Brian Clegg's Blog, page 19

September 2, 2023

The Real McLegg

The writing community is quite rightly worried about generative AI in two ways. Can a writer be replaced by something like ChatGPT, and could we be accused of using generative AI to do our work for us? One possible solution is to use AI itself to fight back. But before getting into the detail, I ought to explain why this piece isn't titled 'The real McCoy'.

The writing community is quite rightly worried about generative AI in two ways. Can a writer be replaced by something like ChatGPT, and could we be accused of using generative AI to do our work for us? One possible solution is to use AI itself to fight back. But before getting into the detail, I ought to explain why this piece isn't titled 'The real McCoy'.That was my first inclination for a title (and I'm sure ChatGPT would have gone with it). It would have given me an opportunity to lever Star Trek into the discussion, and it's a familiar phrase that highlights the issue we're dealing with. According to my trusty Brewer's, the phrase was originally 'the real MacKay' in Britain. A lot of people apparently thought the US version was based on a US boxer called McCoy, but apparently it arose (not entirely surprisingly) in Scotland and was exported to the US as a way of highlighting true Scotch, as opposed to US whiskey.

I switched the title to 'the real McLegg' because it's somehow the sort of thing I couldn't imagine a generative AI coming up with - and there is a sort of reason. I have been addressed in the past as Mr McLegg. This is because one of my early email addresses (with Yahoo, I think - I can't remember why I had it) was brianmclegg@... - brianclegg@ had already gone, so I deployed my rarely used middle initial.

All of this is a long winded way of getting to a new feature from Authory, the content system I use to make my online writing more widely available. Authory makes a copy of everything written by me online on sources I tell it about. Others can then take a look at what I've written or subscribe to a free weekly digest of my work. I've found it very useful for this. But the people behind Authory have been experimenting with AI and have come up with a cunning scheme to help writers establish their non-AI credentials.

Because Authory has access to thousands of articles by me, it can build a picture of what my writing style is like. As is the case with most writers, I don't always produce the same kind of stuff, so rather than have a single 'digital fingerprint' it produces quite a few - in my case, over 1,000 of them. These are all based on items written pre-December 2022, so won't have any generative AI content. The system then compares new writing against those fingerprints, and can make a reasonable assessment of whether or not the vast majority of my writing is human generated. If this is the case, it generates a certificate. The pretty aspect of this is the image above, but a would-be checker can also click on this link and see more detail about the basis of my certificate.

The concept did bring up a few doubts that I've contacted Authory about. My content includes interviews and guest posts, where almost all the text wasn't written by me. Perhaps more worrying, I have intentionally (and obviously) included text written by ChatGPT, such as this article on a 1960s SF story about computer-generated writing that seemed to prefigure ChatGPT. In the article, I asked the generative AI to produce a story like one mentioned in the original. I'm reassured by Authory founder Eric Hauch that a few articles written by others won't damage my fingerprint, and that 'A part of an article that's been framed by you as coming from ChatGPT will not put your certificate at risk. The algorithm behind this is pretty extensive and won't be thrown off by things like this'.

Of course there are limitations on what the certificate indicates. It's only being assessed twice a year (the next time in October). And the chances are that the occasional ChatGPT written article (something I have no intention of using) might slip through the net. But it's arguably reassuring for readers to know that my blogs are not hotbeds of AI generated nonsense. I'm perfectly capable of generating my own.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

August 21, 2023

Would anyone notice Hozier striking?

I see that the Irish musician Hozier has announced that 'he would consider striking over the threat artificial intelligence poses to his industry.' This was taken seriously enough by the BBC News to put it under their high profile Newsnight brand.

I see that the Irish musician Hozier has announced that 'he would consider striking over the threat artificial intelligence poses to his industry.' This was taken seriously enough by the BBC News to put it under their high profile Newsnight brand.I'm also not sure how much music artists are truly under threat from AI. Hozier himself suggests he isn't sure if AI-generated music 'meets the definition of art'. More to the point, the music business is about a package, not just a song and AI would have to come on considerably to be able to deliver the whole thing. No doubt a few AI-generated songs could be successful in terms of streaming - but it seems unlikely the music business as a whole would suffer too much.

But even if the threat is serious, I can't help but thing Hozier (dangerous autocorrect tendency to make him hosiery) has a weak grasp of economics. While I'm sure that Hozier fans would be disappointed by his disappearance from the scene, the reality is that the music business is not short of competition. If railway workers strike, travellers suffer because there are limited alternatives. However, if a single artist strikes, only a tiny percentage of music lovers will notice - and I suspect there are very few Hozier fans who don't listen to anyone else.

Of course, the hope appears to be, as with the Hollywood strike, that this wouldn't be a single individual walking out, but rather a large number of performers. Even with this comparison, though, I'd suggest the music business is very different from the movies. Hollywood is a dominant force - and there are relatively few big movies made. Thousands of songs emerge on the market every week - there's always something and someone new. And though I don't suggest it's easy to become a music star, it takes far less (especially in the internet age) for a song to get out there and get noticed - especially, perhaps, if some of the bigger names are on strike.

When it comes down to it, Hozier striking would be a bit like your local independent coffee shop going on strike. It would be a shame for the regulars, but it's not going to make much of a ripple in the market as a whole.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here Image by Hugo L. Casanova (not of Hozier) from Unsplash

August 9, 2023

The ChatGPT of 1964

In the months since ChatGPT and other examples of Generative AI arrived on the scene, plenty of writers and artists have had a genuine concern for their future careers. We now know that these systems have some distinct flaws in writing non-fiction - they struggle to identify the difference between reality and the made up stuff, and have been quite happy to, say, fabricate references because they've spotted references are a good thing, but not that they have to be real. However, this is less of a problem in the field of short fiction, where things are supposed to be made up.

In the months since ChatGPT and other examples of Generative AI arrived on the scene, plenty of writers and artists have had a genuine concern for their future careers. We now know that these systems have some distinct flaws in writing non-fiction - they struggle to identify the difference between reality and the made up stuff, and have been quite happy to, say, fabricate references because they've spotted references are a good thing, but not that they have to be real. However, this is less of a problem in the field of short fiction, where things are supposed to be made up.When it comes to poetry, although Generative AI can come up with unsubtle stuff (one of the few things it seems quite good at is rap), it struggles for sophistication - but it's very easy to imagine, had there still been a demand for it, that the systems would be good at the kind of pulp fiction that used to be regularly consumed by the masses prior to the 1970s, and that still has a small toehold in, for example, romance.

It's fascinating, then, that fellow popular science writer Andrew May has uncovered an SF short story from 1964 that imagines a piece of technology able to churn out pulp stories, ready formatted. The story, Author! Author! (no relation to the Isaac Asimov story of that name) appeared in the 10th August edition of the cheap and nasty looking comic Unusual Tales - you can read the story here. There is no author cited (though Andrew wonders if it is Joe Gill, who seems to have produced a lot of material for Charlton Comics at this time) - but the author was assuredly human, unless a time machine was involved.

In the story, a scientist has a computer that 'will write all kinds of stories. Thus we save the money we pay to writers. In addition, it sets the type, does the printing, editing and binding. So we don't have to pay any person a salary.' The device has a series of controls similar to the specifications you might give to ChatGPT, to indicate, for instance that you want a Western, around 2500 words in length, with a hero who is a sheriff and a villain who is a gambler. We can add in other items, such as a heroine who might the daughter of the villain, and a fight. And off it goes.

In the story, the machine gets stuck and produces stories that are a messy mix of genres. The investors are horrified - but it turns out the public love the resultant garbage, thinking it's a satire.

The mixed-genre ending of the story apart, the echoes of ChatGPT and its cousins are quite remarkable. Just to underline this, I asked ChatGPT to give me a 2500 word Western story where the hero is a sheriff, the villain is a gambler, there's a fight scene and the heroine is the villain's daughter. It produced the story below. Is it great fiction? Certainly not. But it certainly fulfils the promise of Author! Author! and is, frankly, as good as much of the pulp fiction of the first half of the twentieth century.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

Shadows of Redemption

In the rugged town of Dusty Ridge, the sun-baked streets were as unforgiving as the people who walked them. Law was maintained by a single, unwavering figure – Sheriff Caleb Morgan. A man with a past as weathered as his worn-out Stetson, he was known to be unyielding in his pursuit of justice, despite the scars that marked his soul.

Dusty Ridge had seen its share of villains, but none were as infamous as Jasper "Snake-Eye" McCallister. A cunning gambler with a heart as cold as the desert night, Snake-Eye had a reputation for cheating at cards and stealing hearts, all while leaving a trail of chaos in his wake. He owned the Silver Dollar Saloon, a place where smoke wafted through the air like lost dreams and poker chips clinked like promises on the edge of being broken.

The tension between the sheriff and the gambler had been building for years, a fuse waiting for the spark. That spark came when a beautiful, mysterious woman arrived in town, capturing the attention of every man, woman, and even a few stray dogs. Elena McCallister, the daughter of Snake-Eye himself, possessed an air of danger that could rival the wild west itself. With raven-black hair and eyes that held secrets, she was both a riddle and a revelation.

It was a crisp morning when Sheriff Morgan saw Elena for the first time. She was perched on the steps of the Silver Dollar Saloon, watching the town come alive with an intensity that matched the sun’s rising glow. He felt her gaze upon him as he strode down the street, his spurs ringing out a steady rhythm that matched his determined heartbeat.

"Morning, Sheriff," she purred, a playful smile tugging at her lips. Morgan's jaw tightened, his eyes narrowing at the familiarity that she dared to display.

"Elena McCallister," he acknowledged with a curt nod, his grip on his Colt subtly tightening. "What brings the daughter of a notorious gambler to Dusty Ridge?"

She leaned forward, her eyes locking onto his with an unsettling intensity. "The same thing that brings everyone to these parts, Sheriff – the thrill of the unknown."

A flicker of something unreadable passed over Morgan's eyes before he turned away, his long coat billowing behind him like a cloak of authority. He could feel her gaze burning into his back as he strode away, knowing that this encounter was merely the beginning of something darker on the horizon.

As days turned into weeks, the tension in Dusty Ridge grew thicker, like the brewing storm that had yet to break. Morgan's hunch proved true as Snake-Eye McCallister's schemes began to unravel, his clever tricks exposed and his wealth of ill-gotten gains diminishing. The townsfolk started to whisper that perhaps the gambler's luck was finally running out.

One fateful evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, casting an amber glow over the town, Sheriff Morgan stepped into the Silver Dollar Saloon. The air was thick with the scent of whiskey and sweat, and the tension was palpable as he approached the poker table where Snake-Eye sat, his eyes sharp and calculating.

"Evenin', Sheriff," Snake-Eye drawled, a sardonic smile curving his lips. "Care to join us in a hand of cards?"

Morgan's gaze bore into Snake-Eye's, the two men locked in a silent battle of wills. "I ain't here to play games, McCallister. I'm here to put an end to your reign of deceit."

With that, chaos erupted in the saloon. Tables overturned, chairs flew, and the sound of breaking glass harmonized with the cries of men caught in the crossfire. Morgan's fists clenched and his fists flew as he fought his way to Snake-Eye, his years of law enforcement experience giving him the edge in the brawl.

Amidst the chaos, Elena watched from the shadows, her eyes torn between the two men who held her fate in their hands. Her father fought with a desperation born of a cornered animal, while the sheriff fought with a steely resolve that spoke of a deeper purpose.

As the fight reached its climax, Morgan delivered a final blow that sent Snake-Eye crashing into a table, his defiant spirit finally broken. The saloon fell silent, save for the ragged breaths of men who had just walked the line between life and death.

Sheriff Morgan stood amidst the wreckage, his knuckles bloodied and his breath heavy. He turned to face Elena, who had stepped out of the shadows, her eyes filled with a mixture of anger and relief.

"Your father's reign ends tonight, Elena," he said, his voice weary but resolute. "But you have a choice – to continue down the path he walked, or to forge a new one."

Elena's gaze wavered before she turned to her defeated father, his pride shattered and his world collapsing around him. She looked back at the sheriff, her resolve hardening like steel.

"I choose a new path, Sheriff. For Dusty Ridge, for my father, and for myself."

And so, the story of Dusty Ridge reached its turning point, as the hero and the heroine chose redemption over revenge, and the town began to heal from the wounds inflicted by a villain's greed. Sheriff Caleb Morgan had faced down the darkness within himself and the shadows that had haunted his past. Elena McCallister, once entangled in her father's web of deceit, emerged as a symbol of resilience and the power to choose one's destiny.

The sun continued to rise and set over Dusty Ridge, casting its golden light upon a town that had seen its fair share of struggles. But now, with the sheriff and the heroine by its side, it stood as a testament to the enduring spirit of the West – a spirit that could overcome even the darkest of shadows.

August 8, 2023

The battle for small electrical recycling

For years now I have occasionally troubled my local council (Swindon) with emails about a failure in their recycling collections. At the moment the council collects, for example, plastic to recycle and/or burn. Which is fine - we don't particularly want it in landfill - but it is neither an important natural resource nor does it have any value to speak of. However, the council doesn't collect small electrical items.

For years now I have occasionally troubled my local council (Swindon) with emails about a failure in their recycling collections. At the moment the council collects, for example, plastic to recycle and/or burn. Which is fine - we don't particularly want it in landfill - but it is neither an important natural resource nor does it have any value to speak of. However, the council doesn't collect small electrical items. Up to now I've had zero useful response to my emails. Our previous Conservative-led council ignored my emails to the council lead on waste, while my local councillor simply said 'We don't do that, people can take small electricals to the recycling centre, and some supermarkets have bins for batteries.' If you have a single battery, a phone cable, a charger or whatever, none of which should go into the landfill bin, you are expected to book an appointment and drive (in my case) a ten mile round trip to the recycling centre. That's great for climate change, guys. And then there's the battery recycling bin at my supermarket. It is a) always overflowing and b) doesn't take bigger (much more valuable) batteries like old laptop batteries.

Out of interest, I emailed our new local councillor, who is Labour. He replied saying it was an interesting idea, and could I identify another council doing this. As it happens, an adjacent council (Vale of the White Horse) does collect small electricals. Huge pat on the back to Vale of the White Horse. I was told the councillor will pass on the suggestion and let me know the outcome. We shall have to see if I get any further response or if the suggestion was filed in the (recycling) bin.

Surely, this is a no-brainer? Lithium ion batteries contain crucial materials for everything from smartphones to electric cars, yet at the moment they are mostly sent to landfill. Bizarrely, those horrible single-use vapes, which can't be recharged, almost all contain rechargeable lithium batteries. Not only is this wasting an important raw material, they tend to catch fire under stress and have already caused several fires in bin collections and landfill sites.

A council has to be realistic about recycling and make it easy to do if they want to make it work. No one is going to take a phone cable, an AA battery or even a toaster (which these days contain electronics) to a recycling centre. They will sigh and dump them in the landfill bin. And you can't blame them. It's time every council collected small electrical waste. You know it makes sense.

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here Image by Roberto Sorin from Unsplash

August 7, 2023

Galata (Fantasy) - Ben Gribbin ****

This is an unusual and atmospheric book. It's described as speculative fiction, but I'd call it fantasy for reasons I'll go into in a moment. The setting is a city that reminds me in some ways of Gormenghast - like Mervyn Peake's imaginary location, this fictional setting is ancient and decaying - what's more it's dominated (in the week in which the story is set) by pointless ritual. The city of Galata is being overtaken by the tides - so another point of reference is the dark feel of the movie version of Du Maurier's Don't Look Now. A final piece of fiction it brought to mind was Henry Gee's dark and horrifying murder mystery

By the Sea

.

This is an unusual and atmospheric book. It's described as speculative fiction, but I'd call it fantasy for reasons I'll go into in a moment. The setting is a city that reminds me in some ways of Gormenghast - like Mervyn Peake's imaginary location, this fictional setting is ancient and decaying - what's more it's dominated (in the week in which the story is set) by pointless ritual. The city of Galata is being overtaken by the tides - so another point of reference is the dark feel of the movie version of Du Maurier's Don't Look Now. A final piece of fiction it brought to mind was Henry Gee's dark and horrifying murder mystery

By the Sea

.Galata, too has an element of murder mystery. As the week-long festival that is supposed to hold back the sea is underway, someone is killing young women. The central character, Joseph, is a former policeman and becomes involved in the distinctly half-hearted investigation of these deaths, which seem increasingly linked to a past event. The sequence of killings adds intrigue and suspense to what is initially a rather tell-heavy story, opening with a lengthy description of location and settings without significant human interaction. It's worth getting through this, though - once things started happening, I wanted to find out more.

Exactly what 'speculative fiction' describes is a matter for dispute. It's often taken as an alternative label for science fiction, used by literary fiction writers and their fans who look down their respective noses at the genre. But there is no science fiction aspect to this novel. For me, the combination of the fictional location of Galata and the grotesque nature of the festival rituals makes this more properly described as a fantasy - not of the swords and sorcery variety, but rather the kind of thing Gene Wolfe was so good at coming up with.

Inevitably, given the topic, this isn't an uplifting book that sends the reader away with a smile on their face and a spring in their step, but I found it highly engaging once I got into it and I'm glad I read it.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Galata as paperback from Amazon.co.uk and on Kindle at Amazon.co.uk

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

July 23, 2023

Am I a discriminating author?

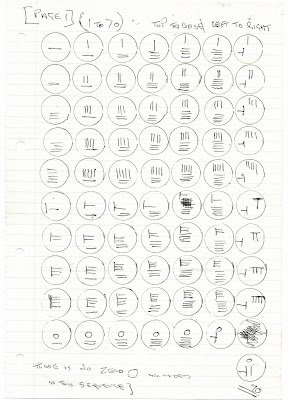

Like all popular science authors, I get my fair share of communications from people sharing with me their new theories, whether they be an alternate theory of gravity or time, or disproving quantum physics. In the old days, these used to come as letters via my publisher - I particularly treasure examples with impressive diagrams such as the one illustrated.

Like all popular science authors, I get my fair share of communications from people sharing with me their new theories, whether they be an alternate theory of gravity or time, or disproving quantum physics. In the old days, these used to come as letters via my publisher - I particularly treasure examples with impressive diagrams such as the one illustrated.These days, of course, they tend to be emails, but usually my response has to be that I'm a science writer, not a working physicist (or mathematician) and I'm simply not qualified to comment on their theories. Sometimes, though the email is rather different.

The other day, I got one asking me if I was intentionally filling one of my books with 'people of many diverse backgrounds'. It is true that some publishers will request more quotes from women or scientists, with diverse ethnic backgrounds, though when writing a primarily historical book, like my Ten Days in Physics that Shook the World, there is a limited pool of individuals to include. But that wasn't the case with the book I was being asked about. I certainly make sure that I select from the the full diverse set of options when quoting or referring to scientists, but none of the people in this particular book were selected because they weren't old white men, they were chosen because they had something relevant and interesting to say.

My correspondent noted that I had included a gay writer, a trans writer and African-American scientist - as it happens I have no idea about the sexuality of the people he mentions, but it surely is a big 'so what', especially as he had picked out just three from many individuals quoted.

I responded by pointing this out, and was sent back a wider range of individuals I'd quoted, one of whom seemed to have been singled out for being a muslim. I was a bit confused by some other examples, if the problem was 'unnecessary' diversity: he also appeared to criticise my choice of Lewis Carroll (for being the 'Jimmy Saville of the 19th century'), H. G. Wells for sleeping around and not liking Catholics, and Isaac Newton for being evil in his private life, conspiring to send Catholics to their deaths and stealing other people's ideas.

I don't think we should be selecting scientists or writers to quote (or avoiding them, for that matter) based on their private lives, my personal opinion of the character, their ethnicity or their sex - and I stand by everyone I quoted.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

July 21, 2023

New book - Biomimetics

My new book, Biomimetics, is now on sale. It looks at the ways in which technology and engineering have been inspired by nature - from the idea for Velcro that came from a burdock burr, to self-healing concrete. As I comment in the book:

My new book, Biomimetics, is now on sale. It looks at the ways in which technology and engineering have been inspired by nature - from the idea for Velcro that came from a burdock burr, to self-healing concrete. As I comment in the book:This book has turned out to be very different from the one I originally intended to write. The reality of what has happened in this field is at odds with the glossy marketing that refers to it (or, for that matter, practically every book that has been written about it). This lack of following expectation is not a bad thing. Talk to any scientist, and they will tell you that science gets interesting when the world does not behave the way we expect it to. Based on this metric, biomimetics and its implications for our understanding of the use of naturally inspired science and technology in new products and design is very interesting indeed.

Rather than tell you why I think it's wonderful (perhaps with a touch of bias), here's what Publishers Weekly had to say:

In this illuminating study, science writer Clegg investigates how scientists and engineers take inspiration from nature. Highlighting inventions modelled on natural structures and processes, he tells how Swiss engineer George de Mestral got the idea for Velcro from the burrs stuck to his dog’s fur; University of Akron graduate student Arnob Banik created tire treads modelled on the toe pads of tree frogs; and Dutch microbiologist Hendrik Jonkers developed a concrete mix featuring calcium carbonate–producing bacteria capable of filling cracks. Clegg also explores less successful attempts to harness the power of nature and details how Mercedes designed a bulky concept car resembling the build of a box fish, only to realise that “most of the fish’s excellent ability to change direction and dart around came not from its shape... but from the unusual operation of its fins.” Clegg is careful not to overhype biomimetic products (he expresses skepticism toward the claim of the Japanese company Teijin that its Morphotex fabric—which, like peacock tail feathers, gets its colour from how its texture refracts light, rather than from pigmentation—somehow reduces textile waste), but he remains optimistic that the future might hold self-healing iPhone screens and greener energy production. Jam-packed with fascinating ideas, this is a treat for pop science readers.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Biomimetics from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org - or find out more (or get a signed copy) at my website.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

July 17, 2023

You can't carbon offset with trees

Sigh. For reasons I don't entirely understand, I receive emails from Travel Neutral, a company that specialises, according to its website, in 'carbon offset and planet-aware holiday deals' like the one advertised in the image. To be honest, they aren't my kind of holiday firm, because I don't consider going on holiday a good enough reason to fly, but out of interest I followed a link to the company they use for offsetting.

Sigh. For reasons I don't entirely understand, I receive emails from Travel Neutral, a company that specialises, according to its website, in 'carbon offset and planet-aware holiday deals' like the one advertised in the image. To be honest, they aren't my kind of holiday firm, because I don't consider going on holiday a good enough reason to fly, but out of interest I followed a link to the company they use for offsetting. The good news is that they offer a good range of sensible green schemes from tree planting to renewable energy projects. The bad news is that using these for offsetting is mostly greenwash.

The idea of offsetting is that at the moment we all have to do things that generate greenhouse gasses. So you pay a little money to a scheme that will reduce greenhouse emissions, and this will balance out your contribution to climate change. But unless the amount of money you contribute will reduce carbon emissions (or equivalent) by at least the amount you generated before the next time you fly it's not really offsetting it. To take the example to the extreme, if your offsetting scheme only resulted in a reduction in 100 years time, then it would be totally pointless in terms of dealing with climate change.

While these schemes aren't quite so long term, the amount you pay will go nowhere near to producing an equivalent reduction in any even vaguely equivalent timescale to the flight. It would take a tree, for example, maybe 30 years to reduce carbon levels by the amount emitted for one passenger on a roundtrip long haul flight - in the region of 2 to 3 tonnes. (That's more than a typical UK car emits in a whole year, incidentally.) And most of the benefit would come after the first 10 to 15 years - because saplings don't take in a lot of CO2.

I need to reiterate that this does not mean that tree planting and renewable energy projects are bad things. Far from it. We need far more trees and far more green energy production. By all means support them. But it's magic thinking to believe that by putting a little money into these projects you can wipe the slate clean for your carbon-chugging flights. It won't.

This has been a Green Heretic production. See all my Green Heretic articles here.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

July 12, 2023

Alchemy (Crime/Historical Fiction) - S. J. Parris *****

Two writers shine when it comes to Tudorbethan murder mysteries: C. J. Sansom for his Shardlake books and S. J. Parris (Stephanie Merritt) for her novels with the unlikely figure of Giordano Bruno as detective. For popular science writers, the historical Bruno is a bit of a problem, as he is often portrayed as a martyr for science, but in reality was a mystic whose ideas were unoriginal and whose execution was for common-or-garden heresy, rather than being ahead of his time on cosmology. But as a detective he makes a great character in the loveable rogue with a conscience tradition. Think a sixteenth century version of Lovejoy (the books, not the TV series), but with less of tendency to kill people. Parris makes great use of this in her series of novels.

Two writers shine when it comes to Tudorbethan murder mysteries: C. J. Sansom for his Shardlake books and S. J. Parris (Stephanie Merritt) for her novels with the unlikely figure of Giordano Bruno as detective. For popular science writers, the historical Bruno is a bit of a problem, as he is often portrayed as a martyr for science, but in reality was a mystic whose ideas were unoriginal and whose execution was for common-or-garden heresy, rather than being ahead of his time on cosmology. But as a detective he makes a great character in the loveable rogue with a conscience tradition. Think a sixteenth century version of Lovejoy (the books, not the TV series), but with less of tendency to kill people. Parris makes great use of this in her series of novels.This latest, Alchemy, is set in Prague in 1588. The setting, with its contrasts of the Emperor's palace and the conditions of the poor is handled excellently. There's a particular opportunity here to explore some of the oddities of the period - and its biases - both in the bizarre work of the alchemists who feature in a big way, the power of the Catholic Church, and the treatment of the Jewish ghetto, which also play a major part.

As is often the case in Parris's books, Bruno is a reluctant detective, with a whole range of factions vying against him and providing potential suspects - including a form Catholic inquisitor and his Spanish thugs and the various hangers on hoping for the benefaction of the Holy Roman Emperor, who is generally a weak individual but is challenging the church.

What's great about both Parris and Sansom's books is that they give us all the enjoyment of the immersing in the period you get from a quality historical fiction novel, but at the same time provide us with some fun in trying to work out what's happening with the murder mystery - in this case one that is blamed by some on a golem, neatly tying in with the legend attached to the historical character Rabbi Loew. The one disadvantage Parris has in comparison with Sansom, whose detective is fictional, is that we do know Bruno's eventual fate (just as we did with Thomas Cromwell in Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall books), and there's always a slight frisson of 'will this be the last book?' I had to restrain myself from looking up when Bruno was executed (though Parris has confirmed he will have at least a couple more outings).

The only criticism I have is the book is perhaps a little over long - but I had a great time reading it. Parris gives us an engaging and complex mystery to unravel in a dramatically different world from modern Europe.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Alchemy from Amazon.co.uk and Bookshop.org. At the time of writing only the audiobook is on Amazon.com.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

July 10, 2023

The amazing appearing station - big data needs checking

One lesson anyone who has played with AI and big data should learn is that you can't trust it without having some checks in place. The technology can do the grunt work wonderfully - but then it needs verifying. This came to light when ChatGPT was caught making up references - but it can happen in a more subtle way too that is reminiscent to me of a flaw most of us never thought of when we saw Apple's 1987 Knowledge Navigator video.

One lesson anyone who has played with AI and big data should learn is that you can't trust it without having some checks in place. The technology can do the grunt work wonderfully - but then it needs verifying. This came to light when ChatGPT was caught making up references - but it can happen in a more subtle way too that is reminiscent to me of a flaw most of us never thought of when we saw Apple's 1987 Knowledge Navigator video.For those of us not ancient enough to remember it, Knowledge Navigator was a 'view of the future' video from Apple that predated iPads, folding screens and AI. In it, a distinctly smug academic uses a combination of AI, big data and a touch interface to link information about different events in the world to get the big picture. What said smug academic never does is actually check that what he is being shown is correct.

Of course Knowledge Navigator was fantasy - and for those of us who saw it when it came out, it was a genuinely wonderful peek into the future. (Bear in mind that Windows 3, the first really useable version of Windows didn't come out until 1990.) But these days it's easy to duplicate some of what it did using data tools such as 'Google My Maps' and a collection of locations to produce an impressive looking map. This is what was done using a list of UK stations published by the Daily Mirror, where ticket offices are scheduled to close.

When I came across the map online, I thought, out of interest, 'I wonder if my local station (Swindon) is losing its ticket office. I admit I never use the ticket office, but it's a big station and it seemed unfortunate if it were the case. Sure enough, as I zoomed in I saw an indicator by Swindon. But as I zoomed in further (see image at top), I noticed that it was actually to the east of Swindon. When I clicked on it, I was told that it was Wanborough station was closing.

As it happens, I used to live in the village of Wanborough. It has never had a station. The railway line doesn't go particularly near it. But, like many villages, its name is not unique. There is also a village called Wanborough in Surrey between Aldershot and Guildford - and that does have a station. Whoever combined the list of places with a map didn't bother to check for names that could be ambiguous.

I have no doubt that data tools and big data and AI will play bigger and bigger parts in our lives - but like ChatGPT's dodgy references, the mystery of the amazing appearing station underlines that it's likely there will always be a need for a degree of human checking to keep the algorithms and data tools on the right track.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here