So, the reader is left feeling a little unsure about what the book is really about and what has been resolved. This story is missing a clearer sense that, as a result of his adventures, the main character has grown and changed, or helped another creature or saved the day in some way, or discovered something extraordinary and useful for all of us, or something that explains why all these fantastical creatures are how they are …

When thinking about motivation, writers need to ask themselves some key questions about their characters in order to figure out the story:

What does your character:

WANT? NEED?FEAR?LOVE?

. . . Then, dig deeper and ask, “Why?” each time.

You can also think about what your character wears, likes to eat, does all day, etc., but these are all back-story that, in the case of picture books, may not necessarily be essential. But, the more well-rounded the character is in the your head, the more alive it will be for young readers.

The answers to these questions don’t necessarily need to feature in the text, but they do inform the internal logic of the story.

More often than not, once I start asking these questions, the author really does know what motivates her character. But, she hasn’t incorporated this into the book.

To get to the bottom of motivation, writers have to know WHY their character does things.

Why?

If you know why a character behaves in a certain way or what makes them tick, then you are addressing what the character NEEDS. What your character needs informs the emotional plot of your story. The result is a book that carries emotional weight, that so-called ‘aw’ factor that you hear editors bandying about. If you have a book that only has an action plot – what your character WANTS – what you have is a list of actions (like the example above) and the result is a flat story, where the reader doesn’t necessarily want to re-read the book again, because he’s asking ‘so what?’

Also, if you dig deep to find out your character’s motivation, you will make them multi-layered, like real people, and therefore believable. Readers need to know what floats your main character’s boat, what makes him jump out of bed each morning (or not).

So, for instance, in Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion:

Harry WANTS to avoid taking a bath – he even fears it a bit perhaps, I suspect. This leads to the action plot where he goes off exploring and getting dirty. But, what he discovers through the course of his adventures, is that what he really NEEDS is to be loved by his family, and that means taking a bath . . .

Here are some other examples of characters that have clear motivation:

The 3 Little Pigs need . . .

. . . to find a new home. Why? To survive the wolf!

Dr Hoof needs...

to help people. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Diana Kimpton

Because helping people makes him feel good inside (plus he’s a doctor!).

Billy needs . . .

his parents to listen to him when he tells them there are sea creatures living in his bucket. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray © Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes GrayBecause if they don’t, he won’t feel valued, plus the sea creatures in his bucket may be endangered.

These motivations lead to ACTION.

If you know your character’s motivation, you can up the ante. You can increase the conflict in your story by putting your character into a situation where his motivation is challenged – his buttons are pushed and you put him under stress.

For instance, in DANDYLION by Lizzie Finlay:

Dandylion is a sunny, exuberant character, who is motivated by a sense of fun and is completely uninhibited. He wants to have a good time at school, and is so unselfconscious that he doesn’t notice he’s different.

© Lizzie Finlay

The turning point in the story comes when the other children tell him that he is too different, like a weed.

© Lizzie Finlay

All of a sudden, Dandylion’s motivation is challenged. He doesn’t know what is right. Should he conform, or should he forge ahead with being different?

To come out of his muddle, he must first suffer and wrestle with this moral dilemma.

© Lizzie Finlay

The emotional plot leads him to change internally and develop emotionally as a result of external action.

© Lizzie Finlay

This is what gives the happy ending weight and takes readers on a satisfyingjourney.

So, talk to your characters and find out what reallymotivates them. And maybe offer them a piece of cake.

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentorwww.blueelephantstoryshaping.comBlue Elephant Storyshaping is a coaching service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Published on October 21, 2012 00:00

October 15, 2012

Saying "Boo!" To Scary Things, by Pippa Goodhart

With Halloween just around the corner, and following on from Paeony’s post about picture books needing comforting endings, I thought I’d look at the way that picture books can de-scarify some of the terrors of young childhood.

We all know that stories have the power to scare. They scare us all through our lives, sometimes enjoyably, sometimes to teach us lessons, sometimes to bully us. But stories can also have the power to disarm the things that terrify us; to comfort us, and to adjust the power balance back in our favour.

The trick to disarming the scary is, I think, to make the scary thing very clearly fictional, and also funny.That way we know that the monster under the stairs or in the woods isn’t a real threat, but we can still enjoy a frisson of pretend terror.

Think of those ‘terrible’and ‘wild’ monsters, the Gruffalo and the Wild Things. They are big. They have claws and horns and all sorts. But they are also goofy, and children know very well that they are never going to be a real threat. You don’t get cuddly toys made from something that’s truly scary!Those monsters represent the fears in our real lives, and those real fears come in all sorts of different forms, brought about by personal circumstances and personalities. Facing the bully in the playground, facing the dark, facing our own limitations, and so on. Using monsters or ghosts to represent those fears leaves our interpretation of them open, to suit us all, as well as putting the issue at a comforting remove. How much more limited in therapeutic use would be a book that looked at a real child facing real fears about going up the stairs in the dark. And, besides, it wouldn’t be half as much fun!

The story arc to most scary picture book stories is simply one of building up tension and anticipation of a major scare, only to diffuse it in a funny way at the end.

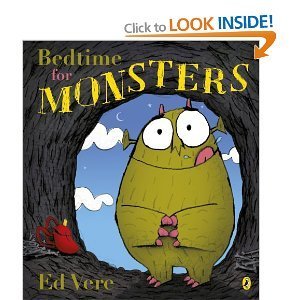

I love Ed Vere’s Bedtime For Monsters. A monster (again with claws and horns, and licking his lips) is looking for a bedtime snack, and it seems as though that snack just might be YOU! The monster is coming closer and closer, his tummy rumbling louder and louder, and …. Actually all he wants is a goodnight kiss!

I love Ed Vere’s Bedtime For Monsters. A monster (again with claws and horns, and licking his lips) is looking for a bedtime snack, and it seems as though that snack just might be YOU! The monster is coming closer and closer, his tummy rumbling louder and louder, and …. Actually all he wants is a goodnight kiss!

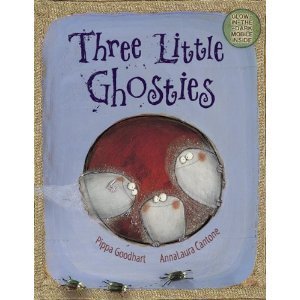

On a more Halloweeny front, my Three Little Ghosties don’t look terribly scary, but the three of them work as a pack, as bullies so often do. They boast about how they’ve bullied some ghoulses sitting in schoolsies learning spelling rulsies, and also some witches, sitting in ditches, lipsticking their lipses, and then an ogre as big as six treeses, sitting in the forest, picking at his fleases. Each of them boasts about the way they’ve sent these other traditionally scary characters running. Children start the book almost as part of the ghosty gang, enjoying the way the witches and ghouls and ogre are made to look silly when they’re scared. Children join-in with the predictable BOO that sends each victim off in terror. But then the ghosties turn their attention to scaring a child, possibly YOU! And suddenly the creeping and whispering and creeping is coming our way. Through the night the ghosties come closer and closer, in through the windows and into the bedroom … but this time the BOO comes from the child, and it’s the three little ghosties who are now the ones fleeing in terror, sucking their thumbsies and looking silly. We see them scolded by their mumsies who send them home to bed; no longer remotely scary.

On a more Halloweeny front, my Three Little Ghosties don’t look terribly scary, but the three of them work as a pack, as bullies so often do. They boast about how they’ve bullied some ghoulses sitting in schoolsies learning spelling rulsies, and also some witches, sitting in ditches, lipsticking their lipses, and then an ogre as big as six treeses, sitting in the forest, picking at his fleases. Each of them boasts about the way they’ve sent these other traditionally scary characters running. Children start the book almost as part of the ghosty gang, enjoying the way the witches and ghouls and ogre are made to look silly when they’re scared. Children join-in with the predictable BOO that sends each victim off in terror. But then the ghosties turn their attention to scaring a child, possibly YOU! And suddenly the creeping and whispering and creeping is coming our way. Through the night the ghosties come closer and closer, in through the windows and into the bedroom … but this time the BOO comes from the child, and it’s the three little ghosties who are now the ones fleeing in terror, sucking their thumbsies and looking silly. We see them scolded by their mumsies who send them home to bed; no longer remotely scary.

So enjoy Halloween by using the scary to comfort!

We all know that stories have the power to scare. They scare us all through our lives, sometimes enjoyably, sometimes to teach us lessons, sometimes to bully us. But stories can also have the power to disarm the things that terrify us; to comfort us, and to adjust the power balance back in our favour.

The trick to disarming the scary is, I think, to make the scary thing very clearly fictional, and also funny.That way we know that the monster under the stairs or in the woods isn’t a real threat, but we can still enjoy a frisson of pretend terror.

Think of those ‘terrible’and ‘wild’ monsters, the Gruffalo and the Wild Things. They are big. They have claws and horns and all sorts. But they are also goofy, and children know very well that they are never going to be a real threat. You don’t get cuddly toys made from something that’s truly scary!Those monsters represent the fears in our real lives, and those real fears come in all sorts of different forms, brought about by personal circumstances and personalities. Facing the bully in the playground, facing the dark, facing our own limitations, and so on. Using monsters or ghosts to represent those fears leaves our interpretation of them open, to suit us all, as well as putting the issue at a comforting remove. How much more limited in therapeutic use would be a book that looked at a real child facing real fears about going up the stairs in the dark. And, besides, it wouldn’t be half as much fun!

The story arc to most scary picture book stories is simply one of building up tension and anticipation of a major scare, only to diffuse it in a funny way at the end.

I love Ed Vere’s Bedtime For Monsters. A monster (again with claws and horns, and licking his lips) is looking for a bedtime snack, and it seems as though that snack just might be YOU! The monster is coming closer and closer, his tummy rumbling louder and louder, and …. Actually all he wants is a goodnight kiss!

I love Ed Vere’s Bedtime For Monsters. A monster (again with claws and horns, and licking his lips) is looking for a bedtime snack, and it seems as though that snack just might be YOU! The monster is coming closer and closer, his tummy rumbling louder and louder, and …. Actually all he wants is a goodnight kiss!  On a more Halloweeny front, my Three Little Ghosties don’t look terribly scary, but the three of them work as a pack, as bullies so often do. They boast about how they’ve bullied some ghoulses sitting in schoolsies learning spelling rulsies, and also some witches, sitting in ditches, lipsticking their lipses, and then an ogre as big as six treeses, sitting in the forest, picking at his fleases. Each of them boasts about the way they’ve sent these other traditionally scary characters running. Children start the book almost as part of the ghosty gang, enjoying the way the witches and ghouls and ogre are made to look silly when they’re scared. Children join-in with the predictable BOO that sends each victim off in terror. But then the ghosties turn their attention to scaring a child, possibly YOU! And suddenly the creeping and whispering and creeping is coming our way. Through the night the ghosties come closer and closer, in through the windows and into the bedroom … but this time the BOO comes from the child, and it’s the three little ghosties who are now the ones fleeing in terror, sucking their thumbsies and looking silly. We see them scolded by their mumsies who send them home to bed; no longer remotely scary.

On a more Halloweeny front, my Three Little Ghosties don’t look terribly scary, but the three of them work as a pack, as bullies so often do. They boast about how they’ve bullied some ghoulses sitting in schoolsies learning spelling rulsies, and also some witches, sitting in ditches, lipsticking their lipses, and then an ogre as big as six treeses, sitting in the forest, picking at his fleases. Each of them boasts about the way they’ve sent these other traditionally scary characters running. Children start the book almost as part of the ghosty gang, enjoying the way the witches and ghouls and ogre are made to look silly when they’re scared. Children join-in with the predictable BOO that sends each victim off in terror. But then the ghosties turn their attention to scaring a child, possibly YOU! And suddenly the creeping and whispering and creeping is coming our way. Through the night the ghosties come closer and closer, in through the windows and into the bedroom … but this time the BOO comes from the child, and it’s the three little ghosties who are now the ones fleeing in terror, sucking their thumbsies and looking silly. We see them scolded by their mumsies who send them home to bed; no longer remotely scary. So enjoy Halloween by using the scary to comfort!

Published on October 15, 2012 17:00

October 11, 2012

The End by Paeony Lewis

It was a cute kitten video clip (just 28 seconds) that got me thinking about the endings in picture books. I watched it and thought, hey, that’s a perfect picture book ending . And I challenge you not to squeal, ‘Ahhh…’! Click here for the YouTube link.

Long ago, I remember an editor asking me to add more of an ‘Ahhh…’ ending to a picture book (using that exact phrase – and I think it’s a good one). I suspect we all know picture books that make us go ‘Ahhh…’ When my children were small, as a mum I’d choke up when I read the last line of Martin Waddell’s Owl Babies: “I love my mummy,” said Bill. I've heard it took the author a long time to come up with that line, but it was worth it (in the context of the story). An ‘Ahhh…’ emotion resonates with the adult reader.

Excerpt from final page,

Excerpt from final page,

Big Bear, Little Bear by David Bedford,

illus by Jane Chapman (Little Tiger Press)

For the child who listens to the picture book, perhaps it’s not so much an ‘Ahhh…’ as a comforting reassurance that all is right with the world. Most young children need that before they go to sleep. Here’s a perfect goodnight “Ahhh…” image from the end of Big Bear, Little Bear(and it reminds me of the kitten video).

Of course, no ending will save a below-average book. However, a good story won’t work if the ending isn't right. Sometimes an author will know the ending before anything else has been written. Sadly, sometimes we haven’t a clue how it will end and we scratch our heads for days, weeks and months (and no, it’s not because we have nits!).

Paeony Lewis, practising

Paeony Lewis, practising

scratching at a young age (no nits)A picture book is read many times, so the ending is heard many times. This means it has to satisfy again and again, even though the adult and child know the story. So a trick, clever ending that relies solely on being a surprise won’t be enough, unless it’s a satisfying surprise that can be enjoyed night after night.

When I first wrote Hurry Up, Birthday,I thought the ending should be the birthday. After all, the entire story had been building up to this. A couple of editors suggested adding something extra to the end, but at first I wasn't convinced. Off and on, I thought about this for months and then out of the blue it came to me.

When I first wrote Hurry Up, Birthday,I thought the ending should be the birthday. After all, the entire story had been building up to this. A couple of editors suggested adding something extra to the end, but at first I wasn't convinced. Off and on, I thought about this for months and then out of the blue it came to me.

The story was about an excited bunny who bounced extra fast in an attempt to hurry time and make his birthday arrive quicker. So, when his birthday finally arrived, why not turn things around? Therefore, on the final page I had the bunny bouncing slowly because he didn't want to hurry his birthday. That might sound obvious and simple (as so much does in picture books), but it took me a long time to come up with that ending. Far too long!

Adding a little twist to an ending is popular in picture books. It makes the story fun and is less predictable (especially when it’s obvious that everything will turn out fine). Twists make us smile at the surprise or encourage a discussion about the story. At the end of my No More Yawning, the little girl finally falls asleep (after too much yawning), but then she’s woken by Mum’s loud yawn. That’s a little twist, and it also makes gentle fun of the naughty mum (children grin when they come out on top – not adults!).

Adding a little twist to an ending is popular in picture books. It makes the story fun and is less predictable (especially when it’s obvious that everything will turn out fine). Twists make us smile at the surprise or encourage a discussion about the story. At the end of my No More Yawning, the little girl finally falls asleep (after too much yawning), but then she’s woken by Mum’s loud yawn. That’s a little twist, and it also makes gentle fun of the naughty mum (children grin when they come out on top – not adults!).

Occasionally the twist is just a question, encouraging parent and child to interact.

Occasionally the twist is just a question, encouraging parent and child to interact.

Who Do You Love? by Mandy Stanley is a good example. All the way through the book we discover who the animals love, and then on the last page the question is directed at the reader.

Excerpt from final page,

Excerpt from final page,

Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus

by Mo Williems (Walker Books)Picture book endings aren't only about clever ideas and twists. We have to think about the emotional needs of the child who’ll be listening to the story. Most picture books are read at bedtime, so almost all are reassuring and end happily with a satisfying resolution (remember the cute kitten video). In Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus, although the pigeon is thwarted and isn't allowed to drive the bus (phew!), his disappointment is tempered with hope. He spots a truck and on the last page we see him imagining a pigeon driving a truck. Hope is a powerful and positive emotion. Plus the story comes full circle and once more the pigeon dreams of driving a vehicle.

Driving buses is one of the many things a child can’t do and it frustrates them. Adults are always taking control. Therefore in picture books it should be the child character that solves the ‘problem’ in the story (sometimes with a little help). Adults shouldn't just take over and solve the problem for the child. As in real life, a child will have to learn to overcome difficulties. Plus it’s more satisfying for the child to see another child work things out (or even get one up over the adults). In The Gruffalo, the mouse (the child?) foils all the big threatening animals (the adults?) and finally gets to eats his nuts, rather than let himself be the snack.

Driving buses is one of the many things a child can’t do and it frustrates them. Adults are always taking control. Therefore in picture books it should be the child character that solves the ‘problem’ in the story (sometimes with a little help). Adults shouldn't just take over and solve the problem for the child. As in real life, a child will have to learn to overcome difficulties. Plus it’s more satisfying for the child to see another child work things out (or even get one up over the adults). In The Gruffalo, the mouse (the child?) foils all the big threatening animals (the adults?) and finally gets to eats his nuts, rather than let himself be the snack.

Even if the child solves the problem, that doesn't mean the adult reader is ignored. An ending can be on more than one level, so it’s enjoyed by the child whilst including something extra for the adult. All parents will relate to the ending of Jill Murphy’s classic, Five Minutes’ Peace, whilst a child will just see it as funny. Mummy elephant finally gets some peace: “And off she went downstairs, where she had three minutes and forty-five seconds of peace before they all came to join her.”

Even if the child solves the problem, that doesn't mean the adult reader is ignored. An ending can be on more than one level, so it’s enjoyed by the child whilst including something extra for the adult. All parents will relate to the ending of Jill Murphy’s classic, Five Minutes’ Peace, whilst a child will just see it as funny. Mummy elephant finally gets some peace: “And off she went downstairs, where she had three minutes and forty-five seconds of peace before they all came to join her.”

Jane Clarke’s Gilbert the Great is another story that may be read on several levels. To a child, the book is about a friend leaving and a new friendship. To an adult it’s about death and new beginnings. Plus at the very end is a lovely little joke that an adult can explain, or simply enjoy. Illustrated by Charles Fuge, it’s the perfect image to end this blog.

The End.

_______________________________________

Paeony Lewis is a children's author and writing tutor. www.paeonylewis.com

Long ago, I remember an editor asking me to add more of an ‘Ahhh…’ ending to a picture book (using that exact phrase – and I think it’s a good one). I suspect we all know picture books that make us go ‘Ahhh…’ When my children were small, as a mum I’d choke up when I read the last line of Martin Waddell’s Owl Babies: “I love my mummy,” said Bill. I've heard it took the author a long time to come up with that line, but it was worth it (in the context of the story). An ‘Ahhh…’ emotion resonates with the adult reader.

Excerpt from final page,

Excerpt from final page,Big Bear, Little Bear by David Bedford,

illus by Jane Chapman (Little Tiger Press)

For the child who listens to the picture book, perhaps it’s not so much an ‘Ahhh…’ as a comforting reassurance that all is right with the world. Most young children need that before they go to sleep. Here’s a perfect goodnight “Ahhh…” image from the end of Big Bear, Little Bear(and it reminds me of the kitten video).

Of course, no ending will save a below-average book. However, a good story won’t work if the ending isn't right. Sometimes an author will know the ending before anything else has been written. Sadly, sometimes we haven’t a clue how it will end and we scratch our heads for days, weeks and months (and no, it’s not because we have nits!).

Paeony Lewis, practising

Paeony Lewis, practisingscratching at a young age (no nits)A picture book is read many times, so the ending is heard many times. This means it has to satisfy again and again, even though the adult and child know the story. So a trick, clever ending that relies solely on being a surprise won’t be enough, unless it’s a satisfying surprise that can be enjoyed night after night.

When I first wrote Hurry Up, Birthday,I thought the ending should be the birthday. After all, the entire story had been building up to this. A couple of editors suggested adding something extra to the end, but at first I wasn't convinced. Off and on, I thought about this for months and then out of the blue it came to me.

When I first wrote Hurry Up, Birthday,I thought the ending should be the birthday. After all, the entire story had been building up to this. A couple of editors suggested adding something extra to the end, but at first I wasn't convinced. Off and on, I thought about this for months and then out of the blue it came to me. The story was about an excited bunny who bounced extra fast in an attempt to hurry time and make his birthday arrive quicker. So, when his birthday finally arrived, why not turn things around? Therefore, on the final page I had the bunny bouncing slowly because he didn't want to hurry his birthday. That might sound obvious and simple (as so much does in picture books), but it took me a long time to come up with that ending. Far too long!

Adding a little twist to an ending is popular in picture books. It makes the story fun and is less predictable (especially when it’s obvious that everything will turn out fine). Twists make us smile at the surprise or encourage a discussion about the story. At the end of my No More Yawning, the little girl finally falls asleep (after too much yawning), but then she’s woken by Mum’s loud yawn. That’s a little twist, and it also makes gentle fun of the naughty mum (children grin when they come out on top – not adults!).

Adding a little twist to an ending is popular in picture books. It makes the story fun and is less predictable (especially when it’s obvious that everything will turn out fine). Twists make us smile at the surprise or encourage a discussion about the story. At the end of my No More Yawning, the little girl finally falls asleep (after too much yawning), but then she’s woken by Mum’s loud yawn. That’s a little twist, and it also makes gentle fun of the naughty mum (children grin when they come out on top – not adults!).

Occasionally the twist is just a question, encouraging parent and child to interact.

Occasionally the twist is just a question, encouraging parent and child to interact. Who Do You Love? by Mandy Stanley is a good example. All the way through the book we discover who the animals love, and then on the last page the question is directed at the reader.

Excerpt from final page,

Excerpt from final page, Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus

by Mo Williems (Walker Books)Picture book endings aren't only about clever ideas and twists. We have to think about the emotional needs of the child who’ll be listening to the story. Most picture books are read at bedtime, so almost all are reassuring and end happily with a satisfying resolution (remember the cute kitten video). In Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus, although the pigeon is thwarted and isn't allowed to drive the bus (phew!), his disappointment is tempered with hope. He spots a truck and on the last page we see him imagining a pigeon driving a truck. Hope is a powerful and positive emotion. Plus the story comes full circle and once more the pigeon dreams of driving a vehicle.

Driving buses is one of the many things a child can’t do and it frustrates them. Adults are always taking control. Therefore in picture books it should be the child character that solves the ‘problem’ in the story (sometimes with a little help). Adults shouldn't just take over and solve the problem for the child. As in real life, a child will have to learn to overcome difficulties. Plus it’s more satisfying for the child to see another child work things out (or even get one up over the adults). In The Gruffalo, the mouse (the child?) foils all the big threatening animals (the adults?) and finally gets to eats his nuts, rather than let himself be the snack.

Driving buses is one of the many things a child can’t do and it frustrates them. Adults are always taking control. Therefore in picture books it should be the child character that solves the ‘problem’ in the story (sometimes with a little help). Adults shouldn't just take over and solve the problem for the child. As in real life, a child will have to learn to overcome difficulties. Plus it’s more satisfying for the child to see another child work things out (or even get one up over the adults). In The Gruffalo, the mouse (the child?) foils all the big threatening animals (the adults?) and finally gets to eats his nuts, rather than let himself be the snack.  Even if the child solves the problem, that doesn't mean the adult reader is ignored. An ending can be on more than one level, so it’s enjoyed by the child whilst including something extra for the adult. All parents will relate to the ending of Jill Murphy’s classic, Five Minutes’ Peace, whilst a child will just see it as funny. Mummy elephant finally gets some peace: “And off she went downstairs, where she had three minutes and forty-five seconds of peace before they all came to join her.”

Even if the child solves the problem, that doesn't mean the adult reader is ignored. An ending can be on more than one level, so it’s enjoyed by the child whilst including something extra for the adult. All parents will relate to the ending of Jill Murphy’s classic, Five Minutes’ Peace, whilst a child will just see it as funny. Mummy elephant finally gets some peace: “And off she went downstairs, where she had three minutes and forty-five seconds of peace before they all came to join her.”Jane Clarke’s Gilbert the Great is another story that may be read on several levels. To a child, the book is about a friend leaving and a new friendship. To an adult it’s about death and new beginnings. Plus at the very end is a lovely little joke that an adult can explain, or simply enjoy. Illustrated by Charles Fuge, it’s the perfect image to end this blog.

The End.

_______________________________________

Paeony Lewis is a children's author and writing tutor. www.paeonylewis.com

Published on October 11, 2012 00:00

October 6, 2012

How do you say it in translation? and a Giveaway.

Children love stories, no matter where in the world they live, but often when I sit at home in Scotland writing a story I have no idea where it might travel to.

Publishers often want to sell co-editions of picture books, that is when they sell the rights to publish them to a publisher in another country.

I was visiting a school in Cairo this year and one of the teachers came to tell me that What Colour is Love? had been a family favourite that he had read over and over again.

I was visiting a school in Cairo this year and one of the teachers came to tell me that What Colour is Love? had been a family favourite that he had read over and over again.A nursery school in New Zealand was using it with their children.

I love it when one of my books gets translated and used abroad. It is interesting to note that if a book is to be translated into another language it is usually the publishers who organise the translation, which is why there is no point, if you are a translator, in approaching an author for work translating their book.

I once discovered some pictures on the internet of a school hall in Brazil. Long sheets of cloth in different colours were suspended from the ceiling, and the teacher was reading my book to a class.

I smiled a lot that day!

I am fascinated to see how the words have been changed in the translation, to make it keep the rhythm or rhyme.

The Brazilian publication -translated into Portuguese- is in its 10th edition with the publishers Brinque-Book.

Since I get copies when it comes out in a new edition I have rather a lot of the Portuguese version Qual e a cor do amor? so I thought I might give some away.

See below for the giveaway details..

Some of my books written for educational publishers have also been translated into other languages, too.

A Ball Called Sam, part of the Rigby Star series (Rigby Literacy in the USA)

has been published by Carroll Education in Ireland

Three other Rigby Star titles have been translated into French for Galaxie. Interestingly they changed a little in translation.

The Giant and the Frippit became Le Geant et Le Korrigan

The Frippit was a made up creature, a mixture of an elf and a squirrel. He became Le Korrigan which the 'Lexique' at the back tells us is ' an elf (Breton)'

Korka the Mighty Elf changed his name and became Luca Le Puissant Lutin

Fizzkid Liz also had a bit of a makeover. In the US version the title is Fizzkid the Inventor.In the Galaxie version her name changed to Beatrice,which I thought suited her French personality really well.

GIVEAWAY

I have two copies of Qual e a cor do amor? and one copy of What Colour is Love? to give away.

If you would like a copy of either please leave a comment and say whether you want the Portuguese or the English version.

The winners will be picked out at random on 28th October 2012

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Website www.lindastrachan.com

Blog BOOKWORDS

Linda Strachan is the award winning author of over 60 books for all ages, from picture books to teen novels, and writing handbook Writing For Children

Published on October 06, 2012 16:46

October 1, 2012

Are Picture Books Value For Money?

Not too long ago, I was in the picture book section of my local book shop, when I overheard a conversation where two people were discussing the cost of picture books. One lady was saying that she didn’t buy picture books anymore, because they were too expensive. She then went on to compare the price of a hardback picture book at £9.99 to an adult novel she was buying, at £7.99.

And perhaps at first glance it can look like you’re getting a rough deal. After all, an adult novel can easily be over 100,000 words. It feels thick and chunky in your hand, something to really get your teeth into. On the other hand, some picture books don’t even get their word count into the hundreds. Some don’t have any words at all. And yet the price points of adult and children’s books are often very similar.

And perhaps at first glance it can look like you’re getting a rough deal. After all, an adult novel can easily be over 100,000 words. It feels thick and chunky in your hand, something to really get your teeth into. On the other hand, some picture books don’t even get their word count into the hundreds. Some don’t have any words at all. And yet the price points of adult and children’s books are often very similar.But they are value for money. They really are. And here’s why.