Brian Clegg's Blog, page 58

February 29, 2016

A popular science blooper that stands on the shoulders of giants

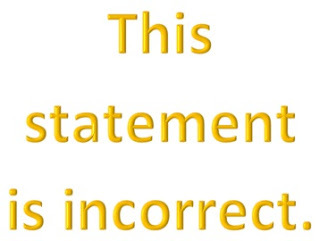

Every book I've ever read contains errors. Mine certainly do. But recently I came across a statement in a popular science book that was so outrageously incorrect that I read it three times, because I was sure I was missing something. I wasn't. Here it is, in all its glory:

Let’s be clear. This was not some self-published diatribe by an individual who thinks that Einstein was a fraud and Tesla was an alien. It was written by a scientist (admittedly from the biological sciences) with considerable experience of science communication. And it was produced by a significant mainstream publisher with all the panoply of editing and proof reading processes that occur before reaching this final copy.

If you are of an arts-oriented bent, you might be wondering what the fuss is about. It’s as if someone wrote that Botticelli painted Guernica, that Bach wrote The Rite of Spring and that Shakespeare wrote War and Peace, all rolled into one. It’s not for nothing the C. P. Snow used the Second Law of Thermodynamics as his prime example of the relative ignorance of the arts world of science in his famous Two Cultures lecture at the end of the 1950s:

I’m not going to name the author, book, or publisher responsible for the blooper. As I mentioned at the start, every book I’ve ever read has mistakes in it. But they are typically typos or silly memory errors. This (which is repeated later) is so fundamental that the mind truly boggles. I read it. I re-read it. I tried to find some way it could be ironic or some such clever thing.

But I couldn’t.

Let’s be clear. This was not some self-published diatribe by an individual who thinks that Einstein was a fraud and Tesla was an alien. It was written by a scientist (admittedly from the biological sciences) with considerable experience of science communication. And it was produced by a significant mainstream publisher with all the panoply of editing and proof reading processes that occur before reaching this final copy.

If you are of an arts-oriented bent, you might be wondering what the fuss is about. It’s as if someone wrote that Botticelli painted Guernica, that Bach wrote The Rite of Spring and that Shakespeare wrote War and Peace, all rolled into one. It’s not for nothing the C. P. Snow used the Second Law of Thermodynamics as his prime example of the relative ignorance of the arts world of science in his famous Two Cultures lecture at the end of the 1950s:

A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is the scientific equivalent of: Have you read a work of Shakespeare’s?In case you are in any doubt, Newton did indeed have a second law - of motion, which in its modern form is the equivalent of saying that force is equal to mass times acceleration. It had nothing to do with thermodynamics, which, as the name, suggests began as a study of the way that heat moves from place to place, a solidly 19th/20th century science that started as a way of improving steam engines and ended up being one of the central aspects of our understanding of physics. The names that should be attached to it are the likes of Sadi Carnot and Rudolf Clausius, who respectively laid the groundwork and effectively first expressed the law, and Ludwig Boltzmann, whose statistical version made it far, far more than had first been intended.

I’m not going to name the author, book, or publisher responsible for the blooper. As I mentioned at the start, every book I’ve ever read has mistakes in it. But they are typically typos or silly memory errors. This (which is repeated later) is so fundamental that the mind truly boggles. I read it. I re-read it. I tried to find some way it could be ironic or some such clever thing.

But I couldn’t.

Published on February 29, 2016 00:52

February 26, 2016

Diagram delights

It's time for my favourite book prize of the year. Forget the Booker. Ignore the Nobel. This is the Diagram Prize for the oddest book title of the year.

It's time for my favourite book prize of the year. Forget the Booker. Ignore the Nobel. This is the Diagram Prize for the oddest book title of the year.The shortlist has been published and it's a strong list indeed. So rather than say any more, I'm just going to let you relish those titles.

Reading the Liver: Papyrological Texts on Ancient Greek Extispicy (Mohr Siebeck) Too Naked for the Nazis (Fantom Films) by Alan StaffordPaper Folding with Children (Floris Books) by Alice HorneckeTransvestite Vampire Biker Nuns from Outer Space: A Consideration of Cult Film (MKH Imprint) by Mark Kirwan-HayhoeBehind the Binoculars: Interviews with Acclaimed Birdwatchers (Pelagic Publishing) by Mark Avery and Keith BettonSoviet Bus Stops (Fuel) by Christopher HerwigReading from Behind: A Cultural History of the Anus (Zed Books) by Jonathan Allan If I have a personal favourite, it would be the Biker Nuns, except this is clearly constructed specifically to be bizarre, so I rather incline (so to speak) to Reading from Behind.

You can find out more at the prize's administrative home, The Bookseller.

Published on February 26, 2016 03:17

February 25, 2016

How long is a piece of string?

String theory is something that I've been highly sceptical about for some time, influenced by books like

Not Even Wrong

and

The Trouble with Physics

. This meant that a recent book,

Why String Theory?

by Joseph Conlon has proved a very interesting read to provide an explanation for the popularity of string theory among physicists, despite its apparent inability to make predictions about the real world.

String theory is something that I've been highly sceptical about for some time, influenced by books like

Not Even Wrong

and

The Trouble with Physics

. This meant that a recent book,

Why String Theory?

by Joseph Conlon has proved a very interesting read to provide an explanation for the popularity of string theory among physicists, despite its apparent inability to make predictions about the real world.I can't say the new book has won me over (and I ought to stress that, like Not Even Wrong, it's not an easy read), but what I do now understand is the puzzle many onlookers face as to how physicists can end up in what appears to be such an abstruse and disconnected mathematical world to be able to insist with a straight face and counter to all observation that we need at least 10 and probably 11 dimensions to make the universe work.

It seems that string theory emerged from an attempt to explain the strong force back in the late sixties, early seventies. The idea of particles as tiny strings, rather than point particles, seemed to provide an explanation for the strong force, however the only way to make it work required the universe to have 26 dimensions (25 spatial, one of time). This was all looking quite good (if weird, but quantum theory has showed us that weird is okay), until the new collider experiments showed the sort of scattering you'd expect from particles, not strings - and along came quantum chromodynamics, requiring only the standard 4 dimensions, blowing string theory out of the water.

However, the more mathematically-driven physicists loved string theory because it was elegant and seemed to hold together unnaturally well, even if it didn't match the real world. They continued to play around with it and eventually massaged it from what was intended as a description of the strong interaction into a mechanism for quantum gravity (or more precisely several mathematical mechanisms). The good news was that this did away with the 26 dimensions, though the bad news was it still required at least 10. Again, there was no experimental justification for the mathematics, but in its new form, mathematical things started to click into place. There was a surprising effectiveness and fit to other mathematical structures. The approach even fitted a number of oddities of the observed particle families. So the abstruse mathematics felt right - and that, essentially is why so many theoretical physicists have clung onto string theory even though it has yet to make new experimentally verifiable predictions, and has so many possible outcomes and all the other problems those books identify with it.

What Why String Theory? isn't very good at, is giving a feel for what is going on in the brains of the physicists in the way ordinary folk can understand (the author is himself a theoretical physicist), so I thought it might be useful to share an analogy that seemed to fit well for me. We're going to do a thought experiment featuring a civilisation that does mathematics to base 5, rather than the familiar base 10. So they count 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 20, 21... For some obscure reason they use the same numbers as us, but only have 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. Now these people have come across some textbooks from our civilisation. And they see all those numbers, which make a kind of sense, except there's some weird extra symbols.

Before I go into what they do, I ought to defend the base 5 idea, in case you're wondering why any civilisation would not sensibly realise they could count on the digits of both hands, but rather stuck to the 5 fingers and a thumb of a single hand. This isn't because the civilisation has a strange one armed mutation, it's because they were cleverer than us. How many can you count to on your two hands? Ten. But my civilisation can count to 30. This is because they don't regard their left and right hands as equivalent, but as two totally separate things with different names. The left hand has five digits. But the right hand has five handits. (Bear with me.) When they count on their fingers, they go up the digits of the left hand just as we do. But when the pinkie goes up, they close the whole left hand and raise the pinkie of their right hand, representing five. They then count up on the left again, but when they get a full hand they raise the second finger on their right hand, and so on. Instead of just working linearly across their fingers and thumbs, by working to base 5 their hands become a simple abacus.

So, back to interpreting our base 10 documents. Some rather wacky mathematicians in this society start playing with using bigger bases than base 5. There's no reason why, no application. It's just interesting. And when they happen on base 10 - so they're counting 1, 2, 3, 4, A, B, C, D, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 1A, 1B... they get a strange frisson of excitement. This isn't the same as the system used in our documents, where the 12th character in the list is 7, rather than C. But suddenly the two kinds of mathematics start to align. Calculations that didn't make any sense suddenly start to click.

In a hugely simplified analogy, this seems a bit like the string lovers' reason for sticking with their theory. It has that same kind of neat mathematical fit. It seems to work too well to be just coincidence. All those extra dimensions and intricate mathematical manipulation don't seem natural, any more than working to base 10 seems natural when you think of left and right hands as totally different things. But it doesn't mean there's not something behind it. I hope the analogy helps you - it certainly helped me to devise it!

Published on February 25, 2016 00:23

February 24, 2016

How low can you go?

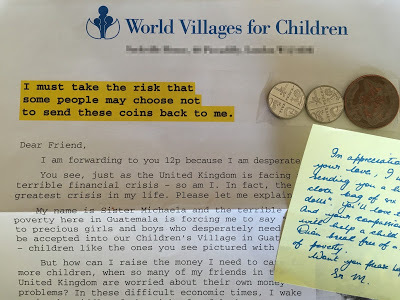

I support a number of charities, but like many people I have been appalled by the way that some of these organisations have not realised that in encouraging people to do the decent thing and help others, they also need to treat their donors decently, rather than considering them idiots to be manipulated and squeezed out of every last drop of cash. It's a very unpleasant case of 'the end justifies the means' - and as usual, this is a motto that doesn't hold up well to scrutiny.

I support a number of charities, but like many people I have been appalled by the way that some of these organisations have not realised that in encouraging people to do the decent thing and help others, they also need to treat their donors decently, rather than considering them idiots to be manipulated and squeezed out of every last drop of cash. It's a very unpleasant case of 'the end justifies the means' - and as usual, this is a motto that doesn't hold up well to scrutiny.The reason I bring this up is I've just come across the most cynical and unpleasant attempt to manipulate I've ever seen. I thought certain charities that send unrequested gifts like pens and mats in the hope of guilt tripping the recipient into paying were bad. But this is a new low.

Along with an apparent handwritten Post-it note - always a sign of dubious marketing - the letter from this charity, World Villages for Children had attached to it 12p. Twelve pence as cash. Actual money. They sent potential donors money. Why would they possibly do this? The letter from the charity explains that the author, Sister Michaela - the director of the charity, is sending me this 12p because she is desperate. What she wants me to do is send the 12p back to her, along with a cheque for at least £10 to help starving children in Guatemala. (If I do, apparently she will send me a bag containing six little 'worry dolls'.)

This is not a reason for sending 12p to me. There is only one possible reason - it is a marketing ploy. We all get junk mail that goes straight in the bin. But it is very hard to throw cash away. Especially cash that has been given to you by a charity. And for that matter, it feels evil just to put it in your pocket. Not to respond makes you feel guilty. It is top class manipulation.

Unfortunately, I don't like being manipulated. It's why I wouldn't watch the likes of the The X Factor or Britain's Got Talent, with their endless audience manipulation tricks. And it's why I'm not going to do what's intended of me here. I won't be sending that 12p back to them - I will be putting it in the collecting box of a charity that I support, such as the British Heart Foundation or The Children's Society.

I don't like to be repetitive, but I can't think of another adjective than cynical that so well describes this type of marketing.

*UPDATE* - Thanks to David Buick for pointing out that this approach has been going on for at least 10 years from this discussion.

Please note, if you comment, do not make any remarks suggesting that this charity's mailing is illegal or attempting to do anything illegal, as such comments would have to be removed as they would make this blog post liable to a takedown order, a mechanism often employed by those using this kind of marketing (see this post for details). The charity's methods are legal. But they are not acceptable.

Published on February 24, 2016 01:49

February 23, 2016

You should never go back

Image from WikipediaGenerally speaking, I find the motto 'never go back once you've moved on' a helpful one. Although I've broken it pretty regularly, I usually find I shouldn't have attended that school reunion or whatever. However, it's a lesson that TV and filmmakers rarely consider, as I've been discovering with the new X-Files.

Image from WikipediaGenerally speaking, I find the motto 'never go back once you've moved on' a helpful one. Although I've broken it pretty regularly, I usually find I shouldn't have attended that school reunion or whatever. However, it's a lesson that TV and filmmakers rarely consider, as I've been discovering with the new X-Files.I was looking forward to the rebooted series after a 15 year break. The timing could not have been better. We got through the last DVD of the complete box set the same week the first episode arrived on a UK channel. And it's okay. But there's something rather upsetting about it.

It's not just that David Duchovny looks really worldworn and tired. Or that Gillian Anderson looks emaciated and zoned out compared to her far better recent UK TV appearances. It just seems far too much like 'more of the same.' I wanted to wait until episode 3 to give a verdict, as it was written by the man who wrote my favourite episode ever, the season 3 'Jose Chung's "From Outer Space"', which is hilarious and mind-bogglingly twisted. Admittedly episode 3 did have some fun moments, notably Scully telling Mulder, as he played with his smartphone, that he ought to stay away from the internet. And it had a very neat twist in the plot, which I won't reveal. But both the script and the acting was like seeing someone who once was on top of their game going through the motions.

For years, I hoped that they would make a new series of my favourite TV show ever, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. But now I realise that it would be a mistake. The world moves on. So do stories and actors. I'll probably stick with X-Files for this season. But it's a bit like watching Bruce Forsyth in the latter years of Strictly. It's with as much a sense of sadness as pleasant familiarity.

Published on February 23, 2016 01:46

February 22, 2016

Politics has got interesting

I've always been interested in politics and take the opportunity to bore friends on the subject on a regular basis in revenge for them boring me with sport. But it takes a particularly inward-looking person not to think that politics has got interesting (sadly sport never will achieve this).

I've always been interested in politics and take the opportunity to bore friends on the subject on a regular basis in revenge for them boring me with sport. But it takes a particularly inward-looking person not to think that politics has got interesting (sadly sport never will achieve this).It started with the Scottish referendum, took on speed with the potential US presidential candidates and is now back with us over here for a potential Brexit.

Underlying all these events is a dissatisfaction with the status quo and the political establishment - and it really is about time. I'm not going to comment on the US situation as its not my country (though a Trump / Sanders or even a Trump / Clinton election would be fascinating), but I can certainly reflect on the possibility of a British exit from the EU, where I'm a floating voter, currently leaning slightly towards the out side.

I am opened to be swayed, but please don't try using ad-hominem attacks on individuals, on either side of the debate. I find it amusing that those who deride the Out camp for including the likes of Nigel Farage and George Galloway are usually the same people who want bank bosses hung from the lampposts... while apparently failing to spot that said bosses are firmly in the In camp. So for once, try to make a political argument without simply calling people names. If you arguing for In, remember you are in bed with David Cameron and George Osborne.

Here's my starting point. There are clearly pros and cons of In and Out. (Sadly, Dave's option of 'shake it all about' didn't deliver much.) But there is no doubt that EU regulations put significant difficulties in the way of our deciding our own fate, and the UK is a very different beast to most of Europe. Companies moan that leaving the EU will be bad for trade. Personally, though, as a small business owner, I find it much easier to sell to the US or Australia than the EU. In fact I've had to give up selling ebooks directly to the EU altogether because of their ridiculous regulation that EU businesses have to pay VAT on e-goods at the level that applies in the buyer's country to that country.

Against leaving, I can certainly see that Brexit would cause an upheaval, and it seems very likely that EU countries would punish us by taking it out on us any way they can. But rather than put up a straw man, I thought I'd use a well-reasoned 'why stay' argument from this article in The Guardian by Timothy Garton Ash.

Before we hit any sensible arguments, let's take on Ash's bizarre moan that non-British EU citizens who live in the UK won't be able to vote in the referendum. That's surely less of an issue than the way non-Scottish British citizens weren't allowed to vote in the referendum to split up the UK - yet (and I may be maligning him, as I certainly didn't read everything) I don't remember Ash complaining about this. Whatever, this is an irrelevancy.

So what are Ash's arguments, and do they sway me? In summary they appear to be:

It would be madness to allow Britain's membership of the EU rest on how effective Cameron's emergency brake was.Out is riskier than In. We know what In is like, but not Out.The negotiation will be painful.It's cold outside - Norway and Switzerland don't have fun.The EU helps keep us safe from terrorism.It would be hard on Ireland.Scotland would leave the UK.At first sight, an impressive bunch of arguments, but to be honest, they're mostly unfounded rhetoric. The first is true, but irrelevant. It isn't a major reason for wanting to leave. The second is almost true. But 'riskier' is the wrong word. Far better is 'more uncertain.' Because the 'riskier' argument only applies if being In isn't bad. To take an extreme example, if you were faced with a choice of being executed or attempting to escape, the escape is more uncertain, but staying is riskier. If you believe staying is bad for Britain, Ash is using a pointless argument. If you believe it's good, then it's self sustaining. In effect it's a concealed circular argument.

The negotiation will be painful? Absolutely. No argument about that. If you get yourself into a mess it usually is painful to get out of it. But that doesn't mean you shouldn't try. This is probably my strongest wavering point because I believe some countries, notably France and the Eastern Europeans, will be as bloody minded as they can and make it as painful as possible. So definitely a consideration, but not an argument for not doing the right thing, should Out be the right thing.

It's cold outside. Possibly. But, leaving aside Switzerland seems to do quite nicely, these are both far too small a country to make a realistic comparison. Canada might be better. But to think that other countries, especially the US and the Commonwealth countries, won't do a trade deal with as big a market as the UK is ludicrous. Some businesses will end up worse off. Others will thrive from losing EU red tape. It's nuanced and certainly not a deal breaker.

The EU helps keep us safe from terrorism. Really? Evidence? Certainly sharing intelligence helps, but do you think EU countries will stop sharing intelligence and risk their own security just to spite us. Whereas having full control of borders can, in principle, have a positive effect on reducing the terrorist threat.

It would be hard on Ireland. So? Much as Ireland thought about the UK when it set corporation tax so low that all those nasty multinationals based their HQs there rather than the UK? I don't remember all those Irish politicians saying 'What about the negative impact on the UK?' And as for Irish workers in the UK, this hardly started with the EU and it wouldn't stop without it. We won't stop having a special relationship with Ireland just because we leave the EU.

Oh, yes. And the clincher. Scotland would leave the UK. Firstly this isn't a fact, it's a hypothesis. The i newspaper today suggested that it's one thing for Nicola Sturgeon to make the threat and it's another for a referendum-weary electorate, knowing that Scotland can no longer rely on oil revenues, to back her. But even if it were the case, as I mentioned at the time, I'm all in favour of Scottish independence. I think it would be a large benefit for the rest of the UK. So this isn't an anti-argument for me.

There we have it then - Mr Ash has failed to persuade me. But I am genuinely unsure which way to vote and would love some more effective arguments. Tell me why I'm wrong...

UPDATE - A couple of early contributions to help persuade me otherwise.

Mark Fielder on Facebook suggests that:

One is the lack of any coherent plans should there be an exit from the EU.

Second is that an out vote triggers a bloodbath in the Tory party that allows a much harsher group of politicians to take over.

Thirdly, if we don't like it and want back in, it'll be on "their" terms, including the Euro. Right now, we're in the EU largely on our terms.

Some fair points. There has been some work done, I believe on wargaming the impact of exit and how to deal with it, but I don't know what the plans are. Some would argue that your second point would be good, as it means they're less likely to get re-elected. And I'd have thought the obvious outcome would be Boris taking over, which I'm not sure would be a huge shift to the right. And thirdly - I don't think we're likely to want back in any time soon if we leave. And that scenario assumes the Euro doesn't collapse entirely - too speculative to be helpful.

Alexander Armbruster on Twitter points me to this article by Anatole Kaletsky.

The main arguments seem to be:

It won't happen anyway because the Out camp will be split and the public won't go that way.There will be huge economic costs because of our dependence on services.There will be no political benefits.The first argument isn't argument to change the mind, just a prediction, so irrelevant for my purposes.

The second argument may have an element of truth, but makes use of the weak Norway/Switzerland model. The UK is a much bigger market for European goods and services than these countries, and European countries would have a lot to lose if their actions produced a trade embargo. I'm really not convinced that the only way they would tolerate our service sector is if it were neutered.

The third point is just a statement - no argument is provided.

Sara Crowe on Facebook points to this pro-Brexit article which points out it is possible to be anti-EU without being anti-Europe or a 'little Englander'.

Published on February 22, 2016 02:40

February 12, 2016

Time for more murder

After some very positive responses to my first Stephen Capel murder mystery I'm delighted to say that the second book,

A Timely Confession

, is now available.

After some very positive responses to my first Stephen Capel murder mystery I'm delighted to say that the second book,

A Timely Confession

, is now available.In the sequel to A Lonely Height , we find Stephen Capel settled into his first parish in the village of Thornton Down. As Christmas approaches, an unlikely confession of murder throws Capel into a complex and dangerous investigation. A software developer has been killed just before the launch of a make or break new product. While trying to help those left behind, Capel is pulled into the mystery of who really killed Mark Nelson. As Capel attempts to cope with an upheaval in his private life and to help those whose lives are torn apart by a second murder, he must search the snow-covered streets of Bath for answers before another victim dies.

It's just £6.99 for paperback or £1.99 on Kindle.

Nothing like a good murder to get you through the winter...

Paperback:

Kindle:

Published on February 12, 2016 01:46

February 11, 2016

What is a paradox? It's paradoxical

Is the definition of a paradox paradoxical? Before we get into a philosophical spiral, this thought was inspired by a complaint I received when I published a review of a book about the Fermi paradox. Mark Hogarth remarked 'They'll call anything a paradox these days.' When I pointed out the name Fermi paradox dates back to the 50s, he responded 'Yes, I know, but you gotta agree that the word 'paradox' is rarely used properly... here it's just a puzzle, like the twin 'paradox'. Now Russell's paradox - that IS a paradox.'

Is the definition of a paradox paradoxical? Before we get into a philosophical spiral, this thought was inspired by a complaint I received when I published a review of a book about the Fermi paradox. Mark Hogarth remarked 'They'll call anything a paradox these days.' When I pointed out the name Fermi paradox dates back to the 50s, he responded 'Yes, I know, but you gotta agree that the word 'paradox' is rarely used properly... here it's just a puzzle, like the twin 'paradox'. Now Russell's paradox - that IS a paradox.'So was Mark right? Have many of us (me included) been using the term incorrectly? So you don't have to, I delved into the trusty source of all things wordilicious*, the Oxford English Dictionary. And got quite a surprise.

Apart from an obsolete usage, the dictionary's first definition is the one that I use - a statement that appears to contradict itself or be ridiculous, but which turns out to be well founded or true. Rather confusingly, the second definition is an almost opposite version which I know some people use, making a paradox a not-so-obvious fallacy. And the third definition is the logician's version, which makes a paradox an argument that appears to be sensible and based on logical principles, but which leads to a conclusion that is, as the OED coyly puts it 'against sense.' Like Russell's paradox** or the rather crude example I've used as an illustration above.

However, what is really interesting is that (apart from the obsolete meaning) my definition has the oldest citation, going back to 1569, the negative definition is almost as old, with the first example dating from 1570 - but the logician's definition has no evidence before the 20th century (in fact Bertrand Russell himself in 1903 is the first usage they know of).

So, interestingly, Mark's complaint was back to front. It's not that they'll call anything a paradox these days, but rather that logicians have taken a word with a long established meaning and (relatively) recently given it a different one. Don't you just love words?

* Sadly, 'wordilicious' isn't in the OED. But it ought to be.

** Very crudely, Russell's paradox, which requires some basic set theory goes something like this. Imagine we've got the set of all sets that are members of themselves (lets call it the SELF set). So, for instance, the set 'dogs' is not in the SELF set, as the set 'dogs' is not a dog. But the set 'things that aren't dog's is in the SELF set, because it isn't a dog.

The paradox arises when we consider the set of things that aren't in the SELF set. Is that set in the SELF set? If it is in the SELF set, then it isn't in the SELF set - which doesn't make sense. But if it isn't in the SELF set, then it's not a member of itself, so it is in the SELF set - which also doesn't make sense. But it does make your head spin.

Published on February 11, 2016 01:28

February 10, 2016

Stop Teslaing me

When I ask not to be Tesla'd, I am not referring to the electronic stun guns of the TV show Warehouse 13, but pointing out that I really would prefer it if those of you who like to put 'memes' (yuck, horrible word) on Facebook would stop sticking up the kind of guff illustrated on the right, which purports to be Tesla 'describing a cell phone.'

When I ask not to be Tesla'd, I am not referring to the electronic stun guns of the TV show Warehouse 13, but pointing out that I really would prefer it if those of you who like to put 'memes' (yuck, horrible word) on Facebook would stop sticking up the kind of guff illustrated on the right, which purports to be Tesla 'describing a cell phone.'There are a number of problems with this. One is that Tesla didn't have a good grasp of electromagnetic radiation, nor did he accept quantum theory, so he would have had serious problems with the mechanisms required to make a mobile phone work.

More to the point, though, Tesla's handwaving remark was in a long tradition of broad predictive comments which certainly show that an individual is open minded, but do not necessarily indicate that they are inventing something ahead of its time.

For instance, I dearly love the thirteenth century friar Roger Bacon - so much so that I've even written a book about him. But no one sensible would suggest that Bacon understood television or aircraft. If, however, I use the 'Tesla foresaw X' approach, he seemed to predict both. In one short burst in a letter to an acquaintance, for instance, he listed self-powered ships, the horseless carriage, the flying machine, something that sounds like a pulley system, and a diving suit or diving bell, most of which would not become practical for another 600 years.

Elsewhere he wrote:

We may read the smallest letters at an incredible distance, we may see objects however small they may be, and we may cause the stars to appear wherever we wish. So, it is thought, Julius Caesar spied into Gaul from the seashore and by optical devices learned the position and arrangement of the camps and towns of Brittany.Such devices are very unlikely to have existed in Bacon's day (let alone Julius Caesar's) - the first microscopes and telescopes would not come along for about 300 years. And to make some of Bacon's claims true would need TV rather than a simple optical system.

Admittedly it's possible that Bacon achieved something like a crude telescope and/or microscope by messing about with lenses - but certainly nothing capable of what he described, nor would he understand how to do it. Bacon was not 'describing a telescope' any more than Tesla was 'describing a cell phone.' Tesla was speculating, given the knowledge of the time, as many others did, what was possible in principle. And that's a very different thing. Nikola Tesla was one of the greatest electrical engineers ever, but this kind of myth building doesn't do science any favours.

Published on February 10, 2016 01:35

February 9, 2016

The book event horizon

Mostly books I won't re-read, as these

Mostly books I won't re-read, as thesefour shelves are books wot I wroteWhenever we have tradespeople in the house, they tend to point to my wall of books and say something like 'Someone likes reading.' Leaving aside the sad reflection that having a few bookcases is now comment-worthy, it brings to mind another slightly depressing thought.

I probably have about 1,000 books on the shelves (I halved the collection when we moved 6 years ago, but it grows back), almost all of which I have read, but I keep them in case I want to re-read them.

Now, let's say I've got about 20 years of reading left in me. I read about 60 books a year, but of those 2/3 are new. So that's 20 re-reads a year. So, realistically, at maximum, around 400 of those books are going to be read again. Which seems a shame.

Note that I'm not advocating throwing most of them out. I don't know which I will re-read, and I want a choice. (A friend recently said he re-reads The Lord of the Rings every year. It seems such a waste if you do have a book event horizon looming.) However, what I have started doing is if, like the book I'm re-reading at the moment, I think 'I'll certainly never read that again,' I do dispose of it, if only to make a bit more room on the shelves.

Published on February 09, 2016 02:06