Writing stories fast and to order. How to avoid doing it badly.

Moira Butterfield

www.moirabutterfield.com

@moiraworld

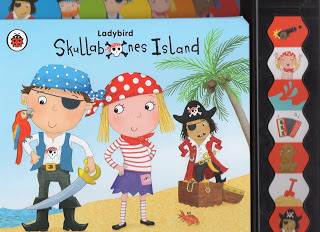

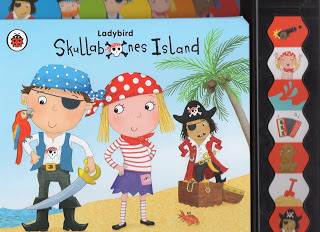

After last week’s detailed description of a one-off picture book’s journey to press, I thought I would write about another much faster type of picture book story-writing. I mean writing to fit a detailed brief for a book that is paper-engineered and could be described as toy-related. Some blog-readers may get the opportunity to do this, and it requires a different way of thinking. Here’s an example. A couple of weeks ago I got an urgent email. Such projects are almost always on a short schedule and if you don’t like working fast, never take them on. Be aware that such projects are fee-based and do not carry royalties, so do not consider the work if this is an issue for you. The project was to write stories for two carousel books. These are books with a story joined to a section that folds around to create a kind of dollshouse scene (I’ll attach a picture showing a carousel book. It’s not mine but it shows the concept). The books I was commissioned to write already had subjects – a princess castle and a tropical fairy garden. The paper-engineered carousel part of the project was already being designed, and the story part of the book was already laid out in sections, with a rough word count. There were four spreads, and there could be no more or less. Added to this, each story had to have six characters that could be made into pressout play figures, along with scope for smaller characters and objects that could be added to the carousel scene. Where to start? There is a basic vital principle I always bear in mind. This kind of book is going to be played with. The child who gets it is going to use it to create imaginary stories of their own. It’s my job to help them – to prompt them into doing exactly that. I sit in a quiet room and clear my head of everything. Then I concentrate and start to ‘see’ characters in my head and I watch them interacting and doing whatever it is they seem to want to do. This sounds quite mad, but I am effectively mentally ‘playing’ as a child would do. A narrative emerges. It must have movement, action and speech. It must be a scenario a child will want to play.

The books I was commissioned to write already had subjects – a princess castle and a tropical fairy garden. The paper-engineered carousel part of the project was already being designed, and the story part of the book was already laid out in sections, with a rough word count. There were four spreads, and there could be no more or less. Added to this, each story had to have six characters that could be made into pressout play figures, along with scope for smaller characters and objects that could be added to the carousel scene. Where to start? There is a basic vital principle I always bear in mind. This kind of book is going to be played with. The child who gets it is going to use it to create imaginary stories of their own. It’s my job to help them – to prompt them into doing exactly that. I sit in a quiet room and clear my head of everything. Then I concentrate and start to ‘see’ characters in my head and I watch them interacting and doing whatever it is they seem to want to do. This sounds quite mad, but I am effectively mentally ‘playing’ as a child would do. A narrative emerges. It must have movement, action and speech. It must be a scenario a child will want to play.

I would approach a text the same way in something as tightly-controlled as a sound book. This type of book has to have a certain number of sounds, which are varied enough to make playing fun. The stories must work hard. They must give lots of opportunity to push the sound buttons, and I would really feel I’d done my job properly if I created characters that a child could take and use in their own imaginary stories, using the sounds in their own way. For this to happen the characters must be quite simple but have something fun about them – a name, a repeated speech phrase or a particular feature perhaps. Ok, this type of work is not poetry or high art. But that doesn’t mean sentences should not be well-constructed, that there should be good story pace. The story must be well-formed and work if read out loud. It must always work well out loud, which means paying close attention to the rhythm of the sentences (necessarily assuming common speech patterns). A lot of this type of work is now being done in-house by editors, and all too often it’s being done badly because it’s not just a question of ‘putting down words’ to fill a space. It’s about visualizing the child using the book before you put a single word down on paper. Then it’s about reading out loud to get the sentences right. Just because such a text might never be up for a literary prize, and just because it takes days not years, it does not mean it should not be the best possible use of words.

I would approach a text the same way in something as tightly-controlled as a sound book. This type of book has to have a certain number of sounds, which are varied enough to make playing fun. The stories must work hard. They must give lots of opportunity to push the sound buttons, and I would really feel I’d done my job properly if I created characters that a child could take and use in their own imaginary stories, using the sounds in their own way. For this to happen the characters must be quite simple but have something fun about them – a name, a repeated speech phrase or a particular feature perhaps. Ok, this type of work is not poetry or high art. But that doesn’t mean sentences should not be well-constructed, that there should be good story pace. The story must be well-formed and work if read out loud. It must always work well out loud, which means paying close attention to the rhythm of the sentences (necessarily assuming common speech patterns). A lot of this type of work is now being done in-house by editors, and all too often it’s being done badly because it’s not just a question of ‘putting down words’ to fill a space. It’s about visualizing the child using the book before you put a single word down on paper. Then it’s about reading out loud to get the sentences right. Just because such a text might never be up for a literary prize, and just because it takes days not years, it does not mean it should not be the best possible use of words.

www.moirabutterfield.com

@moiraworld

After last week’s detailed description of a one-off picture book’s journey to press, I thought I would write about another much faster type of picture book story-writing. I mean writing to fit a detailed brief for a book that is paper-engineered and could be described as toy-related. Some blog-readers may get the opportunity to do this, and it requires a different way of thinking. Here’s an example. A couple of weeks ago I got an urgent email. Such projects are almost always on a short schedule and if you don’t like working fast, never take them on. Be aware that such projects are fee-based and do not carry royalties, so do not consider the work if this is an issue for you. The project was to write stories for two carousel books. These are books with a story joined to a section that folds around to create a kind of dollshouse scene (I’ll attach a picture showing a carousel book. It’s not mine but it shows the concept).

The books I was commissioned to write already had subjects – a princess castle and a tropical fairy garden. The paper-engineered carousel part of the project was already being designed, and the story part of the book was already laid out in sections, with a rough word count. There were four spreads, and there could be no more or less. Added to this, each story had to have six characters that could be made into pressout play figures, along with scope for smaller characters and objects that could be added to the carousel scene. Where to start? There is a basic vital principle I always bear in mind. This kind of book is going to be played with. The child who gets it is going to use it to create imaginary stories of their own. It’s my job to help them – to prompt them into doing exactly that. I sit in a quiet room and clear my head of everything. Then I concentrate and start to ‘see’ characters in my head and I watch them interacting and doing whatever it is they seem to want to do. This sounds quite mad, but I am effectively mentally ‘playing’ as a child would do. A narrative emerges. It must have movement, action and speech. It must be a scenario a child will want to play.

The books I was commissioned to write already had subjects – a princess castle and a tropical fairy garden. The paper-engineered carousel part of the project was already being designed, and the story part of the book was already laid out in sections, with a rough word count. There were four spreads, and there could be no more or less. Added to this, each story had to have six characters that could be made into pressout play figures, along with scope for smaller characters and objects that could be added to the carousel scene. Where to start? There is a basic vital principle I always bear in mind. This kind of book is going to be played with. The child who gets it is going to use it to create imaginary stories of their own. It’s my job to help them – to prompt them into doing exactly that. I sit in a quiet room and clear my head of everything. Then I concentrate and start to ‘see’ characters in my head and I watch them interacting and doing whatever it is they seem to want to do. This sounds quite mad, but I am effectively mentally ‘playing’ as a child would do. A narrative emerges. It must have movement, action and speech. It must be a scenario a child will want to play.

I would approach a text the same way in something as tightly-controlled as a sound book. This type of book has to have a certain number of sounds, which are varied enough to make playing fun. The stories must work hard. They must give lots of opportunity to push the sound buttons, and I would really feel I’d done my job properly if I created characters that a child could take and use in their own imaginary stories, using the sounds in their own way. For this to happen the characters must be quite simple but have something fun about them – a name, a repeated speech phrase or a particular feature perhaps. Ok, this type of work is not poetry or high art. But that doesn’t mean sentences should not be well-constructed, that there should be good story pace. The story must be well-formed and work if read out loud. It must always work well out loud, which means paying close attention to the rhythm of the sentences (necessarily assuming common speech patterns). A lot of this type of work is now being done in-house by editors, and all too often it’s being done badly because it’s not just a question of ‘putting down words’ to fill a space. It’s about visualizing the child using the book before you put a single word down on paper. Then it’s about reading out loud to get the sentences right. Just because such a text might never be up for a literary prize, and just because it takes days not years, it does not mean it should not be the best possible use of words.

I would approach a text the same way in something as tightly-controlled as a sound book. This type of book has to have a certain number of sounds, which are varied enough to make playing fun. The stories must work hard. They must give lots of opportunity to push the sound buttons, and I would really feel I’d done my job properly if I created characters that a child could take and use in their own imaginary stories, using the sounds in their own way. For this to happen the characters must be quite simple but have something fun about them – a name, a repeated speech phrase or a particular feature perhaps. Ok, this type of work is not poetry or high art. But that doesn’t mean sentences should not be well-constructed, that there should be good story pace. The story must be well-formed and work if read out loud. It must always work well out loud, which means paying close attention to the rhythm of the sentences (necessarily assuming common speech patterns). A lot of this type of work is now being done in-house by editors, and all too often it’s being done badly because it’s not just a question of ‘putting down words’ to fill a space. It’s about visualizing the child using the book before you put a single word down on paper. Then it’s about reading out loud to get the sentences right. Just because such a text might never be up for a literary prize, and just because it takes days not years, it does not mean it should not be the best possible use of words.

Published on September 26, 2012 00:48

No comments have been added yet.