Brian Clegg's Blog, page 57

March 24, 2016

Bring on the airbrush

Way back in 2012 I reviewed a product called Portrait Professional, which allowed the user to touch up a photo of a face using simple controls, rather than manually fiddling about in something like Photoshop. Now I've got my hands on its successor, PortraitPro, and it's streets ahead in both sophistication and ease of use - which can't be bad. In fact it's scary just how much it does.

Facial feature identificationGiven a photo of a person, the software analyses the face and identifies the facial features - this process is automatic, but usually needs some slight manual tweaking, for example to make sure it exactly follows the line of the teeth - but that's just a matter of dragging lines on the screen. The software immediately applies a generic improvement, but then the fun really begins as you can modify all kinds of aspects using a set of sliders.

Facial feature identificationGiven a photo of a person, the software analyses the face and identifies the facial features - this process is automatic, but usually needs some slight manual tweaking, for example to make sure it exactly follows the line of the teeth - but that's just a matter of dragging lines on the screen. The software immediately applies a generic improvement, but then the fun really begins as you can modify all kinds of aspects using a set of sliders.

Want to whiten the teeth? No problem. Improve skin texture and colour? Easy. Apply fake makeup? A breeze - lipstick, mascara, bronzer, the works (no I didn't). And there's some more subtle work going on here too - for example, the software can subtly change the shape of the nose or plump up the lips - and the effect is remarkably convincing.

You might think this kind of thing only applies to those who want a modelling career, but we all use pictures of ourself, for example on social media, or in my case, in book publicity. And even a face like mine (take that as you will) can benefit from a little enhancement. I used a photo I regularly employ in publicity. I wasn't looking straight at the camera, as is often the case in portraits, and my skin wasn't having one of its best days. I may be biassed, but I'm impressed by the improvement:

In case it's not obvious, the one on the left is the 'before' and the one on the right the 'after'. By default, while running the program you get this kind of before and after shot (useful to have a big screen), which makes for easy comparison.

The changes are subtle, but comprehensive. Although the most obvious difference is skin thats less red, there are at least 20 different processes that have been automatically applied, a couple of which I've tweaked slightly. But the final outcome is a photo that, while equally good in terms of quality, simply looks a lot better. (I should have taken more of the shine off my skin, but I forgot.)

Of course we have something of a backlash on the matter of airbrushed photos of celebrities and social media selfies. But this isn't a matter of drastic change, simply doing the kind of thing a makeup artist does routinely for a TV appearance - making the best of what you've got. And if a photo is to do a job, why not?

You can pay £99.95 for the full pro version of the software, but to be honest the bells and whistles this adds are only going to interest a photographer working for a glossy magazine. Unless you handle RAW image files, the standard version does everything you might need for £29.95 at the time of writing. Clearly PortraitPro is not for everyone. But if you either take a lot of pictures of people, or, like me, need to provide publicity photos for various reasons, then it's well worth considering the investment. (There's a free trial version to give it a go.)

The software is available direct from the PortraitPro website. It's available for Windows or Mac (OSX 10.6 or later).

Facial feature identificationGiven a photo of a person, the software analyses the face and identifies the facial features - this process is automatic, but usually needs some slight manual tweaking, for example to make sure it exactly follows the line of the teeth - but that's just a matter of dragging lines on the screen. The software immediately applies a generic improvement, but then the fun really begins as you can modify all kinds of aspects using a set of sliders.

Facial feature identificationGiven a photo of a person, the software analyses the face and identifies the facial features - this process is automatic, but usually needs some slight manual tweaking, for example to make sure it exactly follows the line of the teeth - but that's just a matter of dragging lines on the screen. The software immediately applies a generic improvement, but then the fun really begins as you can modify all kinds of aspects using a set of sliders.Want to whiten the teeth? No problem. Improve skin texture and colour? Easy. Apply fake makeup? A breeze - lipstick, mascara, bronzer, the works (no I didn't). And there's some more subtle work going on here too - for example, the software can subtly change the shape of the nose or plump up the lips - and the effect is remarkably convincing.

You might think this kind of thing only applies to those who want a modelling career, but we all use pictures of ourself, for example on social media, or in my case, in book publicity. And even a face like mine (take that as you will) can benefit from a little enhancement. I used a photo I regularly employ in publicity. I wasn't looking straight at the camera, as is often the case in portraits, and my skin wasn't having one of its best days. I may be biassed, but I'm impressed by the improvement:

In case it's not obvious, the one on the left is the 'before' and the one on the right the 'after'. By default, while running the program you get this kind of before and after shot (useful to have a big screen), which makes for easy comparison.

The changes are subtle, but comprehensive. Although the most obvious difference is skin thats less red, there are at least 20 different processes that have been automatically applied, a couple of which I've tweaked slightly. But the final outcome is a photo that, while equally good in terms of quality, simply looks a lot better. (I should have taken more of the shine off my skin, but I forgot.)

Of course we have something of a backlash on the matter of airbrushed photos of celebrities and social media selfies. But this isn't a matter of drastic change, simply doing the kind of thing a makeup artist does routinely for a TV appearance - making the best of what you've got. And if a photo is to do a job, why not?

You can pay £99.95 for the full pro version of the software, but to be honest the bells and whistles this adds are only going to interest a photographer working for a glossy magazine. Unless you handle RAW image files, the standard version does everything you might need for £29.95 at the time of writing. Clearly PortraitPro is not for everyone. But if you either take a lot of pictures of people, or, like me, need to provide publicity photos for various reasons, then it's well worth considering the investment. (There's a free trial version to give it a go.)

The software is available direct from the PortraitPro website. It's available for Windows or Mac (OSX 10.6 or later).

Published on March 24, 2016 01:57

March 21, 2016

The welfare thing

We seem to be in interesting times in British politics, with Iain Duncan Smith resigning from the government over attempts to reduce the disability welfare budget. Some suggest it's more to do with causing damage to his enemies in the in/our battle over the EU - but I tend to side with those who think that IDS was genuinely trying to do something positive for welfare, and that he genuinely cares about welfare/work.

I think that in responding to this, the left wing has to be really careful about the whole business of welfare, because from something I heard at the weekend I worry that some regard welfare, and specifically in-work benefits, as a good thing in its own right, rather than a necessary evil.

I was listening to Any Questions/Any Answers on the radio, and a caller was denouncing the government's apparent wish to reduce and/or get rid of in-work benefits. I personally think that working credits was a cack-handed way to introduce negative income tax, and it would have been much better handled as a simple tweak to the income tax system, rather than a whole separate system. But it was a noble aim, as a temporary fix. What worried me is that caller dismissed the idea of the living wage, saying 'yes, but that's just the employer paying,' or words to that effect. She saw the benefits as an inherent good, rather than a patch for an inadequate reward for employment.

I'm a realist. I know we aren't going to achieve a perfect world. But surely our goal should be to have a living wage that means most people currently receiving in-work benefits can live on their earnings and not need in-work benefits? Surely the employer paying an employee sufficient to live on if they are going to do a full time job is a good thing, not something to be dismissed in favour of eternal welfare?

Of course, some businesses will whine 'we can't afford to pay people a living wage.' Well, guess what? That means they aren't running a viable business. Simple as that.

I think that in responding to this, the left wing has to be really careful about the whole business of welfare, because from something I heard at the weekend I worry that some regard welfare, and specifically in-work benefits, as a good thing in its own right, rather than a necessary evil.

I was listening to Any Questions/Any Answers on the radio, and a caller was denouncing the government's apparent wish to reduce and/or get rid of in-work benefits. I personally think that working credits was a cack-handed way to introduce negative income tax, and it would have been much better handled as a simple tweak to the income tax system, rather than a whole separate system. But it was a noble aim, as a temporary fix. What worried me is that caller dismissed the idea of the living wage, saying 'yes, but that's just the employer paying,' or words to that effect. She saw the benefits as an inherent good, rather than a patch for an inadequate reward for employment.

I'm a realist. I know we aren't going to achieve a perfect world. But surely our goal should be to have a living wage that means most people currently receiving in-work benefits can live on their earnings and not need in-work benefits? Surely the employer paying an employee sufficient to live on if they are going to do a full time job is a good thing, not something to be dismissed in favour of eternal welfare?

Of course, some businesses will whine 'we can't afford to pay people a living wage.' Well, guess what? That means they aren't running a viable business. Simple as that.

Published on March 21, 2016 02:42

March 17, 2016

How to deal with Bristol's past

Bristol is one of my favourite cities in the UK - small enough to be friendly, big enough to have all the benefits of city life. And this view has been reinforced by my two days a week as an RLF literary fellow at the university. However, it's pretty much impossible not to be aware that a lot of Bristol's money (and its better buildings) came from two sources that would now be regarded as unpalatable: the slave trade and the tobacco industry.

The reason this came to mind was reading Sanjida O'Connell's essay The Silence of the Slave, a fascinating account of her attempt to find the voice of slaves for her writing. It's an excellent article, but one aspect disturbed me. Sanjida uses as a hook for the piece an experience while eating in Pizza Express in Bristol and realising that the building was an old bank that was funded by the slave trade. She writes:

This raises two issues for me. The first is the time/responsibility argument. The idea that we can be responsible for the sins of our forebears seems totally illogical. Apart from anything, where do we stop? Should be unhappy about eating in an Italian restaurant because the Romans invaded Britain? Or should I be unhappy about being anywhere built by an Englishman because of the way Cromwell treated my Irish ancestors?

A reinforcing argument, is universality. Practically every country has practiced slavery at some point in its past. Why pick out one historical instance? Surely it is far more important to do something about countries that still allow slavery today. Not to mention cultures with intellectual slavery, where people are punished should they dare to disagree with political or religious leaders, or where, for instance, women are not allowed to drive or get an education. Slavery is still with us today, and that truly is a horror.

* If it's not your kind of book (I confess I rarely read historical fiction), I'd recommend Sanjida's non-fiction book on sugar which includes some aspects of the slave trade, Sugar: the grass that changed the world, and, simply because it's a great read, her latest, a psychological thriller called Bone by Bone.

The reason this came to mind was reading Sanjida O'Connell's essay The Silence of the Slave, a fascinating account of her attempt to find the voice of slaves for her writing. It's an excellent article, but one aspect disturbed me. Sanjida uses as a hook for the piece an experience while eating in Pizza Express in Bristol and realising that the building was an old bank that was funded by the slave trade. She writes:

By the time my daughter’s ice cream and chocolate sauce arrived, I had a prickling sensation running across my shoulder blades and I couldn’t wait to get out of that tastefully decorated restaurant. I’d realised that this former bank was founded by and had housed the accumulated wealth of the city’s merchants who, almost without exception, had been involved in the slave trade.The reason it disturbed me is not that we should simply brush the impact of slavery aside - and if you like historical fiction, I'd recommend reading Sanjida's Sugar Island, a novel that doesn't shy away from revealing the realities*. It is essential that we remember past horrors committed by human on human, whether it's slavery or the Holocaust. What I'm not totally comfortable with is the idea that we should feel guilty about, say, eating in such a building, as if somehow we, today, have a unique and terrible personal past we need to atone for.

This raises two issues for me. The first is the time/responsibility argument. The idea that we can be responsible for the sins of our forebears seems totally illogical. Apart from anything, where do we stop? Should be unhappy about eating in an Italian restaurant because the Romans invaded Britain? Or should I be unhappy about being anywhere built by an Englishman because of the way Cromwell treated my Irish ancestors?

A reinforcing argument, is universality. Practically every country has practiced slavery at some point in its past. Why pick out one historical instance? Surely it is far more important to do something about countries that still allow slavery today. Not to mention cultures with intellectual slavery, where people are punished should they dare to disagree with political or religious leaders, or where, for instance, women are not allowed to drive or get an education. Slavery is still with us today, and that truly is a horror.

* If it's not your kind of book (I confess I rarely read historical fiction), I'd recommend Sanjida's non-fiction book on sugar which includes some aspects of the slave trade, Sugar: the grass that changed the world, and, simply because it's a great read, her latest, a psychological thriller called Bone by Bone.

Published on March 17, 2016 01:58

March 16, 2016

O Rochdale, my Rochdale

Rochdale's glorious Town Hall looking a touch

Rochdale's glorious Town Hall looking a touchImpressionist last time I was thereI come originally from a town called Rochdale in the North of England. And it's in the news rather a lot - usually for all the wrong reasons.

In the recent list of UK towns and cities in the greatest economic decline... Rochdale came out the worst in the country. Admittedly, the council's chief executive said it was old data, and things are being transformed now - but from all I hear it has a long way to go. When I was young, Rochdale was still a mill town - now I don't think it knows what it is, and the town centre shows it, all too horribly.

Then there's the other difficulties. On a light note there was the Gillian Duffy incident that was a bit of nightmare for Gordon Brown's 2010 election campaign. But far darker is the alleged child abuse legacy of the late MP Cyril Smith and the troubles of current MP Simon Danczuk, who didn't exactly cover himself in glory by sending unwise tweets to a teenager. And then there was the 2012 trial, where Rochdale achieved the dubious first of having the first gang of of grooming sex offenders tried. And Rochdale's flooding over the winter was hardly ever covered by the media, but as bad as that suffered by several other better-publicised locations. Oh, and another top 10 puts Rochdale third in the country for asylum seekers for head of population - not in itself a bad thing, but not ideal, given the town's battered state and weak resources.

Thankfully, it's not all bad news. As a location it has a lot going for it (apart from the weather). When I first moved down south to work, I got off a train at South Ruislip, hunting somewhere to live. I went up on the railway bridge, and I all I could see in any direction was buildings. In Rochdale, you are rarely out of sight of the high moors, with around two thirds of the town surrounded by wild moorland. I was up in Rochdale in 2013 handing out prizes at Rochdale Sixth Form College - and their work is really inspiring. I'm sure there are other good things going on. Rochdale has certainly produced a few famous people, from John Bright the anti-corn law protester, through singers Gracie Fields, Lisa Stansfield, actor Anna Friel, presenters Bill Oddie, Andy and Liz Kershaw and the like. Not to mention being the founding home of the Co-op movement. But at the moment, on the rare occasions I go back, it feels a sad place.

Is this my fault (in part)? Am I like the people who bemoan the decline of the UK while living abroad? I hope not. I moved away to get a job - which would have happened just as much if I'd lived in leafy Tunbridge Wells as it would coming from Rochdale. I've now lived two thirds of my life away from Rochdale. And I don't suppose I would ever move back, because the rest of my family hasn't got that same connection. But it doesn't stop me being sad. I will always be from Rochdale, always a Lancastrian - and if the Northern Powerhouse is to achieve anything, I hope it's to give places like Rochdale, and their people, a chance of bringing back some pride.

Published on March 16, 2016 02:25

March 15, 2016

A true gentleman

It's a shock when someone your know dies, and never more so than someone you knew very well when younger, but haven't seen for many years, and so they are still a young person in your memory.

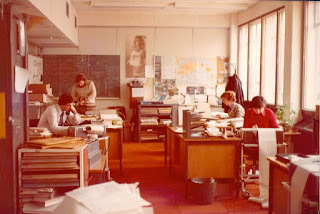

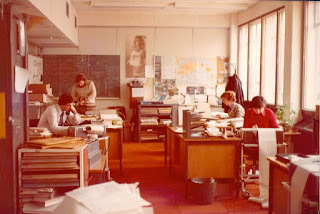

The PAM team - (L to R) John , Anthony,

The PAM team - (L to R) John , Anthony,

(Louis missing), me, VerityI have just heard of the death of Anthony Fennelly, a friend and colleague from my early years at British Airways. In tributes I have seen, Anthony frequently referred to using that old fashioned epithet 'a gentleman' - I think this is because he was, without doubt, a gentle man. Softly spoken, helpful and friendly, Anthony started at BA a little before me and was already established in the team I joined after my training in T108 Comet House, on the engineering base at Hatton Cross, near Heathrow Airport. From the start he helped me fit in and soon became a friend.

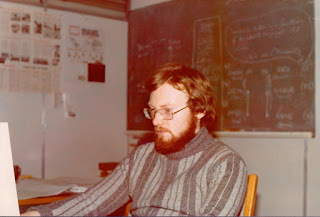

A common sight: Anthony smiling

A common sight: Anthony smiling

(with Brian Grumbridge and me)We were a small team led by John Carney (who sadly died in a boating accident a good few years ago): Anthony, Louis Hooper, Verity Riding and me, (the PAM or Programme Analysis Model team) in a fairly compact end of a longer office. Anthony might have been soft spoken, but had a wicked sense of humour, and was inordinately fond of puns, such as his long-remembered illustration of a London station using a crab shouting 'Hurrah!' (Cheering Crustacean = Charing Cross Station) and an unstinting enthusiasm for lagomorphs.

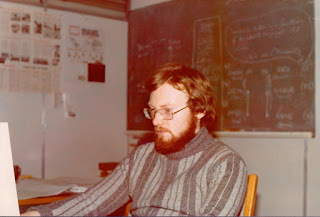

Serious concentration

Serious concentration

When we were both single we tended to socialise more (I remember being introduced to King Crimson round at Anthony's flat): inevitably with families and changes of team we lost contact to a degree, but over the 17 years I was at BA, any sighting of Anthony was always a delight.

The photos here are very much that young Anthony from my memory - circa 1978/9. The last time I saw him was at the Operational Research anniversary celebration in 2012. The world has lost a lovely man, and a great husband and father Such a shame.

The PAM team - (L to R) John , Anthony,

The PAM team - (L to R) John , Anthony, (Louis missing), me, VerityI have just heard of the death of Anthony Fennelly, a friend and colleague from my early years at British Airways. In tributes I have seen, Anthony frequently referred to using that old fashioned epithet 'a gentleman' - I think this is because he was, without doubt, a gentle man. Softly spoken, helpful and friendly, Anthony started at BA a little before me and was already established in the team I joined after my training in T108 Comet House, on the engineering base at Hatton Cross, near Heathrow Airport. From the start he helped me fit in and soon became a friend.

A common sight: Anthony smiling

A common sight: Anthony smiling(with Brian Grumbridge and me)We were a small team led by John Carney (who sadly died in a boating accident a good few years ago): Anthony, Louis Hooper, Verity Riding and me, (the PAM or Programme Analysis Model team) in a fairly compact end of a longer office. Anthony might have been soft spoken, but had a wicked sense of humour, and was inordinately fond of puns, such as his long-remembered illustration of a London station using a crab shouting 'Hurrah!' (Cheering Crustacean = Charing Cross Station) and an unstinting enthusiasm for lagomorphs.

Serious concentration

Serious concentrationWhen we were both single we tended to socialise more (I remember being introduced to King Crimson round at Anthony's flat): inevitably with families and changes of team we lost contact to a degree, but over the 17 years I was at BA, any sighting of Anthony was always a delight.

The photos here are very much that young Anthony from my memory - circa 1978/9. The last time I saw him was at the Operational Research anniversary celebration in 2012. The world has lost a lovely man, and a great husband and father Such a shame.

Published on March 15, 2016 02:37

March 14, 2016

Correlation, causality and accusations of witchcraft

A story in the news today was a classic example of the confusion of correlation and causality. Scientists are always banging on about this, and some people wonder how this apparent statistical nicety matters - yet it's the reason that over the centuries people have been accused of witchcraft.

A story in the news today was a classic example of the confusion of correlation and causality. Scientists are always banging on about this, and some people wonder how this apparent statistical nicety matters - yet it's the reason that over the centuries people have been accused of witchcraft.Correlation is when two things happen in proximity - of time, space or both. Causality is when one causes the other. Because we understand the world through patterns, when there is correlation, we tend to assume causality - but without evidence, this is a mistake. In the case of witches, an old person might curse a farmer for not giving them some milk. Two days later, one of the farmer's cattle dies. Burn the witch!

You might think that we are beyond such thinking in the UK, but unless there is data that wasn't presented in this news story, we clearly aren't (I read it in the i newspaper, but I'm sure it was elsewhere too.) There has been a large rise in the number of students accessing counselling services in universities over the last few years. Over the same period, tuition fees have pretty much trebled. There's the correlation, but as yet we've no evidence (let alone proof of causality). So what are we given?

A spokesman from mental health charity Mind said tuition fees and student loan debt were 'major contributors' to the rise in students seeking mental health help. Evidence? None given - appears to be a pure assumption. He went onto say it was 'unlikely' that the rise reflected greater openness around mental health. But even if this is the case it doesn't mean there is only one other cause - it's not either/or.An NUS spokesperson said 'The evidence is clear - the marketisation of education is having a huge impact on students' mental health' - what evidence, except correlation. Pure political witch hunting statement.A psychologist commented 'Research has shown that financial difficulties, such as being unable to pay bills, has an impact on mental health in students.' Quite probably true, but totally irrelevant. Student loan repayments don't kick in until the end of the course when the student is earning over £21,000.Let's be clear, I'd prefer it if we didn't have tuition fees, and mental health issues are very important. But by leaping from correlation to causality in this way, the story totally undermines its argument. There may be evidence of causality - but it certainly isn't presented. If the psychologist is right, it seems far more likely that the cause (over and above more reporting) is financial difficulties while a student - which has nothing to do with tuition fees. But without data, to make this kind of suggestion is an irresponsible act.

Published on March 14, 2016 02:52

March 9, 2016

Crikey! Where are my exclamation marks?

Apparently, the Department of Education has instructed moderators testing 7-year-olds' writing abilities to only consider a sentence with an exclamation mark correct if that sentence starts with 'How' or 'What' and uses 'the syntax of an exclamation.'

Apparently, the Department of Education has instructed moderators testing 7-year-olds' writing abilities to only consider a sentence with an exclamation mark correct if that sentence starts with 'How' or 'What' and uses 'the syntax of an exclamation.'This is one of those ideas that come about with the best of intentions but totally miss the mark. Most young writers do use far too many exclamation marks. Of course, there are no such things as hard and fast rules in writing, but like swearing, exclamation marks are generally much more effective if used sparingly and pointedly. So I can absolutely understand an urge to cut down on exclamation mark confetti.

However, there are two big problems here - the age and the criteria. Whether or not you approve of testing 7-year-olds (I can see a point of doing it as a benchmark), it sounds too young to pin down punctuation. Far worse, though, are those criteria.

Along with almost everyone writing since 1920, I would hardly ever use an exclamation mark in a sentence beginning 'How' or 'What'. I just don't feel the urge to write 'How do you do!' or 'What ho, Jeeves!' Checking the nearest English usage guide (Swan, Practical English Usage), there are some sensible examples for how and what, but Swan also points out that these are often formal or old fashioned, such as 'How nice!' or 'What a rude man!' And he lists various other common forms of acceptable exclamation, such as so/such sentences and negative questions ('Isn't it beautiful!')

As for 'the syntax of an exclamation'? What is that all about? Really. I have no clue what they mean. And I'm supposed to be a writer.

It's stupid!

Published on March 09, 2016 00:43

March 8, 2016

Chancellor for President

Like most of us who think having a royal family is a waste of public money and newspaper column inches, I get regular 'Yes, but what about...' retorts. Some of them are just inane, such as 'They bring in a lot of tourism.' Really? So France really has trouble getting visitors ever since they got rid of their royal family?

Like most of us who think having a royal family is a waste of public money and newspaper column inches, I get regular 'Yes, but what about...' retorts. Some of them are just inane, such as 'They bring in a lot of tourism.' Really? So France really has trouble getting visitors ever since they got rid of their royal family?Clearly this can't be about people actually seeing the royals - very few visitors, for instance, will see Prince William on the(mostly closed to the public) two days of work he manages to squeeze into a week. If there is any draw, it's about the pageantry and the royal palaces. Well, guess what? We can still change the guard and all that stuff - in fact if we really wanted to save money, we could even do it with cheap unemployed actors, rather than wasting our military's time. And all of the royal palaces could be open all year round, rather than bits of them at times the royals fancy it. Oh, and there'd be a lot more public access in the Duchy of Cornwall.

As an argument, that's a busted flush. But I confess I've struggled in the past with the 'Yes, but if you have a president you'll just end up with another bloody politician as head of state,' argument. And what's going on in the USA, entertaining though it may be, is no encouragement. But I realised today what the model should be - university chancellors. They are the equivalent of a formal head of state, leaving the actual running of the university to the professional vice chancellor - and with a few oddities, the chancellors are excellent at their jobs. So let's model the British president on a university chancellor.

I don't know, to be honest, how they end up with such good choices, but here's one suggestion for how to do it. You would be barred from office if you had ever been a politician or civil servant. Each major party could put forward one candidate, plus a single public candidate, where anyone could put themselves forward for an online vote.

As always, there's fine tuning - come on, I thought of this on the train to Bristol. But you know it makes sense...

Published on March 08, 2016 01:48

March 7, 2016

How far away is that ancient galaxy?

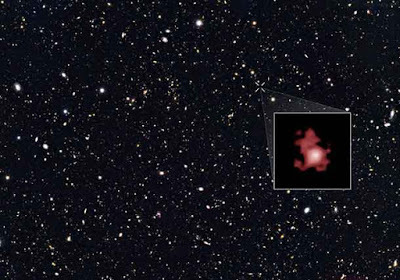

Credit: NASA, ESA and P. Oesch (Yale University) The news has been full of the remarkable discovery of galaxy GN-z11, which appears to have formed just 400 million years after the origins of the universe. Definitely 'A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.' But exactly how far? Unfortunately some of those reporting the news have been a little confused on the distance to the galaxy.

Credit: NASA, ESA and P. Oesch (Yale University) The news has been full of the remarkable discovery of galaxy GN-z11, which appears to have formed just 400 million years after the origins of the universe. Definitely 'A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away.' But exactly how far? Unfortunately some of those reporting the news have been a little confused on the distance to the galaxy.What do we actually know? We are seeing GN-z11 as it was around 400 million years after the Big Bang - so the light has taken 13.4 billion years to reach us. And it was discovered with a redshift of around z=11.1. (You can read the actual paper here.) That 'z' value represents the difference between the observed wavelength and the emitted wavelength divided by the emitted wavelength, so z=0 would mean there was no red shift at all.

Unfortunately, some of those reporting this went a step too far with headlines like this:

Here's a few more iffy remarks:'GN-z11 is a record-breaking 13.4 billion light years away...''Located a record 13.4 billion light years from Earth...''NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has discovered the most remote galaxy ever seen from Earth - 13.4 billion light years away.''A galaxy 13.4 billion light years away has been spotted by the Hubble Space Telecope.'It seems a reasonable idea. We've heard that the light has taken 13.4 billion years to reach us - so surely the galaxy is 13.4 billion light years away? Unfortunately, no - because the universe has not been sitting around doing nothing for the last 13.4 billion years. The point of that 11.1 value for z is that this galaxy is seriously red shifted, which means it is moving away from us at a heck of pace. While the light has been on its way, the universe has expanded massively, so this ancient galaxy is now far more than 13.4 billion light years away.

Here's a few more iffy remarks:'GN-z11 is a record-breaking 13.4 billion light years away...''Located a record 13.4 billion light years from Earth...''NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has discovered the most remote galaxy ever seen from Earth - 13.4 billion light years away.''A galaxy 13.4 billion light years away has been spotted by the Hubble Space Telecope.'It seems a reasonable idea. We've heard that the light has taken 13.4 billion years to reach us - so surely the galaxy is 13.4 billion light years away? Unfortunately, no - because the universe has not been sitting around doing nothing for the last 13.4 billion years. The point of that 11.1 value for z is that this galaxy is seriously red shifted, which means it is moving away from us at a heck of pace. While the light has been on its way, the universe has expanded massively, so this ancient galaxy is now far more than 13.4 billion light years away.How far away? We don't know for certain. The calculation is messy. Luckily Edward Wright of UCLA has produced a calculator that will give us a feel for just how far away the galaxy is. The bad news is that there are several factors that have to be entered into the calculator, including an assumption about the nature of the curvature of the universe, Hubble's constant, which relates the redshift to the distance, and the proportion of matter and dark energy - the more dark energy, the faster the acceleration of the expansion. (I slightly over-simplify the model, but that's a fair picture.)

Plugging in what seem to be the best accepted current values into the calculator comes up with an approximate 'comoving radial distance', the most meaningful measure to call the distance to the galaxy, of around 31.8 billion light years - rather more than 13.4. Far, far away indeed.

Published on March 07, 2016 01:48

March 1, 2016

Unweaving the rainbow of news

I've often moaned about the poor use of statistics in the news. Today it's more a case of a total absence of stats, which could have put a story into context and would have made it more informative.

I've often moaned about the poor use of statistics in the news. Today it's more a case of a total absence of stats, which could have put a story into context and would have made it more informative.In the story shown, we learn that 'everyone says it's incredible' that a mother born on Feb 29 should have a child also born on leap year day.

But if the journo could have just taken a moment to think, he or she could have put this into useful context. It certainly seems incredible if you misapply statistics and think there's a 1 in 1,461 chance of the mother being born on Feb 29, and similarly for a totally randomly occurring baby, making it a 1 in 2.13 million chance of the double. But that's just wrong because it's telling us about the chances of a randomly picked baby being in this situation, not the chances of the situation occurring this Feb 29th.

About 700,000 babies will be born in the UK this year, so with a 1 in 1,461 chance of the mother being born on Feb 29th, around 479 of this year's babies should be born to leap year day mothers. Of these, we'd expect one or two to be born on Feb 29th. Not that remarkable, then. (In practice things are a little more complex, as more babies are born at certain times, etc., but it's roughly right.)

There is always the 'unweaving the rainbow' argument aimed at Newton. Those who take this position argue that the facts get in the way of the poetry of the story. But I would argue it's possible to still find the story interesting, while being better informed by the context. Journalists would never tell us a political story without context - it's a shame (possibly because they don't know how to) that they ignore it in a statistical story.

Published on March 01, 2016 05:26