Brian Clegg's Blog, page 27

August 10, 2022

Canterbury Festival talk - 20 October 2022

Tickets are now available for my Canterbury Festival talk - Ten Days in Physics that Shook the World - Thursday 20 October, 8pm, Augustine Hall, Canterbury.

Tickets are now available for my Canterbury Festival talk - Ten Days in Physics that Shook the World - Thursday 20 October, 8pm, Augustine Hall, Canterbury.Physics informs our understanding of how the world works – but more than that, key breakthroughs in physics – from thermodynamics to the internet – have transformed everyday life. I will be taking the audience back to ten separate days in history to illustrate how particular breakthroughs were achieved, meet the individuals responsible, and explain how each breakthrough has influenced our lives.

It is a unique selection. Focusing on practical impact means there is no room for Stephen Hawking’s work on black holes, or the discovery of the Higgs boson. Instead we have the relatively little-known Rudolf Clausius (thermodynamics) and Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (superconductivity), while Albert Einstein is included not for his theories of relativity but for the short paper that gave us E=mc2. Later chapters feature transistors, LEDs and the Internet.

Tickets £12 from the Festival website (Incl. £1.50 booking fee).

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 3, 2022

Going grumpy on technology

The wreck of a footpath near homeAt the moment, the streets near our house are a mess as noisy drills are heard all day and large swathes of the pavement are closed off with blue plastic fencing. This is because they are laying a new fibre optic cable.

The wreck of a footpath near homeAt the moment, the streets near our house are a mess as noisy drills are heard all day and large swathes of the pavement are closed off with blue plastic fencing. This is because they are laying a new fibre optic cable.Surely, you may think, this is a good thing. And if we hadn't got fibre optic connections already, it surely would have been and I would have been all in favour. But we already have two fibre providers in our road: Openreach, which is used by a wide range of telecoms companies, and Virgin. So why the need for more disruption? According to the banner for the new provider, City Fibre, their USP is gigabit connectivity (though I could swear Virgin's vans also mention this).

Here's were I go into grumpy old man mode. We already have 100 Mbps guaranteed, typically running at around 130-150 Mbps. That's more than enough for our requirements. Interestingly, our provider recently gave us a free month on 300 Mbps to try out the benefits. They only told us, though, when they were about to take it away. And until then we hadn't noticed any difference, because there's nothing we do online that could make use of that kind of bandwidth.

Why then, should I care that I will have the potential to get 1,000 Mbps (i.e. gigabit connectivity)? I suppose the argument is that before streaming TV, I was quite happy with much lower speeds than we now have. Who knows what the future might bring? Do I hear anyone say 'Metaverse'? But given the current infrastructure can already support 500 Mbps or more, we have a lot of 'who knows' headroom left.

I spoke to Neil Madle, City Fibre's local area manager. When I put to him my doubts, he commented 'It's a good question, one we get asked a lot. True, not every resident needs 1Gb - or anywhere near it, to be honest - but that doesn't mean full fibre shouldn't be the goal...' Full fibre is just marketing speak for the more technical 'fibre to the premises' (FTTP) - but we already have that from both our providers. Neil went on to say that 'If it’s genuine FTTP and not part-fibre FTTC [fibre to the cabinet], then it’s likely we’ll use the BT Openreach infrastructure in your area, as we’re allowed' - but from what's happening outside my office window, it seems that they aren't.

I ought to stress that we're heavy technology users here at Clegg Towers. I do all my work on a connected computer. I quite often have to upload and download large files. Almost all the TV we watch is streamed, while our only radios in the house are smart speakers. I even read the 'newspaper' on an iPad. But I really can't see the need for this disruption to get something that doesn't seem to deliver any benefits.

Bah humbug, City Fibre, bah humbug.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 2, 2022

Marks and Spencer Scan and Shop review

I've recently tried out the Marks and Spencer 'Scan and Shop' app and I haven't had so much fun in ages shopping for a couple of food items. You might think I live in the dark ages. Most of the major supermarkets give you the ability to scan your shopping as you go around the store, while Amazon even has a handful of stores where you simply pick the stuff off the shelves and go.

I've recently tried out the Marks and Spencer 'Scan and Shop' app and I haven't had so much fun in ages shopping for a couple of food items. You might think I live in the dark ages. Most of the major supermarkets give you the ability to scan your shopping as you go around the store, while Amazon even has a handful of stores where you simply pick the stuff off the shelves and go.However, here in the Wild West we don't have those Amazon shops, and there is one huge difference between the M&S experience and the scanners in conventional supermarkets. Go round Waitrose or Asda, say, with a self-scanner and you end up with a trolley load which you take to a till and pay for under the watchful eye of staff. But the M&S app lets you walk around the shop (food section only) scanning stuff and sticking it straight into your shopping bag. At the end you pay on the app, then walk out of the shop, never going near a till.

This is especially useful in our local Marks and Sparks as they only have three self-service tills, crammed into a very small space. But the benefit is not just time-saving on queuing for the till - the biggest boost is the aspect in which it's closer to the Amazon experience than conventional supermarket scanners. There is is simply a wonderful frisson of naughtiness that you get from taking something off the shelf, giving it a quick scan, then dropping it straight into your shopping bag. It really is rather exciting (I probably should get out more).

Clearly this kind of thing has the potential for misuse: after you've paid on the app, you get a screen up with a list of what you've bought which you are encouraged to keep ready, just in case a staff member stops you on the way out. Even this adds to the experience - the possibility of someone pouncing on you and being able to say 'Sorry, it's legit,' with a big grin.

Where I live, we have three food shops in walking distance - a massive Asda supermarket, a smallish Lidl and Marks and Spencer. I'd never do a major food shop at M&S - it's all about picking up a couple of things they do especially well - so this is ideal for my kind of shopping. Anyone need anything? I want another go...

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 1, 2022

Review: Aberystwyth Mon Amour - Malcolm Pryce *****

There is now a genre of TV show known as Cymru Noir, modelled on Scandi Noir but with more drizzle - however, Malcolm Pryce, with his Louie Knight mysteries, brought the original American noir genre to Wales in a series of books starting with the 2001 Aberystwyth Mon Amour, that are sheer genius.

There is now a genre of TV show known as Cymru Noir, modelled on Scandi Noir but with more drizzle - however, Malcolm Pryce, with his Louie Knight mysteries, brought the original American noir genre to Wales in a series of books starting with the 2001 Aberystwyth Mon Amour, that are sheer genius. Pryce could have simply transported a Sam Spade-alike to the Welsh seaside - and that's certainly part of the attraction of these books, but the deadpan humour derives from the fantastical development of what might be considered Welsh stereotypes of old into the key elements of a noir detective novel. So, for example, the druids replace the mafia as the local gangsters, good time girls wear stovepipe hats, the friendly bartender becomes an ice-cream salesman and the tea cosy takes on a much darker meaning.

This is a setting beautifully brought alive in Pryce's lyrical description of Aberystwyth and its surroundings that will be be evocative to anyone who spent a wet week in a Welsh caravan as a child - but Pryce develops a whole mythos around an alternative Wales where, for instance, the country had its own equivalent of Vietnam in a failed attempt to take over Patagonia in 1961 with an attack force that included two ex-war Lancaster bombers.

I've never seen anything like these books by another author. It's a kind of urban fantasy, dark humour, noir crime genre - but the urban fantasy is not so much driven by magic (although there are witches), but rather by Welsh seaside stereotypes taken to the extreme. Where else could you meet schoolboy genius Dai Brainbocs, who has solved a long-thought impossible theorem that makes it possible to change the lettering part way through a stick of rock, the mysterious, stovepipe-hat-wearing nightclub singer Myfanwy Montez or the sadistic ex-freedom fighter and games teacher Herod Jenkins?

I've just started re-reading my set of these six remarkable books, and am enjoying every moment.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

Aberystwyth Mon Amour is available from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

July 30, 2022

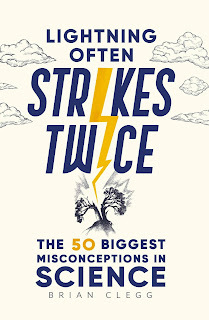

The delights of scientific misunderstandings

I've just had published a fun little book of 50 misunderstandings and misconceptions in science.

Lightning Often Strikes Twice

looks beyond this tip of the iceberg when it comes to what may of us wrongly believe about the world around us. Whether it's word of mouth, myths you've read about online, or misremembered facts from school, we're bombarded by misconceptions about science all the time.

I've just had published a fun little book of 50 misunderstandings and misconceptions in science.

Lightning Often Strikes Twice

looks beyond this tip of the iceberg when it comes to what may of us wrongly believe about the world around us. Whether it's word of mouth, myths you've read about online, or misremembered facts from school, we're bombarded by misconceptions about science all the time.In a light way, the book explains the real science and theory that debunks these popular myths. From fears about the exponential growth of the human population to the misapprehension that we are all descended from chimpanzees or gorillas, the book separates science fact from fiction.

For your delectation here's one of the 50 articles in the book:

A coin dropped from the top of the Empire State Building can kill youThe Empire State Building doesn’t even make it into the fifty tallest buildings in the world any more. At the time of writing, it’s only the seventh tallest in NewYork City. Yet the combination of it topping the world’s building height charts for a lengthy period between 1931 and 1972 and its appearance in over two hundred and fifty films, starting with the iconic scene in King Kong, mean that it remains a visual and emotional touchpoint for anything requiring a significant measure of height.

Image by Guille Sánchez from UnsplashIt is likely that the idea that a coin dropped from the top of the building would be deadly to someone on the sidewalk below arose when the Empire State Building still held its crown as the tallest building in the world. It seems quite a reasonable assertion. After all, many coins are heavier than bullets, and a bullet can cause terrible damage. The amount of oomph with which something hits a target is measured by its momentum– the mass of the object times the velocity at which it travels. Current British coins weigh between 3.5 and 12 grams (0.12 to 0.4 ounces), while US coins range from 2.3 to 11.3 grams (0.08 to 0.4 ounces). Not a lot. But the deadly capabilities of a falling coin rest on the assumption that it can get up to a considerable speed when dropped from the height of the Empire State Building.

Image by Guille Sánchez from UnsplashIt is likely that the idea that a coin dropped from the top of the building would be deadly to someone on the sidewalk below arose when the Empire State Building still held its crown as the tallest building in the world. It seems quite a reasonable assertion. After all, many coins are heavier than bullets, and a bullet can cause terrible damage. The amount of oomph with which something hits a target is measured by its momentum– the mass of the object times the velocity at which it travels. Current British coins weigh between 3.5 and 12 grams (0.12 to 0.4 ounces), while US coins range from 2.3 to 11.3 grams (0.08 to 0.4 ounces). Not a lot. But the deadly capabilities of a falling coin rest on the assumption that it can get up to a considerable speed when dropped from the height of the Empire State Building.The exact height involved is a little vague as the Empire State Building is topped with a radio mast and a high pointy roof (added to the original design to make sure it was taller than the rival Chrysler Building) – but even if the coin thrower were to climb to the upper parts King Kong style, it would be extremely difficult to throw a coin and manage to get it over the edge of the building, so we probably have to assume that the coin would be dropped from the observation deck 320 metres (1,250 feet) above the pavement below.

How fast, then, would the coin be going when it reached its potential victim? The starting point is the acceleration due to gravity. Although the Earth’s gravitational pull drops off as you move away from the planet’s surface, the building’s height has a trivial effect. Gravity acts as if the planet’s mass were concentrated at its centre.When we stand on the Earth’s surface, we are on average 6,371 kilometres (3,959 miles) from the centre. There is not going to be much difference between 6,371 kilometres and 6,371.32 kilometres.

The acceleration due to gravity at the Earth’s surface is 9.8 metres (32 feet) per second per second. That’s to say, after 1 second you are travelling at 9.8 metres (32 feet) per second, after 2 seconds at 19.6 metres (64 feet) per second and so on. Working out the speed this implies would be reached in a fall of 320 metres is not totally trivial, but there are plenty of calculators out there. If nothing else were involved,a coin would take 8 seconds to make the drop and would arrive travelling at around 79 metres (259 feet) per second. Going for a coin of 10 grams (0.35 ounces), this would give a momentum of 79 × 0.01 = 0.79 kilogram metres per second. To put that into context, a handgun bullet can have a momentum of around 450 × 0.007 = 3.15 kilogram metres per second – around four times as much. (Converting this to non-metric units is messy and probably no more meaningful.)

In practice, though, there’s another consideration. The air. We tend to ignore it, but falling objects are slowed down by the atmosphere’s resistance to objects moving through it. As a result, any object has a ‘terminal velocity’ – the fastest speed it will fall through air, depending on how much resistance the profile of the object puts up. (This is why a parachute, with much more surface area presented to the air, slows a person’s descent, compared to falling without one.)

For a typical person, that terminal velocity is around 55 metres per second (180 feet per second) belly down – for a coin it’s likely to be around 28 metres per second (92 feet per second), which would take its momentum down to around a twelfth of that of a bullet.

Being hit by a coin falling from the Empire State Building would certainly be unpleasant – but it won’t kill you. The TV show MythBusters created a special gun to fire a coin at the appropriate rate and showed that it was survivable (please don’t try this at home). And a more comparable experiment from around 2007 showed that coins were even less dangerous than the MythBusters experiment suggested.

Louis Bloomfield, a physics professor from the University of Virginia, devised an experiment that automatically dropped a whole cache of coins from a weather balloon, high enough up for them to reach terminal velocity. He claimed that they didn’t hurt, feeling like the impact of heavy raindrops. Bloomfield used one cent coins, lighter than the weight used above, but also found an additional slowing factor. The coins’ unstable fluttering tended to reduce their speed to as little as 11 metres per second.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

Find out more about the book or buy a copy here.

July 25, 2022

Can Magical Thinking Improve Teamwork?

Usually, 'magical thinking' is a reference to fooling yourself into believing something that isn't possible, but Mark Mason suggests that solving the mystery of how magic tricks work can help you think more effectively.

Usually, 'magical thinking' is a reference to fooling yourself into believing something that isn't possible, but Mark Mason suggests that solving the mystery of how magic tricks work can help you think more effectively. He's running team building sessions where he performs tricks, then helps those present work together to uncover how the trick was performed. Mark says that he reveals mental techniques that will let you solve pretty well any trick you’ll see in the future - and that these techniques can be applied to problems you’ll encounter at work and in life more generally.

As I know there are a lot of blog posts out there that are really paid adverts, I ought to stress I'm not being paid to publicise this, and I only know Mark as a reader who contacted me previously about my book Inflight Science.

What interested me here was that in the period between working in Operational Research and computing in British Airways and becoming a full time writer, I ran creativity training sessions for large companies. My experience from that time suggests that everyone could benefit from help to think more creatively and can improve their problem solving skills. Mark's approach seemed an original (and fun) way to help participants to think differently - and who doesn't love trying to work out how magic tricks are performed?

I asked Mark a few questions about the approach:

What’s your background? I’ve done lots of things - writing books and journalism, making radio programmes for the BBC, leading guided walks in London, busking on the Tube. A ‘portfolio career’, as it’s called these days.

How did you get interested in magic? I learned some tricks as a child - then rediscovered them when my own son came along. From that I started doing them for his friends, and then his friends’ parents. I realised that I hated the distance magic can put between people ('I know how it’s done, you don’t, nur nur nur nur’) - but I loved leading people towards the secret. It’s a bit like a joke - the trick is the set-up, the secret is the punchline.

Why do you think learning magic tricks works as a team building exercise? In the sessions I do the tricks I don’t tell you how I’m doing them… you have to work out how they're done. With some hints from me, of course. What's wonderful is that the team always achieves more than any individual could on their own. Someone will get 70% of the way to solving a trick, but it takes someone else to chip in with the final 30%. By the end of the session everyone has contributed, and they all feel 10 feet tall.

How can the techniques learned be applied to more general problem solving? A key element is to avoid trying to solve the trick/problem in isolation. Don’t look at the situation now, work out how you got there. Instead of saying ’the coin vanished from your hand’, ask how I picked the coin up in the first place, what I was saying as I did so, when and where you last saw the coin for sure… Instead of saying 'this part of the business isn’t working properly’, ask how it was set up originally, how it developed into its current form, when and where the problems started to occur...

I’m really clumsy - when I’ve tried to do magic tricks I often messed them up - any tips? First pick the right tricks - a lot of the best ones (even those performed by professional magicians) are self-working, and don’t need any difficult sleight of hand or even misdirection. (Obviously I major on these in the sessions, so people can take them away and do them for friends and family.) And even where there is some tricky handling to practise, the key is 'little and often’. I often tell people it’s like getting a new phone - the buttons and icons might be in different places, but because you use them so often you soon get used to the new way you have to hold the phone to adjust the volume/reach a certain app/etc.

What’s next for you? There’s always a new false shuffle to learn...

You can find out more at Mark's website. Here he is in action:

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

July 24, 2022

The best theoretical physics from the last 30 years?

Image by Thomas T from UnsplashI recently reviewed a book called Fantastic Numbers and Where to Find Them by Antonio Padilla. In my review, I was dubious about the way that Dr Padillia referred to the highly speculative holographic principle as 'the holographic truth'.

Image by Thomas T from UnsplashI recently reviewed a book called Fantastic Numbers and Where to Find Them by Antonio Padilla. In my review, I was dubious about the way that Dr Padillia referred to the highly speculative holographic principle as 'the holographic truth'.Something many publishers drum into their authors is that it is not a good idea to respond to reviews. If anything, it can reinforce any negative comments in the review. But Dr Padilla replied on Twitter 'thanks for your thoughts. You may be interested to see this perspective on importance of the holographic principle, which obviously I share.’ He then quotes Caltech physicist John Preskill, who had tweeted: ‘Someone asked: What are the most important ideas in physics over the past 30 years? Three immediately came to mind: The holographic principle, topological order, quantum error correction.’

Now, this seemed to me to be a depressing statement if true. What we've got with those three is firstly a principle that is largely self-referential maths that has no current way of being tested. Then there's something quite interesting if not giving huge insights or new experimental directions, but that actually predates the last thirty years. And finally there's a very important and useful mechanism that is an important contribution to physics-based engineering - but can it really be so significant in the annals of theoretical physics?

Bear in mind the last thirty years has seen a whole host of experimental breakthroughs, from the detection of the Higgs boson to gravitational waves. Could it be that major developments in theoretical physics have been so sparse? I asked theoretical physicist and science communicator Sabine Hossenfelder whether she agreed with those three ideas. She pointed out that one problem is that many scientists measure the importance of an idea by the number of people who work on it or the number of papers that have been written about it.

This clearly isn't a useful measure of the significance of a piece of theory. After all, vast numbers of people have worked on theories such as string/M theory which seem to have run out of steam. Similarly, many papers have been written on the existence of dark matter, which has as a theory been tested by large numbers of experiments that have failed to detect it - increasingly it seems likely that alternative theories, such as variants of modified gravity, have more potential.

Dr Hossenfelder highlights two potential big developments in relatively recent theory - topological phases of matter and phase transitions (see the Nobel Prize in Physics for 2016 for more detail) and chaos control, which she noted was highly valuable both in robotics and nuclear fusion.

Of course any attempt to do a 'best of' list is subjective - and that wasn't my aim here. Relying on either number of papers produced or an individual's hits list is not a good way to give support to a theory. I may be biassed, but for me theories can only be considered to have proved their worth once they can be directly supported by experiment or observation. For the moment, I'd suggest, the holographic principle remains a mathematical curiosity rather than truly valuable physics.

July 15, 2022

Review: How to be a Writer - Marcus Beckman ****

There seem to be three obvious markets for this book - people who are interested in what writers do, people who would like to be professional writers but aren't, and writers themselves. That last category may seem an unlikely one - if you are already a writer, why would you need a book called 'How to be a writer'? But the reality is I spent some of my cash, hard-earned from writing, on this book.

There seem to be three obvious markets for this book - people who are interested in what writers do, people who would like to be professional writers but aren't, and writers themselves. That last category may seem an unlikely one - if you are already a writer, why would you need a book called 'How to be a writer'? But the reality is I spent some of my cash, hard-earned from writing, on this book.The reason the book appealed, I think, is the familiar concept of readers liking to identify with a book. This has led to much more diversity, for example, in fictional characters - but it is also engaging to read about someone who does a similar job and their experiences, especially when the narrative is handled in such a light and entertaining way as Marcus Berkmann does here.

I can certainly identify with much of Berkmann's working life - both the highs and lows of being a freelance writer. What's particularly fun is that Berkmann has written a whole range of columns and reviews, from off-the-wall observations on life to sometimes astringent reviews of books, music and films. Obeying one of the essential rules of being a freelance - always reuse material if you can - Berkmann peppers the book with examples of his writing from his long-running career, including pieces that have appeared in both national newspapers and familiar magazines. He's always prepared to indulge in some humorous self-criticism, which works particularly well in this context.

There is one aspect of the trade that I don’t think Berkmann has got a handle on: the difference between being a London-based writer and the rest of us. He tells us that lots of writers he knows don’t drive - try that if you live in the country. Similarly, he seems to spend a lot of time at publisher parties and book launches. When I get invited to something like that (because they’re always in London) I have to factor in half a day’s travel and hefty transport costs. So I rarely do it for the distinctly limited benefits that accrue.

This minor point aside, How to be a Writer is a very entertaining little book, ideal, as I used it, as a non-taxing holiday read. Recommended.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

How to be a Writer is available from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

July 8, 2022

Junior school science

One of my favourite activities is giving science talks in junior schools. I don't write children's books, though some of my titles are fine for an intelligent eleven-year-old, but what comes across in a wonderful way is the sheer enthusiasm for science felt by the children. This isn't limited to a few enthusiasts - everyone gets excited about science presented the right way. When, for example, I mention that they have atoms in their bodies that were previously in dinosaurs, there's always a collective 'Whoa!' - while a set of simple refracting glasses that produce rainbows from sunlight genuinely give a thrill.

One of my favourite activities is giving science talks in junior schools. I don't write children's books, though some of my titles are fine for an intelligent eleven-year-old, but what comes across in a wonderful way is the sheer enthusiasm for science felt by the children. This isn't limited to a few enthusiasts - everyone gets excited about science presented the right way. When, for example, I mention that they have atoms in their bodies that were previously in dinosaurs, there's always a collective 'Whoa!' - while a set of simple refracting glasses that produce rainbows from sunlight genuinely give a thrill.When I was at junior school, I'm delighted to say our teachers took science seriously, while making it fun. Unhampered by a restrictive curriculum, they allowed us to do experiments - and to fail. Admittedly it helped that my junior school building was inherited from a re-housed secondary school and had cupboards full of interesting scientific equipment. Sadly, the former Littleborough County Junior School has now disappeared to become a housing estate - though its position opposite Hare Hill park (which we used to walk across to visit the library) seems to have been memorialised by calling a footpath 'School Walk'.

I remember particularly two failed experiments, both of which provided useful lessons. One involved blowing between a pair of suspended table tennis balls. This was part of a whole series of little experiments on a sort of science trail - we only had a limited time to complete them and I remember thinking that it really wasn't necessary to waste time doing the experiment, I would just write down what I thought should happen. Not only did this get me a lecture, still remembered many years later, on the importance of honesty in science, it was a powerful lesson not to rely on assumptions. No, they didn't blow apart, they moved closer together.

The other experiment was not a failure because of my cheating, but rather because it was an experiment to show a 'scientific' fact that turned out to be a myth. We had been told about the way that our tongues had different regions, which were responsible for different tastes such as sweet, salty and sour. The experiment involved poking our tongues with wooden spatulas and recording the taste sensation. While some of us did feel they experienced different tastes (the teacher, like many scientists at the time, hadn't grasped the importance of avoiding giving us expectations of specific outcomes), the results were inconsistent, and many of us had no sensations at all.

The other experiment was not a failure because of my cheating, but rather because it was an experiment to show a 'scientific' fact that turned out to be a myth. We had been told about the way that our tongues had different regions, which were responsible for different tastes such as sweet, salty and sour. The experiment involved poking our tongues with wooden spatulas and recording the taste sensation. While some of us did feel they experienced different tastes (the teacher, like many scientists at the time, hadn't grasped the importance of avoiding giving us expectations of specific outcomes), the results were inconsistent, and many of us had no sensations at all.The whole idea of the 'tongue map' for different taste sensations was fictional, based on a misinterpretation of a legitimate piece of research. But the myth proved surprisingly resilient.

I was reminded of this experiment when writing one of the 50 articles on science myths, some of which persist to this day, in a new little book Lightning Often Strikes Twice, which is out on 21 July 2022. There's something really interesting about scientific myths, which arise for all kinds of reasons. It might be wishful thinking or misunderstanding. Sometimes it's just a matter of something that sounds reasonable when applying common sense... but the world just doesn't work that way. Whatever the reason, these may be misconceptions, but they're fun to encounter.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

June 24, 2022

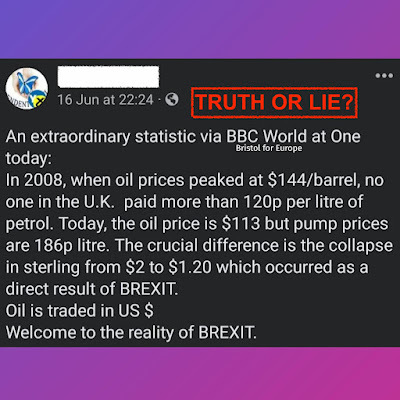

Beware statistics bearing gifts

Numbers are a powerful way of strengthening a message - and when we see a statistic that backs up a strongly-held belief, it can be very easy to share it without thinking too much about it. But all statistics benefit from a quick check before use - and it's doubly important to do so when they tell us what we want to hear.

Numbers are a powerful way of strengthening a message - and when we see a statistic that backs up a strongly-held belief, it can be very easy to share it without thinking too much about it. But all statistics benefit from a quick check before use - and it's doubly important to do so when they tell us what we want to hear.A couple of days ago, I saw this message on a friend's social media. (I've removed the name at the top and added the words in red - otherwise it is unchanged.) The message is stark. But a couple of things worried me about it.

Firstly, that subscript of 'Bristol for Europe' seemed a bit odd. It's clearly not part of the original post, and how exactly could the information come from both the BBC and a pressure group?

But more importantly, the exchange rates quoted didn't feel right. I was sure sterling suffered as a result of Brexit (or, rather, BREXIT - being shouty is another flag that checking of data is required) - but a change like this would result in products priced in dollars, such as iPhones, shooting up in price, which I didn't remember happening.

On checking the actual numbers, it is true that the dollar exchange rate was, at times, $2 to the pound before Brexit - but the last time it had been was December 2007, nine years before the referendum. And for that matter, the exchange rate had also been lower than it is now before Brexit. In February 1985 it dipped to $1.09 to the pound. Big surprise - exchange rates fluctuate all the time.

As you might expect, the exchange rate did fall after Brexit. The day before the result was announced it was $1.48. After the announcement it was $1.32 and it fell as low as $1.31 a few days later. Since it has rallied, getting back as high as $1.42 and dropping to $1.15 on the date of the UK's first lockdown. At the time the illustrated message was posted, it was moving around the $1.22 to $1.25 mark.

The phrase that Mark Twain ascribed (probably inaccurately) to Disraeli, 'there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics' is much misused. Statistics are very valuable to make clearer what is going on. However, sometimes, as here, the numbers really are lies - and even when they technically are true, they are always worth looking into, because the context can make a huge difference.

It's particularly important to double check validity when you have a strong emotional attachment to the sentiment behind the numbers - because that's when you are most vulnerable to being deceived.