Brian Clegg's Blog, page 28

June 20, 2022

Review: The 13th Witch (The King's Watch series) - Mark Hayden ***(*)

Of all the flavours of fantasy novels, I only really enjoy those set in the real world (often described as urban fantasy, although some, as is the case here, are mostly rural) - whether it's the intricate cleverness of something like Gene Wolfe's Castleview, or when it's mixed with the police procedural, as in Ben Aaronovich's Rivers of London, Sarah Painter's

Crow Investigations

or Paul Cornell's

Shadow Police

. That meant I was delighted to discover Mark Hayden's King's Watch series. In many ways it's great, though it has proved to be something of a curate's egg.

Of all the flavours of fantasy novels, I only really enjoy those set in the real world (often described as urban fantasy, although some, as is the case here, are mostly rural) - whether it's the intricate cleverness of something like Gene Wolfe's Castleview, or when it's mixed with the police procedural, as in Ben Aaronovich's Rivers of London, Sarah Painter's

Crow Investigations

or Paul Cornell's

Shadow Police

. That meant I was delighted to discover Mark Hayden's King's Watch series. In many ways it's great, though it has proved to be something of a curate's egg.The good news is that Hayden does some things brilliantly. I love the idea of rather than a police tie-in, it's a quasi-military one linked to the Tower of London, with a group originally set up by King James I (the aforementioned King's Watch, headed by a Peculier Constable). Hayden's magickal (sic) world and its political complications are beautifully imagined - whether it's the interplay between various human factions (for obscure historical reasons, for example, the North West doesn't recognise the authority of the King's Watch), or a very rich mix of different races from the near-human to demi-gods. Hayden is also very good at the action scenes - they really carry the reader along with page-turning vigour.

In The 13th Witch, the central character Conrad Clarke, a former RAF helicopter pilot, is introduced to a hidden magickal reality. At the time of writing there are 10 books in the series, with presumably 13 in total as each title reduces the number by one. There's an element of humour that's quite strong in the first book, though this tends to disappear as you move through the series.

So far, so good. But there are a couple of issues. The smallest one is that sometimes the situation Hayden imagines gets a bit beyond his ability to describe it, particularly in later parts of the series where he describes shifting between different planes of reality, some of which involved distorted flow of time. (Never as confusing as the movie Tenet, though.) There is also rather too much domestic background - we spend a lot of time on Clarke's relationships (and cricket playing) that really doesn't take the plot anywhere. Apart from his irritating fiancé, he has a series of attractive female work companions, who all seem to be about half his age, which is a bit creepy. But the thing that really irritated me was the way that you get the literary equivalent of in-app purchases.

As is not uncommon with big series, there are some spin-off novellas. I have no problem with these to optionally fill in back story or generally go off on a tangent, provided the main line of novels doesn't refer to them. The issue hear is that Hayden will mention something significant to the plot... then say 'which you can read about in Novella X, so we won't talk about it here' (or words to that effect). I found that so infuriating that a couple of times I nearly gave up on the series part way through a book. Each time (so far) I felt like that, I was then roped back in by a clever bit of suspense and intrigue. But I really didn't like this approach.

If these are your kind of books, I heartily recommend giving them a try - but they do come with that warning.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

The 13th Witch is available from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

June 10, 2022

The incredible shrinking dilemma

Image from Unsplash by Todd Pham I was very impressed with the first series of Amazon's show The Boys - the idea that superheroes would be used for commercial gain is such an obvious fit with America's culture. I wasn't thrilled by the level of violence and gore, but still enjoyed that first series, tolerated the second season and gave up pretty quickly as a result of the even higher level of ickiness of the newly released episodes. But before I did stop, I witnessed a character who could become tiny being carried in a bag of (ahem) white powder.

Image from Unsplash by Todd Pham I was very impressed with the first series of Amazon's show The Boys - the idea that superheroes would be used for commercial gain is such an obvious fit with America's culture. I wasn't thrilled by the level of violence and gore, but still enjoyed that first series, tolerated the second season and gave up pretty quickly as a result of the even higher level of ickiness of the newly released episodes. But before I did stop, I witnessed a character who could become tiny being carried in a bag of (ahem) white powder.Humans with the ability to shrink have been a common feature of sci-fi and superhero fantasies for ages. (I say sci-fi rather than science fiction, because of the dilemma I'm about address.) We've had The Incredible Shrinking Man (probably the best of the bunch), Fantastic Voyage, Honey I Shrunk the Whatever, Ant Man and more. But while I accept that SF has to be flexible about the science, in the tradition of Larry Niven's 1969 essay Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex, I feel we ought to at least consider the problems that arise from human shrinkage.

There seem to be two possibilities open to a would-be human miniaturiser. Either the reduced-size human temporarily misplaces the vast majority of their atoms, or they undergo some sort of process whereby the amount of empty space in atoms is reduced, so they still contain all the matter that they had previously, but in a compacted form.

Neither is particularly practical, but science fiction doesn't have to worry about this - faster than light travel is no picnic in the real world. But of the two possibilities, the atom compaction seems the more likely method because it's a far simpler concept. And I suspect for most sci-fi examples this is what the writers have in mind. However, there's a big problem for that image I conjured above of the tiny person being carried by someone in a plastic bag. Compacting would not reduce mass. The tiny person would have the same mass (and weight) as they always had, rather in the same way that a neutron star or a black hole retains its mass in a much smaller form.

This doesn't just make carrying the miniature being in the way usually demonstrated impossible. It would mean that their tiny feet exerted far more pressure than was normally the case. Pressure depends on surface area. Say the person reduced in height from 170cm to 5cm. That's a linear reduction of 34x, so the surface area reduction would be 1,156 times - and as the pressure produced by a person is simply a function of weight over surface area, that means the pressure exerted by the feet would go up by a factor of 1,156. It's not uncommon in shrinking movies for characters to be chased through grass much higher than their head by insects or spiders. But with so much more pressure on the feet, the collapsed individual would simply disappear deep into the soil.

If we think, then, of what miniature characters get up to, it's probably better to go for a corresponding reduction in mass. Mass decreases with volume - so the cube of the linear reduction. My 34x shrunken person would reduce from, say, 170kg to less than 5 grams. That's light - think about the weight of a sheet of A4 paper, a 20p piece or a US nickel. Easily carried. No pressure problems. But there are two issues.

One is just making it happen. As I mentioned above, it's relatively easy to imagine there could be some mechanism to shrink every atom, even if there isn't a genuine physical means to do it. But what we have to do here is remove 39,303 out of every 39,304 atoms in the body, nice and evenly. We then have to store them somewhere - imagine a big bag of gloppy atoms under the bed, perhaps. And we have to reinsert them when required, all in the right places, or we'd end up with something like the disastrous transporter scene in Galaxy Quest.

But even if the practicalities could be overcome there is a significant issue for our mini-people. They will be left with 0.0025 per cent of the cells in their brain. A human brain weighs about 1,350 grams on average. The typical shrunken brain would weigh 0.034 grams. Compare this with, say, a hamster's brain at 1.4 grams. Of course, weight isn't everything. Something human brains have an awful lot of is neurons, with somewhere around 16 billion in the cerebral cortex. The tiny person would be left with about 400,000. That still sounds a lot. But bear in mind a mouse has about 13 million.

Although there is no perfect measure of brain size/neuronal count that corresponds to intelligence, there can be little doubt that a human miniaturised by atom-loss would also be significantly less intelligent than a mouse or hamster. So the chances of shrinking down and saving the world are pretty slight.

Am I breaking a butterfly on the wheel? Quite possibly. But it's fun, isn't it?

May 23, 2022

The green flight gap

Photo by Etienne Jong on UnsplashThe BBC has just spent a week attempting to encourage a more green way of life - a worthwhile aim, even if it often resulted in distinctly uninspiring advice such as 'Use a reusable coffee cup.' However, on a couple of programmes I heard a suggestion that struck me as simultaneously both sensible and stupid in its limitations.

Photo by Etienne Jong on UnsplashThe BBC has just spent a week attempting to encourage a more green way of life - a worthwhile aim, even if it often resulted in distinctly uninspiring advice such as 'Use a reusable coffee cup.' However, on a couple of programmes I heard a suggestion that struck me as simultaneously both sensible and stupid in its limitations.We were told to reduce shorthaul flights. I think the logic behind this is that it's easy to use a more environmentally friendly option like rail for relatively short journeys. And I certainly would both advise people to consider taking the trains and ask governments if they couldn't do something about the ridiculous situation that it's often much cheaper to fly than travel by rail. However, the flying elephant in the room (is that a mixed metaphor, or just Dumbo?) is that longhaul flights have a far bigger negative environmental impact than shorthaul. So why weren't we told to reduce them as well?

I suspect there is an element of self-preservation amongst media types, who may well fly longhaul a lot more than ordinary people do. But if we are serious about climate change, we need to steeply reduce longhaul flying. And, of course, cut out private jet use - but that's not really the point here.

Incidentally, don't give me that guff about offsetting. Flying does the damage now. Planting a tree will reap benefits in future years when it's too late. Do plant trees, but don't think they offer you a get-out clause for flying all over the place.

We need to seriously ask ourselves whether each flight is necessary. Of course there are circumstances when flying is important. To meet up with distant family, for example. But is flying for tourism ever necessary? Do academics need to fly half way across the world to conferences? Do business people need to meet in person now the pandemic has shown how possible it is to do business remotely?

At the very least, if you or your organisation espouse green values (and especially if you tell other people that you do), perhaps it's time you looked again at your flying habits.

This has been a Green Heretic production.

May 15, 2022

How long is a piece of podcast?

Image by Mateo Abrahan from UnsplashListening to podcasts has transformed walking for exercise - and has been a revelation after the rigidity of traditional radio show formatting that requires a programme to be, say, 30 minutes long, no more, no less. However, a couple of podcasts I listened to this morning have demonstrated how things can go wrong at the boundaries.

Image by Mateo Abrahan from UnsplashListening to podcasts has transformed walking for exercise - and has been a revelation after the rigidity of traditional radio show formatting that requires a programme to be, say, 30 minutes long, no more, no less. However, a couple of podcasts I listened to this morning have demonstrated how things can go wrong at the boundaries.The (2022) podcasts in question were the 14 May episode of More or Less: Behind the Stats, lasting 9 minutes, and the 6 May episode of Kermode & Mayo's Take, which runs to 1 hour 59 minutes.

These are clearly extremes - I think it's fair to say that most podcasts are in the 30-50 minutes range. But each illustrates a point.

Let's take Tim Harford's More or Less first. This one demonstrates the danger of making a podcast that is just a radio programme repackaged. It is part of a series that is broadcast weekly on the BBC's World Service and has a rigid 9 minute slot. If it had been a real podcast, it would have run for about 15 minutes, I'd suggest. But, dealing with a relative complex single issue, Harford, who is usually a laid-back presenter, was forced to rattle through at a slightly unnerving rate. The content was fine, but the need to fit to a broadcast slot made it less than perfect listening.

By contrast, Kermode and Mayo's Take, which is a new podcast based on an earlier BBC radio show by the pair, shows that the freedom of the podcast format can be taken too far. I don't mind that nearly two hours is too long to fit with my typically 40-45 minute walk. I'm very happy to split the listening across several walks. But it felt like what we were getting was an hour's content that the presenters were allowed to run away with and extend unnecessarily. There was simply far too much wibbling with negligible information content. What this one required was a good edit.

The lessons from this listening experience seems to be twofold. We really should do away with linear broadcasting of this kind of programme and just have them as podcasts. They are better in a flexible slot than as time-constrained radio shows. But with great freedom comes great responsibility. Just because a podcast can be whatever length you like, it is still important to edit the content so it works well. I will continue to listen to Kermode and Mayo as I'm interested in film and value their opinions - but it would have been so much better if it had been tightened up.

Podcasting is still a relatively new medium and that will mean mistakes along the way. But if we learn from them, it will continue to go from strength to strength.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

May 12, 2022

Archive Special: C. P. Snow alive and well at the BBC

This is an update of a post from 2013, which still seems very relevant today:

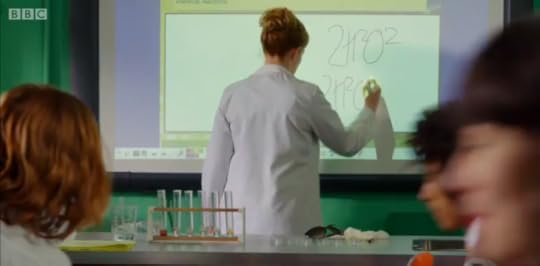

I was watching the BBC school soap Waterloo Road* the other day, and ended up rolling all over the floor moaning. Because we saw a 'science teacher' making one of the most basic possible errors. Would they have allowed an English teacher to write on a board that Hamlet was written by T. S. Eliot? Or a geography teacher to note down the capital of France as Belgium? I would hope not. Yet this is a comparable error. Take a look at this little snap.

What is she doing? It seems she has invented a new kind of hydrogen peroxide that is made up of H-squared and O-squared. I have no idea what a squared atom is, and I wait with interest to see the BBC's drama department explaining all about these new particles. At the very least, I would expect a squared atom would enable us to perform cold fusion.

In the meanwhile I just don't understand what kind of editing process at the BBC can allow H2O2 to be written as H2O2. Similarly, in another episode the chlorine molecule, Cl2, was described as C12 (C twelve) – someone had misread the L as a number 1. I can only assume every single person involved in producing this programme didn't even manage to get a science GCSE. And that says something very sad about the whole TV drama world.

Arguably these are visual reminders of C. P. Snow's 1959 'two cultures' lecture, where he accused those with a humanities background, who ‘by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated’, of looking down on the illiteracy of scientists, while simultaneously being proud of their scientific ignorance. Snow likened their inability to respond to a question about the Second Law of Thermodynamics as being the scientific equivalent of answering ‘Have you read a work of Shakespeare’s?’ in the negative.

Some argue that Snow's viewpoint is now outdated - but a steady stream of examples like the Waterloo Road failure seem to show otherwise.

* Due to be relaunched in 2022

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

May 9, 2022

Review - Nasty, Brutish and Short - Scott Hershovitz ****

Scott Hershovitz is a little harsh in applying Hobbes’ aphorism calling human life ‘nasty, brutish and short’ to children, but his idea of using children’s musings as a starting point for exploring some of the big philosophical ideas with an adult audience is little short of genius.

Scott Hershovitz is a little harsh in applying Hobbes’ aphorism calling human life ‘nasty, brutish and short’ to children, but his idea of using children’s musings as a starting point for exploring some of the big philosophical ideas with an adult audience is little short of genius.Hershovitz points out that until about the age of nine, children are naturally philosophically minded, as demonstrated by their perpetual asking of the question ‘Why?’ Science communicators find a similar effect with science - pretty well all children are fascinated by science until they are 11 or 12 (I’m sure there’s a research paper in there for why one interest dies before the other). Not only does Hershovitz encourage this exercise in thinking by turning the questions back on his children, but he also stimulates readers to think about these issues themselves. As he points out, you might not always agree with him (I certainly didn’t), but it’s a valuable exercise to think through these big ideas – and your personal prejudices – to discover more about reality and yourself.

Hershovitz’s speciality is philosophy of law (I didn’t even realise this was a thing, though when you think about the nature of law and justice, it’s an obvious topic), and law-like questions are well covered, from rights and revenge to punishment and authority. I was a bit disappointed when he talked about rights that, although he acknowledged that rights are twinned with responsibilities, he didn’t explore the idea that it’s better to think in terms of those responsibilities (which are outward looking) rather than rights, which are inward looking.

It’s almost inevitable that practically every reader will find some of Hershovitz’s views questionable. While I, for example, had little problem with his approach to swearing, others might be unhappy to find their children as foul-mouthed as Hershovitz’s are. Similarly, while Hershovitz’s ideas on God may be pretty much the norm in Europe, I would imagine a lot of Americans would struggle with them. (It may be to keep things simple, but I found his attitude to the Bible, say, was strangely flawed, in that he seemed to either assume the Bible had to be the truth in describing, say, the vengeful God of the Old Testament, or the whole thing was imaginary, rather than allowing for a circumstance where parts of this complex collection of ancient books could be folk tales while other parts could be more significant.)

I’ve leapt ahead a bit there in getting on to religion. Hershovitz gives us sections on ‘making sense of ourselves’, including gender and sports, race and responsibility , and on ‘making sense of the world’ which includes big topics such as knowledge, truth and the mind as well as the fun subject of infinity, which ties in well to both science (for example, the size of the universe) and maths. While I wouldn’t go as far as Hershovitz in suggesting science and maths are sub-disciplines of philosophy, I far prefer his approach to that of some well-known scientists who pompously and entirely inaccurately have declared that philosophy is no longer required as science has made it redundant. Inevitably, we also encounter the now very familiar trolley problem: though we get some of the less visited twists on the concept, I’ve seen this handled better. Hershovitz doesn’t really deal with the impossibility of being totally detached from real world concerns, such as the unlikeliness that pushing someone off a bridge could be guaranteed to stop a runaway tram.

Hershovitz is generally very good at pulling apart our assumptions, but his own US-centric cultural prejudices shine through particularly on gender and race, where he seems incapable of questioning the typical academic left wing liberal view. (This is particularly noticeable in his coverage of trans-athletes where the reality of sport has already changed significantly since the book was written). Interestingly, this is a point he makes himself later when talking about the echo chambers of both right and left wing figures, but seems to miss his own prejudices. For example, most academics fail to recognise their hypocrisy in recognising the importance of reducing climate change but still fly all over the world to conferences. If we are going to be picky, it’s also amusing that he applies the ‘invisible Gardener’ logic to God, but not to the equally applicable topic of the simulation hypothesis.

Overall, this book employs a brilliant concept, though I wish he hadn’t used his own kids as the only examples of children and philosophy, as it can read like the boasting of one of those parents who bores you rigid by telling you all the clever things his precocious children have said. Even so, it's a great way to bring philosophy, a topic all of us should know more about, to a wider audience.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

Nasty, Brutish and Short is available from Bookshop.org , Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

April 28, 2022

I don't want to be entitled

Image by Maxim Mox from UnsplashThere are many things that are a bit irritating about the internet (though none that outweigh its usefulness). But the one that arguably gets up my nose the most is when you fill in an online form and it insists that you enter your title. I don't want a title. If you are writing to me, address it to Brian Clegg. I'm happy for anyone to call me Brian (or Cleggy if you must). But more to the point, why on earth should I have to provide a title to, say, buy a bunch of flowers?

Image by Maxim Mox from UnsplashThere are many things that are a bit irritating about the internet (though none that outweigh its usefulness). But the one that arguably gets up my nose the most is when you fill in an online form and it insists that you enter your title. I don't want a title. If you are writing to me, address it to Brian Clegg. I'm happy for anyone to call me Brian (or Cleggy if you must). But more to the point, why on earth should I have to provide a title to, say, buy a bunch of flowers?One of the reasons I really dislike titles is the way the media, particularly TV for the masses, make obsequious use of some titles. It really puts me in cringe mode when a grown adult refers to someone else as 'Doctor Phil' or 'Doctor Anita'. This reversion to childhood doesn't apply if you have a different title though. It's never 'Mister Brian.' (Of course someone called Ed* may be thankful for this.)

For that matter, I have two Master of Arts degrees, but no one seems to feel the urge to call me Master - though with a Dr Who hat on, I could definitely warm to being the Master.

That's academic titles, of course, and on top of this there is the nightmare creepiness of aristocratic titles (especially when you're a royal and have a string of these as long as your arm). Admittedly, someone I know in the literary world did find these things quite useful. When checking into a hotel in America, he would tell them that he was Sir X Y. (Name omitted to protect the guilty.) And he got extra-special treatment because of it. Which illustrates the absurdity of the whole thing.

I know some people love their titles. They even put them on book covers. And for them, I would be happy to leave the option on internet forms so they can show how entitled they are. But please, for the rest of us, make it optional.

* One for the elderly

April 23, 2022

Beyond Words - Science and Fiction - does science fiction have to be scientific?

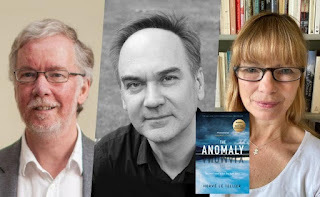

I'm a huge fan of science fiction and regularly review SF books on my popularscience.co.uk blog. It seems a truism that science fiction should involve science and/or technology - but is it an essential? This is one the topics that is likely to be discussed when I meet up for an on-stage chat with bestselling French author Hervé Le Tellier, chaired by the translator of his remarkable novel Anomaly, Adriana Hunter.

I'm a huge fan of science fiction and regularly review SF books on my popularscience.co.uk blog. It seems a truism that science fiction should involve science and/or technology - but is it an essential? This is one the topics that is likely to be discussed when I meet up for an on-stage chat with bestselling French author Hervé Le Tellier, chaired by the translator of his remarkable novel Anomaly, Adriana Hunter.If you are in London on 22 May 2022 and fancy coming along, the event, part of the Beyond Words Festival, is on at the Institut Français at 5pm. Tickets are available here.

What makes a book SF is always a subject of dispute, but for me it should reflect the human consequences of some kind science or technology. Sometimes this is straightforward - taking in the impact of, say, artificial intelligence or spaceflight. But science fiction also has certain standard concepts, such as faster than light travel or time travel that are not possible with current technology and may never be.

On the whole, the distinction between SF and fantasy in such circumstances is that science should not totally exclude the possibility of what's happening. There are physical mechanisms that could, in principle, get around the light speed limit, or the inability to travel through time. But what should we think when the 'science' that the premise is based on is not science at all?

That's where Anomaly comes in. I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say that the plot of Anomaly involves the simulation hypothesis. This is the idea that everything we experience is not physically real but takes place in a vast computer simulation - The Matrix on steroids. For me, the simulation hypothesis is fun to consider, but is more a matter of philosophy than science.

For a hypothesis to be scientific there has to be some way in principle to test out that hypothesis. We may not be able to undertake the test right now, but it should be possible. Yet the simulation hypothesis does not allow us to do this. To see why, it's useful to bring in the similar but simpler invisible dragon hypothesis. I have a theory that there is an invisible dragon in my garage. Is that science? It's certainly possible to make any scientific test you propose incapable of disproving my hypothesis.

For example, if you try to detect the presence of my dragon by scattering flour on the floor to pick up footprints, I will point out that my invisible dragon is weightless, floating just above the surface of the ground. If you listen for its breathing I will tell you that my dragon does not breathe. If you want to detect it with a heat gun, I will point out that it emits no infra-red. My dragon could exist. But if there is nothing to measure, nothing to observe, science can say nothing useful about it. It isn't a scientific hypothesis.

Some argue that the same problem applies to concepts that are often considered scientific, such as string theory. And it certainly also applies to the simulation hypothesis. If we accept that what we are dealing with is speculative philosophy rather than science, can it really be the basis for science fiction? Some like the term 'speculative fiction' a weak alternative meaning of SF, but (perhaps surprisingly) I think a book like Anomaly can still legitimately be regarded as science fiction.

This is because, in the end, it's the 'fiction' part that matters most. It helps that I do like the occasional alternate history book, such as Kingsley Amis's The Alteration and Keith Roberts' Pavane. Arguably the mechanism of alternate history is not strictly science - but the result is still far closer to SF than it is to fantasy. Similarly, even though the 'science' of a book like Anomaly is totally speculative and incapable of being tested, it feels more like science fiction than fantasy - and that's good enough for me.

I hope you can join us on 22 May 2022 for what should be a lively discussion.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 21, 2022

I'm game

Something that never ceases to be a thrill is receiving my first copies of a new book - so I'm delighted to say that Game Theory, my latest entry in Icon Book's 'Hot Science' series (for which I am also series editor), is now on sale.

Something that never ceases to be a thrill is receiving my first copies of a new book - so I'm delighted to say that Game Theory, my latest entry in Icon Book's 'Hot Science' series (for which I am also series editor), is now on sale.For me, game theory, the topic of the book, has always been a fascinating one. Below is an extract from the introduction to show why this is the case and to give a little background on game theory in case it's unfamiliar as a concept.

You can find out more about the book or buy a copy at my website.

1. Games and the real worldWhen I first bought a textbook on game theory many years ago, never having come across the term before, I felt cheated. I was expecting something fun that would tell me the optimal strategies for winning at card games, backgammon and Monopoly. I wanted an interesting analysis of how the games worked mathematically under the hood. Ideally there would also be guidance on how to create your own interesting board games. Instead, I found descriptions of a series of ‘games’ that no one had ever played, with tables of outcomes that did not so much give guidance as show just how impossible it often was to come up with a useful outcome. This was interspersed with a hefty load of mathematical equations. And yet, the more I read about game theory, the closer it seemed to one of my favourite classics of science fiction.

For his 1950s Foundation series of books (made into a so-so TV show in 2021), Isaac Asimov came up with the concept of ‘psychohistory’. This is an imaginary mathematical mechanism for predicting the future, based on an understanding of human psychology and the behaviour of masses of people. In practice, psychohistory was never going to happen. The repeated failures of pollsters who amass vast amounts of data to predict the outcomes of elections, or decisions such as the UK’s Brexit referendum, make it clear that people form far too complex a system to enable consistent, reliable mathematical predictions of outcomes. Yet game theory does achieve some of the promise of psychohistory by resorting to the classic approach used by science, particularly physics: modelling.

The mathematical models used in physics reduce complex systems to simpler combinations of objects and their interactions. Messy aspects of the system are often ignored (it will be noted that this is happening). So, for example, Newton’s familiar laws of motion at first glance don’t appear to describe the real world very well. The first law states that an object in motion will keep moving unless acted on by a force. In everyday experience, such countering forces – like friction and air resistance – are ubiquitous; yet for convenience, models often ignore such things, as they add complexity and can be difficult to account for. This means that the model does not reflect reality – without friction and air resistance, once you gave it a push, a ball on a flat surface would roll on for ever. But simplification makes calculations more manageable and gives an approximation to reality. Similarly, game theory uses mathematical models that simplify human interactions and decisions as much as is possible to help understand those processes.

The theory of games started with the development of the mathematical field of probability to deal with gambling games and other pastimes where the outcome was dependent on a random source, such as the throw of dice or the toss of a coin. However, in the first half of the twentieth century, a handful of individuals and a quasi-governmental American institution took some of the basic mathematics of games and began to apply it to decision-making problems, ranging from economics to the best strategy to win a nuclear war.

The field that was developed under the name of game theory became detached from ‘real’ games. It was all about strategy – what was the best approach to win, given a set of choices available to two or more players. Games were transformed from pastimes to something deadly serious. This shift was so strong that often those who deal with game theory totally ignore what the rest of the world calls games. However, I believe that this is a mistake. Real games still form part of the continuum – it is just that many familiar games are not interesting from a game theory perspective, either because they are too dependent on random chance, with no strategy, or because they are too complex for strategies to be developed.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 19, 2022

Asteroids, climate change and hyperbole

Science communication is a delicate balance - but there is always a danger of someone highly invested in a particular aspect of science indulging in hyperbole and causing the opposite reaction to the one they intend.

Science communication is a delicate balance - but there is always a danger of someone highly invested in a particular aspect of science indulging in hyperbole and causing the opposite reaction to the one they intend. Arguably, the most dangerous topic for this is climate change. Getting our response to climate change right is crucially important - global warming and its consequences is something we have to take action on. But, as Al Gore demonstrated in the past, making overblown statements on the subject can have a negative impact on getting the message across.

The latest indulgence in this line, which made the news on 15 April, was from palaeontologist Robert DePalma, who apparently said at a screening of a documentary he made with David Attenborough 'What's going on in the world today is terrifyingly close to the scale and timeframe of the end-Cretaceous extinction.'

He was referring to the asteroid impact that wiped out most of the dinosaurs - in fact it did far more, destroying three quarters of the animal and plant species on Earth over a timescale of just a few years. Now, climate change really is causing extinctions. But even with the worst predictions, its impact would not come close to the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event - and we are doing a lot to make sure that the worst predictions don't come true.

To be fair to Dr DePalma, he probably wasn't only talking about the impact of climate change, but the wider destruction of the environment caused by humans, which is responsible for a considerable amount of species loss on top of warming from greenhouse gasses. However, his comments led to newspaper headlines like "Climate change 'like asteroid hitting Earth''.

We have to consider the environment more. We have to get climate change under control. But telling the world that the sky is about to fall in is not the way to get people on your side. It's the same problem as then protests by Extinction Rebellion and Insulate Britain that prevent people getting to hospital or using green electric trains. All this badly thought out communication does is to turn the public against you. By all means get the facts across - but exaggeration is not the way to do it. Science should always be clear and accurate: this is essential if we are to maintain trust. It's not about misrepresenting reality to achieve a goal.

This has been a green heretic production.