What motivates your characters? by Natascha Biebow (Guest Blogger)

Hmmm, see this cake?

Yes, you know you WANT it.

Why?

Well, it’s delicious and chocolaty and will make writing and illustrating go much more speedily, won’t it?

But do you NEED it?!?

An author recently sent me a story about a bunny character who wants something. “Bunny wants more blerks,” she told me. “But why?” I asked. Author: “Because Bunny’s family hasn’t had blerks much and blerks are good.” Me: “But why are blerks better and why aren’t the other things Bunny’s family had before good enough? . . . Why does Bunny NEED a blerk?”Author: “Well, um, I’m not sure . . .”

Time for some brainstorming about character motivation.

When I read stories that don’t work, it’s usually because the character’s needs and wants aren’t clear enough, so that when I finish reading the story, I find myself asking, “So what?” This is because I am not taken on the emotional journey that the writer thinks she is taking me on.

For example, another author once sent me a story about a boy who sets off to see the world. He meets all kinds of fantastical creatures, including a one-eyed Irk. Then he meets a kind of octopus monster that nearly eats him up. The Irk (who happens to be nearby) saves him in the nick of time and they go back home.

It’s a perfectly good story with a beginning, middle and end, but what I want to know is WHY did he go on this journey. When the boy gets home, what has he achieved? Yes, he’s met some extraordinary creatures, but so what? What is on the page is a series of discoveries put into a loose sequence, but no real narrative tension or resolution. So, the reader is left feeling a little unsure about what the book is really about and what has been resolved. This story is missing a clearer sense that, as a result of his adventures, the main character has grown and changed, or helped another creature or saved the day in some way, or discovered something extraordinary and useful for all of us, or something that explains why all these fantastical creatures are how they are …

When thinking about motivation, writers need to ask themselves some key questions about their characters in order to figure out the story:

What does your character:

WANT? NEED?FEAR?LOVE?

. . . Then, dig deeper and ask, “Why?” each time.

You can also think about what your character wears, likes to eat, does all day, etc., but these are all back-story that, in the case of picture books, may not necessarily be essential. But, the more well-rounded the character is in the your head, the more alive it will be for young readers.

The answers to these questions don’t necessarily need to feature in the text, but they do inform the internal logic of the story.

More often than not, once I start asking these questions, the author really does know what motivates her character. But, she hasn’t incorporated this into the book.

To get to the bottom of motivation, writers have to know WHY their character does things.

Why?

If you know why a character behaves in a certain way or what makes them tick, then you are addressing what the character NEEDS. What your character needs informs the emotional plot of your story. The result is a book that carries emotional weight, that so-called ‘aw’ factor that you hear editors bandying about. If you have a book that only has an action plot – what your character WANTS – what you have is a list of actions (like the example above) and the result is a flat story, where the reader doesn’t necessarily want to re-read the book again, because he’s asking ‘so what?’

Also, if you dig deep to find out your character’s motivation, you will make them multi-layered, like real people, and therefore believable. Readers need to know what floats your main character’s boat, what makes him jump out of bed each morning (or not).

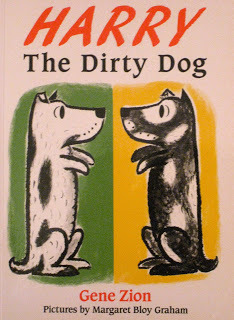

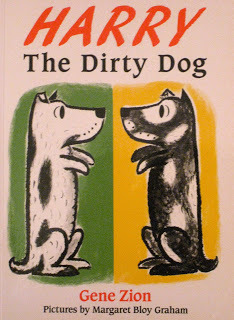

So, for instance, in Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion:

Harry WANTS to avoid taking a bath – he even fears it a bit perhaps, I suspect. This leads to the action plot where he goes off exploring and getting dirty. But, what he discovers through the course of his adventures, is that what he really NEEDS is to be loved by his family, and that means taking a bath . . .

Here are some other examples of characters that have clear motivation:

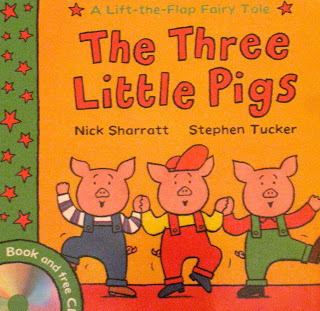

The 3 Little Pigs need . . .

. . . to find a new home. Why? To survive the wolf!

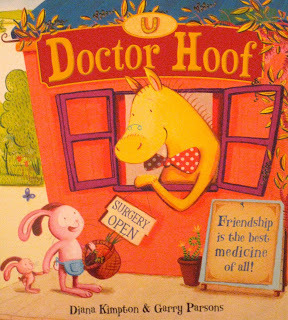

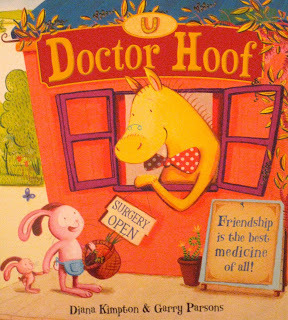

Dr Hoof needs...

to help people. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Diana Kimpton

Because helping people makes him feel good inside (plus he’s a doctor!).

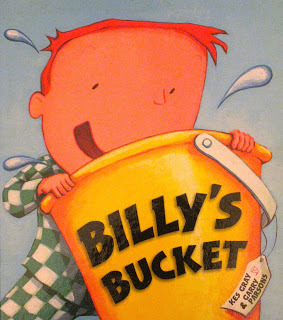

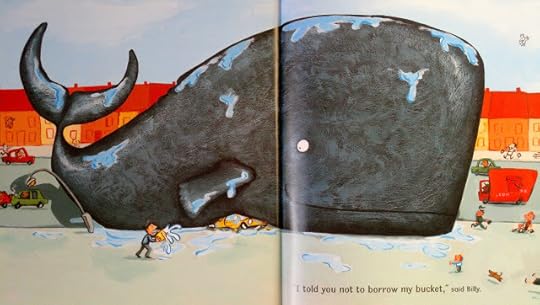

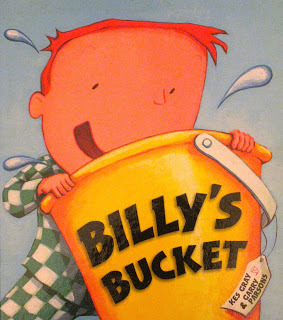

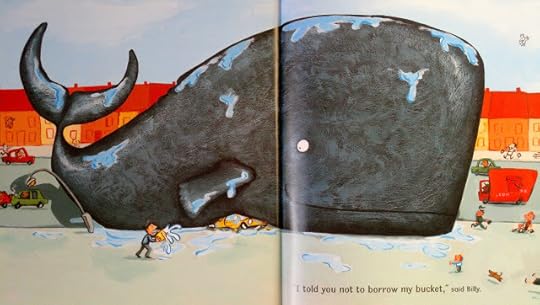

Billy needs . . .

his parents to listen to him when he tells them there are sea creatures living in his bucket. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

Because if they don’t, he won’t feel valued, plus the sea creatures in his bucket may be endangered.

These motivations lead to ACTION.

If you know your character’s motivation, you can up the ante. You can increase the conflict in your story by putting your character into a situation where his motivation is challenged – his buttons are pushed and you put him under stress.

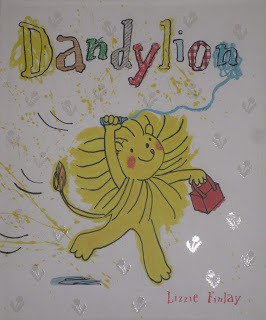

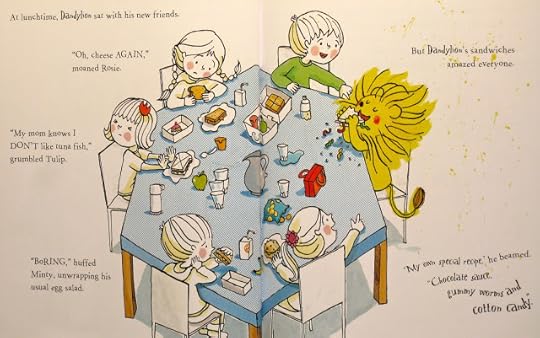

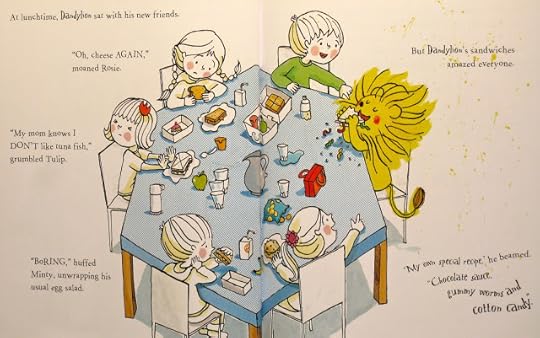

For instance, in DANDYLION by Lizzie Finlay:

Dandylion is a sunny, exuberant character, who is motivated by a sense of fun and is completely uninhibited. He wants to have a good time at school, and is so unselfconscious that he doesn’t notice he’s different.

© Lizzie Finlay

The turning point in the story comes when the other children tell him that he is too different, like a weed.

© Lizzie Finlay

All of a sudden, Dandylion’s motivation is challenged. He doesn’t know what is right. Should he conform, or should he forge ahead with being different?

To come out of his muddle, he must first suffer and wrestle with this moral dilemma.

© Lizzie Finlay

The emotional plot leads him to change internally and develop emotionally as a result of external action.

© Lizzie Finlay

This is what gives the happy ending weight and takes readers on a satisfyingjourney.

So, talk to your characters and find out what reallymotivates them. And maybe offer them a piece of cake.

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentorwww.blueelephantstoryshaping.comBlue Elephant Storyshaping is a coaching service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Yes, you know you WANT it.

Why?

Well, it’s delicious and chocolaty and will make writing and illustrating go much more speedily, won’t it?

But do you NEED it?!?

An author recently sent me a story about a bunny character who wants something. “Bunny wants more blerks,” she told me. “But why?” I asked. Author: “Because Bunny’s family hasn’t had blerks much and blerks are good.” Me: “But why are blerks better and why aren’t the other things Bunny’s family had before good enough? . . . Why does Bunny NEED a blerk?”Author: “Well, um, I’m not sure . . .”

Time for some brainstorming about character motivation.

When I read stories that don’t work, it’s usually because the character’s needs and wants aren’t clear enough, so that when I finish reading the story, I find myself asking, “So what?” This is because I am not taken on the emotional journey that the writer thinks she is taking me on.

For example, another author once sent me a story about a boy who sets off to see the world. He meets all kinds of fantastical creatures, including a one-eyed Irk. Then he meets a kind of octopus monster that nearly eats him up. The Irk (who happens to be nearby) saves him in the nick of time and they go back home.

It’s a perfectly good story with a beginning, middle and end, but what I want to know is WHY did he go on this journey. When the boy gets home, what has he achieved? Yes, he’s met some extraordinary creatures, but so what? What is on the page is a series of discoveries put into a loose sequence, but no real narrative tension or resolution. So, the reader is left feeling a little unsure about what the book is really about and what has been resolved. This story is missing a clearer sense that, as a result of his adventures, the main character has grown and changed, or helped another creature or saved the day in some way, or discovered something extraordinary and useful for all of us, or something that explains why all these fantastical creatures are how they are …

When thinking about motivation, writers need to ask themselves some key questions about their characters in order to figure out the story:

What does your character:

WANT? NEED?FEAR?LOVE?

. . . Then, dig deeper and ask, “Why?” each time.

You can also think about what your character wears, likes to eat, does all day, etc., but these are all back-story that, in the case of picture books, may not necessarily be essential. But, the more well-rounded the character is in the your head, the more alive it will be for young readers.

The answers to these questions don’t necessarily need to feature in the text, but they do inform the internal logic of the story.

More often than not, once I start asking these questions, the author really does know what motivates her character. But, she hasn’t incorporated this into the book.

To get to the bottom of motivation, writers have to know WHY their character does things.

Why?

If you know why a character behaves in a certain way or what makes them tick, then you are addressing what the character NEEDS. What your character needs informs the emotional plot of your story. The result is a book that carries emotional weight, that so-called ‘aw’ factor that you hear editors bandying about. If you have a book that only has an action plot – what your character WANTS – what you have is a list of actions (like the example above) and the result is a flat story, where the reader doesn’t necessarily want to re-read the book again, because he’s asking ‘so what?’

Also, if you dig deep to find out your character’s motivation, you will make them multi-layered, like real people, and therefore believable. Readers need to know what floats your main character’s boat, what makes him jump out of bed each morning (or not).

So, for instance, in Harry the Dirty Dog by Gene Zion:

Harry WANTS to avoid taking a bath – he even fears it a bit perhaps, I suspect. This leads to the action plot where he goes off exploring and getting dirty. But, what he discovers through the course of his adventures, is that what he really NEEDS is to be loved by his family, and that means taking a bath . . .

Here are some other examples of characters that have clear motivation:

The 3 Little Pigs need . . .

. . . to find a new home. Why? To survive the wolf!

Dr Hoof needs...

to help people. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Diana Kimpton

Because helping people makes him feel good inside (plus he’s a doctor!).

Billy needs . . .

his parents to listen to him when he tells them there are sea creatures living in his bucket. Why?

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes Gray © Garry Parsons and Kes Gray

© Garry Parsons and Kes GrayBecause if they don’t, he won’t feel valued, plus the sea creatures in his bucket may be endangered.

These motivations lead to ACTION.

If you know your character’s motivation, you can up the ante. You can increase the conflict in your story by putting your character into a situation where his motivation is challenged – his buttons are pushed and you put him under stress.

For instance, in DANDYLION by Lizzie Finlay:

Dandylion is a sunny, exuberant character, who is motivated by a sense of fun and is completely uninhibited. He wants to have a good time at school, and is so unselfconscious that he doesn’t notice he’s different.

© Lizzie Finlay

The turning point in the story comes when the other children tell him that he is too different, like a weed.

© Lizzie Finlay

All of a sudden, Dandylion’s motivation is challenged. He doesn’t know what is right. Should he conform, or should he forge ahead with being different?

To come out of his muddle, he must first suffer and wrestle with this moral dilemma.

© Lizzie Finlay

The emotional plot leads him to change internally and develop emotionally as a result of external action.

© Lizzie Finlay

This is what gives the happy ending weight and takes readers on a satisfyingjourney.

So, talk to your characters and find out what reallymotivates them. And maybe offer them a piece of cake.

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentorwww.blueelephantstoryshaping.comBlue Elephant Storyshaping is a coaching service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles.

Published on October 21, 2012 00:00

No comments have been added yet.