Brian Clegg's Blog, page 30

January 2, 2022

Review: Five Little Pigs - Agatha Christie *****

As someone who writes the occasional murder mystery, I am entirely in awe of this book (which I received as a Christmas present). If I'm honest, I've tended to think of Agatha Christie as someone who turned out formulaic potboilers, partly, I suspect, because I've seen them on TV rather than read most of them. I was partly swayed from this view by

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

, but the 1942 Five Little Pigs totally changed by view: it is a lesson in how to put a totally different twist on the detective story.

As someone who writes the occasional murder mystery, I am entirely in awe of this book (which I received as a Christmas present). If I'm honest, I've tended to think of Agatha Christie as someone who turned out formulaic potboilers, partly, I suspect, because I've seen them on TV rather than read most of them. I was partly swayed from this view by

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

, but the 1942 Five Little Pigs totally changed by view: it is a lesson in how to put a totally different twist on the detective story.On paper, it shouldn't work - because nothing much happens. The key events took place 16 years earlier. All Poirot is able to do is talk to a few people. There is hardly any narrative development. Yet it is a masterpiece of construction. Poirot's client's mother was convicted of killing the client's father all those years ago - he is asked to find out if it is true.

All the book consists of is an introduction, Poirot interviewing each of the five other suspects, a written statement from each suspect, and Poirot pulling it together. But in that sparse format, Christie weaves in an impressive mix of red herrings and subtle pointers to what really happened.

Don't come to find much engaging drama in this book - but if you like a cerebral murder mystery it is arguably one of the greatest ever written.

Five Little Pigs is available from Bookshop.org , Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com .

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

December 20, 2021

Review - The Christmas Murder Game ***

Around Christmas, a good murder mystery goes down well - and all the better if it's set at Christmas time. I've got mixed feelings about this one. It's an entertaining premise - various family members stuck in a country house, with a clue to solve on each of the twelve days of Christmas. The winner of each gets a key, one of which will take them to a secret room where they can claim the title deeds of the house. And the book is reasonably readable. But there are some issues.

Around Christmas, a good murder mystery goes down well - and all the better if it's set at Christmas time. I've got mixed feelings about this one. It's an entertaining premise - various family members stuck in a country house, with a clue to solve on each of the twelve days of Christmas. The winner of each gets a key, one of which will take them to a secret room where they can claim the title deeds of the house. And the book is reasonably readable. But there are some issues.The first person central character, Lily, spends far too long agonising over life, the universe and everything. In fact, she's a bit of a misery. Right at the start she is given a way to just have the house and end the whole thing, but doesn't bother for no obvious reason. Meanwhile, the storyline, which involves several deaths without anyone doing much about them, seems far-fetched to say the least. The 'clues' in the form of a sonnet a day are pretty much unguessable by the reader. And the whole motivation for the various crimes that feature seems totally out of proportion to the potential reward.

Add in a tendency to floweriness in the writing and some far-fetched similes (for example 'the sky is the cold dark blue of flames ticking a Christmas pudding' and 'the Yorkshire lanes don't help - artery-narrow, hedgerows encroaching on the road like bad cholesterol' are packed into the same short paragraph) and it can be hard work sometimes. But then, Christmas is a time when we want to turn off and don't necessary need excellence: I quite enjoyed the book despite its flaws.

Fated is available from Bookshop.org , Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com .

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

December 9, 2021

Review: Alex Verus series *****

There are broadly two types of urban fantasy. Ones where the setting is primarily the normal world, intruded on by the fantasy - think, for example, of fantasy books where conventional police officers investigate supernatural crimes - and ones where there is a parallel magical society. The latter was the case with the Harry Potter books, and is also what we find in Benedict Jacka's excellent Alex Verus books. This series, beginning with Fated, is now complete with Risen, its twelfth title, which seemed an excellent point to review it.

There are broadly two types of urban fantasy. Ones where the setting is primarily the normal world, intruded on by the fantasy - think, for example, of fantasy books where conventional police officers investigate supernatural crimes - and ones where there is a parallel magical society. The latter was the case with the Harry Potter books, and is also what we find in Benedict Jacka's excellent Alex Verus books. This series, beginning with Fated, is now complete with Risen, its twelfth title, which seemed an excellent point to review it.I was a touch suspicious about this 'new master of magical London' tagline that appears on some of the books - apart from anything, I'm fed up with urban fantasy books set in London. But Jacka gives us something genuinely original. This is a society where the small, magically endowed subset of the population is impressively self-centred. I'd go so far as to say that most of them are psychopaths. But the central character, Alex Verus is different. He is considerate of others and as a mage, in theory a more senior figure in the magical establishment, he tries to help the lesser adepts and apprentices.

Unlike many of the others with magical abilities we come across, Verus has relatively weak abilities, unable to form a shield or attack with some form of force - instead, he is a 'diviner' who can see possible futures, using them to anticipate what others will do.

Jacka manages the difficult balance in a series of this length of giving each book a satisfactory storyline that comes to an end, while maintaining a series arc across the whole thing as we see Verus rise in magical society, discover more about his past and gradually accept his own personality. At the same time, he develops a Scooby gang of weaker individuals (the parallels with Buffy are quite strong in some ways, including the way that the central character transforms) who he nurtures, and one of whom he falls in love with (though we spot this long before he does).

The final book ties things up well with some dramatic twists, especially in the way it plays with first person narrative towards the end. A powerful series that keeps up the pace without the series droop that is common with a run of this length. Recommended (reading the books in order is essential, though).

Fated is available from Bookshop.org , Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com .

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

November 22, 2021

Meta Whodunnits

As someone who writes murder mysteries (see https://www.brianclegg.net/fiction.html) I also love reading them and watching them on TV, but perhaps because of spending time thinking about book plots, I've noticed that sometimes the relationship of the reader/viewer to the medium makes it possible to get clues that the characters can never access.

As someone who writes murder mysteries (see https://www.brianclegg.net/fiction.html) I also love reading them and watching them on TV, but perhaps because of spending time thinking about book plots, I've noticed that sometimes the relationship of the reader/viewer to the medium makes it possible to get clues that the characters can never access.In TV mysteries, for example, there is always the 'well known actor' syndrome. This says that actors who are famous are likely to have an important part in the proceedings, as they wouldn't be hired just to do a bit part. Then there's the weird placement effect. What we are shown on TV or read about in a book is carefully controlled. So although we have to deal with red herrings, the fact that something is mentioned that doesn't need to be alerts us to its possible significance.

However, I've just come across an even more meta* example of a piece of information providing the solution to a whodunnit where not only could the characters not access it, but even the information itself was specifically intended not to give anything away.

At the weekend I watched an Agatha Christie documentary on Netflix which used the hook of ten of her books to tell the story of her life and work. The second of these was the 1926 gem The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. Rather oddly, I had a copy of the book, but I had never read it (the Penguin copy, illustrated here, is a 1949 edition I inherited from my grandmother). If I'm honest, I've only read about three Christie books as I've always given more weight to the likes of Margery Allingham and Ruth Rendell, but the documentary inspired me to read this book (and a few others of Christie's are now on my reading list).

I was pleasantly surprised - although written in the 1920s it's surprisingly unstuffy and although the writing style is fairly basic, entertainingly plotted. Yet, thanks to the documentary's attempts to keep it secret, I suspected strongly who did it all along.

Here, then, is the meta bit. What every said in the documentary was that the book had an amazing plot twist - that all the evidence was there, but the ending was extremely surprising. And that, for me, was what gave the game away. I admit there are probably more, but I can only think of three truly remarkable plot twists in a whodunnit. Two of these, I knew were used in other Christie works (one book/film and the other a play). So it seemed very likely that the third was the case with Roger Ackroyd - and this proved to be the case.

I'm not going to give it away - and ask you not to do so in the comments. If you don't know the book and want to see if you can make the same correct deduction I did, then email me at brian@brianclegg.net and I will be happy to confirm if you've guessed right.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is available from Bookshop, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

* The term 'meta' here and in the title of this post is not in away connected with Facebook's appropriation of a commonly used word - which arguably they should not have been allowed to do.

November 12, 2021

Mirror, mirror

A little while ago I had the pleasure of giving a talk at the Royal Institution in London - arguably the greatest location for science communication in the UK.

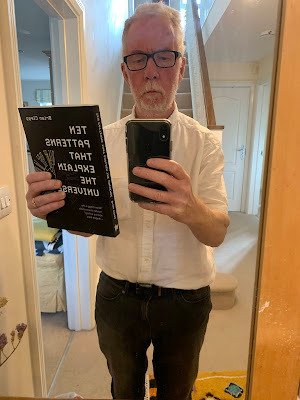

A little while ago I had the pleasure of giving a talk at the Royal Institution in London - arguably the greatest location for science communication in the UK.At one point in the talk, I put this photograph on the screen, which for some reason caused some amusement in the audience. But the photo was illustrating a serious point: the odd nature of mirror reflections.

I remember back at school being puzzled by a challenge from one of our teachers - why does a mirror swap left and right, but not top and bottom? Clearly there's nothing special about the mirror itself in that direction - if there were, rotating the mirror would change the image.

The most immediately obvious 'special' thing about the horizontal direction is that the observer has two eyes oriented in that direction - but it's not as if things change if you close one eye.

In reality, the distinction is much more interesting - we fool ourselves into thinking that the image behind the mirror is what's on our side of the glass with left and right swapped. But that's not really what's happening at all - something that is illustrated when you have a closer look at that photograph.

In it, I'm holding a copy of my book Ten Patterns that Explain the Universe (which is what the Royal Institution talk was based on). You can see the spine of the book in the image, on the side nearest the phone that's taking the picture. Now put yourself in the viewpoint of the mirror me. Holding a book like that, he is looking at the front of the book, because the spine is on his left. But I was looking at the back of my book, not its front.

What the mirror does is not swap left and right, but turn reality inside out like a rubber jelly mould, turning the back of my book into the front of the mirror book. In this process, by doing that same thing to, say, my left hand it makes it look as if it is the mirror reflection's right hand. But it's not - it's a back-to-front inverted left hand.

Welcome to the world of the looking glass.

September 30, 2021

A science book like no other

I've had a bit of a flurry of publication, mostly due to dates shifting thanks to Covid, resulting in three books being published in September. Two of these were

Ten Days in Physics that Shook the World

and

Ten Patterns that Explain the Universe

(in an attempt to corner the market in books with 'ten' in the title), but the most unusual one by far was How it All Works, written with Adam Dant.

I've had a bit of a flurry of publication, mostly due to dates shifting thanks to Covid, resulting in three books being published in September. Two of these were

Ten Days in Physics that Shook the World

and

Ten Patterns that Explain the Universe

(in an attempt to corner the market in books with 'ten' in the title), but the most unusual one by far was How it All Works, written with Adam Dant.In fact, 'written with Adam Dant' is a huge understatement - this is very much Adam's book. He is a remarkable artist who produces wonderfully detailed crowd scene drawings. All I did was suggest some scientific principles and phenomena to go in the illustrations, and added a few words on each. The result is a sort of cross between Where's Wally and a popular science book. You really don't have to care much about the science to enjoy the remarkable illustrations.

Rather than do what appears to be blowing my own trumpet (though my enthusiasm is all for the drawings), take a look at this review by Jill Bennett - although it's a children's book review, as she says 'The potential audience for this unusual book is wide – from KS2 through to adult and it’s most definitely one to add to a family collection as well as those of primary and secondary schools.'

How it All Works is available from Bookshop, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

Here's just one of the spreads - though of course there is far more detail in the book:

September 6, 2021

Percentage of what?

Every now and then a use of numbers pops up on the news that mildly irritates me. One of the worst thing the news media often do is to use a percentage without giving absolute figures to put that percentage into context.

Every now and then a use of numbers pops up on the news that mildly irritates me. One of the worst thing the news media often do is to use a percentage without giving absolute figures to put that percentage into context.For example, imagine that we hear that the murder rate in a city has gone up by 100% compared with last year. Shock, horror, sack the police. But if it happens that the murder rate last year was 1 victim, that 100% increase is 1 extra person. Not exactly a massive change and highly unlikely to have any statistical significance.

The latest version of this problem has been repeated over and over. We are told that unless the triple lock on pensions is suspended, the state pension in the UK could go up by 8% next year. A vast increase. But again, without the context it's impossible to tell what 8% means. As it happens the UK has an unusually low state pension for a European country. There current maximum is £718.40 (confusingly, this is over four weeks but isn't that far off the monthly amount).

So an 8% increase would amount to an extra £57 per monthish. I'm not saying whether or not this amount is large - that's up to you to decide. But to me, that number feels very different to the apparent largesse an 8% increase. Despite this I have never seen/heard that figure on the news. I'm sure it will have occasionally been mentioned, but the fact that it rarely is amounts to misleading reporting.

August 25, 2021

How to Stop Fascism - Review

The author, Paul Mason, always came across as a thoughtful presenter on the TV, but released from the constraints applied to broadcast news, his unashamed Marxist viewpoint shines through in this history and analysis of the threat of fascism.

The author, Paul Mason, always came across as a thoughtful presenter on the TV, but released from the constraints applied to broadcast news, his unashamed Marxist viewpoint shines through in this history and analysis of the threat of fascism.I found the historical aspects really interesting - we did the Second World War as part of history when I was at school, but there was very limited material on what drove the rise of Fascism and how it operated. I also found Mason's expectation of a second major rise of Fascism and analysis of what to do about it interesting, but in a different way - here it was more an opportunity to see how an intelligent person's thinking can be painted into a corner by his ideology.

For example, Mason spends a considerable amount of time exploring why the left failed to stop the rise of fascism in Italy and Germany - but doesn't touch on the more useful potential of why fascism failed to take off in the UK, which would be a far better source of lessons - one probably being the lack of Marxism in mainstream UK politics. Similarly, Mason links the right wing with violent language on social media leading to fascist action, yet this does not fit with the reality that you are much more likely to find hateful language on social media from the left aimed at the right than vice versa. The left tell us they hate Tories, the right that they disagree with Labour. And Mason rightly berates the far right for its antisemitism, conveniently forgetting that the left has had more problems that the right with antisemitism of late.

Occasionally I found Mason's views distinctly amusing. He tells us 'The ideas of these self-styled "philosophers" of the far right are not simply grotesque: they would not last five minutes if subjected to the rigours of logic and analysis in an actual philosophy department. That's why they communicate in obscure, long-winded and unintelligible prose. However, they are persuasive.' Leaving aside how anything unintelligible can be persuasive, no doubt what he says about right wing extremists is true - but has he ever read the obscure, long-winded prose produced by many academic philosophers? It's hardly a discipline that specialises in a clear, comprehensible writing style.

Another hilarious lack of understanding came when Mason says 'At this stage Thiel, despairing of a political solution, urged libertarians to create communities of survival not resistance; this is the rationale for Silicon Valley's obsession with building undersea cities and space travel.' No, it's because they're science fiction fans.

One final quote that produced a raised eyebrow. Mason tells us 'Large numbers of people experienced the years after 2008 not just as economic dislocation but as a crisis of identity. They asked: if I am no longer a consumer, or an atomized individual in a competitive marketplace, defined by the brands I wear, the car I own and the credit card in my wallet, who am I?' It does make you wonder if Mason has ever spoken to a real person outside academia. I can honestly say I have never met anyone who has asked this.

Underlying the issues with this book is a problem I see all the time in undergraduate essays - stating 'A therefore B' without presenting any evidence that A causes B. For example, he repeatedly over-simplifies developments such as Brexit, linking them to Trump in the US and racism without having good justification for this. Sometimes this results in statements which it's hard to link to reality such as 'Tory leaders openly celebrate Britain's history as a slave power.' Like those undergraduates he can be quite poor about defining terms before he uses them. For example, he refers to the 'working class' all the way through the book, but it's only about three-quarters of the way through that he defines what it means in a modern world, where the original concept is a very poor fit to the reality.

All in all an interesting book that is thought provoking, but it would have been better written by someone who doesn't still believe that Marxism has the answer to everything.

How to Stop Fascism is available from Bookshop.org , Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com .

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

August 18, 2021

Superheroes are not science fiction

Time for a short rant.

Time for a short rant. I occasionally peruse Apple's News app, which puts stories under topic headings. Recently one such topic was 'Science Fiction' - and it included something about a new Marvel superhero film.

In practice, the majority of films that are labelled science fiction are really sci-fi - an approximation to the real thing with very little attention to the science, or for that matter to decent fiction. For that matter, I loved the first Star Wars - but it was a fairy tale with SF trappings, not the real thing. However, the majority of superhero movies are not even bad science fiction.

While Iron Man and Batman, for example, just about makes into sci-fi (though in practice they break the laws of physics with painful regularity), the vast majority of superheroes are out-and-out fantasy characters. Their abilities are nothing more or less than magical. There is no possible real-world explanation for them.

Again, this isn't a criticism per se. I enjoy a good fantasy story (though if SF movies are sci-fi, film fantasy is usually fant-fi, were there such a term).

But we shouldn't pretend superheroes are something they're not. Their stories are fantasies.

Rant over.

July 28, 2021

The Issue at Hand - Review

This is one for the real SF nerds. It's a collection of articles, framed around reviews but giving more opinion on what makes a good science fiction story than would be common in a review, written by James Blish in the late 50s and early 60s. Fairly obscure stuff, admittedly - I've only heard of about 10 per cent of the stories and half the authors mentioned - but it is still interesting both from the insights Blish (writing as William Atheling Jr.) gives and from the sheer vitriol he pours on stories he doesn't like, even from revered names such as Asimov and Bradbury.

This is one for the real SF nerds. It's a collection of articles, framed around reviews but giving more opinion on what makes a good science fiction story than would be common in a review, written by James Blish in the late 50s and early 60s. Fairly obscure stuff, admittedly - I've only heard of about 10 per cent of the stories and half the authors mentioned - but it is still interesting both from the insights Blish (writing as William Atheling Jr.) gives and from the sheer vitriol he pours on stories he doesn't like, even from revered names such as Asimov and Bradbury.Part of the usefulness to would-be writers of science fiction is that Blish underlines some of the pitfalls they face, whether they be basic writing errors (he tears into a couple of newish authors for the wild variety of alternatives to 'said' they use in reporting dialogue, a classic beginner's mistake) or problems that are specific to the SF genre. The only one of Blish's complaints I would fundamentally disagree with is that he insists that it is essential to describe characters, where often I find the descriptions that were common in the period he was writing entirely unnecessary.

I was quite surprised initially when Blish lays into Bradbury - but reading further it's clear that he very much admired Bradbury's writing talent. What he complains about, rather, is when Bradbury strayed from the natural home of his writing, fantasy, into science fiction, where his total ignorance or lack of interest in scientific matters makes the whole enterprise uncomfortable reading. I've always been mildly horrified that practically the only science fiction book from a supposed SF writer that the literary establishment were capable of celebrating was Fahrenheit 451 - it may be closer to SF than much of Bradbury's so-called science fiction stories, but it is still painfully flawed (and not just because, as I discovered by trying it as a youth, paper doesn't spontaneously ignite at 451 degrees Fahrenheit).

That acerbic side of Blish's comments reminds me of how much fun negative reviews can be to read. You hardly ever see vicious reviews anymore, and that's a real shame. (In fact, I was once asked by a magazine to make a review more supportive because they didn't like to run negative reviews.) It makes me feel like I ought to write more. Having said that I have been quite pleased with a couple of mine - one on the truly dire Murder in the Snow by Gladys Mitchell and the other about a colouring book by an otherwise respected author who I won't name here, but who rather embarrassingly (for him) messaged me to complain about it. It's a bit like the way we don't get enough scientific papers with negative results - if all the reviews you see are glowing, the whole process lacks context and value.

The Issue at Hand is very much a specialist title. It is only going to appeal to real devotees of the genre. But I'll be buying the sequel very soon. The book is obviously long out of print, but available on Kindle thanks to the wonderful Gollanz SF Gateway reprints from Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.