Brian Clegg's Blog, page 60

January 18, 2016

Snow Crash - Review

I've enjoyed several of Neal Stephenson's books, but find many of them far too long, suffering from bestselling author bloatitis, so I thought it would be interesting to get hold of a copy of his classic, Snow Crash - and I'm very glad I did.

I've enjoyed several of Neal Stephenson's books, but find many of them far too long, suffering from bestselling author bloatitis, so I thought it would be interesting to get hold of a copy of his classic, Snow Crash - and I'm very glad I did.Although not a pastiche, it depends heavily on four classics of science fiction. The obvious one is William Gibson's Neuromancer, because of the net-based cyberpunk aspects that are central to Snow Crash. (The snow crash of the title is nothing to do with skiing and everything to do with computers crashing.) However, the pace and glitteriness owes a huge amount to Alfred Bester's Tiger Tiger (that's the UK title - it was originally The Stars my Destination), while the corporate-run world has a distinct feel of Pohl and Kornbluth's Gladiator at Law, though interestingly here it's a world without any laws whatsoever. And finally there's a touch of Samuel Delaney's Babel-17, where a language is capable of doing more than simply describe things. In Delaney's book, the language is so specific that if you name something, you can construct it given only that name - here, language is capable of re-programming the human brain.

These influences, though, are only for those who are interested. If you like the kind of science fiction that hits you between the eyes and flings you into a high-octane cyber-world, particularly if you have an IT background, this is a masterpiece. Once you get over the odd name of the hero/protagonist (he's called Hiro Protagonist. Really) it is a joy to read. And despite being over two decades old, the technology really doesn't grate. Okay, Stephenson set it too early for the level of virtual reality capability, and there are too many references to video tapes, but otherwise it could have been written yesterday. What's particularly remarkable is that it is all about the internet (if not named as such) at a time when the internet wasn't widely known. This was written in 1992, yet when Microsoft launched Windows 95, it wasn't considered necessary to give any thought to the internet. That's how quickly things have changed.

As you might expect from Stephenson, there are some dramatic set-piece fights and rather a lot of violence, virtual and actual, but it also features erudite and quite lengthy library exposition of the precursor myths to many modern religions and some mind-boggling (if far-fetched) ideas about language, the nature of the Babel event and of speaking in tongues. There's also a strong female character, though today's readers might raise an eyebrow about a relationship between a 15-year-old girl and a thirty-something mass murderer. Oh, and I love the rat things.

If you find some of Stephenson's more recent books overblown, this is the one to go back to. Nicely done indeed.

Snow Crash is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com.

Published on January 18, 2016 01:31

January 14, 2016

Sometimes doing this job gives you a warm glow

I'm the first to admit that, if you can make a living doing it*, being a writer is not a bad gig. You don't have to set the alarm in the morning. It's part of your job to read interesting stuff and mooch about being creative. Admittedly the writing part is a bit of a faff, but, hey, everyone has downsides to their job. But there is one aspect of it that can be particularly pleasant - when someone says one of your books has inspired them.

I'm the first to admit that, if you can make a living doing it*, being a writer is not a bad gig. You don't have to set the alarm in the morning. It's part of your job to read interesting stuff and mooch about being creative. Admittedly the writing part is a bit of a faff, but, hey, everyone has downsides to their job. But there is one aspect of it that can be particularly pleasant - when someone says one of your books has inspired them.According to the incomparable Cumbria Crack (I never get my news anywhere else**) Keswick student James Firth, who has won a science bursary, wants to study astrophysics and has a long term aim of following Tim Peake into space. And, it seems, 'James has a fascination in astrophysics having poured through books by Stephen Hawking and Brian Clegg. He now aims to study astrophysics at university.'

I wish James every success and am genuinely delighted to have played a small part in helping inspire his fascination with science.

* This is not the easy part. Note that, according to an ALCS/ Queen Mary University study, the median professional author income from writing in the UK in 2013 was around £10,000.

** Okay, not entirely true.

Published on January 14, 2016 00:34

January 13, 2016

Does celebrity make you real?

This morning I spotted an email from my local theatre that was too good not to share, as it appeared to be selling off a comedian.

As you do, when I tweeted about this I included the Twitter address (handle? ID? none of them work well) of the comedian in question, Ross Noble, and I noticed that, like a fair number of famousish people, (presumably the ones that aren't rich enough to buy the person who already has, in this case, @rossnoble) he has resorted to putting 'real' in front of his name, making him @realrossnoble.

There are plenty of others - David Mitchell (the comedian, not the novelist) is @RealDMitchell, for instance. I assume this has happened because someone else called Ross Noble, David Mitchell (still not the novelist) etc. has already snapped up the simple form, like my @brianclegg.

It's fine, obviously, to modify your name to be both memorable and still clearly like to your name - much better, certainly than @rossnoble99 or @nobleross. But I do wonder if stars of stage and screen are the best people to apply the word 'real' to themselves? It's not that I'm suggesting that they are fictional, but my suspicion is that they have a weaker grasp on reality than most of us (with the exception of politicians and royalty of course (I wonder who has @realqueen?)).

So perhaps celebrities should consider an alternative to the 'real' prefix. How about @unrealrossnoble or @famousrossnoble or just plain @rossnobleyouveheardof. That way, they wouldn't be making unnatural claims.

Published on January 13, 2016 01:34

January 12, 2016

I don't really get music

Another group I enjoyed singling with in my youth -

Another group I enjoyed singling with in my youth -Nonessence (clearly hip and fashion-conscious)It may be a matter of having slightly different mental structures or something, but I struggle to understand the importance most people seem to place on music.

This might seem odd, as I've always loved performing with smallish groups of singers, mostly notably Selwyn College Chapel Choir, and I often play music when doing admin tasks (I can never write with music on). I've even enjoyed a few of the concerts I've attended, though if I'm honest, by about 2/3 of the way through a gig I've usually had enough and am getting a bit bored. But what I can't understand, as evidenced by the outpouring after the death of David Bowie, is the way so many people say that music changed their life or was central to it.

I'm not doing down Bowie - I think he was brilliant, creative and a one-off. But I don't understand how music can do anything to your life, or how a musician can be a hero or role model. I read, for instance, Suzanne Moore in the Guardian saying 'What he gave to me is forever mine because he formed me... He was my lodestar...' For me, music is just another type of entertainment, and if I have to give something my whole concentration as an audience member, as opposed to a performer, I'd rather it were a book or a film.

I ought to stress this isn't an attack on those who do put music at the centre of their lives, as so many seem to. But I honestly don't get it - I don't feel anything like they seem to. My loss, I'm sure, but just emphasising, I guess that all brains are not wired the same.

Published on January 12, 2016 01:49

January 11, 2016

Pilgrim's Progress - The Extra Mile review

There's something rather appealing about the concept of pilgrimage, whether or not you have a religious faith. It's a bit like a combination of the pleasures of walking and trainspotting (and I don't mean that as an insult) - there's both the exertion that is usually involved and the feeling of ticking off achievements, a medieval equivalent of a bucket list.

There's something rather appealing about the concept of pilgrimage, whether or not you have a religious faith. It's a bit like a combination of the pleasures of walking and trainspotting (and I don't mean that as an insult) - there's both the exertion that is usually involved and the feeling of ticking off achievements, a medieval equivalent of a bucket list.In The Extra Mile, Peter Stanford sets out to take in a number of centres of pilgrimage in the UK, without indulging in the actual act of being a pilgrim himself. Even though several times he is drawn into the experience, he undertakes this as an observer rather than a participant. These are mostly Christian sites, but he also takes in the pagan/Druidic possibilities of Stonehenge and Glastonbury.

I came on this book by accident - I think it was an Amazon recommendation when I was looking at something else - and I am pleased that I did. Stanford gives accounts of what he experiences, from the lively celebrations at Glastonbury to more contemplative island retreats like Iona and Lindisfarne. For me, the most interesting was probably Holy Well in North Wales, the most complete of the medieval pilgrimage shrines and a fascinating piece of architecture whatever you think of the supposed properties of the water.

I'm not sure whether it helps or not that Stanford comes across as a cool, detached observer. I assumed from his slightly fussy writing style that he was retired, but he apparently had young children at the time of his trip (mid 2000's), so was probably younger than he sounds. He is often a little sceptical of what is going on, especially where the events clearly bear little connection to the origins of the site, but never mocks the participants and is not truly critical of anything. He also occasionally admits that the spirituality of his Catholic upbringing had crept in unbidden.

If, like me, you have an interest in medieval British culture, or you want to know more about British religious traditions, which certainly extend far beyond the typical modern establishments, it is genuinely interesting. If you're a Brother Cadfael fan, you'll even discover some of the real history behind the St Winifred story that appears in the series of books. I'm not sure that The Extra Mile works hugely well as a travel book, though, and it lacks the warmth and humour of writers like Bill Bryson. But it certainly highlights several locations that won't be as well known as Stonehenge and that might be worthy of a visit.

As a book, then, it could have been more engaging, but for an insight into both early British religious practices and how they have extended into the present and have been adapted to modern ways it is definitely worth a read.

The Extra Mile is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com.

Published on January 11, 2016 04:02

January 8, 2016

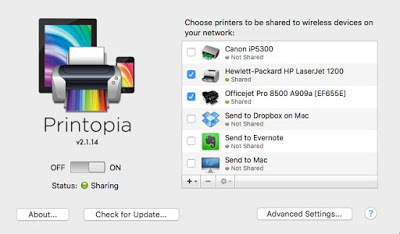

Mobile printing for Apple-heads - review

I'm sure I'm not alone in finding that I'm increasingly doing stuff on mobile devices - in my case iPhone and iPad - that I used to do on a desktop computer. If, for instance, I just want to make a quick entry on a simple spreadsheet, it can often be easier to pull it up on a mobile device. And as long the document is one where the screen size isn't too much of an issue, it generally works very well - unless I want to print something.

I'm sure I'm not alone in finding that I'm increasingly doing stuff on mobile devices - in my case iPhone and iPad - that I used to do on a desktop computer. If, for instance, I just want to make a quick entry on a simple spreadsheet, it can often be easier to pull it up on a mobile device. And as long the document is one where the screen size isn't too much of an issue, it generally works very well - unless I want to print something.Of course, you can print from iPhones and iPads if your printers support their AirPrint standard - but, inevitably, neither of mine do. (Printer aficionados might spot that my laser printer is around 15 years old.) However, I can now merrily print from the iPhone and iPad anywhere in the house, thanks to a nifty little package called Printopia.

This isn't an app - I use the standard 'send to printer' option from the mobile device. But Printopia is a cunning little add-on that sits on my Mac, which brings up my printers (and optionally various other destinations, like sending the print to Evernote or the computer) as if they were the real thing.

There's a free trial version, but it's one of the few add-ons I have willingly paid for, because it is solid and it just works. Once it's installed, it's controlled from the standard Mac settings panel (shown above) - but you rarely have to do this, because Printopia is transparent - it just lurks in the background and pretends to be AirPrint printers.

Of course, because the add-on runs on a Mac you have to have a Mac on the same network as your printers and it has to be powered up (though not active - Printopia works fine if the Mac's asleep).

I know 'people who use iPhones/iPads and have a Mac on the same network as their printers' is probably a relatively small cross-section of the world. But for those of us who fit in this niche, Printopia's well worth a try.

Published on January 08, 2016 01:32

January 7, 2016

You don't have to be a sadist, but...

I was recently doing an interview about science and science fiction to support my recent book

Ten Billion Tomorrows

and along the way I had to explain that it's not surprising that fiction (science or otherwise) usually has bad things happening in it, because without problems and challenges, there's not much of a story.

I was recently doing an interview about science and science fiction to support my recent book

Ten Billion Tomorrows

and along the way I had to explain that it's not surprising that fiction (science or otherwise) usually has bad things happening in it, because without problems and challenges, there's not much of a story.This is something that is well-known in writing circles. Almost all fiction can be summarised as 'Obstacle arises or something terrible happens. Protagonist tries to deal with it.' He or she may, or may not succeed, but without those problems, there really isn't a story. 'People have a nice time,' simply doesn't work.

But what I haven't seen discussed before is what effect this constant need to make characters suffer has on the writer. As writers, we either want to, or have to, write. (For many writers it seems to be the latter. We don't seem to have much choice in the matter.) And to write fiction we have to put our characters in difficult positions and make them suffer. So does that make us virtual sadists, getting a kick out of the suffering of our invented personas?

To date, I have published two novels. The first, a young adult SF novel, Xenostorm Rising , has a protagonist whose parents go into hiding, leaving him to fend for himself. YA authors frequently have to find ways to rip teenagers from the safety of their families, to give them the kind of independence that the Famous Five achieved simply by having a scientist uncle who didn't give a damn. Without that, the YA protagonists can't really do their stuff - but it does put the author in an unenviable position of having to either kill off or remove parents (or make them truly horrible), always a delicate task.

In the second of my novels, the murder mystery A Lonely Height , my central character, Capel, gets off pretty lightly (don't worry, he will suffer significantly more angst in the second book in the series), but of course it's inherent in a murder mystery that a fair number of the characters will be having a horrible time, and it's rare that the detective gets away with Midsomer Murders style domestic bliss for long. (I really wish that simpering wife would do something truly evil.)

Realistically, whenever we venture into fiction, the chances are that one or more characters is going to suffer. So, while you don't have to be a sadist to be a fiction author, it arguably makes the process of writing that bit more enjoyable if you are.

Published on January 07, 2016 04:16

January 6, 2016

Is objectification always a bad thing?

It's all too easy to take a widely accepted statement as a universal truth. But if we are to be thinking people, rather than knee-jerk puppets, we should always question anything presented as such a truth. So, for instance, we all know it's wrong to objectify people. But is it really? Is there any scientific basis for this assumption, or is it based on 'common sense' that objectification is inherently a bad thing?

The reason I bring it up is two recent discussions on Facebook. One was on the matter of Poldark, the BBC TV series. As usually seems to be the case with this programme, the main topic was the body of the actor playing the eponymous Mr P. This is surely just as much objectification as the old, thankfully departed Page 3 girls in the Sun, and my immediate reaction was to condemn it. But I really couldn't, because it was hard to see what harm was being done. If the women involved had been making the remarks directly to the actor, then it certainly would have been inappropriate, but is a touch of objectification really such a bad thing when it comes to images (still or moving)? After all, is n'tthat what we do whenever we produce a photograph or a painting with a person in it? Surely we shouldn't be banning all representation of people?

The second controversial discussion was one I started, having seen a couple of men haplessly attempting and failing to select a packet of nappies in a supermarket. I said 'It may be sexist, but still funny watching men in supermarket, unable to decide which pack of nappies to buy.' I got the response below:

Leaving aside the fact that it was a joke, not a 'liberal trope' (what's liberal about it, anyway? Liberals think men make great parents), in effect when we engage a stereotype like this we are once again objectifying. And certainly some stereotypes can be misused. But they are also very useful shorthand communication tools, and personally I think, in this instance, totally justified.

Is all objectification acceptable? Probably not. But has the pendulum swung too far against it? I suspect so.

The reason I bring it up is two recent discussions on Facebook. One was on the matter of Poldark, the BBC TV series. As usually seems to be the case with this programme, the main topic was the body of the actor playing the eponymous Mr P. This is surely just as much objectification as the old, thankfully departed Page 3 girls in the Sun, and my immediate reaction was to condemn it. But I really couldn't, because it was hard to see what harm was being done. If the women involved had been making the remarks directly to the actor, then it certainly would have been inappropriate, but is a touch of objectification really such a bad thing when it comes to images (still or moving)? After all, is n'tthat what we do whenever we produce a photograph or a painting with a person in it? Surely we shouldn't be banning all representation of people?

The second controversial discussion was one I started, having seen a couple of men haplessly attempting and failing to select a packet of nappies in a supermarket. I said 'It may be sexist, but still funny watching men in supermarket, unable to decide which pack of nappies to buy.' I got the response below:

Leaving aside the fact that it was a joke, not a 'liberal trope' (what's liberal about it, anyway? Liberals think men make great parents), in effect when we engage a stereotype like this we are once again objectifying. And certainly some stereotypes can be misused. But they are also very useful shorthand communication tools, and personally I think, in this instance, totally justified.

Is all objectification acceptable? Probably not. But has the pendulum swung too far against it? I suspect so.

Published on January 06, 2016 00:57

January 5, 2016

Documentary downer

It used to be ever so middle class to deny watching much television. About the only things it was acceptable to say that you viewed were the news, plays and documentaries. It was almost a mark of being educated that you liked documentaries. But, personally speaking, I have real problems with them. In general, documentaries bore me.

This can be a bit embarrassing when someone says 'Did you see Horizon on quantum physics?' or 'Did you see that latest David Attenborough?' Because I won't have done. I've never successfully watched a full episode of a David Attenborough documentary. Admittedly it's partly because wildlife films are rarely about science, but I think the main problem is that I'm too word-oriented. I enjoy good story-telling TV, but I find that factual programmes manage to take about two pages of text and stretch it into an hour's worth of documentary. I'd much rather read the two pages. (This is also why I can't be bothered with the YouTube videos people are always saying I should watch.)

So I wasn't the ideal person for someone near and dear to persuade to watch the Netflix-streamed documentary Cowspiracy . Apparently this anti-animal farming documentary is turning people into vegetarians in droves. I must admit, my immediate response to it was a strong urge to go and get a hamburger, but I'm perverse like that.

First the good news about it. It made a couple of decent points that would have made up a whole page in a book on the subject. It is ridiculous that swathes of the Amazon rainforest are being cut down to raise cattle. And American levels of beef consumption are ridiculous. And it's true that most green protest groups ignore the issue. The filmmaker showed lots of green movement representatives looking embarrassed when he brought the subject up. This was presented as being because they are funded by agribusiness (and that may be true with some US groups). But to me it came across more as embarrassment because they didn't want to admit their ignorance. Given green groups' knee-jerk response to nuclear power, it doesn't surprise me at all that they ignore farming as not having the right image for their campaigns.

But. A lot of the rest of the documentary had me shouting 'That's not true!' at the screen. (Sadly, given the subject, I didn't think at the time to mutter 'Bullshit.')

I think the biggest problem with Cowspiracy was that it was totally Americas-centric. I don't think they interviewed anyone who wasn't from America, and it was all done from the viewpoint of the pretty much unique American approach to agriculture, plus their vast meat consumption (nearly twice as much as Europeans) - but their statistics were then scaled up as if it represented how the rest of the world would become. Most hilarious in this respect were comments on dairy, given the fact significant chunks of the world can't even consume it, as they don't have the appropriate gene.

So, for instance, we had pompous American 'experts' telling us that wherever you can raise animals, you could do better raising crops. I'd like to see what crops they would grow on the Welsh mountains instead of having sheep eat grass. There were also long (long) swathes of the film about water consumption, telling us how much water we use to raise a pound of beef (all in gallons, of course). But they didn't point out a) how much this varies (I don't think those sheep are given much water) and b) how almost all the water 'consumed' in raising animals is rapidly released back into the wild. If a cow contained all the water they said was used in raising it, it would be the size of a skyscraper.

Of course America uses lots of water inappropriately for agriculture (strangely, the documentary didn't say how, for example, the almond industry, used to make make milk for the vegans the film praised, was one of the worst examples) - but it's misleading to suggest that somehow raising animals consumes vast amounts of water in some kind of permanent way. It leads to short term issues, particularly in regions of the US that aren't naturally water rich, but not to long-term global problems.

There were without doubt seriously dubious 'facts' in play. We were repeatedly told that animal agriculture produced 51% of greenhouse gasses (as CO2 equivalent). This was stated as 'fact'. Yet the figure comes from a single, non-peer reviewed paper, where the scientific consensus is around 18% - cherry picking at its worst.

However, the biggest problem was an either/or attitude. It's the same logical fallacy you often see used by Intelligent Design creationists. They say 'if mechanism A can't explain a particular biological feature then it must have been a designer. But it just means A is wrong, not B is right. Here it was 'the way Americans eat and raise meat is unsustainable.' True. So the world must stop eating meat. Which simply doesn't follow in any logical fashion.

Most hilarious were a set of images towards the end where the documentary maker 'saved' a chicken from being killed and fed assorted cows. Yet his entire argument up to this point was we shouldn't raise animals. So he should have been killing them, not 'saving' them. All emotion, no reasoning.

As you might gather, I wasn't convinced by Cowspiracy, though it did emphasise just how bad the American situation is. But more than that, it made me surer than ever that I am not the right audience for a documentary.

This has been a green heretic production.

This can be a bit embarrassing when someone says 'Did you see Horizon on quantum physics?' or 'Did you see that latest David Attenborough?' Because I won't have done. I've never successfully watched a full episode of a David Attenborough documentary. Admittedly it's partly because wildlife films are rarely about science, but I think the main problem is that I'm too word-oriented. I enjoy good story-telling TV, but I find that factual programmes manage to take about two pages of text and stretch it into an hour's worth of documentary. I'd much rather read the two pages. (This is also why I can't be bothered with the YouTube videos people are always saying I should watch.)

So I wasn't the ideal person for someone near and dear to persuade to watch the Netflix-streamed documentary Cowspiracy . Apparently this anti-animal farming documentary is turning people into vegetarians in droves. I must admit, my immediate response to it was a strong urge to go and get a hamburger, but I'm perverse like that.

First the good news about it. It made a couple of decent points that would have made up a whole page in a book on the subject. It is ridiculous that swathes of the Amazon rainforest are being cut down to raise cattle. And American levels of beef consumption are ridiculous. And it's true that most green protest groups ignore the issue. The filmmaker showed lots of green movement representatives looking embarrassed when he brought the subject up. This was presented as being because they are funded by agribusiness (and that may be true with some US groups). But to me it came across more as embarrassment because they didn't want to admit their ignorance. Given green groups' knee-jerk response to nuclear power, it doesn't surprise me at all that they ignore farming as not having the right image for their campaigns.

But. A lot of the rest of the documentary had me shouting 'That's not true!' at the screen. (Sadly, given the subject, I didn't think at the time to mutter 'Bullshit.')

I think the biggest problem with Cowspiracy was that it was totally Americas-centric. I don't think they interviewed anyone who wasn't from America, and it was all done from the viewpoint of the pretty much unique American approach to agriculture, plus their vast meat consumption (nearly twice as much as Europeans) - but their statistics were then scaled up as if it represented how the rest of the world would become. Most hilarious in this respect were comments on dairy, given the fact significant chunks of the world can't even consume it, as they don't have the appropriate gene.

So, for instance, we had pompous American 'experts' telling us that wherever you can raise animals, you could do better raising crops. I'd like to see what crops they would grow on the Welsh mountains instead of having sheep eat grass. There were also long (long) swathes of the film about water consumption, telling us how much water we use to raise a pound of beef (all in gallons, of course). But they didn't point out a) how much this varies (I don't think those sheep are given much water) and b) how almost all the water 'consumed' in raising animals is rapidly released back into the wild. If a cow contained all the water they said was used in raising it, it would be the size of a skyscraper.

Of course America uses lots of water inappropriately for agriculture (strangely, the documentary didn't say how, for example, the almond industry, used to make make milk for the vegans the film praised, was one of the worst examples) - but it's misleading to suggest that somehow raising animals consumes vast amounts of water in some kind of permanent way. It leads to short term issues, particularly in regions of the US that aren't naturally water rich, but not to long-term global problems.

There were without doubt seriously dubious 'facts' in play. We were repeatedly told that animal agriculture produced 51% of greenhouse gasses (as CO2 equivalent). This was stated as 'fact'. Yet the figure comes from a single, non-peer reviewed paper, where the scientific consensus is around 18% - cherry picking at its worst.

However, the biggest problem was an either/or attitude. It's the same logical fallacy you often see used by Intelligent Design creationists. They say 'if mechanism A can't explain a particular biological feature then it must have been a designer. But it just means A is wrong, not B is right. Here it was 'the way Americans eat and raise meat is unsustainable.' True. So the world must stop eating meat. Which simply doesn't follow in any logical fashion.

Most hilarious were a set of images towards the end where the documentary maker 'saved' a chicken from being killed and fed assorted cows. Yet his entire argument up to this point was we shouldn't raise animals. So he should have been killing them, not 'saving' them. All emotion, no reasoning.

As you might gather, I wasn't convinced by Cowspiracy, though it did emphasise just how bad the American situation is. But more than that, it made me surer than ever that I am not the right audience for a documentary.

This has been a green heretic production.

Published on January 05, 2016 00:39

January 4, 2016

Magical fantasy - The Watchmaker of Filigree Street - review

I'm not a great fan of the dominant 'swords and sorcery' arm of fantasy (think Game of Thrones), but I love real world fantasies, where a fantasy element creeps into an otherwise ordinary world - the kind of thing authors like Ray Bradbury, Gene Wolfe and Neil Gaiman excel at. The Watchmaker of Filigree Street promised to be just such a book, and I was not disappointed.

I'm not a great fan of the dominant 'swords and sorcery' arm of fantasy (think Game of Thrones), but I love real world fantasies, where a fantasy element creeps into an otherwise ordinary world - the kind of thing authors like Ray Bradbury, Gene Wolfe and Neil Gaiman excel at. The Watchmaker of Filigree Street promised to be just such a book, and I was not disappointed.Set in Victorian England against a backdrop of terrorist activities by Irish nationalists, the book (presumably due to author Natasha Pulley's personal experience) unusually mixes English and Japanese cultures of the time. What is striking about the book, reminiscent of one of my favourite books, The Night Circus , is a sense of the fantastical and magic in the air. The very solid and steam-driven world of Victorian England is set against both the Japanese village (where Sullivan conducts the first performance of the Mikado) and the exotic clockwork creations of the eponymous watchmaker.

It's in these remarkable constructions, from a clockwork octopus to a watch with a form of clockwork GPS that Pulley's imagination beautifully runs riot. While these creations are certainly fantasy, in the sense of being far beyond the realistic capabilities of clockwork, they are gorgeously conceived, and fit well with the enigmatic character of the Japanese nobleman-come-watchmaker who has surprising mental abilities. Pulley also has a genuinely interesting central character in telegraph operator and failed pianist Thaniel Steepleton, and the first two acts of the book manages to combine this wonderful touch of fantasy with a very engaging storyline.

There are a few issues. The final act sags somewhat, partly because it is so complex, which means it takes a lot of untangling, and partly because of the disappointing approach to the main female character. This is a male-dominated book, so it was good to have a strong female character who was a physicist, especially one who is attempting the Michelson-Morley experiment 3 years before it actually took place (though several years after Michelson devised the interferometer she is using). However, she is not handled very well by the writer, especially in her bizarre activities during that final act. (And she's not a very good physicist, as she regards a null result from the experiment as a bad thing, rather than the fascinating thing it really was, and that any real physicist would have considered it to be.)

Yet despite not being up to The Night Circus on overall performance, this is an impressive first novel and well worth reading if you like this kind of fantasy - one of my favourite fantasy books of 2015. I'd certainly be queueing up to buy a sequel.

The Watchmaker of Filigree Street is available from amazon.co.uk and amazon.com.

Published on January 04, 2016 02:27