Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 76

September 23, 2013

The Dancing Tiger - from birth to rebirth, by Malachy Doyle

It’s 1996 - two years before I become a published author. I’m trying to write a series of animal poems. They’re not particularly brilliant. I go for a ride on my bike. I find myself singing a little tune.

There’s a quiet gentle tiger,in the woods below the hill…

I jump off the bike. Climb over a gate into a field. Write it down. A poem spills out, like a dream.

In time, I get an agent. Things start to happen. But not with the animal poems, which have become a picture book idea called ‘Cards from Uncle Joe’. Each poem is a postcard / birthday card / Christmas card from Joe to his niece, with a little toy animal attached. It's a nice concept, but never really clicks.

It’s 2003. I’m having lunch with Simon and Schuster. I read my editor some scripts. They’re not quite working. I pull out my Dancing Tiger poem. I get to the end, and there's silence. And then I notice the tears, pouring down her face. We’re in business.

They take on a top American husband and wife team, Steve Johnson and Lou Fancher, to illustrate it. It’s quite, quite beautiful.

The Dancing Tiger sells to Viking Penguin in the US, to Australia, Korea, Japan, Spain… Hits shortlists in Ireland, Scotland and America… It gets amazing reviews. People read things into it I’d never even thought of.

I’m invited to the Nestle Children’s Book Award. It wins Silver. Would’ve won Gold if some hotshot kid from Belfast (with a penguin in tow) hadn’t appeared on the scene, all of a sudden…

The Dancing Tiger becomes a firm favourite. I bring a big cuddly one with me to all my readings. It’s the final thing I read, to settle everyone down. Because it's a lullaby, really. A lullaby to love, and family, and imagination, and the power of story. Or so they tell me.

A child comes out and dances with the tiger.

We skipped in spring through bluebells,in summer circled slow.We high-kicked in the autumn leavesand waltzed in winter snow…

Then, in 2010, the emails start arriving. ‘I want / need / must have this book, but can’t find it anywhere.’ That’s when I realise it’s out of print. That I’ve only two copies left. I’m bereft.

The emails keep coming, from all round the world. I reply that I’m as sorry as they are, but the publisher has no plans to reprint. It’s on Kindle, but…

I start forwarding them to Simon and Schuster. One a month, sometimes one a week. I tell my editor that I know books go out of print – that's the business we're in – but this one… this one is special. The way people feel about it is special.

Eventually, to my astonishment, they give in. ‘I've good news for you, Malachy,' they tell me. 'We’re doing a small reprint.’

It's September 2013, and my tiger is back from the long dark night. It’s only a thousand copies, but it means the world to me.

He was lost but now he's found and, for another wee while at least, we’re dancing again. Never give up on your dreams!

You can hear me reading it, on World Book Day a few years ago, to a group of children in the offices of the Guardian newspaper, on http://blogs.guardian.co.uk/culturevu...

Published on September 23, 2013 00:45

September 17, 2013

On Life, Death, Royal Weddings and Mice by Enid Richemont (Guest Blog)

This month's guest on the Picture Book Den is Enid Richemont, who is perhaps best known for her Young Adult novels such as The Game and The Stone That Grew. However here she shares how she recently rediscovered picture books.

I have always loved picture books, and I can still remember being read to from one whose title and author have long since passed into (probably well-deserved) oblivion. It had a picture of a wasp circling around a plump, rosy-cheeked small boy who had just taken a bite out of the apple he was holding, and the text read: "Don't sting me," Fat Freddie said. "My apple you can have instead." Not the most impressive of verses (and these days, the word 'fat' as applied to a child would never pass), but my small, long-ago self was evidently grabbed by the rhyme and the rhythm.

By the time I had children of my own, we were feasting on books like Judith Kerr's THE TIGER WHO CAME TO TEA, Russell Hoban's unforgettable BEDTIME FOR FRANCES, Eric Hill's SPOT books, Maurice Sendak's WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE, all the MIFFY books, and of course, Pat Hutchin's masterpiece of picture book writing, with its spare 35 (!!) words - ROSIE'S WALK.

Having always published much longer work, including Young Adult novels, in recent years I found myself falling in love yet again with picture books ( there are some splendid contemporary ones), but it was only when I picked up Debi Gliori's NO MATTER WHAT in my GP surgery waiting room that I realised just how much depth of feeling can be expressed in a few simple words and pictures aimed simultaneously at both the child and the adult reader. The theme of her book is simply of 'love, forever, up to and beyond death' (I believe the American version sanitised out the 'death' bit for commercial reasons, thus losing much of the story's depth). Little did I know that, within a month, her gentle and magical words would apply to my own situation.

I've been working on my own picture book texts for the past three years, and believe me, this form of literature is not easy. Like the best poetry, it's challenging and precise. But it's also fun. Two years ago, we were watching the royal wedding on TV, and, naughtily, among the frocks and the hats, I mentally inserted one mouse. This naughtiness was to grow into '...and NOBODY NOTICED the MOUSE', published this month by the lovely people at TopThat! It will be followed, next year, with 'QUICKER THAN A PRINCESS', a book with the theme of gestation and birth. Like I said - although fun, this stuff's serious.

To view more of Enid's work click here. To visit Enid's website click here.

Published on September 17, 2013 23:30

September 12, 2013

Now and Then by Sue Hardy-Dawson (Guest Blog)

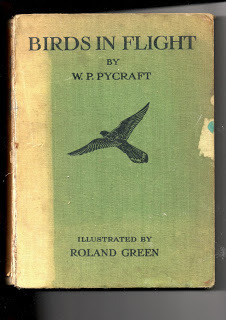

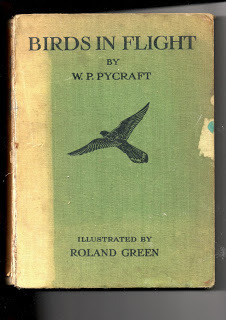

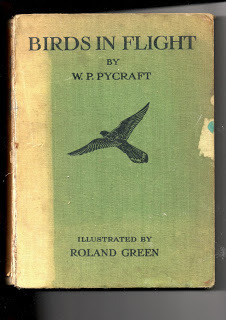

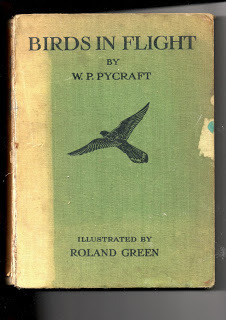

I began collecting books at the age of twelve when a lovely old chap on playground duty gave me a battered ancient bird book with beautiful tissue covered plates.

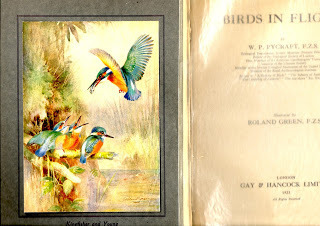

Birds in Flight by W.P.Pycraft, illustrated by Roland Green. 1922

To this day almost nothing is more exciting to me than the smell of foxed paper and a few loose pages. Perhaps I’m strange, but it’s an interesting and relatively cheap hobby and it does tell you a lot about how adults have perceived, or at least made assumptions, about children through the decades. And oh how books have changed from the earliest I own, from the turn of the century, to present day.

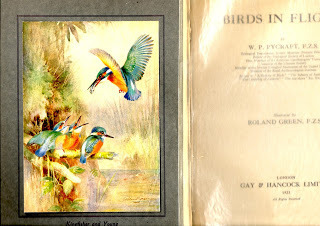

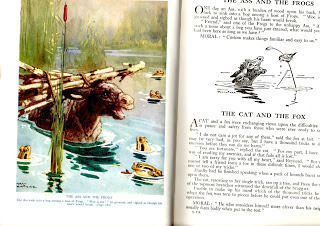

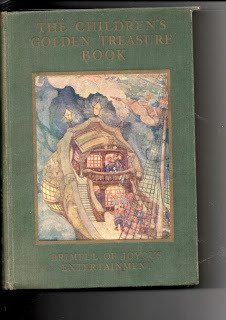

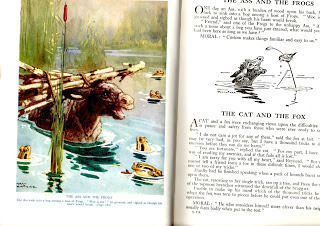

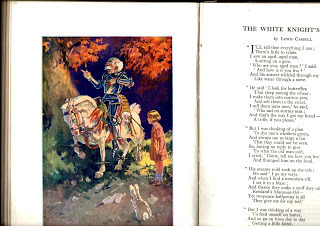

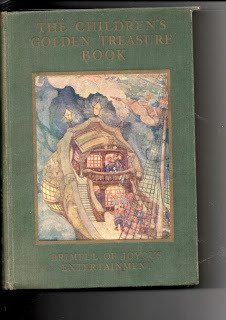

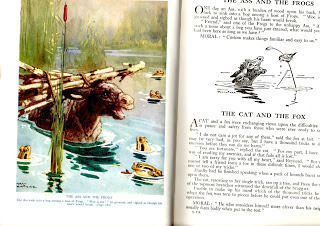

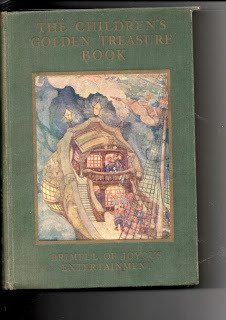

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

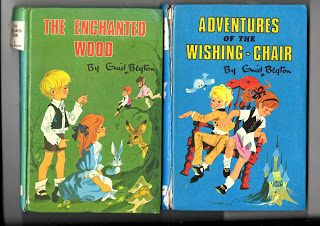

Firstly, the small number of picture books I own seem wordier, aimed at older children than would perhaps read them today. They are also very sedate and the author’s voice very evident as talking to and instructing the child.

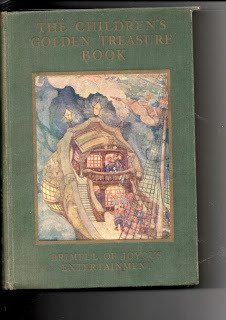

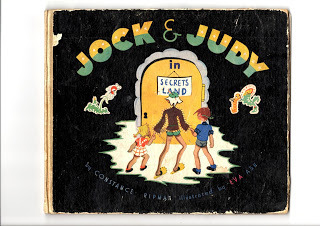

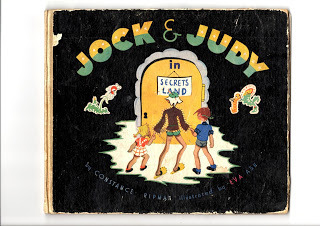

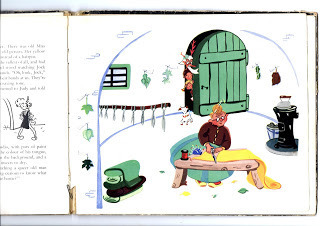

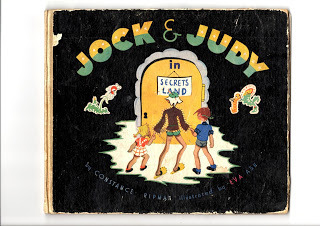

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

Children on the whole had less of everything, even when I was young. I owned perhaps twenty books, some passed down from my parents. I could name them all, even now. Of course I could, they were my most precious possessions.

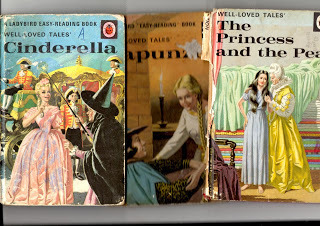

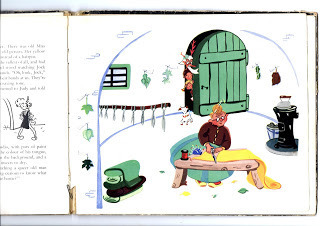

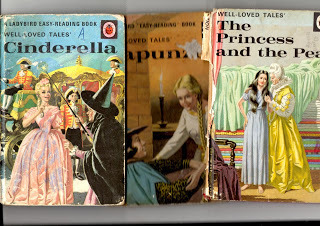

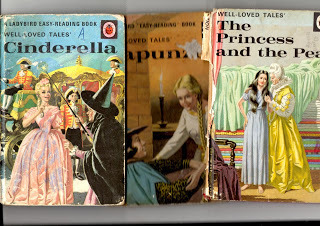

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

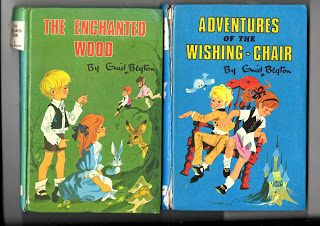

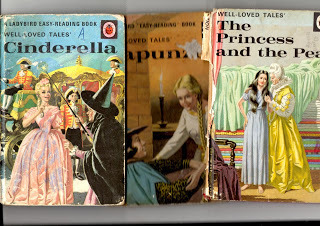

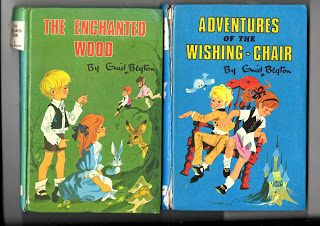

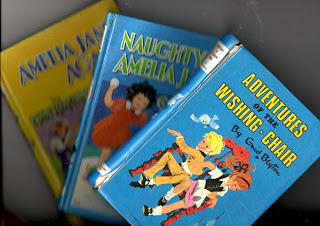

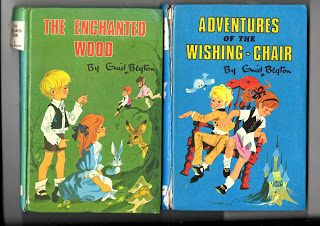

Aged eight I was a big fan of Enid Blyton, much to my father’s dismay; he made no secret of what he saw as their many flaws, however they were my special place to go and as such will always have a place in my heart.

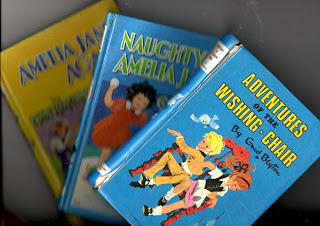

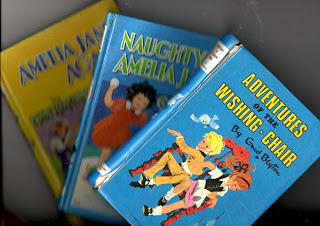

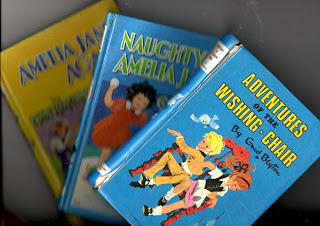

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

Yet what is true of them was true of many of their contemporaries. Children’s books were bristling with good upright members of the public. Moral lessons were the order of the day.

Even when risks were taken there were rules, not unlike the Geneva Convention, about being a decent ‘chap’. Yes I said ‘chap’ because ‘good sorts’ of girls were honouree chaps and this was thought, at the time, a great compliment. Equally villains were thoroughly villainous without extenuating circumstance or redeeming feature.

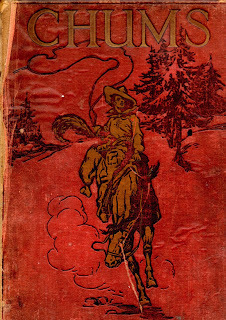

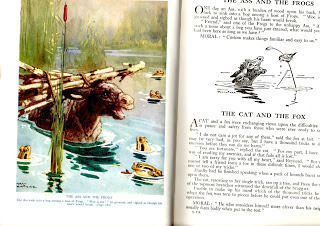

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

I am relieved at the changes that have allowed girls to become stronger characters, not chiefly reliant on boyish gallants for their instruction and protection. Reading through many of my old children’s books retrospectively I can see that they are peppered with stereotypes and even covert or occasionally overt racism; hard to believe but all perfectly acceptable at the time. And yes, I do often cringe when reading some of my old treasures.

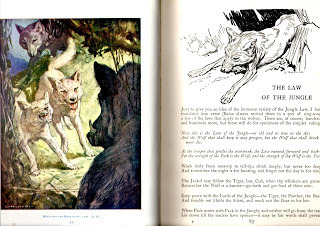

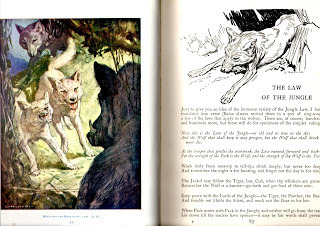

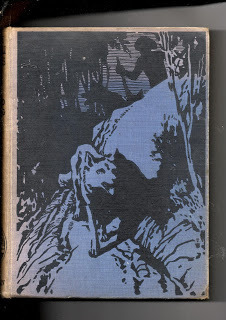

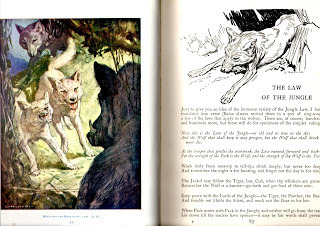

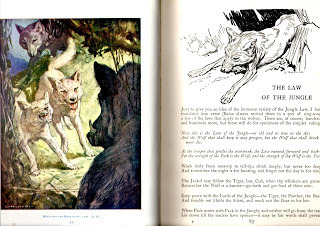

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

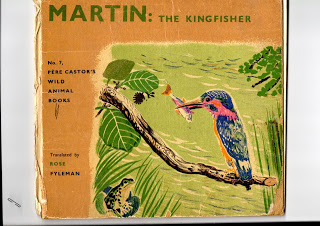

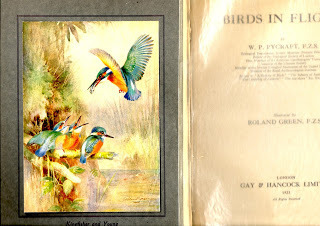

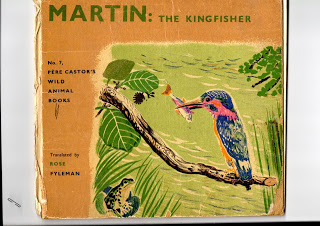

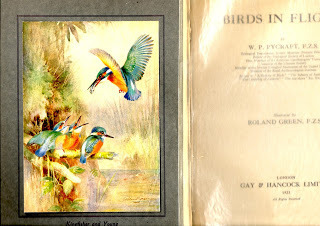

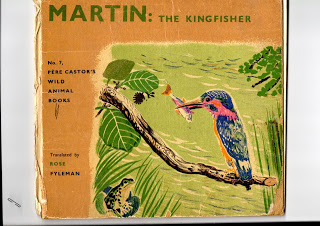

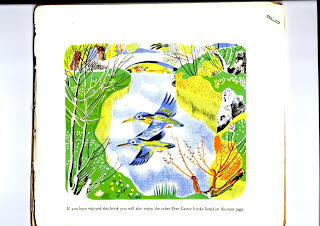

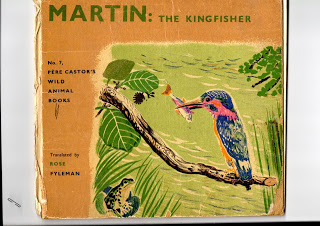

However deeply flawed as they seem to our modern eyes, I think in one sense the best of these books did make children feel safe, much safer than I suspect a lot of children feel today, introduced as they are to all of life’s grim realities at such an early age. My favourite was, and is, the one about a family of kingfishers.

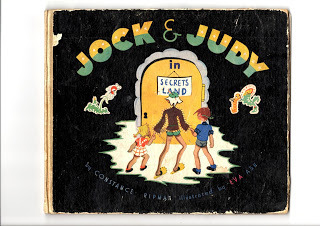

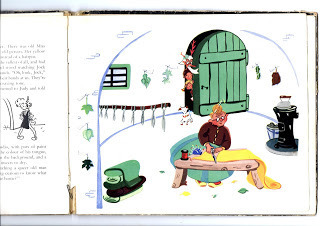

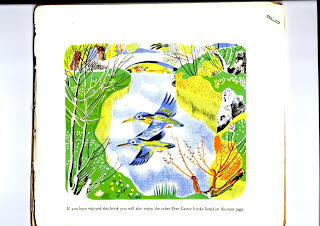

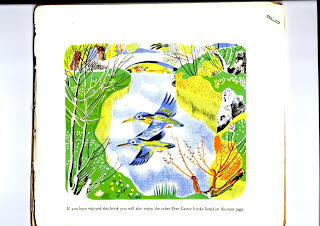

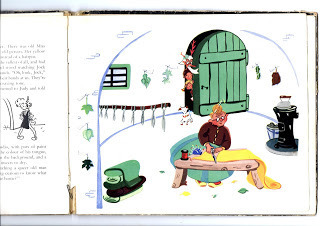

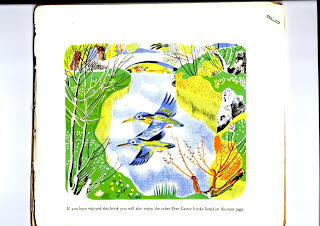

Undated, but presented to my mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Undated, but presented to my mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Writing for children, as with all forms of media, has moved on. Now the choice is immense and far more accessible to children who have a plethora of consumerables to choose from. Unsurprisingly, although my now grown-up children can name their favourite books, they couldn’t even begin to name every book they owned because they had so many. Even at the age of three , they had a much greater sense of self and their own opinions than I would have ever have presumed at their age. Their life experiences and their media experiences were much greater than mine, all be it in a virtual way.

1912

1912

Picture books, like all other books, have evolved massively. They’re more colourful, slicker and in the main punchier than they have ever been and now more than ever they are aimed at the developmental stage of the younger child. However what has not changed, as any parent, or person working with children will tell you, is that the most important thing about any picture book is that it must also appeal to them. As a parent I well remember cringing at having to read some books, whereas others I've read hundreds of times and still think of fondly. I think this is probably why some books have stood the test of time, because they are lovely stories and they have wonderful illustrations and haven’t strayed too far down the path of what today would be considered non PC.

Yet in one sense, there are still no new stories, just new ways of telling them...

Sue Hardy-Dawson is a much published children's poet and illustrator. She has also been a childminder and a classroom assistant and is the mum of three grown-up children. Sue lives in Yorkshire with her family, and one cat, one fish and two Cocker Spaniels. You can find Sue on Blogger by clicking Sue's Link

Birds in Flight by W.P.Pycraft, illustrated by Roland Green. 1922

To this day almost nothing is more exciting to me than the smell of foxed paper and a few loose pages. Perhaps I’m strange, but it’s an interesting and relatively cheap hobby and it does tell you a lot about how adults have perceived, or at least made assumptions, about children through the decades. And oh how books have changed from the earliest I own, from the turn of the century, to present day.

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935Firstly, the small number of picture books I own seem wordier, aimed at older children than would perhaps read them today. They are also very sedate and the author’s voice very evident as talking to and instructing the child.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.Children on the whole had less of everything, even when I was young. I owned perhaps twenty books, some passed down from my parents. I could name them all, even now. Of course I could, they were my most precious possessions.

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric WinterAged eight I was a big fan of Enid Blyton, much to my father’s dismay; he made no secret of what he saw as their many flaws, however they were my special place to go and as such will always have a place in my heart.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.Yet what is true of them was true of many of their contemporaries. Children’s books were bristling with good upright members of the public. Moral lessons were the order of the day.

Even when risks were taken there were rules, not unlike the Geneva Convention, about being a decent ‘chap’. Yes I said ‘chap’ because ‘good sorts’ of girls were honouree chaps and this was thought, at the time, a great compliment. Equally villains were thoroughly villainous without extenuating circumstance or redeeming feature.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.I am relieved at the changes that have allowed girls to become stronger characters, not chiefly reliant on boyish gallants for their instruction and protection. Reading through many of my old children’s books retrospectively I can see that they are peppered with stereotypes and even covert or occasionally overt racism; hard to believe but all perfectly acceptable at the time. And yes, I do often cringe when reading some of my old treasures.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.However deeply flawed as they seem to our modern eyes, I think in one sense the best of these books did make children feel safe, much safer than I suspect a lot of children feel today, introduced as they are to all of life’s grim realities at such an early age. My favourite was, and is, the one about a family of kingfishers.

Undated, but presented to my mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Undated, but presented to my mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Writing for children, as with all forms of media, has moved on. Now the choice is immense and far more accessible to children who have a plethora of consumerables to choose from. Unsurprisingly, although my now grown-up children can name their favourite books, they couldn’t even begin to name every book they owned because they had so many. Even at the age of three , they had a much greater sense of self and their own opinions than I would have ever have presumed at their age. Their life experiences and their media experiences were much greater than mine, all be it in a virtual way.

1912

1912Picture books, like all other books, have evolved massively. They’re more colourful, slicker and in the main punchier than they have ever been and now more than ever they are aimed at the developmental stage of the younger child. However what has not changed, as any parent, or person working with children will tell you, is that the most important thing about any picture book is that it must also appeal to them. As a parent I well remember cringing at having to read some books, whereas others I've read hundreds of times and still think of fondly. I think this is probably why some books have stood the test of time, because they are lovely stories and they have wonderful illustrations and haven’t strayed too far down the path of what today would be considered non PC.

Yet in one sense, there are still no new stories, just new ways of telling them...

Sue Hardy-Dawson is a much published children's poet and illustrator. She has also been a childminder and a classroom assistant and is the mum of three grown-up children. Sue lives in Yorkshire with her family, and one cat, one fish and two Cocker Spaniels. You can find Sue on Blogger by clicking Sue's Link

Published on September 12, 2013 23:30

Now and Then by Sue Hardy-Dawson

I began collecting books at the age of twelve when a lovely old chap on playground duty gave me a battered ancient bird book with beautiful tissue covered plates.

Birds in Flight by W.P.Pycraft, illustrated by Roland Green. 1922.

To this day almost nothing is more exciting to me than the smell of foxed paper and a few loose pages. Perhaps I’m strange but it’s an interesting and relatively cheap hobby and it does tell you a lot about how adults have perceived or at leased made assumptions about children through the decades. And oh how books have changed form the earliest I own, from the turn of the century, to present day.

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and .M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and .M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

Firstly, the small number of picture books I own seem wordier, aimed at older children than would perhaps read them today. They are also very sedate and the author’s voice very evident as talking to and instructing the child.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

Children on the whole had less of everything, even when I was young. I owned perhaps twenty books, some passed down from my parents. I could name them all, even now, of course I could, they were my most precious possessions.

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

Aged eight I was a big fan of Enid Blyton, much to my Father’s dismay; he made no secret of what he saw as their many flaws, however they were my special place to go and as such will always have a place in my heart.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

Yet what is true of them was true of many of their contemporaries. Children’s books were bristling with good upright members of the public. Moral lessons were the order of the day.

Even when risks were taken there were rules, not unlike the Geneva Convention, about being a decent ‘chap’, yes I said ‘chap’ because ‘good sorts’ of girls were honouree chaps and this was thought, at the time, a great compliment. Equally villains were thoroughly villainous without extenuating circumstance or redeeming feature.

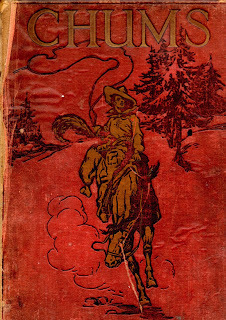

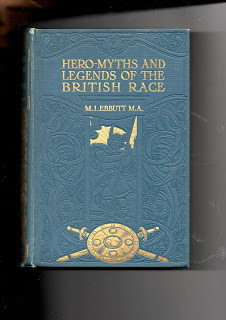

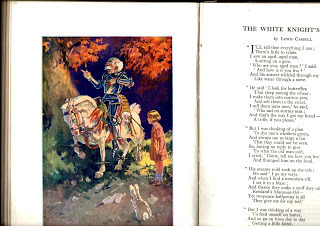

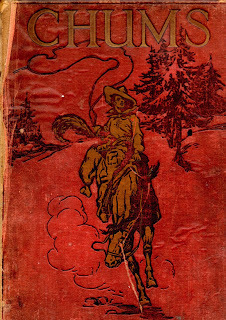

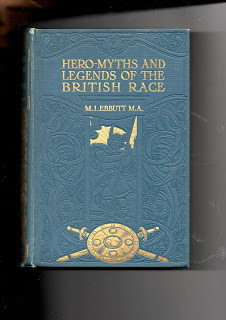

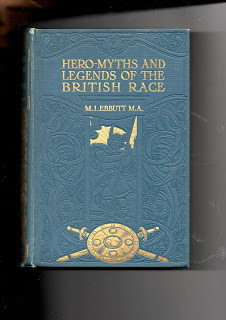

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

I am relieved at the changes that have allowed girls to become stronger characters not chiefly reliant on boyish gallants for their instruction and protection. Reading through many of my old children’s books retrospectively I can see that they are peppered with stereotypes and even covert or occasionally overt racism, hard to believe but all perfectly acceptable at the time. And yes, I do often cringe when reading some of my old treasures.

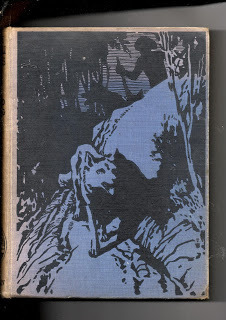

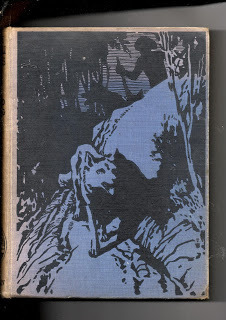

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

However deeply flawed as they seem to our modern eyes, I think in one sense the best of these books did make children feel safe, much safer than I suspect a lot of children feel today introduced as they are to all of life’s grim realities at such an early age. My favourite was, and is, the one about a family of kingfishers.

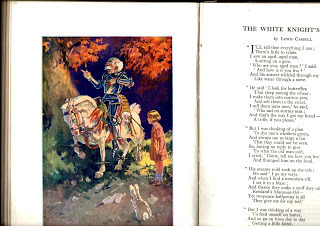

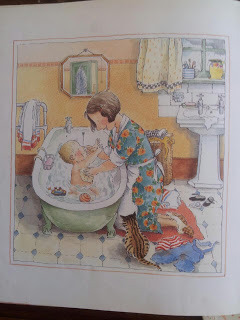

Undated, but presented to my Mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Undated, but presented to my Mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Writing for children as with all forms of media has moved on, the choice is immense and far more accessible to children who have a plethora of consumer-ables to choose from. Unsurprisingly, although my now grown up children can name their favourite books, they couldn’t even begin to name every book they owned because they had so many. Even at the age of three , they had a much greater sense of self and their own opinions than I would have ever have presumed at their age. Their life experiences and their media experiences were much greater than mine, all be it in a virtual way.

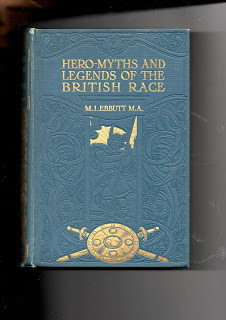

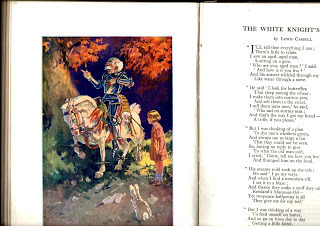

1912

1912

Picture books, like all other books have evolved massively, they’re more colourful, slicker and in the main punchier than they have ever been and now more than ever they are aimed at the developmental stage of the younger child. However what has not changed, as any parent, or person working with children will tell you, is that the most important thing about any picture book is that it must also appeal to them. As a parent I well remember cringing at having to read some books whereas others I’ve read hundreds of times and still think of fondly. I think this is probably why some books have stood the test of time, because they are lovely stories and they have wonderful illustrations and haven’t strayed too far down the path of what today would be considered non PC.

Yet in one sense, there are still no new stories, just new ways of telling them...

Sue Hardy-Dawson is a much published children's poet and illustrator, she has also been a childminder and a classroom assistant and is the mum of three grown up children. She lives in Yorkshire with her family, and one cat, one fish and two Cocker Spaniels. You can find Sue on Blogger by clicking Sue's Link

Birds in Flight by W.P.Pycraft, illustrated by Roland Green. 1922.

To this day almost nothing is more exciting to me than the smell of foxed paper and a few loose pages. Perhaps I’m strange but it’s an interesting and relatively cheap hobby and it does tell you a lot about how adults have perceived or at leased made assumptions about children through the decades. And oh how books have changed form the earliest I own, from the turn of the century, to present day.

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and .M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935

The Children's Golden Treasure Book, edited by John R. Crossland and .M. Parish, illustrator unrecorded, 1935Firstly, the small number of picture books I own seem wordier, aimed at older children than would perhaps read them today. They are also very sedate and the author’s voice very evident as talking to and instructing the child.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.

By Constance Ripman, illustrated by Eva Ash. Undated.Children on the whole had less of everything, even when I was young. I owned perhaps twenty books, some passed down from my parents. I could name them all, even now, of course I could, they were my most precious possessions.

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric Winter

These Ladybird Books are tales re-told by Vera Southgate, illustrated by Eric WinterAged eight I was a big fan of Enid Blyton, much to my Father’s dismay; he made no secret of what he saw as their many flaws, however they were my special place to go and as such will always have a place in my heart.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.

The illustrator of the Amelia Jane books was Rene Cloke, but the names of the illustrators of the other books are not recorded in the books.Yet what is true of them was true of many of their contemporaries. Children’s books were bristling with good upright members of the public. Moral lessons were the order of the day.

Even when risks were taken there were rules, not unlike the Geneva Convention, about being a decent ‘chap’, yes I said ‘chap’ because ‘good sorts’ of girls were honouree chaps and this was thought, at the time, a great compliment. Equally villains were thoroughly villainous without extenuating circumstance or redeeming feature.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.

1922. Assorted authors and illustrators.I am relieved at the changes that have allowed girls to become stronger characters not chiefly reliant on boyish gallants for their instruction and protection. Reading through many of my old children’s books retrospectively I can see that they are peppered with stereotypes and even covert or occasionally overt racism, hard to believe but all perfectly acceptable at the time. And yes, I do often cringe when reading some of my old treasures.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.

All the Mowgli Stories by Rudyard Kipling, illustrated by Stuart Tresilian, 1952.However deeply flawed as they seem to our modern eyes, I think in one sense the best of these books did make children feel safe, much safer than I suspect a lot of children feel today introduced as they are to all of life’s grim realities at such an early age. My favourite was, and is, the one about a family of kingfishers.

Undated, but presented to my Mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Undated, but presented to my Mum in 1949. This is my favourite illustration from it:

Writing for children as with all forms of media has moved on, the choice is immense and far more accessible to children who have a plethora of consumer-ables to choose from. Unsurprisingly, although my now grown up children can name their favourite books, they couldn’t even begin to name every book they owned because they had so many. Even at the age of three , they had a much greater sense of self and their own opinions than I would have ever have presumed at their age. Their life experiences and their media experiences were much greater than mine, all be it in a virtual way.

1912

1912Picture books, like all other books have evolved massively, they’re more colourful, slicker and in the main punchier than they have ever been and now more than ever they are aimed at the developmental stage of the younger child. However what has not changed, as any parent, or person working with children will tell you, is that the most important thing about any picture book is that it must also appeal to them. As a parent I well remember cringing at having to read some books whereas others I’ve read hundreds of times and still think of fondly. I think this is probably why some books have stood the test of time, because they are lovely stories and they have wonderful illustrations and haven’t strayed too far down the path of what today would be considered non PC.

Yet in one sense, there are still no new stories, just new ways of telling them...

Sue Hardy-Dawson is a much published children's poet and illustrator, she has also been a childminder and a classroom assistant and is the mum of three grown up children. She lives in Yorkshire with her family, and one cat, one fish and two Cocker Spaniels. You can find Sue on Blogger by clicking Sue's Link

Published on September 12, 2013 23:30

September 7, 2013

Tatty Old Treasured Picture Books by Jane Clarke

When I was having a clear out, I discovered a cache of much-loved and very worn picture books that are over 25 years old. My sons are about to turn 30 (30! How did that happen?) and 28, so I thought a good way to mark the occasion would be to share a few of my (and hopefully, their) TOTPs.

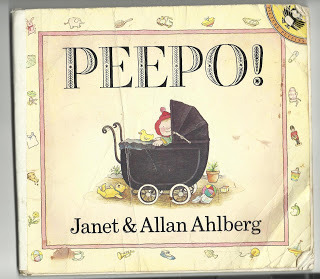

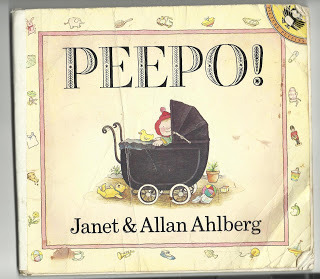

Peepo by Janet and Allan Ahlberg (first published 1981, this copy Picture Puffin 1983)

Crumpled cover, splotched with unidentifiable stains and with corners lightly sucked. Inside, every 'peepo' cut-out is torn and patched due to baby sons enthusiastically swiping every page turn whilst chortling 'peepo!' Spine taped after it dropped to bits, causing tears (mine).

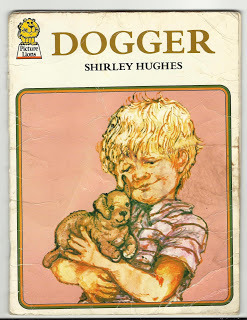

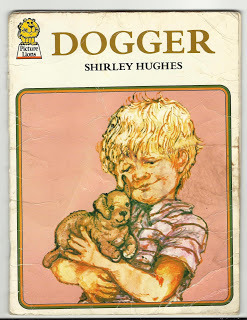

Dogger by Shirley Hughes (Bodley Head 1977)

Inner pages parting company with cover which is ingrained with soil after a particularly exciting Teddy Bears Picnic at the bottom of the garden. Tear drop stains on lost Dogger page. Starting to sniffle, moving on...

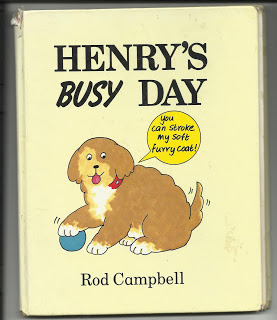

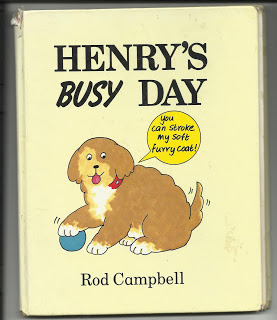

Henry's Busy Day by Rod Campbell (Viking Kestrel 1983)

Gift from Grandma and Grampy. Spine fraying. The 'soft furry coat' of Henry in the last spread still retains hints of something sticky that could be the subject of forensic investigation. Ideal reading for inducing sleep, particularly of the parent reader.

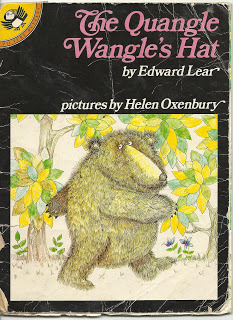

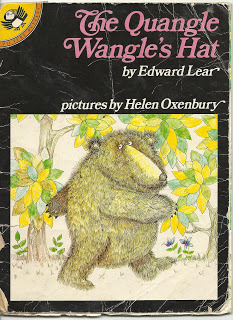

The Quangle Wangle's Hat by Edward Lear, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury (this copy Picture Pufffin 1982)Weirding out sons alert – I read this rhyme so many times to Older Son that I could (and did) recite it like a mantra during the birth of Younger Son. After that, I was less than keen on reading it aloud (owing to flash backs) and it got 'lost' for a while. A quarter of a century or so in fact.

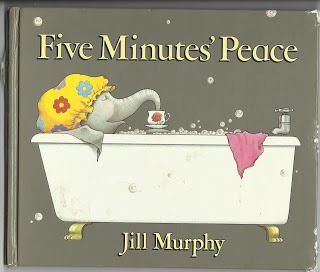

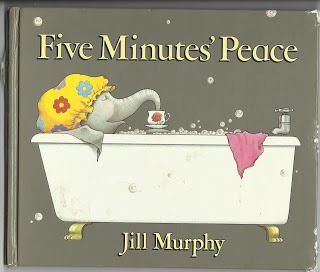

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy (Walker Books 1986)

Edge of cover slightly nibbled by long-gone Rosa and Cynthia the guinea pigs. My (then) small sons failed to understand why Mrs Large could possibly want 'Five Minutes Peace' - but I LOVED this book (and still do). Maybe one day they'll have kids of their own -THEN they'll get it.

Other books come and go (to the charity shop), but these picture books (and a whole heap of others) are so redolent of happy times, I shall keep them forever.

What tatty old picture books do you treasure?

Jane's posts a Tatty Old Treasured Picture Book of the week on her facebook author page, www.facebook.com/JaneClarkeChildrensAuthorand she really hopes some of the picture books she's written will end up being tatty and torn and treasured by someone, too.

Peepo by Janet and Allan Ahlberg (first published 1981, this copy Picture Puffin 1983)

Crumpled cover, splotched with unidentifiable stains and with corners lightly sucked. Inside, every 'peepo' cut-out is torn and patched due to baby sons enthusiastically swiping every page turn whilst chortling 'peepo!' Spine taped after it dropped to bits, causing tears (mine).

Dogger by Shirley Hughes (Bodley Head 1977)

Inner pages parting company with cover which is ingrained with soil after a particularly exciting Teddy Bears Picnic at the bottom of the garden. Tear drop stains on lost Dogger page. Starting to sniffle, moving on...

Henry's Busy Day by Rod Campbell (Viking Kestrel 1983)

Gift from Grandma and Grampy. Spine fraying. The 'soft furry coat' of Henry in the last spread still retains hints of something sticky that could be the subject of forensic investigation. Ideal reading for inducing sleep, particularly of the parent reader.

The Quangle Wangle's Hat by Edward Lear, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury (this copy Picture Pufffin 1982)Weirding out sons alert – I read this rhyme so many times to Older Son that I could (and did) recite it like a mantra during the birth of Younger Son. After that, I was less than keen on reading it aloud (owing to flash backs) and it got 'lost' for a while. A quarter of a century or so in fact.

Five Minutes Peace by Jill Murphy (Walker Books 1986)

Edge of cover slightly nibbled by long-gone Rosa and Cynthia the guinea pigs. My (then) small sons failed to understand why Mrs Large could possibly want 'Five Minutes Peace' - but I LOVED this book (and still do). Maybe one day they'll have kids of their own -THEN they'll get it.

Other books come and go (to the charity shop), but these picture books (and a whole heap of others) are so redolent of happy times, I shall keep them forever.

What tatty old picture books do you treasure?

Jane's posts a Tatty Old Treasured Picture Book of the week on her facebook author page, www.facebook.com/JaneClarkeChildrensAuthorand she really hopes some of the picture books she's written will end up being tatty and torn and treasured by someone, too.

Published on September 07, 2013 23:30

September 3, 2013

The Inspiration For My Story - Group Post Part One

Have you ever wondered where the inspiration for a story comes from?

Well we've decided to share what inspired us to write one of our picture books.

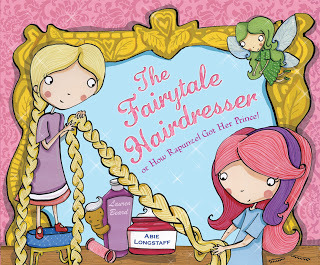

Abie Longstaff

Most of my inspiration comes from games I used to play with my younger sisters. I am one of six girls and, as the eldest, it was my job to keep all the younger ones busy. We played all kinds of imagination based games; like hairdressers, doctors, schools, lost children or mountain climbers. We used to pull apart the sofa cushions and build towers of cushions to make palaces and hills and forts. When I had my own children, the memory of all those games came flooding back to me. The Fairytale Hairdresser series is based on our salon we used to have, where we washed all our dolls' hair. We loved the business side of it too, and would make pretend money to pay, and our own 'shampoo' out of leaves in the garden.

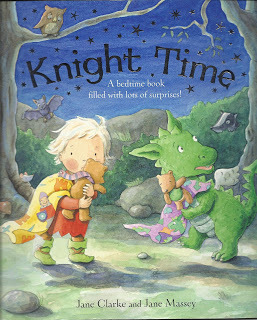

Jane Clarke

Sometimes there’s a long, long gap between inspiration and book! Knight Time is a story of friendship across cultures and it came about because my two boys were lucky enough to be educated from the age of 4 to 18 at Antwerp International school, a melting pot of different nationalities. The parents eyed each other a bit warily, but the kids just got on with being friends. It was years later when it occurred to me that I could write a story about a Little Knight and a Little Dragon who start off being afraid of each other but discover they have more similarities than differences and become great friends. How old is Robert now? 27!

Lynne Garner

My first picture book idea came from the work I do with a local hedgehog rescue centre. Hedgehogs that are too small to hibernate stay in a warm shed and enjoy an extended summer. Those who are fit enough and over 600 grams are encouraged to hibernate in a dry, sheltered hutch. I often wondered what they dreamt about. I also felt a little sorry for them because they miss the wonders of winter. The cold mornings where your breathe plays in the air, the crunch of fresh snow underfoot and the seasonal celebrations. The idea for my story was born. But how to write it? Perhaps a diary? That was it! A friend of a hedgehog writes him a diary. So Teasel the mouse was born and missed his friend so much that he wrote 'A Book For Bramble.'

Pippa Goodhart

The inspiration for Little Nelly's Big Book of Knowledge was my father-in-law teasing his grand-children by 'proving' that George, the Golden Retriever, was a hamster rather than a dog. Grandpa had taught zoology at Cambridge so knew a thing or two about animals. Hamsters are golden, as was George, was the one bit of proof, and I can't remember the rest, but that led me to inventing a small lost elephant (with the tell-tale name of Little Nelly) who looks in a book to find out what she is. She sees in the book that mice have big ears and thin tails and can be grey in colour, so she then 'knows' that she is a mouse ... which of course leads on to interesting times when she tries to go and live with other mice. Thank you, Grandpa Charles!

Now we've shared what inspired us. If you're a writer we'd love to know what inspired you to write one of your books?

Well we've decided to share what inspired us to write one of our picture books.

Abie Longstaff

Most of my inspiration comes from games I used to play with my younger sisters. I am one of six girls and, as the eldest, it was my job to keep all the younger ones busy. We played all kinds of imagination based games; like hairdressers, doctors, schools, lost children or mountain climbers. We used to pull apart the sofa cushions and build towers of cushions to make palaces and hills and forts. When I had my own children, the memory of all those games came flooding back to me. The Fairytale Hairdresser series is based on our salon we used to have, where we washed all our dolls' hair. We loved the business side of it too, and would make pretend money to pay, and our own 'shampoo' out of leaves in the garden.

Jane Clarke

Sometimes there’s a long, long gap between inspiration and book! Knight Time is a story of friendship across cultures and it came about because my two boys were lucky enough to be educated from the age of 4 to 18 at Antwerp International school, a melting pot of different nationalities. The parents eyed each other a bit warily, but the kids just got on with being friends. It was years later when it occurred to me that I could write a story about a Little Knight and a Little Dragon who start off being afraid of each other but discover they have more similarities than differences and become great friends. How old is Robert now? 27!

Lynne Garner

My first picture book idea came from the work I do with a local hedgehog rescue centre. Hedgehogs that are too small to hibernate stay in a warm shed and enjoy an extended summer. Those who are fit enough and over 600 grams are encouraged to hibernate in a dry, sheltered hutch. I often wondered what they dreamt about. I also felt a little sorry for them because they miss the wonders of winter. The cold mornings where your breathe plays in the air, the crunch of fresh snow underfoot and the seasonal celebrations. The idea for my story was born. But how to write it? Perhaps a diary? That was it! A friend of a hedgehog writes him a diary. So Teasel the mouse was born and missed his friend so much that he wrote 'A Book For Bramble.'

Pippa Goodhart

The inspiration for Little Nelly's Big Book of Knowledge was my father-in-law teasing his grand-children by 'proving' that George, the Golden Retriever, was a hamster rather than a dog. Grandpa had taught zoology at Cambridge so knew a thing or two about animals. Hamsters are golden, as was George, was the one bit of proof, and I can't remember the rest, but that led me to inventing a small lost elephant (with the tell-tale name of Little Nelly) who looks in a book to find out what she is. She sees in the book that mice have big ears and thin tails and can be grey in colour, so she then 'knows' that she is a mouse ... which of course leads on to interesting times when she tries to go and live with other mice. Thank you, Grandpa Charles!

Now we've shared what inspired us. If you're a writer we'd love to know what inspired you to write one of your books?

Published on September 03, 2013 05:31

August 28, 2013

Getting to the heart of a picture book - Linda Strachan

How do you get to the heart of a picture book text? I think the automatic reaction is to think a picture book must be in rhyme. When you read some of Julia Donaldson's wonderful rhyming stories they look so simple and work so well that it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that they are easy to write.

How do you get to the heart of a picture book text? I think the automatic reaction is to think a picture book must be in rhyme. When you read some of Julia Donaldson's wonderful rhyming stories they look so simple and work so well that it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that they are easy to write. It could not be further from the truth.

So what is the problem with rhyme? (Aside from publishers often telling writers that they are not keen on rhyme because it can be harder to sell co-editions, sometimes citing the problems with translation as the reason.)

But often the problem is that the writer becomes so captivated with the idea of making every line or alternate line rhyme that they force the story out of shape, using words that would never otherwise be in the text, simply because they fit the rhyme.

That means they are probably starting in the wrong place.

That means they are probably starting in the wrong place.It is almost like trying to ice a cake before you have baked the sponge mixture.

First you need to think about the story. That is the heart of a picture book. Some writers like to know the ending first, so that it is as strong as the beginning. If the story comes full circle bringing the answer to the problem posed at the beginning, perhaps with an unexpected twist, so much the better.

Ask yourself, what is the story about? A picture book is not just a poem or a lot of rhyming words, there has to be some reason to tell the story in the first place.

The heart of almost any book is the characters and what happens to them. Why do we care about them? What is the problem they must solve, what exciting journey are they embarking on?

There have been several posts here on Picturebook Den discussing ways to start writing a picture book. Such as this post by Lynne Garner, talking about pace in a picture book and thinking about the story working over the length of the book.

There have been several posts here on Picturebook Den discussing ways to start writing a picture book. Such as this post by Lynne Garner, talking about pace in a picture book and thinking about the story working over the length of the book.It is a good way to start.

It made me smile when I heard Julia Donaldson yesterday morning on TV talking about starting a book and thinking about it being approx 12 double page spreads.

Once you have your story idea and have thought about the characters you might have already started writing the story (I am not much of a planner when I am writing a novel but I find picture books work better with this kind of framework in mind).

The words you use in a picture book will probably need to be refined and changed, moved about, used in a different way. It is quite amazing ow many ways you can say the same thing.

A previous post by Jonathan Allen looks at titles for picture books and shows how the words or expressions can make something either stand out or sound really boring.

I think that each line in a picture book should be examined to make sure it works well, that it keeps the story going, sounds like fun, and is the best use of words in that particular place.

I think that each line in a picture book should be examined to make sure it works well, that it keeps the story going, sounds like fun, and is the best use of words in that particular place.Finding the right word is about making the text easy to read, with words that don't trip up the person reading it out loud, about having rhythm and making the story exciting, and engaging both child and parent.

After all these considerations you might decide that it will work better with some kind of rhyme, perhaps now and then, but only do this if it falls naturally and fits with all the other considerations above. The rhyme is the least important part, many picture books work better without any rhyme at all, and it should only be used if it absolutely works with the story, fits in with the rhythm and without using archaic or odd language to make the rhyme work.

I've just come back from tutoring a week long residential course for the Arvon Foundation in lovely Moniack Mhor, near Inverness in Scotland, with co-tutor the author and illustrator Teresa Flavin. We discussed different aspects of writing for Children with the 16 enthusiastic and hardworking writers on the course.

I've just come back from tutoring a week long residential course for the Arvon Foundation in lovely Moniack Mhor, near Inverness in Scotland, with co-tutor the author and illustrator Teresa Flavin. We discussed different aspects of writing for Children with the 16 enthusiastic and hardworking writers on the course. Talking about writing picture books was only a small part of the week although it could merit an entire week by itself! It is a complex and diverse subject as all the posts on this blog show.

So if you are thinking about starting to write a picture book make sure you get to the heart of the story.

Linda Strachan is the award winning author of over 60 books for all ages, from picture books to YA novels, and writing handbook Writing For ChildrenWebsite www.lindastrachan.comBlog BOOKWORDS

Published on August 28, 2013 23:30

August 23, 2013

The Wonder of Picture Books by Abie Longstaff

We all know the snuggly, cosy effect of picture books. They are designed to be shared and bonded over; adult and child leaning in together in a moment of comfort and joy.

But, as well as these snuggly qualities, did you know that picture books can promote language development, literacy and social skills?

‘Dialogic book reading’ is a style of shared reading where the parent interacts with the child, talking about the illustrations and asking questions about the story. This kind of activity encourages the child to think beyond the story, to relate the pictures to their everyday life and to make sense of their world.

So, as parents and carers, how should we read to our children?

Research suggests we should encourage the child to participate in the reading process by asking questions, even at a young age.

From Bye Bye Baby by Janet and Allan Ahlberg Ask questions about physical things: What do you see? Where is the baby? What toys does he have?

From Bye Bye Baby by Janet and Allan Ahlberg Ask questions about physical things: What do you see? Where is the baby? What toys does he have?

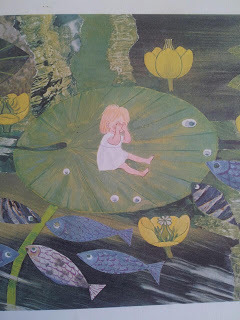

From Thumbelina by Hans Christian Anderson, Kaj Beckman and M.R. James

From Thumbelina by Hans Christian Anderson, Kaj Beckman and M.R. JamesAsk about feelings to help the child express themself: The girl looks sad, why is she sad? Are the fish going to help her?Let the child ask you questions too.Feed back to the child; praising them when they notice something in the story. Don’t forget the illustrations in this respect. If a child is decoding a story simply from the pictures, praise this as much as when the child reads a word in the text.

From Princess Smartypants, by Babette ColeAdapt the reading style to the child’s growing linguistic abilities. For older children picture books can be used to discuss more complicated issues: Why doesn't Princess Smartypants want to get married? Do you like this ending? Can you imagine another giant pet for her?

From Princess Smartypants, by Babette ColeAdapt the reading style to the child’s growing linguistic abilities. For older children picture books can be used to discuss more complicated issues: Why doesn't Princess Smartypants want to get married? Do you like this ending? Can you imagine another giant pet for her?

From Where the Wild Things are, by Maurice Sendak Move beyond the text and relate the story to the child’s life: Would you like a boat like that? You like costumes too!

From Where the Wild Things are, by Maurice Sendak Move beyond the text and relate the story to the child’s life: Would you like a boat like that? You like costumes too!  From Possum Magic, by Mem Fox Talk about culture: What kind of animals are these? Can you think of any other Australian animals? Would you like to live in Australia? Recent research has found that even picture books with very few words can encourage language development in two-year olds. A study by Manchester University revealed that when parents share very simple books with their child, the language the parent uses contains more complex constructions than everyday speech. This helps the child learn a wider vocabulary, grammar and even enhances their maths, as one of the key predictors in children’s mathematical skill is early language experience.

From Possum Magic, by Mem Fox Talk about culture: What kind of animals are these? Can you think of any other Australian animals? Would you like to live in Australia? Recent research has found that even picture books with very few words can encourage language development in two-year olds. A study by Manchester University revealed that when parents share very simple books with their child, the language the parent uses contains more complex constructions than everyday speech. This helps the child learn a wider vocabulary, grammar and even enhances their maths, as one of the key predictors in children’s mathematical skill is early language experience.But, as Monty Python would ask; other than vocab, grammar, maths, sharing, expressing emotion, cultural values, and bonding, what have picture books ever done for us? Well, if that list wasn’t enough…

...A study found those children who are read a picture book before having blood taken feel less pain.

More information For tips on dialogic reading, see http://www.readingrockets.org/article...

For information on language development and picture books, see http://www.manchester.ac.uk/aboutus/n...

For more on pain management and picture books, see A Prospective Randomised Control Study: Reduction of Children's Pain Expectation Using a Picture Book during Blood Withdrawal Zieger B. et al (2013) Klin Padiatr; 225(03): 110-114

Published on August 23, 2013 23:00

August 19, 2013

The Thing That You Call It In Not Many Words That Kind of Says What it is and All That... by Jonathan Allen

In the online and other public discussions about what makes a successful picture book, that authors and other denizens of the publishing world have from time to time, the subject of titles doesn’t come up perhaps as often as it should.

The title is the first piece if information you get about a book and as such, what it conveys in the few words it has at its disposal is as important as it is disproportionate. In the case of a picture book especially, it can sum up the entire concept, the tone of voice, the feel and the probable purpose or intention of the publication in less than ten words. That’s powerful stuff!

It needs to grab the attention and be memorable, like a newspaper headline, or a pop song title. It has to make you want to find out more, and most importantly and difficult-to-define-ably of all, it has to be 'right'. Sometimes the process of getting a title 'right' can involve much too-ing and fro-ing between an author and a publisher (incorporating much input from the marketing dept) before everyone is happy, and at other times the title can be the thing that triggers the idea for the book in the first place.

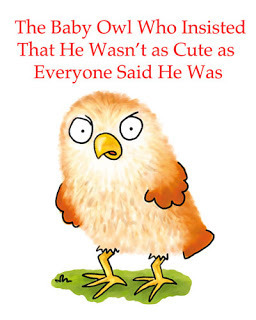

To be boringly self referential for a minute, my picture book ’I’m Not Cute!’ is a good example of what a title can 'tell' you. The whole concept of the book is encapsulated in the title. A character claiming not to be cute. That should grab the attention because picture book characters are pretty much universally cute, so what bizarre heresy is being conducted here? Picture book characters are not usually given room or opportunity to give their opinion of their perceived cuteness, so for one to speak out and refute this perception is unusual and worthy of investigation. So with 'I'm Not Cute!', in three words we get a concept, a tone of voice and a slightly anarchic feel, not to mention an insight into a character's, and by association, an author's personality. And that's before you get to see the pictures.

Think of your favourite picture book titles (or children’s fiction titles) and see whether they conform to my thesis. Here are some off the top of my head.

Farmer DuckThe Wind in The WillowsWhere The Wild Things AreTom All AloneThe Magic PuddingFive Children and ItThe Man Whose Mother Was A PirateEtc.

Well, that kind of bears me out. You would want to seek them out based on the titles.

The interesting thing is that some successful books have pretty prosaic,

bland names which largely disregard ’the rules’. .

The Jungle BookNonsense SongsFireman SamThomas The Tank Engine

But I guess they indicate what you are going to get.

Some are just deliberately and brilliantly wordy, like 'How Tom Beat Captain Najork and his Hired Sportsmen.'

A fun thing to do in a spare moment, if you have such a thing, is to take an interesting, snappy title and make it as prosaic as possible, to see if you would have given it the time of day under this boring guise.

How about - Max has a Dream About Monsters.The Ring That Everybody Wants.Would You Like to Try Sam’s Unusual Meal?Potty Training an Unwilling Princess is Difficult.Craig Thompson and The Philosopher’s StoneThe Little Girl Who Went Through The MirrorEtc etc

Instant classics?

Now you have a go.

Published on August 19, 2013 00:30

August 13, 2013

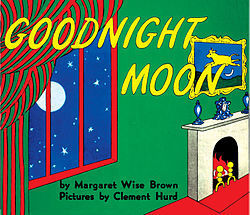

What Is The Magic Of 'Goodnight Moon'? By Pippa Goodhart

There are some picture books which just work. Children ask for them to be read, and they look at them by themselves, over and over again, and it isn’t always obvious exactly what the attraction of those books is. Sometimes it’s a personal attachment in one child to a particular book, but sometimes the appeal appears to be universal. One picture book which has worked for generations of children throughout the world is ‘Goodnight Moon’.

But why does it work so well?

American teacher Margaret Wise Brown, author of over a hundred books, wrote the simple text in this book which will be familiar to lots of you –

‘In the great green room

There was a telephone

And a red balloon

And a picture of –

(turn the page)

The cow jumping over the moon’ etc.

Clement Hurd created the rather crude repetitive pictures in primary colours of the odd room with a burning fire, a rabbit lady knitting in her rocking chair, the kittens and mittens, the telephone, the bowl full of mush, the comb and the bowl of much. The book was published in 1947 and has sold over twelve million copies in at least fourteen different languages in the sixty-six years since.

I used the book with my own children, and there truly isn’t a better one for winding a small child down to sleepiness. The text is rhythmic and rhyming and repetitive. Those ‘three ‘r’s’ are well known ingredients for a pleasing read out loud for young children, of course. But here the rhythm and rhyme and repetition seem to be a substitute for story rather than a treatment of it. There simply is no plot; no story. This is just one small rabbit’s goodnight ritual. It is dull dull dull. Can you imagine a present day publisher accepting a page that is entirely blank of illustration, accompanied by the text ‘Goodnight nobody’?! There is some small interest in spotting where the mouse and named objects are, but I think that it is the overall lack of story stimulus that makes the book so successfully soporific.

And yet this book has been chosen by polls of teachers as one of their top hundred children’s books of all time. Why would a teacher use a book that so clearly sends children to sleep? Is there some other quality, beyond the hypnotic sleepifying one, that I am missing? And why had I never before heard of the ‘companion’ book, ‘My World’, published by the same pair a couple of years after ‘Goodnight Moon’ proved such an instant hit? Why isn’t that book as famous as the first one?

Is there some magic ingredient in ‘Goodnight Moon’ which I should be aiming to emulate in my own books? Any suggestions welcome!

Footnote: There’s an extraordinary true story attached to the fictional story of ‘Goodnight Moon’. Margaret Wise Brown, dying unexpectedly of an embolism aged only forty-two, bequeathed the royalties from ‘Goodnight Moon’ to her nine year old neighbour, Albert Clarke. To read what happened then to both the book and the boy, read http://www.joshuaprager.com/articles/...

Published on August 13, 2013 16:30