SIX THINGS I'VE LEARNED ABOUT RHYMING PICTURE BOOKS by Clare Helen Welsh

This post has been a long time in the making. Over ten yearsin fact! When I first embarked on my picture book journey, my first storieswere in rhyme. I eagerly submitted to my more experienced critique group, onlyto realise that my rhyme wasn’t up to industry standard. For a while after that, I stuck to writing only in prose.

I’m pleased to say that in January 2024, 11 years later, my first rhyming picture book will bepublishing with Nosy Crow! So, in this post I reflect and share what I have learned aboutwriting rhyming picture books.

1. SCANSION ISMORE THAN JUST SYLLABLES

At the start of my writing journey, I thought meter meant counting syllables. I carefullycounted the syllables in my texts and if they had twelve syllables in eachline, for example, I thought I was doing it right! Here is the first spread of one of myfirst ever picture book texts:

Thursday, February 7, 2013 GRANDMA’S GREAT BEANS By Clare Welsh

I enjoy soft bananas and raisins and sweets.

I like crunchy carrots and potatoes and beets.

I’m partial to chicken but prefer veggie mince.

I love sausage trifle with a portion of quince!

I was so confused when my lovely critique partners' feedback said thatthe meter wasn’t working. What was meter? It turns out I didn’t know about scansion! It is possibleto write couplets with the same number of syllables without a clearrhythm - without a consistent pattern of stresses and unstresses. Generally, this is whatis advised for flawless rhyme that is easy to follow and enjoyable to read aloud. If I was re-writing my story today, I might have done somethinglike this. These rewritten lines now have a /stress/ unstress/ unstress/ stress/ pattern:

I like soft bananas and raisins and sweets,

crun chy raw carrots with bacon and beets.

I’m partial to chicken and love veggie mince.

But best I love trifle with spoonfuls of quince!

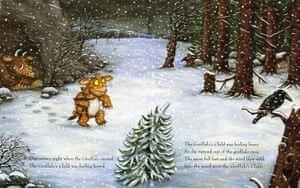

2. THE RULES DON’TAPPLY TO EVERYONE

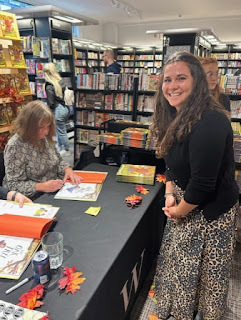

I recently met Julia Donaldson at Waterstones Piccadilly and wasable to tell her what an inspiration her books have been, both to me as a writerand a teacher. Rhyming texts can be fantastic to read aloud and have animportant role in early literacy. But many of Julia Donaldson’s texts don’t havea consistent rhythm throughout and read more like songs. I've learned that Julia can get away withthings I can’t! Whilst there are other very successful creatives who have an ininstinctive way of finding rhythm, for me at least, I know I’ll have to treat scansionas more of a science.

3. DON’T LETTHE RHYME HOLD YOUR STORY HOSTAGE

Thursday, February 7, 2013 GRANDMA’S GREAT BEANS By Clare Welsh‘Bad dog!’I shouted and I sent him outside.

I thought of the beans and, heartbroken, I cried.

I wept and I snivelled until I could cry no more.

Then all of a sudden, my eye caught the floor...

Coming back to my eleven year old text, you can see there are places where I have re-arranged the natural word-order to make the line rhyme. This can jolt the reader and make for a less pleasant reading experience - you want to avoid it in picture books where possible. Don’t let yourrhyme hold your story hostage.

Another example of rhyme leading a story, is choosingwords just because they rhyme. For example, including a turf in your under thesea based picture book because it rhymes with surf, even though it doesn't feel like the best word to use in that context. Picture books are focused –every word, every beat, every line should be carefully chosen. Don’t let rhyme leadyour story in random directions. It stands out to the reader as a red herring,if not in the line, then by the end of story when turf doesn’t feature again. Don’t settle for lines that are therefor convenient rhymes and that you wouldn’t have written if your story was told in prose.

4. THE RHYMENEEDS TO WORK FOR EVERYONE

I’m a big advocate of sharing texts with a trusted critique partners. They’ll be able to spot where you’ve re-arranged the natural word order and wheredetails have been added just because you needed a rhyme. They’ll also be able to pointout which near rhymes you can and can’t get away with (f any!) A near rhyme is a rhyme that almost rhymes but not quite, like machine and dream. They’llalso advise which rhymes don’t scan or rhyme for them personally. Your rhyme needs to workin different accents and in different continents. What rhymes for a southerner, might not rhymefor someone with a northern accent. What rhymes in UK English, might not necessarily work in American. This is important – your rhyme needs towork for all the readers who may pick up your book.

5. A WEAKCONCEPT IN PROSE WON’T BE A STRONG CONCEPT IN RHYME

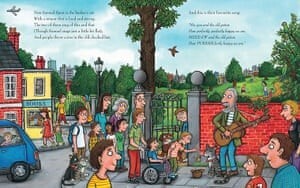

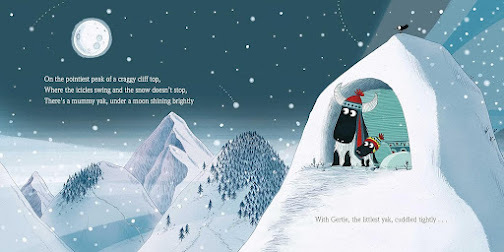

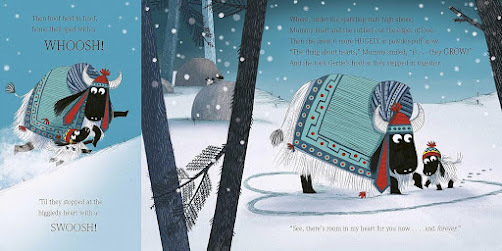

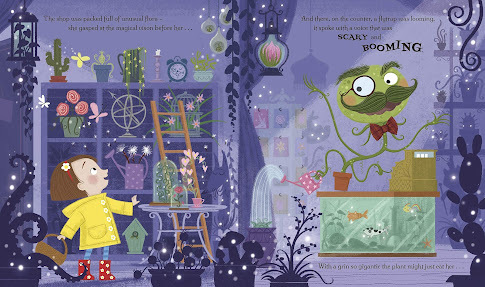

Because of the sing-song nature of rhyme, we sometimes feel that rhymecan carry a text. And of course, it does! But rhyming stories still need to be great stories, with strongcharacters, a clear throughline and multiple hooks, just like a text in prose.Take a look at the How To Grow series by Rachel Morrisroe and StevenLenton, or the Gertie series by Lu Fraser and Kate Hindley.

These are fantastic story concepts, whether in rhyme or prose. (Bothof these authors write in exceptional rhyme by the way, if you are looking for examplesof the industry standard.) This pointabout strong concepts is important for co-editions. A publisher will wantto try and sell your text to foreign territories. A rhyming text would have tobe translated or re-written prose, so it needs to be worth that effort.

6. YOU CANLEARN HOW TO WRITE IN RHYME

I mentioned at the top of the top of this document that my firststories were in rhyme. When I realised I didn’t understand scansion, I stopped writingin rhyme for several years. I tried again during the pandemic when a rhymingcouplet appeared in my head. Quite instinctively, these became the text publishingin a few months’ time. I’ve still had to work hard to make sure my meter isconsistent. I’ve shared the texts with critique partners and editors who have helpedto iron out the pitfalls of writing in rhyme mentioned above, but…

I am really pleased that my next picture book will be my rhymingdebut! And I hope that this shows you that writing in rhyme – just like writinggenerally – is a skill you can practise and learn and get better at.

CLARE HELEN WELSH

Clare Helen Welsh is a children's writer from Devon. She writes fiction and non-fiction picture book texts - sometimes funny, sometimes lyrical and everything in between! Her latest picture book is called 'Never, Ever, Ever Ask A Pirate To A Party,' illustrated by Anne-Kathrin Behl and published by Nosy Crow. Her debut rhyming picture book will publish in January 2024. You can find out more about her at her website www.clarehelenwelsh.com or on Twitter @ClareHelenWelsh . Clare is represented by Alice Williams at Alice Williams Literary.