Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 80

March 26, 2013

Humdinger! - doing a picture book event for toddlers, by Malachy Doyle

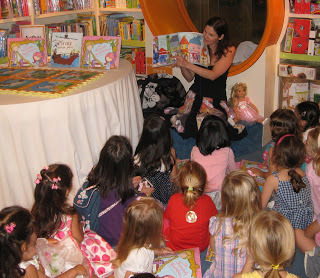

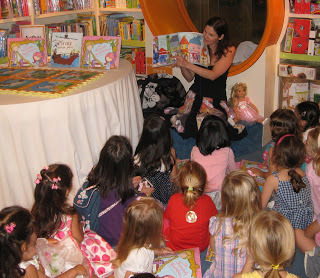

One of the strange things about being a picture book writer is that you get asked to do loads of events, but because the vast majority are in schools, you’re rarely if ever actually reading your books to the age groups they’re written for. I read picture books to everyone, from age 0 to 99, and they always seem to enjoy them - but it’s delightful to read them to real live pre-schoolers, for a change.

That’s why I love doing events like the one I did recently for the Humdinger Festival in Derry. It’s a lovely little festival of children’s books run by Dog Ears – a new and exciting children's media company, and it was part of the year-long celebration of Derry as the first UK City of Culture.

At the pre-planning stage the organisers asked me what age group I wanted to read to and I replied 3 to 8 (though I said if anyone wants to bring younger or older children, don’t turn them away – I know how complicated it can be, sorting out child cover in a busy family).

I was delighted, therefore, to see lots of little ones turning up. Now little ones, as we all know, have limited attention spans. They can run about the place and yell and stuff... If they like you, that have a propensity to edge closer and closer till they're crawling up your trouser leg... They shout ‘I have a dog!’ and ‘I need a wee!’ So if they sit still and listen, or wriggle and listen, or join in and listen, even for a few minutes at a time, even just some of them, then you’re on a winner. It’s chaos – but it’s wonderful.

Well in Derry, on Saturday morning, I did 45 minutes - and most of my audience were still there at the end. I read them Well, A Crocodile Can – my first pop-up book - and they flapped their ears to keep cool, pretended to slurp a bathful of juice, stuck out their tongues to see whose was the longest, swung from trees like a monkey, stood on one foot while singing Twinkle Twinkle…

I read One, Two, Three, O’Leary – while they joined in the songs (sort of), counted down the ten children falling out of bed, and all pretended to sleep at the end. (a rare moment’s peace)...

I read Too Noisy!, my most recent picture book, and when they all joined in, with great enthusiasm, on the HELP! spread, I was surprised the security guards (Derry’s still big on security guards) didn’t come rushing in...

I read Too Noisy!, my most recent picture book, and when they all joined in, with great enthusiasm, on the HELP! spread, I was surprised the security guards (Derry’s still big on security guards) didn’t come rushing in...

I read Big Pig, and they all wanted Farmer Joe to let our eponymous hero, who'd saved him from the deep dark hole, live in his farmhouse with him , rather than be sent out to the field.

A little girl took the part of the boy in Hungry! Hungry! Hungry! Guess who played the Grisly Ghastly Goblin? You guessed it...

And we finished, as we always do, with The Dancing Tiger. Because it’s quiet. And calm. And sends them away with a warm glow (well, the Mums, anyway) Two little girls came out to dance with my tiger. (Though the first one went all shy on us and almost forgot how…)

So that was it. Except they didn’t want to go yet, so we had to do one more story…

Oh, and while I was there I got to meet Meg Rosoff and Alex T. Smith, and to go and see the phenomenon that is Julia Donaldson, doing the second of her two sell-out shows that day in the Millenium Forum (a 900-seater auditorium). Proof, if proof were needed, that Dog Ears have got it right - that there’s an enormous demand out there for happy, fun, children’s book events, even in a place without much of a history of such.

So congratulations to Dog Ears and the people of Derry. What a Humdinger of a festival!

Published on March 26, 2013 02:17

March 21, 2013

Words? Who needs them? by Gill Robins

Welcome to guest blogger Gill Robins. Gill was a leading English teacher who now reviews for Books for Keeps, is a Senior Editor and a published author, too. The Whoosh Book, an interactive approach to teaching classic and contemporary text through drama, is due for publication in May 2013. Gill was awarded the UKLA John Downing Award for creative and innovative approaches to teaching English. Her thoughtful and insightful blog is at http://teacherturnedwriter.gillrobins.com/

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict.

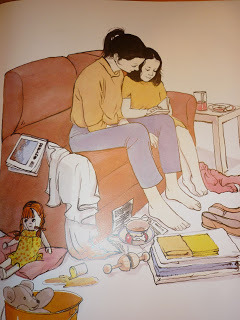

Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...

Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.

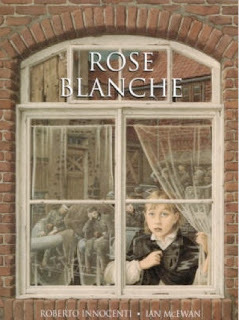

I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's Rose Blanche) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably in utero) in order to gain advantage?

I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate.

Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:

Rose Blanche. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:

‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’

‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’

‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’

‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’

‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’

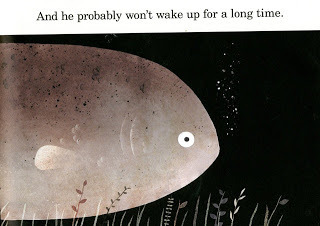

As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.

Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?

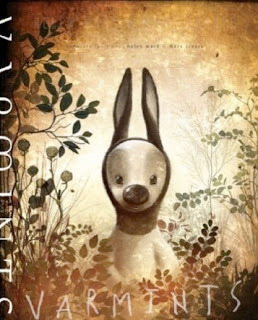

My next ‘favourite’ is Varmints, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:

‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’

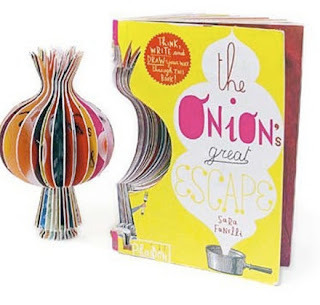

And finally, Sara Fanelli's The Onion’s Great Escape – an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.

Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.

So, words, who needs ‘em?

Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and its mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict.

Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...

Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.

I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's Rose Blanche) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably in utero) in order to gain advantage?

I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate.

Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:

Rose Blanche. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:

‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’

‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’

‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’

‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’

‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’

As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.

Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?

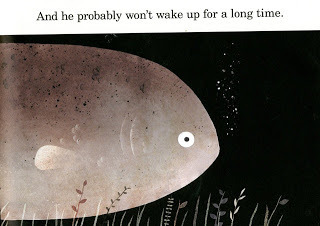

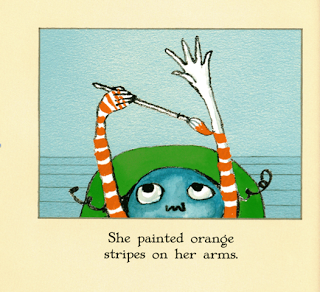

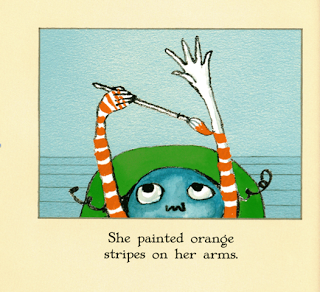

My next ‘favourite’ is Varmints, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:

‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’

And finally, Sara Fanelli's The Onion’s Great Escape – an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.

Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.

So, words, who needs ‘em?

Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and its mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.

Published on March 21, 2013 01:00

Words? Who needs them?

Welcome to guest blogger

Gill Robins

. Gill was a leading English teacher who now reviews for Books for Keeps, is a Senior Editor and a published author, too. The Whoosh Book, an interactive approach to teaching classic and contemporary text through drama, is due for publication in May 2013. Gill was awarded the UKLA John Downing Award for creative and innovative approaches to teaching English. Her thoughtful and insightful blog is at http://teacherturnedwriter.gillrobins...

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict. <!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Verdana; panose-1:2 11 6 4 3 5 4 4 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:11.0pt; font-family:Helvetica; mso-ascii-font-family:Verdana; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-font-family:Verdana; mso-bidi-font-family:Helvetica;} a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {color:blue; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed {mso-style-noshow:yes; color:purple; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Rose Blanche</i>) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">in utero</i>) in order to gain advantage?</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate. </span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-n2w4LwpRuSo..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="320" src="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-n2w4LwpRuSo..." width="239" /></a></span></div><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Rose Blanche</span></i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:</span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">My next ‘favourite’ is <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Varmints</i>, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:</span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’</span></i></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-wQFFIOGT2LE..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="320" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-wQFFIOGT2LE..." width="257" /></a></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">And finally, Sara Fanelli's <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">The Onion’s Great Escape</i>– an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything ... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/--bHkgotSwQo..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="305" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/--bHkgotSwQo..." width="320" /></a></span></div><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">So, words, who needs ‘em? </span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and it’s mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div>

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict. <!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Verdana; panose-1:2 11 6 4 3 5 4 4 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:11.0pt; font-family:Helvetica; mso-ascii-font-family:Verdana; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-font-family:Verdana; mso-bidi-font-family:Helvetica;} a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {color:blue; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed {mso-style-noshow:yes; color:purple; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} @page Section1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 90.0pt 72.0pt 90.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.Section1 {page:Section1;} </style></span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Rose Blanche</i>) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">in utero</i>) in order to gain advantage?</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate. </span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-n2w4LwpRuSo..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="320" src="http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-n2w4LwpRuSo..." width="239" /></a></span></div><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Rose Blanche</span></i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:</span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’</span></i></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">My next ‘favourite’ is <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">Varmints</i>, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:</span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><i><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’</span></i></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-wQFFIOGT2LE..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="320" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-wQFFIOGT2LE..." width="257" /></a></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">And finally, Sara Fanelli's <i style="mso-bidi-font-style: normal;">The Onion’s Great Escape</i>– an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything ... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/--bHkgotSwQo..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" height="305" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/--bHkgotSwQo..." width="320" /></a></span></div><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">So, words, who needs ‘em? </span></span><br /><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><br /></span><span style="font-family: Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif;"><span style="font-size: 11.0pt;">Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and it’s mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.</span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div>

Published on March 21, 2013 01:00

March 16, 2013

My Writing Space - Lynne Garner

Spurred on by Malachy's lovely post 'Want to see my writing desk?' I've decide to do my own.

As you can see my writing space is not as interesting as Malachy's. In fact I'd say it's fairly business like. I must admit you are seeing my desk at it's best. I did tidy the pile of letters and bills and even dust it a little. But as I stood back to take the shot you see below I surprised myself at just how little of 'me' I have on it.

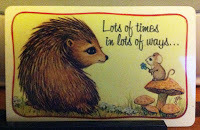

The only item that has sentimental value is a credit card sized picture of a hedgehog (I'm known for my love of these prickly creatures) and a little mouse (just dawned on me my first book was about a hedgehog and a mouse - I wonder if that's just coincidence). As you can see on the front are the words "lots of times in lots of ways..." and on the back are the words "friends mean more than words can say."

It was given to me by a friend years ago, who is five days younger than I am. I've been lucky, she's always been there. We shared our entire school life, even sitting next to one another during story time in our infants class. Although we now live a three hour drive from one another we're still in contact. But that's it, everything else is connected to my craft of writing. So the shelves are filled with reference books, books on writing and loads of note pads filled with scribbled ideas.

However I don't occupy this space alone. When I am sitting at my desk working on a new magazine feature or book I'm often tapping to the sound of a snoring dog from the chair behind me. And as you can see Tasha does like to get comfortable.

To round off this post I wondered what goes on behind your back (if anything) whilst you write and what 'special' item do you have on your desk?

As you can see my writing space is not as interesting as Malachy's. In fact I'd say it's fairly business like. I must admit you are seeing my desk at it's best. I did tidy the pile of letters and bills and even dust it a little. But as I stood back to take the shot you see below I surprised myself at just how little of 'me' I have on it.

The only item that has sentimental value is a credit card sized picture of a hedgehog (I'm known for my love of these prickly creatures) and a little mouse (just dawned on me my first book was about a hedgehog and a mouse - I wonder if that's just coincidence). As you can see on the front are the words "lots of times in lots of ways..." and on the back are the words "friends mean more than words can say."

It was given to me by a friend years ago, who is five days younger than I am. I've been lucky, she's always been there. We shared our entire school life, even sitting next to one another during story time in our infants class. Although we now live a three hour drive from one another we're still in contact. But that's it, everything else is connected to my craft of writing. So the shelves are filled with reference books, books on writing and loads of note pads filled with scribbled ideas.

However I don't occupy this space alone. When I am sitting at my desk working on a new magazine feature or book I'm often tapping to the sound of a snoring dog from the chair behind me. And as you can see Tasha does like to get comfortable.

To round off this post I wondered what goes on behind your back (if anything) whilst you write and what 'special' item do you have on your desk?

Published on March 16, 2013 03:30

March 10, 2013

Ideas Composting by Jane Clarke

Like the best compost, ideas need time to ripen and mature. Here's a quick guide to ideas composting, with thanks to www.recyclenow.com whose tips

(in italics)

I have stolen and commented on. The wonderful allotment sketches are from Julia Woolf’s sketchbook.

1. Find the right site. Choose a place where you can easily add ingredients to the bin and get the compost out.

The type of bin may vary:The Brain Bin – tends to overflow and can be difficult to access on occasion.The Computer Bin – ditto.The Cloud Bin - ditto.

The Notebook Bin – ditto, and you will need more than one.

2. A dd the right ingredients …everything from vegetable and fruit peelings to teabags, toilet roll tubes, cereal boxes and eggshells….

Add words and pictures of anything and everything that interests you.

3. Fill it up A 50/50 mix of greens and browns is the perfect recipe...

A 50/50 mix of tea/coffee and chocolate is the perfect recipe for good composting. The occasional glass of wine won’t do any harm but too much may damage the contents of your bin.

4. Wait a while. It takes between nine and twelve months for your compost to become ready for use

Sounds about right. Glance in your bin occasionally, but get on with tending to other things.

5. Ready to use Once your compost has turned into a crumbly, dark material, resembling thick, moist soil and gives off an earthy, fresh aroma, you know it’s ready to use.

Your ideas have mingled and matured into something that feels right - and hopefully smells fresh, too!

6. Removing the compost Scoop out the fresh compost with a garden fork, spade or trowel.

Pen, pencils, paint or keyboard may also be used.

7. Use it. Don’t worry if your compost looks a little lumpy with twigs and bits of eggshell – this is perfectly normal.

Phew!

Thanks www.recyclenow.com. The next tip is mine:

8. Nurture what grows in it.

Among the weeds, something is budding that has the potential to grow into something extraordinary...

Jane first heard the word ‘composting’ in this context from her agent Celia Catchpole, and thought it summed up the process perfectly. Jane's website Jane's facebook author page Julia Woolf did the sketches in very cold and sometimes windy conditions, but loved every minute. She says ‘The allotment’s a very special (sort of hidden) place, like the secret garden.’ Julia's facebook illustrator page

1. Find the right site. Choose a place where you can easily add ingredients to the bin and get the compost out.

The type of bin may vary:The Brain Bin – tends to overflow and can be difficult to access on occasion.The Computer Bin – ditto.The Cloud Bin - ditto.

The Notebook Bin – ditto, and you will need more than one.

2. A dd the right ingredients …everything from vegetable and fruit peelings to teabags, toilet roll tubes, cereal boxes and eggshells….

Add words and pictures of anything and everything that interests you.

3. Fill it up A 50/50 mix of greens and browns is the perfect recipe...

A 50/50 mix of tea/coffee and chocolate is the perfect recipe for good composting. The occasional glass of wine won’t do any harm but too much may damage the contents of your bin.

4. Wait a while. It takes between nine and twelve months for your compost to become ready for use

Sounds about right. Glance in your bin occasionally, but get on with tending to other things.

5. Ready to use Once your compost has turned into a crumbly, dark material, resembling thick, moist soil and gives off an earthy, fresh aroma, you know it’s ready to use.

Your ideas have mingled and matured into something that feels right - and hopefully smells fresh, too!

6. Removing the compost Scoop out the fresh compost with a garden fork, spade or trowel.

Pen, pencils, paint or keyboard may also be used.

7. Use it. Don’t worry if your compost looks a little lumpy with twigs and bits of eggshell – this is perfectly normal.

Phew!

Thanks www.recyclenow.com. The next tip is mine:

8. Nurture what grows in it.

Among the weeds, something is budding that has the potential to grow into something extraordinary...

Jane first heard the word ‘composting’ in this context from her agent Celia Catchpole, and thought it summed up the process perfectly. Jane's website Jane's facebook author page Julia Woolf did the sketches in very cold and sometimes windy conditions, but loved every minute. She says ‘The allotment’s a very special (sort of hidden) place, like the secret garden.’ Julia's facebook illustrator page

Published on March 10, 2013 23:00

March 6, 2013

Happy World Book Day (Week) and how to do the best school author visit you can by Juliet Clare Bell

On World Book Day week, with one visit under my belt and three more to go, I thought I’d write about school author visits. For many of us, it’s the busiest week of the year and we’re all doing our thing in different schools but a lot of us don’t really know what other authors are actually doing. Our school visits will reflect our personality in the same way that writing does, which means that the visits will be all be different. I'm not an expert. I’ve only been doing this a couple of years and there are plenty of authors with more experience –including some of the ones I’ve included in this post. But I'm really interested in what makes a good visit? Or more important, what makes an excellent, inspiring visit? And can we learn from each other (like we do in critique groups with our writing)?

I asked some authors, illustrators, teachers and librarians for their thoughts on and experiences of school visits...

ENTHUSE, ENTERTAIN, INSPIRE

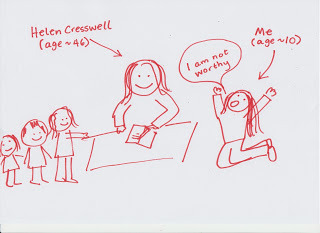

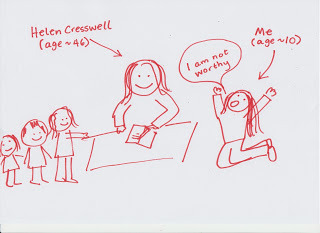

I will remember forever when Helen Cresswell, children’s author (Lizzie Dripping, The Bagthorpe Saga) came to our school when I was a child (and I’m gutted as I’ve misplaced the photo of her signing my book. I had it last week!). So here’s a picture of it instead:

She was a real author and a real person. She said things that I still remember over thirty years later. But she didn’t teach us...

DON’T BE A TEACHER –it comes up time and again when people talk about what they want from author visits. You’re NOT a teacher (well if you are normally, you’re not today, whilst you’re being an author).

Candy Gourlay (author of Tall Story) says: “Don’t be the teacher...the children want an experience that transports them outside the school barriers”...

“And so do the teachers,” says George Kirk, teacher and children’s writer.

You can provide something that teachers cannot provide. That’s why you're there. Give the children something that a teacher cannot give them: an insight into an author’s world.

Jane Clarke (author of Stuck in the Mud, amongst many other books, and fellow Picture Book Den-er) says: “Aim to inspire and enthuse and leave them bursting with imaginative ideas they can’t wait to express in words and/or pictures”.

But how do you do that?

BE YOU-WRIT LARGE

Children love to feel like you’re letting them in on a secret. Tell them things about you and how you write. And make it entertaining.

Mine your past. What can you use from your past to give children an idea of what makes you tick and how you ended up doing what you’re doing? What funny/interesting things have happened to you that you can use in a way to put your points across? Can you make it personal (without feeling like you’re giving too much of yourself away)?

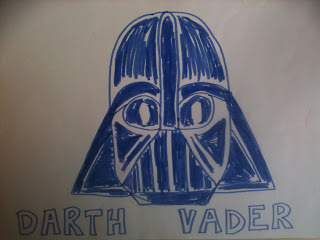

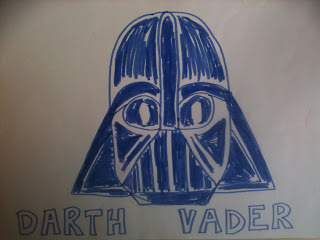

Why on earth would I want to tell children about the time I blurted out something excruciatingly embarrassing to Darth Vader when he came to my school in 1977 and it was being filmed for the local news (and they subsequently cut the story from the television)?

Because a) it’s funny and it’s a great start to an assembly to have everyone laughing in horror; b) it brings us closer –I’m human and it’s true. We all do embarrassing things. But I’m letting them laugh at me and I’m laughing at myself; c) it’s relevant to the points I’m going to be putting across later about writing.

Similarly, I play a game where I tell the children stories about me as a child and they have to guess which one is not true.

(Children sometimes guess which one isn’t true –but they usually think it’s not true because it’s so outrageous. In reality, it’s actually not true because the true story is even MORE shocking.)

The children all get involved in trying to guess; they get to laugh at me (again); and once again, it’s relevant to the points I want to make about writing–but in a way where I don’t come across as being a teacher.

Mel Lerway (parent) says about an event by Andy Stanton: “he has the children engaged, excited and enthused about reading.... his presenting style fits with his writing style but I guess the principles are the same [for any author]–energy (bucketloads), humour, slapstick humour and a dash of good old reading out loud...”.

Steve Cole (author of the Astrosaurs series) says: “I just try and use comedy to engage with them and to interact as often and as sillily as possible. I try and make them think it’s very easy to write and give them ideas on how they can come up with their own stories, to make writing seem as inclusive and fun as possible. Never make it seem like an amazing, mystical act, but rather something like sport or a hobby that they’ll get better at the more they do”.

Respect your audience and prepare well –to be yourself in an accessible and engaging way.

In a great blog post on the value of author visits to schools and pupils, Deb Lund (children’s author) talks about how school visits can demystify authors, motivate writing and ignite sparks. By being yourself and letting children into the secret of the work involved in writing something good and the importance of persistence you can also validate what the teachers have been teaching but in a way that’s fun and memorable. To this end, it’s great to bring

PROPS!

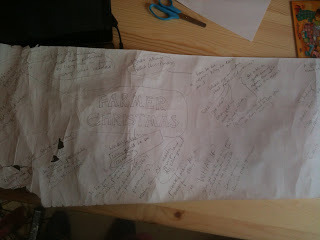

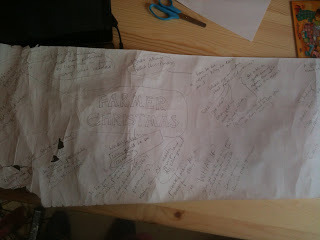

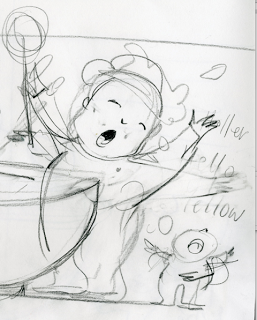

Children love seeing your earliest workings out for your story

(they get to unravel it –and it’s long....)

Let them see how messy it is (in my case, at least), different drafts, rejection letters, comments from critique groups, roughs, editor comments, proofs and final book. It shows the reality of it –and the work and perseverance needed- but in a way that a teacher CANNOT SHOW THEM.

BUBBLES

Who doesn’t love bubbles? I always use bubbles –because they’re great, and because children love them but also because they make complete sense of the points I’m trying to get across.

Time and again, teachers, librarians and authors asked came up with one major point:

BE INTERACTIVE

For illustrators, this is often “drawing, live drawing! Do a bit of that and the kids are hooked,” says Kate Pankhurst, illustrator and author of Mariella Mystery “Get the kids up adding to your drawings and use their ideas to build a new character for them as a demo before they try for themselves.”

But there are plenty of other ways to be interactive for those of us who are less good at drawing...

The writers and teachers I asked said...

Ask lots of questions, do quizzes, let them ask you questions, play games –get children involved.

Julie Fulton (author of Mrs McCready was Ever So Greedy) uses a greedy teddy bear to get children coming up with a class poem. I let the children take charge of me and I become their character in their story where they choose, collectively, what happens to me. Lots of authors also have a bag with objects in so that children can take objects out and come up with stories. The objects are rarely used in the way they might be in real life...

Here’s my bag. The ballet shoe has been a home to various different creatures; a boat; a bed for a tiny person; a catapult etc. The blue ball has been a planet, a weapon, a spaceship... This gets children interacting beautifully with each other, too.

For many picture books, at least, reading to the children can be highly interactive...

In Don’t Panic, Annika! there are children being various characters up at the front, but everyone in the audience also joins in with panicky faces, counting, taking deep breaths and shouting out phrases.

With older children, picture books are great because you can talk about the structure of the story that they’ll be using themselves and coming across in novels, but on a much smaller, manageable scale.

And you can make your visits even more interactive by encouraging the school/children to do some preparation in advance of your visit –let them know your web address (I’ve had children bring up things about me that I’d completely forgotten I put on my website) and Bryony Pearce says it’s great to put up at least one chapter of a novel if that’s what you’re writing on your site so children can read some of your work in advance. This might be more important for novels than picture books, but I’ve got a YouTube video of a real-life Annika reading Don’t Panic, Annika! that schools have sometimes accessed via my website before a visit.

I’ve not touched on Skype visits here –I did my first two just a couple of weeks ago (with Lori Degman, author of 1 Zany Zoo (her and the school children I was talking to over in Chicago and me and the school children she was talking to here in the UK). I’d love to hear from other authors/teachers who’ve done/been part of Skype visits. It struck me how different the interactive element has to be out of necessity and I’d love to know how people keep virtual visits as interactive as they can.

How can we improve our visits and make them even better?

If it’s possible to get feedback, it can be extremely helpful. Sian Cafferkey (teacher and fan of author visits) says: “If you are selling books - which is fine - don't limit signing just to those who are buying... As a teacher - make what you say/do suitable for the age group you're meeting... We've had authors who just have a standard spiel that they think will work for all ages - it won't!”

Teachers can provide excellent feedback (though it might be nerve-wracking to ask them).

I’ve recently been observed by an agent who arranges school visits for artists (including authors) whose books I’m now on. Two weeks before that, I got to watch a day of Sarwat Chadda (author of Ash Mistry and the Savage Fortress), and it struck me how useful it would be for us to sit in on other people’s visits periodically –for us and for them. And in the meantime if that’s not possible, perhaps we could continue to share some tips and thoughts with each other. After all, we’re trying to provide the best session we can possibly deliver to the children we’re visiting. And if we do it well, it can have a lasting effect on the children we see.

Finally, I think it’s crucial to ask yourself why are you doing visits?

There are lots of reasons authors and illustrators visit schools: to inspire children to read and write and dream...; to earn much needed income so you’re able to write; to promote your books; to sell your books. Different people do it for different reasons: as someone who is passionate about getting children engaged in reading for pleasure (I’ve currently got a grant to do just this) and improving their lives and confidence, the focus of my visits is to inspire children. I need to be paid for it –it’s professional work –just as plumbers and actors and doctors and hair dressers get paid for their professional work. If I did it unpaid, it would be costing me money, as it is time that I am not earning from writing. And it makes it more possible for me to sustain a life where I write. But I don’t do it to promote my books or to sell them –I think with picture books this is different from books for older children as it’s usually parents buying the books and they won’t be there at the visits. For events outside school –festival and bookshop events and those run through parenting groups or even nurseries, promoting and selling books may be a much clearer reason behind the event. Whatever the reason, be aware of why you’re doing it. And if you don’t actually enjoy it, you should say no –for your sake and for the sake of the children you’re visiting. It’s hard to inspire when you don’t feel inspired to be there. If you’d prefer to stay at home and write books instead, then you can inspire them from a distance with your next book.

Thank you to all the authors, illustrators and teachers who offered their thoughts and tips on school visits for this post.

Are you an author or illustrator who does visits, or a teacher or librarian who arranges them? I’d love to hear what works well for you... Do you have any top tips on what to do/what not to do? Do you have any thoughts on fees? Thank you.

Juliet Clare Bell is the author of Don’t Panic, Annika! (illustrated by Jennifer E Morris; Piccadilly Press); The Kite Princess (illustrated by Laura Kate Chapman, narrated by Imelda Staunton; Barefoot Books) and Pirate Picnic (an early reader, illustrated by Mirella Minelli; Franklin Watts).

www.julietclarebell.com

I asked some authors, illustrators, teachers and librarians for their thoughts on and experiences of school visits...

ENTHUSE, ENTERTAIN, INSPIRE

I will remember forever when Helen Cresswell, children’s author (Lizzie Dripping, The Bagthorpe Saga) came to our school when I was a child (and I’m gutted as I’ve misplaced the photo of her signing my book. I had it last week!). So here’s a picture of it instead:

She was a real author and a real person. She said things that I still remember over thirty years later. But she didn’t teach us...

DON’T BE A TEACHER –it comes up time and again when people talk about what they want from author visits. You’re NOT a teacher (well if you are normally, you’re not today, whilst you’re being an author).

Candy Gourlay (author of Tall Story) says: “Don’t be the teacher...the children want an experience that transports them outside the school barriers”...

“And so do the teachers,” says George Kirk, teacher and children’s writer.

You can provide something that teachers cannot provide. That’s why you're there. Give the children something that a teacher cannot give them: an insight into an author’s world.

Jane Clarke (author of Stuck in the Mud, amongst many other books, and fellow Picture Book Den-er) says: “Aim to inspire and enthuse and leave them bursting with imaginative ideas they can’t wait to express in words and/or pictures”.

But how do you do that?

BE YOU-WRIT LARGE

Children love to feel like you’re letting them in on a secret. Tell them things about you and how you write. And make it entertaining.

Mine your past. What can you use from your past to give children an idea of what makes you tick and how you ended up doing what you’re doing? What funny/interesting things have happened to you that you can use in a way to put your points across? Can you make it personal (without feeling like you’re giving too much of yourself away)?

Why on earth would I want to tell children about the time I blurted out something excruciatingly embarrassing to Darth Vader when he came to my school in 1977 and it was being filmed for the local news (and they subsequently cut the story from the television)?

Because a) it’s funny and it’s a great start to an assembly to have everyone laughing in horror; b) it brings us closer –I’m human and it’s true. We all do embarrassing things. But I’m letting them laugh at me and I’m laughing at myself; c) it’s relevant to the points I’m going to be putting across later about writing.

Similarly, I play a game where I tell the children stories about me as a child and they have to guess which one is not true.

(Children sometimes guess which one isn’t true –but they usually think it’s not true because it’s so outrageous. In reality, it’s actually not true because the true story is even MORE shocking.)

The children all get involved in trying to guess; they get to laugh at me (again); and once again, it’s relevant to the points I want to make about writing–but in a way where I don’t come across as being a teacher.

Mel Lerway (parent) says about an event by Andy Stanton: “he has the children engaged, excited and enthused about reading.... his presenting style fits with his writing style but I guess the principles are the same [for any author]–energy (bucketloads), humour, slapstick humour and a dash of good old reading out loud...”.

Steve Cole (author of the Astrosaurs series) says: “I just try and use comedy to engage with them and to interact as often and as sillily as possible. I try and make them think it’s very easy to write and give them ideas on how they can come up with their own stories, to make writing seem as inclusive and fun as possible. Never make it seem like an amazing, mystical act, but rather something like sport or a hobby that they’ll get better at the more they do”.

Respect your audience and prepare well –to be yourself in an accessible and engaging way.

In a great blog post on the value of author visits to schools and pupils, Deb Lund (children’s author) talks about how school visits can demystify authors, motivate writing and ignite sparks. By being yourself and letting children into the secret of the work involved in writing something good and the importance of persistence you can also validate what the teachers have been teaching but in a way that’s fun and memorable. To this end, it’s great to bring

PROPS!

Children love seeing your earliest workings out for your story

(they get to unravel it –and it’s long....)

Let them see how messy it is (in my case, at least), different drafts, rejection letters, comments from critique groups, roughs, editor comments, proofs and final book. It shows the reality of it –and the work and perseverance needed- but in a way that a teacher CANNOT SHOW THEM.

BUBBLES

Who doesn’t love bubbles? I always use bubbles –because they’re great, and because children love them but also because they make complete sense of the points I’m trying to get across.

Time and again, teachers, librarians and authors asked came up with one major point:

BE INTERACTIVE

For illustrators, this is often “drawing, live drawing! Do a bit of that and the kids are hooked,” says Kate Pankhurst, illustrator and author of Mariella Mystery “Get the kids up adding to your drawings and use their ideas to build a new character for them as a demo before they try for themselves.”

But there are plenty of other ways to be interactive for those of us who are less good at drawing...

The writers and teachers I asked said...

Ask lots of questions, do quizzes, let them ask you questions, play games –get children involved.

Julie Fulton (author of Mrs McCready was Ever So Greedy) uses a greedy teddy bear to get children coming up with a class poem. I let the children take charge of me and I become their character in their story where they choose, collectively, what happens to me. Lots of authors also have a bag with objects in so that children can take objects out and come up with stories. The objects are rarely used in the way they might be in real life...

Here’s my bag. The ballet shoe has been a home to various different creatures; a boat; a bed for a tiny person; a catapult etc. The blue ball has been a planet, a weapon, a spaceship... This gets children interacting beautifully with each other, too.

For many picture books, at least, reading to the children can be highly interactive...

In Don’t Panic, Annika! there are children being various characters up at the front, but everyone in the audience also joins in with panicky faces, counting, taking deep breaths and shouting out phrases.

With older children, picture books are great because you can talk about the structure of the story that they’ll be using themselves and coming across in novels, but on a much smaller, manageable scale.

And you can make your visits even more interactive by encouraging the school/children to do some preparation in advance of your visit –let them know your web address (I’ve had children bring up things about me that I’d completely forgotten I put on my website) and Bryony Pearce says it’s great to put up at least one chapter of a novel if that’s what you’re writing on your site so children can read some of your work in advance. This might be more important for novels than picture books, but I’ve got a YouTube video of a real-life Annika reading Don’t Panic, Annika! that schools have sometimes accessed via my website before a visit.

I’ve not touched on Skype visits here –I did my first two just a couple of weeks ago (with Lori Degman, author of 1 Zany Zoo (her and the school children I was talking to over in Chicago and me and the school children she was talking to here in the UK). I’d love to hear from other authors/teachers who’ve done/been part of Skype visits. It struck me how different the interactive element has to be out of necessity and I’d love to know how people keep virtual visits as interactive as they can.

How can we improve our visits and make them even better?

If it’s possible to get feedback, it can be extremely helpful. Sian Cafferkey (teacher and fan of author visits) says: “If you are selling books - which is fine - don't limit signing just to those who are buying... As a teacher - make what you say/do suitable for the age group you're meeting... We've had authors who just have a standard spiel that they think will work for all ages - it won't!”

Teachers can provide excellent feedback (though it might be nerve-wracking to ask them).

I’ve recently been observed by an agent who arranges school visits for artists (including authors) whose books I’m now on. Two weeks before that, I got to watch a day of Sarwat Chadda (author of Ash Mistry and the Savage Fortress), and it struck me how useful it would be for us to sit in on other people’s visits periodically –for us and for them. And in the meantime if that’s not possible, perhaps we could continue to share some tips and thoughts with each other. After all, we’re trying to provide the best session we can possibly deliver to the children we’re visiting. And if we do it well, it can have a lasting effect on the children we see.

Finally, I think it’s crucial to ask yourself why are you doing visits?

There are lots of reasons authors and illustrators visit schools: to inspire children to read and write and dream...; to earn much needed income so you’re able to write; to promote your books; to sell your books. Different people do it for different reasons: as someone who is passionate about getting children engaged in reading for pleasure (I’ve currently got a grant to do just this) and improving their lives and confidence, the focus of my visits is to inspire children. I need to be paid for it –it’s professional work –just as plumbers and actors and doctors and hair dressers get paid for their professional work. If I did it unpaid, it would be costing me money, as it is time that I am not earning from writing. And it makes it more possible for me to sustain a life where I write. But I don’t do it to promote my books or to sell them –I think with picture books this is different from books for older children as it’s usually parents buying the books and they won’t be there at the visits. For events outside school –festival and bookshop events and those run through parenting groups or even nurseries, promoting and selling books may be a much clearer reason behind the event. Whatever the reason, be aware of why you’re doing it. And if you don’t actually enjoy it, you should say no –for your sake and for the sake of the children you’re visiting. It’s hard to inspire when you don’t feel inspired to be there. If you’d prefer to stay at home and write books instead, then you can inspire them from a distance with your next book.

Thank you to all the authors, illustrators and teachers who offered their thoughts and tips on school visits for this post.

Are you an author or illustrator who does visits, or a teacher or librarian who arranges them? I’d love to hear what works well for you... Do you have any top tips on what to do/what not to do? Do you have any thoughts on fees? Thank you.

Juliet Clare Bell is the author of Don’t Panic, Annika! (illustrated by Jennifer E Morris; Piccadilly Press); The Kite Princess (illustrated by Laura Kate Chapman, narrated by Imelda Staunton; Barefoot Books) and Pirate Picnic (an early reader, illustrated by Mirella Minelli; Franklin Watts).

www.julietclarebell.com

Published on March 06, 2013 16:16

February 28, 2013

Speaking picturebook - Linda Strachan

Writing, for me, is like two sides of a coin. I spend a good bit of time on my own and at other times I am out and about meeting people of all ages and talking about books and writing.

When I am at home in my shed 'Tuscany' I am all on my own. It is the place where I shut out the rest of the world and for some reason I find I can concentrate better there than almost anywhere else.

When I am at home in my shed 'Tuscany' I am all on my own. It is the place where I shut out the rest of the world and for some reason I find I can concentrate better there than almost anywhere else. Some writers write in coffee shops, surrounded by noise and people and they create their own bubble to work in.

I admit I have done this at times but I am too nosy and end up people-watching instead of writing and it's not so good if I am thinking about a picturebook, because I like space to spread papers around so that I can sketch little images and look at how it will lay out over the pages.

Other writers work a table or desk in their kitchen or bedroom or study and I don't suppose it matters as long as you can find that quiet zone in your head where the ideas and characters can come to life.

Elm Park School New ZealandThe other side of my writing life is all about being with people, travelling around to visit schools talking to children, teachers and librarians and talking at events or book festivals or conferences.