Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 9

November 8, 2022

What's the obsession with unicorns and where did it start? - Garry Parsons

Unicorns are well established members of the picture book bestiary, but where did they come from and how long are they staying?

The unicorn, it seems, has origins in all sorts of places, from Chinese mythology to early Christian folklore, as well as sources being found in India and Persia.

The Hindu epic, Mahabharata tells of a human bodied unicorn called "Gazelle Horn" which has to be lured from the forest by the King's beautiful daughter in order to guarantee rainfall over the kingdom.

The Chinese unicorn, Ch'i-Lin, also lives alone in the forest. It's body gives off light and it has a voice like a monastery bell. Ch'i-Lin is the very meaning of benevolence and wisdom and is so allusive that it is only seen when the kingdom is ruled virtuously.

Unicorn Cake!

Unicorn Cake!

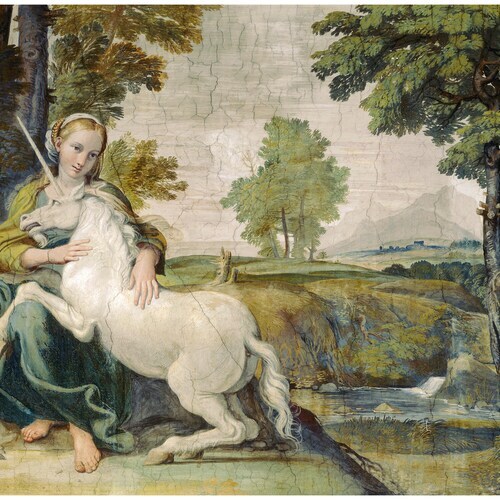

Unicorns were a special fascination in the West during medieval Christian times. Still depicted with a fiery wild nature, they were also imbued with a loving spiritual benevolence. They were imagined in art as a metaphor for Christ.

This medieval unicorn, also aloof, rare and solitary, could only be coaxed from the forest by a virgin were it willingly allowed itself to be captured. This capture is interpreted as as the spirit's willingness to be incarnated through the body of the Virgin Mary.

Virgin and Unicorn 1602 - Domenichino (1581 -1641)

Virgin and Unicorn 1602 - Domenichino (1581 -1641)So the general idea of the unicorn is that it of a wild, solitary creature, capable of great strength and speed and a creature that cannot be captured alive unless by lure or trickery. Most importantly, it has magical powers and is distinguished by a single horn in the centre of the forehead.

The Unicorn in Captivity - Tapestry 1495 - 1505 Brussels

The Unicorn in Captivity - Tapestry 1495 - 1505 Brussels

Pulling our search for unicorns back from the mythological a little, is Elasmotherium sibiricum, otherwise known as the Siberian unicorn. Elasmotherium went extinct an estimated 39,000 years ago. Related to the five surviving species of rhino we know today, only twice as big (weighing 3.5 tonnes and standing 2.5 metres high), in Elasmotherium's day, there were as many as 250 different species of this ancient rhino.

Elasmotherium sibiricum

Elasmotherium sibiricum

What's fascinating about this animal is that it went into extinction around the same time that Neanderthals went extinct, meaning that they would have been sharing Eurasia with both modern humans and Neanderthals. Clearly though, it wasn't all rainbows and sparkles for Elasmotherium, so where does our modern unicorn come from?

danaisabellaa

danaisabellaa

Throughout the medieval period and long after, the unicorn and especially the horn, was thought to hold magical powers. In the 16th and 17th Century, trade in unicorn horn powder was thought to hold powers at detecting poison or purifying contaminated water or healing wounds and illness. The horns themselves being narwhal or elephant tusks, marking the unicorn with a commercial value as well as perpetuating the unicorn's reputation for being rare and elusive - a creature you would know about but never quite see and would certainly never capture.

However, the belief in the unicorn horns ability to heal began to be met with scepticism and the existence of the mythical creature waned. So the golden age of the unicorn for this period, came to and end.

The Narwhal's tusk used as evidence for the existence of the unicorn

The Narwhal's tusk used as evidence for the existence of the unicorn

The rediscovery of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries in the late 19th Century sparked a new interest in unicorns. A series of six tapestries, created in the style of mille-fleurs ("thousand flowers") was woven in Flanders from wool and silk. The tapestries are considered one of the greatest works of the middle ages in Europe. Each of the six tapestries includes a noble lady depicted with a unicorn on her right and a lion to her left, and have been attributed as the inspiration for the French Symbolist painter, Gustave Moreau, in his canvas 'The Unicorns'. Later still, during the 1950's, Jean Cocteau designed a ballet inspired by the tapestries.

The Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries - Musee de Cluny - Paris

The Lady and the Unicorn Tapestries - Musee de Cluny - Paris The Unicorns - Gustave Moreau 1885

The Unicorns - Gustave Moreau 1885The unicorn has also made it's mark for the LGBTQ community in the last century, in it's fusion with the rainbow flag created by American artist Gilbert Baker, as a joyous symbol of diversity, with the unicorn appearing on T-shirts and banners at pride events around the world.

Starbucks Unicorn Frappuccino

Starbucks Unicorn FrappuccinoUnicorns get a real boost from the popularity of 'My Little Pony' in the 90's but it's not until later that the mythical beast begins to make a real cultural comeback.

Fuelled by social media and the arrival of the Unicorn Frappuccino from Starbucks in 2016, unicorn fever takes off and a year later, My Little Pony; The Movie, voiced by Zoe Saldana, Emily Blunt and Kristin Chenoweth makes a hit and the cinema box office.

My Little Pony - The Movie

My Little Pony - The Movie Instagram feeds become flooded with the new, vibrant, glitter effused, pastel coloured sparkling unicorn that we are familiar with today.

Vibrantandpure

Vibrantandpure

From unicorn toast and unicorn beauty products with make-up tutorials on youtube, to unicorn inflatable pool floats, unicorn cakes, unicorn eyelashes and false nails, unicorn slippers, unicorn onesies and ...unicorn picture books!

A selection of unicorn picture books from Dad Suggests

A selection of unicorn picture books from Dad SuggestsSo regardless where the latest unicorn fever has come from, it is certainly alive in our minds and galloping wild through our imaginations. The latest golden age of the unicorn is well and truly underway and looks like it is here to stay... for a while at least.

So celebrate National Unicorn Day on 9th April with unicorn cake!

***

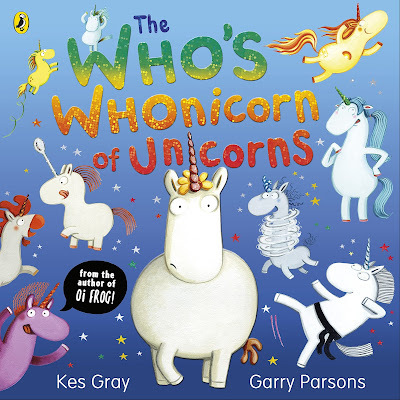

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of children's picture books including The Who'sWhonicorn of Unicorns and Daisy and the Trouble with Unicorns, both written by Kes Gray and published by Puffin.

And to confirm that the trend for unicorns is here to stay for a little while longer, The Who's Whonicorn of Unicorns 2nicorn is coming to a bookseller near you, soonicorn!

@icandrawdinos www.garryparsons.co.uk

October 30, 2022

See a mummy unwrapped! (writing for pop-ups) Moira Butterfield

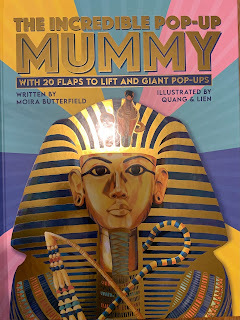

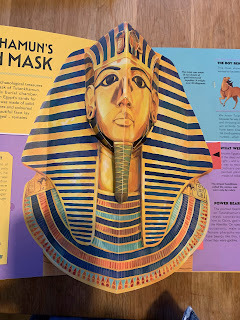

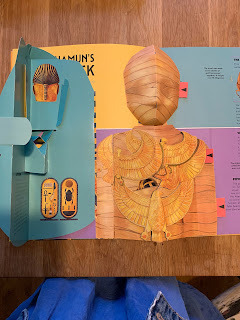

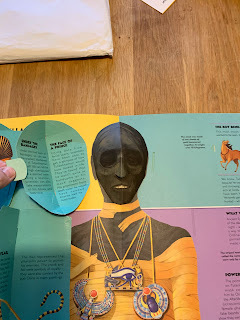

October saw the publication of a highly-illustrated book I wrote for kids roughly aged 7+. It’s called The Incredible Pop-up Mummy and it’s got 20 flaps to lift and three truly amazing multi-layered pop-up spreads. Writing for a pop-up project for any age-group is a very different experience to a normal book. It’s a team game – and with pop-ups of this complexity one might say it’s an ‘extreme team’ game! Here’s roughly how it goes.

The front cover. It's very SHINY!

The front cover. It's very SHINY!

Step 1. Writing? Wait for it….Wait for it….! You need to come up with some pop-up ideas and chat with the editor. The editor discusses it with the designer and the paper engineer – in this case the Templar in-house book wizards Kieran Hood and Richard Ferguson. No writing has been done yet – only thinking and researching. You need to know the general form of the book before you begin.

In this case the book uses non-fiction but if you were writing a fiction story for a pop-up book then you’d still need to think about how to incorporate some belter pop-up opportunities and build them into the right places in your page plan. You can only have a certain number, depending on cost, and you'd need to work out where they're likely to go in the spread plan (if you’re coming up with a brand new as-yet unpitched idea, check in bookshops to see typical extents that publishers can afford).

Step 2. OK. Go! You can start writing. You need to think about the spaces you’re going to get around the pop-up and you might need to think about flaps, too. I love a flap book for any age but flaps can be disappointing when what’s hidden beneath them is a bit ‘meh’ and not really an interesting reveal at all. They need to be worth the effort of opening them!

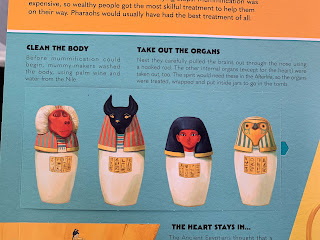

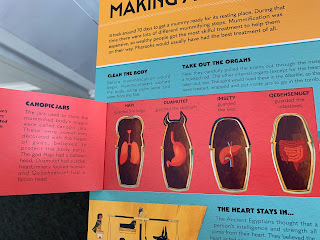

Now that's worth opening, right?

Now that's worth opening, right? Step 3. Finished? Nope. In a complicated pop-up book the writing is almost guaranteed to need changing as the paper engineering gradually comes together. In fact changes might happen right up to the last minute as the page space alters. You’ve got to cultivate patience and understanding and hold your nerve. It’ll be ok in the end….

Step 4. Finished? Nope. If your work is non-fiction an expert could get involved, making changes and suggestions. We were lucky to get Stephanie Boostra, who really has poked around Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples. She knows her stuff and was enthusiastic about the book.

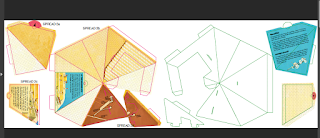

Step 5. Check it all (you may need to turn pages upside-down). Checking the layouts for a pop-up book is a bit barmy. All the bits are designed to fit on a printing sheet and they can be positioned any which way.Words can sometimes get mislaid so you need to make sure they’re all still there.

Er....Ok. Are all the words still there?

Er....Ok. Are all the words still there? Don’t be put off by this seemingly difficult process. If you ever get the opportunity to work on a pop-up remember that the secret of the job is giving the pop-up engineer great opportunities and knowing that there's a logical progression to the whole thing. It's just a bit different to an ordinary book, that's all.

Anyway, this is being posted at Halloween time and, as promised in the title, you now get to see a mummy unwrapped!

Happy Halloween!

Happy Halloween!

The Incredible Pop-Up Mummy is illustrated by Quang and Lien, and published by Templar Books.

Moira Butterfield’s currently available books include Welcome To Our World (Nosy Crow), the Look What I Found series (Nosy Crow/National Trust), the Secret Life series (Quarto), Dance Like a Flamingo and Sing Like a Whale (Welbeck), Maya’s Walk (OUP) and her latest Walker book – My Big Book of Questions About the World.

twitter @moiraworld

instagram @moirabutterfieldauthor

October 23, 2022

Goodbye - and thank you! by Jane Clarke

I’ve loved my time on the Picture Book Den, and my career as a children’s author, but now it’s time for me to retire.

I came to writing in my forties, having been an archaeologist, then a history teacher. It didn’t occur to me to try writing for children until I landed a job that involved reading picture books. So my first thanks go to the then librarian at Antwerp International School, Barbara Noels, for getting me started - and to my colleagues and students there who were my guinea pigs :-) It took me several years, and many rejections, to get published, with my first books coming out in 2001. My initial aim was to get one book with my name on it into the library where I was working, and I’m amazed to have ended up with over 130 published books. Of these, only 23 are picture books - they are the hardest of all to get published.

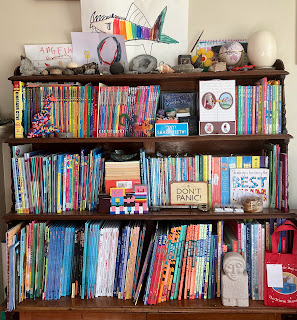

I wrote all of these and I didn't panic - much!

I wrote all of these and I didn't panic - much!The world of children’s books has been wonderfully supportive. At the outset, fellow members of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators helped me work out what I was doing, and I received a huge amount of encouragement from the late Pat and Laurence Hutchins and generous help from Tony Bradman. I’ve try to pay forward some of that help to others. I’d like to thank everyone who helped me on my way, and Celia Catchpole who saw potential in the rejection letters I sent her, and bravely took me on. It’s been a pleasure working with her and her son James at The Catchpole Agency - and also with brilliant editors like Picture Book Den’s own Natascha Biebow- who was the very first to get me a contract!

As well as providing me with an unexpected career, writing for young children saw me through some very difficult years - my mum and dad and my husband all died suddenly within months of one another in 2001, leaving me and our two teenage sons bereft. Talking animals provided a safe ‘alternative’ world where the hours passed without pain. In the tradition of picture book happy endings, my sons and I eventually flourished, and they and my four young granddaughters fill my world with loads of love, joy and laughter (not to mention unicorns, rainbows and sparkles).

I’ll still be writing the odd thing if and when inspiration strikes, but for now I’m concentrating on spending time with my friends and family (especially if it involves cake), doing lots of voluntary work on behalf of my local Lions Club to support local and international charities - and fitting in yoga, long walks, fossil hunting, book club and FitSteps. And I’m planning to get lots of use out of my bus pass. However did I find the time to write?

Thanks for having me on the Picture Book Den, and thank you for reading my posts and my picture books. I hope some of my books will be treasured in the way I still treasure some of my sons’ favourites.

I’ll sign off with the biggest thanks of all to my wonderful friends for their support, and for always cheering me on.

Love to all,

Jane x

October 17, 2022

INTERVIEW WITH HARRY WOODGATE - BY Clare Helen Welsh

We are delighted to be sharing an interview with author-illustrator, Harry Woodgate, ahead of the publication of their new picture book, Timid, which launched on 13th October with Little Tiger Press.

Dear Harry, thanks so much for freeing up your time to answer some questions for Picture Book Den. We are really excited to be showcasing your new picture book, Timid ! Can you tell us about it in three words?

Very big lion.

Brilliant! :-) What was your inspiration for the story?

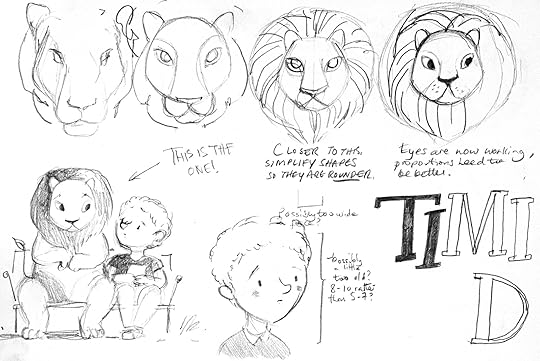

The idea for Timid began with a pun! It was the week before the very first lockdown, and I was sat in the back of a coffee shop in town with my sketchbook. I happened to doodle this big fluffy lion, and in the weeks that followed I kept wondering how to turn it into a picture book idea. Then the character of Timmy came into my head, along with the phrase, “You’re so timid, Timmy!” and the rest of the book developed from there.

Coincidentally, there is a bit of a pun in the title of Grandad’s Camper (because Grandad is more camp than his husband, obviously), so I want to clarify that this is not an intrinsic part of my writing process, it’s just that I am very easily amused.

As the book came together, I felt very drawn to the idea of presenting Timmy’s anxiety as a lion that only they can see. When you have anxiety, it can be very hard to separate yourself from your worries, so this felt like an interesting way of exploring that experience, as well as allowing for some fun characterisation and humour along the way.

Well, I'd be LION if I didn't say I'm glad those ideas came together so beautifully (Sorry!) What do you hope readers take away?

First and foremost, I hope children enjoy the book, because reading should be fun and interactive above anything else! If the fun I had making it shines through when reading, then that’s the best result I could ask for.

I also hope it reaches any children and families who will benefit from seeing an openly non-binary character in a story, because this kind of representation is still quite rare in picture books, especially when it’s incidental to the main storyline.

Finally, I hope Timid helps reassure young readers that it’s completely normal to have feelings of shyness and social anxiety, and that whilst those feelings might not ever go away completely, you can learn to accept them for what they are and not let them get in the way of what you want to do.

These are such important take aways and they all came across beautifully to me. I'm sure other readers will feel the same. Have you ever thought about what happens to Timmy, Nia and Lion after the story ends?

I’d like to think that they remain good friends, and that they continue to follow their passions together. I don’t think the Lion ever leaves Timmy, but as they grow up, I hope they learn more and more ways to accept and work with one another.

I also have this funny thing where I like to imagine all my characters as existing within one Marvel (or Emily St John Mandel)-esque universe, although this is somewhat complicated by publishing exclusivity clauses. I think it would be fun if Timmy and Nia one day met Milly from Grandad’s Camper and they all went on a road trip together.

That so interesting! Getting all your characters together would ma ke for a fantastic road trip ! Next, I’d really love to hear more about your process. How did working on Timid compare to working on your debut, Grandad’s Camper . Huge congratulations on winning the Waterstones Children’s Book Prize this year!

Thank you so much! I’m incredibly grateful and still feel a bit amazed that it happened.

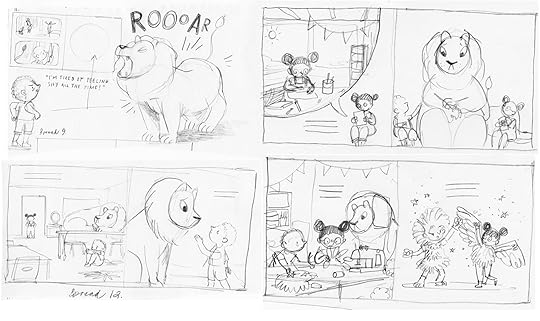

My process usually starts with a rough first draft of the text, then thumbnail sketches for each spread, and gradually I edit and develop and refine these until I’m ready to move on to final artwork. Reading aloud helps me work out things like page turns and phrasing, and making a dummy book helps to ensure there’s a nice flow and variety of compositions in the artwork. My finished illustrations are usually a mix of hand-painted, photographed, and digital textures which I collage together in Photoshop.

Of course, this process is all very collaborative. There are so many people involved in making a book and lots of conversations go on behind the scenes to help make each story the best it can be.

As for the differences between Timid and Grandad’s Camper, Timid felt a lot more structured from the beginning, probably because I had a better idea of what to expect, and what was expected of me. Also, I began working on Grandad’s Camper in the very creative, experimental environment of university, whereas I wrote and illustrated Timid whilst working from home during the pandemic, so naturally that made each experience very different and brought its own challenges.

What, in your opinion, are the most important elements of good story?

Characters whose personalities, goals and struggles feel rounded, believable, and relatable. Worlds which are fully realised and immersive, whether that is achieved through words, illustrations, or both. And most importantly, a writer or illustrator who is genuinely invested in the story they’re telling, so they can introduce the reader to things in a new and interesting light, and leave them feeling hopeful, inspired, hungry for more.

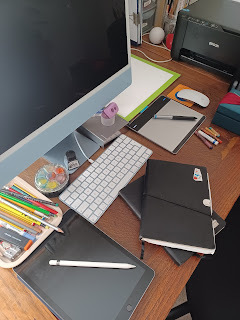

That's such good advice. Thank you for sharing! A bit more about your practice - in a typical day, how much time do you spend writing and illustrating? Can you describe your workspace?

I tend to work on weekdays from mid-morning, around 10-11am, until early evening, around 6-7pm. I used to be very bad at maintaining a regular schedule, but after enough all-nighters at university and plenty of burnout-induced headaches, I’m much better these days at establishing healthy boundaries, although of course it’s still very much a work in progress!

I’m very lucky to have a dedicated home studio, which is mostly populated by books, candles, art materials and houseplants (one of which is intent on taking over the entire room, and another of which very rudely decided to die on me whilst I was away at a book festival). By the end of a workday, it’s not unusual to find a small village of empty tea mugs on the desk beside me.

Wonderfully described - your workspace has come alive in my mind! What is the best thing for you about making picture books?

I love holding a finished book in my hands and thinking, “Oh, I helped make that!”

I love the community that exists around children’s books, and the many lovely people I’ve met through it.

I love hearing how people relate to my books, or seeing kids really engaged in art and reading when I’m running workshops or events.

All of which is to say, I find a sense of purpose and fulfilment in making books, a satisfaction in knowing that they have the potential to shape lives in a constructive and positive way, to leave an imprint on the world which hopefully makes it better than it was before.

What about the worst thing?

Sometimes it can be very difficult to strike the right balance between a manageable workload and financial sustainability, and I think that’s a challenge we’re seeing quite widely across the publishing industry which needs to be addressed. I think a constant drive for profit and growth can burden publishing employees and freelancers alike with too much work for too little compensation, and ultimately none of us can make our best work if we’re burnt out! Also, I do often wish I wasn’t sat staring at a screen as much as I am. At least with writing I can go for a walk and record myself narrating the story, but it’s not so easy with illustrations!

What piece of advice would you give a picture book creative just starting out?

Firstly, I would recommend getting to know other creators in the picture book space. Having people in the same boat who you can turn to when things get tough, or celebrate with when things go well, makes the whole experience so much more enjoyable. Trying to get through the trials of drafting and pitching alone is not fun, but it’s much better when you have a supportive network of people around you.

Also, I think it’s important to lean into a process of collaboration from the very beginning. It’s much nicer working on books where it feels like you’re all contributing and building the best version of a story together, and it’s also a wonderful antidote to perfectionism. There can be such a pressure to get things right when you’re faced with a blank page, but the reality is that every book needs work from many hands, and I find that helps relieve some of the unnecessary expectations I place on myself as a creative person.

Finally, and I realise this is easier said than done, but have confidence in your own voice! It really shows when a creator truly believes in the work they’re making, and even if it takes a long time to get there, there will be others who share that vision.

Thank you so much for your detailed answers, Harry. I'm sure the Picture Book Denners are very grateful. Lastly, can you tell us what’s coming next for you?

I have several new books coming out in 2023 which I’m really excited about…

Shine Like the Stars, written by Anna Wilson, is a gorgeous, lyrical picture book exploring our connections to the natural world. It’s publishing with Andersen in January, which is perfect timing to brush away those post-holiday blues!

Grandad’s Pride, the sequel to Grandad’s Camper, also publishes with Andersen in June to coincide with Pride month. It’s been such a joy to return to these characters, and I hope this book will allow lots of families and young people to feel seen at a time where the state of LGBTQ+ rights unfortunately feels quite uncertain and scary.

Everything else is still under wraps for the time being, but I’m very excited to share more when I’m allowed to!

Fantastic! So, lots for us to look forward to then!

Harry, it's been a pleasure interviewing you. Thank you so much for letting us peek at your side of the desk and congratulations again on your newest picture book, Timid! I've had a sneaky preview look and can confirm your readers are in for a real treat. It's available now from all good bookshops.

BIO:

Clare is children’s writer from Devon. She writes for a wide range of ages about a wide range of themes and has over 50 published titles. She founded the #BooksThatHelp initiative that aims to create honest emotional spaces for children through a love of reading and books.

October 9, 2022

Getting Hands Dirty - Exploring Textures by Diane Ewen

For this week on my turn to post, I invited Diane Ewen, a rising star in children's books to talk about her creative process and how she plays with her art. Read on and have a peek into her process as Diane explains how she goes about illustrating her picture books.

Chitra Soundar

I was always getting my hands dirty with one art form or another when I was young, and I suppose I just have the creative exploration gene.

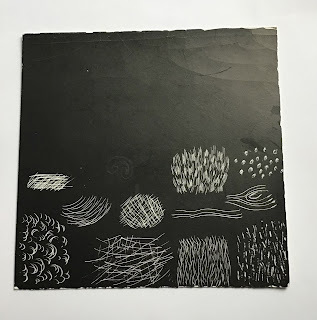

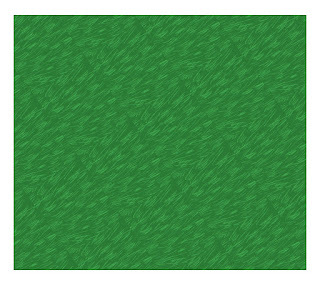

One of the big things I do is create textures to use within my picture book illustrations.

My process of creating illustrations for the books is pretty simple and generally begins with the humble pencil and ends up in Photoshop on my Mac Computer.

Once I have my main character and my illustrations drawn, the book has been through the long process of roughs and amendments. I eventually get to the colouring part, and at this point I feel that most of the hard work has been done.

For me this next phase is one which involves more of the experimental and spontaneous area of textures. I feel the book and its characters really come to life now, as I create, enhance and work away at building the whole book up.

One of my influences in the area of texture is the artist Brian Wildsmith who created some of the most beautiful and engaging foliage painting in his work. The term explosion of colour appeals to me, and I think, that similar to his work, I try to do the same in mine.

Endpaper and Interior Texture example from Coming to England written by Floella Benjamin

Endpaper and Interior Texture example from Coming to England written by Floella BenjaminCreating different textures

Scraper board was one of the early ways/mediums I began to use to get more involved with producing textures, using a method called Sgraffito, (Italian for “scratched”).

I wanted to find an easier way to create a grassy texture, so I began experimenting and found that this ‘ancient’ method of scraper board was perfect. It involves scratching the top layer to create patterns which appear on the layer underneath; it was both simple and effective …

And interestingly, you could get the same effect with wax crayons.

Creating Watercolour – Photoshop

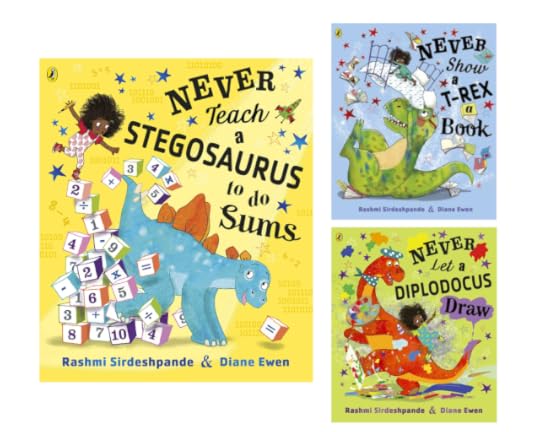

When I created the main characters for the ‘Never…” book series with Rashmi Sirdeshpande, the dinosaur characters’ skin was created in a number of ways.

In some instances, I painted a watercolour base and in others I worked with chalk pastels or oil pastels to build up the base colour, before importing them to Photoshop and manipulating.

When I say manipulate, I mean I add more line-work on top of this base; for instance, using random circles, cross-hatching, or scratch marks etc. It’s easy to do this because Photoshop is built on layers. I can add or remove things easily. So, it’s then a matter of playing around with the layers. and drawings, to get the texture I feel suits each character.

I can make virtually any textures/ pattern from scratch, then add them to the pattern palette and they are then completely unique to me.

Something that people don’t really know is that I taught myself to use the Mac which took ages and brought a lot of sweat and tears. It was worth it in the end though. I’ve chopped and changed my processes over the years, and I think that you need to as an artist/illustrator as they say a change is a good as a rest and you might even find a way of working that you like even better than you did when you started out.

Here is Diane demonstrating her process on video.

If you're intrigued and want to find out more here is Diane talking to Jane Porter about one of her picture books - from the Never... series written by Rashmi Sirdeshpande.

You can follow Diane Ewen on Twitter here and on Instagram here.

Find out more about her books on her agency website: https://thebrightagency.com/uk/childrens-illustration/artists/diane-ewen

Chitra Soundar is an internationally published, award-winning author and storyteller. Her latest picture books are Holi Hai! And We All Celebrate. She is working on new picture books out in 2023-2025. Exciting!

Find out more at http://www.chitrasoundar.com/ and follow her on twitter here and Instagram here.

September 25, 2022

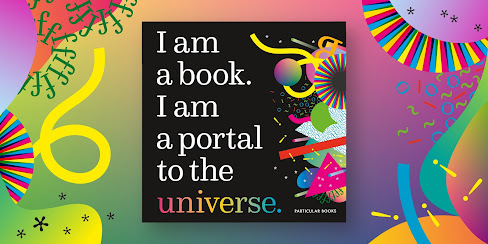

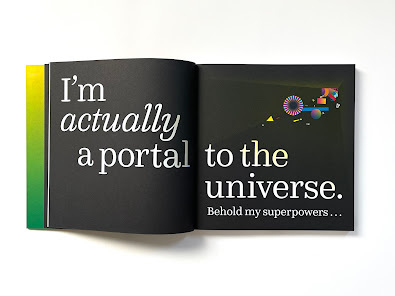

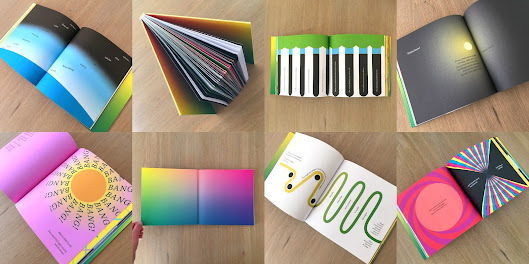

Experimenting with New Formats: How We Made 'I Am A Book', by Stefanie Posavec and Miriam Quick

Pippa Goodhart: I'm delighted to welcome to very original thinking picture book creators to the Picture Book Den. Stefanie and Miriam's 'I Am A book. I am A Portal To The Universe' won The Royal Society's Young People's Book Prize. So I've asked these creators to explain how that book came about ...

I’m Stefanie Posavec, a designer and artist who works with data. Often I co-create data artworks with my longtime collaborator Miriam Quick, a data journalist.

Within our shared practice, we explore unusual ways of communicating data, particularly those that are playful, multi sensory, and accessible to all ages, like creating a set of data necklaces you can touch and wear to learn more about air pollution (Air Transformed), or creating playful experiences to collect data from visitors in order to turn it into an artwork (National Maritime Museum).

One of our latest projects is I am a book. I am a portal to the universe., published in 2020 by Particular Books (Penguin Random House). I come from a publishing background, both as a book designer and as an author (Dear Data and Observe, Collect, Draw!), but this was my and Miriam’s first book together.

We came up with the book’s idea while brainstorming new ideas for collaboration in the summer of 2018. We knew we wanted to make a book using data, but were feeling weary of the standard data-driven, infographic book format, so we challenged ourselves to explore a different approach.

After some brainstorming, we came up with our big book idea, asking ourselves: “What if we made a book where the book itself is the measuring device?”

We began to develop the general concept and brief:

● The book itself is a measuring device, where all the measurements are embodied in the dimensions of the book itself.

● It’s a book for (almost) everyone, from children aged 8 and up to adults. Our goal was to write for the data-uninitiated or data-intimidated, people who wouldn’t normally pick up a book with ‘data’ or ‘science’ in the title. We wanted the book to be accessible enough for children, but entertaining enough for adults, with a bit of ‘bite’ and humour to it.

● No traditional charts or infographics were allowed in the book! We had an absolute ban on all of the trappings of a traditional info-book.

● Finally, our golden rule, and biggest constraint: all the data should be represented on a 1:1 scale, printed on the page at actual size.

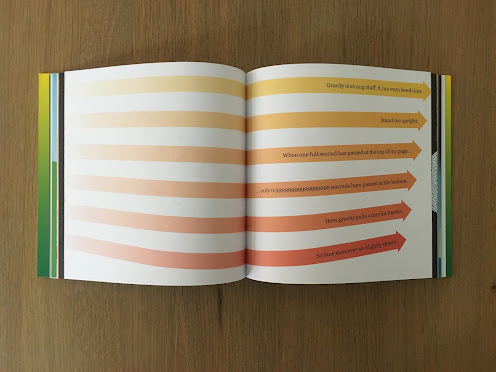

That’s a complex brief, so how did we make it happen?

Once we secured a book deal, in order to develop the book we fixed its specifications – its dimensions, paper, number of pages and more – with Penguin Random House very early on, and they made blank dummy books to these specifications that we could then work with while we developed the content.

With our dummies in hand we started by brainstorming all the ways of communicating data using its form,

carefully measuring and inspecting every component and interacting with it, bending the pages, wearing it as a hat while chatting to each other virtually … and we started to find the beginnings of ideas.

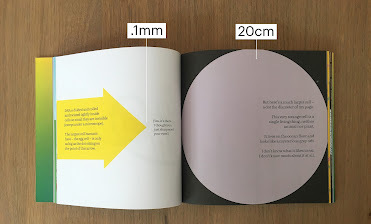

As every data fact needed to be represented on a 1:1 scale, we looked for interesting measurements around the same size as the book, so lengths between .1mm (the human-egg-sized dot on the end of the arrow on the left hand page below) and 20cm (the height and width of the book, and the diameter of the grey circle on the right, which represents one giant single-celled organism).

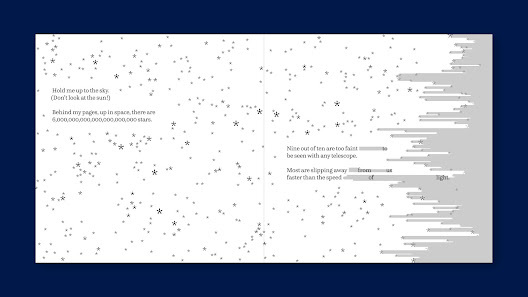

And we also explored how the reader’s interactions with the book could also communicate data: for example, in this spread the book invites you to hold it up to the sky, then tells you there are six sextillion stars behind the footprint of its two pages, when held at arms’ length.

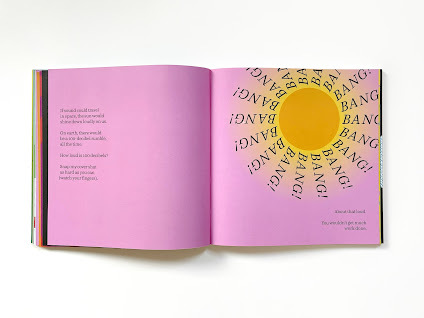

Or in another spread you might be asked to slam the book shut as hard as you can to hear how noisy sunshine would actually sound (if space wasn’t a vacuum)… this is not an e-book (and never will be)!

As for the narrative, we developed a more fleshed-out concept and narrative vision. We realised the book should speak directly to the reader in the first person and have a strong personality.

For example, on this spread, the book (rather pompously) declares itself to be ‘a portal to the universe’. It’s a universe that’s dynamic, constantly moving and changing, full of countless mysterious, elusive things flying through us or away from us.

Our goal was to make scientific ideas from this dynamic, mysterious universe accessible and approachable for readers of all ages. We tried to include concepts that weren’t common knowledge, but that anyone could grasp, with a few mind bending facts thrown in for good measure.

An example can be seen in this spread, which is about the bizarre consequences of relativity. The book tells you that, if you stood it upright on a table, time would pass a tiny fraction of a second slower at the bottom of the page than the top because it is closer to the earth’s centre of gravity.

We also made sure that all of the book’s information was fully referenced by adding a section we called ‘the small print’ – a big appendix at the back of the book that explains all the background, calculations and assumptions behind each spread.

So after 2.5 years of hard work, did we actually succeed in making a book that went beyond the typical infographic book? We hope so because just recently, we won The Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize 2021, a prize that rewards excellent, accessible STEM books written for under-14s.

Best of all, while the shortlist was named by a panel of adult experts, the final decision was based on the voting of 11,500 young people aged 8-14, and this is why winning this book prize means more to us than any other award we’ve won.

The young people’s decision to vote us the winner is testament to the fact that people respond to these new not-your-standard-infographic-book approaches that we were working with, and that there is value in pushing past standard publishing formats and trying something new.

What’s next for our shared publishing career? We are currently working on another project together that we hope will build on the success of our first book and also appeal to an all-ages audience, watch this space (and keep your fingers crossed for us)!

September 18, 2022

How to Answer Curious Questions Kids Ask on School Visits • by Natascha Biebow

I do a fair number of virtual school visits, which are hugely enjoyable ways of connecting with teachers and librarians as well as children in many parts of the world. The highlight for everyone is usually the Q & A when the students get the opportunity to ask questions and get answers to whatever they're curious about.

Other authors and illustrators will be familiar with many of these questions, like:

- Where did you get your idea?

- Why did you become an author?

- How long did it take to make the book?

And even the more personal types of questions, like ‘How old are you? and ‘How much do you earn? Are you rich?’

This is a portrait of me doing a school visit by Angely

This is a portrait of me doing a school visit by Angely

Every once in a while, a child will ask you something that gives you pause, perhaps something that you don’t know the obvious answer to and you find yourself umming . . . @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Trebuchet MS"; panose-1:2 11 6 3 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:647 0 0 0 159 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

Here are a couple that have made me stop and think:

“How many times did you mess up on the book?”

I love the idea that children think that you need to ‘mess up’ to make a book.

And indeed there is a lot of messing up!

In the first draft . . .

And the umpteenth drafts . . .

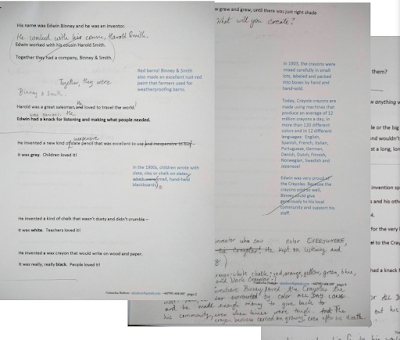

One of the umpteenth drafts of my book.

One of the umpteenth drafts of my book.And in the illustration roughs . . .

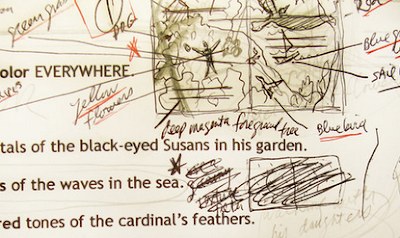

Steven Salerno's rough doodle for the first spread of The Crayon Man

Steven Salerno's rough doodle for the first spread of The Crayon Man

And sometimes even in the artwork!

Messing up is part of figuring stuff out. Messing up is to be human and it’s how we make better books and learn for next time.

Messing up

is

IMPORTANT!

But I’m not sure I can count how many times I messed up to answer that kid's question . . .

“Are you and the illustrator friends?”

Ooh, wouldn't it be great if you could just hop on the phone to your illustrator, and meet up for pancakes or pizza or something? We could share about our lives, what we are making and maybe find out we both like dogs or collecting cool rocks.

Then I’d tell the illustrator how amazing they are at interpreting the words I'd written.

And congratulate them on making visual magic between words and pictures.

And sometimes, if we were on the subject of the book we're making together, I wouldn’t be able to resist offering my two cents about this and that.

We'd be friends in no time, I'm sure!

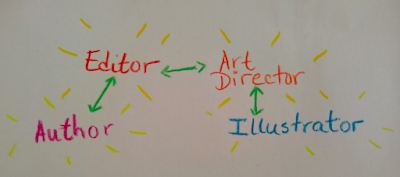

But, if you’ve ever made a picture book, you’ll know that the process is rather different. Usually, the editor and art directors are the ‘go-betweens’, the champions and project directors of the picture book. The author talks to the illustrator through them. Very rarely do they meet – at least until the book is out in the world.

This process allows SPACE for each of the author and illustrator to each create freely and unencumbered, and to carefully weigh up and consider feedback to make the best book possible.

So, authors have to trust that everyone on team publishing has the best interests of the book at heart and that every decision that is made is for the good of creating something amazing for children. Sometimes that is HARD.

I’ve made friends with many authors and illustrators with whom I collaborated with my editor’s hat on. We play together, we write letters (and emails) to each other, we share cookies and coffee and we talk about one of our favourite things – books.

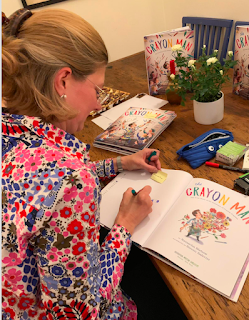

THE CRAYON MAN illustrator Steven Salerno and I have collaborated and exchanged many emails. Unfortunately, we haven’t yet met in person. I’d like to be friends with my book’s illustrator because we share something very important in common – we’ve made a book together!

I didn't know what Steven Salerno looked like until

I didn't know what Steven Salerno looked like until

he shared this photo for a joint blog post on his process.

“Do you sell every book you write?”

This question can be read in two ways:

Do you sell every book that you write?

If we sold every book that was printed that would be super super!

No bookstore returns.

No books pulped.

No more sitting in the bookstore at a signing waiting for a single person - anyone - to come and talk to you and buy a copy – the books would just fly off the shelves and the tables and you'd get to sign them all until they were SOLD OUT!

Do you sell every book you write?

Oh my goodness, wouldn’t that be AMAZING? Can you image if you wrote a book and it sold right away and you didn’t have to wait for ages and ages and ages for it to find a good home with an editor?

But on the flip side, it’s actually quite good that everything I write doesn’t end up

on children’s bookshelves because fairly often it needs polishing and loving and cooking some more, and then re-jigsawing and sometimes even

to

be

THROWN

OUT!

Luckily we have time, kind and generous critique group partners and editors to help us realize THAT.

and . . .

“What happened to Harold?”

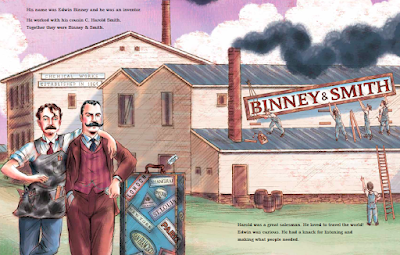

Harold C. Smith was Edwin Binney’s cousin, with whom he ran Binney & Smith, the company that made Crayola crayons. Harold was the salesman in the duo, while Edwin enjoyed experimenting and inventing.

Harold made friends all over the world on his travels selling products. He later turned to writing and philantrophy.

Edwin and Harold outside the factory (From

Edwin and Harold outside the factory (From The Crayon Man, illustrations by Steven Salerno)

You can never be quite prepared to second-guess what children might ask.

To get out of a tight situation, you can either quickly Google it under the table or . . .

. . . if you’re brave enough, admit you don’t know and make it a game. :We should all look it up, shouldn’t we?!"

@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Trebuchet MS"; panose-1:2 11 6 3 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:647 0 0 0 159 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

What curious questions have young readers asked YOU on your author visits?

_________________________________________________________________

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor

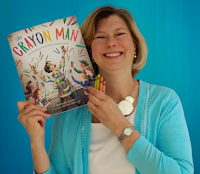

Natascha Biebow, MBE, Author, Editor and Mentor Natascha is the author of the award-winning The Crayon Man: The True Story of the Invention of Crayola Crayons, illustrated by Steven Salerno, winner of the Irma Black Award for Excellence in Children's Books, and selected as a best STEM Book 2020. Editor of numerous prize-winning books, she runs Blue Elephant Storyshaping, an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission, and is the Editorial Director for Five Quills. Find out about her new picture book webinar courses! She is Co-Regional Advisor (Co-Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. Find her at www.nataschabiebow.com

@font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1791491579 18 0 131231 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:"Trebuchet MS"; panose-1:2 11 6 3 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:647 0 0 0 159 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-ansi-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-fareast-language:JA;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

September 11, 2022

Quick ways to make little books – with Mini Grey

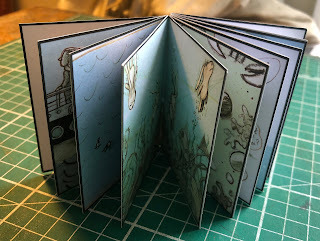

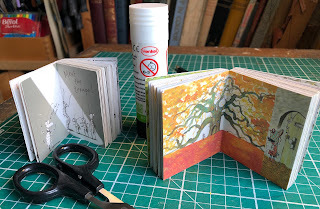

Above: 'Fight': screenprinted book by Katherina Manolessou

Above: 'Fight': screenprinted book by Katherina ManolessouSometimes what I want most to do is just cut and fold some paper into a little book. There’s something about being able to physically hold a book and turn the pages that is just not the same in a digital version. So sometimes it seems important to make a physical version of the story you’re attempting to make.

The book is an ancient technology, but actual paper may still be the most enduring way to save information and pass it on to future Earthlings.

It’s very satisfying to have made a physical little book. And you can show it to people.

And children can get huge satisfaction from making a book too.

So in this blog post, I wanted to share a few quick & easy ways that I use to make little books, and all of these ways of little-book-making are ways that children can make books too, so I also wanted to say a bit about children making books in schools.

Here we go!

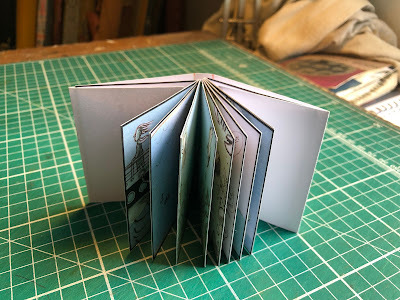

LITTLE BOOK Number 1: Stuck Down Spreads

A picture book page always has a fold in the middle. For this type of little book, you can either:

Make yourself lots of little pages the same size with a fold in the middle and work onto them....

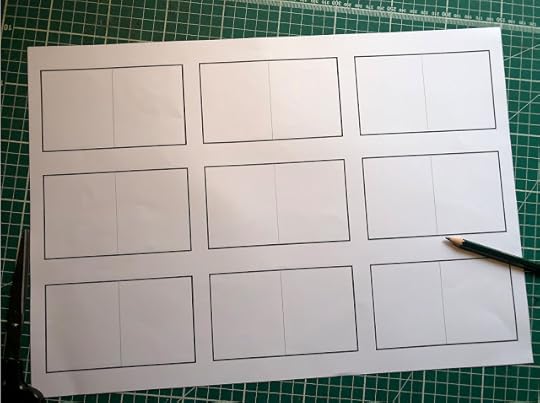

OR print yourself a storyboard to work onto, like this one...

Here's a storyboard that's been sketched into.

Here's a storyboard that's been sketched into.

Here are cut and folded printed storyboard spreads (the advantages of being able to print them is you can change the size of your pages).

Here are cut and folded printed storyboard spreads (the advantages of being able to print them is you can change the size of your pages).

Then start sticking the first to the second, the second to the third, and so on, until you have a little book you can flip through.

Then start sticking the first to the second, the second to the third, and so on, until you have a little book you can flip through.

Making teeny minibooks for the Last Wolf and the Greatest Show helped me look at the stories as a whole.

Making teeny minibooks for the Last Wolf and the Greatest Show helped me look at the stories as a whole.What’s good:

µBeing able to work small scale on a storyboard means you can work fast. µAssembling your pages means you can reorder them, can swap in and out pages that need improving, and play with your content. µYou can have any number of pages. µYou end up with a nice sturdy book. µPages don’t have to stay rectangular: here’s the dummy for the Bad Bunnies where I’ve cut into the pages to make them more magical.

You’ll probably want to give your book a cover, but don’t worry, we’ll look at covers later.

You’ll probably want to give your book a cover, but don’t worry, we’ll look at covers later. LITTLE BOOK No 2 : Zig-zag book

This is how I do it: The zig-zag book spread has an extra tab on the side, where it’s going to be stuck together, so you either need to fold yourself some pages with tabs, or use a storyboard format with tabs to print out your pages. Fold the centre fold and the tab fold for each spread. (The blank storyboard we saw earlier has gaps between spreads, so you can leave the right hand gap attached to make spreads with tabs)

Then start gluing – Pritt stick seems to be strong enough for this.

What’s good:

µAgain, you can play with the order and look at your content before assembling. µWhen your book is glued together you can flip through it like a normal book but also pull out your zigzag and see your story all at once – and that can be a nice way to display your book. µ Again, you can make your book as long or as short as you like.

Little Red Riding Hood by Caroline Whitehead. This zig zag is one folded piece of card with a slipcase cover.

Little Red Riding Hood by Caroline Whitehead. This zig zag is one folded piece of card with a slipcase cover. Those two ways are the way I always make little book dummies, because they give you the flexibility to change your spread ideas easily. But there are other formats that can be fun to play with, or good for publishing little batches of handmade books – here are a couple:

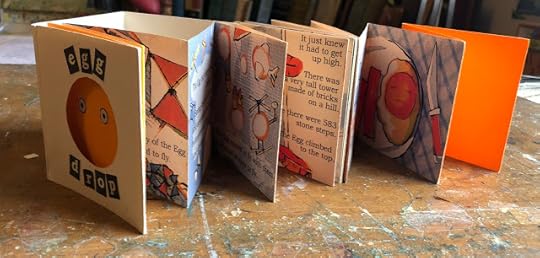

The Folded origami book

This is a nice way to make a little book out of one folded piece of paper. What’s a nice possibility is, because the artwork is on only one side, it makes it easy to photocopy/scan the finished book and print and cut/fold a batch of books.

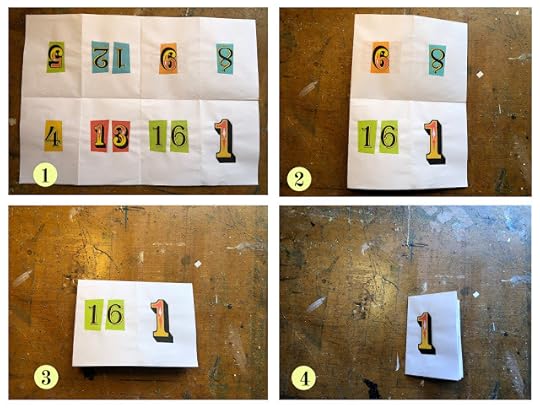

What to do: 1. Fold your paper into 8 equal rectangles by folding in half 3 times. Open it out and fold all your folds the other way, so the folds are happy to be folded both ways. 2. With the paper landscape ay round, fold in half. Cut from the centre fold to half way. 3&4. Open out and fold in half lengthways, your cut bit should open out into a box shape. 5&6 Flateen the box shape by pushing the two outside pages together and press down your book. You should have 3 inside spreads and a front and back cover.

Because your pages are all doubled up, it's possible to cut into them to pull out pop-up shapes, like this.

Because your pages are all doubled up, it's possible to cut into them to pull out pop-up shapes, like this.

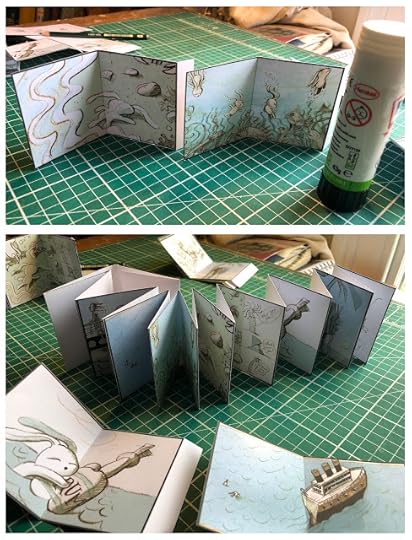

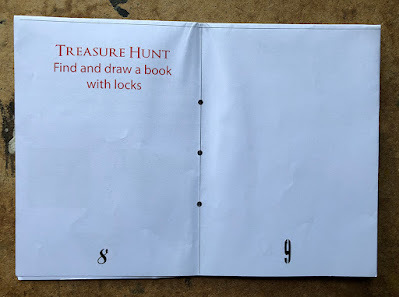

The Pamphlet Book

You can use this format to make a blank book – but I don’t really like starting with a blank empty book and filling it up – I like starting with collecting my delicious ingredients and exciting content, and then building a book with it.

But the pamphlet book format is how books really get published, so if you like super-complicated page ordering, printing a pamphlet book could be for you!

Your paper will be folded into 8, and you’ll have 16 pages in all. (32 page picture books are made of 2 of these 16 page pamphlets) So first you’ll need to make your 16 pages of content at the right scale. THEN – pop your pages onto your big page framework so they are in this order and way up (see below). (That is the most mind-boggling and tricksy part of this whole process.)

Your paper will be folded into 8, and you’ll have 16 pages in all. (32 page picture books are made of 2 of these 16 page pamphlets) So first you’ll need to make your 16 pages of content at the right scale. THEN – pop your pages onto your big page framework so they are in this order and way up (see below). (That is the most mind-boggling and tricksy part of this whole process.)

NOW – fold. First fold into 8 equal rectangles, just like for the origami book.

1. Now have the side with page 1 in front of you, with the 1 at the bottom right.

2. Fold in half so you can still see page 1.

3. Fold in half again, fold the top half down so you just see pages 1 and 16.

4. Fold in half again so you can only see page 1.

NOW sew it together. Make an odd number of holes in the main fold that will be the spine.

Start at the middle hole. For 3 holes: sew into the centre hole from the outside. Now running stitch to one of the outer holes. Push your needle though to the outside. Now form the outside, sew into your other outer hole (missing the centre hole) and push your needle through to the inside. Now, on the inside, sew into the centre hole, and push your needle through to the outside. You can tie your two thread ends around the centre long stitch, to hold it all together. You can tie decoratively or cut neatly. Now trim your book (along the top and right hand side edges) so your pages are liberated and you can flip through your newly minted book.

Start at the middle hole. For 3 holes: sew into the centre hole from the outside. Now running stitch to one of the outer holes. Push your needle though to the outside. Now form the outside, sew into your other outer hole (missing the centre hole) and push your needle through to the inside. Now, on the inside, sew into the centre hole, and push your needle through to the outside. You can tie your two thread ends around the centre long stitch, to hold it all together. You can tie decoratively or cut neatly. Now trim your book (along the top and right hand side edges) so your pages are liberated and you can flip through your newly minted book.

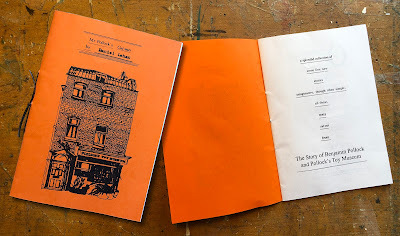

For a cover – you can either make a separate cover and stick your book into it, gluing page 01 and page 16 down to the cover. Or add an extra page to your book before sewing – this can either be your endpaper, which then gets stuck to your cover – or it can be your actual cover, as in the book above. And now, at long last, we come to

For a cover – you can either make a separate cover and stick your book into it, gluing page 01 and page 16 down to the cover. Or add an extra page to your book before sewing – this can either be your endpaper, which then gets stuck to your cover – or it can be your actual cover, as in the book above. And now, at long last, we come to THE COVER

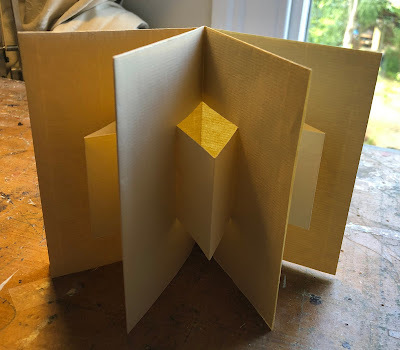

Now if you want to get super-crafty, there’s making a book-binding cover, with fabric and boards inside, but that’s more of an upholstery project and I tend to need something way quicker, so here’s how I make covers…

Cover 01: Super Simple Folded Cover

Use card, adjust your template to fit your book.

Then either: slip around the front and back pages of your inside book, or Stick your covers flaps down to firm it up, and stick page 01 and your last page into your cover.

Cover 02: Slightly Stronger Cover

I often make covers like this, but it’s a fiddlier template.

But that’s not all – you can have

Fun With Covers

Playing with your cover can mean your book can turn into a suitcase or a shop or a television…what about a house? A theatre? Books are the masters of disguise.

It's fun to just play with the different things you can do with a simple card cover.

Making Books with Children

Making a book – even a small short one – is a lot of work, and a long process. So it’s good to think small – for example making a short book for one poem could be a more do-able project than creating a complete picture book. The standard 32 page picture book format is way too much work! Work on a much smaller scale of number of pages.

I think it’s good to try working from a storyboard: you can use your storyboard sketches to make the actual pages. If you work at a small scale it is easy to change a page, to swap in an alternative, and you have less invested. It’s good to see your spreads all at once in front of you. Sometimes just ordering your images is the way to create your story. If you work at a small scale you can realise your ideas FAST, and I find drawing small is liberating. Do tests! Collage in drawings you’ve made or pictures you’ve found: cutting & sticking and drawing are all activities where you start to generate more ideas, and the doing of them is productive but not daunting.

I particularly love cutting & sticking words – sometimes just sticking your words on your double page spread can help you invent how to tell that bit of your story.

And then there’s always the possibility – for a stall at the winter/summer fair: could your class become a publishing house?

These are two books made with my son Herbie when he was at primary school. Herbie made the contents and I helped him publish them - and he sold quite a few at the school winter sale.

These are two books made with my son Herbie when he was at primary school. Herbie made the contents and I helped him publish them - and he sold quite a few at the school winter sale.Lastly:

Children making stories in school often is seen as a literacy/writing activity – and that the main outcome will be writing-based. For me, the practice of making stories involves visual story telling: diagrams, sketches, visual brainstorms. But story-making drawings don’t have to be ‘good’ drawings – they’re just a way to collect ideas. (See my post on How To Not Draw Things for more about this...) I find being able to move my elements around and being able to start anywhere sets me free, which is why collecting images and words, and cutting and moving them about is so useful. I don’t have to start at the beginning and move linearly.

The homemade book is often the only existing copy in an edition of one, a special object to be kept forever. And if you’ve managed to transform paper into the magic doorway that is a book, you’ve made something precious indeed.

Mini’s latest book is The Greatest Show on Earth, published by Puffin.

September 4, 2022

Life After the MA in Children’s Illustration at Cambridge Anglia Ruskin University by Julia Woolf

When I was invited to do another post for the Picture Book Den (the last one was in July 2013) I really wasn’t sure what to write about. But as the first post had been about studying on the MA, I thought that I should now do an update about how things have been going since graduating in 2015.

I did the part time course at Cambridge, which took 2 1/2 years. It was a great experience, which I thoroughly enjoyed and I graduated with a distinction.The course is exceptional in making one experiment with different processes and also in its links with the publishing houses. The stand that it has at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair is a great way to showcase your work to publishers with the hope of getting a book deal.

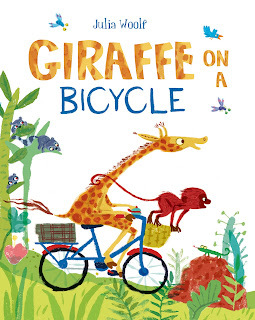

I was lucky enough to acquire my first author/illustrator book deal with Macmillan on my first visit to Bologna a year before I graduated.It was an amazing and exciting experience. My book ‘Giraffe on a Bicycle’ came out in January 2016.

So what’s happened since then? … Well, ‘Giraffe on a Bicycle’ was featured on the BBC’s Cbeebies Bedtime Stories, read by Sir Chris Hoy.

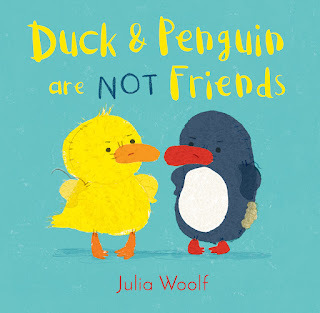

‘Duck and Penguin Are Not Friends’, (my third author/illustrated book) published in 2019 by Andersen Press went on to receive a nomination for CILIP Kate Greeenaway Medal 2020. It was also in the BookTrust’s ‘Great 100 Book Guide for 2020’.

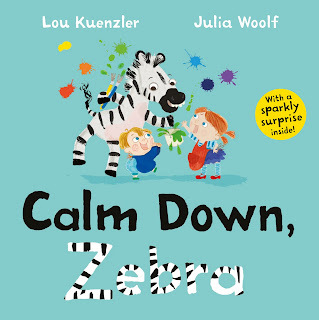

‘Calm Down Zebra (my second book with the author Lou Kuenzler) published by Faber and Faber in 2020 went on to receive a nomination at The Sheffield Children Book Awards 2020.

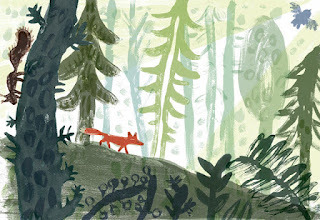

Alongside my published work, my illustration ‘Fox in the Forest’ which I made while on the MA, was the inspiration for the architects, Hawkins Brown’s design of Ivydale Primary School in South London, which subsequently won the RIBA London Award 2018 and in the same year I won the ARU Alumni Contribution to Culture Award.

So all this, and ten books later (four of which are author/illustrated), all sounds really exciting, which of course all the above was, but it doesn’t really paint an accurate picture of what’s been going on and the personal struggles of motivating oneself to produce work in the hope of a publisher wanting to give you another book deal. And it goes without saying there have been many rejections of book dummies.

I find it extraordinary how one day I can feel elated and excited by working through a new project and the next day have real feelings of doubt and not being very good at what I do. I think this had a lot to do with working on my own day in day out and looking at Instagram too much.

I miss the discussions I had with fellow students on the MA. How we would all help each other with our work.

Having come from an animation background where I had worked in a studio environment for 20 years, it was a bit of an adjustment getting used to working in isolation. I miss the advice that you could get from working alongside others. I learnt so much that way and the MA had a similar feel.I do call up and talk to my MA friends fairly frequently and we discuss our current projects and ideas. But it’s not quite the same as seeing each other in person.

Going back to instagram, and the need to be out there in the social media world doesn’t come second nature to me. Being older and not growing up in a computer environment was a bit of a struggle to get my head round. Also blowing one’s own trumpet was another thing that my generation seemed to be encouraged not to do as it was thought of as unseemly. And of course the publishers also want the next great young thing. So I do have those negative feelings of self-doubt in the very competitive world of children’s books.

There are so many very talented people out there it’s easy to feel a bit rubbish about yourself, old and irrelevant, and so that’s the other thing, teaching yourself to be positive and to concentrate on your own projects and to just get on with them. And if they do get rejected, well loads of people get rejections, so you can either try and improve on the rejected project, or put it to one side for a while and get on with something new.

But of course picture books don’t pay a great deal and do take a long time to earn out the advance.

Are publishers taking as many risks on new projects? Especially after covid and the cost of living crisis looming.

I have done rather well with PLR (Public Lending Rights) from the libraries, which is a good way to up one’s income.

I am trying to stay positive and just plod on with my new projects. I don’t have a current book deal (at the moment) but I do have some very exciting projects that I’m hoping will be picked up. At the moment I’m working on a graphic novel, which is based on the school in south London so fingers crossed it ends up in print.

I have also redone my website which is a huge relief to me as it hadn’t been updated since graduating from the MA. https://www.juliawoolfillustration.com

I’m still really passionate about my work, so onwards and upwards … hopefully!!

August 29, 2022

Drawing games to spark a narrative - Garry Parsons

Visual drawing games can be a great way to spark new ideas and unleash unexpected narratives.

Best done in groups of four or more, here are a few drawing games I've tried and tested. So invite a few friends over or gather your family to release some visual poetry and collective creativity.

Exquisite Corpse collective drawing 1927 - Max Morise, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy & Joan Miro

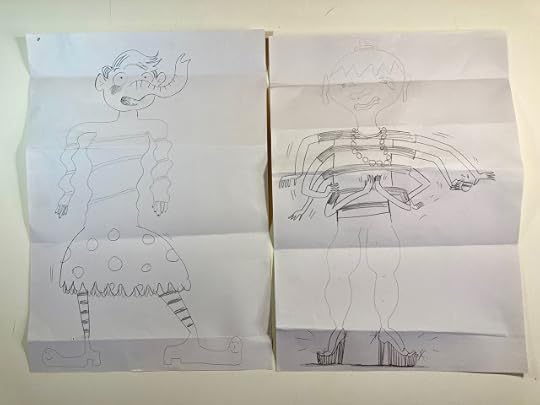

Exquisite Corpse collective drawing 1927 - Max Morise, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy & Joan MiroPencils and paper at the ready, we're going to start with a favourite of the Surrealists, 'The Exquisite Corpse' or more widely known as 'Consequences'. I'm sure everyone has played this at some point but it never fails to amuse and also gives your pencil a warm up. I will explain the rules of the original game and then offer a version I practised on delegates at a picture book conference earlier this summer which has a slight difference in approach.

'The Exquisite Corpse' or 'Consequences'.

Each participant needs a pencil and a sheet of paper. Everyone starts by drawing a head, it can be anything, animal, human whatever, but leaving off at the neck. Making sure each player's drawing is concealed from the others, players simply fold the paper over to hide the drawing but leaving the two lines of the 'neck' visible. Each sheet is passed to the next player at the same time where they continue with the torso, concealing it with a fold again once the torso is complete and passing it on until everyone has drawn a head, a torso, a waist with legs and then the ankles with feet. Pass the still folded sheets around again and take it in turns to unfold the paper for the reveal, ta dah!

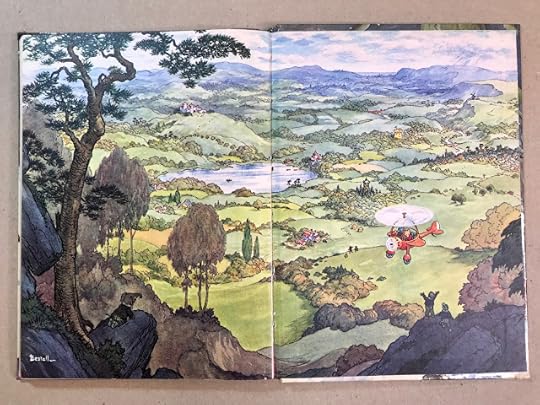

The alternative version to this I mentioned is orientated around a landscape rather than a body and is inspired by the endpapers of Rupert Annuals by illustrator Alfred Bestall.

Rupert Annual - Alfred Bestall

Rupert Annual - Alfred BestallIn his landscapes you will see the sky with a distant horizon, a middle ground, a foreground and something in close-up. So in this version of consequences everyone starts with a sky and distant horizon, passes the paper around to continue with a middle ground and so on. At any point you can add a character or hint of a character. Once the drawings are revealed challenge each player to suggest a narrative that might come from the image. Try this large scale on A3 or A2 paper for more impactful results.

Automatic Drawing or Drawing a Story from a Line.

Another visual game from the Surrealists is Automatic Drawing. Pioneered by French painter Andre Masson, the idea is to draw without thinking, trying to avoid conscious control over the picture, a kind of unconscious doodling. Try keeping your pencil in contact with the paper for some unpredictable effects.

Andre Masson - automatic drawing

Andre Masson - automatic drawingAlways with an eye on leading into a narrative, I use a version of this in the classroom with primary school children with the aim of turning a simple line into a story that they can develop into a piece of writing to illustrate. In a classroom I like to stand behind a flip chart and reach around with a pen to draw a wobbly line. The children can see that I'm not looking at what I'm drawing and my intention is to not make anything recognisable. I then ask them to tell me what they see or that they feel they might be able to turn the line into. The variety of things that are suggested is always astounding. We then choose one idea to develop and keep asking 'what happens next' until a narrative starts to form. A collective story emerges, often pretty wild but a story nonetheless!

So start by closing your eyes and making a mark on the paper, keeping it as simple as possible but with a little variety, not just a straight line. Take a moment to see what the line suggests to you and add to your line to develop it. You can turn your paper anyway you wish to get started. Then simply keep drawing or writing to develop the narrative. In the classroom, we often end up with a few sheets of drawings that have stemmed from the initial, like page turns in a picture book. As the story unfolds we give it a working title and even make a plan for the the look of the cover. Using this 'line' method works well with people who might feel inhibited or reluctant to draw.

Challenge the Illustrator

The next drawing game came form a conversation with author Josh Lacey on a train travelling to a school event we were attending together. During the conversation I nonchalantly announced that "I can draw anything". Thinking this a little arrogant, Josh asked the pupils at the school to come up with impossibly difficult things for me to draw as a challenge to the illustrator. We discovered that this was not only very funny but also a great way to begin a story narrative and set the pupils thinking about writing. This proved such good fun that we incorporated it into our school events and added a few rules...

Ask people in your group to think up an animal, a mode of transport and a scene or setting. Consider a few suggestions and settle on one idea for each topic. Combine each element into one drawing (as best you can!) and then continue to explore the narrative from the drawing by considering 'what happens next' and 'what might have happened before' and write down what you come up with.

Drawing from collective suggested topics - Tapir, a tractor and Earth's orbit.

Drawing from collective suggested topics - Tapir, a tractor and Earth's orbit.

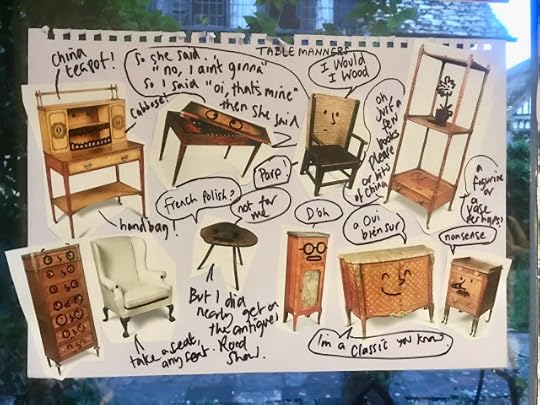

Re-Assembling Reality or sticking together cut-out images!

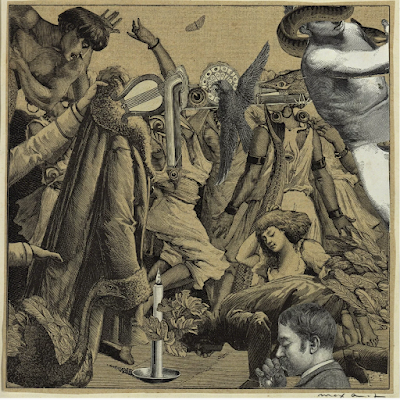

The Surrealist Max Ernst invented this method of pasting together different 'cut-out' images which have a similar look or quality, principally taken from printed publications, magazines or books, and re-assemble them into new pictures. These new 'illustrations' were often dream-like or erring on the comical or grotesque.

Max Ernst 'Women reveling violently and waving in menacing air' 1929

Max Ernst 'Women reveling violently and waving in menacing air' 1929

Collage took on lots of forms for the Surrealists but can also be good visual way to spark story narratives. I recently took part in a 're-assembly' exercise with a group of authors and illustrators who were given a pile of magazines to sift through and a pair of scissors and a sick of glue. I came up with this..

These exercises may not turn into fully a formed picture book but they are a fun and invigorating way to start the creative process and shake things up. Consider them more as creative yoga or visual warm up exercises for the creative mind!

***

Garry Parsons is an illustrator of children's books and a lover of Surrealism. www.garryparsons.co.uk

You can follow him @icandrawdinos