Brian Clegg's Blog, page 22

April 9, 2023

In Conversation with Tim Marshall

Join bestselling author Tim Marshall, in conversation with Brian to celebrate the publication of Tim's new book The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change our World.

Join bestselling author Tim Marshall, in conversation with Brian to celebrate the publication of Tim's new book The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change our World.The ‘stream and book’ package includes a unique ticket for the stream, and a copy of The Future of Geography (RRP £20) deliverable to any UK or international address. This event is free to watch. Tickets are available here.

The event will initially be broadcast on Friday 12 May at 6.30pm UK time. It will be available to view up to two weeks after the event has ended and can be accessed Worldwide. If you live in a time zone that does not suit the initial broadcast time you can watch it at any point after the initial showing for two weeks.

Spy satellites orbiting the moon. Space metals worth billions. People on Mars within our lifetime. This isn’t science fiction. It’s astropolitics.

Space: the new frontier, a wild and lawless place. It is already central to communication, military strategy and international relations on Earth. Now, it is the latest arena for human exploration exploitation – and, possibly, conquest. China, the USA and Russia are leading the way. The next fifty years will change the face of global politics.

With all the insight and wit that have made Tim Marshall the UK’s most popular writer on geopolitics, this gripping book shows that politics and geography are as important in the skies as on the ground, covering great-power rivalry; technology; commerce; combat in space; and what it all means for us down on Earth. Tim and Brian will discuss the role astropolitics has to play in our society today and why power and politics in space will define the future of humanity.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

In Conversation with Tim Marshall - Friday 12 May, 6.30pm

Join bestselling author Tim Marshall, in conversation with Brian to celebrate the publication of Tim's new book The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change our World.

Join bestselling author Tim Marshall, in conversation with Brian to celebrate the publication of Tim's new book The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change our World.The ‘stream and book’ package includes a unique ticket for the stream, and a copy of The Future of Geography (RRP £20) deliverable to any UK or international address. This event is free to watch. Tickets are available here.

The event will initially be broadcast on 12 May at 6.30pm UK time. It will be available to view up to two weeks after the event has ended and can be accessed Worldwide. If you live in a time zone that does not suit the initial broadcast time you can watch it at any point after the initial showing for two weeks.

Spy satellites orbiting the moon. Space metals worth billions. People on Mars within our lifetime. This isn’t science fiction. It’s astropolitics.

Space: the new frontier, a wild and lawless place. It is already central to communication, military strategy and international relations on Earth. Now, it is the latest arena for human exploration exploitation – and, possibly, conquest. China, the USA and Russia are leading the way. The next fifty years will change the face of global politics.

With all the insight and wit that have made Tim Marshall the UK’s most popular writer on geopolitics, this gripping book shows that politics and geography are as important in the skies as on the ground, covering great-power rivalry; technology; commerce; combat in space; and what it all means for us down on Earth. Tim and Brian will discuss the role astropolitics has to play in our society today and why power and politics in space will define the future of humanity.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 8, 2023

When is a conspiracy theory not a conspiracy theory?

There seems to be increasing support for the idea that the SARS-Cov-2 virus (Covid for short) pandemic started as a result of a (probably accidental) leak from the Wuhan laboratory. While the authorities are expressing low confidence in whether or not it's true, there is an acceptance from the likes of the FBI that it is the most likely cause.

There seems to be increasing support for the idea that the SARS-Cov-2 virus (Covid for short) pandemic started as a result of a (probably accidental) leak from the Wuhan laboratory. While the authorities are expressing low confidence in whether or not it's true, there is an acceptance from the likes of the FBI that it is the most likely cause.What's worrying about this is not that the scientific viewpoint has changed. Changing your theories to reflect new data is a fundamental of science. In fact one of the two biggest problems science has in general with switching to a new theory is not that views alter, but rather that many scientists who build their careers on a particular theory are reluctant to change their minds, even when the evidence becomes strong that an alternative theory is now the best supported by the evidence. (The other problem is that those who don't understand science, particularly in the media, see a change of mind as weakness rather than the strength that it is.) No, what's worrying about the lab leak theory is the way that it has been treated by leading scientists.

It was fine to doubt the lab leak theory and point out what was wrong with it - but many high profile scientists labelled it a 'conspiracy theory'. And that was a serious error.

Calling something a conspiracy theory is a term of disapprobation, suggesting that those who hold it are at best misguided and at worst idiotic. Let's compare a few conspiracy theories with the lab leak hypothesis. Classic conspiracy theories include the flat Earth, the idea that the moon landings were faked and the suggestion that world leaders (and the British royal family) are intelligent lizards in human suits. What makes these conspiracy theories is that there is strong evidence that the theory is not true, but no good evidence that the theory could be true. In many cases, it's also the case that there is no particular benefit to be gained from all the effort that would be required to maintain the conspiracy. (Admittedly, the intelligent lizards would see a benefit in keeping their existence quiet.)

The lab leak theory was quite different. There was no strong evidence either way. There was some evidence for both the wet markets and a lab leak as the source of Covid, but nothing definitive. But it really shows a poor understanding of human nature to say, without good evidence, that a virus that originated in Wuhan, where there is a laboratory experimenting on that kind of virus, couldn't have come from the lab.

Rather than basing the action on any science, suppressing the lab leak theory was considered important for political reasons - in a sense, this action genuinely was a conspiracy by the authorities: the kind of suppression of information that can sometimes be necessary in times of national emergencies, as is arguably the case with wartime propaganda. Whether it really was necessary here is extremely doubtful - but the mistake was to label lab leak a conspiracy theory, rather than one with limited evidence to support it. 'We just don't know: we shouldn't speculate until we have better evidence' would have been a far better line than 'it came from wet markets and to suggest otherwise is a conspiracy theory.'

Interestingly, when I was thinking of examples of real conspiracy theories, one that doesn't fit the mould I mention above quite so well is the murder of JFK. Here again, the evidence of exactly what happened isn't intensely strong - so it is perhaps over-reacting to call alternative views of what happened conspiracy theories. We can say the Lee Harvey Oswald version has somewhat better evidence than alternative theories, but it's a topic that is never like to have good enough detailed data to have a definitively supported theory of what happened.

Now, unfortunately, those scientists who leapt to the conspiracy theory label are receiving a backlash - and it's science that suffers as a result, because those with an anti-science agenda can use this as a weapon against the scientific community. It's hard to say 'I don't know', especially if the media are calling you an expert. But, arguably, things would be better if more in the science community said it more often.

Image by Ben White from Unsplash.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 6, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 6 - the contract

This is surely one of the most exciting points of the writing journey. Your book proposal has been accepted by a publisher and they send you a contract. Woo-hoo!

This is surely one of the most exciting points of the writing journey. Your book proposal has been accepted by a publisher and they send you a contract. Woo-hoo!You might be tempted to immediately sign on the dotted line but you do need to check it out carefully. Publishers' contracts can be littered with 'interesting' clauses that you need to query - and just because they have made you an offer doesn't mean you have to go for it in its initial form.

A starting point is the kind of book deal they are offering. Broadly, they tend to be either flat fee or advance-and-royalty based. In the case of a flat fee, the publisher offers you a fixed amount, often divided into two parts (usually one on signing the contract, and on acceptance of the manuscript). The more traditional publishing approach is advance and royalty. Here you get offered a smaller amount up front - the advance. You will then get extra payments (the royalty), but only once your part of the earnings from the book exceeds the advance. Again, the advance will typically be split, most often three ways between date of signing, date of acceptance and date of publication.

There is one big advantage of advance and royalty - you may end up earning many times the initial advance (and you don't have to repay anything, even if the book never earns enough to produce any royalties). However, there are some plus points from the flat fee. As mentioned, it will usually be more than the equivalent advance, and if you don't like the whole business of publicity (more on that in the next post), there is far less obligation with a flat fee book, because (frankly) you don't really care how many copies are sold.

I've written quite a few flat fee books: what it comes down to, primarily, is how you feel about it as a journalism job. Work out realistically how long it will take you to write the book (including any edits). If the flat fee will pay you an acceptable wage for that period of time, it's acceptable. If not, don't go for it (unless this is spare time activity and it's more important to you to get published). Incidentally, you can always say it's not enough - many publishers (though not all) will move on their initial offer. This obviously applies to the size of the advance in advance and royalty too. The amount is always potentially negotiable.

However, though I've written flat fee books, I much prefer advance and royalty. Partly because I feel more invested in the final book, but mostly because there is more opportunity for income. (Yes, I love writing, but there's nothing wrong with wanting a good income: don't feel embarrassed by this.) One of the big potential opportunities is translations. With flat fee book, you don't get paid anything extra for translations unless you can negotiate that as a special case, which is rare. With an advance-and-royalty book, earnings from translations will be part of the contract. I've had books where a single translation deal has paid off the entire advance, meaning every single sale counts towards extra royalties.

I can't cover everything to check in a contract (and I'm not a lawyer). One really big piece of advice here is, if possible (and you are UK based) join the Society of Authors. It's relatively cheap, and they offer a free contract-checking service, pointing out dodgy aspects for you to get back to the publisher on. For full membership you need to have a book published, but there are various degrees of membership (e.g. you can get 'emerging author' status as soon as you have a contract or an agent's agreement).

Financially, with a flat fee contract, it's simply about the amount. Some publishers will offer a bonus, for example if you exceed a number of copies sold - it's always worth suggesting this. There are far more components to royalties. You will be offered a percentage of either the cover price or the price the book is sold at (the cover price is best, but this isn't often offered anymore). This will usually vary between hardback and paperback and whether the book was sold by the publisher with a high discount. Publishers will often accept the idea of an escalator. This says with sales over a certain level you will get a higher percentage. Then there all the other potential sources of income.

Say you are offered 7.5% for paperback and 10% for hardback (yes, the percentages are often this low). You can expect a much higher percentage - say 25% - on ebooks and audio books, as the costs to the publisher are far less. You will then be offered a whole list of subsidiary rights. These are sources such as translations, serial rights (publication of an extract in a newspaper, say), film and broadcast rights. It's very rare these should be less than 50%. For translation rights, publishers may give you, say, 60-70% and serial rights could be as high as 90%. What you can get here is always subject to negotiation - a publisher will often be prepared to up the percentage a bit on subsidiary rights as it's effectively money for nothing as far as they (and you) are concerned.

There are a number of things to look out for in the contract, of which I'll just highlight a few. If it's to be illustrated, who pays for illustrations? What liabilities do you have? Does the publisher have any claim on your next title? And is there a competition clause?

Illustrations cost a publisher money, both in producing the book and, if necessary, obtaining copyright or having a designer put together a diagram. Some contracts will load these costs onto the author: if illustrations are important to your book, unless you are able to use public domain images (for example NASA's space photos), you may end up paying more than your advance just on the illustrations. If you are landed with the cost, ask the publisher to take it on (perhaps discussing a limit), or be prepared to cut illustrations to a minimum.

Then there's liabilities. Many contracts have scary clauses about liabilities and indemnifying the publisher against damages resulting in breaches of your warranties. Some of this you are just going to have to live with. You will be expected to say that your writing is original - if you plagiarise someone else, then the publisher quite rightly can't be expected to suffer any damages. It becomes more of a grey area when you get onto, for example, the potential for libel. If you are writing a biography of a controversial figure, for instance, then it would be reasonable for the publisher to accept responsibility for any legal defence.

A relatively common clause is one where you have to offer your next book or next couple of books to that publisher first. Generally speaking this isn't too much of a problem. It's a courtesy: it's very rare a publisher will insist on taking a book they aren't the right publisher for, just to activate this clause. I've never had an example where a book I intend to write for another publisher (because it doesn't suit the existing publisher) has been blocked.

Something that is harder is a competition clause. This is where you say that you won't write a book for another publisher that competes with this book. This is a very vague concept. Where it's put in the draft contract, I have always tried to get it struck out, and often succeeded. If the publisher insists on it, I have always got from them in writing a clear definition of what would count as competition. So, for instance, if I wrote an illustrated overview of quantum physics, I would establish that only another illustrated overview would be in competition not, for example, a book about a specific quantum physics topic, such as entanglement or quantum computing.

All this might sound a bit depressing - but remember a contract is good news. They want your book! The main thing is to discipline yourself and read it carefully, even if it runs to many pages. (Take it a bit at a time if necessary.) Make sure they aren't ripping you off. Use a checking service, such as the Society of Authors' service, if you can. Sign up with confidence, or not at all.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposal The pitch letter Finding a publisher (or agent) The contractPublicity (and extra earnings)Self-publishingImage by Romain Dancre from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

April 3, 2023

Review: A Fatal Crossing - Tom Hindle ***

A straightforward and workmanlike murder mystery, set on a 1920s transatlantic liner. After a passenger dies in suspicious circumstances, an uncomfortable combination of a mentally tortured ship's officer and a semi-disgraced Scotland Yard detective set out to uncover a rapidly evolving situation with missing paintings and more deaths.

A straightforward and workmanlike murder mystery, set on a 1920s transatlantic liner. After a passenger dies in suspicious circumstances, an uncomfortable combination of a mentally tortured ship's officer and a semi-disgraced Scotland Yard detective set out to uncover a rapidly evolving situation with missing paintings and more deaths.The setting makes for a classic situation of being isolated - so the culprit(s) have to still be there - and claustrophobic, despite the size of the luxury liner. Tom Hindle does a solid job of bringing in the various characters, and the culprit is not obvious until close to the end, involving some clever misdirection.

I was slightly surprised by the cover claim that 'the action unfolds at a rip-roaring pace', as I found the pacing distinctly glacial, held up in part by the way the two detectives kept irritating each other, and by the ship's officer Birch's personal problems.

There is a dramatic twist at the end, though it was reasonably obvious what it was going to be before it happened. I felt that, compared with the slow pace of the rest, this was a little hurried, in that the implications of it weren't really carried through in the ending.

All in all, a good murder mystery that made for an entertaining enough read, but comparisons with Agatha Christie over-inflated both the cleverness of the plot and the detective story mechanics.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy A Fatal Crossing from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

March 30, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 5 - finding a publisher (or agent)

The quick version of this part of the non-fiction book journey is 'do your research'. I have a friend who runs a small publishing house that specialises in certain kinds of memoir and self-help. Every week, she receives novels, and non-fiction proposals that are way outside her scope. This does not make her happy.

The quick version of this part of the non-fiction book journey is 'do your research'. I have a friend who runs a small publishing house that specialises in certain kinds of memoir and self-help. Every week, she receives novels, and non-fiction proposals that are way outside her scope. This does not make her happy.Traditionally I would have said the best thing to do would be to buy a copy of one of the publishing guides, but now it's easy enough to go through a good number of books aimed at a similar readership as is your own in an online bookshop, noting down their publishers. Build a list of, say, ten likely publishers then visit their websites and explore them in detail. Look at how they describe themselves and what ranges of books they publish. Take a look at any guidance they have for authors. As mentioned in the previous part, try to find an appropriate contact (a commissioning editor, usually) to send a proposal to for each publisher. (Linked-In can sometimes help with this.) Only then send off your proposal.

Some worry about sending out a proposal to more than publisher. There's no need to be concerned. In the olden days, some publishers might have regarded this as 'bad form' - but they are more commercial organisations now and recognise that this is going to happen.

A number of publishers don't take direct submissions from authors, requiring you to have an agent. This is typically the really big publishers, such as Penguin Random House. We'll come onto agents in a moment. But most of the smaller publishers do take direct approaches - and they may well be better to start with than a big firm. With the big companies you are a tiny fish in a huge sea and may well get very little support even if your book is commissioned. I've almost always get more post-publication marketing from small to medium sized publishers than the big names.

An agent, of course, takes some of the pain of hunting for a publisher away, in exchange for typically between 10 and 20 per cent of your earnings. They can seem appealing - I've worked both with and without an agent. The biggest plus from having an agent was being made more visible to the publishing business at large. He also got me the biggest advances I've ever had (interestingly, for book that would not be my bestselling ones, in part because of that lack of marketing). But the downside of having an agent, apart from giving up that percentage of my earnings, was that I had to fit my publishing timetable to him, often leaving me with weeks or months without anything happening. It can also be harder to get an agent than to get a publisher direct. In the end I preferred the hands-on control of not having an agent and we were mutually happy with the parting.

If you want to find an agent, again research them well. Some specialise in different types of books, or different markets. Because agents are less visible to the public than publishers, you will get more benefit here from getting a copy of something like the Writers' and Artists' Yearbook to help develop a contact list.

So, you make contact, a publisher likes your proposal and makes you an offer. Brilliant. But they will also send you a contract - and that can have plenty of pitfalls, so that will be our next consideration.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposal The pitch letter Finding a publisher (or agent)The contractSelf-publishingImage by Jaredd Craig from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

March 27, 2023

Review: Terry Pratchett - A Life with footnotes - Rob Wilkins ****

When someone gave me a copy of this book I was rather doubtful. Not because the chances are it's only going to be of interest to Pratchett fans, because that why I was given it in the first place. I have more Pratchett novels on my bookshelves than those by any other author - and most of them are hardbacks, suggesting I couldn't wait for the paperback, a sure sign of fandom. However, I find it easy to separate the creator and their creation. Just because I enjoy a particular book, or piece of music, or artwork - or even foodstuff - doesn't mean I have any real interest in the person who created it. They are quite distinct entities.

When someone gave me a copy of this book I was rather doubtful. Not because the chances are it's only going to be of interest to Pratchett fans, because that why I was given it in the first place. I have more Pratchett novels on my bookshelves than those by any other author - and most of them are hardbacks, suggesting I couldn't wait for the paperback, a sure sign of fandom. However, I find it easy to separate the creator and their creation. Just because I enjoy a particular book, or piece of music, or artwork - or even foodstuff - doesn't mean I have any real interest in the person who created it. They are quite distinct entities.The starting point, then, has to be whether the subject's life story is interesting as a standalone thing. And I think it's fair to say that in Terry Pratchett's case, that it was quite interesting. Not in any outstanding way - his wasn't an extraordinary life by any means - but there is no doubt that some of the aspects of his personality that come through in his writing also came through in the quirks of the way he went about life in general, especially in his social life and jobs before he became a full-time writer.

As a piece of writing, the biography does have some flaws. It's far too long. I got about half way through the more than 400 pages and started flagging, finishing it off much more slowly than the first half, because I had to force myself to go back for more, rather than returning to it eagerly. Rob Wilkins, who was Pratchett's assistant for a good number of years knew him well, had access to Pratchett's fragmentary autobiography and was probably uniquely well placed to put together this book. He writes well, though when he attempts humour it feels like he is trying too hard and can be a little wince-making. But the positives weren't enough to make the length enjoyable.

The other issue with the second half, other than it took me so long to get there, was that with success, inevitably, Pratchett's life becomes more detached from everyday experience than in his struggling years, and as such was harder to relate to.

I'm giving the book four stars because I think Wilkins does a good job, and in parts it is genuinely interesting - but it hasn't persuaded me of the benefit to a fan like me of reading a biography of the author. What I'll always treasure is Pratchett's novels. I'm quite happy to leave an author's life to the individual and their family.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy Terry Pratchett from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

March 18, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 4 - the pitch letter

To date in this series, we've got a book proposal together. There's one last component that can seem relatively trivial - but in reality requires as much effort as you can put into it - the pitch letter. This is the cover letter for your proposal.

To date in this series, we've got a book proposal together. There's one last component that can seem relatively trivial - but in reality requires as much effort as you can put into it - the pitch letter. This is the cover letter for your proposal.In reality, these days, the 'letter' is likely to be an email, and that makes it particularly dangerous as we're used to writing emails quickly with limited editing. I highly recommend you craft your basic cover email in a separate editor, such as Word and only paste it in as an email once you are happy with the contents. This should help give it the attention it deserves.

Put yourself in the head of the person who receives this email. They will receive many such emails. Although I'm not an editor, I review a lot of books and I get sent plenty of book press releases from publishers, which are a form of pitch email. They go through a two stage filter. Quite a few will get deleted after a few seconds, because I can already tell they won't be interesting to me. I'm likely to have read the subject of the email, the title of the book and the first couple of lines in the press release. If they pass that filter I'll read on - but even then, they only get a minute or so before deciding whether to bin or to ask for a review copy, the equivalent of reading your proposal.

Note, by the way, I'm looking at this assuming you will be pitching direct to a publisher. This is likely to be fine with smaller publishers, but some of the big names use agents as gatekeepers - if that's the route you decide to go (I'll explore whether or not you should have an agent in the next item in the series), all that I'm saying about appealing to a publisher will also apply to catching the eye of an agent.

So, a starting point has to be the subject line of the email, a title line for your book and those first couple of sentences. By that point you need to have hooked the reader sufficiently to get past their first filter. Make the email subject simple and to the point - don't try to sell in it. I've already covered the book title in the previous part of the series. Next, I'd suggest putting in a single sentence summary - if you like, an elevator pitch. This is really hard to do, but essential to get right. I'd suggest getting quite a few possible versions in place before going for one and refining it.

Broadly there are two relatively obvious ways to do this. One is to compare it to books that have already done well, often in an X meets Y format. For example, if I was writing a book on relativity that made use of a collection of emails and other bits and pieces of communication, I might say 'A Brief History of Time meets The Appeal.' While I personally find this approach rather cheesy, I do know that some people have used it successfully. (X or Y could also be an author, e.g. 'Terry Pratchett meets Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire' is one that would make me read on.)

A good alternative is to pick out the USP (unique selling point) of your book - what makes it different, interesting and sellable? List some key words that describe what is distinctive about your book and see how you can bring them together into a pithy, attractive sentence.

Apart from that I'd probably only include three more paragraphs. Use a couple to expand on the book a little more - why it's important and (ideally) timely. And finally say a little about why you are the ideal person to write this book. We don't want your life history or greatest achievement (unless is directly relevant) - be aware of answering 'Why am I the right person, right now, to do this?'

One final consideration on content is whether to send out the pitch email with the proposal attached, or whether to send it out asking if they'd like to see the full proposal. (Either way, you should have the full proposal ready before sending out your emails.) The simple answer is I'm still not sure which works better. I tend to use a pitch email without a proposal, but have the advantage of being reasonably well-known in my field. The advantage of attaching the proposal is that if they like your idea, they can get straight into it; the disadvantage is it feels a bit pushy. If you aren't sure, I probably would attach the proposal.

Are we ready to send the email? Not quite. Who are you going to send it to within a publishing company? If at all possible, send it to an individual rather than a generic email address. Spend a few minutes researching the publisher online. The worst address to send it to is a generic information email for the publisher as a whole. Better if there is an address specifically for proposals and even better still if you can get the address of an appropriate commissioning editor. This may be possible from online searches, the Bookseller magazine (or similar), or contacts you might have in the publishing world.

At this point you are pretty much ready to go - but I've jumped the gun here, because in coming up with the right email addresses you need to know which publishers to send your proposal to. It's essential you do some research first - and that's the topic of the next post.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposal The pitch letterFinding a publisher (or agent)The contractSelf-publishingImage by Markus Winkler from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here

March 15, 2023

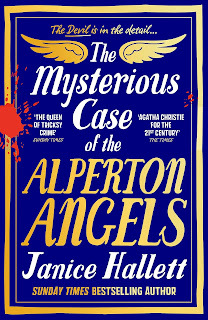

The Mysterious Case of the Alperton Angels - Janice Hallett *****

It seemed almost impossible after Janice Hallett's first two novels,

The Appeal

and

The Twyford Code

that things could only go down hill - yet, somehow, she's managed to better them both with her latest. While continuing in the same style of collected communications, the Alperton Angels is more gripping (and even more clever). And once more, the setting is sufficiently different to impress.

It seemed almost impossible after Janice Hallett's first two novels,

The Appeal

and

The Twyford Code

that things could only go down hill - yet, somehow, she's managed to better them both with her latest. While continuing in the same style of collected communications, the Alperton Angels is more gripping (and even more clever). And once more, the setting is sufficiently different to impress.Here we have the collection of notes, messages, emails and more put together by a non-fiction author, commissioned to write a true crime book on a terrible event from eighteen years earlier. A cult had persuaded a 17-year-old that her baby was evil. On the night of the great conjunction of the planets, it was to be sacrificed to save the world by deluded individuals who believe themselves to be angels in human form. Yet all but one of these 'archangels' appear to have killed themselves, while the last of them, Gabriel, is jailed for life for his part in their deaths, and the murder of an apparently unconnected man.

As was the case with the earlier books, the collection of documents and messages allows us to gain an idea of the character of the author, Amanda Bailey, and also brings in other authors working on the same series, a rival of Bailey's also writing about the Alperton Angels (because the unidentified baby should now be 18) and a motley collection of aging police officers, would-be amateur sleuths and more.

Things are inevitably all not what they seem - and with her usual skill, Hallett prevents the reader from spotting this until all is revealed. It is absolutely brilliant. Packed with twists, but also fascinating details. At first it seems as if it's going to be far too complicated to get your head around, especially as there are conflicting stories about what really happened, yet such is Hallett's skill as a writer than you never lose the thread and everything eventually opens up to reveal the complex workings within.

Less far fetched in plot than The Twyford Code, this is as near perfection as you get. I see Hallett has another title due out in 2024 (and yes, I've already pre-ordered it). Can she keep this up? I really hope so.

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here You can buy The Mysterious Case of the Alperton Angels from Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.com and Bookshop.org.

Using these links earns us commission at no cost to you

March 10, 2023

I want to write a non-fiction book - part 3 - finishing your proposal

The previous part of this series looked at putting together an outline, which both helps the writer get ideas together and is an essential part of a book proposal. Here we'll look at what else a good book proposal contains. Always remember that in the end this is a sales document - you are selling your book idea to a publisher. Make it engaging, not dull.

Start off with a title and subtitle. These may we be changed in discussion with a publisher, but it's a starting point and is necessary. The title is your first opportunity to grab the attention of a would-be reader. Don't waste it. It can either make clear what the book is about, or be a clever title that intrigues, which is then explained in the subtitle. Either way, the subtitle is also a good opportunity to get in some keywords that might be useful when someone searches in an online store.

I recently read Ananyo Bhattacharya's book The Man from the Future. This title could have applied to anyone male, but grabs the attention. The subtitle then fills in the essentials: The Visionary Life of John von Neumann. Or take James Gleick's book Genius. A one word title can be strong - but it certainly wouldn't work without the subtitle The Life and Science of Richard Feynman. This kind of approach works well with something like a biography. Sometimes, though, just coming out with the topic up front can be effective. One of my best-selling books is Inflight Science. We immediately get a picture of the topic area. But even here, the subtitle makes it clearer what it's about - A guide to the world from your airplane window. Without this, you might think the book was just for plane enthusiasts.

Next in the proposal we need a summary of what the book is about - no more than a page, and ideally somewhat less. (Historically, sticking to one page had a specific reason as publishers used to circulate a single page of paper internally - but keeping it compact is still essential.) The summary should encapsulate exactly what the book will do as a product. It's a common mistake to write this like the blurb on the back of a book. But that's aimed at the public and will often both use superlatives and leave questions unanswered to avoid spoilers. A commissioning editor is not interested in you saying this is the best book on [whatever your book is about] ever published. They want to read about what the book will deliver, not see self-praise. Make sure you give answers to the key points covered. If, for example, it is a book about an unsolved crime, you need to put your solution in here.

Write your summary like a good newspaper article. You want to grab your reader's attention and hold them. Craft the opening sentences so the editor wants to read on. The first paragraph should get us deeply engaged in the core of your subject, not meander around background matters. And make sure you end by pulling the whole thing together. Highlight what's special about your book. If you have personal experience that's relevant, mention it in passing, but unless it's a memoir/autobiography the essential is the book's topic, not you. You can reserve most of that for a short (no more than half a page) 'about the author' section, which should come next. Don't tell them about your school exam results - make sure it's about your experience that makes you the ideal person to write this book.

Next, the editor will want to see some context. Tell them what is already published in this area and why your book is different and better that the competition. Try to do this honestly - pick out four or five books that are as close as possible to yours. Reasons yours might be better include the other books being out of date, lacking detail, taking a totally different line and so on.

A final precursor to your outline is a short section on audience and delivery. Who will want to read your book? Resist the temptation to say everyone - it's just not true. But with many non-fiction books there are specific subgroups of the population who might particularly enjoy reading it. Make it clear who they are (and specify why). As far as delivery goes, when could you reasonably deliver the manuscript by? Again, be honest. Don't tell them what you think they want to hear, but what is realistic for you.

You also need to give a length in words and details of scale of illustration. Broadly, slim non-fiction titles start around 60,000 words, midsized around 80,000 and chunky ones 100,000 or more. As far as those illustrations go, how many do you envisage? Break it down, if relevant, to diagrams and photographs. Usually photographs will be black and white, in line with the text. (This means they need to be high contrast. Photos, say, of space scenes simply don't work this way.) If you need colour, say so - but be aware it pushes up cost and may make your book less likely to be published, unless it is a book that's driven by its illustrations. We'll come back to different kinds of book when we look at finding a publisher, as not all produce heavily illustrated books. Of course you won't actually know numbers of images or diagrams you need, but you can give a good guess.

Next comes the outline (see previous topic), and finally a sample of the book itself - usually a chapter or 10 to 20 pages. There's a temptation to make this your 'best' bit, but bear in mind the editor has to read it in isolation, so it can often be best to make it the first chapter (though ideally not an introduction, as these are often dull). This is your chance to show what your writing style is like. Don't try to fake it and be more literary than you usually would be - just make it count as an excellent piece of writing.

To finish, here's an outline of the topics this series of posts will cover.

Is my idea a book? Outlining Other parts of a proposalThe pitch letterFinding a publisherThe contractSelf-publishingImage by Scott Graham from Unsplash

See all of Brian's online articles or subscribe to a weekly digest for free here