Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 4

November 18, 2023

Picture books – not just for children (with Mini Grey)

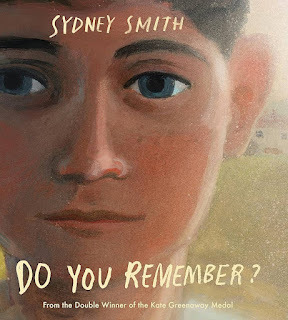

It always looks like picture books spring into being perfectly formed, so it's fascinating to see the journey of bringing a picture book into existence, and lately I've been lucky enough to sit in on the brilliant Just Imagine's An Audience with... featuring Sydney Smith. So today I want to show you a bit of the book he talked about, plus a bit of Jon Klassen's latest book The Skull, and wonder about who these books are really for.

Do YouRemember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithWe're in the dark, close up, with a boy and his mum in bed, and they start playing a game of Do You Remember.

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithWith the first memory we're in the summer countryside with a blue checked picnic rug.

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithThe memories feel swiftly painted, and the first blob in the grass - that's our boy hunting for berries. The fragments have the feel of remembering, before the page turns and there's the whole picnic from the boy's point of view.

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithBelow is one of Sydney Smith's sketches for that scene.

by Sydney Smith

by Sydney SmithHere's the remembered night of the storm - but there's more disruption going on than just a storm...

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithThe boy and his mum look out into the stormy garden and his new red bike and the blue checked picnic blanket are being ravaged outside.

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithWe can wonder about weather and lightreflecting inner turmoils and there's been some great thunderclap and their lives are going to change.

Here are some of the sketches Sydney showed at An Audience with - capturing a mood, a memory, in landscapes.

by Sydney Smith

by Sydney Smith by Sydney Smith

by Sydney Smith

by Sydney Smith

by Sydney SmithThe boy and his mum leave for the city, leaving the dad behind. Here's a sketch of city driving - I love the zinging red light blobs.

by Sydney Smith

by Sydney SmithHere's the scene in the book:

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithThe bear is a gift from the boy's dad, who they have left behind, to start again, just the two of them in the city. So where we started, the mum saying "Do you remember?" in the darkest time of the night, is maybe a night of not sleeping because of huge change and upheaval. Punctuated through the memories we see the boy and the mum in bed, as the first dawn light starts to fall on them, and the sun comes up on a new day. .

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith...and then we see what they've been watching emerge from the gloom through the night:

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith...and then we see what they've been watching emerge from the gloom through the night:

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithAll the things they've brought with them from the country: that blue checked rug, the bike that is always slashes of the brightest red, the oil lamp from the storm: all the memories.

It was amazing seeing the quantity of paintings Sidney Smith made as he was discovering the book he was trying to make, inching towards a sort of crystallization of memory with landscape and mood to tell a story of family break up, but central to it is the boy and his mum, trying out being just the two of them together. The last image is them together, but it's framed as a memory would be, and it feels like the author is reaching in from the future to show this too will be what he remembers.

From Do You Remember by Sydney Smith

From Do You Remember by Sydney SmithAnd now, to a Tyrolean Folktale retold.

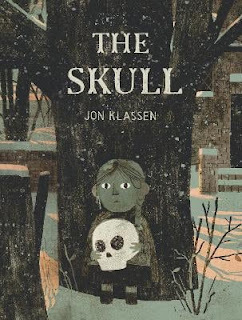

The Skull by Jon Klassen

Jon Klassen is the masterof the impassive face, the baleful eye. The Skull opens with Otilla running through the darkness. One night, in the middle of the night, when everyone else was asleep, Otilla finally ran away. We never know for sure what she's running away from, but that 'finally' seems to be important.

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon KlassenHere's Otilla after she's tripped and fallen and had a good cry. Now she has done crying, and a light of hope is falling on her face, from the sun rising behind a massive mansion she has come across. And living in that mansion is a disembodied skull.

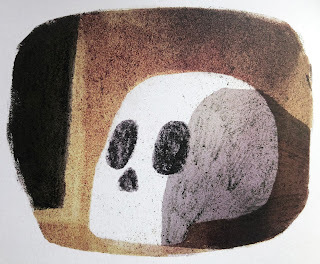

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon Klassen The skull is an interesting challenge: how to make an impassive skull into something we can care about. Suddenly coming across a skull - especially an alive one - would utterly fill me with terror. But this skull has no visible teeth or separate jaw, and what this does is take away the tendency skulls have to grin, this makes it into a quiet reflective sort of skull. The skull absolutely looks the same all the way through, but it is what the skull says that make it an endearing skull. Here below is the skull 'drinking' tea, and really enjoying the tea even though it has run through him out onto the chair. The blankness of the skull means all this hope and tea-enjoyment and vulnerability can be projected onto him.

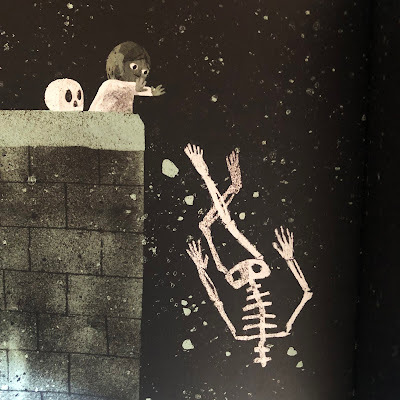

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon KlassenThe skull needs Otilla, and it turns out he is visited nightly by a terrifying headless skeleton. Otillatakes a terrible final vengeance on the skeleton, smashing it to pieces, burning it up, and then sinking the ashes in a bottomless well, in utter cathartic total destruction. Has this helped destroy what she's been running from too? Otilla’s resourcefulness,tender tea-making and ruthless brutality towards headless skeletons is admirable. The story is thrillingly dark and scary, and also has a skull as an unlikely hero.

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon KlassenBut when you finish this book there are manyquestions. Who was the headless skeleton? Was the skull once part of the skeleton? Why didn’tthe skull want to be reunited with the skeleton? What would have happened if the skull and skeleton got joined back together again? What was Otilla running awayfrom? Will she ever go home? And I love a book that leaves you with questions,a story that is a bit unresolved. As you walk down to catch the bus you can have a reallygood ponder about it, the story sticks around because your mind isn't finished with it, and it makes you want to talk about it to someone else.

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon KlassenSo, who are these books really for?

Both of these books are byauthor/illustrators and the pictures are doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Do You Remember is like a work of autobiography, capturing the feelings of memory using light and colour to evoke a mood, a moment, with loose paintwork. It's not in full focus and that unresolvedness makes images feel momentary, but also there's room for our imaginations to come in and do some of the resolving. There's also space for us to wonder what happened and why the boy and his mum had to move and start anew.

The Skull takes us into a dark and scary place with Otilla. I loved going there, and I think it's a brilliant exploration of the scary and perfect for an audience of children and everyone else too. Words, in The Skull, do as much work as the pictures and are beautifully understated. Also, it turns out this book is a bit about memory too, because it started in a library in Alaska, where Jon found a story called 'The Skull'. The story haunted him afterwards and he kept thinking about it. Eventually he wrote to the libary in Alaska and he got to find the story and read it again. And then discovered that in the mean time, his mind had rewritten it for him into something completely different.

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon KlassenReadingpictures is something that people of all ages can do. I think picture books are special because there’s no other way of telling astory that has the same powers. These books couldn’t say what they need tosay in any other format. The story of the pictures is deep and open-ended andresonant and being conjured by our imaginations.

From The Skull by Jon Klassen

From The Skull by Jon Klassen Our education system always ranks words higher than pictures; the words are serious, the pictures are decorations. If the pictures are serious, then it's Art and that belongs in a art lesson. Pictures: we can be looking into them with as much curiosity and insight as we would bring to literature.

My two barometer questions of my favourite picture books are: Is it for everybody, are all welcome? And: When you get to the end, do you feel like you've been taken somewhere utterly else? Been lost spellbound in the picture book's world? The book is a door into another world - to being transported, being taken into someone else's interior world, sharing what it feels like to be someone else.

Picture books have inclusivity - for everyone, but especially for children. Picture books allow older children instant access, to plunge straight in to the story even if they are not a fluent reader. Pictures are always open to your own interpretation, there's no right answer, so pictures are a very good thing to discuss - so readers can be expert Picture Book Detectives, readers of pictures.

The Skull and Do You Remember both have a sort of openness at the heart. We never know what Otilla is running from or how the bodiless skull came to be. The events that lead to the boy and his mum starting a new life in Do You Remember are also not spelled out, they are available for us to wonder about. The central issues that brought the characters to where they find themselves are a bit of a mystery, and open for us to ponder.

A strange surreal image from Paradise Sands, by Levi Pinfold

A strange surreal image from Paradise Sands, by Levi PinfoldSo who's it for? Maybe that's the wrong question, Maybe the reason why something is a picture book, is that a picture book was what the maker needed to make in order to tell the story they wanted to tell. So the question was "How can I tell my story?" and a picture book was the answer.

Picture books are a special unique format for telling a story where ALL are WELCOME - but if the books have to sit on a shelf marked 'for children' everyone else thinks they're not for them.

Last week Julia Donaldson was on Radio 4 - with the excellent help of Frank Cottrell Boyce - lamenting the poor coverage children's books get in the press and on radio. What are thought of as Children's Books get put on a far dusty shelf and people who like reading what are thought of as Children's Books feel vaguely embarrassed.

Maybe that's because of the label, and if we could see picture books especially as not exclusively for children they could get a bit more notice.

November 12, 2023

Eight Resources to Help You Write a Great Picture Book - Lynne Garner

I've been a writer and teacher (adults) for just over 25 years. I believe learning is a life long journey and that's why I've always encouraged my students to continue to learn. So, with this in mind I've put together a list of eight resources you may find helpful with learning how to write a great picture book.

One:

Penguin publishing has a features section on their website. Yes, some of the features are plugging their books. However, there are features that are also educational. One written by author Alan Durant (click on this link to read it) provides a helpful list of five things to consider when writing a picture book.

Penguin publishing has a features section on their website. Yes, some of the features are plugging their books. However, there are features that are also educational. One written by author Alan Durant (click on this link to read it) provides a helpful list of five things to consider when writing a picture book.

Two:

Another great resource is The Book Trust. This charity is the UK's largest children's reading charity. Their aim is to get children reading. Each year they reach millions of children across the UK with books, resources and support to help develop a love of reading. If you click on this link you will be taken to their picture book writing page. It contains a wealth of knowledge for writers of all ages. Perhaps start your journey by reading author Joyce Dunbar's 'Guide to Writing Picture Books.'

Julia Donaldson - children's author

Julia Donaldson - children's author Three: If you have the money to invest in your learning then the BBC run courses created by people top in their field and includes Julia Donaldson. A single course costs £79 or you can sign up for a year at a cost of £10 per month and gain access to all of their courses. Once you've studied how to write a picture book then perhaps explore how to write comedy to help you write funny picture books. Or perhaps poetry to help you write a rhyming picture book. To find out more click on this link.

Four:

Picture books are different from other books. They conform to page counts (this is cost driven). The words support the images and the images the words. When you understand how important this is and how it works it will help you write a picture book which flows across the pages. The post written by children's author Tara Lazar if one of the best I've come across. Click here to read it.

Five:

This article on Reedys (provide services to authors) gives tips on how to write your picture book and what questions to ask yourself. It also breaks down the different age groups that picture books are aimed at. Plus the difference between being traditionally published and publishing yourself. Again, simply click on the link to read the article.

Six:If you prefer to go old school and read a book then there are three books which I highly recommend written by children's author Eve Heidi Bine-Stock. They are:How to Write a Children's Picture Book Volume I StructureHow to Write Children's Picture Book Volume II Word, Sense, Scene and StoryHow to Write Children's Picture Book Volume III Figures of Speech

Seven:

Another online learning resource I've found invaluable for a range of different subjects is Skill Share. At the time of writing this post they were offering a months free trial. At the end of my free trial I had found the courses so useful and enjoyable that I took out a years subscription at a cost of £123.

Eight: Last but not least right here on the Picture Book Den you will find many great posts about the process and business of writing pictures books. I have written about this before so why not click on this link to discover eight tip based posts written by the Picture Book Den team.

I hope this has been helpful and good luck.

I can be found on LinkedIn.

Learning is The Key to Writing a Great Picture Book - Lynne Garner

I've been a writer and teacher (adults) for just over 25 years. I believe learning is a life long journey and that's why I've always encouraged my students to continue to learn. So, with this in mind I've put together a list of eight resources you may find helpful with learning how to write a great picture book.

One:

Penguin publishing has a features section on their website. Yes, some of the features are plugging their books. However, there are features that are also educational. One written by author Alan Durant (click on this link to read it) provides a helpful list of five things to consider when writing a picture book.

Penguin publishing has a features section on their website. Yes, some of the features are plugging their books. However, there are features that are also educational. One written by author Alan Durant (click on this link to read it) provides a helpful list of five things to consider when writing a picture book.

Two:

Another great resource is The Book Trust. This charity is the UK's largest children's reading charity. Their aim is to get children reading. Each year they reach millions of children across the UK with books, resources and support to help develop a love of reading. If you click on this link you will be taken to their picture book writing page. It contains a wealth of knowledge for writers of all ages. Perhaps start your journey by reading author Joyce Dunbar's 'Guide to Writing Picture Books.'

Julia Donaldson - children's author

Julia Donaldson - children's author Three: If you have the money to invest in your learning then the BBC run courses created by people top in their field and includes Julia Donaldson. A single course costs £79 or you can sign up for a year at a cost of £10 per month and gain access to all of their courses. Once you've studied how to write a picture book then perhaps explore how to write comedy to help you write funny picture books. Or perhaps poetry to help you write a rhyming picture book. To find out more click on this link.

Four:

Picture books are different from other books. They conform to page counts (this is cost driven). The words support the images and the images the words. When you understand how important this is and how it works it will help you write a picture book which flows across the pages. The post written by children's author Tara Lazar if one of the best I've come across. Click here to read it.

Five:

This article on Reedys (provide services to authors) gives tips on how to write your picture book and what questions to ask yourself. It also breaks down the different age groups that picture books are aimed at. Plus the difference between being traditionally published and publishing yourself. Again, simply click on the link to read the article.

Six:If you prefer to go old school and read a book then there are three books which I highly recommend written by children's author Eve Heidi Bine-Stock. They are:How to Write a Children's Picture Book Volume I StructureHow to Write Children's Picture Book Volume II Word, Sense, Scene and StoryHow to Write Children's Picture Book Volume III Figures of Speech

Seven:

Another online learning resource I've found invaluable for a range of different subjects is Skill Share. At the time of writing this post they were offering a months free trial. At the end of my free trial I had found the courses so useful and enjoyable that I took out a years subscription at a cost of £123.

Eight: Last but not least right here on the Picture Book Den you will find many great posts about the process and business of writing pictures books. I have written about this before so why not click on this link to discover eight tip based posts written by the Picture Book Den team.

I hope this has been helpful and good luck.

I can be found on LinkedIn.

November 6, 2023

A brief history of the humble Pencil - by Garry Parsons

When I'm talking to children about my work as an illustrator I tell them about my pencil.

Virtually everything I do starts with a drawing, so the pencil is a very valuable tool for me indeed.

From the initial scribbles of an idea, to thumbnail sketches for a picture book or a cover rough for a fiction title, these drawings set the scene for the projects I'm working on and help me expand my ideas quickly. What's more, pencil marks can be erased, so if you don't like what you've done, you can simply rub it out!

Pencil rough for a picture book spread - Garry Parsons

Pencil rough for a picture book spread - Garry ParsonsI also enjoy telling children that my pencil is in love (urgh, disgusting, yuk they cry!). The one true love of my pencil is not me, unfortunately, it's the rubber.

But why I ask them?

The answer I usually receive is that the rubber erases the mistakes I've made with the pencil. A good answer if you're using a pencil for maths or a language lesson, but for sketching and drawing the rubber is essential. I never think of the rubber as a piece of equipment to eradicate mistakes, instead the rubber is there to help the pencil achieve its goal, to get it right! The rubber is a tool to mould and shape the drawing and therefore a key part in the process of visualising something true.

Scene from The Pencil by Allan Ahlberg and illustrated by Bruce Ingman - Walker Books

Scene from The Pencil by Allan Ahlberg and illustrated by Bruce Ingman - Walker BooksSo these drawings are erased and redrawn, often over and over again until something slowly appears that feels 'right' in its development and detail. This is something I'm sure most artists would agree with.

If it's a picture book I'm working on, the drawings are taken through various stages until they sit harmoniously with the text and are approved for final artwork from the author and publishing team, and if I'm using paint, as I often do for picture books, the drawings are then obliterated by colour and lost forever.

So this post is a little homage to the hard working pencil and a brief history of how it all began.

Decorated cave paintings from Serra da Capybara, Brazil.

Decorated cave paintings from Serra da Capybara, Brazil.Humans have always made tools to make marks on things. The earliest inscriptions and drawings made by humans date back to 3200 BC, but the birth of the pencil only happened around 400 years ago.

Up until then, the drawing technique used by medieval scribes, craftsmen and artists such as DaVinci was Silverpoint, one of several types of metalpoint. Silverpoint was a process of dragging a metal rod across a prepared surface such as gesso. For drawing, the essential metals used were lead, tin and silver for their relative softness. Compared to a pencil however, silverpoint is a time consuming and limiting way to draw, requiring considerable skill. Albrecht Durer's father was a craftsman and taught him to draw in metalpoint.

Self portrait at the age of 13 - Albrect Dürer dated 1484

Self portrait at the age of 13 - Albrect Dürer dated 1484The pencil story begins in the 16th century when graphite deposits were discovered in Seathwaite, Borrowdale in Cumbria, England, apparently revealed to the local people following a heavy storm. The messy black substance they found was at first thought to be lead, commonly used by the Romans to write with on vellum and animal skin but was in fact graphite of a very high and desirable quality. What the people of Borrowdale realised was that this messy substance could be used to make dark marks on paper.

Graphite!

Graphite!Thin sticks could be extracted from the raw graphite and were sold wrapped in string or sheep skin to stop the users hands from becoming filthy. Around this time the word 'pencil' comes into use from the latin penicillum meaning 'little tail' and the graphite pencil from Cumbria becomes widely used across Europe to write and make marks with. Cumbria's unique graphite mines enabled England to enjoy a monopoly on the production of pencils, but these were crude instruments to draw with and still a long way from the pencil that we know today.

In the 1790's, during the Napoleonic War, an embargo imposed by England, limited supplies to France which included the export of pencils and graphite. Running out of suitable materials to write and draw with, Nicholas-Jaques Conté was given the task of solving this problem. Conté was a scientist and inventor and had already had some success in making hot air balloons (where he accidentally lost an eye).

Nicholas-Jaques Conté

Nicholas-Jaques ContéUsing a graphite powder and clay mixture, Conté moulded the substance into sticks and fired them in a kiln.Conté crucially noticed that by varying the ratios of the graphite and clay mixture he was able to alter the hardness of the pencil that he produced. Encasing the stick in wood made yielding it a much more practical and precise drawing tool, with the added benefit of the user being able to choose what hardness of lead best suited their needs.

The oldest pencil in the world, found in a timbered house in 1630 (image; Faber-Castell)

The new 'modern' pencil, encased in wood became highly popular in Europe and other manufacturers began making pencils based on Conté's ideas such as AW Faber in Germany.

In the United States, Henry David Thoreau was producing graphite pencils mixed spermaceti, a wax like substance from the Sperm whale commonly used to in the manufacture of candles at this time. Round pencils were soon replaced by the more practical hexagonal shaped wooden covering to stop them rolling off the table.

Pushing the pencil design further, literally, the first patent for a refillable pencil with a spring mechanism to propel the lead was made by Sampson Mordan and John Issac Hawkins in Britain in 1822.

Morgan went into business manufacturing pencils and other silver objects until the factory was bombed during World War II.

Mordan's patent for the mechanical pencil

Mordan's patent for the mechanical pencilIn japan, Tokuji Hayakawa improved the mechanical pencil and introduced the 'Ever Ready Sharp Pencil' in 1915, giving rise to the Japanese electronics company, Sharp Corporation.

So Hooray for the humble pencil!

For a wonderfully funny read aloud favourite to accompany this post I recommend 'The Pencil' by Allan Ahlbeg and illustrated by Bruce Ingman.

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of many popular children's books and a devoted pencil user. @icandrawdinos www.garryparsons.co.uk

***

October 29, 2023

Has someone written your idea first? Moira Butterfield

It happens to me on a regular basis. I think up an idea – an approach to a subject that might be turned into a book (in my case it’s generally kid’s non-fiction). I put this idea on my ‘think about it soon’ list. Before I get round to it a version appears on Instagram. It’s been published! Everyone says it’s original and great thinking! Grrrrrrrr!

Grumpy author, having just seen her idea already written.

Grumpy author, having just seen her idea already written. Does it happen to you? If you’re a regular author I’ll bet it has at some point.

It’s deeply irritating for quite a while, even though there is a sensible explanation. Ideas come from the myriad things we see and hear, and others might come upon them from the prevailing zeitgeist, too. I have this picture in my mind of small invisible ideas-with-wings whizzing around everyone like birds – zeitgeist birds, perhaps. They change shape depending on the things that happen to people in the world. They’re a bit like little Pokemon, I suppose, and sometimes you can see them and catch them. (I told you I had a sensible explanation).

An idea flying around, possibly near you.

An idea flying around, possibly near you.

It’s hard cheese to know that someone else noticed your good idea, gave it a home and put in the time and effort to care for it and grow it more quickly than you did.

When this happens I think there are three things to do.

1) Stomp around feeling annoyed. Get it out of your system (privately).

2) Wish the other author’s book well. (In fact if it is successful, the chances are that other publishers will be looking for things in the same area). Seek it out and take a quick look at it to see its approach. before....

3. Take your initial idea and work on it. Play with it. Shape it how YOU want. It’s likely to evolve and become a new thing – perhaps on the same subject but with your take and nobody else’s. Your brain is unique, after all. You can make it yours and yours alone, and I reckon that idea will be better and more original than it might ever have been before.

To prove the point, here’s a collage I recently made of me and my own brain. Make your own collage of yourself and yours will be entirely different – though still a collage.

My head in collage form.

My head in collage form.

A good idea came to you. It won’t drift away unless you want it to. Catch it!

Moira Butterfield is an author of many children’s books sold around the world, including WELCOME TO OUR WORLD (Nosy Crow), the LOOK WHAT I FOUND series (National Trust/Nosy Crow) and THE SECRET LIFE series (Happy Yak).

October 23, 2023

SIX THINGS I'VE LEARNED ABOUT RHYMING PICTURE BOOKS by Clare Helen Welsh

This post has been a long time in the making. Over ten yearsin fact! When I first embarked on my picture book journey, my first storieswere in rhyme. I eagerly submitted to my more experienced critique group, onlyto realise that my rhyme wasn’t up to industry standard. For a while after that, I stuck to writing only in prose.

I’m pleased to say that in January 2024, 11 years later, my first rhyming picture book will bepublishing with Nosy Crow! So, in this post I reflect and share what I have learned aboutwriting rhyming picture books.

1. SCANSION ISMORE THAN JUST SYLLABLES

At the start of my writing journey, I thought meter meant counting syllables. I carefullycounted the syllables in my texts and if they had twelve syllables in eachline, for example, I thought I was doing it right! Here is the first spread of one of myfirst ever picture book texts:

Thursday, February 7, 2013 GRANDMA’S GREAT BEANS By Clare Welsh

I enjoy soft bananas and raisins and sweets.

I like crunchy carrots and potatoes and beets.

I’m partial to chicken but prefer veggie mince.

I love sausage trifle with a portion of quince!

I was so confused when my lovely critique partners' feedback said thatthe meter wasn’t working. What was meter? It turns out I didn’t know about scansion! It is possibleto write couplets with the same number of syllables without a clearrhythm - without a consistent pattern of stresses and unstresses. Generally, this is whatis advised for flawless rhyme that is easy to follow and enjoyable to read aloud. If I was re-writing my story today, I might have done somethinglike this. These rewritten lines now have a /stress/ unstress/ unstress/ stress/ pattern:

I like soft bananas and raisins and sweets,

crun chy raw carrots with bacon and beets.

I’m partial to chicken and love veggie mince.

But best I love trifle with spoonfuls of quince!

2. THE RULES DON’TAPPLY TO EVERYONE

I recently met Julia Donaldson at Waterstones Piccadilly and wasable to tell her what an inspiration her books have been, both to me as a writerand a teacher. Rhyming texts can be fantastic to read aloud and have animportant role in early literacy. But many of Julia Donaldson’s texts don’t havea consistent rhythm throughout and read more like songs. I've learned that Julia can get away withthings I can’t! Whilst there are other very successful creatives who have an ininstinctive way of finding rhythm, for me at least, I know I’ll have to treat scansionas more of a science.

3. DON’T LETTHE RHYME HOLD YOUR STORY HOSTAGE

Thursday, February 7, 2013 GRANDMA’S GREAT BEANS By Clare Welsh‘Bad dog!’I shouted and I sent him outside.

I thought of the beans and, heartbroken, I cried.

I wept and I snivelled until I could cry no more.

Then all of a sudden, my eye caught the floor...

Coming back to my eleven year old text, you can see there are places where I have re-arranged the natural word-order to make the line rhyme. This can jolt the reader and make for a less pleasant reading experience - you want to avoid it in picture books where possible. Don’t let yourrhyme hold your story hostage.

Another example of rhyme leading a story, is choosingwords just because they rhyme. For example, including a turf in your under thesea based picture book because it rhymes with surf, even though it doesn't feel like the best word to use in that context. Picture books are focused –every word, every beat, every line should be carefully chosen. Don’t let rhyme leadyour story in random directions. It stands out to the reader as a red herring,if not in the line, then by the end of story when turf doesn’t feature again. Don’t settle for lines that are therefor convenient rhymes and that you wouldn’t have written if your story was told in prose.

4. THE RHYMENEEDS TO WORK FOR EVERYONE

I’m a big advocate of sharing texts with a trusted critique partners. They’ll be able to spot where you’ve re-arranged the natural word order and wheredetails have been added just because you needed a rhyme. They’ll also be able to pointout which near rhymes you can and can’t get away with (f any!) A near rhyme is a rhyme that almost rhymes but not quite, like machine and dream. They’llalso advise which rhymes don’t scan or rhyme for them personally. Your rhyme needs to workin different accents and in different continents. What rhymes for a southerner, might not rhymefor someone with a northern accent. What rhymes in UK English, might not necessarily work in American. This is important – your rhyme needs towork for all the readers who may pick up your book.

5. A WEAKCONCEPT IN PROSE WON’T BE A STRONG CONCEPT IN RHYME

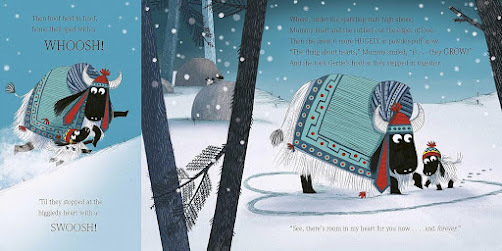

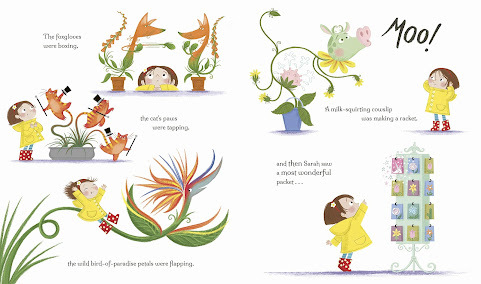

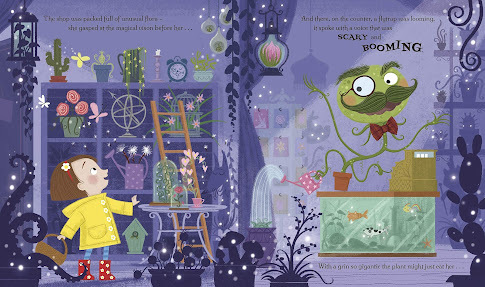

Because of the sing-song nature of rhyme, we sometimes feel that rhymecan carry a text. And of course, it does! But rhyming stories still need to be great stories, with strongcharacters, a clear throughline and multiple hooks, just like a text in prose.Take a look at the How To Grow series by Rachel Morrisroe and StevenLenton, or the Gertie series by Lu Fraser and Kate Hindley.

These are fantastic story concepts, whether in rhyme or prose. (Bothof these authors write in exceptional rhyme by the way, if you are looking for examplesof the industry standard.) This pointabout strong concepts is important for co-editions. A publisher will wantto try and sell your text to foreign territories. A rhyming text would have tobe translated or re-written prose, so it needs to be worth that effort.

6. YOU CANLEARN HOW TO WRITE IN RHYME

I mentioned at the top of the top of this document that my firststories were in rhyme. When I realised I didn’t understand scansion, I stopped writingin rhyme for several years. I tried again during the pandemic when a rhymingcouplet appeared in my head. Quite instinctively, these became the text publishingin a few months’ time. I’ve still had to work hard to make sure my meter isconsistent. I’ve shared the texts with critique partners and editors who have helpedto iron out the pitfalls of writing in rhyme mentioned above, but…

I am really pleased that my next picture book will be my rhymingdebut! And I hope that this shows you that writing in rhyme – just like writinggenerally – is a skill you can practise and learn and get better at.

CLARE HELEN WELSH

Clare Helen Welsh is a children's writer from Devon. She writes fiction and non-fiction picture book texts - sometimes funny, sometimes lyrical and everything in between! Her latest picture book is called 'Never, Ever, Ever Ask A Pirate To A Party,' illustrated by Anne-Kathrin Behl and published by Nosy Crow. Her debut rhyming picture book will publish in January 2024. You can find out more about her at her website www.clarehelenwelsh.com or on Twitter @ClareHelenWelsh . Clare is represented by Alice Williams at Alice Williams Literary.

October 8, 2023

Jen Khatun - The Curious Creative and a Devoted Beret Collector by Chitra Soundar

I recently interviewed Jen Khatun, illustrator of wonderful picture books and chapter books about her work and styles and process. Here are some amazing insights and a peep into her process. Enjoy.

Hello! I’m Jen, Children’s Book Illustrator since 2016, represented by The Bright Agency. My hometown is the quaint and beautiful city of Winchester, Hampshire. My origins begin with my family, my Mum and Dad, both heralded from the exotic land of Bangladesh.

My present is now living nestled somewhere in the rolling hills of East Sussex with my partner and our dog. To describe me in a few words:

- I obsessively wear knit jumpers

- My colours are Red, Yellow, Blue and Pink

- Berets

- a good cup of tea in my hand

- Autumn and Christmas are my favourite times of the year.

Here is a trailer of My Must-Have Mum illustrated by Jen Khatun written by Maudie Smith

What is your latest book?

My latest book is Stolen History by Sathnam Sanghera published by Penguin Random House. This is an image from that book.

Image from Stolen History by Sathnam SangheraWhat are your favourite tools for work?

Image from Stolen History by Sathnam SangheraWhat are your favourite tools for work? Pen and Ink are my favourite, and always will be. I just simply love the looseness, the freedom, the whimsical line. But when juggling lots of books, working digitally has helped, especially with editing illustrations. It has saved me time from re-drawing the artwork again, without compensating my illustrational style.

Illustration from Sona Sharma - Wish Me Luck by Chitra Soundar

Illustration from Sona Sharma - Wish Me Luck by Chitra Soundar

Artwork from Star Rivals - Bollywood Academy by Puneet Bhandal

Artwork from Star Rivals - Bollywood Academy by Puneet BhandalHow would you describe your style of art?

In a few words, I would say my style is:whimsicalmagicalfun and boldexpressivenostalgicWhat are your tips for relaxing especially if you have stacked-up deadlines?Whether you go out for a walk in the outdoors, read a collection of books, watch your favourite TV series(My go- to are Columbo and Poirot), or even take yourself to the cafe. ALWAYS make time to break away from your desk to get some inspiration and some breathing space. Having a time-out will only fuel your creativity.

In a few words, I would say my style is:whimsicalmagicalfun and boldexpressivenostalgicWhat are your tips for relaxing especially if you have stacked-up deadlines?Whether you go out for a walk in the outdoors, read a collection of books, watch your favourite TV series(My go- to are Columbo and Poirot), or even take yourself to the cafe. ALWAYS make time to break away from your desk to get some inspiration and some breathing space. Having a time-out will only fuel your creativity.

Illustration from Sit in the Sunand Other Lessons in the Spiritual Wisdom of Cats by Jon M Sweeney

Illustration from Sit in the Sunand Other Lessons in the Spiritual Wisdom of Cats by Jon M SweeneyWhen you started out, was it hard? What did your family say when you didn't want a regular 9-5 job?‘Art does not bring food to the table’ my Mum would say. I never judged her comment, it simply represented a part of her generation and culture believing that working as a Banker, Solicitor or Doctor would bring happiness, financial stability and status. But that just wasn’t my calling. It took time and hard work to show my Mum how drawing gave me happiness and in time, a healthy illustrious career.

Mary Poppins as imagined by Jen Khatun

Mary Poppins as imagined by Jen KhatunAnd lastly do you have advice for someone who wants to turn pro or begin their journey as an illustrator?My last note to all the creatives out there, whether you are studying, graduated or thinking about a change in direction:

- Be curious and explore all mediums to find one that you enjoy and fits you.- Self-initiated projects- a brilliant way to extend your portfolio.- Break moulds and be daring- your drawing style is your own signature, you do not need to change it to fit in, respect your authentic self.- Network- venture out to art and crafts events, shows and seminars. It’s a great way to start theconversation and get yourself heard.- Stepping away- A good time away from the desk time to time will re-charge your imagination and will guarantee strong performance and work.

Art from How Many Hairs on a Grizzly Bear?: And Other Big Questions about Numbers written by Tracey Turner

Art from How Many Hairs on a Grizzly Bear?: And Other Big Questions about Numbers written by Tracey TurnerFind out more about Jen Khatun and her work at https://www.jenkhatun.com/

Thank you Jen Khatun for giving us a glimpse into your world and process and sharing some wonderful artwork with us.

Chitra Soundar is an internationally published, award-winning author of children’s books and an oral storyteller. Chitra regularly visits schools, libraries and presents at national and international literary festivals. She is also the creator of The Colourful Bookshelf, a curated place for books for children by British authors and illustrators.

Find out more at http://www.chitrasoundar.com/ and follow her on twitter here and Instagram here.

September 24, 2023

What's So Funny? By Pippa Goodhart

I’ve been thinking about what makes a funny picture book funny.

Lots of things can be funny for young children, and funny for the adults who share picture books with them. Those two sides of the book audience might well laugh at different things offered by the book.

Getting things wrong can be funny if the circumstances are right. A woman slipping on a banana skin, falling into the pond, then coming up from the water with a duck and weed on her head is funny … just so long as we know that she is somebody fictional who can’t really be hurt, or she is somebody nasty who deserves to be made to look silly, or she’s laughing at herself because she thinks it’s funny.

Farts, pants and burps can be funny because children know they are regarded as naughty, something to be hidden, and so it seems daring and a bit shocking to air them in public. I suggest that those themes are funnier when you’re four years old than when you’re forty … although seeing a child collapse in giggles at the word ‘fart’ can make the whole book sharing situation for the adult reader funny in itself.

But I think I’ve discovered what makes for the funniest picture books of all, and that is TRUTH. Not factual story truth. I’m struggling to think of an example of a really really funny picture book which features human main characters, or one that tells of true events. But it’s the emotional truth that matters. The animal characters in funny books are behaving at an emotional level like humans. We recognise that, and it all seems the funnier for human feelings to be played out by animals.

Here are my three-year-old grandson’s current favourite funny picture books –

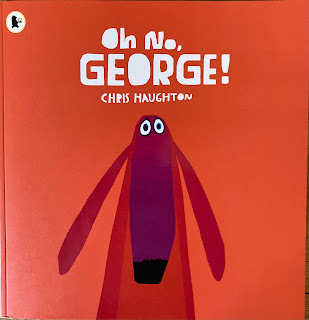

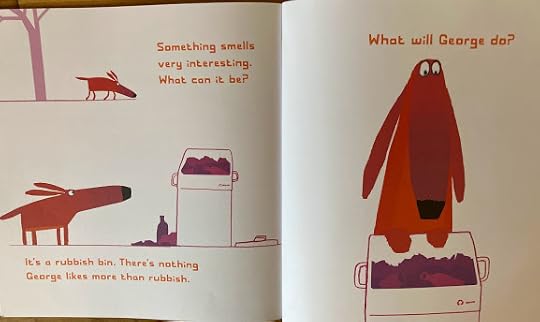

Oh No, George! By Chris Haughton features dog George who promises his human, Harris, that he will be good, and he does mean to be good, but he is then faced with temptation. Three times we see him tempted, and we’re asked ‘What will George do?’ before seeing that he does eat the cake, chase the cat, then dig up a plant. Tension thrills as George’s owner arrives home! But Harris is forgiving, and George apologises, and out they go for a walk to start afresh. But temptations arise once more. What will George do? To our surprise, he resists the cake this time, and the cat, and the flower bed. But then he is faced with a smelly rubbish bin …

… And we’re left to decide for ourselves whether or not George succumbs!

Very relatable for a three-year-old who says he’ll be quiet in the library, then can’t resist shouting out loud, getting a reaction, and shouting more. Relatable, too, for a Granny who knows she shouldn’t have that chocolate biscuit, but … What will Granny do? This story is so true to the fight between good intentions and weakness in most of us.

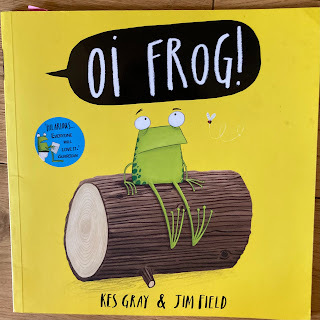

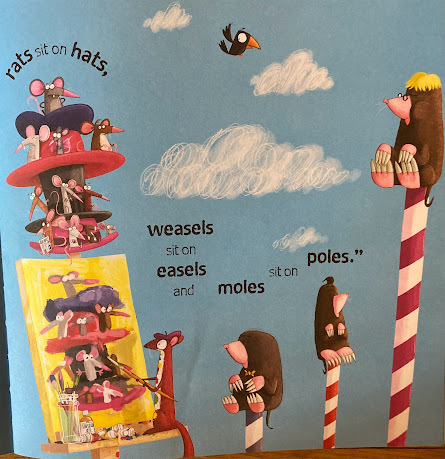

Oi Frog! by Kes Gray and Jim Field has been followed by more Oi books, and it’s no wonder. The humour here comes from a character, the cat, who insists on a rule that sounds almost reasonable at first – that frogs should sit on logs – but soon becomes more and more ridiculous. Not only do gophers have to sit on sofas and mules sit on stools, but lions must sit on irons and seals sit on wheels!

How does this growing list of rule-following nonsense end? If you don’t know the book, go and borrow or buy it. Its punchline fits perfectly.

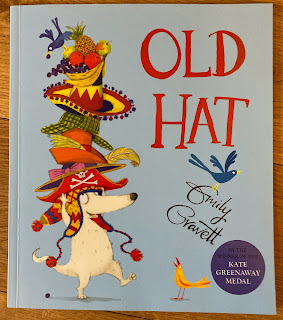

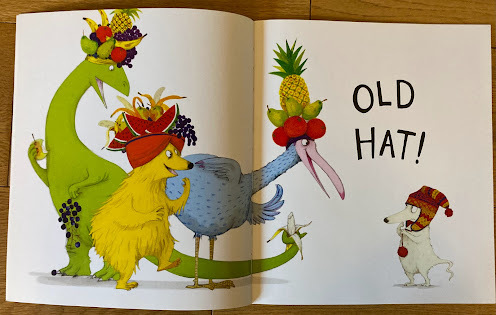

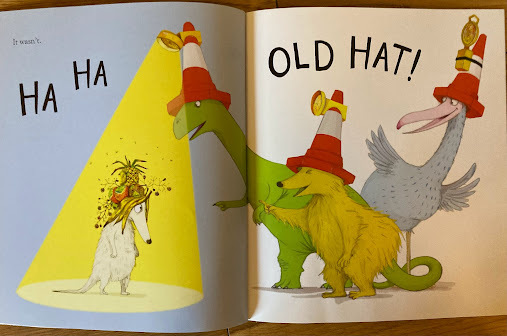

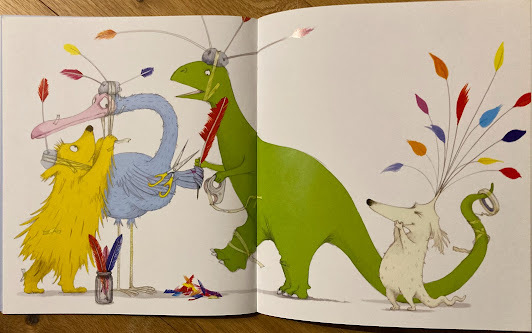

Old Hat by Emily Gravett is a delight of colourful fun that takes us on an emotional journey. It’s a study of the power of fashion, and it bursts that power with the most pleasing of surprises. Harbet has a hat that he loves, knitted by his Nan, warm and toasty, but … ‘OLD HAT’ jeer a trio of others.

So Harbet hurries to acquire his own fruity confection of a hat … only to find that fashion has moved on.

Repeat, and repeat again, the hats getting more weird and wonderful as we go … until Harbet is so fed up with never being able to keep up with fashion that he gives up, and throws away all his hats to reveal his natural delightful explosion of feathery head adornment. Now the tables are turned.

A lesson in the folly of trying to follow fashion. Its recognising the truth of that which makes this story particularly funny.

I think that it’s the combination of surprise and fun with recognition of truth that makes for the funniest picture book stories. But do tell in the comments what you find funniest in picture books.

September 10, 2023

Sixteen Years of Storytime (with Mini Grey)

Longago, before I had a child at all, I went to a talk at the Oxford LiteraryFestival by author/illustrator Ted Dewan. Ted said that, when you have a child,you finally see the very beginning of the story, the bit of the story of yourlife you can’t remember in your own life: those first months and years of beinga baby.

Longago, before I had a child at all, I went to a talk at the Oxford LiteraryFestival by author/illustrator Ted Dewan. Ted said that, when you have a child,you finally see the very beginning of the story, the bit of the story of yourlife you can’t remember in your own life: those first months and years of beinga baby.Andso the time came (2006) when we had a new-born Herbie and amazingly thehospital let us take him home and try to look after him on our own.

Inthe first years of storytime we were becalmed in a world of pinky-ponks andninky-nonks for quite a while, managing to climb out with Shoe Baby, ThatRabbit Belongs to Emily Brown and Room on the Broom. Before Herbie could talk,we read him Shoe Baby, fervently hoping his first words would be “How do youdo?” (It was “star.”)

from Shoe Baby by Polly Dunbar and Joyce Dunbar

from Shoe Baby by Polly Dunbar and Joyce Dunbar WhenHerbie got to be about 4 or 5 we tried mixing in the odd longer book; someRoald Dahl, some Winnie the Pooh (OK, I was desperate to read Herbie my ownfavourite childhood chapter books) - andour reading landscape turned from the garden of picture books onto some longerpaths. Picture books weren’t abandoned, and Herbie would grab a stack of themto commune with when he woke up. And he still has a shelf of picture books inhis room at age 16. Ones that it became important to keep close.

HERBIE’S PICTUREBOOK SHELF

HERBIE’S PICTUREBOOK SHELFReadinga chapter book is a gift; every story time there’s the thrill of discovering whathappens next, and the chance to carry on communing with characters that youknow. Some of our very favourite early chapter books were the brilliantlyillustrated ‘Man Who Wore All His Clothes’ series by Allan Ahlberg and KatharineMcEwan – with maps and timelines to pore over. And very very funny. Other fabulously generously illustrated early chapter book favourites were Cakes in Space (and anything else) by Philip Reeve and Sarah McIntyre, and the Ottoline (and later, Goth Girl) books by Chris Riddell.

OUR EARLY CHAPTERBOOK SHELF

OUR EARLY CHAPTERBOOK SHELFWhenHerbie got to be 5 or 6 he started bringing home a ‘Reading Book’ in his schoolbookbag. It would usually be a Biff & Chip Oxford Reading Tree book – and Ido like these…

BUT….

(1)it was usually not the next one in the series and

(2)Herbie knew that he had to read it to us, and that a sort of test was going on.

Andthat sucked all the fun out of reading.

Then:we discovered the whole of Harry Potter, the books AND the films. When I askedHerbie if he wanted to read Harry’s bits in The Philosopher’s Stone, he said“Yes” – and he carried on reading Harry’s part right through to the DeathlyHallows. And this was brilliant, as I could stop feeling guilty because I washearing Herbie read – plus he had to follow the words on the page to know whento come in when Harry spoke.

HARRY POTTER,Illustrated by Jim Kay: a hearth to gather around

HARRY POTTER,Illustrated by Jim Kay: a hearth to gather aroundParentsoften stop reading to their children when the kids are able to readindependently, which is generally when they start reading chapter books ontheir own, at about 7 or 8 or 9. But just because your child can readindependently doesn’t mean they don’t enjoy being read to. I’m a grown-up, andI love being read to.

Thereare big benefits to be had for reading together with the 11-13 yr olds and theteenage crowd – especially having something to talk about together, and ifyou’re reading non-fiction, shared topics to talk about.

NowHerbie’s dad also likes reading together, so at story time it would be thethree of us (and the parent who wasn’t reading would often doze off). So we hadthe massive advantage of two parents who want to do story time together, andalso the massive advantage of having only the one child – we didn’t have tonegotiate story time with differently aged offspring.

a shelf of a few of our utter favourites

a shelf of a few of our utter favouritesAndthere we went on our journey through picture books to classics (all the books Iloved as a child that I couldn’t wait to read with Herbie) to chapter books tofactual books to grown up books via Dickens and Jane Austen and Dan Brown; toscience fiction and Isaac Asimov; the whole of James Herriott and Gerald Durrell.We learned the value of reading books you don’t get on with (and the rights ofthe Reader to abandon a book) – and we found that thinking about why we didn’tlike a particular book could help us discover why we loved the books that we loved.We read the things none of us might choose to read just for ourselves.

Wemined seams of favourites: Andy Stanton, Chris Riddell and Paul Stewart’s FarFlung Tales and Muddle Earth books, Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman. Wehung out at the library finding the next place to start drilling.

Wemined seams of favourites: Andy Stanton, Chris Riddell and Paul Stewart’s FarFlung Tales and Muddle Earth books, Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman. Wehung out at the library finding the next place to start drilling.Wetravelled with our reading book and it was our secret weapon to make time fly –I remember us reading The Time Machine (retold from the HG Wells) on atrain back from London and having reluctantly to stop to get off the train atOxford…

MarkHaddon’s Curious incident of the Dog in the Night-time was interesting:to read out the swearing or not? (I decided to read it out.) Reading A MonsterCalls by Patrick Ness and Jim Kay – we discovered our faces were wet.

OUR LATER CHAPTERBOOK SHELF

OUR LATER CHAPTERBOOK SHELFIdiscovered books that I wouldn’t choose usually that are pure wonderfulness,often on the recommendation of booksellers: for example, Judith Kerr’s HowHitler Stole Pink Rabbit. We had big discussions about world-buildingreading La Belle Sauvage. I found some things just didn’t work readaloud: my super-favourite E Nesbit Five children & It – just didn’tring right. But Nesbit’s The Story of the Treasure Seekers was stillfresh and funny. Our very last books: were, I think, Peter Godfrey Smith’s Metazoa,and Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code (read for all the laughs and accents byHerbie’s Dad.)

Some of ourreading in the last few years

Some of ourreading in the last few years

Butnow, at 16 and starting his A level year – for now, maybe for ever, for us dailystory time has stopped. But if I ever want an opinion on a text, my go-to textpert is Herbie.

Now,I do love to read aloud, and you should hear the terrible accents that I cando. But not everyone feels like that.

Ifno-one’s ever read to you, reading aloud is not a normal or comfortable thingto do. A recent article in the Guardian reported that most parents of young children would like to spend more time reading with them, but a third lacked the confidence to do so; “Reading out loud and doingcharacter voices were cited as reasons for doubting their confidence.” In the same article SF Said (author of Tyger and much more) says: “It’s much better toread for a little bit than not to read at all. Just 10 minutes a day can beenough to make the difference.”

Howcan we empower parents to read to their children just for fun? Modelling how todo it could be useful; could teachers help parents here? Maybe schools could invite parents in to picture book storytimes with their children, maybe when the children start school, where they can experience being read to, and how it feels, and how it's possible to do it? And I wonder if reading to your child just for fun might be a more useful thing to do, than to hear your child read? (Please, opinions about this are very welcome!)

It’sworth remembering why reading to your child, just for fun, is super useful:

1. Routine saves theday: it gives you a daily routine that helps the route to bedtime, it’s a signthat bedtime is coming.

2. It gives yousomething to talk about with your child.

3. The book does theentertaining for you, you don’t have to invent it, just read it – so it’s atime together that’s low-stress.

4. The books that youread together can unlock passions and interests that you share together.

Mini’s PICTUREBOOK SHELF

Mini’s PICTUREBOOK SHELF

Andnow I want to return to picture books.

I’m not a great reader: I find it hard tosettle down and read. I read very slowly, at about the speed I’d read it outloud.

Ithink picture books are great way in for those who find reading hard, to getright into a story and be able to discuss it on a level platform.

We are all expert readers of pictures. Pictures areopen ended. In picturesyou can say very complex things, things that it would take an enormous numberof words to explain. Often the illustrator may not realise whythey’ve made the picture how it is – but there will be a reason, even if itssubconscious or accidental…So pictures are open to everyone’s interpretation.

There is no right answer when you’re talking about apicture: the picture is a world of possibility. Sobooks with pictures should be available to all children of all ages.

Thesecret power of picture books – with their words & pictures, is their verywide span of accessibility. The picture book performance is a collaboration;the picture book’s audience includes the adults.

The pictures feed the words, and the words the pictures,in a collaborative relationship, each adding depth to the other.

Here are all the books that I’ve featured, in order:

That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown by Cressida Cowelland Neal Layton, Shoe Baby by Joyce Dunbar and Polly Dunbar, Room on the Broomby Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, The Cat Who Got Carried Away by AllanAhlberg and Katharine McEwen, Cakes in Space by Philip Reeve and SarahMcIntyre, Winnie the Pooh by AA Milne and Ernest Shepard, Ottoline and theYellow Cat by Chris Riddell, Man on the Moon by Simon Bartram, Pumpkin Soup byHelen Cooper, Two Frogs by Chris Wormell, Rules of Summer by Shaun Tan, The Daythe Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers, The Arrival by Shaun Tan, Tatty Ratty byHelen Cooper, The Snail and the Whale by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler,Truckers by Terry Pratchett, Mr Gum by Andy Stanton and David Tazzyman, TheGraveyard Book by Neil Gaiman and Chris Riddell, The Amazing Maurice and HisEducated Rodents by Terry Pratchett, Boom! by Mark Haddon, Corby Flood by PaulStewart and Chris Riddell, Framed by Frank Cottrell Boyce, Varjak Paw by SF Said; Great Expectationsby Charles Dickens, The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks, A MonsterCalls by Patrick Ness and Jim Kay, The Garden of the Gods by Gerald Durrell,The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time by Mark Haddon, Muddle Earthby Paul Stewart and Chris Riddell, The Song From Somewhere Else by AF Harroldand Levi Pinfold, The Belle Sauvage by Philip Pullman, All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriott, NaturalHistories by Brett Westwood and Stephen Moss, Prisoners of Geography by TimMarshall, Stuff Matters by Mark Miodownik, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxyby Douglas Adams, Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman, The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown,Metazoa by Peter Godfrey-Smith, The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace andBabbage by Sidney Padua, The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson,Paradise Sands by Levi Pinfold, Mammal Takeover by Abby Howard, The Iron Man byTed Hughes and Chris Mould, The Hideaway by Pam Smy, Cassandra Darke by PosySimmons.

I didn’t have room for the many many more that we’veloved.

Mini's latest book is The Greatest Show on Earth, published by Puffin.

September 3, 2023

When Picture Book Characters Evolve - Lynne Garner

Sometime in 2007 I started working on a picture book idea which featured a mischievous rabbit by the name of Cottontail and his annoying little sister. I loved the idea. But it didn’t matter how many drafts I wrote, ‘their’ story wasn’t working. So, the story was filed away in my WIP (work in progress) file.

Burdock's favourite toyA year later I started a book illustration course. I decided I’d resurrect this story and reconnect with my two characters. I hoped by drawing them the story would ‘write’ itself. However, as I worked the original characters evolved into Burdock the rabbit, who had adventures with his toy rabbit. Again, I fell in love with the characters, but the story wasn’t quite right. So, into the WIP file it went.

Burdock's favourite toyA year later I started a book illustration course. I decided I’d resurrect this story and reconnect with my two characters. I hoped by drawing them the story would ‘write’ itself. However, as I worked the original characters evolved into Burdock the rabbit, who had adventures with his toy rabbit. Again, I fell in love with the characters, but the story wasn’t quite right. So, into the WIP file it went.

Five years later I was clearing out my files and rediscovered Burdock and tried again to write a story that worked. Eventually after a rename and many rewrites I reached the point where I felt I could send to a freelance proof-reader come editor. After she’d worked her magic and with a lot of support from some very clever people a set of book apps featuring Burdock Rabbit and his toy rabbit were release. A year later, I decided (I have no idea why) to design a crochet pattern for Burdock’s toy rabbit.

Whilst researching how to do this I fell down the internet ‘rabbit hole’ and rediscovered Brer Rabbit. I was surprised to find that Enid Blyton (whose versions I had enjoyed as a child) wasn’t the first author to write about this character. I couldn’t help myself and found eBook versions of the originals, which were written in the late 1800s. The results of this reading resulted in my third self-published short story book, Ten Tales of Brer Rabbit in 2017.

Whilst researching how to do this I fell down the internet ‘rabbit hole’ and rediscovered Brer Rabbit. I was surprised to find that Enid Blyton (whose versions I had enjoyed as a child) wasn’t the first author to write about this character. I couldn’t help myself and found eBook versions of the originals, which were written in the late 1800s. The results of this reading resulted in my third self-published short story book, Ten Tales of Brer Rabbit in 2017.

Last year I decided to try my hand at script writing. I was extremely lucky to find a wonderful mentor, who is supporting me in my endeavours. Having fell in love with Brer Rabbit I decided to use my versions of his stories as my starting point. As I've worked on my scripts I've discovered I'm using some of my picture book writing skills, both being very visual forms of story telling. I’ve also realised my latest character is made up of little bits of Cottontail, Burdock, and Brer Rabbit.

So, although those very first picture book stories still languish in my WIP file little hints of the characters are creeping into my first set of scripts.